Engineering Porous Biochar for Electrochemical Energy Storage

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental

2.1. Reagents and Instrumentation

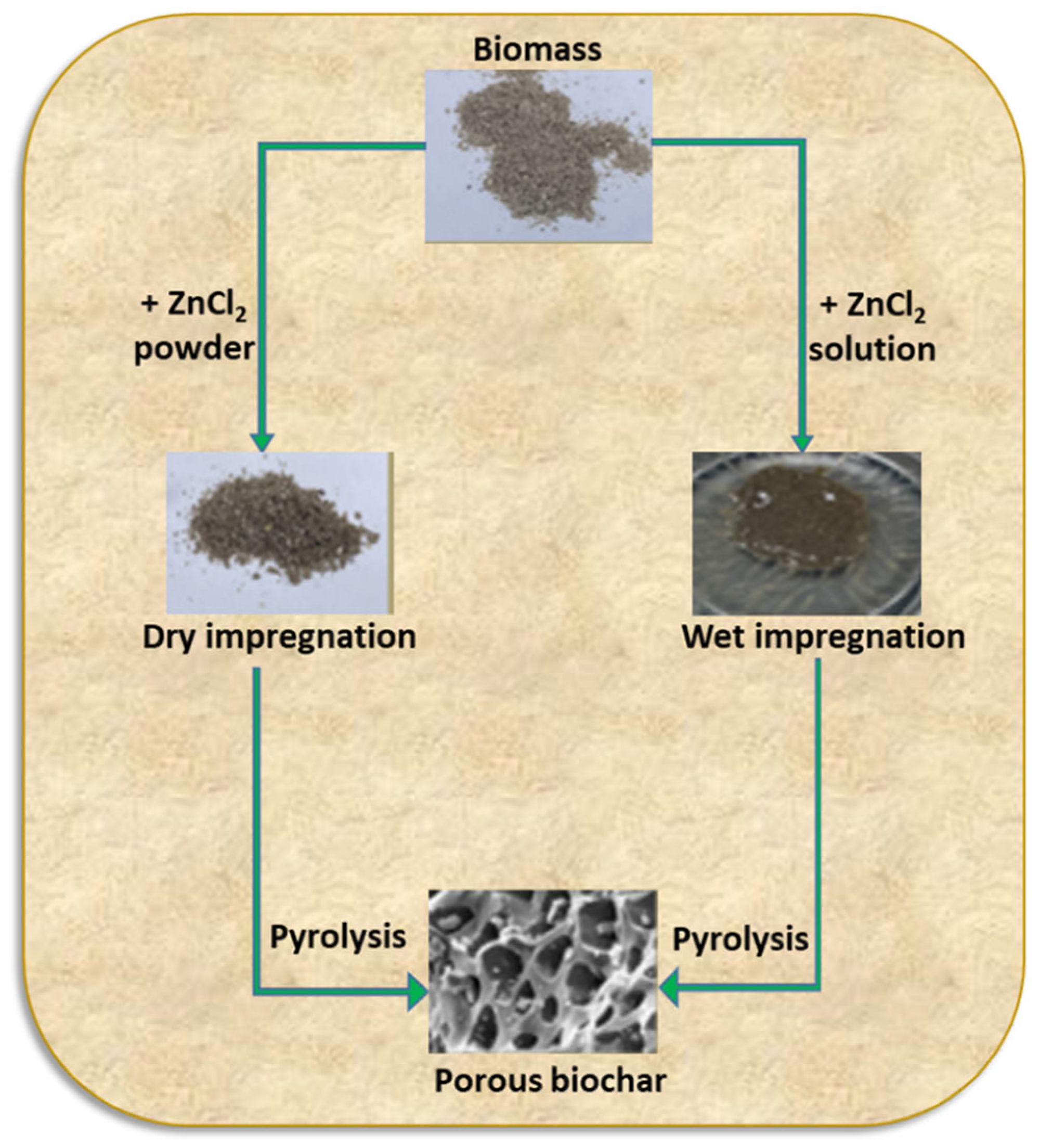

2.2. Synthesis of Activated Biochar

2.3. Determination of Iodine and Methylene Blue Numbers

2.4. Electrochemical Properties of Biochar

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Morphology of the Biochar Powder Particles

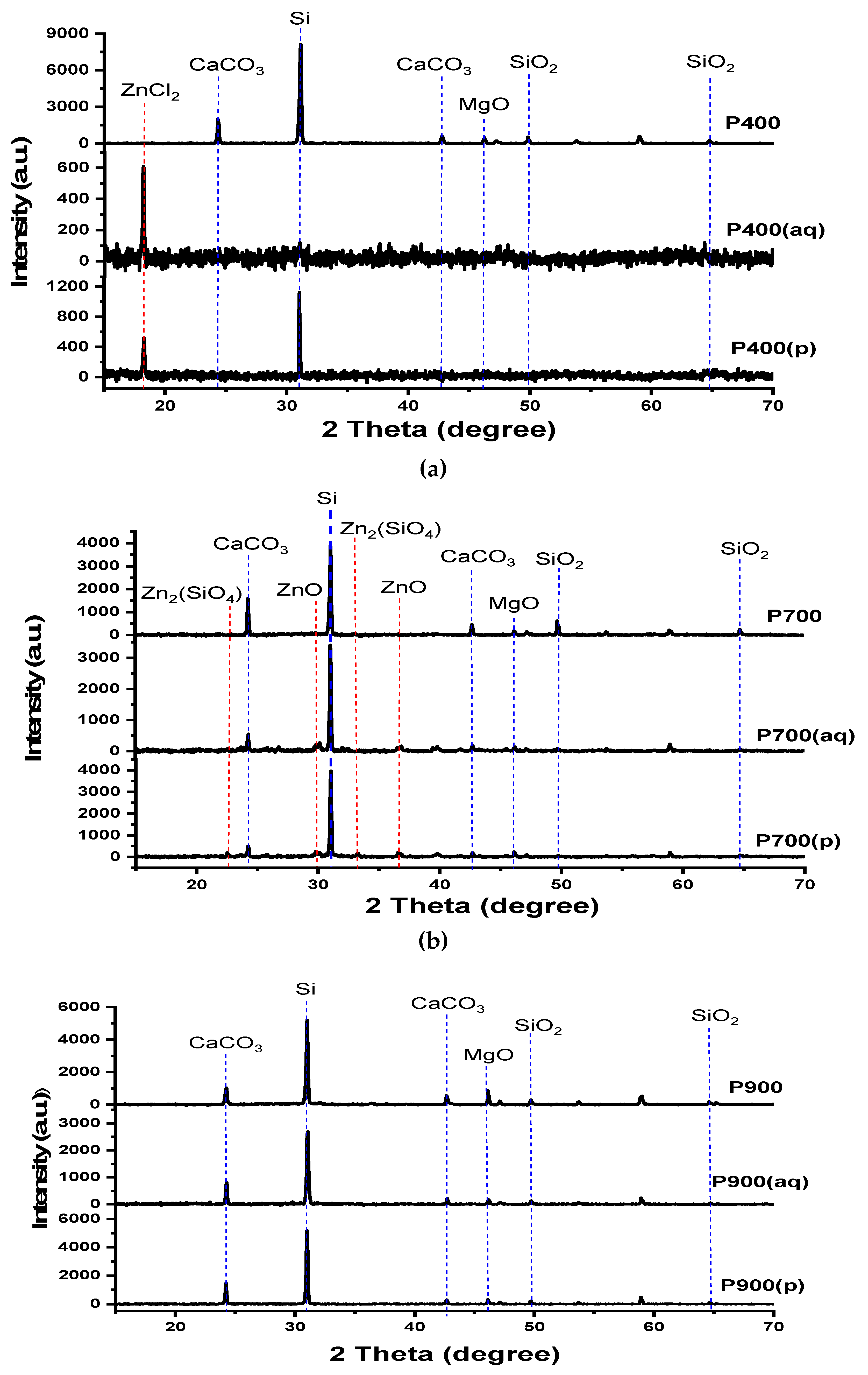

3.2. X-Ray Diffraction Characterization

3.3. Raman Spectroscopy

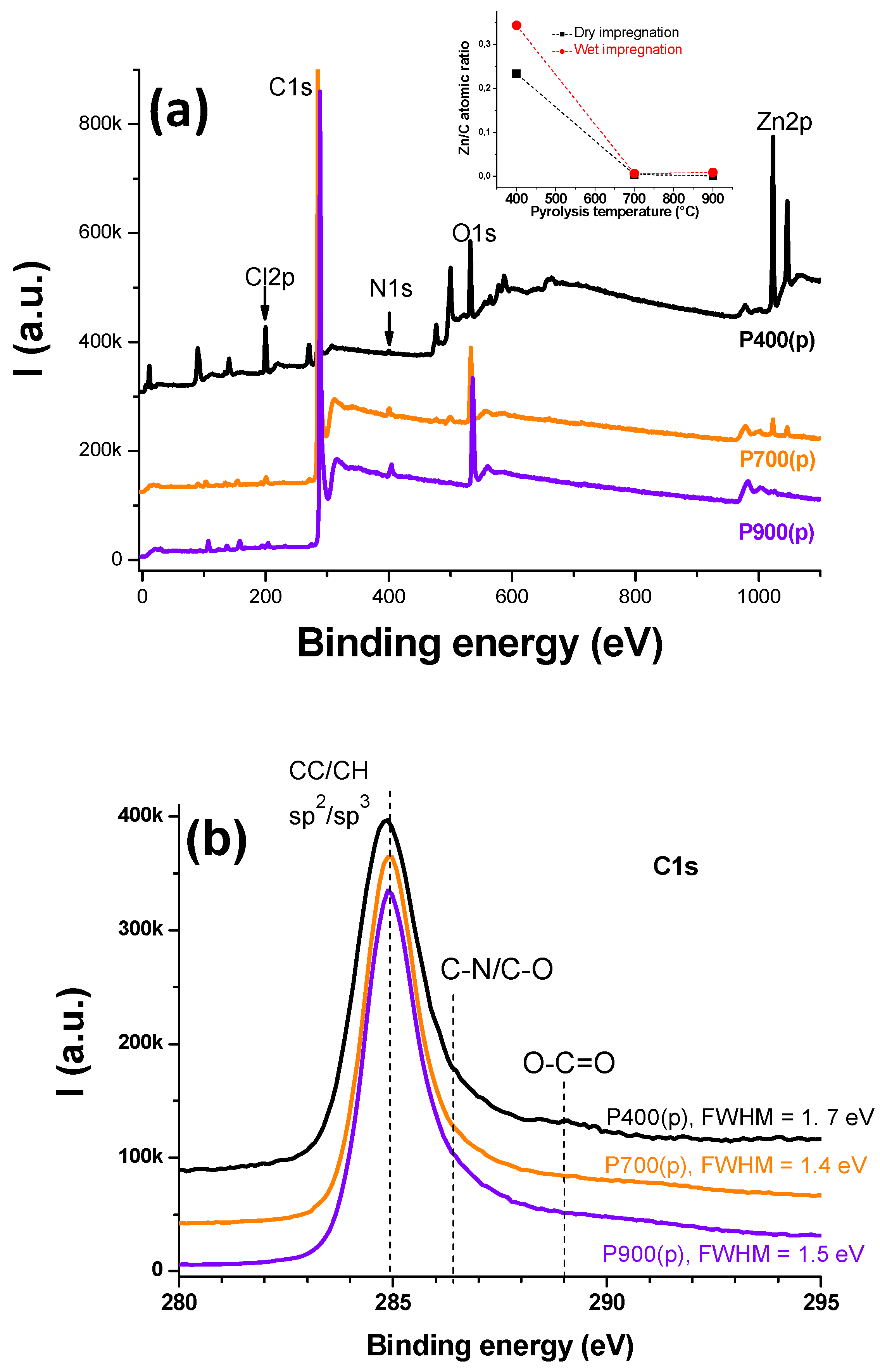

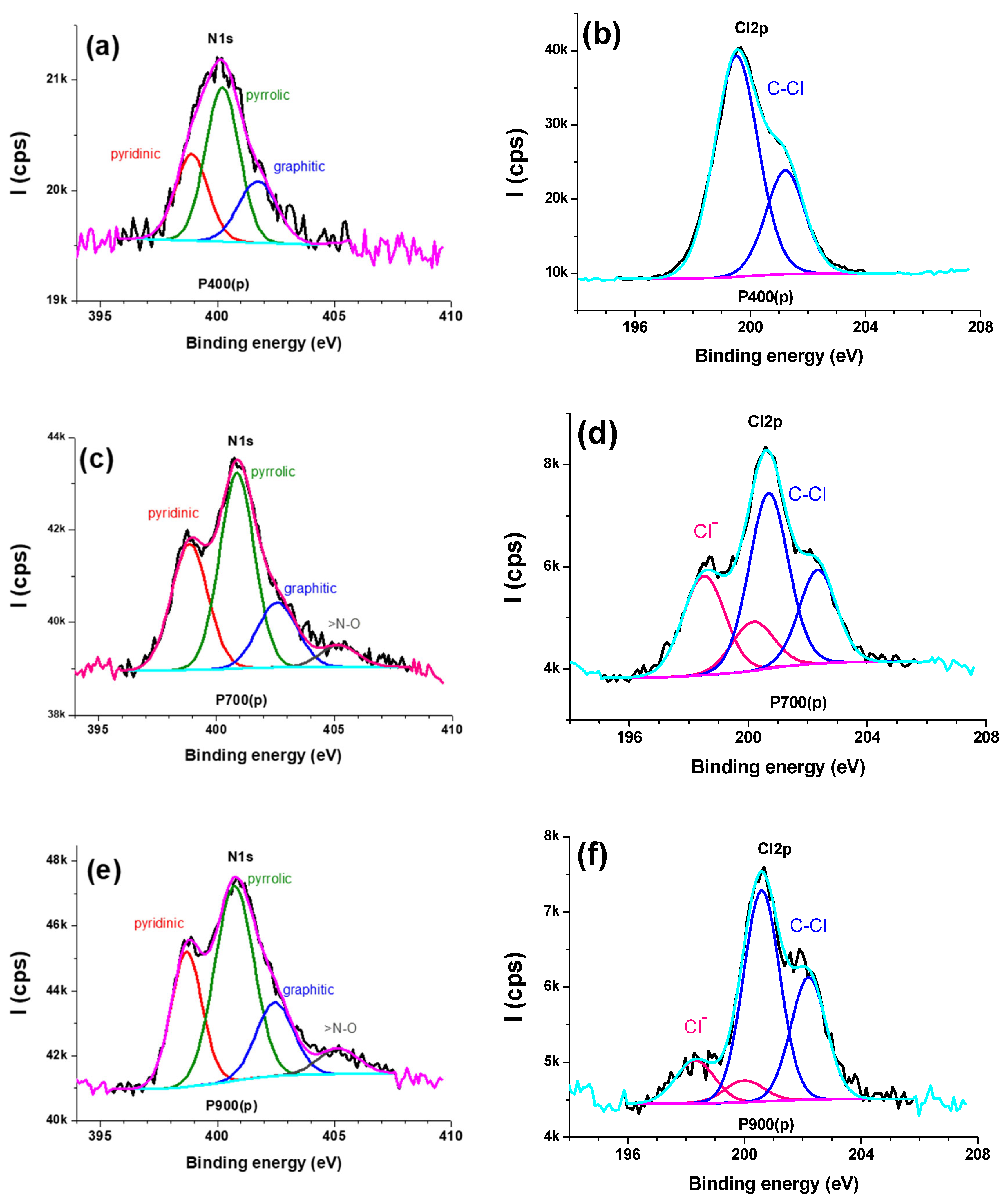

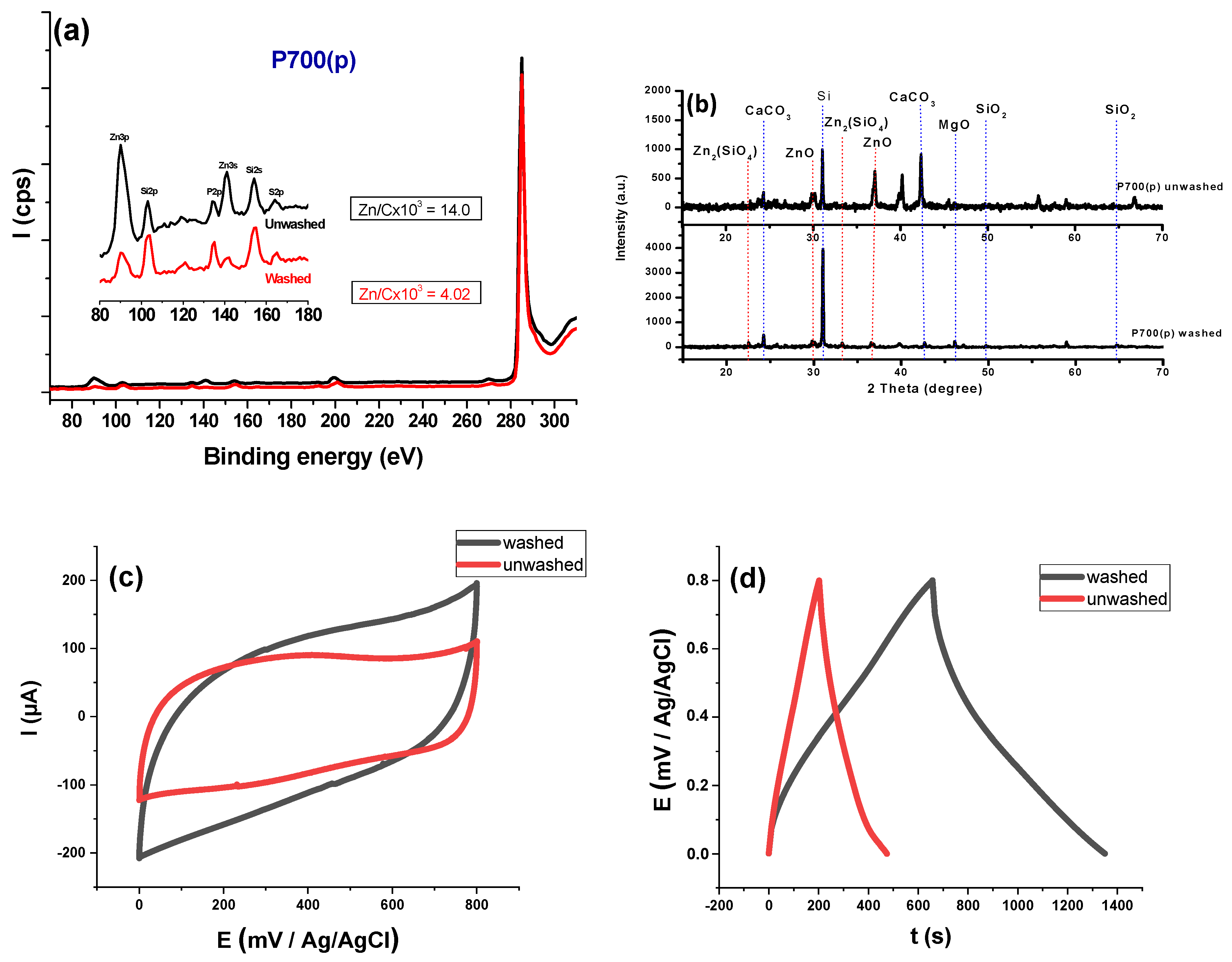

3.4. XPS

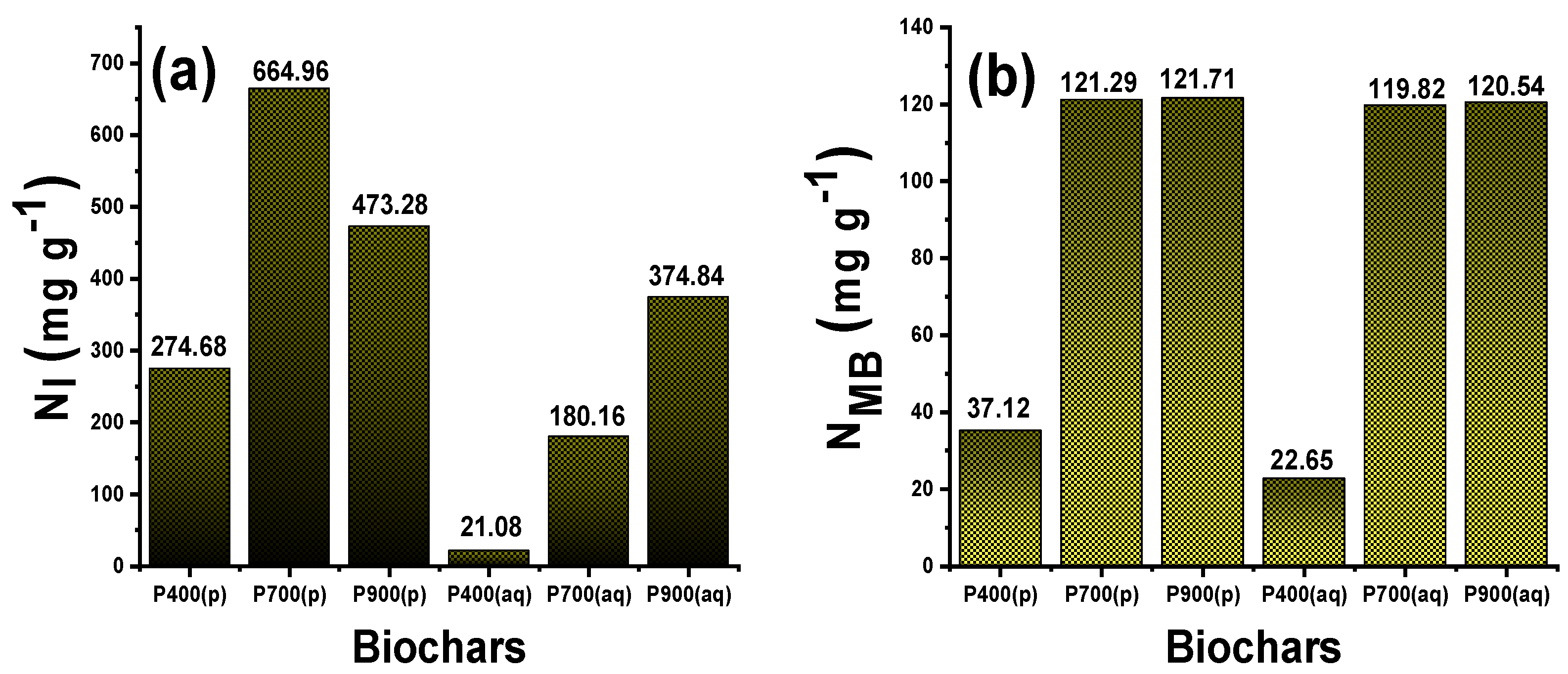

3.5. Determination of MB and Iodine Indices

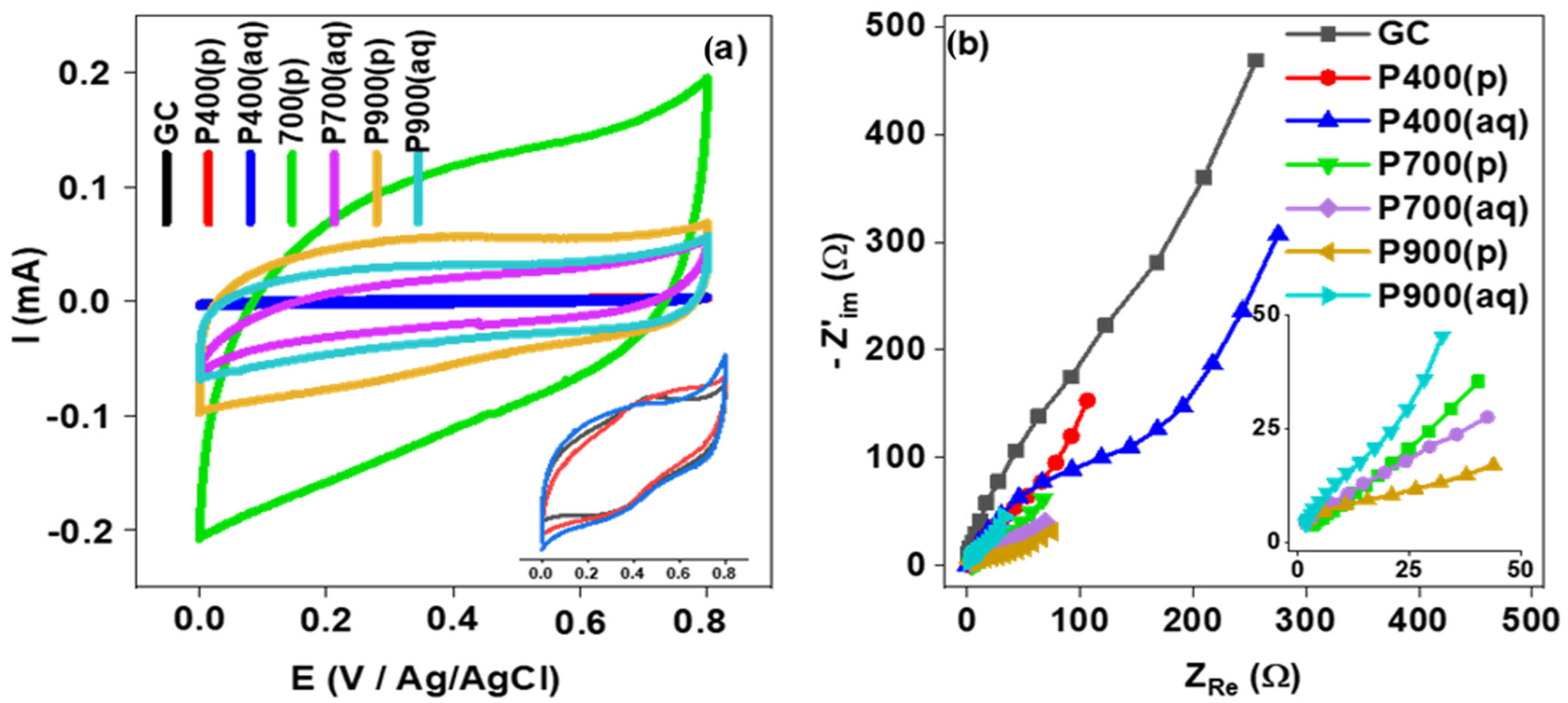

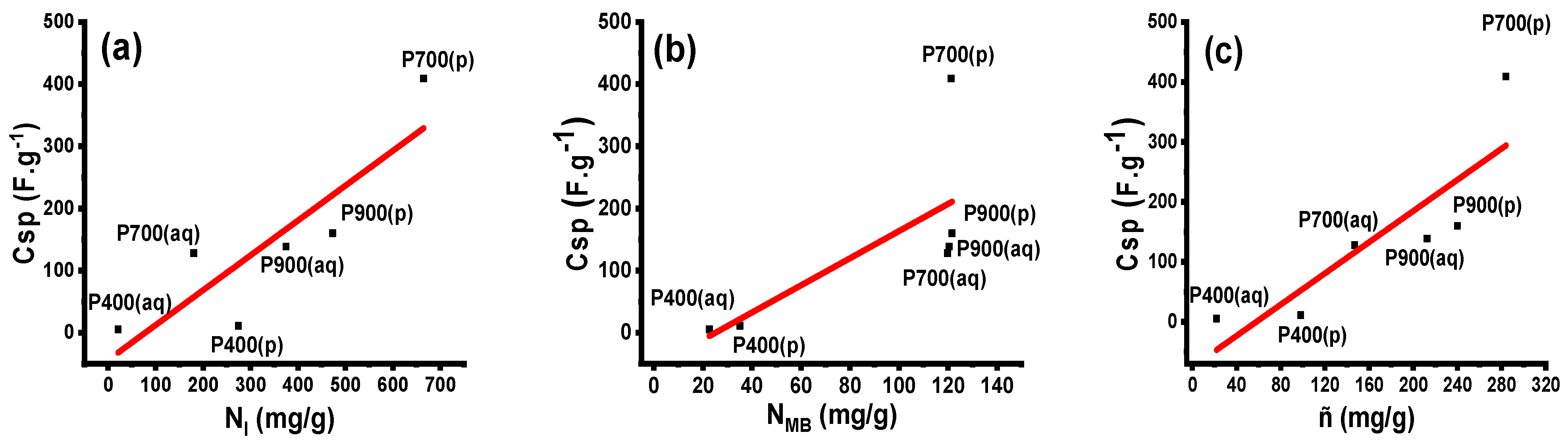

3.6. Electrochemical Characterization

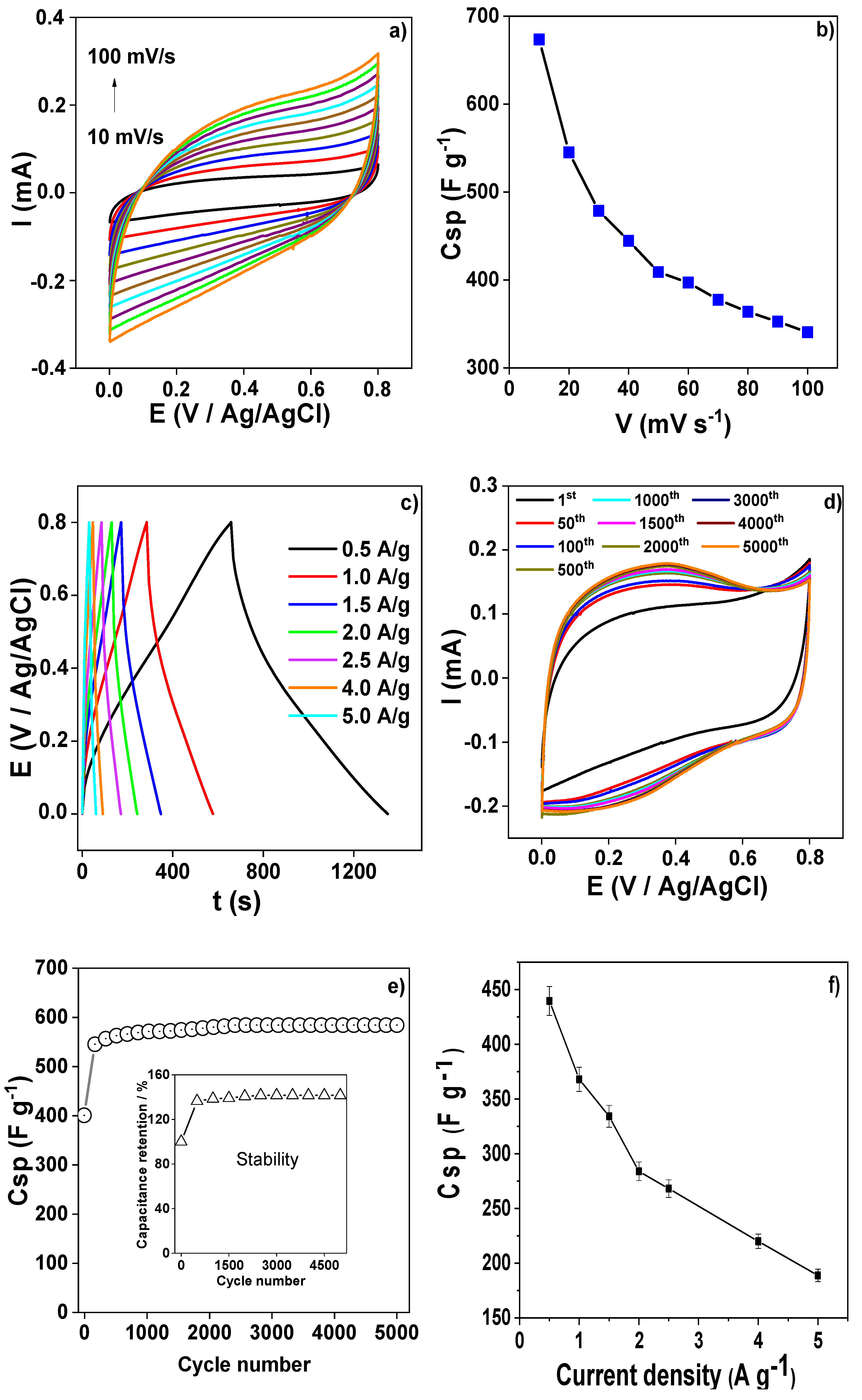

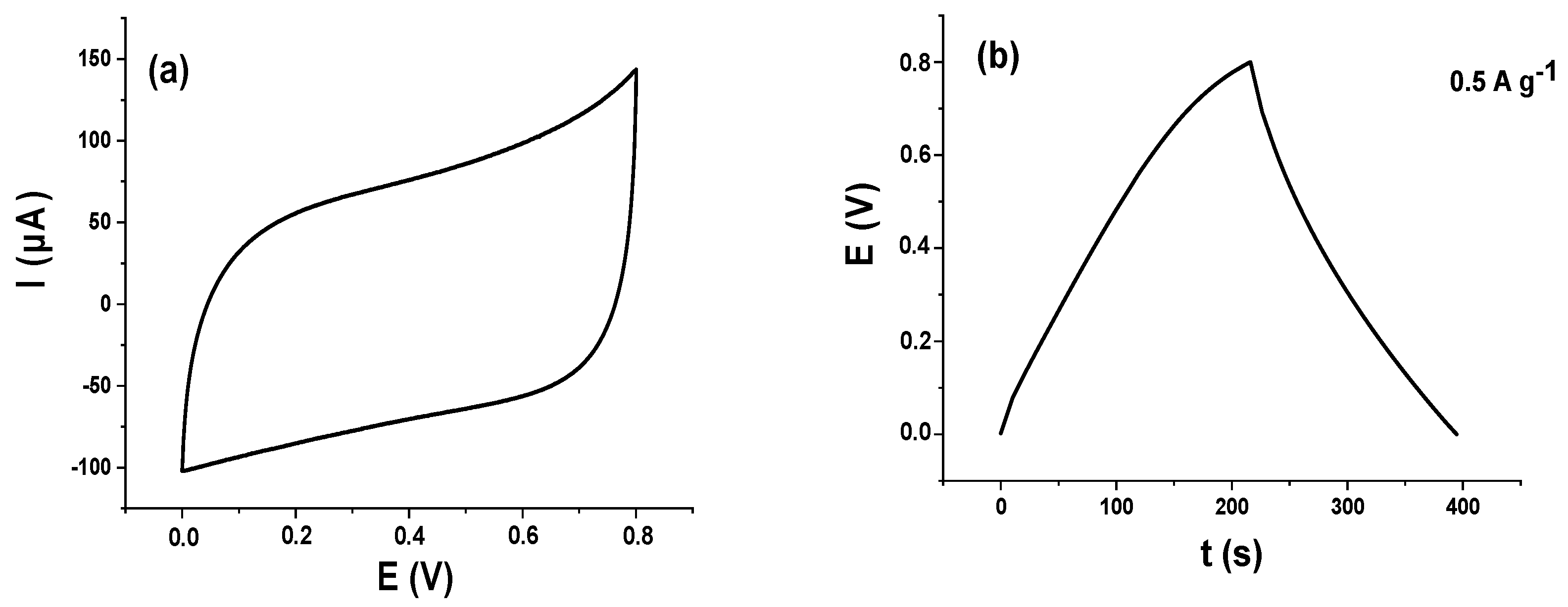

3.7. Supercapacitor Studies

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jellali, S.; Dutournié, P.; Jeguirim, M. Materials and clean processes for sustainable energy and environmental applications: Foreword. Comptes Rendus Chim. 2023, 26, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kebede, A.A.; Kalogiannis, T.; Van Mierlo, J.; Berecibar, M. A comprehensive review of stationary energy storage devices for large scale renewable energy sources grid integration. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 159, 112213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şahin, M.E.; Blaabjerg, F.; Sangwongwanich, A. A Comprehensive Review on Supercapacitor Applications and Developments. Energies 2022, 15, 674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Chand, P. Supercapacitor and electrochemical techniques: A brief review. Results Chem. 2023, 5, 100885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dar, M.A.; Majid, S.; Satgunam, M.; Siva, C.; Ansari, S.; Arularasan, P.; Ahamed, S.R. Advancements in Supercapacitor electrodes and perspectives for future energy storage technologies. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 70, 10–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Z.; Zhang, L.; Du, T.; Ren, B.; Xu, Y.; Wang, S.; Miao, J.; Liu, Z. A review of carbon materials for supercapacitors. Mater. Des. 2022, 221, 111017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Shi, X.; Peng, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Gong, C.; Dong, C.; Gao, S.; Xu, L.; et al. Biomass pyrolysis for N-doped biochar: Relationship among preparation process, N-doped biochar properties, and supercapacitors. Fuel 2025, 404, 136372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, F.; Ali, M.; Khan, M.; Mbeugang, C.F.M.; Isa, Y.M.; Kozlov, A.; Penzik, M.; Xie, X.; Yang, H.; Zhang, S.; et al. A review of biochar production and its employment in synthesizing carbon-based materials for supercapacitors. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2025, 227, 120830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diop, C.A.B.; Lo, M.; Snoussi, Y.; Gam-Derouich, S.; El Garah, M.; Jouini, M.; Gningue-Sall, D.; Chehimi, M.M. Functional hydrochar/biochar through thermochemical conversion of millet Bran from Senegal: Physicochemical, morphological and electrochemical properties. Emergent Mater. 2025, 8, 2663–2678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.; Rajapaksha, A.U.; Lim, J.E.; Zhang, M.; Bolan, N.; Mohan, D.; Vithanage, M.; Lee, S.S.; Ok, Y.S. Biochar as a sorbent for contaminant management in soil and water: A review. Chemosphere 2014, 99, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Li, C.; Parikh, S.J.; Scow, K.M. Impact of biochar on water retention of two agricultural soils—A multi-scale analysis. Geoderma 2019, 340, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Sharma, K.; Dixit, A.R. Carbon nanotube- and graphene-reinforced multiphase polymeric composites: Review on their properties and applications. J. Mater. Sci. 2019, 55, 2682–2724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassyouni, M.; Mansi, A.E.; Elgabry, A.; Ibrahim, B.A.; Kassem, O.A.; Alhebeshy, R. Utilization of carbon nanotubes in removal of heavy metals from wastewater: A review of the CNTs’ potential and current challenges. Appl. Phys. A 2019, 126, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, J.; Liu, B.; Su, Z. A critical review on the application and recent developments of post-modified biochar in supercapacitors. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 310, 127428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uppugalla, S.; Pothu, R.; Boddula, R.; Desai, M.A.; Al-Qahtani, N. Nitrogen and sulfur co-doped activated carbon nanosheets for high-performance coin cell supercapacitor device with outstanding cycle stability. Emergent Mater. 2023, 6, 1167–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandeep, A.; Ravindra, A.V. Peanut shell-derived porous carbons activated with iron and zinc chlorides as electrode materials with improved electrochemical performance for supercapacitors. Emergent Mater. 2024, 8, 235–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gęca, M.; Khalil, A.M.; Tang, M.; Bhakta, A.K.; Snoussi, Y.; Nowicki, P.; Wiśniewska, M.; Chehimi, M.M. Surface Treatment of Biochar—Methods, Surface Analysis and Potential Applications: A Comprehensive Review. Surfaces 2023, 6, 179–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagemann, N.; Spokas, K.; Schmidt, H.-P.; Kägi, R.; Böhler, M.A.; Bucheli, T.D. Activated Carbon, Biochar and Charcoal: Linkages and Synergies across Pyrogenic Carbon’s ABCs. Water 2018, 10, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velusamy, K.; Isabel, J.B.; Periyasamy, S.; Thiruvenkadam, A.; Ravikumar, H.; Gupta, S.K.; López-Maldonado, E.A. Role of biochar as a greener catalyst in biofuel production: Production, activation, and potential utilization—A review. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2024, 177, 105732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Cao, Y.; Li, J.; Patel, A.K.; Dong, C.-D.; Jin, X.; Gu, C.; Yip, A.C.; Tsang, D.C.; Ok, Y.S. Recent advancements and challenges in emerging applications of biochar-based catalysts. Biotechnol. Adv. 2023, 67, 108181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Zhu, Y.; Niu, Q.; Zeng, G.; Lai, C.; Liu, S.; Huang, D.; Qin, L.; Liu, X.; Li, B.; et al. New notion of biochar: A review on the mechanism of biochar applications in advanced oxidation processes. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 416, 129027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdu, H.I.; Mahmood, S.A.; Aboudou, T.; Guo, Y.; Nian, L.N.; Xiaowei, L.; Ziyu, L.; Jlassi, K.; El-Demellawi, J.K.; Eid, K. Hierarchical porous carbon biochar nanotubes encapsulated metal nanocrystals with a strong metal-carbon interaction for high-performance supercapacitors. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2025, 121, 107476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lima, R.M.A.P.; dos Reis, G.S.; Thyrel, M.; Alcaraz-Espinoza, J.J.; Larsson, S.H.; de Oliveira, H.P. Facile Synthesis of Sustainable Biomass-Derived Porous Biochars as Promising Electrode Materials for High-Performance Supercapacitor Applications. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, K.; Sun, J.; E, L.; Ma, C.; Luo, S.; Wu, Z.; Li, W.; Liu, S. Effects of the Pore Structure of Commercial Activated Carbon on the Electrochemical Performance of Supercapacitors. J. Energy Storage 2022, 45, 103457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Bai, R.; Tian, Y.; Yang, C.; Tian, X. ZnCl2 activation tailoring microporous architecture in wheat straw-derived biochar for enhanced sulfamethoxazole adsorption. J. Water Process. Eng. 2025, 77, 108617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, C.A.; Guerreiro, M.C. Estimation of surface area and pore volume of activated carbons by methylene blue and iodine numbers. Quimica Nova 2011, 34, 472–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chetima, A.; Bup, D.N.; Kewir, F.; Wahaboua, A. Activated carbons from open air and microwave-assisted impregnation of cotton and neem husks efficiently decolorize neutral cotton oil. Heliyon 2024, 10, e24060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, P.K.; Aryal, S.; Oli, H.B.; Shrestha, T.; Jha, D.; Shrestha, R.L.; Bhattarai, D.P. Porosity Analysis of Acacia catechu Seed-derived Carbon Materials Activated with Sodium Hydroxide and Potassium Hydroxide: Insights from Methylene Blue and Iodine Number Methods. J. Nepal Chem. Soc. 2025, 45, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Tang, M.; Abdelaal, A.; Garah, M.E.; Jlassi, K.; Abdullah, A.M.; Chehimi, M.M. Appraisal of a Fistful of Methods for Producing Porous Biochar. ChemRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Shan, R.; Li, W.; Zhang, Y.; Yuan, H.; Chen, Y. Synthesis, Characterization, and Dye Removal of ZnCl2-Modified Biochar Derived from Pulp and Paper Sludge. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 34712–34723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, C.; Liu, B.; Hu, J.; Li, H. Determination of iodine number of activated carbon by the method of ultraviolet–visible spectroscopy. Mater. Lett. 2021, 285, 129137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, M.; Tang, M.; Faye, D.; Vaiyapuri, V.; Jayaram, A.; Mani, N.; Jouini, M.; Chehimi, M.M. Silver-modified sugarcane bagasse biochar-based electrode materials for the electrochemical detection of mercury ions in aqueous media. Electrochim. Acta 2025, 540, 147214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, H.; Zhang, J.; Lin, L.; Liu, J.; Shi, J. Enhanced electrochemical performance of wood derived carbon-based supercapacitor electrodes by freezing and thawing pretreatment salt template method. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2025, 225, 120546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umino, S.; Newman, J. Diffusion of Sulfuric Acid in Concentrated Solutions. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1993, 140, 2217–2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faye, D.; Lo, M.; Seye, D.; Diop, C.A.B.; Diop, M.G.; Ngom, A.; Dieng, M.; Bhakta, A.K.; Gningue-Sall, D.; Chehimi, M.M.; et al. Silver Nanoparticles Supported by Carbon Nanotubes Functionalized with 1,2,3-Benzenetricarboxylic Acid: Spectroscopic Analysis and Electrochemical Capacitance. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. 2025, 35, 7806–7819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, D.; Fernandez, N.B.; Mullassery, M.D.; Surya, R. Iron oxide loaded biochar/polyaniline nanocomposite: Synthesis, characterization and electrochemical analysis. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2020, 119, 108097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Li, C.; Li, D.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, S.; Cui, Z.; Wang, D.; Tang, Y.; Hu, X. Activation of pine needles with zinc chloride: Evolution of functionalities and structures of activated carbon versus increasing temperature. Fuel Process. Technol. 2023, 252, 107987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, S.; Wang, C.; Chen, W.; Liu, C.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, Y. ZnCl2 modified biochar derived from aerobic granular sludge for developed microporosity and enhanced adsorption to tetracycline. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 297, 122381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Zhou, D.; Zhang, J.; Li, F.; Chu, G.; Wu, M.; Pan, B.; Steinberg, C.E. The contrasting role of minerals in biochars in bisphenol A and sulfamethoxazole sorption. Chemosphere 2021, 264, 128490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, D.; Tan, F.; Zhang, C.; Jiang, X.; Chen, Z.; Li, H.; Zheng, Y.; Li, Q.; Wang, Y. ZnCl 2 -activated biochar from biogas residue facilitates aqueous As(III) removal. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2016, 377, 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuff, A.S.; Lala, M.A.; Thompson-Yusuff, K.A.; Babatunde, E.O. ZnCl2-modified eucalyptus bark biochar as adsorbent: Preparation, characterization and its application in adsorption of Cr(VI) from aqueous solutions. S. Afr. J. Chem. Eng. 2022, 42, 138–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minaei, S.; Benis, K.Z.; McPhedran, K.N.; Soltan, J. Evaluation of a ZnCl2-modified biochar derived from activated sludge biomass for adsorption of sulfamethoxazole. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2022, 190, 407–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.; Qin, Q.; Liu, Z. Thermal behavior analysis and reaction mechanism in the preparation of activated carbon by ZnCl2 activation of bamboo fibers. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2024, 179, 106500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.W.; Dallmeyer, I.; Johnson, T.J.; Brauer, C.S.; McEwen, J.-S.; Espinal, J.F.; Garcia-Perez, M. Structural analysis of char by Raman spectroscopy: Improving band assignments through computational calculations from first principles. Carbon 2016, 100, 678–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayiania, M.; Weiss-Hortala, E.; Smith, M.; McEwen, J.-S.; Garcia-Perez, M. Microstructural analysis of nitrogen-doped char by Raman spectroscopy: Raman shift analysis from first principles. Carbon 2020, 167, 559–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, C.; Li, H.; Zhao, L.; Li, Z.; Zhang, C.; Tan, X.; Liu, X. Mechanism of removal and degradation characteristics of dicamba by biochar prepared from Fe-modified sludge. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 299, 113602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biesinger, M.C.; Lau, L.W.; Gerson, A.R.; Smart, R.S.C. Resolving surface chemical states in XPS analysis of first row transition metals, oxides and hydroxides: Sc, Ti, V, Cu and Zn. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2010, 257, 887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nallayagari, A.; Sgreccia, E.; Pasquini, L.; Vacandio, F.; Kaciulis, S.; Di Vona, M.; Knauth, P. Catalytic electrodes for the oxygen reduction reaction based on co-doped (B-N, Si-N, S-N) carbon quantum dots and anion exchange ionomer. Electrochim. Acta 2022, 427, 140861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syahputra, S.; Sgreccia, E.; Nallayagari, A.R.; Vacandio, F.; Kaciulis, S.; Di Vona, M.L.; Knauth, P. Influence of Nitrogen Position on the Electrocatalytic Performance of B,N-Codoped Carbon Quantum Dots for the Oxygen Reduction Reaction. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2024, 171, 066510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, L.; Xu, S.; Liu, R.; Yu, T.; Zhuo, X.; Leng, S.; Xiong, Q.; Huang, H. Nitrogen containing functional groups of biochar: An overview. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 298, 122286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, R.; van Bekkum, H. XPS of nitrogen-containing functional groups on activated carbon. Carbon 1995, 33, 1021–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Tan, H.; Xiong, Y.; Xu, T. Origination and formation of NH4Cl in biomass-fired furnace. Fuel Process. Technol. 2013, 106, 262–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Q.; Zhang, X.; Shen, B.; Ren, K.; Wang, Y.; Luo, J. Enhanced elemental mercury removal via chlorine-based hierarchically porous biochar with CaCO3 as template. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 406, 126828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Donald, T.F.; Kirk, W.; Jia, C.Q. Electrochemical Performance of Pre-Modified Birch Biochar Monolith Supercapacitors by Ferric Chloride and Ferric Citrate. Batteries 2025, 11, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esarev, I.V.; Agafonov, D.V.; Surovikin, Y.V.; Nesov, S.N.; Lavrenov, A.V. On the causes of non-linearity of galvanostatic charge curves of electrical double layer capacitors. Electrochim. Acta 2021, 390, 138896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omidvar, M.; Dalvand, S.; Asghari, A.; Yazdanfar, N.; Sadat, H.Y.; Mohammadi, N. Fabrication of an efficient supercapacitor based on defective mesoporous carbon as electrode material utilizing Reactive Blue 15 as novel redox mediator for natural aqueous electrolyte. Fuel 2023, 347, 128472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Bi, X.; Zhou, T.; Zhou, J.; Zhao, J.; Miao, Z.; Yi, W.; Fu, P.; Zhuo, S. Biochar-based carbons with hierarchical micro-meso-macro porosity for high rate and long cycle life supercapacitors. J. Power Sources 2018, 376, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Rodríguez, C.; Tovar-Martínez, E.; López-Sandoval, R. Oxidative calcination-enhanced KOH activation of d-glucose-derived carbon spheres for high microporosity in supercapacitor electrodes. Electrochim. Acta 2024, 507, 145151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, Z.; Lei, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Jiang, Z.; Hu, J.; Lin, Y. Preparation and specific capacitance properties of sulfur, nitrogen co-doped graphene quantum dots. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2019, 14, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavianfard, S.A.; Molaei, A.; Manouchehri, M.; Foroozandeh, A.; Shahmohammadi, A.; Dalvand, S. Enhanced supercapacitor performance using [Caff-TEA]+[ZnBr3]− ionic liquid electrode in aqueous Na2SO4 electrolyte. J. Energy Storage 2025, 109, 115232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsia, B.; Kim, M.S.; Carraro, C.; Maboudian, R. Cycling characteristics of high energy density, electrochemically activated porous-carbon supercapacitor electrodes in aqueous electrolytes. J. Mater. Chem. A 2013, 1, 10518–10523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, T.; Tian, F.; Wu, J.; Li, H.; Chen, D.; Qi, R.; Niu, Y.; Zhang, F.; Yang, Z. Synthesis of various nanostructured N-doped Cu7S4 materials for aqueous supercapacitors. Electrochim. Acta 2024, 511, 145396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Pan, S.; Wang, B.; Qi, J.; Tang, L.; Liu, L. Asymmetric Supercapacitors Based on Co3O4@MnO2@PPy Porous Pattern Core-Shell Structure Cathode Materials. J. Electrochem. Sci. Technol. 2021, 12, 346–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z.; Wang, F.; Jia, C.; Mu, K.; Yu, M.; Lv, Y.; Shao, Z. Nitrogen and oxygen-codoped carbon nanospheres for excellent specific capacitance and cyclic stability supercapacitor electrodes. Chem. Eng. J. 2017, 330, 1166–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.; Xie, M.; Zhao, S.; Qin, Q.; Huang, F. Materials design and preparation for high energy density and high power density electrochemical supercapacitors. Mater. Sci. Eng. R Rep. 2022, 152, 100713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Liu, W.; Xiao, P.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, G.; Qiu, J. Nano-iron oxide (Fe2O3)/three-dimensional graphene aerogel composite as supercapacitor electrode materials with extremely wide working potential window. Mater. Lett. 2015, 145, 44–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, F.-Y.; Sui, Z.-Y.; Liu, S.; Liang, H.-P.; Zhan, H.-H.; Han, B.-H. Nitrogen-doped carbon aerogels with high surface area for supercapacitors and gas adsorption. Mater. Today Commun. 2018, 16, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tafete, G.A.; Uysal, A.; Habtu, N.G.; Abera, M.K.; Yemata, T.A.; Duba, K.S.; Kinayyigit, S. Hydrother-mally synthesized nitrogen-doped hydrochar from sawdust biomass for supercapacitor electrodes. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2024, 19, 100827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawat, S.; Boobalan, T.; Krishna, B.B.; Sathish, M.; Hotha, S.; Bhaskar, T. Biochar for Supercapacitor Application: A Comparative Study. Chem.—Asian J. 2022, 17, e202200982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, M.; Ma, Z.; Su, H.; Li, Y.; Yang, K.; Dang, L.; Li, F.; Xue, B. Preparation of porous biochar and its application in supercapacitors. New J. Chem. 2022, 46, 21788–21797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nirmaladevi, S.; Boopathiraja, R.; Kandasamy, S.K.; Sathishkumar, S.; Parthibavarman, M. Wood based biochar supported MnO2 nanorods for high energy asymmetric supercapacitor applications. Surf. Interfaces 2021, 27, 101548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, C.-F.; Lin, Y.; Zhao, W.; Wu, T.; Wei, Y.-Y.; Li, X.-H.; Yan, W.-J.; Hao, X.-G. Green preparation of high active biochar with tetra-heteroatom self-doped surface for aqueous electrochemical supercapacitor with boosted energy density. J. Energy Storage 2024, 90, 111872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Lu, Y.; Sun, Y.; Deng, S.; Yang, H.; Zhang, M.; Wang, C.; Yan, J. Impact of Activation Conditions on the Electrochemical Performance of Rice Straw Biochar for Supercapacitor Electrodes. Molecules 2025, 30, 632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madhu, R.; Veeramani, V.; Chen, S.-M.; Veerakumar, P.; Liu, S.-B.; Miyamoto, N. Functional porous carbon–ZnO nanocomposites for high-performance biosensors and energy storage applications. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2016, 18, 16466–16475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kandhasamy, N.; Ramalingam, G.; Murugadoss, G.; Kumar, M.R.; Manibalan, G.; JothiRamalingam, R.; Yadav, H.M. Copper and zinc oxide anchored silica microsphere: A superior pseudocapacitive positive electrode for aqueous supercapacitor applications. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 888, 161489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhao, X.S. On the Configuration of Supercapacitors for Maximizing Electrochemical Performance. ChemSusChem 2012, 5, 818–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khomenko, V.; Frackowiak, E.; Béguin, F. Determination of the specific capacitance of conducting polymer/nanotubes composite electrodes using different cell configurations. Electrochim. Acta 2005, 50, 2499–2506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szkoda, M.; Ilnicka, A. Enhanced electrochemical capacitance of TiO2 nanotubes/MoSe2 composite obtained by hydrothermal route. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2024, 681, 161490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Electrode Materiels | Electrolyte | Current Density (A g−1) | Csp (F g−1) | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fe2O3/GA | 0.5 M Na2SO4 | 1 | 81.3 | [66] |

| NCA | 1 M H2SO4 | 0.1 | NCA-800: 166 NCA-900: 136 | [67] |

| HC2 | 2 M KOH | 0.5 | 80 | [68] |

| Biochar litchi seed | 1 M H2SO4 | 1 | 190 | [69] |

| Biochar apricot shell | 3 M KOH | 0.5 | 216 | [70] |

| BC@MnO2 | 1 M Na2SO4 | 0.5 | 512 | [71] |

| SGB-700 | 1 M H2SO4 | 0.5 | 638 | [72] |

| RSBC | 6 M KOH | 0.2 | RSBC: 197.2 RSBC-2: 296 | [73] |

| P700(p) | 0.5 M H2SO4 | 0.5 | 440 | This work |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Diop, C.A.B.; Faye, D.; Lo, M.; Bakiri, D.; Wang, H.; El Garah, M.; Sharma, V.; Mahajan, A.; Jouini, M.; Gningue-Sall, D.; et al. Engineering Porous Biochar for Electrochemical Energy Storage. Surfaces 2025, 8, 87. https://doi.org/10.3390/surfaces8040087

Diop CAB, Faye D, Lo M, Bakiri D, Wang H, El Garah M, Sharma V, Mahajan A, Jouini M, Gningue-Sall D, et al. Engineering Porous Biochar for Electrochemical Energy Storage. Surfaces. 2025; 8(4):87. https://doi.org/10.3390/surfaces8040087

Chicago/Turabian StyleDiop, Cheikh Ahmadou Bamba, Déthié Faye, Momath Lo, Dahbia Bakiri, Huifeng Wang, Mohamed El Garah, Vaishali Sharma, Aman Mahajan, Mohamed Jouini, Diariatou Gningue-Sall, and et al. 2025. "Engineering Porous Biochar for Electrochemical Energy Storage" Surfaces 8, no. 4: 87. https://doi.org/10.3390/surfaces8040087

APA StyleDiop, C. A. B., Faye, D., Lo, M., Bakiri, D., Wang, H., El Garah, M., Sharma, V., Mahajan, A., Jouini, M., Gningue-Sall, D., & Chehimi, M. M. (2025). Engineering Porous Biochar for Electrochemical Energy Storage. Surfaces, 8(4), 87. https://doi.org/10.3390/surfaces8040087