1. Introduction

The study of the urban morphology of Zagreb in the second half of the 19th century was done with the intention of showing the importance of inherited urban morphology and the importance of urban identity factors at a time when preparations are being made for reconstruction after the 2020 earthquake.

Zagreb experienced two major earthquakes—one on 9 November 1880, and the other on 22 March 2020. The consequences of both earthquakes were severe damage to residential and public buildings. The earthquake in the 19th century prompted the first modernization of the city in the way of a large expansion of the city (Lower City) according to the principles of urban ideals of the second half of the 19th century. The earthquake in the 20th century caused great damage to the Lower Town, which has not been thoroughly rebuilt since its inception, so now is the opportunity and obligation to carry out a thorough reconstruction and rehabilitation of the city from the late 19th and early 20th century.

Therefore, the aim of this article is to point out the main identity features of the historical fabric of the city, from which we must start in considering the modern concepts of preservation, restoration, rehabilitation, improvement and modernization. In doing so, the basic features of a historic city belonging to the Central European urban tradition and culture must be preserved. The aim is to point out the landmarks important for the rehabilitation of the historic town of the late 19th and early 20th century, which, after more than a century, needs to be restored and modernized, while preserving important features that make it a cultural asset and urban heritage.

Although it developed in the vicinity of the Roman town Andautonia, Zagreb is a medieval town and is first mentioned in 1093. In 1242 the town was decreed a free and royal free town. Up until the mid-19th century Zagreb was a small town, after which it began to develop rapidly into the capital of Croatia, which was then part of the Austrian (Habsburg) Monarchy. Since the Middle Ages and up until 1850, Zagreb had been developing on two adjacent hills—

Gradec, which was the civilian city under King’s administration, and

Kaptol, the ecclesiastical and bishopric centre. On the whole, both

Gradec and

Kaptol have a planned urban structure and their layout is characteristic of medieval towns [

1,

2]. In 1850, they were joined into a single town, which provided conditions necessary for the planned development of Zagreb. (

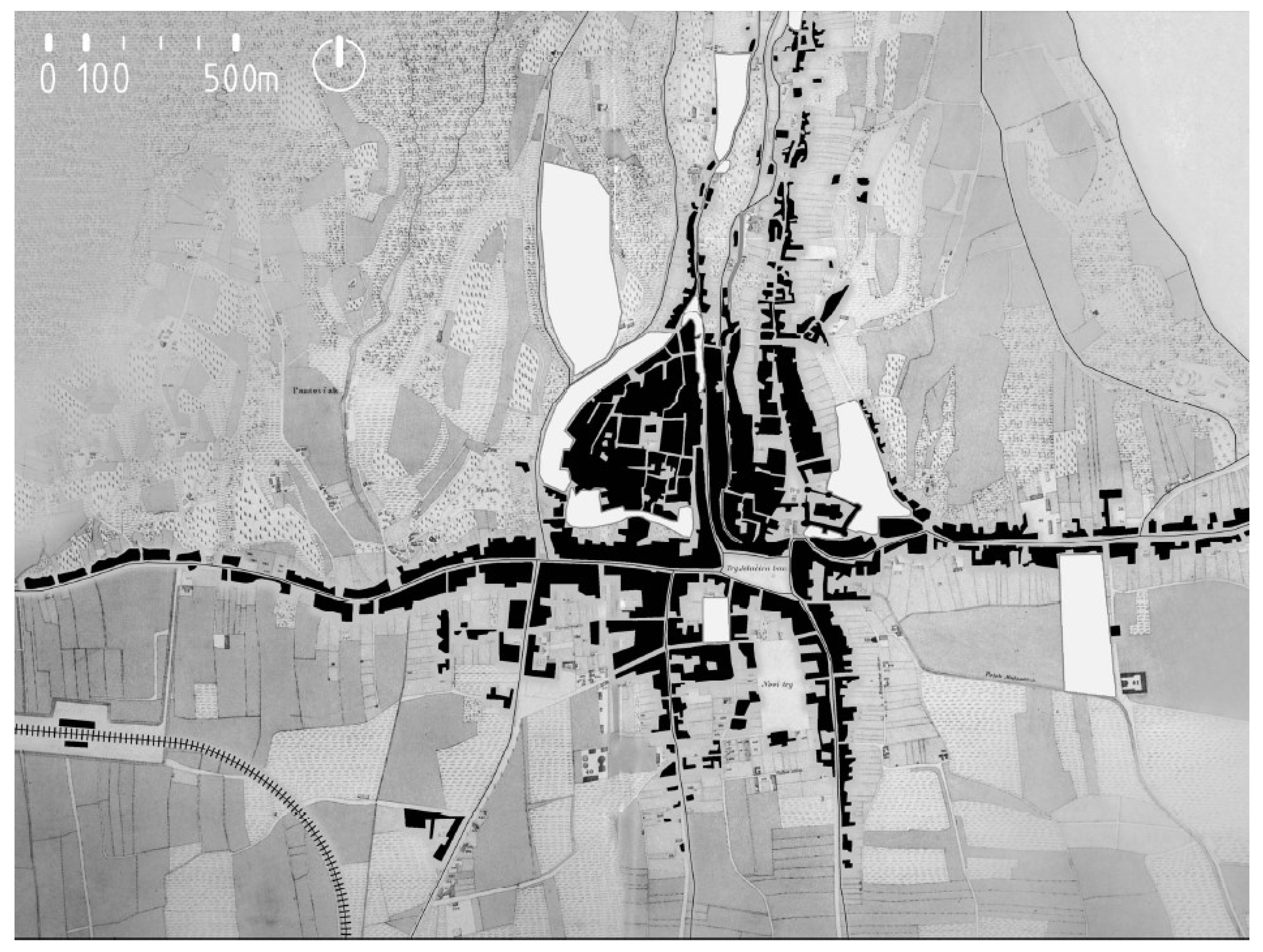

Figure 1).

In 1857 Zagreb had 18,000 inhabitants, in 1900 there were 62,000, whilst in 1921 figures rose to 100,000 inhabitants. The railway running from Vienna to Zagreb was built in 1862 and the first larger industries and banks appeared around 1870. Running water and the waterworks appeared in 1878, the first horse-drawn tram appeared in 1891 and electrical trams were introduced in 1910. The Academy of Sciences and Arts was established in 1866, the University was founded in 1874, and a new theatre was opened in 1895. After a major earthquake in 1880, Zagreb began to develop more rapidly and in a planned fashion.

There are four main districts with differing urban structures within the central area of modern-day Zagreb: (1) the medieval urban structure of a twin cities Gradec and Kaptol with villas and summer residences located on hilly terrain in the north, (2) the urban structure of the Lower Town between the historic core and the main train station, (3) the modern, urban structure which grew up as the town periphery which was transformed while unplanned construction began between the main train station and the River Sava, and (4) the new town—New Zagreb according to urban modernist’s principles of the Athens Charter before World War II, as the second modernization of the city.

2. Materials and Methods

The research was conducted for the historical part of Zagreb. There are several legible and stylistic layers of the city, of which the medieval-renaissance layer (up to the 17th century), the baroque layer (17th and 18th century), the historicist layer (19th century) and the protomodern layer (at the beginning of 20th century) are recognizable in the fabric of the city. The basis for the research were old maps (for the periods up to the middle of the 19th century) and urban plans (from the middle of the 19th century onwards) [

3]. The research also relies on published works that bring the results of more comprehensive research on the entire historical part of the city and the urban genesis of Zagreb. This method allows us to identify solid points within the tissues of the city, especially public buildings and public outdoor spaces (squares, parks, streets, promenades). We consider these points and spaces of public importance to be strongholds for future plans for the restoration, rehabilitation and revitalization of the town’s historic space. Scientifically based research results will be able to be applied in the contemplation of contemporary interventions in the historic city.

The research presented in this article uses previous research on the historical development of Zagreb, which was conducted and published on the basis of systematic archival research. For the older historical periods of Zagreb until the middle of the 19th century, the works of Lelja Dobronić are referenced [

1,

2,

4], and for the period of the second half of the 19th century and the first quarter of the 20th century, the works of Snješka Knežević are referenced [

5,

6,

7]. Other papers focused on selected topics were also used [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13].

Theoretical texts on public spaces and urban rehabilitation were used less for research in this paper because the aim of this research was to determine the essential components of the urban fabric and recognizable features of the historical part of Zagreb. It is precisely these character traits of the historic town that become the starting points for models and principles of restoration, but this is another topic that will be developed in the continuation of the research. From the theoretical aspects, two topics were highlighted: (a) urban forms (urban block) since the historical part of Zagreb is a city of blocks and (b) sociological aspect because each city is made up of people and way of life. We can renovate city blocks by respecting the historical structural features, but it is also necessary to modernize them and adapt them to modern needs [

14]. City blocks and city fabric have been a constant of the city from ancient times to the present day, so it must be placed in the context of the general development of the city [

15,

16]. The sociological aspect is much more complex due to demographic changes and lifestyle changes, so this topic is not the subject of this research, although it is important and unavoidable for urban renewal in the context of sustainability of living historic cities [

17]. From the point of view of traditional urban civic culture, an important aspect is the ambience and historical urban scenography, which is often referred to especially in public parks and promenades where it was important to be seen and seen by others [

18].

To achieve the expected results, it was necessary to consider the context in which Zagreb lived in the first and second half of the 19th century—before the earthquake in 1880, and the context of the second half of the 19th century when begins the great expansion of the city and the first urban modernization.

2.1. Urban Circumstances in the First Half of the 19th Century

The development of Zagreb in the first half of the 19th century was not carried out according to any urban plans, which means there was no controlled urban expansion. Instead, the town developed spontaneously around the main town square located beneath the medieval towns of

Gradec and

Kaptol and there was intensified urban development along the access routes to the town. (

Figure 2).

From the end of the 18th century and up until the mid-19th century, public parks and gardens began to be laid out in peripheral areas and outside the borders of the medieval towns of

Gradec and

Kaptol. Maksimir Public Park was laid out in Zagreb’s east environs by the bishops of Zagreb, from the end of the 18th and up until the mid-19th century [

19], while the Bishop’s Park was laid out east of

Kaptol in Vlaška Ulica (at the end of the 18th century), and Ribnjak Park was laid out along the eastern rim of

Kaptol (1830). Two public promenades appeared along the fortification walls of medieval

Gradec in the first half of the 19th century—the North Promenade and the South Promenade, and additional large parks were laid out in the vicinity of

Gradec around villas and summer residences [

11]. (

Figure 3).

2.2. Urban Circumstances in the Second Half of the 19th Century

In the second half of the 19th century, Zagreb began to develop in a planned manner over the area south of the medieval towns of

Gradec and

Kaptol. Today Zagreb includes

Gradec (the Upper Town) and the area lying to the south of it, known as

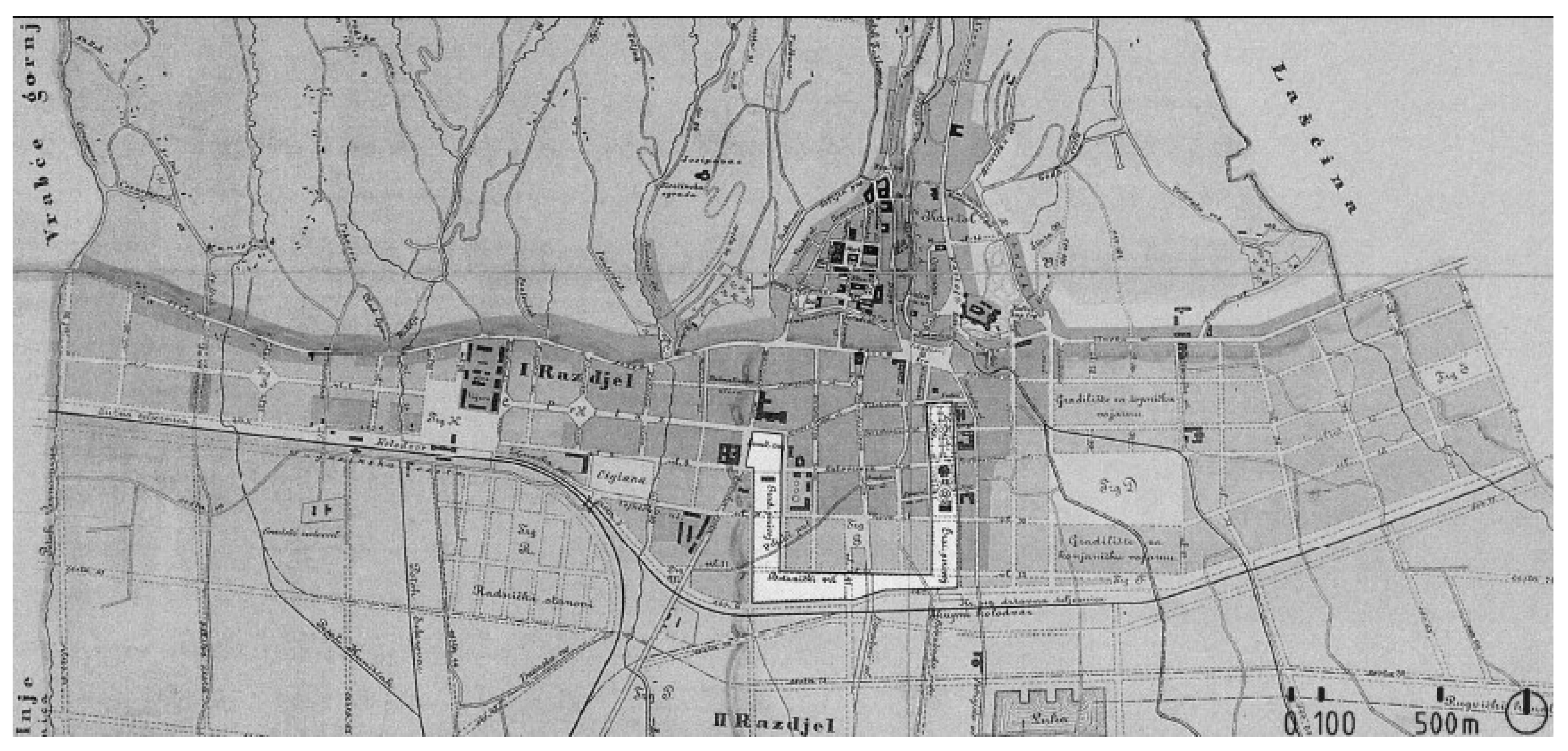

Donji grad (the Lower Town), which developed in the second half of the 19th century. This area was mostly privately owned, so that town authorities acquired the land gradually. A number of civil laws were introduced for its further development as were the first urban town plans, which led to its orthogonal design and “block-like” development (rectangular grid plan)—the first plan of Zagreb was produced in 1864/1865 [

8] (

Figure 4), and a second plan in 1887/1889 (

Figure 5). An additional, supplementary development plan was produced in 1894.

The regularly shaped ground plan of Zagreb began to appear after legislations on the development of the town were passed in 1857 (Law on the Development of Zagreb). These provisions were the basis for the layout of Zagreb in the second half of the 19th century [

6].

The aim of the first urban plan of Zagreb (1864/1865) was to develop and renovate the older parts of the town, and to harmoniously conjoin the newly planned areas with existing structures (

Figure 4). The principle incorporated in the first urban plan (1865), which provided for a grid of intersecting streets placed at right angles, continued to be applied in the second urban plan (1889) and this design extended from the town centre and towards the east and west [

6], but it also incorporated a slight difference—greater distances were envisioned between the streets (the surface area of the blocks was larger). The second urban plan was completed nine years after the earthquake. That plan was a response to rebuilding the city after the earthquake. A model of building a new city next to the existing historic city was applied. The New Town (Lower Town) took on the characteristics of the then modern Central European urbanism and marked the beginning of the first modernization of Zagreb after eight centuries of continuous existence of the city (

Figure 5).

Apart from the urban development plan from 1889, a new development scheme was established whereby the town was subdivided into three parts/zones with provisions for facilities, amenities and conditions for their development. In 1894 additional provisions for the centre ordained that building should have at least two storeys and be uniform in height; in addition, the height of buildings in relation to the width of the streets was defined, as well as the size of courtyards, etc. This well-deliberated urban planning with a clear urban matrix and vision continued to be applied well into the beginning of the 20th century (

Figure 5).

2.3. The Framework and Concept of Squares in the Lower Town of Zagreb

The drafting of the second urban plan of Zagreb from 1889 was headed by the key town urban planner, Milan Lenuci. The concept for the urban structure and design of the Lower Town has three distinct themes: an orthogonal street grid, public city parks and squares, as a new element in the urban development of the town in the 19th century, and public buildings (a theatre, the Academy of Sciences and Arts, the Art Pavilion, the Main Train Station, the National Library and University Library, etc.). The U-shaped “Lenuci Horseshoe” is the name given to a series of seven parks (squares) including the Botanical Garden, which are incorporated within the urban block network (

Figure 5 and

Figure 6). This urban development concept was drawn up in 1882 and designs were legally defined in 1889, although they were later gradually implemented up until the 1920s [

6]. This series of parks and squares became a distinctive motif in the urban morphology of Zagreb at the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century [

11].

After the earthquake in 1880 Milan Lenuci (1849–1924), an urban planner and engineer who studied in Graz (Austria) and was inspired by Viennese and Parisian models, played a crucial role in the construction of the new centre of Zagreb—the Lower Town. Lenuci was not the initial creator of the original concept of the Horseshoe, but was responsible for its urban design and execution [

6]. The initial, as yet incompletely defined concept, was conceived before he assumed the role of city urban planner, but it was he who first formulated a planned design, which was included in the second urban plan. His merit lies in the fact that he persevered the planning of the Horseshoe which was completed despite numerous influences and interests that might have prevented its realisation. Whilst most of Lenuci’s other ideas and projects for Zagreb were not realised, or at least not entirely, he undoubtedly laid the foundation for the urban development of Zagreb in the 20th century.

3. Results

To answer the question of the urban morphology of the Lower Town in Zagreb, the research is focused on recognizing the basic urban features of each city, especially the historic city, namely: urban grid, urban blocks, squares, streets and building typology.

The appearance of the Lower Town and its morphological characteristics were influenced by two urban plans (1865, 1889) and three successive instances of construction and approved regulations (Order of Constructions from 1857, 1887 and 1894). Despite urban regulations for each instance of construction (from the construction of new streets to the landscaping of open spaces), long and heated debates ensued, resulting in the coordination of differing interests.

3.1. Urban Grid—Map of the Town

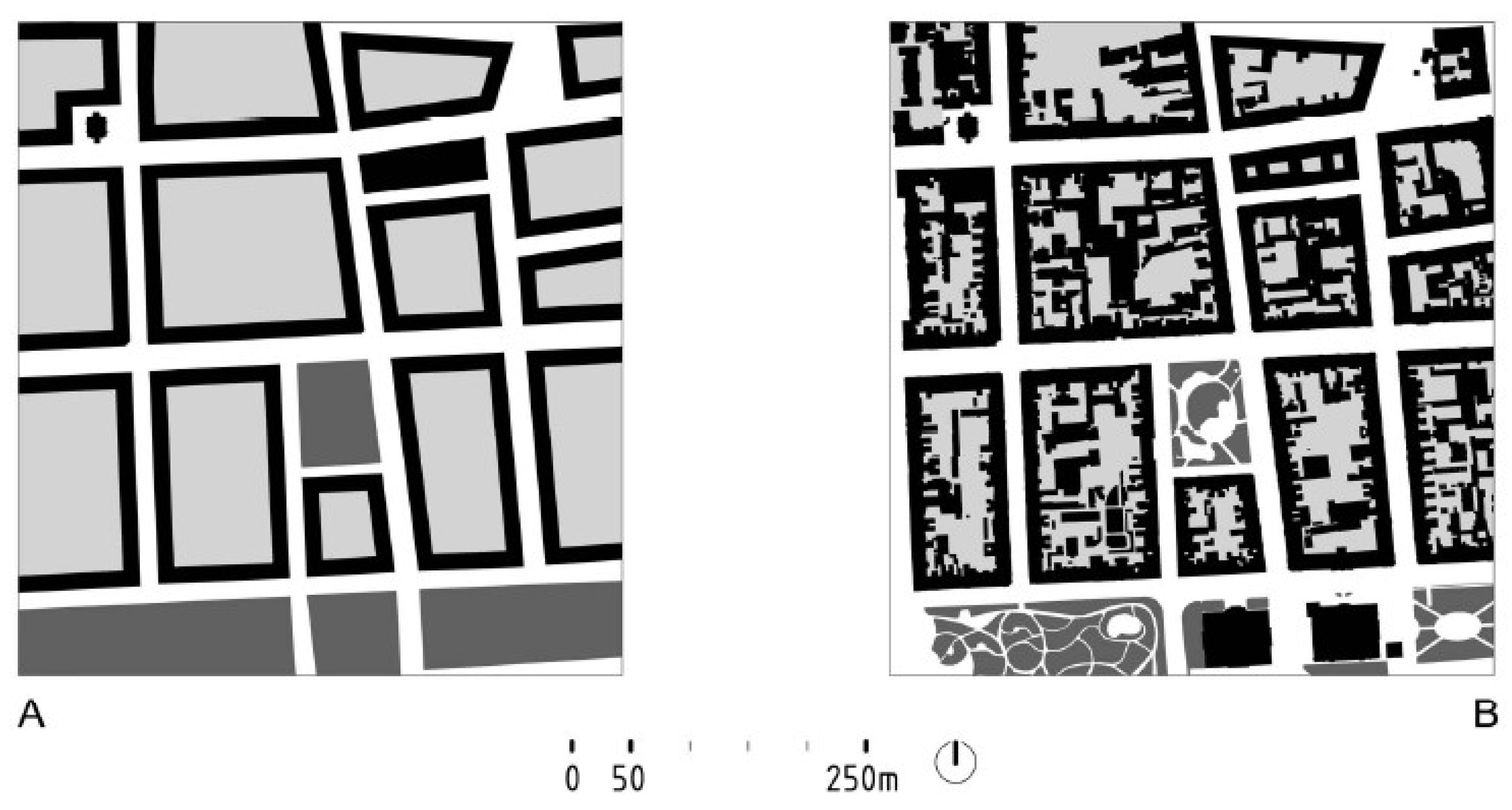

The design of the town was based on rational urban principles and urban blocks/islands built along the edges and the façades of these residential buildings shaped the town streets. Although the original concept was to adhere to the ideal of an orthogonal block system, this proved impossible as there was a need for it to be adapted to existing circumstances, which is why most blocks in Zagreb are irregular in shape and appearance and form unique and individual series, so that each block differs in size and shape. They are rarely square, but rectangular or trapezoidal in shape.

The origin of the orthogonal street network dates to construction regulations from the mid-19th century. Provisions for urban development from 1857 ordained that street be built and traced at a width no less than 13.30 m and that intersections be at right angles and at a distance between 76 and 95 m. These dictates defined the initial urban structure and the construction of blocks. The first urban plan from 1865 (

Figure 4) was transposed onto the charted plan and design provisions from 1857.

It was not possible to achieve an ideal network of city blocks and streets as there were a number of limitations, of which the most important were: existing roads (old roads that led from the environs and into the city, which had been in existence since the late Middle Ages, and including more recently constructed roads), existing good quality construction along the main roads, inherited plot divisions (cadastral system), watercourses, privately owned land, the possibility of land acquisition for public needs, and others. Before the first urban plan most of the Lower Town was farmland and rural in character—arable land, pastures, orchards, gardens, vineyards, groves (

Figure 3). The terrain sloped slightly to the south and was intersected by larger and smaller streams which flowed from the north and southwards from the mountain

Medvednica (the

Zagrebačka Gora) and towards the River

Sava and the valley beyond. There were also numerous branches of the River Sava, which periodically flooded the adjacent terrain. The new town plan changed this rural-suburban landscape completely.

The realised network of streets, as a compromise between the desired ideal grid and adaptations to numerous constraints, determined the shape and size of city blocks and squares, and also the width and appearance of the streets.

3.2. Urban Blocks

As a result of adaptation to local conditions, almost no two blocks are of the same size and shape. Their ground plan is frequently rectangular and trapezoidal, and rarely square. The smallest town block is 1800 m2, the largest is 44,700 m2, and the average block size is around 13,000–15,000 m2. All the blocks are enclosed and the buildings are placed on the property line along a street line. Exceptions are rare and are to be found along the western stretch of the Horseshoe where the buildings are removed within the interior of the block, allowing for the landscaping of small gardens between the building and street. The street façades are not uniform, neither in character, width, height, nor in design, as buildings were not built at the same time; land plots vary in width and belong to different owners, whilst corner buildings are architecturally highlighted.

The blocks are mostly residential, except for along the edges of the Horseshoe squares where the outer façades of the block include buildings intended for public purposes, such as courts of law, university buildings, churches, and others. The inner courtyards of the blocks were originally landscaped and were utilised mainly as gardens and orchards, either as private or shared space for tenants living in the surrounding buildings. In the first half of the 20th century, in places, the inner courtyard spaces of blocks incorporated residential buildings and crafts workshops and warehouses, and in the second half of the 20th century, kindergartens, schools, playgrounds and garages. The blocks did not have roads and access for vehicles was only possible in the form of passage through the building. (

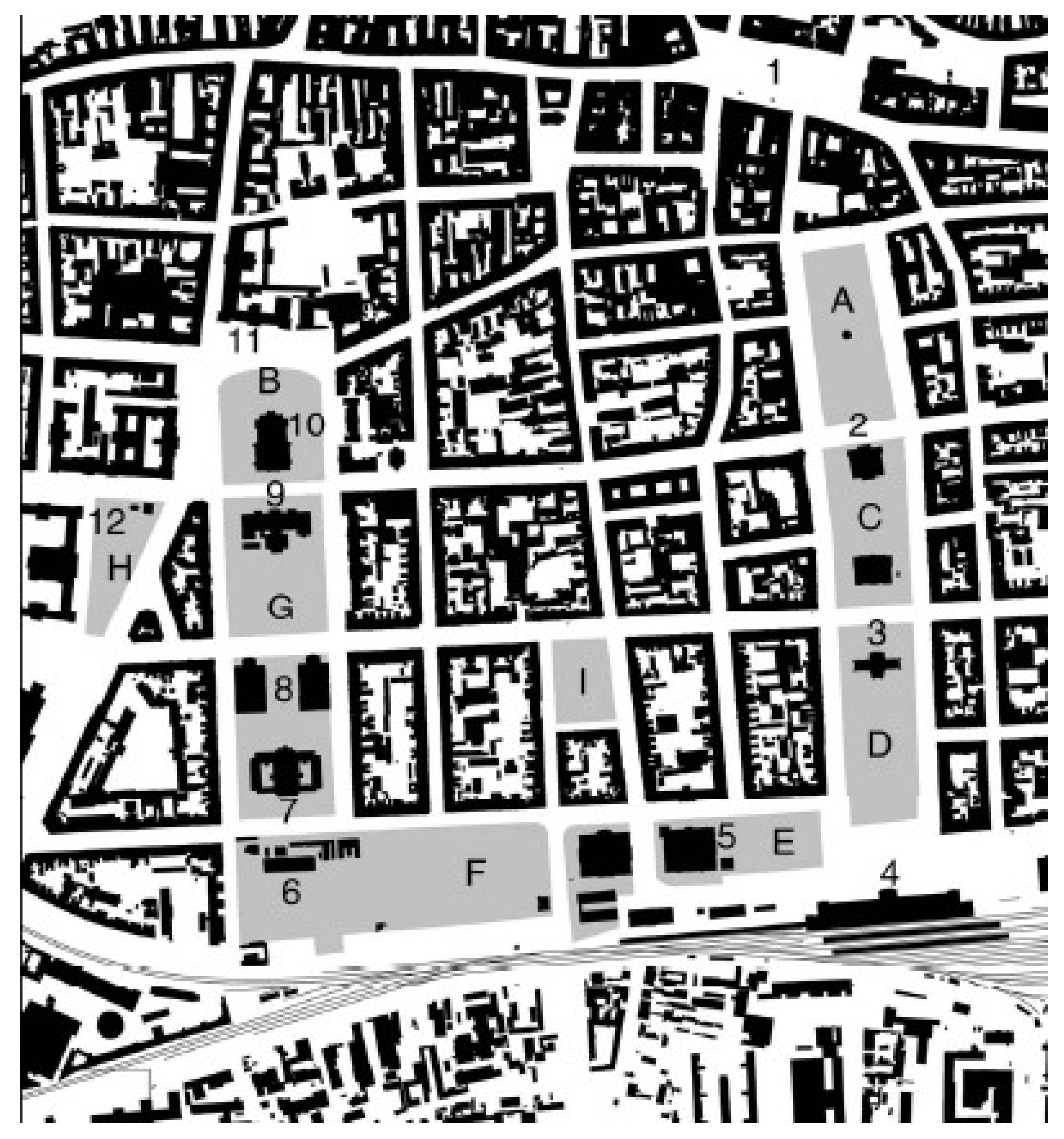

Figure 7).

3.3. Squares

Squares in Lower Town in Zagreb have been historically researched, the genesis, sequence of construction and construction of buildings on the squares are known. Zagreb’s squares are well documented in books and articles created as a result of many years of research of the Lower Town and Lenucci’s Horseshoe [

5,

6,

7,

11,

13,

20].

All the squares in the Lower Town are newly planned squares, laid out in the second half of the 19th century (

Figure 8). Until then, there was only one square in the Lower Town—

Harmica (present-day Ban Josip Jelačić Square), located beneath

Gradec and

Kaptol, and utilised as early as the Late Middle Ages as a space for trading and for trade fairs. The first square in the Lower Town (New Square, modern-day Nikola Šubić Zrinjski Square), located 100 m south of the medieval square

Harmica, began to be laid out on the basis of the first urban plan. Its rectangular shape (100 × 220 m) in pursuance of the Order of Construction from 1857 dictated its regularly shaped ground plan. This was the first in a series of squares in the Lower Town and the starting point of the eastern stretch of the Lenuci Horseshoe. The starting point of the western stretch of the Lenuci Horseshoe was University Square (present-day Republic Square), which began to be laid out after the introduction of the second urban development plan [

6].

The Lenuci Horseshoe includes seven squares and the Botanical Garden. At the beginning of the 20th century two smaller squares (present-day Svačić Square and Roosevelt Square) were laid out. All these squares were laid out without any inherent urban tradition. Two of the squares (Zrinjski Square and University Square) were laid out at the site of cattle fairs, which means that the tradition of spaces where people gathered was continued. The remaining squares were laid out on the basis of the second urban development plan. All the ground plans are regularly rectangular in shape; none are of the same surface area and each is adapted in shape to conditions dictated by the micro-space in which it is located. Their surface areas range from 2.25 to 2.98 acres. Three of the Horseshoe squares, as well as two of the smaller lateral squares, are landscaped parks, whilst four of the Horseshoe squares are architectural squares with public buildings [

6].

The squares of the Lower Town are preceded by squares from earlier periods, followed by numerous new squares created during the first half of the 20th century [

21]. The system of squares as public town parks offers the town open spaces for leisure, entertainment, relaxation and free-time activities, a form of daily life outdoors (

Figure 8). These spaces do not tend towards being pretentious, over-representative, theatrical or full of symbolism; on the contrary, each square represents space made to the measure of man in the spirit of Late Romanticism, Historicism and Art Nouveau. The transformation of Vienna and the design of the Ringstrasse in the second half of the 19th century was the inspiration for the Lower Town Squares project [

18].

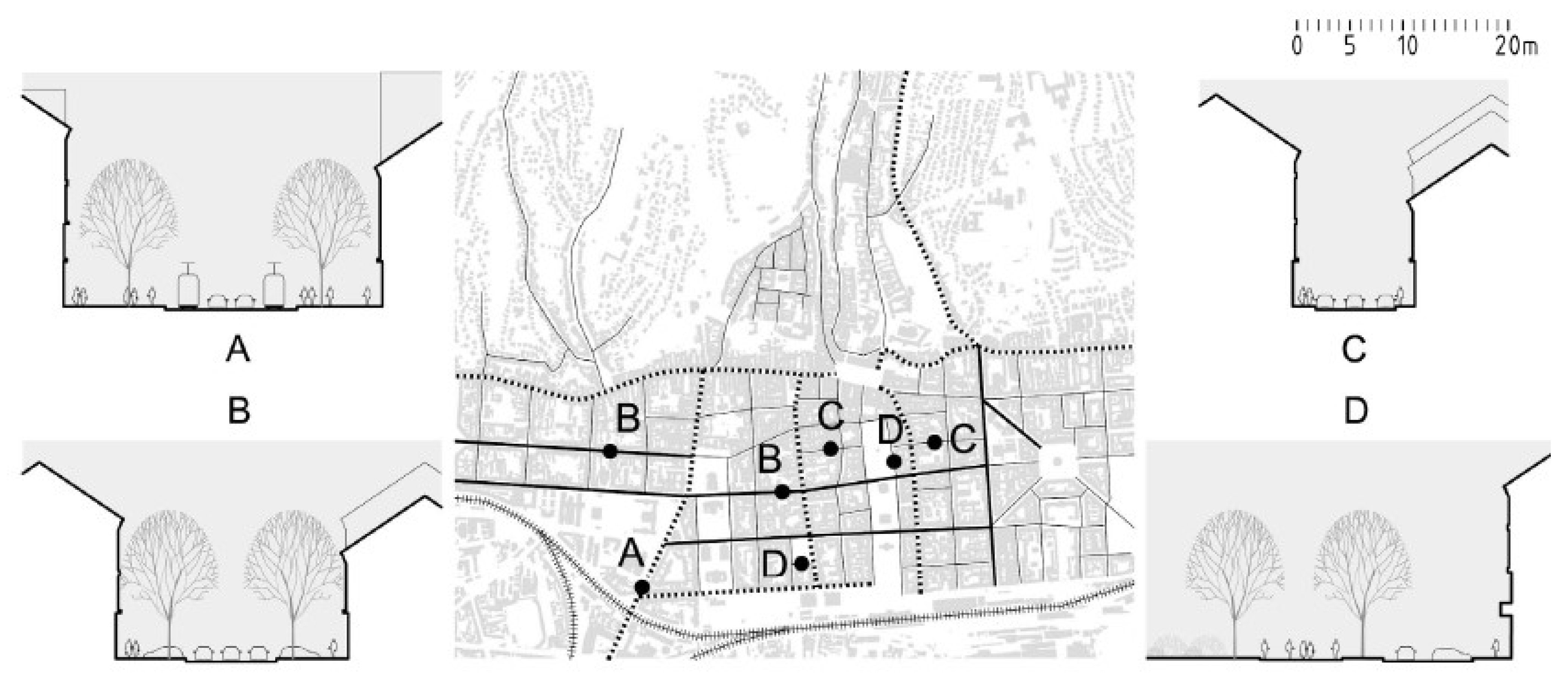

3.4. Streets

The network of streets is laid out based on the directions of the compass: running in a north-south and east-west direction, with minor deviations in view of existing roads and paths. According to their position/alignment two types may be observed: those roads that existed previously and newly planned town streets. Within the area of the Lower Town several access roads leading to

Gradec and

Kaptol existed even during medieval times:

Ilica Street and

Vlaška Street (accessed from the west and east) and

Savska Street and

Petrinjska Street (accessed from the south). These formerly planned roads in the Lower Town became important traffic thoroughfares. Of the three tree-lined streets (laid out running in an east-west direction) the most important is the urban avenue that connected the first railway station (in 1862; now

Zapadni kolodvor, West Railway Station) and the city centre. University Square arose at the conjunction of the connection point of this avenue (now Gjuro Deželić Street) and the centre of the Lower Town, which is also the starting point of the western stretch of the Horseshoe. Street widths range from 10 to 22 metres. Tree-lined streets are the widest (around 22 m), and the rest are predominantly around 12 to 15 m. (

Figure 9).

3.5. Building Typology

The first and second urban plans dictated regulations for the construction of buildings. The provisions for urban development from 1857 ordained that building be constructed along the property line (edges of the streets), that they be conjoined and no lower than one storey. In the second urban plan (1889,

Figure 5) the town was divided into three parts/zones (

Figure 5 and

Figure 6). Zone I encompassed the area between the medieval cores of

Gradec and

Kaptol and the railway tracks and to the south. Buildings constructed in this zone had to be two to three storeys high. In Zone II, further to the south and between the railway tracks and the River Sava, plans foresaw the construction of single-storey houses and the establishment of “clean” industries, which also applied to the hilly Zone III, which lay to the north of

Gradec and

Kaptol.

In the Lower Town (i.e., in Zone I according to the second urban plan from 1889) there are three types of buildings: 1. residential buildings in blocks that make up most of the construction, 2. buildings predominantly intended for social purposes incorporated within the construction of residential buildings (courthouses, university buildings, and others) and 3. public building located around the Horseshoe squares (

Figure 10).

Blocks are mainly divided into uniform elongated rectangular city plots, placed with their narrower side facing towards the street. Thus, the size of the building is determined by the width of the plot in relation to the street.

The most common type of residential housing is condominium buildings with flats for middle and upper-middle class citizens. As far as the ground plan is concerned, these are square, rectangular and L-shaped buildings. There are small flats on the ground floor and in the attic. Another type of residential building constructed for the upper classes is single-family palaces, which are, as a rule, positioned so that they overlook the Horseshoe squares. Buildings lying within the blocks were not originally planned and are not essential in the morphological sense. Public buildings are important for the urban concept of the Lower Town. The Lenuci Horseshoe was conceived and designed as a public space, a kind of urban stage with numerous public cultural, scientific and art buildings and universities—all the buildings important to national culture, except Parliament. These buildings located on the squares became visual landmarks and dictated the new urban benchmark for their environs because they were usually built before the surrounding residential blocks [

6].

4. Discussion

This research focused on the central part of the Lower Town. The eastern part of the Lower Town was built later, after 1905 when Milan Lenuci drew up an urban plan. That part of the town is not covered by this research. It is a logical continuation of the former Lower Town, but it is already a protomodern era with new views and approaches.

Detailed plans and the design for Lenuci’s Horseshoe were never produced; neither were a plan for their implementation which would define the structure and specific morphology (detailed allocation and urban and architectural design), or costs, the organisational implementation scheme, etc., unlike in the case of the Ringstrasse in Vienna or the Andrassy Avenue in Budapest. No public tender for the urban and architectural design of Lenuci’s Horseshoe, or any part of it, was ever issued. Lenuci’s Horseshoe remained incomplete up until the end of WW I, and so work continued in the years between the two World Wars—in the 1920s and 1930s. Despite minor changes to the initial plan, in essence, further construction of the Horseshoe continued according to the initial plans for the creation of a series of uninterrupted parks and squares with public buildings.

The concept for this framework of squares/parks in Zagreb was based on the Ring concept applied in many other towns and cities in Europe. Although the concept and inspiration for the model was the Ringstrasse in Vienna, the urban development of Zagreb was different. In Vienna, as in most other European cities, parks and squares with public buildings were laid out at the site of old renaissance/baroque fortifications. However, Zagreb did not have such fortifications. The idea was to separate the central part of the town, intended as a residential area, from the industrial zone of the town, including the train station (engines ran on coal and produced dense smoke). In addition, a series of squares/parks afforded enough space and the possibility for public and cultural buildings of vital importance for the town and state to be founded and built. (

Figure 11).

Zagreb’s medieval settlements

Gradec and

Kaptol, located on hills above the Lower Town, retain their historical dimension and, in part, their mediaeval and renaissance fortifications. The town was expected to expand across the flat terrain beneath the two settlements. The model selected was that which was recommended for urban mono-functional areas, and certainly not one for city centres, which is an orthogonal grid. There are both advantages and disadvantages to a rectangular network. In no instance is the ground-plan layout for the old city walls in Zagreb semi-circular, which would make it difficult for a series of equally sized, regularly shaped squares to be laid out. The urban grid does not provide for individualisation of the urban environment, nor does it provide sufficient challenges for artistic imagination and opulence in design, as in the case of circular boulevards such as the Vienna Ring. The Zagreb Horseshoe does not encompass the medieval town; it extends and stretches across spaces that lead from the old city core and across what were once fields and meadows. (

Figure 11)

Zagreb does not have a main new avenue, which would emphasise its urban axis, like Andrassy Street in Budapest, Unter den Linden in Berlin and Corso Sempione in Milan. Gjuro Dezelic Street in Zagreb has all the characteristics of an avenue, but it is small compared to the urban impact of the Lenuci Horseshoe. It is discernible, but does not dominate the urban fabric of the city.

The Lenuci Horseshoe is not a boulevard, although it includes certain elements typical of a boulevard. The Horseshoe is not an avenue but it is a sequence of squares, forming a horseshoe shape. The Horseshoe is not a ring, although it could also be interpreted as such, despite not being round in shape.

The Horseshoe includes public buildings located within the squares, whereby it differs from Vienna and other cities. The Horseshoe was not established at the site of earlier town fortifications. It was created as an original conception in the spirit of the European urban aesthetics of the late 19th century. Milan Lenuci was well-versed in the typological models of European cities which definitely provided inspiration and served as a role model for Zagreb. However, due to the urban, landscape and topographical context, as well as other forms of constraint, a distinctive urban blueprint for Zagreb was created, which differs from other similar European cities.

5. Conclusions

Zagreb’s Lower Town from the second half of the 19th century is the expression and result of “urban utopian times, a period which believed in Harmony and Beauty, and which was based upon an idealised concept of the Town” [

6]. We can consider it the revival of the ideal city of the late 19th century. The Lenuci Horseshoe, consisting of seven squares and the Botanical Gardens, is the most valuable urban enterprise from the 1880s in the whole of Croatia and it opened the doors to similar, although less demanding, enterprises in other Croatian towns.

The urban grid of Zagreb’s Lower Town and the squares/parks of the Lenuci Horseshoe are an embodiment of the urban principles of the 19th century, which are also to be found in other European cities. However, other urban solutions, which differ from those for other cities, were found for Zagreb. Therefore, Zagreb may be relevant in the study of the urban morphology of cities dating to the second half of the 19th and early 20th century.

The research indicated the following:

Urban grid is based on an orthogonal network that deviates from the rules due to existing plots (cadastre), ownership, existing roads and part of the existing construction along the existing roads in the fields. The urban grid is part of the identity of the city, a historical matrix that must not be changed (enlarged or fragmented) if we want to preserve its authenticity.

Urban blocks show diversity and a reluctance to uniformity. Almost no two blocks are the same, although the experiential general impression is of a “urbs quadrata”. By keeping the street traffic network, we also keep the urban blocks. Towards the street the urban blocks remain unchanged in terms of the position of the buildings and the architectural front. Changes are possible in the interior of blocks where different types of interiors are found—from a few original gardens and orchards to the construction of apartment buildings, service buildings and public buildings (schools, kindergartens, etc.), often high-density construction. The interior of the blocks remains preserved for new modern functions and modern construction or for a modern interpretation of the original landscape of the block.

Squares and parks as public spaces are an indicator of the high urban and architectural culture of the time when they were created in the late 19th and early 20th century. Over the centuries of existence, some have undergone minor changes, which allow the restoration of the original appearance if desired. It is precisely these public spaces that are the important factor of identity and individuality by which Zagreb differs from other Central European cities of the former Habsburg Monarchy.

Streets are appropriate widths for the age in which they were formed, often with tree lines. Today’s use with numerous car parks changes the former cross-section and appearance, as well as the partial function of the promenade. Therefore, one of the main issues is the removal of cars from the streets and their placement in garages inside the block.

Buildings significantly affect the experience of the city, its function and aesthetics, especially public buildings (

Figure 10) whose construction followed due to the impossibility of construction in medieval Gradec (Upper Town). Public spaces and public buildings located in the middle of park squares are the most impressive contribution of the realized urban concept. Without public buildings and public spaces, as symbols of urban and social culture, the city would be deprived of recognizable ambiences with a predominant monotonous housing construction. They have priority in rebuilding the city.

These five essential components of a historic town should not be excluded when considering, planning and checking a comprehensive renovation—whether it is the rehabilitation of a damaged city, revitalization of neglected parts of the city, modernization of outdated technical and communal infrastructure or modernization a Lower town that has not been thoroughly rebuilt since its origin a century and a half ago. Therefore, the main question is how to read the historical inheritance of Lower town and draw ideas and possible preservation insights for modern reconstruction from it.

In the next decade, large-scale works are expected in Zagreb on the reconstruction of the city that was damaged in the 2020 earthquake. Zagreb needs an urban rehabilitation of the historic city from the end of the 19th century and modernization, which can be understood as the third modernization of the city. An important role in this is played by the inherited urban morphology, which indicates the identity features of the urban fabric of the city.