Abstract

The Sorrento Peninsula is characterized by a significant occurrence of examples of vernacular architecture, which exhibit distinctive morphological and constructive features. These have been the subject of numerous studies. However, some buildings have undergone a process of transformation over time, the details of which have yet to be investigated. Architectures that initially held a rural character were enlarged and ennobled, thereby becoming what could be termed as “villas of delights”. However, these clearly manifest their origin based on the permanence of some vernacular features. This paper focuses on the analysis of a case study, Villa Murat, which is exemplary in illustrating this process. This thorough interdisciplinary research combines historical investigation, based mainly on archival documents, with a direct examination of the Villa. This has enabled the retracing of the building’s evolution and of the events that occurred in it. An integrated survey, which employed photogrammetry and laser scanning, enabled the assessment of the current state of conservation. The ultimate objective of this research is to propose conservative interventions which, in conjunction with the suggested new intended use, could ensure the preservation of the Villa.

1. Introduction

Numerous examples of vernacular architecture are still preserved in the Sorrento Peninsula. This is due in part to the recognition of the historical and architectural significance of these structures, which has been supported by extensive research on the topic. Additionally, the innovative territorial plan, approved in 1987 with the coordination of Roberto Pane, a renowned architectural historian and expert on conservation, and Luigi Piccinato, one of the major town planners of the 20th century in Italy, provides specific protection measures for rural buildings, contributing to their continued preservation. Some vernacular buildings are still preserved, thanks to a continuity of the agricultural vocation of the area, or at least of some hamlets further from the centers that have undergone major transformations. Numerous well-known studies have been devoted to these examples [1,2,3] and to their typical constructive features, including typological studies and partial inventories [4].

Less well known, on the other hand, is the process that affected some buildings. These were born as rural houses inserted in agricultural funds and then transformed over the centuries by subsequent aggregation of volumes into more complex architectural forms. For a time, residential and agricultural functions coexisted in them, but then the status of aristocratic mansion prevailed in most cases. Thus, many rustic dwellings have been “ennobled”: floors have been added to organic systems, composed of cells with a Mediterranean character; the roofs have been transformed, the volumes regularized, and the surfaces decorated. The transformation of the buildings on a larger scale has led to changes in the identity of the surroundings, with social repercussions in a previously rural context. This later became a holiday destination for noblemen, and today is a place with a strong tourist vocation. Evidence of the roots of these architectures can be observed in the materials used, which belong to the local building tradition. Additionally, some morphological aspects, linked to the genesis of the buildings and to the functions they housed, and some recurring constructive features, such as arches, vaults, and loggias, can be recognized.

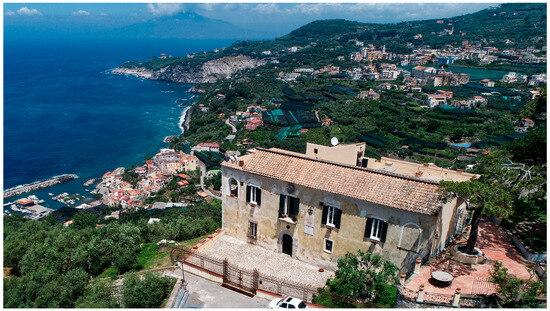

Villa Rossi, subsequently renamed Villa Murat, is situated within the Massa Lubrense municipality, at the extreme edge of the Sorrento Peninsula (Figure 1). This building has also undergone the aforementioned process of transformation. An initial nucleus, dating back to at least the 17th century, was expanded during the following century, with the addition of new volumes and the regularization of an initially spontaneous architecture. Despite such transformations, Villa Murat still retains some constructive features that are typical of vernacular architectures of the Sorrento and Amalfi coasts, such as extradosed vaults covered with a layer of beaten lapillus or loggias facing the sea. The villa intertwined major historical events at the beginning of the 19th century, having become the headquarters of king Gioacchino Murat—hence its name—during the “Capture of Capri” against the British in 1808. Since then, the villa has been preserved as a “villa of delights”, with no major alterations and as property of different owners who have succeeded each other over the past two centuries.

Figure 1.

Villa Murat with Vesuvius in the background. Photo taken by a drone (arch. M. Facchini).

2. Materials and Methods

Villa Murat is intended in this study as an illustrative example to investigate the process of transformation through which some vernacular architectures in the area have been “ennobled”. For this reason, following the numerous studies on this topic, in Section 3, the main characteristics of rural architectures located in the Sorrento peninsula and on the Amalfi coast are traced. Following an in-depth analysis of the case study, the objective is to ascertain the permanence of the constructive and morpho-typological characteristics that are typical of vernacular architecture.

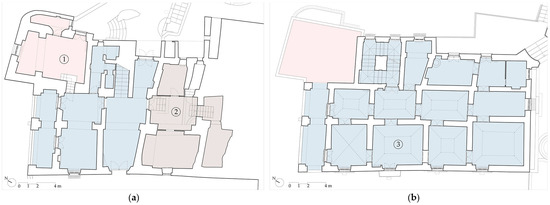

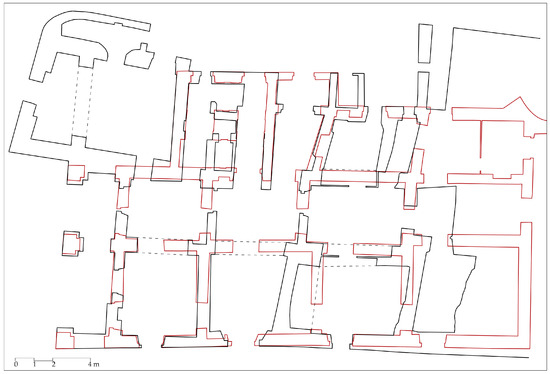

Indeed, starting from the first approach to the building, it was immediately evident that it was not the result of a unitary project but of the progressive expansion of previous structures. This seems clear when comparing the floor plans of the two levels that constitute the building today. Firstly, it can be assumed that the north-facing angular block belongs to a different construction phase from the rest of the building (n. 1 in Figure 2). In addition, the difference between the strongly irregular ground floor, with some rooms partially excavated in the rock (n. 2 in Figure 2), and the regularity of the upper floor, characterized by the typical row of rooms (n. 3 in Figure 2), is evident. Moreover, differences in the wall thickness are evident and may be due to different construction phases. Likely, more constructive phases could be identified by removing the plaster in some points and analyzing the masonry texture.

Figure 2.

(a) Ground floor plan of Villa Murat. (b) First floor plan. Different colors identify the assumed different constructive phases.

By comparing the historical information found in archival documents and direct analysis of the building, the evolution of Villa Murat over time was reconstructed, as discussed in Section 4. Information contained in Holy visits and Historical Land Registers provided the morphology of the building in different historical periods; more recent configurations were confirmed by historical views or photographs. At the same time, the transfers of ownership of the villa were traced to identify possible changes in the use of the building from which physical transformations can originate.

Bibliographical data about Murat’s stay in the villa was the starting point of this research, since it was the only previously known fact about the building. Based on old chronicles about the “Capture of Capri”, the owners of the villa at that time were identified, namely the Rossi family. Subsequently, a contemporary Land Register was analyzed, wherein an accurate description of the villa was identified among those pertaining to multiple properties owned by the Rossi family [5]. This initial description, which aligns with the current architectural characteristics of the villa, has already offered insights into the evolution of the building, including the identification of a second floor that was previously undocumented. The use of the same precise historical toponyms in several documents has made it possible to identify corresponding descriptions of the villa in other and older land registers. This enabled the reconstruction of the composition of the building in more distant times, as discussed in Section 5.

At the same time, the metric and material consistency, as well as the state of conservation, were analyzed thanks to an integrated survey employing both laser scanning and photogrammetry, as illustrated in Section 6. The metric accuracy of the instrumental survey made it possible to quantify deformations and differences in thickness in the stratigraphy of the structural elements, walls, and vaults. These are useful data not only for diagnosis of the state of conservation or for structural assessment but also for confirming hypotheses about the construction phases and transformations undergone by the building.

The final aim, as illustrated in Section 7, is to develop a conservative design proposal, with targeted actions for the conservation of architectural surfaces and structural strengthening. This will preserve the physical integrity of the villa without forfeiting possible but compatible enhancements.

3. Vernacular Architecture in the Sorrento Peninsula: Previous Studies, Constructive Features, and Protection Measures

The studies conducted on the rural houses of the Sorrento peninsula—and above all, on similar and even more well-known cases on the island of Capri or the Amalfi Coast—are extensive and well-established. Thanks to Giuseppe Pagano and Guarniero Daniel’s 1936 work [6], which was edited on the occasion of the sixth Triennale di Milano, the aesthetic and functional value of Italian rural houses with their different regional variations is recognized. The authors consider rural houses as a functional architecture whose morphology reflects the needs of the inhabitants and is therefore set as a reference for research on contemporary houses. The rural architectures in the Bay of Naples are illustrated as being the result of the aggregation of various cells [6] (pp. 38–47). Each cell has its roof, which consists of an extrados vault. The simplest units with a square plan have barrel or cloister vaults. More complex solutions, mainly cross vaults, are found in the case of cells with elongated rectangular plans and are more common in non-residential buildings. The authors also highlight how this type of roofing is useful for conveying rainwater; a fundamental aspect in areas that do not receive significant rainfall.

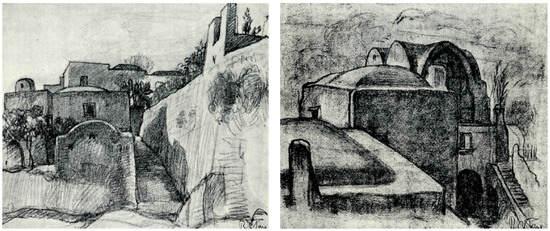

In the same year, 1936, Roberto Pane published his work Architettura Rurale Campana [1]. The Neapolitan scholar, who had already dedicated an early essay to the topic of rural dwellings, “case rustiche”, in 1928 [7], introduces the main constructive features of vernacular architecture in the area and highlights how this architecture is perfectly in tune with the natural environment in which it is built. The plastic values of this spontaneous architecture are perfectly described by the 53 drawings made by the author that Pane adds as a fundamental complement to the text (Figure 3). For Pane, it is worth studying rural houses not because they are a model to imitate, but to understand their values in order to protect them as well as to be inspired by their ability to adapt to the surrounding landscape [8]. Roberto Pane’s interest in rural architecture is expressed in numerous and not only written contributions. In 1955, he directed the documentary L’architettura della penisola sorrentina, for which he was awarded with the “Delfino d’Argento” at the Venice Film Festival. The voice-over accompanying the images effectively summarizes the distinctive aspects of rustic dwellings. In the same year, Pane published a volume devoted to the Sorrento coast, in which he once again focused on vaulted houses and their relationship with the environment. He emphasized the necessity for urban planning and protection efforts [9] (pp. 154–156), aspects on which he had begun to work actively and which would see him increasingly engaged in the following decades. The belief in the need to protect minor architecture heritage is also clearly expressed in the book devoted to Capri [2], where some of the most articulate examples of extradosed vaults are found. Here, Pane focuses even more on the types of vaults, their constructive and material features, and the construction processes. Among these, particular attention is paid to the process of making the typical covering layer of beaten lapillus and lime, for which he refers to in turn [10]. On the masonry vault, a layer of about 15 cm of lapillus, wet with lime milk, was spread. The beating lasted three days—until the cover became perfectly smooth and the thickness was reduced to about a third—and was carried out by a team of workers who used the mazzoccola, a particular wooden spatula.

Figure 3.

Rural houses in Capri. Drawings by Roberto Pane [1].

The rapid loss of rural architectural examples that was occurring during that period, as Pane denounces on several occasions (see [11]), prompted him to contribute increasingly actively to the definition of preservation measures.

The recognition of the rural architecture of the Sorrento and Amalfi peninsula as a heritage to be protected is due to the well-known Territorial Urban Plan (PUT), drawn up in the 1970s by a commission chaired by Roberto Pane and Luigi Piccinato and approved with some variants as Regional Law no.35 only in 1987 [12]. In the report attached to the plan, a specific paragraph is dedicated to “Rustic architecture with extrados vaults” [13] (pp. 107–108). The plan, especially in its first draft, regulates the permitted interventions: cement and plastic coverings must be avoided, as well as elevations of side walls, which interrupt the plastic continuity with the vaults. Moreover, the authors propose to catalogue and protect these minor architectures which, “happily well matched with the landscape” [1] (p. 16), contribute significantly to the image and identity of these places.

The suggestion to survey and catalogue examples of rustic architecture was received and developed in ref. [4], with reference to a portion of the Amalfi coast. Historical evolution starting from the medieval age, typological aspects, materials and processes of decay, and improper transformation are discussed. Moreover, recent studies have delved into constructive and material aspects, such as in ref. [3].

The primary distinctive characteristics of vernacular architecture in the Sorrento Peninsula can thus be summarized. These same attributes will also be evident in the case study that will be examined in this contribution.

From a volumetric point of view, this type of construction exemplifies the organic aggregation of various spatial units or cells, which have developed spontaneously starting from an initial nucleus. This process of growth is not pre-planned but rather driven by the evolving needs of its inhabitants. As new requirements arise, additional volumes are added to the structure, leading to a composition that is a direct manifestation of “pure and simple necessity” [1] (p. 7). The rural house, in this context, can be seen as a “living thing” that continuously “forms and transforms itself” [6] (p. 26) in accordance with changing needs. Unlike modern constructions that are often pre-designed with strict adherence to geometric precision and formal architectural rules, rustic dwellings evolve over time in a more organic and unstructured manner. Indeed, one of the most striking features of these rustic structures is their handmade quality. They are constructed without the use of rigorous geometry or precise measurements. Instead, they are built with a sense of approximation, guided by the skills of the builders rather than by exact plans. As stated by Roberto Pane, “this sense of approximation is perhaps the main reason of their picturesque” [1] (p. 7).

Roofs consist mainly of extrados vaults. These, like most of the typical features of rural architecture, developed simply due to their practicality. Indeed, the materials needed to build vaults—lime, lapillus, and stone—were more easily available compared to timber, which was used for flat or pitched roofs [1] (p. 9). Moreover, the vaulted shape was the most adequate to convey rainwater. The extrados of the vaults was coated, waterproofed, and thermally insulated with a layer of beaten lapillus and lime [3]. The most common vaults are barrel and cloister ones. The latter are often cut by a plane, providing an area “ideally assigned to a fresco” [2] (p. 25).

In the Sorrento peninsula, the houses are often located on hillsides and are therefore adapted to the difference in height of the ground, being partly built on the rock [1] (p. 14). To counteract the horizontal thrust of the vaults and avoid the rotation of the most vulnerable wall of the building—the one which covers the greatest difference in height—buttresses have been adopted since the Baroque age. By connecting these with arches and using the resulting floor as a terrace, loggias are obtained [4] (p. 138) and can still be found very often. Situated on slopes gradually descending towards the sea, loggias are frequently oriented towards the Gulf, offering protection from the sun and rain while providing a panoramic view.

Regarding building materials, masonry is made of local stones: gray tuff (more precisely called Campanian ignimbrite) and limestone, with more or less regular units of different sizes. Limestone quarried in the surrounding area is also employed for the production of lime used for mortar, as evidenced by the presence of numerous historical “calcare” (special kilns), especially on the Amalfi Coast. A particular kind of sandstone once quarried in Massa Lubrense is commonly used as slabs, mainly for floorings.

Perhaps among the most effective summary of the values conveyed by the rural architecture of the Sorrento Peninsula and Amalfi Coast, there is the one provided by Bruno Zevi: “Stupefying in its organicity, an almost plastic wrapping of arcane spaces, a house with a crossed barrel vault on the coast of Amalfi. […] It is an act of poetry” [14] (p. 15), highlighting (and he is not the only one) the poetical value of what is recognized instead as a dialectal or vernacular expression.

4. Villa Murat: Historical Events and Architectural Transformations

4.1. The Villa in Its Context

The municipality of Massa Lubrense is set at the extreme edge of the Sorrento peninsula and stands out for its polycentric settlement pattern. It does not have a real historical center but is made of numerous hamlets. Among them, there is Annunziata (Figure 4). This is located on a hill facing the island of Capri and was chosen as the most suitable place for the foundation of the Civitas Massae, a fortified citadel that has been destroyed and rebuilt several times. The fortifications that can still be seen today date back to the third castrum, built in the viceregal period, between the second half of the XVI century and the beginning of the XVII century, together with the coastal towers, to defend a territory that had been devastated by Saracen raids [15,16]. The first castrum, dating back to the Norman period, was destroyed by Charles I of Anjou around 1273. In 1389, the castle was rebuilt, then destroyed again by Ferrante d’Aragona in 1465.

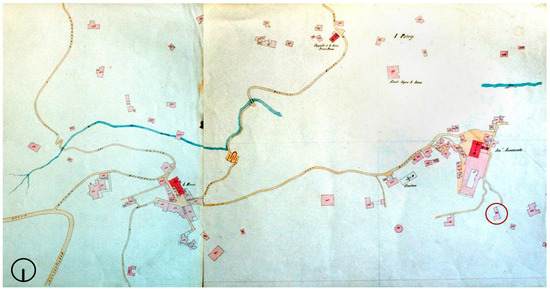

Figure 4.

(a) Reale Officio Topografico, Carta topografica e idrografica dei contorni di Napoli, 1817–19. The circle indicates the Annunziata hamlet. (b) Aerial view of the Annunziata hamlet with Villa Murat. The surviving parts of the XVI century fortification are highlighted with a continuous line. The hypothetical reconstruction is indicated with a dotted line.

Villa Murat stands along the path leading to the marina, immediately outside the viceregal enclosure and immersed in an agricultural estate from which the city once drew support (Figure 5). Following the cessation of maritime incursions and the subsequent elimination of defensive requirements, the viceregal citadel entered a gradual phase of decline. The walls were progressively incorporated into the building fabric, and the citadel became a quiet hilltop village, which still appears today as a timeless place, “unchanged for centuries” [9] (p. 146), in an exceptional landscape context, characterized by the stunning view on the island of Capri.

Figure 5.

Identification of Villa Murat in the 1882 Land Registry, which is the first one with cartographic representation of the territory of Massa Lubrense. The Annunziata hamlet is on the right; Villa Murat is identified with the red circle (Massa Lubrense Municipal Archive).

4.2. Villa Murat’s Evolution Based on Archival Documents

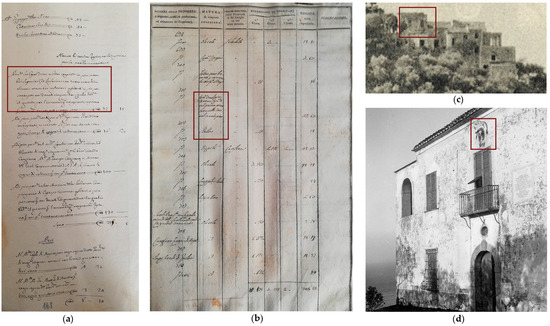

The historical investigation of the villa made use of different kinds of archival documents, including historical land registers (of which graphical reconstructions were made), holy visits, old photographs and paintings, and historical maps. It was thus possible to retrace the physical evolution of the building (previously known only for having hosted king Gioacchino Murat), the succession of owners, the expansions and demolitions that took place over the centuries, and the gradual transition from the agricultural vocation to that of a palatial residence.

The property on which Villa Murat stands, also consisting of an olive grove called Canfora overlooking Capri, was quoted, in the Holy Visit of Bishop Nepita of 1685 [17], among the properties of the Della Noce family. The recurrence of very precise toponyms, such as Canfora, made it possible to identify the description corresponding to the villa in the different documents. The Holy Visit; that is, the oldest document accessed, mentions only some rural structures located on the site. The Della Noce family still owned the entire extra moenia area of the Annunziata hamlet in 1742 when the Land registry (Catasto onciario) was drafted [18]. Among the assets of Giuseppe della Noce, who in those years was mayor of Massa Lubrense, there is a building corresponding to Villa Murat, described as “the house where he lives, consisting of several upper and lower members with all comforts”. Thus, the transformation of the first rural nucleus into a more complex house seems to have taken place between 1685 and 1742.

The subsequent owners were the Rossi family, who hosted Murat in 1808. The king chose this place as his headquarters during the so-called “Capture of Capri”, with which the French reclaimed the island, previously conquered by the English in 1806. The military operation began with a daring landing on 4 October 1808, which allowed the upper part of the island to be quickly conquered. However, a stalemate phase followed, during which the French were unable to break through the walls of Capri, where the English had taken refuge. It was during these days that the king moved to Massa Lubrense, where he could better follow the evolution of the battle. Despite the abundance of writings on the “Capture of Capri” (the most recent one is ref. [19]), the information relating to Murat’s stay in Massa Lubrense is lacking. Moreover, the few available data are often contradictory due to the isolation of Capri, which commenced on October 10th, as a result of a naval blockade imposed by the English. This blockade effectively cut off epistolary communication between the island and the mainland.

The date of Murat’s arrival is uncertain and fluctuates between October 10th and 14th. The king did not previously know the owners of the villa, who were even absent on his arrival. He simply chose the building because it offered the best view on the battle [20] (pp. 187–188). The stalemate ended on October 15th, when French fire succeeded in opening a hole in the walls of Capri. Difficult negotiations between the British and the sovereign followed, until Murat signed the capitulation on the night of October 16–17th, at the Rossi’s villa, from then on called “Villa Murat” (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

O. Fischetti, Gioacchino Murat, Re di Napoli, assiste alla presa di Capri da Massa Lubrense, 1809, Museo della Certosa di San Martino, Napoli. The main elevation of Villa Murat is accurately represented on the right.

The Rossi family is also mentioned as the owner of the villa in the land registry (Catasto provvisorio) of 1811 [5], where a meticulous description allows for a precise understanding of the villa’s architectural composition at that specific point in time. «\Andrea Rossi and his brothers from Naples owned numerous buildings in Massa Lubrense: a stable, which probably corresponds to the north-facing angular volume, identified as the initial nucleus of the villa, and “three rooms on the ground floor, eight rooms on the first floor, two small ones on the second floor”, which correspond to the remaining part of the villa. The current ground floor and first floor are consistent with what is described in this Land Register, which testifies to the existence of a second floor. This is also shown in some postcards from the early 20th century (Figure 7). Andrea Rossi also owned other buildings with an agricultural vocation, such as a rural house, another stable, and two trappeti (spaces devoted to oil production), in addition to the neighboring cultivated land, confirming that even in the 19th century, agricultural and residential usage coexisted in the villa and its surroundings.

Figure 7.

(a) Catasto onciario, vol. 171. Above is the composition of the Della Noce family, followed by a description of the property (highlighted by the rectangle). (b) Catasto Provvisorio. The parcels evidenced are those corresponding to the Villa. (c) Above, detail of a postcard from 1930s showing the second floor. (d) The main façade of Villa Murat in 1939, when the coat of arms of the Della Noce family was still visible.

In 1925, the villa was listed for its historical value according to the so-called “Rosadi law” no. 364 of 1909. Villa Murat has been almost unchanged since the 1940s, when the second floor was demolished.

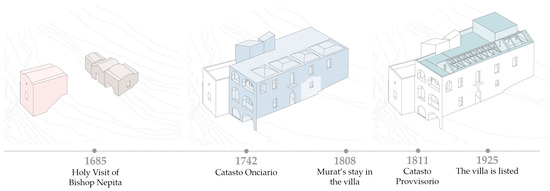

5. From Rural House to “Villa of Delights”: Morphological and Constructive Features

Information from archival documents supported the hypothesis that the villa was built in several phases (Figure 8). The evolution of the complex can be traced from its origins in rural architecture, as documented in the Holy Visit of 1685 [17], to its current form, as detailed in the Catasto Provvisorio [5]. This document records the existence of a second floor, which was subsequently demolished (Figure 7c). As the masonry texture is only visible in a few places, these hypotheses should be confirmed by further investigations. It is reasonable to assume that different construction phases correspond to different masonry textures in terms of the materials and dimensions of the elements. For instance, the discrepancy in the materials used for masonry on the ground floor and roof—grey tuff blocks and limestone, respectively—serves to corroborate the hypothesis that they belong to different periods.

Figure 8.

Constructive phases of the Villa, as supposed on the basis of the archival documents accessed and of the direct study of the building’s features. The same colors are used in Figure 2.

Nevertheless, the most effective method for understanding the transformation of this building from a vernacular structure to a villa is through direct observation of the building itself. A preliminary study of the floor plans allows for an initial reflection (Figure 2). The ground floor plan is irregular, indicating that multiple volumes, some of which remain recognizable, were lately incorporated into additional structures. The north-facing corner volume can be easily distinguished. It may correspond to the room that was registered as a stable in the 1811 Land Registry. This volume has its floors staggered by more than a meter compared to the rest of the building. Moreover, the walls have a different thickness, confirming that it belongs to a different construction phase, being evidently volumetrically autonomous (Figure 9). The southeast-facing rooms, on the other hand, are set against the garden embankment, partly dug into the rock following the different levels of the ground.

Figure 9.

Longitudinal section showing the staggered floors of the building.

This configuration may evoke the site’s initial agricultural use. Indeed, some spaces for agricultural functions were partially underground, as evidenced by the historical land registers, which record some trappeti in the property. The ground floor therefore retains a “handmade” character, comprising a number of irregular volumes. The first floor is characterized by a more regular layout, although some exceptions were necessary in order to accommodate to the preexisting structures underneath (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Overlapping of ground floor (in black) and first floor (in red) plans. The first floor is more regular, with some exceptions necessary to adapt to the lower structures.

The plan follows a somewhat diffuse pattern, comprising two rows of rooms. The main ones obviously face the front elevation, the back row corresponds to antechambers, while the service rooms are at the back. The complex spatial articulation is clearly visible when observing the back elevation, which, in contrast to the more regular main one, still allows the different volumes to be distinguished (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

(a) Back elevation of the Villa. (b) North elevation with loggias and angular volume identified as pre-dating the rest of the building.

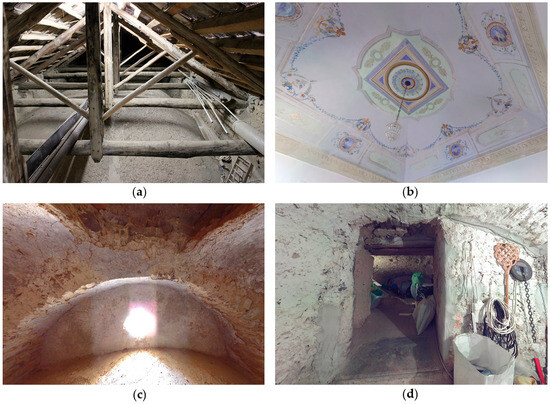

As previously stated, the primary architectural feature of rural houses on the Sorrento peninsula, specifically the extrados vaults, can also be observed in Villa Murat (Figure 12a). Although hidden at first glance by a double-pitched roof with wooden trusses added at a later date, they cover the rooms on the first floor and are clearly visible in the attic, where the historical finish in beaten lapillus is preserved. The addition of a pitched roof is a recurring transformation of this type of architecture. This certainly ensures even better waterproofing and rainwater runoff. Perhaps the addition of the roof is also an aesthetic choice, aimed precisely at concealing the rural appearance of the building.

Figure 12.

(a) Extrados vaults in the attic. (b) Intrados of one of the painted vaults of the first floor. (c) Extrados vaults in the mezzanine level. Here, the vault collapsed and the masonry in irregular stones of grey tuff is visible. The four-lobed window may recall a previous use of this volume, before it was incorporated into the villa. (d) Spaces partly carved into the rock on the ground floor.

Additionally, extradosed vaults are present on the two levels of the corner volume, where, following a collapse, the masonry in irregular ashlars of so-called grey tuff can be observed (Figure 12c).

Loggias are also a distinctive feature of the region’s architecture. When houses are placed on slopes, the loggias resolve the greatest difference in height. They are usually placed in such a way as to offer the most panoramic view and provide shaded and covered spaces. Moreover, they are usually not located on the main front to avoid introspection. At Villa Murat, the loggia appears as an added part to connect the pre-existing volumes. The loggias may, in fact, have been built at the same time as the first floor in order to insert the existing volumes into a more organic whole. Although loggias are very common in “nobler” examples of architecture, they are often also used in simple architectures because they offer shadowed spaces. They are a recurring feature of the region’s architecture, from rural examples to aristocratic dwellings. In Villa Murat, they are irregular and different in shape from each other, demonstrating that they are not the result of a design but rather an expression of a formal and functional requirement. Furthermore, they encompass the most comprehensive perspective, extending from the island of Capri to Vesuvius.

In the Massa Lubrense area and throughout the Sorrento peninsula, dwellings of this type are found in considerable numbers. These complexes are the result of the evolution of rural settlements, of which they retain, in a more-or-less evident way, the construction characteristics. Some of the structures still exhibit the distinctive spontaneous aggregation of volumes, while others have undergone extensions, frequently involving the addition of a residential floor to the original construction.

Villa Murat, unlike other buildings that retain a more modest character, enjoyed two significant advantages: it was among the possessions of a local nobleman, and it is situated in a privileged location that offers a magnificent panoramic view. This resulted in the villa being expanded and its interior spaces being decorated as a proper “villa of delights”.

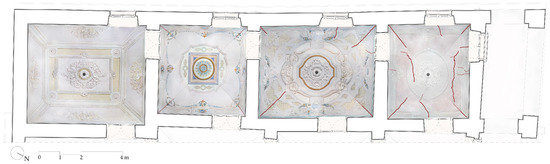

6. From the Villa to Its Model: Integrated Survey Process

This section presents the operational methodology employed for the survey of Villa Murat in Massa Lubrense. The purpose was to create documentation that would be useful for subsequent analysis and conservation projects. The objectives of the survey were established at the preliminary stage of the process in order to identify the most appropriate workflow. Firstly, the intention was to obtain a complete metric survey of the complex. This consists of a garden arranged on various terraces and a villa with an overhanging side, which was not detectable using direct survey procedures nor using a terrestrial laser scanner. High-resolution orthophotos of the exterior façades and painted interior vaults needed to be obtained as an essential basis for developing the surface conservation project [21,22].

In addition, one of the objectives was to detect the thicknesses of certain structural elements, such as the vaults, as well as any deformations and out-of-plumb vertical walls, which were necessary to evaluate possible structural strengthening measures [23,24,25].

Accordingly, a proven and reliable workflow was selected [26,27,28,29]. This was intended to be applicable not only to this case study but also in general to complexes with comparable operational challenges. The survey of this complex once again confirmed the necessity of integrating diverse surveying techniques based on the use of active sensors, such as laser scanners, and passive sensors, including both terrestrial and aerial-based cameras, with a topographical foundation to connect the different surveys.

6.1. Acquisition Phase

The acquisition phase, which was completed in two days, was preceded by a site visit with the objective of developing a survey plan. This entailed an investigation of the site and its context. An eidotype was prepared based on a previous survey in order to determine the optimal locations for the scans. These encompassed both the exterior and interior of the building, as well as the surrounding garden. Specific consideration was given to the acquisition of color data. The instrument’s camera was calibrated to ensure that the restitution of the painted surfaces was as homogeneous as possible. Checkerboards and Ringed Automated Detect (RAD) targets were arranged in order to facilitate the connection between the various levels of the villa and the exterior, as well as to ensure the overall georeferencing of the cloud. The meticulous planning of the survey enabled the optimal organization of the subsequent acquisition phase, during which the aerial photogrammetry survey was also conducted.

6.2. Image-Based and Range-Based Methodology

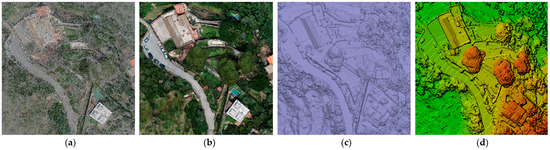

The survey campaign involved the acquisition of aerial images of the entire complex through the utilization of a Remotely Piloted Aircraft System (RPAS). The images were captured from both nadiral and oblique angles at a height of 30 m and an overlap and sidelap of 70%. The dataset consisted of 429 frames. The drone used was a DJI Phantom 4. Orthoprojections were obtained using a Ground Sample Distance (GSD) of 1.05 cm/px. The data were processed using the Agisoft Metashape photogrammetric modelling software. This software employs a range of sophisticated algorithms, including matching algorithms such as Scale Invariant Feature Transform (SIFT) and cloud densification algorithms such as Cluster Multi View Stereo (CMVS). The process enabled the reconstruction of the existing conditions through the generation of a three-dimensional model, which was employed as a survey instrument for the production of orthophoto plans and sections of the site (Figure 13).

Figure 13.

Elaboration phases of photogrammetric survey. (a) Sparse point cloud; (b) dense point cloud; (c) mesh model; (d) Digital Elevation Model (DEM).

Prior to the photographic acquisition with RPAS, a preliminary project was required. This was based on mapping of the area using Mission Planner, a software that allows for the creation of flight plans through the input of waypoints. The route, the number of shots, and the ground resolution values were thus defined. In order to ensure comprehensive coverage of the area to be surveyed, operational and environmental factors that could potentially impact the restitution process were taken into account.

For the laser scanner survey, aimed at the acquisition of the morphometric characteristics of the site, the Focus3D X330 model, a CAM2/Faro Terrestrial Laser Scanner (TLS), was used. Two methods were used for recording the scans: natural points and artificial targets. Particular attention was paid to the positioning of the checkerboard targets, which were necessary for joining the point clouds. Throughout the acquisition process, it was constantly verified that the same trio of targets was visible on consecutive pairs of scans.

A total of 169 scans were completed, with the selection of appropriate station points made with minimal occlusion (Figure 14). The resolution selected was 6136 mm, measured in a plane 10 m from the emitter, with 3× quality. Each scan lasted seven minutes. The acquired point clouds were recorded through collimation of the artificial targets, with a cloud-to-cloud process used for some parts that could not be directly reached. Following preprocessing, the registration phase of the individual scans started by establishing the initial scan and aligning all others to it. The roto-translation matrices between the different internal local systems were then applied in order to frame them in a global reference.

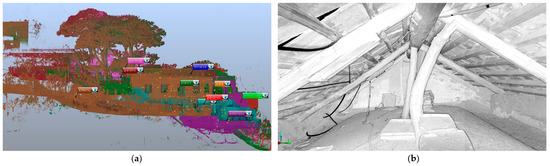

Figure 14.

Plan view of the point cloud from the laser scanner survey. Station points are clearly visible.

6.3. Integrated Survey

The Ground Control Points (GCPs)—checkerboard targets and Ringed Automated Detect (RAD) targets—were visible from the aircraft and identifiable in the point cloud obtained using the laser scanner, thus enabling the generation of a single model from the two point clouds. The network of control points provided topographical support for the process of georeferencing the two models (photogrammetric and laser), thereby compensating for the gaps in both clouds. For georeferencing purposes, the same coordinates were assigned to the analogous targets visible in the two clouds.

The data obtained using laser scanning enabled the acquisition of metric values, the generation of orthophotos, and spherical photos of both internal and external spaces. The choice of an active sensor technology such as laser scanning made it possible to acquire data even in low-light environments such as the villa’s attic, acquiring its reflectance values (Figure 15).

Figure 15.

(a) Registration phase in FaroSCENE software. (b) Reflectance map of the scan in the attic.

Accurate plans and sections were thus obtained in order to derive the thicknesses of the structural elements as well as their deformations. The data obtained using aerial photogrammetry enabled the survey of overhanging parts and roofs, which could not be detected from the ground. Moreover, terrestrial photogrammetry was used to obtain higher-resolution orthophotos of the painted interior surfaces.

Finally, a desktop application based on laser scanning data enabled the visualization and interrogation of the villa’s internal spaces. This enabled remote measurement and exploration, as well as an initial examination of the building’s three-dimensional configuration.

7. From Knowledge to Conservation

7.1. Surface Conservation and Structural Diagnosis and Strengthening

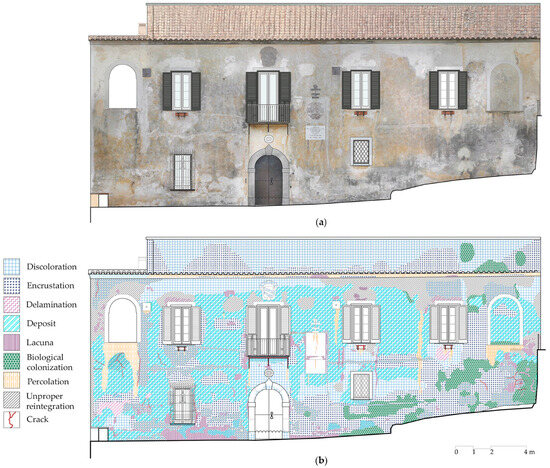

Overall, Villa Murat is in a satisfactory state of conservation. Indeed, its continuity of use has ensured almost uninterrupted maintenance. Notwithstanding, some structural criticalities have been identified, as well as issues related to the decay of the external and internal surfaces.

In the case of external rendered architectural surfaces, the objective is to preserve their material authenticity. It is therefore proposed that the surfaces should not be repainted but rather treated with light lime glazes that do not alter the fascination that the villa conveys due to the ancient aspect of its surfaces. These were analyzed in accordance with the terminology established in the ICOMOS Glossary [30], with the objective of identifying the forms of alteration and degradation. The external render was affected by different kinds of surface degradation: discoloration, deposit, percolation, as well as biological colonization and losses of material in the lower part. The main causes were exposure to weathering (the villa occupies a soaring position on the hill and is therefore more prone to the action of wind and marine aerosol) and the presence of rising dampness, which accentuates degradation close to the ground. The planned interventions include selective and gradable cleaning, mainly dry or with sprayed water, and small reintegration made using lime-based renders and paints (Figure 16). Particular attention is paid to the decorations made with tempera paint on the intrados of the vaults on the first floor, which are still almost intact with the exception of the structural cracks and the consequent detachment of some fragments of painted plaster.

Figure 16.

(a) Front elevation with orthophoto; (b) analysis of surface decay phenomena.

The structural criticalities mainly concern two issues: the extrados vaults on the upper floor and a portion of the wooden roofing. It should be pointed out that, following the strong earthquake that struck the entire region in 1980, several strengthening interventions were implemented, including the insertion of tie rods to counter possible movements, mainly of the front with the loggias, which was more vulnerable.

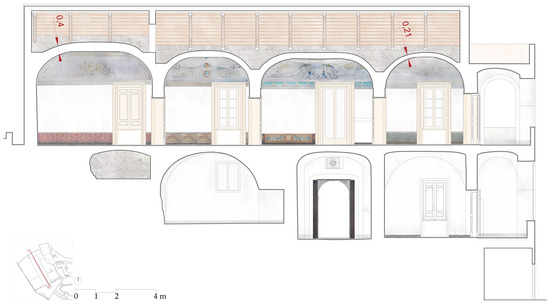

The laser scanner survey facilitated an accurate examination of the crack pattern and precise measurement of the thicknesses of the extradosed vaults. This revealed that the vaults are of varying thicknesses, from around 20 to 40 cm (Figure 17). The vault closest to the loggias is notably thinner and exhibits the most pronounced cracks. The vault closest to the garden, on the other hand, is markedly thicker and almost free of cracks. The second floor was located in correspondence with the vault with a greater thickness. Likely, this vault was built to be more stable, precisely because it was at an intermediate level. The greater thickness, as well as the more stable position in comparison to the front facing the sea, which was more prone to subsidence, meant that no cracks were formed.

Figure 17.

Longitudinal section. The differences in the thickness of the vaults are evidenced. The part of the roof on the left of the section is that with trusting structures instead of trusses.

In addition to some damage over the doors caused by the inflection of wooden lintels, the cracks are consistent with well-known collapse mechanisms of vaulted structures and of cloister vaults in particular [31,32] (pp. 231–237) [33] (pp. 90–97). One of the most prevalent failure mechanisms observed in cloister vaults is the detachment of the four webs that constitute the vault, with the formation of cracks along the diagonals of the vault due to tensile stresses. In Villa Murat’s vaults, this type of crack pattern can be observed and is more pronounced, with passing cracks of major widths in the two vaults in proximity to the loggias, and especially in the nearest one. These are thinner than the others and more susceptible to potential shifts of the springs and bearing walls due to movements of the northern front with the loggias. Indeed, the presence of a long crack parallel to the lateral wall next to the loggia is indicative of a small failure of the loggia structure. These cracks had been previously repaired and had reopened, showing an ongoing mechanism (Figure 18).

Figure 18.

Crack pattern survey of the painted vaults of the first floor.

In addition to verifying the efficacy of the existing ties rods in counteracting movements of the north elevation, the proposed solution entails consolidating the vaults with bands of fiber-reinforced composite material, aiming to select the most compatible matrix in accordance with the theoretical principles of conservation [34] and the need to preserve the historical finish in beaten lapillus. These bands should be placed at the extrados, along the diagonals and as annular strips, so that they can act as a hooping against the detachment of the webs [35,36].

Another intervention concerns the wooden roof. The part of the roof in close proximity to the garden, specifically in the area where the second floor was previously located, is not made of proper trusses. The chord is absent, and the weight is conveyed to the lateral walls and to the vault below through a strongly inflected strut (Figure 15b). Therefore, it is a trusting configuration that transmits an additional load to the vault. The proposal is to modify the structural behavior through the use of steel tie rods that simulate a mixed Polonceau-type truss consisting of a tripartite tie raised from the extrados of the underlying vault. Indeed, in this case, the extrados is so high that the use of a classic horizontal tie-rod is not feasible.

7.2. Reuse Proposal

After an in-depth analysis of the spatial characteristics of the building and the specific features of the context, a new intended use is proposed [37]: the “Artists’ residency”. This use, not far from the original residential one, enables the preservation of the spatiality of the building and takes advantage of the landscape context, which can be a source of inspiration for the artists. This choice is also based on the desire to allow for public use of the villa—for events or exhibitions—and to prevent it from becoming an enclave for luxury tourism, like many historic houses in the area. The new intended use is also linked to a well-established tradition of the Sorrento peninsula, where many artists have stayed since the mid-1700 s in search of inspiration.

The design of the interior spaces is based on minimal intervention and flexibility, allowing the artists to organize their studios according to their preferences. The revised layout (Figure 19) allows for the simultaneous accommodation of three artists, with dedicated workspaces allocated to each. The ground floor houses service areas and a shared atelier, situated within the largest room, which is free from any decoration that could be damaged by the artists’ activities. The lower level also comprises a first room, divided into a sleeping area and workspace in the brightest part. The artists’ rooms are diversified based on the art practiced and organized through flexible furnishings and low-height service blocks to avoid obstructing the view of the painted vaults. These blocks are dry-built and therefore reversible. Two more bedrooms are on the first floor. In addition to the private rooms, the new layout for the villa includes common areas for events and moments of interaction among the guests, such as the two rooms on the main front. Moreover, the row of rooms at the back is configured to accommodate small exhibitions of the works realized in the residence. The outdoor spaces, loggias, terraces, and garden are an essential part of the new layout. The aim is to bring new life to Villa Murat and also to introduce a compatible form of tourism in the Sorrento peninsula.

Figure 19.

Villa Murat converted into Artists’ residency. (a) Ground floor plan; (b) first floor plan.

8. Conclusions

An interdisciplinary approach to knowledge is always a necessary condition for the development of a compatible conservation and reuse project. Historical investigation, analysis of constructive features, and metric and material surveys all contribute to a thorough understanding of the building, of its evolution over time, and of the current conservation issues.

In the case of Villa Murat, the hypotheses derived from the study of documentary sources have been corroborated by direct observation of the artifact. The new information acquired through the integrated survey has expanded the scope of historical research. The metric and material data obtained from point clouds have facilitated the diagnosis of stability issues and the identification of their underlying causes.

In particular, the information contained in some ancient land registers, compared with historical views and photographs, made it possible to reconstruct the process of evolution of the architectural complex, from its initial rural vocation to its later purpose as a “villa of delights.” The main features of the vernacular architecture of the Sorrento Peninsula were explored. Recurrent constructive and morphological aspects were then found in Villa Murat, confirming the building’s origins.

This study was conducted with two principal objectives in mind. The first was to examine the historical transformation and expansion of Villa Murat. This was intended as a case study that exemplifies an underexplored process of gradual change and evolution commonly observed in architectural heritage with a rural character at the beginning in the Sorrento–Amalfi region.

The second objective pertains to the diagnosis of the building, with the aim of ensuring its preservation through restoration interventions and the formulation of a reuse proposal. In an area of extremely strong tourist vocation such as the Sorrento Peninsula, the effects on the architectural heritage of exploitation for tourism purposes are obvious. On the one hand, the continuity of use serves as a guarantee of ongoing maintenance. Conversely, the introduction of activities that are not always compatible can result in the loss of some of the historical, constructive, and testimonial values of the assets, with the economic value becoming the primary consideration. In particular, the elements that have been the subject of this study are often the most vulnerable: surfaces, traces of previous uses, however modest, and evidence of past construction techniques, especially in less-visible parts of the building. In this regard, the appeal addressed to “conservators” by Piero Gazzola, now 60 years ago, at the opening of the Congress that led to the drafting of the Venice Charter, is of particular significance. It is not the responsibility of experts in the field of preservation to be intransigent, but rather to identify methods for the “most convenient” (or compatible) utilization, including those for tourism purposes, so that “the new economic stimuli are regarded as an aid rather than as an obstacle” [38].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.P. and M.P.; methodology. A.P. and M.P.; writing—original draft preparation, M.P.; writing—review and editing, A.P. and R.C.; project administration, A.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the owners of Villa Murat for their helpfulness throughout the research project and Arch. Marco Facchini, who was responsible for and managed RPAS.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Pane, R. Architettura Rurale Campana; Rinascimento del Libro: Firenze, Italy, 1936. [Google Scholar]

- Pane, R. Capri; Neri Pozza: Venezia, Italy, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Picone, R. A Sustainable Architecture. Rustic Dwellings in the Area between Capri and the Amalfi-Sorrentine Coast. In Landscape as Architecture. Identity and Conservation of Crapolla Cultural Site; Russo, V., Ed.; Nardini Editore: Firenze, Italy, 2014; pp. 265–273. [Google Scholar]

- Fiengo, G.; Abbate, G. Case a Volta della Costa di Amalfi: Censimento del Patrimonio Edilizio Storico di Lone, Pastena, Pogerola, Vettica Minore e Tovere; Centro di Cultura e Storia Amalfitana: Amalfi, Italy, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Archivio Di Stato Di Napoli. Catasto Provvisorio di Napoli e provincia, II Versamento, Stato Sezioni 1060. Available online: http://patrimonio.archiviodistatonapoli.it/asna-web/catalogo/scheda/progettare-futuro/IT-ASNA-CATALOGO-0002446/0482-Catasto-provvisorio-di-Napoli-e-provincia-Inventario.html (accessed on 10 September 2024).

- Pagano, G.; Daniel, G. Architettura Rurale Italiana; Quaderni della Triennale; Ulrico Hoepli Editore: Milano, Italy, 1936. [Google Scholar]

- Pane, R. Tipi Di Architettura Rustica in Napoli e Nei Campi Flegrei. Archit. Arti Decor. 1928, 12, 529–543. [Google Scholar]

- Picone, R. Capri, mura e volte. Il valore corale degli ambienti antichi nella riflessione di Roberto Pane. In Roberto Pane tra Storia e Restauro. Architettura, Città, Paesaggio; Casiello, S., Pane, A., Russo, V., Eds.; Marsilio: Venezia, Italy, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Pane, R. Sorrento e La Costa; Edizioni Scientifiche Italiane: Napoli, Italy, 1955. [Google Scholar]

- Cerio, E. L’architettura minima nella contrada delle Sirene. Archit. Arti Decor. 1922, 4, 156–176. [Google Scholar]

- Pane, R. Documentazione Ambientale della Costiera Amalfitana. Napoli Nobilissima 1977, 16, 3–41. [Google Scholar]

- Branduini, P.; Pane, A. City and Countryside: A Historical Landscape System to Enhance. The Case of the Territorial Plan of Sorrento-Amalfi Peninsula by Roberto Pane and Luigi Piccinato, 1968–1987. In Re-Imagining Resilient Productive Land-Scapes. Perspectives from Planning History; Brisotto, C., Lemes de Oliveira, F., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 155–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regione Campania. Piano Territoriale Di Coordinamento e Piano Paesistico Dell’area Sorrentino—Amalfitana; Proposta: Napoli, Italy, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Zevi, B. Controstoria Dell’architettura in Italia: Dialetti Architettonici; Tascabili Economici Newton: Roma, Italy, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Persico, G. Descrittione della Città di Massa Lubrense; Stamperia Francesco Savio: Napoli, Italy, 1946. [Google Scholar]

- Filangieri di Candida, R. Storia di Massa Lubrense; Arte Tipografica: Napoli, Italy, 1910. [Google Scholar]

- Archivio Diocesano Sorrentino Stabiese. Santa Visita Del Vescovo Nepita. ff, 25, 27 v, 42 v.

- Archivio Di Stato Di Napoli. Catasti Onciari. Volume 171. Available online: http://patrimonio.archiviodistatonapoli.it/asna-web/catalogo/scheda/progettare-futuro/IT-ASNA-CATALOGO-0002367/0451-Catasti-onciari.html (accessed on 10 September 2024).

- Della Morte, G. Ogni Resistenza è Vana; Edizioni la Conchiglia: Capri, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Fasulo, M. La Penisola Sorrentina: Meta, Piano, Sant’Agnello, Sorrento, Massalubrense. Istoria. Usi e Costumi. Antichita e Ricerche; Stab. Tip. Gennaro Priore: Napoli, Italy, 1906. [Google Scholar]

- Patrucco, G.; Perri, S.; Spanò, A. TLS and Image-Based Acquisition Geometry for Evaluating Surface Characterization. In Proceedings of the ARQUEOLÓGICA 2.0—9th International Congress & 3rd GEORES—GEOmatics and pREServation, Valencia, Spain, 26 April 2021. Editorial Universitat Politécnica de Valéncia. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, N.; Mikolajewska, S.; Roncella, R.; Zerbi, A. Integrated Processing of Photogrammetric and Laser Scanning Data for Frescoes Restoration. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2022, 46, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, N.; Coïsson, E.; Cotti, M. Laser-Scanner Survey of Structural Disorders: An Instrument to Inspect the History of Parma Cathedral’s Central Nave. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2017, 42, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spanò, A.; Patrucco, G.; Sammartano, G. Reality-Based 3D Survey and Modeling Supporting Historical Vaulted Structures Studies. In Shell and Spatial Structures; Gabriele, S., Manuello Bertetto, A., Marmo, F., Micheletti, A., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Civil Engineering; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 437, pp. 857–866. ISBN 978-3-031-44327-5. [Google Scholar]

- Ottoni, F.; Freddi, F.; Zerbi, A. From “Models” to “Reality”, and Return. Some Reflections on the Interaction between Surveyand Interpretative Methods for Built Heritage Conservation. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2017, 42, 457–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caroti, G.; Piemonte, A. Integration of Laser Scanning and Photogrammetry in Architecture Survey. Open Issue in Geomatics and Attention to Details. In R3 in Geomatics: Research, Results and Review; Parente, C., Troisi, S., Vettore, A., Eds.; Communications in Computer and Information Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 1246, pp. 170–185. ISBN 978-3-030-62799-7. [Google Scholar]

- Bastonero, P.; Donadio, E.; Chiabrando, F.; Spanò, A. Fusion of 3D Models Derived from TLS and Image-Based Techniques for CH Enhanced Documentation. ISPRS Ann. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2014, 2, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabris, M.; Fontana Granotto, P.; Monego, M. Expeditious Low-Cost SfM Photogrammetry and a TLS Survey for the Structural Analysis of Illasi Castle (Italy). Drones 2023, 7, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo Brutto, M.; Iuculano, E.; Lo Giudice, P. Integrating Topographic, Photogrammetric and Laser Scanning Techniques for a Scan-to-BIM Process. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2021, 43, 883–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICOMOS-ISCS. Illustrated Glossary on Stone Deterioration Patterns; Monuments and Sites; English-French Version; ICOMOS: Paris, France, 2008; ISBN 978-2-918086-00-0. [Google Scholar]

- Cangi, G. Manuale Del Consolidamento e Restauro: Archi e Volte; Dei.Tipografia del Genio Civile: Roma, Italy, 2023; ISBN 979-1255050032. [Google Scholar]

- Giuffrè, A. La Meccanica Nell’architettura: La Statica; 4. rist.; Carocci: Roma, Italy, 2003; ISBN 978-88-430-2524-4. [Google Scholar]

- Di Stefano, R. Il Consolidamento Strutturale nel Restauro Architettonico; Edizione Scientifiche Italiane: Napoli, Italy, 1990; ISBN 978-88-7104-209-1. [Google Scholar]

- Ottoni, F.; Coisson, E. New materials for structural restoration: An old debate. ArcHistoR 2015, 4, 92–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiozzi, A.; Milani, G.; Tralli, A. Fast Kinematic Limit Analysis of FRP-Reinforced Masonry Vaults. II: Numerical Simulations. J. Eng. Mech. 2017, 143, 04017072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foraboschi, P. Strengthening of Masonry Arches with Fiber-Reinforced Polymer Strips. J. Compos. Constr. 2004, 8, 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musso, S.F.; Kealy, L.; Fiorani, D. (Eds.) Conservation Adaptation: Keeping Alive the Spirit of the Place: Adaptive Reuse of Heritage with Symbolic Value; EAAE: Hasselt, Belgium, 2017; ISBN 978-2-930301-65-5. [Google Scholar]

- Gazzola, P. Foreward. In The Monument for the Man. Records of the II International Congress of Restoration, ICOMOS, Venezia, 25–31 Maggio 1964; Marsilio Editori: Padova, Italy, 1971. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).