1. Introduction

Molecular interactions form the backbone of biological systems, driving everything from DNA structure and protein folding to the binding of ligands to specific cell surface receptors that initiate intracellular signaling cascades, leading to various cellular responses. These interactions shape bioengineering applications, from drug delivery to tissue engineering. By understanding and manipulating these forces, scientists can design novel proteins, create targeted therapies, and develop biomaterials that mimic natural tissues, pushing the boundaries of medical and industrial innovation. The strength of the interactions, in turn, depends on the specific species (ionization state) of the involved molecules. Therefore, knowing the pKa value of biological molecules in their environment is of paramount importance.

It has been known for a long time that the pKa of a functional group varies with the environment due to specific interactions of each chemical species. For instance, Forsythe et al. investigated the relationships between protein structure and ionization of carboxyl groups in several proteins of known structure. They found that burial of carboxyl groups leads to dispersion in pKa values: pKa values for solvent-exposed groups show narrow distributions, while values for buried groups range from <2 to 6.7. Aspartates and glutamates at the N-termini of helices have mean pKa values lower than the overall mean values [

1].

For small organic molecules, the use of macrocyclic host molecules has been studied as an interesting strategy to control the ionization states of drugs and thus promote their release in the desired target region. This kind of encapsulation of ionizable molecules can modify their apparent pKa values by modifying the local chemical environment and providing specific interactions with a particular chemical species. For instance, supramolecular host-guest studies of acridine dye with cyclodextrin macrocycles indicate that the neutral form of the dye undergoes significant interaction with the cyclodextrin hosts, forming mainly a 1:1 stoichiometric host-guest complex. Unlike the neutral form, the protonated form of the dye does not show any significant interaction with the hosts. This differential interaction results in a decrease in the apparent pKa values for the dye in the presence of the cyclodextrins [

2]. Shinde et al. investigated the host–guest interactions, and the consequent modulation in the prototropic equilibrium of a phenazine dye with calixarenes macrocyclic hosts. Both forms of dyes formed inclusion complexes with the host, with a larger binding constant for the latter due to the cation receptor behavior of the calixarenes. The distinct differences in the binding constant provided a finite tuning of pKa between 6.5 and 8.8 [

3]. In a different study, Saleh et al. demonstrated that a pKa shift as high as 4 can be induced in thiabendazole, a widely used agricultural fungicide, when it binds to a cucurbituril macrocycle [

4].

Here, we propose an alternative manner of regulating the apparent pKa value, which can be applied in amphiphilic molecules that form supramolecular structures, such as fatty acids.

Fatty acids are an important component of lipids in cells of all kingdoms. They consist of a single hydrocarbon chain and a carboxyl group (―COOH) as the polar headgroup, which makes them acidic with a pKa value of 4.8 when dissolved in an aqueous solution [

5,

6]. Fatty acids with short chain lengths are very soluble, while those with long chain lengths have relatively low solubility values. Fatty acids with intermediate lengths fall between the soluble and insoluble groups of this molecular class [

7]. The aggregation properties of these fatty acids are pH-dependent and have been largely studied. These molecules show different spontaneous arrangements depending on the protonation/ionization ratio of the terminal carboxylic acid: emulsions form at low pH, micelles at high pHs and vesicles at intermediate values [

8,

9,

10].

The formation of fatty acid vesicles is restricted to a rather narrow pH range (between 7–9), where molecules with ionized and unionized carboxylic groups coexist [

11,

12,

13]. Fatty acid vesicles always contain two types of amphiphiles, the non-ionized, neutral form and the ionized form (the negatively charged soap), and their ratio is critical for the vesicle stability. Therefore, fatty acid vesicles are actually mixed “fatty acid/soap vesicles”. This is because under these conditions, a hydrogen bond network between the ionized and the neutral form of the fatty acid forms [

9]. Even within this narrow pH range where vesicles exist, subtle changes in pH affect membrane properties due to effects on the strength of the hydrogen bonding. In the case of oleic acid, the rupture tension of membranes, water penetration, ion permeability, pore formation rates, and membrane disorder change in vesicles within pH 8 and 9 [

14].

Compared with vesicles formed by phospholipids, fatty acid vesicles are very dynamic, since they are composed of single-chain amphiphiles. The concentration of non-associated monomers in equilibrium with vesicles is considerably higher than in the case of double-chain lipids. Flip-flop of molecules between the two leaflets of the bilayers and the exchange between fatty acid vesicles via monomers are expected to occur more rapidly than in the case of liposomes formed from double-chain lipids [

9].

The specific pH range where vesicle form depends on the chemical structure of fatty acids. Fatty acids with a longer aliphatic chain tend to form vesicles at a higher pH, because the molecules can be packed more tightly in the membrane [

9]. It should be noted that when anionic surfactants form an aggregate, the local pH value at the aggregate surface is lower than the measured pH (the bulk solution pH) due to the electrostatic attraction between the charged surface of the aggregate and the protons of the solution [

15,

16]. Therefore, the determined pKa values correspond to the pH in the bulk of the solutions at which the degree of protonation of the molecules in the aggregate is 50%, and they are usually called “apparent pKas”.

As previously indicated, completely ionized fatty acids form micelles [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13], this being the more stable aggregate arrangement for the fatty acid anions. On the contrary, when completely neutral fatty acids form emulsions (oil droplets of the neutral fatty acid suspended in water) [

12,

17]. We hypothesized that this dependence of the shape of the aggregate on pH could affect the apparent pKa of fatty acids when they are confined in a specific supramolecular arrangement, where the dynamic coupling between the degree of ionization and the aggregation shape breaks down. To test this, we studied the apparent pKa value of oleic acid in free suspension (and, therefore, organized in micelles, vesicles, or droplets, depending on the degree of ionization), or fixed onto a surface. This fatty acid forms vesicles at a measured pH value of about 8 [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. We found that forcing the molecule to remain in a planar supramolecular arrangement leads to a shift in the apparent pKa value of about two pH units compared to the value obtained when the surfactant is allowed to adopt the spontaneous aggregate type. We proposed that this strategy can be applied for generating surfaces with the same chemical covering, but with different sensitivity to the local pH, and therefore, with different surface charge, adherence properties and absorption capacity to different chemical species in solution by modulating surface rugosity.

Fatty acids are eco-friendly molecules that have diverse applications, including in the production of soaps, detergents, and cosmetics; as lubricants and fuel components; in food and animal feed; and for creating polymers, coatings, and phase change materials for energy storage [

18]. They are also used in healthcare and medicine for dietary supplements and therapeutic agents [

18]. Therefore, understanding the behavior of surfaces covered by these molecules would result in broadening their possible applications.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Reagents

Oleic acid (C18H34O2, OA) and NaCl were provided by Sigma–Aldrich (Darmstadt, Hesse, Germany). NaOH (EMSURE) was from Merck (Darmstadt, Hesse, Germany). HCl and H2O2 were from Cicarelli (San Lorenzo, Santa Fe, Argentina), and H2SO2 was from Anedra (Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires, Argentina). A piranha solution was prepared before its use and handled with caution. Glass spheres (disruptor beads) with a 0.5 mm diameter were acquired from Scientific Industries Inc. (Bohemia, NY, USA). The water used to prepare solutions was deionized with a resistivity of 18 MΩcm and filtered with an Osmoion system (Apema, Quilmes, Buenos Aires, Argentina).

2.2. Hydrodynamic Size Determinations

The OA suspensions were prepared by mixing 500 μL of OA with a 150 mM NaCl solution at a final volume of 10 mL (0.158 M final OA concentration). The suspensions were vortexed for 10 s, taken to a bath at 80 °C for 1 min, vortexed for 20 s, taken to a bath at 0 °C for 2 min and vortexed again for 20 s. The procedure was repeated nine times to assure proper surfactant hydration. Subsequently, the suspensions were sonicated for two cycles (5 min sonication, 30 s pause) in a4710 Series 50WUltrasonic Homogenizer (Cole Palmer, Champaign, IL, USA) with a 3.8 mm diameter tip at 40% of amplitude. Finally, the pH of the suspensions was adjusted to the desired value by adding HCl. The hydrodynamic size distribution of the aggregates was determined by Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) using the submicron particle sizer Nicomp 380 ZLS (Particle Sizing Systems, New Port Richey, FL, USA). Determinations were performed at pH 4.2, 7.2 and 9.5.

2.3. Bead Cleaning Procedure

30 g of the commercial disruptor beads were cleaned with piranha solution (15 mL of hydroxide peroxide was added slowly to sulfuric acid, handled with extreme caution). The mixture of beads, sulfuric acid and hydrogen peroxide was slowly homogenized and placed on a heating plate at 80 °C for one hour. The solution was allowed to cool, and the piranha solution was discarded. The beads were rinsed in ultrapure water until a neutral pH was reached. Once the water from the final wash was discarded, the beads were dried on an oven at 40 °C.

2.4. Fixation of the Oleic Acid Molecules onto the Bead’s Surface

To fix the OA molecules in a planar arrangement, the surfactant was adhered to clean glass beads. The OA suspension previously prepared was added in a beaker containing the clean and dry beads and a magnetic stir bar. The OA was allowed to adhere to the glass surface for 1 h with stirring, and for 24 h quiescent. The supernatant was removed, and beads were rinsed with NaCl solutions at pH 10, 6 to 10 times to eliminate not adhered OA molecules. Finally, a NaCl solution was added until it reached a level of 2 mm above the level of the beads, where the electrode for pH determination was placed. The pH was brought to 12 before titration.

2.5. Titration Procedure

Titration was performed using OA in aqueous suspensions or adhered on millimeter-sized beads. In both cases, the samples were brought to the initial pH by adding NaOH, and titration was performed by adding HCl while stirring using a Digital Top Buret Burette H 50 mL (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany). pH was determined with a pH electrode connected to aFiveEasy FE20 pH Meter (Mettler Toledo, Columbus, OH, USA) after each addition.

3. Results and Discussion

In order to compare the aggregation process of our oleic acid (OA) samples with those in the literature, we first determined the hydrodynamic size of the aggregates formed at pH 4.2, 7.2 and 9.5 using Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS). The diameter histograms are shown in

Figure 1. The number-weighted histogram shows that at basic pHs, most particles are small (10 nm or smaller), while at pH 7.2, the most probable size is 50 nm and at 4.2, 80 nm. The inset shows the volume-weighted histograms, which emphasize larger particles because they contribute more to the total volume than many smaller particles. From these histograms, we identified a small number of particles of 40 nm at pH 9.5, 550 nm at pH 7.2 and 600 nm at pH 4.2 that coexist with the smaller particles.

Dejanovic et al. clearly demonstrated the formation of OA vesicles at a particular range of pH [

12]. They determined the captured volume inside the aggregates as a function of pH using OA samples with entrapped spin-labeled glucose, adding sodium ascorbate to the samples. Sodium ascorbate rapidly reduces the paramagnetic nitroxide group of the accessible spin-labeled glucose, leading to a molecule that does not give an ESR signal. Therefore, only the non-entrapped spin-labeled glucose molecules were reduced after the addition of sodium ascorbate to the samples. They obtained a range of pH with increased entrapped volume, with the highest entrapment yield in the pH range 9.9 > pH > 8.5, in agreement with previous studies [

9,

17]. Lower or higher pHs lead to a decrease in the captured volume inside the aggregate, indicating the absence of vesicles. According to the EPR lipophilic TEMPO-spin labels motion, they concluded that the shape transition at the low pH range corresponds to a vesicles to oil droplets transition [

17]. In this regard, oil/water emulsion was also shown for dodecanoic acid using phase contrast microscopy [

19,

20]. However, further studies indicated that in the low pH range, the obtained emulsion system was not composed of pure oleic acid droplets but condensed aggregates of lamellar bilayers [

21].

In summary, experimental evidence for OA samples indicates that micelles and monomers coexist at high pHs, vesicles predominate at pH = pKa, and the solution transforms into a milky emulsion of the oil and water phases with further reduction in pH value. These shape transitions are reversible and are caused by the change in the degree of ionization of oleic acid. This behavior was reproduced using Molecular Dynamics Simulations [

22]. The hydrodynamic sizes shown in

Figure 1, together with the milky appearance of the samples at low pHs, are in agreement with the reported pH-dependent aggregation process of the fatty acid samples in general, and for OA samples in particular [

9,

17]. We will here focus on the neutral-to-basic transition, where OA completely ionizes, which corresponds to the vesicle-to-micelle shape transition.

To find the apparent pKa value of OA molecules, samples were taken to basic pHs, and titration was performed with 2 mM HCl. The pH was determined after each acid addition, and the buffer capacity (β) of the suspensions was calculated as β = −dna/dpH, where dna is the number of moles of the acid added, and dpH is the determined change in pH. The derivative was obtained from a fitting of the experimental curves with a dose–response equation. The buffer capacity (β) of a solution shows a maximum at pH = pKa, thus the pKa value was obtained from this maximum.

This titration was performed using suspensions of 0.16 M OA, a concentration higher than that at which OA forms aggregates (critical aggregate concentration, CAC). The reported CAC values are 3 μM at acid pHs, 15 μM for neutral solutions and 50 μM at basic conditions [

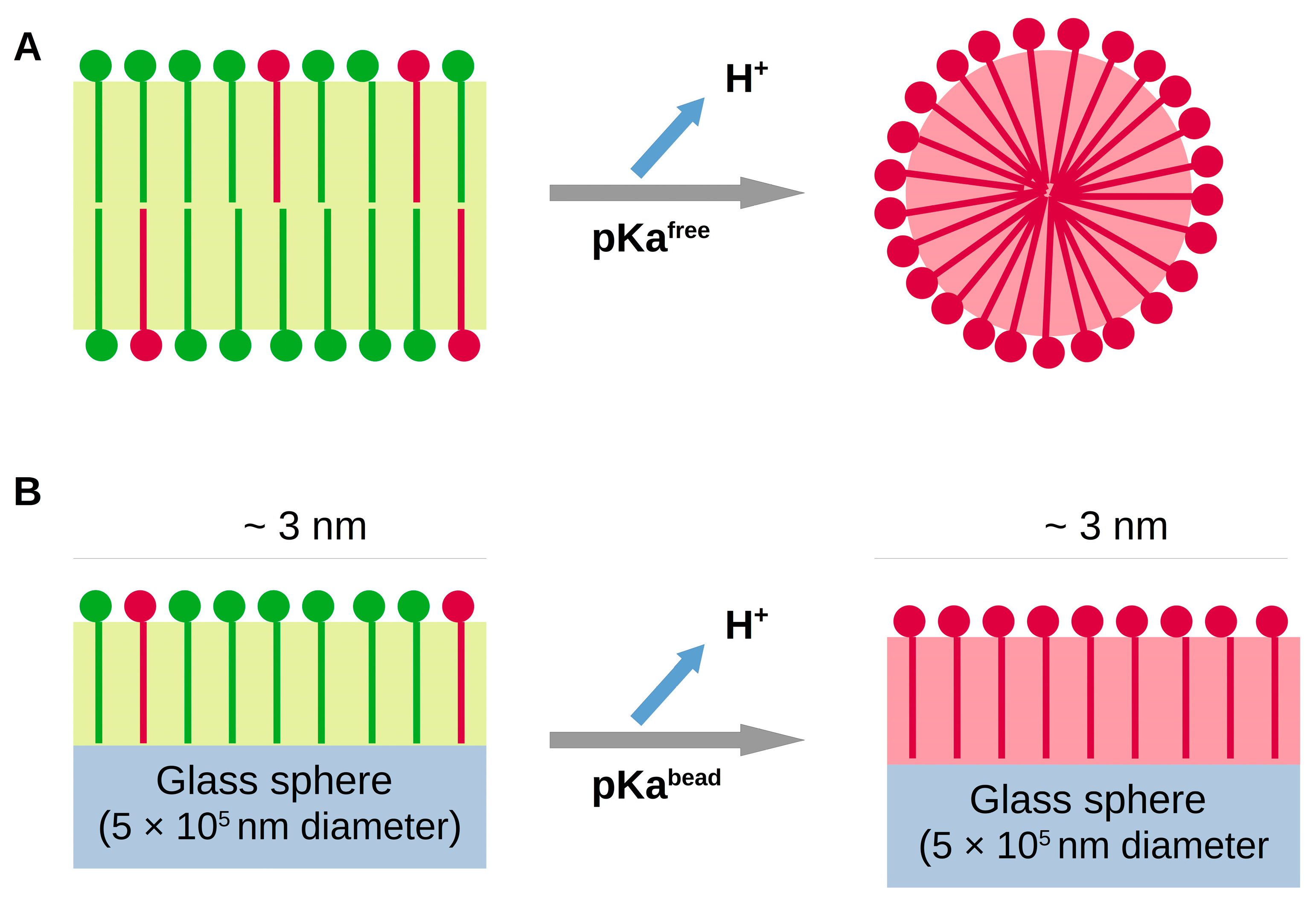

23]. Therefore, the OA molecules were initially forming micelles, and during titration, a transition to vesicles occurred. The acid/base equilibria of OA, together with the aggregation transition due to ionization (from vesicles to micelles due to media alkalinization) are schematized in

Figure 2A.

Figure 3A shows a titration curve for OA molecules in suspension, which is in agreement with previous reported results for fatty acid titrations [

8,

9,

10]. The corresponding β-pH curve is shown in

Figure 3B (insets show the controls). This experiment was repeated three times, and from the maxima of the corresponding β-pH curves, an average apparent pKa (pKa

free) of 8.4 ± 0.3 was obtained, consistent with reported values [

5,

6,

7]. The peaks have an average width of approximately 1 pH unit.

This pKa value is much larger than the 4.8 value reported for OA monomers [

5,

6,

22]. However, it has to be recalled that a bulk pH of 8.4 corresponds to a more acidic pH near a charged interface, such as that on the surface of partially ionized OA vesicles. This pH decay can be estimated considering the Gouy–Chapman model, a Boltzmann distribution of proton ions attracted by the anionic surface leads to a pH change of: pHs = pHb + FV/2.3RT [

15,

16,

24]. Here, pHs and pHb correspond to the pH close to the surface and in bulk, respectively. F is the Faraday constant (96,500 C/mol), V is the surface potential, R is the ideal gas constant (8.314 J/Kmol), and T is the absolute temperature (298 K). The zeta potential is the experimentally accessible parameter most similar to the surface potential, both values being very close at low ionic strength [

25]. Teo et al. reported the zeta potential of oleic acid vesicles suspended in 50 mM borate buffer, pH 9, and found a value of −90 mV [

26]. Considering this value for the surface potential, a bulk pH close to 7 (1.5 units lower than that in the surface) is found for a near 50% degree of ionization in the vesicles. This value is still higher than the pKa for the monomers, indicating that neutralizing the monomer requires a higher proton concentration than neutralizing the molecule in the vesicle. Thus, the relative stability of the neutral species compared to the charged one increases when OA forms aggregates. This may be related to the formation of oil drops when OA is protonated, thus hiding the hydrophobic regions from water.

A value close to 7 was also found for OA forming mixed vesicles with phospholipids [

6,

22,

27]. Using Molecular Dynamics Simulations, Janke et al. found that the free energy change in the charged OA for moving from water into an aggregate was different from that for the neutral species. From the difference in the free energy changes, the shift in pKa in the different bilayers was estimated, and values similar to the experimental ones were found [

22]. This highlights the relevance of the supramolecular arrangement in the ionization behavior of OA molecules.

We next performed similar experiments using suspensions of glass spheres covered with OA molecules. In this case, since the glass spheres are large compared to the molecular size, the fatty acids are obliged to remain in a flat structure at all the pHs (see

Figure 2B).

A titration curve is shown in

Figure 4A, and the corresponding β-pH curve is shown in

Figure 4B (the insets correspond to controls of the glass spheres without OA). Two pieces of evidence confirm that the titrated species are attached to the glass. First, we performed titrations after 6 or 10 cycles of bead rinsing. In the 6 cycle-rinsing experiments, we observed a small peak around pH 7, corresponding to OA molecules in suspension. This peak was not observed after 10 cycles of rinsing, indicating that the amount of non-adhered OA molecules was negligible. Additionally, the supernatant of the last rinsing cycle was titrated, and a signal similar to the control in the insets of

Figure 3 was obtained.

The average apparent pKa value (pKa

bead) obtained from three independent experiments was 10.2 ± 0.2, with an average peak width of about 2 pH units. Thus, the apparent pKa value shifted to more basic values compared to that found for free OA molecules. The OA molecules adhered to the glass surfaces are restricted to a planar arrangement even at high pHs, as schematized in

Figure 2B. This planar structure favors a 0.5 ionization degree, thus stabilizing this state, which translates to an increase in the apparent pKa, and to a higher pH range of the half-ionized state (wider peaks).

Our results show that when the OA molecules are confined to a flat arrangement, a 100 times higher hydroxide concentration is required for ionization.

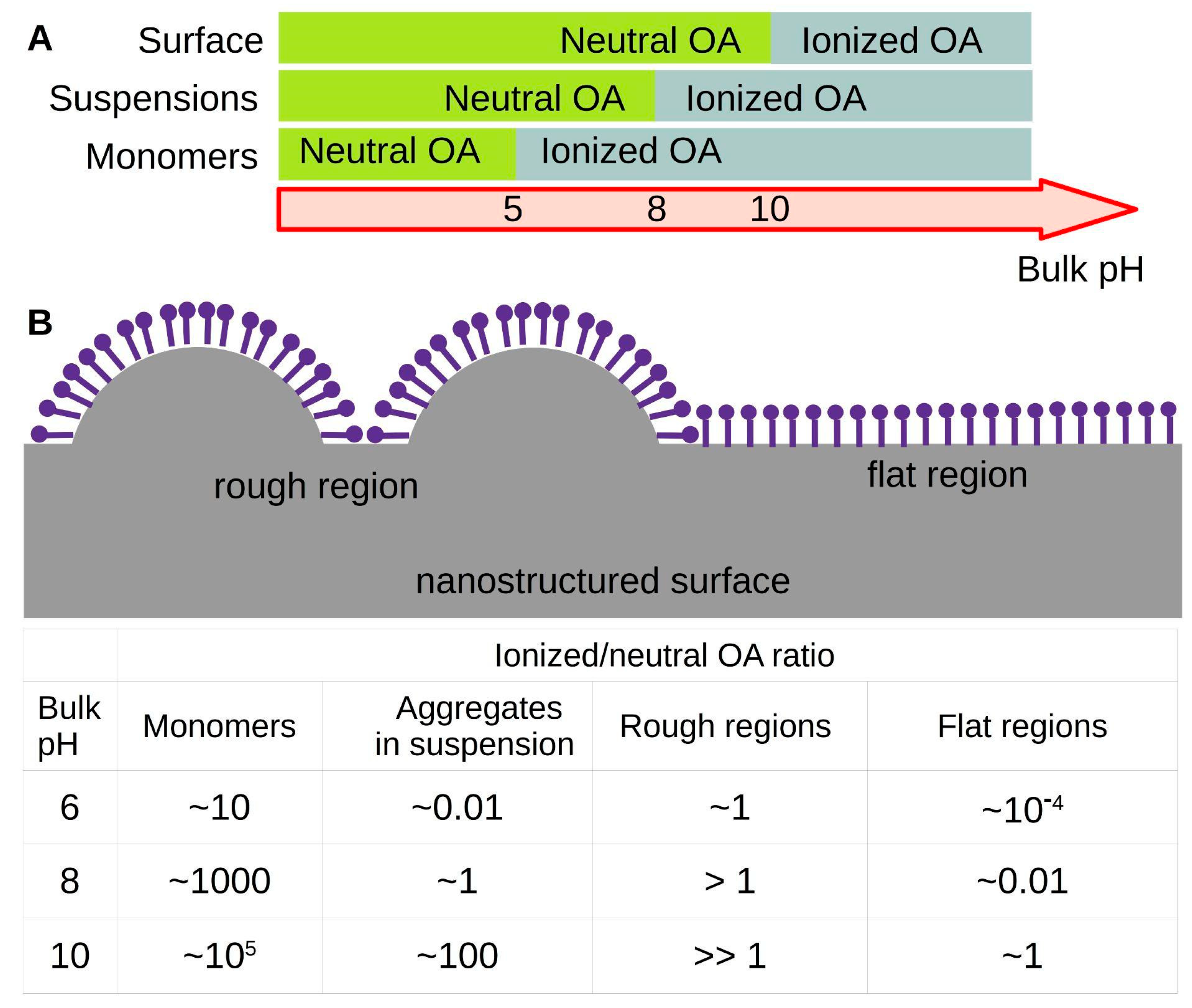

Figure 5A shows a pH line that indicates the most abundant species for the three cases: monomers in solution, aggregates in suspensions and molecules attached onto a surface.

The opposite pKa shift would occur when OA molecules are restricted to a highly curved arrangement that stabilizes the ionized state. In this case, a decrease in the apparent pKa value would occur, since higher amounts of protons would be necessary to protonate the OA molecules. We propose that this coupling between the type of supramolecular arrangement and the acidity of the amphiphile can be exploited to control surface charge by regulating the surface roughness, using nanostructured surfaces, such as those synthetized as platforms for Surface Plasmon Resonance, with nanoparticles within 10 to 100 nm [

28,

29].

Figure 5B shows a cartoon illustrating the proposed regulation of local surface charge with surface topography for a surface covered by OA molecules. The estimated degree of ionization is given, considering the apparent pKa of OA monomers, aggregates suspended in solutions (above the CAC), or OA molecules on a flat surface determined here. We also estimated a value of 6 for OA molecules in a nanostructured surface; this speculative value intends to illustrate the effect of nanometer-sized rugosity on OA ionization state.