Abstract

Interactive installations in museums usually adopt hybrid technologies that combine physical elements with digital content, and studies so far show that this approach enhances the interest and engagement of visitors compared to non-interactive media or purely digital environments. However, the design of such systems is complicated, as it involves a large number of stakeholders and specialists. Additionally, the functional components need to be carefully orchestrated to deliver a rich user experience. Thus, there is a need for further research on tools and methods that facilitate the process. In this paper we present the design and development of a mixed reality installation for the Museum of Marble Crafts in Tinos island in Greece, which places visitors in the role of the crane operator and they have to complete challenges in a gamified version of the old quarry. The system lets users operate a tangible controller and their actions are executed by digital workers in a rich 3D environment. Our design approach involved iterative prototyping, research and co-design activities. The creative process has been supported by a series of organized workshops. The evaluation results indicate that mixed reality can be a promising medium for rich interactive experiences in museums that combine tangible and intangible heritage.

1. Introduction

Recent trends in museums point towards smart exhibits and installations that efficiently combine digital content with physical form [1]. Interactive media alone have the capacity to enrich a museum visit with tailored information and edutaining activities, but they often distract visitors from the actual content, and instead of focusing on the exhibits people spend time looking at computer screens. On the other hand, the inanimate objects often accompanied by short scientific descriptions as found in a typical museum do not suffice to motivate and entertain visitors, especially those with little prior interest in the topic. Younger generations are much more exposed to rich media and interactive content and they seem to be expecting such stimuli in recreational and educational places like museums. A prominent approach to combine the advantages of both realms, physical and digital, is the development of systems that effectively hide digital technology in the physical exhibition and augment the space and objects with interactive audio-visual content. These systems are often called ‘hybrid’ or ‘phygital’ and they usually afford natural interactions such as tangible, mid-air, voice, augmented reality, etc. [2].

There have been plenty of hybrid approaches in the museums in the last decades, ranging from smart exhibits to sophisticated installations, with encouraging results. The early approaches were based on Radio-frequency identification (RFID) or similar tracking technologies to detect proximity between physical objects. Enhanced exhibits or replicas could ‘come to life’ if visitors touched them, moved them, or placed them in designated locations [3]. The previously ‘silent’ artifacts were transformed into smart objects that could tell their story, visualize context-sensitive information, or even be part of pervasive games, such as treasure hunt or role-playing [4,5]. As technology progressed, the possible systems and uses expanded exponentially. Nowadays visitors’ position and movement can be tracked with great accuracy allowing for playful bodily interactions [6,7], animated content is projected and mapped to any physical surface or even in the air as a pseudo-hologram [8], and modern microcontrollers and sensors offer new interactive capabilities to physical objects [9]. As a result, novel playful installations have been created, and visitors find themselves in mixed-reality spaces, where physical and digital interactions are efficiently coupled [10].

The design and development of hybrid museum installations poses several challenges [11]. First, the design space is vast including various technologies, interaction modalities, presentation techniques and motivating elements, and as such the resulting system configuration and approach are usually novel. It is difficult for a design team to find existing guidelines and paradigms from similar systems to shape their decisions. Second, the users and the context of use are also quite different compared to other interactive systems and applications. For most museum visitors the interface is novel, their previous experience with interactive environments may vary greatly, they usually spend only a few minutes using the installation, they will be probably interacting in a crowded and noisy environment being looked at by other visitors, and they will be possibly accompanied by friends or family. Third, the success of the installation cannot be ensured beforehand. The experience of the visitor is at the center of the design and there are no clear and measurable outcomes. Repeated prototyping, experimentation, and user testing are necessary during design and development to ensure that the end system will motivate visitors and evoke a satisfying experience. Finally, a lot of specialists from fields distant to each other are required to collaborate as a team and supervise several design aspects of the installation. These include museum curators, historians, usability experts, software developers, engineers, digital artists, and designers.

In this paper, we present the design and development of an interactive installation for the Museum of Marble Crafts in Tinos island in Greece1. The installation adopts a gamified approach to let visitors understand the basic mechanics, operation process and history of a crane for marble blocks that is physically exhibited in the museum entrance. Users take the role of the crane operator in the old quarries of Tinos and interact with a small-scale crane model in order to execute the tasks of carrying marble blocks from the extraction site to the dock and loading it on a small ship. The system offers a mixed reality experience, as the physical model mediates between the user and the virtual environment and maps her actions to respective crane operations. The installation is being developed following an iterative co-design approach that involves multiple specialists and emphasizes on user engagement, cultural presence and efficient integration into the museum visiting experience. At the time of writing this article, the system is near the final laboratory prototype. It is planned to be permanently installed in the museum within a period of six months after extensive testing and user evaluations in the laboratory.

The aim of the paper is two-fold. First, to introduce a novel approach for learning in a playful manner about the history and operation of a mechanical crane and the associated historical and cultural context. Second, to present and reflect on the collaborative process of designing and evaluating a hybrid museum installation, and to discuss the lessons learnt. The paper introduces the main concept of the installation and how it is expected to enhance visitor experience based on the needs and contents of the museum. Then, it outlines a generic process for developing mixed reality installations that emphasizes participatory design, and describes in detail how this process was applied in the case of our project. After that, we present the results of this process so far: the series of prototypes that have been created, the user and expert evaluations of the system in laboratory and in situ, and the issues and future considerations that have emerged. Finally, we reflect on our process and findings and present a discussion with more generic issues related to co-design of hybrid interactive systems for museums. This paper contributes to the fields of interaction design and digital heritage through the presentation of a novel mixed reality installation for museums, and the study of the participatory design process that we followed for its development.

2. Related Work

Smart artifacts and interactive installations in museums have evolved much in the last two decades in terms of technology and affordances. The idea of ‘hybrid’ museum artifacts combining physical and digital representations has been introduced by Bannon et al. [3], following the already established tendency of tangible Human-Computer Interaction [12]. The early approaches involved physical objects that responded to movement and triggered the reproduction of accompanying media, and floor projections that enhanced the space with digital content. Later works placed more emphasis on user interaction with tangible elements, where visitors could have an embodied engagement with the content in a more natural and meaningful way than with common touchscreen interfaces [13]. New sensor and projection technologies offered more possibilities for digital augmentation of objects, surfaces or spaces, enhancing the visiting experience with a personalized narrative, audiovisual content, tactile and even olfactory sensations [14]. In some cases, these installations afforded whole-body interactions that let visitors participate in mixed-reality worlds, collaborating with others, family members or even strangers, in an engaging and playful way [15]. Nowadays there is a wide variety of paradigms for interactive applications in museums and exhibitions that combine physical and digital representations and they have been termed as ‘phygital’ heritage [2].

Evidence so far indicates that hybrid systems and installations have obvious benefits for museum visitors. They offer a modern approach for communicating and learning about heritage that is more personalized and constructive. Whilst media alone can divert visitors’ attention from the content and isolates users, the use of hybrid installations can afford collaboration and enjoyment [16]. Museum visitors have diverse needs, background knowledge and preferences. There are people who prefer to interact with digital media, and others who focus on historic objects. However, a study found that the interactive hands-on exhibits of a museum managed to engage all kind of visitors, regardless their initial preference [17]. In another study [18] that compared a traditional touchscreen GUI to a tangible user interface for a museum installation, it has been found that the latter afforded better manipulation and was more successful at encouraging the initial visitor interaction that was necessary for their continued engagement. Finally, a study in a museum regarding the use of digitally enhanced replicas found that about 40% of the visitors used them without any prompting by the museum staff, and the percentage was much higher when they were actively prompted [19].

The development of hybrid installations for museums is a new territory for designers and cultural heritage professionals, and to date there are only a few guidelines and recommendations available. Hornecker and Stifter [17] suggested that the emphasis should be placed in designing experiences that afford real interactivity and personalized content. Other researchers studied how the setup of the space and exhibits can further motivate users and provided suggestions for optimizing the experience [20]. Ibrahim and Ali [21] named some factors important to consider when designing virtual environments for cultural heritage: information design, information presentation, navigation mechanism and environment settings. Pietroni [10] stressed out the need for better integration between real and virtual concepts and for combining different interaction paradigms, such as tangible interfaces and virtual reality. She pointed out the need to guide users through stories and motivating elements rather than letting them freely explore the contents, and she suggested that such systems should be designed for a heterogeneous audience.

Some researchers have also proposed more sophisticated models or frameworks for designing and developing interactive installations in museums. Hornecker and Buur [13] presented a framework structured around four themes that are not mutually exclusive and provide different perspectives to the design of tangible interfaces. The themes are: tangible manipulation, spatial interaction, embodied facilitation and expressive representation. Ciolfi and Bannon [1] proposed four dimensions that designers need to be aware of when designing interactive installations for museums, and for each of these she provided respective suggestions: physical and structural, personal, social and cultural. In another study, Dalsgaard et al. [22] emphasize user engagement with interactive installations and attempt to define the elements that shape such experience. These include the cultural conditions, the physical engagement, the content and the group interaction. Finally, Price et al. [23] present a framework that focuses on the relationship between the interactive artifact, the actions that the users perform, and the external object it represents. They present a number of parameters that affect the physical-digital mapping of the system: external representation, location of the physical and digital representations, dynamics, correspondence and modalities used.

Most researchers of the field highlight the need for close collaboration between multiple disciplines throughout the design and development of hybrid installations [24]. It has been proposed that this collaboration should be reinforced through the participation of the design team in carefully prepared design workshops, and it is important especially for cultural heritage professionals to be actively involved in the decision-making processes. Pietroni [10] described a collaborative design process consisting of: (a) an initial phase of discovery, where the design team understands the needs and constraints, (b) a creative phase where key ideas are implemented and tested and in some cases prototypes are evaluated in situ, and (c) the development phase that leads to the final installation for public use. Ciolfi et al. [25] have studied two alternative co-design approaches for museum installations. In the first one, the team was working with an open brief, and the emphasis was on ideas rather than requirements. In the second, the design started from an existing functional prototype, which then led to a scenario and shaped the content and the final form and functionality of the exhibit. It has been found that prototypes set boundaries on design ideas, but they provide a better understanding of how technology works and can then be integrated within a design scenario. In another study, Cesario et al. [26] prepared and studied a co-design activity that was more participatory and was mostly led by end-users. A group of teenagers together with the researcher jointly designed, created and evaluated medium-fidelity prototype games for a museum using augmented reality technology.

The early involvement of non-technical staff, such as museum experts and end-users in design activities is so important for the final outcome that some researchers pointed out the need for easy-to-use tools to conceive, design and make interactive artifacts [16]. Two such tools have been presented so far; one is for tagging physical objects and associating them with digital content [27] and another for synchronizing the behavior of smart devices through a visual interface for non-programmers [28]. However, to date there are no generic tools available that can cover a wide range of interfaces and system configurations such as the ones seen in modern museum installations.

3. A Crane Operation Game for Museum Visitors

The Museum of Marble Crafts is located at Pyrgos, a settlement on the island of Tinos, Greece, where the involvement of the inhabitants with marble crafts has created a unique artistic culture and raised some of the greatest Greek artists. The museum exhibits the Tinian marble craftsmanship, inscribed at the Representative List of Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity (UNESCO). Its scope is not only to present the developed technology and expertise around Tinian marble but also to inform visitors about the social and economic context from which the craftspeople advanced their professions and workshops, contributing to the cultural legacy and the overall image of their place.

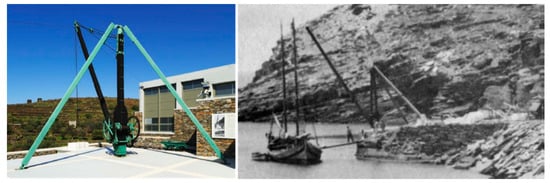

A marble lifting machine (crane) dominates the entrance of the museum (Figure 1, left) and arouses the interest of visitors at the beginning of their visit. This pre-industrial crane, known as “biga”, had a pivotal role in the mining business; it belonged to the “Karageorgis company at Vathi”, a quarry located at the north-west coast of the island. The company employed up to 70 workers from the surrounding villages and spread across the main quarry’s springs and its port. The crane’s use was inside the quarry, where a railway wagon loaded large blocks of marble to carriage at the dock. Another crane was at the quarry’s port, where the blocks were loaded on boats for transport to other parts of Greece and the Mediterranean (Figure 1 right). Five to seven people controlled the crane: one person that overviewed the process and signaled the workers accordingly, two workers were operating the machinery and another small group of workers that tied and untied the volumes of marble on the crane’s hook and guided the blocks’ lifting and landing.

Figure 1.

(Left) The crane at the entrance of the Museum of Marble Crafts, Tinos. (Right) The crane at the quarry’s dock, Vathi, Tinos. © Piraeus Bank Group Cultural Foundation.

The crane at the entrance of the museum is a striking piece of machinery that attracts visitors. Still, they do not actually get to know much about its functionality and the way it has been operated in the past. It is the first object that visitors face in the museum, and some of them would probably like to see it in motion or even rotate the crank themselves; however, neither of these is possible at the moment. When visitors enter the museum interior and reach the section related to the quarry mining business, they can then notice that the crane had a central role there. A 2D animated video illustrates the process from marble extraction in the quarry to loading it on the boat. Although the video is explanatory, it only showcases the stages of the process in an abstract way. The workings of the machine, the coordination of the people that operated it, the difficulty and the risks of its usage remain hidden.

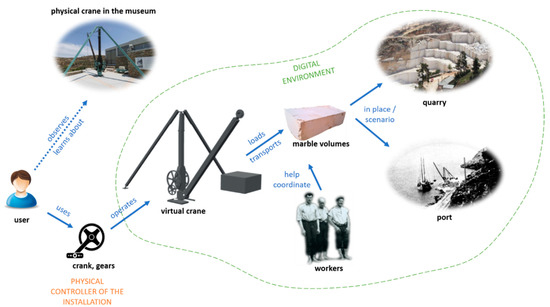

Our interactive installation attempts to fill this gap by providing a gamified environment, where visitors adopt the role of a crane operator and direct the block lifting process themselves. It consists of a simplified physical model of the crane in smaller scale and a large screen projecting a digitally recreated environment of the old quarry. The small-scale crane, which we will refer to as the ‘controller’, is used as an input mechanism for the installation. Visitors manipulate the tangible elements (gears, cranks, ropes) of the controller, that are abstractions of the functional parts of the real crane, and their actions are instantly translated into respective avatar movements in the digital environment. Additionally, the controller as a physical object demonstrates the basic workings of the crane as it embeds part of its functionality; when a user is rotating the crank, the main gears are rotating accordingly, and when she switches gears, the impact in the gear rotations is also observable2. The installation aims to virtually place visitors in the actual working conditions happening inside the mining-business, transcending them to the cultural environment of the corresponding era. Intangible aspects of the working culture of Tinian craftspeople, such as clothing and food, communicational patterns, working spaces, roles and hierarchies. will be revealed to the visitor in an interactive and engaging way. Figure 2 presents a concept diagram of the installation.

Figure 2.

A concept diagram of the interactive installation for the Museum of Marble Crafts.

The installation adopts a gamified stance and poses two challenges with increasing difficulty for the users. Initially, it introduces them to a simplified game-like representation of the environment of the old company and asks them to learn the workings of the crane and assist its operation. The story consists of two scenarios (stages), which communicate the actual way of using the crane in the past. The first one is taking place inside the quarry, and the second one at the quarry’s dock. Both scenarios involve workers in the form of digital characters who ‘collaborate’ with the user and guide the process. A virtual signaler gives appropriate signals for the rotation of the crane and the movement of the central needle during the uploading and downloading of the volumes; two virtual workers operate the crank and the ropes of the crane, and two other tie and loosen the volumes when needed. The main challenge for the user is to understand the role of forces, pendulum, and weight, as presented through game mechanics inside the digital environment. Simulated dynamics, concerning the attachment of volumes to a crane, and the physical constraints created when operating such systems (crane-load bearing) are also essential to gain knowledge of the dangerous working conditions at the quarry. At the same time, the user is introduced to intangible historical data, assuming the role of the operator of the crane in a parallel consultation and collaboration with (digital) co-workers of that time.

4. Collaborative Design and Development Process

We adopted a collaborative, participatory and iterative design and development process for the creation of the interactive installation for the Museum of Marble Crafts. The process draws methods and tools from User-Centered Design [29], Co-Design [30] and User Experience Design [31]. It focuses on the early involvement of stakeholders and end-users, and aims to deliver a final system that is engaging for visitors, communicates aspects of tangible and intangible heritage that complement the physical exhibition, and fits well in the museum’s space.

4.1. Overview

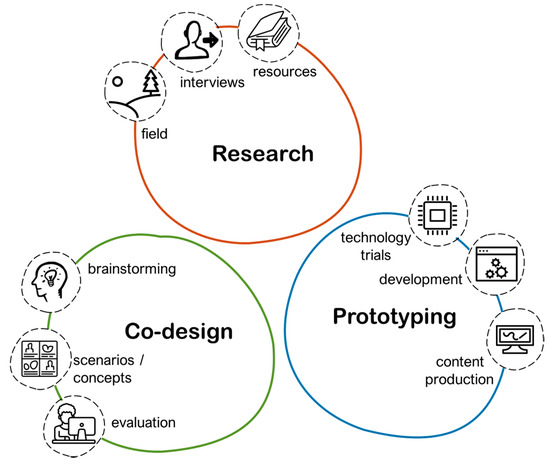

The process consists of three basic activities that are iteratively revisited or sometimes executed in parallel throughout the design and development of the project. These are research, prototyping and co-design (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

An overview of the collaborative design and development process.

The research activities aim to collect resources and requirements that will guide the design of the system. This stage is critical for the success of the installation as it ensures that the content delivered to the visitors is appropriate, valid and historically accurate, and well adapted to the vision and goals of the museum. During research, aspects of both tangible and intangible heritage need to be carefully collected and examined, as they need to be used for the preparation of the digital content and the physical parts with which the visitors will be engaged. The research stage involves:

- measurements and tests in the field,

- interviews with locals and experts, and

- collection and analysis of existing resources.

In the prototyping stage the artists and developers of the team transform the concepts and ideas into functional solutions. As noted by various researchers of the field (e.g., [24,25,27]), the rapid production of prototypes from the early stages of design is important for the success of the system under development. Prototypes are not only important as a means to evaluate the concept and ensure that the system under design will deliver an engaging experience; they also serve as a basis for producing further ideas and enhanced scenarios [24]. Given the large design space and possible combinations of interfaces and paradigms, the development team may have to test and compare various technological approaches and ensure that the adopted solution achieves the desired performance. Furthermore, they need to produce and update both the contents and the functionality of the prototype to ensure that it reflects the latest design decisions of the team. The prototyping stage involves:

- technology trials and tests,

- application development, and

- content production.

Finally, the co-design activities orchestrate the creation process and ensure that the system satisfies its requirements and goals throughout its development. These activities require the participation of all possible stakeholders and experts in order to evaluate the prototypes, generate ideas, and refine the concepts and scenarios regarding the installation. The team collaboration is taking place asynchronously during the whole creative phase of the project. Additionally, in specific milestones that are critical for the project development, special workshops are organized for synchronous team collaboration in situ, where prototypes are tested, further ideas are generated, and alternative configurations are discussed. The co-design activities mainly consist of:

- brainstorming and bodystorming,

- refinement of concept and scenarios, and

- evaluation of prototypes.

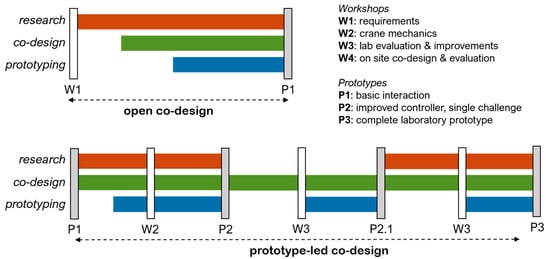

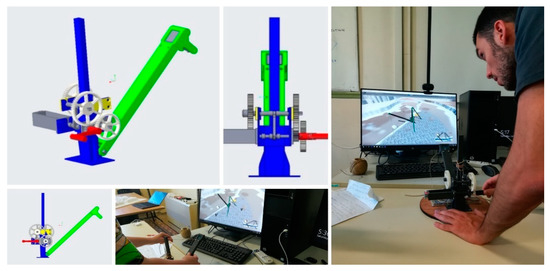

4.2. Application of the Process in the Project

The design and development process of our interactive installation went through two generic phases. Initially, the team followed an open co-design stance. The goal was to come up with a concept of an interactive installation for engaging museum visitors that would be well aligned to the existing collection and would highlight aspects of intangible heritage related to marble crafts. In this phase, we organized an initial workshop for collecting requirements and understanding the needs of the museum and its visitors, formed the main concept of the interactive crane game, and developed the first prototype with physical and digital elements but little interactivity. Then, the team went into the second phase, the prototype-led co-design. The demonstration of an initial, low-fidelity version of the system through the prototype triggered new ideas and more active participation of the cultural heritage professionals. This led to a second workshop for researching and studying the workings of the crane, and to the development of a second prototype with a more sophisticated physical controller and a digital environment that supported the main tasks of crane operation. A third workshop has been organized to evaluate and refine the prototype with the involvement of end-users for a first formative evaluation in the laboratory. Finally, a two-day workshop has been organized in the museum, where further research, brainstorming and in situ evaluation with visitors and experts took place. The main phases and milestones of the process are depicted in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

The main phases and milestones of the design and development process so far.

In the following subsections we describe in more detail the research, prototyping and co-design activities that have been executed for the design of the installation so far.

4.2.1. Research Activities

The research activities were intense and almost continuous throughout the development of the project so far. Initially, we had to understand and identify the museum needs and goals. For this, we needed to study the collection carefully, to discuss with the curators and personnel, to observe the visitors’ behavior, etc. Besides the content being exhibited, we had also to understand the intangible heritage of marble crafts and the underlying context of the extraction and creation process. Then, when the crane was decided to be the main subject of the installation, we had to shift our attention to the machine and focus on its workings; how it operated, what are its basic parts and how they interact together. After that, we had to gather material and learn about the general operation of the quarry and the organization of work. Who were the people working with the crane, how did they collaborate, what did they look like, what their clothes were, the relationships between them, were some of the questions we sought to answer. Next, when the game concept and content had been decided, we had to focus even deeper to refine aspects of the content, such as the scenery, the background elements, the character animations, the soundscape and the dialogues. We needed to find out hints regarding the buildings and roles of all people in the quarry and port, the workers’ position and movements when operating the crane, the typical signals and dialogues between them, etc. Finally, we had to research further into the physics of the crane, as we decided to provide in-game visualizations regarding tension, moment and torque on the crane’s parts to help users avoid accidents.

For these research activities we employed a number of methods. We collected and studied related resources, such as documents, books and old photos related to the quarry and the marble extraction process. We took interviews from curators, cultural heritage professionals, craftsmen and seniors that have worked there in the past. In the interviews we tried to uncover aspects that were blurry in the saved resources, usually related to the working culture of the times or to specific details of the workers’ activities and their coordination. Given the subjectivity of the personal testimonies that we recorded, we tried to go through and verify the answers with experts of related fields. Field inspection and trials was another set of activities that we frequently performed during the development of the project. We needed to inspect the quarry and operate the crane ourselves, in order to have an experiential understanding of the workers’ positions, movement, field of view and communications, and be able to test our scenarios.

4.2.2. Prototyping Activities

The prototyping activities were critical for the success of the project. Our concept for the installation includes some innovative aspects in terms of interaction design and interface and blends various technologies. As such, we had to develop and evaluate our ideas from the early phases to test whether the system architecture and the technology employed were mature enough to deliver engaging results.

Given this, we underwent several technology trials, building throwaway prototypes that tested one or more aspects related to the system performance. We examined appropriate materials and functional parts of the controller, so that its final form and structure is suitable for showcasing the workings of the crane, and also serves as a usable and intuitive input mechanism for the installation. We tried and tested several candidate sensors and microcontrollers to come up to a system architecture for the controller that could operate smoothly and deliver the needed precision. Finally, we performed tests regarding the communication protocol between the controller and the main application that produced the virtual environment, as well as the capacity of the environment itself to support a large scene with animated characters at the desired quality. All these experimental setups and trials helped us make decisions on technical aspects of the installation.

Besides the technology trials, the prototyping mostly involved parallel sessions of development (coding), content production and engineering design of the controller (CAD). The developer encoded all the design decisions regarding the challenges and logic of the game into functional code; the artists modelled the scene, the objects and the characters, concretized and enriched the story and dialogs, and created the basic animations; the engineers designed and tested the 3D printed parts based on the usage requirements and the needed placeholders for the sensors, and constructed the final form of the controllers. In many cases these activities raised the need for further research and triggered targeted research activities to answer specific questions. Typical examples of this are: to understand the proper positioning and movement of the characters, to describe the gear functions in more detail, and to learn more about the communication signals between the workers.

During the development of the project there was a need for rapid prototyping. This was necessary to be able to test and evaluate new ideas that would help the design team to refine or adjust the concept. Thus, in various cases, we had to quickly adapt and integrate the different parts (code, content and controller) into a functional prototype. The prototypes proved vital in the meetings of the design team. In one case we decided to build an ‘adaptive’ prototype, i.e., not have the functionality fully fixed, but provide alternative configurations to be tested and discussed. A drawback of rapid prototyping was that the code and scene were sometimes quickly developed and thus not as ‘polished’ as they should be. Then, extra effort was needed to edit the code and assets as required and transform them into a neat, well-organized and extensible project.

4.2.3. Co-Design Activities

The co-design process involved larger groups or even the whole design team and was manifested through activities that: (a) added new content and functionality, (b) refined the concept, and (c) evaluated the functional prototype. The expansion of the content was based on brainstorming that took place during synchronous meetings (remote or face-to-face) of the team, and also on the preparation of detailed scripts and scenarios that were prepared by the designers. As stated before, the existence of a functional prototype speeded up the brainstorming sessions and allowed participants to have a more concrete understanding of the capabilities and limitations of technology; thus, they were able to propose modifications and extensions that were mostly feasible. Furthermore, the design team, and especially the cultural heritage professionals, were asked to read and revise the documented ideas, scripts and dialogues, to refine and update them, where needed. Alternative configurations and solutions were also presented to the team by the designers, and each member could test them on the prototype and evaluate them. Finally, we organized formal or semi-formal evaluations of the prototypes both in the laboratory and the museum and had users and experts try, test and rate the system. Their comments were valuable for the refinement and improvement of our concepts.

In the design and evaluation activities of the project, we focused on a range of different aspects. First of all, it was necessary to ensure the validity of the content with the help of the experts. The content, in contrast to other forms of media, was not easy to isolate from the application. It included the forms of objects, the physique and clothing of characters, the dialogues, the activities, etc. Then, we focused on the usability of the installation, which is necessary for its success. We researched and adopted related usability guidelines for 3D environments and tangible interfaces in our design, but it was also necessary to evaluate the prototypes with indicative users and measure quantitative and qualitative data to detect any critical usability problems from the early phases. Besides that, we also needed to evaluate the playfulness of the installation, because the final system should be presented as a game to the visitors and should be fun to interact with. Thus, we tried to add playful and gameful elements to the installation and, again, had to evaluate them with user studies. Another important aspect was the aesthetics of the system. Both the controller and the digital scene should be presented in a form that is consistent with the appearance and style of the exhibition in the museum, so we needed to have constant feedback by the curators and museum staff. Finally, the place where the system is planned to be installed is also critical for the design of the experience, so our design decisions were also affected by that. The users’ standing position, the distance between the viewer and the screen, and the place’s capacity to support multiple viewers were factors that led to decisions regarding the controller form and size, the support of multiple players, the viewport and size of the virtual elements, etc.

Finally, the organized workshops played a fundamental role in the co-design activities and accelerated the development process. They triggered the active involvement of the project’s members and the museum’s staff in offering multiple views and considerations concerning aesthetic, functional, cultural, and educational aspects related to the interactive system. Meeting together ‘in the field’ was necessary to review issues related to the real crane (exact measurements and motion study), the museum site (the installation’s placement and interaction style), and the visitors (their experience while interacting with the installation and connection with their overall museum visit). It further allowed us to discuss and evaluate new ideas or alternatives through ‘bodystorming’, i.e., testing the installation in its real place and performing tangible interactions as if it was fully functional.

5. Results and Future Steps

The design and development process followed so far has produced fruitful results. We have developed a series of intermediate prototypes, run two evaluations with prospective users (one in the laboratory and one on-site) and a third one with experts that shed light into various aspects of the design, and our co-design workshops led to important considerations and decisions regarding the project.

5.1. Evolution of Prototypes

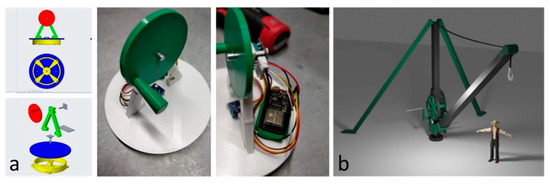

The strategy we adopted for our prototypes was to start from the main user interaction and then extend the functionality and improve the form to add more details. The emphasis of the installation is on the user experience and the highlights for the users are the tangible interface and the kinesthetic interaction with the environment that mimics the real operation of the crane. Therefore, we decided to create our first prototype to do just that; to operate a digital crane with a tangible interface (Figure 5). We designed the first form of the controller so as to support the rotational movement of the crank plus a simple rotation on the vertical axis. Respectively, the 3D environment only showed the digital version of the crane with a marble volume tied to it. Therefore, the goal was to focus on the experience, to adjust and ‘polish’ the system as needed to make the interaction more natural, playful and enjoyable. We had to informally evaluate the prototype and get more opinions about the interaction and the feeling of control it gave the users, to proceed with the design. Given the simplicity of the controller and digital environment, this first version of the system was actually a throw-away prototype.

Figure 5.

(a) First lo-fi (throwaway) prototype representing the basic functionality parts of the crane. (b) A close-to-final version of the visual design of the virtual crane and characters.

The next step was to create a more detailed, re-designed interactive prototype with an improved controller and an environment that presents the basic scene and challenge. Based on the results of the first prototype, we decided to improve the controller and add more elements that resemble the real crane. Our design choice was to make the controller look more like a miniature crane and thus have an educational purpose besides its interaction affordances. Users should be able to identify the main elements of the crane in the controller and some of them should be actually operating, i.e., multiple gears rotating, while the user is turning the crank. The prototype controller had much more functional parts compared to its first version and had to be printed and tested several times before the prototype was actually released (Figure 6). It has also been decided that users would be able to perform three independent actions using the controller: to turn the crank, to rotate the boom by pulling lateral ropes and to switch gears. The gear switching changes the functionality of crank rotation between rotating the boom and raising/lowering the hook. The 3D scene and the crane operation in the virtual environment have also been significantly expanded. The scene presented a large part of the quarry, digital characters operated the crank and pulled the ropes, and a marble volume could be tied and untied to the crane. The first gameful elements have been added to this prototype. Users had to perform a specific task: to transfer a marble volume from its original position to a designated target spot. To do that, they had to perform a series of actions on the crane, following orders sent by the system.

Figure 6.

Second lo-fi prototype with the addition of the boom (green), central axis (blue), ropes, and look and feel gears (white), and screenshots.

The second prototype has been evaluated by nine (9) users in the laboratory and revealed some elements that needed to be improved, mostly regarding the visual feedback and the general system response to user actions. This led to a third, updated version of the prototype that was based on the same controller and virtual environment but had additions and improvements in the user interface (visuals and sounds) and the game logic. The improved prototype has been evaluated again by eleven (11) users and did indeed increase user satisfaction and engagement. The process and results of the aforementioned evaluations are presented in detail in the following subsection (Formative Evaluations).

Finally, we are in the process of creating the full scene in high detail, which includes both the dock and the quarry and to extend the game logic and interface to become a complete game (Figure 7). The controller will also be improved according to the evaluation results.

Figure 7.

Screenshot of the hi-fi prototype of the virtual environment of the phygital application, representing the second stage of the gamified application.

5.2. Formative Evaluations

The first formative evaluation of the second interactive prototype took place at the University’s Lab. A total of nine users (ages 22–42) took part in the process. Six (6) of the users were undergraduate students, where the other three (3) were a professional game reviewer, a graduate student and a doctoral graduate of the Department of Design Engineering. The scope of the evaluation was to assess both the physical controller and the virtual environment in terms of usability, user experience and associated content. The methods used were observation, questionnaires, think-aloud protocol and semi-structured interviews. The user interaction and comments were recorded with a camera and audio recorder, and the evaluator also took notes of critical observations.

Initially, the users were given a questionnaire to fill basic demographic data (sex, age, previous experience with games) and the aims and process of our study was explained to them. Then, they were asked to freely interact with the system without any initial instructions given.

They had to find out what the controller is, how it works, and eventually operate it to complete the challenge presented to them in the digital environment. No time limit was given, but the main challenge lasted around five minutes on average. During their interaction we encouraged users to publicly express their thoughts and opinions, to help us gain more accurate feedback on how interaction looks and feels, and what drawbacks and misconceptions might arise while handling the controller.

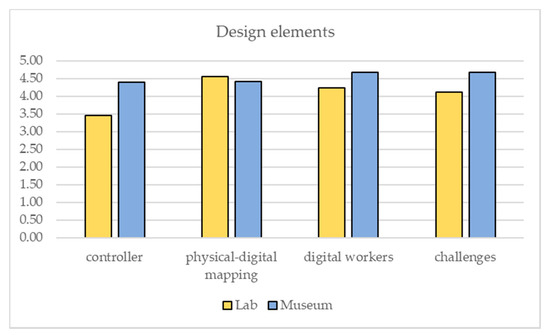

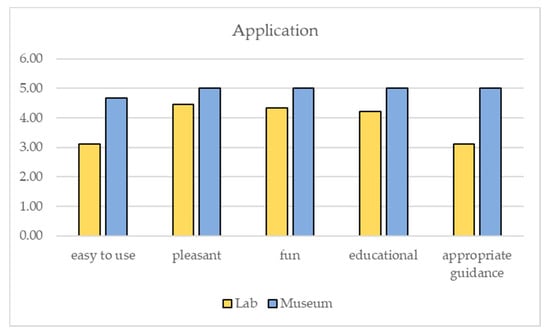

After that, all nine users filled a questionnaire about their overall experience. They had to rate the individual parts of the system using a 5-point Likert scale: the usability of the controller and its functional elements, the quality of mapping and correspondence between the physical controller and the digital crane, the look and movement of the digital workers in the 3D environment, and the quality of the challenge posed to them. Then, they had to rate the application in total and evaluate their experience using it. They were asked if it was easy to use, pleasant, fun, educational and if it provided appropriate guidance. Finally, they were asked about the learning content of the application. They had to rate it in terms of helping them understand: (a) the basic mechanics of the crane, (b) how the crane was used in the quarry, and (c) what was the role of the individual worker and how they cooperated together. The twenty-six questions of this questionnaire were grouped into three major categories according to the type of feedback given concerning the design elements, the application’s experience affordances, and the educational content (for a more detailed view, see Appendix A). Then, the main answers of each sub-category that provide an overall perspective regarding the three categories are presented in the following figures.

Finally, the users were interviewed in order to clarify whether they understood the basic method of operating the crane and if the virtual characters helped in conceiving both the use of the crane and the related historical and cultural context.

Users generally found the system interesting and they enjoyed using it. This is also reflected in their ratings (see Figure 8, Figure 9 and Figure 10 regarding Lab evaluation). However, findings from observation revealed some misconceptions regarding the use of the controller, at least without any prior instructions. A total of eight out of nine users intuitively rotated with the crank, although the initial challenge was to turn the crane by pulling the ropes. Users also anticipated the boom of the controller to be turning while pulling the ropes, which was not happening. Another issue was that the mechanism to switch gears was not easily noticeable. Only one user spotted that the crank could move along its horizontal axis, thus it could change position and enable the other pair of gears. Almost all users thought they could interact with some non-movable parts of the controller, such as twisting the central axis or pulling up and down the boom.

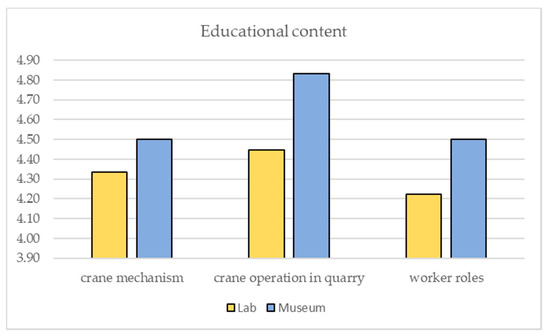

Figure 8.

User ratings of the individual design elements of the installation in the laboratory and on-site (museum) evaluation in 5-point Likert scale.

Figure 9.

User ratings of the of the application in the laboratory and on-site (museum) evaluation in 5-point Likert scale.

Figure 10.

User ratings of the of the educational content of the installation in the laboratory and on-site (museum) evaluation in 5-point Likert scale.

The interviews provided a more detailed analysis of the interaction with the controller and the application in general. After their interaction, almost all users understood how the crane is operating and what the purpose of every individual part is. As far as usability of the controller is concerned, some users asked that they would like a bigger crank. All participants stated that the haptic feedback during the interaction with the crank was pleasant, but they would not identify the switching between the pair of gears unless they had been told. Additionally, four out of nine said that the switching was difficult to be worked out. Users also noted that the low-poly characters were aesthetically pleasing, and their movements in the scenery facilitated the realization of the overall operation of the crane.

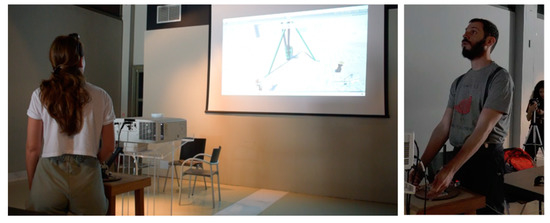

The second user evaluation took place in the Museum during the 2-day workshop. It followed the same process as the first one, but: (a) the location was the museum instead of the laboratory, so users were already familiar with the crane and the related context, and (b) they used the updated prototype, which had a number of improvements regarding the interface and feedback; the controller remained the same. Eleven (11) users participated in the evaluation of the prototype. Five of them were members of the design team, who had never interacted with the prototype before, and the remaining six were museum visitors, who have been asked to voluntarily use and evaluate our system. The evaluation did not take place in the designated location of the final installation, but in a multipurpose room of the museum next to the main exhibition (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Photos from the user evaluation of the installation in the museum.

The results of the two user evaluations in the laboratory and museum regarding individual design elements, the application in total and the educational content of the installation are presented in Figure 8, Figure 9 and Figure 10, respectively. It is evident that the rates in the museum evaluation were higher, especially with respect to their ability to understand the educational content. This difference is probably due to the fact that the application has been improved based on some usability issues found in the first evaluation, and also that being already in the museum and having seen the real crane, users were more aware of its role and usage.

The results from the questionnaires, comments and observations that we collected from the field evaluation indicate all users generally enjoyed the interaction with the system and the immediacy of the controller. Some users mentioned that they would like a better haptic response from the controller, e.g., to feel weight and resistance when a block of marble has to be lifted, or to have a better mapping between pulling the ropes in the controller and the actual task depicted by the workers. Another issue that arose in both evaluations, and is currently under re-design, is the sequential execution of tasks and its limited challenge. We noticed that when users managed to understand how the controller can be used and how their actions were transformed into crane operation, they knew well which movements they had to do to complete the challenge, and it resulted in a repeated execution, so their interest in the application was reduced.

Finally, we performed an expert evaluation of the interactive installation among the five (5) members of the project team, who were not involved in the prototype development. After using the prototype, they were asked to complete a supplementary questionnaire based on the framework of Goncalves et al. [32]. We adapted the framework selecting specific dimensions and revising their questions according to our needs and museum constraints. The participants had to rate the system and provide feedback based on the museum needs and requirements, concerning seven dimensions that guide the design and evaluation of interactive installations: interaction style adequacy, area of integration, visibility, feedback, structure and aesthetics, learning, entertainment (see Appendix B for the complete set of questions). The results are presented in Table 1. We interviewed each member and asked them to elaborate their ratings and comment on the ability of the prototype to satisfy each of these dimensions.

Table 1.

Results of the expert evaluation of the interactive installation based on the adaptation of the M-Dimensions framework [32].

The most important results from the expert evaluation were related to the final installation position of the prototype in the museum. Additionally, we discussed how the museum’s character and aesthetics affect to some extent the content of the application in terms of its playful or purely educational nature, the explanatory visualizations that will be shown, the participation of more than one player, and the final form and affordances of the controller. Based on the fact that the application is still in the prototype stage, we also received feedback on system feedback issues (identifiable information, change in system status, etc.), aesthetics and structure (familiar to the museum aesthetics, colors, etc.), learning and fun (search for new knowledge, relaxation, participation and social experience, etc.).

5.3. Considerations for the Future

The discussion and analysis of the evaluation results and the brainstorming that took place in the co-design workshops produced a number of topics for further consideration for the next steps of the project. These are:

- Linear vs. emergent progression of the game: initially the game followed a linear progress emphasizing on the correct sequence of steps to operate the crane. However, this limits the users’ sense of freedom in the environment and makes the whole activity less challenging. In contrast, if our system allows users to make mistakes and learn from them, the experience might be more exploratory and users might also have a better understanding of the engineering/physics aspects of crane operation and the risks of the work. Further user testing will be needed to explore this alternative.

- The form and operation of the controller: should the controller look and function like a miniature of the physical crane or should it be an abstraction of it? In the first case it will bear more details of the actual crane operation and possibly users will understand more about its working parts and how they coordinate together. However, a detailed model might act as an information overload for the user and it might distract her from the digital environment, where actions will be manifested. On the other hand, an abstraction could help highlight only the important parts that one needs to know and emphasize more on the physicality of the actions rather than the appearance.

- The balance between educational content and playful interface. In the first case, more emphasis is given to the environment, the costumes, the dialogues and in general the cultural elements that will accompany the application, while in the second case the design will focus on the challenges and the fun of the user, and even his friends and company.

- Enhancing the application with explanatory visualizations, e.g., auxiliary signs for understanding the interaction (what is the target, which part of the crane is about to move), or even physical forces and tendencies on the boom to make provide feedback about the risk of an accident. These visualizations support the challenges and make the user actions more predictive, but “break” the realism and should match the aesthetics of the environment and the style of application.

- The participation of more than one player. Given that museum visitors usually come in groups, we examined the idea of designing the controller in a way that it can be shared among two or more participants, e.g., one rotating the crank and another pulling the lateral ropes. We also considered the possibility of having two simultaneous users participate in the environment, one as the crane operator and another as the controller that provides signals to guide the process.

6. Discussion

The participatory co-design of the interactive installation for the Museum of Marble Crafts and our studies of the user experience with the prototypes so far has led to a number of observations. The most important of them are:

User engagement should be at the core of design. We found that the most important factor for the success of the system was the experience of the users during the interaction. Although the content, the aesthetics, the dialogues and the story all captured the users’ attention, what was found to be more important was the playfulness of the activity, the challenges it imposed, the kinesthetic interaction and the role-playing. Thus, it is critical to design the mixed reality experience in a way that it immerses the user, makes her feel that she is actively participating in the process, and provide an intuitive and playful interface to do that. Given that, it is important to start with prototypes that focus on the experience itself, rather than fill it with content and media from the very beginning. It should be first ensured that the physical and digital interactions operate smoothly and consistently, and then continue designing the shell of the system.

Create prototypes that are configurable and adaptable. Prototypes are a sound basis for discussion in co-design session, but as the discussions progress new ideas unfold. Thus, there is a need for easily adjusting prototypes to (partially) present these new ideas. In our workshops, we included various alternative views and options so that different configurations could be actively displayed and tested. This helped discussions a lot, as people could see their thoughts and concepts getting realized and instantly evaluate them. For example, we instantly tested different mappings between the controller and the actions of the workers in the digital environment. Should the workers respond immediately to user input, or should they first take the appropriate positions and operate in a more realistic and consistent way? Another example was to evaluate various alternative challenges for crane control by changing views, adding a secondary viewport or even adjusting the shadows. e.g., how well can the user view the position of the hook with respect to the marble volume? Will she have a direct view or will she need to focus on co-worker signals?

Prototype-based design facilitates brainstorming and enhanced participation. Although the open design approach [24] leaves room for more ideas and has a definitely larger design space, we noticed that the participation and collaboration of museum professionals were considerably weaker, compared to meetings with a prototype at hand. In the latter case the experts had a better understanding of the concept even with the first very simple prototype, and they started to have more fruitful ideas and contributions. As the fidelity of the prototypes increased, the contribution of curators and experts was more focused on details, proposing important historical or cultural aspects that could be added in the game. In some cases, they started to think more like end-users than stakeholders and they were engaged enough to propose new ideas regarding the interface and experience.

Analysis and research are needed even in later stages of development. From the development of the project it was evident that research and analysis activities were almost continuous. In our first steps we had to come up to an initial understanding of the crane, the activities in the quarry and the underlying context. However, as the design progressed, new questions arose, and respective research needs emerged. Our team sought answers to aspects related to worker clothing, crane mechanics, language, dialogs, etc. We realized that we needed to be in contact with experts, gather related resources and perform trials even in later stages. Furthermore, given that the historical and cultural content was spread in various aspects of the application, such as the media, the stories, the dialogues, the appearance, the movements, etc., we often needed to present our assumptions to experts and get their opinion to ensure we are following the right path.

Balance between accuracy and simplicity. Interactive museum installations essentially serve two roles. On one hand, they are part of the exhibition and as such they need to provide educational content that is accurate and relevant to the museum’s central theme. On the other hand, they must motivate and engage the user in playful activities. Playfulness should be the vehicle to increase visitor curiosity and awareness for the museums’ contents. In the design of such systems, one should be careful to maintain a good balance between these two roles. The application should have valid content but not be too realistic to make actions unnecessarily complicated or even dull. In our case, we had to simplify the operation and workings of the crane to make it easier for visitors to use it instantly and intuitively. Respectively, the worker cooperation, their movements, and the tying/untying of marbles are significantly faster compared to reality, to make the experience shorter and more exciting.

7. Conclusions

In this paper, we presented an interactive installation for the Museum of Marble Crafts in Tinos, Greece and the collaborative design and development process that we followed for its creation. The installation adopts a mixed reality approach combining a tangible interface with a large-screen 3D environment, and its goal is to demonstrate the operation of a large mechanical crane in the old quarries of Tinos. The crane is exhibited in the museum, but visitors don’t get the chance to see it in action, let alone to operate it themselves. The aim of our installation is to immerse visitors in an old quarry, let them adopt the role of the crane operator, and complete a series of challenges in a playful manner. For the development of the project we followed an iterative participatory design approach that included parallel activities of research, prototyping and co-design. Designers, developers, engineers, curators and cultural heritage experts were involved in the development team, we produced a series of prototypes that combined physical and digital content, and we evaluated our design with users and experts both in the laboratory and on site. The evaluation results were generally positive, indicating that the system under development is considered easy to use and playful by prospective users and appropriate for the museum by the experts.

The usage and preliminary evaluation of the system revealed some considerations regarding the design of mixed reality installations. It has been recognized by users and experts that the operation of the tangible controller for interacting with the digital world was an engaging experience, and initially their focus was mostly centered at the physical interface rather than the challenges presented in the environment. This confirms previous findings that tangible interfaces encourage initial visitor interactions in museums [18]. However, after the first surprise and curiosity, users shifted their attention to the 3D content and were actively trying to achieve their goals, without even looking at the controller. There were two aspects that critically affected the experience from then on. The first was their understanding of the controller operation; some users had misconceptions about the moving parts and their intended use in the environment and they had to spend time to tune their physical actions with the actions of the digital workers. The second was the response and feedback from the environment; it is evident in the series of evaluations that the mean user ratings improved when we enhanced and adjusted the feedback (in the form of sound and visuals) in the digital interface. Even more interesting was the fact that the improvement was greater in the ratings related to the educational content. The aforementioned observations lead to the conclusion that designers of hybrid systems should place more emphasis on designing the form and function of tangible interfaces in a way that their intended use is instantly communicated, and at the same time provide a natural, intuitive mapping of the physical interactions to the digital actions.

The collaborative design and development process that we adopted was decided based on the needs and complexity of the system under design, and it has produced favorable results so far. It combined open and prototype-led co-design, taking advantage from both approaches. In the initial, open co-design phase, the team studied the museum collection, its visitor profiles and the underlying cultural and historical context, and designed appropriate concepts without technological restrictions. When the main concept was decided, the prototype-led phase helped curators and cultural heritage experts to engage in the design and participate from the early stages sharing their ideas and expertise. The process has been organized in parallel sub-groups working on research, design and technology issues, and their collaboration has been supported by series of organized workshops. This breakdown of activities helped the team manage the complexity of the project, construct evolutionary prototypes that have been positively evaluated by users and experts, and uncover critical design aspects from the early stages.

It seems that mixed reality is a promising medium for orchestrating cultural experiences that combine tangible elements with intangible heritage. In the case of our installation, the user is inspecting, operating and getting a first grip on the mechanics of the crane, and she is also immersed in a working environment of the past, learning about the culture and customs of the workers, and getting valuable hints on the organization of the mining business of the old times. She is adopting a role in the first person, getting to know the hard-working environment and the risks of marble extraction. However, the design and evaluation of mixed reality environments for digital culture is a complicated process and being a relatively new field, there is a notable lack of related guidelines and methodologies. Further research on collaborative design methods and tools for this area is needed to produce best practices and paradigms and inform designers of future systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.V., V.N., P.C. and P.K.; methodology, S.V. and V.N.; system development, S.V., L.F., M.S.; writing—review and editing, V.N., S.V., M.S., P.C. and P.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research has been co-financed by the European Union and Greek national funds through the Operational Program Competitiveness, Entrepreneurship and Innovation, under the call RESEARCH—CREATE—INNOVATE (project code: T1EDK-15171).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Questionnaire Used in the User Evaluations

5-point Likert scale: 1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree

Appendix A.2. Design Elements

Appendix A.2.1. Controller

- It was simple to understand how to interact with the controller.

- The interaction with the crank for raising and lowering the boom was understandable.

- The interaction with the crank for changing the gear pair was understandable

- The interaction with the rope for the overall rotation of the crane was understandable.

- It was easy to use the crank to raise and lower the boom.

- It was easy to use the crank to change the gear pair.

- The ropes were easy to use.

Appendix A.2.2. Physical-Digital Mapping

- 8.

- It was easy to associate parts of the digital crane to respective parts of the physical controller

- 9.

- The digital workers were responding to my actions as expected

- 10.

- The orientation of the controller with respect to the screen was convenient.

- 11.

- My perspective of the scene helped me to understand the actions that took place.

Appendix A.2.3. Digital Workers

- 12.

- The digital workers helped me understand how the crane was operated

Appendix A.2.4. Challenges

- 13.

- The duration of the challenge did not tire me.

- 14.

- The challenge posed by the application was easy.

Appendix A.3. Application

Appendix A.3.1. Easy to Use

- 15.

- The overall interaction was easy to understand.

Appendix A.3.2. Pleasant

- 16.

- The duration of the interaction as a whole did not tire me.

- 17.

- The overall interaction was pleasant.

Appendix A.3.3. Fun

- 18.

- The overall interaction was fun.

Appendix A.3.4. Educational

- 19.

- The overall interaction was educational.

Appendix A.3.5. Appropriate Guidance

- 20.

- The information provided on the screen helped me understand the handling.

Appendix A.4. Educational Content

Appendix A.4.1. Crane Mechanism

- 21.

- I understood the basic functions of the crane

- 22.

- I understood the importance of the crane for marble transportation.

Appendix A.4.2. Crane Operation in Quarry

- 23.

- I understood how the crane supported the mining process in the quarry

- 24.

- I understood the places where the crane was installed in the quarry

Appendix A.4.3. Worker Roles

- 25.

- I understood the individual roles of the people who contributed to the operation of the crane.

- 26.

- I understood the sequence of actions and coordination between the workers needed to carry out the transportation of a volume of marble.

Appendix B

Appendix B.1. Questionnaire Used in the Expert Evaluation

5-point Likert scale: 1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree

Appendix B.2. Interaction Style Adequacy

- It was simple to figure out how to interact with the application via the controller.

- It was engaging to interact with the application via the controller.

- It was simple to understand the three basic functions of the controller, and how they were reflected in the digital environment (screen): boom raising and lowering, rope raising and lowering, shifting gears from the central shaft.

- The three basic functions of the controller were a convenient means of interaction in relation to the corresponding functions of the crane in the application.

Appendix B.3. Integration Area

- 5.

- The basic idea of the application is related to the space in which the application is exposed.

- 6.

- The designated location of the installation is near the exhibits of the museum with relevant content (e.g., crane, “Karageorgis company at Vathi”, wagon, quarries, quarry tools, etc.).

- 7.

- The other exhibits in the surrounding area are not distracting user interaction with the installation (e.g., sounds, ambient music, videos, etc.).

- 8.

- The installation complements the other exhibits of the space in which it is exhibited.

Appendix B.4. Visibility

- 9.

- The interactive installation in its designated location is easily visible inside the museum.

- 10.

- The interactive installation in its designated location is part of the main route of a visit to the museum.

- 11.

- The interactive installation has enough information for visitors to recognize what its key components (controller, monitor or screen) do.

- 12.

- The interactive installation has elements in its appearance that encourage visitors to use it (controller, buttons, screen, graphics).

Appendix B.5. Feedback

- 13.

- The interface of the interactive installation provides visitors with useful information, recognizable, and understandable (intelligible graphics, instructions, sound, lighting, instant feedback on control actions, etc.).

- 14.

- The interactive installation informs visitors about events, results, and system status changes (e.g., from the rotation of the biga to the download of the needle), as well as the remaining interaction time.

- 15.

- The flow of interaction in the application is understandable (e.g., instructions, system status changes, the success of individual challenges).

Appendix B.6. Structure and Aesthetics

- 16.

- The elements that constitute the interactive installation, are organized and arranged to reflect a familiar aesthetic with that of the museum.

- 17.

- The layout, the format, the visual correlations, and the distinction of the elements of the content of the application are similar to the content of the museum and the content of the relevant exhibition.

- 18.

- Elements such as the font type, the colors used, the type of virtual characters and the virtual environment, have quality and consistency in relation to the exhibition space of the museum.

- 19.

- Elements such as the control, the control in relation to the content on the screen, and the position of the user in relation to the associated collection/exhibition, promote the identification of identical objects that exist in other areas of the museum.

Appendix B.7. Learning

- 20.

- The interactive installation gives the visitor the feeling of a “free choice” so that she begins to interact with the application.

- 21.

- The installation challenges the visitor to search for new knowledge (cognitive challenge) so that she can learn new things in an informal educational environment.

- 22.

- The installation provokes the critical thinking and questioning of the visitor in relation to events and ideas of the time that are presented.

- 23.

- The installation provides the visitor with multiple perspectives that will allow her to come to her own conclusions and draw her own meanings.

Appendix B.8. Entertainment

- 24.

- The interactive installation allows the visitor to see new and interesting things in a relaxing and aesthetically pleasing environment.

- 25.

- The interactive installation creates opportunities for participatory experience (friends and family participate when using the application).

- 26.

- The interactive installation provides the opportunity for other “observers-visitors” to observe or even participate in what happens during a visitor’s interaction with the application.

- 27.

- A visitor couple/group/family can enjoy a social experience through interaction with the interactive installation.

- 28.

- The installation creates spaces for dialogue or even allows the emergence of other forms of social interaction, cooperation, or exchange, such as rewarding or cheering, observing and giving instructions, discussing the content displayed or the results, etc.

- 29.

- The interactive installation can accommodate up to four (4) guests.

References

- Ciolfi, L.; Bannon, L.J. Designing hybrid places: Merging interaction design, ubiquitous technologies and geographies of the museum space. CoDesign 2007, 3, 159–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nofal, E.; Reffat, M.; Vande Moere, A. Phygital heritage: An approach for heritage communication. In Proceedings of the Immersive Learning Research Network Conference, Coimbra, Portugal, 26–29 June 2017; Verlag der Technischen Universität Graz: Graz, Austria, 2017; pp. 220–229. [Google Scholar]

- Bannon, L.; Benford, S.; Bowers, J.; Heath, C. Hybrid design creates innovative museum experiences. Commun. ACM 2005, 48, 62–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anagnostakis, G.; Antoniou, M.; Kardamitsi, E.; Sachinidis, T.; Koutsabasis, P.; Stavrakis, M.; Vosinakis, S.; Zissis, D. Accessible Museum Collections for the Visually Impaired: Combining Tactile Exploration, Audio Descriptions and Mobile Gestures. In Proceedings of the Workshop on Mobile Cultural Heritage, Mobile HCI 2016 (18th International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction with Mobile Devices and Services), Florence, Italy, 5–9 September 2016; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Georgiadi, N.; Kokkoli-Papadopoulou, E.; Kordatos, G.; Partheniadis, K.; Sparakis, M.; Koutsabasis, P.; Vosinakis, S.; Zissis, D.; Stavrakis, M. A Pervasive Role-Playing Game for Introducing Elementary School Students to Archaeology. In Proceedings of the Workshop on Mobile Cultural Heritage, Mobile HCI 2016 (18th International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction with Mobile Devices and Services), Florence, Italy, 5–9 September 2016; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Koutsabasis, P.; Vosinakis, S. Kinesthetic interactions in museums: Conveying cultural heritage by making use of ancient tools and (re-) constructing artworks. Virtual Real. 2018, 22, 103–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galdieri, R.; Carrozzino, M. Natural interaction in virtual reality for cultural heritage. In Proceedings of the International Conference on VR Technologies in Cultural Heritage, Brasov, Romania, 29–30 May 2018; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 122–131. [Google Scholar]

- Fischnaller, F.; Guidazzoli, A.; Imboden, S.; De Luca, D.; Liguori, M.C.; Russo, A.; Cosentino, R.; De Lucia, M.A. Sarcophagus of the Spouses installation intersection across archaeology, 3D video mapping, holographic techniques combined with immersive narrative environments and scenography. In Proceedings of the 2015 Digital Heritage, Granada, Spain, 28 September–2 October 2015; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2015; Volume 1, pp. 365–368. [Google Scholar]

- Dimitropoulos, A.; Dimitropoulos, K.; Kyriakou, A.; Malevitis, M.; Syrris, S.; Vaka, S.; Koutsabasis, P.; Vosinakis, S.; Stavrakis, M. The loom: Interactive weaving through a tangible installation with digital feedback. In Digital Cultural Heritage; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 199–210. [Google Scholar]

- Pietroni, E. Experience Design, Virtual Reality and Media Hybridization for the Digital Communication Inside Museums. Appl. Syst. Innov. 2019, 2, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornecker, E.; Ciolfi, L. Human-Computer Interactions in Museums. In Synthesis Lectures on Human-Centered Informatics; Morgan & Claypool Publishers: San Rafael, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ishii, H.; Ullmer, B. Tangible bits: Towards seamless interfaces between people, bits and atoms. In Proceedings of the ACM SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Atlanta, GA, USA, 22–27 March 1997; pp. 234–241. [Google Scholar]

- Hornecker, E.; Buur, J. Getting a grip on tangible interaction: A framework on physical space and social interaction. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Montréal, QC, Canada, 22–27 April 2006; pp. 437–446. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, J.H.; Harley, D.; Kwan, J.; McBride, M.; Mazalek, A. Sensing History: Contextualizing Artifacts with Sensory Interactions and Narrative Design. In Proceedings of the Conference on Designing Interactive Systems, Brisbane, Australia, 4–8 June 2016; pp. 1294–1302. [Google Scholar]

- Price, S.; Sakr, M.; Jewitt, C. Exploring whole-body interaction and design for museums. Interact. Comput. 2016, 28, 569–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrelli, D.; Ciolfi, L.; Van Dijk, D.; Hornecker, E.; Not, E.; Schmidt, A. Integrating material and digital: A new way for cultural heritage. Interactions 2013, 20, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornecker, E.; Stifter, M. Learning from interactive museum installations about interaction design for public settings. In Proceedings of the 18th Australia Conference on Computer-Human Interaction: Design: Activities, Artefacts and Environments, Sydney, Australia, 20–24 November 2006; pp. 135–142. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, J.; Sindorf, L.; Liao, I.; Frazier, J. Using a tangible versus a multi-touch graphical user interface to support data exploration at a museum exhibit. In Proceedings of the Ninth International Conference on Tangible, Embedded, and Embodied Interaction, Stanford, CA, USA, 15–19 January 2015; pp. 33–40. [Google Scholar]