Abstract

In the wake of the trade in ancient materials, several ethical and political issues arise that merit concern: the decimation of the cultural heritage of war-torn countries, proliferation of corruption, ideological connotations of orientalism, financial support of terrorism, and participation in networks involved in money laundering, weapon sales, human trafficking and drugs. Moreover, trafficking and trading also have a harmful effect on the fabric of academia itself. This study uses open sources to track the history of the private Schøyen Collection, and the researchers and public institutions that have worked with and supported the collector. Focussing on the public debates that evolved around the Buddhist manuscripts and other looted or illicitly obtained material from Afghanistan, Pakistan and Iraq, this article unravels strategies to whitewash Schøyen’s and his research groups’ activities. Numerous elements are familiar from the field of antiquities trafficking research and as such adds to the growing body of knowledge about illicit trade and collecting. A noteworthy element in the Schøyen case is Martin Schøyen and his partners’ appeal to digital dissemination to divorce collections from their problematic provenance and history and thus circumvent contemporary ethical standards. Like paper publications, digital presentations contribute to the marketing and price formation of illicit objects. The Norwegian state’s potential purchase of the entire Schøyen collection was promoted with the aid of digital dissemination of the collection hosted by public institutions. In the wake of the Schøyen case, it is evident that in spite of formal regulations to thwart antiquities trafficking, the continuation of the trade rests on the attitudes and practice of scholars and institutions.

1. Introduction

The continuing destruction of cultural heritage and archaeological sources through looting, trafficking, trading and collecting of ancient objects is widely condemned. The chain of procurement from looters to collectors has received increasing attention in the wake of contemporary conflicts. Researchers and academic institutions are important links in this chain, because they play a role in facilitating the trade in antiquities or can be key to impeding it. It is therefore relevant to explore their practical role and ethical responsibilities. However, due to the illicit nature of the trade and the dubious role of experts, insights are fragmented and disjointed.

This study focuses on the Norwegian Schøyen collection of antiquities and manuscripts, the actions of its collector Martin Schøyen, and his collaboration with scholars and academic institutions. The Schøyen case represents “demanding research… related to the fact that the main person does not collaborate. …[and problems] getting through the closed networks of collectors, smugglers and dealers” [1] (p. 1). Still, parts of the case are well documented [1,2,3,4,5] and give comprehensive insights into the modus operandi of collectors and researchers at the receiving end of unprovenanced [6] objects and manuscripts. This article follows the case’s history, before focusing specifically on the actions and role of researchers and academic institutions, and the implications that engagement with illicit trade and collecting have for the academic communities. Starting with material acquired by Schøyen in Afghanistan and Pakistan from the mid-1990s, this article outlines the impact of a significant collector and trader. Spanning thirty years, the Schøyen case follows the overall market and trade development from traditional auctions and face-to-face deals, to online trades and commissions. The collector’s extensive, but opaque collaboration with experts, politicians and public servants is an important perquisite for his collecting, his attempts at publicly legitimizing his actions and to sell the collection. After piecing together what is publicly accessible, this article examines some of the political and ethical issues that arise from the collaboration that experts, public servants and institutions have had with Schøyen. The case is a comprehensive example of what Manhattan Assistant District Attorney Matthew Bogdanos in 2005 famously characterized as the cozy cabal of academics, dealers and collectors [7]. Illicit trade promotes fakes and forgeries of objects and ownership history, entailing that the foundation for disciplines that use source materials without provenance information is tenuous. Researchers and institutions involved with illicit objects are readily confronted with a requisite for duplicity to mask the recent biography of objects that they study to retain access to the material. Perhaps starting as an omission of facts perceived as innocuous, academic involvement with this trade undermines researcher independence. This can corrupt the fundamental ethos of science: transparency, critical study and an ideal of truth. These issues arise in conjunction with the Schøyen case.

Research continuously demonstrates connections between collecting, trafficking, looting and the role of experts in enabling the antiquities trade [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21]. Scholars and academic institutions inadvertently or actively play pivotal roles in the trade of objects [10]. They authenticate, date and determine origin, study content, publish and exhibit objects, and counsel collectors [22,23]. These contributions are crucial to the working of the market, especially for endeavours to move objects from a criminal sector to an open market, as well for creating monetary appreciation on investments [9] (p. 44).

The Schøyen case also represents a history of successes. Journalists and academics have painstakingly created an extensive knowledge base; public attention has increased; and looting, trade, appropriation of public funds and public disinformation have, to a degree, been obstructed. In Norway, the Schøyen case probably contributed to catalyse legislation through the country’s ratification of the 1970 convention [24], and increased vigilance from authorities following its implementation. As looting is ultimately market-driven, a strategy to inhibit looting and trade is to deter the market in prosperous countries. To this end, the Schøyen case indicates that public involvement and knowledge of “what, how, who and why” in the trafficking and collecting business is key.

2. Background

Martin Schøyen started collecting books in the 1950s, and since then he has acquired cultural objects and manuscripts, sometimes in competition with museums [25]. Many of these objects have subsequently been studied and published by scholars and sold on for large sums. A recent example is sale 18152 at Christie’s on 10 July 2019. The scholarly interpretation and historical value ascribed to the pieces figure prominently in the auction catalogue. For example, lot 402 (An Old Babylonian Cuneiform Clay Tablet of the Ur-Isin King List) is listed with a bibliography of five scholarly publications from Schøyen collection researchers. The sale was titled The History of Western Script: Important Antiquities and Manuscripts from the Schøyen Collection. Occasionally, Schøyen’s sales are also promoted in Norwegian media [26].

The case of the Schøyen collection has unfolded since the 1990s. In addition to the scholars involved in publishing it, especially Schøyen’s previous head-of-research Jens Braarvig [27], the collection’s most visible Norwegian supporters and partners have been the National Library of Norway and its former director (1994–2002), Bendik Rugaas. Now retired, Rugaas was a senior Labour politician, cabinet member (1996–1997), vice director of the Norwegian National UNESCO Committee (1992–1996), director of Norway’s Culture Council, European Council general director, and embassy councillor in Washington (2004–2006). Moreover, numerous individuals and institutions have been involved in acquisitions, research, facilitation, management and public promotion of Schøyen’s collection.

To date, the involved parties have not provided comprehensive or consistent accounts of their activities. This has resulted in a twenty-year cat-and-mouse game of deflections, public misinformation, and circumvention, countered by investigative journalism and research. Discrepancies in various participants’ assertions and publications were important indications of undisclosed issues. Suspicions that there were significant issues concerning Schøyen and his collaborators were fueled by persistent questions by concerned academics [8,9,28,29,30], research by investigative journalists [31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40], leaks from Schøyen’s supplier Bruce Ferrini to art trader and police informant Michel van Rijn [1], claims made by governments (Afghanistan, Pakistan, Egypt and Iraq), and a University College London (UCL) investigation in Britain [41] - initially withheld from the public, but published through WikiLeaks [17]. To keep track of the flow of material at the time, Atle Omland managed (until 2005) a web-based bibliography of documents [42]. An indispensable source to the Schøyen case is the two-part documentary Skriftsamleren (The manuscript collector) by the Norwegian broadcaster Norsk rikskringkasting (NRK) [43]. Further information became public through documents submitted by Schøyen’s attorneys [44,45] and NRK [1,3] to the Norwegian Press Complaints Board (Pressens faglige utvalg) in conjunction with their handling of Schøyen’s complaints [4]. Ironically, the combination of Schøyen’s erratic attempts at deflecting criticism along with his lawyers attempts to argue technical details and threats of lawsuits [36] has corroborated Schøyen’s involvement with illicit trade, lack of transparency and inconsistency.

Critics of Schøyen and his partners were initially mildly questioning [28,46] but with the unfolding of stories, events and the conduct of those involved, an appreciation of the seriousness of the events evolved [2,9,29,30,47,48]. The body of data coming out of the Schøyen controversy is enormous and often confusing, and we suspect that significant parts of Schøyen’s transactions and networks remain obscure. The publicly accessible information, however, supports a uniquely informative account.

3. A Market Facilitated and Countered by Scholars

3.1. Text Studies and the Publication of Unprovenanced Material

Many archaeologists and heritage researchers recognise that illicit trade destroys historical resources, and many have been outspoken in their criticism. Researchers in fields such as ancient manuscript studies, however, can have attitudes that are more ambiguous, as their concern is primarily what can be read in a text and what authentic meaning can be proposed [49,50] (p. 186). Though it is sometimes acknowledged that studying texts with a dubious ownership history can be ethically and scientifically challenging [51,52,53,54], there has traditionally been limited substantial recognition of the problems in research traditions studying ancient text. For example, in 2006, a group of scholars issued a statement through the Biblical Archaeology Society protesting measures to stop the publishing of unprovenanced material. Researchers involved in a wide range of material in the Schøyen collection (Jens Braarvig, Jöran Friberg, Andrew George and Shaul Shaked) were among the signees advocating the right and duty of academics to research and publish material that surfaces through the antiquities market. The statement and its list of signees have since been removed from the BAS webpage, but is still available in web archives [55]. Given the money involved, counterfeits and fakes predictably plague ancient text research [56,57,58], undermining the foundation for reliable research. An example is the exposure of widespread forgery in recently surfaced Dead Sea scrolls [23,59,60,61,62].

Numerous publishers and professional institutions have established rules and guidelines, ostensibly to avoid becoming accessories to the trade in cultural objects (e.g. International Council of Museums (ICOM) Code of Ethics for Museums, European Association of Archaeologists (EAA) Code of conduct, American Schools of Oriental Research (ASOR) Policy on Professional Conduct, American Antiquity), and to discourage specialists from assisting traders. In-house publishing is a strategy that circumvents requirements of transparency and proactive provision of information about provenance. A notable feature in the Schøyen Collection series is that many of the Schøyen volumes are published by Hermes Academic Publishing. Hermes is owned by Amund Bjorsnes, the private Norwegian Institute of Philology (PHI, with Bjorsnes listed as head-of-department), and Schøyen series editor Braarvig (who is listed as director at PHI and Hermes, previously affiliated with the University of Oslo, now with The Norwegian School of Theology, Religion and Society [MF]) [63]. The Hermes webpage provides no information about publishing procedures, no ethics standards and no review policy. Unfortunately, there are also well-established and prestigious academic publishers that publish objects with dubious provenance. Publisher Brill was recently criticised in an open letter [64] composed by Roberta Mazza and signed by a number of ancient manuscript specialists. They addressed the exposure of forgeries among published manuscript fragments in the Publications of the Museum of the Bible. Brill had failed to address issues of the objects’ provenance and acquisition history, and Chief Publishing Officer at Brill Jasmine Lange responded by referring to the use of peer review and editorial boards, actions in good faith and the contentious nature of provenance issues. She invited discussion of “additional policies related to provenance and associated topics that promote integrity and strengthen the interests of the academic community”. The response seems opaque, and Brill’s actual position remained unclear. The original statement penned by Mazza is representative of an evolving trend in parts of the academic community: a concern about provenance among researchers involved in the study of ancient manuscripts. This trend appears to be fuelled by the exposure of forgeries in their datasets [65,66].

3.2. Schøyen and the “Dead Sea Scrolls of Buddhism”: Going Public

In 1994, an unknown number of objects from Schøyen’s collection were exhibited in Oslo in connection with the annual Conference of European National Librarians. The conference was hosted by the newly appointed Director of the National Library Bendik Rugaas. No records or catalogues seem to exist, but the exhibition appears as a reference in the Schøyen collection database [67] and in promotion of auction sales [68]. In October 2000, the Norwegian National Library announced that it stored cuneiform tablets for Schøyen and that it would host an online database of Schøyen’s collections of ancient manuscripts. It organised an event to mark the inauguration of the database [69]. In this flurry of public announcements, Schøyen also hinted that he might sell the collection. According to Rugaas, the National Library was a potential buyer, and he urged the Norwegian government to purchase the collection and permanently exhibit it. According to Schøyen and Rugaas the aim was to “put Norway on the global map, culturally speaking” [70].

On the same occasion, Schøyen announced that he had dedicated resources to saving 1400-year-old Buddhist manuscripts from destruction at the hands of the Taliban. In the interview with the newspaper, Aftenposten Schøyen explained his altruistic and dramatic rescue operation:

After the Buddhas of Bamiyan were destroyed in March 2001, an embellished version of this story was circulated. In a radio interview that same year, Schøyen now referred not only to the manuscripts as Buddhist, but also to the refugees as Buddhists fleeing religiously motivated persecution:The Norwegian collector contributed so the unique and previously unknown Buddhist texts were, in a dramatic fashion, transported out of Afghanistan on the backs of donkeys through passes at an altitude of 5000 meters through Hindukush. “The manuscripts date from second to 7th century and contain the oldest of the most important texts in Mahayana Buddhism, the sutras, Buddha’s sermons. Refugees sought safety in a cave and found manuscripts in the ground under the cave floor. A few fragments came to London, where I was offered to buy them. The rest were in Afghanistan, where Taliban forces wanted to destroy everything associated with previous religions. A majority of the manuscripts are therefore in fragments while others are intact books.Schøyen organised a rescue operation to get the manuscripts. “No lives were lost, but I had to pay a premium price”.[70]

When the stories were retold in other media [72], the altruistic nature of Schøyen using his fortune to save humankind’s cultural heritage was further expanded by referring to a fight against poverty and for human rights through the Schøyen Human Rights Foundation. The foundation is purportedly to profit from Schøyen’s sale of antiquities, though exactly what will go to the fund was and is obscure. Beyond declarations like “The Schøyen Human Rights Foundation to give emergency aid and fight poverty in emerging nations, and to promote Freedom of Speech and Human Rights worldwide” [25], it is vague what the fund actually intends to do. It has minor assets (NOK 6.3 mill in 2017) and has not been active beyond “running expenses”, conceivably including minor support for activities in Norway [73].Buddhists fleeing the regime had sought shelter in the caves and they saw fragments of birch bark and palm leaves, and they understood that they were Buddhist texts. They then sent out a cry for help: Can anyone help us save these from destruction? The regime had then blown up a Buddha statue, and a book under Buddha’s hand was blown into thousands of pieces, I have all these pieces and they are restored. I looked upon this as a rescue expedition to save part of the world’s cultural heritage that otherwise would have been destroyed.[71]

Schøyen later maintained that he “declines all offers for everything illicitly excavated, and stays far away from illicit export” [74] (p. 29). Still, he continued to avoid the issue of how materials in his collection were transported from Afghanistan to Pakistan to London and Norway [74], but explained that researchers counselled him throughout the process. The project Buddhist Manuscripts in the Schøyen Collection (BMSC) was established in 1997. It was among others facilitated by Braarvig, Jens-Uwe Hartmann, Kazunobu Matsuda, Lore Sander, and later Paul Harrison [75]. Before joining the research group, Lore Sander appears to have worked for the dealer Sam Fogg in preparing the initial 108 manuscript fragments in London for auction [51,76,77] (pp. 89–90) [78] (p. 161). Arguably, Sander’s and other scholars’ involvement was essential for creating marketable objects, as Fogg had little ownership information, and was not sure of the potential context [43].

Schøyen’s story about a cave in Bamiyan has some analogies to an account published by Sylvain Lévi in 1932 [79,80], and scholars involved in the BMSC project have recently been accused of both plagiarizing and circumventing references to Lévi’s text [80] (pp. 77–81). Elements in Lévi’s 1932 story of how fragments were found resemble Schøyen’s account of the fragments he purchased. It is conceivable that the researchers familiar with Lévi supplied Schøyen with a skeleton for the media story, updated with references to contemporary events.

In retrospect, the timing for circulating and embellishing the story does not seem to be a coincidence in terms of a public opinion strategy. After the Taliban blew up the Buddhas of Bamiyan in March 2001, they became the target of a worldwide outcry of condemnation, and with the 2001 attack on the World Trade Centre September, Islamic groups were the epitome of Barbary [81]. By conflating a story of thwarting the Taliban with his collecting practices, Schøyen harvested praise for having rescued invaluable cultural property. In one interview, Schøyen compared his collection—and by extension himself—with Norwegian icons like Ibsen, Vigeland and Nansen [71].

3.3. The Academic Part of the Cozy Kabal

In explaining “why Schøyen had the manuscripts transferred to Norway”, he held that Braarvig, “one of the world’s most prominent scholars in his field of research” was based at the University of Oslo (UiO) [72]. Braarvig started assisting Schøyen in 1996 and appeared as Schøyen’s de facto spokesperson by 2000 and until lawyers took over around 2005. Braarvig euphemistically explained that Schøyen’s material “f[ell] down in the countryside of Norway” [82], for example in cigar boxes that turned up at irregular intervals (every one to three months) in London from Pakistan [1], to later inexplicably turn up at the UiO. In the Schøyen publications the manuscripts are said to “appear”, after “[l]ocal people trying to save the manuscripts from the Taliban were chased by them when carrying the manuscripts through passes in the Hindukush to the north of the Khyber Pass. Further damage was incurred in this period, but the rescue operation was for the most part a success” [83] (p. xiii). Braarvig continues to invoke the story as late as 2010 [75] (p. xviii).

In 2001, Braarvig received a grant from the Norwegian National Academy of Science for Schøyen’s group to research the collections at the Centre for Advanced Study in Oslo. In October 2001, the centre’s newsletter published two articles in which both Schøyen and Braarvig were interviewed [84]. Here, Braarvig celebrated the value of Schøyen’s collection and condemned the acts of the Taliban in Bamiyan, thus conflating the appearance of the manuscripts with the recent Islamist atrocities, and bolstering Schøyen’s altruistic image. Braarvig then puts forward an argument that also Schøyen would continuously appeal to: “[a]t the risk of not being absolutely politically correct, I dare to assert that in our day and age it is the European intellectual tradition that is most concerned about safeguarding ancient cultural treasures.” [84] (p. 4). In his next publication, Braarvig continues in a similar vein: “In an age where conflict and terror loom dangerously large and so much is needlessly lost, it is a source of considerable reassurance that these literary remains of a religion devoted to peace are preserved by the efforts of people from different nations and cultures working together for a common goal.” [53] (p. xiv). Beyond the euphemisms and omissions, Braarvig’s rhetorical project to defend his and Schøyen’s practices appeals to specific ideas and claims:

- Schøyen’s collecting as a rescue operation

- Altruism in Schøyen providing researcher access to the material

- The unique value of “Buddhism’s Dead Sea Scrolls”

- Taliban as an expression of Muslim barbarism

- Buddhist victimisation

- European exceptionalism

These claims and the orientalist tropes at their core, all support the idea of Schøyen as a legitimate holder of the manuscripts [85]. The Newsletter article went on to reiterate an earlier statement [86] that though Schøyen did not currently plan to sell his collection, this could happen in the future [84]. A few months after the newsletter was published, Schøyen announced that he intended to sell the collection, and the media campaign launched a few months earlier was intensified. In an interview with the Newspaper Dagens Næringsliv [87], Schøyen proposed that the Norwegian government buy the collection so that the proceeds could be channelled into “an eternal fund for humanitarian rights, freedom of speech and aid” and that the collection could thus be kept as a unit in Norway. In the same article, the conservative Minister of Fisheries Svein Ludvigsen supported Schøyen’s proposal. Ludvigsen’s personal links to Schøyen became apparent in a stunt to promote a government acquisition, when Schøyen organised a press event at his home. On this occasion, Schøyen lets Ludvigsen wear a ring purportedly belonging to Tut-Ankh-amon and flip through the pages of the Magna Carta [87]. Ironically, the ring was not Tut-Ank-Amon’s, but apparently came from the grave of a member of his court. In mid-2003, Egyptian authorities demanded Schøyen return 17 illicitly acquired objects, including the ring [88].

Braarvig and history Professor Francis Sejersted supported a Norwegian government purchase, while media Professor Hans Fredrik Dahl glorified Schøyen [89,90]. The National Library director Rugaas not only supported the proposal [91], he “demanded” that it be purchased [92]. Schøyen’s own value appraisal in November 2000 was 600 mill. NOK, but by March 2002 the asking price had risen to 850 mill NoK (100 mill. USD). Reservations were voiced about a potential misguided use of public funds [93].

3.4. Tangled Webs

Though Schøyen asserted that there were other bids and potential buyers for his collection, details beyond vague allusions to “an Islamic state” (which he said he had no intention of selling to) never materialised [34]. There seems to be little validation for the asking price, but Schøyen and his allies seemed confident that they could pressure their only known potential customer, the Norwegian government, into making an offer. It seems that the seller’s network of public servants and politicians was represented on all sides of the table.

On Norwegian radio late 2001, Schøyen maintained “[t]he National Library should buy it [the collection] and keep it …and get a proper building to house it. 1000 sq. m. have been set aside in the National Library” [94]. Apart from demonstrating that talk of a “Schøyen wing” at the National Library had come far, this illustrates a central element in the Schøyen affair. Public “whitewashing” of Schøyen and his collection was based on personal ties in networks extending through government administration, politics and academia. The supporters in favour of government acquisition of the collection seemed utterly unconcerned about Schøyen’s apparent lack of proof of legitimate title or ownership. The interweaving of interests between Schøyen, public institutions and researchers took on a quasi-institutional guise in 2002 when Schøyen collaborated with Braarvig and Christoph Harbsmeier (UiO and the Centre for Advanced Study) and started the private Norwegian Institute of Palaeography and Historical Philology [95], later renamed Norwegian Philological Institute (PHI). PHI is listed as a foundation with Braarvig as head-of-the-board and director and Amund Bjorsnes as head-of-department [96]. As of 2018, PHI is also affiliated with the Norwegian School of Theology, Religion and Society (MF) [97]. As noted, PHI owns slightly less than a third of Schøyen publisher Hermes. Other owners are Braarvig and Bjorsnes. The interworking between the different partners in these organisations is not transparent. It is also unclear if or how much money Schøyen or the Schøyen Humanitarian Fund has channelled into Hermes or PHI.

3.5. Critical Questions and Rising Demands for Restitution

Late 2001, cautious reservations concerning Norwegian appropriation of cultural objects from Afghanistan were voiced by National Archivist John Herstad [98]. Responses to this, and questions about title of ownership and provenance raised by Omland and Prescott [28] were not provided in writing, though comments were made in interviews and at an open meeting at the University of Oslo in March 2002 [99]. The event was organised by Professor Dahl who had previously stated his sympathy for Schøyen and Braarvig [89]. Braarvig and Schøyen implicitly and explicitly upheld stories about the material in Norway resulting from a rescue operation and stood by the legitimacy of Schøyen’s ownership.

Similarly, the suggestion by UNESCO Director Ingeborg Breines in Islamabad, that objects should be returned to their rightful owners [100] was summarily rejected. Omland and Prescott (2002a, b) and others also contended that the UNESCO approved facility Afghan Museum in Exile in Switzerland would be an appropriate place to deposit the materials provisionally. In an unpublished part of an NRK-interview with Braarvig from 2004, he reads a letter provided by Schøyen, who maintains that the option had been considered “a couple of years ago”, but not found safe. Braarvig held that the objects were better kept in Norway than Switzerland, because rumours said that material previously deposited at the museum had disappeared to resurface in the market [101]. When asked for examples or documentation in support of these serious allegations both Schøyen and Braarvig were unable to provide any [43,101,102]. UNESCO’s Breines contacted the museum, which reaffirmed that artefacts were stored in a safe [103].

Inquiries and claims from other governments arose in the wake of the debate on whether the Norwegian government could afford to or should buy the collection. On 2 March 2002, Egypt’s ambassador to Norway called on the Norwegian Ministry of Culture (MoC) to ask how Schøyen came by the Egyptian objects, and asked for assistance from the authorities in dealing with Schøyen [104,105]. However, the Norwegian authorities declined to assist [106]. They were publicly criticised by the Egyptians in August 2003 for twisting and turning to avoid responsibility [107]. In September 2003, Afghanistan’s Minister for Culture, Sayyed Raheen, sent a letter to the Norwegian Minister of Culture, Christian Democrat Valgerd S. Haugland. He appealed for assistance in the return of the Schøyen objects taken illegally from Afghanistan [35,108]. The letter generated new rounds of public debate about Schøyen and Norway’s practices.

The MoC had an ambivalent position when responding to the suggestion that the MoC should coordinate a public purchase of Schøyen’s collection [109]. While declining to purchase the collection for financial reasons [93], the MoC’s response to calls for inquiries and restitution claims from foreign states was across the board negative. In its answers, the MoC pointed out that Afghanistan was not signatory to the UNIDROIT Convention on Stolen or Illegally Exported Cultural Objects and neither Norway nor Afghanistan had ratified the 1970 UNESCO Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property. The Ministry concluded in November 2003 that Norway did not have the legal instruments to interfere with the collection [110]. Without conducting substantive inquiries, they effectively acknowledged Schøyen as the rightful owner.

The 1958 Code for Protection of Antiquities in Afghanistan (part I) defines all articles of historical value that predate 1748 as national antiquities, and under the protection of the State. Part VII pertaining to Export of Antiquities (clause 59) states that it is prohibited to export antique articles out of Afghanistan without the written permission of the Directorate General of Museums and Preservation of Antiquities. In light of Afghanistan’s legislation, it is puzzling that the MoC did not commit to serious diplomatic consultations to explore options. Legal, ethical and diplomatic concerns were to become part of the MoC’s attitude towards the Schøyen collection later, but such perspectives seem to be absent before 2004. The magazine for Norwegian Museums, Museumsnytt, pointed out the lack of sensitivity in the MoC’s refusal to seriously consider Afghanistan’s claim: “Norway is currently participating in warfare in Afghanistan. Can the Norwegian government accept that Afghan cultural treasures removed from the country in wartime and currently held in Norway, are traded on the international market?” [31].

Schøyen categorically snubbed the Afghanis, sticking by his story of a rescue operation, retorting in Dagens Næringsliv: “Of course they had to have a go at it, but this changes nothing. The manuscripts hardly have any ties to Afghanistan, apart from the fact that they were found there. Most of them were written on palm leafs in India -and as everyone knows there are no palms in Afghanistan. Furthermore, there was no Afghanistan when they were written. The country has also changed religion from Buddhism to Islam. Buddhism is not very relevant there anymore. … there is no formal foundation for the demand in reference to the UNESCO convention, as Norway was not a member when the manuscripts were rescued out of Afghanistan” [35] (p. 46).

Schøyen’s overbearing, legalistic dismissal of Afghanistan’s claim may be seen as indicative of a stereotypically colonialist attitude to cultural property. As noted above, Braarvig had previously expressed similar views, and he continued to defend Schøyen as the rightful owner [27,53]. Rugaas had previously responded to claims of restitution by confusing superficially related issues: “If one follows this logic one has to immediately start emptying The British Museum, Louvre and all other significant museums and libraries in the world. They are filled with manuscripts that clearly do not originate in the countries where they now are to be found.” [91].

By the autumn of 2003, there was an increasing appreciation for the fact that Schøyen had acquired his manuscripts from London-based dealers such as Sam Fogg [76]. The credibility of Schøyen and Braarvig’s Afghanistan stories publicly eroded. The institutions that had previously been positive to an acquisition were now distancing themselves from Schøyen. Despite the apparent inconsistencies and gaps in Schøyen’s (and his researchers’) narratives, none of the involved offered a candid acquisition history. Questions also surfaced concerning acquisition of objects from Iraq after August 1990 and a possible breach of UN Security Council sanctions. Schøyen now answered vaguely that he could not rule out illegalities [111]. Increasingly, Schøyen’s image changed from national hero to dishonest collector.

4. The Next Turn: The Manuscript Collector

4.1. Journalistic Inquiry

The exposure of the antiquities trade has often been furthered through journalistic inquiry [112,113,114,115,116,117]. The case of Schøyen’s collecting and acquisition practices attained further depth and scope in September 2004 when the Norwegian Broadcaster NRK aired the two-part documentary Skriftsamleren [43]. The recordings and the ensuing legal correspondence documented the contradictory narratives produced by Schøyen and Braarvig during the documentary’s extended time of production. Though originally sympathetic to Schøyen and Braarvig, the discrepancies in Schøyen and Braarvig’s stories raised the journalists’ suspicions [38]. Dedicating substantial resources to investigative journalism, the documentary follows the story from collector via enabling academics, smugglers and dealers to looters.

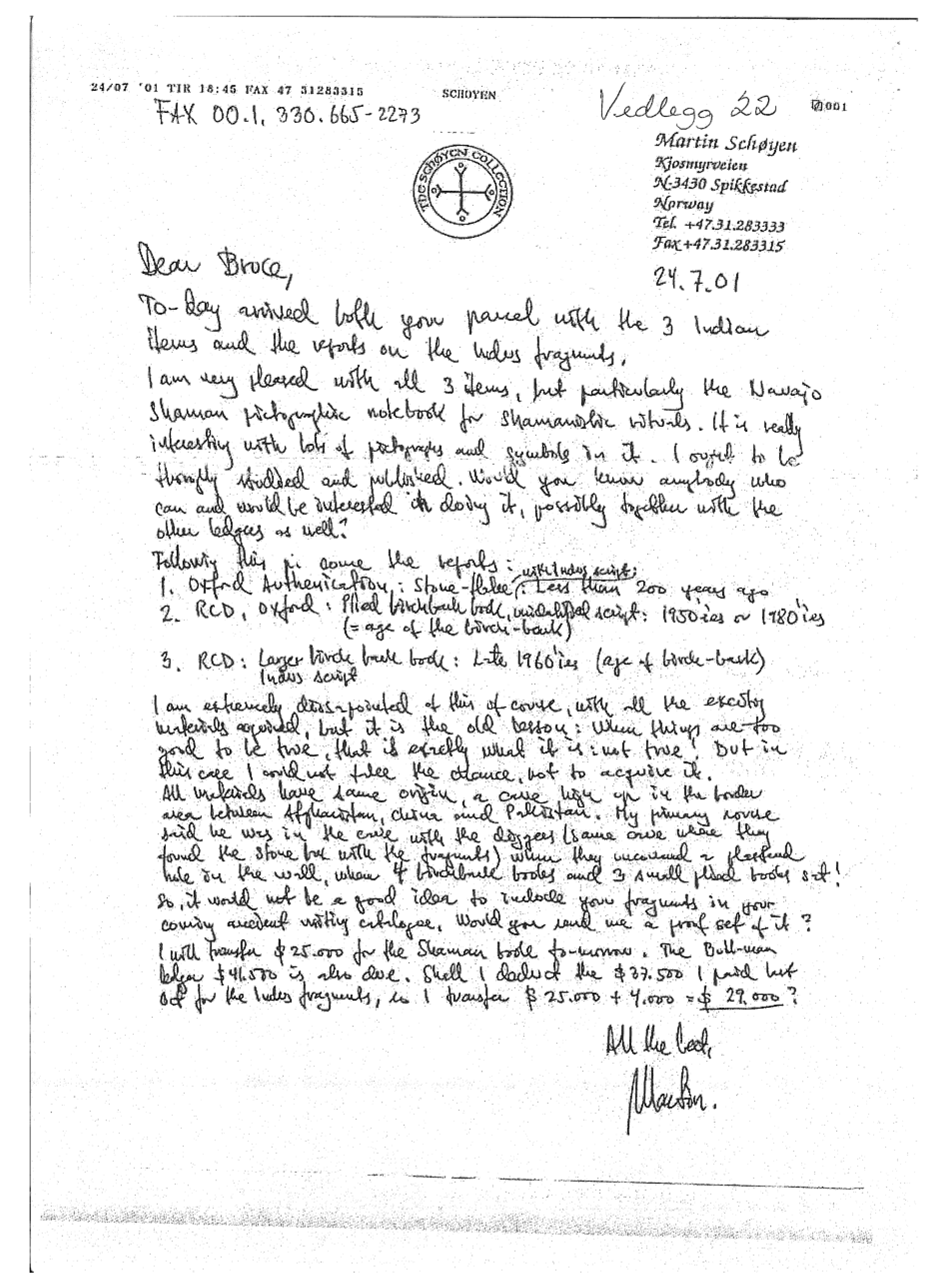

The documentary confirmed that the manuscripts Schøyen claimed to have rescued from the Taliban were purchased over a period of more than six years, starting 1995–1996. The collection was shown to contain six previously published manuscript fragments [79] looted from the National Museum in Kabul. According to the documentary, the Afghani fragments had been illegally taken from Afghanistan via Pakistan to Europe. A significant group of the fragments were looted in Pakistan. Moreover, the documentary suggested that Schøyen initially traded with dealers in London, but went over to dealing directly with smugglers, offering a fixed price for fragments. Schøyen admitted that he knew of three smugglers who brought objects to London, and had statements provided by them, but both he and Braarvig refused to supply their names [4]. NRK found and interviewed one of the smugglers who confirmed the smugglers’ routes, and that in addition to antiquities, they were involved in drugs and arms trade. NRK alleged that one smuggler was Zahid Perez Butt [1,38] (Schøyen refused to answer questions concerning Butt, so it is unclear if he is one of the aforementioned three smugglers), and they also contended he was suspected of selling weapons to the Taliban. In the 2019 Felony Arrest warrant issued by the criminal court of New York for i.a. dealer Subhash Kapoor, one of the partners is named: the “The Butt Network”. It is said “to supply the international art market with stolen antiquities from countries including, but not limited to, Afghanistan, Pakistan and India.” [118] (p. 24). A fax (Figure 1) referred to in the Skriftsamleren documentary and ensuing documentation indicates that Schøyen communicated with agents who dealt directly with looters in Pakistan [1,3,38,119,120]. According to NRK, this is but one of several faxes that demonstrate that Schøyen had a “main source” for manuscripts in Northern Pakistan [3] (p. 11). Schøyen’s lawyers tried to use wording in the fax, ambiguities concerning the position of the cave that was looted and claims that the fax was stolen to undermine the relevance of the fax [45]. These arguments seem irrelevant and inaccurate, and met with little success [1,4] (pp. 10–15, [3]). The fax demonstrates that Schøyen had few reservations about procuring material at the source end. The fax and the fragments from Pakistan (see below), demonstrate that he actively acquired materials from Pakistan.

Figure 1.

“My primary source said he was in the cave with the diggers…”. Copy of fax communication between Schøyen and dealer Bruce Ferrini. Source: NRK [1,3,120].

It seems that the American dealer and Schøyen supplier Bruce Ferrini reacted to Schøyen’s direct engagement with apparent traffickers by leaking incriminating faxes to the former dealer Michel van Rijn [3] (pp. 13–14) [38] (p. 16). Van Rijn published some of them on his website and gave journalists access to others.

Looting and illicit trade in cultural property is a well-known issue in the border areas of Afghanistan and Pakistan [121,122]. Counter to Schøyen’s story of his rescue mission and concern about avoiding illicit materials, the NRK-investigations provided robust evidence that Schøyen’s and the British Library’s market involvement led to a wave of looting. They concluded that “[t]he increased demand for such manuscripts—something that was first affected by the acquisition by the British Library and thereafter by Schøyen’s fixed-price offer—encouraged smugglers to travel from Peshawar and Swat up to the Gilgit-area searching for similar manuscripts. The same happened in Afghanistan” [1] (pp. 10–11). The documentary’s footage from the ruins of a Buddhist Stupa looted in response to commercial demand shows smashed ceramic depositories, carelessly dug looting pits and manuscript fragments fluttering away in the wind. It would seem that acquisitions and ensuing market demand sustained by Schøyen and his research team ignited significant destruction.

Aftenposten asked Schøyen why he had claimed to have rescued the objects from the Taliban when this was not the case. Schøyen admitted: “I have never been to Afghanistan or Pakistan for that matter. My rescue mission was that I made it known in London that I would pay a fixed price per square inch for Buddhist manuscripts. This is how the manuscripts were collected” [123]. In light of the information concerning Schøyen’s close engagement with the trade networks, it seems that even this answer is only a partial truth. Instead of actually giving an explanation in the interview, Schøyen retorted, “this make me sound like a crook”.

In response to articles pointing to the fraudulent “rescue mission” in Afghanistan and his alleged collaboration with organised crime, Schøyen claimed he was misrepresented by the documentary, and now communicated through lawyers [44]. They stated on his behalf “that the manuscripts that are found in the Schøyen collection as far as he can ascertain are not acquired in an illegal manner.” [124]. Despite the circumstantial and cryptic formulation, in hindsight it seems that even here Schøyen’s account is not the full truth. In the letter from the lawyers, they maintained the monetary value of the collection had suffered and NRK was therefore threatened with a lawsuit [125]. A complaint was filed by Schøyen’s lawyers [44,45] with the Press Complaints Board, but failed [4]. The complaint case brought forth valuable written documentation, and Schøyen’s lawyers inadvertently verified the basis for—and added detail to—previous critical accounts. The British Library, another major collector, did not confirm or refute their role as buyers of manuscripts smuggled from Afghanistan. This was presumably because, as suggested by Neil Brodie [8] (pp. 48–49, [9]), the Library lacked sufficient documentation of the manuscripts in their possession—a serious issue for a public museum.

Recognising that manuscripts acquired by Schøyen were looted and smuggled before the Taliban government came into power, was an important step in picking apart the hoaxes he and his partners perpetrated. However, it seems that Schøyen was still buying long after the Taliban came to power, perhaps until 2004. Though Taliban groups are probably directly involved in the trade in antiquities, the bulk of the looting, smuggling to Pakistan and other facets of the trade in Afghanistan and Pakistan are run by a variety of criminal networks aimed at profit. They smuggle weapons, drugs, art and a host of other items, trading i.a. with the Taliban, providing insurgents with necessary hardware. The Taliban generates revenue by taxing the trade or extorting protection fees [126,127] (p. 37, [128]). Schøyen’s rescue story was crucial to his attempt at creating a sellable narrative in Norway, but also to his efforts at disassociating his activities from the dubious networks of which the evidence indicates, he was on the receiving end. However, it is unlikely that Schøyen was an exception from the general pattern. Indeed, punctuating his rescue story, uncovering some smuggler and looting networks, and the admittance by Schøyen and Braarvig of purchases in London indicate that he is part of a recognisable pattern of illicit trade. Instead of outwitting the Taliban and saving heritage, it is reasonable to ask to what extent Schøyen has funded looting and destruction, and how close he was with networks that supplied the Taliban [38] (p. 15). By extension, the public institutions that have assisted Schøyen, e.g., the National Library, UiO, MF, and the National Gallery, seem to have been negligently part of the same chains.

4.2. Something Rotten in Academic Norway

In one interview, Braarvig euphemistically described his surprise “that such a thing could fall down in the countryside of Norway, but of course this gave an extra incentive for me to take responsibility for it.” [43]. Despite their apparent attempts at feigning ignorance, the NRK documentary as well as the Schøyen collection researchers’ own publications demonstrate that they were aware of the inconsistencies in this story [78] (p. 174). The programme demonstrated that some of the involved academics knew about the fragments stolen from Kabul Museum and the material from Pakistan. A passage in Skriftsamleren I shows scenes when Braarvig is confronted with what journalists have discovered about Kabul Museum:

- (Braarvig:)

- “The fragment in question from Kabul Museum, we have known about since 98, I think we found out. Since then we have kept it in our own hands”.

- (Journalist:)

- “Why did you decide to keep it for yourself?”

- (Braarvig:)

- “Well, this we have considered as the best, in fact”.

Later, when confronted with the fact that Schøyen had acquired material from Pakistan, Braarvig uncomfortably confesses:

- (Braarvig:)

- “Well, there are a few leaves which has [sic] crept into the collection”.

- (Journalist:)

- “What will happen with the Pakistani material”?

- (Braarvig:)

- “Well, there has been no discussion of that, but it may be an issue, of course” [129].

Schøyen would later admit that Braarvig’s “few leaves” that had “crept into the collection” were “maybe 200–300 from Gilgit” [130]. He defused the relevance of the alleged involvement with Pakistani looters and smugglers by maintaining, through his lawyer, that “he has never paid much for fragments from the Gilgit-region” [45]. Now, Pakistani authorities were aware of the looted and smuggled materials from Pakistan, and directed requests to Schøyen and Norwegian authorities [131]. The latter (through Christian Democrat Deputy Minister Yngve Slettholm) once again held they could do nothing, maintaining that the “manuscripts are and will remain Schøyen’s property” [132], strangely asserting, “if they are illegally acquired, it is the owners who must consider returning them” [133]. A few months later Schøyen apparently felt pressured to acquiescent to returning the Gilgit fragments to Pakistan [134], and did so in 2005 [135].

During the production and in the aftermath of the NRK documentary, Afghanistan reasserted claims for the objects to be returned [108]. In Skriftsamleren I, Braarvig was asked about restitution (probably before he knew that journalists were aware of material looted from Kabul Museum and Pakistan), and responds: “Today, at least, they could hardly take care of it. And of course, send it back, what does it mean? After all it is owned by Mr. Schøyen. He bought it as … well so if the Norwegian state wants to buy the whole collection, they might act with it as they like, of course” [43]. About the same time, Braarvig suggested that “the Norwegian State should buy the collection and use it for a cultural dialogue with Afghanistan, to build up institutions in Afghanistan … .” [27]. The suggestion is odd given that Braarvig knew that the collection contained material looted from Pakistan as well as stolen fragments from Kabul, and that it all had been smuggled into Europe. He probably understood that a government purchase could solve his issues with Schøyen, but also that it was legally and ethically untenable: a purchase would have been political and financial government support for illicit trade, organised crime and terrorism. Considering the questions concerning Braarvig’s involvement with dubious trade and collecting, his suggestions come across as stabs at defusing criticism and salvaging a sale for Schøyen.

Later in the NRK-programme, after the connection to looting of Kabul Museum was revealed, Braarvig claimed he now had a letter from Schøyen to the Museum dated 7 July 2004, and he appears to read it in an extra recording. In the letter, Schøyen allegedly states that the now “two fragments should be kept together. We would be pleased to donate this fragment to your museum. We look forward to advice about when and how to proceed.” When asked for a copy, Braarvig refuses: “Well, this is a handwritten letter from Martin Schøyen himself, and I think it is not eager [sic] to give out this handwriting unnecessarily.” [43] The letter is claimed to have been sent with certified post from a gas station outside Oslo. As documentation, Schøyen later offered a handwritten “receipt” written on a blank piece of paper with a stamp from the station. Neither UNESCO, Afghanistan’s authorities nor anyone else saw the letter [43].

Schøyen did not act immediately on the offer to return fragments, and later, in 2005, the Schøyen Collection’s webpage held “that Afghanistan probably is not the right and safe place for these MSS in the future, …consideration and clarification about a possible future return … is an ongoing process.” [2] (pp. 239–240). Based on NRK’s documents, it seems that Schøyen researcher Matsuda now advised Schøyen. The archives in Kabul were destroyed, and documentation was not readily accessible. Matsuda, in conflict with his own email to the documentary makers a month before, and with what Schøyen, Braarvig, Brekke and Kværne and others outside the Schøyen group at different times said they had known for years, back-pedalled on the fact that the material came from the collection in Kabul Museum [1]. In an email to Flyum August 2004 (with cc to Braarvig), Matsuda states that he now recommended Schøyen to not return fragments [3]. Schøyen’s change of heart may reflect that Matsuda led him to think he could get away with keeping the fragments. In 2007, however, Schøyen conceded to returning stolen fragments. In a 2014 publication, Braarvig states that Schøyen returned “a representative selection of the manuscript materials to Kabul Museum” [51] (p. 163). On the Schøyen webpage [136], the number stolen from Kabul Museum are now admitted to be seven, but the site says a further 43 or 44 will be returned. Euphemistically called a “gift” and “goodwill gesture”, the number coincides with the original 50 fragments in the Kabul Museum collection. Schøyen and his researchers were always vague about the number of fragments from Kabul Museum. Originally, Braarvig admitted to one fragment, the retracted 2004 offer was two, the current Schøyen collection webpage (apparently not recently updated) mentions 50–51 to be returned by end of 2007 [136], while on March 8, 2008 Afghanistan’s foreign ministry states: “Mr Martin Schøyen, the owner of this collection, gifted seven fragments in October 2007 and 58 manuscripts on 5 February 2008 to National Museum through the Afghanistan Embassy to Norway and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Mr Schoyen had bought the manuscripts through smugglers and exhibited them at the Schoyen Collection … .” [121] (p. 147), i.e. 65 fragments. This might indicate that the theft from Kabul was significantly more extensive than previously acknowledged [85] and that Schøyen continued to resist returning looted material into 2008.

Braarvig’s student Torkel Brekke and colleague Per Kværne confirmed in a newspaper article that the group knew about the stolen manuscripts as of 1998 [137]. They feebly maintained that the stolen fragments were kept separately. They claimed that there had been no attempt to keep the stolen fragments secret, but do not explain their silence during the 2001-06 debates, or why information was not published. They addressed none of the questions raised in public, the years of denial of ownership issues, and refusals to acknowledge claims for restitution or deposition in a neutral safe house. Like Braarvig [51], they simply claimed that what had come forth was untrue and supplied testimonies by offended non-Norwegian members of the Schøyen group.

5. A Pattern of Illicit Trade and Denials?

5.1. Another Case: The Post-2002 “Dead Sea Scrolls”

It later turned out that the collection of Buddhist manuscripts contained forgeries, and these were detected with the assistance of another public institution, Norway’s National Gallery [138] (p. 45). Furthermore, in the early 2000s, Schøyen was among the chief buyers of a new wave of Dead Sea Scrolls-like fragments [23]. Schøyen proudly took credit for creating the market [23,139]. Later, around 2006-07 it seems that Schøyen remained relatively passive as buyer. Given his tarnished public reputation, he might have chosen to keep a low profile. However, Schøyen could have been strapped for cash after the bus company Concordia (in which he had a 47% stake) went bankrupt, and he sustained substantial losses [140]. From 2009, American evangelical institutions and individuals were the main targets for acquisition of Dead Sea Scrolls and virtually any “biblical” artefacts [117]. It later turned out that many of the so-called post-2002 Dead Sea Scrolls fragments were probably forgeries [59,60]. Arguably, Schøyen and other evangelicals who bought unprovenanced fragments and manuscripts again generated the incentives for forgers and potential looting. Collectors like Schøyen stimulate the industry of fakes, and it is therefore not surprising that forgeries turn up in collections of unprovenanced material.

5.2. Another Case: Iraq and Incantation Bowls and Other Materials

As mentioned above, questions arose in 2002 concerning cylinder seals and cuneiform tablets from Iraq in the Schøyen collection. The second part of the 2004 NRK documentary, Skriftsamleren II, indicated that a large body of bowls with Aramaic incantations in Schøyen’s collection had been illegally removed from Iraq [38,43]. They appeared to have been looted on the ground, exported in breach of the UN-embargo and supplied with forged certificates of previous ownership. Shaul Shaked who had signed the BAS-petition advocating the right to publish material unprovenanced from the antiquities market, also studied the bowls [55]. The bowls had been deposited at UCL for study [141]. At first, UCL leadership denied the veracity of UCL’s involvement, but it would later be demonstrated that the materials were stored and handled at UCL without the leadership’s knowledge. The situation led to public involvement and the UCL appointed a high-profile investigation team that included Colin Renfrew [142]. The committee recommended that the report be made public, but on concluding the report, it was suppressed. Wikileaks later secured a copy from the Parliament Archives and published it [41]. The report found that the documentation is confused but concluded “on the balance of probabilities” that the bowls had been illegally removed from Iraq [41] (p. 2). At this time, Schøyen instigated legal action against UCL, leading to an agreement that probably included the suppression of the report [143] (pp. 46–47). Interestingly, the shared statement supplied by UCL and the Schøyen Collection make no substantive references to realities or documents in the case [144], but instead misrepresented the UCL report’s conclusions [145]. In an out-of-court settlement, UCL returned the bowls to Schøyen, and paid an undisclosed compensation, probably to avoid a process that would be time and money consuming. Colin Renfrew criticised UCL’s actions in no uncertain terms: “It is shameful that a university should set up an independent inquiry and then connive with the collector whose antiquities are under scrutiny to suppress the report through the vehicle of an out-of-court settlement” [146].

There is no room here to delve further into the intricacies of Schøyen and his researchers’ dealings with the Iraq material. The case of the incantation bowls is covered at some length by other researchers [9,17,147,148]. However, further questions have recently been raised concerning these materials [118,149] and objects allegedly looted from the National Museum in Baghdad, exhibited in honour of the 25th anniversary of Thor Heyerdahl’s Tigris expedition at the Kon-Tiki Museum in Oslo in 2003. Iraq’s ambassador to Norway has made repeated inquiries in Norway concerning Schøyen’s Iraqi objects, and recently made a formal request to the Norwegian Ministry of Culture for the assistance in the return of more than 700 objects [141].

Schøyen’s trade in dubious material from Iraq further demonstrates how academics and institutions with the goal of gaining access to materials enable the business in antiquities. Universities cave into legal threats, while authorities do not prioritize investigating and prosecuting cases like this. Finally, the material from Iraq, like that from Afghanistan, was a central part of the Norwegian National Library’s affiliation with Schøyen.

5.3. Digitization as a Strategy: The National Library’s Collaboration with Schøyen

As noted above, the National Library in Norway had been involved with Schøyen long before the official announcement of collaboration in October 2000, and he had a strong backer in the Library’s director Bendik Rugaas. The collaboration between Schøyen and the Library included storage and the running of a website dedicated to Schøyen’s collection. It would seem that the resources for managing the site were drawn from the Library itself. Critical questions were raised in 2002, and at this point a section director at the Library, Sissel Nilsen (Rugaas was on leave) advised against the government buying the Schøyen Collection [89]. She stated that the Library was no longer interested in a purchase and had reservations about the use of library resources on the collection [31].

Though no longer housing or officially pushing to acquire Schøyen’s collection after the airing of the Skriftsamleren documentary, the Library continued to host Schøyen’s website [32]. Critics maintained that the site legitimatized Schøyen’s practices, and helped to whitewash and commercially promoted the collection [150]. Furthermore, the Library was criticised for not taking its duty to exert editorial control seriously, and did not ascertain that the published material was not acquired through or associated with illegal or unethical activities.

Rugaas’ successor, Vigdis M. Skarstein held a series of board positions in Norwegian public cultural institutions, i.a a member in the UNESCO national committee that Rugaas chaired. She initially ignored the criticisms; however, the pressure from the museum sector, academics and the media did not subside, but rather increased in the wake of the NRK documentary. Later, vocal objections to the partnership with the Schøyen Collection escalated when it became known that potentially incriminating provenance information in the databases had been removed, that the Library still did not exercise editorial control, and had not required documentation of ownership history or legal acquisition [151]. In 2004, Skarstein maintained that Schøyen had assured the Library that there were no ethical or legal issues, and that the Library had checked [152]. In the face of mounting criticism, she long held that the Library was dealing with digital representations, and that they were simply making content available to the public [153]. She claimed that this now made the case unproblematic.

To support her position, in 2005 the Library enjoined a professor in digital copyright, Skarstein’s predecessor as head of the Norwegian Council of Culture, Jon Bing to review the Library’s practices. Bing echoed the statements by Braarvig and Schøyen concerning the disjuncture between Afghanistan’s present population and past groups, and concluded that the Library’s practices were not in breach of copyright law [154]. Bing’s response generally came across as irrelevant to the ethical and political issues. The exercise, however, comes across as an unfortunate attempt to side-track from the issues. Under continued public pressure, in 2006 the National Library conceded to request provenance and acquisition evidence from Schøyen [155]. He allegedly submitted it on October 29, 2006. In 2007, Schøyen withdrew from further collaboration with the Library, apparently because he could or would not provide a degree of transparency the Library now required [156]. Skarstein did not explain why investigations the Library said they had undertaken in 2004 were now found to be faulty.

A full account of the National Library’s and its leaders’ dealings with Schøyen has yet to be made available. The case of the Norwegian National Library and Schøyen is a further example of Schøyen’s strategy of drawing bureaucrats and politicians into collaborative networks, and their appropriation of public resources for the promotion of the collection. It is also an example of how closed networks and unprofessional “partnerships” between private wealth and public sector can be misguided. However, it is primarily an example of how a public institution—and its directors—completely ignored ethics and public concerns about improper acquisitions, assisted a private collector, deflected criticism, but in the end was forced to change its policy.

6. Business as Usual?

Legal Efforts

Norway ratified the 1970 UNESCO convention in 2007. In order to prevent countries from serving as transits for illegally traded objects, the 1970 Convention requests States to prevent the export of illegally imported cultural property. In accordance with the Norwegian Cultural Heritage Act, designated public institutions have a delegated mandate and authority to handle export permits for cultural objects. Pursuant to the Regulations on the import and export of cultural objects section 6d, the National Library is the decision-making authority for cases involving printed texts and manuscripts. Thus, they are also responsible for issuing export permits for ancient manuscripts. This is no small matter, as decisions have ramifications beyond the export permit itself. When the Library issues an export permit, it effectively provides the exporter with a document indicating legal title to the object. In principle, future transfer of objects will be supported by the Library’s export certificate.

The National Library was deeply involved with and facilitated the Schøyen collection until 2007, and only withdrew their support under public pressure. Given the National Library’s close ties with Schøyen, its lapse in competence and a potential conflict-of-interest, one would expect meticulous handling of license applications. Decisions to issue export licenses are available through the government’s online service for public records, eInnsyn [157]. As far as we have been able to ascertain, all Schøyen’s post-2007 applications for export permits have been approved by the National Library, most recently an application dated 14 October 2019, granted 16 October 2019. An application dated 30 April 2018 is for four items to be sold through Bloomsbury Auctions, London. Among the four is one object described as:

The application’s handwritten assessment of the provenance is brief:“MS187, Exodus, papyrus manuscript, 4th c. 2ff. 26x32 cm, under glass”.

The manuscript in question is also found in the Schøyen Collection’s online database, but with a slightly different description [158]:“Francois Antonovich, Paris, 1988, ex Antonovich coll. ca. 1955–1988.”

The provenance information here is also at odds with the application: “1. François Antonovich, Paris (1981–1988); 2. Bruce Ferrini, Akron, Ohio.”“MS in Greek on papyrus, Egypt, mid 4th c., 5 ff., 26 × 16 cm, originally 28 × 16 cm, single column, (22 × 12 cm), 32 lines in an expert Greek uncial.”

There are several things to take note of here. First, the export application’s phrase “ex Antonovich coll. ca. 1955–1988” is ambiguous. It seems to imply that the leaves were in the Antonovich collection since 1955, but this is unlikely (see below). Second, it is puzzling that Bruce Ferrini is not mentioned in the provenance description for MS 187 in the export application. It is well known that Schøyen bought his part of the Codex from Ferrini, an antiquities dealer with a dubious reputation [159] (p. 4). Nicknamed “Scissorhands” by fellow dealer Michel van Rijn, Ferrini was renowned for partitioning manuscripts to create more, individually priced pieces of merchandise [160]. Third, the codex of which MS 187 seems to have been a part appears to have been transferred from Egypt in the late 1970s or early 1980s [161,162], which implies that as a cultural object it was illegally taken out of Egypt [163]. Furthermore, comparing the little information in the application with that in the catalogue, the discrepancy between what appears to be 5 folios (“5 ff.”) described in the web page catalogue and the 2 folios (“2ff.”) described in the application appears odd. The measurements given in the export application suggest that bifolia (pairs of conjoint leaves) are in view, while the measurements given in the catalogue refer to single folia or leaves. So, the application is for export of four leaves (that is, two bifolia), but according to the catalogue, Schøyen owned five leaves of this codex. This is confirmed in the published edition of the codex [164,165]. It could be a mistake in the handwritten application. Or perhaps Schøyen indeed sought to sell off only parts of his manuscript? If so, it appears to be a continuation of Ferrini’s destructive practice of separating leaves from the same manuscript for commercial reasons. In any case, it seems that any of the factors laid out above should, together or by themselves, have indicated that the export application warranted more in-depth scrutiny. There are no details in the export permit, it simply says, “granted”. The application is dated 30 April, received 4 May and approved 7 May 2018. The National Library appears not to have conducted an inquiry concerning the application’s discrepancies and the manuscript’s history. Thus, by signing the permit the National Library appears to be negligent and may in effect have contributed to laundering an object. Ironically, the implementation of the UNESCO 1970 convention in Norway may potentially have the opposite effect of that intended by policymakers. Instead of preventing the illicit transfer of ownership of cultural property, through lax procedures it could be providing another route for whitewashing dubious materials.

7. The National Committee on Ethics in the Humanities and Social Sciences

A Curious Ethics Review

As part of UiO employees’ involvement with Schøyen, it appears that the University Library stored material for the Schøyen collection. This became an embarrassment for the university after the NRK documentary, and Schøyen was asked to remove the collection from UiO within six months [166] and research on the Schøyen collection was halted [167]. The University asked The National Committee for Research Ethics in the Social Sciences and the Humanities (NESH) to evaluate the issues of principle involved. NESH was not charged with exploring the Schøyen-Braarvig cases, nor did it have any particular a priori competence or expertise in the field among its members or as a committee.

In preparation for its report, NESH organised a seminar March 2005 with the title: How to conduct research on material with unknown provenance? The stated background for the seminar was “the noise that has been in the media and academic circles after the Schøyen case” [168], and the seminar came across as primarily concerned with the interests of researchers: how to continue previous practices: tackle obstacles of dubious provenance, but avoid challenges concerning ethics. Braarvig was invited as an expert on sensitive materials. The Swedish heritage researcher Staffan Lundén spoke at the event, but none of the Norwegian archaeologists who had been engaged in the issue were invited to contribute—or even informed about the seminar until immediately before the event.

Given the above premises and the committee’s somewhat obscure mandate and composition it is not surprising that the ensuing report [169] lacked a coherent analysis, and did not address fundamental issues confronting disciplines that continue to engage looted, smuggled, and unprovenanced materials. Vague recommendations reflecting a hesitancy to express any decisive position were expressed in the reports eight bullet points:

- “Research on material with an insecure or unknown provenance should be judged on balance between freedom of research, preservation, new knowledge, dissemination and restitution.

- Researchers and institution should show necessary care. This means an obligation to make inquiries and consult other experts in the field.

- A minimum requirement is that institutions and researchers require that the owner of collections permit research on ownership history.

- Researchers’ duty to inform entails informing the research institution in case of suspicions that the material is stolen or acquired in an unethical fashion, or there are insecurities in regard to provenance or ownership history.

- An initiative to create a national instance responsible for following up researcher and institution’s obligations to inform and alert.

- Institutions generate routines for reporting that permit monitoring material with insecure or unknown origins.

- Expert assistance, like identification, classification and storage should take place in complete candour. In case of suspicions that the material is stolen or acquired in an ethically dubious fashion, or there are insecurities associated with the provenance or ownership history, there is an information requirement.

- Guidelines in the relevant research fields should be expanded to cover material with unknown or insecure provenance.” [169]

The report contradicts itself on the Schøyen-Braarvig matter. It first establishes and then reiterates that “NESH has, …, neither the possibility nor mandate to conduct an examination to ascertain origin history or ownership history, or to provide a detailed description or evaluation of events and management at UiO. The committee has limited its statement to answering the questions of principle that the rector has raised.” Though not approaching the case’s substance and ignoring the long history of public debate, “NESH still questions whether it was correct to stop the research on the Schøyen collection. The committee acknowledges that there was a need for a pause to reflect to determine how the institution was to handle this and similar cases. Still, it appears to be interference in the freedom of research that a research project is interrupted shortly after a debate in the media. … suitable reaction would have been … the establishment of an internal forum where the relevant researchers could have openly discussed with each other, and warned central authorities in case of uncertainties concerning ownership and provenance ” [169].

As a study in ethics or as a guideline, the NESH document is mainly curious. It has, however, been used to argue that Braarvig was acquitted of any transgressions [170], and NESH has not attempted to correct or address the misrepresentations of the report. Interestingly, in the 2002 volume of Buddhist Manuscripts in the Schøyen Collection (before the NRK documentary and NESH report) provenance is not addressed beyond admitting, “that the exact find-spots of these items are unknown and that proper excavations have not been carried out is deplorable, since the artifacts are shorn of context” [53] (p. xiii). In a later volume, the introductory chapter briefly addresses criticism and the Skriftsamleren documentary and presents various justifications for the publication of the objects in the Schøyen collection [170] (p. xiii). It refers to the conclusion by NESH that formed the base for the University of Oslo’s reasons given for continued research and publication of Schøyen’s material [171]. The story about a rescue from Taliban is absent in this volume, but provenance issues also remain unaddressed. In ensuing volumes, these issues are touched upon in passing, with statements appealing to the right and duty of scholars to identify, describe and edit unprovenanced material [51,172]. Beyond such justifications, publishing generally follows the patterns established in 2002 and earlier volumes. Indeed, in the 2010 and 2014 volumes the old narrative about the Taliban rescue operation is partially resurrected and used to defend the Schøyen group’s activities [86] (p. xviii). It seems that even the mild NESH recommendations have been ignored by the editors and the contributing scholars. Arguably, the NESH report has mainly served to assert, erroneously, that the activities of Braarvig and his team have been reviewed and been “acquitted”. Braarvig’s introduction to the 2006 volume in the Schøyen series [170] quotes UiO rector Arild Underdal’s letter that refers to NESH permitting the resumption of Schøyen research.

The NESH document seems to represent first and foremost the interests of colleagues and institutions, which arguably undermines the legitimacy of academic autonomy. The reluctance to limit researchers’ access to research material is also reflected in NESH’s present, guidelines pertaining to objects with dubious or disputed provenance (revised 2016) [173]: “An absolute prohibition of research on objects with a dubious provenance may constitute a threat to the duty of the researcher to acquire and preserve cultural remains in order to analyse them and convey the results to the general public and future generations. In some cases, one might ask whether objects are really taken care of where they are, and whether it is possible to carry out important research there. This is especially true if the material originates from war zones or from societies characterised by corruption.” Interestingly, involved institutions also seem to ignore any responsibility, whether in reference to general academic standards, NESH’s water-downed guidelines or international professional standards. MF’s involvement with PHI is case in point. When UiO “restarts” Schøyen research, there is no indication of a review or audit of the Schøyen-Braarvig group’s activities. This shows that UiO was unprepared for dealing with ethical issues when real interests and conflicts were at stake, and it would seem that UiO caved into pressure from Schøyen and other individuals and groups with an interest in maintaining status quo.

8. Infringements on Autonomous Research

Mehreen Sheikh [80] has reviewed the publications by Braarvig and other scholars involved with the “Buddhist Dead Sea Scrolls” as research practice. She contends that Schøyen collection researchers, driven by self-promotion, have rushed their publications to such an extent that the scientific and ethical quality of the research results suffers [80] (p. 68). Sheik argues that a lack of proper referencing, misleading citations, misrepresentation and exclusion of work done by others blemishes the publications. In part, Sheikh builds her case on other reviews conducted by Daniel Boucher [174] and Seyfort Ruegg [175], but she also presents her own analysis of research ethics and academic culture.

Here, the review by Daniel Boucher is interesting for further reasons. He is critical of the scientific quality of the 2002 volume edited by Braarvig, e.g. pointing out inconsistent translation and poorly argued identifications between the contributions in the volume, but is mostly unconcerned about the authenticity, legality and provenance of the manuscripts. Boucher has a casual reference to a lack of contextual information about the manuscripts, largely paraphrasing Braarvig’s introduction to the volume [170] “[a]lthough the in situ context of the manuscripts’ discovery is largely lost, the scanty details provided by local dealers suggest that they were found relatively recently in the Bamiyan Valley by locals taking refuge from advancing Taliban forces.” [174] (p. 245). Like the scholars involved with Schøyen, Boucher praises Schøyen for making the material accessible for researchers: “This new collection of manuscripts has been brought to light in large part through the kind offices of Martin Schøyen, an antiquities collector who recognized the tremendous value of these documents and sought the appropriate scholars for their study” (ibid). The few public statements by Schøyen in the course of the last 25 years leave the impression that he only has superficial insight into the academic content of the materials he has collected. To the extent there is coherence, this seems to reflect the researchers who counselled him, and the dealers, forgers and looters who sought to meet his demands. What comes across as a driver for Schøyen is praise and recognition from scholars and experts. Flattering expressions of gratitude between collectors and academics are often found in scientific publications and seem to be a strategy for scholars and museums to gain access to collections. Examples of this courtship-like discourse permeate the publications of material in the Schøyen collection, for example: “We must express our great gratitude to MS for his impressive work of collecting manuscripts and, with an exceptional cooperative spirit, making these manuscripts available to the scholarly world. We have all been impressed by his great knowledge of manuscripts (…) but also by the philanthropic spirit which suffuses his cooperation with us (…). Our admiration for MS is enhanced still more by the knowledge that he contributes in the same way to academic work on ancient manuscripts in numerous other fields, such as Classical Antiquity, Assyriology, Sumerology and Biblical Studies (…). Indeed he renders a great service to university milieus all over the world …” [83]. Although perhaps initially comic and submissive flattery, such statements are a further indication of the relevance of Sheik’s critique: the uncritical quest for access to material undermines researcher autonomy. As such, the appeals to “freedom of research” and the actual practices of researchers involved with Schøyen, represent a contradiction between principles and practices.

9. Summing Up and Conclusions

This study is initially about a collector who has been indifferent to provenance when acquiring through dealers. Based on the evidence as it now stands, he also seems to have one way or another been involved with networks of smugglers and looters in Pakistan and Afghanistan, and with dealers who provided objects from Iraq, Palestine, Egypt and beyond, and that authorities in these countries have claimed are illicitly sourced. A number of objects have since been shown to be fakes. In all probability, his purchases have supported criminal networks, engendered the destruction of sites, contexts, and objects, the splitting of manuscripts and dispersal of material. To deflect critical questions, gain public acceptance and access public resources, Schøyen created the fiction of a rescue operation. When challenged, he mostly remained silent or engaged third parties (Braarvig, Rugaas, lawyers and other supporters) who helped “spin” his collection. The next facet of this narrative is the researchers who have been actively involved with authenticating, studying, and publishing material, and enabled Schøyen’s dissemination of his hoaxes and fundamentally Orientalist narrative in defense of his acquisition. Beyond the effect of whitewashing Schøyen and his collection, the academic involvement, of individual scholars as well as public institutions, have probably secured and increased the monetary value of his collection.

The institutions stored objects, supported research, ran databases, provided analyses, published material, and supported Schøyen and his partners. When dubious practices became public, the general institutional policy has apparently been to turn a blind eye. Still, in time many institutions chose to end active and visible support for Schøyen, though none of the involved institutions have investigated what Schøyen has done, how their resources were used or the actions of their employees. The lack of institutional responses entails that Schøyen has continued collecting and exhibiting, and institutions like MF and UiO have continued to host Schøyen’s research, his research group has continued to publish through Hermes and the National Library has approved export licenses with no indications of having conducted any substantial provenance inquiries. Through publication and permits, the whitewashing and promotion of Schøyen and his collection continues up to today.