1. Introduction

We seem to be living through an era where current events, updated in real-time, threaten to overwhelm our sensibilities. Between geo-political uncertainties and our fluctuating environment, one might be forgiven for thinking of socio-cultural studies or heritage management programs as indulgences—a luxury of post-colonial exotica and nostalgic antiquarianism. Perceptions of the social sciences, and heritage management in particular, tend to be narrowly framed in terms of economic utility, tourism, or their aesthetic appeal. These perspectives, however, overlook the broader aims and fundamental role of the social sciences.

It has been observed many times by philosophers, historians, and others (e.g., from Cicero to Santayana, and Edmund Burke to Winston Churchill) that history seems to repeat itself. More importantly, failure to learn from history ensures its mistakes are repeated. Even so, the fields of expertise wielding that essential information are often conspicuously missing from public discourse or policy discussions. Fields such as archaeology and anthropology seem not to be recognized for their real objective—i.e., analyzing the mechanisms of human behavior that shape societies, how they function, and why they thrived or failed as they did.

As experts in the social sciences, we need to highlight this point far better than we have. Cultural studies and heritage management hold invaluable information for contemporary society. After all, our collective histories are filled with causes and effects, and successes or failures, of events not unlike those we are experiencing now. Cultural heritage professionals maintain, refine, and curate this critical body of knowledge. The need to understand these historical trajectories is not merely an academic exercise. The adaptive behavioral strategies of the past are exceedingly pertinent to our current challenges.

There is, however, a persistent and insurmountable obstacle to applying that knowledge. We do not have a precise definition of what is, arguably, the foundational concept in social science. We do not have a coherent definition for what culture is or what it does.

Our field is frequently criticized for being excessively open-ended, subjective, and lacking in empirical rigor. This is, in no small part, why the terminology of the social sciences is often co-opted to express something other than its intended meaning. If we are only describing broad concepts with vague terminology, what is there to prevent “definition creep”?

What stops the public from accepting pseudo-scientific explanations of the past if we, the experts, collectively fail to define our own object of study?

Seeking a secure definition for the term

culture is not a new issue. Most anthropologists will be familiar with the Kroeber and Kluckhohn [

1] enumeration of the nearly 160 definitions in use at their time, and the situation has not improved. Although we all know it when we see it, and can broadly identify culture, we still cannot cogently define it. One-to-one comparisons between the behavior and cognitive development of humans with that of the primate and animal world has provided some insight but has been far from explanatory.

There are many social organisms, but only humans appear to have evolved this specific and peculiar

form of sociality that we recognize as culture. More than a century of study and theorizing have advanced our understanding, but a systematic definition of culture has remained elusive [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Below we will show that both individual and collective human behavior is grounded in the transformation and exchange of information that shapes beliefs, actions, and choices. Therefore,

culture is understood not as a fixed set of attributes but as a dynamic information process that enables learning, adaptation, and enculturation. This structuring structure

1 provides a unifying framework to reconcile the many definitions for culture across the social sciences and explains the processes that generate cultural practices and expressions.

2. Motivation for Rethinking Culture

Our research began by inverting some of the age-old questions and assumptions regarding social behavior and organization [

6]. We started with what seemed a simple and unlikely, though ultimately critical, premise. The systemic commonality for

all social phenomena is the continuous acquisition, exchange, updating, and retention of information. From the individual to the group and back, the fabric of social interactions is predicated on our need to seek, exchange, and maintain collective bodies of information. We found that this ability to capture and process information forms the basis for the social and behavioral phenomena attributed to culture.

When we refer to

information, in this and the following discussions, we are not using it in the colloquial or even epistemological sense. Rather, we are primarily referring to its

technical usage—i.e., reducing ambiguity or

surprisal2. In other words, the meaningful content of that information is not specifically germane to the discussion but only to the degree that it reduces unpredictability. Information in this regard is the amount of data (e.g., observations, events, or experiences) required to transform expectations into

instrumental information (in the epistemological sense) based on its population-specific collective utility and reinforcement through individual experiences.

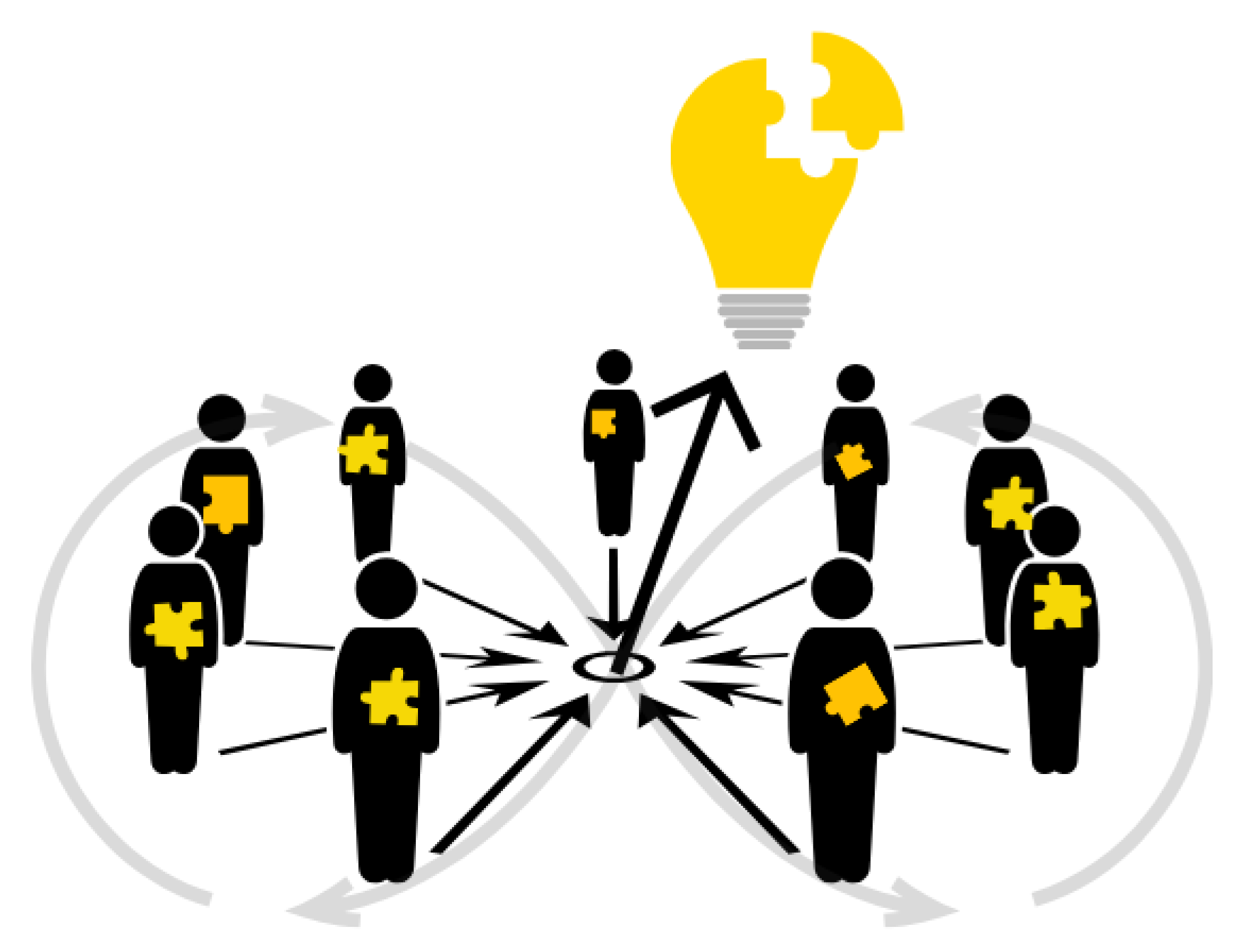

Transforming experience into information through comparison, exchange, filtering, and updating generates knowledge appropriate to the individual and their communities (

Figure 1). As such, the fundamental need to filter and curate the instrumental information required for survival provides a better foundation for explaining social behavior. The knowledge produced becomes the

how,

what, and

why that each group uses to address and successfully fulfill their fundamental or primal needs. The characteristic elements of culture, which we identify as social norms and institutions, reflect these evolutionary behavioral adaptations to continuously discover and maintain this body of knowledge and information, independently of any individual. Furthermore, these social interactions and structures allow for information to be constantly refreshed, updated, and made comprehensible.

Fundamentally, our behavioral adaptations must abide by the same organic and biological “rules” as everything else. We must maintain an energetic equilibrium within an ever-changing environment, and uncertainty is energetically costly. Our social complexity often obscures this fundamental reality, but that complexity is a function of the breadth of information we can process. That information cannot, however, solely be a product of individual maintenance. Cultural sociality is necessarily a collective endeavor.

To clarify, our approach is that the infrastructure that supports the entire system of human behavior—individually and collectively—is built on the transformation of information in one form or another. This is the source of our beliefs, our actions, and our choices, ranging from how we address the physical and social environments around us to what we learn from them. Furthermore, it is the way we share that information, what we know, and what we do not know. Without it, there is no learning, no enculturation, and no adaptation. We are our information and it is ultimately the structuring structure of all that we know of ourselves as human.

The basic elements of human sociality, specifically the role of social norms and institutions, form the foundations of a process of establishing socially salient information. Through recursive interactions between individual and community, that information coalesces towards a mutually supporting knowledge base for maintaining energetic

homeostasis3 among the population. We extend that model here, expanding on the fundamentals of that system to describe an information-centered model for the concept of culture. We believe that cultural sociality evolved as a specific suite of cognitive and behavioral mechanisms to identify, test, and curate information rather than as byproducts of human behavioral patterns.

In this way, culture acts as a social infrastructure supporting an adaptive knowledge network for a population within a given environment. It entails continuous and dynamic behavioral adaptation, both individually and collectively, to accommodate highly diverse and variable environments. Central to this process is the dual optimization of information—individuals synthesize personal experience with socially shared information, and communities validate and organize these inputs to enhance both individual and group adaptability.

Reconsidering culture as part of a process of information offers a way to synthesize the enormous body of findings that have led to the numerous definitions of culture considered by the social sciences. We are not proposing replacement with just another definition, but identifying the infrastructure responsible for the complex and entangled system that has emerged. In other words, this model both reconciles and explains the underlying process that produces the phenomena described by prior definitions of culture. Information explains the origin of the skills and practices that emerge while allowing for unique cultural expressions and novel adaptations through time. In short, this allows us to align our collective findings as social scientists into a greater systemic study towards understanding human behavior as a science.

We want to shift the focus from trying to describe the characteristics and attributes of culture to exploring what culture

is and what it

does. If effectively

everything that humans do is regarded as culture, then the term itself means nothing. As Wallen and Romulo [

8] very aptly stated with respect to the similarly abstract definitions of social norms, “… an explicit definition is crucial to the discussion of its place and usefulness in solving complex social-environmental issues.”

The days of the hypernym, catch-all definitions for core concepts in the social and behavioral sciences are past. To inform the present social and environmental challenges, we need a clear empirical identification of the underlying social structures. We can no longer afford rhetorical ambiguity at the expense of clear communication with the public. Our own uncertainty has become costly.

3. Understanding Culture

The word

culture, as used by anthropologists and other social sciences since at least the 20th century, has had a numerous connotations and a somewhat tendentious history

4. Traditionally, theories of culture prioritized collective aspects of social behavior—i.e., a preexisting social order

external to the individual (e.g., a “social fact” or cognitive pattern [

9,

10]). Culture was seen to act as an “environment” of symbols and meanings [

11,

12] through which individuals navigate by a suite (or “bricolage” [

10]) of learned strategies or practices [

5,

13]. The individual was viewed as having little effect, as they are embedded within culture rather than active participants in or producers of it.

Culture, when viewed as such, is limited to promoting stability and continuity

over change. It is the context in which the individual is entrenched. Culture constrains or determines behavior but does not provide an obvious pathway for change that is not

also external. Change would have to be imposed on the population through diffusion, invasion, or catastrophe [

14,

15,

16,

17]. Collectivist explanations of culture have always struggled to explain change. If there is anything humans do continuously, though, it is change and adapt.

Most of those definitions of

culture relied on collective attributes such as a stable constellation of beliefs, traditions, and institutions

5. While these may broadly describe a group’s practices at a given time in their history, they do not explain what it means for a group to be identified

as a particular culture through time. Neither does it provide any means to describe or explain any diversity of cultural practices within and between cultural relatives and neighbors.

So, how do we define a culture when its form changes, its practices change, and its people change? How can we adequately describe the culture of the United States of America in the 18th or 19th centuries, and yet still speak of it as the same population in the 21st century? We all know intuitively what we are identifying, but describing the specifics has remained elusive. Culture is the ultimate “Ship of Theseus,” continuously replaced yet perpetually the same.

Social scientists have assembled numerous observations regarding what works, what does not, and obvious gaps where our definitions fail (e.g., [

1,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27]). Many definitions, if not all, have identified at least some necessary aspects or attributes of culture that must be accounted for, but none so far have provided

sufficient explanatory mechanisms. None have been able to satisfactorily tie the respective parts together.

4. Introducing Our Model: Information and Society

Our model

6 proposes that social norms operate as adaptive social and behavioral mechanisms that help identify, retain, and apply essential information for managing the balance between risk-avoidance and innovation in dynamic environments. Rather than fixed rules, norms function as evaluative tools. They are prior beliefs that guide the interpretation of current information in response to changing conditions. By categorizing experiences in relation to shared expectations, communities can define the informational resources available to meet situational demands.

“All the experiences, observations, and outcomes from our physical and social environments are (at some level) assessed and translated into our individual pool of information. This information is the resource from which we accumulate knowledge, form opinions, establish beliefs, and make decisions. The unifying thread is that information from those events is being acquired, digested, evaluated, distilled, and utilized”.

Individuals continuously gather information through their everyday experiences and interactions with the environment [

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33]. Much of our day is spent with familiar events, peoples, and situations. Both routine patterns and subtle novelties offer valuable confirmation, validation, and/or adjustments.

The way this information is interpreted and remembered depends on each person’s unique cognitive abilities, interests, and memory, tempered by contextual factors like risk tolerance, situational dynamics, and intentions. Each individual’s experience is uniquely their own, yet is also shaped by a blend of their encounters and the influence of their social connections (e.g., their families, communities, and groups). Through these factors, they interpret and engage with the world (

Figure 2).

We deepen our understanding by drawing on the shared knowledge within our social networks and communities, especially when we lack direct experience. In those cases, we depend on others’ stories, strategies, and outcomes to inform our thinking, and fill the gaps in our own knowledge and experiential pool. Shared experiences gradually merge with our personal knowledge, shaping the beliefs and perspectives that influence how we think and act.

Within communities, knowledge is transmitted through numerous methods such as conversations, storytelling, teaching, and especially through nonverbal cues. Every social interaction innately entails some form of explicit or implicit knowledge exchange. As Fricker [

34] (p. 106) observes, “Telling is a social institution for the spreading of knowledge, enabling it to be possessed at second-hand.” These shared strategies, methods, and practices collectively evolve over time based on experiences of success and failure. Thousands of inputs and exchanges facilitate constant filtering and adjustment, which perpetuates the natural engagement of group members.

Ongoing social exchanges and interactions function as processes through which shared knowledge is continually refined. Within this dynamic, certain forms of highly distilled knowledge emerge—i.e., those critical to the survival and adaptability of the group—that must be adopted, preserved, and disseminated [

31,

35,

36]. Norms and normative institutions emerge as key mechanisms for maintaining this experiential knowledge, facilitating its retention and distribution across individuals and generations. Rather than serving primarily to promote group cohesion, they play a more fundamental role in curating and perpetuating collective knowledge, thereby standardizing effective behaviors and practices that enhance the group’s capacity to respond to their environment.

This indicates that social cohesion and coordinated behavior are not the primary goals, but the byproducts of a deeper process. They are specifically the accumulation and curation of mutual experiential knowledge. Traditional explanations often reverse this causality, treating norms as tools to enforce cohesion rather than as outcomes of shared information [

29,

37,

38,

39]. If norms are understood as repositories of mutual knowledge, then the purpose of sociality itself becomes clearer. It is not to unify the group in abstract terms, but to support the development, refinement, and transmission of that knowledge over time.

We all naturally engage with this system without considering the sheer amount of knowledge behind our simplest actions. We each address our needs in manners that conform to our populations’ expectations and yet never dwell on our actions. We all know the rules, we all learn the parameters, and we all transmit information and yet none of us know who made up the rules or when, how, or why. The system is natural, organic, and not necessarily under our control, in the same way that we breathe, see, taste, and feel. Social just is.

4.1. Social Norms

Social norms are best understood as fundamental mechanisms that support both social cognition and the emergence of sociality [

6,

28]. Rather than social norms being inherited rules or fixed strategies, they arise as central tendencies derived from the distribution of perceived beliefs and shared information. In this view, the formation of norms is a cognitive process through which social information is extracted from collective experience. While the norms produced through this process may facilitate coordination within groups, their core utility lies in offering a reference point that individuals use to orient and reconcile their own beliefs and experiences as a form of social cross-validation.

The emergence of a social norm reflects the discovery of information within a larger, dynamic information-processing infrastructure. Norms do not merely coordinate behavior, they stabilize social expectations while remaining sensitive to environmental or contextual novelty. By reducing the cognitive burden of constant decision-making and maximizing mutual intelligibility, norms optimize both individual and collective adaptation. They serve as “low-surprisal” heuristics that allow members of a group to anticipate each other’s actions without the need for explicit negotiation or enforcement [

28,

37,

40,

41].

Accordingly, the primary function of norms is to provide a framework for organizing, stabilizing, and preserving shared informational

nodes within a group. When norms are understood as emergent expressions of mutual information and belief, traditional distinctions among types of normative phenomena such as conventions [

42], descriptive norms [

43], or social norms [

44] lose their conceptual relevance. These categories, we argue, are not distinct types of normative structures but rather differentiated outcomes of a single, underlying cognitive process that normalizes shared information. Thus, what has often been treated as the phenomenon of

normativity should instead be seen as the social and cognitive performance of maintaining coherence across distributed individual experiences.

4.2. Normativity and Convergence

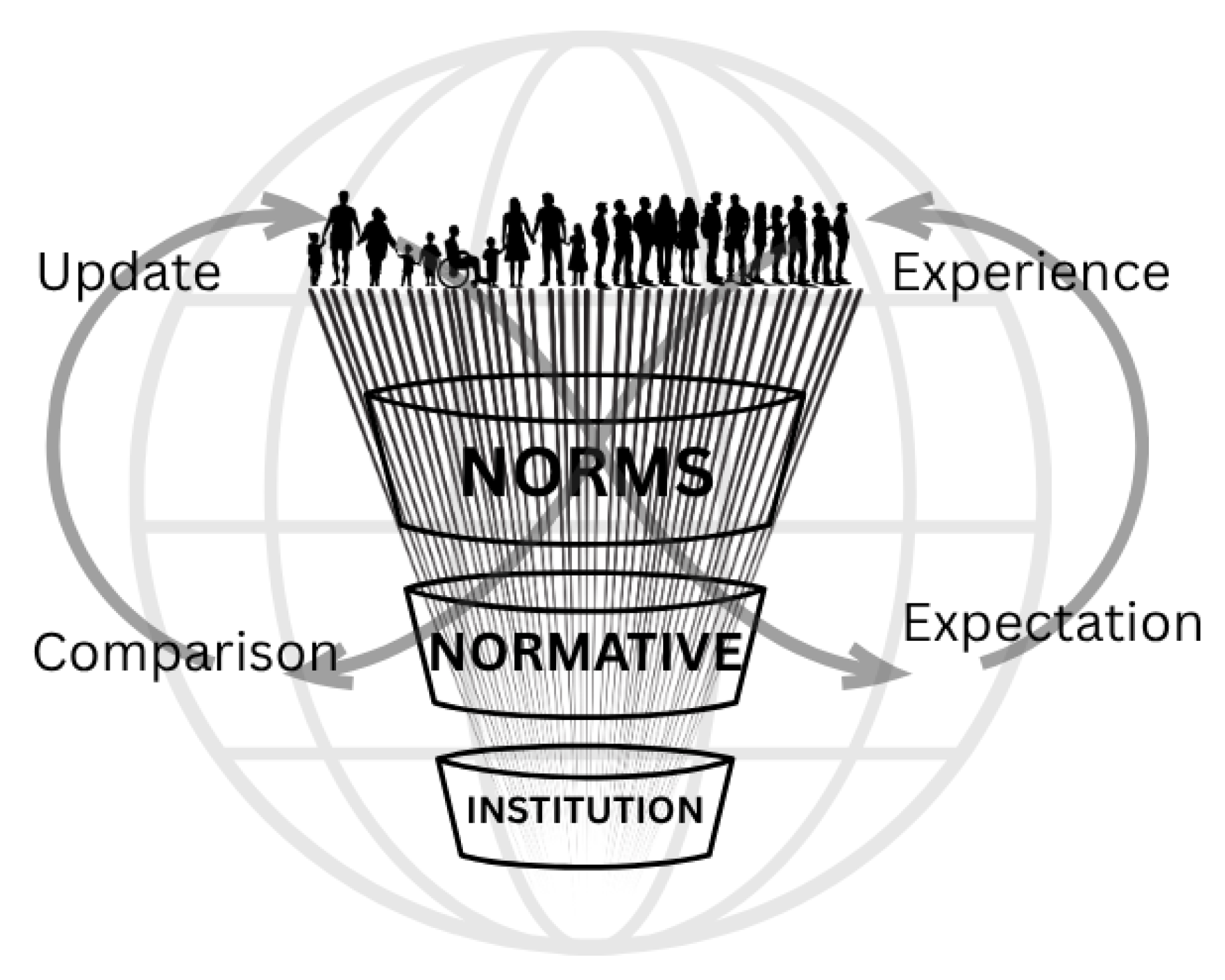

Normativity, as a social phenomenon, emerges from processes of social learning and the selective retention of effective information. It links individual and collective cognition through continual evaluation, adaptation, and transmission. Rather than being imposed, norms are adopted because they demonstrate practical utility. They serve as informational strategies that lead to effective and efficient action. For information to attain normative salience, it must prove broadly applicable and relevant to the community, thereby becoming “normal.”

Normativity functions by facilitating the widespread retention and dissemination of successful information, enabling convergence around shared practices that have demonstrated instrumental value. This convergence reduces uncertainty and lowers the cognitive burden of repeatedly reassessing known and operationalized strategies, ultimately reinforcing the pragmatic value of collectively validated knowledge [

28].

If social norms are neither strict rules nor deliberate strategies, then the expectations and beliefs that support them cannot be understood purely in terms of enforcement or regulation. Instead, normativity reflects a collective convergence of information shaped by the social norms within a community. In other words, it is an expression of how individuals and groups adaptively filter social experience for informational efficiency.

This convergence results from the ongoing, recursive interactions between individual experimentation and collective refinement. Natural social diversity across age, gender, education, experience, aptitude, and other such individual attributes ensures that a wide range of strategies and outcomes are tested. Through repeated social exchange, communities identify and retain the practices that are most effective and broadly applicable. Over time, these accumulated comparisons distill into stable informational structures underpinning shared expectations and behaviors.

Norms serve as a real-time, low-surprise filtering mechanism that aligns individual thought with collective expectations. Norms further act as an initial testing ground for individual experience (does it work, is it efficient, can I apply it, etc.). This helps explain the fast-changing nature of trends as variations emerge for initial evaluation with little energetic cost. One can try something out without needing to commit to it. It is, after all, a trend and not a rule—at least not yet. Normative convergence (

Figure 3) enables communities to collectively define domains of experience, expectations, and knowledge that shape both individual behavior and shared social equilibrium.

Rather than merely enforcing behavior, normativity fosters coherence by reflecting and operationalizing the lived experiences and effective strategies that have been sustained and replicated over time. This process creates a foundational structure of predictability that guides daily social interactions, synchronizes group expectations, and both defines community identity and shapes individual affiliation within it.

This adaptive regulation mirrors the biological process of

allostasis, or “stability through change” [

45,

46], where systems maintain optimal function through efficient responses to environmental pressures. An optimal state, in this sense, reflects a strategy of minimal effort and maximum efficacy in mitigating stressors (

Figure 4). The related concept of allostatic load (see [

46,

47,

48]) highlights the cumulative energetic and systemic costs of these adaptive responses, including the long-term strain of maintaining stability under repeated or chronic stress (e.g., allostatic accommodations [

49]).

“Normative expectations guide the coordination of individual and collective behavior towards solutions that promote an optimal allostatic state for the community. While social norms reflect the dynamic search for optimal states, normative convergence reflects the retention of provisionally optimal states for community allostasis. Normative expectations remain stabilizing points of social coordination as long as the environmental conditions and constraints of the information landscape are maintained.”

Normativity arises from cumulative social learning, reflecting the gradual convergence of a group’s shared information toward a stable, adaptive state of allostasis. Once this state is achieved, normative expectations help communities identify, validate, and preserve behavioral strategies that reduce uncertainty and promote consistency across different situations. Rather than serving as a tool of authority, normativity operates as a distributed mechanism for organizing socially relevant and meaningful information prioritizing accessibility, intelligibility, and sustainability.

4.3. From Convergence to Curation

The core function of the interaction between individual and collective information is to discern the information that merits preservation. Curation [

6] involves the selective retention, stabilization, and transmission of information over time and across social groups. Individuals are significantly more inclined to adopt strategies (i.e., trends) they have observed to be effective for others rather than to follow abstract, prescriptive guidelines.

The replication of successful behaviors not only determines what to do and how to do it [

32,

50,

51,

52], but provides the rationale behind these behaviors to clarify why they are effective. To be clear, this is a strategy of emulating and replicating and not mimicking. By situating actions within familiar circumstances, such replication simultaneously reveals both the method and the outcome. Crucially, this process of social learning enriches the collective knowledge base, as each new iteration provides information on which strategies are effective, under what conditions, and for whom.

Groups with shared goals exchange information that aligns internal expectations, generating parallel evaluative frameworks despite ongoing variation. This alignment fosters the convergence of norms and behaviors both within and across groups, making expectations in settings like workplaces, schools, religious institutions, or social events widely recognizable and accessible. Once these normative domains are established, the underlying experiential knowledge must be curated and retained, serving as a reference point for future information evaluation and normative alignment.

Under our model, curation is an active process of preserving essential collective information that enables communities to manage uncertainty, coordinate behavior, and sustain evolving environments (

Figure 5). As a behavioral and cognitive mechanism, normative curation underpins the development and maintenance of norms and their supporting institutions by minimizing environmental and social uncertainty while maximizing the utility of shared knowledge.

Viewed through this information-based framework, curation structures domains of knowledge that guide social norms as adaptive informational scaffolds identifying what information matters, when it should be acted upon, and how it must be retained. Over time, this curated knowledge becomes organized into semantically bounded domains such as conventions, roles, rituals, and institutional protocols. These simple repeated performances reduce cognitive load and support coherent social navigation. These domains are not arbitrary, but instead are stabilized informational architectures that align individual understanding with collective social order.

This re-frames the ontology of norms and institutions not as imposed structures but as emergent outcomes of a population’s ongoing search for, and retention of, adaptive knowledge. It connects the micro-dynamics of experience and social interactions with the macro-dynamics of cultural evolution. The collective curation of social information thereby underwrites both the efficacy and adaptability of human sociality. As such, curation is not externally managed but internally enacted and diffused throughout the social fabric.

4.4. From Curation to Social Institutions

Over time, some domains of information reach a level of invariance. The patterns of action and belief are so deeply rooted that they become foundational (i.e., implicitly normative expectations). These invariant domains embody the “tried and true” methods through which communities meet recurring needs (e.g., securing resources, navigating environments, or interpersonal behavior). These patterns are not imposed, but rather become the baseline common knowledge. Their stability derives from repeated validation through use, not decreed by authority. This core body of

institutional information is rooted in all of our behavior (

Figure 6). In other words, institutional knowledge entails the body of instrumental information describing the essential

what,

how, and

why of the population’s primal needs.

Institutionalized information is not just what is known, but what is fully internalized by the population. It is living information actively shaping current behavior and expectations across generations. It forms the stable core of collective cognition, organizing essential knowledge that addresses fundamental human needs like food, shelter, and social belonging. Whereas norms and normativity correspond to a population’s allostatic adjustments, the information that is captured and curated as social institutions relates to a community’s long-term homeostasis.

Institutions arise out of domains of information that are crucial to the ongoing survival, continuity, and functioning of the population

as a community. For institutional knowledge to be effective, it must be applicable to most (if not all) members of a group. It must align with the normal distribution of human cognitive and behavioral capacities [

53,

54]. This knowledge is environmentally and contextually grounded, evolving through countless small adaptations to become widely embodied and culturally invariant.

As such, institutions function as filters and containers of domain-specific information structuring how groups process knowledge, coordinate actions, and maintain shared norms. This accessibility allows individuals to acquire institutional knowledge simply through participation and observation. This universal structure permits rapid social integration and mobility. Individuals can enter new groups or contexts and adapt quickly. Not because they are explicitly trained, but because they already share access to the same institutional knowledge structures. This system of shared knowledge enables large-scale societies, multicultural interaction, and collective resilience.

Social institutions such as politics, religion, education, or economics are each an expression of those core informational structures. Particular expressions of social institutions vary in form, yet are constrained by the deeper informational systems they represent. Institutions form the persistent macro-structure for curating and implementing a population’s information. Seen as part of a community’s information infrastructure, the role of institutions shifts from that of control or authority to one of conservation.

“An institution is the repository, not the arbiter, of collectively validated information and related practices. The basis of an institution then aligns to the curation of the collective and normative expectations that identify the bounds or limits of feasible equilibria within the identified domain of socially relevant information. Once these delimited ranges of potential equilibria coalesce, subsequent normative expectations within the bounds of those limits may take on institutional qualities in the traditional sense (e.g., proscriptive or prescriptive conventions).”

Social institutions stabilize collective behavior by embedding validated informational patterns into the social environment. By storing and organizing these informational domains, institutions reduce the cognitive burden on individuals while supporting the continuity and coherence of shared norms. Social institutions are therefore not intrinsically about power, but about continuity.

This re-conceptualizes institutions not as specific entities (e.g., governments, universities, churches) but as abstract patterns and information structures of social behavior. In this capacity, social institutions serve as externalized cognitive infrastructures preserving the outcomes of long-term social and environmental adaptation [

28]. This distinction allows for the redefinition of institutions as the underlying architecture of foundational information.

Re-framing social structures as the information that they encode allows us to understand the cross-cultural consistency of core institutions like education, economy, and governance despite their varied forms. Likewise, by focusing on the informational scaffolding of institutions, social scientists can better address their stability and adaptability in different contexts. In other words, this framing allows for more rigorous methods of diachronic and cross-cultural comparisons.

4.5. Bridging Culture and the Information Landscape

As described at the beginning of this article, we are information. Everything that we know is based on the structuring structure of that information. In Cardinal and Loughmiller-Cardinal [

28], we defined an

information landscape7 as the dynamic, distributed environment of social experience, belief, and context through which individuals and communities identify, interpret, and regulate meaningful information (

Figure 7).

This landscape is not a static repository of facts but a living, recursive system composed of the accumulated experiences, behaviors, and inferences of its participants. The information landscape is continuously generated, filtered, and adjusted as individuals interact with their environment and with one another. Therefore, the world we live in is based on the information we engage with, learn, accumulate, exchange, and update over the course of our lives.

“The information landscape is analogous to the biological concept of an evolutionary fitness landscape… Unlike the coevolution of genes or traits in biology, an information landscape represents the mutual information realized between an environment and mental representations of it… This coevolutionary process of socially mediated information underpins a collaborative search across the information landscape, through which the collective identifies feasible and potentially optimal information from which social norms are determined.”

The information landscape that each of us builds and maintains is formed from our experiences, our understanding, and the host of interconnections that have formed over time. This cognitive and epistemic terrain is the roadmap of how we know what we know and why we know it. The information landscape is both internal and external, both individual and collective. Internally, it includes the beliefs, expectations, and cognitive capacities of individuals. Externally, it encompasses the observable behaviors, environmental cues, social signals, and cultural materials that shape how information is collectively received and interpreted.

The landscape functions as a

shared cognitive ecology. It is a collectively constructed “space” representing the entanglement between social perceptions and the physical world that supports both personal sense-making and collective coordination. This model diverges sharply from representations of culture or normativity as fixed sets of rules [

44,

57,

58,

59]. The information landscape is not a product of top-down institutional design, but the emergent and entangled result of continuous feedback between individual exploration and group-level validation. The information landscape evolves in response to novelty, error, and environmental change allowing for the real-time recalibration of expectations and practices.

The robustness of the information landscape lies in its distributed architecture. It does not depend on any single actor, event, or domain. Rather, its integrity arises from redundancy, diversity, and continual recombination of inputs. As individuals join, leave, or change, the system adapts to preserve stable patterns while remaining open to innovation. This makes the information landscape one of humanity’s most powerful adaptive tools, enabling societies to operate effectively under conditions of uncertainty and complexity.

The information landscape is not merely a backdrop to human behavior, but the infrastructure through which that behavior is made possible. It is, in short, the “ground” on which the foundations of culture are set.

5. Culture and Structural Moments of Information

The emergence of social norms, convergence of normative expectations, and curation of institutional information all serve to produce and refine the topology of a group’s information landscape. It is this unique topology of information that appropriately characterizes a population as being a distinct cultural entity, not a particular collection of norms or institutions. Those can change over time, but the specific circumstances and historical trajectories that shape an information landscape can only be the product of shared experiences, information, and adaptations.

Social norms, normativity, and institutions constitute a complex and entangled set of processes integrating mutual information. As we have described, social norms represent a moving boundary across the information landscape as individuals contribute to the search for collectively optimal (i.e., effective and efficient) information. Normativity reflects the convergence of that search towards a stable allostasis. Institutions curate domains of information that promote a population’s homeostasis. Each is indicative of a particular aspect of cultural sociality, but none sufficiently define culture.

To define the whole system, we need a way to coherently describe the complex relationships

between those processes. We propose that these integrated systems of relationships—i.e., norms, normativity, and institutions—can be defined more productively (and formally) in terms of structural

moments of social information

8. In mathematics and statistical mechanics, moments are specific measures that describe the shape and characteristics of a surface or probability distribution. Each moment corresponds to a different feature:

The first-order moment is the central tendency, commonly seen as a “trend” or “average” of observations or events.

The second-order moment relates to the spread or dispersion around the central trend, also called “variance” or “deviance”.

The third-order moment describes symmetry or “skew” to events or observations, indicating a likelihood or weighting between extremes and around the trend.

Higher order moments of complex topologies can provide insight into the behavior at extremes or tails, such as the “peakedness” or tail heaviness (kurtosis) of a distribution.

These statistical tools have proven particularly useful in describing the behavior of complex or chaotic systems. In such systems, the macro-level states of the system are strongly dependent on the independent and nonlinear micro-scale interactions between individual entities or processes.

Culture and its constituent processes, as we have discussed here and elsewhere, is such a system of complex interactions. Statistical moments have already been applied to population biology and evolutionary modeling (e.g., [

60,

61,

62,

63]) to capture the complex, stochastic behaviors of populations under uncertainty, environmental variability, and genetic interactions. The information landscape entails characteristics similar to those of the fitness landscapes used to study evolutionary population dynamics, and its topology can be described in similar terms.

5.1. Moments of the Information Landscape

Under our model:

Social norms would constitute the first-order moment. They are the leading edge of social information searches identifying the central tendency of adaptive behaviors.

Normativity is the second-order moment, or stabilizing trend, by which the community identifies the allowable variation within social norms to maintain allostatic optimality.

Institutions are the third-order moment, providing the overall “shape” of the system by establishing and curating the distributional bounds for critical domains of information needed for homeostasis.

Social norms are a form of collective inference. They are an internalized “average” of shared experiences that forms a real-time cognitive map of collective understanding. This is the first-order moment of social information. Norms identify the “central trend” of collective experiences, indicating the “shape” or “contours” (i.e., the topology) of a community’s information landscape. Social norms represent the leading edge of a community’s search across the information landscape for optimality.

Normativity coordinates the collective coherence of the population’s information through mutual expectations instead of authority or enforcement. It is the expectation through which others in the community are able to evaluate the propriety of an individual’s beliefs or actions. In effect, it reconciles individual information landscapes (derived from personal experiences) with the collective landscape. This is the second-order structural moment of social information (i.e., its “variance”), representing the permissible diversity within the community. It establishes the range of expectations within the community that can be reasonably anticipated by its members and what is considered “normal” for the group.

Third-order moments describe what can be thought of as the overall “shape” of a culture’s “distribution”—i.e., its combination of trends, biases, variance, and structure. When applied to social information within a population, these can also be viewed as analogous to characteristics traditionally associated with social and cultural institutions. Instead of exerting regulatory authority, institutions are merely reflecting the inherent structures and practices emerging from the population’s curated information. This effectively describes the organizing structure of the population’s social network.

Each higher-order structural moment describes the topology of a population’s information landscape in increasing order of informational stability. That is, the information represented in social norms (first-order moment) is relatively fluid, whereas institutions (third-order moment) curate the most stable or reliable information. Each derives from the particular configuration of a population’s information landscape. Culture, however, is not just the next higher-order level of structural moment. Culture refers to the total collection of structural moments required for a population’s information landscape to converge to a stable, homeostatic equilibrium.

5.2. Culture, Adaptation, and Social Complexity

There are two inevitable, physical truths about all living organisms. The first is that nature is lazy and will always favor the lowest-cost solutions. The second is that energy is limited, so evolution tends toward efficiency [

64,

65]. The normal behavior of any organism is to strive towards an energetic balance under which all primal needs are satisfied and continuity is achieved (i.e.,

homeostasis; see [

47,

66]).

As stated above, human cultural sociality facilitates the retention and distribution of information about satisfying the primal needs of being human—i.e., food, shelter, safety, and a mate. Our vast and complicated network of information is specifically designed to keep all of us in balance with our energetic needs and the requirements of life. Under dynamic conditions, that balance is achieved through constant allostatic adjustment.

We naturally update the requirements for our continued adaption to changes in our environment. It is not enough for us to survive individually. We must survive collectively and needs must be met within ever-changing environmental conditions. Therefore, the objective is inherently a homeostatic equilibrium that enables both individuals and the population as a whole to be sustained.

Unlike most organisms, however, humans occupy a wide range of environments [

51,

67,

68,

69]. Our form of cooperative behavioral adaptation and our ability to employ socio-technical innovations allow us to adapt beyond our individual biological limitations. To do so, we utilize the system of adaptive information search to identify optimal allostatic regulation under diverse conditions.

The first- and second-order moments (i.e., norm search and normative convergence) establish the conditions required to optimize an information landscape under novel environments. Once established, that information determines what is required to achieve the necessary homeostasis for the population within that environment.

Culture, therefore, can be understood as the unique configuration of structural moments describing the total information landscape needed for a population’s homeostatic requirements under local conditions.

Culture reflects the specific conditions arising from that population’s system of behavioral information processing. Each moment reflects the overall configuration of the entire system, uniquely characterizing the composition of experientially validated information over time. Culture, as such, describes not only what is done but how a population organizes and retains the information necessary to know what to do through its unique information landscape. Therefore, culture can be defined as follows:

Culture (as an unspecified noun): the configuration of structural moments defining a population’s information landscape.

Culture (as a specific expression): the unique expression and/or characteristics of structural moments for a population-specific configuration of an information landscape.

So, why do we have this seemingly unique capacity for collective social adaptation, and how is it that so much is occurring without our conscious attention and control? It is because this complex system of cultural sociality evolved to allow our species to adapt to the widest possible range of conditions with the fewest unnecessary expenditures of energy. Our capacity for social and collective cognition allows us to explore, discover, and synthesize massive and diverse quantities of experiential information quickly and efficiently. It allows a diverse population to cooperate and coexist under nearly any conditions.

Defining culture in this way also resolves another long-standing question in the social sciences—what is social

complexity? Traditionally, discussions of social complexity have been mired in problematic teleological implications of historical theories and explanations [

70,

71,

72,

73,

74,

75]. Defining culture in terms of a configuration of structural moments obviates these issues and offers a clear explanation for why variation exists between cultural expressions (e.g., mores, formal institutions, differentiation of roles, and social organization).

Social complexity is merely the depth and elaboration of the structural moments required for a population to achieve homeostasis within that population’s available environment and resources. Therefore, the particular form that any such behavior takes should not be evaluated comparatively regarding its form and configuration, but the role that it fulfills and its stability. Once homeostasis is met, further social elaboration is only necessary if and when conditions necessitate structural alteration of the information landscape.

Social complexity is therefore not a relative measure of a culture’s evolution or “advancement” but a matter of need and efficiency. In fact, we have had it backwards. If complexity indicates the balance of diversity needed for homeostasis, the more complex a population is the less efficient it is. The range of solutions is not the product of evolution but those necessary to achieve large-scale homeostasis.

6. Implications for Methodology and Theory

Culture is best understood as a multilevel information-processing system, not as a static collection of traditions. Norms, institutions, and cultural patterns emerge from recursive processes that curate, stabilize, and optimize social knowledge across time. This model bridges theoretical gaps between structure and agency, reframes archaeological inquiry, and informs more dynamic approaches to understanding cultural processes and expressions.

Emphasizing information management as the core function of culture offers a robust and scalable framework for understanding human adaptation, resilience, and transformation. It redefines culture as a dynamic information-processing system—shifting the focus from symbolism, materiality, and social structure to how knowledge is curated, transmitted, and optimized for social adaptation. This challenges prevailing theories by positioning information flow and cognitive processing as the core mechanisms shaping cultural evolution, social organization, and human adaptation.

So, how does this look in practice? The substantial change is not in the answers we seek, but the questions that we ask. The research outlined above allows for a fundamental shift from the traditional platform of etic and emic description. We can move past empirical observations and description into explanatory how and why questions. Informational structures and moments allow us to examine:

How can two (or more) groups answer the same question differently?

How can the same phenomena express themselves differently in two adjacent locations?

How can similar solutions appear independently in time and space?

How are human cultures substantially alike or substantially different, rather than comparison of superficial traits?

Our model contrasts with classical sociological and anthropological theories by:

De-emphasizing enforcement and sanctions: Rather than focus on culture as an external force that regulates behavior, this model sees it as a natural process for efficient information sorting.

Prioritizing collective cognition over social control: Instead of being imposed through enculturation of institutions or hierarchies, culture emerges from the collective need to organize experiential knowledge and reduce uncertainty.

Entanglement between individual and collective agency: Traditional models often separate individual choices from societal structures, whereas this model views cultural behavior as an entangled process of both individual cognition and collective optimization.

This model synthesizes elements of cultural evolution, network theory, and complexity theory in suggesting that societies thrive when their information landscapes efficiently structure and distribute critical knowledge within their physical and social contexts. Unlike previous models that focused on either structure or agency, this approach emphasizes how cultural norms and institutions dynamically evolve to regulate uncertainty and enhance individual and collective fitness. It defines norms, normativity, and institutions as structural moments on an information landscape, with each moment reflecting the increasing stability of its emergent cognitive and social processes.

In doing so, this model offers a formal framework for understanding the emergence, stability, and transformation of cultural systems. This marks a substantial shift away from static or symbolic definitions of culture toward a more fluid, cognitive–evolutionary perspective that foregrounds adaptive learning, distributed memory, and informational optimization. In this view, societies do not merely transmit traditions but actively optimize their information landscapes, ensuring that cultural institutions remain adaptive rather than rigid constraints.

This bridges the cognitive processes of individuals, the institutional memory of societies, and the sustainability of cultural systems in response to uncertainty and change. The shift from static models of cultural stability to dynamic frameworks of information processing represents a profound transformation in the study of social norms and institutions. This reorientation offers new methodologies for examining historical and contemporary societies, particularly in understanding cultural identity, civil society, institutional collapse, and behavioral change.

Defining culture as a structured information landscape positions norms as emergent features of

collective cognitive calibration. Norms are not imposed rules but are dynamically inferred generalizations from socially distributed experience. They arise from the need to minimize uncertainty, reduce cognitive load, and increase the intelligibility of social behavior. Normative convergence, then, is a form of

collective Bayesian updating—a recursive filtering of experience that privileges effectiveness over authority [

76,

77].

Similarly, institutions are not static or hierarchical structures but long-term memory systems. They curate essential knowledge ranging from kinship systems to technological practices and preserve it across generational time. Their durability reflects the accumulated validation of practical knowledge, not the coercive power of elite classes. This aligns with arguments that institutions evolve to match human cognitive constraints and ecological conditions [

53].

For archaeology, this framework redirects attention away from interpreting material remains through economic or political models that underemphasize the role of information. Instead, our model suggests we explore how knowledge was curated, transmitted, and embedded in material forms (e.g., [

78]). Sites, monuments, archives, and technologies can be reinterpreted as

information hubs. They become “landmarks” on the information landscape where critical knowledge was stored, protected, or exchanged.

Temples and ritual centers are no longer reserved for the elite, but provide mnemonic infrastructures informative of the population as a whole. These repositories of symbolic and procedural knowledge speak to community coordination and ecological adaptation, not just heavy-handed practices using system-wide approaches.

Societal collapse can also be re-framed as a breakdown of informational coherence. When institutions can no longer filter, update, or distribute critical knowledge the systemic coherence and resilience of the system deteriorate (cf. [

15]). This reorients archaeology toward analyzing how knowledge systems were maintained or lost. Collapse is not merely political disintegration but the decay of distributed cognition. Even post-collapse societies often retain localized knowledge systems, supporting the idea that resilience hinges on the

flexibility of information flow rather than on structural rigidity. This also clarifies why a healthy system remains resilient through certain traumatic events while, in other situations, the same type of event leads to failure.

Likewise, cultural studies and heritage management could benefit from our model’s emphasis on information dynamics. Heritage is not static memory but active curation, embedded in social practice and informed by evolving information landscapes. This approach moves beyond debates about authenticity, and instead focuses on the continuity and transformation of shared knowledge.

Norms and institutions must be understood as adaptive, not merely conservative. Change is not necessarily loss, but transformation in response to updated knowledge. Community engagement must recognize that heritage is part of a living information system. Practices persist not through preservation alone, but through iterative validation and reintegration into social life. This supports more sustainable heritage strategies by aligning preservation efforts with ongoing social relevance, cognitive accessibility, and communal intelligibility. Furthermore, such understanding is essential in educational design.

Concretely defining the abstract and under-specified concepts used by social scientists, such as social norm, institution, and culture, is not simply a matter of academic or intellectual precision. In doing so, we can more effectively engage with the world outside of our narrowly specialized areas of study and research. By reconciling these concepts within and between disciplines, we can provide a robust set of methods and tools with which to understand and communicate our common challenges and goals—providing a wealth of information regarding the true historical depth of human adaptability and resilience.