1. Introduction

The integration of multiple disciplines in the study of conservation is essential to better understand the complex interactions between the constituent materials of cultural heritage and their surrounding environment. In addition, the knowledge of conservation history provides valuable insights into the transformations and interventions that may have affected the artworks and the objects over time.

Within this framework, the present work was carried out through the collaboration of research teams from the Departments of Chemistry, Physics, Biology and Historical Studies at the University of Turin focusing on the case study of the King’s Apartment in the Royal Palace of Turin (Italy). This multidisciplinary approach integrated historical perspective with scientific analyses, supporting preventive conservation strategies based on evidence and reflecting the inherently integrated nature of heritage science. The scientific activities considered key parameters influencing conservation environments, including chemical and biological air quality and microclimatic conditions.

In recent decades, indoor air quality has attracted growing scientific attention in cultural heritage environments [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. Pollutants and suspended particles, including the bioaerosol, are considered a potential risk for the correct conservation of works of art, since they can initiate or accelerate chemical and physical degradation [

1,

13,

14] as well as biodeterioration processes [

15,

16]. It is well known that pollutants and particles of biological origin can be dangerous also for human health [

17,

18] and in the context of museums and heritage sites, staff and visitors may experience prolonged exposure, making the control of indoor air quality crucial not only for conservation purposes but also for health and safety. Pollutants may originate from outdoor sources, such as traffic emissions, industrial activities, and combustion, which can infiltrate into indoor environment, where contaminants sources are also present: emissions can originate from construction and finishing materials, display cases, furniture, conservation treatments, cleaning agents and the heritage objects themselves [

5,

13,

14].

Among the wide range of pollutants, Total Volatile Organic Compounds (TVOC) pose a serious risk and the evaluation of their concentrations is of fundamental importance in heritage conservation environments. These compounds can interact with cultural materials, leading to physical alterations, corrosion, discoloration, polymer degradation or changes in chemical composition that compromise their conservation [

5,

12,

19].

The threshold limits for air pollutant concentrations in museums are not universally regulated but research institutes and conservation organizations in various countries [

19], including the Canadian Conservation Institute [

13] and the Getty Conservation Institute [

5] defined recommendations. These recommendations suggest that TVOC concentrations up to approximately 200 ppb are generally considered tolerable for most collections, although continuous monitoring is advisable to detect any fluctuations or emerging sources. Concentrations between 200 and 500 ppb indicate a moderate risk, suggesting the application of preventive or corrective mitigation measures. Levels exceeding 700 ppb are considered potentially harmful, not only to sensitive materials but also to human health, given the possible presence of irritants, sensitizers, or toxic compounds within the TVOC mixture [

17]. Maintaining TVOC concentrations below the threshold is critical for risk management strategies, since this contemplates not only periodic instrumental monitoring but also a proactive approach for the identification of the sources and their eventual mitigation or elimination before they become a serious risk.

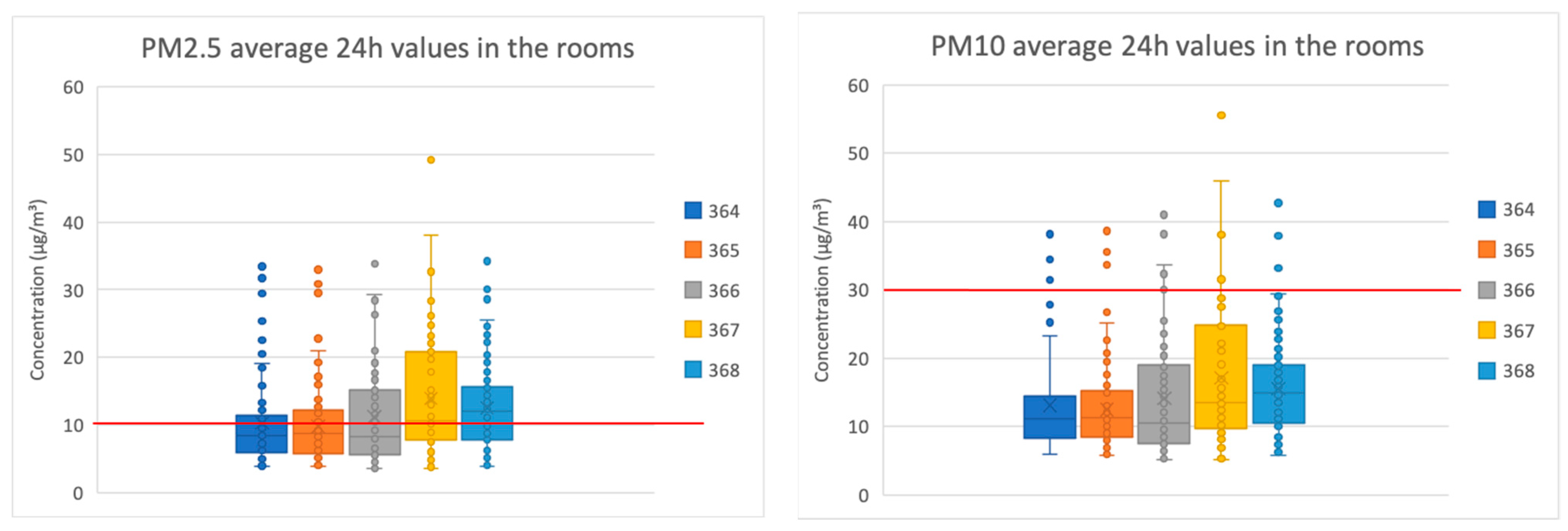

Another potential harm for cultural heritage is particulate matter (PM), a complex mixture of solid particles suspended in air, varying widely in size, composition, and origin. PM is generally classified by aerodynamic diameter, with two widely monitored fractions: PM

10 (particles with a diameter ≤ 10 µm) and PM

2.5 (particles with a diameter ≤ 2.5 µm) [

2,

8].

From a health perspective, PM

2.5 is considered more harmful than PM

10 because of its deeper penetration into the respiratory system and its ability to translocate into the bloodstream, contributing to cardiovascular, respiratory, and systemic effects. The guidelines by the World Health Organization and Europe Commission set the 24 h mean exposure limits at 15 µg/m

3 for PM

2.5 and 45 µg/m

3 for PM

10 [

17,

20].

In heritage conservation, PM is also of concern for its impact on cultural materials as it can deposit on the surface of the object and interact with it. Coarse particles may cause soiling and abrasion, while fine particles can penetrate porous materials, induce chemical degradation, and contribute to the deterioration of pigments, metals, and organic substrates [

2,

13,

21]. Limits for PM concentrations inside cultural buildings are not established; however, it is possible to refer to guidelines proposed by national and international organizations. The Italian Ministry of Cultural Heritage and Activities, through the Ministerial Decree of 10 May 2001 [

22], recommends a threshold value of 20–30 µg/m

3 for PM

10. For PM

2.5, the adopted reference limit corresponds to the ASHRAE maximum value of 10 µg/m

3 [

23].

Airborne microbes, including fungal aerosols (mycoaerosols), also influence the indoor air quality, as they can determine adverse health effects including allergies, infections and inflammations [

24]. In the case of museums, libraries and other indoor heritage sites, airborne fungal spores can thus threaten operators and visitors, but they also pose a potential risk of biodeterioration to the heritage materials, as under suitable nutrient and microclimatic conditions they can germinate and start colonization [

15,

25]. Accordingly, aerobiological monitoring has been long included in the recommended practices for preventive conservation [

26].

Despite this growing attention to indoor air quality, numerous studies have focused on understanding the microclimate conditions in collection spaces. However, as highlighted in the review by Vergelli et al. [

27], investigations on organic chemical species in indoor conservation environments remain limited, and continuous monitoring devices are still underused in cultural heritage settings compared to their widespread application in health-related studies. Moreover, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, most studies have focused on a single type of monitoring (microclimate, aerobiology, or gaseous pollutants) or on combinations of two of them [

21,

28,

29,

30]. Integrated monitoring approaches covering all three aspects remain uncommon, and the few existing examples [

4,

31,

32,

33], generally rely on measurements conducted over relatively short periods.

The present study shows the results of the monitoring activities carried out in rooms of the King’s Apartment in the Royal Palace of Turin (Italy), with the aim of defining the microclimatic and air-quality conditions of this environment. Through the systematic and reasoned collection of data and their interpretation, the study provides valuable elements for planning preventive conservation actions.

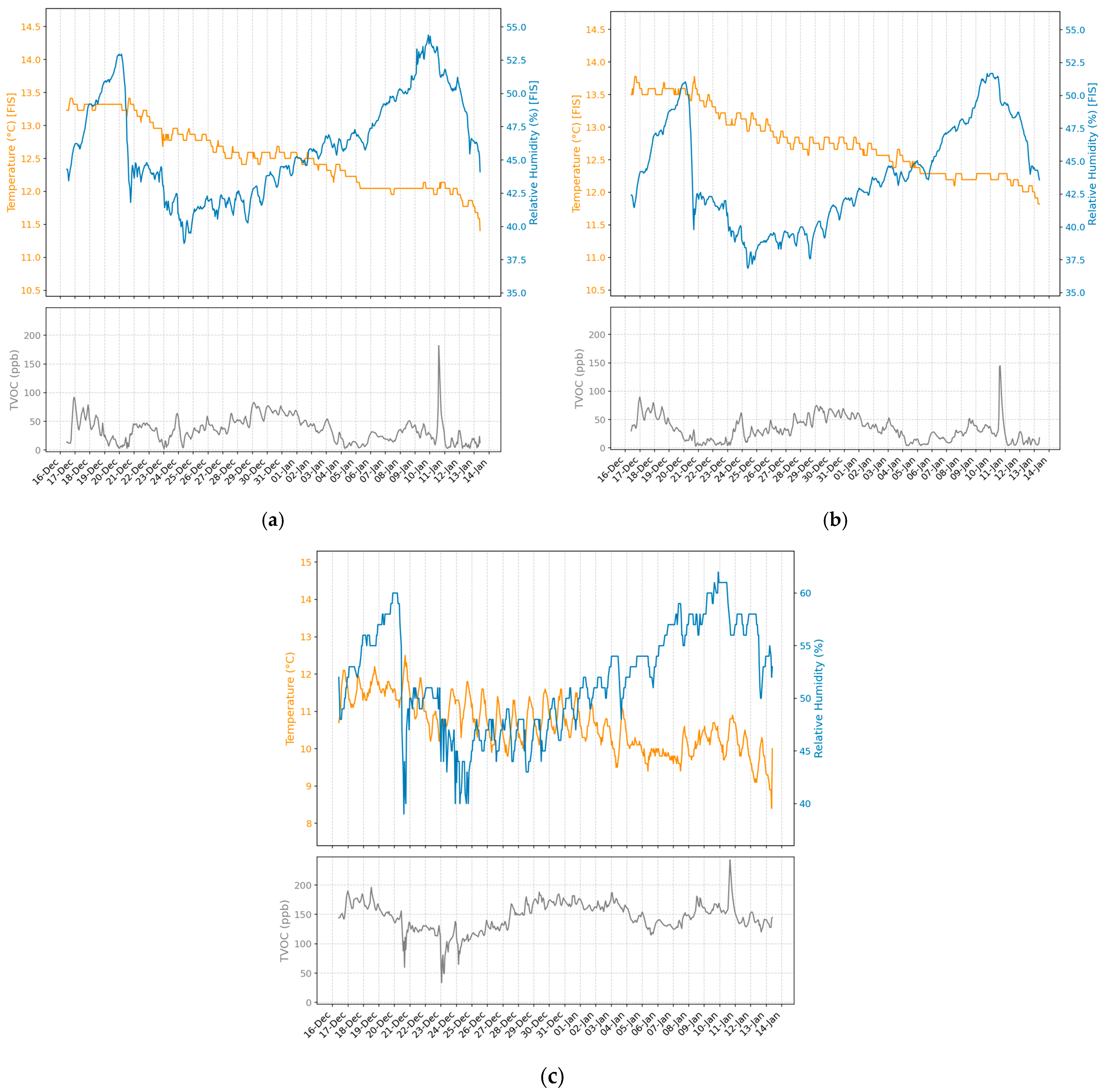

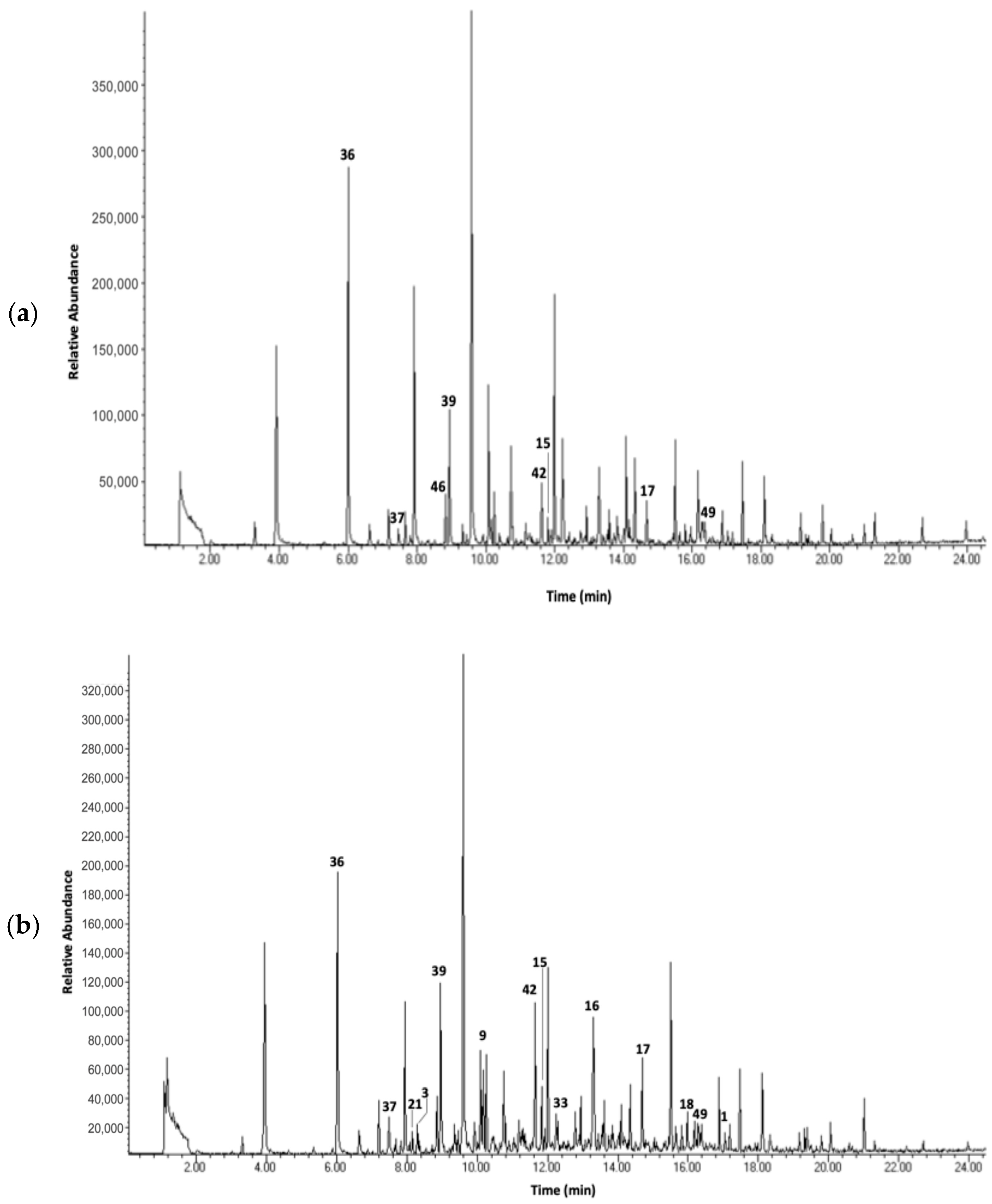

The proposed monitoring plan combines low cost continuous instrumental measurements of microclimatic variables, TVOC and particulate matter (PM2.5 and PM10) with identification of chemical species through solid-phase microextraction coupled with gas chromatography mass spectrometry (SPME-GC/MS). The concentration of fungal spores, both viable and non-viable, and distinguished in different morphological classes, was also monitored using a Hirst-type volumetric sampler.

This integrated approach not only allows for the quantification of pollutant concentrations but also provides qualitative insight into their chemical nature, allowing a better understanding of potential emission sources. Furthermore, the study reveals significant spatial and temporal variations in pollutant levels that are critical for informing conservation strategies.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Historical and Environmental Context

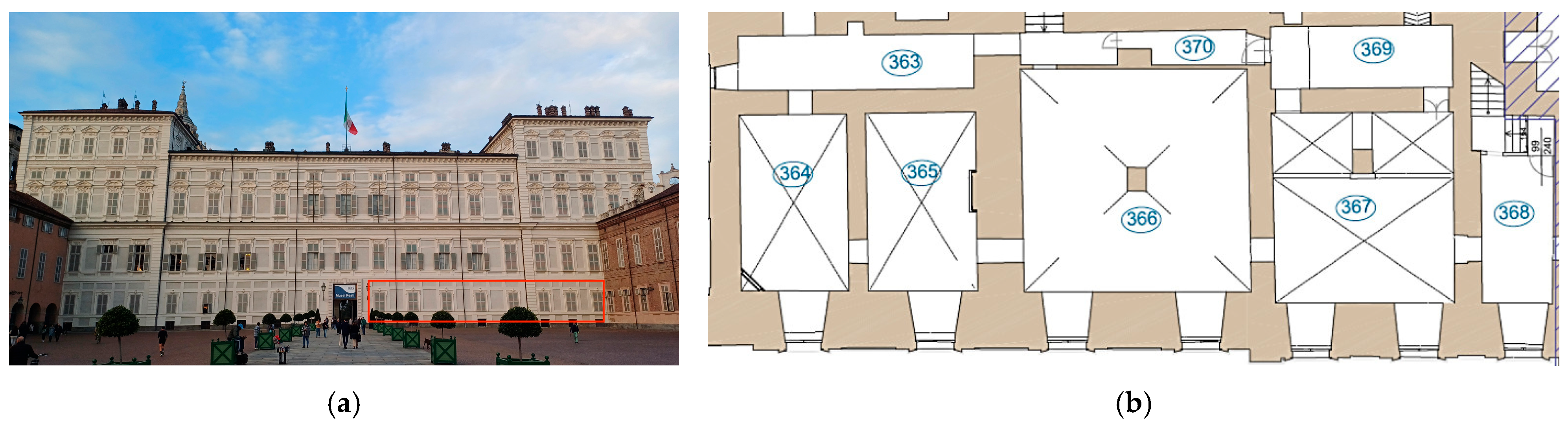

The King’s Apartment, located on the ground floor of the Royal Palace of Turin, Italy (

Figure 1a), owes its name to Vittorio Emanuele III, King of Italy, who stayed there between the 1920s and 1946. Designed by Ascanio Vitozzi (1539–1615) and then completed by Maurizio Valperga (1605 ca–1688) and Carlo Morello (†1665), it is composed of 5 principal rooms along with several connecting and service spaces overlooking the Piazzetta Reale, a small external courtyard located within the Palace complex.

The apartment is in a generally good state of conservation, with some critical issues. It still contains various valuable furnishings, precious objects, and works of art (

Figure 2). A brief description of the various rooms and their main features is provided in

Table 1.

As Clemente Rovere testifies in his Description of the Royal Palace of Turin [

33], from the second half of the 17th century onwards, the Apartment served as the accommodation of the Court nobles.

In the summer of 1693, during the reign of Vittorio Amedeo II (1666–1732), the decoration of the rooms of the King’s Apartment began. In 1753, by order of His Majesty Carlo Emanuele III, based on a design by Benedetto Alfieri, new interventions were carried out, mainly concerning the decorative apparatus of the late 17th century, which was removed.

At the beginning of the 19th century, the Apartment was the seat of the French governor of Turin. Later, during the reign of Carlo Alberto (1831–1849) many rooms were radically renovated under the direction of Pelagio Palagi (1775–1860). From 1870, it became the home of Princess Maria Clotilde (1843–1911), daughter of Vittorio Emanuele II and Queen Maria Adelaide.

When in 1925 the crown prince Umberto (1904–1983) settled on the second floor in what had been the apartment of the King and Queen, King Vittorio Emanuele III (1869–1947) moved into the Apartment, which has since taken on its current name.

With the birth of the Republic in 1946, it became state property and was transformed into a museum, partially opened for the first time in 1963 on the occasion of the Piedmont Baroque Exhibition curated by Vittorio Viale, and today it is still only opened on certain occasions.

With no active heating or air-conditioning systems, the internal environmental conditions reflect the historical character of the building, while also presenting unique challenges for the preservation of the rooms.

During the monitoring period presented in this study (March 2024–July 2025), the apartment remained closed to the public, with access limited to sporadic guided visits. In the weeks following July 2025, regular public access was restored, and environmental monitoring is currently ongoing to assess the impact of this change in visitor presence on indoor air quality.

To provide an external reference framework for the present study, we referred to two reports published by the Regional Agency for the Protection of the Environment of the Piedmont region (Agenzia Regionale per la Protezione Ambientale, ARPA Piemonte), [

34,

35], which summarize the state of outdoor air quality in the metropolitan city of Turin during the year 2024. These outdoor data were used solely as a contextual indicator of the general air quality conditions in the city since ARPA does not monitor TVOCs but specific pollutants (e.g., benzene, PM

2.5, PM

10). First, ARPA considers the area of interest of this study (center of Turin) as a traffic-urban area. Both documents indicate that benzene levels in the Turin metropolitan area remained below regulatory limits. As for particulate matter, PM

10 meets the annual limit across all stations, although the daily limit exceeded in about 22% of monitoring sites and 2024 showed a deterioration compared with 2023. PM

2.5 remained within the annual limit at all stations, with stable or slightly decreasing averages. These outdoor data served as a general background reference for interpreting indoor air quality in the King’s Apartment.

2.2. Methods

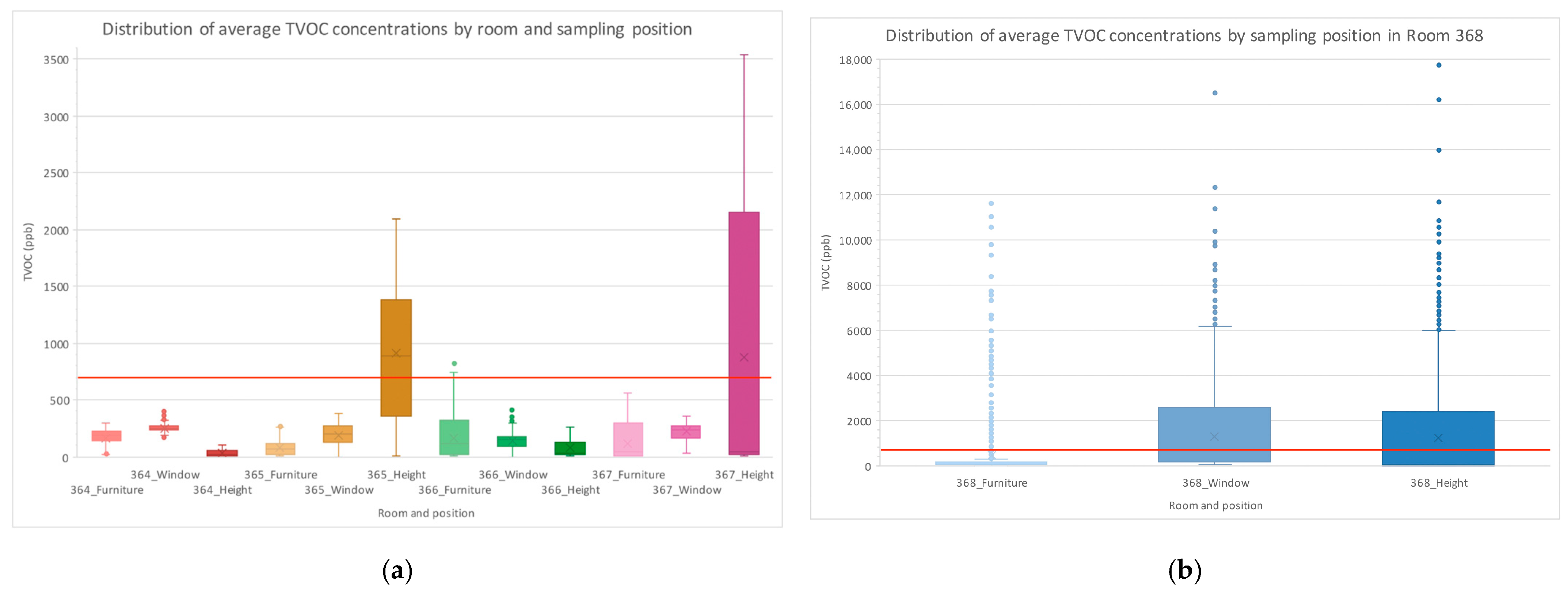

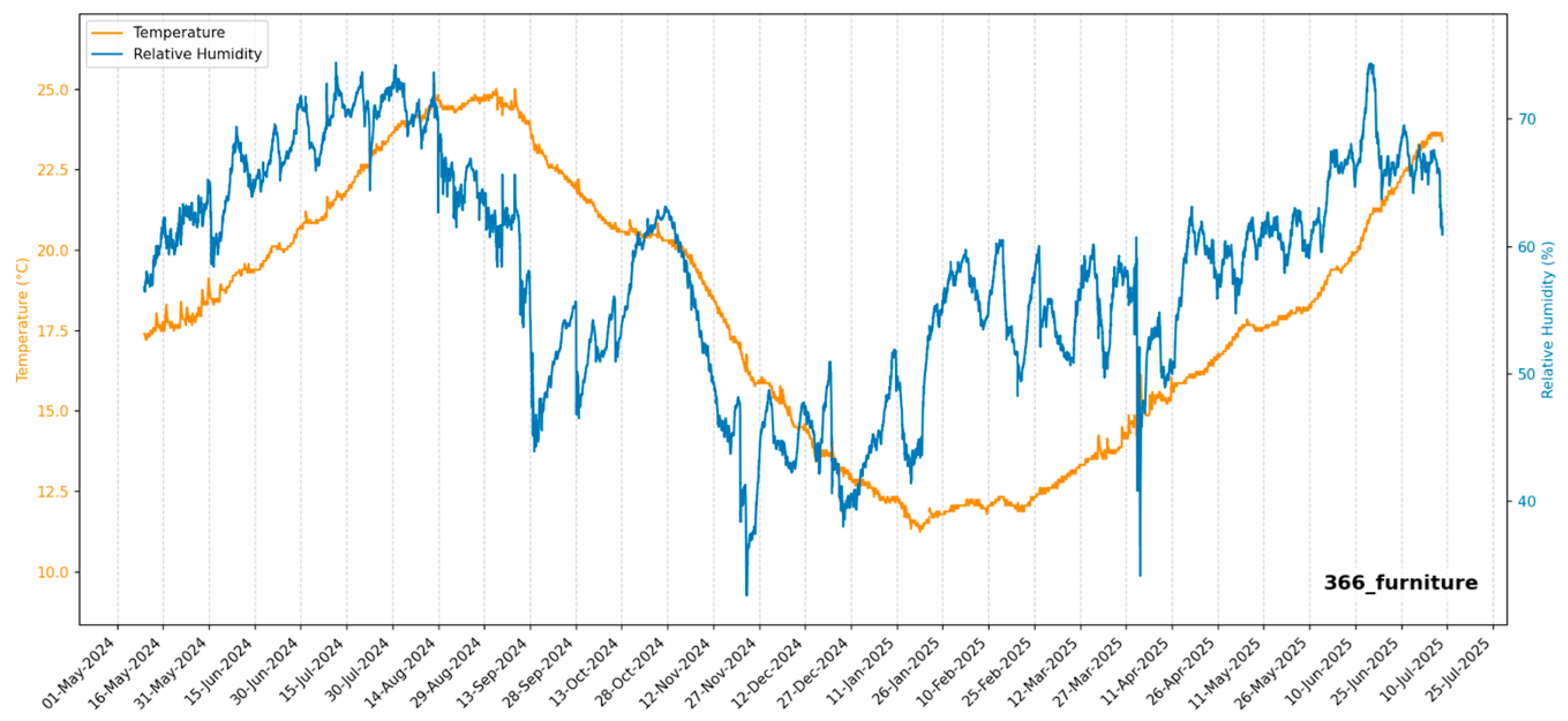

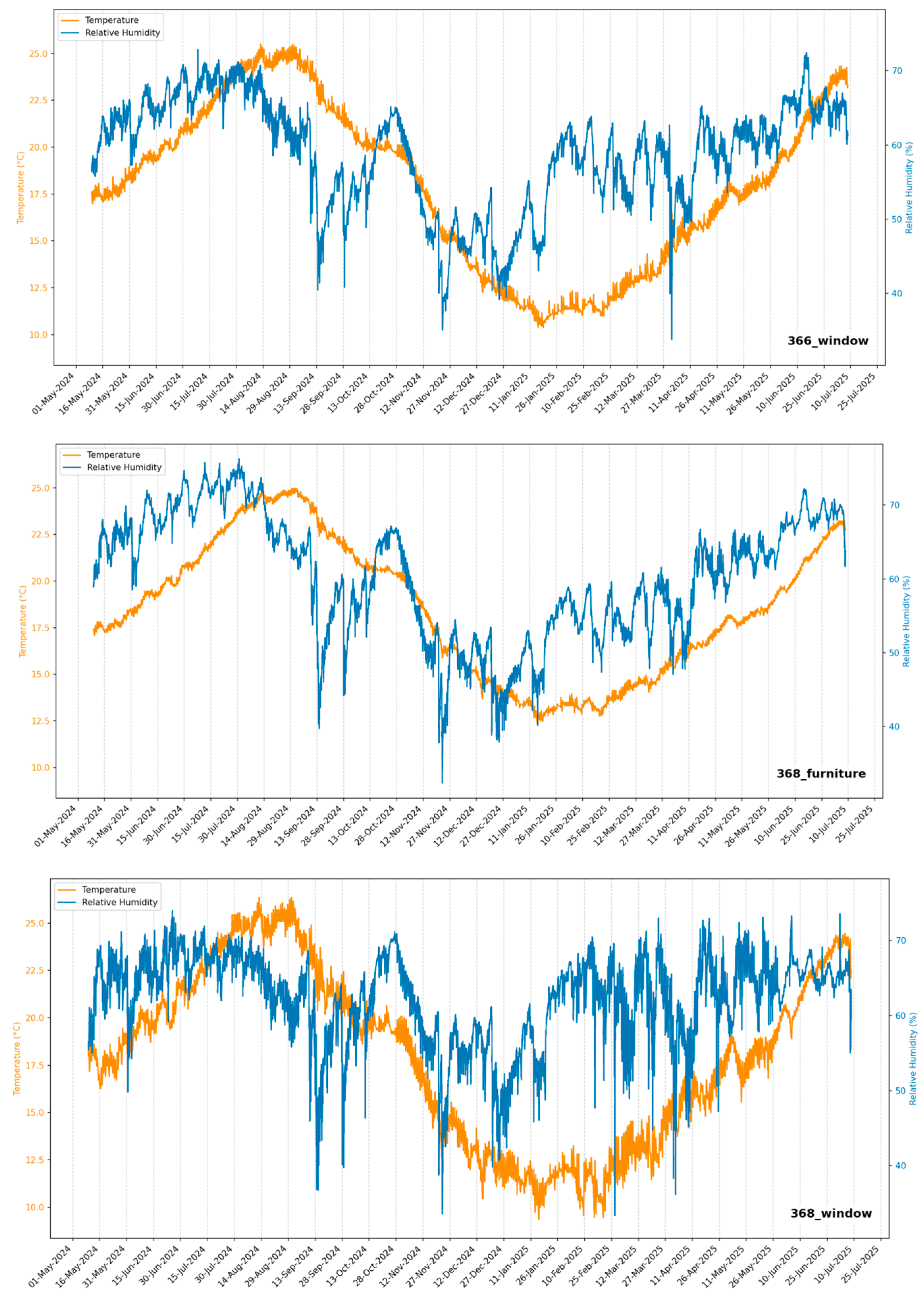

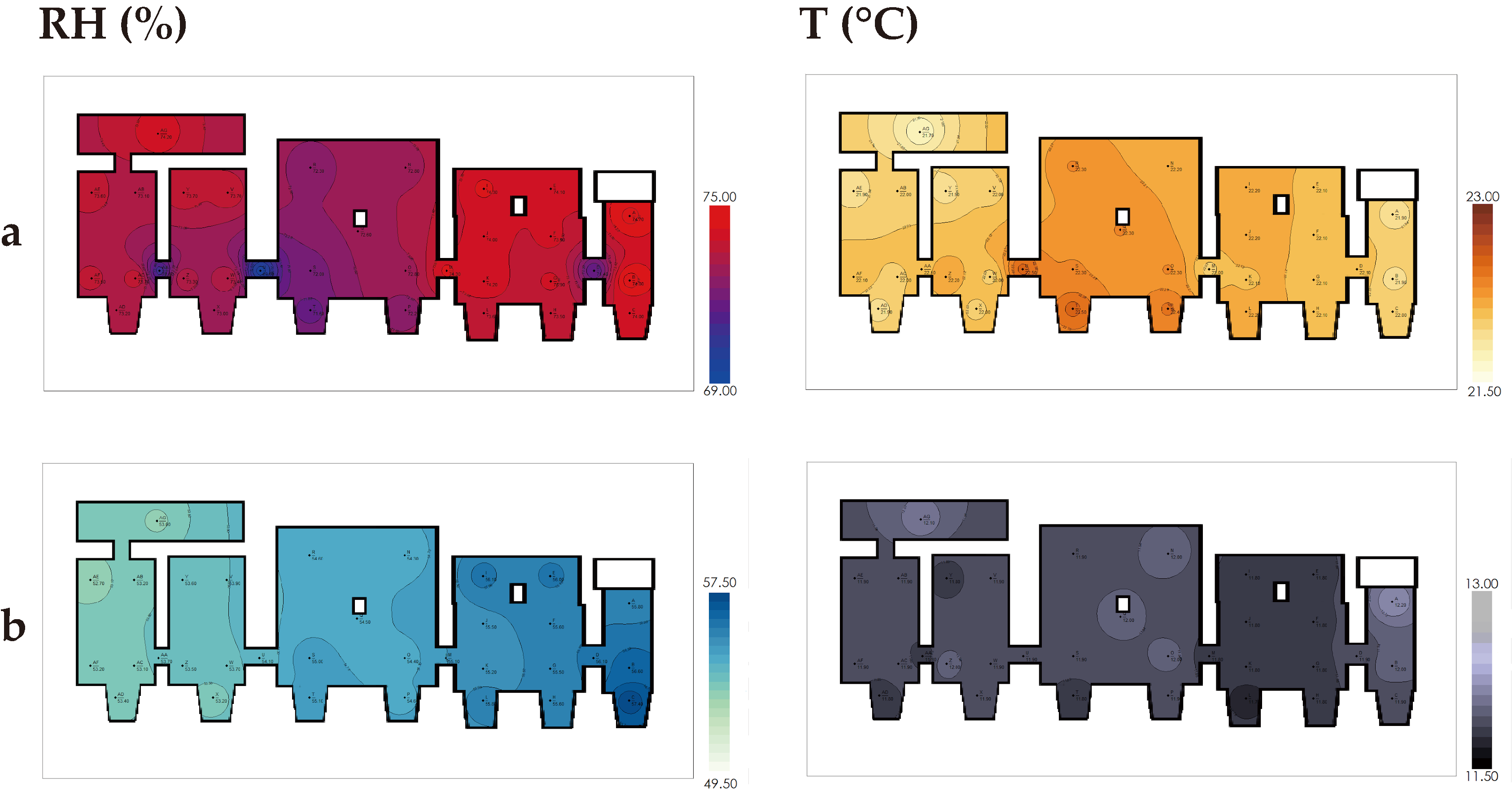

Sensors for continuous monitoring of air quality and thermo-hygrometric sensors were positioned in different points of the rooms and at different heights, from 1 m from the ground up to 3 m: the thermo-hygrometric sensors, more numerous, covered the entire area of the apartment, while the sensors for the detection of TVOC and PM were rotated over time at regular intervals in order to obtain information on the spatial (i.e., near the windows and on the opposite side of the room) and vertical distribution (at the level of 1 m from the floor and at about 3 m) of the pollutants.

Continuous TVOC detection was complemented by SPME-GC/MS analysis, which are non-invasive and suitable for historic environments, and allowed for the precise identification of the chemical species involved.

In addition, the air quality assessment was completed by bioaerosol analyses, specifically dedicated to the quantification of fungal spores (mycoaerosols), and carried out with a Hirst-type volumetric sampler [

25,

36,

37].

The information on the types of devices used for monitoring, their placement in the various rooms of the Apartment, and the measurement methods and timing are collected in

Table 2, while further experimental and instrumental details on the analyses performed are reported in

Appendix A.1.

4. Conclusions

The monitoring campaign conducted in the King’s Apartment of the Royal Palace of Turin provided new insights into the indoor air quality of historic environments closed to the public for extended periods. This study exemplifies the importance of a multidisciplinary approach in heritage conservation, combining chemistry, physics, biology and historical studies to better understand the interactions between cultural materials and their environment and to support conservation strategies. Furthermore, the coupling of relatively complex, time-consuming and costly analyses, such as SPME-GC/MS, with much cheaper ‘black box’ air quality analyzers allows for qualitative comparison and mutual validation.

Continuous sensor-based measurements revealed that TVOC levels were generally below the threshold of 700 ppb, yet unevenly distributed within the rooms, with vertical stratification and proximity to windows emerging as key factors. The anomalously high VOC values in Room 368 (i.e., up to 18,000 ppb), associated with the highest detected spore concentration (i.e., 1716 spores/m3, approximately double the average concentration recorded in the apartment), further underline how enclosed and poorly ventilated spaces can promote pollutant accumulation.

Conversely, concentrations of particulate matter frequently exceeded recommended limits, with PM2.5 often reaching the 24 h mean exposure value of 30 µg/m3, and peaks of fungal spores were remarkable, confirming conditions of compromised air quality that may endanger the long-term preservation of sensitive materials. In the absence of a controlled air-forced system, influences from external factors are unbalanced and may promote conditions threatening material conservation and health.

The complementary use of SPME-GC/MS enabled the identification of a wide range of volatile organic compounds, tracing them back to sources, both internal (such as building materials, furniture, cleaning activities) and possibly external (traffic and industry emissions). The detection of specific markers underlines the importance of chemical characterization in understanding the origin of pollutants and their long-term impact on collections.

By combining continuous monitoring with targeted chemical analysis, this study demonstrates an integrated framework capable of capturing both real-time variations and the molecular fingerprint of indoor pollutants. This approach is particularly relevant in historic buildings, which often lack air conditioning and ventilation systems, and where complex interactions between materials, environmental conditions, and human presence call for multi-layered diagnostics.

Given the potential risks posed by chemical pollutants and biological contaminants, the systematic monitoring and assessment of indoor air quality constitute essential components of preventive conservation. This approach not only enables the identification of pollutant sources but also supports the development of targeted mitigation strategies, thereby reducing the potential for degradation and ensuring the preservation of cultural assets for future generations.