Semantic Collaborative Environment for Extended Digital Natural Heritage: Integrating Data, Metadata, and Paradata

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The State of the Art

2.1. Evolution of Natural Heritage Data Management Environments

2.2. Evolving Standardization by Integrating Metadata, Paradata, and 3D Data Management

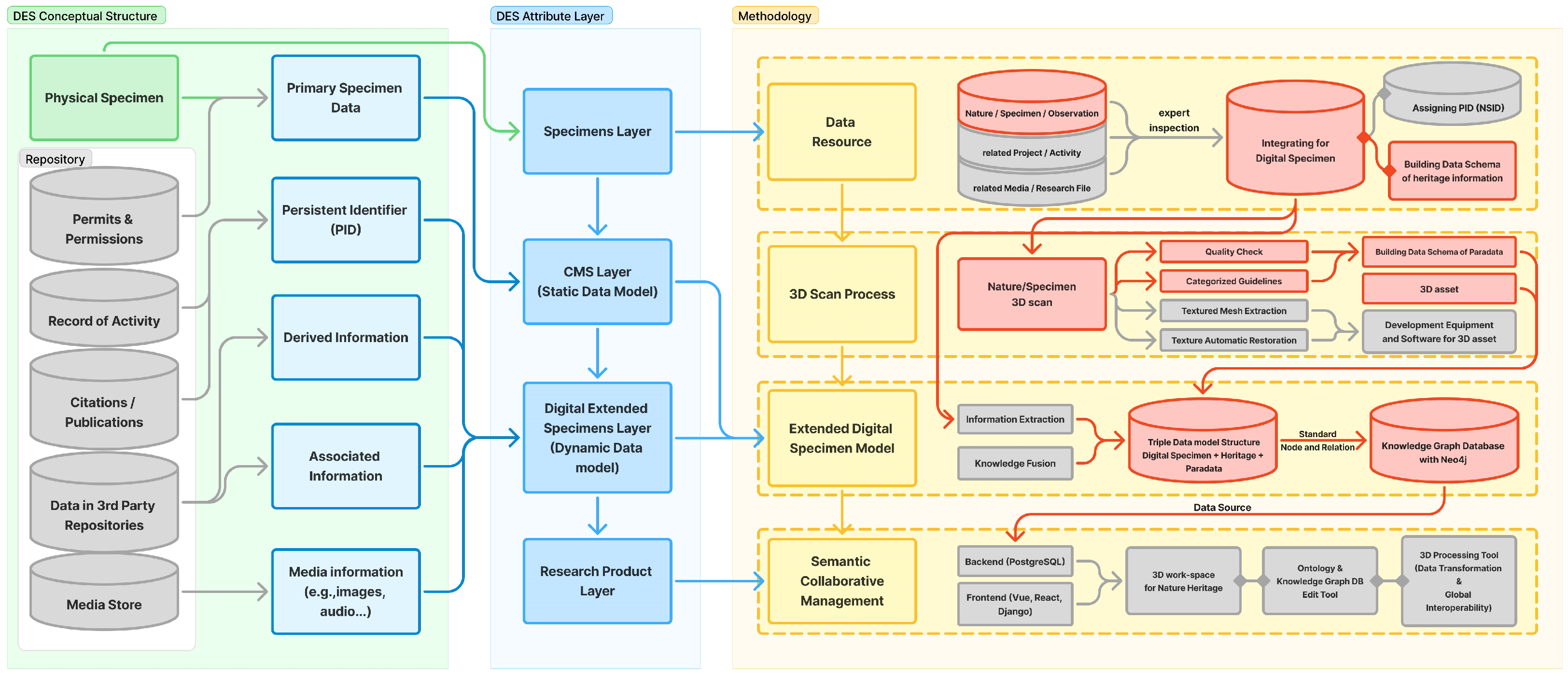

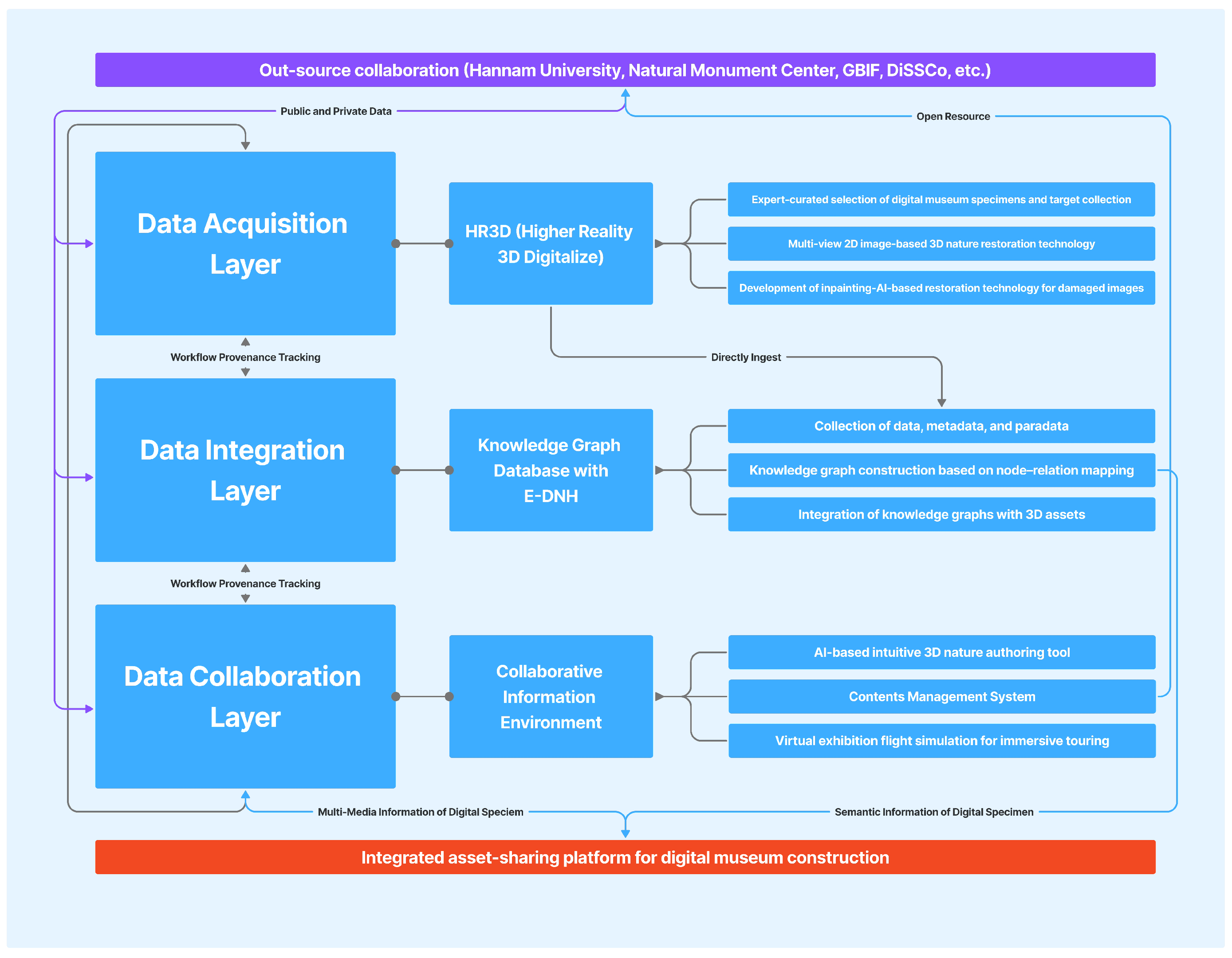

3. Methodology

Data Resource Layer

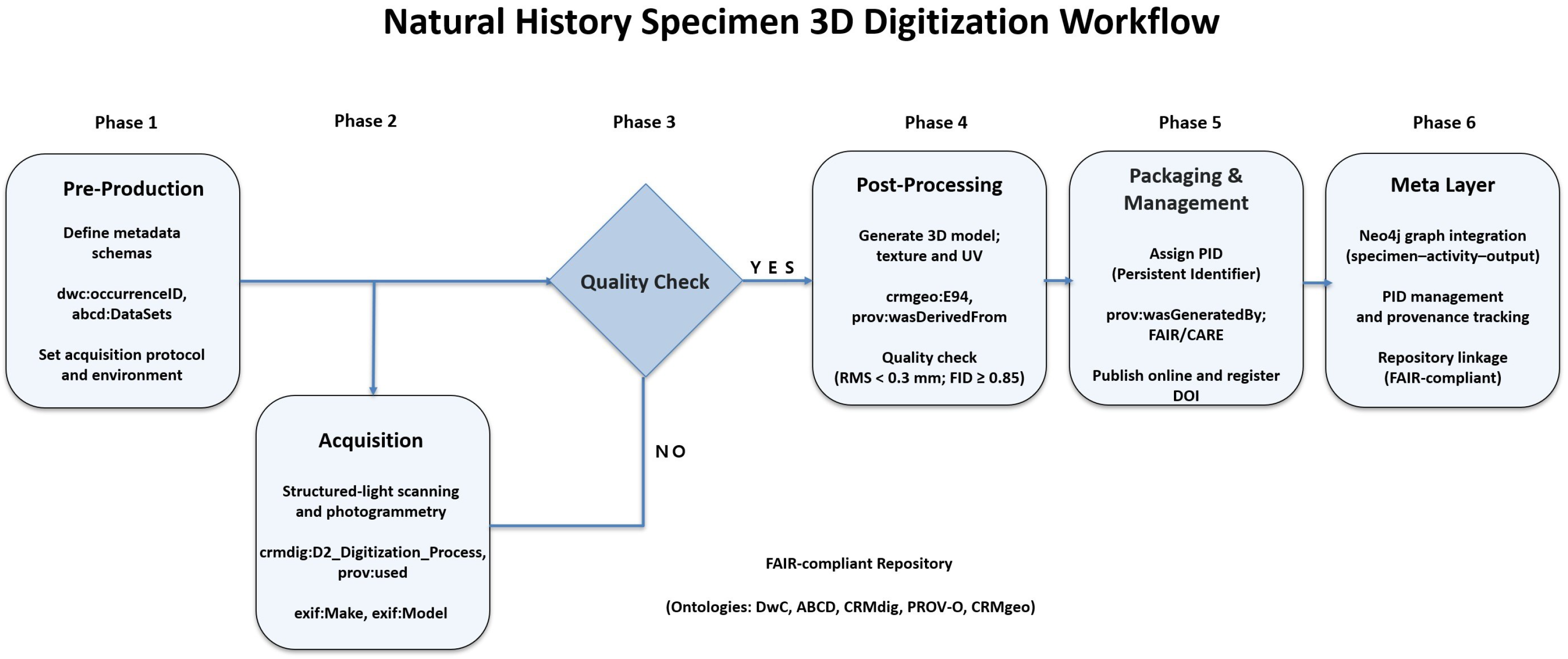

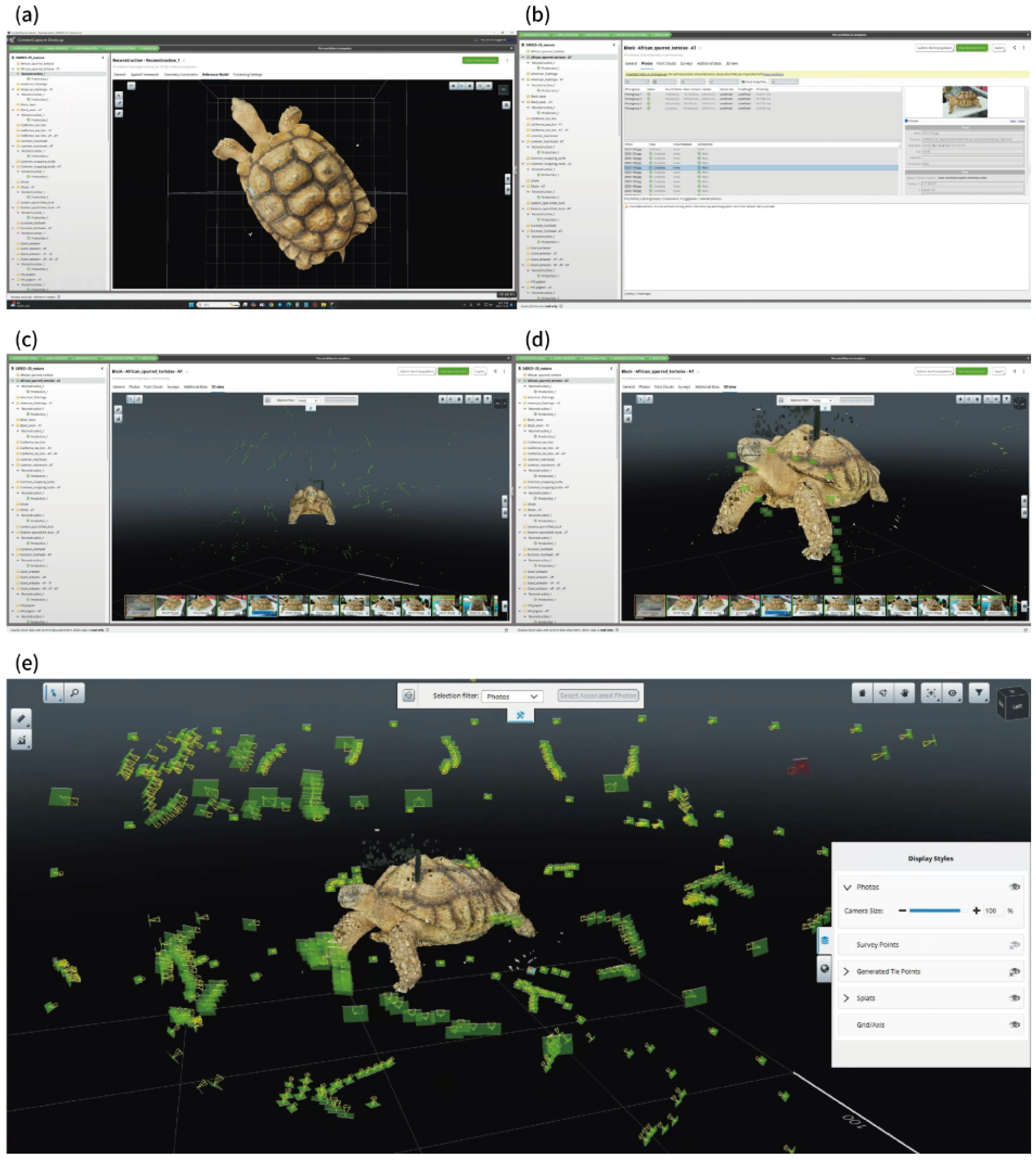

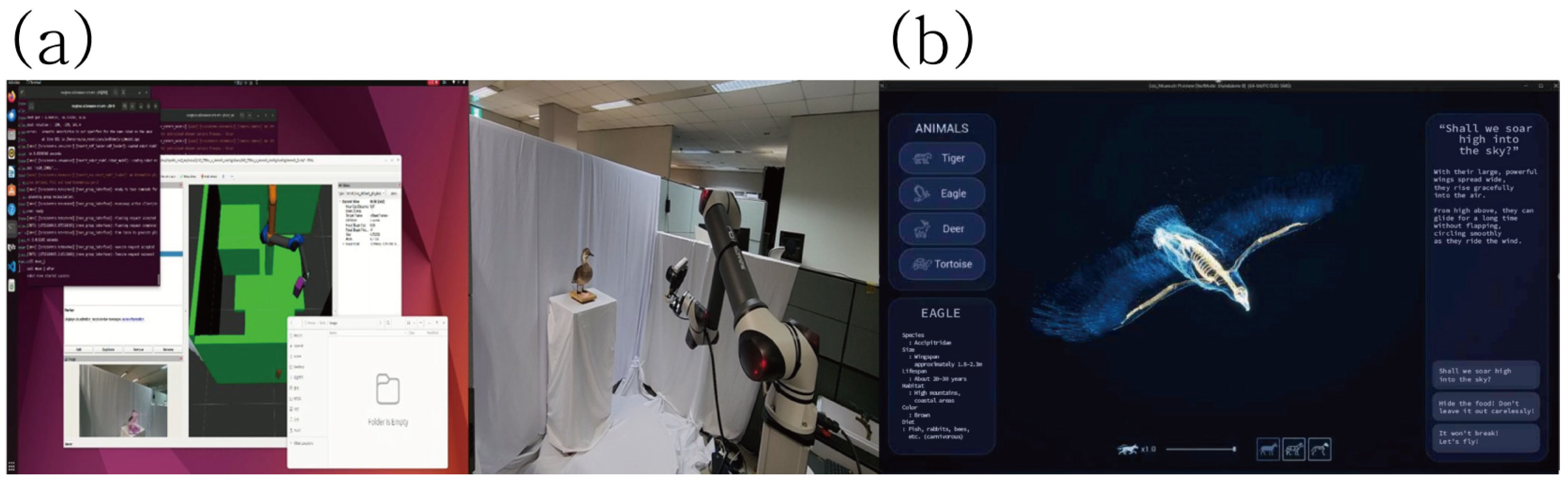

4. Higher-Reality 3D Digitization Workflow for Natural Heritage

4.1. Digitization Workflow and Quality Management

4.2. Paradata Documentation and Integration

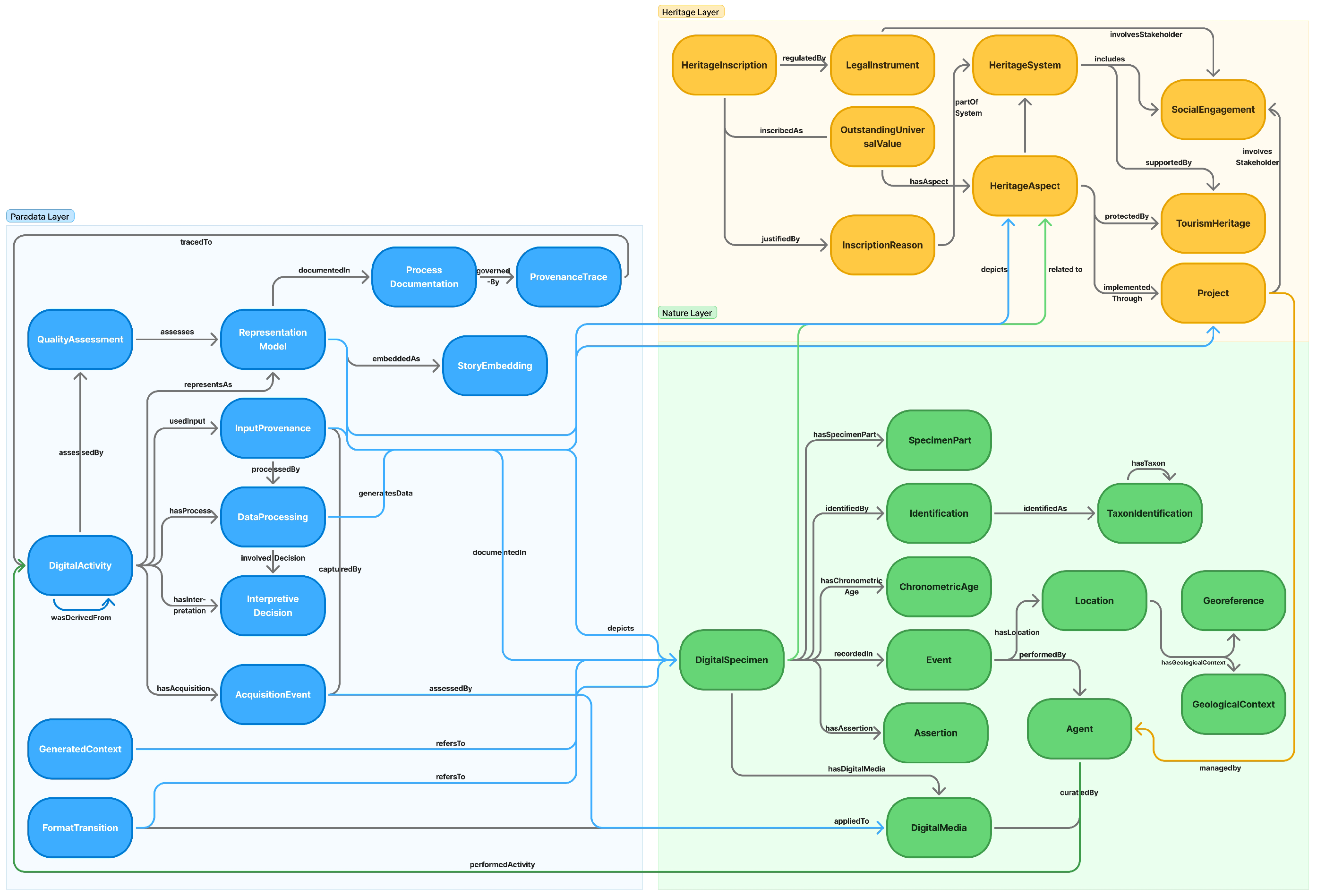

5. Extended Digital Natural Heritage Ontology

5.1. Purpose of the Ontology Structure

5.2. Design Principles

5.3. Structural Principles of Modularization

5.4. Nature Module (Nature and Digital Specimen)

5.4.1. Definitions of Core Classes in Nature Module

5.4.2. Object Properties in Nature Module

5.5. Heritage Module

5.5.1. Definitions of Core Classes in Heritage Module

5.5.2. Object Properties in Heritage Module

5.6. Digital Module

5.6.1. Definitions of Core Classes

5.6.2. Object Properties in Digital Module

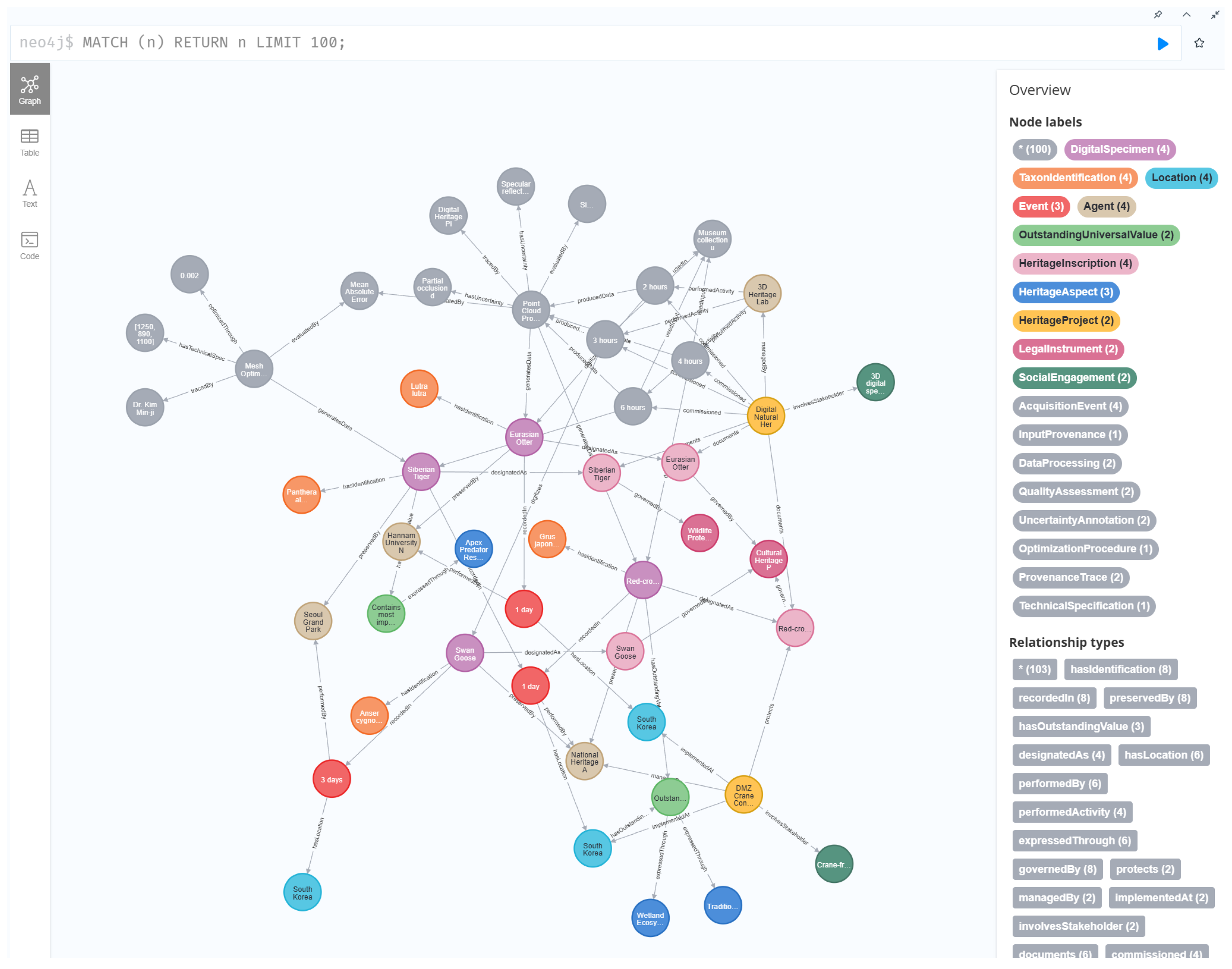

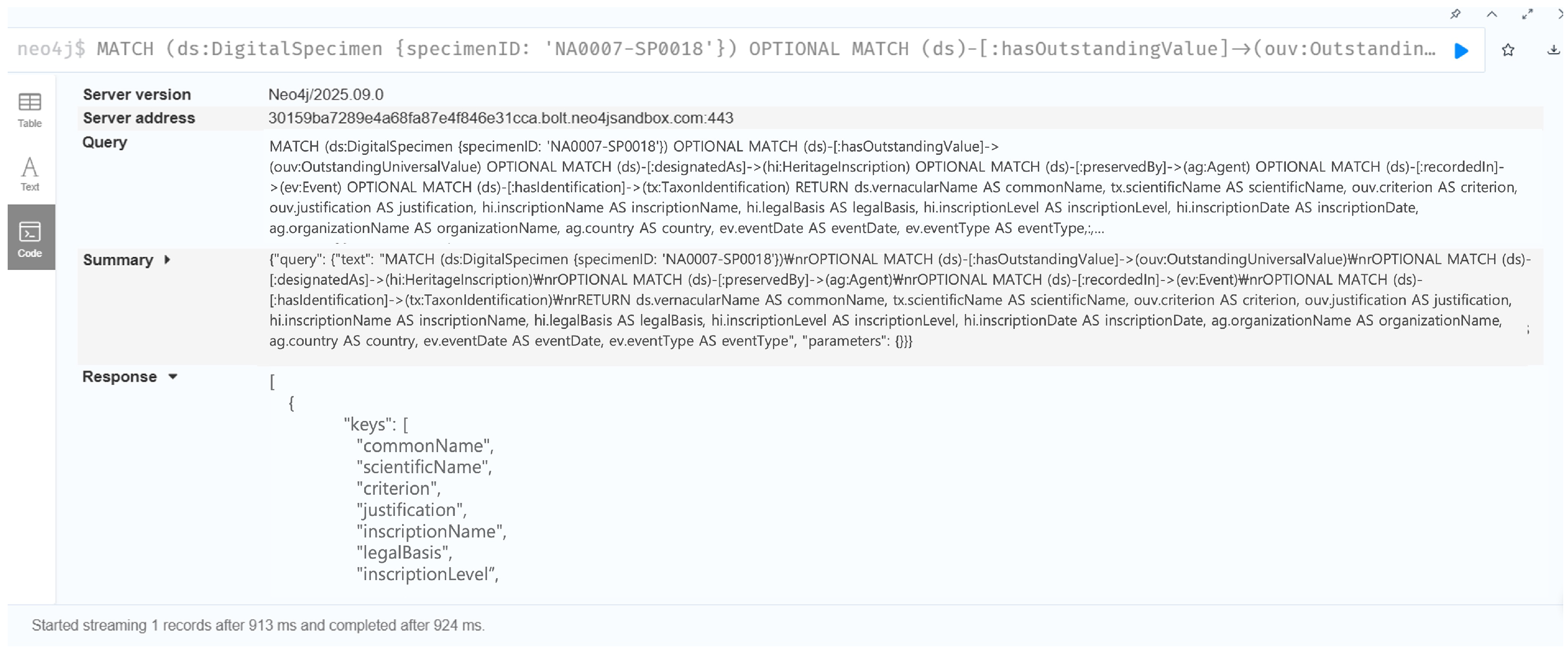

5.7. Ontology-Based Knowledge Graph Implementation

6. Semantic Collaborative Environment for Natural Heritage

6.1. System Architecture Overview

6.2. Core Technological Components

7. Performance Evaluation and Validation

7.1. Validation of Cross-Domain Reasoning Capabilities

7.1.1. Case 1: Causal Relationship Between Heritage Value and Digitization Quality

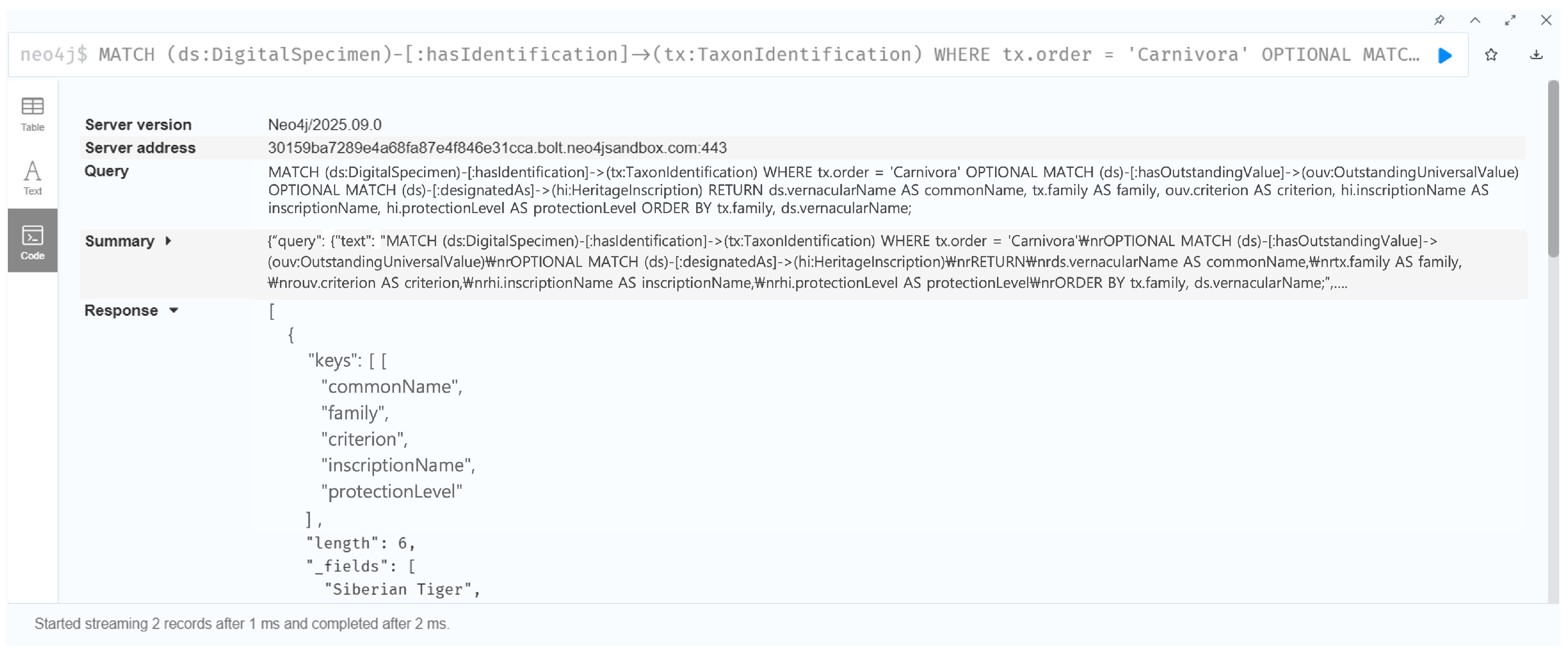

7.1.2. Case 2: Taxonomic Influence on Heritage Interpretation Patterns

7.1.3. Case 3: Multi-Criteria Prioritization in Digitization Workflows

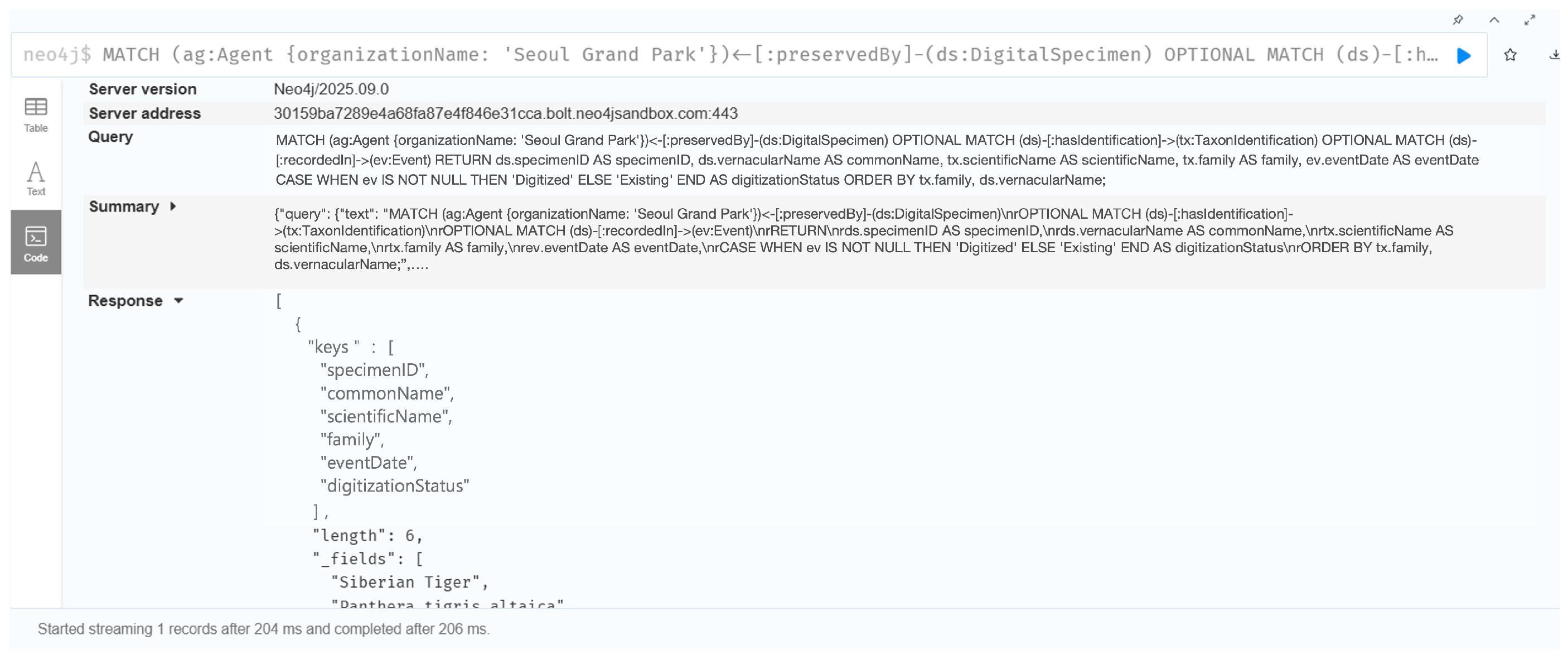

7.1.4. Case 4: Project-Based Quality Assessment and Accountability

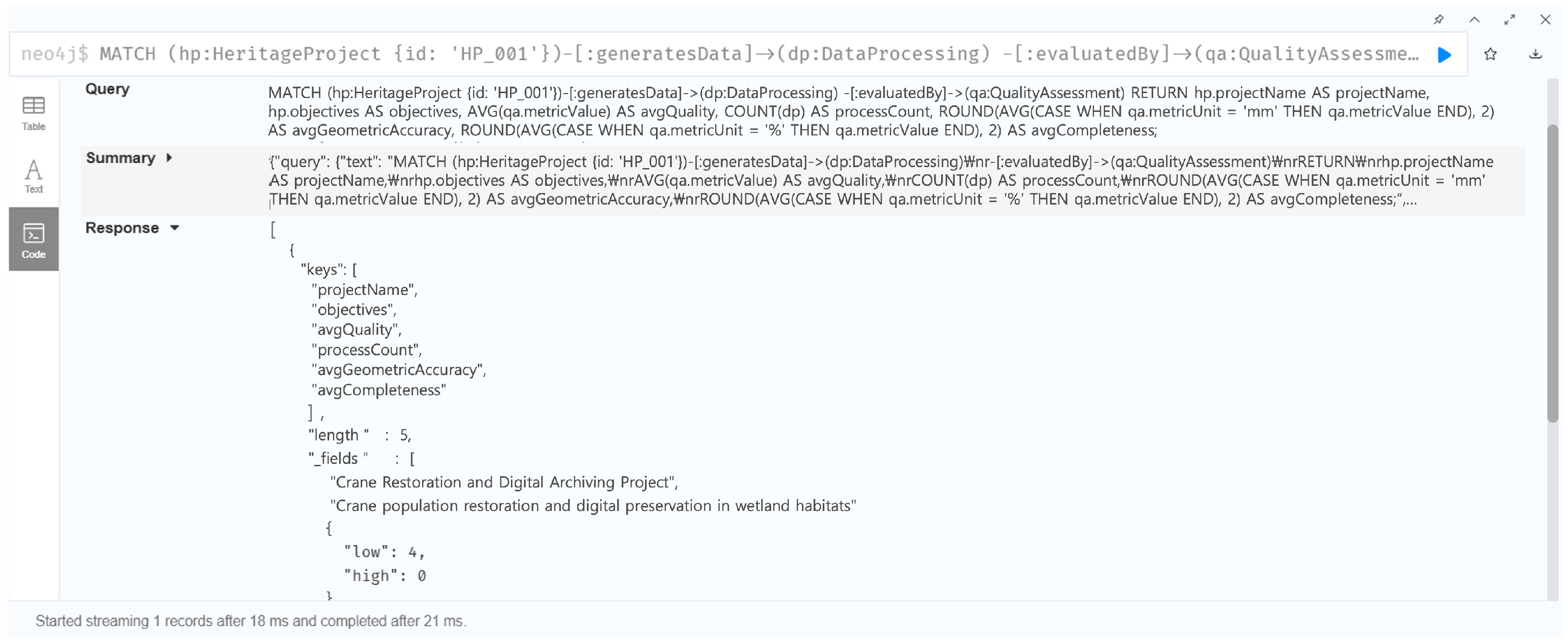

7.2. FAIR Data Maturity Evaluation

8. Discussion

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| E-DNH | Extended Digital Natural Heritage |

| C-EDNH | Collaborative Extended Digital Natural Heritage Platform |

| HR3D | Higher Reality 3D Digitalize |

| DES | Digital Extended Specimen |

| DwC | Darwin Core |

| ABCD | Access to Biological Collection Data |

| CIDOC-CRM | Conceptual Reference Model (CIDOC) |

| CRMdig | CIDOC-CRM extension for digitization |

| PROV-O | Provenance Ontology (W3C) |

| PID | Persistent Identifier |

| NSId | Natural Specimen Identifier |

| QA/QC | Quality Assurance and Quality Control |

| SfM | Structure from Motion |

| MVS | Multi-View Stereo |

| ICP | Iterative Closest Point |

References

- UNESCO. Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization: Paris, France, 1972; Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/conventiontext/ (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre. World Heritage List Statistics; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization: Paris, France, 2025; Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/stat/ (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Hedrick, B.P.; Hetherington, A.; Lowe, A.J.; Meineke, E.K.; Romero, C.J.; Sterner, B.; Stigall, A.; Thompson, J.C.; Wills, D. Digitization and the Future of Natural History Collections. BioScience 2020, 70, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, S.-Q.; Jalaluddin, N.S.M.; Yong, K.T.; Ong, S.P.; Lim, K.F.; Azhar, S. Digitization of natural history collections: A guideline and nationwide capacity-building workshop in Malaysia. Ecol. Evol. 2023, 13, e10212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brecko, J.; Mathys, A. Handbook of best practice and standards for 2D+ and 3D imaging of natural history collections. Eur. J. Taxon. 2020, 623, 1–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barzaghi, S.; Bordignon, A.; Zinck Lauersen, D.; Heller, B.; Giagnolini, M.; Renda, G.; Peroni, S.; Schirinzi, M.; Passarelli, M.; Fiorini, P. A proposal for a FAIR management of 3D data in cultural heritage: The Aldrovandi Digital Twin case. Data Intell. 2024, 6, 1190–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scopigno, R.; Callieri, M.; Cignoni, P.; Corsini, M.; Dellepiane, M.; Ponchio, F.; Ranzuglia, G. 3D models for cultural heritage: Beyond plain visualization. Computer 2011, 44, 48–55. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, J.; Yu, J. USD-based 3D archiving framework for time-series digital documentation of natural heritage. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2025, XLVIII-M-9-2025, 1097–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardisty, A.R.; Ellwood, E.R.; Nelson, G.; Zimkus, B.; Buschbom, J.; Addink, W.; Rabeler, R.K.; Bates, J.; Bentley, A.; Fortes, J.A.; et al. Digital Extended Specimens: Enabling an Extensible Network of Biodiversity Data Records as Integrated Digital Objects on the Internet. BioScience 2022, 72, 978–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meineke, E.K.; Davis, C.C.; Davies, T.J. The unrealized potential of herbaria for global change biology. Ecol. Monogr. 2018, 88, 505–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, M.D.; Dumontier, M.; Aalbersberg, I.J.; Appleton, G.; Axton, M.; Baak, A.; Blomberg, N.; Boiten, J.-W.; da Silva Santos, L.B.; Bourne, P.E.; et al. The FAIR Guiding Principles for Scientific Data Management and Stewardship. Sci. Data 2016, 3, 160018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckner, J.C.; Sanders, R.C.; Faircloth, B.C.; Chakrabarty, P. The critical importance of vouchers in genomics. eLife 2021, 10, e68264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SYNTHESYS3 Consortium. Final Publishable Summary Report (Grant Agreement No. 312253); European Commission Horizon 2020 Programme; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2017; Available online: https://cordis.europa.eu/docs/results/312/312253/final1-synthesys3-final-publishable-summary.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Bentkowska-Kafel, A.; Denard, H.; Baker, D. (Eds.) Paradata and Transparency in Virtual Heritage; Ashgate Publishing: Surrey, UK, 2012; ISBN 978-0754675839. [Google Scholar]

- Huvila, I. The Unbearable Complexity of Documenting Intellectual Processes: Paradata and Virtual Cultural Heritage Visualisation. Hum. IT 2012, 12, 97–110. Available online: https://humanit.hb.se/article/view/96 (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Cassar, A.; Baker, D.; Ioannides, M. From Digital Twin to Memory Twin: A Holistic Framework for Cultural Heritage Documentation, Interpretation, and Adaptive Reuse. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2025, XLVIII-M-9-2025, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldman, D. The CIDOC Conceptual Reference Model (CIDOC-CRM): Primer; CRM Labs: Pune, India, 2014; Available online: https://cidoc-crm.org/Resources/the-cidoc-conceptual-reference-model-cidoc-crm-primer (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Catalano, C.E.; Vassallo, V.; Hermon, S.; Spagnuolo, M. Representing quantitative documentation of 3D cultural heritage artefacts with CIDOC CRMdig. Int. J. Digit. Libr. 2020, 21, 251–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Missier, P.; Belhajjame, K.; Cheney, J. The W3C PROV family of specifications for modelling provenance metadata. In Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Extending Database Technology, Genoa, Italy, 18–22 March 2013; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 773–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinaldo, C.; Rielinger, D.; Deveer, J.; Castronovo, D. Connecting Libraries, Archives, and Museums: Collections in Support of Natural History Science. J. Comput. Cult. Herit. 2021, 16, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Egmond, E.; Willemse, L.; Runnel, V.; Saarenmaa, H.; Koivunen, A.; Lahti, K.; Livermore, L. Prioritising Needs for Data of Private Natural History Collections (ICEDIG Deliverable D2.2); Zenodo: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; Available online: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.2582995 (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Nelson, G.; Ellis, S. The History and Impact of Digitization and Digital Data Mobilization on Biodiversity Research. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 2018, 374, 20170391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, T.; Wieczorek, J.R.; Raymond, M. Diversifying the GBIF Data Model. Biodivers. Inf. Sci. Stand. 2022, 6, e94420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltis, P.S.; Nelson, G.; Fortes, J. iDigBio: Integrated Digitized Biodiversity Collections; Florida Museum of Natural History, University of Florida: Gainesville, FL, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Cicero, C.; Koo, M.S.; Braker, E.; Abbott, J.; Bloom, D.; Campbell, M.; Cook, J.A.; Demboski, J.R.; Doll, A.C.; Frederick, L.M.; et al. Arctos: Community-driven Innovations for Managing Natural and Cultural History Collections. PLOS ONE 2024, 19, e0296478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieczorek, J.; Bloom, D.; Guralnick, R.; Blum, S.; Döring, M.; Giovanni, R.; Robertson, T.; Vieglais, D. Darwin Core: An Evolving Community-Developed Biodiversity Data Standard. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e29715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depraetere, M.; Akhlaq, S.; Díaz, V.D.; Schwarz, D.; Haendel, J. Virtual Access to Fossil & Archival Material from the German Tendaguru Expedition (1909–1913): More Than 100 Years of Data–Meta–Paradata Management for Improved Standardisation. In 3D Research Challenges in Cultural Heritage V; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 119–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orzechowski, M.; Opioła, Ł; Martínez, I.L.; Ioannides, M.; Panayiotou, P.N.; Wróblewska, A. Integrated Data, Metadata, and Paradata Management System for 3D Digital Cultural Heritage Objects: Workflow Automation, Federated Authentication, and Publication. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2026, 174, 107964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vollmar, A.; Macklin, J.A.; Ford, L.S. Natural history specimen digitization: Challenges and concerns. Biodivers. Inform. 2010, 7, 93–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 14721:2012; Space Data and Information Transfer Systems — Open Archival Information System (OAIS) — Reference Model. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012.

- Ioannides, M.; Patias, P. The complexity and quality in 3D digitisation of the past: Challenges and risks. In Digital Heritage III: Complexity and Quality in Digitisation; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäfer, U.U. Uncertainty Visualization and Digital 3D Modeling. Int. J. Digit. Art Hist. 2019, 3, 87–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez-Figueroa, M.C.; Gómez-Pérez, A.; Fernández-López, M. The NeOn Methodology framework: A scenario-based methodology for ontology development. Appl. Ontol. 2015, 10, 107–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groom, Q.; Dillen, M.; Hardy, H.; Phillips, S.; Willemse, L.; Wu, Z. Improved standardization of transcribed digital specimen data. Database 2019, 2019, baz129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, R.A.; Barve, V.; Carausu, M.; Chavan, V.; Cuadra, J.; Freel, C.; Hagedorn, G.; Leary, P.; Mozzherin, D.; Olson, A.; et al. Discovery and publishing of primary biodiversity data associated with multimedia resources: The Audubon Core strategies and approaches. Biodivers. Inform. 2013, 8, 185–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitzalis, D.; Niccolucci, F.; Cord, M. Using LIDO to handle 3D cultural heritage documentation data provenance. In Proceedings of the 2011 International Workshop on Content-Based Multimedia Indexing (CBMI), Madrid, Spain, 13–15 June 2011; pp. 520–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Platform | Core Strategy | Limitation |

|---|---|---|

| Arctos | • Community-driven governance (400+ institutions) • Entity-based relational model with flexible many-to-many linking • Darwin Core integration with PID-based interoperability | • Lacks ontology-based semantic structure for 3D object attributes (mesh resolution, texture versioning) • Limited paradata integration for digitization workflows |

| GBIF | • Global federation model (180+ countries) • Occurrence-centric data model with Darwin Core standardization • Distributed publishing via IPT | • Text-based occurrence records; limited support for 3D, paradata, and non-taxonomic contexts • Expert-centric interface limits broader user engagement |

| iDigBio | • Cloud-based centralized hub with federated storage • Thematic Collections Networks for taxonomic collaboration • RESTful API and RDF-based media linking | • Darwin Core dependency; lacks structured paradata for digitization provenance • Metadata-centric approach insufficient for 3D data lifecycle management |

| Taxonomic Group | Specimens (n) | Percentage | Institutions | Major Taxa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aves (Birds) | 135 | 68.5% | NMCNMK (95), SGP (40) | Cranes, eagles, owls, herons, etc. |

| Insecta (Insects) | 49 | 24.9% | HNU (49) | Beetles, mantises, grasshoppers, etc. |

| Mammalia (Mammals) | 10 | 5.1% | NMCNMK (7), SGP (3) | Tiger, otter, bear, goral, etc. |

| Reptilia (Reptiles) | 3 | 1.5% | SGP (2), NMCNMK (1) | Tortoises, turtles, etc. |

| Total | 197 | 100% | 3 institutions | ca. 140 species |

| Data Type | Characteristics | Application |

|---|---|---|

| Specimen Attributes | • Taxonomic & biological data • Collection metadata • Preservation state • Persistent identifiers (PIDs) | • Taxonomic classification • Specimen instances • Linking physical specimens to digital surrogates |

| Project Information | • Digitization activity records • Workflows & equipment parameters • Institutional collaboration metadata • Conservation & restoration records | • Documentation of digitization events • Paradata modeling via CRMdig • Activity attribution with PROV-O |

| Heritage Records | • Unstructured text formats • Historical documents • Public reports like evaluation • Cultural and ecological narratives | • Integration of cultural significance • Heritage enrichment • Semantic annotation of narratives |

| Category | Equipment | Key Specifications | Application Stage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structured-light Scanner | Artec Space Spider (Artec 3D, Luxembourg City, Luxembourg) | 0.05 mm point accuracy, 16 fps | Close-range geometry capture |

| DSLR Camera | Sony 7R V (Sony Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) | 61 MP, 35 mm f/1.4, ISO 100 | Texture acquisition |

| Turntable System | RB10-1300 (Rotary Systems, Seoul, South Korea) | 360° rotation, 5° interval, 48 positions | Automated rotational scanning |

| Lighting | Diffuse LED Panel (Manufacturer name, City, Country) | 1000–1500 lux, 5500 K, CRI > 95 | Uniform illumination environment |

| Category | Key Elements | Analytical Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Physical Context | Scanning environment (illumination, humidity), specimen mounting, device resolution, scanning angles | Reproducibility and scientific credibility through controlled acquisition conditions |

| Computational Context | Alignment algorithms, texture mapping parameters, reconstruction workflows | Transparency and traceability of computational transformations |

| Interpretive Context | AI model selection, manual editing, quality thresholds, validation criteria | Accountability and interpretive transparency in human judgment |

| 3D Digitization Task | Type of Paradata | Ontology Class |

|---|---|---|

| Input condition setting | Equipment selection, specimen complexity analysis | InputProvenance |

| Acquisition control | Environmental conditions, image overlap ratio | AcquisitionEvent |

| Algorithm parameters | Registration threshold, feature extraction method | DataProcessing |

| Interpretive decisions | AI model selection, reconstruction scope | InterpretiveDecision |

| Reliability expression | Confidence scores, extent of data loss | UncertaintyAnnotation |

| Quality assessment | Geometric accuracy, color fidelity | QualityAssessment |

| Optimization strategy | Polygon reduction, texture compression | OptimizationProcedure |

| Class | Definition and Functional Role |

|---|---|

| DigitalSpecimen | Represents the digital surrogate of a physical natural specimen, characterized by persistent identifiers, specimen type, and holding institution. Extends the Darwin Core Occurrence class to establish a curated digital representation linked to the physical specimen within museum collections, supporting the Digital Extended Specimen (DES) paradigm. |

| Event | Records the spatiotemporal context of specimen collection, observation, or documentation activities. Captures the precise moment when the specimen was documented within a scientific framework, serving as essential provenance information for assessing specimen origin, collection methodology, and data reliability. |

| Location | Defines the geographic context in which the specimen was discovered or observed. Incorporates hierarchical spatial data including coordinates, administrative divisions, place names, elevation, and depth, supporting ecological distribution analysis, biogeographic research, and heritage site boundary delineation. |

| Identification | Documents the taxonomic determination process and outcomes for a specimen. Explicitly records the taxonomist, determination date, identification method, and confidence level, enabling historical traceability and re-evaluation of taxonomic decisions as systematic knowledge evolves. |

| DigitalMedia | Describes multimedia representations of specimens—including photographs, videos, 3D models, and audio recordings—structured according to Audubon Core metadata standards. Includes technical attributes such as file format, resolution, color space, authorship, and capture conditions, ensuring standardized management and interoperability of digital assets. |

| Agent | Represents individuals or organizations participating in specimen-related activities, including collectors, taxonomists, curators, digitization technicians, and researchers. Documents roles, contributions, and institutional affiliations to support scientific accountability, provenance transparency, and scholarly citation throughout the specimen lifecycle. |

| Property Name | Description | Example | Linked Standard |

|---|---|---|---|

| recordedIn | Links specimen to collection event | Beetle → Field collection May 2023 | Darwin Core Event |

| hasLocation | Connects event to location | Event → Jeju Province (33.4569° N) | Darwin Core Location |

| identifiedBy | Links specimen to identification | Butterfly → Identified by Dr. Kim 2024 | Darwin Core Identification |

| hasDigitalMedia | Links specimen to media | Specimen → lateral.jpg (6000 × 4000 px) | Audubon Core |

| performedBy | Links activity to agent | Collection → NIBR Survey Team | Darwin Core Agent |

| curatedBy | Links specimen to institution | Specimen → National Science Museum | Darwin Core Agent |

| Class | Definition and Functional Role |

|---|---|

| OutstandingUniversalValue | Represents UNESCO World Heritage inscription criteria (vii–x), structuring attributes for geological processes, ecosystems, biodiversity, and esthetic value. Enables systematic assessment of heritage significance through quantifiable criteria (e.g., Jeju Volcanic Island’s geological diversity, DMZ biodiversity corridor), supporting conservation prioritization reasoning. |

| HeritageInscription | Records administrative and legal designation procedures across multi-layered protection systems (World Heritage, national monuments, provincial heritage). Tracks chronological stages (e.g., Jeju designation 2007), enabling historical traceability and comparative analysis of protection frameworks. |

| HeritageAspect | Decomposes multidimensional heritage values into separate evaluable attributes (biological diversity, geological importance, ecological processes, cultural landscape, scientific research value). Supports aspect-specific conservation strategies and enables reasoning across heritage value dimensions. |

| HeritageProject | Represents organized conservation, restoration, or sustainable use activities (e.g., wetland rehabilitation, invasive species removal, environmental monitoring). Links to Agent and Event classes to document stakeholders, timelines, and outcomes, enabling systematic evaluation of management effectiveness. |

| LegalInstrument | Describes legal, regulatory, and policy frameworks governing heritage protection (international conventions, national laws, ordinances, management guidelines). Specifies scope, enforceability, and jurisdictional hierarchy, supporting compliance analysis and conflict resolution in multi-jurisdictional sites. |

| SocialEngagement | Models participation of local communities, indigenous groups, and stakeholders, operationalizing CARE principles. Documents collaborative governance, traditional ecological knowledge integration, and consultation processes, enabling analysis of stakeholder participation patterns and diverse knowledge systems. |

| Property Name | Description | Example | Linked Standard |

|---|---|---|---|

| hasOutstandingValue | Links site to OUV | Jeju Volcanic Island → Criterion viii | CIDOC-CRM E18 |

| inscribedAs | Connects value to inscription | OUV → UNESCO World Heritage 2007 | LIDO recordWrap |

| hasAspect | Links value to aspect | Hallasan → Alpine vegetation aspect | LIDO objectWorkType |

| implementedThrough | Links value to project | Biodiversity → Restoration Project 2020–2025 | CIDOC-CRM E7 |

| regulatedBy | Connects to legal instrument | Designation → Cultural Heritage Act Art. 25 | CIDOC-CRM E73 |

| involvesStakeholder | Links project to stakeholders | Restoration → Jeju community council | CIDOC-CRM E39 |

| Class | Definition and Functional Role |

|---|---|

| InputProvenance | Traces origins and generation context of raw digitization data. Structures input factors affecting data quality (scanner model, sensor configuration, environmental conditions, specimen preparation state), enabling systematic analysis of how acquisition context influences output fidelity. |

| AcquisitionEvent | Records the precise moment when digital data are captured from physical specimens. Specifies technical parameters (scan resolution, point-cloud density, capture angles, session duration), supporting reproducibility analysis and parameter optimization through correlation with quality outcomes. |

| DataProcessing | Documents computational procedures transforming raw data into 3D models. Records processing steps (point-cloud registration, mesh generation, noise reduction, hole filling) with algorithms, parameters, and software versions, enabling verification of processing decisions and replication of workflows. |

| QualityAssessment | Measures how faithfully digital outputs reproduce original specimen geometry, color, and texture. Performs quantitative evaluations based on Eureka3D quality indicators (geometric accuracy, color fidelity, texture clarity), enabling objective comparison across digitization methods and identification of quality thresholds. |

| UncertaintyAnnotation | Explicitly records confidence limits arising during digital reconstruction. Visually and semantically distinguishes reconstructed or AI-generated components (inferred surfaces, estimated colors, synthetic textures), quantifying uncertainty sources and degrees to support the critical interpretation of digital assets. |

| ProvenanceTrace | Establishes traceable networks, enabling backtracking from final digital objects to raw data and intermediate processing steps. Employs PROV-O properties wasDerivedFrom and wasGeneratedBy to construct complete genealogical chains, supporting authenticity verification and reproducibility validation. |

| Property Name | Description | Example | Linked Standard |

|---|---|---|---|

| usedInput | Links activity to input data | Alignment → Artec raw scan (0.1 mm) | PROV-O used |

| capturedBy | Connects data to acquisition | Raw images ← Robot scan May 2024 | CRMdig D2 |

| processedBy | Links data to processing | Point cloud → ICP registration | PROV-O wasGeneratedBy |

| assessedBy | Links output to QA | Fused model → RMS 0.23 mm | CRMdig D13 |

| annotatesUncertainty | Links model to uncertainty | Restoration area → AI 68% confidence | CRMdig D1 |

| tracedTo | Traces provenance chain | GLB ← Mesh ← Point Cloud ← Raw | PROV-O wasDerivedFrom |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, Y.; Seol, S.; Oh, J.; Lee, J. Semantic Collaborative Environment for Extended Digital Natural Heritage: Integrating Data, Metadata, and Paradata. Heritage 2025, 8, 507. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8120507

Lee Y, Seol S, Oh J, Lee J. Semantic Collaborative Environment for Extended Digital Natural Heritage: Integrating Data, Metadata, and Paradata. Heritage. 2025; 8(12):507. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8120507

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Yeeun, Songie Seol, Jisung Oh, and Jongwook Lee. 2025. "Semantic Collaborative Environment for Extended Digital Natural Heritage: Integrating Data, Metadata, and Paradata" Heritage 8, no. 12: 507. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8120507

APA StyleLee, Y., Seol, S., Oh, J., & Lee, J. (2025). Semantic Collaborative Environment for Extended Digital Natural Heritage: Integrating Data, Metadata, and Paradata. Heritage, 8(12), 507. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8120507