Finding the Lost 16th-Century Monastery of Madre de Deus: A Pedagogical Approach to Virtual Reconstruction Research

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Finding the Lost 16th-Century Monastery of Madre de Deus

1.2. Why HBIM? A Theoretical Background

2. Materials and Methods

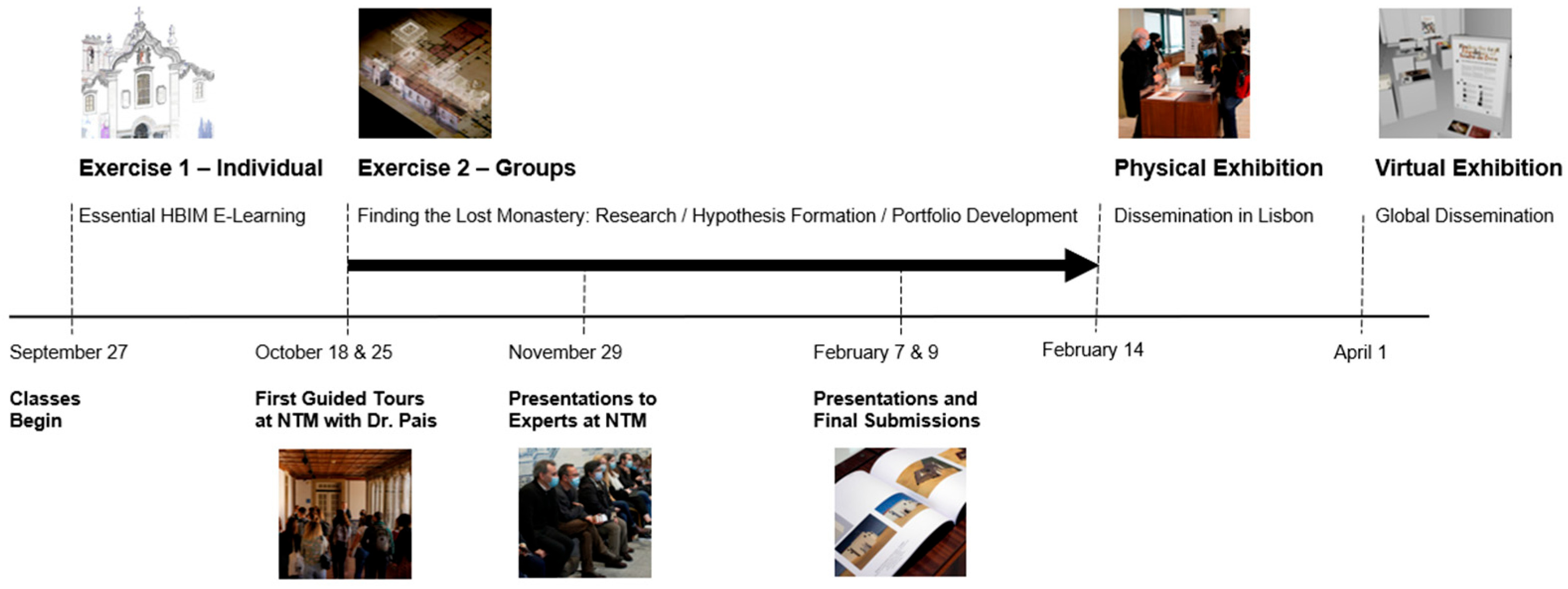

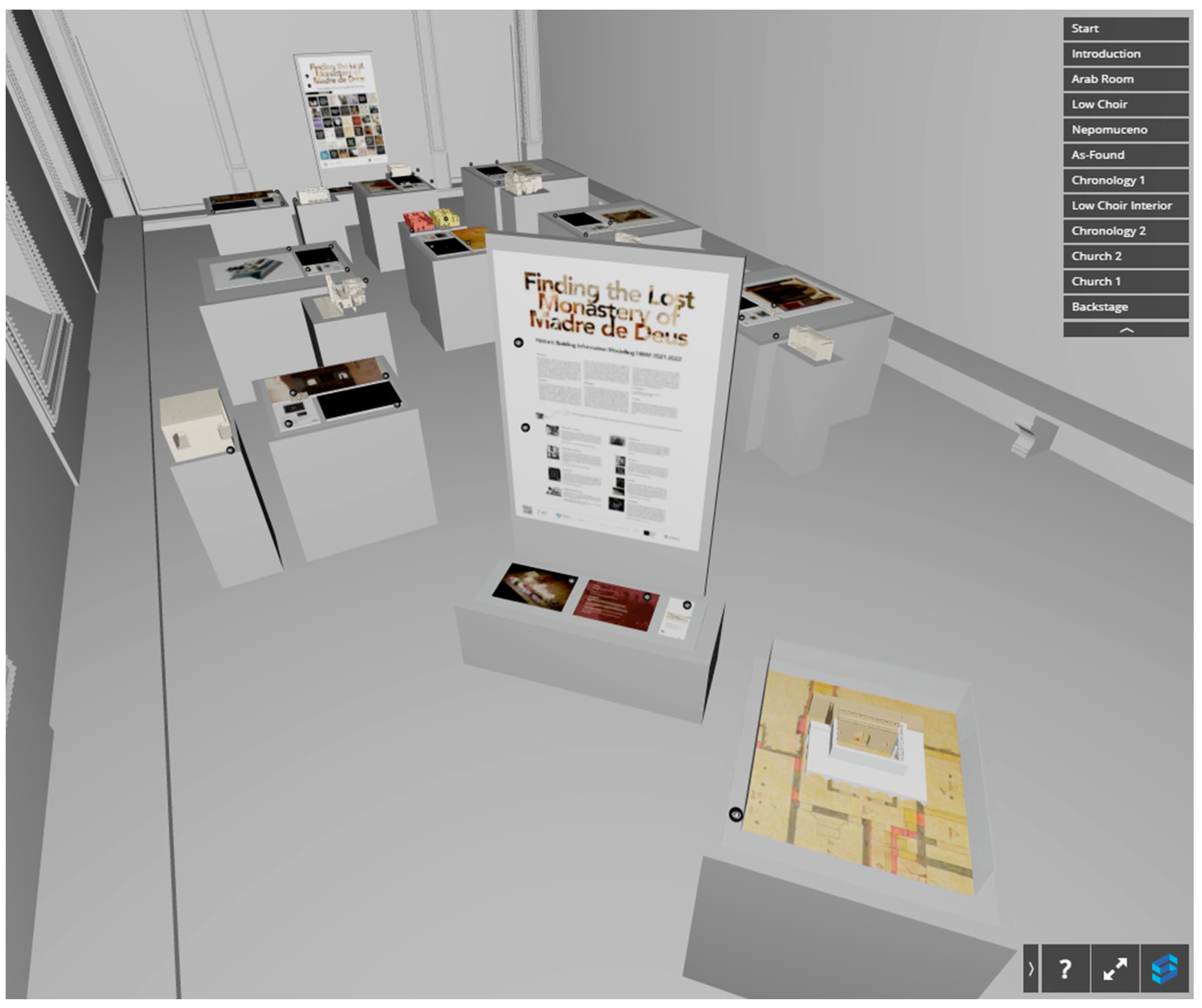

2.1. Designing a Pedagogical Model for HBIM

2.2. Research Materials

2.2.1. Historic Data

- A chronicle known as News of the Founding of the Madre de Deus Convent of the Barefoot Religious Women of Lisbon (Noticia da Fundação do Convento da Madre de Deos das Religiozas Descalças de Lisboa), 1639 [25]. The text provides a chronicle of the origins of the Monastery of Madre de Deus from the 16th to 17th-century. The text combines conjunctures, material evidence, and oral traditions passed down within the monastery to concretize aspects of daily life and spaces of the building. While the authorship of the text is attributed to Maria do Sacramento between 1639 and 1652, it is written in the form of dialogues supposedly composed of real conversations that follow the structure of questions and answers. Fortunately, at this point in history, some religious chroniclers in Portugal had become increasingly interested in historical representation out of fear that the memories of their monastic communities, origins, and architecture would be lost [26] (8–9). It is a fortunate document to have survived for much of what we know today would not be possible without it.

- A historic painting (Appendix A, Figure A1) by an unknown author called Arrival of the Relics of Saint Auta to the Church of Madre de Deus (Chegada das Relíquias de Santa Auta à Igreja da Madre de Deus), c. 1522 [27]. This is the earliest known visual depiction of the Monastery of Madre de Deus, providing us with crucial historical information about the original façade. There is much debate about its historic accuracy and there are numerous possible interpretations of how it relates to the building today. Each radically transforms our understanding of the original 16th-century building. The painting is originally from the Santa Auta Altarpiece (Retábulo de Santa Auta), a polyptych of five oil paintings on oak wood from around 1520–1525.

- A historic painting (Appendix A, Figure A2) by an unknown author called Saint Francis Delivering the Statutes of the Order to Saint Claire (S. Francisco Entregando os Estatutos da Ordem a Santa Clara), 1515 [28]. To the far left, Queen D. Leonor can be seen dressed in her black Clarissa gown. She observes St. Clare receiving the rule from St. Francis. Across different groups, the students used the image to speculate on various aspects of the interior reconstruction, including the columns, flooring, altar, and other details. The painting was likely part of the Polyptych of the Convent of Madre de Deus (Políptico do Convento da Madre de Deus) [29], c. 1515, though this cannot be said for certain.

- A historic painting (Appendix A, Figure A3) called Tryptic of the Presentation of the Child in the Temple (Tríptico da Apresentação do Menino no Templo), c. 1501–1525 [30]. The painting is by the Flemish painter Goswin van der Weyden. It was commissioned to decorate the church of the Monastery of Madre de Deus. Although it is uncertain whether the painting depicts the actual interior of the church, the heraldic symbols on the left panel suggest it was of royal origin, painted specifically for the monastery, around the time of its founding.

- A contract signed between D. Joana de Ataíde and the masons Rodrigo Afonso and Pêro de Bruges for the architectural work of the Church of the Monastery of Nossa Senhora da Rosa, in Mouraria, 1517 [31]. The contract compares the church of Madre de Deus to the church of Nossa Senhora da Rosa in Mouraria and provides a list of dimensions of the original church.

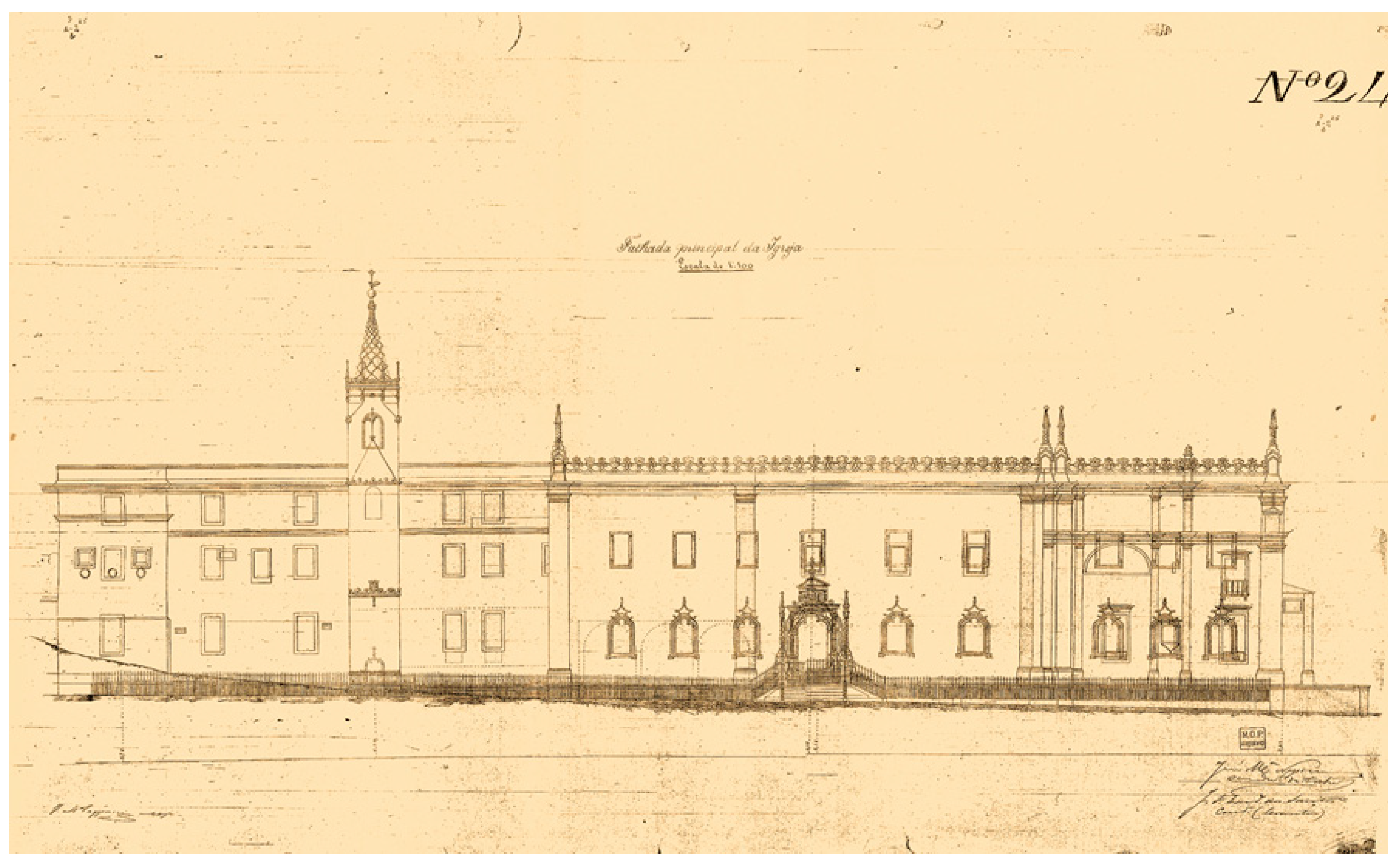

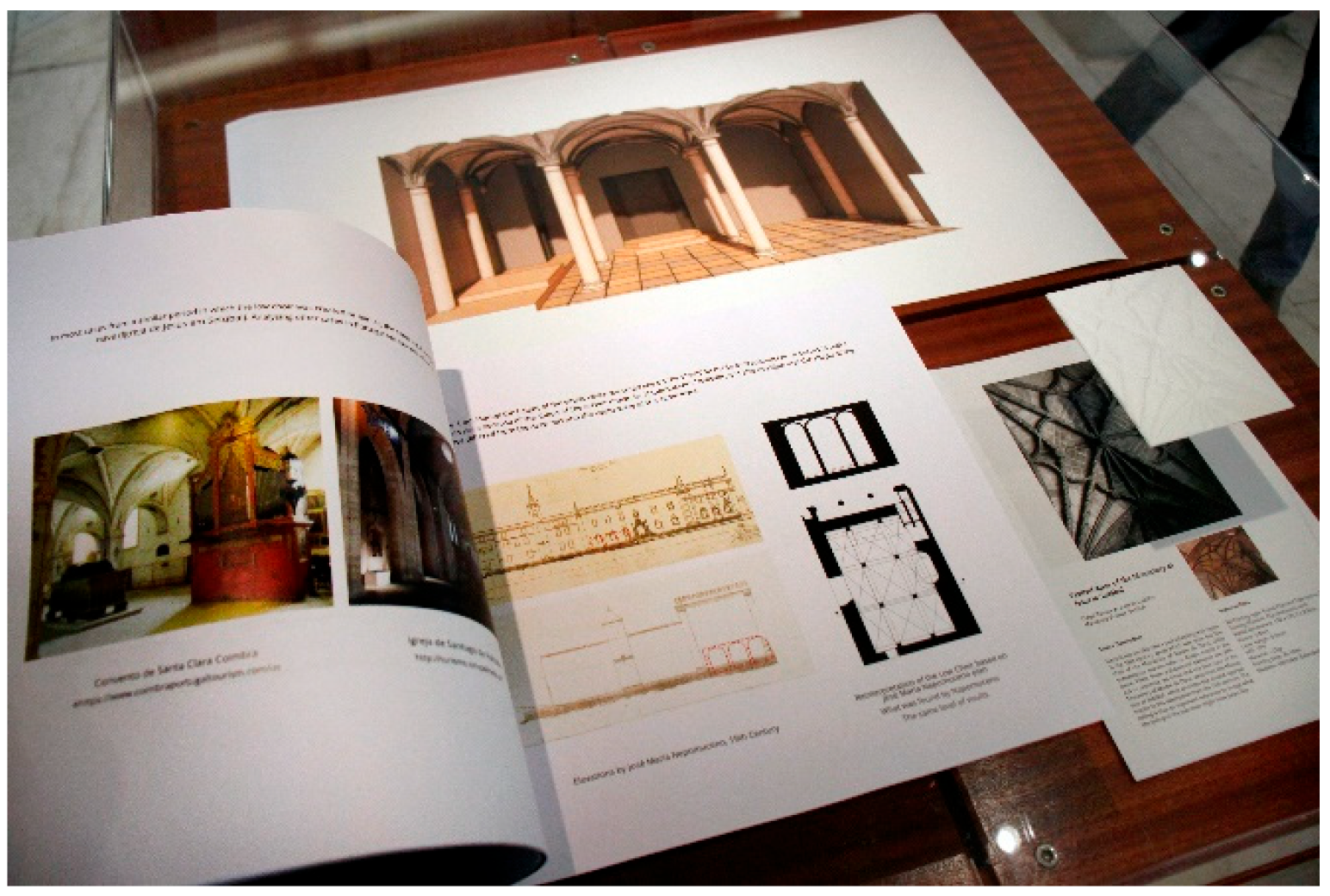

- 19th-century floorplans (Appendix A, Figure A4) and elevations (Appendix A, Figure A5) by the architect José Maria Nepomuceno when he repurposed the building from a monastery to the Maria Pia Asylum [32]. The plan drawing is important because it contains various historical layers involved in the intervention work, some believed to date back to the 16th-century. The drawing is color-coded, including elements in dark grey (elements that were found and kept), yellow (elements that were found and demolished), and red (new interventions).

- Historic photographs of the main cloister and Arab Room of the National Tile Museum [33]. The photos are from the SIPA Thesaurus, an archival system for architectural heritage by Direção-Geral do Património Cultural–DGPC at the Forte de Sacavém, Lisboa, Portugal.

- Five illustrations of the building’s façade from across history. (1) An engraving, “Vista do Convento da Madre de Deus” by Dirk Stoop, c. 1662 [34]. (2) A tile panel from the Consistory Room of the Church of the Third Order of São Francisco in São Salvador da Baía, Brazil, 18th-century, with the primitive church of Madre de Deus seen from the south [35]. (3) A tile panel from the Large Panorama of Lisbon, c. 1700, by Gabriel de Barco [36]. (4) A drawing, “N.S. Madre Deos” by Luiz Gonzaga Pereira, 1833 [37]. (5) An engraving, “Convento da Madre de Deus” by Barbosa de Lima, 1862 [38].

2.2.2. Laser Scanning Survey

2.2.3. Previous Research

- Report and photographs on the archaeological monitoring of the work to rehabilitate the D. Manuel Room of the National Tile Museum, by Maria Antónia de Castro Athayde Amaral, 2014 [40].

- A recent publication about the monastery found in: Igreja Da Madre De Deus: História, Conservação e Restauro, 2002 [44].

3. Results

3.1. Modeling the National Tile Museum “As-Found”

3.2. Original Church—Hypothesis 1

“(…) in that house they will build a Church that must be thirty-three spans wide [7.26 m] and fifty-six spans long [12.32 m] because Madre de Deus has so much, and the lady wants it from that greatness. The church will have a chapel twenty spans wide [4.40 m] and twenty-one spans long [4.62 m] that will be the head and will be all the height of Madre de Deus and the altars will have its steps like the altars of Madre de Deus.”[31] (p. 76—translated by the authors from its original Portuguese)

3.3. Original Church—Hypothesis 2

3.4. Original Church—Hypothesis 3

3.5. Arab Room

3.6. Modeling Nepomuceno’s Plans

3.7. Low Choir

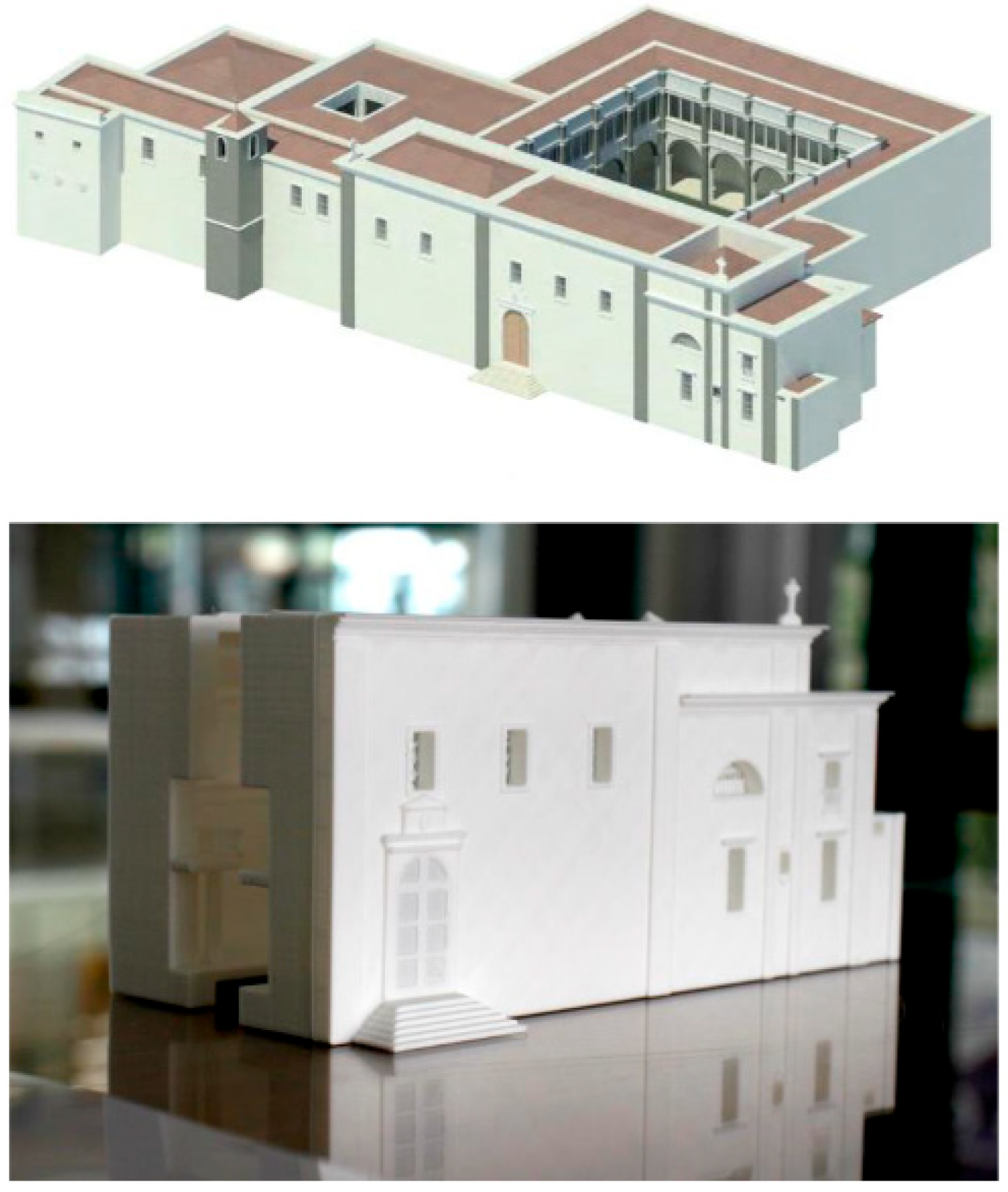

3.8. Reconstruction and 3D Print of the 17th-Century Church of Madre de Deus

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Paintings and Drawings Used in the Virtual Reconstruction

References

- Carneiro de Sousa, I. A rainha D. Leonor e a invenção da ‘cidade’ religiosa e espiritual de Xabregas. In Actas das Sessões: II Colóquio Temático Lisboa Ribeirinha; Câmara Municipal de Lisboa, Departamento de Património Cultural/Divisão de Arquivos: Lisboa, Portugal, 1997; pp. 71–105. [Google Scholar]

- Brumana, R.; Georgopoulos, A.; Oreni, D.; Raimondi, A.; Bregianni, A. HBIM for Documentation, Dissemination and Management of Built Heritage. The Case Study of St. Maria in Scaria d’Intelvi. Int. J. Herit. Digit. Era 2013, 2, 433–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fai, S.; Rafeiro, J. Establishing an Appropriate Level of Detail (LoD) for a Building Information Model (BIM)—West Block, Parliament Hill, Ottawa, Canada. ISPRS Ann. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2014, II–5, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, L.; Graham, K.; Grunt, T.; Gallant, M.; Rafeiro, J.; Fai, S. The Evolution of Modelling Practices on Canada’s Parliament Hill: An Analysis of Three Significant Heritage Building Information Models (HBIM). Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2019, XLII–2/W11, 419–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agustin, L.D.; Quintilla, M.G. Virtual Reconstruction in BIM Technology and Digital Inventories of Heritage. ISPRS-Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2019, XLII–2/W15, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fregonese, L.; Achille, C.; Adami, A.; Fassi, F.; Spezzoni, A.; Taffurelli, L. BIM: An Integrated Model for Planned and Preventive Maintenance of Architectural Heritage; Digital Heritage: Granada, Spain, 2015; pp. 77–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santini, S.; Canciani, M.; Borghese, V.; Sabbatini, V.; Sebastiani, C. From Digital Restitution to Structural Analysis of a Historical Adobe Building: The Escuela José Mariano Méndez in El Salvador. Heritage 2023, 6, 4362–4379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, J.; Tomé, A. Multidisciplinarity and accessibility in heritage representation in HBIM Casa de Santa Maria (Cascais)—A case study. Digit. Appl. Archaeol. Cult. 2021, 23, e00203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benítez, A.J.; Prieto Souto, X.; Armenteros, M.; Stepanian, E.M.; Cantos, R.; García-Villaraco, M.; Solano, J.; Manzanares, A.G. Multi-Camera Workflow Applied to a Cultural Heritage Building: Alhambra’s Torre de la Cautiva from the Inside. Heritage 2022, 5, 21–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, L.; Fai, S. Developing Verification Systems for Building Information Models of Heritage Buildings with Heterogeneous Datasets. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2017, XLII–2/W5, 125–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- London Charter. London Charter for the Computer-Based Visualisation of Cultural Heritage. 2012. Available online: http://www.londoncharter.org/introduction.html (accessed on 26 July 2023).

- The Seville Principles. International Principles of Virtual Archaeology. 2017. Available online: http://smartheritage.com/seville-principles/seville-principles (accessed on 26 July 2023).

- Rocha, G.; Mateus, L.; Fernández, J.; Ferreira, V. A Scan-to-BIM Methodology Applied to Heritage Buildings. Heritage 2020, 3, 47–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BuildingSMART. Industry Foundation Classes (IFC). Available online: https://buildingsmart.org/standards/%20bsi-standards/industry-foundation-classes/ (accessed on 26 July 2023).

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:52020DC0662&rid=5 (accessed on 26 July 2023).

- Jiang, R.; Wu, C.; Lei, X.; Shemery, A.; Hampson, K.; Wu, P. Government efforts and roadmaps for building information modeling implementation: Lessons from Singapore, the UK and the US. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2022, 29, 782–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampaio, A.; Gomes, A. Professional One-Day Training Course in BIM: A Practice Overview of Multi-Applicability in Construction. J. Softw. Eng. Appl. 2022, 15, 131–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RAIC. Existing Conditions Modelling Fundamentals BUNDLE. Available online: https://raic.org/product/existing-conditions-modelling-fundamentals-bundle (accessed on 26 July 2023).

- Politecnico Milano 1863. HBIM Per Il Construito—Dalla Digitalizzazione Alla Gestione. Available online: https://www.mantovalab.polimi.it/masterhbim_2ed/ (accessed on 26 July 2023).

- UEL, University of Padua. HBIM—Short Specialization Degree in Digitalization, Planning and Management of Architectural and Infrastructural Heritage. Available online: https://uel.unipd.it/en/masters/hbim-short-specialization-degree-in-digitalization-planning-and-management-of-architectural-and-infrastructural-heritage/ (accessed on 26 July 2023).

- Sapienza, Università di Roma. Heritage Building Information Modeling (HBIM). Available online: https://www.uniroma1.it/en/offerta-formativa/master/2022/heritage-building-information-modeling-hbim (accessed on 26 July 2023).

- Evrard, Y. Democratizing Culture or Cultural Democracy? J. Arts Manag. Law Soc. 2010, 27, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pybus, C.; Graham, K.; Doherty, J.; Arellano, N.; Fai, S. New Realities for Canada’s Parliament: A Workflow for Preparing Heritage BIM for Game Engines and Virtual Reality. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2019, XLII–2/W15, 945–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HBIM—Basics. Available online: https://ipti.pt/course/hbim-basics/ (accessed on 26 July 2023).

- Sacramento, M. Noticia da Fundação do Convento da Madre de Deos das Religiozas Descalças de Lisboa, da Primeira Regra de Nossa Madre Santa Clara e de Alguas Couzas das Vidas e Mortes de Muitas Madres Santas…Escritas por hua Freira do Mesmo Convento no Anno de 1639. 1639. Available online: https://purl.pt/31162 (accessed on 26 July 2023).

- Pacheco, M.; Quando as Freiras Faziam História: Crônicas Conventuais, Autoria Feminina e Poder em Portugal no Século XVII. ANPUH—XXV Simpósio Nacional de História—Fortaleza 2009; pp. 1–10. Available online: http://www.encontro2014.rj.anpuh.org/resources/anais/anpuhnacional/S.25/ANPUH.S25.1248.pdf (accessed on 26 July 2023).

- Anonymous. Chegada das Relíquias de Santa Auta à Igreja da Madre de Deus; c. 1522; National Museum of Ancient Art: Lisbon, Portugal. (slide 2/5). Available online: http://www.matriznet.dgpc.pt/MatrizNet/Objectos/ObjectosConsultar.aspx?IdReg=248631 (accessed on 27 July 2023).

- Anonymous. S. Francisco Entregando os Estatutos da Ordem a Santa Clara; 1515; National Museum of Ancient Art: Lisbon, Portugal, 1515. Available online: http://www.matriznet.dgpc.pt/MatrizNet/Objectos/ObjectosConsultar.aspx?IdReg=280211 (accessed on 27 July 2023).

- Afonso, J. Políptico do Convento da Madre de Deus; 1515; National Museum of Ancient Art: Lisbon, Portugal. Available online: https://pt.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pol%C3%ADptico_do_Convento_da_Madre_de_Deus (accessed on 27 July 2023).

- van der Weyden, G. Tríptico da Apresentação do Menino no Templo; c. 1501–1525; National Museum of Ancient Art: Lisbon, Portugal. Available online: http://www.matriznet.dgpc.pt/MatrizNet/Objectos/ObjectosConsultar.aspx?IdReg=247072 (accessed on 27 July 2023).

- Anonymous. Contrato celebrado entre D. Joana de Ataíde e os pedreiros Rodrigo Afonso e Pêro de Bruges para a obra de arquitectura da Igreja do Mosteiro de Nossa Senhora da Rosa, à Mouraria, 1517. Cited by: Carvalho, M.J.V. Imagens Milagrosas. In Igreja Da Madre De Deus: História, Conservação e Restauro; Mesquita, V., Pessoa, J., Eds.; Instituto Português de Conservação e Restauro: Lisboa, Portugal, 2002; p. 76. [Google Scholar]

- Nepomuceno, J.M. Floorplans, Elevations and Sections; Library and Historical Archive of the Ministry of Social Equipment Library and Historical Archive of the Ministry of Social Equipment: Lisbon, Portugal, 1871. [Google Scholar]

- Direção-Geral do Património Cultural—DGPC (Forte de Sacavém, Lisboa, Portugal). Historic photographs of the National Tile Museum’s Arab Room (FOTO. 00511169.jpg) and Main Cloister (FOTO.00511322.jpg), n.d. (Archive photos). Unpublished materials, 1941.

- Stoop, D. Vista do Convento da Madre de Deus; City Museum: Lisbon, Portugal, 1662. [Google Scholar]

- Tile Panel of the Primitive Church of Madre de Deus Seen from the South. Consistory Room, Church of the Third Order of São Francisco, São Salvador, Baía, Brazil, c. 18th-Century. (Tile Painting by Unknown Author). Available online: https://pt.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ficheiro:Igreja_da_Ordem_Terceira_de_S%C3%A3o_Francisco_Salvador_Consist%C3%B3rio_Azulejos-0478.jpg (accessed on 28 August 2023).

- Gabriel, B. Large Panorama of Lisbon; National Tile Museum: Lisbon, Portugal, 1700. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, L.G. N.S. Madre Deos. Descripção dos Monumentos Sacros de Lisboa, ou Collecção de Todos os Conventos, Mosteiros, e Parrochiaes no Recinto da Cidade de Lisboa em 1833; p. 238. In: Codex nº215 of the Collection of Manuscripts of the National Library of Lisbon, Lisbon, 1840. Available online: https://purl.pt/28588 (accessed on 27 June 2023).

- Lima, B. Convento da Madre de Deus. In Archivo Pittoresco: Semanário illustrado; Castro Irmão & Co: Lisboa, Portugal, 1868; p. 333. Available online: https://hemerotecadigital.cm-lisboa.pt/periodicos/arquivop/1862/TomoV/N42/N42_master/ArquivoPitoresco1862N42.PDF (accessed on 27 June 2023).

- Rocha, R.M.R. Reconstrução e Automação em Fluxos de Trabalho HBIM. Master’s Thesis, Instituto Superior Técnico, Lisbon University, Lisbon, Portugal, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Amaral, M.A.C.A. Relatório do Acompanhamento Arqueológico da Fase de Execução do Projecto de Requalificação da Sala D. Manuel Museu Nacional Do Azulejo; Archaeological Report; Governo de Portugal Secretária de Estado da Cultura & Direção Geral do Património Cultural: Lisboa, Portugal, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Guimarães, J.R. O Mosteiro da Madre de Deus. In Artes & Letras; Series 3; Rolland & Semiond Editores: Lisboa, Portugal, 1874; p. 71. [Google Scholar]

- Pais, A.; Curvelo, A. Memórias da Fogueira o Primativo Mosteiro da Madre de Deus. In Casa Perfeitíssima 500 Anos da Fundação do Mosteiro da Madre de Deus 1509–2009; Museu Nacional do Azulejo: Lisboa, Portugal, 2009; pp. 75–83. [Google Scholar]

- Simões, J.M. O Modelo Arquitectónico das Duas Primeiras Casas Coletinas Portuguesas: Os Mosteiros de Jesus de Setúbal e da Madre de Deus de Xabregas. In Casa Perfeitíssima 500 Anos da Fundação do Mosteiro da Madre de Deus 1509–2009; Museu Nacional do Azulejo: Lisboa, Portugal, 2009; pp. 65–74. [Google Scholar]

- Mesquita, V.; Pessoa, J. Igreja da Madre de Deus: História, Conservação e Restauro; Instituto Português de Conservação e Restauro: Lisboa, Portugal, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Unknown Artist. Persian Carpet (Large Fragment). National Museum of Ancient Art, Lisbon. Available online: http://www.matriznet.dgpc.pt/MatrizNet/Objectos/ObjectosConsultar.aspx?IdReg=246122 (accessed on 27 July 2023).

- Silberman, N. Chasing the Unicorn? The Quest for “Essence”. In Digital Heritage New Heritage New Media and Cultural Heritage; Kalay, Y.E., Kvan, T., Affleck, J., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 81–91. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rafeiro, J.; Tomé, A. Finding the Lost 16th-Century Monastery of Madre de Deus: A Pedagogical Approach to Virtual Reconstruction Research. Heritage 2023, 6, 6213-6239. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage6090326

Rafeiro J, Tomé A. Finding the Lost 16th-Century Monastery of Madre de Deus: A Pedagogical Approach to Virtual Reconstruction Research. Heritage. 2023; 6(9):6213-6239. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage6090326

Chicago/Turabian StyleRafeiro, Jesse, and Ana Tomé. 2023. "Finding the Lost 16th-Century Monastery of Madre de Deus: A Pedagogical Approach to Virtual Reconstruction Research" Heritage 6, no. 9: 6213-6239. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage6090326

APA StyleRafeiro, J., & Tomé, A. (2023). Finding the Lost 16th-Century Monastery of Madre de Deus: A Pedagogical Approach to Virtual Reconstruction Research. Heritage, 6(9), 6213-6239. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage6090326