1. Introduction

A significant issue facing most cultural heritage tourism worldwide is the lack of diversity among tourists, particularly those in the 18–25 age range. Numerous studies from diverse countries and cultures demonstrate that cultural and heritage sites globally are frequently overlooked and do not specifically target young people. This universal trend spans continents and societies. Young adults consistently believe that cultural and heritage stories are unrelated to their lifestyles and were not designed for them [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. Nonetheless, Boukas [

6] argues that by observing how young tourists behave, one can learn more about their interests and tailor their experiences accordingly.

This research therefore proposes applying classic Thai literature that the target group has studied, “Khun Chang Khun Phaen (KCKP)”, for high school students (grade 12) to facilitate cultural heritage tourism. Fast-paced heroics, adventure, romance, sex, violence, folk humor, magic, horror, and passages of lyrical beauty can all be found in this classic literature. A love story with a wartime backdrop and a tragic conclusion make up the plot, which may interest young tourists [

7,

8]. Notably, the story’s locations—which correspond to the ideas of literary tourism and folklore tourism—are actual heritage places in the province of Suphan Buri.

However, in parallel, the educational system is facing significant challenges in engaging students with classic literature. There are a number of issues with students studying literature: (1) students do not understand the archaic vocabulary, (2) they find the literature boring, (3) students lack the skills to read long and complex writing, (4) there is a lack of modern and interesting learning materials, and (5) the instructor focuses solely on reciting vocabulary [

9,

10].

The study is set up in Thailand for several key reasons. Firstly, this research focuses on a classic Thai literature, KCKP. This story offers a chance to investigate the potential of leveraging local cultural assets for heritage tourism and teaching Thai youth classic literature. Moreover, KCKP is a part of the grade 12 high school curriculum. This allows the research to directly propose the barriers and motivations within the Thai educational system. Finally, the locations in the KCKP story correspond to actual heritage sites in Suphan Buri Province. This could present a tangible link between classic literature and physical cultural heritage, making Thailand an ideal setting for exploring literary and folklore tourism.

This research tries to bridge these gaps by exploring the intersection of cultural heritage tourism and classic literature through design guidelines specifically tailored for youth. Therefore, this research aims to create and evaluate design guidelines applying classic literature to facilitate cultural heritage tourism and interest in learning classic literature and history, specifically for youth. To achieve this, the study addresses the following research questions:

(1) “What are the effective design guidelines for creating a multimedia e-book based on classic literature to facilitate cultural heritage tourism among youth?”

(2) “Does the design guidelines interest young tourists in cultural heritage tourism, history and classic literature?”

A multimedia e-book backed by empirical data from three phases—Phase 1: developing design guidelines from youth recommendations; Phase 2: creating a multimedia e-book; and Phase 3: evaluating this multimedia e-book—serves as the research’s success criterion. This research contributes to knowledge in several areas, cultural heritage tourism, education, and multimedia design, and proposes the design guidelines that other studies can apply to overcome barriers in studying classic literature and the lack of motivation to engage in cultural heritage tourism.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Keyword Analysis and Research Gap

The researcher implemented systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [

11]. Initially, the following inclusion criteria were determined: peer-reviewed studies in English, publications from any year, types of publications including research articles and review articles, and categories including art and humanities, social science, business, management, and accounting. Subsequently, the researcher conducted a search of two significant databases, Scopus and ScienceDirect.

The choice of Scopus and ScienceDirect as the primary databases for this study was based on several factors. Scopus and ScienceDirect are among the largest abstract and citation databases of peer-reviewed literature, especially cultural heritage and tourism. Next, these databases offer systematic search tools, allowing for precise keyword searches and the application of inclusion and exclusion criteria. Moreover, regarding Google Scholar, it was included as a supplementary database to support any relevant literature that might not be indexed in the primary databases.

Consequently, the search terms were implemented to retrieve keywords, abstracts, and titles. The abstracts and topics of the first 100 articles on Google Scholar were the sole criteria that the researcher used to select 50 articles pertinent to the keywords and themes of the review article. The objective was to gather all pertinent information from the past and up to the present, as illustrated in

Table 1, using the keywords “tales”, “literary”, “cultural”, “heritage”, and “tourism” in any year. Furthermore, three researchers conducted a comprehensive review of all 550 titles and abstracts (25 + 425 + 100) and excluded articles that were determined to be irrelevant to the subject matter. A total of 50 articles were deemed eligible, meeting the criteria, as illustrated in

Table 1.

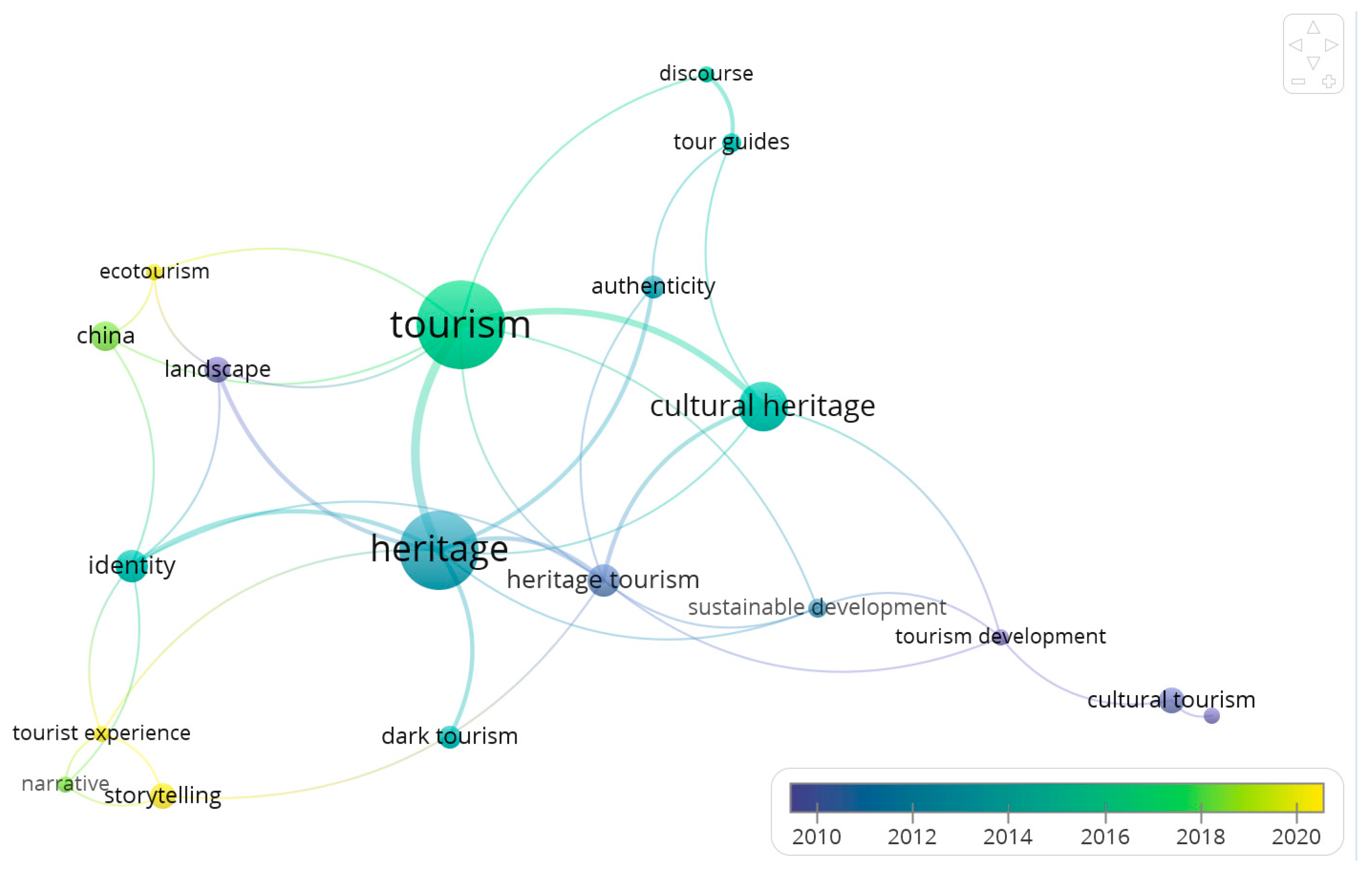

Using the VOSviewer software (version 1.6.20), the researcher imported the RIS files and configured keywords to detect a frequency of over five keyword occurrences. Initially, the VOSviewer software produced results that displayed five clusters of keywords, each of which was represented by a distinct color.

Figure 1 illustrates these clusters and their respective link strengths. This implies that the trends in the adoption of folktales and literature in cultural heritage tourism, as identified by these keywords in the three databases, are primarily focused on five themes: (1) cultural heritage, cultural tourism, heritage tourism (red); (2) ecotourism, landscape (green); (3) identity, narrative, storytelling (blue); (4) authenticity, tour guides, discourse (yellow); (5) dark tourism, heritage (purple). Nevertheless, the results of these searches did not reveal any keywords that were pertinent to the incorporation of folktales or literature into cultural heritage tourism. Subsequently, this is a research gap that neglects the use of literature and folktales to promote cultural heritage tourism.

Additionally, the VOSviewer software can be configured to display keyword co-occurrence determined by the years of publication. The most recent years of publication (2020+) are indicated by the yellow-colored keywords and include storytelling, tourist experience, and ecotourism, as shown in

Figure 2. This may suggest that these keywords currently make up the latest trends.

2.2. Heritage Tourism, Cultural Tourism, Cultural Heritage, and Creative Tourism

These four keywords are quite confusing and intersect. This research tries to identify their differences. First, heritage tourism, as defined by Park et al. [

12], is the propensity to visit historical sites and interact with a wide variety of artifacts that serve as icons of the past. Cultural tourism is the term used to describe the travel and exploration that are primarily motivated by cultural interests. This includes attendance at performing arts and cultural events, visits to historical sites and monuments, and participation in festivals [

13]. Cultural heritage tourism is the act of traveling to specific locations and events that accurately portray the histories and cultures of both the past and present [

14]. Creative tourism differentiates itself from cultural and heritage tourism by emphasizing local lifestyles and encouraging engagement, rather than exclusively emphasizing historical landmarks and architectural marvels.

2.3. The Importance of Youth in Cultural Heritage Tourism

Numerous tourism industries disregard this demographic, youth, due to their assumption that cultural heritage tourism is exclusively intended for older rather than younger generations [

15]. However, inclusion of young tourists can be enhanced by a more comprehensive understanding of their behaviors and desires [

6,

15]. The Scottish Executive [

16] also endorses the notion that young tourists are a critical target demographic for cultural heritage tourism, as they will serve as future adult cultural tourists. Consequently, in order to anticipate future trends in cultural tourism, it is imperative that the tourism industry and the government be aware of the profiles, lifestyles, trends, and behaviors of the youth demographic [

3,

16].

2.4. The Factors of the Cultural Heritage Tourism E-Book for Young People

Kasemsarn [

2] proposes four design factors that are essential for the development of a cultural heritage tourism e-book aimed at young people. These factors include travel photography, storytelling, characters, and layout design. In the context of photography, prior research has demonstrated that photographs have the potential to motivate and influence tourists to visit specific locations. This is due to the fact that tourism is directly associated with visual media, specifically photographs, which have the ability to captivate individuals through their visual appeal [

17]. Groves and Timothy [

18] conduct research on the factors in photographs that pique tourists’ interests. The majority of respondents reported that photos of people in landscapes were the most inspiring, followed by photos of symbols and signs, heritage, cultural, and architectural sites, and landscapes. Storytelling in films has the potential to transport viewers. The data suggest that “scenery” is the most significant factor in film (43%), followed by “narrative/story” (20%), and “characters” (10%). This point has the potential to serve as a substantial motivational factor in the development of digital storytelling for cultural tourism [

2,

19].

Another factor is the introduction of characters during the design process of books, films, games, animations, or video games. In order to encourage audience members to engage with narratives, characters should be representative of them [

20]. Kasemsarn and Nickpour [

21] employ five groups to investigate digital storytelling characters in cultural tourism. The results suggest that designers should create characters with the same age and conditions as the target audience. In this instance, young individuals favor characters who are popular, stylish, and youthful. Studies have demonstrated that the composition of text, columns, photographs, and space in a book layout design is a critical factor in the development of visually appealing presentations that align with the preferences and performance of readers [

22]. Consequently, it is imperative that researchers should put the target audience in the center and present a layout style that is effective in terms of both performance and preference [

23].

2.5. Classic Thai Literature “The KCKP: Khun Chang Dedicates the Petition”

The KCKP epic has been orally transmitted by Thai troubadours for a long time. The poem was initially composed and published in print in 1872, with a standard edition being published in 1917–1918. Like numerous works that have their roots in popular entertainment. This story is characterized by its rapid pace and multitude of elements, including heroism, romance, sex, violence, folk comedy, horror, magic, and passages of lyrical beauty. It is a love story that is set against a backdrop of war and culminates in a high tragedy [

7,

8].

Episode “Khun Chang dedicated the petition” of KCKP is used to instruct high school students (grade 12). The synopsis from Baker and Phongpaichit [

7] is as follows:

Plai Ngam desires that his mother, Mrs. Wanthong, relocate to his residence. Consequently, he abducts her from the residence of Khun Chang. Upon learning of the situation, Khun Chang is incensed and resolves to draft a supreme lawsuit to His Majesty the King in order to assist in the resolution of the matter. Thus, His Majesty the King summons Mrs. Wanthong to determine with whom she will reside. Nevertheless, Mrs. Wanthong refrains from making a decision in order to preserve the benevolence of all parties. His Majesty becomes enraged because he recognizes Mrs. Wanthong as a person of duplicity. Consequently, he demands that Mrs. Wanthong be transported to the execution site.

The narrative is set in the famously literary region of Suphan Buri. The KCKP literature is used by Suphan Buri province to encourage cultural tourism in Mueang District: (1) Wat Khae (Khun Phaen’s residence and the giant tamarind tree) and (2) Wat Pa Lelai (Khun Chang’s residence, Luang Pho To, and mural paintings). The age of Wat Pa Lelai is thought to be 1200 years old. All of these locations were shot by the researcher and their team and divided into three episodes. “Revive Thai Literature” is the YouTube channel where these contents are posted.

2.6. Theories About Applying Literature to Cultural Heritage Tourism

2.6.1. Folklore Tourism

Everett and John [

24] explain that folklore festivals are becoming an increasingly popular form of heritage tourism. Organizations such as the European Association of Folklore Festivals are dedicated to the preservation, development, and promotion of the folklore of various European nations, while companies provide tourists with the opportunity to participate in art and dance. Crompton and McKay [

25] conceptualize the “escape-seeking dichotomy”, in which escape from a daily routine is one of the primary motivators of tourists. Larsen [

26] suggests that tourism does not always generate distinct ontological worlds from the “everyday”, despite the profound concept of emotional and physical detachment from daily life. Several studies support that folklorism is significantly influenced by everyday life, as it aims to integrate more mythical perspectives into the contemporary world, enabling individuals to integrate their daily lives and imaginations into a more comprehensive and integrated whole [

24,

26,

27,

28]. In summary, folklore and historical reenactments are purported to facilitate the transformation of memory, history, and personal narrative into a visible leisure performance. This transformation occurs when individuals utilize nostalgic symbolism to recollect and connect their past and present lives [

29].

2.6.2. Heritage Tourism through Folklore Tourism

Lyngdoh [

30] illustrates that folklore and its diverse manifestations, including myths, legends, and folktales, are approached in a variety of ways, such as heritage tourism [

31]. Objects that can be held, buildings that can be explored, songs that can be sung, and stories that can be told are among the many forms of folklore. These items are a component of a heritage necessary in order to preserve it [

30,

32,

33]. According to Lyngdoh [

30], the integration of folklore and cultural heritage has at least three distinct and interconnected implications. The initial interpretation examines cultural heritage from the perspective of material objects, including monuments, buildings, and collections of objects. The second one examines cultural heritage from an artistic perspective, including performing arts, social practices, rituals, festive events, songs, knowledge and practices regarding nature and the universe, and the knowledge and skills necessary to produce traditional crafts. The third meaning examines cultural heritage from the perspective of inheritance, including oral traditions, stories (myths, legends, and folktales), and traditions or living expressions that are inherited from our ancestors and passed down to our descendants.

2.6.3. Fantasy and Fairytale Tourism

Lovell [

34] suggests that fantasy and fairytales can be utilized to enhance authenticity, tourism, and heritage. Tourists who pursue “experiential authenticity” are motivated by the desire to fulfill an unattainable or fantasy [

34,

35]. Furthermore, folktale tourism is considered a subset of heritage tourism, providing tourists with an experience that is “beyond the ordinary” [

36]. The desire to escape the everyday and immerse oneself in fantasy can be considered the foundation of much tourism activity. Additionally, authenticity is a critical component that is applicable in themed magical environments. Waysdorf and Reijnders [

37] and Lovell and Bull [

38] observe how tourists authenticate the Wizarding World of Harry Potter, for instance, by utilizing the theme park’s official endorsement by J.K. Rowling. Kim and Jamal [

39] suggest that tourists create an “alternative reality” during these activities. The art of storytelling has consistently been regarded as a critical component of historical interpretation, and fairytales offer recognizable frameworks that facilitate tourists’ connection to the past. Fairytales are a significant aspect of tourism, as some tourists are interested in comprehending the myths surrounding the origins of certain locations [

38].

2.6.4. Literary Tourism

Literary tourism is situated at the intersection of cultural tourism and heritage tourism [

40]. Literary tourism has been categorized by some researchers under heritage tourism [

41,

42] and cultural tourism [

43,

44]. Butler’s classification [

45] comprises four categories of literary tourism (Busby and Klug, 2001) as well as four additional categories [

46,

47]:

(1) Aspects of homage to a real location: The actual locations associated with the author. These sites are typically the author’s birthplace, residence, or place of death.

(2) Sites of literary significance: Tourists may be attracted to locations that serve as the backdrops for novels. Fiction may be set in locations that authors are familiar with, and the real and the fictional may be intertwined.

(3) Attraction to regions due to their appeal to literary and other figures: This category encompasses destinations that cater to literary figures. It encompasses the marketing and development initiatives of destinations in the public and private sectors in relation to literary tourism.

(4) The literature becomes popular to the extent that the region becomes a tourist destination in its own right. This category suggests that a region is transformed into a tourist destination without any effort due to the popularity of an author or literary work.

(5) Busby and Klug [

46] identify “travel writing” as the fifth form of literary tourism, defining it as “a medium through which individuals and locations have been reinterpreted and communicated to a broader audience” (p. 321).

(6) According to Busby and Laviolette [

48], the sixth form of literary tourism is “film-induced literary tourism” (p. 149). The authors define film-induced literary tourism as “tourism that is the result of heightened interest in a destination, which is achieved by reading the literature following the viewing of the screenplay.”

(7) and (8) “Literary festivals” and “bookshop tourism” are proposed as the seventh and eighth types of literary tourism, respectively. In the United Kingdom, literary festivals include a plethora of annual events that provide participants with the opportunity to engage with authors and other celebrities, as well as for authors to promote their literary works. The eighth type of literary tourism, bookshop tourism, involves tourists visiting local bookshops to purchase destination-related materials, such as guidebooks, maps, or books written by local authors [

40,

47].

2.6.5. Local Tales as a Form of Cultural Heritage Tourism

Wannakit [

49] proposes that local tales are considered a form of intangible cultural resource. In Thailand, from 2010 to 2012, the Ministry of Culture expanded to include additional cultural heritage in the form of social customs, rituals, and festivals in local tales. The board classified these elements into seven categories: local stories, local myths, hymns or ritual prayers, local songs, idioms, riddles, and books [

50]. Local tales, which are considered heritage cultural wisdom, are present in numerous adaptations. Currently, they are used as a side story to accompany local products in order to enhance tourism management, which is the primary focus of this article. Using heroes from local myths to promote their provinces as part of the cultural heritage of wisdom is another intriguing example [

49,

50].

All theories about applying literature to cultural heritage tourism are summarized in

Table 2.

3. Materials and Methods

The research employed three phases and two distinct research methods (quantitative and practice-based), as outlined below:

Phase 1 (prescriptive study): Design guidelines were created for the multimedia design of KCKP for youth. The quantitative research involved 600 on-site questionnaires distributed to Thai youth aged 18–25 across six provinces, representing different regions of Thailand. The sample size was determined using Yamane’s formula with a 96% confidence level and 4% margin of error. The questionnaire consisted of three sections: demographic information, 37 Likert-scale questions about multimedia design preferences, and an open-ended question for additional opinions. The mean, standard deviation (S.D.), and one-way ANOVA were the data analysis methods. The survey was conducted in schools, universities, and department stores during after-school hours in June 2023, with each questionnaire taking 10–15 min to complete.

Phase 2 (prescriptive study): A multimedia KCKP e-book was created to facilitate cultural heritage tourism for youth. A 50-page e-book containing short video clips about cultural heritage tourism in the Suphan Buri province, featuring the actual locations in the KCKP story, was made available in both Thai and English.

Phase 3 (descriptive study 2): The evaluation of the multimedia KCKP e-book in Phase 3 involved 100 Thai youth aged 18–25 in Bangkok, selected using Yamane’s formula with a 90% confidence level. Participants, who were high school and university students at the KMITL Expo 2024, Bangkok (March 2024), interacted with the e-book via an interactive kiosk before completing a three-part questionnaire: demographics, Kirkpatrick Evaluation Model questions (5-point Likert scale), and open-ended recommendations. Data analysis employed t-tests, means, and standard deviations to assess the e-book’s effectiveness in engaging youth with classic literature and cultural heritage tourism.

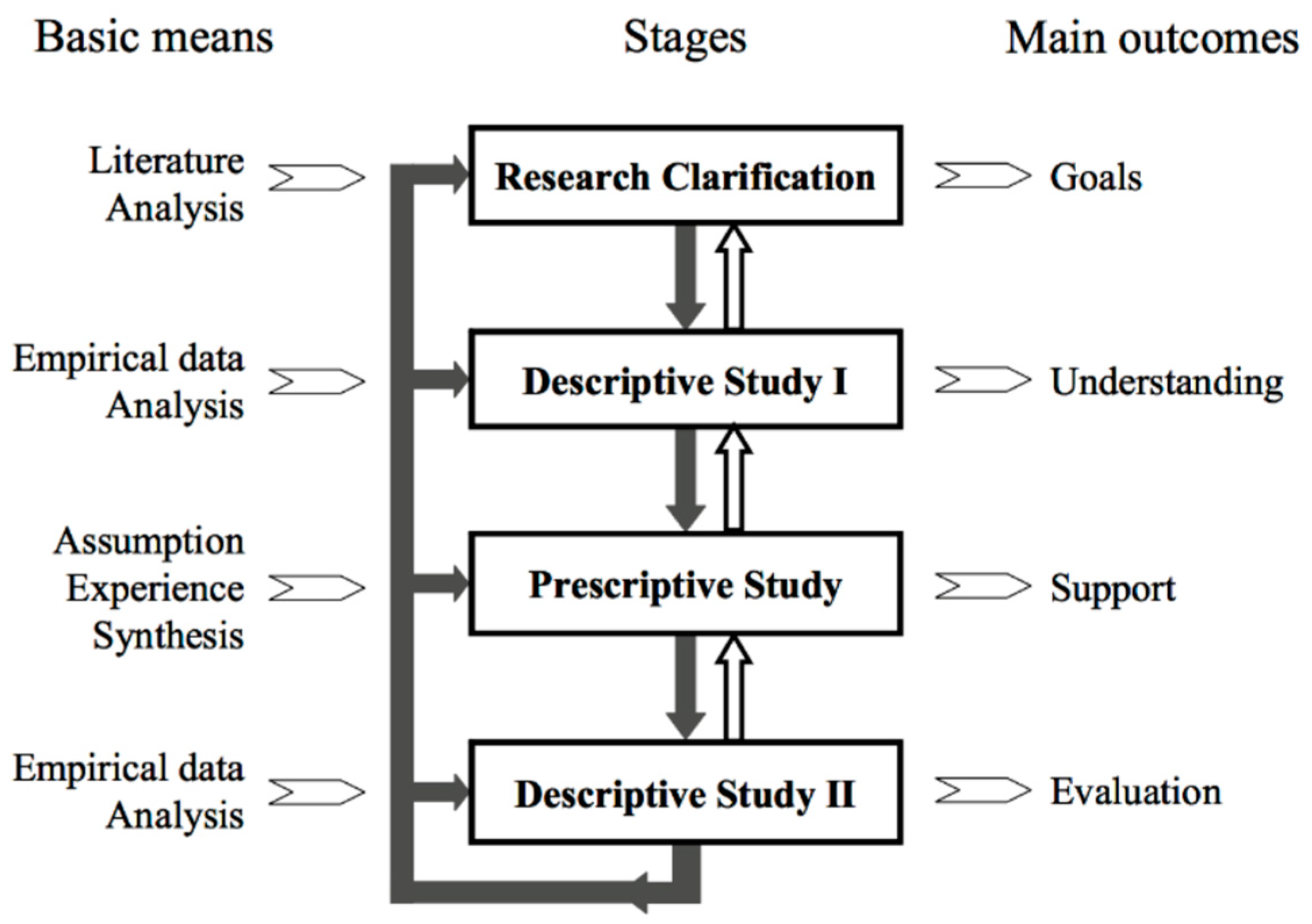

Additionally, the four stages of design research methodology (DRM) were employed in this study [

53], as presented in

Figure 3. This methodology is appropriate for research that is derived from a variety of studies and methods, as it features numerous stages and includes an evaluation stage to evaluate the impact of prescriptive and practical work.

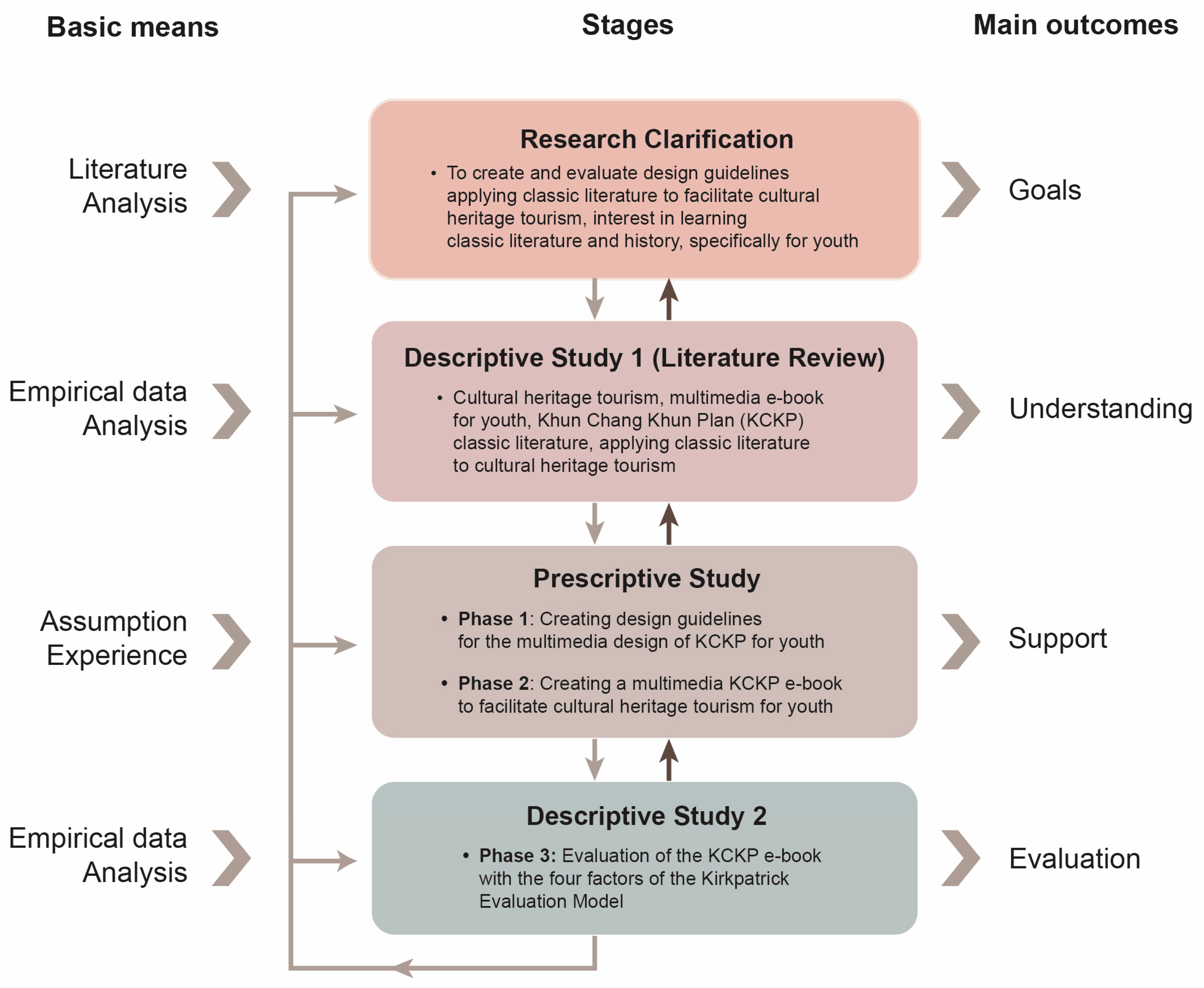

The researcher adopted DRM, as presented in

Figure 4, by starting the first stage as “research clarification” with the aim to create and evaluate design guidelines applying classic literature to facilitate cultural heritage tourism and interest in learning classic literature and history, specifically for youth. In the next stage, Descriptive Study 1, four factors were reviewed: cultural heritage tourism, designing a multimedia e-book for youth, KCKP classic literature, and theories about applying classic literature to cultural heritage tourism. The third stage, Prescriptive Study 1, was supported by Phase 1 (creating design guidelines for the multimedia design of KCKP for youth) and Phase 2 (creating a multimedia KCKP e-book to facilitate cultural heritage tourism for youth). Finally, Descriptive Study 2 involved Phase 3 (evaluation of the KCKP e-book with the four factors of the Kirkpatrick Evaluation Model).

4. Results

4.1. Phase 1: Creating Design Guidelines for the Multimedia Design of KCKP for Youth (600 On-Site Questionnaires in Six Provinces)

In Phase 1, the objective of this quantitative research was to establish design guidelines for the multimedia design of KCKP to make it appropriate for youth. KCKP episode “Khun Chang dedicated the petition” is used to instruct high school students (grade 12), the target group. The sample group was composed of Thai youth aged 18–25 living in six provinces from six regions in Thailand. The provinces were selected based on the highest population of young people in each region (Bangkok, Nakhon Ratchasima, Chiang Mai, Chonburi, Ratchaburi, and Nakhon Si Thammarat). Six hundred questionnaires were distributed at schools, universities, and department stores in each province from Monday to Friday from 16:00 to 18:00, i.e., after school and work. According to the National Statistical Office, Ministry of Information and Communication Technology [

54], the total number of Thai youth (18–25 years old) residing in Thailand is approximately 7,622,345. Thus, the sample size was determined to have a confidence coefficient of 96% and an error margin of 4% by employing Yamane’s formula [

55]. The sample size was determined to be 600 individuals.

In May 2023, a pilot test was conducted with 60 young participants, representing 10% of the total sample size, to assess the flow and comprehension of the questions and their length. To initiate the validity test, the researcher distributed questionnaires to three experts for evaluation by the item–objective congruence index (IOC index) [

56]. The IOC results surpassed the 0.5 threshold for each question. The researcher then conducted tests to determine reliability, which resulted in a Cronbach’s alpha value of 0.882, indicating an 88.2% level of reliability for all questions.

In June 2023, 600 on-site questionnaires were distributed by the researcher and their team after school and work, as presented in

Figure 5. The questionnaire is divided into three sections. Four questions regarding demographic profiles are included in Section 1, which employs a nominal scale. Section 2 comprises four subsections that contain 37 questions that utilize Likert scales to establish guidelines for making the multimedia design of the KCKP e-book appropriate for youth. One open-ended question regarding the respondents’ opinions comprises Section 3. The completion time ranged from 10 to 15 min.

The demographic data, presented in

Table 3, indicate that the participants from the six provinces were males (30.33%), females (57.17%), LGBTQ (10.33%), and unspecified (2.17%). The majority of the participants were aged 18–20 years old (58.17%), were studying for an undergraduate degree (94.17%), and went on approximately 1–3 cultural tourism trips a year (83 respondents).

In Section 2, presented in

Table 4, regarding reliability, the researcher performed tests using Cronbach’s alpha, which was found to be 0.907, meaning the results are 90.7% reliable. Next, the information from 600 respondents was collected using a Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree” (1) to “strongly agree” (5), with mean scores and interpretations indicated below:

This research divided the results from the participants into six groups based on the provinces with the highest number of young residents in each region (Bangkok, Nakhon Ratchasima, Chiang Mai, Chonburi, Ratchaburi, and Nakhon Si Thammarat) to determine whether there was a distinction in the results among the six provinces by employing one-way ANOVA, which is illustrated in

Table 5.

A one-way ANOVA with a post hoc Tukey test was used to compare scores across all four main questions among six provinces. The comparison of scores for Section 1 questions (barriers to studying classic Thai literature) revealed that participants scored significantly (

p < 0.05) higher in Chonburi and significantly lower in Chiang Mai. Similarly, the comparison of scores for the Section 3 questions (adapting classic literature to modern times) among six provinces showed that participants scored significantly (

p < 0.05) higher in Nakhon Si Thammarat and significantly lower in Nakhon Ratchasima, Chiang Mai, and Chonburi. However, the results showed no significant differences (

p > 0.05) among provinces for the Section 2 questions (motivations for studying classic Thai literature) and Section 4 questions (how to adapt classic literature into multimedia). All four sections in Phase 1 were summarized and presented with design guidelines for the multimedia KCKP design for youth in

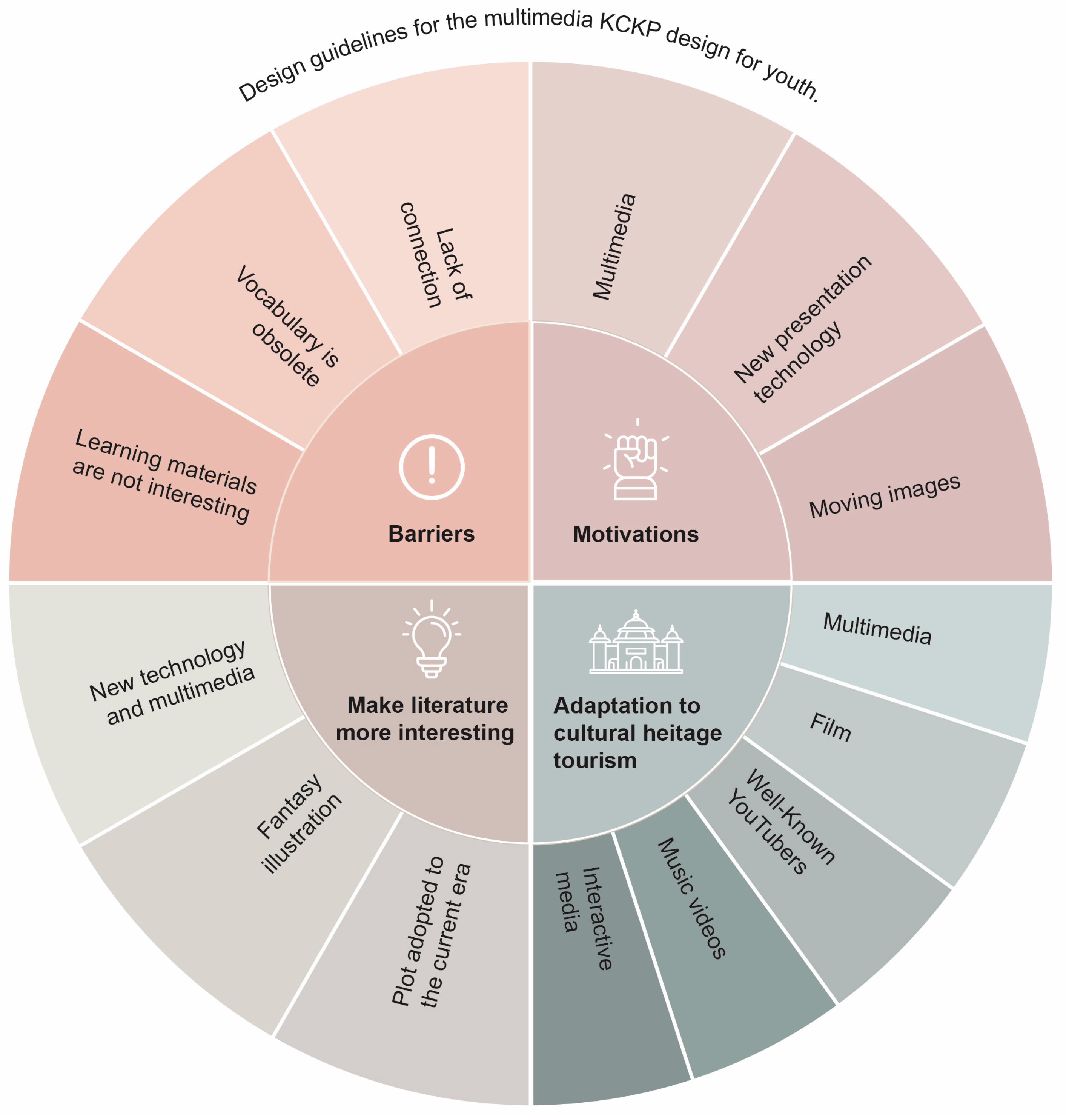

Figure 6.

Regarding Phase 1’s results, effective design guidelines should address four key factors, as shown in

Figure 6: (1) Barriers to studying classic Thai literature (lack of connection, vocabulary is obsolete, learning materials are not interesting). (2) Motivations (multimedia, new presentation technology, and moving images). (3) Make literature more interesting (new technology and multimedia, fantasy illustration and plot adapted to the current era). (4) Adaptation to cultural heritage tourism (multimedia, film, well-known YouTubers, music videos, and interactive media). The approach should focus on creating engaging, visually appealing content that resonates with youth, establishes relevance to their lives, and seamlessly integrates with their digital habits. By following these guidelines, the multimedia e-book or other media can effectively bridge the gap between classic literature and youth interest, thereby facilitating cultural heritage tourism.

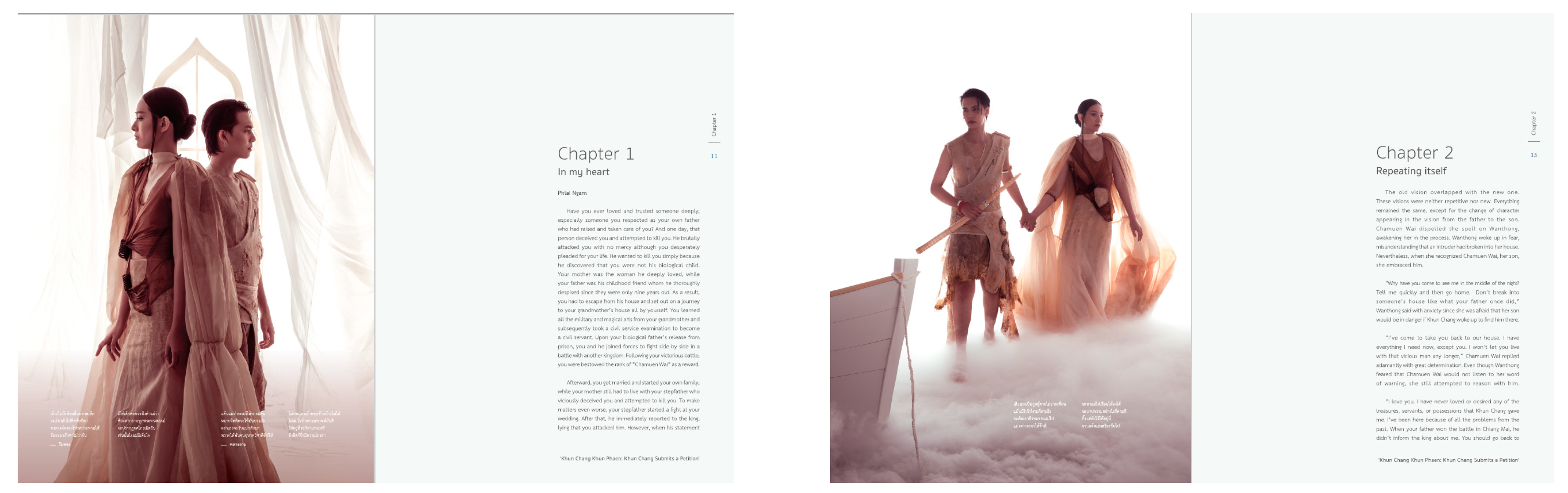

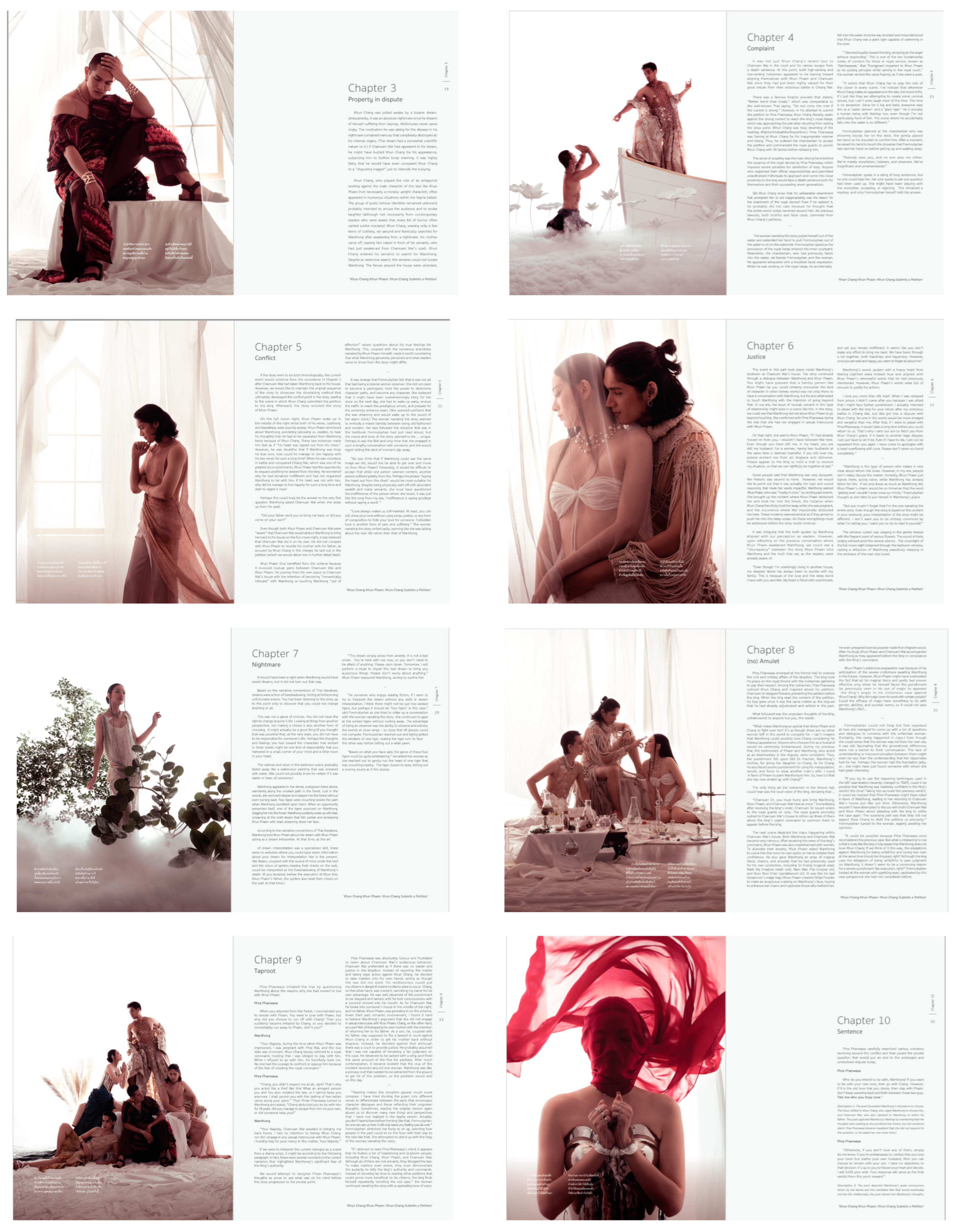

4.2. Phase 2: Creating a Multimedia KCKP E-Book to Facilitate Cultural Heritage Tourism for Youth

The researcher utilized data from the literature review, as well as 600 on-site questionnaires, for the production stage of Phase 2. The primary objective of this phase was to develop an e-book based on the classic literature KCKP that was intended to facilitate cultural heritage tourism in the Suphan Buri province for young people.

As a consequence, the researcher and their team shortened the long formal story from the official textbook of high school students (grade 12) to accommodate the reading preferences of young people. The story is also adapted from the original plot to be more readable in the present day while maintaining the integrity of the original story. This was achieved by introducing an additional character who represented youth and dividing the long story into 10 chapters. Additionally, the researcher and their team modified costumes to be more reminiscent of fantasy and arranged them in a studio according to the results of participant preferences.

Consequently, the researcher and their team produced three video clips that depict the actual heritage locations in the KCKP story to promote cultural heritage tourism in the Suphan Buri province: (1) Wat Khae (Khun Phaen’s residence and the giant tamarind tree); and (2) Wat Pa Lelai (Khun Chang’s residence, Luang Pho To, and mural paintings). All of these locations were filmed and uploaded on the YouTube channel “Revive Thai Literature.” Subsequently, the researcher requested the International Standard Book Number System number (978-616-604-330-3) from the National Library of Thailand [

57]. The researcher uploaded the 50-page free e-book in both Thai and English to Google Drive at the following URL:

http://bit.ly/3GsWYiu (accessed on 1 September 2023) and promoted the multimedia e-book on a Facebook page under the name “Revive Thai Literature” in September 2023.

In summary, the multimedia KCKP e-book for cultural heritage tourism presented in

Figure 7,

Figure 8,

Figure 9 and

Figure 10, which was adapted from classic literature, was developed as a result of design guidelines from

Figure 6.

4.3. Phase 3: Evaluation of the Multimedia KCKP E-Book Using the Four Factors of the Kirkpatrick Evaluation Model

The third phase employed quantitative research to gather results from 100 participants who completed an on-site questionnaire during the KMITL Expo exhibition in Bangkok from 1–3 March 2024, as illustrated in

Figure 11. This multimedia e-book was assessed using four variables from the Kirkpatrick Evaluation Model [

58], as illustrated in

Table 6. The objective of this phase was to assess the KCKP e-book in its entirety aligned with the aim of this research.

The study included high school and university students (aged 18–25) who attended the KMITL Expo 2024 exhibition. The National Statistical Office, Ministry of Information and Communication Technology [

54], reported a total of 2,295,293 high school students and 1,016,588 university students in Bangkok. The sample size was determined by applying Yamane’s formula [

55] with a confidence coefficient of 90% and an error margin of 10%. The sample size was determined to be 100 individuals. Consequently, a sample size of 100 individuals was employed in this investigation.

Initially, participants were requested to utilize an interactive kiosk to peruse and read the narrative of the KCKP e-book. Next, they were requested to complete the on-site questionnaire, which consisted of three sections: (1) demographic profile (gender, age, education), presented in

Table 7; (2) Kirkpatrick Evaluation Model, displayed in

Table 8, which utilized a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree and 5 = strongly agree); and (3) an open-ended question about recommendations. The questionnaire was completed within a range of two to three minutes. In February 2024, the questionnaire’s flow, length, and respondent comprehension were evaluated using 10 youths during a pilot test. The IOC index was employed by three experts to evaluate content [

56]. The IOC data demonstrated that the content validity of all questionnaires was rated at least 0.5.

Table 7 illustrates demographic data from the 100 participants showing that the majority were female (62%), 95% were aged 18–20 years, and 47% were studying for an undergraduate degree. In Section 2, presented in

Table 8, the information from 100 respondents was gathered using a Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree” (1) to “strongly agree” (5). In addition, regarding reliability, the researcher performed tests using Cronbach’s alpha, which was found to be 0.787 for all 15 questions, meaning Section 2 showed a reliability of 78.7%.

Overall, this multimedia KCKP e-book was evaluated using four factors: reaction (mean = 4.55), learning (4.49), behavior (4.54), and results (4.60). Overall, it was evaluated positively on every variable. The “reaction” factor referred to “what participants think of the proposition” [

59] (p. 244). In terms of reaction, four questions aimed to obtain readers’ opinions when they read the KCKP e-book for the first time. The total mean for these questions was 4.55 (strongly agree) and S.D. = 0.28 (slight differences in answers). This highlights that most readers strongly agreed that this e-book is immediately interesting, relevant to their interests, useful, and makes literature more interesting. In addition, the “this e-book makes the KCKP literature more interesting” factor received the highest score (4.87).

McGinley [

59] explains “learning” as “what participants learn from the proposition” (p. 244). Five questions sought to discover what participants could learn from the KCKP literature and what would catch their interest. The total mean for these questions was 4.49 (agree) and S.D. = 0.63 (slight differences in answers). The factors about including fantasy in the content and images, “easy-to-read content”, “multimedia (still and moving images)”, and “photos” received the top three highest scores. This shows that most reviewers strongly agreed that they are willing to read the classic literature if it is adapted to include more fantasy or subjects beyond the ordinary. In this case, it was easy-to-read multimedia, a presentation compatible with the young generation.

The next term, “behavior”, refers to “the impact of the proposition” [

59] (p. 244). Three questions aimed to obtain the impact on readers during and after reading the KCKP e-book. The mean for these questions was 4.54 (strongly agree) and S.D. = 0.21 (slight differences in answers), illustrating that reviewers agreed that this e-book can impact cultural heritage tourism and increase interest in classic literature in this target group. The statement “This e-book may help youth to become more interested in the KCKP literature” received the highest score (4.77).

Regarding

Table 9, the one sample t-test was used to evaluate whether there was a significant difference between the mean scores across the three questions (interest in literature, tourism, and history) compared with the mean score of 4. As a result, the mean scores from the three questions (1) interest in literature (mean = 4.53, S.D. = 0.59); (2) interest in cultural heritage tourism (4.56, S.D. = 0.59); and 3) interest in history (4.72, S.D. = 0.47) were significantly higher than the population mean,

p = <0.001. The significant high mean score against the population mean may be due to the KCKP e-book meeting the aim of this research (more interest in literature, cultural heritage tourism, and history).

Regarding this factor, results are defined as “fitness for purpose of the proposition” [

59] (p. 244). Three questions aimed to evaluate whether the KCKP e-book matched the aim of this research (interested in literature, cultural heritage tourism, and history). The mean for these questions was 4.60 (strongly agree) and S.D. = 0.55 (slight differences in answers). The statement “This e-book got me interested in history and the identity of the Suphan Buri province” received the highest score, 4.72. In brief, regarding the “results” factor, the researchers adopted the recommendations from the first phase (600 on-site questionnaires) and created the KCKP e-book to match the aims of this research (three points), with a rating of 4.60 (strongly agree).

Phase 3: Answering the second research question, “Does the design guidelines interest young tourists in cultural heritage tourism, history, and classic literature?”

The evaluation of the multimedia KCKP e-book, created using the design guidelines from Phase 1, strongly indicates that it successfully interests young tourists in cultural heritage tourism, history, and classic literature. The results show a very positive response from the target audience, with an overall mean score of 4.60 (strongly agree) across the three evaluation questions in

Table 9. Specifically, the e-book generated strong interest in three key areas: (1) classic literature (KCKP) (4.53); (2) cultural heritage tourism (4.56); and (3) local history and identity (4.72). In summary, the design guidelines (

Figure 6), incorporation of local history, and use of fantasy elements have successfully bridged the gap between classic literature and contemporary youth interests, thereby facilitating engagement with history and cultural heritage tourism.

5. Discussion

5.1. Phase 1: Discussion

5.1.1. Barriers to Studying Classic Thai Literature

Regarding barriers, the top three issues that young participants agreed on included: (1) Thai literature lacks connection with the plot in the present (mean = 4.32), (2) Thai literature is difficult to understand because its vocabulary is obsolete (4.23), and (3) Thai literature study/teaching materials are not interesting (4.13). These points align with previous studies in that “students do not understand the vocabulary because it is antiquated”, “students lack modern and interesting learning materials”, and “the instructor focuses solely on reciting vocabulary” [

9,

10]. However, participants disagreed with problems including: (1) I don’t like literature lessons (2.12), (2) Thai literature is outdated (2.07), (3) I get bored (1.93), and (4) I don’t like the way I learn/teach Thai literature in class (1.91). These points are different from previous studies [

9,

10]. This may suggest that students remain engaged and do not become disinterested in studying classic literature in Thai language classes, provided the lecturers present material that is appropriate to their interests and incorporates engaging storytelling. Based on these findings, there is a significant opportunity to adapt literature to cultural heritage tourism.

5.1.2. Motivation for Studying Classic Thai Literature

In terms of motivation, most participants agree with eight issues and feel neutral on one issue. The top three motivations are as follows: (1) If Thai literature used multimedia (mean = 4.09), (2) If Thai literature used new presentation technology (4.02), (3) If Thai literature used moving images (4.01). Interestingly, seven of the eight issues received high scores from participants, meaning that young participants will be open-minded toward classic literature if it matches their motivations and interests. However, most participants felt neutral about famous people (e.g., actors, influencers) presenting the literature.

The results are consistent with the notion that the intangible cultural heritage of folktales can be revived if the younger generation, which has forgotten these traditions and stories, is supported [

30,

31]. Additionally, the National Heritage Board in Singapore [

60] and UNESCO [

61] have stated that cultural heritage tourism should be able to attract young tourists by uniting a variety of elements, including traditions, ways of life, buildings, songs, stories, folklore, myths, and folktales combined with new technology, which the younger generation understands, in order to attract the appropriate audience. Additionally, Lyngdoh [

30] argues that the new forms of media and technology can be used to revitalize local traditions by incorporating folklore (e.g., myths, legends, and folktales). Lovell [

34] argues that the application of fantasy can inspire readers who are in search of something beyond the ordinary and who wish to escape the mundane. Waysdorf and Reijnders [

37] and Lovell and Bull [

38] provide examples of how the Wizarding World of Harry Potter theme park can inspire tourists to visit by combining fantasy, literature, and tourism. Thus, these nine issues regarding motivations can be implemented in any investigation of antiquated literature.

5.1.3. How to Make Classic Literature More Interesting

The top three issues are as follows: (1) New technology and multimedia in literature (mean = 4.01); (2) For example, it can be staged in a studio with surreal/fantasy elements; it is not necessary to include real locations (3.61); (3) The plot can be adapted to the current era/target audience (3.55). This means that participants are ready for adaptation of old literature into the present. However, most participants disagree that “Stories should be modified into a short article” (2.05). They mostly commented that it is not about a short or long article, but it is about how to present the literature in a way related to their interests.

The highest-ranking issue, “New technology and multimedia should be used in literature to promote cultural heritage tourism”, is consistent with prior research. Previous research [

51,

61] supports that myths, legends, and folktales are considered cultural heritage and have the potential to enhance tourism through innovative presentation methods. Folktales are a representation of the diversity of living heritage, including the human race, locations, traditions, and cultures. Consequently, the local populace, particularly the younger generation, is essential in the preservation of intangible cultural heritage and the transmission of its elements (e.g., locations, narratives) to future generations and can utilize technology and media [

51]. Additionally, participants favor establishing themselves in the studio when creating images. This aligns with Kasemsarn et al.’s research [

62], which establishes that young tourists require a unique lighting technique to pique their interest. They anticipate observing something unique rather than realistic, similar to advertising photography. This is in accordance with the findings of previous research, which suggest that young people prefer “trendy content with historical knowledge” when connecting with the current trend, particularly on social media [

63,

64].

5.1.4. How to Adapt Classic Literature in Multimedia to Promote Heritage Tourism and History

Most participants agreed with all eight questions (multimedia with technology, film, YouTube, music video, interactive media, Facebook, Instagram, illustration, or fashion) for an average mean score of 3.67 (agree). Moreover, the top three were as follows: (1) The application of multimedia with new technology (mean = 3.95), (2) The application of a film (3.89), (3) The application of well-known YouTubers (3.67). This implies that the young participants agreed that classic literature can be adapted to promote cultural heritage tourism. These results are consistent with the findings of previous research, which suggest that numerous tourism industries fail to prioritize young tourists due to the assumption that cultural heritage tourism, which involves the use of antiquated literature, is not appealing to the younger demographic. Additionally, the advertising, media, and information regarding cultural destinations are excessively formal, antiquated, unfashionable, and inadequately tailored to their needs [

1,

2,

4,

5]. Furthermore, Zhan et al. [

64] recommend that researchers investigate the behaviors, needs, and habits of young tourists in order to develop a comprehensive understanding of how to attract them.

5.2. Phase 3: Discussion

Overall, this multimedia KCKP e-book was evaluated using four factors: reaction (mean = 4.55), learning (4.49), behavior (4.54), and results (4.60). These results related to previous studies [

34,

35] in that applying fantasy and fairytales can spark interest in heritage tourism. This is because fantasy or unattainable quests offer tourists something “beyond the ordinary” [

36] (p. 424) and an “escape from the everyday life” [

37], offering an “alternative reality.” Moreover, Kasemsarn [

2] argues that young tourists prefer interesting illustrations, trendy content with historical knowledge, and characters in the same age group as them. In this case, this research added a high school character as additional content to connect with the readers, who were presented with fantasy photographs.

Moreover, as evidenced by the participants’ interest in the KCKP e-book, history, and the identity of locations, several studies support that folklore, local literature, and historical reenactments can utilize new media to modernize history and connect its past and present lives [

24,

26,

27,

28,

29]. Additionally, research [

34,

38,

52] demonstrates that the incorporation of fantasy into ancient literature is a critical component of historical interpretation, which can help tourists establish a connection to the past and make them more interested in the historical information and locations. Additionally, the utilization of fantasy may facilitate readers’ comprehension of locations’ origin myths [

38].

In terms of interest in cultural heritage, the results were consistent with previous research on locations of significance in fiction or literature [

41,

45,

46]. This suggests that tourists may be attracted to literary locations that serve as the backdrops for novels, as these locations possess a unique significance and imagery. This is associated with the theory of “film-induced literary tourism” [

48](p. 149), as destinations in cultural heritage tourism may become more appealing and sought-after after the viewing of media. This e-book presents actual locations in the Suphan Buri province through video clips. Next, the provinces can be promoted as part of cultural heritage by employing heroes from local myths [

49,

50,

65].

6. Conclusions

This research aimed to create and evaluate design guidelines applying classic literature to the facilitation of cultural heritage tourism and interest in learning classic literature and history, specifically for youth presented in

Figure 6. To complete this study, the researcher and their team distributed 600 on-site questionnaires to Thai youth aged 18–25 in six provinces across six regions of Thailand with the barriers, motivations, making literature more interesting, and adaptations to cultural heritage tourism presented in

Figure 6. Next, regarding Phase 2, the multimedia KCKP e-book was created using the results of Phase 1, presented in

Figure 7,

Figure 8,

Figure 9 and

Figure 10.

In the evaluation stage in Phase 3, regarding the “results” factor, three variables (interest in KCKP literature, cultural heritage tourism in Suphan Buri, and history) matched the aim of the study and answered the second research question, “Does the design guidelines interest young tourists in cultural heritage tourism, history, and classic literature?” Results from one sample t-test showed that participants strongly agreed (mean = 4.60) that the KCKP e-book matched the aim of this research (more interested in literature, cultural heritage tourism, and history); a significant high mean score was received against a mean score of 4, p = <0.001. These findings affirm that the design guidelines effectively engage young tourists and promote an appreciation for cultural heritage and classic literature.

This research makes several mixed contributions to knowledge in the areas of cultural heritage tourism, education, and multimedia design. First, it proposes the design guidelines in

Figure 6 for the integration of classic literature to increase the motivation of young people to engage in cultural heritage tourism. The innovative guidelines can serve as a blueprint for similar initiatives globally, as they apply classic literature to support the education and tourism of young tourists. Moreover, it offers cross-disciplinary solutions and proposes the potential benefits of interdisciplinary approaches by combining different areas (literature, tourism, multimedia design) to solve problems related to youth engagement—in this case, problems with studying classic literature and the lack of motivation for cultural heritage tourism. Lastly, the research confirms previous study results that youth tourists can be interested in cultural heritage if they are interested in what is offered. By answering this, this research presents how modernizing the presentation of classic literature (multimedia e-book) and cultural heritage sites can contribute to making these cultural assets more attractive to young people. The results showed strong interest in the KCKP literature (mean = 4.53), cultural heritage tourism (4.56), and history (4.72), ensuring their relevance for future generations.

7. Study Limitations

Firstly, this research focused on youth aged 18–25 in Thailand, which may limit the findings to other cultural contexts or countries. Moreover, it does not account for potential differences in younger or older demographics. Secondly, due to the interactive kiosk’s limit, the final evaluation only included 100 participants from one province, despite the initial survey having 600 participants from six provinces. Next, this research only focuses on a single multimedia format, e-books, potentially overlooking other multimedia formats that might be effective for engaging youth. Lastly, this research relied primarily on quantitative data, potentially missing deeper insights than qualitative methods (e.g., interviews, focus groups) to receive more in-depth details.

8. Implications

8.1. For Cultural Heritage Sites

This work can be implemented at other cultural heritage sites by incorporating local or relevant literature into multimedia presentations for young tourists. Moreover, the approach can contribute to the preservation and revitalization of unfamous cultural heritage locations by applying local classic literature. Engaging more tourists, especially youth, at cultural heritage sites could increase local income and encourage them to contribute to preservation efforts.

8.2. For Literature Education

Regarding

Figure 6 and

Table 4 and

Table 5, educational institutions can leverage the findings to enhance the study of literature and history curricula. By understanding barriers and motivations in learning literature and applying multimedia elements, educators can make learning more dynamic and appealing. This result can overcome barriers to literature, such as “lack of connection to the present”, “obsolete vocabulary”, and “uninteresting learning materials.” Learning classic literature could be presented with multimedia and new technology materials, such as apps, e-books, and online platforms. These approaches could blend literary content with interactive technology, including videos, virtual tours, augmented reality, and virtual reality.

8.3. For Tourism Industries

Tourism industries and marketing agencies can use the results from Phase 1 to understand barriers to and motivations of young tourists. So, they could develop targeted campaigns aimed at attracting them and promotional materials that can create compelling narratives. Creating activities related to classic literature applies not only to cultural heritage tourism but also to fairytale tourism, creative tourism, literary tourism, or any type of tourism.

9. Future Study

Future studies can expand in the following ways: (1) Future research can adopt the literature review, methodology, and guidelines for different stories and cultural heritage locations. It could propose how various classic stories can be integrated into heritage tourism to engage youth globally. (2) The next studies should explore the effectiveness of different multimedia formats beyond e-books, such as mobile apps, augmented reality, virtual reality, and interactive websites. (3) This study targeted youth aged 18–25, high school and university students only. Future research can explore the impact of the design guidelines on different age groups, such as middle school students, adults, or older adults. (4) Future studies can explore the effectiveness of the implementation of these e-books at schools and universities, potentially enhancing literature and history learning in the classroom.