Impact of Mo Substrate Roughness on the Stability and Properties of Diamond Films for Aerospace Applications

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

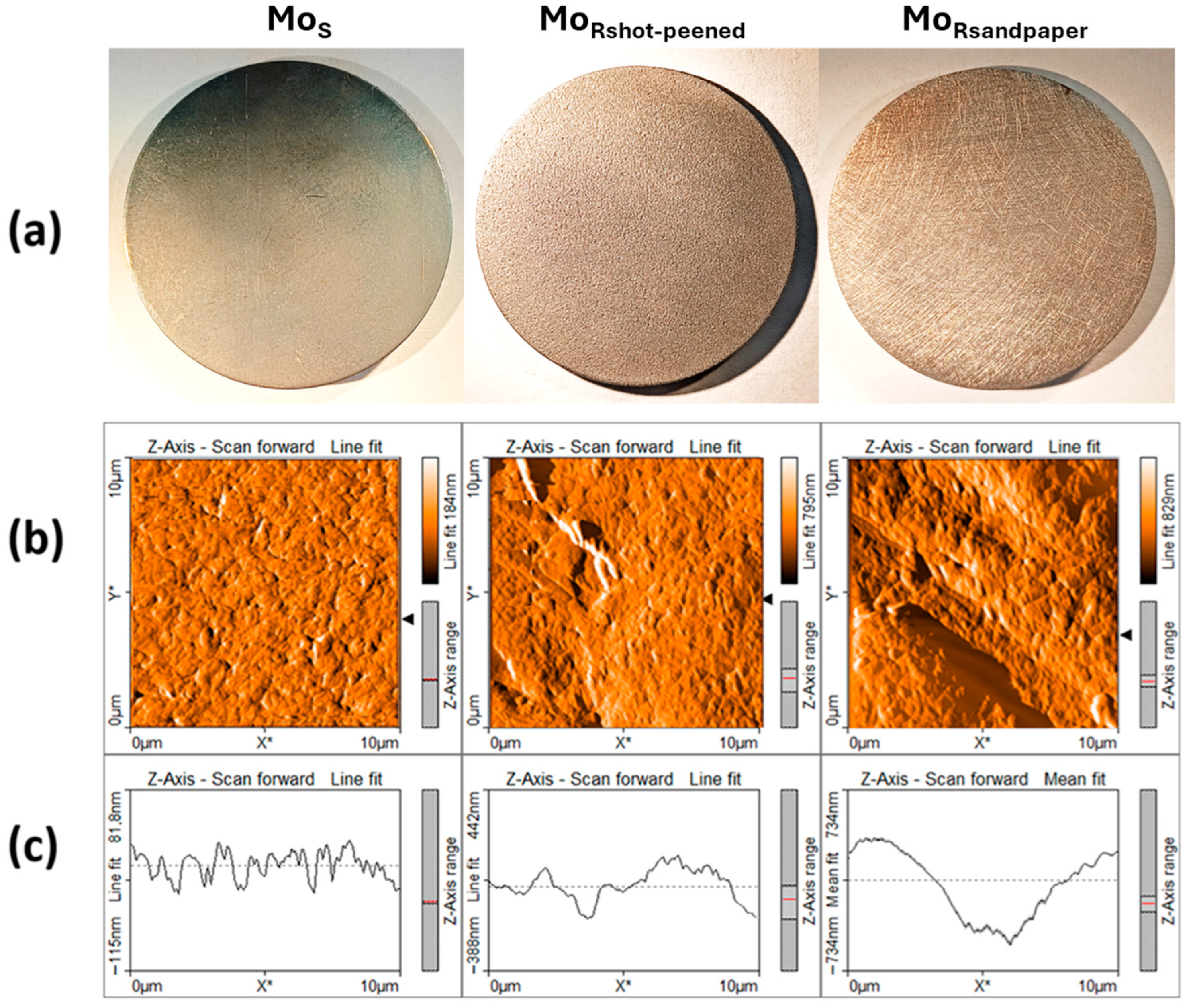

2.1. Substrate Preparation

2.2. Diamond Deposition via MWPECVD Technique

2.3. Process Diagnostics: Pyrometric Interferometry (PI)

- The two wavelengths allow automatic compensation for artificial signals caused by variations in emissivity;

- The wavelengths chosen allow the specimen surface to be observed through the plasma without contributions from the latter;

- The long-term stability of the calibration is useful for monitoring processes or controlling applications where accurate and reproducible results can be crucial;

- The values of the quality factor known as Signal Dilution Factor (500:1) are high;

- The optical fiber allows the sensor to be placed in more convenient and remote zones.

2.4. Diamond Film Characterization

2.5. Erosion Tests in Ar Plasma

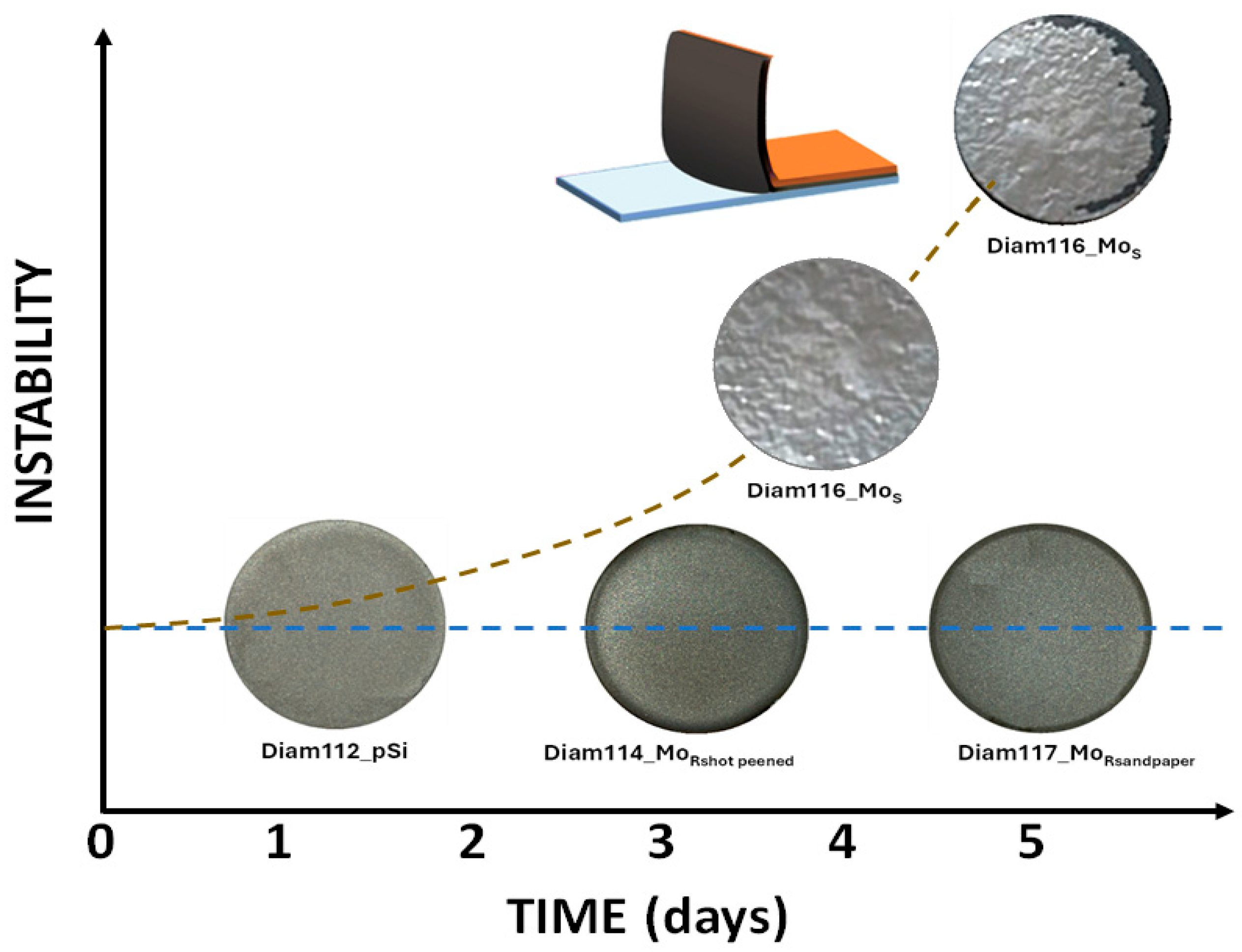

3. Results and Discussion

4. Preliminary Tests on Cathode Erosion in Plasma

- A rough substrate surface is better than a smooth one for the growth of diamond films on molybdenum using the MWPECVD technique;

- The use of a rough Mo substrate reduces the deposition temperature (TD);

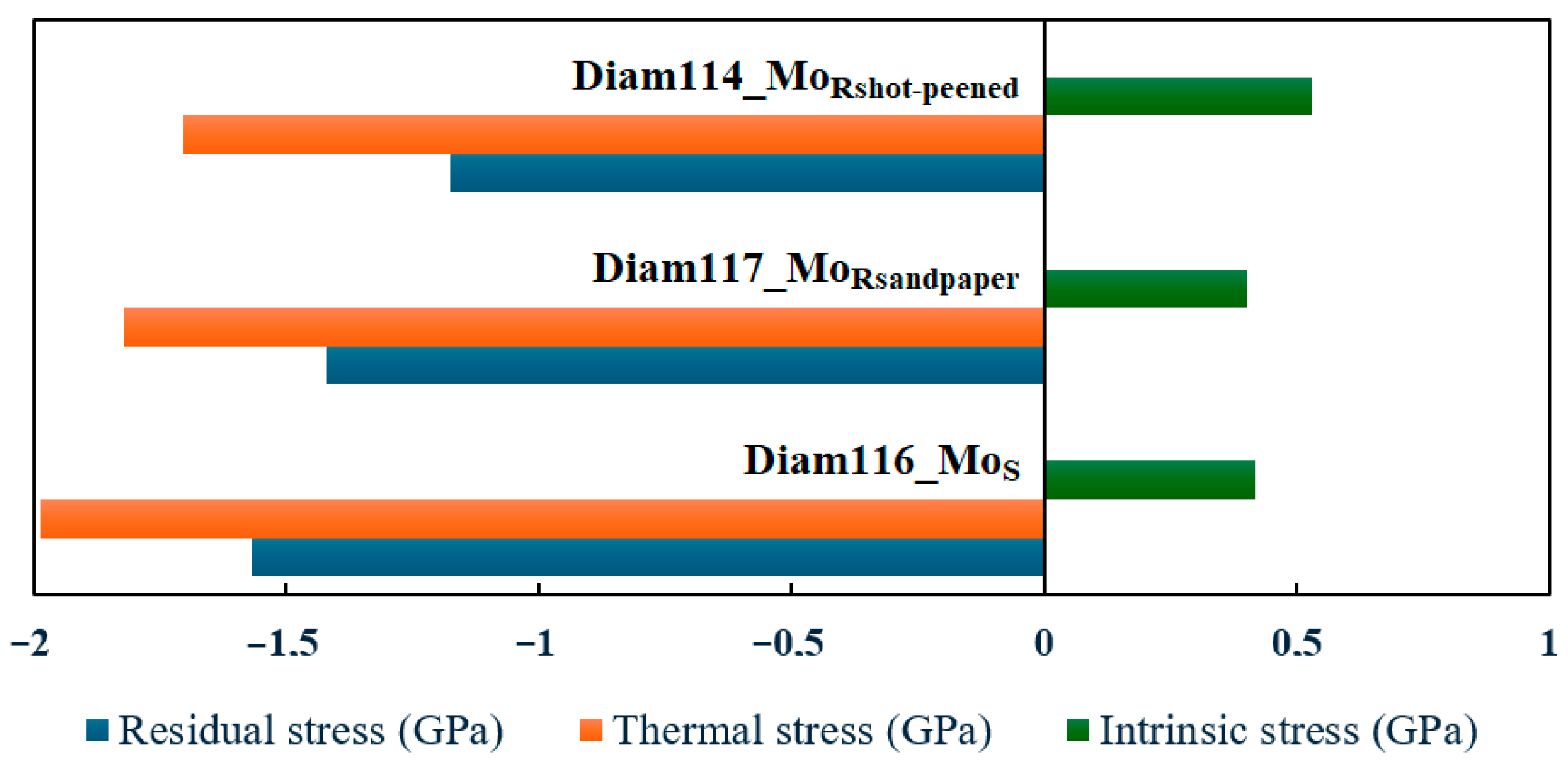

- The decrease in TD leads to a reduction in residual and thermal stresses;

- A more uniform substrate roughness (MoRshot-peened) improves film stability and further reduces the deposition temperature (i.e., lower stress in the film) with the above-mentioned advantages.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CVD | Chemical Vapor Deposition |

| HFCVD | Hot Filament Chemical Vapor Deposition |

| MWPECVD | Microwave Plasma-Enhanced Chemical Vapor Deposition |

| NCD | Nanocrystalline Diamond |

| PI | Pyrometric Interferometry |

| LRI | Laser Reflectance Interferometry |

| AFM | Atomic Force Microscopy |

| XRD | X-Ray Diffraction |

| FIB | Focused Ion Beam |

| SEM | Scanning Electron Microscopy |

| PID | Proportional Integral Derivative |

| FWHM | Full Width at Half Maximum |

| RF | Radio Frequency |

References

- Mckeag, R.D.; Chan, S.S.M.; Jackman, R.B. Polycrystalline diamond photoconductive device with high UV-visible discrimination. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1995, 67, 2117–2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muscarella, M.F.; Altamura, D.; Brescia, R.; Capitelli, M.; Casamassima, G.; Cassano, T.; Celiberto, R.; Cicala, G.; Cornacchia, D.; De Giacomo, A.; et al. A comparative study on comb electrodes devices made of MWPECVD diamond films grown on p-doped and intrinsic silicon substrate. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2011, 20, 1005–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velardi, L.; Valentini, A.; Cicala, G. Highly efficient and stable photocathode based on nanodiamond particles. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2016, 108, 083503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jou, S.; Huang, B.-R.; Wu, M.-C. Nanocrystalline diamond film as cathode for gas discharge sensors. Thin Solid Film. 2010, 518, 4458–4461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwala, J.; Chatterjee, C.; Cicala, G.; Cicuttin, A.; Ciliberti, P.; Crespo, M.L.; Dalla Torre, S.; Dasgupta, S.; Gregori, M.; Levorato, S.; et al. Study of MicroPattern Gaseous detectors with novel nanodiamond based photocathodes for single photon detection in EIC RICH. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A Accel. Spectrometers Detect. Assoc. Equip. 2020, 952, 161967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Lin, C.; Zhang, J. High performance field emission cathode based on the diamond nanowires prepared by nanocrystalline diamond films annealed in air. J. Micromech. Microeng. 2024, 34, 025011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.L.; Liao, K.J.; Fang, L.; Esteve, J.; Polo, M.C. Analysis of diamond nucleation on molybdenum by biased hot filament chemical vapor deposition. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2001, 10, 383–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicala, G.; Velardi, L.; Senesi, G.S.; Picca, R.A.; Cioffi, N. Electrical current at micro-/macro-scale of undoped and nitrogen-doped MWPECVD diamond films. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017, 426, 456–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köpf, A.; Lux, B.; Haubner, R. Substrate Effects during Nucleation and Growth of CVD diamond. New Diam. Front. Carbon Technol. 2001, 11, 11–23. [Google Scholar]

- Behera, M.; Jena, A.; Pattnaik, S.K.; Padhi, S.; Sarangi, S.K. The effect of transition-metal seeding powder on deposition and growth of diamond synthesized by hot filament chemical vapor deposition processes on cemented carbide substrates and its characterization. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2020, 256, 123638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoner, B.R.; Ma, G.H.M.; Wolter, S.D.; Glass, J.T. Characterization of bias-enhanced nucleation of diamond on silicon by invacuo surface analysis and transmission electron microscopy. Phys. Rev. B 1992, 45, 11067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meilunas, R.; Wong, M.S.; Sheng, K.C.; Chang, R.P.H.; Van Duyne, R.P. Early stages of plasma synthesis of diamond films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1989, 54, 2204–2206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jubber, G.; Milne, D.K. Microwave Plasma CVD of High Quality Heteroepitaxial Diamond Films. Phys. Status Solidi A 1996, 154, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lux, B.; Haubner, R. Diamond substrate interactions and the adhesion of diamond coatings. Pure Appl. Chem. 1994, 66, 1783–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashfold, M.N.R.; May, P.W.; Rego, C.A.; Everitt, N.M. Thin film diamond by chemical vapour deposition methods. Chem. Soc. Rev. 1994, 23, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trava-Airoldi, V.J.; Corat, E.J.; Santos, L.V.; Moro, J.R.; Leite, N.F. Studies of molybdenum surface modification for growth of adherent CVD diamond Films. Mater. Res. 2003, 6, 305–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buijnsters, J.G.; Shankar, P.; van Enckervort, W.J.P.; Schermer, J.J.; ter Meulen, J.J. Adhesion analisis of polycrystalline diamond films on molybdenum by means of scratch, indentation and sand abrasion testing. Thin Solid Film. 2005, 474, 186–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wako, H.; Abe, T.; Takagi, T.; Ikohagi, T. Comparison of diamond film adhesion on molybdenum substrates with different surface morphologies. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2009, 256, 1466–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ristić, G.S.; Bogdanov, Ž.D.; Zec, S.; Romčević, N.; Dohčević-Mitrović, Z.; Miljanić, Š.S. Effect of the substrate material on diamond CVD coating properties. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2003, 80, 529–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallik, A.K.; Binu, S.R.; Satapathy, L.N.; Narayana, C.; Seikh, M.M.; Shivashankar, S.A.; Biswas, S.K. Effect of substrate roughness on growth of diamond by hot filament CVD. Bull. Mater. Sci. 2010, 33, 251–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, S. Nucleation of diamond films on heterogeneous substrates: A review. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 10159–10182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicala, G.; Bruno, P.; Bénédic, F.; Silva, F.; Hassouni, K.; Senesi, G.S. Nucleation, growth and characterization of nanocrystalline diamond films. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2005, 14, 421–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; He, L.; Li, Y.; Yang, Q. Diamond Deposition on Iron and Steel Substrates: A Review. Micromachines 2020, 11, 719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akatsuka, F.; Shimura, F. Effect of Substrate Materials on CVD diamond Growth. Mater. Sci. Monogr. 1991, 73, 379–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buijnsters, J.C.; Celis, J.-P.; Hendrikx, R.W.A.; Vázquez, L. Metallic Seed Nanolayers for Enhanced Nucleation of Nanocrystalline Diamond Thin Films. J. Phys. Chem. C 2013, 117, 23322–23332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Dai, W.; Qian, L.; Li, M.; Sun, D.; Gao, C.; Yang, B. Effect of metallic seed layers on the properties of nanocrystalline diamond films. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2014, 49, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, A.; Neves, A.; Silva, R.F.; Nazaré, M.H. Evaluation of MPCVD diamond film adhesion on hard metal substrates by micro Raman spectroscopy. Diam. Relat. Mater. 1997, 6, 769–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicala, G.; Brescia, R.; Nitti, M.A.; Romeo, A.; Altamura, D.; Giannini, C.; Capitelli, M.; Spinelli, P.; Schutzmann, S. Study of polycrystalline diamond deposition by continuous and pulsed discharges. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2010, 204, 1884–1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z.; Akkerman, Z.; Yang, B.X.; Smith, F.W. Optical properties and microstructure of CVD diamond films. Diam. Relat. Mater. 1997, 6, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parka, J.; Choi, I.; Jeong Lee, M.; Kima, M.H.; Lima, T.; Parka, K.H.; Janga, J.; Oha, S.M.; Cho, S.K.; Kima, J.J. Effect of fluoroethylene carbonate on electrochemical battery performance and the surface chemistry of amorphous MoO2 lithium-ion secondary battery negative electrodes. Electrochim. Acta 2014, 132, 338–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langford, J.I.; Wilson, A.J.C. Scherrer after sixty years: A survey and some new results in the determination of crystallite size. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 1978, 11, 102–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, G.K.; Smallman, R.E., III. Dislocation densities in some annealed and cold-worked metals from measurements on the X-ray debye-scherrer spectrum. Philos. Mag. A J. Theor. Exp. Appl. Phys. 1956, 1, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.M.; Egiza, M.; Murasawa, K.; Sugita, H.; Deckert-Gaudig, T.; Deckert, V.; Yoshitake, T. Effects of substrate temperature and intermediate layer on adhesion, structural and mechanical properties of coaxial arc plasma deposition grown nanodiamond composite films on Si substrates. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2021, 417, 127185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Yin, L.; Chu, P.K. Finite element analysis of residual stress and interlayer in hard coating/interlayer/soft substrate system during nanoindentation. J. Mater. Res. 2008, 23, 1358–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.-H.; Ma, C.-H.; Chen, H. Effect of Ti interlayer on the residual stress and texture development of TiN thin films. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2006, 200, 5937–5945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, F.; Wei, Q.; Yu, Z.M.; Luo, J.; Zhang, X.; Long, H.; Wu, X. Effects of temperature and Mo2C layer on stress and structural properties in CVD diamond film grown on Mo foil. J. Alloys Compd. 2013, 579, 638–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gicquel, A.; Hassouni, K.; Silva, F.; Achard, J. CVD diamond films: From growth to applications. Curr. Appl. Phys. 2001, 1, 479–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engwall, A.M.; Rao, Z.; Chason, E. Origins of residual stress in thin films: Interaction between microstructure and growth kinetics. Mater. Des. 2016, 110, 616–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huff, M. Review Paper: Residual Stresses in Deposited Thin-Film Material Layers for Micro- and Nano-Systems Manufacturing. Micromachines 2022, 13, 2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, F.; Bayerlein, K.; Rosiwal, S.M.; Göken, M.; Durst, K. Stress evolution and cracking of crystalline diamond thin films on ductile titanium substrate: Analysis by micro-Raman spectroscopy and analytical modelling. Acta Mater. 2011, 59, 5422–5433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicala, G.; Magaletti, V.; Senesi, G.S.; Carbone, G.; Altamura, D.; Giannini, C.; Bartali, R. Superior hardness and Young’s modulus of low temperature nanocrystalline diamond coatings. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2014, 144, 505–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiklund, U.; Gunnars, J.; Hogmark, S. Influence of residual stresses on fracture and delamination of thin hard coatings. Wear 1999, 232, 262–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forschelen, P.J.J.; Suiker, A.S.J.; van der Sluis, O. Effect of residual stress on the delamination response of film-substrate systems under bending. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2016, 97–98, 284–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurciullo, A.; Lucca Fabris, A.; Knoll, A. Direct Current Plasma Electron Source for Electric Propulsion Applications Using Atomic and Molecular Propellants. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 2017, 45, 2472–2480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nothwang, W.D.; Cole, M.W.; Hirsch, S.G. Grain growth and residual stress in BST thin films. Integr. Ferroelectr. 2005, 71, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Sengupta, A.; Pantuso, D.; Koslowski, M. Effect of texture and grain size on the residual stress of nanocrystalline thin films. Model. Simul. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2017, 25, 075004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

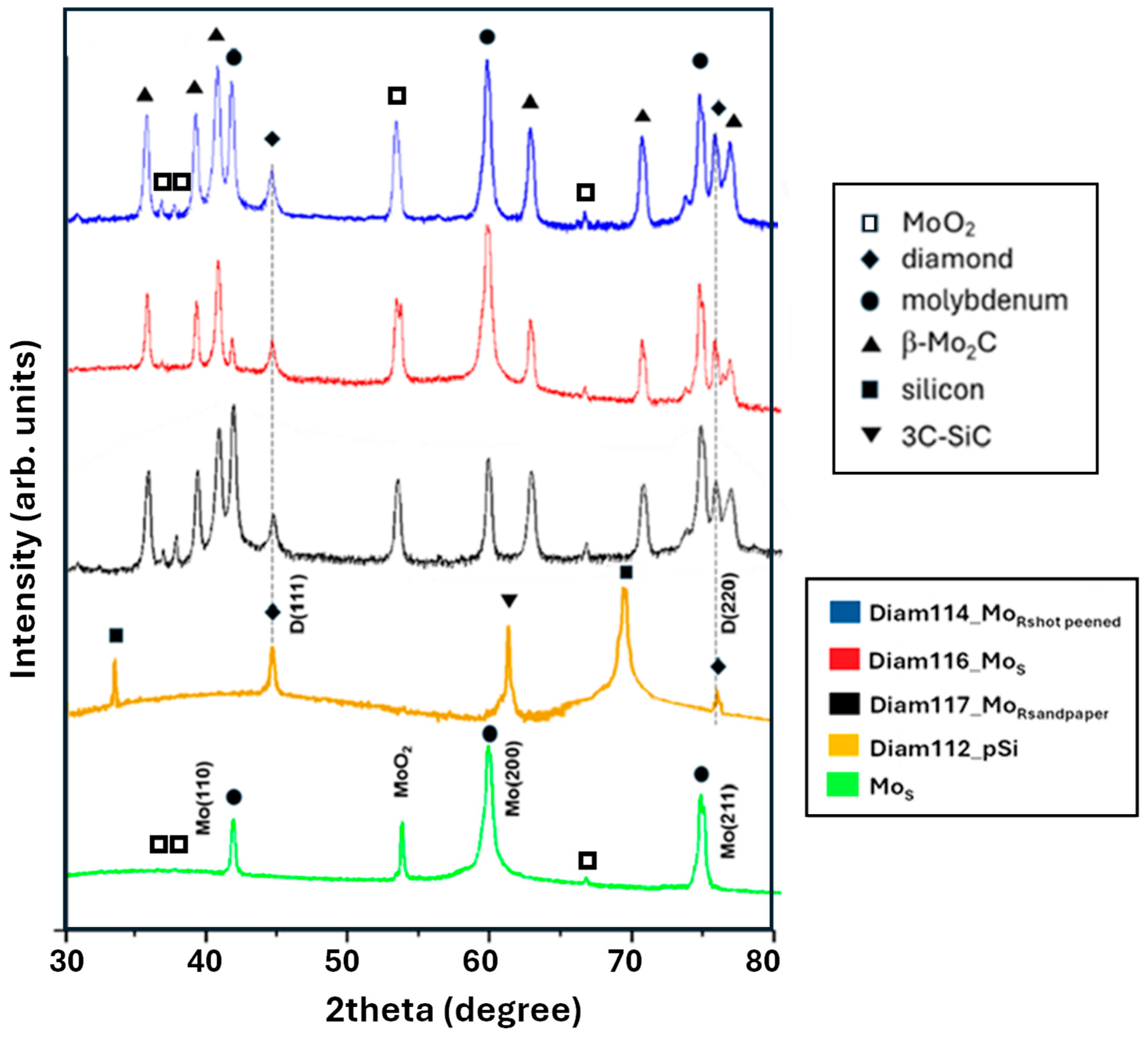

| Material | Thermal Expansion (×10−6 K−1) | Melting Point (°C) | Lattice Constant (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Copper | 16.5 | 1084 | 0.361 |

| Silicon | 2.6 | 1414 | 0.543 |

| Molybdenum | 4.8 | 2623 | 0.314 |

| Diamond | 1.0 | 4090 | 0.357 |

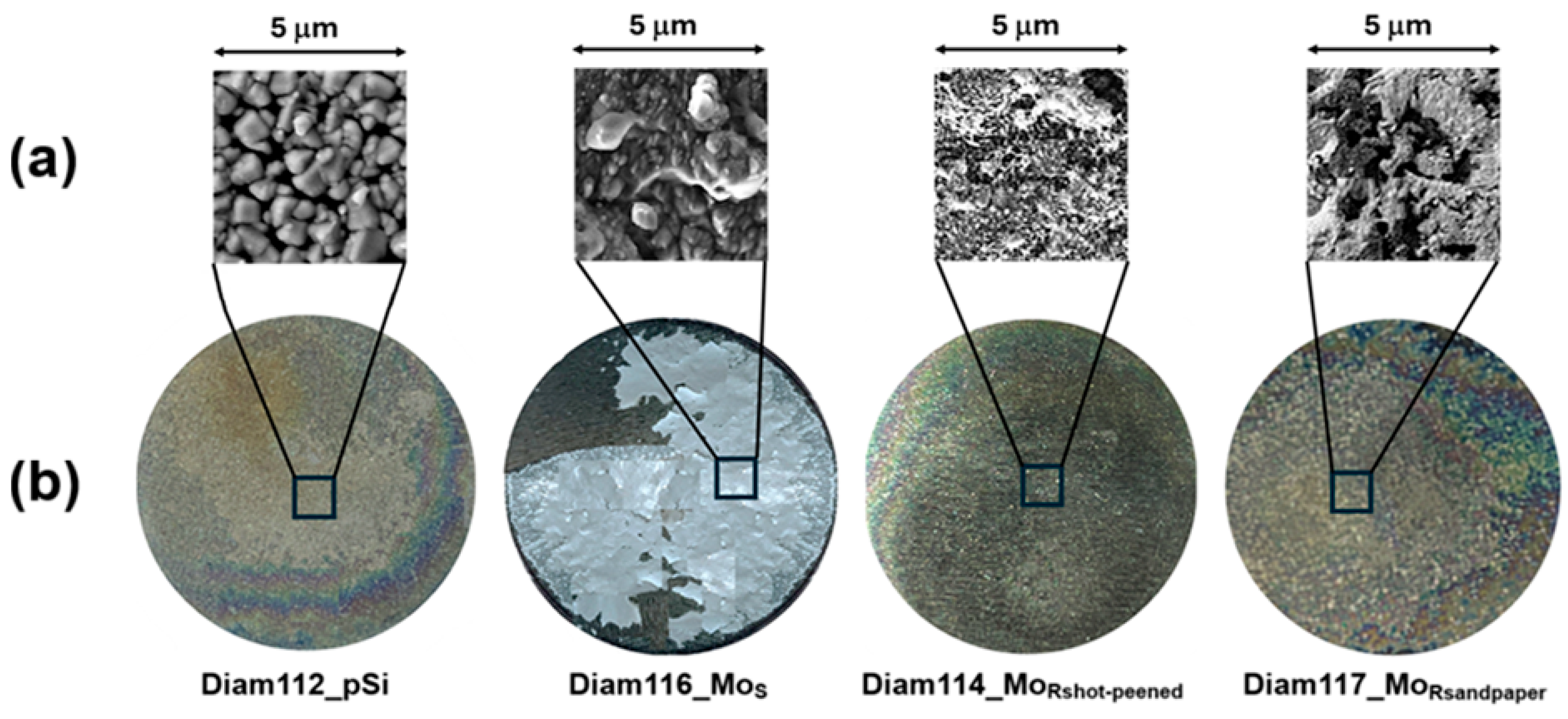

| Sample | Substrate Type | Deposition Temperature (°C) | Deposition Time (min) | Deposition Rate rD (μm/h) | Thickness (μm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diam112_pSi | p-Si | 820 | 180 | 0.43 ± 0.02 | 1.29 ± 0.05 |

| Diam116_MoS | smooth Mo | >950 | 219 | 0.33 ± 0.02 | 1.20 ± 0.03 |

| Diam117_MoRsandpaper | rough Mo 1 | 873 | 217 | 0.30 ± 0.02 | 1.10 ± 0.02 |

| Diam114_MoRshot-peened | rough Mo 2 | 818 | 420 | 0.17 ± 0.02 | 1.20 ± 0.04 |

| Sample | GS(111) (nm) | GS(220) (nm) | Substrate Roughness (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diam112_pSi | 49.9 | 44.4 | very low (<1) |

| Diam116_MoS | 36.9 | 31.2 | 70 ± 5 |

| Diam114_MoRshot-peened | 27.4 | 24.4 | 580 ± 50 |

| Diam117_MoRsandpaper | 26.5 | 26.3 | 675 ± 65 |

| Sample | a (111) Å | a (220) Å | δ111 (×1015 lines/m2) | δ220 (×1015 lines/m2) | N111 (×1016/m2) | N220 (×1016/m2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diam112_pSi | 3.54 | 3.55 | 0.40 | 0.51 | 1.04 | 1.48 |

| Diam116_MoS | 3.50 | 3.51 | 0.73 | 1.02 | 2.80 | 4.62 |

| Diam114_MoRshot-peened | 3.51 | 3.52 | 1.33 | 1.68 | 5.78 | 8.20 |

| Diam117_MoRsandpaper | 3.51 | 3.52 | 1.42 | 1.45 | 7.16 | 7.35 |

| Sample | Diamond Peak (cm−1) | FWHM (cm−1) | t-PA (cm−1) | G-Band (cm−1) | Fq = ID/IND | AR = AD/AND |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diam112_pSi | 1332.5 | 4.8 | -- | 1515 | 7.0 | 0.45 |

| Diam116_MoS | 1335.2 | 5.4 | 1485 | 1515 | 4.6 | 0.30 |

| Diam114_MoRshot-peened | 1334.4 | 8.3 | 1485 | 1545 | 1.9 | 0.18 |

| Diam117_MoRsandpaper | 1334.9 | 9.9 | 1493 | 1555 | 1.4 | 0.15 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Velardi, L.; Cicala, G.; Della Torre, A.; Francioso, L.N.; Signore, M.A. Impact of Mo Substrate Roughness on the Stability and Properties of Diamond Films for Aerospace Applications. Surfaces 2025, 8, 85. https://doi.org/10.3390/surfaces8040085

Velardi L, Cicala G, Della Torre A, Francioso LN, Signore MA. Impact of Mo Substrate Roughness on the Stability and Properties of Diamond Films for Aerospace Applications. Surfaces. 2025; 8(4):85. https://doi.org/10.3390/surfaces8040085

Chicago/Turabian StyleVelardi, Luciano, Grazia Cicala, Antonio Della Torre, Luca Nunzio Francioso, and Maria Assunta Signore. 2025. "Impact of Mo Substrate Roughness on the Stability and Properties of Diamond Films for Aerospace Applications" Surfaces 8, no. 4: 85. https://doi.org/10.3390/surfaces8040085

APA StyleVelardi, L., Cicala, G., Della Torre, A., Francioso, L. N., & Signore, M. A. (2025). Impact of Mo Substrate Roughness on the Stability and Properties of Diamond Films for Aerospace Applications. Surfaces, 8(4), 85. https://doi.org/10.3390/surfaces8040085