Abstract

This work studies one type of artistic production from the Viceroyalty of New Spain during the second half of the seventeenth century and the beginning of the following century. Furniture decorated with the technique of enconchado is studied to point out the influence of Namban lacquer as well as the relationship with enconchado painting, a better known and studied corpus than furniture, and also its link to Mexican lacquer, maque. The identification and study of three pieces of furniture that feature the enconchado technique, and a cross, probably decorated with maque, offer a complementary vision of the art of enconchado and allow us to consider enconchado furniture an independent artistic genre.

Keywords:

Namban style; lacquer; maque; enconchado furniture; New Spain; Puerto de Santa Maria; Alba de Tormes 1. Introduction

Currently, the study of enconchado art focuses on paintings, either in individual panels or in the form of folding screens. Scenes were painted in oil and tempera on many mother-of-pearl fragments that were adhered onto a plaster ground on a sometimes fabric-covered wooden substrate. One of the most notable characteristics of the art of the Viceroyalty of New Spain was its ability to absorb and appropriate foreign influences and fuse them with Indigenous traditions. Enconchado painting is a good example of this. The long tradition of American mother-of-pearl art, Spanish pictorial techniques, and Asian lacquer united to create a striking pictorial genre. Especially famous is the series La conquista de México (The Conquest of Mexico), produced in the last decades of the 17th century in and around the González brothers’ workshop in Mexico City. The recent exhibition La luz del nácar (The Light of Mother-of-pearl)1 organised in the Museo de América in Madrid has gathered a considerable number of works, including the series from the dukes of Moctezuma, and analyses the art of enconchado from the point of view of Asian influences. Previous studies exist on the parallels between Namban-style Japanese lacquer and enconchado painting [1,2,3]. The present work is focused on enconchado furniture and analyses this genre in comparison with works of Namban lacquer and Mexican lacquer. The methodology applied is a comparative study of the materials, techniques, and forms used.

The Spanish version of this essay, including all the original documentary references, is available as a Supplementary File.

2. The Arrival of Japanese Lacquer in New Spain

To confirm influences of Japanese lacquer in New Spain in the first place, we reviewed the documentary evidence of its reception in which the Manila galleon had a primary role.

Since Spain and Japan made contact towards the end of the sixteenth century, objects made with Japanese lacquer urushi were considered very valuable and they were chosen as a diplomatic gift. In 1584, Philip II received three lacquered objects, now lost, from three young Japanese Christians who were visiting him, known as the Tensho Legation, organised by the Jesuits [4]. Furthermore, the same monarch possessed several lacquered pieces considered Namban-style lacquer (henceforth known as Namban lacquer) [5].

When Tokugawa Ieyasu (1543–1616), the future Japanese supreme ruler, initiated contact with Spain via Manila at the end of the sixteenth century, urushi lacquer items were considered an appropriate commodity to send to the Philippine capital, as shown in the list of goods that its ambassador transported in 1599: fourteen chests, fifty-five boxes for mirrors, and two dressing tables, all of them “gold varnished” [6] (pp. 37–38)—clearly lacquerware decorated in the makie technique. As a consequence of the success of Japanese lacquer amongst the first Europeans who made contact with Japan, namely the Portuguese and Spanish, a new lacquer type specifically for European export arose in the last decades of the sixteenth century, called Namban lacquer, studied by different researchers [7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14]. This furniture of European style and use, decorated with the gold of makie and mother-of-pearl, was made between approximately 1580 and 1630 (Figure 1). The interest in this artistic genre amongst the Spanish and creoles in Manila and New Spain can be clearly seen in the documentation of the period.

Figure 1.

Writing desk from the Convent of Santa María de Jesús, Sevilla, Namban lacquer, 1580–1630. Photograph by Y. Kawamura.

Antonio de Morga (Seville, 1559-Quito, 1636), Lieutenant Governor and Captain General of the Philippines between 1595 and 1603, mentioned in Sucesos de las Islas Filipinas (Successes of the Philippine Islands) the goods that arrived from the port of Nagasaki and said: “desks, boxes and wooden trunks with varnish and curious work […] serve as shipments to New Spain”2 [15].

A few years later, the Governor, Rodrigo de Vivero (Mexico, 1564-Orizaba, 1636), who knew of Japan after being shipwrecked on its coast, wrote in Relación de Japón (Relation of Japan) about Japanese luxury goods sent to New Spain: “Japan does not have useful returns for New Spain, because paintings, desks, screens, and what was brought the last time, is not merchandise for ordinary people […] The varnish of the desks and sideboards, which is like a tree resin, has no equal, and therefore they have bizarre beauties of this genre”3 [16].

The Spanish navigator and explorer Sebastián Vizcaino (1548–1628), who was in Japan between 1611 and 1612, commented: “Some gentlemen from Mexico, who had ordered him to carry back maqui as a gift for them and their relatives”4 [17] (p. 380), [18] (p. 72). The “maqui” that Vizcaino was talking about was, without doubt, lacquer. The word was derived from the Japanese makie, a golden lacquer decoration technique and almost synonymous with the art of Japanese lacquer.

On the other hand, the oidor (judge) of the Audiencia (Court) of Manila, Juan Manuel de la Vega, wrote a letter in 1612 to Juan Ruiz de Contreras, Secretary of the Real y Supremo Consejo de Indias (Council of the Indies) in Madrid5, in which he spoke of the shipment in 1610 of “a golden writing desk from Japan with silver trim and key” and another sent in 1612 “a large golden writing desk with silver trim and a key”6 as a wedding present. The letter reveals that the oidor of Manila chose an object of Namban lacquer as a present for his superior.

Lucas de Bargara Gaviria, a military man who moved up the ranks from captain to field master in 1611 in the Philippines for defending Ternate Island against attacks from the Dutch, sent to Pedroso (La Rioja), his home town, a chest, two lecterns, and three pyxes, probably to celebrate his promotion. All of them were Namban lacquerware7, of which the chest is still preserved in good condition.

The Governor of the Philippines, Alonso Fajardo, at his death in 1624, owned, according to his inventory of goods, different objects from Japan, amongst which nineteen pieces are considered Namban lacquerware: lecterns, desks, writing desks, small boxes, and beds [19].

This documentary evidence, dated from the first quarter of the seventeenth century, coincides with the period of Namban lacquer and clearly demonstrates the appreciation for lacquered works coming from Japan to Manila and New Spain, both connected by the Manila Galleon [20,21,22].

There are few Namban lacquer objects currently preserved in Mexico; probably, many pieces were sold outside of the country. Those that we believe to have been preserved in New Spain from the viceregal period are a pyx from the Basilica de Guadalupe (Figure 2), a coffer, and two writing desks in private collections. However, a notable number can be found in Spain which we believe arrived via New Spain [23]: some based on the historic documentation and others because they carry added American silver decoration (Figure 3). Other objects, especially oratories, kept in different museums and collections worldwide, contain paintings from New Spain (Figure 4), clear evidence that they had been in New Spain8.

Figure 2.

Pyx from Museo de la Basílica de Guadalupe, Mexico City, Namban lacquer, 1580–1630. Photography by Luis Fauvet.

Figure 3.

Writing desk converted to a tabernacle, from the Convent of San Juan de la Penitencia, Alcalá de Henares (Madrid), Namban lacquer, 1580–1630. Photography by Rafael Suárez Pascual.

Figure 4.

Oratory, from Fundación Cultural Daniel Liebsohn, Mexico City, Namban lacquer, 1580–1630. Photography by Fundación Cultural Daniel Liebsohn.

3. The Influences of Japanese Lacquer in New Spain

3.1. Maque and Enconchado

It is widely recognised that in the same period, Japanese folding screens were exported from Japan to New Spain, where they were widely accepted, and the art of Mexican folding screens developed. Also the Spanish term “biombo” (folding screen) comes from the Japanese “byōbu” [24,25]. The same phenomenon must have occurred with Namban lacquer.

The first artistic genre where Japanese lacquer influence can be noted is the art of Mexican lacquer, or maque—derived from the Japanese term makie (a Japanese lacquer decoration technique using metal powders, usually gold). The technique was applied on gourds and dates from the pre-Hispanic period [26,27]. From the second half of the seventeenth century, the decoration on artistic objects such as small coffers evolved with similar characteristics to those of Namban lacquerware: dense decoration with vegetal and bird motifs surrounded by borders decorated with repeating motifs. Amongst the works considered to be from the eighteenth century, there are two works of Olinalá lacquer that are reminiscent of Namban lacquer: a small coffer from the Museo Franz Mayer and another from the Museo Regional de Michoacán (originally from the Museo Nacional del Virreinato)9. On an orange background, densely packed vegetal motifs and red birds with white and blue–green touches, and borders with repeating motifs, can be observed. All these details recall Namban lacquer decoration, although the background is not black, a notable difference, but red lacquer was practised in China and in the Ryuku Kingdom, and this type of production could also have reached New Spain. In the meantime, the analysis of documentary references to different kinds of Asian, Mexican, and European lacquerware reveals that none of them were exclusively known as maque. All of them were sometimes named maque, while other times they were considered “painted” pieces, and some others they were simply described as furniture “from China”, “from Japan”, or “from Michoacán” [20,21,22].

The second genre is enconchado painting (Figure 5), which the González brothers, Miguel and Juan10, brought to the pinnacle of craftsmanship in the last decade of the seventeenth century, but which swiftly declined in later generations [28,29,30,31,32]. Although there were some suggestions as to the foreign origins of Miguel González [33], [34] (p. 300), the studies that revealed the names of his parents [31,35,36] seem to support his American origins. According to Tovar [32], Tomás González of Villaverde, father of Miguel and Juan, appears in a document dated 1689 as “a master of maque painting” and his son Miguel as “an official of the aforementioned art of painting”. This description of the profession of both makes us think that Tomás painted panels with maque, and his son Miguel did the same, but we know that a decade later, Miguel and his brother Juan created enconchado paintings with oil and tempera.

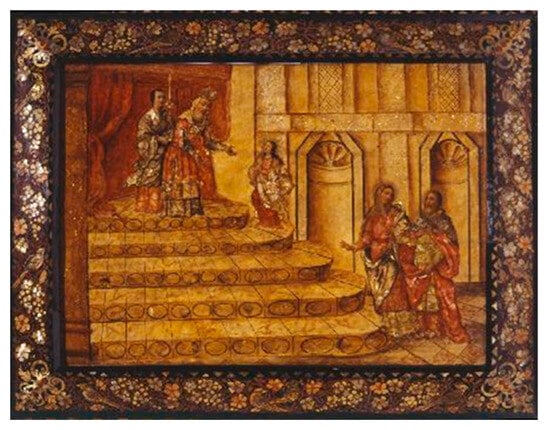

Figure 5.

La Conquista de México, from the dukes of Moctezuma’s collection, private collection, enconchado painting, end of the seventeenth century. Photograph by A. Garcia Barrios.

Furthermore, these facts suggest the presence of a missing step in the evolution of enconchado painting. Prior to the full development of enconchado painting with oil and tempera, there could have been maque painting with Mexican lacquer and probably with mother-of-pearl. There is no evidence for when Miguel Gonzalez started to use mother-of-pearl in his paintings, and no work of Mexican lacquer with inlaid mother-of-pearl is either documented or preserved. What is certain is that the document from 1689 and Miguel Gonzalez’s preserved works show the closeness between the art of maque and the art of enconchado painting. However, we are aware that the word maque does not only or always refer to pre-Columbian-rooted Mexican lacquer work, and there is no evidence that the Gonzalezes ever used pre-Columbian-rooted lacquer techniques.

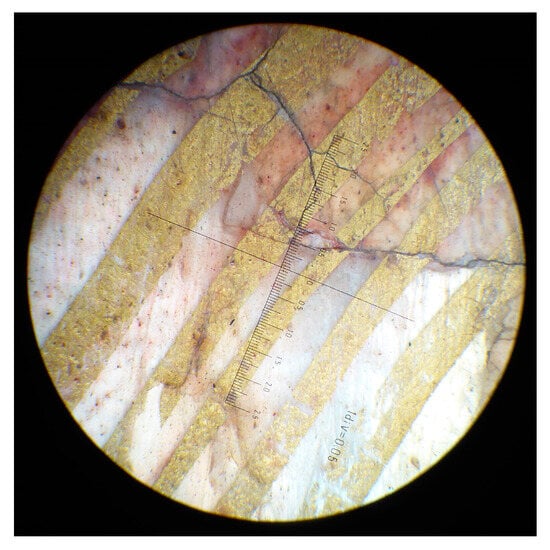

On the other hand, the influence of Japanese lacquer in the Namban style can be noted in the Gonzalez brothers’ enconchados. Ocaña focused on the marginal areas such as the decorated frames, where there are plant and bird motifs in yellowish tones on a black background, which show a strong similarity to the motifs of Namban lacquer [2,3]. Apart from the motifs highlighted by Ocaña, the golden brushstrokes applied on the Gonzálezs’ panels, with a fine gold powder, and with some of them applied over the mother-of-pearl, create a brilliant and iridescent effect, very similar to that of Namban lacquer (Figure 6 and Figure 7).

Figure 6.

Detail in La Conquista de México, from the dukes of Moctezuma’s collection, enconchado painting, at the end of the seventeenth century. Photograph by Y. Kawamura.

Figure 7.

Detail in the chest from Parish of Pedroso (La Rioja), Namban lacquer, 1580–1630. Photograph by Y. Kawamura.

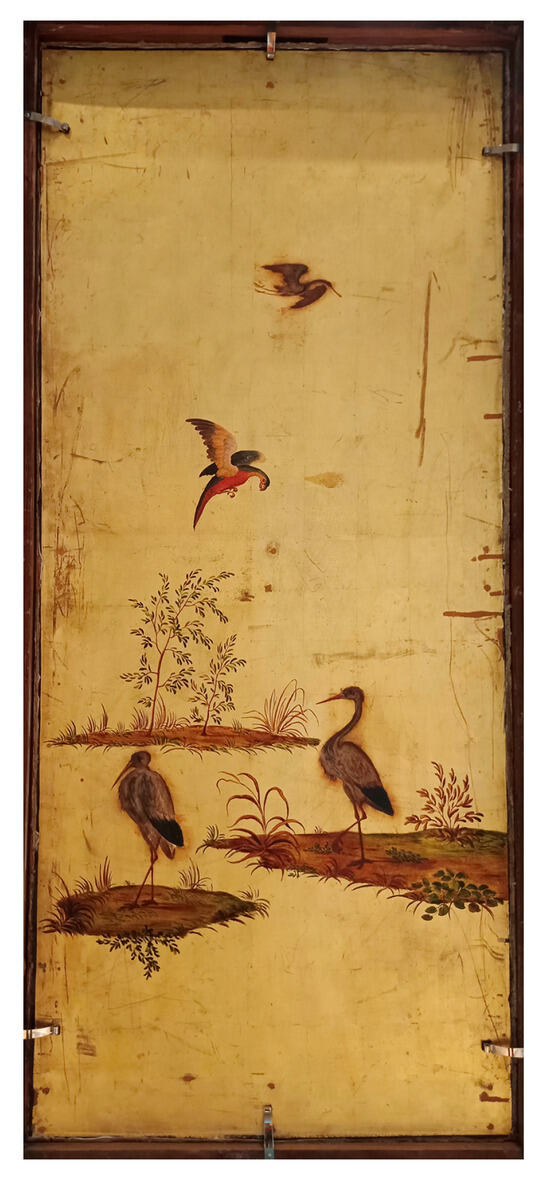

Another similarity between the González brothers’ workshop and their circle and Japanese art can be found in the twenty-four panels from the dukes of Moctezuma’s collection, the subject of a recent study [34]. On the backs of these panels, there are paintings of water landscapes with birds on a golden background, clearly taken from the paintings on Japanese folding screens by the 17th-century Kano school, which spread the iconography of birds and flowers (kachōzu) and the use of golden backgrounds, but painted by non-Japanese artists (Figure 8). This is a surprising discovery, with the artist(s) still unknown, but is one that could indicate the presence of painters of Japanese origin, or second generation, settled in New Spain working in the González workshop. This is conjecture without documentary evidence to date, but it seems reasonable.

Figure 8.

Painting of a landscape on the reverse of the enconchado panels of La conquista de México from the dukes of Moctezuma’s collection. Private Collection. Photograph by Y. Kawamura.

It is probably right to imagine that in the mid-seventeenth century, after the stylistic impact of folding screens and lacquers from Japan, the process of the assimilation and appropriation of these arts began. The fusion with European and Indigenous elements, initiated by skilled artists and artisans of New Spain, was perhaps also fused with the contributions of artisans of Japanese origin. In the period, enconchado furniture, the main object of this study, had to be produced.

Currently, only three objects are known that can properly be called enconchado furniture: a tabernacle preserved in the parish of Allo (Navarre); a fragment of a piece of furniture, perhaps a small door or front of a drawer, preserved in the Museo de América in Madrid; and a lectern from the Museo Carmelitano in Alba de Tormes (Salamanca).

3.2. Enconchado Tabernacle from Allo

The tabernacle of the parish of Allo (Navarre) was identified and studied as enconchado [35,36,37] and later examined in comparison with Namban lacquer [6] (pp. 98–99) (Figure 9). The tabernacle is a domed hexagonal temple, a distant echo of the tabernacle in El Escorial, designed by Juan de Herrera; thus, it could be imitating a Spanish design that arrived in New Spain, although there was production of this type of tabernacle, hexagonal and domed, with Namban lacquer, as demonstrated by an example in the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem (Massachusetts)11 [11] (p. 194).

Figure 9.

Enconchado tabernacle from Parish of Allo (Navarre), late seventeenth century. Photograph by Larrión and Pimoulier.

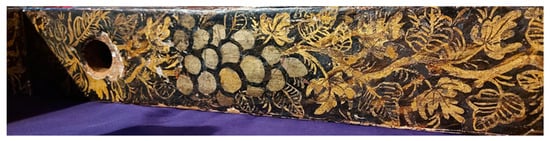

Upon examining the details, similarities with Namban lacquer are even more obvious. The dome is decorated with vine leaves and bunches of grapes, making reference to the eucharist, and on the body there are six arches and the Mystic Lamb and saints. Although the background is blue and not black like Namban lacquerware, the motifs are elaborated with thin inlaid mother-of-pearl and a soft semi-transparent yellow tone and powdered gold that trace the shapes. There are no other colours (Figure 10). This detail is directly associated with the makie aspect of Japanese lacquer. The shapes and combination of mother-of-pearl and gold of the vine leaves and bunches of grapes are very similar to the motifs of Namban lacquerware (Figure 11). Also, the golden brushstrokes that paint the details on top of the inlaid mother-of-pearl on the arches, correcting or dissimulating the irregular shapes of the adhered mother-of-pearl, is a technique observed in Namban lacquer and also in enconchado painting [38] (p. 17), [39] (p. 28). Furthermore, in the marginal areas, one can see narrow strips with undulating vegetal motifs similar to scrollwork or with repeating motifs that feature in the works of Namban lacquer. And the polished and brilliant aspect that the work offers to a certain extent reminds us clearly of Namban lacquer.

Figure 10.

Detail of the tabernacle from Parish of Allo (Navarre). Photograph by Y. Kawamura.

Figure 11.

Detail in a chest from a private collection. Namban lacquer, 1580–1630. Photograph by Y. Kawamura.

The tabernacle was recorded as being in the parish before 1718 [36]; thus, the possibility that it was made in the second half of the seventeenth century is acceptable.

3.3. Fragment of Enconchado Furniture from the Museo de America in Madrid

A rectangular fragment from a piece of furniture preserved in the Museo de America in Madrid12 (Figure 12) features a scene of Atlas and Vulcan, which could be classified as an enconchado painting. However, the scene is inside an arch flanked by columns that recalls the central drawer of writing desks of Spanish origin that were made in considerable quantities with Namban lacquer (Figure 1). The black background decorated with golden bouquets also evokes Japanese lacquer, but due to the scarcity of information and the current fragmentary state, we cannot glean more. In fact, we do not know what adhesives are applied nor if the visible lustrous texture is due to the subsequent layer of varnish or because of the use of maque.

Figure 12.

Fragment of enconchado furniture, 1625–1725. © Museo de America in Madrid.

3.4. Enconchado Lectern from Alba de Tormes

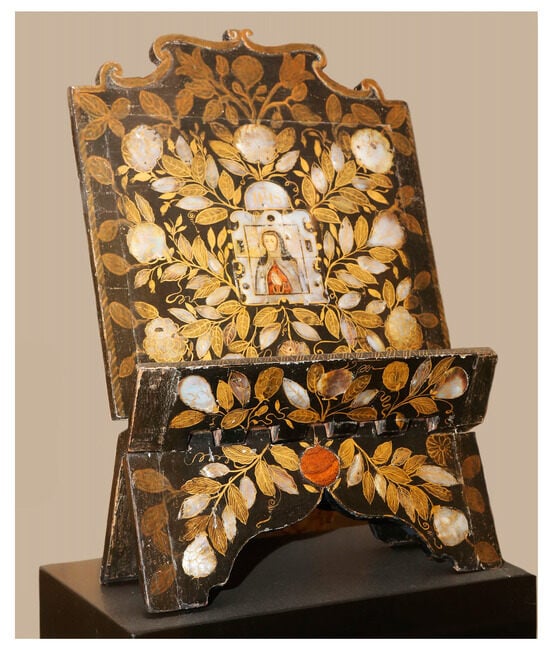

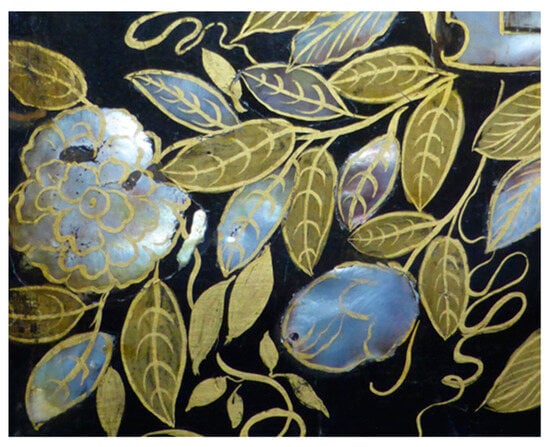

The case of the enconchado lectern preserved in the Museo Carmelitano in Alba de Tormes (Figure 13) offers more interesting considerations with relation to Namban lacquer [23]. It was probably made earlier than the two previous works. The form of the lectern is exactly the same as that of the Namban lectern (Figure 14), that is to say, foldable with two interlocked panels. Different to the objects mentioned above, the background is black, like Japanese lacquer, and several fine pieces of mother-of-pearl are inlaid in the shape of leaves and flowers. Even in the absence of a materials analysis, the lustrous appearance of the black points us towards the Mexican lacquer maque, made with the fat extracted from the aje insect (Coccus axin), dissolved in chia (Salvia hispanica) oil and coloured with soot. The chromatic combination of the black, the gold, and the mother-of-pearl is identical. The monogram IHS (Jesus Christ), that appears in large letters on the majority of Japanese lecterns also appears on this one. The flowers look like camellias, very common in Namban lacquer, and the curved extremities of the bouquets follow the Japanese model. It is clear that the maker of this lectern had as its model a Namban lacquer lectern and tried to copy it with materials and techniques available in New Spain.

Figure 13.

Lectern from Museo Carmelitano in Alba de Torres (Salamanca), enconchado and maque, second half of the seventeenth century. Photograph by José Luis Gutiérrez Robledo.

Figure 14.

Lectern from Parish of los Sagrados Corporales, Darroca (Zaragoza), Namban lacquer, 1580–1630. Photograph by Rafael Suárez Pascual.

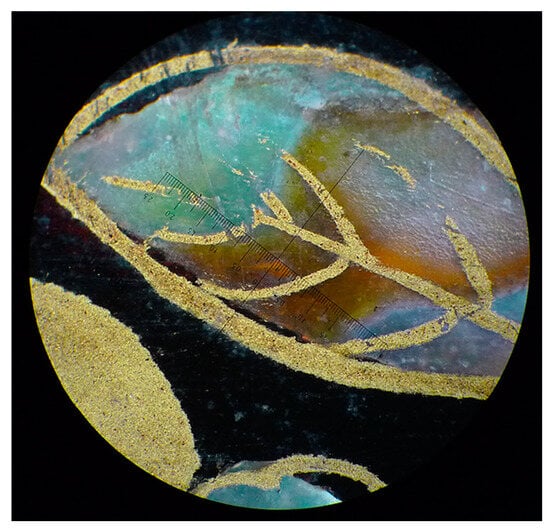

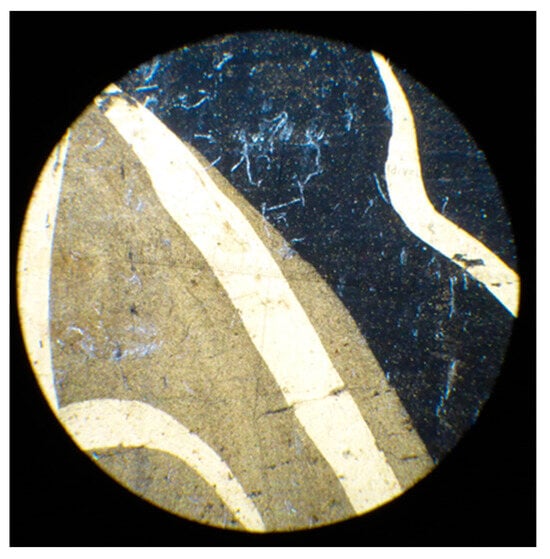

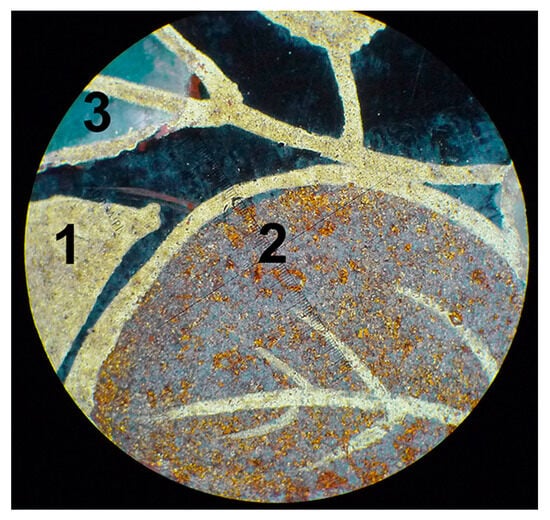

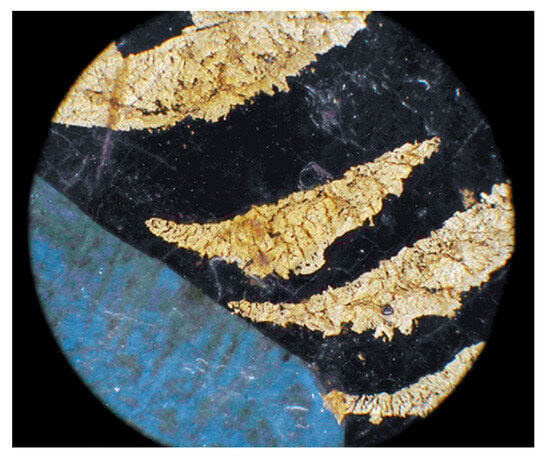

Three different types of leaves can be observed: completely golden leaves, orange-coloured leaves with their veins and outlines painted with gold brushstrokes, and leaves made of mother-of-pearl with the same gold brushstrokes on top. The gold leaves are made from very finely powdered gold applied very densely. The orange-coloured leaves are the result of applying the gold powder less densely (Figure 15 and Figure 16). The three methods used to create the leaves are exactly the same as the techniques applied in Namban lacquer. In Japanese, three terms are distinguished: hira makie (flat and dense gold-powder decoration), nashiji (less dense gold-powder decoration) and raden (mother-of-pearl inlay) (Figure 17). The way in which the veins or edges are added is called tsukegaki (added gold drawings). The enconchado lectern not only imitates the form, motifs, and exterior elements of a Namban lacquer lectern, but also the techniques of expression are very similar. Although the vegetal and floral motifs are very crude in comparison to Japanese lacquer motifs, and they certainly do not come from the trained hands of a Japanese craftsman, it might be reasonable to wonder if the enconchado lectern artist had technical knowledge of Japanese lacquer decoration.

Figure 15.

Detail in the lectern from Museo Carmelitano in Alba de Torres (Salamanca). Photograph by Y. Kawamura.

Figure 16.

Detail in the lectern from Museo Carmelitano in Alba de Torres (Salamanca). Photograph by Y. Kawamura.

Figure 17.

Detail in the chest from Parish of El Salvador, Pedroso (La Rioja), Namban lacquer, 1580–1630. 1: hira makie. 2: enashiji. 3: raden. Gold lines on top of 2 and 3: tsukegaki. Photography by Y. Kawamura.

The great similarity in the techniques of applying gold powder in different densities might suggest the presence of a Japanese person, not necessarily an expert in Japanese lacquer decoration, but with sufficient knowledge about the use of gold powder and mother-of-pearl in lacquerware. The presence of several Japanese people in New Spain during the seventeenth century is documented. Some of the companions that arrived with the trader Tanaka, in 1610, and with the samurai Hasekura (Keicho embassy), in 1614, and the companions who crossed the Pacific with Friar Diego of Santa Catalina in 1617 did not return to Japan [40]. Furthermore, some of the Japanese Christians exiled in Manila were able to reach New Spain. Luis de Encío (Japan, 1595?–Guadalajara, 1666) and Juan Páez (Osaka, 1608?–Guadalajara, 1675) constitute the cases studied of the Japanese people who lived in Guadalajara in that century [40,41,42]. On the other hand, in the face of Christian persecution in Japan, the artisans who had manual skills, such as lacquer artisans, were the individuals who could more easily move from their place of origin compared to the peasants, who were very tied to the land.

A comparison between this lectern and the tabernacle from Allo suggests that the lectern was made at an earlier date than the tabernacle, as it is closer to Namban lacquerware. On the tabernacle, gold brushstrokes made using gold powder can be observed, but the application of less dense gold powder to create the orange colour is not seen. The leaves of this colour are painted with semi-transparent paint, moving further away from the Japanese technique.

The image of Saint Teresa who appears inside a rectangular frame situated in the centre is the key to date the work. The broken external line of the frame indicates the transition from mannerism to baroque or early baroque. Taking into account that in New Spain, this style lasted longer than in Europe, its date could be considered as being from the middle or second half of the seventeenth century, with due caution for the lack of documentation.

Saint Teresa’s iconography developed alongside the initiation of the process of her beatification, which culminated in 1614 and, after her canonisation in 1622, her image spread even more. The figure is of the saint in prayer, without a quill or book, nor with big gestures of transverberation or mortification in the painting by the Mexican painter Cristóbal Villalpando in recent decades of the century (Museo de Carmen, Mexico). She is represented as “teacher of prayer” following the model of the saint painted by the painter Friar Juan de la Miseria in 1575 (Monastery of Las Carmelitas Descalzas in Seville) [43,44]. The image of the saint could have been painted in the second half of the seventeenth century, the century in which the Namban lacquer lectern form was already well known in New Spain. The lectern is a type of Namban lacquer furniture that is preserved in large numbers today, and was therefore widely produced.

Enconchado furniture, though scarce in number, appear closer to Namban lacquerware than enconchado paintings. Could this fact indicate that the furniture was conceived before the painting?

Remembering that, in 1689, Tomás González was considered the “master of maque painting” [32], Tomás could represent a generation that progressed maque furniture with mother-of-pearl inlays towards enconchado painting. The enconchado panels that we know of so far are paintings made with oil paint and tempera; however, previous to this there may have been works made with maque and mother-of-pearl that accounted for Tomás’ profession [39] (p. 31). Therefore, the lectern could be proof, currently the only example, of that earlier phase: enconchado maque. Analysis on other extant enconchado paintings may reveal maque as an ingredient.

A question still remains. Why do not Mexican lacquer works dated from the viceregal period contain mother-of-pearl except this lectern? This absence of maque with mother-of-pearl is probably due to the fact that the majority of the historical works that we know of are from the eighteenth century, except 17th-century Periban lacquer, and with the turn of the century came a change in taste. As Ocaña rightly points out [45], the eighteenth-century Mexican maque style owes a great debt to the European chinoiserie fashion that arose in that century in Europe and spread to New Spain.

Actually, the taste for mother-of-pearl in lacquerware had already fallen out of fashion halfway through the seventeenth century in Western Europe (the Netherlands, France and England, for example); however, in Venetian lacquer, mother-of-pearl inlay was still fashionable in the second half of the 17th century.

In fact, the Japanese export lacquer of that time—primarily destined for the Dutch traders, who were authorised to maintain a limited and controlled trade with feudal Japan—changed its style. This new production, called the “pictorial style”, is decorated using only golden makie with less density than Namban lacquer. The Central European lacquer workshops responded to the influence of gold decoration on black lacquer early, for example, in Berlin as early as 1690–1695 by Gérard Dagly [46,47]. Other European lacquered works that decorate interior spaces, such as the Chinese Cabinet in the Royal Palace of Turin (1734) or the University of Coimbra’s Biblioteca Joanina (1720–1730), consist of gold motifs on top of a black or red background without mother-of-pearl inlay.

Chinoiserie fashion arrived in Spain with the Bourbons, specifically with Phillip V and Elizabeth Farnese. Their taste for lacquerware without mother-of-pearl inlay can be seen in the Chambre du lit in the Royal Palace of La Granja de San Ildefonso (1735), where the dismantled panels of the multi-coloured Chinese Coromandel-style folding screens and their European imitations were installed. This distancing from mother-of-pearl iridescence in the Spanish court could also explain the end of the arrival of big enconchado painting panels to Spain. This would have triggered a recession of artistic activity in New Spain and the end of the González’s workshop. Large enconchado panels, such as the five series of La conquista de México, were ordered by the Spanish nobility, for example by the Count of Galve or the Count of Moctezuma, both of whom were viceroys of New Spain in the late Habsburg period [39] (pp. 65, 69). They were sent to Spain in the last years of Carlos II’s reign, the last Habsburg monarch. With the arrival of Phillip V, who brought the tastes of Versailles to Spain, the artistic style of the court drastically changed. It appears that the enconchado panels had no place in this new situation [39] (pp. 55–56).

Although, in New Spain, there was continued demand for this artistic production for a time, since there are enconchado paintings dated from the eighteenth century, such as an Our Lady of Guadalupe, dated in the year 1734 in a private collection13 [48] (pp. 60–61).

3.5. Other Practices Combined with Mother-of-Pearl Inlay

A fine Namban lacquer chest is preserved in the Museo de Navarra. It came from the Guendulain Palace, Pamplona (Navarre), and belonged to the marquisate of the Real Defensa, whose first marquis was noted for his military activities in Cartagena de Indias. There are some old repairs to the chest. The detached and lost mother-of-pearl pieces were replaced by other mother-of-pearl fragments with different iridescence or by broken fish-shaped fragments—clearly reused pieces—that are adhered with a dark and semi-transparent material that could be maque (Figure 18). In Spain, there are no known fish-shaped mother-of-pearl works, and taking into account the long tradition of mother-of-pearl art in Central America [49,50], it seems reasonable to assume it was repaired in New Spain. The artisan who fixed the chest may have had knowledge of Mexican lacquer and enconchado.

Figure 18.

Detail in the chest from Museo de Navarra, Namban lacquer, 1580–1630. Photograph by Y. Kawamura.

Another chest with the same type of repair work (private collection) presents some small fish-shaped mother-of-pearl fragments and retouches with gold powder brushstrokes that resemble the enconchado painting (Figure 19). These historic repairs also seem to point to the connection of maque and enconchado.

Figure 19.

Detail in the chest from private collection, Namban lacquer, 1580–1630. Photograph by Y. Kawamura.

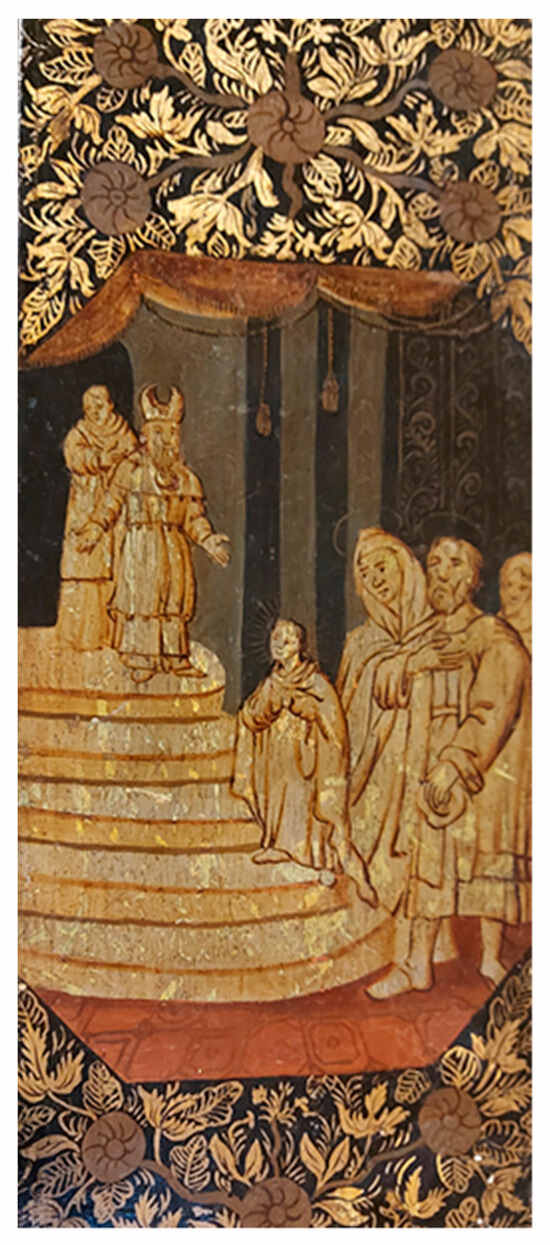

4. Nazarene Cross from Puerto de Santa María

An interesting and unique cross is preserved in Puerto de Santa María (Cadiz) (Figure 20), which belongs to the Hermandad de Nuestro Padre Nazareno y Nuestra Señora de los Dolores (Brotherhood of Our Father of Nazarene and Our Lady of Sorrows). It is in use in the Holy Week procession each year and is supported by a life-sized figure of Christ. There is no documentation about the arrival of the cross at the church. The cross is large: a total height of 268 cm, horizontal arms of 170 cm, and a thickness of 7 cm. It is relatively light in weight given that it is made up of boards mounted on a frame, and, therefore, it is hollow inside. Thirteen scenes of la Pasión de Cristo (the Passion of Christ) and la vida de la Virgen María (the Life of the Virgin Mary) can be found on both the front and back, respectively, and the frames of these scenes and the edges of the cross are profusely decorated with vegetal motifs. At first sight, it evokes the work from the viceroyalty of New Spain14 [51,52], and its original use could have been catechetical and processional for the evangelisation of the American population by the missionaries [53].

Figure 20.

Nazarene Cross from the Brotherhood of Nuestro Padre Nazareno y Nuestra Señora de los Dolores, in Puerto de Santa María (Cadiz), maque. Photograph by Y. Kawamura.

Wood analysis has revealed that it is made from Cedrela odorata (Spanish cedar), a timber native to Central America [54]. Based on the scientific data that indicate it was created in the viceroyalty of New Spain, a study of its painting was conducted. The work of at least three painters can be detected on the cross: one (or even two) for the biblical scenes, another for the decoration of the frames of those scenes, and a third for the decoration of the edges. The main panels and those for the edges were painted separately before being mounted. The twenty-six scenes are visually framed and separated from one another in rectangles with chamfered corners. The depicted scenes show a drawing-like style, based on Renaissance engravings circulating in New Spain (Figure 21). Some of the scenes are almost identical to other enconchado paintings. In particular, the Presentación de la Virgen en el Templo (Presentation of the Virgin at the Temple) is very similar to two other works of the same name in the Museo de America in Madrid15 (Figure 22). The unique temple with circular stairs even appears in a work attributed to the González brothers in a private collection (Figure 5). The majority of the scenes exhibit a special luminosity, which is mainly due to a silver layer under the painting, as well as the application of fine, gold brushstrokes as a glaze in different parts [54].

Figure 21.

Detail in the Nazarene Cross. Scene of the Presentación de la Virgen en el Templo. Photograph by Ana García Barrios.

Figure 22.

Presentación de la Virgen en el Templo, from the series Vida de la Virgen from Museo de America in Madrid, enconchado painting, 1676–1725. © Museo de America in Madrid.

The shiny look of the cross, however, is primarily due to the vegetal decoration that surrounds the scenes, painted with gold over a glossy black background. The black could be maque, given that, at one end, a shiny black coating can be seen, applied over a white calcite base and reddish layer, perhaps of red clay powder (Figure 23). This brilliant black is comparable with the black from eighteenth century maque works, for example the background of a square tray from the Museo de Artes e Industrias Populares in Pátzcuaro16 (Figure 24). The gold parts look as though they are gold powder and gold leaf. The enlarged images show wrinkled gold (Figure 25) which suggests gold leaf, which was probably attached over the traced motifs with some kind of adhesive which could be maque; however, in other parts of the cross, gold powder brushstrokes can also be observed. Additionally, fine particles of gold are dispersed over the surface.

Figure 23.

Detail of the front of the Nazarene Cross. Photography by Juan José Delgado Aguilera.

Figure 24.

Detail in the tray from Museo de Artes e Industrias Populares in Pátzcuaro, maque, eighteenth century. Photography by Y. Kawamura.

Figure 25.

Detail in the front of the Nazarene Cross. Photography by Y. Kawamura.

The golden leaves are drawn by tracing the outlines and veins, letting the black background shown through, except for a few completely gold leaves with the veins painted on top (Figure 26). Five reddish-coloured flowers with clumsy stems, which recall camellias, are arranged symmetrically. The same decorations are repeated along the vertical panel on both sides. The decoration on the horizontal panel (the two arms of the cross) only features leaves with golden veins over a black background, tightly packed into narrow spaces given that there is less space between scenes on these panels. It is evident that the painter limited themselves to decorating these marginal areas with repetitive work copied from a model.

Figure 26.

Detail of the vertical panel of the Nazarene Cross. Photograph by Y. Kawamura.

The motifs of the decoration on the edges (Figure 27) include bunches of grapes and vine leaves, clearly symbolising eucharistic wine and the blood of Christ; hence, they are not mere marginal decorations but are based on a catechetical iconographic programme. Here, black leaves with golden veins and outlines alternate with entirely golden leaves, painted with skillful and careful brushstrokes with a few reddish touches. This is the work of a more knowledgeable painter with greater skill in handling a paint brush than that of the front panels. What is striking is the treatment of the grapes with a light shade close to grey tinged with a silver or pearlescent effect. This pearlescent grey colour can be achieved with silver glazing. Although mother-of-pearl was not used in this work, this detail is strongly reminiscent of mother-of-pearl inlay in Namban lacquer and enconchado.

Figure 27.

Detail of the edge of the Nazarene Cross. Photograph by Ana García Barrios.

Indeed, more similarities to these two art practices can be pointed out. The use of black for the background, probably maque, combined with thick, golden motifs is the style originating from Namban lacquer, assimilated in New Spain, as it has been seen in the enconchado lectern or in the marginal areas of enconchado paintings, such as the frames of the panels of La conquista de México. The fact that these motifs appear in marginal areas is another common feature of enconchado paintings. The vegetal motifs are those that also frequently appear in Namban lacquerware: camellia flowers, bunches of grapes, and vine leaves. The only notable difference is the absence of mother-of-pearl inlay on the cross. However, the pictorial aspect expressed in the grapes leads us to think that the painter’s intention was to imitate the mother-of-pearl inlay of Namban lacquerware or enconchado.

Perhaps the Nazarene Cross was made in a place where the practice of mother-of-pearl inlay did not exist, or in a time when the practice of enconchado was in decline. The widespread practice of maque in Michoacán, Guerrero, Oaxaca, and Chiapas without the use of mother-of-pearl, based on extant works dating from the eighteenth century, would lead us to the production of this cross in those regions at the beginning of the eighteenth century. Michoacán was a place of great maque production in the viceregal period, like Pátzcuaro or Uruapan, without underestimating Chiapa de Corzo, where there is an important tradition of maque and decorated crosses. Despite our investigation, another similar work has not yet been found in Mexico.

5. Conclusions

It is clear that Namban lacquerware arrived in New Spain via the Manila galleon and was highly valued. For this reason, other artistic techniques associated with this artform arose there. The great ability to assimilate and appropriate the foreign culture and create something original was characteristic of the viceregal Americans. On the one hand, the Mexican lacquerware of pre-Hispanic origin received a boost with the arrival of Japanese lacquerware. The proof of this is in the name “maque”—derived from Japanese “makie”—as we know that Sebastián Vizcaino called Japanese lacquerware “maqui” in the beginning of the seventeenth century, as mentioned earlier. On the other hand, the influence of Namban lacquerware in enconchado paintings has also already been noted. However, enconchado furniture has not received a well-earned study thus far. Through the analysis of the works, we consider that this genre was likely developed before enconchado painting. Despite the scarce number of works, the Alba de Tormes lectern, enconchado and very likely maque, is a work datable to the second half of the seventeenth century due to the shape of the still mannerist or early baroque frame of the saint’s portrait. The similarity of their gilding and mother-of-pearl decorative techniques to those of Japanese lacquerware is striking. Hence, the Alba de Tormes lectern could be the first step in the development of Namban lacquer-inspired enconchado, and the Allo tabernacle could be at the next stage of evolution.

If Tomás González de Villaverde, father of enconchado painters Miguel and Juan González, practiced maque in 1689, it is clear that the enconchado painting that was greatly developed at the end of the seventeenth century in Mexico City arose from the maque artistic environment. Although the González brothers stopped using maque and replaced it with oil paint and tempera, undeniable traces of Japanese lacquer can be seen in the marginal areas of the panels painted by the Gonzálezs and their contemporaries.

Another fusion of Japanese Namban-style lacquer with maque can be observed in the unique Nazarene Cross of Puerto de Santa María. The painters who decorated the marginal areas over the black background copied motifs of Namban-lacquer origin and, although they did not use mother-of-pearl, they seem to have imitated its luminous texture with pigments. In this sense, the Puerto de Santa María cross constitutes a very unique example that speaks of another phase in the evolution of maque with influences of Namban lacquer in New Spain.

Despite these conclusions, we are conscious that our study is based on a scarce number of works and that we must look for more pieces of enconchado furniture to confirm them.

Supplementary Materials

The same text in Spanish. The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/heritage7030071/s1, Supplementary Materials S1: Original text in Spanish.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.K. and A.G.B.; analysis and investigation of the enconchados furniture, Y.K.; analysis and investigation of the Nazarene Cross, A.G.B.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.K. and A.G.B.; writing—review and editing, Y.K.; funding acquisition, Y.K. and A.G.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Agencia Estatal de Investigación of the Spanish Government, reference number PGC2018-097694-B-I00 and the Proyecto Puente of the University Rey Juan Carlos (Spain), reference number V1252 (2023).

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

Our thanks go to the research collaborators in Mexico: Sonia Ocaña from Juárez Autonomous University of Tabasco (Universidad Juárez Autónoma de Tabasco) (Mexico) and Rie Arimura from the National Autonomous University of Mexico (Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México). Also, thanks to those who facilitated the study of the works: Alicia Ancho, restorer of the General Directorate of Culture-Prince of Viana Institution (Dirección General de Cultura-Institución Príncipe de Viana) (Pamplona, Spain); José Luis Gutiérrez Robledo from the Complutense University of Madrid (Universidad Complutense de Madrid); Brotherhood of Our Father of Nazarene and Our Lady of Sorrows (Hermandad de Nuestro Padre Nazareno y Nuestra Señora de los Dolores) in El Puerto de Santa María (Cadiz, Spain); Miguel Ángel Caballero, Director of Heritage of the city El Puerto de Santa María; Juan José Delgado, Restoration Manager of the city El Puerto de Santa María; and David Calleja, Councillor of Culture of the city El Puerto de Santa María. Equally, thanks to the researchers who carried out the material analysis of the Nazarene cross of El Puerto: María Luisa Vázquez de Ágredos from the University of Valencia (Universidad de Valencia) (Spain); Mauro Bernabei from the National Research Council (Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche) (Italy); and Rocío Ortiz Calderón and Pilar Ortiz Calderón from the University of Pablo de Olavide (Universidad Pablo de Olavide) (Seville, Spain). The authors also thank Toni Roberts and Clemency Connolly-Linden from University College London (UCL) for their translation into English of the Spanish original version of this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | La luz del nácar. Reflejo de Oriente en México. Exhibition commissioned by Ana Zabia de la Mata, chief curator of Department of Viceregal Americas in the Museo de América, Madrid, Spain. From 24 November 2022 to 25 May 2023. |

| 2 | Original text: “escritorillos, cajas y cajuelas de maderas con barniz y labores curiosas […] sirve para cargazones a la Nueva España”. |

| 3 | Original text: el Japón no tiene retorno de géneros útiles a la Nueva España, porque pinturas, escritorios, biombos y lo que otra vez se trajo, no es mercaduría para ordinarios […] El barniz de los escritorios y bufetes, que es como resina de un árbol, no se sabe otro que le iguale, y así tienen lindezas peregrinas de este género”. |

| 4 | Original text: “algunos hidalgos de México, que le habían encargado de maqui para el regalo de sus casas y la suya”. Relación del viaje a Japón de Sebastián Vizcaíno, 1614. A manuscript copy exists in the Biblioteca Nacional de España, Madrid, Spain, 3046, ff. 83r-117v. |

| 5 | Archivo General de Indias, Filipinas, 20, R. 6, N. 44. “Carta del oidor Juan de la Vega a Ruiz Contreras sobre regalo enviado. Manila”, 16 July 1612. |

| 6 | Original text: “una escribanía dorada del Xapon con guarnición y llabe de plata”, “un escritorio grande dorado con guarniciones y llabe de plata”. |

| 7 | Archivo General de Indias, Filipinas, 339, L. 2, F. 284v. Real Cédula, 1604; Filipinas, 60, N. 12. “Informaciones de oficio”, 1611; Archivo parroquial de Pedroso, “Libro de anibersarios y missas perpetuas y de los bienes que conpeten al beneficio y fábrica desta yglesia de St. Salbador desta villa de Pedroso”, f. 132 v. |

| 8 | For example, the oratory from Tokyo National Museum (Japan) with the figure of Saint Stephen made of New Spanish feather or another from Kyoto National Museum (Japan) with three men as the Holy Trinity—Iconography only used in New Spain, another from Museo Nacional de Artes Decorativas in Madrid (Spain) with Saint Ferdinand painted in New Spanish baroque style. |

| 9 | Museo Franz Mayer, inventory number: 05115. Museo Nacional del Virreinato, inventory number: 54570. |

| 10 | The family relationship between Miguel and Juan has been discussed. Dr Ocaña’s recent study confirms that they were brothers (Ocaña, S. 2023). |

| 11 | Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, MA, USA, inventory number: E76704. |

| 12 | Museo de América, Madrid, Spain, inventory number: 00169. |

| 13 | It is the latest date known accurately up until now. |

| 14 | The early studies were conducted by Suárez Ávila and González Luque, after which Ana García Barrios started an academic study in 2016. |

| 15 | Museo de América, Madrid, Spain, inventory numbers: 00132 and 00171. |

| 16 | Museo de Artes e Industrias Populares de Pátzcuaro, Michoacán, México, inventory number: 10-65-2206. |

References

- Ocaña Ruiz, S. Los marcos ‘enconchados’ y las lacas japonesas namban: Apropiación de un repertorio formal. In Orientes y Occidentes: El Arte y la Mirada del Otro; Curiel, G., Ed.; Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México/IIE: Mexico City, Mexico, 2007; pp. 503–531. ISBN 9703243681. [Google Scholar]

- Ocaña Ruiz, S. Marcos ‘enconchados’: Autonomía y apropiación de formas japonesas en la pintura novohispana. Anales del Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas 2008, 30, 107–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocaña Ruiz, S. Enconchado frames: The Use of Japanese Ornamental Models in New Spanish Painting. In Asia & Spanish America. Trans-Pacific Artistic & Cultural Exchange 1500–1850; Donna, D., Otsuka, R., Eds.; Denver Museum: Denver, CO, USA, 2009; pp. 129–149. ISBN 978-8061-9972-3. [Google Scholar]

- Fróis, L.; Pinto, J.A.A.; Okamoto, Y.; Bernard, H. La Première Ambassade du Japon en Europe, 1582–1592; Sophia University: Tokyo, Japan, 1942; pp. 113–114. [Google Scholar]

- Kawamura, Y. Coleccionismo y colecciones de la laca extremo oriental en España desde la época del arte Namban hasta el siglo XX. Artigrama 2003, 18, 211–230. Available online: https://www.unizar.es/artigrama/pdf/18/2monografico/09.pdf (accessed on 4 October 2020). [CrossRef]

- Kawamura, Y.; Ancho, A.; Balduz, B. Laca Namban. Brillo de Japón en Navarra; Gobierno de Navarra: Pamplona, Spain, 2016; ISBN 978-84-235-3408-1. [Google Scholar]

- Boyer, M. Japanese Export Lacquers from the Seventeenth Century in the National Museum of Denmark; National Museum: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Arakawa, H. Namban Shitsugei; Bijutsushuppansha: Tokyo, Japan, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Haino, A. Kinsei No Makie; Chûôkôronsha: Tokyo, Japan, 1994; ISBN 4-12-101196-1. [Google Scholar]

- Yamazaki, T. Umi o Watatta Nihon no Shikki I (16–17 Seiki) (Nihon no Bijutu 426); Shibundô: Tokyo, Japan, 2001; ISBN 4-7843-3426-2. [Google Scholar]

- Impey, O.; Jörg, C. Japanese Export Lacquer; Hotei Publishing: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2005; ISBN 90-74822-72X. [Google Scholar]

- Hidaka, K. Ikoku No Hyôshô; Brücke: Tokyo, Japan, 2008; ISBN 978-4-434-11660-5. [Google Scholar]

- Nagashima, M. Export Lacquer: Reflexion of the West in Black and Gold Makie. In Japan. Export Laquer: Reflection of the West in Black and Gold Makie; Kyoto National Museum, Ed.; The Yomiuri Shimbun: Osaka, Japan, 2008; pp. 30–48. [Google Scholar]

- Kawamura, Y. Laca japonesa urushi de estilo Namban en España. Vías de su llegada y sus destinos. In Laca Namban. Huella de Japón en España. IV Centenario de la Embajada Keichô; Kawamura, Y., Ed.; Fundación Japón-Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte: Madrid, Spain, 2013; pp. 249–296. ISBN 978-84-8181-540-5. [Google Scholar]

- Morga, A.; Hidalgo Nuchera, P. Sucesos de las Islas Filipinas; Polifemo: Madrid, Spain, 1997; ISBN 978-84-86547-37-0. [Google Scholar]

- Romero de Terreros, M. Relación del Japón (1609), por Rodrigo de Vivero y Velasco. Introducción y notas. An. Mus. Nac. México 1934, 1, 67–111. [Google Scholar]

- Gil, J. Hidalgos y Samurais. España y Japón en los Siglos XVI y XVII; Alianza Editorial: Madrid, Spain, 1991; ISBN 9788420626758. [Google Scholar]

- Tremml, B.; Sola, E. Una Relación de Japón de 1614 Sobre el Viaje de Sebastián Vizcaino. Archivo de la Frontera. 2013. Available online: http://archivodelafrontera.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/Relaci%C3%B3n-del-viaje-de-Sebasti%C3%A1n-Vizca%C3%ADno-1612-1614.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2021).

- Kawamura, Y. Manila, ciudad española y centro de fusión. Un estudio a través del inventario del gobernador de Filipinas Alonso Fajardo de Tenza (1624). E-Spania. Quelle Histoire Globale au XVIe Siècle ?/Fronteras de Ultramar 2018, 30, 1–13. Available online: https://journals.openedition.org/e-spania/27950 (accessed on 14 April 2021). [CrossRef]

- Ballesteros Flores, T.B. Entre el ser y el Parecer. Los Objetos Suntuarios Orientales en el Ajuar Doméstico de Mercaderes del Consulado de la Ciudad de México (1573–1700). Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Mexico City, Mexico, 2007. Available online: https://repositorio.unam.mx/contenidos/entre-el-ser-y-el-parecer-los-objetos-suntuarios-orientales-en-el-ajuar-domestico-de-mercaderes-del-consulado-de-la-ciud-200846?c=pQkkLz&d=false&q=*:*&i=2&v=0&t=search_0&as=0 (accessed on 15 December 2023).

- Ocaña, S.; Arimura, R. Japanese objects in New Spain. Nanban Art and Beyond. Colon. Lat. Am. Rev. 2022, 31, 327–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto Ustio, E. Objetos asiáticos en ajuares novohispanos. El testimonio de los inventarios en las primeras décadas del seiscientos. In El Viaje más Largo. Proyecciones de la Primera Vuelta al Mundo; Martínez de Salinas Alonso, M.L., Martínez, M.C., Porro Gutiérrez, J.M., Eds.; Universidad de Valladolid: Valladolid, Spain, 2022; pp. 147–164. [Google Scholar]

- Kawamura, Y. Obras de laca Namban en España. Síntesis de la globalización bajo la monarquía hispánica. In Arte y Globalización en el Mundo Hispánico de los Siglos XV al XVII; Parada López de Corselas, M., María Palacios Méndez, L.M., Eds.; Universidad de Granada: Granada, Spain, 2020; pp. 531–550. ISBN 978-84-338-6664-6. [Google Scholar]

- Baena Zapatero, A. Apuntes sobre la elaboración de biombos en la Nueva España. Arch. Español Arte 2015, 350, 173–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baena Zapatero, A. Biombos mexicanos e identidad criolla. Rev. Indias 2020, 280, 651–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez Carrillo, S. La Laca Mexicana. Desarrollo de un Oficio Artesanal en el Virreinato de la Nueva España Durante el siglo XVIII; Alianza Editorial: Madrid, Spain, 1990; ISBN 84-206-9044-9. [Google Scholar]

- Medina, I. ¿Maque prehispánico? Una antigua discusión. In Lacas Mexicanas, Ciudad de México; Museo Franz Mayer y Artes de México: México City, Mexico, 2003; pp. 21–30. [Google Scholar]

- Ocaña Ruiz, S. Enconchados: Japão, Nova Espanha, mestiçagens artísticas e os González. In As Américas em Perspectiva: Das Conquistas às Independências; Editora UFJF: Juiz de Fora, Brasil, 2023; pp. 52–69. ISBN 978-65-89512-95-0. Available online: https://www2.ufjf.br/clioedel/wp-content/uploads/sites/75/2023/09/As-Americas-em-perspectiva-das-Conquistas-as-Independencias.pdf (accessed on 5 January 2024).

- Ocaña Ruiz, S. Early Modern Artistic Globalization from Colonial Mexico. The Case of Enconchados. In The Routledge Companion to Global Renaissance Art; Stephen, J., Stephanie Porras, C., Eds.; eBook; Rouledge: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 52–66. ISBN 9781003294986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toussaint, M. La pintura con incrustaciones de concha nácar en Nueva España. An. Inst. Investig. Estéticas 1952, 5, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rivero Lake, R. El arte Namban en el México; Turner: México City, Mexico, 2005; ISBN 9788475066929. [Google Scholar]

- Tovar, G. Documentos sobre ‘enconchados’ y la familia de los González. Cuad. Arte Colon. 1986, 1, 97–103. Available online: https://www.culturaydeporte.gob.es/museodeamerica/dam/jcr:72b3223c-b8ce-4b41-ba1e-0094f2df5467/art-culo-5.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2022).

- Ocaña, S. Nuevas reflexiones sobre las pinturas incrustadas de conchas y el trabajo de Juan y Miguel González. An. Inst. Investig. Estéticas 2013, 35, 125–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawamura, Y. La pintura en los reversos de los enconchados de la conquista de México de la antigua colección de los duques de Moctezuma. In La luz del Nácar. Reflejo de Oriente en México; Zabía de la Mata, A., Ed.; Ministerio de Cultura y Educación: Madrid, Spain, 2022; pp. 83–92. [Google Scholar]

- García Gainza, M.C. Catálogo Monumental de Navarra. II. Merindad de Estella; Institución Príncipe de Viana, Universidad de Navarra, Gobierno Foral de Navarra: Pamplona, Spain, 1982; Volume I, p. 115. [Google Scholar]

- Heredia, M.C.; Orbe Sivatte, M.; Orbe Sivatte, A. Sagrario. In Arte Hispanoamericano en Navarra. Plata, Pintura y Escultura; Gobierno de Navarra: Pamplona, Spain, 1992; p. 236. [Google Scholar]

- García Sáiz, M.C. Sagrario. In Los Siglos de Oro en los Virreinatos de América 1550–1700; Bérchez, J., Alcalá, L.E., Eds.; Sociedad Estatal de para la Conmemoración de los Centenarios de Felipe II y Carlos V: Madrid, Spain, 1999; pp. 382–383. [Google Scholar]

- Dujovne, M. Enchonchados mexicanos en el Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes. In Los Enconchados de la Conquista de México: Colección Museo Nacional de Bellas Arres; Museo Nacional de Bellas Arres-Secretaría de Patrimonio Cultural: Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires, Argentin, 2021; ISBN 978-950-9864-20-7. Available online: https://media.bellasartes.gob.ar/h/Publicaciones/cat_enconchados.pdf (accessed on 23 September 2022).

- Zabía de la Mata, A. La luz del nácar. Reflejo de Oriente en México; Ministerio de Cultura y Deporte: Madrid, Spain, 2022; ISBN 978-84-8181-810-9. [Google Scholar]

- Falck Reyes, M.; Palacio, H. El Japonés que Conquistó Guadalajara. La Historia de Juan de Páez en la Guadalajara del Siglo XVII; Universidad de Guadalajara: Guadalajara, Mexico, 2009; ISBN 9781449267292. [Google Scholar]

- Calvo, T. Japoneses en Guadalajara: ‘Blancos de Honor’ durante el Seiscientos mexicano. In La Nueva Galicia en los Siglo XVI y XVII; Calvo, T., Castañeda, C., Eds.; El Colegio de Jalisco, Centro de Estudios Mexicanos y Centroamericanos: Guadalajara, Mexico, 1989; pp. 159–171. ISBN 9789686142044. [Google Scholar]

- Calvo, T. Guadalajara y su Región en el Siglo XVII: Población y Economía; Centro de Estudios Mexicanos y Centroamericanos, Ayuntamiento de Guadalajara: Guadalajara, Mexico, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno, F. Iconografía de los testigos de los procesos teresianos. A propósito de Adrian Collaert y la escenografía de la capilla Cornaro. Arch. Español Arte 2014, 345, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Cuesta, L.J. ¿Una nueva iconografía? Santa Teresa en el arte novohispano. Hipogrifo 2016, 4.2, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocaña, S. De Asia a la Nueva España vía Europa: Lacas asiáticas y achinadas en el siglo XVIII. An. Inst. Investig. Estéticas 2017, 39, 1131–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Strasse, M.H. (Ed.) Lacquer art from East Asia and Europe. Ex Oriente lux. The Herbig-Haarhaus lac. The Herbig-Haarhaus Lacquer Museum; BASF Colors and Fibers AG: Cologne, Germany, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Kopplin, M. Gérard Dagly: Und die Berliner Hofwerkstatt; Hirmer Verlag GmbH: Munich, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Dujovne, M. Las Pinturas con Incrustaciones de Nácar; UNAM: Ciudad de México, Mexico, 1984; ISBN 978-968-58-0457-8. [Google Scholar]

- Castelló Yturbide, T. La Concha de Nácar en México; Grupo Gutsa: México City, Mexico, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Suárez Diez, L. Conchas y Caracoles. Ese Universo Maravilloso; Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia: México City, Mexico, 2007; ISBN 9789680301300. [Google Scholar]

- Suárez Ávila, L. Habitantes y gente de El Puerto de Santa María. Nótula 2014, 2079, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- González Luque, F. La Hermandad de Jesús Nazareno de El Puerto de Santa María. Estudio Histórico y Artístico; Hermandad de Nuestro Padre Jesús Nazareno y Nuestra Señora de los Dolores de El Puerto de Santa María: El Puerto de Santa María, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- García Barrios, A. Laca asiática y color mexicano en la cruz del Nazareno de El Puerto de Santa María (Cádiz, España). Arqueol. Mex. 2023, 178, 76–81. [Google Scholar]

- García Barrios, A.; Vázquez de Ágredos, M.; Bernabei, M.; Ortíz Calderón, R.; Ortiz Calderón, P.; Delgado Aguilera, J.J. Mexican colors in the cross of the Nazarene in El Puerto de Santa María, Cádiz, Spain. In Drugs and Colors in History; Editorial Tirant lo Blanch Humanidades: Valencia, Spain, in press.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).