Ancestral Inca Construction Systems and Worldview at the Choquequirao Archaeological Site, Cusco, Peru, 2024

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. State of the Art

1.1.1. Theoretical Framework

Ushnu

Pacha

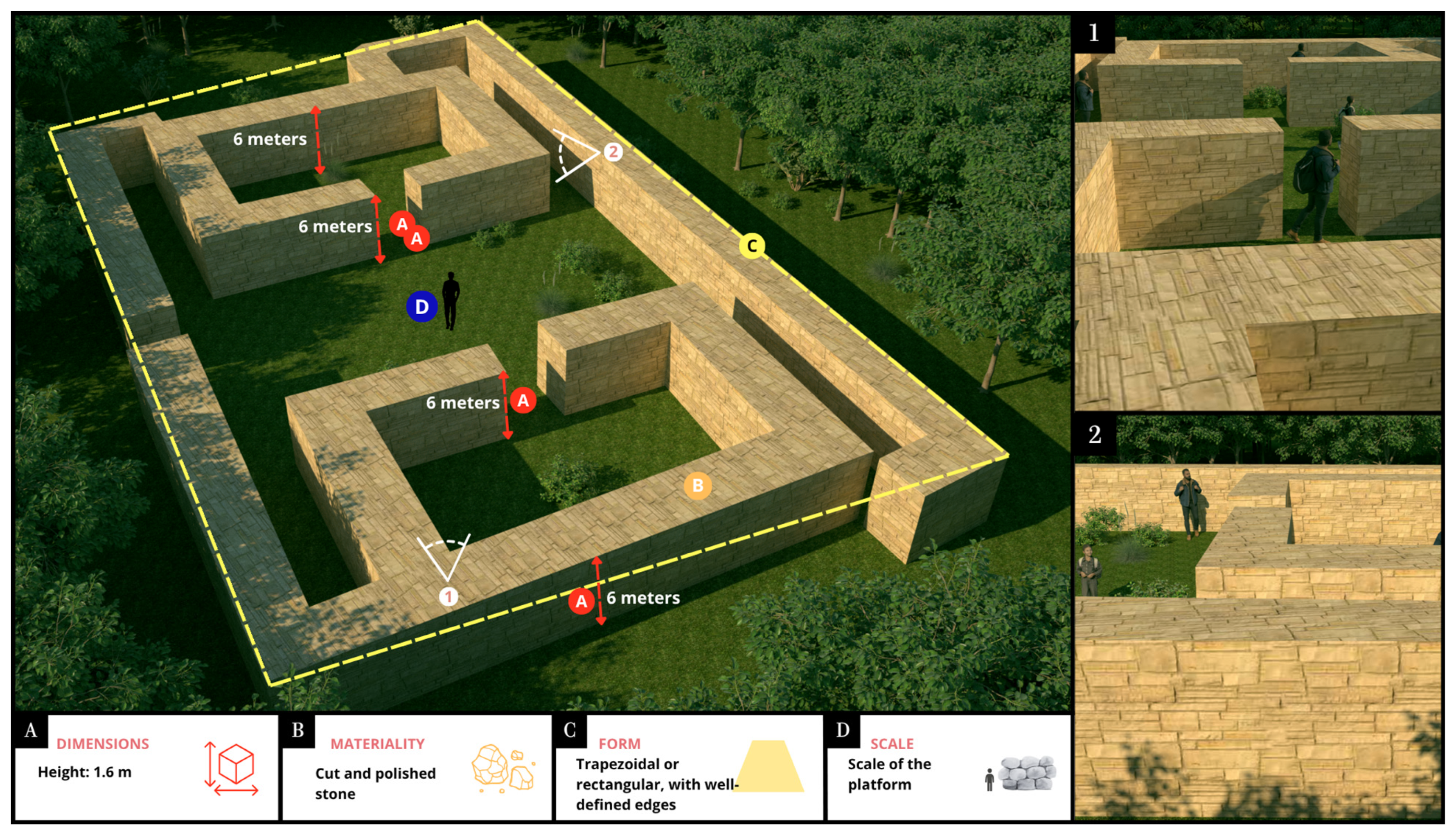

Kallanka

Qolqa

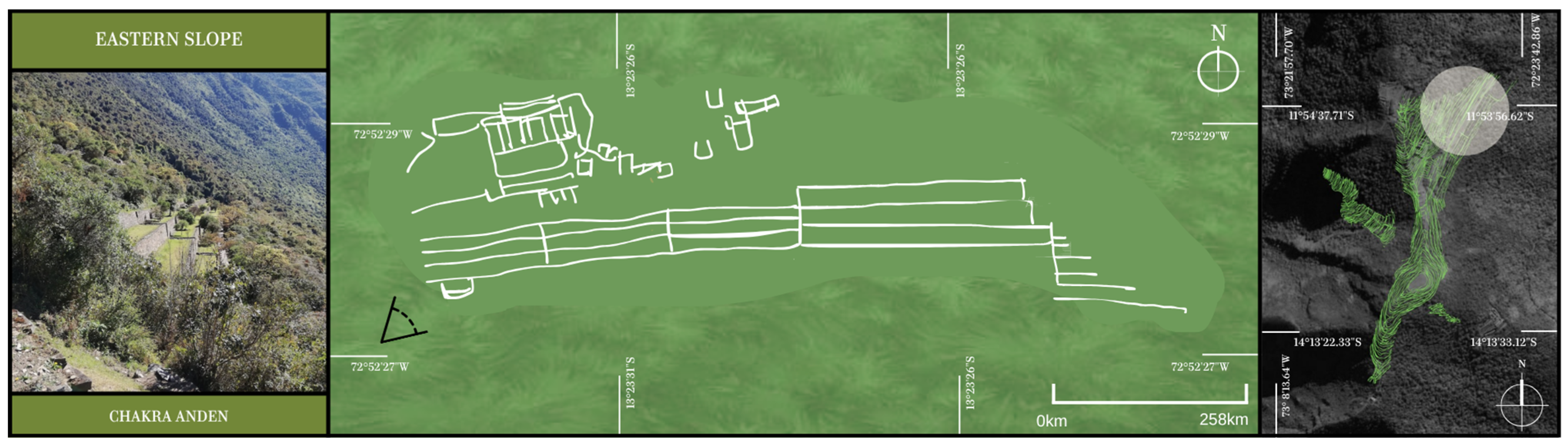

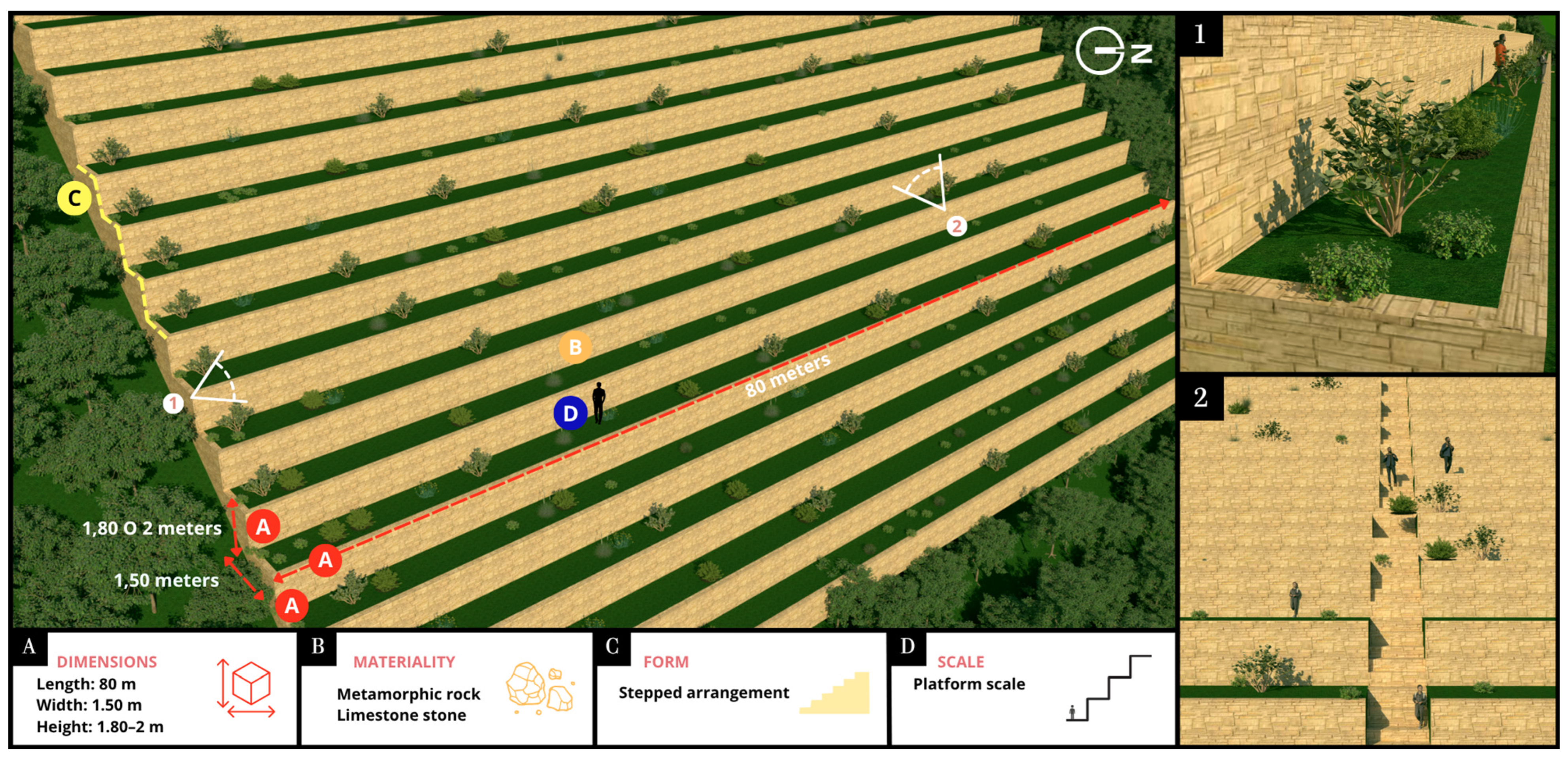

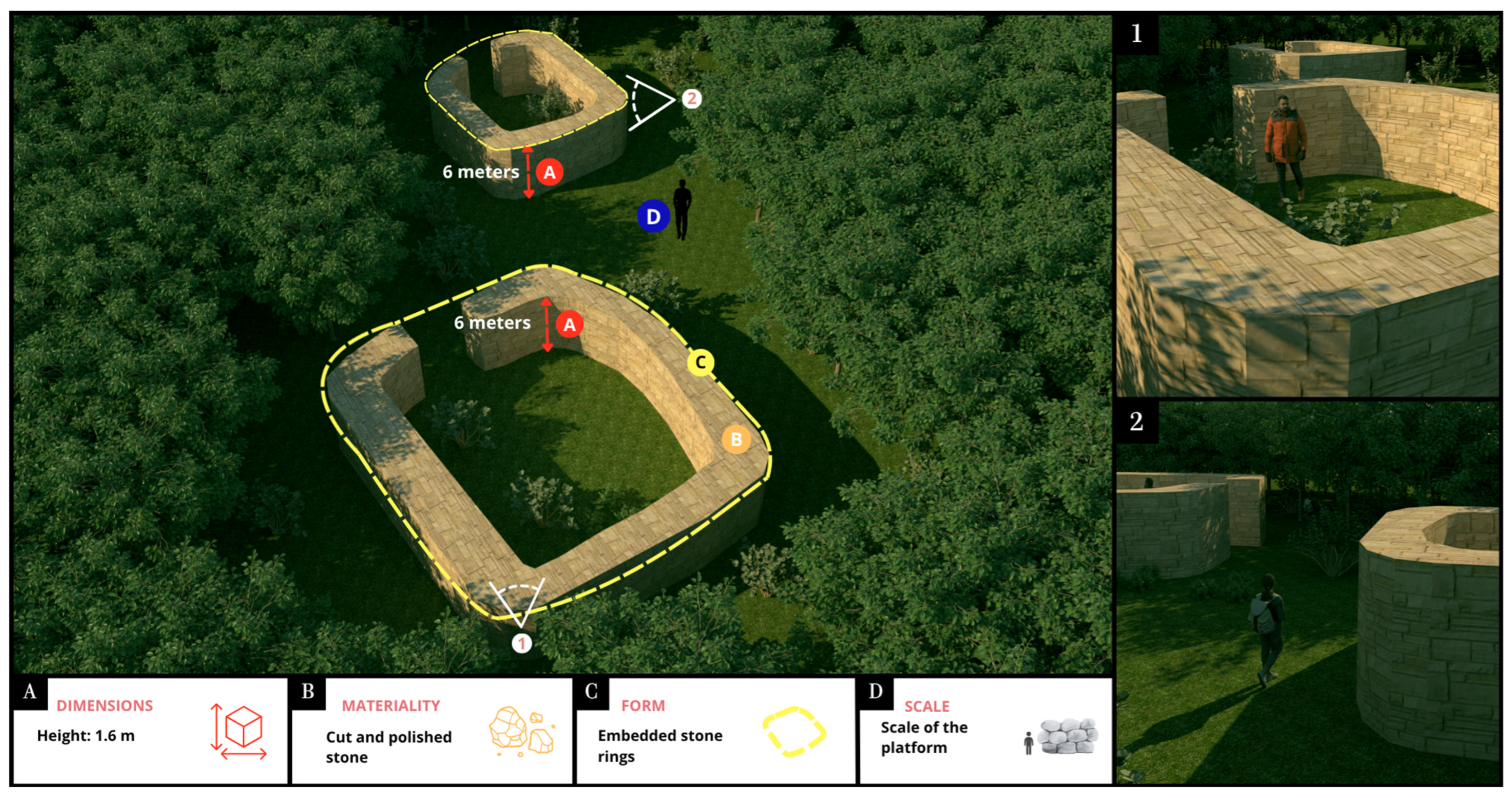

Chakra

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Methodological Framework

2.1.1. Literature Review

2.1.2. Site, Climate, Ecosystems, and Fauna Analysis

2.1.3. Discussion and Conclusions

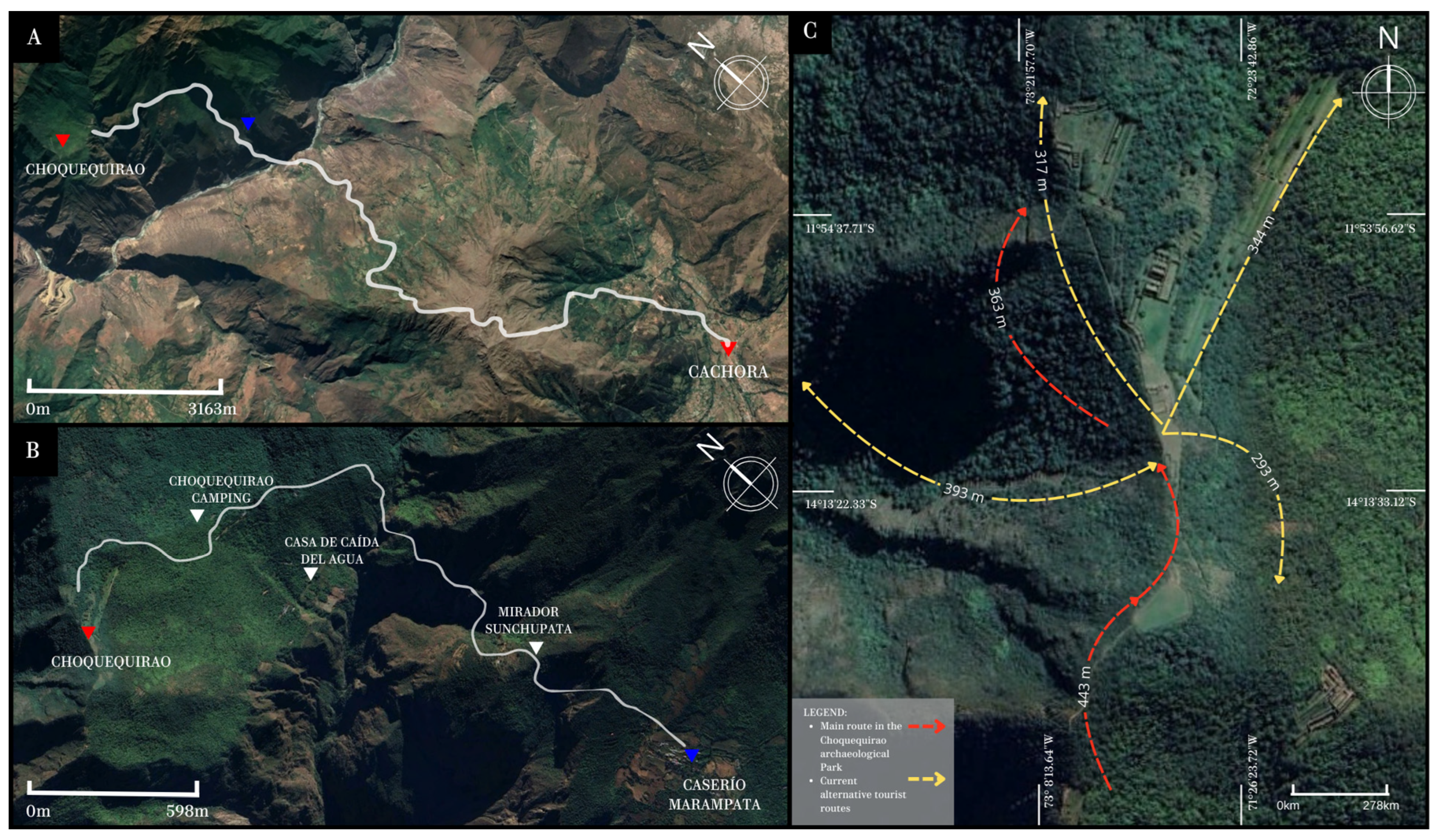

2.2. Study Area

2.3. Climatic Analysis

2.4. Ecosystems

2.5. Fauna y Flora

3. Results

3.1. Site of Intervention, Topography, and Solar Orientation

3.2. Subsection Spatial Analysis

Master Plan: Area and Dimension Analysis

3.3. Functional Analysis

3.3.1. Zoning, Analysis, and Spatial Distribution

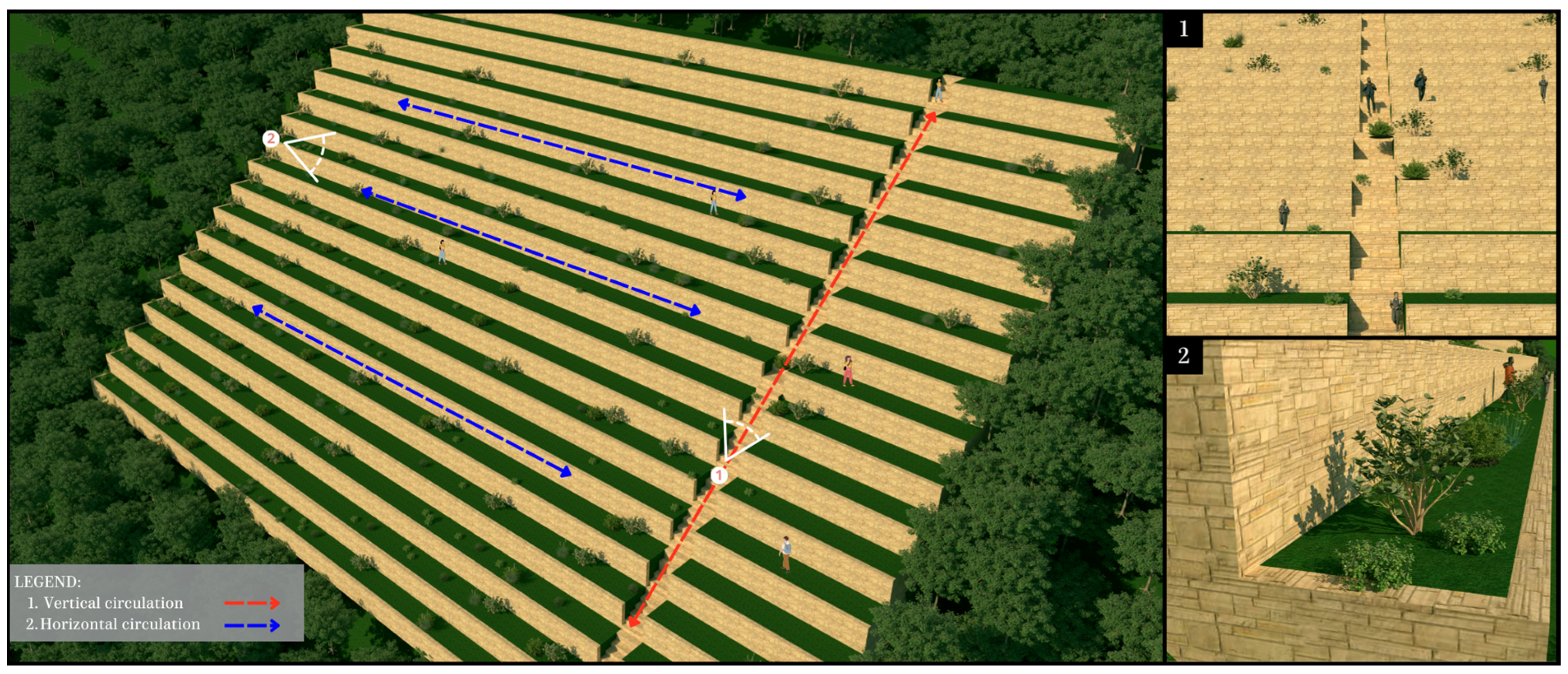

3.3.2. Circulation Pattern and Flow Control

3.4. Visual Harmony

3.4.1. Strategic Positioning, Repetition, and Rhythm

3.4.2. Structural Symbolism

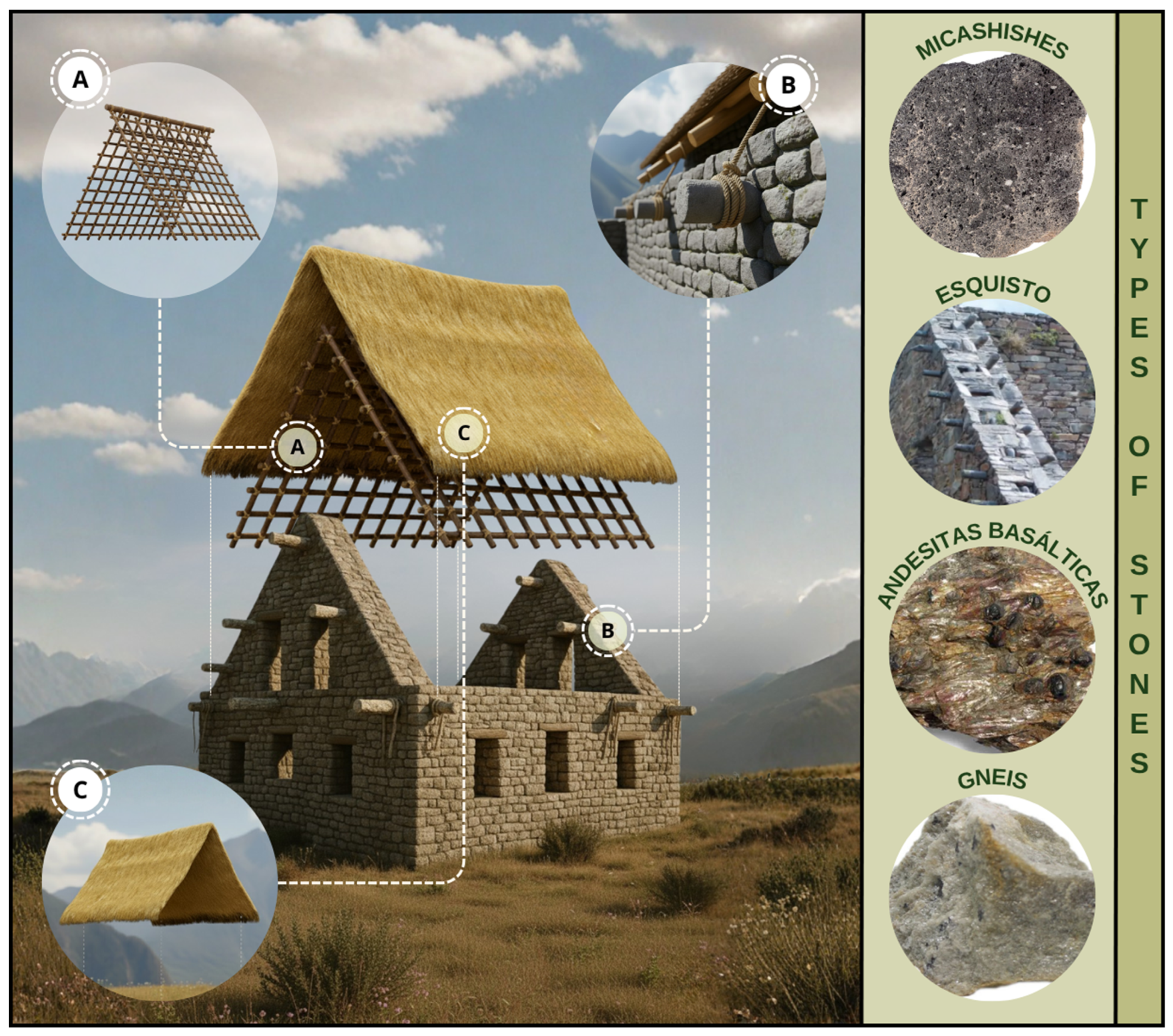

3.5. Inca Construction Analysis

3.5.1. Materiality

3.5.2. Dimensions and Construction Techniques

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Van Valkenburgh, P.; Chase, Z.; Traslaviña, A.; Weaver, B.J.M. Arqueología Histórica en el Perú: Posibilidades y Perspectivas: 2016. Available online: https://revistas.pucp.edu.pe/index.php/boletindearqueologia/article/view/18662 (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Zona Arqueológica Caral. ¿Cuál es la Importancia de la Arqueología en el Perú? Reflexionan Arqueólogos de Caral. Available online: https://www.zonacaral.gob.pe/cual-es-la-importancia-de-la-arqueologia-en-el-peru-reflexionan-arqueologos-de-caral/ (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Cordero, L.M.; Zúniga, A.C. Aproximación del Estado del Arte Sobre: Importancia del Valor Patrimonial de Sitios Arqueológicos. Available online: https://portal.amelica.org/ameli/journal/387/3873792006/html/ (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Rojano, M. Arqueología y Curiosidad en el ser Humano: La Protohistoria de la Disciplina Científica. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/journal/4980/498062141012/html/ (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Colmenares, D.M. La Importancia del Patrimonio Cultural. CEUPE: Madrid, Spain. Available online: https://www.ceupe.com/blog/importancia-del-patrimonio-cultural.html (accessed on 24 August 2024).

- Marín, D.; Buelvas, J.M.; Sarmiento, J.S.; Ricardo, J.C.; Correa, J.L.; Martínez, G.; Hernández, R.; Ghisays, G.; Díaz, J.; Guevara, O.; et al. Enfoques, Teorías y Perspectivas de la Arquitectura y sus Programas Académico; Osorio, G.M., Romero, M.C.A., Eds.; Corporación Universitaria del Caribe—CECAR: Sucre, Colombia, 2018; Available online: https://biblioteca-repositorio.clacso.edu.ar/bitstream/CLACSO/171259/1/Enfoques-arquitectura.pdf (accessed on 24 August 2024).

- EEA. Conservación y Restauración del Patrimonio Histórico Arquitectónico y Arqueológico; European Environment Agency: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2015; Available online: https://www.eea.csic.es/laac/investigacion-laac/conservacion-y-restauracion-del-patrimonio-historico-arquitectonico-y-arqueologico/ (accessed on 24 August 2024).

- Google Maps. Chaco Canyon National Historical Park. Available online: https://www.google.com/maps/place/Chaco+Canyon/@36.060732,-107.9656803,2a,90y,333.01h,88.05t/data=!3m7!1e1!3m5!1s42WukXP-oqKlGOwrifzBpA!2e0!6shttps:%2F%2Fstreetviewpixels-pa.googleapis.com%2Fv1%2Fthumbnail%3Fcb_client%3Dmaps_sv.tactile%26w%3D900%26h%3D600%26pitch%3D1.9532587324156054%26panoid%3D42WukXP-oqKlGOwrifzBpA%26yaw%3D333.00663250433075!7i13312!8i6656!4m7!3m6!1s0x873ca8da58ec928b:0xe9f1727039c6bed6!8m2!3d36.060293!4d-107.967008!10e5!16s%2Fg%2F1z449ybzt?entry=ttu&g_ep=EgoyMDI1MTExMS4wIKXMDSoASAFQAw%3D%3D (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Google Maps. Chichen Itza Archaeological Site. Available online: https://www.google.com/maps/place/Chich%C3%A9n+Itz%C3%A1/@20.6836627,-88.5683725,3a,62.1y,199.92h,95.76t/data=!3m7!1e1!3m5!1sWTxCaemNROTfhEP4JpXznw!2e0!6shttps:%2F%2Fstreetviewpixels-pa.googleapis.com%2Fv1%2Fthumbnail%3Fcb_client%3Dmaps_sv.tactile%26w%3D900%26h%3D600%26pitch%3D-5.760000000000005%26panoid%3DWTxCaemNROTfhEP4JpXznw%26yaw%3D199.92!7i13312!8i6656!4m7!3m6!1s0x8f5138c6e391c0e7:0x7c1ea0a168994d9a!8m2!3d20.6842849!4d-88.5677826!10e5!16zL20vMDE3a3B2?entry=ttu&g_ep=EgoyMDI1MTExMS4wIKXMDSoASAFQAw%3D%3D (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Google Maps. Tikal National Park. Available online: https://www.google.com/maps/place/Parque+Nacional+Tikal/@17.2220171,-89.6236539,2a,75y,296.78h,100.69t/data=!3m7!1e1!3m5!1sgVM__YVcWB1K922pvEMD4A!2e0!6shttps:%2F%2Fstreetviewpixels-pa.googleapis.com%2Fv1%2Fthumbnail%3Fcb_client%3Dmaps_sv.tactile%26w%3D900%26h%3D600%26pitch%3D-10.689999999999998%26panoid%3DgVM__YVcWB1K922pvEMD4A%26yaw%3D296.78!7i13312!8i6656!4m11!1m2!2m1!1sTikal!3m7!1s0x8f5fa6cb0262c673:0xdec9c33cf23e1155!8m2!3d17.2220409!4d-89.6236995!10e5!15sCgVUaWthbFoHIgV0aWthbJIBDW5hdGlvbmFsX3BhcmuqAS0QATIeEAEiGjlP6fvbYPOTT5gMUJL8nOwY_jACuWio56LEMgkQAiIFdGlrYWzgAQA!16zL20vMDE0aHd5?entry=ttu&g_ep=EgoyMDI1MTExMS4wIKXMDSoASAFQAw%3D%3D (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Google Maps. Stonehenge Prehistoric Monument. Available online: https://www.google.com/maps/place/Stonehenge/@51.178896,-1.8259956,3a,90y,289.19h,86.21t/data=!3m7!1e1!3m5!1syxYAPYFywKdx_6BIjAgt5Q!2e0!6shttps:%2F%2Fstreetviewpixels-pa.googleapis.com%2Fv1%2Fthumbnail%3Fcb_client%3Dmaps_sv.tactile%26w%3D900%26h%3D600%26pitch%3D3.7900000000000063%26panoid%3DyxYAPYFywKdx_6BIjAgt5Q%26yaw%3D289.19!7i13312!8i6656!4m7!3m6!1s0x4873e63b850af611:0x979170e2bcd3d2dd!8m2!3d51.178882!4d-1.826215!10e5!16zL20vMDZ3Zmc?entry=ttu&g_ep=EgoyMDI1MTExMS4wIKXMDSoASAFQAw%3D%3D (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Google Maps. Roman Colosseum. Available online: https://www.google.com/maps/place/Coliseo+de+Roma/@41.8891681,12.4921906,3a,75y,4.98h,90.55t/data=!3m7!1e1!3m5!1sDqEws0cUOihYSKbL6A4h_A!2e0!6shttps:%2F%2Fstreetviewpixels-pa.googleapis.com%2Fv1%2Fthumbnail%3Fcb_client%3Dmaps_sv.tactile%26w%3D900%26h%3D600%26pitch%3D-0.5499999999999972%26panoid%3DDqEws0cUOihYSKbL6A4h_A%26yaw%3D4.98!7i16384!8i8192!4m16!1m8!3m7!1s0x132f61b6532013ad:0x28f1c82e908503c4!2sColiseo+de+Roma!8m2!3d41.8902102!4d12.4922309!10e5!16zL20vMGQ1cXg!3m6!1s0x132f61b6532013ad:0x28f1c82e908503c4!8m2!3d41.8902102!4d12.4922309!10e5!16zL20vMGQ1cXg?entry=ttu&g_ep=EgoyMDI1MTExMS4wIKXMDSoASAFQAw%3D%3D (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Google Maps. Acropolis of Athens. Available online: https://www.google.com/maps/place/Acr%C3%B3polis+de+Atenas/@37.9715834,23.7256594,3a,62.2y,101.31h,104.2t/data=!3m8!1e1!3m6!1sCIHM0ogKEICAgIChht-Z0QE!2e10!3e11!6shttps:%2F%2Flh3.googleusercontent.com%2Fgpms-cs-s%2FAPRy3c_y1g5MK07TIOoC7u95IPOLDRJ1ATQMhGTb0NsSlDLo9kADEnE7dQKeyKM3XSs16DdjBZVBPBz3VvEUbuwzNP-gGxBU5e0NQvh36o3T-icyO-gNPYuy1HsEHOX4YMMbqOsTacmwlg%3Dw900-h600-k-no-pi-14.200000000000003-ya101.31-ro0-fo100!7i4608!8i2304!4m7!3m6!1s0x14a1bd1837f5acf3:0x5c97c042f5eb0df6!8m2!3d37.9715323!4d23.7257492!10e5!16zL20vMHdqag?entry=ttu&g_ep=EgoyMDI1MTExMS4wIKXMDSoASAFQAw%3D%3D (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Google Maps. Angkor Wat Temple Complex. Available online: https://www.google.com/maps/place/Angkor+Wat/@13.4125003,103.860239,3a,75y,82.44h,93.63t/data=!3m7!1e1!3m5!1s2ga34IvqITSM5l3d2DQ2xg!2e0!6shttps:%2F%2Fstreetviewpixels-pa.googleapis.com%2Fv1%2Fthumbnail%3Fcb_client%3Dmaps_sv.tactile%26w%3D900%26h%3D600%26pitch%3D-3.6299999999999955%26panoid%3D2ga34IvqITSM5l3d2DQ2xg%26yaw%3D82.44!7i13312!8i6656!4m16!1m8!3m7!1s0x3110168aea9a272d:0x3eaba81157b0418d!2sAngkor+Wat!8m2!3d13.4124693!4d103.8669857!10e5!16zL20vMDE5eGZs!3m6!1s0x3110168aea9a272d:0x3eaba81157b0418d!8m2!3d13.4124693!4d103.8669857!10e5!16zL20vMDE5eGZs?entry=ttu&g_ep=EgoyMDI1MTExMS4wIKXMDSoASAFQAw%3D%3D (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Google Maps. Giza Pyramid Complex. Available online: https://www.google.com/maps/place/Pir%C3%A1mides+de+Giza/@29.9734559,31.1323504,3a,50.4y,327.7h,95.57t/data=!3m8!1e1!3m6!1sCIHM0ogKEICAgIDG8amJywE!2e10!3e12!6shttps:%2F%2Flh3.googleusercontent.com%2Fgpms-cs-s%2FAPRy3c9j102vCAAv9ViGMLfPgq-BldvYj-yrcGFwNu4kQ5QaoDiZTTvVq5OOMRQ_MDrb77NxouNFb1R3zFAfVfOBy3MF_XvJo0O5HPqW0MavmzjMhXMS84BkfciuLSdHdJ1-3EXKdBfKug%3Dw900-h600-k-no-pi-5.569999999999993-ya359.6161682128906-ro0-fo100!7i6080!8i3040!4m16!1m8!3m7!1s0x14584f7de239bbcd:0xca7474355a6e368b!2sPir%C3%A1mides+de+Giza!8m2!3d29.9772962!4d31.1324955!10e5!16s%2Fm%2F07s6gb8!3m6!1s0x14584f7de239bbcd:0xca7474355a6e368b!8m2!3d29.9772962!4d31.1324955!10e5!16s%2Fm%2F07s6gb8?entry=ttu&g_ep=EgoyMDI1MTExMS4wIKXMDSoASAFQAw%3D%3D (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Arguello, J.A. Petra y el Reino Nabateo. Available online: https://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?pid=S2448-654X2025000200401&script=sci_arttext (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Sánchez, A. Arquitectura y Funcionalidad del Gran Templo de Requem. Available online: https://repositorio.uca.edu.ar/bitstream/123456789/6579/1/arquitectura-funcionalidad-gran-templo-requem.pdf (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Simó, P. Cimientos y Estructura de las Pirámides de Giza. Available online: https://d1wqtxts1xzle7.cloudfront.net/35250600/Cimientos_y_estructura_de_las_piramides_de_Giza_i-with-cover-page-v2.pdf (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Rango, M. La Geometría de la Pirámide de Khufu. Available online: https://funes.uniandes.edu.co/wp-content/uploads/tainacan-items/32454/1168068/Rango2013La.pdf (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Ochoa, A. La fascinante arquitectura de la pirámide de Kukulkán en Chichén Itzá. In Architectural Digest; Condé Nast: New York, NY, USA, 2021; Available online: https://www.admagazine.com/arquitectura/piramide-kukulcan-arquitectura-en-chichen-itza-20210226-8182-articulos (accessed on 24 August 2024).

- National Geographic. Chichén Itzá: El Asombroso Legado de los Mayas y los Toltecas; Ediciones EL PAÍS S.L.: Madrid, Spain, 2015; Available online: https://elpais.com/cultura/2015/10/23/actualidad/1445612256_274708.html (accessed on 24 August 2024).

- Google Maps. The City of Petra. Available online: https://www.google.com/maps/place/Petra/@30.3284544,35.4443622,3a,75y,13.99h,102.51t/data=!3m8!1e1!3m6!1sCIHM0ogKEICAgICE37CGugE!2e10!3e11!6shttps:%2F%2Flh3.googleusercontent.com%2Fgpms-cs-s%2FAPRy3c8VBrSLnBgYT0c5W9fWMbXjleYrGalWGcbiFumdBjNXdslWapW1YY0vgUs_bDMlSbjaw_xseKXcj-rtASDTQLfKJu2KQdAEOXpKwQv1oj6gjuMlkSenfac2jdZFM0yLV1_un8Hgfw%3Dw900-h600-k-no-pi-12.510000000000005-ya13.99-ro0-fo100!7i7200!8i3600!4m16!1m8!3m7!1s0x15016ef1703b6071:0x199bf908679a2291!2sPetra!8m2!3d30.3284544!4d35.4443622!10e5!16zL20vMGM3enk!3m6!1s0x15016ef1703b6071:0x199bf908679a2291!8m2!3d30.3284544!4d35.4443622!10e5!16zL20vMGM3enk?entry=ttu&g_ep=EgoyMDI1MTExMC4wIKXMDSoASAFQAw%3D%3D (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Google Maps. The Pyramid of Khufu. Available online: https://www.google.com/maps/place/Pir%C3%A1mides+de+Giza/@29.9773163,31.1336364,2a,75y,233.07h,100.6t/data=!3m7!1e1!3m5!1s4-ZxUJ4QyqTTipG7ao2fXw!2e0!6shttps:%2F%2Fstreetviewpixels-pa.googleapis.com%2Fv1%2Fthumbnail%3Fcb_client%3Dmaps_sv.tactile%26w%3D900%26h%3D600%26pitch%3D-10.604854117460448%26panoid%3D4-ZxUJ4QyqTTipG7ao2fXw%26yaw%3D233.06813600411846!7i13312!8i6656!4m10!1m2!2m1!1spiramide+de+giza!3m6!1s0x14584f7de239bbcd:0xca7474355a6e368b!8m2!3d29.9772962!4d31.1324955!15sChBwaXJhbWlkZSBkZSBnaXphWhIiEHBpcmFtaWRlIGRlIGdpemGSARNhcmNoYWVvbG9naWNhbF9zaXRlqgFDCggvbS8wMzZtaxABMh8QASIbENEerQBZKij0ig_L-KGcFvkFPlabSy6BtRdyMhQQAiIQcGlyYW1pZGUgZGUgZ2l6YeABAA!16s%2Fm%2F07s6gb8?entry=ttu&g_ep=EgoyMDI1MTExMS4wIKXMDSoASAFQAw%3D%3D (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Google Maps. Kukulkán Pyramid-Temple. Available online: https://www.google.com/maps/place/El+Castillo/@20.6832753,-88.569522,3a,75y,110.29h,95.48t/data=!3m7!1e1!3m5!1sm4fh3QtrxZrYsCUfVey4ng!2e0!6shttps:%2F%2Fstreetviewpixels-pa.googleapis.com%2Fv1%2Fthumbnail%3Fcb_client%3Dmaps_sv.tactile%26w%3D900%26h%3D600%26pitch%3D-5.477774228131068%26panoid%3Dm4fh3QtrxZrYsCUfVey4ng%26yaw%3D110.28852258110919!7i13312!8i6656!4m14!1m7!3m6!1s0x8f5138b88e232523:0x1ef4200c7824ddf!2sEl+Castillo!8m2!3d20.6829859!4d-88.5686491!16zL20vMDY2N2R5!3m5!1s0x8f5138b88e232523:0x1ef4200c7824ddf!8m2!3d20.6829859!4d-88.5686491!16zL20vMDY2N2R5?entry=ttu&g_ep=EgoyMDI1MTExMS4wIKXMDSoASAFQAw%3D%3D (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Instituto Peruano de Estudios Arqueológicos. Reseña: Urbanismo Andino, Centro Ceremonial y Ciudad en el Perú Prehispánico; Instituto Peruano de Estudios Arqueológicos: Lima, Peru, 2021; Available online: https://ipearqueologia.wordpress.com/2021/08/26/resena-urbanismo-andino-centro-ceremonial-y-ciudad-en-el-peru-prehispanico/ (accessed on 24 August 2024).

- El Peruano. Herencia Cultural. Available online: https://www.elperuano.pe/noticia/241808-herencia-cultural (accessed on 24 August 2024).

- Maganga, M. El Vínculo Entre Arqueología y Arquitectura; ArchDaily: Lima, Peru, 2021; Available online: https://www.archdaily.pe/pe/961943/el-vinculo-entre-arqueologia-y-arquitectura (accessed on 24 August 2024).

- SIGDA. Sistema de Información Geográfica para la Defensa del Patrimonio Arqueológico. Ministerio de Cultura del Perú: Lima, Peru. Available online: https://sigda.cultura.gob.pe/ (accessed on 23 August 2024).

- Google Maps. Chan Chan Citadel. Available online: https://www.google.com/maps/place/Chan+Chan/@-8.1101067,-79.0745124,3a,75y,171.29h,79.34t/data=!3m8!1e1!3m6!1sCIHM0ogKEICAgIDqhff72gE!2e10!3e11!6shttps:%2F%2Flh3.googleusercontent.com%2Fgpms-cs-s%2FAPRy3c-N_ddBaDfA5EqGhH-JOWLvIbCPEb_WywrQECyvbp2SKHe_S0KSYQEa5Ri5p7aXFUWwhrOQYiz4as98W_pQXrcNHhSWCz0WJXW8znoVW8_ySDU8-7hZGQfpklvNH2zaxjloN9Je%3Dw900-h600-k-no-pi10.659999999999997-ya171.29-ro0-fo100!7i6000!8i3000!4m16!1m8!3m7!1s0x91ad3c5aac618ac5:0xcb9b94821b72a829!2sChan+Chan!8m2!3d-8.1085762!4d-79.0752648!10e5!16zL20vMDRqamRi!3m6!1s0x91ad3c5aac618ac5:0xcb9b94821b72a829!8m2!3d-8.1085762!4d-79.0752648!10e5!16zL20vMDRqamRi?entry=ttu&g_ep=EgoyMDI1MTExMS4wIKXMDSoASAFQAw%3D%3D (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Google Maps. Great Pyramid of Caral. Available online: https://www.google.com/maps/place/Caral+15161/@-10.8904442,-77.5221677,204m/data=!3m1!1e3!4m6!3m5!1s0x9107178335c178e1:0x52b23b360fa2d66a!8m2!3d-10.8920691!4d-77.5232461!16s%2Fg%2F11bc6n86p3?entry=ttu&g_ep=EgoyMDI1MTExMS4wIKXMDSoASAFQAw%3D%3D (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Google Maps. ‘The Monkey’ Geoglyph in Nazca. Available online: https://earth.google.com/web/search/lineas+de+nazcamono+mazca/@-14.70684272,-75.13836589,456.71699429a,213.91410712d,35y,360h,0t,0r/data=CiwiJgokCQ3VgWT0ci3AEYtDFGz-qS3AGVsh0ju9vFLAIaxDfR1yzFLAQgIIAToDCgEwQgIIAEoNCP___________wEQAA?authuser=0 (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Burger, R.L.; MacCurdy, C.L.; Salazar, L.C. Machu Picchu: Unveiling the Mystery of the Incas; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2004; Available online: https://books.google.com.pe/books?id=bBHrWwtr_pYC (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Valcárcel, L.E. Machu Picchu El más Famoso Monumento Arqueológico del Perú. Available online: https://repositorio.uigv.edu.pe/item/09b648a9-dab3-4f66-8d71-1b896b0702f6 (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Bustamante, J.; Crousillat, E.; Rick, J. Nuevos conceptos sobre la secuencia constructiva y usos de la red de canales de Chavín de Huántar. Devenir Rev. De Estud. Sobre Patrim. Edif. 2021, 8, 75–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cueva, M. La Cultura Chavín en Perú; Sibila—Revista de Poesia e Crítica Literária: São Paulo, Brasil, 2011; Available online: https://sibila.com.br/cultura/la-cultura-chavin-en-peru/4710 (accessed on 24 August 2024).

- Villanueva, J. Moray Laboratorio Agrícola INCA. YouTube: Online. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NgIUiFpo2rc (accessed on 7 August 2024).

- Earls, J. Moray: Agua, Control y Biodiversidad de los Andes. Available online: https://www.minam.gob.pe/diadiversidad/wp-content/uploads/sites/63/2015/01/resumen2.pdf (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Andina.pe. Siete Sitios Arqueológicos de Obligada Visita que Muestran la Grandeza Cultural del Perú. 2024. Available online: https://andina.pe/agencia/noticia-conoce-7-sitios-arqueologicos-obligada-visita-muestran-grandeza-cultural-peruana-993567.aspx (accessed on 24 August 2024).

- Huaman, F.; Esenarro, D.; Prado Meza, J.; Vilchez Cairo, J.; Vargas Beltran, C.; Alfaro Aucca, C.; Arriola, C.; Calle, V.P. Biophysical, Spatial, Functional, and Constructive Analysis of the Pre-Hispanic Terraces of the Ancient City of Pisaq, Cusco, Peru. Heritage 2024, 7, 6526–6565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilchez, J.; Rodriguez, A.N.; Esenarro, D.; Ruiz, C.; Alfaro, C.; Ruiz, R.; Veliz, M. Green Infrastructure and the Growth of Ecotourism at the Ollantaytambo Archeological Site, Urubamba Province, Peru, 2024. Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PUCP. Acciones para la Conservación del patrimonio natural y cultural en el Parque Nacional Huascarán y el Santuario Histórico de Machu Picchu. 2023. Available online: https://www.pucp.edu.pe/climadecambios/noticias/acciones-para-la-conservacion-del-patrimonio-natural-y-cultural-en-el-parque-nacional-huascaran-y-el-santuario-historico-de-machu-picchu/ (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Dirección Desconcentrada de Cultura de Cusco. Parques Arqueológicos. Instituto Colombiano de Antropología: Bogotá, Colombia. Available online: https://www.culturacusco.gob.pe/parques-arqueologicos/ (accessed on 24 August 2024).

- Google Maps. Tambomachay Archaeological Site. Available online: https://www.google.com/maps/@-13.4790027,-71.9673597,3a,90y,181.65h,100.64t/data=!3m8!1e1!3m6!1sCIHM0ogKEI-CAg-IDn1JrIzwE!2e10!3e11!6shttps:%2F%2Flh3.googleusercontent.com%2Fgpms-cs-s%2FAPRy3c__DK2WjOd-DiRt6U2pW6YmCJN_J_jzG3IbKfWeelHJwfSQQv6JEiUYK-oAKsMLB-8WSzWcupw588GTv1HWjLWknaVFKzdLtXKWMm9ubS5McBOa8Xko0B0sOJHwWmKqPvhsCcuR%3Dw900-h600-k-no-pi-10.64-ya341.65-ro0-fo100!7i8704!8i4352?entry=ttu&g_ep=EgoyMDI1MTExMS4wIKXMDSoASAFQAw%3D%3D (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Google Maps. Qenqo Archaeological Complex. Complejo Arqueológico Q’enqo—Google Maps. Available online: https://www.google.com/maps/place/Complejo+Arqueol%C3%B3gico+Q’enqo/@-13.5090857,-71.971375,3a,15y,82.66h,92.2t/data=!3m7!1e1!3m5!1smwYJ-miyMlEWQqq8-sDTJg!2e0!6shttps:%2F%2Fstreetviewpixels-pa.googleapis.com%2Fv1%2Fthumbnail%3Fcb_client%3Dmaps_sv.tactile%26w%3D900%26h%3D600%26pitch%3D-2.203231723323867%26panoid%3DmwYJ-miyMlEWQqq8-sDTJg%26yaw%3D82.6617306962352!7i16384!8i8192!4m14!1m7!3m6!1s0x916dd61234a0e6bb:0xa80b297d8c27d!2sComplejo+Arqueol%C3%B3gico+Q’enqo!8m2!3d-13.5088984!4d-71.9706558!16s%2Fm%2F076yq31!3m5!1s0x916dd61234a0e6bb:0xa80b297d8c27d!8m2!3d-13.5088984!4d-71.9706558!16s%2Fm%2F076yq31?entry=ttu&g_ep=EgoyMDI1MTExNy4wIKXMDSoASAFQAw%3D%3D (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Rodríguez, M. El Perú en el Sistema Internacional del Patrimonio Cultural y Natural de la Humanidad; Fondo Editorial de la Universidad de San Martín de Porres: Lima, Peru, 2019; Available online: http://catedraunesco.usmp.edu.pe/pdf/sistema_internacional_del_patrimonio.pdf (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Esenarro, D.; Gutierrez, D.P.; Peña, K.S.C.; Cairo, J.V.; Anzualdo, V.I.T.; Garagatti, M.V.; Delgado, G.W.S.; Aucca, C.A. Water Efficiency in the Construction of Water Channels and the Ancestral Constructive Sustainability of Cumbemayo, Peru. Heritage 2025, 8, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobpe, Z.A. De Choquequirao—Dirección Desconcentrada de Cultura de Cusco. Available online: https://www.culturacusco.gob.pe/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/DDC-Z.A.-DE-CHOQUEQUIRAO-2021.pdf (accessed on 24 August 2024).

- Burga, M. Choquequirao: Símbolo de la Resistencia Andina (Historia, Antropología y Lingüística); Institut Français D’études Andines: Lima, Peru, 2008; Available online: https://books.openedition.org/ifea/5995 (accessed on 24 August 2024).

- Bayona, D. 10 Sitios Arqueológicos que Todo Arquitecto Debería Visitar en el Perú; ArchDaily: Lima, Peru, 2017; Available online: https://www.archdaily.pe/pe/868585/10-sitios-arqueologicos-que-todo-arquitecto-deberia-visitar-en-el-peru (accessed on 24 August 2024).

- Arte Peruano. Machu Picchu. Arte Peruano: Cusco, Peru. Available online: https://arteperuano.com.pe/index.php/component/sppagebuilder/?view=page&id=81 (accessed on 24 August 2024).

- Fenando, P. Incarail.com. Choquequirao. 2024. Available online: https://blogs.incarail.com/es/choquequirao (accessed on 24 August 2024).

- Olmo, G.D. Cómo es Choquequirao, el “otro Machu Picchu” de Perú, y por qué no es tan Conocido ni Visitado; BBC: London, UK, 2023; Available online: https://www.bbc.com/mundo/articles/cyrjey50pe5o (accessed on 24 August 2024).

- Lévano, R.C.C. Choquequirao: La Próxima Maravilla del Mundo; Blog USIL: Lima, Peru, 2021; Available online: https://blogs.usil.edu.pe/facultad-htg/administracion-hotelera-turismo-y-gastronomia/choquequirao-la-proxima-maravilla-del-mundo (accessed on 24 August 2024).

- Bosuer Moto Perú. Las Áreas de Conservación Regional: Protegiendo lo Mejor de las Regiones. Bosuer Moto Perú: Lima, Peru. Available online: https://actualidadambiental.pe/acr/ (accessed on 24 August 2024).

- Kendall, A.; Rodríguez, A. Desarrollo y Perspectivas de los Sistemas de Andenería de los Andes Centrales del Perú; Institut Français D’études Andines: Lima, Peru, 2009; Available online: https://books.openedition.org/ifea/6110 (accessed on 8 November 2025).

- Peru.travel. Available online: https://www.peru.travel/es/atractivos/choquequirao (accessed on 24 August 2024).

- Edu.pe. Available online: https://revistas.lamolina.edu.pe/index.php/ne/article/download/1532/html_35?inline=1 (accessed on 28 August 2024).

- Google.com. Available online: https://earth.google.com/web (accessed on 24 August 2024).

- Stehberg, R. ¿Qué es un Ushnu?. Museo Nacional de Historia Natural. 2021. Available online: https://www.mnhn.gob.cl/noticias/que-es-un-ushnu (accessed on 8 November 2025).

- Sequeira, A.G.; Macome, A.S. El Ushnu Incaico en el Extremo Suroeste del Tawantinsuyu. 2004. Available online: https://www.scielo.cl/scielo.php?pid=S0717-73562004000200005&script=sci_arttext (accessed on 8 November 2025).

- Guaña p. LA PACHA. Scribd. 2009. Available online: https://es.scribd.com/doc/20389526/LA-PACHA (accessed on 8 November 2025).

- Poma, E. La Noción de Pacha: Un Pilar en la Cosmovisión Andina. Alteridades. 2019. Available online: https://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1665-12002019000200165 (accessed on 8 November 2025).

- Barraza, S. El Ushnu de Choquequirao. Bull. L’institut Français D’études Andin 2014, 1, 46–113. Available online: https://es.scribd.com/document/494185941/Choquequirao-Burga-IFEA (accessed on 8 November 2025).

- Raffino, R.A.; Iturriza, R.D.; Gobbo, J.D. El ushnu y la tiana de El Shincal. In Arquitectura, Poder y Religion; Raffino, R., Ed.; El Shincal de Quimivil: Londres, Argentina, 2004; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/275328906_El_ushnu_y_la_tiana_de_El_Shincal_Arquitectura_poder_y_religion (accessed on 8 November 2025).

- Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian. Colcas. Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian. 2020. Available online: https://americanindian.si.edu/inkaroad/engineering/es/video/colcas.html (accessed on 8 November 2025).

- Echevarría, G.T.; Valencia, Z. Choquequirao, un Asentamiento Imperial Cusqueño del Siglo XV en la Amazonía Andina. Rev. Haucaypata. 2011. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/305378605_Choquequirao_un_asentamiento_imperial_cusqueno_del_siglo_XV_en_la_Amazonia_andina (accessed on 8 November 2025).

- SENAMHI. Pronóstico Meteorológico. SENAMHI: Lima, Peru. Available online: https://www.senamhi.gob.pe/?&p=pronostico-meteorologico (accessed on 24 August 2024).

- Ministerio del Ambiente. Available online: https://www.gob.pe/minam (accessed on 24 August 2024).

- EcoRegistros. Especies de Área de Conservación Regional Choquequirao—Listado Sistemático. EcoRegistros: Buenos Aires, Argentina. Available online: https://www.ecoregistros.org/site/lugar.php?id=11241 (accessed on 12 May 2024).

- INAIGEM. Políticas Ecosistemas. INAIGEM: Huaraz, Peru. Available online: https://inaigem.gob.pe/web2/politicas-ecosistemas/ (accessed on 24 August 2024).

- ACCA. ACR CHOQUEQUIRAO. 2021. Available online: https://acca.org.pe/acr-choquequirao-3/ (accessed on 22 August 2024).

- Chaparro, J.; Zolorzano, J.; Carrasco, A.; Bustamante, A. Field Guide of Flora and Fauna of the Choquequirao Regional Conservation Area. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/376516997_Guia_de_campo_de_Flora_y_Fauna_del_Area_de_Conservacion_Regional_Choquequirao (accessed on 15 May 2024).

- Cuadros, M.R. Preservation and Protection of Peru’s Cultural Heritage Within the Framework of the World Heritage Convention. Edu.pe. Available online: http://catedraunesco.usmp.edu.pe/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/conferencia_manuel_rodriguez.pdf (accessed on 24 October 2024).

- Por, P. Ecotourism Complex in Cusco. Edu.pe. Available online: https://repositorio.usmp.edu.pe/bitstream/20.500.12727/4078/1/ortiz_tp.pdf (accessed on 24 October 2024).

- Angulo, L.S. Analysis of Cultural Material Sector IX Pikiwasi—Choquequirao, Use and Function of Spaces; Universidad Nacional de San Antonio Abad del Cusco. 2016. Available online: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/a2f0/e8336ec0d63b0d78ca1a00df298af425c8af.pdf (accessed on 24 October 2024).

- National Geographic. Poaching Threatens the Only Bear Species of South America. Available online: https://www.nationalgeographicla.com/animales/2019/06/la-caza-furtiva-amenaza-las-unicas-especies-de-osos-de-america-del-sur (accessed on 17 August 2024).

- iNaturalist Ecuador. Quito Marsupial Frog (Gastrotheca riobambae). Available online: https://ecuador.inaturalist.org/taxa/24132-Gastrotheca-riobambae (accessed on 17 August 2024).

- iNaturalist Ecuador. Schott’s Whip Snake (Masticophis schotti). Available online: https://ecuador.inaturalist.org/taxa/29421-Masticophis-schotti (accessed on 17 August 2024).

- Aves de Peru. Black-and-Chestnut Eagle (Spizaetus isidori). Available online: https://avesdeperu.org/accipitridae/aguila-negra-y-castana-spizaetus-isidori/ (accessed on 17 August 2024).

- Arizona State University. The Jewel Bee. Available online: https://askabiologist.asu.edu/la-abeja-enjoyada (accessed on 17 August 2024).

- Vacas, C. Shrew or Elephant? This Tiny Animal Isn’t Quite Sure. National Geographic. 2024. Available online: https://www.nationalgeographic.com.es/mundo-animal/mirando-a-musaranas-trompa-elefante_21936 (accessed on 17 August 2024).

- Ministry of Culture of Peru. Republic of Peru. Available online: https://transparencia.cultura.gob.pe/sites/default/files/transparencia/2020/10/resoluciones-ministeriales/rm261-2020-dm-mc-anexo.pdf (accessed on 24 August 2024).

- Instituto Geológico, Minero y Metalúrgico (INGEMMET). Geology Bulletin of Choquequirao. Available online: https://repositorio.ingemmet.gob.pe/bitstream/20.500.12544/375/2/I-004-Boletin-Geologia_de_Choquequirao.pdf (accessed on 24 August 2024).

- Carlotto, V.; Cárdenas, J.; Fidel, L.; Oviedo, M. Geoarchaeology of Choquequirao and Its Relationship with Machu Picchu. Available online: https://repositorio.ingemmet.gob.pe/bitstream/20.500.12544/3240/1/Carlotto-Geoarquelogia_Choquequirao_Machupicchu.pdf (accessed on 24 August 2024).

- Bingham, H. The Ruins of Choqquequirau. Am. Anthr. 1910, 12, 505–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edu.pe. Available online: https://revistasinvestigacion.unmsm.edu.pe/index.php/Arqueo/article/download/13295/11781/ (accessed on 24 August 2024).

- Apaza Huamani, J.; Gallegos Gutiérrez, H. Choquequirao and the textiles for the gods and Inca lords. In Archaeology and Society; Barnes & Noble: Washington, DC, USA, 1957; Available online: https://doi.org/10.15381/arqueolsoc.2014n27.e12205 (accessed on 24 August 2024).

- Academia.edu. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/download/65435064/John_Apaza_Huamani_EL_OTRO_CUSCO_CHOQUEQUIRAO.pdf (accessed on 24 August 2024).

- Angulo, L. Choquequirao: Use and Function of Spaces Through Cultural Evidence—Sector IX Pikiwasi. Science and Development. Available online: http://revistas.uap.edu.pe/ojs/index.php/CYD/article/view/1408 (accessed on 24 August 2024).

- Torres, C.A.F. Presentation. Archaeology and Society. Available online: https://revistasinvestigacion.unmsm.edu.pe/index.php/Arqueo/article/view/20257 (accessed on 24 October 2024).

- Ortiz de Orué, H. Estimation of Social Benefits Reported by Conservation and Tourism in the Choquequirao Natural Area. Let Verdes Rev Latinoam Estud Socioambientales. Available online: http://scielo.senescyt.gob.ec/scielo.php?pid=S1390-66312020000100167&script=sci_arttext (accessed on 24 August 2024).

- Gob.pe. Available online: https://alicia.concytec.gob.pe/vufind/Record/PUCP_6e0d33e01dab28889f18d7db59e9f3c1 (accessed on 24 August 2024).

- Revista Andina. Org.pe. Available online: https://revista.cbc.org.pe/ (accessed on 24 October 2024).

- Tomasini, M.C. The Cosmological Symbolism of Sacred Architecture. Edu.ar. Available online: https://repositorio.uca.edu.ar/bitstream/123456789/17955/1/simbolismo-cosmol%C3%B3gico-arquitectura.pdf (accessed on 24 October 2024).

- Santiago, C.C.V.; Dionicio, C.R.J.; Lionel, F.S.; Jhonatan, O.M.M.; Walter, P.P. Geology of Choquequirao—[Bulletin I 4]. Available online: https://repositorio.ingemmet.gob.pe/handle/20.500.12544/375 (accessed on 24 August 2024).

- Getyourguide.es. Available online: https://www.getyourguide.es/peru-l168997/cusco-explora-choquequirao-cuna-del-oro-3-dias-t653121/ (accessed on 3 August 2024).

- Choquequirao (III): Questions and Reflections/Choquequirao, Wonderings and Thoughts. Formentí Natura (Blog). 2012. Available online: https://formentinatura.wordpress.com/2012/01/01/choquequirao-iii-preguntas-y-reflexiones-choquequirao-wonderings-and-thoughts/ (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- Boletín de Arqueología PUCP. Edu.pe. Available online: https://revistas.pucp.edu.pe/index.php/boletindearqueologia (accessed on 24 October 2024).

- Gob.pe. Available online: https://app.ingemmet.gob.pe/biblioteca/pdf/CPG14-185.pdf (accessed on 24 November 2024).

- Huamani, J.A.; Yapura, W.B. The Other Cusco: Choquequirao. In Archaeology and Society; Barnes & Noble: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; pp. 165–196. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/353562874_EL_OTRO_CUSCO_CHOQUEQUIRAO (accessed on 24 August 2024).

- Le Scano, S.B. The Coastal Inca Materiality in the Discourse of Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Century Travelers and Pioneer Archaeologists. Cultura.pe. Available online: https://qhapaqnan.cultura.pe/sites/default/files/articulos/CQNn6Barraza.pdf (accessed on 24 October 2024).

- Edu.pe. Available online: https://repositorio.utea.edu.pe/items/4a773458-2b52-48dd-a8fb-879cdc1efc79 (accessed on 24 August 2024).

- Ziegler, G.R.; Malville, J.M. Choquequirao, Topa Inca’s Machu Picchu: A Royal Estate and Ceremonial Center. Proc. Int. Astron. Union 2011, 7, 162–168. Available online: https://www.cambridge.org/core/services/aop-cambridge-core/content/view/32882CCD4C95178F5F9DAE9B760B8B5E/S1743921311012580a.pdf/choquequirao-topa-incas-machu-picchu-a-royal-estate-and-ceremonial-center.pdf (accessed on 24 August 2024). [CrossRef]

- Coronel, J. Choquequirao—La Cuna de Oro de los Incas. TreXperience. Available online: https://trexperienceperu.com/es/blog/choquequirao#:~:text=El%20Parque%20Arqueol%C3%B3gico%20de%20Choquequirao,de%20La%20Convenci%C3%B3n%20en%20Cusco (accessed on 24 August 2024).

- Peru Mysteries. Chquekirao. Available online: https://www.perumysteries.com/es/choquequirao.html#:~:text=La%20ciudadela%20inca%20de%20Choquequirao,del%20valle%20del%20r%C3%ADo%20Apur%C3%ADmac (accessed on 24 August 2024).

- Barraza, S. Redefining an Inca Architectural Category: The Kallanka. Bull Inst. Études Andin 2010, 1, 167–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrington, I.S.; Zapata, J. New Canons of Inka Architecture: Investigations at the Site of Tambokan-cha-Tumibamba, Jaquijahuana, Cuzco. Bol Arqueol PUCP. 2003. Available online: https://revistas.pucp.edu.pe/index.php/boletindearqueologia/article/view/1985 (accessed on 24 August 2024).

- Institutional Repository—UNI: Home Page. Edu.pe. Available online: https://cybertesis.uni.edu.pe/ (accessed on 24 October 2024).

- Salkantay, C. Choquequirao: From the Cradle of Gold to the New York Times. Available online: https://www.caminosalkantay.com/blog/choquequirao-de-la-cuna-del-oro-al-new-york-times/ (accessed on 21 August 2024).

- Academia.edu. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/download/109786958/REVISTA_NAWPA_MARCA_2.pdf#page=93 (accessed on 24 August 2024).

- Guevara Flores, D.V.; Acero Valencia, M.P. Archaeology in Pukara Pantillijlla: Stratigraphic Analysis of the Visible Diagnostic Architecture, Pisac-Cusco; Universidad Nacional de San Antonio Abad del Cusco: Cusco, Peru, 2023; Available online: https://repositorio.unsaac.edu.pe/handle/20.500.12918/7753?show=full (accessed on 24 August 2024).

- Scielo.cl. Available online: https://www.scielo.cl/scielo.php?pid=S0718-10432003002600004&script=sci_arttext&tlng=en (accessed on 16 November 2024).

- Salas, A.C. Pre-Hispanic Terracing and Risk Management. Analysis of Its Valorization as a Factor of Cultural Development, Pisac-Cusco. Doctoral Dissertation, Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, Lima, Peru, 2017. Available online: https://repositorio.cultura.gob.pe/bitstream/handle/CULTURA/637/Paisajes%20Culturales%20en%20Am%C3%A9rica%20Latina.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 24 August 2024).

- Santana, A. Centennial of Machu Picchu. Archipiélago 2011, 52–53. [Google Scholar]

- Maclean, M.G.A.D. Sacred Land, Sacred Water: Inca Landscape Planning in the Cuzco Area (Architecture, Peru, Machu Picchu). 1986. Available online: https://www.machupicc.hu/the-legacy-of-inca-landscape-planning/ (accessed on 16 November 2024).

- Novoa Sucari, Y.B.; Carcausto Herencia, L.D. Urban–Architectural Study of the Inca Llaqta of Machu Picchu. 2018. Available online: https://repositorio.unsaac.edu.pe/handle/20.500.12918/3764?locale-attribute=en (accessed on 16 November 2024).

- Edu.pe. Available online: https://tesis.pucp.edu.pe/repositorio/bitstream/handle/20.500.12404/23930/TINEO_LACMA_DANIEL_FRANCISCO.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 24 October 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Esenarro, D.; Bacalla, S.; Chuquiano, T.; Vilchez Cairo, J.; Salas Delgado, G.W.; Bouroncle Velásquez, M.R.; Legua Terry, A.I.; Sánchez Medina, A.G. Ancestral Inca Construction Systems and Worldview at the Choquequirao Archaeological Site, Cusco, Peru, 2024. Heritage 2025, 8, 494. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8120494

Esenarro D, Bacalla S, Chuquiano T, Vilchez Cairo J, Salas Delgado GW, Bouroncle Velásquez MR, Legua Terry AI, Sánchez Medina AG. Ancestral Inca Construction Systems and Worldview at the Choquequirao Archaeological Site, Cusco, Peru, 2024. Heritage. 2025; 8(12):494. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8120494

Chicago/Turabian StyleEsenarro, Doris, Silvia Bacalla, Tatiana Chuquiano, Jesica Vilchez Cairo, Geoffrey Wigberto Salas Delgado, Mauricio Renato Bouroncle Velásquez, Alberto Israel Legua Terry, and Ana Guadalupe Sánchez Medina. 2025. "Ancestral Inca Construction Systems and Worldview at the Choquequirao Archaeological Site, Cusco, Peru, 2024" Heritage 8, no. 12: 494. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8120494

APA StyleEsenarro, D., Bacalla, S., Chuquiano, T., Vilchez Cairo, J., Salas Delgado, G. W., Bouroncle Velásquez, M. R., Legua Terry, A. I., & Sánchez Medina, A. G. (2025). Ancestral Inca Construction Systems and Worldview at the Choquequirao Archaeological Site, Cusco, Peru, 2024. Heritage, 8(12), 494. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8120494