Abstract

This article describes the objects in the barniz de Pasto collection at the Museo de América, Madrid. The barniz de Pasto technique will be described, as well as the historical documentary sources that have previously discussed this varnish. The article will also mention the historical reasons why Spain is the European country in which the greatest number of objects decorated with varnish have been found, in both religious and private collections. The main body of the article discusses all the barniz de Pasto objects held in the Museum collection, focuses on the history of their arrival at the Museum, and investigates their possible origin, with the help of ample photographs. The final section examines the Museum’s three most recent acquisitions, completed in the second half of 2022, in detail.

1. Introduction

Barniz de Pasto is a decorative technique used for wooden objects of pre-Hispanic origin, which was most frequently used during the 17th and 18th centuries in the very city that gave the technique its name, San Juan de Pasto, in southwestern Colombia1 The raw material used to make the varnish is a plant resin called mopa-mopa, which is extracted from the Elaeagia Pastoensis tree species, and has been used since pre-Hispanic times. Whilst the term “varnish” has appeared frequently in studies, barniz de Pasto is not exactly the type of varnish known in Europe; rather, it is a plant resin that becomes elastic and malleable once heated. Furthermore, it is placed directly onto the wooden object after being heated, without the aid of any adhesive. This action is performed using only the pressure from one’s hands. Due to the material’s ductility, the varnish adapts to both curved and straight surfaces in a way that permanently protects the wood and decorates the object.

This article presents the barniz de Pasto collection at the Museo de América, along with the history of the collection’s objects. The article also highlights that this collection is not a closed collection, since it continues to expand through the acquisition of new items. The three new objects presented in this article were acquired by the Museum in the last 2 years and are important additions to our collection.

The Museo de América’s barniz de Pasto collection is the most important of all known collections in Europe2. In terms of the quantity, variety, and quality of the objects on display, it could even compete with the Museum collections found in Colombia and Ecuador. Assembled over several centuries, the oldest object became part of the Museo de América’s founding collections in 1888 (and was previously part of the American collection at the National Archaeological Museum). The most recent object was acquired by the Spanish state for the Museum on the art market in 2023.

Spain has had intense historical relations with the Americas, since both were part of what is known as the Hispanic Monarchy. Thus, since Spain’s discovery of the Americas, an abundant array of objects arrived in the Iberian Peninsula from, as they were known at the time, the West Indies, including objects decorated with barniz de Pasto. The viceroys and their administrative, civil, and religious entourage played a key role in the export of objects made in the regions under the Hispanic Monarchy. Amongst their possessions were mementos, notably female accessories, from their lives in the Indies, which they then carried with them to the Peninsula. Whether through acquisitions or diplomatic gifts, the viceroy, the vicereine, their extended household (relatives, servants, and closest courtiers) and the employees who made up the administration of the Monarchy in the Indies, had numerous objects in their possession. Culturally, those objects inform us of the globalisation that took place in the Spanish Empire, owing to the confluence of objects, techniques, themes, and styles originating from Asia, America and Europe.

The return of these viceroys and officials to Spain meant the arrival of an enormous quantity of artworks. These works can still be found in Spain, although the exact quantity is less than the inventories suggest. It is often unknown whether their origin is indeed the Americas. Some studies attributed them to the Eastern Islamic World [1].

These objects remained in the possession of specific individuals or in religious institutions. When they surfaced on the art market, the Spanish Ministry of Culture, becoming increasingly aware of the objects’ importance, acquired them and assigned them to the Museo de América’s collection.

It is interesting to note that, although there are objects with barniz de Pasto in Spanish churches and other religious institutions, as well as on the art market, there is no record of barniz de Pasto objects in the inventories of the aristocracy. This is especially true in the case of the Novohispanic aristocracy, a subject that has been well researched [2]. This topic is being researched and carries great potential, particularly for the Viceroyalty of Peru, where published inventories mainly refer to painting collections, ivory carvings, feather art, furniture, lacquer, silks, etc. However, the inventories that clearly tell us about barniz de Pasto objects still need to be studied in detail. This subject thus requires further research, and the comparison of inventories and notarial archives could yield many surprising results regarding the varnish and how it was being collected by American elites.

There are objects that speak for themselves and, due to their heraldic or figurative iconography, reveal that they were owned by the aristocracy. One example is the case of the desk with a heraldic coat of arms in the decorative arts collection of the Hispanic Society Museum Library [3]. However other simpler objects decorated with barniz de Pasto indicate that the use of varnish was rooted in Indigenous communities and was used on objects intended for everyday life. Within the Museo de América’s own collection, therefore, there is a distinction between the objects decorated with varnish that were made in small villages and used by Indigenous communities, and luxury objects made in the city. This city would either have been San Juan de Pasto or Quito, the capital of the Real Audiencia (the administrative unit of the Spanish Empire). This topic has yet to be researched in depth, since many objects that were decorated with varnish and used in Indigenous communities are unheard of. In-depth research into the collection at the Museo de América has been carried out, but there is room for further research, as there may be many objects with barniz de Pasto in other European and American collections3.

Other sources of information about barniz de Pasto are travellers’ accounts and chronicles, which mention the workshops in the city that gave the varnish its name. This displays the continuity of the work from the pre-Hispanic world, the iconographic and technical change brought about when the Spanish arrived, and how the work continues to the present day. An extensive list of references from travellers and chronicles can be found in the work of Granda Paz [4], which lists the known documentary references from the earliest travellers up to the end of the 19th century.

The first mention of varnish being used in southern lands is by Fray Pedro Simón in Noticias de las conquistas en Tierra Firme en las Indias Occidentales (1627) [5]. Discussing the varnish of Timaná, he affirms that these works are also made in Mocoa, Quito and other parts of Peru. By mentioning Quito, it is likely that Fray Pedro Simón knew that there was a barniz de Pasto workshop in the capital of the Real Audiencia. However, this needs to be studied further.

2. Analysis of the Decorative Influences in the 17th and 18th Century Works

It is not possible to outline one single influence on the iconography and technique used by the varnish craftspeople. As in other manifestations of Ibero-American art, there was an underlying Indigenous layer in these works, which initially had a Spanish influence that was then transferred between people who commissioned new objects of Western taste.

These clients provided books, engravings, ceramics, sculptures, and other items that were used to copy, circulate, and display Western technical and iconographic repertoires.

The influence of Spanish sculptors who worked with polychrome, estofado wood is particularly important4. This technical influence has been highlighted as the reason for incorporating silver leaf into the barniz de Pasto. It is called barniz brillante for this reason, and examples of this are found in the collections at the Museo de América. Examples will be shown later in this article [6].

Above all, the Asian influence was fundamental in these objects, which arrived in the Americas through the commercial and cultural route of the Manilla galleons. These ships carried textiles, Chinese silks and porcelain, Japanese objects of nanban art, ivories, and paintings [1]. However, also being transported were ideas, styles and decorative motifs to honour the people who created them. The arrival and settlement of Asian artists into the viceregal cities of Hispanic America is well known [7] in both New Spain and in Peru, particularly Lima, as well as other great commercial and artistic emporiums such as Quito and San Juan de Pasto.

3. The Barniz de Pasto Collection at the Museo de América, Madrid

3.1. The Earliest Objects from the Museum Collections

The first objects decorated with barniz de Pasto were added to the Museum’s collection and catalogued as items that came from the Americas, but it was not known that they came specifically from San Juan de Pasto. Once new works with this varnish were acquired and there was knowledge of objects from other museums and collections, it then became possible to compare some objects with others in order to catalogue the set of varnished works at the Museo de América more precisely.

The two oldest pieces in the collection come from the founding collection of the Museo de América, which in turn comes from Ethnography section IV of the National Archaeological Museum, where the objects arrived at the end of the 19th century5.

On one hand, there is a twice-indented concave bowl with a flat brim and lobed profile (Figure 1, inv. no. 12242), which measures 43 cm in length and 24.5 cm in width. It is decorated with flowers, birds, and fantastic animals, and was first mistakenly catalogued as originating from Mexico. It is now catalogued and displayed with the geographical location of ‘Real Audiencia de Quito. Viceroyalty of Peru. Present-day Colombia.’ The bowl was dated back to the 19th century, although a comparative analysis with other similar barniz de Pasto items, as well as ceramic pieces from Talavera de la Reina (Figure 2a,b) and Asian porcelain of similar format and iconography, allowed for its origin to be recorded as the 17th century.

Figure 1.

Twice-indented bowl with a flat brim and lobed profile.

Figure 2.

(a,b) Spanish ceramic items with a similar shape to the bowl with barniz de Pasto.

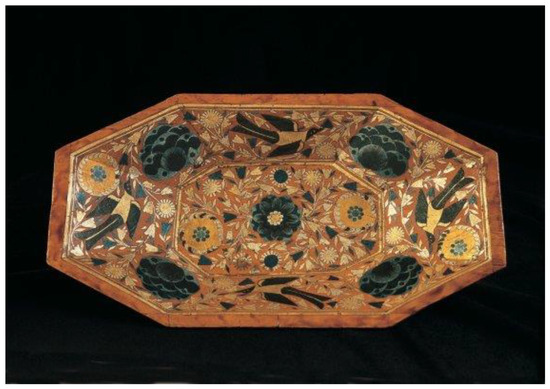

Next, an octagonal-shaped platter (Figure 3, inv. No. 12243), 42 cm in length and 23 cm in width, made from cedar wood6, whose surface is completely covered with, firstly, a layer of colourless varnish. A rich layer of polychrome varnish was then added onto the main surface, and there are sophisticated plant and zoomorphic motifsflower bouquets and birds - which follow an ordered pattern on both the base and the brim. By comparing the decoration with other, similar works created in San Juan de Pasto, this item was dated to the 18th century.

Figure 3.

Octagonal-shaped platter.

The bowl decorated with barniz de Pasto in a grid pattern (Figure 4a,b, inv. No. 12304) also comes from the Museo de América’s founding collection, and, thus, from the former collection of the Ethnography Section of the National Archaeological Museum. It has a diameter of 15 cm and was originally catalogued as originating from Peru, although there were no further details in its documentation. In fact, that it is an item with barniz de Pasto has only been verified in recent years, due to it being studied meticulously and in detail. As for the item’s decoration, the exterior exhibits ornamentation of a circle at the centre and orange-coloured flowers, as well as other plant elements and blue and golden birds along the surface7. The interior shows the varnish in its pure colour, whilst the background was shaped by hand in such a way that it shows a grid of small squares, which has been, until now, an unknown ornamental motif in the field of barniz de Pasto. This could suggest the participation of a different kind of workshop for a new technique.

Figure 4.

(a,b) Bowl decorated with varnish in a grid pattern.

Likewise, a platter decorated with varnish (Figure 5, inv. no. 06927), which came from the National Archaeological Museum in Madrid and was donated by José Ignacio Miró in 18728, was sent to the Museo de América. Although, at the time, the curator of the Ethnography collection at the National Archaeological Museum, Ángel Gorostizaga, recorded the item as Mexican, he highlighted the link it had with the barniz de Pasto trays from the same collection: “painted and gilded wooden platter analogous to numbers 2336 and 2337, and another item with inventory number 06927 had been catalogued as originating from Uruapan” [8].

Figure 5.

Platter decorated with varnish, top and bottom view.

The platter has a patterned background and is decorated with varnish. It displays plant motifs distributed in ten radial lobes around a central medallion (the umbo), which form poly-lobed borders framed in a circle. There are also other ornamental elements of a phytomorphic nature.

Of all the objects in the Museum decorated with barniz de Pasto, this is the only one in a poor state of conservation, which prevents the varnish from being clearly visible. Through the surviving documentation, it is known that the tray was repainted before arriving at the Museum. The repainting, as well as the item’s layer of dirt, reduces the original brightness and colouring, namely, the gold, green, red, and blue colours of the barniz de Pasto. The back of the platter shows degraded varnish in a poor state of preservation, which has turned the varnish into a pasty but appealing lacquer, reminiscent of a tortoise shell. It was originally thought that this section was made using a new technique, but by observing other objects that are in a better state of conservation, the verdict is that this “technique” is actually an indication of the degraded varnish. There is an addition of gold leaf to the plant motifs in the upper border.

The item’s catalogue entry has recently been revised, and items have been attributed to the Pasto workshops [9].

3.2. 19th Century Items Decorated with Barniz de Pasto

It is important to mention the large donation made by the writer José María Gutiérrez de Alba in 1872 to enrich the collection of the Ethnography Section of the National Archaeological Museum at that time. Gutiérrez de Alba was sent on a diplomatic mission to Colombia by the Spanish government in 1870, with the objective of re-establishing relations between the two countries [10]9. Spending several years in Bogotá and travelling around the whole of Colombia, he accumulated a series of historical and artistic objects10, in accordance with the spirit of the post-Enlightenment, which was still in fashion in the 19th century. In this way, and according to documentation in the archives of the Museo de América, he sent four boxes to Madrid with stuffed animals, minerals, reptiles, insects, and items, which he called “curious Indigenous items”11. Some objects were considered more fitting for the collections at the National Museum of Natural Sciences, but others were sent to the National Archaeological Museum. This is recorded in Section 6 of the catalogue kept in the Museum of the Americas12.

The catalogue is of great historical and biographical interest, as it offer an account of the places Gutiérrez de Alba visited, his interests, and his modus operandi as a collector13. The writer was interested in objects decorated with barniz de Pasto due to his contacts with members of the Chorographic Commission14. Their illustrations and studies spoke of these types of items. Furthermore, Gutiérrez de Alba collected samples of the typical resins and lacquers of Colombia, although he did not explicitly mention those extracted from the mopa-mopa tree15.

Among the objects with barniz de Pasto that Gutiérrez de Alba donated are five gourds with barniz de Pasto from Timaná (Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9 and Figure 10, with inv. nos. 12108, 06965, 12130, 12139 and 12140). They belong to a type of vessel typical of the natives from the Pasto region. They were made using the hard shell of gourds, either carved by hand or with turning tools. In other similar objects, made from gourds but not decorated with barniz de Pasto, it has been noted that the manufacture was reserved for women. The procedure, which has a long tradition, entailed burying the gourd in order to accelerate the pulp’s decomposition and facilitate its extraction with the use of scrapers. The gourd shell would then be hardened by being repeatedly heated. Thus, in these small objects with simple decorations, the survival and continuity of pre-Hispanic techniques can be seen, as well as ornamental repertoires through the viceregal period, right up to the 19th century.

Figure 6.

Inv. no 12108. Gourds of Timaná, top and bottom view.

Figure 7.

Inv. no. 06965. Gourds of Timaná, top and bottom view.

Figure 8.

Inv. no. 12130. Gourds of Timaná, top and bottom view.

Figure 9.

Inv. no. 12139. Gourds of Timaná, top and bottom view.

Figure 10.

(Inv. no. 12140). Gourds of Timaná, top and bottom view.

Existing documentation does not cite any trip that Gutiérrez de Alba made to San Juan de Pasto (around 300 km from Timaná), but he was able to collect the objects in Timaná through exchanges between various local communities16. These objects, of varying dimensions (the diameter ranges from 6 cm in diameter and a 3.5 cm height of the gourd with inv. no. 12139, to 19 cm in diameter of the gourd with inv. no. 06965), stand out for their use of a colourless or polychrome varnish. In this case, they form very simple decorations around the rims, including phytomorphic, floral, and teardrop-shaped motifs. Gold and silver are also used to enhance the motifs incised into the outer layer.

On the other hand, unlike other items decorated with barniz de Pasto in the collection at the Museo de América (such as the platters, chests, or desks, which serve primarily as containers but are also decorative status symbols), these objects are of a domestic nature, as in the case of the gourds collected by Gutiérrez de Alba. However, their ritual and ceremonial function for food and drink cannot be ruled out.

3.3. Objects Acquired in the 20th Century

On the other hand, the “Mexican” chest with barniz de Pasto was purchased by the Marquis of Lozoya (Figure 11, inv. no. 06675) and entered the collection of the Museo de América in 1967. It was acquired in Segovia from the antiquities dealer Félix Llorente, through the mediation of the aforementioned Juan de Contreras y López de Ayala, 9th Marquis of Lozoya. He was an esteemed art historian and critic who held the post of General Fine Arts Director in the mid-20th century. Given its dimensions (35 × 59 × 34.5 cm), it could be considered more of a small case, although its size is still considerable. This is a very important detail, as there are no known pieces of this kind which are made with barniz de Pasto and have similar dimensions17. It has, therefore, been thought that perhaps the piece did not originally have this size or shape, that additions such as legs and the upper rim were made, or that it was assembled at a later, undetermined date18. Although it was acquired for the Museo de América as a Mexican piece, it is in fact a barniz de Pasto piece. It is considered the most important item of barniz de Pasto in both the Museum and other worldwide collections due to its size, the beauty of its decoration and its exceptional state of preservation. Whilst the circumstances in which the item was acquired do not allow for access to the documentation that provides historical details, a comparative analysis with similar pieces has allowed for it to be dated to the 17th century. It has also been linked to items produced in Quito—which is not surprising, since Pasto was also under the administration of the Real Audiencia—but they were made in different workshops [11]. Unlike its “sister” piece, which was commissioned by the stately Quirós family in the second half of the 17th century and is now kept in the Hispanic Society Museum Library in New York [3]19, this chest does not have heraldic or epigraphic elements that refer to the client or owner of the object, who must have been a prominent individual, given the indisputable material and visual richness of the chest.

Figure 11.

“Mexican” Pasto chest bought by the Marquess of Lozoya.

The chest, as a container for goods, is a key element of American furniture, as it speaks of the travelers who transported their belongings from the viceroyalties to Spain. The Museum’s collection includes many pieces of storage furniture: suitcases, cases, trunks, chests, etc. Often, this furniture also served as decoration, which, in the case of this piece (of which the keys have been preserved), explains and justifies its visual beauty from the point of view of representing power and prestige.

This piece shows, through the decoration of the interior with varnished areas and others left in reserve, how the craftsman would sometimes make use of varnish residues from previous works, or exercise on “test” pieces. In addition to the polychrome varnish, there are points of transparent varnish in which the artisan’s fingerprints can be seen20.

3.4. The Most Recent Barniz de Pasto Acquisitions

The collection of the Museo de América in Madrid is not only of interest because of the quantity, variety, and quality of its more or less ancient barniz de Pasto holdings, thus making it a benchmark institution at the European and international levels, but also because it is an ever-expanding collection. Since the year 2000, it has acquired new barniz de Pasto pieces, which will be shown below.

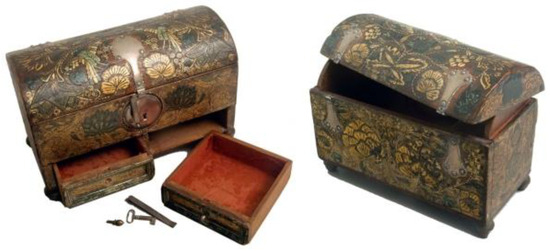

In 2007, a “Turkish” barniz de Pasto chest (Figure 12, inv. no. 2007/04/01) was acquired from the antiques dealer Susana Montiel-Colmenares; it had been found in 1961 on the London art market in the shop Gabor Cossa Antiques, where it had been catalogued as having been made in Turkey. This is a small wooden cabinet with a barrel-vaulted lid; it rests on spherical feet; it has a drawer on the left side and two more at the bottom; the inside of the lid and the compartments are lined with very worn red velvet; it has the original lock made of silver. As for its decoration, it has the characteristics of belonging to the barniz de Pasto brilliante variant, due to the insertion of silver leaf between the sheets of varnish to produce a very characteristic shiny and iridescent effect. Also, due to the ornamental repertoire based on flowers and birds, the piece was dated to the second half of the 17th century.

Figure 12.

“Turkish” Barniz de Pasto chest, with open drawers and lid.

In recent years, several pieces decorated with barniz de Pasto have appeared on the national and international art market, although the Museum, through the Ministry of Culture and Sport to which it is organically attached, has not always considered it interesting or viable to request their acquisition21. However, despite the departure of pieces of particular relevance from Spain (such as the aforementioned writing desk now in the Hispanic Society), others have been acquired to enrich the Spanish Historical Heritage as a whole at the level of the collections of the Museo de América, as is the case of the barniz de Pasto portable writing desk (Figure 13, inv. no. 2015/08/01), acquired in 201522. It has a rectangular shape, and has a lid and a fallfront that, when open, reveals the interior, with six small drawers of different sizes. The exterior must have lost some of the barniz de Pasto decoration, and was covered by a reddish painted stucco, with engraved and gilded flowers in the corners, but around the keyhole the original decoration can still be seen. The current keyhole, which is larger than the one that must have been originally fitted, has covered and thus protected part of the varnish. The upper lid is richly ornamented with plant motifs and stylised animals (two birds and two wild boars), arranged symmetrically, whose black plumage or fur is enhanced with gilt incisions to mark the eyes or anatomical shapes. The lid is also framed by a wide border with a motif consisting of four gilt squares forming a rhombus and joined together with circles23. Finally, and in light of the technical analysis, if the immediately preceding piece was linked to the barniz de Pasto brilliante, this desk could be the forerunner of another sub-category, the ‘written’ or ‘epigraphic’ barniz de Pasto, as it is, to date, the only piece known to place sheets of written paper between the layers of varnish, as can be seen in the centre of the front cover, where it reads: “paulo quinto”. It is not known whether it refers explicitly to a specific person, who, by the name, could be Pope Paul V (pp. 1605–1621), which could lead to some additional clues as to the chronology of this object.

Figure 13.

Barniz de Pasto travelling desk, with details of the interior.

As mentioned above, one of the aims of this article is to present the Museum’s latest acquisitions of Barniz de Pasto objects as part of the desire to enhance the institution’s museological and scientific collections of art and decorative arts from the viceregal period. Firstly, in June 2022, the State acquired, at the auction held on the 30th March of the same year at the Alcalá auction house (C/Núñez de Balboa 9, 28001 Madrid), for 1200 EUR and destined for this Museum, a small wooden chest with barniz de Pasto (Figure 14a,b, inv. no. 2022/07/01), made of cedar wood, measuring 21 × 20.5 × 36.5 cm. The box has a mixtilinear profile, based on curves and counter-curves with flat-edged corners, no feet, and a flat lid at the top that opens and is held in place by two metal hinges; the metal lock does not seem to correspond to the one it must have originally had; the interior is divided into two parts of different sizes. The smaller part, located on the right-hand side and divided into two shelves, contains a secret drawer underneath.

Figure 14.

(a,b) Small chest, in open and closed positions.

The varnish decoration extends to both the outside and inside of the piece, except for the abovementioned secret drawer. The ornamentation follows an orderly, symmetrical composition, with bands and borders formed by plant and zoomorphic abstractions in gold, greenish and white tones against a reddish background, framing the scenes of what appear to be snowy winter landscapes of clear Asian influence. These are placed in the centre of each face of the box and in the centre of the upper lid. On the inside of the lid, on an equally reddish background, there is only one heraldic or vexillological motif.

Although it is not in an excellent state of conservation, the piece is of considerable interest when it comes to adding to the Museum’s collection of barniz de Pasto, contextualising the other pieces, and broadening the chronological horizons of the collection beyond the strictly viceregal period, thus showing the deep roots of this technique, which explains its continuity up to the present day. This is due to the problematic dating of the piece, which was originally placed in the 19th century, in the now independent Republic of the United States of Colombia, which replaced the former Viceroyalty of New Granada. However, vexillology allows for us to analyses the motif on the inside of the cover, which corresponds to the Colombian national coat of arms instituted in 1886 for official flags and in 1924 for military institutions. The coat of arms reads as follows: at the top, a condor with outstretched wings looking to the right, bearing in its beak a laurel wreath and a band with the motto “Liberty and Order”; on the sides, four flags or trophies; on the upper band of the coat of arms, two cornucopias flanking a pomegranate; on the middle band, a Phrygian cap on a spearhead; and on the lower band, the isthmus of Panama with a ship on each ocean.

In terms of its function and cultural context, this chest must have served as a container for documents or other valuable personal items, as suggested by the presence of the secret compartment. In this sense, this type of object had been produced, commissioned, and collected regularly and intensively throughout the Modern Age, both in the Iberian Peninsula and in Latin America. On the other hand, the presence of the Colombian national coat of arms on the inside of the lid suggests that the commissioner or owner of this chest was an official of the new Republic that emerged from the independence from the Hispanic Monarchy, or simply a private citizen. The name Luis Ortega Pasto would refer to its owner, who wanted to underline his patriotism at a historical moment, marked by the construction of the Colombian national identity.

The name Luis Ortega may also relate to the master who worked on the chest, although we think that if this were the signature of the maker, it would not occupy such a central place on the chest, and we have not found any other pieces that refer to Luis Ortega’s workshop. This issue is, therefore, open for further research. Pasto refers to its place of production.

In June 2022, a flat-top chest with barniz de Pasto (Figure 15a,b, inv. No. 2022/07/02), acquired by the State for 1200 EUR at the auction held in the Alcalá Room on the 30th March of that year, also entered the holdings of the Museo de América. Initially, it was listed in the room’s catalogue as a 19th-century Mexican lacquer production.

Figure 15.

(a,b) Chest Inv. No. 2022/07/02, closed and open.

Its dimensions are 21 × 20.5 × 36.5 cm. The box is rectangular with a straight profile. It has a hinged top lid with two hinges located on the upper edge of the back of the box, and its interior is divided into two compartments—a larger compartment on the left, and a smaller one on the right—which, in turn, are organised into two superimposed shelves, which can also be accessed by removing the right side of the box, revealing a drawer or secret drawer that can be extracted with the help of a metal ring handle. The box opens and closes with a key. The flat, mixtilinear-profile, metal keyhole is located at the top of the front face of the box, below which is a smaller, star-shaped or compass-rose-shaped metal applique.

The decoration, based on the barniz de Pasto technique, consists of perimeter bands in the form of strips with segmented edges in dark and reddish tones, which frame the central spaces decorated with plant and zoomorphic motifs of flowers and birds. The entire surface of the piece is decorated with reddish, ochre and orange tones, which give it a mottled or veined appearance, reminiscent of the finish of tortoiseshell. We believe that this tortoiseshell appearance is due to the poor state of conservation of the varnish, which gives rise to these small gum mounds. We do not believe it to be a new technique.

Due to its formal and stylistic analogies with other pieces, it has been established that, far from being a 19th-century Novo-Hispanic lacquered chest, it is an object decorated with barniz de Pasto, from the Viceroyalty of Peru, which can be dated to the 18th century.

Although its quality and state of preservation are average, this piece is of great interest to the collections of the Museo de América, as it supports the aforementioned effort to assemble an important collection of objects decorated with barniz de Pasto. Here, as in the case of the previous chest, it can be attributed to its use as a container for various high-value materials, as once again, there are several compartments, one of which is hidden in the structure of the box. With regards to the workmanship and decoration of the piece, it can be assumed that the recipient was a person of a certain socio-economic standing.

Finally, shortly after the two previous pieces entered the permanent collection of the Museo de América in Madrid, this same institution received a proposal to acquire a barniz de Pasto jícara (Figure 16a–d), a vessel made with a gourd.

Figure 16.

(a–d) inv. no. 2023/05/01 Jícara, front view, detail of the anterior, side view, detail of the foot.

The jícara is 10 cm in height and 7 cm in diameter. The vessel has a regular oval shape, two lateral handles in carved silver with a ‘3’ profile, and is decorated with two opposing birds and hybrid female figures (possibly mermaids) resting on two masks of the same metal in the shape of baskets of fruit. The upper rim is also in silver and in the shape of a band decorated with incised plant motifs and with a serrated lower edge. It has a very short stem that rests on a slightly conical foot, with a silver-mounted base decorated with a serrated profile. The piece is unmarked as far as its silverware application is concerned.

The decoration of the outer wooden surface of the vessel is made using the barniz de Pasto technique, following a symmetrical pattern. There is a large band framed by golden lines, in which the motifs of plant abstractions envelop birds with black plumage, large tails, small wings spread-out in-flight position, and a head in profile with a single large, almond-shaped eye and a long beak. The state of conservation of the varnish is good. There are cracks in the wood at the front of the foot of the piece, which do not affect its stability.

From its formal, technical, and iconographic study, it can be deduced that this wooden jícara with barniz de Pasto and silver applique belongs to an unknown maker or workshop from the viceregal period, but that it can be attributed to the region of the city of Pasto in the 18th century.

Barniz de Pasto pieces with silver mounts are very rare. Although they exist in Colombia, before this piece, there were no documented references in the Spanish art market. According to information provided by the previous owner, they bought the jícara from another dealer on the art market in Portugal, although this statement could not be verified by documentary evidence.

This jícara belongs to a typology of vessels of pre-Hispanic origin intended for consuming chocolate, which Europeans would later incorporate into their cultural, social, and culinary heritage. Thus, from the small vessels originally made of wood, gourd shell or hollowed-out coconut, which were decorated with reliefs, painting or pyrography, the colonial period saw the production of jícaras in these or other, similar materials, without forgetting ceramics and porcelain. We know of no other jícaras that incorporated decorations based on barniz de Pasto with mounts in precious metals such as silver or gold. In these cases, as in the present one, the richness of the materials and the techniques used suggest that the client was a wealthy person of high social and cultural standing.

4. Conclusions

In this article, we presented the barniz de Pasto collection of the Museo de América, placing special emphasis on the history of the pieces that comprise it and highlighting the fact that this collection does not form a closed collection, as it continues to grow through the acquisition of new pieces. Currently, it is the collection with the most barniz de Pasto objects of all European museums.

The Museo de América’s collection includes, on the one hand, sumptuary objects that were most probably made in urban workshops in San Juan de Pasto and Quito, the capital of the Real Audiencia, and objects decorated with varnish that were made in small villages and used by Indigenous communities.

Further research on archival documents that could provide new data on barniz de Pasto objects is desirable.

Finally, we would like to state the Museo de América’s desire to continue increasing its collection of barniz de Pasto objects and we hope that, in future articles, we will be able to continue announcing new acquisitions.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/heritage7020033/s1.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Sonali Arora and Rory Hancock from University College London (UCL) for their translation into English of the Spanish original version of this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | The Colombian city of San Juan de Pasto is the capital of the department of Nariño. It was founded in 1537 and is located at the in the middle of the Andes mountain range in southern Colombia, on the border with Ecuador. San Juan de Pasto belonged to the Real Audiencia of Quito in the province and government of Popayán. |

| 2 | With respect to European museums with Barniz de Pasto collections it should be noted that the Victoria and Albert Museum of London is also building a collection of Barniz de Pasto objects, currently there are already ten pieces in its collection. |

| 3 | At the Fine Arts Museum in Lons-le-Saunier, France, there is a painted gourd (gourd-shellbowl with a golden frieze ornament) with the inventory number 5061. It was donated by Etienne Goudot, a traveller in Colombia in the 19th century. Although it is catalogued as painted, the frieze is decorated with barniz de Pasto. |

| 4 | Estofado/a is a decorative technique that entails applying a thin golden layer onto the object before it is painted, in order to obtain shining and golden iridescence, intermingled with the colour of the paint. This is obtained after scrubbing the parts which should stand out. |

| 5 | The Museo de América was created by Decree on the 19 April 1941, and its initial collection consisted of collections of American archaeology, art and ethnography, which, up until then, had belonged to the National Archaeological Museum. |

| 6 | From a purely visual analysis, the wood is believed to be cedar, but no analysis of the wood has been carried out. |

| 7 | So far the analysis of gold-coloured areas on barniz de Pasto objects has not revealed the presence of underlying gold leaf. Information was provided by Dely Illán at the Museo de América’s barniz de Pasto workshop in June 2019. |

| 8 | Sold to the Spanish government and placed in the National Archaeological Museum, as recorded in the files from the same Exp. N 58, Box C 20, dated as the 27 June 1872. In 1872 the first purchase of a large collection for the recently created National Archaeological Museum took place, that of José Ignacio Miró, comprising of over 250 items. Of these, only four were from the Americas, but among them was a small or Cortesian fragment of the most important book in the Museum’s collection, el Códice Tro-Cortesiano (or Códice de Madrid). It was one of the only four Mayan codices preserved in the world and was by far the largest one (the other fragment, the large one or the Troano, was also acquired in 1888). The other three were monumental Mayan stone heads that decorated buildings in Uxmal, Mexico. |

| 9 | “Since the first years of my youth, reading various works related to the Spanish discovery and conquest of the Americas enlightened me to form my own judgement on the Spanish colonisation of those countries, the causes of emancipation and its grave repercussions for my country. I had a constant aspiration that my country should make the greatest efforts to regain its lost influence, strengthening relations with those towns, its siblings, as far as familial ties can and should be strengthened.” Diario de impresiones de mi viaje a la América del Sur (Campos Díaz, 2015: 287). |

| 10 | All his memories were written in diaries, which he himself illustrated and in which he summarised his impressions of the country. The complete manuscript of thirteen volumes, which was never published during the author’s lifetime, was sold by his descendants to the Colombian government and is now in the Ángel Arango Public Library in Bogotá. |

| 11 | Museo de América: Catalogue of the objects sent from Bogotá to the Minister of State in Madrid by José María Gutiérrez de Alba on the 6 April 1872. This 28-page catalogue, signed by the writer, is divided into several sections, grouping together the objects sent. Museum of the Americas File MAN 57 1872 29. |

| 12 | “Section 6: Curious Indigenous items and manufactured objects, which are the speciality of some districts”. |

| 13 | Referring to, among other places, Alto Magdalena, Chiquinquirá, Timaná, Boyaca, Tuluni, Velez, Villa de Leiva, the plains of San Martín, Ubague, and the state of Cundinamarca. |

| 14 | The Chorographic Commission was a cartographic project promoted by the Republic of New Granada that made it possible to compose the map of Colombia through a series of partial surveys. This was carried out between 1850 and 1859. |

| 15 | The resins named are: gague resin, incense resin, Gutta gum rosin resin, caraña gum rosin resin, peraman resin, hobo gum rosin resin, anime, urrucay, copal gum rosin resin. |

| 16 | The handwritten diary by José María Gutiérrez de Alba is kept in the Ángel Arango library in Bogotá. Impresiones de un viaje a América, Volume VIII (from 19 November 1872 to 17 January 1873, expedition to the south). It is not explicitly stated that he bought the objects. |

| 17 | Special thanks go to Guillermo Eduardo Maldonado for his help in researching the collection of objects with barniz de Pasto in the Museum of the City, Quito. |

| 18 | Antiques dealers joined together two smaller chests to form a larger one. |

| 19 | The portable desk was commissioned by Cristóbal Bernardo de Quirós (1618–1684), bishop of Popayán, as a gift for his brother Gabriel, secretary to Charles II, Marquis of Monreal. This exceptional piece was in Spain until the year 2000, when it was sold and subsequently bought by the Hispanic Society Museum Library, where it is currently found. |

| 20 | It is interesting to note how objects made with barniz de Pasto have preserved the fingerprint of the person who made them. In the absence of signatures or names both on the object itself and in the many accounts of travelers who speak admiringly of the varnish workshops, if it were possible to analyse the fingerprint left on each object, we could group those that share the same fingerprint and therefore know they come from the same workshop, although we may never know the name of the artist. |

| 21 | In the Museum we have a photographic archive with information on various pieces of barniz de Pasto that have come onto the art market in Spain in recent years. |

| 22 | I am grateful to Beatriz du Breuil, owner of Subastas La Suite, for the information that this piece was owned by the Portuguese collector Rui Assis Ferreira, who bought the piece in Paris in the 1950s from a diplomat who had worked for several years in Bogotá. |

| 23 | Yayoi Kawamura points out that this motif is characteristic of Japanese urushi lacquer. |

Primary sources

ARCHIVO DEL MUSEO DE AMÉRICA: Expediente Museo Arqueológico Nacional (MAN), 57, 1872, 29.

The original text in Spanish can be found in Supplementary Materials.

References

- Zabía de la Mata, A. La luz del nácar. Reflejos de Oriente en México, Catálogo de la Exposición Museo de América de Madrid (November 2022–May 2023); Ministerio de Cultura y Deporte: Madrid, Spain, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Curiel, G. Tránsito de obras suntuarias a la Nueva España. Reflexiones sobre el comercio transmarítimo. In España y Nueva España: Sus Acciones Transmaritimas. Memorias del I Simposio Internacional Celebrado en la Ciudad de México del 23 al 26 de Octubre de 1990; Iberoamericana: Ciudad de México, México, 1991; pp. 141–170. [Google Scholar]

- Creixell Cabeza, R.M. Entre el viejo y el nuevo mundo: El escritorio de barniz de Pasto de la colección de artes decorativas de The Hispanic Society of America. Res Mobilis 2014, 3, 119–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Granda Paz, O. Aproximaciones al barniz de Pasto; Editorial Travesías: Barranquilla, Colombia, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Simón, P. Primera parte de las Noticias historiales de las conquistas de tierra firme en las Indias Occidentales; Casa de Domingo de la iglesia: Cuenca, Spain, 1627. [Google Scholar]

- López Pérez, M.P. El Barniz de Pasto. Encuentro entre tradiciones locales y foráneas que han dado la identidad a la región andina del sur de Colombia. In Patrimonio Cultural e Identidad; Carro, P.C., Ed.; Ministerio de Cultura: Madrid, Spain, 2007; pp. 225–234. [Google Scholar]

- Ocaña Ruiz, S. Marcos enconchados: Autonomía y apropiación de formas japonesas. An. Del Inst. De Investig. Estéticas 2008, 30, 107–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabía de la Mata, A. Ángel de Gorostizaga, el olvidado descubridor del Códice Martínez Compañón. In 150 años de una Profesión: De Anticuarios a Conservadores; Ministerio de Cultura: Madrid, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zabía de la Mata, A. El arte del barniz de Pasto en la colección del Museo de América de Madrid. Anales del Museo de América 28; Ministerio de Cultura: Madrid, Spain, 2020; pp. 81–98. [Google Scholar]

- Campos Diaz, J.M. José María Gutiérrez de Alba (1822–1897): Biografía de un Escritor Viajero. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Sevilla, Sevilla, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- López Pérez, M.P. Quito, entre lo prehispánico y lo colonial. El arte del barniz de Pasto. In Arte quiteño. Más allá de Quito; Crespo, A.O., Bustillos, A.P., Eds.; FONSAL: Quito, Ecuador, 2010; pp. 45–63. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).