To Replicate, or Not to Replicate? The Creation, Use, and Dissemination of 3D Models of Human Remains: A Case Study from Portugal

Abstract

1. Introduction

The Digitalization and Creation of 3D Replicas of Human Remains

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Survey

- Part 1: addressed participants’ engagement with visualization and creation of 3D digital replicas of human bones

- Part 2: addressed participants’ opinions on the creation, use, and dissemination of 3D models of human skeletal remains

- Part 3: collected demographic information, e.g., gender, age, education, occupation (here a reference to a professional occupation), relation religion (since this may affect how one treats and perceives the body, and bodily remains), and citizenship, to profile the survey participants. The participants’ anonymity was guaranteed.

2.2. Statistical Analysis

2.3. Social Media Comments

3. Results

3.1. Participants’ Demographical Profile

- Citizenship results. Most participants were Portuguese (n = 280, 95%). Additional citizenships included Brazilian (n = 12, 4%); two (1%) Spanish; and one (0.3%) Belgium. Nineteen participants had more than one citizenship: 10 European (two identified their second citizenship as Portuguese); five Brazilians, three Africans; and one American. Seventeen individuals did not disclose their citizenship.

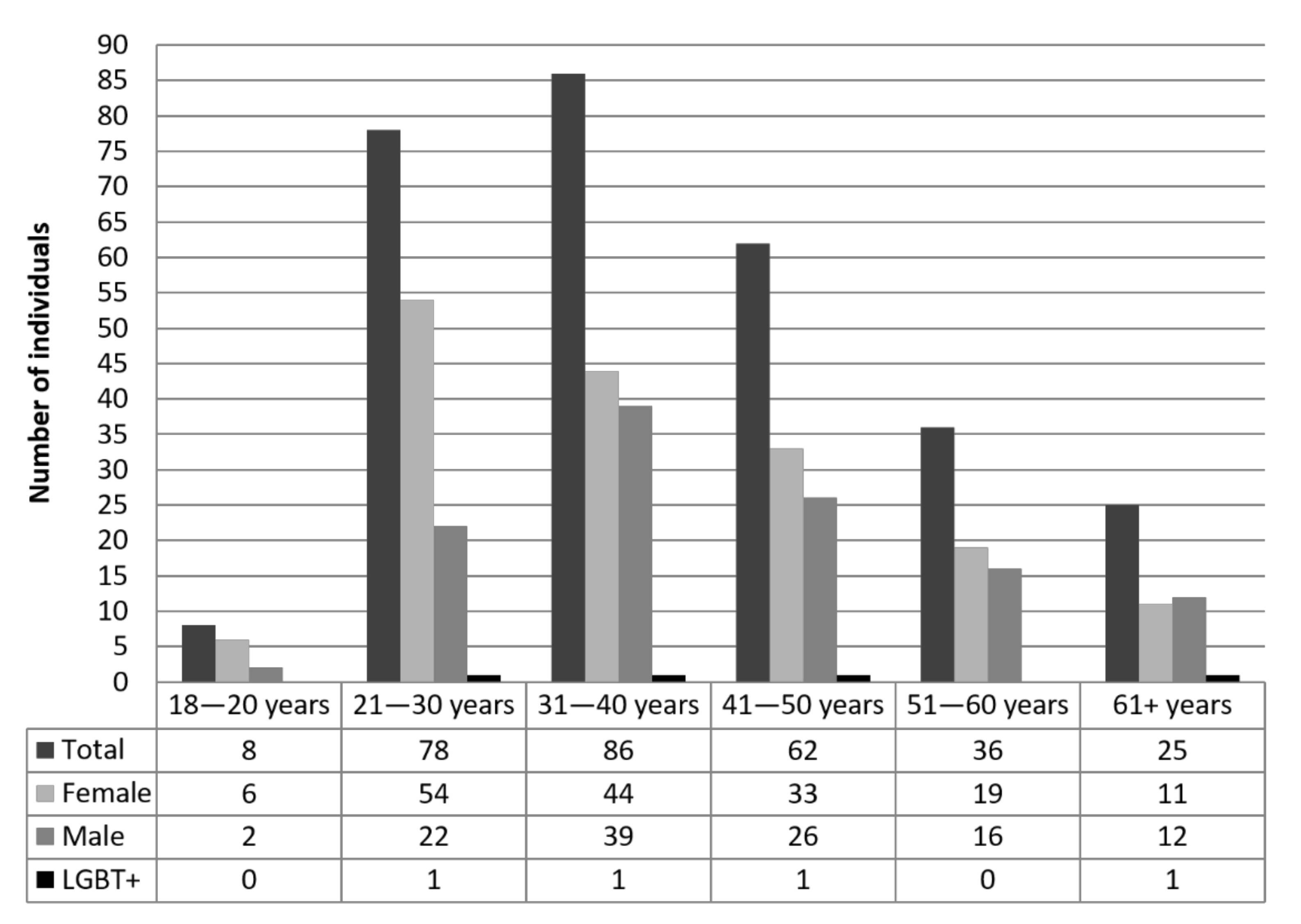

- Gender results. Three hundred participants disclosed their gender information on the survey. Most individuals identified themselves as feminine (n = 172, 57%), with the second-largest number of participants identifying themselves as male (n = 122, 41%). A smaller percentage of individuals ascribed their gender as LGBT+ (n = 6, 2%). LGBT+ participants identified themselves as queer (n = 1), male transgender (n = 2), and “Other” (n = 3).

- Age results. Only 295 participants stated their age at the time of the survey, with seven individuals reporting only their age but not their gender. The age distribution of participants can be found in Figure 1. Participants were between 18 and 75 years old and, on average, had 39 ± 13.10 years old (median age = 38 years). Age descriptions per gender are represented in Table 1.

- Educational results. Most participants had a higher education degree (n = 261, 85%-bachelor’s or undergraduate degree: n = 83, 27%; post-graduation or master’s degree: n = 125, 41%; doctorate degree: n = 53, 17%). Age distribution for individuals with a higher education diploma: mean = 39 ± 12.73 years; median = 38 years; minimum = 20 years; maximum = 75 years. Only 45 (15%) participants had a high school diploma or lower (elementary graduate: n = 4, 1%; high school graduate or equivalent: n = 41, 130%). Age distribution for high school diploma or lower: mean = 39 ± 15.13 years; median = 40 years; minimum = 18 years; maximum = 69 years. Discrimination of participants’ academic degree per gender can be found in Table 2. Six participants did not disclose their academic degree. Eleven participants did not reveal their gender and twelve their age but disclosed their academic degree.

- Religious results. One hundred and ninety-five participants (69%) did not follow a religion, with 58% females (n = 110), 39% males (n = 75) and 3% LGBT+ (n = 5). On average, the participants without a religious belief were 38 ± 12.85 years (median = 37 years; minimum age = 18 years; maximum age = 75 years). For the non-religious participants, 15.98% (n = 31) had a high school diploma or lower and 84% (n = 163) a higher education diploma.

- Occupation results. Twenty-nine participants did not give information on occupation, and 89 did not specify their profession properly; consequently, they were not allocated to occupational groups. The specialist group was composed of 109 participants (56%). The majority were female (n = 68; 63%). Thirty-seven were male (34%) and 3 were LGBT+ (3%). The specialist group’s mean age was 34 ± 12.10 years (18–70 years; median age = 32 years). The majority were non-religious (n = 71; 70%), while only 30 (30%) followed a religion. The non-specialist group was composed by 85 individuals (44%), with a similar percentage for females (n = 41, 50%) and males (n = 40; 49%). Only one individual (1%) identified themselves as LGBT+. Non-specialists were 21 to 75 years (mean age = 40 ± 12.78 years; median age = 39 years). Most non-specialists were non-religious (n = 49; 62%), while 30 non-specialists (38%) followed a religion.

3.2. Results PART 1: Visualization of Three-Dimensional Models of Skeletal Remains

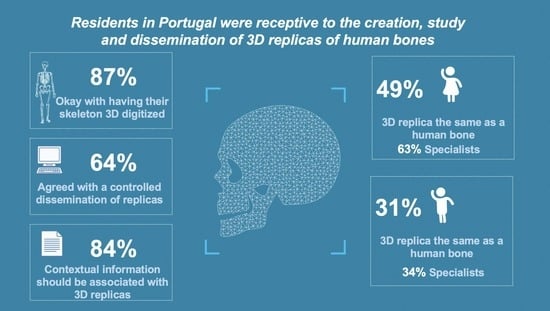

3.3. PART 2: Opinion of Portugal Residents over the Creation, Use, and Sharing of Three-Dimensional Models Online

3.4. Social Media Comments

4. Discussion

4.1. PART 1: Visualization of Three-Dimensional Models of Skeletal Remains

4.1.1. Viewing 3D Models

4.1.2. Creating and Sharing 3D Models

4.1.3. Temporal Distance and Empathy

4.2. PART 2: Opinion of Portugal Residents over the Creation, Use, and Sharing of Three-Dimensional Models Online

4.2.1. The Status of the Three-Dimensional Replicas Compared to Human Bones: An Object or a Bone?

4.2.2. Three-Dimensional Replicas: Display and Dissemination

4.2.3. Contextualization of 3D Data

4.3. Ethical Consideration of the Creation, Study, and Dissemination of Three-Dimensional Replicas of Human Bones

Commercialization of 3D Models

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ioannides, M.; Fink, E.; Cantoni, L.; Champion, E. (Eds.) Digital Heritage: Progress in Cultural Heritage. Documentation, Preservation, and Protection5th International Conference, EuroMed 2014, Limassol, Cyprus, November 3–8, 2014, Proceedings; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Spena, T.R.; Bifulco, F. (Eds.) Digital Transformation in the Cultural Heritage Sector: Challenges to Marketing in the New Digital Era; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Skublewska-Paszkowska, M.; Milosz, M.; Powroznik, P.; Lukasik, E. 3D technologies for intangible cultural heritage preservation—literature review for selected databases. Herit. Sci. 2022, 10, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Commission. Shaping Europe’s Digital Future. 2019. Available online: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/news/eu-member-states-sign-cooperate-digitising-cultural-heritage (accessed on 21 April 2022).

- Li, J.; Nie, L.; Li, Z.; Lin, L.; Tang, L.; Ouyang, J. Maximizing Modern Distribution of Complex Anatomical Spatial Information: 3D Reconstruction and Rapid Prototype Production of Anatomical Corrosion Casts of Human Specimens. Anat. Sci. Educ. 2012, 5, 330–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, K.H.; Loo, Z.Y.; Goldie, S.J.; Adams, J.W.; McMenamin, P.G. Use of 3D Printed Models in Medical Education: A Randomized Control Trial Comparing 3D Prints Versus Cadaveric Materials for Learning External Cardiac Anatomy. Anat. Sci. Educ. 2016, 9, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMenamin, P.A.; Quayle, M.R.; McHenry, C.R.; Adams, J.W. The Production of Anatomical Teaching Resources Using Three-Dimensional (3D) Printing Technology. Anat. Sci. Educ. 2014, 7, 479–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hung, C.; Shen, P.; Wu, J.; Cheng, Y.; Chen, W.; Lee, S.; Yeh, T. Association between 3D Printing-Assisted Pelvic or Acetabular Fracture Surgery and the Length of Hospital Stay in Nongeriatric Male Adults. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornejo, J.; Cornejo-Aguilar, J.A.; Vargas, M.; Helguero, C.G.; Milanezi de Andrade, R.; Torres-Montoya, S.; Asensio-Salazar, J.; Rivero Calle, A.; Martínez Santos, J.; Damon, A.; et al. Anatomical Engineering and 3D Printing for Surgery and Medical Devices: International Review and Future Exponential Innovations. BioMed Res. Int. 2022, 2022, 6797745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Squires, K.; Errickson, D.; Márquez-Grant, N. (Eds.) Ethical Approaches to Human Remains; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Swain, H. Museum practice and the display of human remains. In Archaeologists and the Dead: Mortuary Archaeology in Contemporary Society; Williams, H., Giles, M., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016; pp. 169–183. [Google Scholar]

- Giesen, M.J. (Ed.) Curating Human Remains: Caring for the Dead in the United Kingdom; Boydell Press: Oxfrod, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher, A.; Antoine, D.; Hill, J. Regarding the Dead: Human Remains in the British Museum; British Museum: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Errickson, D.; Thompson, T. Sharing is not always caring: Social media and the dead. In Ethical Approaches to Human Remains; Squires, K., Errickson, D., Márquez-Grant, N., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 299–313. [Google Scholar]

- Meyers, E.K.; Killgrove, K. Bones, Bodies, and Blogs: Outreach and Engagement in Bioarchaeology. Internet Archaeol. 2015, 39, 935–940. Available online: http://intarch.ac.uk/journal/issue39/5/emerykillgrove.html (accessed on 4 June 2022). [CrossRef]

- Thompson, T.; Errickson, D. (Eds.) Human Remains: Another Dimension: The Application of Imaging to the Study of Human Remains; Academic Press: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sumner, A.; Riddle, A. Remote Anthropology: Reconciling Research Priorities with Digital Data Sharing. J. Anthropol. Sci. 2009, 87, 219–221. [Google Scholar]

- Bowron, E.L. A new approach to the storage of human skeletal remains. Conservator 2003, 27, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves-Cardoso, F.; Campanacho, V. The Scientific Profiles of Documented Collections via Publication Data: Past, Present, and Future Directions in Forensic Anthropology. Forensic. Sci. 2022, 2, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, C.; Alves-Cardoso, F. (Eds.) Identified Skeletal Collections: The Testing Ground of Anthropology? Archaeopress: Oxford, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, C.A. Ethical and practical challenges of working with archaeological human remains, with a focus on the UK. In Ethical Approaches to Human Remains; Squires, K., Errickson, D., Márquez-Grant, N., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 133–155. [Google Scholar]

- Schug, G.R.; Killgrove, K.; Atkin, A.; Barona, K. 3D Dead: Ethical Considerations in Digital Human Osteology. Bioarchaeol. Int. 2021, 4, 217–230. [Google Scholar]

- Thomson, K.; Williams, A. Virtual anatomy teaching aids. In Forensic Science Education and Training a Tool-kit for Lecturers and Practitioner Trainers; Williams, A., Cassella, J.P., Maskell, P.D., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 137–146. [Google Scholar]

- Marques, C.; Matos, V.; Costa, T.; Zink, A.; Cunha, E. Absence of evidence or evidence of absence? A discussion on paleoepidemiology of neoplasms with contributions from two Portuguese human skeletal reference collections (19th–20th century). Int. J. Paleopathol. 2018, 21, 83–95. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jones, D.G. Three-dimensional Printing in Anatomy Education: Assessing Potential Ethical Dimensions. Anat. Sci. Educ. 2019, 12, 435–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, D.G. The ethical awakening of human anatomy: Reassessing the past and envisioning a more ethical future. In Ethical Approaches to Human Remains; Squires, K., Errickson, D., Márquez-Grant, N., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 73–94. [Google Scholar]

- Alves-Cardoso, F. “Not of One’s Body”: The Creation of Identified Skeletal Collections with Portuguese Human Remains. In Ethical Approaches to Human Remains; Squires, K., Errickson, D., Márquez-Grant, N., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 503–518. [Google Scholar]

- Campanacho, V.; Alves-Cardoso, F. E se Fossem os Seus Ossos? Gostaria de os Ver Produzidos em 3D, e Visualizados Online? A opinião dos Portugueses. Arqueozine. 2019. Available online: https://arqueozine.com/2019/03/31/e-se-fossem-os-seus-ossos-gostaria-de-os-ver-produzidos-em-3d-e-visualizados-online-a-opiniao-dos-portugueses/ (accessed on 31 March 2019).

- Márquez-Grant, N.; Errickson, D. Ethical Considerations: An Added Dimension. In Human Remains: Another Dimension the Application of Imaging to the Study of Human Remains; Errickson, D., Thompson, T., Eds.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2017; pp. 193–204. [Google Scholar]

- BABAO. BABAO recommendations on the ethical issues surrounding 2D and 3D digital imaging of human remains. 2019. Available online: https://www.babao.org.uk/publications/ethics-and-standards/ (accessed on 21 April 2022).

- Bauer, M.W.; Howard, S. Modern Portugal and Its Science Culture—Regional and Generational Comparisons; Ciencia Viva: Lisbon, Portugal, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gonçalves, M.E.; Castro, P. Science, culture and policy in Portugal: A triangle of changing relationships? PJSS 2003, 1, 157–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granado, A.; Malheiros, J.V. Cultura Científica em Portugal: Ferramentas Para Perceber o Mundo e Aprender a Mudá-lo; Fundação Francisco Manuel dos Santos: Lisboa, Portugal, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Campanacho, V. The influence of skeletal size on age-related criteria from the pelvic joints in Portuguese and North American samples. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Sheffield, Sheffield, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Godinho, R.M.; Oliveira-Santos, I.; Pereira, M.F.C.; Maurício, A.; Valera, A.; Gonçalves, D. Is enamel the only reliable hard tissue for sex metric estimation of burned skeletal remains in biological anthropology? J. Archaeol. Sci. 2019, 26, 101876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godinho, R.M.; Fitton, L.C.; Toro-Ibacache, V.; Stringer, C.B.; Lacruz, R.S.; Bromage, T.G.; O’Higgins, P. The biting performance of Homo sapiens and Homo heidelbergensis. J. Hum. Evol. 2018, 118, 56–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, J.; Almiro, P.A.; Nunes, T.; Kato, R.; Garib, D.; Miguéis, A.; Corte-Real, A. Sex and age biological variation of the mandible in a Portuguese population- a forensic and medico-legal approaches with three-dimensional analysis. Sci. Justice 2021, 61, 704–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Tamayo, N.; Román, C. Virtual anthropology available for everyone: The importance of open resources during and beyond COVID-19 pandemic. Am. J. Biol. Anthrop. 2021, 174, 1–123. [Google Scholar]

- Hennessy, C.; Royer, D.F.; Meyer, A.J.; Smith, C.F. Social Media Guidelines for Anatomists. Anat. Sci. Educ. 2020, 13, 527–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, H.; Atkin, A. Virtually Dead: Digital Public Mortuary Archaeology. Internet Archaeol. 2015, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzortzi, K. Human remains, museum space and the ‘poetics of exhibiting’. Univ. Mus. Coll. J. 2018, 10, 23–34. [Google Scholar]

- Alberti, S.J.M.M.; Bienkowski, P.; Chapman, M.J.; Drew, R. Should we display the dead? Mus. Soc. 2009, 7, 133–149. [Google Scholar]

- D’Andrea, A.; Conyers, M.; Courtney, K.K.; Finch, E.; Levine, M.; Rountrey, A.; Kettler, H.S.; Webbink, K. Copyright and Legal Issues Surrounding 3D Data. In 3D Data Creation to Curation: Community Standards for 3D Data Preservation; Moore, J., Ed.; Association of Research and College Libraries (ALA): Chicago, IL, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, S.E.; Hirst, C.S. 3D Data in Human Remains Disciplines: The Ethical Challenges. In Ethical Approaches to Human Remains; Squires, K., Errickson, D., Márquez-Grant, N., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 315–346. [Google Scholar]

- Ulguim, P. Models and Metadata: The Ethics of Sharing Bioarchaeological 3D Models Online. Archaeol. J. World Archaeol. Congr. 2018, 14, 189–228. [Google Scholar]

- Friess, M. Scratching the Surface? The use of surface scanning in physical and paleoanthropology. J. Anthropol. Res. 2012, 90, 7–31. [Google Scholar]

- Campanacho, V. 3D Scanning Guidelines for Skeletal Remains with Artec Studio 11 at the University of Sheffield. 2017. Available online: https://sites.google.com/site/vanessacampanacho/resources (accessed on 20 April 2022).

- Veneziano, A.; Landi, F.; Profico, A. Surface smoothing, decimation, and their effects on 3D biological specimens. Am. J. Phy. Anthrop. 2018, 166, 473–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzminsky, S.; Gardiner, M. Three-Dimensional Laser Scanning: Potential Uses for Museum Conservation and Scientific Research. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2012, 39, 2744–2751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, M.D.; Dumontier, M.; Aalbersberg, I.; Appleton, G.; Axton, M.; Baak, A.; Blomberg, N.; Boiten, J.; Silva Santos, L.B.; Bourne, P.E.; et al. The FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data management and stewardship. Sci. Data 2016, 3, 160018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, M.D.; Sansone, S.A.; Schultes, E.; Doorn, P.; Bonino da Silva Santos, L.O.; Dumontier, M. A design framework and exemplar metrics for FAIRness. Sci. Data 2018, 5, 180118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decker, S.; Ford, J. Management of 3D Image Data. In Human Remains: Another Dimension the Application of Imaging to the Study of Human Remains; Errickson, D., Thompson, T., Eds.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2017; pp. 185–191. [Google Scholar]

- Wild, S.; 3D printing and the murky ethics of replicating bones. Undark Magazine. 2020. Available online: https://undark.org/2020/01/10/3dbone-prints-south-africa/ (accessed on 21 April 2022).

- Ulguim, P. Digital Remains Made Public: Sharing the Dead Online and our Future Digital Mortuary Landscape. AP Online J. Public Archaeol. 2018, 3, 153–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasset, B.R. Which Bone to Pick: Creation, Curation, and Dissemination of Online 3D Digital Bioarchaeological Data. Archaeol. J. World Archaeol. Congr. 2018, 14, 231–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Errickson, D.; Thompson, T.J.U.; Rankin, B.W.J. The Application of 3D Visualization of Osteological Trauma for the Courtroom: A Critical Review. J. Forensic Radiol. Imaging 2014, 2, 132–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Errickson, D.; Grueso, I.; Griffith, S.J.; Setchell, J.M.; Thompson, T.J.U.; Thompson, C.E.L.; Gowland, R. Towards best practice for the use of active non-contact surface scanning to record human skeletal remains from archaeological contexts. Int. J. Osteoarch. 2017, 27, 650–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younan, S.; Treadaway, C. Digital 3D Models of Heritage Artefacts: Towards a Digital Dream Space. Digit. Appl. Archaeol. Cult. Heritage 2015, 2, 240–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilmister, H. Visitor Perceptions of Ancient Egyptian Human Remains in Three United Kingdom Museums. Pap. Inst. Archaeol. 2003, 14, 57–69. [Google Scholar]

- International Council of Museums (ICOM). Code of Ethics. 2004. Available online: http://icom.museum/fileadmin/user_upload/pdf/Codes/code_ethics2013_eng.pdf (accessed on 14 April 2014).

- Gazi, A. Exhibition Ethics—An Overview of Major Issues. J. Conserv. Mus. Stud. 2014, 12, Art 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, M.M.; Rumsey, C. The body in the museum. In Human Remains: Guide for Museums and Academic Institutions; Cassman, V., Odegaard, N., Powell, J., Eds.; Altamira Press: Lanham, MD, USA, 2007; pp. 261–289. [Google Scholar]

- Harries, J.; Fibiger, L.; Smith, J.; Adler, T.; Szöke, A. Exposure: The ethics of making, sharing and displaying photographs of human remains. Hum. Remain. Violence 2018, 4, 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Freeman, E.P. Public Opinion: Social Attitudes. In International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Wright, J.D., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 562–568. [Google Scholar]

- Alfonso, M.P.; Powell, J. Ethics of Flesh and Bone, or Ethics in the Practice of Paleopathology, Osteology, and Bioarchaeology. In Human Remains: Guide for Museums and Academic Institutions; Cassman, V., Odegaard, N., Powell, J., Eds.; Altamira Press: Lanham, MD, USA, 2007; pp. 5–19. [Google Scholar]

- Boyer, D.; Gunnell, G.; Kaufman, S.; McGeary, T. MorphoSource: Archivingand sharing 3-D digital specimen data. Paleontol. Soc. Pap. 2016, 22, 157–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassett, B.R.; Rando, C.; Bocaege, E.; Durruty, M.A.; Hirst, C.; Smith, S.; Ulguim, P.F.; White, S.; Wilson, A. Transcript of WAC 8 Digital Bioarchaeological Ethics Panel Discussion, 29 August 2016 and Resolution on Ethical Use of Digital Bioarchaeological Data. Archaeol. J. World Archaeol. Congr. 2018, 14, 317–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkin, A. Digging up the digital dead: Best practice for future(istic) osteoarchaeology. 2015. Available online: https://deathsplaining.wordpress.com/2015/10/02/digging-up-the-digital-dead-bestpractice-for-futureistic-osteoarchaeology/ (accessed on 21 April 2022).

- Killgrove, K. How 3D printed bones are revolutionizing forensics and bioarchaeology. 2015. Available online: http://www.forbes.com/sites/kristinakillgrove/2015/05/28/how-3d-printed-bones-are-revolutionizing-forensics-and-bioarchaeology/ (accessed on 21 April 2022).

- Graham, S.; Huffer, D.; Simons, J. When TikTok Discovered the Human Remains Trade: A Case Study. Open Archaeol. 2022, 8, 196–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halling, C.L.; Seidemann, R.M. They Sell Skulls Online?! A Review of Internet Sales of Human Skulls on eBay and the Laws in Place to Restrict Sales. J. Forensic. Sci. 2016, 61, 1322–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huffer, D.; Charlton, N. Serious enquiries only, please: Ethical issues raised by the online human remains trade. In Ethical Approaches to Human Remains; Squires, K., Errickson, D., Márquez-Grant, N., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 95–129. [Google Scholar]

- Huffer, D.; Chappell, D.; Charlton, N.; Spatola, B.F. Bones of Contention: The Online Trade in Archaeological, Ethnographic and Anatomical Human Remains on Social Media Platforms. In The Palgrave Handbook on Art Crime; Hufnagel, S., Chappell, D., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2019; pp. 527–556. [Google Scholar]

: 100% was not attributed since participants could choose more than one option; N = frequency; % = percentage; SD = standard deviation. Questions 2 to 5 were only responded to by participants that had seen a 3D model of human remains (i.e., replied YES to question 1).

: 100% was not attributed since participants could choose more than one option; N = frequency; % = percentage; SD = standard deviation. Questions 2 to 5 were only responded to by participants that had seen a 3D model of human remains (i.e., replied YES to question 1).

: 100% was not attributed since participants could choose more than one option; N = frequency; % = percentage; SD = standard deviation. Questions 2 to 5 were only responded to by participants that had seen a 3D model of human remains (i.e., replied YES to question 1).

: 100% was not attributed since participants could choose more than one option; N = frequency; % = percentage; SD = standard deviation. Questions 2 to 5 were only responded to by participants that had seen a 3D model of human remains (i.e., replied YES to question 1).

: 100% was not attributed since participants could choose more than one option; N = frequency; % = percentage; SD = standard deviation.

: 100% was not attributed since participants could choose more than one option; N = frequency; % = percentage; SD = standard deviation.

: 100% was not attributed since participants could choose more than one option; N = frequency; % = percentage; SD = standard deviation.

: 100% was not attributed since participants could choose more than one option; N = frequency; % = percentage; SD = standard deviation.

| Gender | N | Mean | SD | Median | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 167 | 38 | 12.96 | 36 | 18 | 70 |

| Male | 117 | 42 | 12.94 | 40 | 19 | 75 |

| LGBT+ | 4 | 42 | 17.35 | 39 | 25 | 65 |

| Gender | High School Diploma or Lower | Higher Education Degree | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | |

| Female | 20 | 45 | 151 | 60 |

| Male | 23 | 52 | 95 | 37 |

| LGBT+ | 1 | 3 | 5 | 1 |

| Group | Question | χ2 | df | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Have you ever seen a 3D model of human skeletal remains online? | 13.845 | 2 | <0.001 |

| Have you ever created a 3D digital model of human skeletal remains? | 1.141 | 1 | 0.285 | |

| Have you ever shared a 3D digital model of human skeletal remains online (e.g., repository, news article, institutional website)? | 2.968 | 1 | 0.085 | |

| Education | Have you ever seen a 3D model of human skeletal remains online? | 0.419 | 2 | 0.811 |

| Have you ever created a 3D digital model of human skeletal remains? | 0.006 | 1 | 0.937 | |

| Have you ever shared a 3D digital model of human skeletal remains online (e.g., repository, news article, institutional website)? | 3.423 | 1 | 0.064 | |

| Occupation | Have you ever seen a 3D model of human skeletal remains online? | 18.427 | 2 | <0.001 |

| Have you ever created a 3D digital model of human skeletal remains? | 1.342 | 1 | 0.247 | |

| Have you ever shared a 3D digital model of human skeletal remains online (e.g., repository, news article, institutional website)? | 0.238 | 1 | 0.626 | |

| Religion | Have you ever seen a 3D model of human skeletal remains online? | 0.284 | 2 | 0.868 |

| Have you ever created a 3D digital model of human skeletal remains? | 0.304 | 1 | 0.582 | |

| Have you ever shared a 3D digital model of human skeletal remains online (e.g., repository, news article, institutional website)? | 0.062 | 1 | 0.804 |

| Question and Options | Age (Years) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean | SD | Median | Min | Max | |

| 1-Have you ever seen a 3D model of human skeletal remains online? |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Yes | 122 | 38 | 12.99 | 36 | 18 | 75 |

| No, I have only seen two-dimension (2D) pictures of human bones online | 115 | 40 | 13.24 | 39 | 20 | 70 |

| No, I have never seen 2D or 3D images of human bones online | 58 | 42 | 12.85 | 40 | 20 | 69 |

| 2-Have you ever created a 3D digital model of human skeletal remains? |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Yes | 11 | 33 | 6.69 | 33 | 22 | 41 |

| No | 108 | 38 | 13.10 | 36 | 18 | 75 |

| 3-Have you ever shared a 3D digital model of human skeletal remains online (e.g., repository, news article, institutional website)? |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Yes | 25 | 39 | 13.00 | 36 | 21 | 62 |

| No | 96 | 37 | 12.71 | 36 | 18 | 75 |

| 4-In which online source have you seen and/or shared a model of human skeletal remains? * |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| News website | 24 | 42 | 12.54 | 39 | 24 | 70 |

| Social media (e.g., Facebook, Twitter) | 36 | 38 | 9.81 | 37 | 21 | 58 |

| Museum website | 43 | 40 | 14.17 | 37 | 20 | 75 |

| University and/or research centre website | 47 | 36 | 11.32 | 36 | 18 | 67 |

| 3D model online repository (e.g., SketchFab, Morphosource) | 45 | 34 | 9.91 | 32 | 19 | 62 |

| Not listed | 11 | 38 | 13.28 | 39 | 21 | 67 |

| 5-Which 3D images of skeletal remains did you see and/or share online? * |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Human skeletal remains of individual(s) that have passed away more than 100 years ago | 67 | 39 | 13.10 | 37 | 18 | 70 |

| Unknown human skeletal remains of individual(s) that have passed away less than 100 years ago | 24 | 36 | 10.60 | 35 | 18 | 62 |

| Identified human skeletal remains of individual(s) that have passed away less than 100 years ago without disclosing identity. By known identity we mean that the name, age and sex is available | 17 | 32 | 8.45 | 32 | 18 | 44 |

| Identified human skeletal remains of individual(s) that have passed away less than 100 years ago with disclosed identity | 3 | 38 | 17.62 | 33 | 24 | 58 |

| I do not recall | 35 | 37 | 12.54 | 33 | 20 | 75 |

: 100% was not attributed since participants could choose more than one option; N frequency; % = percentage; SD = standard deviation; Min = minimum age; Max = maximum age. Questions 2 to 5 were only responded to by participants that have seen a 3D model of human remains (i.e., replied YES to question 1).

: 100% was not attributed since participants could choose more than one option; N frequency; % = percentage; SD = standard deviation; Min = minimum age; Max = maximum age. Questions 2 to 5 were only responded to by participants that have seen a 3D model of human remains (i.e., replied YES to question 1).| Group | Question | χ2 | df | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Would you not be ok with your skeleton and those of family members being 3D digitized after death? | 13.845 | 2 | <0.001 |

| Should 3D digital replicas be considered as being the same as the original human bone and thus with the same ethical considerations regarding their display online? | 10.842 | 4 | 0.028 | |

| Should there be some control over how the 3D models of human bones are disseminated? | 5.946 | 1 | 0.015 | |

| Should available online digital 3D models of human bones possibly be downloaded for personal use by the greater public? | 17.543 | 4 | 0.002 | |

| Should a description/context of 3D models of human bones be always associated with the models? | 6.525 | 4 | 0.163 | |

| Education | Should 3D digital replicas be considered as being the same as the original human bone and thus with the same ethical considerations regarding their display online? | 3.236 | 4 | 0.519 |

| Should there be some control over how the 3D models of human bones are disseminated? | 3.482 | 1 | 0.062 | |

| Should available online digital 3D models of human bones possibly be downloaded for personal use by the greater public? | 6.271 | 4 | 0.180 | |

| Should a description/context of 3D models of human bones be always associated with the models? | 1.331 | 4 | 0.856 | |

| Occupation | Should 3D digital replicas be considered as being the same as the original human bone and thus with the same ethical considerations regarding their display online? | 5.202 | 4 | 0.267 |

| Should there be some control over how the 3D models of human bones are disseminated? | 0.033 | 1 | 0.856 | |

| Should available online digital 3D models of human bones possibly be downloaded for personal use by the greater public? | 2.444 | 4 | 0.655 | |

| Should a description/context of 3D models of human bones be always associated with the models? | 6.760 | 4 | 0.149 | |

| Religion | Should 3D digital replicas be considered as being the same as the original human bone and thus with the same ethical considerations regarding their display online? | 1.075 | 4 | 0.898 |

| Should there be some control over how the 3D models of human bones are disseminated? | 3.206 | 1 | 0.073 | |

| Should available online digital 3D models of human bones possibly be downloaded for personal use by the greater public? | 3.664 | 4 | 0.453 | |

| Should a description/context of 3D models of human bones be always associated with the models? | 11.113 | 4 | 0.025 |

| Question and Options | Age (Years) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean | SD | Median | Min | Max | |

| 6—Would you be ok with your skeleton and those of family members being 3D digitized after death? |  |  |  |  |  | |

| No | 36 | 43 | 14.61 | 42 | 20 | 75 |

| Yes | 257 | 39 | 12.83 | 38 | 18 | 70 |

| 7—Should 3D digital replicas be considered as being the same as the original human bone and thus with the same ethical considerations regarding their display online? |  |  |  |  |  | |

| Strongly agree | 64 | 36 | 12.83 | 35 | 20 | 69 |

| Somewhat agree | 58 | 37 | 12.75 | 37 | 18 | 70 |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 46 | 46 | 12.98 | 43 | 19 | 75 |

| Somewhat disagree | 63 | 39 | 13.43 | 40 | 20 | 70 |

| Strongly disagree | 62 | 41 | 13.03 | 38 | 20 | 69 |

| 8—Should 3D models of human remains be displayed online for: * |  |  |  |  |  | |

| The greater public for non-educational purposes | 54 | 36 | 11.72 | 36 | 18 | 69 |

| The greater public only for educational purposes | 180 | 38 | 13.30 | 37 | 18 | 75 |

| Research in anthropology, biology, anatomy and medicine | 236 | 39 | 13.04 | 38 | 18 | 70 |

| No, 3D models of human bones should never be available online | 6 | 44 | 15.53 | 42 | 20 | 64 |

| 9—In which platforms could 3D models of human bones be available? * |  |  |  |  |  | |

| News website | 36 | 41 | 13.03 | 39 | 19 | 69 |

| Social media (e.g., Facebook, Twitter) | 30 | 41 | 13.48 | 41 | 18 | 69 |

| Museum website | 178 | 40 | 13.20 | 40 | 19 | 75 |

| University and/or research centre website | 258 | 39 | 12.87 | 38 | 18 | 75 |

| 3D model online repository (e.g., SketchFab, Morphosource) | 184 | 37 | 11.96 | 36 | 18 | 75 |

| Not listed | 12 | 40 | 11.82 | 39 | 24 | 65 |

| 10—Should there be some control over how the 3D models of human bones are disseminated? |  |  |  |  |  | |

| No, digital 3D models should be freely available on any online platform | 99 | 39 | 13.45 | 39 | 18 | 75 |

| Yes, there should be a registration and login to access the 3D model online | 175 | 39 | 12.37 | 37 | 20 | 70 |

| 11—Which 3D models of skeletal remains can be available online for the greater public? * |  |  |  |  |  | |

| Human skeletal remains of individual(s) that have passed away more than 100 years ago | 212 | 38 | 12.63 | 36 | 18 | 75 |

| Unknown human skeletal remains of individual(s) that have passed away less than 100 years ago | 176 | 38 | 13.03 | 36 | 18 | 75 |

| Identified human skeletal remains of individual(s) that have passed away less than 100 years ago without disclosing identity | 186 | 38 | 12.79 | 36 | 18 | 75 |

| Identified human skeletal remains of individual(s) that have passed away less than 100 years ago with disclosed identity | 58 | 36 | 10.91 | 36 | 18 | 63 |

| 12—Should available online digital 3D models of human bones possibly be downloaded for personal use by the greater public? |  |  |  |  |  | |

| Strongly agree | 51 | 40 | 11.58 | 40 | 19 | 65 |

| Somewhat agree | 52 | 37 | 14.26 | 35 | 18 | 70 |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 30 | 40 | 12.05 | 41 | 21 | 75 |

| Somewhat disagree | 60 | 40 | 12.80 | 39 | 21 | 70 |

| Strongly disagree. The digital 3D models of human remains should only be used for research. | 83 | 38 | 12.55 | 37 | 20 | 69 |

| 13—Should a description/context of 3D models of human bones be always associated with the models? |  |  |  |  |  | |

| Strongly agree | 180 | 38 | 12.41 | 37 | 18 | 70 |

| Somewhat agree | 50 | 42 | 14.20 | 41 | 21 | 75 |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 38 | 41 | 11.78 | 40 | 21 | 65 |

| Somewhat disagree | 4 | 46 | 13.59 | 48 | 31 | 58 |

| Strongly disagree | 4 | 38 | 3.70 | 38 | 33 | 41 |

: 100% was not attributed since participants could choose more than one option; N = frequency; % = percentage; SD = standard deviation; Min = minimum age; Max = maximum age.

: 100% was not attributed since participants could choose more than one option; N = frequency; % = percentage; SD = standard deviation; Min = minimum age; Max = maximum age.Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alves-Cardoso, F.; Campanacho, V. To Replicate, or Not to Replicate? The Creation, Use, and Dissemination of 3D Models of Human Remains: A Case Study from Portugal. Heritage 2022, 5, 1637-1658. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage5030085

Alves-Cardoso F, Campanacho V. To Replicate, or Not to Replicate? The Creation, Use, and Dissemination of 3D Models of Human Remains: A Case Study from Portugal. Heritage. 2022; 5(3):1637-1658. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage5030085

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlves-Cardoso, Francisca, and Vanessa Campanacho. 2022. "To Replicate, or Not to Replicate? The Creation, Use, and Dissemination of 3D Models of Human Remains: A Case Study from Portugal" Heritage 5, no. 3: 1637-1658. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage5030085

APA StyleAlves-Cardoso, F., & Campanacho, V. (2022). To Replicate, or Not to Replicate? The Creation, Use, and Dissemination of 3D Models of Human Remains: A Case Study from Portugal. Heritage, 5(3), 1637-1658. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage5030085