Abstract

This article investigates the audibility and intelligibility of preaching in a loud voice inside the Cathedral Notre-Dame de Paris during the Middle Ages, after the construction of the Gothic cathedral, until the late 19th century. Through this time period, the locations where oration took place changed along with religious practices inside the cathedral. Here, we combine a historical approach with room acoustic modelling to evaluate the locations inside the cathedral where one would hear sermons well. In a reverberant cathedral such as Notre-Dame, speech would be most intelligible in areas near the orator. Until the introduction of electronically amplified public address systems, speech would not be intelligible throughout the entire cathedral.

1. Introduction

This article investigates the audibility and intelligibility of spoken voice inside the Cathedral Notre-Dame de Paris. The scope of the present work concentrates on sermons, as this type of speech entails projecting one’s voice in order to be clearly heard, in contrast to the type of soft-spoken voice used during messes basses in lateral chapels, saying the rosary, or alternatively during musical chanting when intelligibility is not necessarily the focus. In this study, we consider the time period between the Middle Ages (13th–15th century), after the new Gothic cathedral was built, up to the Modern period (16th–19th century), which are two distinct periods concerning the circumstances for preaching.

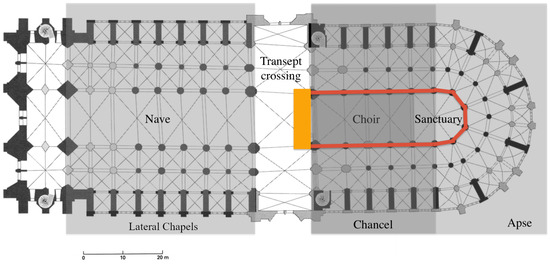

Although preaching to the people was a duty for bishops since Early Christian times and regularly mentioned in canon law, in Paris, preaching to the laity really developed during the 13th century, and became a popular spectacle during the Late Middle Ages and the Modern period, when lay people would gather inside the cathedral to hear famous preachers [1,2]. During the Middle Ages, preaching was performed in many locations including outside on the streets, in front of churches, and inside religious buildings of different types (cathedrals, convents, and parish churches) [1,3,4]. When taking place inside Notre-Dame during the Middle Ages, oration would have occurred either inside the choir or atop the jubé. During the Modern period, a wooden pulpit was built in the nave, on the north side between the 3rd and 4th columns starting from the transept towards the entrance doors, allowing the preacher to speak from above the crowd.1 Figure 1 provides a general reference plan of the layout of the Cathedral Notre-Dame de Paris.

Figure 1.

Plan of Notre-Dame with key architectural terms marked. The jubé location is indicated in orange and the clôture (choir enclosure) is indicated in red.

We hypothesise that prior to the installation of microphones and sound amplification/distribution systems in 1925 [6], significant variations in audibility for people gathered inside the nave were present. By combining the efforts of historians and acousticians, this study aims to reveal the areas where sermons would have been most clearly audible and intelligible based on the preacher’s location.

The structure of the remaining sections of this manuscript are as follows. Section 2 presents a detailed historical review of preaching at the Cathedral Notre-Dame de Paris from the Middle Ages to the Modern period, including discussions of sermon locations and pulpits. Section 3 presents an acoustic study using numerical simulations to evaluate the predicted levels of audibility and intelligibility of sermons in a variety of historical conditions. Section 4 discusses the results of the acoustical study through the perspective of the historical review.

2. Preaching

Preaching and teaching the faith was a task for bishops. Bishops could nevertheless delegate this task to authorised preachers and tended to preach only on specific occasions [7]. This was the case in Paris, similar to other episcopal cities. Paris was not, however, just any bishopric because it was also a capital city where the king was in residence. Even when canons elected the bishop, the king had a say in the matter and a bishop’s quality as a preacher would enter into consideration for that choice [8]. The cathedral was not, however, a parish and did not serve the lay people of Paris, who attended mass and heard preaching in their respective parish churches [9]. Every day, the community of canons organised the liturgy of the hours and high mass in the chancel of the cathedral, while private masses were offered in the numerous lateral chapels located on the sides of the nave and around the apse [10]. Canons’ religious duties took place inside the cathedral, with the exception of processions. Besides ordinary festive processions, canons could also be asked to organise special processions through the city, for example, to stop flooding or epidemics [11]. Finally, the cathedral also hosted grand events such as the singing of a Te Deum after a military victory, including in contemporary times (17 November 1918 and 26 August 1944), the baptism and funerals of important royal or political figures, and various solemn celebrations, including two coronations [10,12,13].

2.1. Preaching in the Gothic Cathedral in the Middle Ages

Maurice of Sully was chosen as bishop of Paris (1160–1196) because of his talents for preaching. He left behind many model sermons to help priests preach in their parishes each Sunday of the year. Whether they were first written in Latin and later translated into vernacular French or vice versa is debated, but the fact that these sermons circulated in French reveals that they were indeed intended for lay audiences [14]. Starting with him and continuing through the 13th century, preaching became an important and vital part of Parisian religious life [15]. His successor, Eudes of Sully, also recommended preaching to the laity as a foremost obligation for parish priests [14,16]. Following the council of Lateran IV (1215), bishops ordered parish priests to instruct lay people and preach frequently. Numerous books called Artes praedicandi were written on how to perform a sermon, what tone to take, and what gestures to avoid so as not to be confused with theatre actors [17,18,19]. With the creation of religious orders, such as Dominicans (1216) and Franciscans (1209), preaching became the prominent activity for these new friars. They needed the bishop’s authorisation to preach in Paris churches, including the cathedral.

Preaching was certainly considered a very important activity by the bishops of Paris. Guillaume d’Auvergne, bishop of Paris from 1228 to 1249, gave around 600 sermons [20]. The purpose of these sermons, however, was often to serve as models to encourage others to preach. Many sermons were written by bishops of Paris or canons of Notre-Dame de Paris during the Middle Ages, but that does not mean they were necessarily preached in the cathedral. They could be performed in other Parisian churches or convents. In fact, if a sermon was intended for the laity, it was best to give it in a smaller parish church, with a better chance for the audience to hear what was said. The Gothic cathedral was not the best church for preachers to be heard clearly and loudly because of the acoustical characteristics of the building’s architecture. With its monumental size and long reverberation, the acoustics likely rendered speech difficult to deliver and be understood, as will be discussed further in Section 3.

The audibility of preaching likely depended on where it took place. The cathedral can be divided into three sections (see Figure 1): the enclosed choir, where canons sang the liturgy; the nave, where the laity gathered; and the chapels along the perimeter of the cathedral, where specific celebrations took place (e.g., masses offered by private individuals or confraternities celebrating their devotions). Depending on the time period and the occasion, preaching occurred in different places inside the cathedral. Even if it is not that well documented, as collections of sermons rarely indicate where preaching took place, we can propose some hypotheses concerning the possible location of the preacher. They are founded in iconography and written sources. Preaching could take place inside the choir, where it was meant to be heard mostly by canons and other clerics. When the bishop preached, he could do so from his chair, or cathedra, also located in the choir. The cathedra’s location changed over time in Notre-Dame de Paris. It was originally placed at the end of the stalls, close to the altar, but it was later moved further away from the altar and closer to the nave [9] p. 135 and p. 146. Preachers could also talk from raised wooden platforms. For important religious celebrations, the marguilliers were in charge of adding chairs for honoured guests who had come to attend a service inside the choir. Marguillers were also in charge of adorning the chancel for festive occasions and royal visits [4].

When sermons were addressed to visiting laity on Sundays and feast days, preaching could be performed from the jubé, where two lecterns facing the nave were located. These lecterns served for reading from the Epistles and the Gospels during high masses. When a sermon followed readings, it was a natural location to preach, high above the crowd assembled in the nave.

2.2. Preaching During the Modern Period

The location of preaching changed considerably during the Modern period [21]. The Council of Trent (1545–1563) ordered clergy to teach the catholic faith to lay people through preaching to counteract the rippling effects of the Reformation. In continuity with the Middle Ages, preaching took place during Sundays and religious festivals, but also at other times, such as during periods dedicated to the preparation of major festivals: Advent before Christmas and Lent before Easter. The amount of preaching at Notre-Dame increased for the period of Advent, when the canon “theologal” was in charge of this task. For Lent, the chapter of canons decided in 1545 to set money apart to pay external preachers, often selected from among friars or priests of different religious orders, Jesuits, Capuchins, Oratorian fathers, and Benedictine monks, but also secular priests [2].

But who was in charge of selecting the preacher? At first, the chapter of Notre-Dame paid for the expense and chose the preacher, and then the expense was shared by the bishop/archbishop, and the nomination had to be a common decision. This could be an occasion of conflict. In 1632, the archbishop decided alone on the preacher for three years, and the canons were not pleased. In 1633, in protest, the canons decided not to pause the singing of the hours at the time of the sermon and the preacher had to stop speaking because hardly anyone could hear him. This episode led the archbishop to find a compromise with the canons, which was even registered before a notary, that a joint nomination should be the rule [2].

Notre-Dame, being one of the largest churches in Paris, could accommodate a large audience. Preaching at Notre-Dame became a privilege granted to experienced preachers, and it was important for Notre-Dame to attract renowned figures. In an ecclesiastical career, preaching at Notre-Dame was an honour that only surpassed preaching in front of their majesties. Queen Anne of Austria (1601–1668) came to listen to sermons in different churches and helped make the careers of many preachers whose sermons she had enjoyed [2]. Preaching at the Louvre, then the king’s residence, often happened after preaching at Notre-Dame [2]. The famous Jesuit Louis Bourdaloue, for example, preached for Lent at Notre-Dame and then in front of the court in 1670 [2]. Preaching in the cathedral was an honour and an important step in a clerical career. Because preaching was an important part of religious life in Paris during the Modern period, when a preacher came, announcements would be posted on the doors of a church. However, starting in 1646, a list of preachers was also printed for the periods of Lent and Advent in Paris [2]. The public could go from one church to another to listen to sermons, which had become something of a spectacle [21].2

The material conditions for preaching also evolved. After the destruction of the jubé and the opening of the chancel starting in 1699, two marble ambos were constructed that each included a wooden lectern, located at the border with the transept on each side of the chancel entrance, and may have been used for preaching [22]. They are both attested in the 1848 inventory. The new fashion was, however, the building of wooden pulpits. Many such pulpits were built in the naves of Parisian churches during the reign of Louis XIV. Pulpits, called chaires in French, were usually built on the side of the nave, placing preachers above the crowds of lay people who could stand or sit around them [23]. Building a pulpit was not a light expense: it cost some 1500 to 2000 livres for a simple wooden pulpit [2].

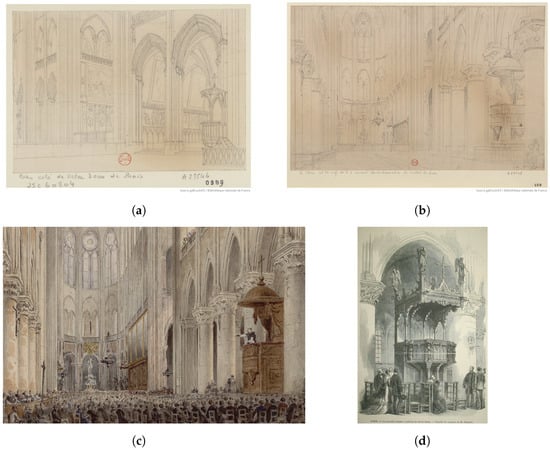

An anonymous 19th century drawing reveals a pulpit located, if the drawing is to be trusted, in the transept of Notre-Dame (see Figure 2a). It is simply adorned with a cross on top of the sounding board. Aside from two drawings of this pulpit (both found in the BnF), we have found no other evidence of a pulpit located in this position, nor information pertaining to when it would have been used. This pulpit is not very high but could nevertheless place the preacher above a crowd gathered to listen to the sermon.

In the mid-18th century, a large and sophisticated pulpit was built in the nave. During the 1757–1760 period, the design was entrusted to Michel-Ange Slodtz. He drew an ornate pulpit for Notre-Dame, adorned with many garlands [24]. It is visible in an anonymous drawing of Notre-Dame’s interior dated to the early 19th century (1800–1845), see Figure 2b. The details are not very precise, but one can see garlands on the lower part of the rather large, square pulpit, and a cupola-shaped sounding board surmounted with a cross. Sculptured curtains connect one with the other. The style is typical of the 18th century. It may have been damaged during the 1830 or 1848 revolutions, and was subsequently discarded. The 18th century pulpit is still indicated in the 1848 inventory but is noted as no longer in use [25]. In 1869, the archbishop of Besançon asked for it [26], so it is also possible that it was discarded because it was not “Gothic” enough for Viollet-le-Duc, and not because it was damaged.

The renewed interior furniture belonged to the last phase of the Viollet-le-Duc renovation of the cathedral. In 1868, Viollet-le-Duc designed a pulpit for preaching, and Mirgon, who had already been very active in the cathedral with his woodwork/carpentry business, reproduced the model in oak wood (see Figure 2d). It was finally adorned by Corbon, who made the statues of the apostles and of the trumpet-sounding angels located on top of the pulpit [27]. A letter addressed by Viollet-le-Duc to the Ministry of Justice and Cults on 29 September 1869 indicates that the sculptures were finished sometime before that date [25].3 Compared to the previous 18th century pulpit, the style had evolved. Instead of garlands, there were statues inserted and geometrical designs. The medieval and 19th-century passion for angels explains their presence on top of the sounding board. On the other side of the nave directly across from the pulpit, another monumental bench called banc d’oeuvre was built. It seated marguilliers during sermons. This was likely the most comfortable place to hear sermons and see the preacher. The location of the last two pulpits were between the third and fourth pillars from the transept. They served the same purpose: to allow preachers to be heard better in the nave.

Figure 2.

Nave pulpit imagery. (a) Small pulpit depicted in the transept. ©BnF [28]. (b) Pulpit by Slodtz in the nave. ©BnF [29]. (c) Lacordaire preaching from the pulpit. ©BnF [30]. (d) New nave pulpit, designed by Viollet-le-Duc [31].

During the 19th century, the Lenten “Conférences de Notre-Dame de Paris” were created in 1834 by the archbishop, Mgr Le Quelen. He invited the Dominican Father, Henri-Dominique Lacordaire, to preach in 1835 for Lent. This was a success and Lacordaire was again invited in the following two decades by Mgrs Affre and Sibour. Lacordaire was an extraordinary orator and his sermons attracted crowds. He preached for Lent or Advent in 1835, 1836, 1843, 1844, 1845, 1850, and 1851. He eventually published his sermons [32]. Auditors sometimes took the liberty to record and publish their notes. Lacordaire was not pleased with these unauthorised and unrevised publications of his sermons [33] p. 337. These publications nevertheless reveal the success of such events and the competitive aspect of preaching at the cathedral.

We also have anonymous engravings celebrating the event, see Figure 2c. When Henri-Dominique Lacordaire came to preach at Notre-Dame, chairs were placed around the pulpit, drawing a semi-circle where his voice could be heard. One can see the pulpit designed by Michel-Ange Slodtz. As was the practice in other parishes, chairs were set up for the event and could be rented. One can also see the 17th or 18th-century banc d’oeuvre. It was replaced by a more monumental one, designed by Viollet-le-Duc, which was destroyed in 1870.

In 1858, another preacher, the Jesuit Joseph Félix, published his conferences at Notre-Dame under the title “Le progrès par le christianisme”. He explained how these conferences, initiated by Archbishop Le Quelen, differed significantly from traditional parish preaching [34]. The cathedral is capable of accommodating thousands of people, and their presence is less directly tied to the routine of religious life. People came to listen to learned rhetoric and less to evangelical pieces of advice. These events could be so popular and crowded that rich laypeople sent their servants ahead to rent chairs.

3. Audibility and Intelligibility

A historical and art historical study of pulpits and preaching reveals important changes that took place during the Late Middles Ages and the Modern period. The concern for reaching out to the Christian population increased, and listening to preachers became a popular practice. Preachers addressed the crowds in a vernacular language and no longer in Latin, which few understood. The cathedral was one of the places where preaching took place in Paris. The size of the building, its height, and its reverberation impacted the audibility of the spoken voice. The particular acoustical characteristics of each phase of the building have to be considered to examine how well a loud-spoken voice can be heard.

3.1. Acoustic Simulation

Acoustic simulations have been employed in numerous studies concerning the acoustics of historic spaces, including religious buildings [35]. For the current study, a geometric acoustic simulation of Notre-Dame de Paris (CATT-Acoustic v9.1f, TUCT v2.0e, [36]) was used to evaluate the audibility and intelligibility of the spoken voice within various cathedral areas. The initial acoustic model of modern Notre-Dame was calibrated to measurements made in 2015 [37,38]. Modifications were made to this model to reflect the historic state of the cathedral in the medieval period. In particular, this includes modelling horseshoe-shaped choir stalls, the inclusion of the medieval stone jubé and clôture, and the inclusion of tapestries within the chancel and lateral chapels [5,39,40,41,42]. The acoustic properties of these decorative elements were modelled based on measurements of contemporaneous materials. Additionally, the nave and chancel were populated with a crowd density of approximately two people per 3 , drawn from measurements of worshippers reported in [43]. Additional treatment of the geometric acoustic model can be found in [38,44].

Acoustic simulations were run to examine differences in loudness and intelligibility throughout the cathedral as a function of source position (100,000 rays, 5 RIR calculation length, sufficient for investigating the speech context under study). As this study focuses on how preaching would be perceived within the cathedral, the source in the acoustic model was defined as a loud male voice spectrum and a human speech directivity [45,46]. Note that while this study discusses both the medieval and Modern periods, only the medieval acoustic model is used so that the only independent variable is source position.

3.2. Metrics

Audibility refers to the ability to hear and perceive sound, regardless of the clarity or understanding of its content. An audibility metric, such as sound pressure level (SPL), measures the degree to which a sound can be heard or detected by the listener but does not judge whether the content can be understood. An intelligibility metric, such as the speech transmission index (STI) or speech clarity metric (), instead gauges how well a speech signal can be understood.

The speech transmission index is a measure used to quantify the quality of speech communication in different environments. It primarily assesses the intelligibility of transmitted speech and evaluates how well listeners can be expected to understand the speech. The STI uses a scale ranging from 0 to 1, with 1 indicating perfect intelligibility and 0 representing complete unintelligibility. The results obtained from the STI assessment provide a useful indication of the quality of speech communication in a particular environment.

The STI considers both the temporal and spectral characteristics of the transmitted speech [47]. Temporal factors refer to time-related features, such as consonant perception, syllable duration, and pause lengths, which all contribute to the intelligibility of the speech. Spectral factors, conversely, pertain to the frequency content of the speech signal. Certain frequency bands are more crucial for speech comprehension, and the STI assesses whether these frequencies are adequately transmitted, with calculations made using 125 Hz to 8000 Hz bands, with more importance given to 500 Hz to 4000 Hz.

This metric is significantly affected by early reflections, reverberation, ambient noise levels, and the signal-to-noise ratio.

3.3. Suitability of STI Metric for Foreign Language

The phonetically balanced (PB) word lists used in the initial development of the STI were in the Dutch language [47]. One could imagine that the balance of phonemes in dialects of historic Latin or French may differ significantly from Dutch. However, a number of follow-up studies using PB word lists in other (modern) languages have shown that the STI and related tests such as the RASTI are well correlated for speech intelligibility [48,49,50].

While some authors suggest that the STI is dependent on language [51,52,53], it is clear that differences in language intelligibility become more similar when full sentences are used as a test metric instead of individual words. Likewise, studies show that non-native speakers perform more poorly on intelligibility tests than native speakers [54,55].

Considering the relatively small number of experts in historic dialects of French and Latin, it would be infeasible to do a PB listening test to see how well the STI correlates for use in the present study. It is worth pointing out the STI has been shown to work well with modern French and Italian [56,57], and that a number of studies have used the STI to evaluate the area of intelligibility around a speaker in a historically motivated context. For example, it has been applied to the battlefield speeches of Julius Ceaser [58], Queen Elizabeth I at Tilbury [59], assemblies of Roman subjects [60], and in Roman theatres [61]. Similar to prior studies [62], the choice of the STI therefore seems reasonable and suitably justified for use in the current context of comparative intelligibility analysis.

3.4. Results

Acoustic simulations were run with source positions corresponding to the locations of historic lecterns and pulpits inside Notre-Dame. These positions, corresponding to locations where orators would have addressed people inside the cathedral, include the bishop’s cathedra in the chancel, a location on top of the jubé facing into the nave, a pulpit near the transept, and the nave pulpit. Additionally, a source at the high altar facing the sanctuary was included. While there would not have been preaching from the altar, this position is useful for comparison with the other source positions. The STI and SPL computed across the ground level of the cathedral from these source positions can be seen in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Simulation results for STI (top) and SPL (bottom). (a) High altar; (b) Bishop’s cathedra; (c) jubé; (d) transept pulpit; (e) nave pulpit.

As the STI thresholds defining intelligibility in a cathedral are subjective, Table 1 reports the total floor area (in m2) in the cathedral where the STI exceeds thresholds ranging from 0.3 to 0.6. While the total area is useful for evaluating if there are physical mechanisms that aid or hinder intelligibility, listener’s location is not taken into account. Table 1 also reports the average STI in various locations in the cathedral as a function of source position. These areas include the chancel where the clergy would sit, the centre area of the transept, and the front, middle, and rear of the central nave. Table 2 reports the SPL of these cathedral areas. These results allow us to evaluate how various preaching locations privilege listeners in certain cathedral areas.

Table 1.

The STI in Notre-Dame as a function of source position, reported as the area (in m2) where the STI exceeds thresholds in the range of 0.3 to 0.6 and the average STI in various areas of the cathedral.

Table 2.

SPL in Notre-Dame as a function of source position.

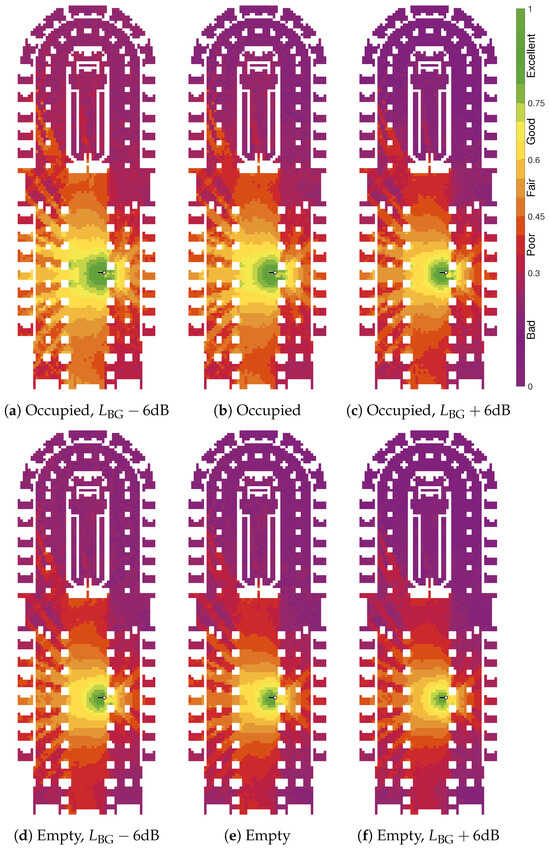

There are many factors that impact audibility and intelligibility in the cathedral, some of which can be taken into account. In particular, occupancy has a significant effect on the reverberation time in the cathedral, and this factors into both the SPL and STI. Background noise also plays a crucial role in the calculation of the STI. To account for these variables, Figure 4 shows the STI mapped across the ground floor of the cathedral for a source located in the nave pulpit in occupied and unoccupied conditions and with the level of the background noise increased and decreased by 6 dB. The SPL data for various listener areas in the cathedral are reported in the final row of Table 2, and the STI is reported in Table 3.

Figure 4.

STI maps from pulpit source with various noise levels in occupied and unoccupied conditions.

Table 3.

STI from the nave pulpit with different noise and occupancy conditions.

4. Discussion

It is readily apparent that the location of the preachers had a significant effect on how their voice will be perceived throughout the cathedral. It is no surprise that the loudness of a preacher is highest in the immediate vicinity and decreases as a function of distance. A skilled orator ought to speak in a loud, clear voice. Based on absolute thresholds, preaching from any location in the cathedral is likely audible throughout the entire cathedral, although the speaker’s loudness may be barely higher than the noise floor of the cathedral at great distances. While the STI is also highest around the speaker, the area of high intelligibility is quite small and decreases rapidly with distance.

It should be noted that the intelligibility of an orator is also sensitive to the direction they are facing. In the simulations presented here, the orientation of the source is fixed towards the centre of the nave or choir. Intelligibility may be significantly affected by a dynamic orator who moves about while speaking, though context clues may help a listener mitigate some purely acoustic effects.

While the analysis in this study focuses primarily on listeners located in the central nave and the benches of the choir, it is important to discuss how the architecture of the cathedral’s columns and choir screen effect sound propagation in the cathedral. While low-frequency sound diffracts around large structures, columns will block high-frequency content and create acoustic shadows. The direct sound will be blocked or significantly attenuated for listeners located behind columns or who do not have a direct line of sight to an orator. While these listeners will still hear the orator via reflected sound, the SPL and STI are both likely impaired by the occlusion. More information on how sound diffracts around Gothic columns can be found in [63], while a comprehensive investigation of the acoustic effects of the jubé and clôture can be found in [44]. It should also be mentioned that the elevated position of the nave pulpit helps ensure that a large area of the central nave will have a direct line of sight to the preacher.

4.1. Preaching in the Middle Ages

In the Middle Ages, preaching was likely performed from within the enclosed chancel of the cathedral for the clergy within the same space. When an orator is located at the bishop’s cathedra, the STI within the entire chancel is high (), but across the jubé, the STI in the transept and nave is significantly lower (). The SPL within the transept is also more than 10 dB greater within the chancel than outside the enclosure. These simulation results confirm that a listener outside the consecrated area of the cathedral would struggle to understand what was said by a preacher within the chancel.

While preaching did not take place from the altar, prayers would be said from the altar.4 It is thus interesting to compare this source location to that of the bishop’s cathedra. The soundfield in the chancel is approximately 6 dB quieter within the chancel when a source is located at the altar compared to the bishop’s cathedra. This can be explained by the altar being far from the chancel’s benches. Additionally, a priest at the altar would be facing east and, therefore, have their back to the clergy. While the sound level is approximately twice as quiet, the STI decreases by points, suggesting that intelligibility would be quite poor from this position. While the function of the altar would be reserved for religious rituals and not preaching, the diminished STI from this location also suggests that it would be a poor location for preaching.

Public announcements and the delivery of the Gospel would be performed from the top of the jubé. For the laity outside the chancel, this source position is a significant improvement. In the front of the nave and transept, the SPL is 6 dB to 10 dB higher than from the bishop’s cathedra. The STI rises by points in most of the nave and by points in the transept. This position certainly privileges listeners located in the closest portion of the nave and in the transept. From these positions, it is likely that listeners would be able to understand the spoken voice. From within the chancel, however, the STI drops below 0.2 and would likely be unintelligible even though the SPL remains sufficiently high ( .

As we do not know where the ambos were located or what they looked like, simulations were not computed from these positions. We can assume that if the ambo was located near the (former) location of the jubé, while lower, the simulation results would not be radically different.

4.2. Preaching in the Modern Period

In the Modern period, the location of preaching moved to the pulpit in the nave. From this position, the STI is throughout the nave and central transept, suggesting that listeners here would be able to understand the spoken voice. While positions closer to the nave pulpit would experience a higher SPL and STI, the position of the banc d’oeuvre directly opposite the nave pulpit is indeed a great position to listen to a preacher. The position of the nave pulpit also democratises the listening experience in the nave. Now, the portion of the nave furthest away from the chancel experiences a condition where audibility is high and intelligibility possible ( points). From within the chancel, however, the SPL and STI are quite low ( dB and 0.2 points, respectively), suggesting poor audibility and poor intelligibility.

The engravings of a pulpit in the arm of the transept are curious, as it is unclear when this pulpit was built or located in this position. We also lack knowledge of about the use of this pulpit. That said, it does not seem to be an ideal location for listeners located anywhere but within the transept. For listeners in the central portion of the transept, the STI is , and drops off the further one is away in the nave. In the chancel, the STI is , suggesting poor intelligibility. In Notre-Dame, there was a tradition of holding private masses in the lateral chapels. There are records of the clergy complaining about the loud noise associated with these services despite them being said in a quieter voice. While there is no evidence that the pulpit in the transept was used for activities not organised by the religious chapter of Notre-Dame, perhaps it was built by one of the confraternities.

4.3. Area of High STI

Irrespective of who is able to listen from certain areas of the cathedral, the nave pulpit position has the largest floor area with a high STI (see Table 1). This is likely because the nave is rather expansive, and the columns provide beneficial early reflections. While the chancel enclosure also provides beneficial early reflections, reflected in the high STI values observed in the chancel, the jubé and clôture impede acoustic transmission outside the chancel. This constrains the area where the for a source located at the bishop’s cathedra.

The areas where the or the are relatively similar for both the position on the jubé and the pulpit in the transept. The differences observed between these source locations for the area where the can be mostly explained by the fact that the jubé is much taller than the small pulpit in the transept, so the direct sound will be quieter. As observed in [41], the transept and deep triforium act as an acoustic barrier, impeding sound transmission between the chancel and the cathedral’s nave. The physical construction of Notre-Dame has a large impact on the area of intelligibility around sources in different locations of the cathedral.

4.4. Pulpit Acoustics

The design of a pulpit or lectern may have an effect on speech intelligibility. In particular, the canopy over a pulpit (abat-voix in French) may eliminate a strong, late reflection off the ceiling. In churches with high ceilings like Notre-Dame, an acoustic canopy over the pulpit may increase the STI at moderate distances and decrease the STI at large distances, though the effect is likely negligible [64,65]. Even in the case of a large reflector, the STI is likely to change by only a small amount [66]. Reymond [67] argues that pulpit canopies and reflectors serve a more symbolic function than an acoustic one. Crowning and decorating a pulpit reinforces the gravitas and seriousness of the act of preaching.

The present simulations did not consider acoustic effects associated with the pulpit material and geometry. The STI metric is more likely to be affected by the elevation and direction a preacher faces than the design of the pulpit [67,68,69].

4.5. Effect of Background Noise and Reverb Time

As reverberation time and background noise have a significant effect on the STI, simulations were calculated for the cathedral in an occupied and unoccupied state and with the background noise modified by dB for the source in the nave pulpit. The STI is higher when the cathedral is occupied than when it is unoccupied. This is primarily because the increased absorption due to the occupants significantly decreases the church’s reverberation time. The area where the approximately doubles when moving from the unoccupied state to the occupied state, and the area where the increases by about 25%.

A reverberant cathedral such as Notre-Dame is a challenging environment for speech intelligibility. When taking background noise into consideration, the area where the fluctuates in the range of 21% to 55% and the area where the fluctuates by 5% to 13%. Even when the background noise level is set to a low level, the area with a high STI () is quite small and is only about 6% of the floor area of the cathedral. At the same noise level, nearly 40% of the floor of the cathedral has an . These results are in line with the results of Alvarez-Morales and Martellotta [69], which show that despite a significant reduction in reverberation time when a cathedral is occupied, the absolute reverberation time remains sufficiently long as to render a poor STI throughout much of the cathedral.

5. Conclusions

The functional use of the cathedral changed between the Middle Ages and Modern period. While proclamations to the public would have occurred in Notre-Dame in the Middle Ages (likely from atop the jubé), in this time period, discourse by the religious chapter of the cathedral would have been contained to the chancel. In contrast, preaching to the general population occurred from a pulpit located centrally in the nave in the Modern period. The areas of the cathedral where listeners would be able to hear and understand orators speaking from these distinct positions are completely different.

Geometric room acoustic simulations were used to assess speech audibility and intelligibility in the cathedral using SPL as a predictor for audibility and the STI as a predictor for speech intelligibility. While a loud voice may be audible throughout the majority of the cathedral, the area of adequate intelligibility is localised in the immediate area around preaching locations. Simulation results confirm that preaching within the chancel, as performed in the Middle Ages, would likely have poor intelligibility outside of this enclosed area of the cathedral. For proclamations given from atop the jubé, intelligibility in the nave would drop off with distance and be poor within the chancel. In the Modern period, the majority of the central nave would likely experience a sufficiently high STI such that a preacher may be understood while the chancel experiences poor intelligibility. As a result, distinguished clergy may have listened to sermons from a banc d’oeuvre and chairs located directly opposite the pulpit. Simulations reveal that this location would have good intelligibility in addition to a good view of the pulpit.

As factors such as reverberation time and background noise can have a significant effect on the STI, additional simulations were run to evaluate how a crowd in the cathedral might affect speech audibility and intelligibility. As expected, occupancy reduces the reverberation time in the cathedral. And, as observed in Alvarez-Morales and Martellotta [69], the STI increases as a result of the reduced reverberation time. Further, the STI was calculated from simulations with dB background noise levels. The results of these simulations reveal that background noise has a limited effect on the STI as the long reverberation time of Notre-Dame already renders the area of high STI localized around the position of oration. However, it must be stated that it is difficult to accurately assess the effect of background noise on the STI, considering we do not have good estimations for the level and spectrum of noise in cathedrals in these historic states.

The simulations presented here contrast preaching locations within Notre-Dame in the Middle Ages and Modern period. In the Middle Ages, some public oration could have taken place on the parvis outside the cathedral. It would be worth further exploration of how well listeners could hear and understand a preacher outside the cathedral compared to one speaking from a pulpit inside. Finally, electronic sound reinforcement systems became prevalent in the 20th century, with amplification and distributed speakers almost certainly increasing audibility and intelligibility throughout the entire cathedral.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, B.C.C. and E.K.C.-D.; formal analysis, E.K.C.-D.; funding acquisition, B.F.G.K.; investigation, E.K.C.-D.; methodology, E.K.C.-D. and B.C.C.; project administration, B.F.G.K.; resources, B.C.C.; supervision, B.F.G.K.; visualisation, E.K.C.-D.; writing—original draft, E.K.C.-D. and B.C.C.; writing—review and editing, E.K.C.-D., B.F.G.K., and B.C.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Funding has been provided by the European Union’s Joint Programming Initiative on Cultural Heritage project PHE (Grant No. 20-JPIC-0002-FS, http://phe.pasthasears.eu (accessed on 22 November 2024)), the French project PHEND (Grant No. ANR-20-CE38-0014, http://phend.pasthasears.eu (accessed on 22 November 2024)), the https://www.culture.gouv.fr/Thematiques/Sciences-du-patrimoine/Thematiques-de-recherche/Le-chantier-de-Notre-Dame-de-Paris (accessed on 22 November 2024), and the Notre-Dame de Paris of the Ministère de la Culture/CNRS, the Institut universitaire de France, UMR 8167, and Sorbonne University.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 | The jubé was likely 6 high [5], while the pulpit height would have been more on the order of 3 . |

| 2 | See [2] for a list of the sermons attended by an anonymous person, probably a cleric himself, in 1660 during Lent: twice at Notre-Dame to hear Jean-Baptiste de la Barre, but mostly in different parishes. |

| 3 | Lettre de Viollet-le-Duc au Ministère de la Justice et des Cultes à propos de la liquidation des travaux datée du 29 September 1869, MAP, 1998/035/17-73. |

| 4 | While prayers at the altar would be spoken in a quieter voice than necessary for preaching, the same SPL and source spectrum were used in simulations. |

References

- Bériou, N. L’Avènement Des Maîtres de la Parole. La Prédication à Paris au XIIIe Siècle; Brepols: Turnhout, Belgium, 1998; Volumes 1 and 2. [Google Scholar]

- Brian, I. Prêcher à Paris sous l’Ancien Régime (XVIIe–XVIIIe Siècles); Classique Garnier: Paris, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, H. Le Métier de Prédicateur en France Septentrionale à la Fin du Moyen Age: (1350–1520); CERF: Paris, France, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Lecoy de la Marche, A. La Chaire Française au Moyen âge, Spécialement au XIIIe Siècle; Didier et Cie Libraires éditeurs: Paris, France, 1868; pp. 213–219. [Google Scholar]

- Gillerman, D.W. The Clôture of Notre-Dame and Its Role in the Fourteenth Century Choir Program; Outstanding Dissertations in the Fine Arts, Garland Pub.: New York, NY, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- National Catholic Welfare Council News Service. Loud Speaker used in Notre Dame. N.C.W.C. Editor. Sheet 1925, 5, 2. Available online: https://thecatholicnewsarchive.org/?a=d&d=cns19250406-01.1.1 (accessed on 25 October 2024).

- Olivar, A. La Predicación Cristiana Antigua; Herder: Barcelona, Spain, 1991; 997p. [Google Scholar]

- Brian, I.; Vincent, C. Le clergé de Notre-Dame. In Notre-Dame. Une Cathédrale dans la Ville des Origines à Nos Jours; Bove, B., Gauvard, C., Eds.; Belin: Paris, France, 2022; pp. 133–161. [Google Scholar]

- Gauvard, C.; Le Gall, J.M. Notre-Dame de Paris et le roi. In Notre-Dame. Une Cathédrale dans la Ville des Origines à Nos Jours; Bove, B., Gauvard, C., Eds.; Belin: Paris, France, 2022; pp. 299–329. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, C. Music and Ceremony at Notre Dame of Paris, 500–1550; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1989; 375p. [Google Scholar]

- Julerot, V. Les processions du chapitre de Notre-Dame de Paris à la fin du Moyen Âge. Pérennité et remise en cause. Hist. Urbaine 2021, 60, 127–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Gall, J.M. Le théâtre de la mort à Notre-Dame, XVIe–XVIIIe siècles. In Notre-Dame de Paris, 1163–2013; Giraud, C., Ed.; Brepols: Turnhout, Belgium, 2013; pp. 435–454. [Google Scholar]

- Tulard, J. Le Sacre de L’Empereur Napoléon. Histoire et Légende; Fayard: Paris, France, 2004; p. 200. [Google Scholar]

- Zink, M. Parler aux Simples Gens: Un Art Médiéval; Cerf: Paris, France, 2023; p. 240. [Google Scholar]

- Longère, J. La Prédication Médiévale; Etudes augustiniennes Paris: Paris, France, 1983; Volume 9. [Google Scholar]

- Bériou, N. Maurice et Eudes de Sully et la Cathédrale de Paris. In Notre-Dame de Paris, 1163–2013; Giraud, C., Ed.; Brepols: Turnhout, Belgium, 2013; pp. 19–28. [Google Scholar]

- Bériou, N. Religion et Communication. Un Autre Regard Sur la Prédication au Moyen Âge; Droz: Genève, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bériou, N. Les Pouvoirs de L’éloquence: Prédication et Pastorale dans la Chrétienté Latine (XIIe–XIIIe Siècle); Droz: Genève, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Bouhaïk-Gironès, M.; Polo de Beaulieu, M.A. Prédication et Performance du XIIe au XVIe Siècle; Garnier: Paris, France, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Morenzoni, F. Les explications liturgiques dans les sermons de Guillaume d’Auvergne. In Prédication et Liturgie au Moyen Âge. Études Réunis par Nicole Bériou et Franco Morenzoni; Brepols: Turnhout, Belgium, 2008; pp. 255–269. [Google Scholar]

- Simiz, S. Une “révolution” de la prédication catholique en ville? Début XVIe siècle–seconde moitié du XVIIe siècle. Hist. Urbaine 2012, 34, 33–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durand, J.; Dion-Tenenbaum, A.; Bimbenet-Privat, M.; Meunier, F.; Bennet, L. Le Trésor de Notre-Dame de Paris. Des Origines à Viollet-le-Duc; Éditions Hazan: Vanves, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, P. La chaire: Instrument et espace de la prédication catholique. In Annoncer l’Evangile (XVe–XVIIe Siècle); Cerf: Paris, France, 2006; pp. 397–415. [Google Scholar]

- Souchal, F. Les Slodtz, Sculpteurs et Décorateurs du Roi (1685–1764); de Boccard, É., Ed.; Didier et Cie Libraires: Villeurbanne, France, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Ricaud, E. La Restauration Intérieure de la Cathédrale de Paris au XIXe Siècle; Internal Report; Sorbonne Université: Paris, France, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Besançon. Lettre de L’archevêque de Besançon; Archives Nationales: Pierrefitte-sur-Seine, France, 1868; F/19/7800, Dossier n. 11.

- Ministère de la Culture. Plateforme du Patrimoine. 2022. Available online: https://www.pop.culture.gouv.fr/notice/palissy/PM75000692 (accessed on 22 November 2024).

- Bibliothèque Nationale de France. Bas-côté de Notre-Dame de Paris: Dessin. 2013. Available online: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b103032779 (accessed on 22 November 2024).

- Bibliothèque Nationale de France. Le choeur et la nef de Notre-Dame, avant la restauration de Viollet-le-Duc: Dessin. 2013. Available online: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b10303276v (accessed on 25 October 2024).

- Bibliothèque Nationale de France. 2013. Conférence du Père Lacordaire à Notre-Dame: Dessin. Available online: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b10303311h (accessed on 22 November 2024).

- La nouvelle chaire de l’église Notre-Dame. L’Illus. J. Univers. 1868, LII, 24.

- Lacordaire, H.D. Conférences de Notre-Dame de Paris par Henry-Dominique Lacordaire: Années 1835–1836–1843; Sagnier et Bray: Paris, France, 1853. [Google Scholar]

- Boutry, P. Le prédicateur des villes et le prédicateur des champs: Lacordaire À Ars (4 Mai 1845). Rev. Sci. Relig. 2004, 78, 335–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Félix, J. Le Progrès Par le Christianisme: Conférences de Notre-Dame de Paris; Librairie Adrien Le Clère et Cie: Paris, France, 1861; Volume 6. [Google Scholar]

- Girón, S.; Álvarez Morales, L.; Zamarreño, T. Church acoustics: A state-of-the-art review after several decades of research. J. Sound Vib. 2017, 411, 378–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalenbäck, B.I. CATT-A v9.1g:1 User’s Manual, Computer Aided Threatre Technique; CATT-Acoustic: Gothenburg, Sweden, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Postma, B.N.J.; Katz, B.F.G. Creation and calibration method of acoustical models for historic virtual reality auralizations. Virtual Real. 2015, 19, 161–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postma, B.N.J.; Katz, B.F.G. Acoustics of Notre-Dame Cathedral de Paris. In Proceedings of the 22nd International Congress on Acoustics, Buenos Aires, Argentina, 5–9 September 2016; pp. 5–9. [Google Scholar]

- Mullins, S.; Canfield-Dafilou, E.K.; Katz, B.F.G. The Development of the Early Acoustics of the Chancel in Notre-Dame de Paris: 1160–1230. In Proceedings of the Acoustics of Ancient Theatres—International Symposium, Verona, Italy, 6–8 July 2022; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canfield-Dafilou, E.K.; Mullins, S.; Katz, B.F.G. Opening the Lateral Chapels and the Acoustics of Notre-Dame de Paris: 1225–1320. In Proceedings of the Acoustics of Ancient Theatres—International Symposium, Verona, Italy, 6–8 July 2022; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canfield-Dafilou, E.K.; Buchs, N.; Caseau Chevallier, B. The Voices of Children in Notre-Dame de Paris during the Late Middle Ages and the Modern Period. J. Cult. Herit. 2022, 65, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltzer, R.A. The Geography of the Liturgy at Notre-Dame of Paris. In Ars Antiqua: Organum, Conductus, Motet; Music in Medieval Europe; Roesner, E.H., Ed.; Ashgate: Farnham, UK; Burlington, VT, USA, 2009; pp. 59–78. [Google Scholar]

- Sabbagh, M.; Elkhateeb, A. Effect of Body Posture on Sound Absorption by Human Subjects. Appl. Acoust. 2021, 183, 108317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullins, S.S. Des voix du Passé: The Historical Acoustics of Notre-Dame de Paris and Choral Polyphony. Ph.D. Thesis, Sorbonne Université, Paris, France, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- ANSI/ASA S3.5-1997; Methods for Calculation of the Speech Intelligibility Index. Acoustical Society of America: Melville, NY, USA, 1997.

- Marshall, A.; Meyer, J. The directivity and auditory impressions of singers. Acta Acust. United Acust. 1985, 58, 130–140. [Google Scholar]

- Steeneken, H.J.; Houtgast, T. A physical method for measuring speech-transmission quality. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1980, 67, 318–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houtgast, T.; Steeneken, H. A multi-language evaluation of the RASTI-method for estimating speech intelligibility in auditoria. Acta Acust. United Acust. 1984, 54, 185–199. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, B.W.; Kalb, J.T. English verification of the STI method for estimating speech intelligibility of a communications channel. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1987, 81, 1982–1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, P.; Mo, F.; Kang, J. Relationship between Chinese speech intelligibility and speech transmission index under reproduced general room conditions. Acta Acust. United Acust. 2014, 100, 880–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J. Comparison of speech intelligibility between English and Chinese. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1998, 103, 1213–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galbrun, L.; Kitapci, K. Speech intelligibility of English, Polish, Arabic and Mandarin under different room acoustic conditions. Appl. Acoust. 2016, 114, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitapci, K. Speech Intelligibility in Multilingual Spaces. Ph.D. Thesis, Heriot-Watt University, Edinburgh, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- van Wijngaarden, S.J.; Bronkhorst, A.W.; Houtgast, T.; Steeneken, H.J. Using the Speech Transmission Index for predicting non-native speech intelligibility. J. Acous. Soc. Am. 2004, 115, 1281–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecumberri, M.L.G.; Cooke, M.; Cutler, A. Non-native speech perception in adverse conditions: A review. Speech Commun. 2010, 52, 864–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimpfer, V.; Andeol, G.; Blanck, G.; Suied, C.; Fux, T. Development of a French version of the Modified Rhyme Test. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2020, 147, EL55–EL61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astolfi, A.; Bottalico, P.; Barbato, G. Subjective and objective speech intelligibility investigations in primary school classrooms. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2012, 131, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boren, B. Acoustic Simulation of Julius Caesar’s Battlefield Speeches. Acoustics 2018, 1, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boren, B. Acoustic simulation of Elizabeth I at Tilbury. In Proceedings of the 23rd International Congress on Acoustics, Aachen, Germany, 9–13 September 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kopij, K.; Pilch, A. The Acoustics of Contiones, or How Many Romans Could Have Heard Speakers. Open Archaeol. 2019, 5, 340–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzetti, M.C. The Performances at the Theatre of the Pythion in Gortyna, Crete. Virtual Acoustics Analysis as a Support for Interpretation. Open Archaeol. 2019, 5, 434–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Đorđević, Z.; Novković, D.; Andrić, U. Archaeoacoustic Examination of Lazarica Church. Acoustics 2019, 1, 423–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, A. Acoustics of Historic Buildings: Intercomparison of Numerical Methods for Coupled Spaces & Sound Scattering by Piers and Columns in Gothic and Classical Architecture. Ph.D. Thesis, Sorbonne Université, Paris, France, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Desarnaulds, V.; Chauvin, P.; Carvalho, A. Acoustic effectiveness of pulpit reflector in churches. In Proceedings of the 17th International Congress on Acoustics, Rome, Italy, 2–7 September 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Desarnaulds, V.; Chauvin, P.; Carvalho, A. Chaires et abat-voix: Mythe ou réalité acoustique? Journées d’Automne de la Société Suisse d’Acoustique 2001. Available online: https://repositorio-aberto.up.pt/bitstream/10216/457/2/67364.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2024).

- Epstein, D. Evaluation of the effectiveness of pulpit reflectors in three Dutch churches using Rasti measurements. In Proceedings of the Internoise and Noise Conference, Sydney, Australia, 2 December 1991; pp. 823–826. [Google Scholar]

- Reymond, B. Les chaires réformées et leurs couronnements. Études Théol. Relig. 1999, 74, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soeta, Y.; Ito, K.; Shimokura, R.; Sato, S.i.; Ohsawa, T.; Ando, Y. Effects of sound source location and direction on acoustic parameters in Japanese churches. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2012, 131, 1206–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Morales, L.; Martellotta, F. A geometrical acoustic simulation of the effect of occupancy and source position in historical churches. Appl. Acoust. 2015, 91, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).