Surveying a Sacred Landscape: First Steps to a Holistic Documentation of Buddhist Architecture in Dolpo

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Short Historical Remarks on Dolpo

1.2. International Research on Dolpo

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Field Research

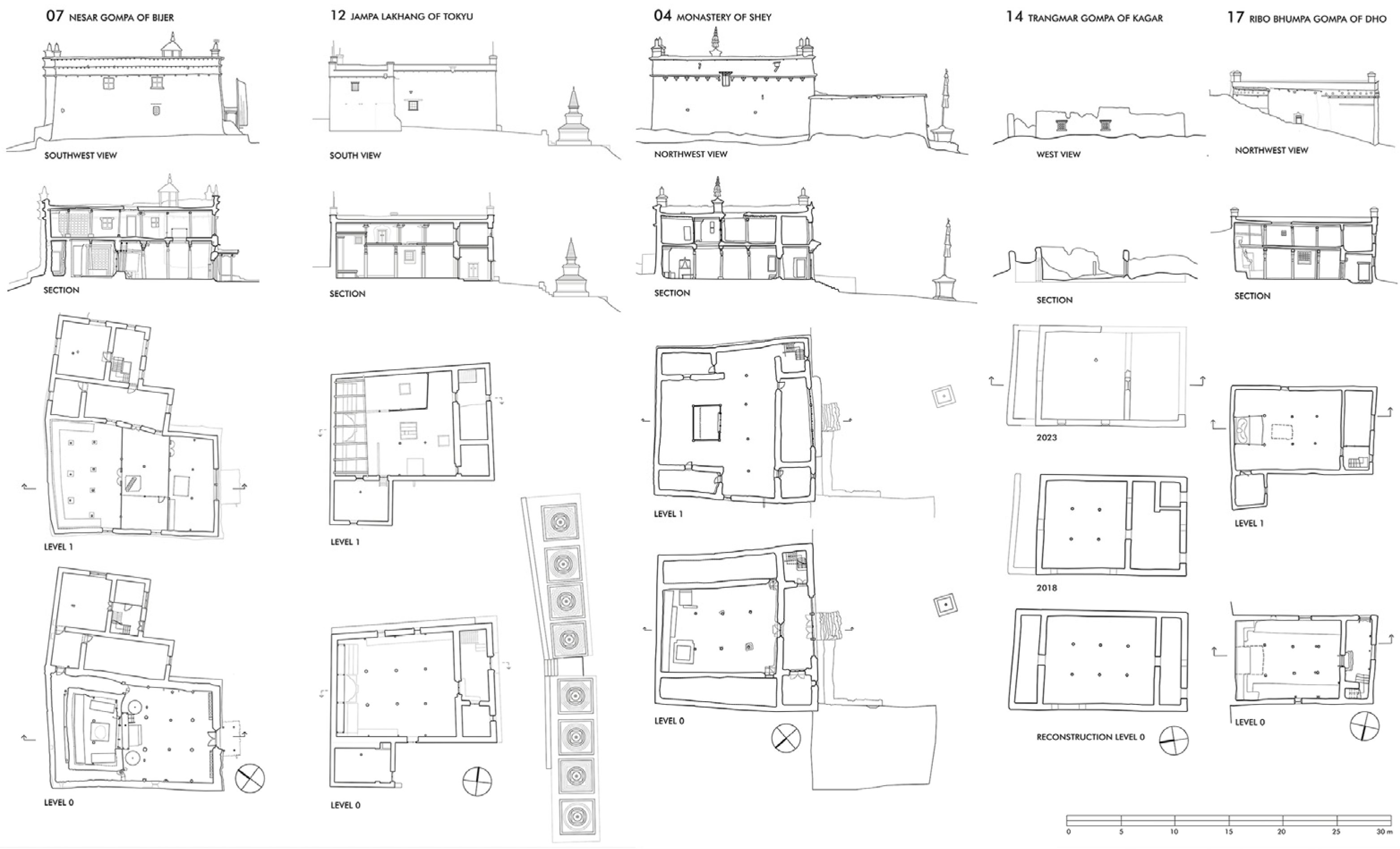

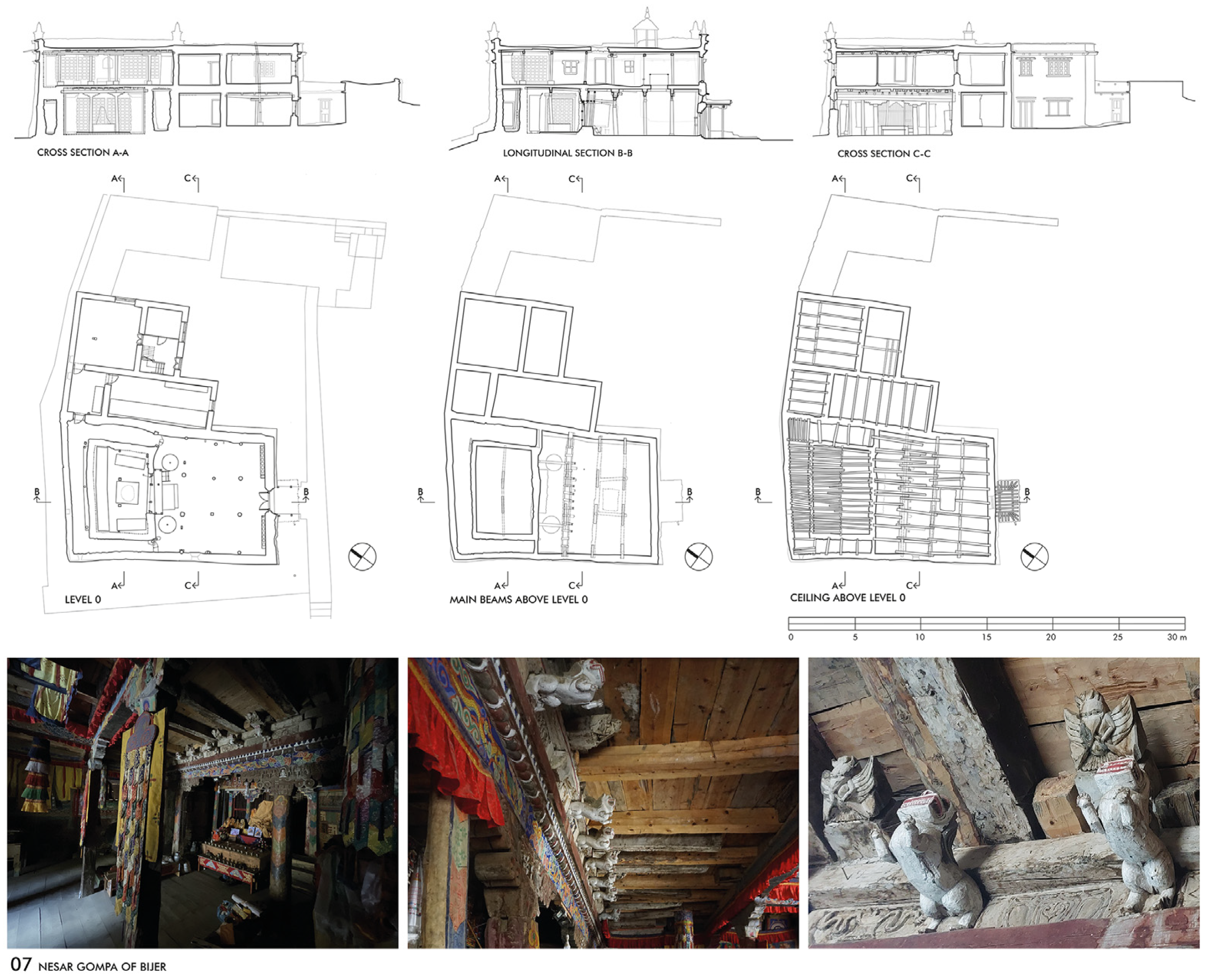

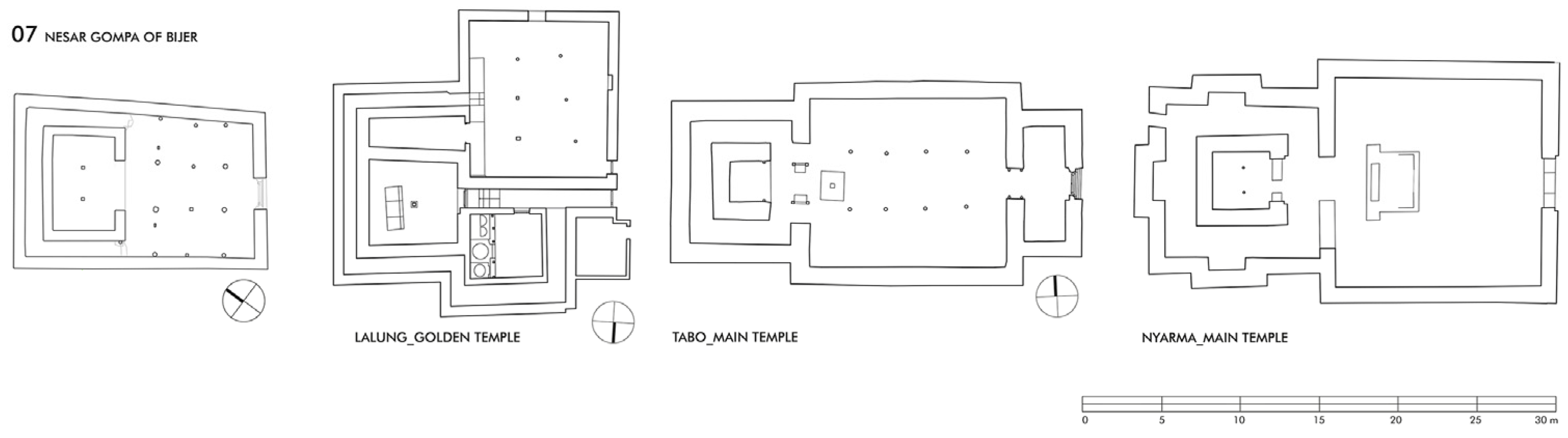

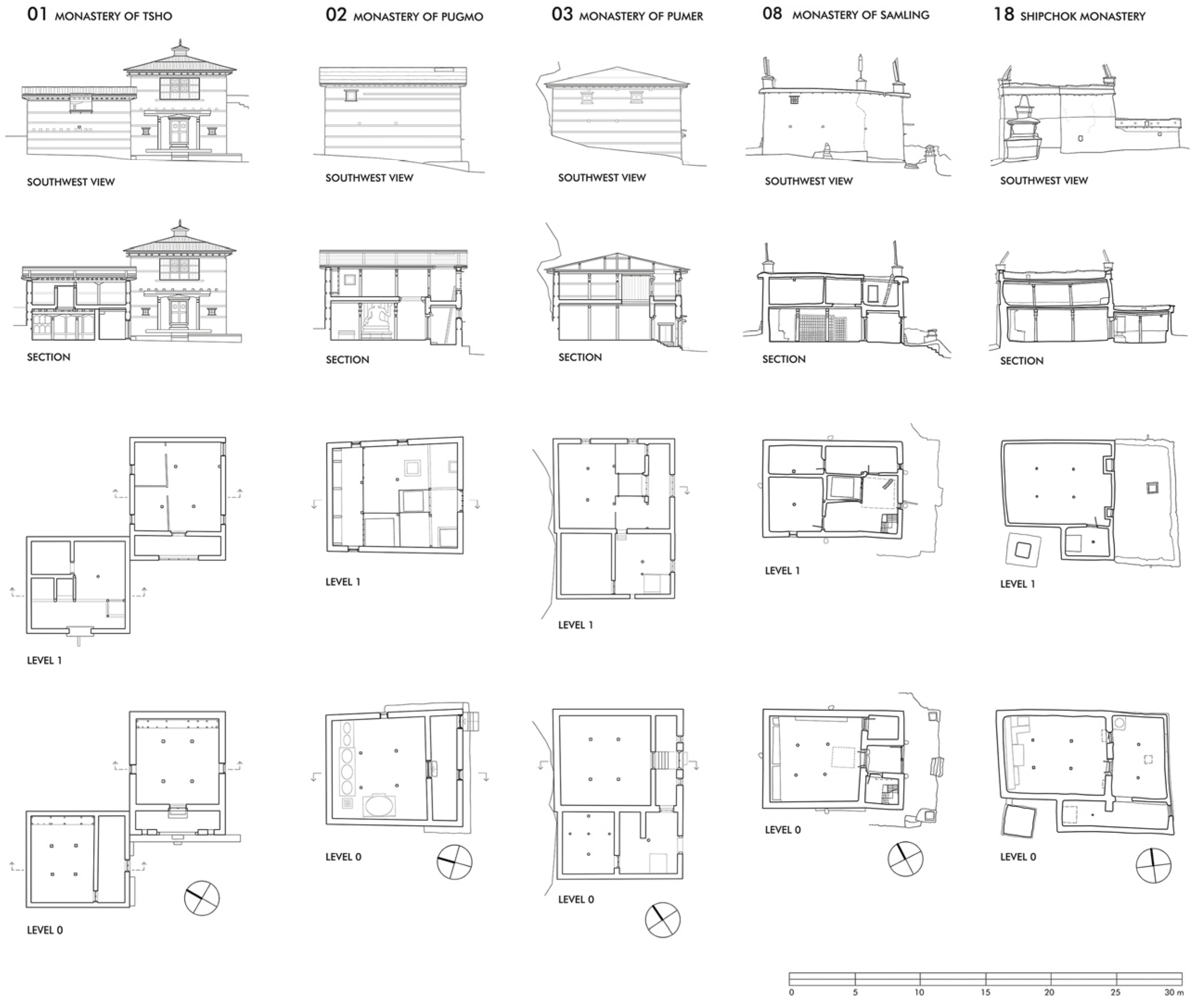

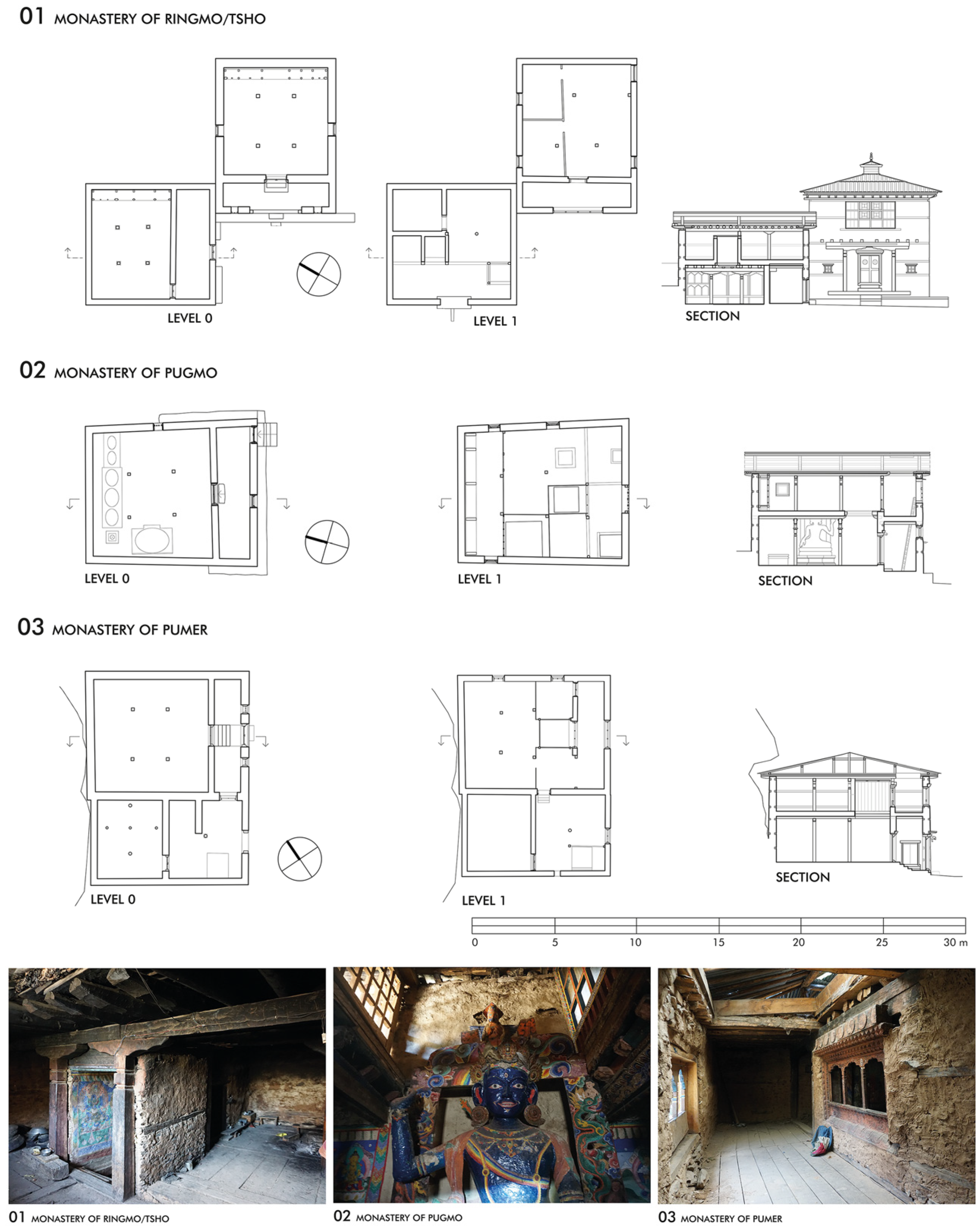

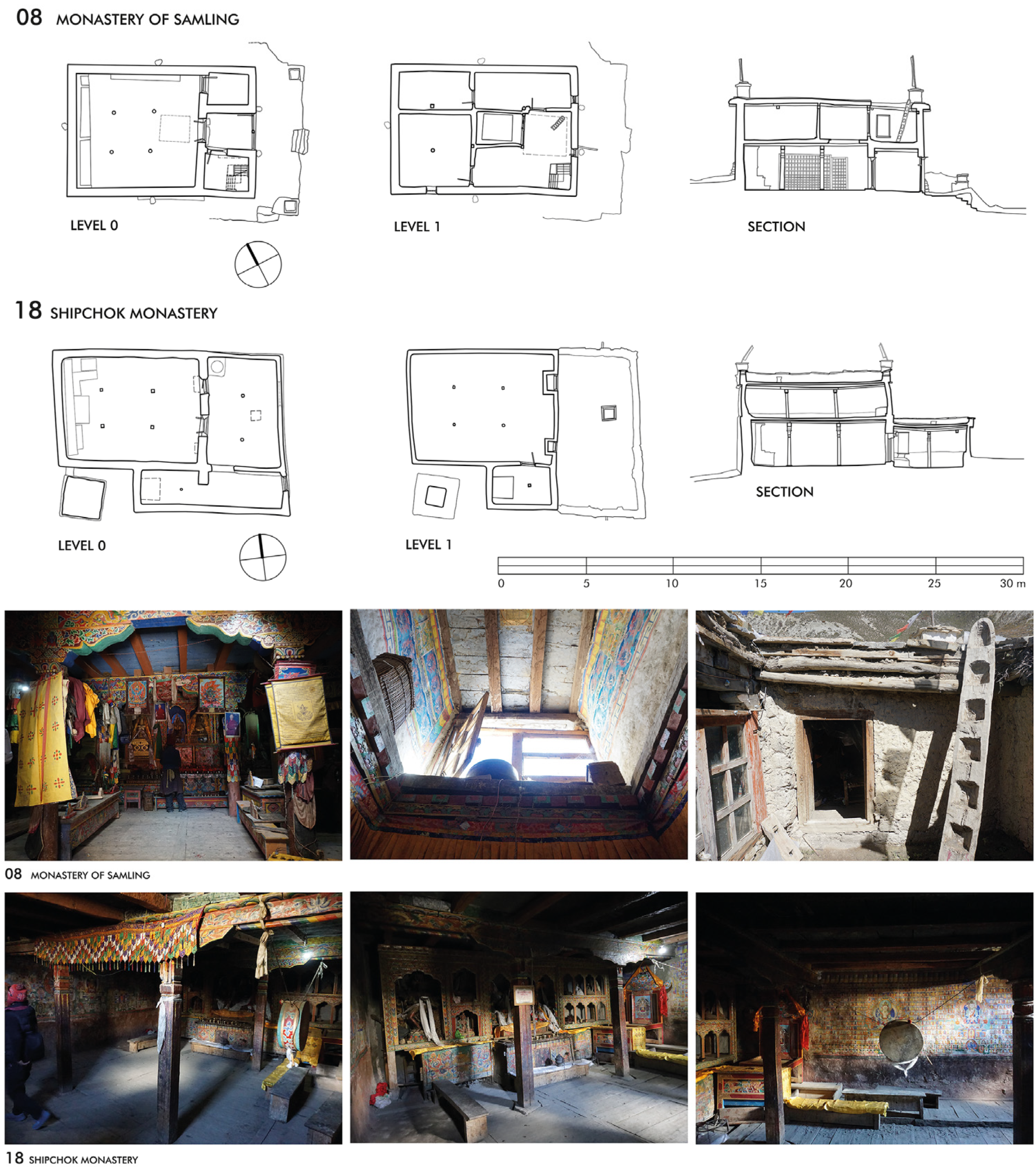

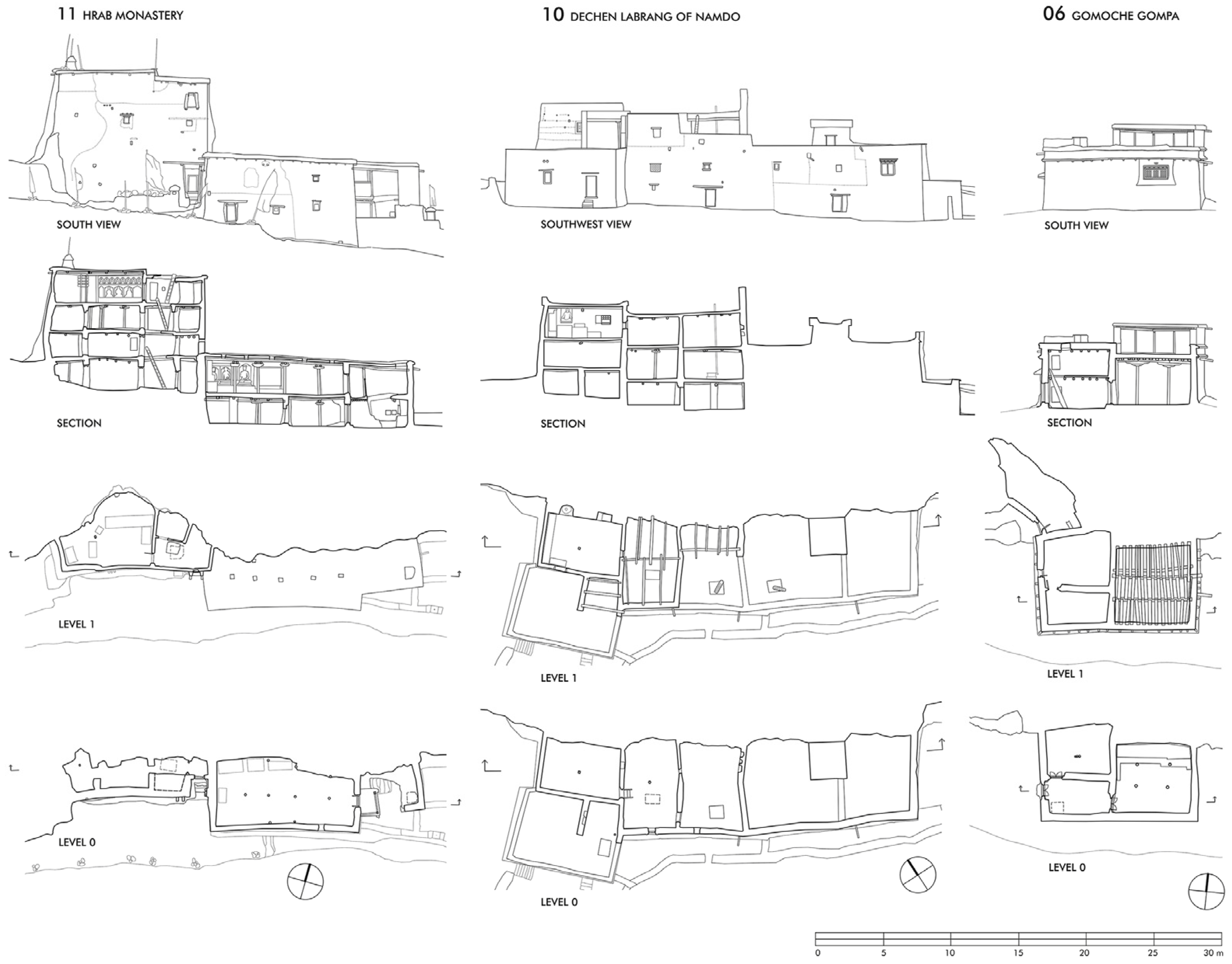

2.2. Plan Documentation and Analyses

Comparative Study

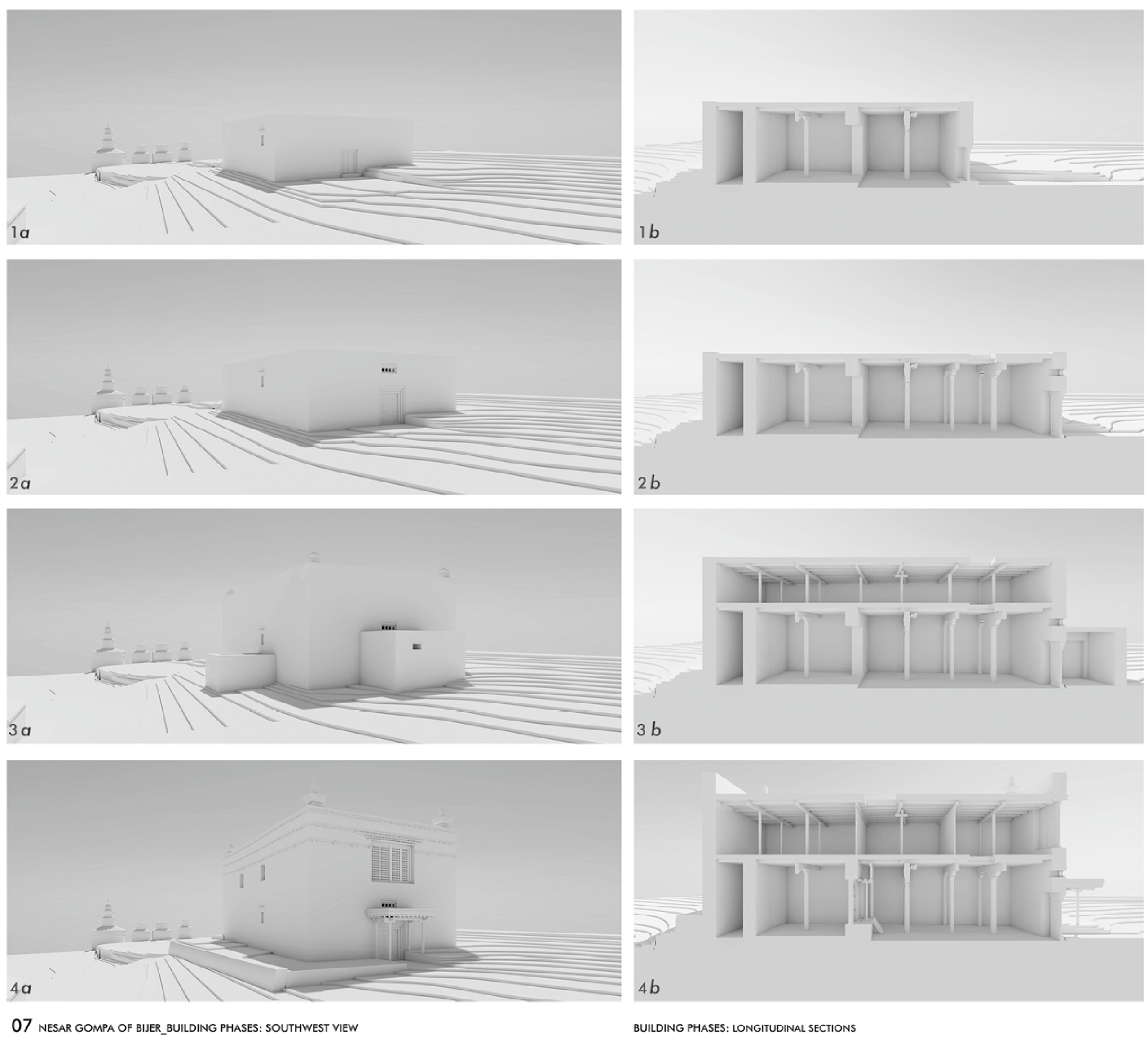

2.3. Scaled Representations and Spatial Reconstructions

3. Results

3.1. The Sacred Landscape

3.2. The Choice of the Site and the Orientation of the Structure

‘One should seek out a place for building a temple in places that have the following: a tall mountain behind and many hills in front, two rivers converging in front from the right and left, a central valley of rocks and meadows resembling heaps of grain, […]. The good characteristics called the four Earth-pillars are: a wide expanse in the east, a heap in the south, a rounded bulge in the west, and in the north a mountain like a draped curtain’ [23] (p. 29)

3.3. Building Construction and Material

3.4. Building Typology and Room Configuration

3.5. The ‘Six Pillar and Nine Beams’ Temple

3.5.1. Case Study No. 1: The Nesar Gompa in Bijer

3.5.2. Case Study No. 2: The Jampa Lakhang in Tokyu

3.5.3. Sacred Chambers

3.6. The ‘Four Pillar and Eight Beams’ Temple

3.6.1. Case Study No. 3: The Kagar Labrang

3.6.2. Special Features of the Bon Temples

3.7. Overbuilt Cave Sanctuaries and Multi-Storey Room Stuctures

3.7.1. Case Study No. 4: The Gomoche Gompa and the Tsakhang Gompa

3.7.2. Case Study No. 5: The Hrab Monastery and the Dechen Labrang of Namdo

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jest, C. Dolpo. Communautés de Langue Tibétaine du Nepal; Editions du CNRS: Paris, France, 1975; p. 38. [Google Scholar]

- Jest, C. Preface. In Hidden Treasures of the Himalayas. Tibetan Manuscripts, Paintings and Sculptures of Dolpo; Heller, A., Ed.; Serindia Publications: Chicago, IL, USA, 2009; p. 12. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, D.P. Notes on the History of Serib, and Nearby Places in the Upper Kali Gandaki Valley. Kailash 1978, 6/3, 195–228. [Google Scholar]

- Snellgrove, D.L. Himalayan Pilgrimage: A Study of Tibetan Religion by a Traveler Through Western Nepal; Bruno Cassirer: Oxford, UK, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Snellgrove, D.L. Four Lamas of Dolpo: Tibetan Biographies. Introduction and Translation; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1967; Volume 1, pp. 2–3, 7–10. [Google Scholar]

- Kind, M. The Bon Landscape of Dolpo: Pilgrimages, Monasteries, Biographies and the Emergence of Bon; Peter Lang: Berlin, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Tucci, G. Preliminary Report on Two Scientific Expeditions in Nepal; Serie Orientale Roma; Is.M.E.O.: Rome, Italy, 1956; Volume X. [Google Scholar]

- Snellgrove, D.L. The Nine Ways of Bon: Excerpts from gZi-brjid; Oxford University Press: London, UK, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Jest, C. Monuments of Northern Nepal; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation: Paris, France, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- NGMCP. Available online: https://www.aai.uni-hamburg.de/en/forschung/ngmcp/about.html (accessed on 27 August 2025).

- Heller, A. Hidden Treasures of the Himalayas: Tibetan Manuscripts, Paintings and Sculptures of Dolpo; Serindia Publications: Chicago, IL, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- TMPV. Available online: https://tmpv.univie.ac.at/about (accessed on 27 August 2025).

- Kind, M. Mendrub—A Bo¨npo Ritual for the Benefit of All Living Beings and the Empowerment of Medicine Performed in Tsho, Dolpo; WWF-Nepal Program: Kathmandu, Nepal, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Gansach, A. Social Constructions: A Comparative Study of Architectures in the High Himalaya of North West Nepal. Ph.D. Thesis, Architectural Association School of Architecture, London, UK, 30 June 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Gansach, A. Expressions of Diversity. A Comparative Study of Descriptions of Village Space in Ritual Processions in Three Villages of North West Nepal. In Sacred Landscape of the Himalaya; Proceedings of an International Conference at Heidelberg, Heidelberg, Germany, 25–27 May 1998; Gutschow, N., Michaels, A., Ramble, C., Steinkellner, E., Eds.; Austrian Academy of Science Press: Vienna, Austria, 2003; pp. 39–54. [Google Scholar]

- Gutschow, N. Chörten in Nepal. Architecture and Buddhist Votive Practice in the Himalaya; Dom Publishers: Berlin, Germany, 2021; pp. 401–426. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, P.; Woschitz, H. Anwendung von 3D Laserscanning im Himalaya–Erste Auswertungen. VGI Österr. Z. Vermess. Und Geoinf. 2023, 111, 119–127. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, P.; Woschitz, H. Laboratory Investigations of the Leica RTC360 Laser Scanner Distance Measuring Performance. Sensors 2024, 12, 3742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auer, C. Measure for Measure: Researching and Documenting Early Buddhist Architecture in Spiti. In The Spiti Valley: Recovering the Past and Exploring the Present; Proceedings of the First International Conference on Spiti, Wolfson College, Oxford, UK, 6–7 May 2016; Revue d’Études Tibétaines No. 41; Laurent, Y., Pritzker, D., Eds.; CNRS (CRCAO): Paris, France, 2017; pp. 181–201. Available online: https://d1i1jdw69xsqx0.cloudfront.net/digitalhimalaya/collections/journals/ret/pdf/ret_41.pdf (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- Mathes, K.D. Establishing the Succession of the Sakya Lamas of Näsar Gompa and Lang Gompa in Dolpo (Nepal). Wien. Z. Die Kunde Südasiens 2003, 47, 85–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathes, K.D. The Sacred Crystal Mountain in Dolpo: Beliefs and Pure Visions of Himalayan Pilgrims and Yogis. J. Nepal Res. Cent. 1999, 11, 61–90. [Google Scholar]

- Tucci, G. Geheimnis des Mandala. Theorie und Praxis; Otto Wilhelm Barth Verlag: Munich, Germany, 1972; pp. 28–29. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, D.P.; Thubten, L.G. Gateway to the Temple: Manual of Tibetan Monastic Customs, Art, Building and Celebrations; Ratna Pustak Bhandar: Kathmandu, Nepal, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Neuwirth, H.; Auer, C. (Eds.) The Ancient Monastic Complexes of Tholing, Nyarma and Tabo, Buddhist Architecture in the Western Himalayas; Verlag der Technischen Universität Graz: Graz, Austria, 2021; Volume 3, pp. 247–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuwirth, H.; Auer, C. (Eds.) The Ancient Monastic Complex of Dangkhar, Buddhist Architecture in the Western Himalayas; Verlag der Technischen Universität Graz: Graz, Austria, 2013; Volume 1, pp. 283–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramble, C. Is Cancel Culture Coming to Himalayan Studies? Remarks on a Recent Critique of the Life and Work of Mary Shepherd Slusser. Eur. Bull. Himal. Res. 2023, 61, 1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| N° | Name | GPS Coordinates | Website/Collected Material https://archresearch.tugraz.at/ (accessed on 10 August 2025) | Repository/Spatial Model (Supplementary Materials) https://repository.tugraz.at/ (accessed on 10 August 2025) |

| 01 | Monastery of Tsho/Ringmo | 29°10′30.21″ N, 82°56′39.09″ E, altitude 3640 m | https://archresearch.tugraz.at/results/ringmo/ (accessed on 10 August 2025) | |

| 02 | Monastery of Pugmo | 29°09′36.42″ N, 82°52′23.55″ E, altitude 3245 m | https://archresearch.tugraz.at/results/pugmo/ (accessed on 10 August 2025) | |

| 03 | Monastery of Pumer | 29°09′05.30″ N, 82°51′49.76″ E, altitude 3477 m | https://archresearch.tugraz.at/results/pumer/ (accessed on 10 August 2025) | |

| 04 | Shey Sumdo Monastery | 29°21′8.81″ N, 82°57′56.07″ E, altitude 4345 m | https://archresearch.tugraz.at/results/shey/ (accessed on 10 August 2025) | https://repository.tugraz.at/records/sn49f-rj787 (accessed on 10 August 2025) |

| 05 | Tsakhang Gompa | 29°22′1.38″ N, 82°57′18.42″ E, altitude 4458 m | https://archresearch.tugraz.at/results/crystal-mountain/ (accessed on 10 August 2025) | |

| 06 | Gomoche Gompa | 29°22′1.38″ N, 82°57′18.42″ E, altitude 4434 m | https://archresearch.tugraz.at/results/crystal-mountain_gomoche/ (accessed on 10 August 2025) | https://repository.tugraz.at/records/9gpxc-j0x43 (accessed on 10 August 2025) |

| 07 | Nesar Gompa of Bijer | 29°27′8.06″ N, 82°54′51.36″ E, altitude 3838 m | https://archresearch.tugraz.at/results/bijer/ (accessed on 10 August 2025) | https://repository.tugraz.at/records/jknbg-tzq09 (accessed on 10 August 2025) |

| 08 | Samling Monastery | 29°25′52.59″ N, 82°54′27.44″ E, altitude 4166 m | https://archresearch.tugraz.at/results/samling/ (accessed on 10 August 2025) | https://repository.tugraz.at/records/nf9kd-06793 (accessed on 10 August 2025) |

| 09 | Yangtse Monastery | 29°29′45.00″ N, 83°5′54.77″ E, altitude 3900 m | https://archresearch.tugraz.at/results/yangtser/ (accessed on 10 August 2025) | |

| 10 | Dechen Labrang of Namdo | 29°23′29.74″ N, 83°6′0.36″ E, altitude 3950 m | https://archresearch.tugraz.at/results/namdo/ (accessed on 10 August 2025) | https://repository.tugraz.at/records/220bk-bn876 (accessed on 10 August 2025) |

| 11 | Hrab Monastery | 29°22′30.61″ N, 83°7′8.28″ E, altitude 4283 m | https://archresearch.tugraz.at/results/tsa/ (accessed on 10 August 2025) | https://repository.tugraz.at/records/hsfqx-qen16 (accessed on 10 August 2025) |

| 12 | Jampa Lakhang of Tokyu | 29°9′52.38″ N, 83°9′31.08″ E, altitude 4214 m | https://archresearch.tugraz.at/results/tokyu/ (accessed on 10 August 2025) | |

| 13 | Village Gompa of Kagar | 29°9′0.86″ N, 83°10′16.83″ E, altitude 4170 m | https://archresearch.tugraz.at/results/kagar-01/ (accessed on 10 August 2025) | https://repository.tugraz.at/records/eebzm-tyc06 (accessed on 10 August 2025) |

| 14 | Trangmar Gompa of Kagar | 29°9′0.86″ N, 83°10′16.83″ E, altitude 4170 m | https://archresearch.tugraz.at/results/kagar/ (accessed on 10 August 2025) | https://repository.tugraz.at/records/eebzm-tyc06 (accessed on 10 August 2025) |

| 15 | Zur Gompa above Kagar | 29°9′7.43″ N, 83°10′19.39″ E, altitude 4220 m | https://archresearch.tugraz.at/results/kagar-03/ (accessed on 10 August 2025) | https://repository.tugraz.at/records/eebzm-tyc06 (accessed on 10 August 2025) |

| 16 | Mekyem Gompa | 29°8′49.04″ N, 83°10′55.77″ E, altitude 4288 m | https://archresearch.tugraz.at/results/kagar-mekyem/ (accessed on 10 August 2025) | https://repository.tugraz.at/records/xvt6k-hr994 (accessed on 10 August 2025) |

| 17 | The Ribo Bhumpa Gompa of Dho Tarap | 29°7′56.70″ N, 83°11′18.84″ E, altitude 4069 m | https://archresearch.tugraz.at/results/dho-tarap/ (accessed on 10 August 2025) | https://repository.tugraz.at/records/r845a-2n560 (accessed on 10 August 2025) |

| 18 | Shipchok Monastery of Dho Ro | 29°7′41.20″ N, 83°12′5.81″ E, altitude 4146 m | https://archresearch.tugraz.at/results/dho-ro/ (accessed on 10 August 2025) | https://repository.tugraz.at/records/2422r-ske71 (accessed on 10 August 2025) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Auer, C.E. Surveying a Sacred Landscape: First Steps to a Holistic Documentation of Buddhist Architecture in Dolpo. Heritage 2025, 8, 385. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8090385

Auer CE. Surveying a Sacred Landscape: First Steps to a Holistic Documentation of Buddhist Architecture in Dolpo. Heritage. 2025; 8(9):385. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8090385

Chicago/Turabian StyleAuer, Carmen Elisabeth. 2025. "Surveying a Sacred Landscape: First Steps to a Holistic Documentation of Buddhist Architecture in Dolpo" Heritage 8, no. 9: 385. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8090385

APA StyleAuer, C. E. (2025). Surveying a Sacred Landscape: First Steps to a Holistic Documentation of Buddhist Architecture in Dolpo. Heritage, 8(9), 385. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8090385