1. Introduction

The objective of this paper is an examination of how the heritage context of colonial settlement can be re-evaluated through a contrary viewpoint to the conventional approach of urban morphology that seeks to understand urban development from its genesis, represented in archival survey maps as the starting point. Instead, we observe that these maps are also evidence of an end point of a cultural landscape, an unintended artefact of this particular heritage.

Urban morphology is the study of the structure of a city’s form [

1,

2] from its ‘formation to subsequent transformations’ [

3] (p. 3). The study of urban morphology is concerned with the physical and spatial layout of urban structure and the processes that give rise to them [

4]. Particular attention is given to the plots, blocks, streets, buildings and open spaces which are all integral to the study of the ‘history evolutionary process’ of specific parts of a city under consideration [

5] (p. 67). By recognising that ‘the past provides the key to the future… the spirit of a society is objectivated in the historico-geographical character of the urban landscape and becomes the genius loci’ [

6] (p. 6).

There are several factors for the colonial settlement of Australia, from the earliest British interests in the latter 1700s that led to the founding of Sydney, Hobart and Brisbane as penal colonies and locations of defence. These were soon followed by Perth, Melbourne and Adelaide as new centres of free settlement, investment, speculation and trade [

7]. At the outset of each settlement, the colonial authorities relied heavily on the ingenuity of the surveyors to assess the aspirations of the colonial authorities against the landscape characteristics and attributes of the site under consideration to support the decision to establish each particular settlement. While the configuration of Sydney and Hobart aligned to the topography and were somewhat loose in geometric pattern, the other major cities were conceived as orthogonal street grids of varying proportions and allotment subdivision. These schematic boundaries, once established and either sold at auction or designated for public function, would maintain as the morphological template for future development. Arnis Siksna undertook comparative analysis of the size of several Australian and American city block formations, his study revealed that the relationship of ‘block size and form have crucial and predictable effects on subsequent evolutionary patterns’ [

8] (p. 24).

However, can there be other readings of survey and settlement maps of colonisation? While these maps are in themselves heritage artefacts as historical archives, can they be viewed as markers in a specific, dynamic, and even drastic time of change? Are these maps instruments of the control and power that affected the change? Can we intriguingly examine the mapped evidence from a perspective of its preceding time, as the end rather than the starting point of built transformation, as a depiction of the ‘lost landscapes’ of cultural significance?

2. Australian Aboriginal Country

Country is an Aboriginal Idea. It is an Idea that binds groupings of Aboriginal people to the place of their ancestors, past, current and future. It understands that every moment of the land, sea and sky, its particles, its prospects and its prompts, enables life [

9].

Landscape is central to Aboriginal spiritual belief systems, and each area defined by individual language groups is bound to deep understandings of how the physical environment has been shaped, and individual and group responsibility for its custodianship and protection [

10]. Evidence suggests that humans first came to the region at least forty thousand years ago [

11]. From this time, Aboriginal people have lived in accord with the ancient landscape and have adapted successfully to the varying weather conditions and the enormous changes in the nature and extent of their territory. Five and a half thousand years ago the water level in Port Phillip Bay was about two metres higher than at present. Port Phillip Bay was a lot larger than it is now and much of what is now the inner city of Melbourne was submerged under water. As the sea subsided to its current level, many parts of these inner areas became boggy swamps [

11].

The surface features of the Melbourne area we are most aware of today—the shape of the bay, the vegetation and the course of the rivers, have all formed in the past five thousand years. The surface features carry a number of traditional songlines—so named because navigational instructions, geographic features and human-made route markers were coded in song, sung by Aboriginal people as they travelled [

11]. The tribes and clans of the local Kulin Nation utilised these songlines to meet on occasions of plenty in spring and late summer, and these areas served an extremely important purpose for these meetings. Melbourne and its surrounds remain a junction for all the major songlines heading north and west out of the city [

12].

An old river red gum ‘scar’ tree, thought to be at least 300 years in age, with its deep, elongated scar, remains a living, breathing representation of a time when the

Wurundjeri people freely exercised their way of life throughout the area. Uncle Bill Nicholson (a Wurundjeri Elder) describes that ‘the tree was cut with a greenstone axe, quarried about one hundred and twenty kilometres to the north of the site at a place called “

Willamorin”—“Home of the Axe”, a sacred ancestral place where axes have been quarried for tens of thousands of years’ [

12]. The large, long scar indicates that the bark taken would have been fired into shape and used for a ‘

koorong’ or canoe, a flat-based canoe which would have been paddled out into the wetlands.

Wattle and gum trees also covered the area south of the Yarra River. Part of this forest remained up to the 1860s but was lost as a result of the rapid growth of Melbourne, the last remnant being the Corroboree Tree at St Kilda Junction. This tree stands just a few kilometres from the city centre but is largely hidden from view despite the popularity of walking trails. The corroboree tree—or ‘

ngargee’ in the local Aboriginal language—holds the life and memories of the things that went before it. It was the point where people joined and moved through and celebrated the people of this land. According to Carolyn Briggs (an elder of the Boon Wurrung people), for hundreds of years it was a meeting place for boys who would then embark on initiation journeys. Women would also meet there before heading to special places on the coast to learn birthing secrets [

13].

These are some examples of the intricate network of landscape features that contribute towards the manifestation of

Country, where ‘everything is alive and everything is embodied in relationships, whereby the past, present, and future are one, and where both spiritual and physical worlds of

Country interact’ [

14] (p. 14).

3. Surveying for Settlement

Within a short space of time in the mid-1830s, British settlers had started to make dramatic changes in the area which John Batman, one of the first pioneers who had established a small holding on the banks of the

Yarra Yarra River had called it ‘the place for a village’ [

11]. Trees were be chopped down for houses and fires. Animals and birds were hunted for food in greater numbers than ever before. Crops were sown and sheep and cattle grazed. Domestic cats and dogs escaped into the bush. Nothing would ever be the same for the Aboriginal people of the Kulin Nations [

11].

The attention of the colonial authorities was therefore drawn to the suitability of the location for the establishment of a town, and procedures were initiated to affect formal control of the area through a settlement survey and demarcation of streets and allotments for imminent private sale [

15]. However, historical accounts as to the exact attribution of the official foundation of Melbourne has been the subject of some conjecture, with particular reference to the two principal surveyors, Robert Russell and Robert Hoddle, whom were consecutively engaged in the process of imposing its towns plan configuration.

Robert Russell, a ‘pioneer surveyor’, architect, and painter, had been appointed as Assistant Surveyor in 1836 to measure and chart the Port Phillip Settlement (prior to the naming of the Town of Melbourne). He was accompanied by two assistants Frederick Robert D’Arcy and William Wedge Darke [

15,

16]. Russell was ’instructed to observe and report upon all natural phenomena’ [

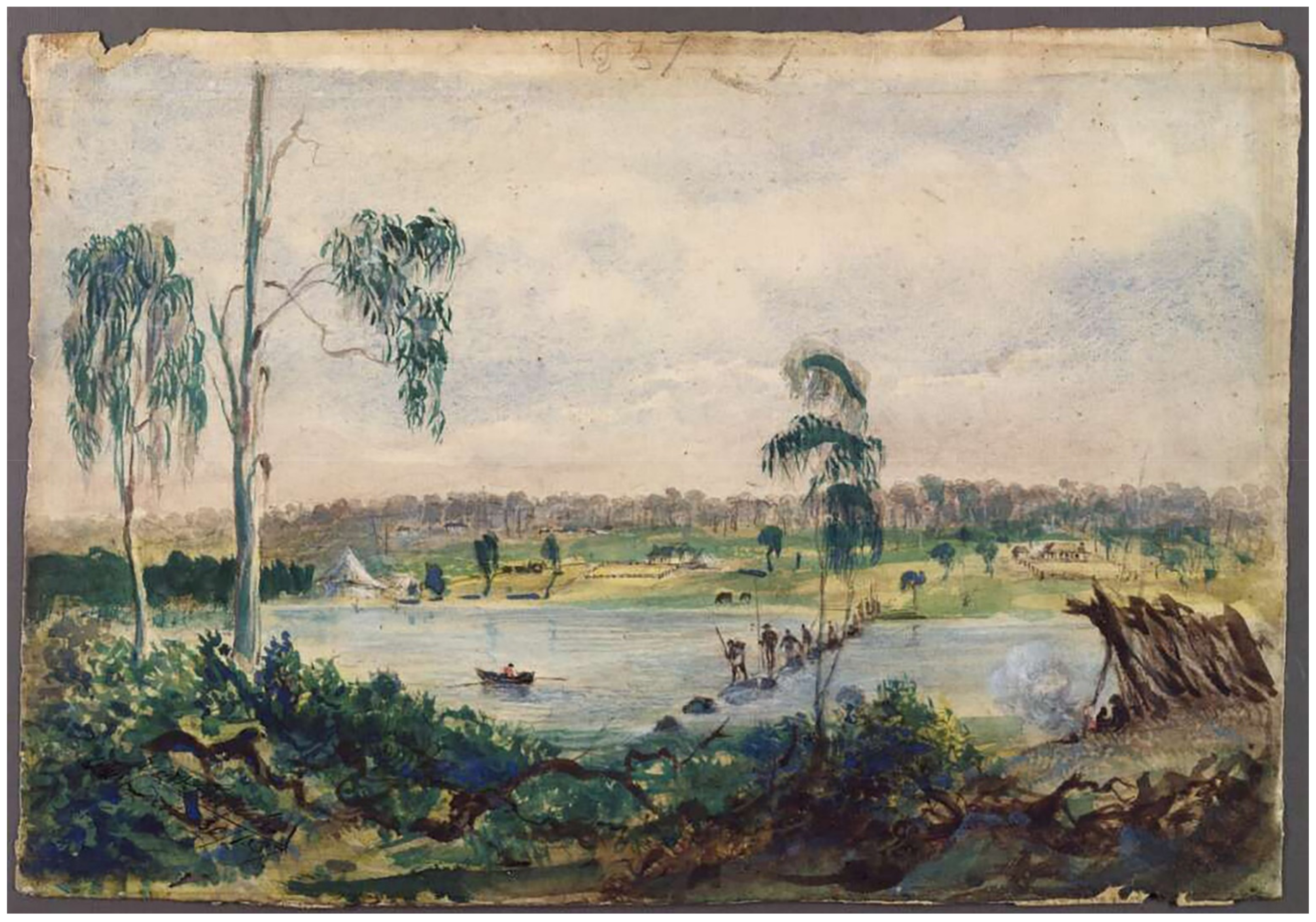

16] (p. 9), and was in charge of the landscape features survey (

Figure 1) and undertook triangulation, with D’Arcy, an excellent draughtsman, who drew the maps [

15,

17].

Greig suggests that despite the lack of any specific detailed instruction in the official appointment letter from the Deputy Surveyor-General in Sydney that ordered the setting out of a township as part of his survey, the intent of the party of three surveyors was surely to ‘lay out a town’ to establish civil authority, in preparation for land sales [

15] (p. 40). Russell had been placed under the direct instructions of the police magistrate Captain William Lonsdale, who understood the duties were for ‘immediate measurement of a portion of the district, a survey for measurement of the lands’ [

15] (p. 36). Furthermore, Sir Richard Bourke (Governor General) had reported that the surveyors had been dispatched to measure off sections and portions of the land for periodical sale [

15] (p. 37).

The township had most likely been plotted out following the instruction of Londsdale and under Russell’s supervision ‘on the very site occupied by the scattered huts formed the ‘un-named village’ of the original squatters’ [

15] (p. 41). Russell much latter made claim that he had made the survey of the site of Melbourne without official instruction [

15] (p. 43). The appearance of a dotted and numbered square grid on Russell’s feature map (

Figure 1), which had been sent to London to be lithographed, suggests a preliminary settlement configuration based on his knowledge of the standard plan in the Sydney office for laying out a new township, a copy of which he had in his possession [

15] (p. 47) [

17]. Critically, the map is a record of detailed landscape features which are meticulously recorded from which the following aspects are illustrated and written:

Yarra Yarra River, Falls, Fresh Water above the Falls, Batman Hill and Burial Hill (remains of early settlers and the site of a signal station) [

19] (p. 79), areas of Tea Tree Shrubs, Salt Lake, ‘Flat’ terrain, various tracks and lightly wooded areas. Additionally, homesteads are drawn and labelled with the family names of the settlers and officials [

18].

The site for the town is on the banks of the

Yarra Yarra River, a few kilometres upstream from the large sheltered bay of Port Phillip. The advantages of this selected site were many. In the 1830s and early 1840s, at the time of British arrival, the water of

Birrarang (

Yarra Yarra) were home to fish of all sorts and even dolphins. The waters coursed through low, marshy flats, densely grown with reeds and scrub, whilst on both sides of the river immense cordons of she-oak, gums and wattles tree forests grew. Headed into the river from the bay, saltwater mangrove swamps once spread. Beyond this, stretching as far as the eye could see, were rolling pastures covered with native grasses [

20].

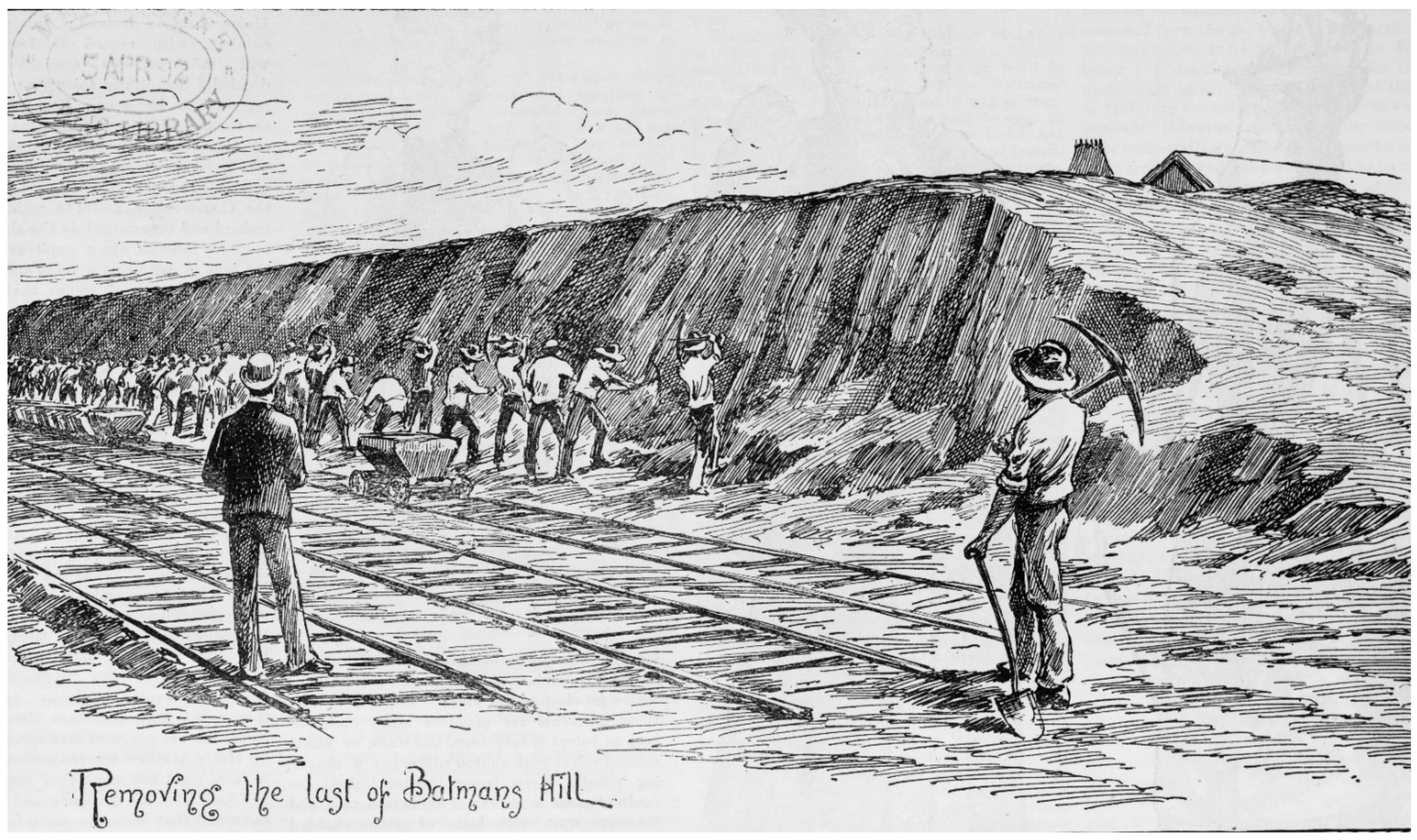

Four kilometres from the mouth, another river enters from the right. It is this river that British settlers first called Freshwater, before being given the name

Yarra Yarra, in the mistaken belief that that was the name for the stream, in fact it was called

Bay-ray-rung. The river then curves around a once prominent hill that was to be known as Batman’s Hill. This hill had a natural covering of she-oak and grass. About one and a half kilometres further upstream, on the northern side were the tops of hills covered with gums [

11]. East of Batman’s Hill the river originally formed a natural basin, wide and deep, and become known as ‘The Pond’. Immediately beyond the ‘The Pond’ was a set of rock falls consisting of a row of basalt boulders (The Falls) which formed rapids and retarded the spread of salt water further upstream. The

Yarra Yarra River was therefore a freshwater stream beyond this point. It was the main source of drinking water until it becomes polluted [

20]. Generally, the original vegetation comprised of tall and mature eucalyptus on both sides. In some areas there are trees that bear scars which show where bark has been removed by the local Aboriginal people [

11].

Progress of Russell’s work had been slow as he was hindered by several mitigating factors. Despite these claims, there was doubt as to his ability and efficiency in the task, and subsequently Bourke summoned from Sydney the Senior Surveyor Robert Hoddle to accompany him on an official visit to the settlement in February 1837 [

16,

21], to directly oversee the prompt implementation of a town layout. It is Bourke who officially confirmed the suitability of the area selected by Batman and the other first settlers as siting for a new town to which he named Melbourne [

22] (p. 219) [

23] (p. 94). ‘Hoddle was ordered to go over afresh the ground already marked out by Russell’ [

15] (p. 46), and lay out a central grid [

21] (p. 24). Bourke ‘fixed the limits of the town, and the direction of the streets’ [

23] (p. 89), to which he also affixed European names [

17] (p. 56). Only the

Yarra Yarra River retained an Indigenous Australian reference on the official first map of Melbourne. It is noted that Hoddle, overseeing the management of Melbourne’s immediate expansion, named many early suburbs with local Indigenous Australian names, for example:

Prahran,

Tukulreen,

Jika Jika and

Borondarra [

23].

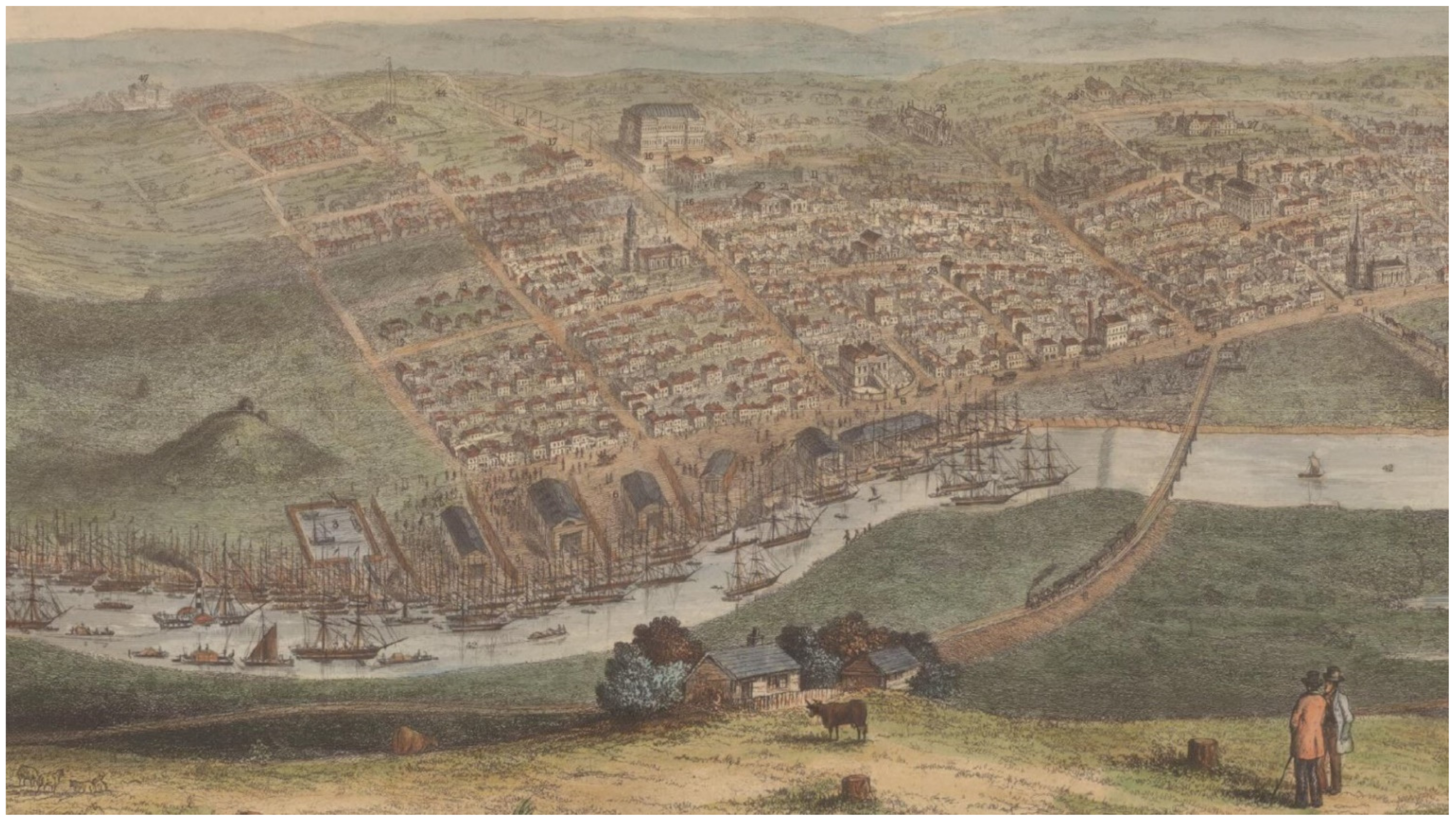

Therefore, as Melbourne’s first Surveyor general, Robert Hoddle confirmed the settlement grid with the alignment of streets and subdivision of allotments within the street blocks. The Melbourne layout is indeed unique mainly for ‘the “little” streets that were placed between the city’s cross avenues to allow ease of rear access’ [

7] (p. 18). Hoddle authored a map ‘Town of Melbourne’ (dated 25 March 1837) for the intention of the first land sales [

17], which shows the positioning of the grids aligning with the reach of the

Yarra Yarra River and extremity of Salt Water terminating in the natural falls, and offset from the protrusion of Batman’s Hill, from which there is a settling out line (

Figure 2). The river and hill are the only landscape features recorded on this map. The grid was apparently ‘superimposed onto the land with no consideration for the natural features of the site’ [

7] (p. 11).

Hoddle subsequently gained popular recognition and attribution for making the first plan of Melbourne [

17] with oversight to Russell’s earlier work perhaps as a consequence for his perceived unsatisfactory progress [

15]. The pervasive narrative being that Russell had made a topographical features survey of the ‘ultimate site of Melbourne upon which Hoddle subsequently drew the familiar grid plan’ [

16] (p. 9), and whom designed the layout of streets and allotments for the new town [

17]. Hoddle’s letter (10 April 1837) states ‘from Mr Russell I could only obtain a plan of the settlement executed by himself and Mr D’Arcy on which I drew a plan of the town of Melbourne’ [

17] (p. 57).

Figure 3 is the superimposition, Hoddle’s arrangement of named streets and numbered allotments overlaid onto Russell’s landscape features survey.

Despite this debate, our interest is in a reading of the two maps as being:

Figure 1, Russell’s map of extensive detail of landscape features, onto which the township is lightly indicated, and,

Figure 2, Hoddle’s map which conversely sets out a settlement geometry in bold lines, with only Batman’s Hill and the

Yarra Yarra River with Falls as topographic features to aid the positioning of the grid. ‘The old falls on the Yarra really determined the position of the city’ [

15] (p. 47). Yet, these were to be the prominent landscape features that would be expendable in the execution of infrastructural development of the fledgling town. A further collective understanding of the three maps is that they can all be viewed as instruments of power in the process of colonisation and dispossession, a theme which will be explored further in the next section.

4. Unwitting Evidence within Maps as Instruments of Power

Michel de Certeau’s idea that maps are an instrument of power represents a very important set of thoughts and way of thinking about maps that has subsequently been taken up by architectural thinkers [

26,

27]. In his seminal work

The Practice of Everyday Life, de Certeau talks about maps as instruments of power because maps centre power in place and implement a geometric schema for understanding space [

28] (p. 124). Relating this understanding to the context of maps during colonization makes evident that the survey of the land was a way of appropriating the land. Speculation inherent in the map or plan was perceived as a constructed future superimposed onto the existing land, altering both its physical and socio-cultural topography [

27]. The map materialises that speculation, and makes it more real than perhaps the intention because the map draws the vision in a pragmatic sense. The map thus pre-empts the change, alteration and transformation in relation to an existing reality. The map operates in a dual sense as projection of a yet unrealized future and as a representation of existing realities, and the cartographic or visual tools and methods tend to delineate what is drawn and what is not represented [

29]. As a method of a projected future on the surveyed environment the map surpasses the moment of that reality and shapes forthcoming realities. Maps and cartography, like land surveys, are not neutral.

The end result is a record of a spatial environment upon which is a manifestation of time: time and the historical moment are frozen within the paradigm of a map, disclosing a spatial environment distinct from the flow of time and a sense of the unknown of what was to come. Colonial appropriation thus occurs across both space and time as axis but also as intersecting forces. For example, a map may represent a grid (even though this is something that does not yet exist in the early 1800s in Melbourne) but not necessarily the pathways or sites of inhabitation of the Indigenous peoples. From this perspective we can see that maps were integral to the larger scope of colonization as an appropriation of territory and as selective representation of realities [

27]. Maps delineated the spatial order about the future of society. These were visions that projected onto particular sites and both imagined and articulated a transformation of that site into place. The maps of Russell and Hoddle actually determined a particular future for the site as a place for the city of Melbourne.

De Certeau discusses maps as instruments of power that produce regimes of place. Investment through the process of mapping and cartography constructs the place in question into a node or centre, and this action is not neutral but a determined strategy of colonial power. De Certeau connects spatial strategy, with maps and with place such that these three elements go together, and are organized in such ways as centres of authority and the law [

28] (pp. 34–44). In that sense politics does not exist outside of maps, and colonization cannot exist without mapping. The map is a critical instrument and a tool deployed to deliver the strategies and processes. Important to de Certeau’s theory is the contrasting of place and space. While the regimes of place are produced by maps and strategy, and they become strategic places of authority and power, so place is linked to authority power, law and strategy.

Space, in de Certeau’s theory, is a loosened activity. Space is not unmapped, but it is not strategic to the map, and difficult to map, and historically it is much less mapped in official documents [

28] (pp. 115–120). For example, one can imagine a picture (drawings, paintings) and this is also shown in early colonial photographs, of the co-existence of the Indigenous people within the ‘places’ established in the early times of colonization [

30]. They co-existed within the places in a way that de Certeau calls tactic, whereby, the Indigenous people navigated the then newly imposed spatial order of the place and the strategic order of laws, boundaries and structures (

Figure 4). Indigenous ‘tactical’ coexistence within these regimes of place was not represented on the official maps, or was officially omitted from the mapping of the place. Tactic is linked to what de Certeau defines as space, spatial co-existences that are interwoven within place. From this perspective a tactic can be considered ‘out of place,’ and that is exactly de Certeau’s point, that these are spatial navigations within the regime of place which use that place differently to its intention.

The intention of the colonisers’ settlement did not account for the co-existence, and in addition, the customs and activities of the Indigenous people. On the one hand, maps are instruments of power used to produce places that are strategic for the political intention and agenda, and in this case settler colonization. On the other hand, activities that do not fit into the scope or colonial vision of maps, and a regime of place as strategy, are those tactics and spaces that are temporal ‘actions of the weak’ [

28] (pp. xvii and 119). Importantly, such tactics, de Certeau argues, can redefine place temporarily as a very different space [

28] (p. 37). This presents a potential of the spatial realm that is outside the gaze and power of the regime of place. Within the first few years of settlement, Aboriginal peoples were almost entirely displaced from the Melbourne area [

22]. Nonetheless many Indigenous communities and individuals also co-existed within the same spatial environments, navigating the implanted order, authority and strategy of the newly constructed place. Therefore, ‘continuing aspects of Aboriginal cultures with expressions in values of place have persisted… and evolved through many transformations and adaptions until the present day’ [

32] (p. 1).

Russell’s maps and painting represent the concerted efforts of a landscape surveyor to record the extant condition around the site of colonial settlement. They are also artefacts of historical time—capturing the ‘lie of the land’ as it was perceived and recorded by Russell in 1837. In this sense, and for architectural historians/archaeologists, such documents can serve as evidence for other readings of history making.

Figure 4 depicts the Indigenous people crossing the

Yarra Yarra River at the point of the falls, continuing a time- honoured act of daily life within the fledgling surroundings of occupation. Within a short space of time, such landscape features will be irrevocably decimated in service of the rapid construction of colony. This painting is therefore a record of a ‘tactic’ in de Certeau’s sense of the division between strategy and tactic. It captures firstly the extant co-existence of Indigenous communities within the scope of colonizing instruments of documentation and representation. Secondly, it illustrates a site that has been identified as significant for the Indigenous communities of the

Bun Wurrung and

Woi Wurrung peoples of the area [

11]. A third aspect is that it indicates that indigenous presence, both—the act of indigenous people crossing and the site of the falls—co-exists as tactical non-strategic space within the regime of place that materialised as the new grid of Melbourne.

Therefore, it is possible to compare the two maps allocated as Russell’s map against Hoddle’s map (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2) by identifying the prominent landscape features as a significant part of Russell’s map that are suppressed within Hoddle’s, to the extent that only the river and hill were recorded as a reference point for the positioning of the grid. Russell’s map is an active intention and illustrates a comprehensive, observational and detailed approach in its record of the existing terrain and vegetation as necessary for its role in surveying the terrain for colonisation. Yet, it is an inadvertent record of Aboriginal

Country, an unwitting record of features of local places that (we now know) are significant to Indigenous history and therefore critically evidence that it was un-ceded colonization, and that the establishment of colony was not terra nullius, as was claimed by the colonisers. Hoddle’s map is the intent and blueprint for radical change. Between the two maps is a decision to omit these landscape sites in the transfer from an observational map of the land (Russell’s map) to the next level of the map as strategy. It is one in a series of procedures that determine the power and authority of the colony. Such map redrafting—and the imprecision of the transfer—illustrates how the determinants of the making of the colony are at work in this otherwise perceived empirical exercise. Maps are subjected to the cartographer’s gaze, and what the cartographer wants to see, in addition to the strategic and political objective. Hoddle’s map presents the erasure of sites of the land that belonged to the inhabitants of the land, drafting a contract of ‘wishful’ but colonial determined terra nullius. These maps were both created as instrument of power, but they can now be used against their intention as historical artefacts, that open up a different lens on the history of this place. We can now appraise the recorded lost landscape features, for example the

Yarra Yarra Falls and Batman’s Hill, evident in the archival settlement maps, and renew an understanding of their original significance.

6. Reparation through Design

We are becoming increasingly aware of the difficulty and continuing legacy of Australia’s history as a settler society… [that] occurred with minimal understanding of our environmental context and no knowledge of its prior occupation [

37] (p. 29).

Australia, as is the case with other colonised countries, is still in the process of coming to terms and re-examining the veracity of conventional accounts of its history, heritage and culture. Until relatively recently knowledge of a ‘pre-European history and ecology has been lacking’ [

37] (p. 30). Acts of reconciliation have included various political statements of recognition of past injustices and atrocities, in the form of formal apologies of the national government to the Indigenous Australians. However, the design professions and educational institutions have been slow to embrace momentum to affect significant change in current practice. New paradigms have nonetheless been provoked by several of Australia’s Indigenous architects.

Kevin O’Brien has developed a radical proposition called

Finding Country that emerged from his Masters of Philosophy thesis at the University of Queensland. A series of design studios have subsequently been undertaken where project participants are asked to execute the hypothetical removal of 50% of a selected urban grid. What follows is a contemplation of not what has been removed, but what can now be seen, an engagement with ‘a palimpsest to erase a certain part of the text of the city to reveal a presence that had been covered over and ignored’ [

38]. A negotiation is thus required with the lost landscapes of

Country before a new architectural insertion can be made. A tapestry map from a

Finding Country studio project was exhibited as a collateral event at the 2012 Venice Biennale, at which O’Brien ceremonially burnt the drawing ‘in an act of symbolic renewal and as a statement of positive intent’ [

38] in homage to the customary burning of landscape by Aboriginal people for renewed growth.

The Aboriginal map of Australia reveals a continent with many Countries and many spaces. The prevailing spectrum of architectural positions, bookended by decorated sheds and metaphysical decks, continues to bring Aboriginal Country into decline. If the opposite position is considered it is possible to find something lost. Cities historically enter states of decline, frequently associated with some form of catastrophe. Others end in a whimper. It is not unreasonable to imagine an opportunity for the recovery of Country through decline [

9].

Jefa Greenaway and colleagues Janet McGaw and Jillian Walliss have instigated a creative research student project at the University of Melbourne that engages with Indigenous place-making through three research methods of: Deep Listening, Mapping Place and Time and Critical Spatial Practices [

37]. The project re-examined Russell’s 1937 map (

Figure 1), and identified the several important places of cultural significance, including The Falls and Batman’s Hill. The outcome of the project was a number of creative works that included a spatial performance called

The Falls involving participants recreating a waterfall by pouring bottled water from a bridge at the location, a temporal recreation of the lost landscape feature. This work thus appropriates the maps as ‘informational tools’ of significant landscape sites which it then re-performs towards a communicative and community act, as a corporeal and signifying revision of historical erasure. Such use of maps may join methods of oral histories, and further archival historical documents, to build a very different map of the embedded memories of the sites the place of Melbourne.

O’Brien and Greenaway have been active in both private architectural practice while also formally appointed within leading Australian universities to advance critical thinking, research and teaching on the advancement of Indigenous agendas in architecture. Universities play a crucial role in accelerating awareness and change in society, in the context of applied research into Indigenous environments. Paul Memmott as an anthropologist and architect, for many decades has been instrumental in leading as Director The Aboriginal Environments Research Centre (AERC) at the University of Queensland [

39]. The centre has been responsible for extensive research projects and publication outputs. David Jones and colleagues [

14] have collated and published a comprehensive guide for tertiary educators that sets out a carefully researched and informed overview that includes: an understanding of

Country, protocols for respectful engagement with Indigenous issues, and introduction to Indigenous cultural heritage whereby ‘all tangible and intangible aspects of a landscape may be important…as comprising their ‘living heritage’ whereby the ‘spiritual relationship [with landscape] is an important aspect of Indigenous cultural heritage’ [

14] (p. 23).