Domestic and Productive Earthen Architecture Conserved In Situ in Archaeological Sites of the Iberian Peninsula

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Case Studies

2.2. Characteristics and Statistical Management of Information

3. Results

3.1. Historical, Urbanistic, Typological and Use Characteristics

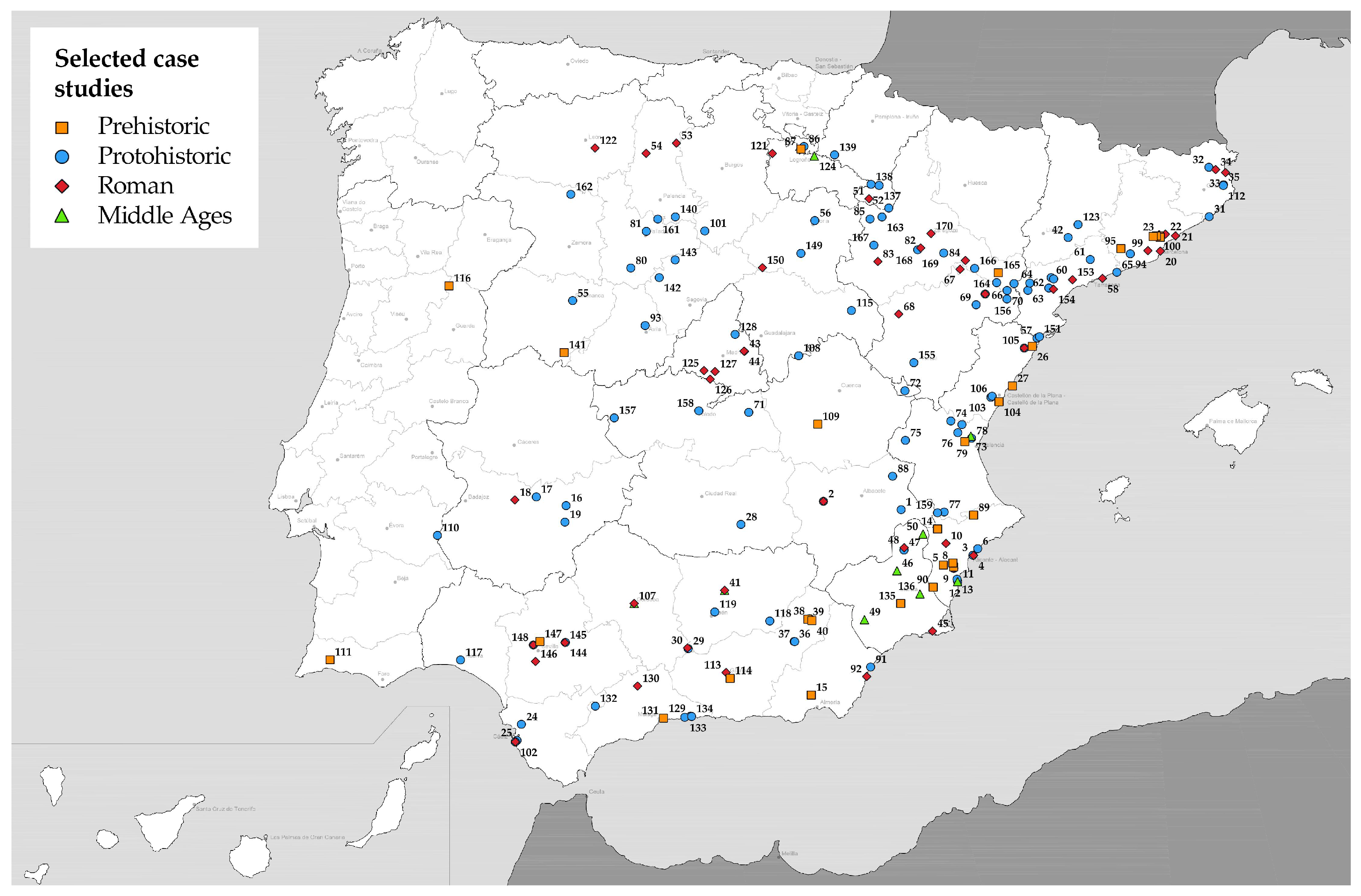

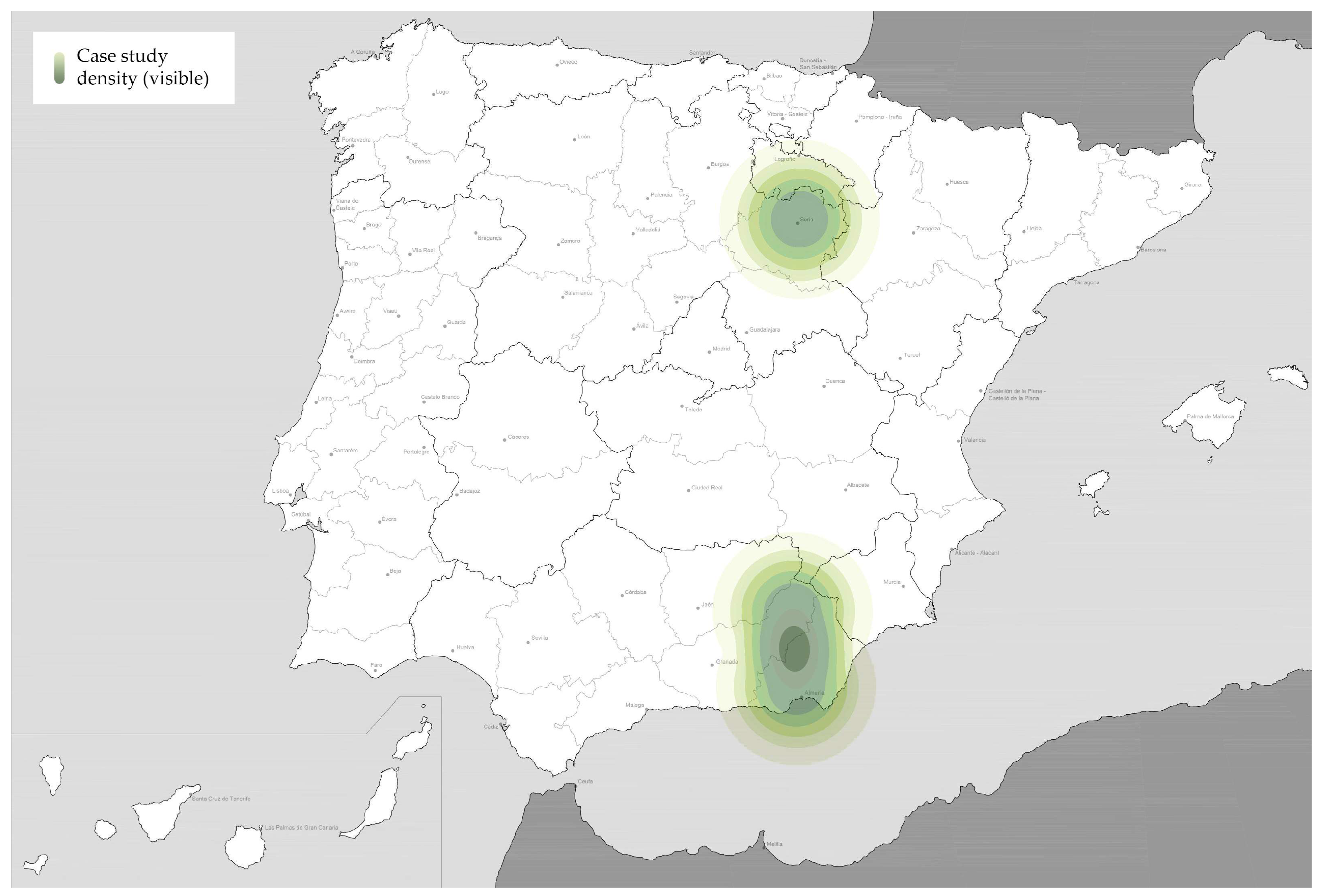

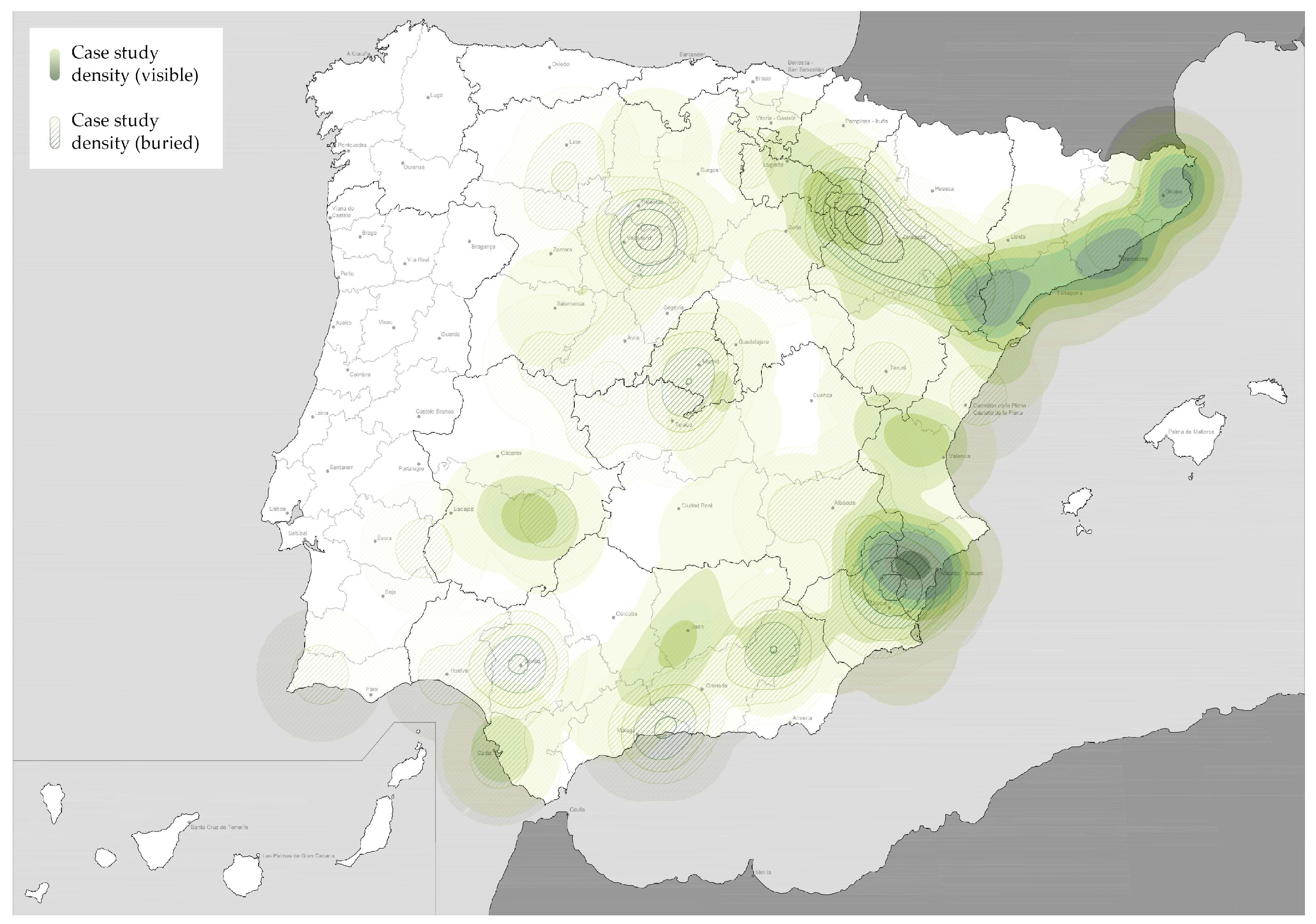

3.1.1. Geographical Distribution

3.1.2. Urban Location

3.1.3. Typology

3.1.4. Ownership

3.1.5. Use

3.1.6. Historical Period

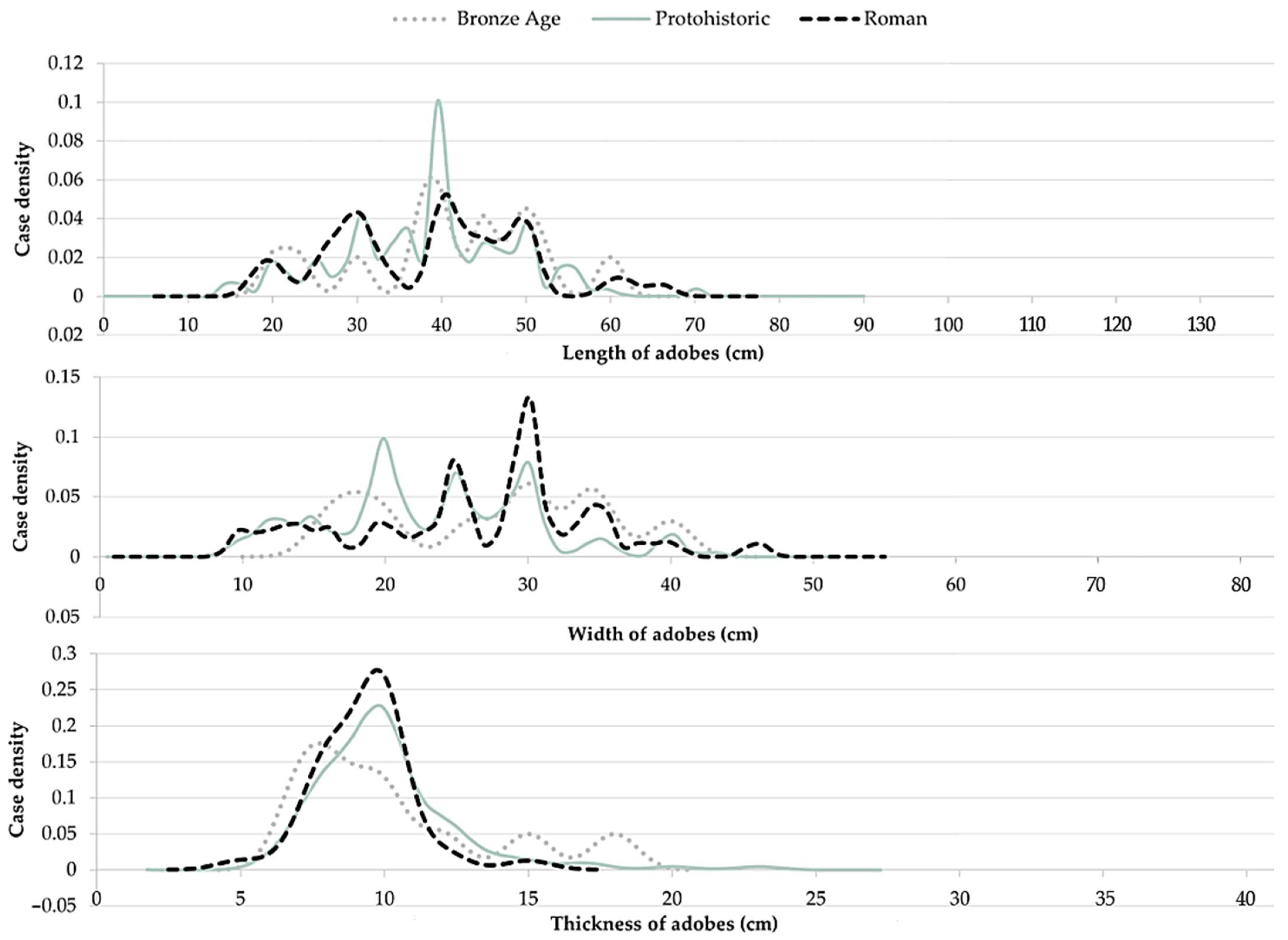

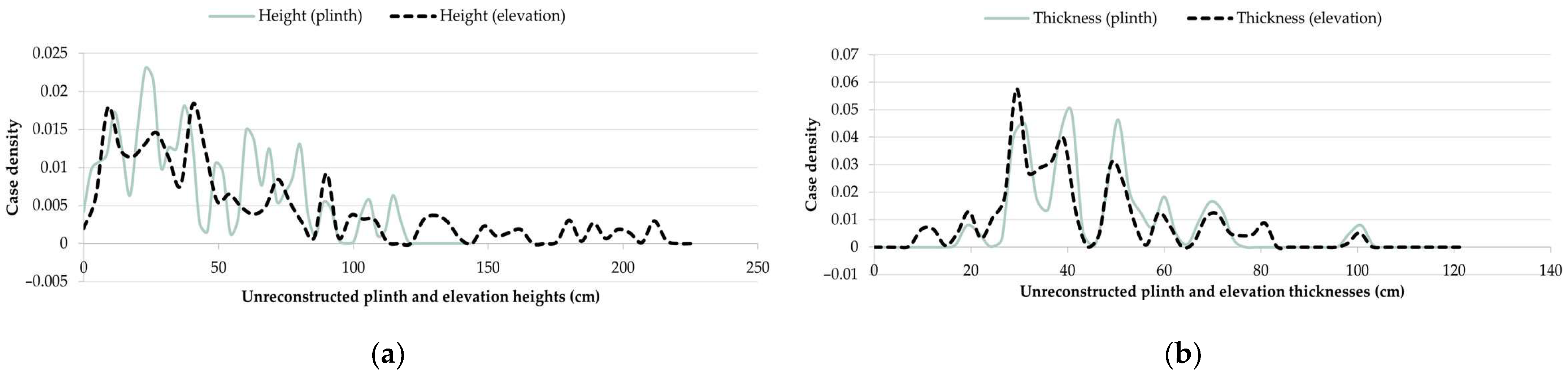

3.2. Architectural and Construction Characteristics

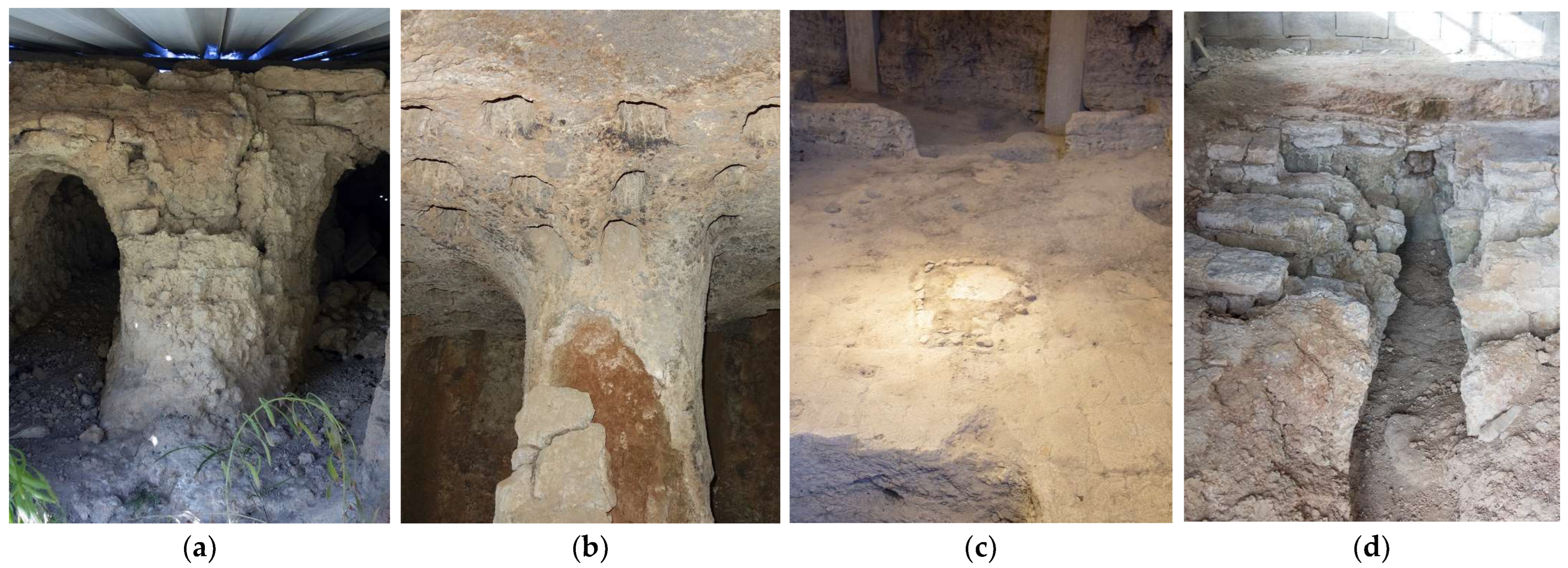

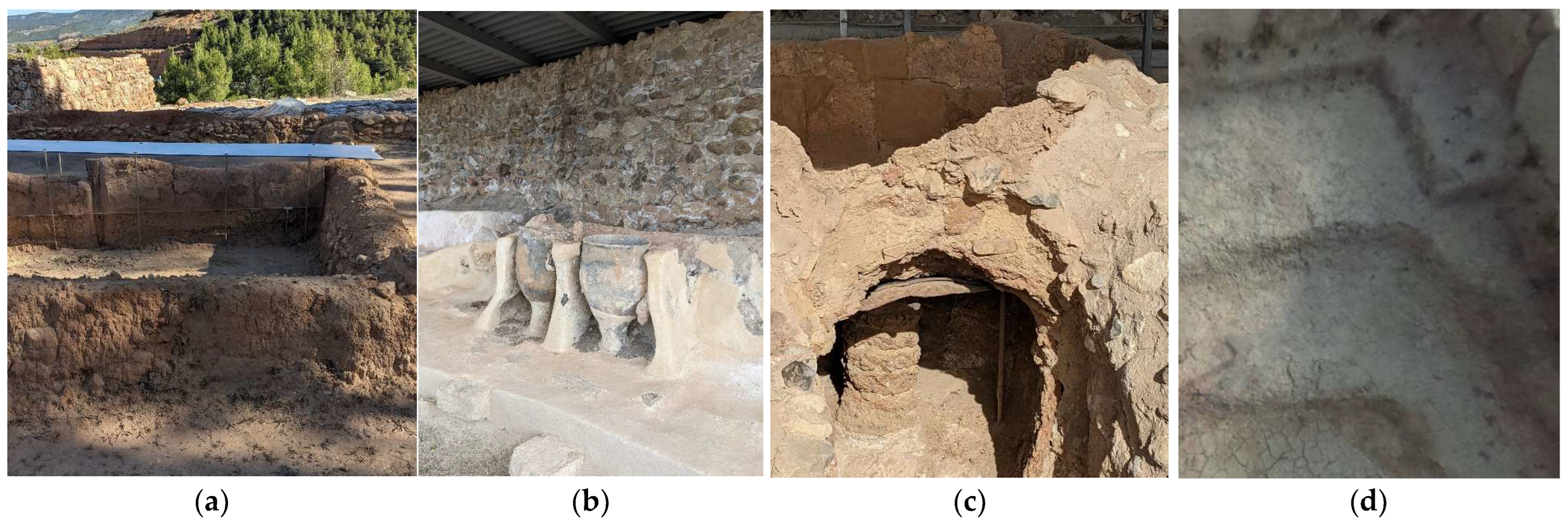

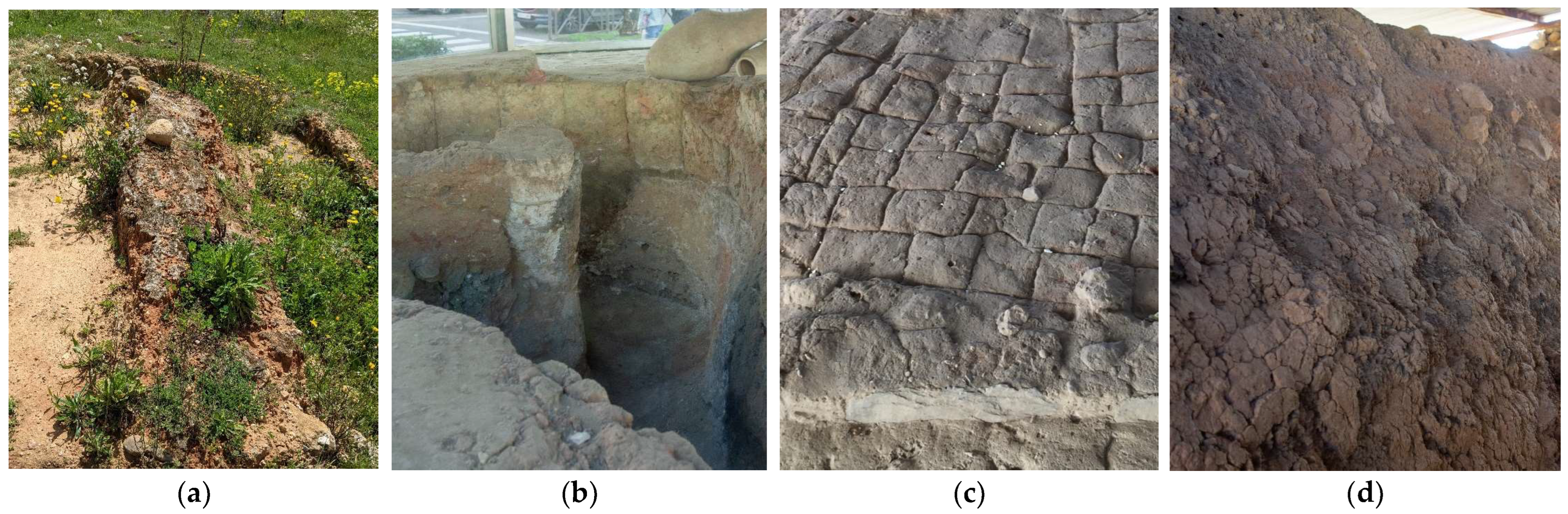

3.2.1. Presence of Earth

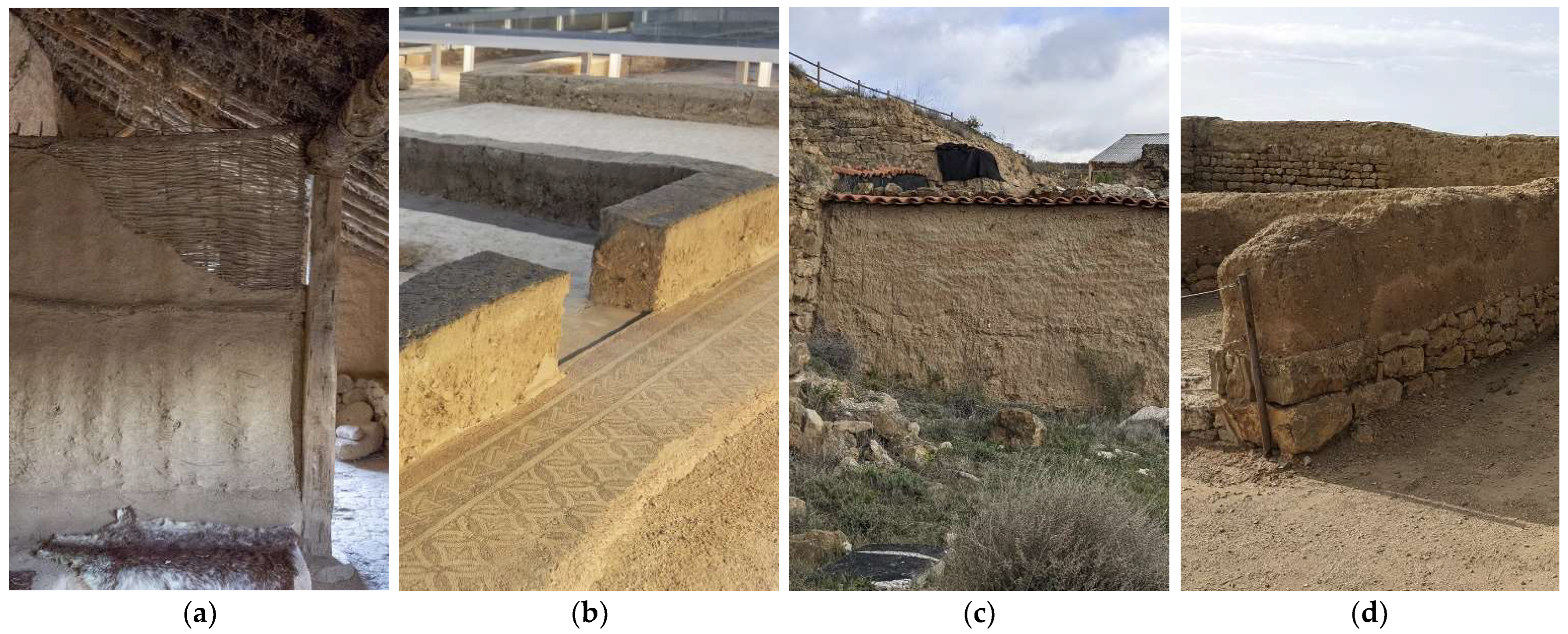

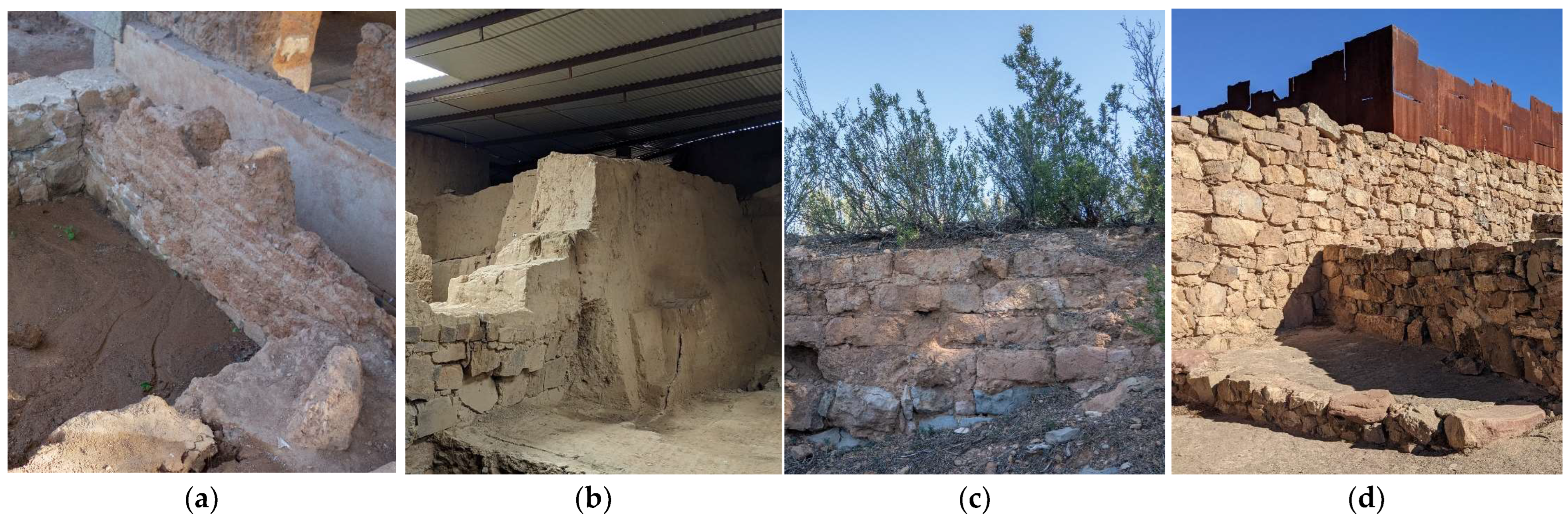

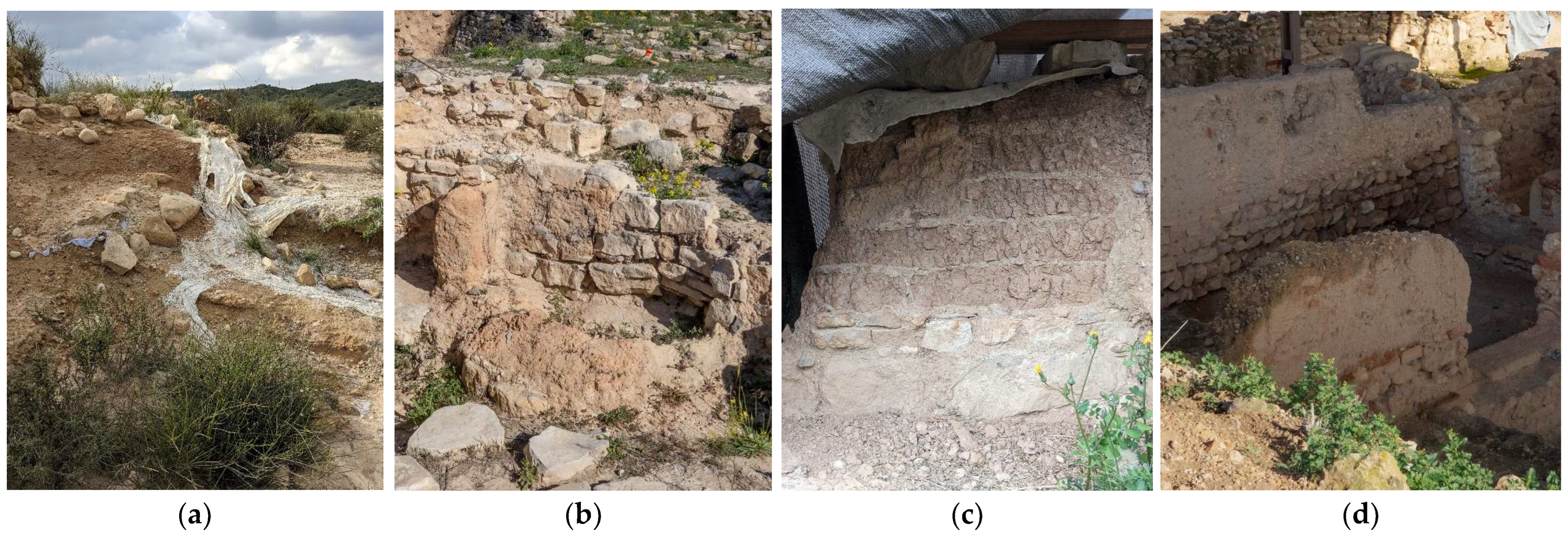

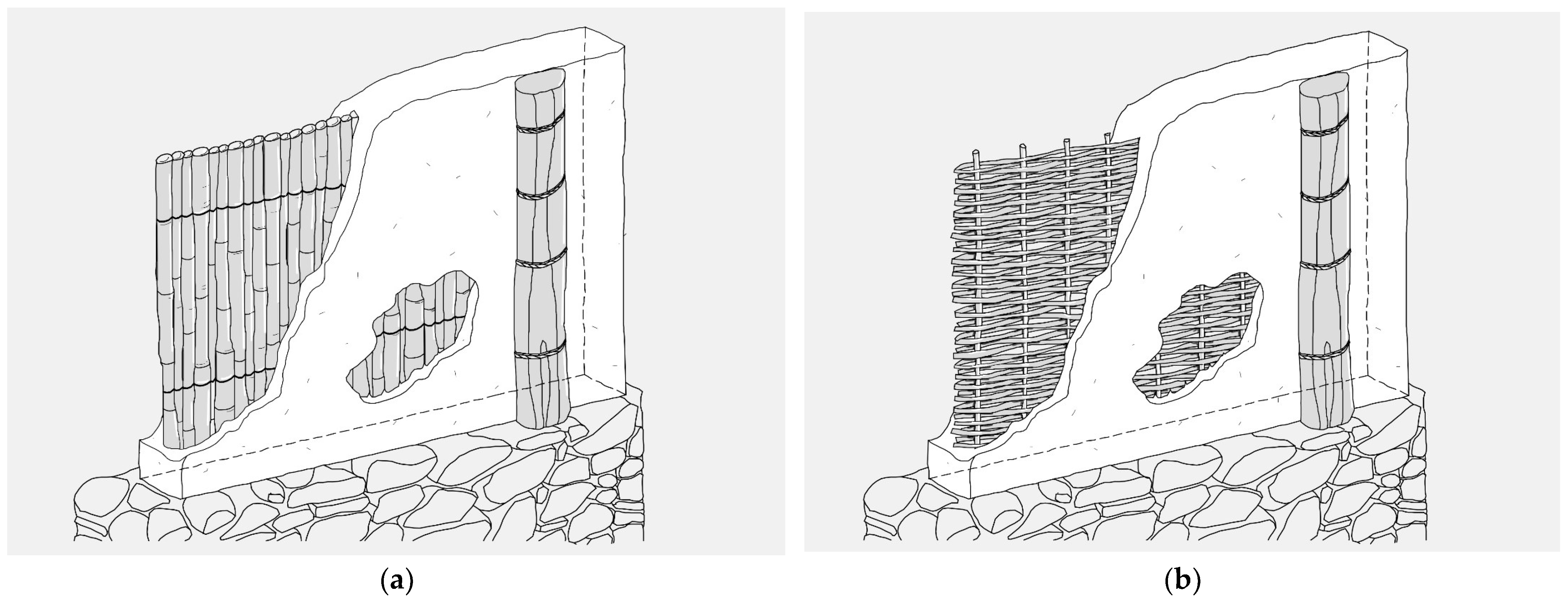

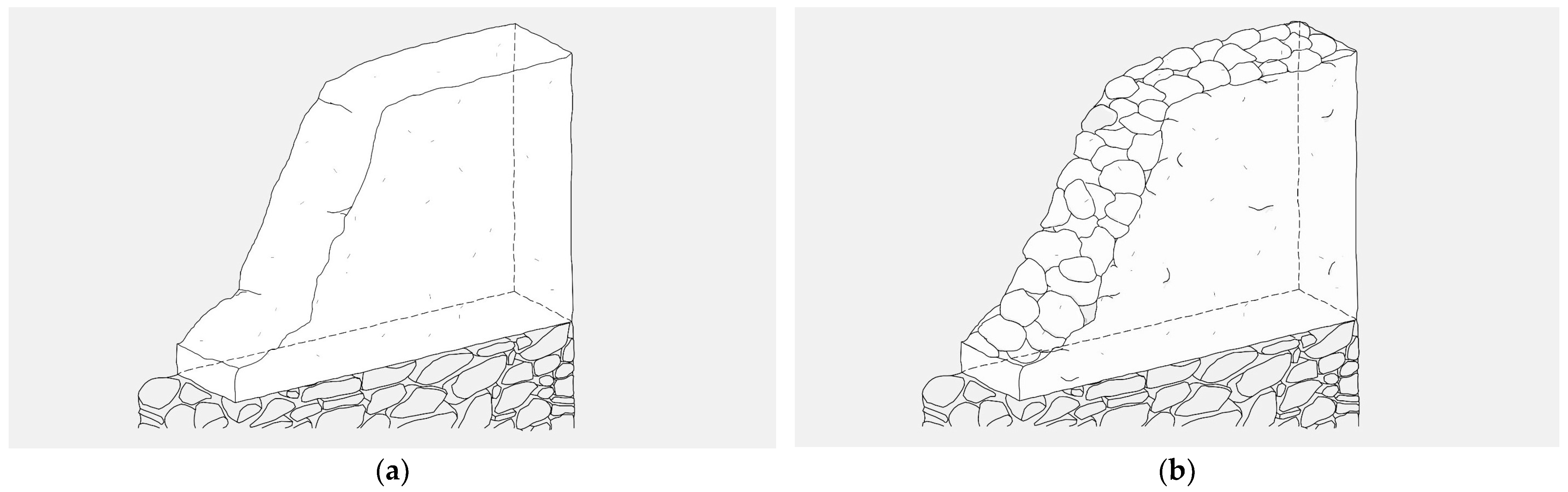

3.2.2. Construction Techniques

3.2.3. Stabilizing Agents

3.2.4. Complementary Techniques and Materials

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Selected Archaeological Sites as Case Studies

| Archaeological Site | Archaeological Site |

|---|---|

| 1. El Amarejo | 23. Horno Camp d’en Ventura de l’Oller |

| 2. Libisosa | 24. Doña Blanca |

| 3. Tossa de les Basses | 25. Horno de la Torrealta y Camposoto |

| 4. Tossal de Manises | 26. Puig de la Nau |

| 5. Peña Negra | 27. Orpesa la Vella |

| 6. Illeta dels Banyets | 28. Cerro de las cabezas |

| 7. El Arsenal | 29. Cerro de la Cruz |

| 8. Caramoro I | 30.Horno villa romana El Ruedo |

| 9. La Alcudia | 31. Turó Rodó |

| 10. El Monastil | 32. Mas Castellar |

| 11. La Fonteta | 33. Ampurias |

| 12. Rábita Califal | 34. Horno Clos Miquel |

| 13. El Oral | 35. Illa d’en Reixac |

| 14. Cabezo Redondo | 36. Cerro Santuario/Basti |

| 15. Los Millares | 37. Cerro Cepero/Basti |

| 16. La Mata | 38. Necrópolis de Tútugi |

| 17. Casas del Turuñuelo | 39. Castellón Alto |

| 18. Casa del Mitreo | 40. Cerro de la Virgen |

| 19. Cancho Roano | 41. Cástulo |

| 20. Domus Avinyó | 42. Vilars d’Arbeca |

| 21. Ca L’Arnau y Can Rodón | 43. Casa de los grifos |

| 22. Turó d’en Roïna/Can Taco | 44. Casa de Hippolytus |

| 45. El Molinete | 93. Castro de las Cogotas |

| 46. Medina Siyasa | 94. Turó de la Font de la Canya/ |

| 47. Coimbra del barranco ancho | 95. Turó del Font del Roure |

| 48. Villa de Los Cipreses | 96. Turó de la Florida Nord |

| 49. Mezquita cortijo del centeno | 97. Can Roqueta |

| 50. Villa romana de Los Torrejones | 98. Bòbila Madurell |

| 51. Villa Romana Piecordero I | 99. Horno Sant Vicenç dels Horts |

| 52. Alto de la Cruz | 100. Can Vinyalets |

| 53. Horno La Jericó | 101. Casa del Sótano-Rauda |

| 54. Villa romana La Olmeda | 102. Hornos La Milagrosa |

| 55. Cerro de San Vicente | 103. Torrelló de Boverot |

| 56. Numancia | 104. Vinarragell |

| 57. Moleta del Remei | 105. Mas d’Aragó |

| 58. Villa romana Els Munts | 106. Sitjar Baix |

| 59. Tossal del Moro | 107. C/Isabel Losa (Córdoba) |

| 60. Calvari el Molar | 108. Ercávica |

| 61. Horno de Fontscaldes | 109. Los Dornajos |

| 62. Coll del Moro | 110. Espinhaço de Cão |

| 63. Castellet de Banyoles | 111. Conjunto megalítico de Alcalar |

| 64. Turó del Calvari | 112. Ciudad ibérica Ullastret |

| 65. Ciutat Ibèrica de Calafell | 113. Alfar La Cartuja |

| 66. El Palao | 114. Cerro de La Encina |

| 67. Cabezo de Alcalá | 115. El Ceremeño |

| 68. La Caridad | 116. Castanheiro do Vento |

| 69. Hornos Mas de Moreno | 117. C/Ciudad de Aracena, 10 (Huelva) |

| 70. San Cristóbal | 118. Castellones del Ceal |

| 71. Plaza de los moros | 119. Puente Tablas |

| 72. La Celadilla | 120. La Cabrera |

| 73. Alquería de Bofilla | 121. Libia |

| 74. Castellet de Bernabé | 122. Hornos de Lancia |

| 75. Los Villares/Kelin | 123. Els Missatges |

| 76. Tossal de Sant Miquel-Edeta | 124. C/Hospital Viejo (Logroño) |

| 77. Bastida de les Alcusses | 125. El Pelícano |

| 78. Tos Pelat | 126. C/Santa Juana (Cubas de la Sagra) |

| 79. Lloma de Betxí | 127. Loranca (Fuenlabrada) |

| 80. Cerro de La Mota | 128. Cerro Redondo |

| 81. Soto de Medinilla | 129. Morro de Mezquitilla |

| 82. Contrebia Belaisca | 130. Horno de Arroyo Villalta |

| 83. Bílbilis | 131. Poblado de San Telmo |

| 84. Lépida Celsa | 132. Acinipo |

| 85. La Oruña | 133. Toscanos |

| 86. La Hoya | 134. Las Chorreras |

| 87. Alto de Castejón | 135. El Castellar |

| 88. La Casa Grande | 136. Cementerio islámico de San Nicolás |

| 89. Niuet | 137. Castejón de Arguedas |

| 90. Saladares | 138. El Castillo |

| 91. Necrópolis de Villaricos /Baria | 139. El Castillar |

| 92. Alfar La Rumina | 140. Vertabillo el Viejo Breto |

| 141. La Solana | 156. Tossal Montañés |

| 142. Alfar de Cauca | 157. Cerro de la Mesa |

| 143. Cuéllar (Cuéllar) | 158. La Alberquilla |

| 144. C/Juan de Ortega, 24 (Carmona) | 159. La Cervera |

| 145. Horno C/Montánchez, 4 (Carmona) | 160. Puntal dels Llops |

| 146. Hornos cerámicos de Orippo | 161. Las Quintanas/Pintia |

| 147. Cerro Macareno | 162. Castro El Pesadero |

| 148. Horno Pajar del Artillo | 163. Bursau |

| 149. Las Eras/Ciadueña | 164. Loma de los Brunos |

| 150. Casa del acueducto de Tiermes | 165. Cabezo de Monleón |

| 151. Sant Jaume | 166. Cabezo Muel |

| 152. Puig Roig | 167. El Calvario |

| 153. Barranc de la Premsa Cremada | 168. Cabezo de la Cruz |

| 154. Horno de l’Aumedina | 169. Los Castellazos |

| 155. Alto Chacón | 170. Caesaraugusta |

Appendix B. Metrics of Case Studies

| Archaeological Site | L | W | H | Source | Archaeological Site | L | W | H | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| El Amarejo | 30 | 20 | 10 | Broncano, 1985 [74] | Cerro de la Mota | - | 35 | - | Manzano, 2023 [17] |

| 40 | 30 | 8 | Broncano, 1985 [74] | 50 | - | - | Manzano, 2023 [17] | ||

| 45 * | 40 * | 8 * | Manzano, 2023 [17] | - | 15 | - | Manzano, 2023 [17] | ||

| Libisosa | 50 | 40 | 9 | Uroz et al., 2004 [75] | Soto de Medinilla | 38 ** | 19 ** | - | Arnaiz et al., 2017 [83] |

| 48 | 38 | 8 | Uroz et al., 2004 [75] | Contrebia Belaisca | 40 | 30 | 10 | Beltrán, 1981 [84] | |

| Tossa de les Basses | 50 ** | 30 ** | 8 ** | Rosser y Fuentes, 2007 [76] | 30 | 20 | 10 | Beltrán, 1982 [85] | |

| Tossal de Manises | 40 | 25 | 8 | Pérez, 2008 [77] | 50 | 30 | 8 | Beltrán, 1981 [84] | |

| 40 | 35 | 8 | Pérez, 2008 [77] | Bílbilis | 29 | 10 | 8 | Uribe, 2006 [8] | |

| 40 * | 30 * | 8 * | Manzano, 2023 [17] | 40 | 35 | 10 | Manzano, 2023 [17] | ||

| Peña Negra | 30 | - | 10 | González, 1983 [78] | Lépida Celsa | 31 | - | 10 | Beltrán, 1991a, b [86,87] |

| 40 * | 30 * | 8 * | Manzano, 2023 [17] | 26 | - | 7 | Beltrán, 1991a, b [86,87] | ||

| 38 * | 32 * | 9 * | Manzano, 2023 [17] | 45 | 30 | 10 | Manzano, 2023 [17] | ||

| Illeta dels Banyets | 40 | - | 10 | Olcina et al., 2009 [79] | La Hoya | 50 | 25 | 10 | Llanos, 1974 [88] |

| 55 * | 34 * | 9 * | Manzano, 2023 [17] | 30 | 20 | 10 | Llanos, 1974 [88] | ||

| La Alcudia | 19 | 14 | 9 | Ramos, 1983 [80] | La Casa Grande | 30 | 17 | 9 | Broncano et al., 1988 [89] |

| 50 * | 30 * | 12 * | Manzano, 2023 [17] | 36 | 22 | - | Broncano et al., 1988 [89] | ||

| El Monastil | 45 * | 30 * | 9 * | Manzano, 2023 [17] | Saladares | 35 ** | - | 8 ** | Arteaga et al., 1979 [90] |

| La Fonteta | 40 | 32 | 9 | Rouillard et al., 2007 [81] | Los Villaricos | 55 | 43 | 10 | Astruc, 1951 [91] |

| 55 | 30 | 9 | Rouillard et al., 2007 [81] | Castro de las Cogotas | 40 | 20 | 10 | Menéndez, 2010 [92] | |

| 36.5 | 28 | 9 | Rouillard et al., 2007 [81] | Bòbila Madurell | 30 | 21 | 17 | Miret, 1992 [93] | |

| El Oral | 30 | 20 | 10 | Abad et al., 1993 [37] | Casa del Sótano | 20 | 11 | 9 | Abarquero et al., 2012 [94] |

| 40 | 30 | - | Abad et al., 1993 [37] | 22 | 12 | 10 | Abarquero et al., 2012 [94] | ||

| 50 | 40 | - | Abad et al., 1993 [37] | Hornos La Milagrosa | 30 | 16 | 10 | Bernal et al., 2004 [35] | |

| La Mata | 38 | 19 | 10 | D74/2020, 2021 [82] | 21 | 12.5 | 10 | Bernal et al., 2004 [35] | |

| 50 | 25 | 12 | D74/2020, 2021 [82] | Vinarragell | 45 | 40 | 12 | Mesado et al., 1979 [95] | |

| 40 * | 20 * | 10 * | Manzano, 2023 [17] | 60 | 30 | 7 | Mesado, 1974 [96] | ||

| Casas del Turuñuelo | 40 | 20 | - | Rodríguez et al., 2017 [61] | C/Isabel Losa | - | 20 ** | 8 ** | Ruiz, 2003 [97] |

| 55 | 40 | 8 | Celestino et al., 2016 [53] | ||||||

| Cancho Roano | 48 | 35 | 9 | Celestino et al., 2016 [53] | Alfar La Cartuja | 25 | 14 | 10 | Moreno et al., 2017 [108] |

| 37 | 29 | 6 | Hernández et al., 2000 [55] | 27 | 16 | 12 | Moreno et al., 2017 [108] | ||

| 48 | 35 | 9 | Manzano, 2023 [17] | El Ceremeño | - | 15 | 10 | Cerdeño et al., 2002 [109] | |

| Domus Avinyó | 28 | - | 8 | Huertas, 2017 [98] | 32 | 22 | - | Cerdeño et al., 2002 [109] | |

| 20 | 12 | 9 | Vilardell, 2006 [99] | 20 | 20 | - | Cerdeño et al., 2002 [109] | ||

| Ca L’arnau/ Can Rodón | 42 ** | 29 ** | - | Martín, 2002 [100] | C/Ciudad de Aracena | 58 | 40 | 10 | Prera et al., 2003 [110] |

| Turó d’en Roina | 47 ** | 27 ** | 10 ** | Chorén et al., 2007 [101] | 32 | 20 | 10 | Prera et al., 2003 [110] | |

| 45 | 25 | - | Manzano, 2023 [17] | La Cabrera | 30 | 30 | 10 | Moreno et al., 1996 [63] | |

| Hornos Torrealta y Camposoto | 40 ** | 20 ** | 11 ** | Sáez, 2008 [102] | 62 | 33 | 8 | Moreno et al., 1996 [63] | |

| Puig de la Nau | 25 | 12 | 10 | Gusi et al., 1995 [103] | Libia | 40 | - | 9.5 | Marcos et al., 1979 [111] |

| 25 | 12 | 17 | Gusi et al., 1995 [103] | 31 | - | 10 | Marcos et al., 1979 [111] | ||

| 37 * | 28 * | 11 * | Manzano, 2023 [17] | Els missatges | 45 | 30 | - | Badias et al., 2002 [112] | |

| Orpesa la Vella | 40 | - | 10 | Gusi et al., 2014 [104] | 35 | 15 | - | Badias et al., 2002 [112] | |

| Cerro de las cabezas | 30 | 20 | 10 | Vélez et al., 1987 [105] | 25 | 14 | 12 | Badias et al., 2002 [112] | |

| 40 * | 20 * | 10 * | Manzano, 2023 [17] | C/Hospital Viejo | 60 | 30 | - | Martínez, 2013 [113] | |

| Cerro de la Cruz | 50 | 30 | 10 | Manzano, 2023 [17] | 40 | 28 | 15 | Martínez, 2013 [113] | |

| 41 | 34 | 10 | Vaquerizo et al., 1994 [106] | El Pelícano | 41 ** | 28 ** | 8 ** | Juan, 2013 [114] | |

| 26 | 19 | 12.5 | Vaquerizo et al., 1994 [106] | C/Santa Juana | 34 ** | 25 ** | - | Juan, 2013 [114] | |

| 35 | 32 | 8 | Vaquerizo et al., 1994 [106] | Loranca | 50 ** | 30 ** | - | Juan, 2013 [114] | |

| Horno El Ruedo | 66 | 33 | 7 | Muñiz, 2001 [33] | Cerro Redondo | 47 | 25 | 7.5 | Blasco et al., 1985 [115] |

| 30 | 10 | 5 | Muñiz, 2001 [33] | 40 | 30 | - | Blasco et al., 1985 [115] | ||

| 66 | 33 | 7 | Manzano, 2023 [17] | 55 | 25 | - | Blasco et al., 1985 [115] | ||

| Turó Rodó | 40 * | 22 * | 10 * | Manzano, 2023 [17] | Morro de Mezquitilla | 52 | 36 | 12 | Díes, 2001 [116] |

| Mas Castellar | 50 | 30 | - | Pons et al., 2016 [56] | 40 ** | - | - | Schubart, 1985 [117] | |

| 25 | 25 | 6.5 | Pons et al., 2016 [56] | Horno Arroyo Villalta | 33 | 30 | 10 | Fernández, 2010 [118] | |

| 35 | 25 | 9 | Pons et al., 2016 [56] | Toscanos | 40 | 20 | 12 | Díes, 2001 [116] | |

| Ampurias | 44 | 22 | 9 | De Chazelles, 1990 [42] | Las Chorreras | 20 | 12 | 3 | Aubet, 1974 [119] |

| Illa d’en Reixac | 35 ** | 25 ** | 8 ** | Martín et al., 1999 [107] | El Castellar | 50 | 35 | 18 | Ros, 1989 [120] |

| Cerro Cepero | 30 | 15 | 7 | Adroher, 2019 [121] | 48 | 28 | 10 | Ros, 1989 [120] | |

| 40 | 40 | - | Adroher, 2019 [121] | 40 | 22 | 10 | Ros, 1989 [120] | ||

| 45 | 30 | 7 | Adroher, 2019 [121] | Castejón de Arguedas | 40 | 19 | - | Castiella et al., 2002 [28] | |

| Necrópolis de Tútugi | 60 | 30 | 20 | Rodríguez, 2008 [26] | 50 | 27 | - | Castiella et al., 2002 [28] | |

| 40 | 30 | 10 | Rodríguez, 2008 [26] | 31 | 29 | 7 | Bienes, 1994 [130] | ||

| Cerro de la Virgen | 37.5 ** | 18 ** | - | Schüle et al., 1966 [122] | El Castillo | 40 ** | 30 ** | 8 ** | Faro et al., 2003 [58] |

| 20 ** | 20 ** | - | Schüle et al., 1966 [122] | El Castillar | 42.5 | 25.5 | 10 | Fonseca et al., 2021 [131] | |

| 28 * | 21 * | - | Manzano, 2023 [17] | 40 | 12 | 14 | Castiella, 1987 [132] | ||

| Cástulo | - | 50 | - | Manzano, 2023 [17] | 40 | 30 | 15 | Castiella, 1987 [132] | |

| - | 60 * | - | Manzano, 2023 [17] | Vertavillo el viejo Breto | 32 | 12.5 | 12.5 | Abarquero et al., 2006 [133] | |

| Vilars d’Arbeca | 39 ** | 20 ** | - | G.I.P, 2005 [123] | 20 | 13 | 11 | Abarquero et al., 2006 [133] | |

| 37 * | 35 * | 8 * | Manzano, 2023 [17] | 15 | 13 | 9 | Abarquero et al., 2006 [133] | ||

| Coimbra del barranco ancho | 40 | 20 | 10 | Molina et al., 1976 [124] | Alfar de Cauca | 44 | 19 | 8 | Blanco, 1992 [134] |

| 60 * | 40 * | 10 * | Manzano, 2023 [17] | 47 | 20 | 9 | Blanco, 1992 [134] | ||

| Piecordero I | 50 ** | 25 ** | - | Gómara et al., 2020 [125] | Cuéllar | 42 | 22 | 7.75 | Barrio, 1999 [135] |

| Alto de la Cruz | 40 | 20 | 10 | Maluquer et al., 1986 [62] | 28 | 14.5 | 8.5 | Barrio, 1999 [135] | |

| - | 28 | - | Maluquer et al., 1986 [62] | C/Juan de Ortega | 42 | - | 10 | Gómez, 2003 [136] | |

| - | 23 | 10 | Maluquer et al., 1986 [62] | 50 | - | 10 | Gómez, 2003 [136] | ||

| Horno La Jericó | 40 | 30 | 10 | Ayto. H. de Pisuerga, 2020 [126] | Horno C/Montánchez | 60 | 25 | 10 | Cardenete et al., 1991 [137] |

| - | 30 | 8 | Manzano, 2023 [17] | Cerro Macareno | 49 | 26 | 8 | Pellicer et al., 1983 [138] | |

| Cerro de San Vicente | 40 ** | 20 ** | - | Blanco et al., 2022 [22] | 52 | 34 | - | Pellicer et al., 1983 [138] | |

| 26 ** | 24 ** | - | Blanco et al., 2022 [22] | Horno Pajar del Artillo | 42 ** | 35 ** | 10 ** | Luzón, 1973 [36] | |

| Numancia | 40 | - | 12 | Mélida, 1908 [127] | Casa del acueducto | 47 | 23 | 8 | Argente et al., 1994 [139] |

| 45 | - | 12 | Mélida, 1908 [127] | 27 | 19 | 12 | Argente et al., 1994 [139] | ||

| 40 * | - | 9 * | Manzano, 2023 [17] | Horno de l’Aumedina | 30 | 22 | 10 | Pérez y Rams, 2010 [140] | |

| Moleta del Remei | 25 * | 25 * | 9 * | Manzano, 2023 [17] | Alto Chacón | 30 | 27 | 7 | Atrián, 1976 [141] |

| Els Munts | 50 ** | - | - | Tarrats, 1997 [128] | Tossal Montañes | 22 | 12.5 | 10 | Moret, 2001 [142] |

| Tossal del Moro | 36 | 22 | 13 | Arteaga et al., 1990 [129] | 22 | 10.5 | 8 | Moret, 2001 [142] | |

| 35 | 20 | 8 | Manzano, 2023 [17] | Cerro de la Mesa | 24 | 20 | 10 | Charro et al., 2009 [143] | |

| 45 | 28 | 9 | Manzano, 2023 [17] | 33 | 17 | 12 | Charro et al., 2009 [143] | ||

| Coll del Moro | 50 | 25 | 13 | Rafel et al., 1994 [18] | La Alberquilla | 47 | 27 | 8 | Gutiérrez et al., 2007 [144] |

| 40 | 14 | 14 | Rafel et al., 1994 [18] | 30 | 19 | 8 | Gutiérrez et al., 2007 [144] | ||

| Castellet de Banyoles | 55 ** | 28 ** | - | Sanmartí et al., 2012 [60] | 44 | 27 | 8 | Gutiérrez et al., 2007 [144] | |

| 35 | 25 | 10 | Vilaseca, 1949 [145] | La Cervera | 28 ** | 25 ** | 7 ** | López et al.,2013 [153] | |

| Turó del Calvari | 35 | 18 | 12 | Manzano, 2023 [17] | Puntal dels Llops | 40 | 30 | 9.5 | Bonet et al., 1984 [59] |

| Calafell | 48 | 24 | 10 | Pou et al., 1995 [146] | 30 | 20 | 10 | Bonet et al., 1984 [59] | |

| 30 * | 15 * | 8 * | Manzano, 2023 [17] | Las Quintanas/Pintia | 47 | 20 | 10 | Gómez et al., 1993 [154] | |

| El Palao | 38 | 28 | 9 | Melguizo et al., 2021 [147] | El Pesadero | 54 | 24 | - | Misiego et al., 2013 [155] |

| 40 * | 23 * | 8 * | Manzano, 2023 [17] | 44 | 21 | - | Misiego et al., 2013 [155] | ||

| Cabezo de Alcalá | 40 | 25 | 15 | Beltrán, 1976 [148] | 19 | 16 | - | Misiego et al., 2013 [155] | |

| La Caridad | 44 | 30 | 10 | Herce et al., 1991 [149] | Bursau | 30 | 30 | 15 | Royo et al., 1981 [156] |

| - | 30 * | - | Manzano, 2023 [17] | 40 | 20 | 10 | Royo et al., 1981 [156] | ||

| Mas de Moreno | 35 | 20 | 8 | Manzano, 2023 [17] | Loma de los Brunos | 16 | 9 | 7 | Eiroa, 1982 [157] |

| San Cristóbal | 36 | 22 | 9 | Fatás et al., 2005 [150] | Cabezo de Monleón | 38 ** | - | 7 ** | Beltrán, 1962 [158] |

| 46 | 17 | 17 | Fatás et al., 2005 [150] | 45 ** | - | 15 ** | Beltrán, 1962 [158] | ||

| 40 | 15 | 15 | Manzano, 2023 [17] | Cabezo Muel | 40 | 26 | 9 | Zapater et al., 1989 [159] | |

| Plaza de los moros | 28 * | 20 * | 9 * | Manzano, 2023 [17] | 33 | 15 | 10 | Zapater et al., 1989 [159] | |

| La Celadilla | 40 | 28 | 13 | Manzano, 2023 [17] | Cabezo de la Cruz | 31 | 20 | 10 | Picazo et al., 2009 [160] |

| Castellet de Bernabé | 45 | 33 | 10 | Guérin, 2003 [151] | 43 | 20 | 10 | Picazo et al., 2009 [160] | |

| 40 | 30 | 8 | Guérin, 2003 [151] | Los Castellazos | 15 | 10 | 8 | Maestro et al., 1991 [161] | |

| 40 * | 30 * | 10 * | Manzano, 2023 [17] | 45 | 25 | 10 | Maestro et al., 1991 [161] | ||

| Los Villares | 35 ** | 25 ** | 8 ** | Mata et al., 1991 [152] | Caesaraugusta | 50 | 30 | 10 | Galve, 1987-88 [162] |

| 40 * | 30 * | 9 * | Manzano, 2023 [17] | 18 | - | 10 | Galve, 1996 [163] | ||

| Tossal de Sant Miquel | 35 | 30 | 8 | Bonet, 1995 [57] | Bastida de les Alcusses | 40 | 30 | 10 | Bonet, 2011 [164] |

| 31 | 15 | 11 | Bonet, 1995 [57] | 35 | 25 | 12 | Fletcher et al., 1965 [165] | ||

| 27 | 20 | 10 | Bonet, 1995 [57] | 40 * | 30 * | 10 * | Manzano, 2023 [17] |

| Archaeological Site | L | W | H | Source | Archaeological Site | L | W | H | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rábita Califal | - | 37 | - | Manzano, 2023 [17] | Calafell | - | 50 | - | Manzano, 2023 [17] |

| Cerro de la Cruz | - | 70 ** | - | Manzano, 2023 [17] | La caridad | - | 46 | - | Herce et al., 1991 [149] |

| Ampurias | - | 50 | - | De Chazelles, 1990 [42] | Alquería de Bofilla | - | 47.5 | - | Manzano, 2023 [17] |

| - | 45 | - | Manzano, 2023 [17] | Los Dornajos | - | 100 ** | - | Galán, 2016 [166] | |

| Medina Siyasa | - | 80 | - | Navarro et al., 2011 [65] | Cementerio de San Nicolás | - | 45 ** | - | Navarro, 1985 [167] |

| - | 65 | - | Manzano, 2023 [17] | Casa de los grifos | - | 30 | - | Manzano, 2023 [17] | |

| - | 30 | - | Manzano, 2023 [17] | Libisosa | - | 40 ** | 45 ** | Uroz, 2006 [168] |

References

- Oliver, P. Encyclopedia of Vernacular Architecture of the World; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Rudofsky, B. Architecture without Architects: A Short Introduction to Non-Pedigreed Architecture; University of New Mexico Press: Albuquerque, NM, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Díes Cusí, E. Estudio Arqueológico de Estructuras: Léxico y Metodología; Colegio Oficial de Doctores y Licenciados en Filos: Valencia, Spain, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Jover Maestre, F.J.; Pastor Quiles, M. La Edificación Con Tierra Las Evidencias Constructivas En Galanet. In El Neolítico en el Bajo Vinalopó: (Alicante, España); Jover Maestre, F.J., Torregrosa Giménez, P., García Atiénzar, G., Eds.; British Archaeological Reports; Archaeopress: Alicante, Spain, 2014; pp. 209–215. [Google Scholar]

- Bruno, P.; Faria, P.; Candeias, A.; Mirao, J. Earth Mortars Use on Prehistoric Habitat Structures in Southern Portugal. J. Iber. Archaeol. 2010, 13, 51–67. [Google Scholar]

- Belarte Franco, M.C. L’utilisation de Brique Crue Dans Péninsule Ibérique Durant Protohistoire et Période Romaine; De De Chazelles, C.-A., Klein, A., Pousthomis, N., Eds.; Editions de l’Espérou: Montpellier, France, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Beltrán Lloris, M. La Casa Hispanorromana. Modelos. Bolskam 2003, 20, 13–63. [Google Scholar]

- Uribe Agudo, P. La Construcción Con Tierra En La Arquitectura Doméstica Romana Del Nordeste de La Península Ibérica. Salduie 2006, 6, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Soriano, L. La Restauración de Arquitectura de Tapia de 1980 a la Actualidad a Través de los Fondos del Ministerio de Cultura y del Ministerio de Fomento del Gobierno de España. Criterios, Técnicas y Resultados. Ph.D. Thesis, Universitat Politècnica de València, Valencia, Spain, 2015. Available online: https://riunet.upv.es/handle/10251/58607 (accessed on 23 June 2024).

- Manzano-Fernández, S.; Vegas López-Manzanares, F.; Mileto, C.; Cristini, V. Principles and Sustainable Perspectives in the Preservation of Earthen Architecture from the Past Societies of the Iberian Peninsula. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matero, F. Making Archaeological Sites: Conservation as Interpretation of an Excavated Past (2006); Sullivan, S., Mackay, R., Eds.; The Getty Conservation Institute: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez García, A. La Técnicas Constructivas Con Tierra En La Arqueología Prerromana Del País Valenciano. Quad. Prehist. Arqueol. Castelló 1999, 20, 161–188. [Google Scholar]

- Pastor Quiles, M. La Construcción con Tierra en Arqueología. Teoría, Método, Técnicas y Aplicación; Publicaciones de la Universidad de Alicante: Alicante, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sénépart, I.; Wattez, J.; Jallot, L.; Hamon, T.; Onfray, M. La Construction En Terre Crue Au Néolithique. Archeopages 2016, 42, 6–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daneels, A.; Romo de Vivar, A.; Chávez, L.; Reyes, M.; Tapia, E.; León, M.; Cienfuegos, E.; Otero, F.J. Bitumen-Stabilized Earthen Architecture: The Case of the Archaeological Site of La Joya, on the Mexican Gulf Coast. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2020, 34, 102619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzon, M.; Nitschke, J.L.; Littman, R.J.; Silverstein, J.E. Mudbricks, Construction Methods, and Stratigraphic Analysis: A Case Study at Tell Timai (Ancient Thmuis) in the Egyptian Delta. Am. J. Archaeol. 2020, 124, 105–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzano-Fernández, S. Arquitectura de Tierra Yacimientos Arqueológicos de Península Ibérica: Estudio de Riesgos Naturales, Sociales, Antrópicos y Estrategias de Intervención. Ph.D. Thesis, Universitat Politècnica de València, Valencia, Spain, 2023. Available online: https://riunet.upv.es/handle/10251/197994 (accessed on 23 June 2024).

- Rafel Fontanals, N.; Blasco Arasanz, M.; Sales Carbonell, J. Un Taller Ibérico de Tratamiento de Lino En El Coll Del Moro de Gandesa (Tarragona). Trab. Prehist. 1994, 51, 121–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asensio Vilaró, D.; Jornet Niella, R.; Miró Alaix, M.T.; Sanmartí Grego, J. L’excavació de La Zona 3 En El Castellet de Banyoles (Tivissa, Ribera d’Ebre), Un Nou Fragment de Trama Urbana En l’angle Sud-Oest de La Ciutat Ibèrica. In Actes de les I Jornades d’Arqueologia de les Terres de l’Ebre 2016.; Martínez, J., Diloli, J., Villalbí, M., Eds.; Generalitat de Catalunya, Departament de Cultura: Barcelona, Spain, 2016; pp. 330–342. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández Pérez, M.S.; García Atiénzar, G.; Barciela González, V. Cabezo Redondo; Universidad de Alicante: Villena, Spain, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Olcina Doménech, M.; Pérez Jiménez, R. Lucentum (Tossal de Manises, Alicante); Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes: Alicante, Spain, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Blanco González, A.; Padilla Fernández, J.J.; Alario García, C.; Macarro Alcalde, C.; Alarcón García, E.; Martín Seijo, M.; Chapon, L.; Iriarte, E.; Pazos García, R.; Sanjurjo Sánchez, J.; et al. Un Singular Ambiente Doméstico Del Hierro I En El Interior de La Península Ibérica: La Casa 1 Del Cerro de San Vicente (Salamanca, España). Trab. Prehist. 2022, 79, 346–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, V. Yacimiento Carpetano de Plaza de Moros. Available online: https://www.facebook.com/people/Yacimiento-Carpetano-de-Plaza-de-Moros/100063580448285/ (accessed on 3 March 2024).

- Hernández Pardos, A.; Franco Calvo, J.G. La Intervención Arqueológica En El Yacimiento Arqueológico de Lepida Celsa (Velilla de Ebro, Zaragoza) en 2002. Memorias Arqueol. Aragon. 2002, 2002, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Baza, C. Tour Virtual 360. Ciya Baza. Available online: https://www.ciyabaza.es/visitaVirtual/ (accessed on 3 March 2024).

- Rodríguez-Ariza, M.O.; Gómez Cabeza, F.; Montes Moya, E. El Túmulo 20 de La Necrópolis Ibérica de Tútugi (Galera, Granada). Trab. Prehist. 2008, 65, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faro Carballa, J.A.; Unzu Urmeneta, M. La Necrópolis de La Edad Del Hierro de El Castillo (Castejón, Navarra). Primeras Valoraciones: Campañas 2000–2002. Complutum 2006, 17, 145–166. [Google Scholar]

- Castiella Rodríguez, A.; Bienes Calvo, J.J. La Vida y La Muerte Durante La Protohistoria En El Castejón de Arguedas (Navarra). Cuad. Arqueol. Univ. Navarra 2002, 10, 7–216. [Google Scholar]

- García Vargas, E.; García Fernández, F.J. Los Hornos Alfareros de Tradición Fenicia En El Valle Del Guadalquivir y Su Perduración En Época Romana: Aspectos Tecnológicos y Sociales. SPAL Rev. Prehist. Arqueol. Univ. Sevilla 2012, 21, 9–39. [Google Scholar]

- Cuomo di Capio, N. Proposta Di Classificazione Delle Fornaci per Ceramica e Laterizi Nell’area Italiana, Dalla Preistoria a Tutta l’epoca Romana. Sibrium 1971, 11, 371–461. [Google Scholar]

- Marcos Herrán, F.J. Guía Turística de Herrera de Pisuerga. Un Paseo por su Historia; Centro de Iniciativas y Turismo de Herrera de Pisuerga: Herrera de Pisuerga, Spain, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gorgues, A.; Benavente Serrano, J.A. The Organisation of Work and Technology in the Late Iberian Potters’ Workshop of Mas de Moreno (Foz-Calanda, Teruel): A Provisional Asesment of the Research (2005–2011). In Iberos del Ebro. Actas del II Congreso Internacional (Alcañiz-Tivissa, 16–19 de Noviembre de 2011); Institut Català d’Arqueologia Clàssica (ICAC): Tarragona, Spain, 2012; pp. 273–290. [Google Scholar]

- Muñiz Jaén, I. Seguimiento Arqueológico En La Villa Romana de ‘El Ruedo’ (Almedinilla-Córdoba) II. Anu. Arqueol. Andalucía 1998 2001, 3, 215–223. [Google Scholar]

- Peidro Blanes, J. El Valle de Elda, de Los Romanos Al Final de La Antigüedad. In Elda, Arqueología y Museo: Ciclo Museos Municipales en el MARQ; Azuar Ruiz, R., Ed.; MARQ Museo Arqueológico Provincial de Alicante: Alicante, Spain, 2008; pp. 78–95. [Google Scholar]

- Bernal Casasola, D.; Díaz Rodríguez, J.J.; Expósito Álvarez, J.A.; Sáez Romero, A.M.; Lorenzo Martínez, L. Los Hornos Púnicos de Praefurnium Escalonado (Ss. III y II AC): Reflexiones a Raíz Del Alfar de La Milagrosa (San Fernando, Cádiz). In Figlinae Baeticae: Talleres Alfareros y Producciones Cerámicas en la Bética Romana (ss. II aC-VII dC): Actas del Congreso Internacional, Cádiz, 12–14 de Noviembre de 2003; Lagóstena Barrios, L.G., Bernal Casasola, D., Eds.; John W Hedges: Cádiz, Spain, 2004; pp. 607–620. [Google Scholar]

- Luzón Nogué, J.M. Excavaciones En Italica: Estratigrafia En El Pajar de Artillo. Excavaciones Arqueol. España 1973, 78, 17–19. [Google Scholar]

- Abad Casal, L.; Sala Sellés, F. El Poblado Ibérico de el Oral (San Fulgencio, Alicante); Diputación Provincial de Valencia, Servicio de Investigación Prehistórica: Valencia, Spain, 1993.

- Asensio Esteban, J.Á. Arquitectura de Tierra y Madera En La Protohistoria Del Valle Medio Del Ebro y Su Relación Con La Del Mediterráneo. Caesaraugusta 1995, 71, 23–56. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez del Cueto, F. Arquitecturas de Barro y Madera Prerromanas En El Occidente de Asturias: El Castro de Pendia. Arqueol. Arquit. 2012, 9, 83–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ruano Posada, L. La Arquitectura En Tierra En La Fachada Cantábrica Durante La Edad Del Hierro: Una Revisión de Materiales y Técnicas Constructivas Desde La Arqueometría y La Arqueología Virtual. Anejos Cuad. Prehist. Arqueol. 2021, 5, 217–243. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Geográfico Nacional. España En Mapas. Una Síntesis Geográfica; Centro Nacional de Información Geográfica, Ministerio de Fomento: Madrid, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Chazelles, C.-A. Les Constructions En Terre Crue d’Empúries a L’époque Romaine. Cypsela 1990, 8, 101–118. [Google Scholar]

- De Chazelles, C.-A.; Poupet, P. La Fouille Des Structures de Terre Crue. Définitions et Difficultés. Aquitania Une Rev. Inter-Rég. D’Archéol. 1985, 3, 149–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzano-Fernández, S.; Mileto, C.; Vegas, F.; Cristini, V. Construcción Con Tierra En Arqueología de España: Metodología de Estudio Para Análisis de Riesgos. In Seminario Iberoamericano de Arquitectura y Construcción con Tierra, 20. Memorias.; Ferreiro, A., Salcedo Gutiérrez, Z., Neves, C., Eds.; PROTERRA/Oficina del Conservador: Trinidad, Cuba, 2021; pp. 427–437. [Google Scholar]

- Craterre. La Roue Des Techniques. In Bâtir en Terre: Du Grain de Sable à L’architecture; Anger, R., Fontaine, L., Doat, P., Houben, H., Van Damme, H., Eds.; Belin, Cité des Sciences et de L’industrie: Paris, France, 2009; p. 26. [Google Scholar]

- Mileto, C.; Vegas, F. Proyecto COREMANS. Criterios de Intervención En La Arquitectura de Tierra; Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte: Madrid, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Knoll, F.; Pastor Quiles, M.; De Chazelles, C.-A.; Cooke, L. On Cob Balls, Adobe, and Daubeb Straw Plaits. A Glossary on Traditional Earth Building Techniques for Walls in Four Languages; Landesamt für Denkmalpflege und Archäologie Sachsen-Anhalt: Halle, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Manzano-Fernández, S.; Mileto, C.; Vegas López-Manzanares, F.; Cristini, V. Conservation and In Situ Enhancement of Earthen Architecture in Archaeological Sites: Social and Anthropic Risks in the Case Studies of the Iberian Peninsula. Heritage 2024, 7, 2239–2264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernabeu Aubán, J.; Pascual Benito, J.L.; Orozco Köhler, T.; Badal García, E.; Fumanal García, M.P.; García Puchol, O. Niuet (L’ Alqueria d’ Asnar). Poblado Del III Milenio a.C. Recer. Mus. d’Alcoi 1994, 3, 9–74. [Google Scholar]

- De Chazelles, C.-A.; De Poupet, P. L’emploi de La Terre Crue Dans l’habitat Gallo-Romain En Milieu Urbain: Nimes. Rev. Archéol. Narbonnaise 1984, 17, 71–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastor Quiles, M.; Jover Maestre, F.J.; Martínez Monleón, S.; López Padilla, J.A. La Construcción Mediante Amasado de Barro En Forma de Bolas de Caramoro I (Elche, Alicante): Identificación de Una Nueva Técnica Constructiva Con Tierra En Un Asentamiento Argárico. Cuad. Prehist. Arqueol. Univ. Auton. Madrid 2018, 44, 81–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Chazelles, C.-A. Les Origines de La Construction En Adobe En Extreme-Occident. In Sur les Pas des Grecs en Occident, Hommages à André Nickels; Nickels, A., Arcelin, P., Eds.; Errance: Paris, France, 1995; pp. 49–58. [Google Scholar]

- Celestino Pérez, S.; Rodríguez González, E.; Lapuente Martín, C. La Arquitectura En Adobe En Tarteso: El Turuñuelo de Gaureña (Badajoz), Un Ejemplo Excepcional Para El Conocimiento de Las Técnicas Constructivas. In Arquitectura en Tierra, Patrimonio Cultural: XII CIATTI 2015. Congreso Internacional de Arquitectura de Tierra, Tradición e Innovación; Jové Sandoval, F., Sainz Guerra, J.L., Eds.; Universidad de Valladolid, Cátedra Juan de Villanueva: Valladolid, Spain, 2016; pp. 41–50. [Google Scholar]

- Bonet Rosado, H.; Mata Parreño, C. El Puntal Dels Llops: Un Fortín Edetano; Diputación Provincial de Valencia, Servicio de Investigación Prehistórica: Valencia, Spain, 2002.

- Hernández Alfranca, F.; Anta Fernández, I.; Del Pozo González, M.V. Análisis de Los Sistemas Constructivos Del Palacio-Santuario de Cancho Roano (Zalamea de La Serena, Badajoz). In Actas del Tercer Congreso Nacional de Historia de la Construcción; Graciani García, A., Ed.; Instituto Juan Herrera: Madrid, Spain, 2000; pp. 501–506. [Google Scholar]

- Pons, E.; Asensio, D.; Morer, J.; Jornet, R. Un Edifici Singular Del Segle V AC Trobat Sota La Torre de Defensa de l’oppidum Ibèric (Mas Castellar-Pontós, Alt Empordà). Ann. L’Institut D’Estudis Empord. 2016, 47, 13–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonet Rosado, H. El Tossal de Sant Miquel de Llíria. La Antigua Edeta y Su Territorio; Diputación Provincial de Valencia: Valencia, Spain, 1995.

- Faro Carballa, J.A.; Cañada Palacio, F.; Unzu Urmeneta, M. Necrópolis de El Castillo (Castejón, Navarra): Primeras Valoraciones, Campañas 2000–2001–2002. Trab. Arqueol. Navarra 2003, 16, 45–77. [Google Scholar]

- Bonet Rosado, H.; Pastor Cubillo, I. Técnicas Constructivas y Organización Del Hábitat En El Poblado Ibérico de Puntal Dels Llops (Olocau, Valencia). Saguntum Papeles Lab. Arqueol. Val. 1984, 18, 163–188. [Google Scholar]

- Sanmartí Grego, J.; Asensio Vilaró, D.; Miró Alaix, M.T.; Jornet Niella, R. El Castellet de Banyoles (Tivissa): Una Ciudad Ibérica En El Curso Inferior Del Río Ebro. Arch. Español Arqueol. 2012, 85, 43–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez González, E.; Celestino Pérez, S. Las Estancias de Los Dioses: La Habitación 100 Del Yacimiento de Casas Del Turuñuelo (Guareña, Badajoz). Cuad. Prehist. Arqueol. Univ. Autónoma Madrid 2017, 43, 179–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Maluquer de Motes, J.; Gracia Alonso, F.; Munilla Cabrillana, G. Alto de La Cruz, Cortes (Navarra). Campaña 1986. Trab. Arqueol. Navarra 1986, 5, 111–132. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno Rosa, A.; Muñoz Jiménez, J. Intervención Arqueológica En El Trazado Del Gaseoducto Tarifa-Córdoba Por La Provincia de Jaén. Anu. Arqueol. Andalucía 1996, 2001, 270–284. [Google Scholar]

- Lancel, S.; Carrié, J.-M.; Deneauve, J.; Gros, P.; Sanviti, N.; Thuillier, J.-P.; Villedieu, F.; Saumagne, C. Mission Archéologique Française à Carthage. Byrsa I. Rapports Préliminaires Des Fouilles (1974–1976); Publications de l’École Française de Rome: Rome, Italy, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro Palazón, J.; Jiménez Castillo, P. Materiales y Técnicas Constructivas En La Murcia Andalusí (Siglos x-Xiii). Arqueol. Arquit. 2011, 8, 85–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Font, F.; Hidalgo, P. El Tapial: Una Tècnica Constructiva Millenària; Fermín Font i Mezquita i Pere Hidalgo i Chulio: Castellón, Spain, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Tarrats Bou, F.; Remolà Vallverdú, J.A. La Vil·la Romana Dels Munts (Altafulla, Tarragonès). Fòrum Temes D’Hist. I D’Arqueol. Tarragonines 2007, 13, 95–117. [Google Scholar]

- Azuar, R.; Rouillard, P.; Gailledrat, E.; Moret, P.; Sala Selles, F.; Badie, A. El Asentamiento Orientalizante e Ibérico Antiguo de ‘La Rábita’, Guardamar Del Segura (Alicante). Avance de Las Excavaciones 1996–1998. Trab. Prehist. 1998, 55, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mateu Sagués, M.; Bergadà, M.M.; Garcia i Rubert, D. Manufacturing Technical Differences Employing Raw Earth at the Protohistoric Site of Sant Jaume (Alcanar, Tarragona, Spain): Construction and Furniture Elements. Quat. Int. 2013, 315, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutillas-Victoria, B.; Lorenzon, M.; Yagüe, F.B. Earthen Architecture and Craft Practices of Early Iron Age Ramparts: Geoarchaeological Analysis of Villares de La Encarnación, South-Eastern Iberia. Open Archaeol. 2023, 9, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz Villarejo, A.J.; Gutiérrez Soler, L.M.; Alejo Armijo, M. Más Que Adobes. La Construcción Con Tierra Durante Los Siglos IV-III a.C. En El Área 11 de Giribaile (Vilches, Jaén). Lucentum 2019, 38, 171–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bizzarri, S.; Degli Esposti, M.; Careccia, C.; De Gennaro, T.; Tangheroni, E. Traditional Masonry and Archaeological Restoration. A Case Study from Salūt, Oman. Loggia, Arquit. Restauración 2021, 34, 46–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordóñez Martín, M.; Gómez de Cózar, J.C. Coberturas Sostenibles En Excavaciones Arqueológicas. Metodología de Aplicación Al Caso de Mosaicos En El Conjunto Arqueológico de Itálica (Santiponce, Sevilla). Ge-conservacion 2020, 17, 202–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broncano Rodríguez, S.; Blanquez Pérez, S. El Amarejo (Bonete, Albacete). Excavaciones Arqueol. España 1985, 139, 34–35. [Google Scholar]

- Uroz Sáez, J.; Molina Vidal, J.; Poveda Navarro, A.M.; Márquez Villora, J.C. Aproximación Al Conjunto Arqueológico y Monumental de Libisosa (Cerro Del Castillo, Lezuza, Albacete). In Investigaciones arqueológicas en Castilla la Mancha: 1996–2002; Junta de Comunidades de Castilla-La Mancha: Toledo, Spain, 2004; pp. 181–192. [Google Scholar]

- Rosser, P.; Fuentes, C. Tossal de Les Basses. Seis Mil Años de Historia de Alicante; Ayuntamiento de Alicante, Patronato Municipal de Cultura: Alicante, Spain, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez Jiménez, R. Restauración Arquitectónica y Conservación en Yacimientos Arqueológicos. F.R.A.C. (Fichas de Restauración Arquitectónica y Conservación); MARQ Museo Arqueológico Provincial de Alicante: Alicante, Spain, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- González Prats, A. Estudio Arqueológico del Poblamiento Antiguo de La Sierra de Crevillente (Alicante); Universidad de Alicante: Alicante, Spain, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Olcina Doménech, M.; Martínez Carmona, A.; Sala Sellés, F. La Illeta dels Banyets, (El Campello, Alicante): Épocas Ibérica y Romana I, Historia de la Investigación y Síntesis de Las Intervenciones Recientes (2000–2003); MARQ Museo Arqueológico Provincial de Alicante: Alicante, Spain, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos Fernández, R. Estratigrafía Del Sector 5-F de La Alcudia de Elche. Lucentum 1983, 2, 147–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouillard, P.; Gailledrat, É.; Sala Sellés, F. L’établissement Protohistorique de La Fonteta (Fin VIIIe—Fin VIe Siècle Av. J.-C.). Fouilles de la Rábita de Guardamar II; Casa de Velázquez: Madrid, Spain, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Decree 74/2020, of 9 December, Declaring the Archaeological Site of “La Mata” in the Municipal District of Cultural Interest of the Archaeological Site of “La Mata” in the Municipal District of Campanario (Badajoz), with the Category of Archaeological Zone. Boletín Oficial del Estado, 241. 8 October 2021. Available online: https://www.boe.es/diario_boe/txt.php?id=BOE-A-2021-16386 (accessed on 6 April 2024).

- Arnaiz Alonso, M.Á. La I Edad Del Hierro En La Cuenca Media Del Duero: Arquitectura Doméstica y Formas de Poder Político Durante La Facies Soto (Siglos IX-VII a.C.). Trab. Prehist. 2017, 74, 86–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltrán Martínez, A. Cabezo de Las Minas. Rev. Arqueol. 1981, 13, 8–17. [Google Scholar]

- Beltrán Martínez, A. El Gran Edificio de Adobe de Contrebia Belaisca. Boletín Mus. Zaragoza 1982, 1, 95–108. [Google Scholar]

- Beltrán Lloris, M. La Casa Urbana Hispanorromana. In La Casa Urbana Hispanorromana: Ponencias y Comunicaciones; Diputación Provincial de Zaragoza, Institución ‘Fernando el Católico’: Zaragoza, Spain, 1991; pp. 7–10. [Google Scholar]

- Beltrán Lloris, M. La Colonia Celsa. In La Casa Urbana Hispanorromana: Ponencias y Comunicaciones; Diputación Provincial de Zaragoza, Institución ‘Fernando el Católico’: Zaragoza, Spain, 1991; pp. 131–164. [Google Scholar]

- Llanos Ortiz de Landaluze, A. Urbanismo y Arquitectura En Poblados Alaveses de La Edad Del Hierro. Estud. Arqueol. Alavesa 1974, 6, 101–146. [Google Scholar]

- Broncano Rodríguez, S.; Coll Conesa, J. Horno de Cerámico Ibérico de La Casa Grande, Alcalá de Júcar (Albacete). Not. Arqueol. Hisp. 1988, 30, 187–228. [Google Scholar]

- Arteaga Matute, O.; Serna, M.R. Las Primeras Fases Del Poblado de Los Saladares (Orihuela, Alicante). Una Contribución Al Estudio Del Bronce Final En La Península Ibérica (Estudio Crítico 1). Empúries Rev. Món Clàss. Antig. Tardana 1979, 41–42, 65–137. [Google Scholar]

- Astruc, M. La Necrópolis de Villaricos; Ministerio de Educación Nacional, Comisaría General de Excavaciones Arqueológicas: Madrid, Spain, 1951; Volume 25. [Google Scholar]

- Menéndez Valderrey, J.L. Castro de Las Cogotas. Available online: https://www.asturnatura.com/turismo/castro-de-las-cogotas/3609.html (accessed on 22 June 2024).

- Miret Mestre, J. Bòbila Madurell 1987–88. Estudi Dels Tovots i Les Argiles Endurides Pel Foc. Arraona Rev. d’història 1992, 11, 67–72. [Google Scholar]

- Abarquero Moras, F.J.; Palomino Lázaro, Á.L. Arquitectura Doméstica y Mundo Simbólico En La Ciudad Vaccea de Rauda. In La ‘Casa Del Sótano’ En Las Eras de San Blas, Roa (Burgos); Academia Burgense de Historia y Bellas Artes, Institución Fernán González: Burgos, Spain, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Mesado Oliver, N.; Arteaga Matute, O. Vinarragell (Burriana, Castellón). II; Diputación Provincial de Valencia, Servicio de Investigación Prehistórica: Valencia, Spain, 1979.

- Mesado Oliver, N. Vinarragell (Burriana, Castellón); Diputación Provincial de Valencia, Servicio de Investigación Prehistórica: Valencia, Spain, 1974.

- Ruiz Nieto, E. Informe–Memoria de La Intervención Arqueológica de Urgencia En La C/Isabel Losa, Esquina a Plaza Ruiz de Alda, (Córdoba). Anu. Arqueol. Andalucía 2003, 3, 266–272. [Google Scholar]

- Huertas Arroyo, J.; Peña Cervantes, Y.; Miro Alaix, C. La Panadería de La Calle Avinyó y El Artesanado Tardorromano En La Ciudad de Barcino (Barcelona). SPAL Rev. Prehist. Arqueol. Univ. Sevilla 2017, 26, 237–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilardell Fernández, A. Memòria Conjunta de La Intervenció Arqueològica Del Carrer Avinyó Núm. 15 i Del Carrer Pou Dolç Núm. 4 de Barcelona (Bercelonès); Barcelona, Spain. 2006. Available online: https://arxiu.arqueologiabarcelona.bcn.cat/memoria-conjunta-de-la-intervencio-arqueologica-del-carrer-avinyo-num-15-i-del-carrer-del-pou-dolc-num-4-de-barcelona-juny-2003-juny-2004 (accessed on 10 September 2024).

- Martín, A. El Conjunt Arqueològic de Ca l’Arnau (Cabrera de Mar, Maresme): Un Assentament Romano-Republicà. Trib. D’Arqueol. 2002, 1998–1999, 211–228. [Google Scholar]

- Chorén, J.; Mercado, M.; Rodrigo, E. El Jaciment de Can Tacó: Un Assentament Romà de Caràcter Excepcional Al Vallès Oriental. Ponències. Rev. Cent. D’Estudis Granollers 2007, 11, 57–76. [Google Scholar]

- Sáez Romero, A.M. La Producción Cerámica en Gadir en Época Tardopúnica (Siglos -III/-I); British Archaeological Reports International Series; Archaeopress: Oxford, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Gusi Jener, F.; Oliver Foix, A.; Gómez Bellard, F.; Arenal, I.; Pérez-Pérez, A.; Valdés, L.; Cubero, C.; López de Roma, M.T.; Burjachs, F.; Castaños Ugarte, P.; et al. El Puig de la Nau: Un Hábitat Fortificado Ibérico en el Ámbito Mediterráneo Peninsular; Diputació de Castelló: Castellón, Spain, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Gusi Jener, F.; Olària Puyoles, C. Un Asentamiento Fortificado del Bronce Medio y Bronce Final en El Litoral Mediterráneo: Orpesa la Vella (Orpesa Del Mar, Castellón, España); Diputació de Castelló, Servei d’Investigacions Arqueològiques i Prehistòriques: Castellón, Spain, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Vélez Rivas, J.; Pérez Avilés, J.J. El Yacimiento Protohistórico Del Cerro de Las Cabezas (Valdepeñas, Ciudad Real). Oretum 1987, 3, 167–196. [Google Scholar]

- Vaquerizo Gil, D.; Quesada Sanz, F.; Murillo Redondo, J.F. Unidades de Hábitat y Técnicas Constructivas En El Yacimiento Ibérico Del Cerro de La Cruz (Almedinilla, Córdoba). An. Arqueol. Cordobesa 1994, 5, 61–98. [Google Scholar]

- Martín, A.; Buxó, R.; López, J.B.; Mataró, M. Excavacions Arqueològiques a l’Illa d’en Reixac (1987–1992); Generalitat de Catalunya, Departament de Cultura: Ullastret, Spain, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno Pérez, A.S.; Orfila Pons, M. El Complejo Alfarero Romano de Cartuja (Granada). Nuevos Datos a Partir de Las Actuaciones Arqueológicas Desarrolladas Entre 2013-2015. SPAL Rev. Prehist. Arqueol. Univ. Sevilla 2017, 26, 187–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerdeño, M.L.; Juez, P. El Castro Celtibérico de ‘El Ceremeño’ (Herreriía, Guadalajara). In Monografías Arqueológicas del Seminario de Arqueología y Etnología Turolense, 8; Junta de Comunidades de Castilla-La Mancha: Teruel, Spain, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Prera Ramírez, A.; Guerrero Chamero, O.; García Díaz, P.V.; Rodríguez Pujazón, R. Intervención Arqueológica de Urgencia En C/Ciudad de Aracena, No 10 Huelva. Anu. Arqueol. Andalucía 2003, 3, 535–542. [Google Scholar]

- Marcos Pous, A.; Castiella Rodríguez, A.; Molestina Zaldumbide, M.C. Trabajos Arqueológicos en la Libia de los Berones (Herramélluri, Logroño); Servicio de Cultura de la Excma; Diputación Provincial: Logroño, Spain, 1979.

- Badías, J.; Garcés Estalló, I.; Saula Briansó, O.; Solanes, E. El Camp de Sitges Ibèric de Missatges (Tàrrega, Urgell). Trib. D’Arqueol. 2002, 2001–2002, 143–166. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez González, M.M. La Producción Cerámica En La Baja Edad Mediael Alfar de La Calle Hospital Viejo de Logroño (La Rioja), Universidad de La Rioja. 2013. Available online: https://investigacion.unirioja.es/documentos/5c13b162c8914b6ed37766f8 (accessed on 20 May 2024).

- Juan Tovar, L.C.; Vázquez, J.S.; Baztán, P.O.; Cobo, E.P. Hornos Cerámicos Bajoimperiales y Tardoantiguos En El Sur de La Comunidad de Madrid: Presentación Prelimina. In Hornos, Talleres y Focos de Producción Alfarera en Hispania; Bernal Casasola, D., Juan Tovar, L.C., Bustamante Álvarez, M., Díaz Rodríguez, J.J., Eds.; Universidad de Cádiz, Ex Officina Hispana, Sociedad de Estudios de la Cerámica Antigua en Hispania (SECAH): Cádiz, Spain, 2013; pp. 421–437. [Google Scholar]

- Blasco Bosqued, M.C.; Alonso Sánchez, M.A. Cerro Redondo, Fuente El Saz Del Jarama, Madrid; Ministerio de Cultura, Dirección General de Bellas Artes y Archivos; Servicio Nacional de Arqueología y etnología: Madrid, Spain, 1985; Volume 143. [Google Scholar]

- Díes Cusí, E. La Influencia de La Arquitectura Fenicia En Las Arquitecturas Indígenas de La Península Ibérica (s. VIII-VII). In Arquitectura oriental y Orientalizante en la Península Ibérica; Ruiz Mata, D., Celestino Pérez, S., Eds.; Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, CSIC, Instituto de Historia: Madrid, Spain, 2001; pp. 69–122. [Google Scholar]

- Schubart, H. El Asentamiento Fenicio Del s. VIII AC En El Morro de Mezquitilla (Algarrobo, Málaga). Aula Orient. 1985, 3, 59–83. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández Rodríguez, L.E.; Romero Pérez, M.; Arcas Barranquero, A. El Complejo Alfarero Romano Del Arroyo Villalta, Bobadilla, Antequera (Málaga). Romula 2010, 9, 177–200. [Google Scholar]

- Aubet Semmler, M.E. Excavaciones En Las Chorreras (Mezquitilla, Málaga). Pyrenae 1974, 10, 79–108. [Google Scholar]

- Ros García, M.M. Dinámica Urbanística y Cultura Material del Hierro Antiguo en El Valle del Guadalentín; Universidad de Murcia: Murcia, Spain, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Adroher Auroux, A.M. Arquitectura en tierra en la Basti íbera. In SOS-Tierra: Restauración y Rehabilitación de la Arquitectura Tradicional de Tierra en la Península Ibérica; López-Manzanares, F.V., Mileto, C., Eds.; manuscript in preparation, submitted.

- Schüle, W.; Pellicer, M. El Cerro de La Virgen; Ministerio de Educación Nacional, Dirección General de Bellas Artes, Servicio Nacional de Excavaciones Arqueológicas: Madrid, Spain, 1966; Volume 46. [Google Scholar]

- Grup d’Investigació Prehistòrica. Dos Hogares Orientalizantes de La Fortaleza de Els Vilars (Arbeca, Lleida). In El Periodo Orientalizante. Protohistoria del Mediterráneo Occidental: Actas del III Simposio Internacional de Arqueología de Mérida; Jiménez Ávila, J., Celestino Pérez, S., Eds.; Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, CSIC: Mérida, Spain, 2005; pp. 651–668. [Google Scholar]

- Molina García, J.; Molina Gunde, M.; Nordstrom, S. Coimbra Del Baranco Ancho (Jumilla, Murcia); Diputación Provincial de Valencia, Servicio de Investigación Prehistórica: Valencia, Spain, 1976.

- Gómara Miramón, M.; Serrano Arnáez, B.; Bonilla Santander, Ó. Un Torcularium de Los Siglos I a.C.—I d.C. Del Yacimiento Romano Piecordero i (Cascante, Navarra). In Estudis Sobre Ceràmica i Arqueologia de L’arquitectura. Homenatge al Dr. Alberto López Mullor; Aquilué Abadías, J., Beltrán de Heredia, J., Caixal Mata, A., Fierro Macià, X., Kirchner, H., Eds.; Diputación Provincial de Barcelona: Barcelona, Spain, 2020; pp. 417–425. [Google Scholar]

- Ayuntamiento de Herrera de Pisuerga. Horno Cerámico Romano. Available online: https://herreradepisuerga.es/turismo/visitas/horno-ceramico-romano/ (accessed on 6 May 2024).

- Mélida Alinari, J.R. Excavaciones de Numancia; Tipografia de la Revista de Archivos, Bibliotecas y Museos: Madrid, Spain, 1908; pp. 1–69. [Google Scholar]

- Tarrats Bou, F.; Macias Solé, J.M.; Ramon Sariñena, E. Noves Intervencions a La Vil·la Romana Dels Munts (Altafulla, Tarragonès). Trib. D’Arqueol. 1997, 1996–1997, 35–56. [Google Scholar]

- Arteaga Matute, O.; Sanmartí Grego, E.; Padró Parcerisa, J. El Poblado Ibérico del Tossal Del Moro de Pinyeres (Batea, Terra Alta, Tarragona); Institut de Prehistòria i Arqueología: Barcelona, Spain, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Bienes Calvo, J.J. La Necrópolis Celta de Arguedas. Primeros Datos Sobre Las Campañas de Excavación de 1989–90. In Actas del III Congreso General de Historia de Navarra; Gobierno de Navarra: Pamplona, Spain, 1994; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca de la Torre, H.J.; Arróniz Pamplona, L.; Calvo Hernández, C.; Cañada Sirvent, L.; Meana Medio, L.; Bayer Rodríguez, X.; Pérez Legido, D. The Problematic Conservation of Adobe Walls in the Open-Air Site of El Castillar (Mendavia, Navarre, Spain). In Earthen Construction Technology: Proceedings of the XVIII UISPP World Congress; Daneels, A., Torras Freixa, M., Eds.; Achaeopress: Oxford, UK, 2021; pp. 109–117. [Google Scholar]

- Castiella Rodríguez, A. Aspectos Generales Del Poblado Protohistórico de El Castillar Mendavia (Navarra). Zephyrus Rev. Prehist. Arqueol. 1987, 39–40, 239–249. [Google Scholar]

- Abarquero Moras, F.J.; Palomino Lázaro, Á.L. Vertavillo, Primeras Excavaciones Arqueológicas En Un ‘Oppidum Vacceo’ Del Cerrato Palentino. Publicaciones Inst. Tello Téllez Men. 2006, 77, 31–116. [Google Scholar]

- Blanco García, J.F. El Complejo Alfarero Vacceo de Coca (Segovia). Rev. Arqueol. 1992, 13, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrio Martín, J. La II Edad Del Hierro En Segovia (España): Estudio Arqueológico Del Territorio y La Cultura Material de Los Pueblos Preromanos; British Archaeological Reports International Series; Archaeopress: Oxford, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez Saucedo, M.T. Intervención Arqueológica Preventiva En El Solar de c/Juan de Ortega No 24 de Carmona (Sevilla). Anu. Arqueol. Andalucía 2003, 3, 328–347. [Google Scholar]

- Cardenete López, R.; Gómez Saucedo, M.T.; Jiménez, A.; Lineros Romero, R.; Rodríguez, I. Excavaciones Arqueologicas de Urgencia En El Solar de La Calle Montánchez 4, Carmona, Sevilla. Anu. Arqueol. Andalucía 1989 1991, 3, 585–591. [Google Scholar]

- Pellicer Catalan, M.; Escacena Carrasco, J.L.; Bendala Galán, M. El Cerro Macareno; Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte: Madrid, Spain, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Argente Oliver, J.L.; Díaz Díaz, A. Tiermes IV. La Casa Del Acueducto: (Domus Alto Imperial de La Ciudad de Tiermes), Campañas 1979–1986; Ministerio de Cultura, Dirección General de Bellas Artes y Archivos, Instituto de Conservación y Restauración de Bienes Culturales: Madrid, Spain, 1994; Volume 167. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez Suñé, J.M.; Rams Folch, P. Memòria. Desmuntatge de Les Estructures Arqueològiques Del Jaciment de l’Aumedina Situades Al PK 20 + 500 de Ka Carretera C-44; Tortosa, Spain. 2010. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10687/425594 (accessed on 10 November 2022).

- Atrián Jordán, P. El Yacimiento Ibérico de Alto Chacón (Teruel). Campañas Realizadas En 1969-1970-1971 y 1972; Ministerio de Educación Nacional, Comisaría general de excavaciones arqueológicas: Madrid, Spain, 1976; Volume 92. [Google Scholar]

- Moret, P. El Tossal Montañés (Valdetormo, Teruel): Une Maison-Tour Ibérique Du VIe Siècle Av. J.-C. Madr. Mitteilungen 2001, 42, 85–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charro Lobato, C.; Chapa Brunet, T.; Pereira Sieso, J. Intervenciones Arqueológicas En El Cerro de La Mesa (Alcolea de Tajo, Toledo). Campañas 2005-2007. In Lusitanos y Vettones: Los Pueblos Prerromanos en la Actual Demarcación Beira Baixa, Alto Alentejo, Cáceres; Sanabria Marcos, P.J., Ed.; Junta de Extremadura, Consejería de Cultura: Cáceres, Spain, 2009; pp. 131–139. [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez Cuenca, E.; Muñoz Fernández, E.; Morlote Expósito, J.M.; Montes Barquín, R. El Horno de La Alberquilla: Un Centro Productor de Cerámica Carpetana En Toledo. Zo. Arqueol. 2007, 10, 303–323. [Google Scholar]

- Vilaseca, S.; Serra-Ràfols, J.C.; Brull Cedo, L. Excavaciones del Plan Nacional en El Castellet de Bañolas, de Tivisa (Tarragona); Ministerio de Educación Nacional, Comisaría General de Excavaciones Arqueológicas: Madrid, Spain, 1949; Volume 20. [Google Scholar]

- Pou Vallès, J.; Sanmartí Grego, J.; Santacana Mestre, J. La Reconstrucció Del Poblat Ibèric d’Alorda Park o de Les Toixoneres (Calafell, Baix Penedès). Trib. D’Arqueol. 1995, 1993–1994, 51–62. [Google Scholar]

- Melguizo Aísa, S.; Benavente Serrano, J.A.; Marco Simón, F.; Moret, P. El Área Oriental Del ‘Oppidum’ de El Palao (Alcañiz, Teruel). Campañas 2008-2011. Al-qannis Boletín Taller Arqueol. Alcañiz 2021, 14, 131–192. [Google Scholar]

- Beltrán Lloris, M. Arqueología e Historia de Las Ciudades Antiguas Del Cabezo de Alcalá de Azaila (Teruel); Librería General: Zaragoza, Spain, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Herce San Miguel, A.I.; Punter Gómez, M.P.; Vicente Redón, J.D.; Escriche Jaime, C. La Caridad (Caminreal, Teruel). In La Casa Urbana Hispanorromana: Ponencias y Comunicaciones; Diputación Provincial de Zaragoza, Institución ‘Fernando el Católico’: Zaragoza, Spain, 1991; pp. 81–130. [Google Scholar]

- Fatás Fernández, L.; Catalán Garzarán, S. La Construcción Con Tierra En La Protohistoria Del Bajo Aragón: El Caso de San Cristóbal de Mazaleón. Saldvie Estud. Prehist. Arqueol. 2005, 5, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guérin Fockedey, P.; Adelantado Lliso, P.; Calvo Gálvez, M.; Díes Cusí, E.; Grau Almero, E.; Iborra Eres, M.P.; Pérez Jórda, G.; Rovira Llorens, S.; Sabater Pérez, A.; Sáez Landete, A.; et al. El Castellet de Bernabé y El Horizonte Ibérico Pleno Edetano; Diputación Provincial de Valencia, Servicio de Investigación Prehistórica: Valencia, Spain, 2003.

- Mata Parreño, C. Los Villares (Caudete de Las Fuentes, Valencia): Origen y Evolución de La Cultura Ibérica; Diputación Provincial de Valencia, Servicio de Investigación Prehistórica: Valencia, Spain, 1991.

- López Serrano, D.; Valero Climent, A.; García Borja, P.; Rodríguez Traver, J.A.; Vives-Ferrándiz Sánchez, J. El Foso Ibérico de La Cervera (La Font de La Figuera, València). In El Naixement d’un Poble: Història i Arquelogia de La Font de la Figuera; García Borja, P., Revert Francés, E., Ribera, A., Biosca Cirujeda, V., Eds.; Ajuntament de la Font de la Figuera: La Font de la Figuera, Spain, 2013; pp. 93–104. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez Pérez, A.; Sanz Mínguez, C. El Poblado Vacceo de Las Quintanas, Padilla de Duero (Valladolid): Aproximación a Su Secuencia Estratigráfica. In Arqueología Vaccea. Estudios Sobre el Mundo Prerromano en la Cuenca Media del Duero; Romero Carnicero, F., Sanz Mínguez, C., Escudero Navarro, Z., Eds.; Junta de Castilla y León, Consejería de Cultura y Turismo: Valladolid, Spain, 1993; pp. 335–370. [Google Scholar]

- Misiego Tejeda, J.C.; Martín Carbajo, M.A.; Marcos Contreras, G.J.; Sanz García, F.J.; Pérez Rodríguez, F.J.; Doval Martínez, M.; Villanueva Martín, L.A.; Sandoval Rodríguez, A.M.; Redondo Martínez, R.; Ollero Cuesta, F.J.; et al. Las Excavaciones Arqueológicas en el Yacimiento de “La Corona/El Pesadero”, en Manganeses de La Polvorosa; Junta de Castilla y León, Consejería de Cultura y Turismo: Valladolid, Spain, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Royo, J.I.; Aguilera Aragón, I. Avance de La II Campaña de Excavaciones Arqueológicas En Bursau. 1979 (Borja, Zaragoza). Cuad. Estud. Borj. 1981, 7–8, 25–74. [Google Scholar]

- Eiroa García, J.J. Aspectos Urbanísticos Del Poblado Hallstáttico de La Loma de Los Brunos (Caspe, Zaragoza). Cuad. Investig. Hist. 1980, 6, 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Beltrán Martínez, A. Dos Notas Sobre El Poblado Hallstáttico Del Cabezo de Monleón: I. La Planta. II. Los Kernoi. Caesaraugusta 1962, 19–20, 149–150. [Google Scholar]

- Zapater Baselga, M.Á.; Navarro Chueca, F.J. ‘Cabezo de Muel’ (Escatrón, Zaragoza). Un Asentamiento Ibero-Romano En El Valle Medio Del Ebro; Campaña 1988. Cuad. Estud. Caspolinos 1989, 15, 323–370. [Google Scholar]

- Picazo Millán, J.V.; Rodanés Vicente, J.M. Los Poblados del Bronce Final y Primera Edad del Hierro: Cabezo de la Cruz, la Muela, Zaragoza; Gobierno de Aragón, Departamento de Educación, Cultura y Deporte: Zaragoza, Spain, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Maestro, E.; Tramullas, J. Estructuras Arquitectónicas En El Yacimiento de Los Castellazos, Mediana de Aragón (Zaragoza). In Simposi Internacional d’Arqueologia Ibèrica. Fortificacions, la problemàtica de l’Ibèric Plé: (segles IV-III a.C.); Centre d’Estudis del Bages: Manresa, Spain, 1991; pp. 233–239. [Google Scholar]

- Galve Izquierdo, M.P. Diario de Excavación de Los Solares de La Calle Predicadores 24–26, Unpublished.

- Galve Izquierdo, M.P. Los Antecedentes de Caesaraugusta: Estructuras Domésticas de Salduie (Calle Don Juan de Aragón, 9, Zaragoza); Institución Fernando el Católico: Zaragoza, Spain, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Bonet Rosado, H.; Vives-Ferrándiz Sánchez, J. La Bastida de Les Alcusses: 1928–2010; Diputación Provincial de Valencia: Valencia, Spain, 2011.

- Fletcher, D.; Pla, E.; Alcàcer, J. La Bastida de Les Alcuses (Mogente, Valencia); Diputación Provincial de Valencia, Servicio de Investigación Prehistórica: Valencia, Spain, 1965.

- Galán Saulnier, C. El Yacimiento Arqueológico de Los Dornajos (La Hinojosa, Cuenca); Arkatros: Madrid, Spain, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro Palazón, J. El Cementerio Islámico de San Nicolás de Murcia. Memoria Preliminar. In Actas del I Congreso de Arqueología Medieval Española, Huesca, 17, 18 y 19 de abril de 1985; Acín Fanlo, J.L., Ed.; Diputación General de Aragón, Departamento de Educación y Cultura: Zaragoza, Spain, 1986; pp. 7–37. [Google Scholar]

- Uroz Rodríguez, H. Libisosa. Historia Congelada; Istituto de Estudios Albacetenses ‘Don Juan Manuel’, Diputación de Albacete: Albacete, Spain, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Source | n | % | Source | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MUPREVA | 9 | 5% | Publications | 79 | 46% |

| MARQ | 2 | 1% | SOSTierra Research Project | 7 | 4% |

| IPCE-Map library | 10 | 6% | Calaix | 20 | 12% |

| IPCE-Projects | 17 | 10% | AAA-Anuario Arqueológico de Andalucía | 8 | 5% |

| IPCE-Photo library | 2 | 1% | EAE-Excavaciones Arqueológicas de España | 9 | 5% |

| IPCE-Inventory | 0 | 0% | NAH-Noticiario Arqueológico Hispánico | 14 | 8% |

| Characteristics | Earthen Construction Technique | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urban Location | All Techniques | Cob | Adobe | Rammed Earth | ||||

| Isolated | 117 | 68.8% | 21 | 12.4% | 101 | 59.4% | 17 | 10.0% |

| Urbanized plot | 36 | 21.2% | 8 | 4.7% | 33 | 19.4% | 4 | 2.3% |

| Built plot | 17 | 10.0% | 3 | 1.7% | 15 | 8.8% | 3 | 1.8% |

| Typology | All Techniques | Cob | Adobe | Rammed Earth | ||||

| Residential | 69 | 40.6% | 12 | 7.0% | 53 | 31.2% | 14 | 8.2% |

| Domestic | 56 | 32.9% | 14 | 8.2% | 36 | 21.2% | 7 | 4.1% |

| Productive | 42 | 24.7% | 6 | 3.5% | 38 | 22.4% | 0 | 0.0% |

| Funerary | 8 | 4.7% | 0 | 0.0% | 8 | 4.7% | 0 | 0.0% |

| Religious | 5 | 2.9% | 0 | 0.0% | 2 | 1.2% | 3 | 1.8% |

| Defensive | 4 | 2.4% | 0 | 0.0% | 4 | 2.4% | 0 | 0.0% |

| Ownership | All Techniques | Cob | Adobe | Rammed Earth | ||||

| Public | 109 | 64.1% | 17 | 10.0% | 95 | 55.9% | 18 | 10.5% |

| Private | 35 | 20.6% | 5 | 2.9% | 33 | 19.4% | 4 | 2.4% |

| Unknown | 28 | 16.5% | 10 | 5.9% | 23 | 13.5% | 2 | 1.2% |

| Use | All Techniques | Cob | Adobe | Rammed Earth | ||||

| Exhibition/cultural | 86 | 50.6% | 13 | 7.6% | 76 | 44.7% | 14 | 8.2% |

| Closed (under excavation) | 6 | 3.5% | 0 | 0.0% | 6 | 3.5% | 0 | 0.0% |

| Closed (buried) | 40 | 23.5% | 8 | 4.7% | 37 | 21.8% | 10 | 5.8% |

| Abandoned | 21 | 12.4% | 6 | 3.5% | 17 | 10.0% | 0 | 0.0% |

| Destroyed | 17 | 10.0% | 5 | 2.9% | 13 | 7.6% | 0 | 0.0% |

| Historical Period | All Techniques | Cob | Adobe | Rammed Earth | ||||

| Prehistoric | 28 | 16.5% | 13 | 7.6% | 17 | 10.0% | 1 | 0.6% |

| Protohistoric | 97 | 57.0% | 15 | 8.8% | 92 | 54.1% | 11 | 6.4% |

| Roman | 47 | 27.6% | 4 | 2.4% | 45 | 26.4% | 8 | 4.7% |

| Middle Ages | 9 | 5.3% | 0 | 0.0% | 7 | 4.1% | 4 | 2.3% |

| Construction Technique | Sites | Visible | Buried | Collapsed | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mixed techniques | 6 | 3.5% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 6 | 100.0% |

| Cob | 32 | 18.8% | 12 | 37.5% | 11 | 34.3% | 10 | 31.2% |

| Adobe | 149 | 87.6% | 68 | 45.6% | 55 | 36.9% | 41 | 27.5% |

| Rammed earth | 24 | 14.1% | 12 | 50.0% | 10 | 41.6% | 2 | 8.3% |

| Compacted earth pavements | 82 | 48.2% | 41 | 50.0% | 31 | 37.8% | 22 | 26.8% |

| Clay pavements | 27 | 15.8% | 11 | 40.7% | 9 | 33.3% | 9 | 33.3% |

| Unidentified | 1 | 0.6% | 1 | 100.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% |

| Presence of Earth | Sites | Cob | Adobe | Rammed Earth | ||||

| Wall elevations | 114 | 67.0% | 9 | 7.8% | 102 | 89.4% | 23 | 20.1% |

| Wall basing | 21 | 12.3% | 4 | 19.0% | 14 | 66.6% | 3 | 14.2% |

| Domestic elements | 84 | 49.4% | 18 | 21.4% | 71 | 84.5% | 1 | 1.2% |

| Production structures | 50 | 29.4% | 4 | 8.0% | 46 | 92.0% | 0 | 0.0% |

| Funerary structures | 12 | 7.0% | 2 | 16.6% | 10 | 83.3% | 0 | 0.0% |

| Pavements | 100 | 58.8% | 92 | 92.0% | 13 | 13.0% | 0 | 0.0% |

| Renderings | 61 | 35.8% | 58 | 95.1% | 3 | 4.9% | 0 | 0.0% |

| Stabilizing Agents | Sites | Cob | Adobe | Rammed Earth | ||||

| Plant | 20 | 11.7% | 5 | 25.0% | 16 | 80.0% | 4 | 20.0% |

| Lime | 4 | 2.3% | 1 | 25.0% | 3 | 75.0% | 1 | 25.0% |

| Ceramics | 3 | 1.7% | 0 | 0.0% | 2 | 100.0% | 1 | 33,3% |

| Gypsum | 1 | 0.6% | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 100.0% | 0 | 0.0% |

| Small stones | 4 | 2.3% | 1 | 33.3% | 2 | 66.6% | 1 | 33.3% |

| Carbons | 2 | 1.1% | 1 | 50.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 50.0% |

| No stabilizing agents | 1 | 0.6% | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 100.0% | 0 | 0.0% |

| Unknown | 141 | 82.9% | 23 | 16.3% | 127 | 90.0% | 21 | 14.8% |

| Complementary Techniques | Sites | Cob | Adobe | Rammed Earth | ||||

| Masonry | 147 | 86.4% | 6 | 4.1% | 128 | 87.0% | 16 | 10.8% |

| Fired brick | 15 | 8.8% | 1 | 6.6% | 10 | 66.6% | 4 | 26.6% |

| Flat stone or stone slabs | 11 | 6.4% | 0 | 0.0% | 10 | 90.9% | 1 | 9.0% |

| Ashlar | 8 | 4.7% | 0 | 0.0% | 8 | 100% | 0 | 0.0% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Manzano-Fernández, S.; Mileto, C.; Vegas López-Manzanares, F.; Cristini, V. Domestic and Productive Earthen Architecture Conserved In Situ in Archaeological Sites of the Iberian Peninsula. Heritage 2024, 7, 5174-5209. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage7090244

Manzano-Fernández S, Mileto C, Vegas López-Manzanares F, Cristini V. Domestic and Productive Earthen Architecture Conserved In Situ in Archaeological Sites of the Iberian Peninsula. Heritage. 2024; 7(9):5174-5209. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage7090244

Chicago/Turabian StyleManzano-Fernández, Sergio, Camilla Mileto, Fernando Vegas López-Manzanares, and Valentina Cristini. 2024. "Domestic and Productive Earthen Architecture Conserved In Situ in Archaeological Sites of the Iberian Peninsula" Heritage 7, no. 9: 5174-5209. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage7090244

APA StyleManzano-Fernández, S., Mileto, C., Vegas López-Manzanares, F., & Cristini, V. (2024). Domestic and Productive Earthen Architecture Conserved In Situ in Archaeological Sites of the Iberian Peninsula. Heritage, 7(9), 5174-5209. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage7090244