New and Emerging Challenges to Heritage and Well-Being: A Critical Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Links Between Heritage and Well-Being

“In the 21st century, culture will be what physical activity was for health in the 20th century,” predicts Nathalie Bondil, Montreal Museum of Fine Arts director general, in the Montreal Gazette. The innovative institution is already focused on art and wellness. It created The Art Hive, a community studio supervised by an art therapist where visitors can create themselves, and programming that promotes well-being through art, as well as research collaborations with physicians on the health benefits of museum visits, and a medical consultation room. Now, it’s joining forces with Médecins Francophones du Canada, an association of French-speaking doctors, to allow member physicians to prescribe art. Hélène Boyer, vice president of the medical association, explained to the Gazette: “There’s more and more scientific proof that art therapy is good for your physical health. It increases our level of cortisol and our level of serotonin. We secrete hormones when we visit a museum and these hormones are responsible for our well-being.

2.2. Better Defining Heritage and Well-Being in Relationship to Each Other

Well-being can be defined in many ways, including social, personal, economic, cultural, environmental, psychological, spiritual, physical. Most importantly, it can be viewed as a positive sense of personal and cultural wellness that results from strong cultural identity. Strong cultural identity is underpinned by connection to places, landscapes, tradition, heritage, shared stories and communal histories. Thus, well-being is here defined as a positive sense of psychological, physical, emotional and spiritual satisfaction that results from being part of a culture and community that actively engages with its environment, heritage and traditions. Consequently, when heritage … is damaged, destroyed or threatened the well-being of individuals and communities is negatively impacted.

3. Analysis of Results

3.1. Colonialism and the Erasure of Heritage

3.2. Monuments

The public discussions following Charlottesville on “what to do” with the statue and similar commemorations illuminate several points that are relevant to theoretical understandings of heritage under debate by heritage scholars and practitioners. Firstly, the fallout following Charlottesville provides a lens on the importance of the “cultural” modifier of “cultural heritage,” and secondly, argues for the importance of the public sphere to understandings of what it is that this idea of “heritage” does—what its function is—in modern society.

3.3. Heritage Sustainability

Hul’qumi’num peoples express deep concerns over their inability to maintain their customary laws with regard to the protection of their archaeological heritage. Modern land politics represents a significant challenge for Hul’qumi’num peoples, and it threatens their ability to maintain their historical connections to their lands and, most notably, their ability to protect archaeological sites located on private property. Hul’qumi’num argue that the provincial government and the heritage resource industry are undermining their customary laws, which are what enable them to rightfully and appropriately manage their aboriginal heritage. Although issues external to the community are the primary focus of concern, issues within the community also need to be addressed.

4. Discussion

To understand and work effectively with the intersections between heritage and well-being we need to begin with individuals and communities in local and regional settings. Personal attachments, community celebrations, private distress and public resistance have their origins in taken-for-granted relations that become intensities when they are threatened by change, development or neglect. Often it can be particularly difficult to anticipate where, when and how residents will take action. This unpredictability highlights how locals and visitors are too readily assumed to view heritage in terms of sites and practices of high and deep cultural value – historic, spiritual, aesthetic, architectural, environmental, and popular. Can we establish the heritage value of a surf break? A bush track? The view from the seventy-first floor? A corner store? How is heritage operating when what is at stake is people’s feeling that “the place just won’t be the same”? We can be as much attached to minor heritages – traces and accidents of nature and history – as to conventional repositories of shared meaning. What if we begin by identifying what people value about where they live? That is, let’s ask people how their region caters for their well-being. Their answers to that question will suggest how we might map regional heritage more productively.

Whether for the social performance of memory, trauma, protest, or uplift, a material past is discursively assembled to serve as a physical conduit between past and present. Since sites and objects bear witness to particular pasts and have those histories woven into their very fabric, they physically embody and instantiate the past in the present in a way that no textual account can fully achieve. That being said, we have increasingly come to see what many indigenous communities have long realized and indeed practiced: that these physical landscapes, monuments, and objects cannot be separated from intangible beliefs and resonances. The artificial separation of these traits is itself a symbolic violence. And when the immaterial connection that people experience disappears, the significance of those same sites and objects may also decline in the public imaginary.

Digital Heritage as a Form of Preservation

There is also a danger with working on cultural heritage with digital tools. The problem put simply is that the technology available to animators, designers, programmers and game designers is so powerful that it can take control and produce a past more “real” than the archaeological remains allow. The most extreme forms are some historically based computer games with CGI visuals, but the problem can also extend to many fly-through architectural reconstructions, which form a kind of hyperreal past that demonstrates very well the technical prowess of the designer and the software used, but goes well beyond the archaeological base upon which these reconstructions should be based. The problem is, who is the author of an exhibition or a video - the researcher or the designer? One is the expert for the data, the other for the software? To take sporting analogy is the archaeologist a player manager, a trainer or the referee? I would say the core function is one of referee. Someone who keeps an eye on the rules of academic research and looks out for fair play towards the powerless prehistoric creators of the material record.

The discussion about the value of virtual reconstruction for the preservation and interpretation of cultural heritage has only just started. Should these virtual simulations be considered original digital representations of our cultural heritage or just virtual “fakes”? They can probably be considered subjective virtual interpretations (a relative “authentic”) that aim to get as close as possible to the absolute “authentic” thanks to the activation of a multisimulation process and the creation of “open” and “dynamic” ontologies. This kind of process can allow users to compare, virtually and in real time, different reconstructed worlds that result from diverse interpretations of the same cultural heritage and to then change them and create new interpretations. New digital methodologies can facilitate the preservation of our material memory and, at the same time, help to remove the barriers between past and present through innovative and open communication systems.

5. Conclusions

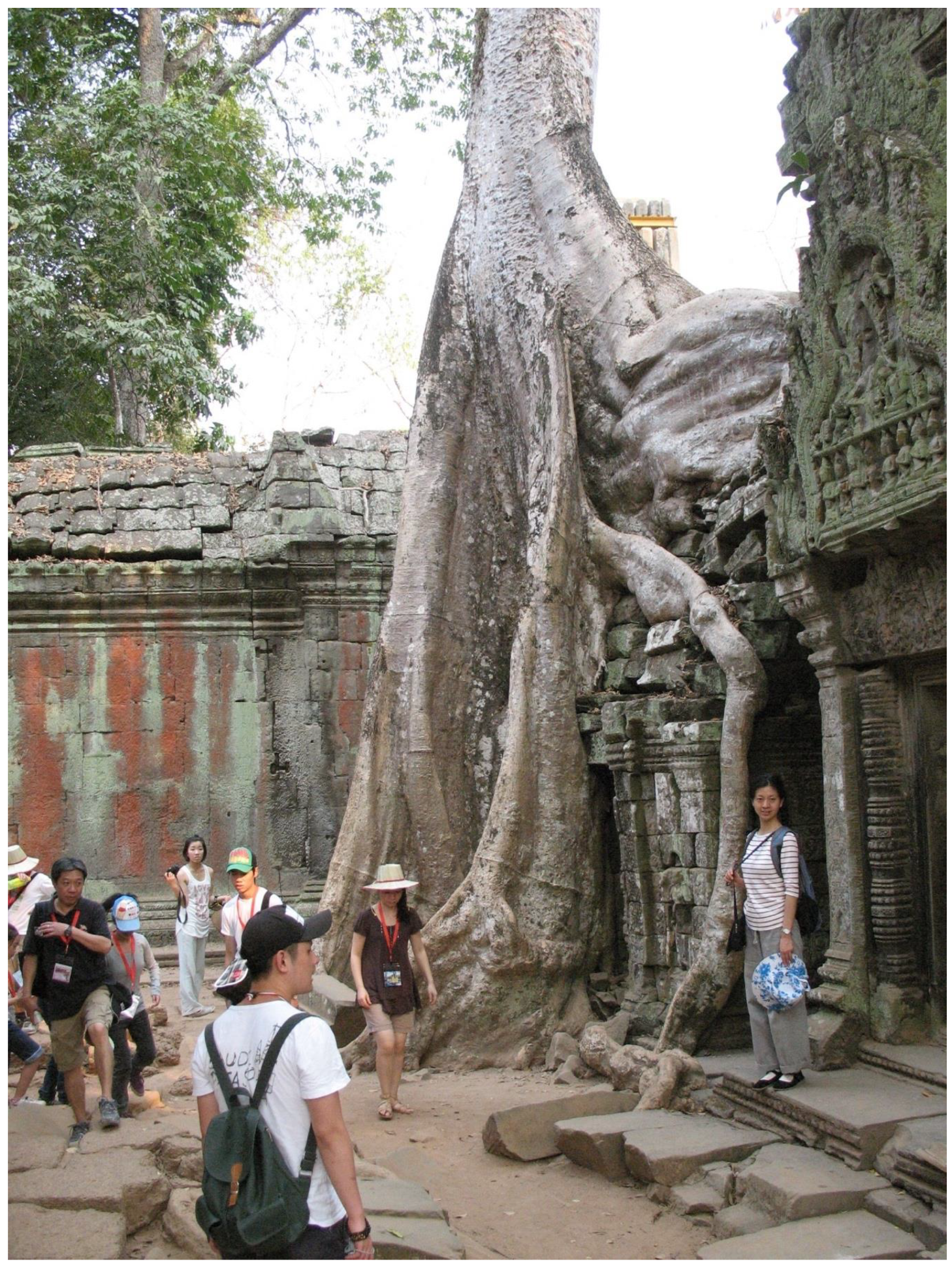

A regional comparison of traditional heritage management reveals a shared principle of usable and living heritage. Heritage places such as Timbuktu, Aksum, Great Zimbabwe, and Kilwa, among others, were not left to decay, waiting for “discovery” by foreign heritage experts. Many archaeological sites and ruins, for example Anuradhapura in Sri Lanka, Lumbini in Nepal, Bodhgaya in India, and many other sites, are still places of worship and pilgrimage and are considered sacred by millions of Buddhists. These places contain archaeological remains dating back to the third century BCE, but their sacredness adds a different set of values and conservation challenges. Most of these places still play major roles as part of a dynamic cultural landscape whose meaning is derived from its wider social and religious context.

- Principle 1

- Principle 2

- Principle 3

- Principle 4

- Principle 5

- Principle 6

- Principle 7

- Principle 8

A living heritage approach tends to radically redefine the existing concept of heritage and the principles of heritage conservation by challenging, for the first time in the history of conservation, very strong assumptions established over time in the field, which were developed along with a material-based approach and were maintained by a values-based approach… More specifically, according to a living heritage approach, first, the power in the conservation process is [no] longer in the hands of the conservation professionals, but passes on to the communities. Second, emphasis is no longer on the preservation of the (tangible) material but on the maintenance of the (intangible) connection of communities with heritage, even if the material might be harmed. Third, heritage is not considered a monument of the past that has to be protected from the present community, for the sake of future generations; heritage is now seen and protected as an inseparable part of the life of the present community. Thus, past and present-future are not separated (discontinuity), but unified into an ongoing present (continuity). Therefore, a living heritage approach attempts to mark the shift in heritage conservation from monuments to people, from the tangible fabric to intangible connections with heritage, and from discontinuity to continuity.

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chatterjee, H.; Noble, G. Museums, Health and Well-being; Ashgate: Farnham, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Dasgupta, P. Human Well-Being and the Natural Environment; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Waterton, E.; Watson, S. Heritage and Community Engagement: Collaboration or Contestation; Routledge: Milton Park, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Sayer, F. Can digging make you happy? Archaeological excavations, happiness and heritage. Arts Health 2015, 7, 247–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, A.; Smyth, K. Heritage, health and place: The legacies of local community-based heritage conservation on social wellbeing. Health Place 2016, 29, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossi, E.; Blessi, G.T.; Sacco, P.L. Magic moments: Determinants of stress relief and subjective wellbeing from visiting a cultural heritage site. Cult. Med. Psychiat. 2019, 43, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fairclough, G.; Harrison, R.; Jameson Jnr, J.H.; Schofield, J. The Heritage Reader; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, B.; Howard, P. The Ashgate Research Companion to Heritage and Identity; Ashgate: Farnham, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Logan, W.; Craith, M.N.; Kockel, U. A Companion to Heritage Studies; Wiley Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Waterton, E.; Watson, S. The Palgrave Handbook of Contemporary Heritage Research; Palgrave: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Taçon, P.S.C. Connecting to the Ancestors: Why rock art is important for Indigenous Australian and their well-being. Rock Art Res. 2019, 36, 5–14. [Google Scholar]

- Gražulevičiūtė, I. Cultural heritage in the context of sustainable development. Environ. Res. Eng. Manag. 2006, 3, 74–79. [Google Scholar]

- Fujiwara, D.; Lawton, R.; Mouratao, S. The Health and Well-Being Benefits of Public Libraries. Full Report; Arts Council England: Manchester, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ander, E.; Thomson, L.; Noble, G.; Lanceley, A.; Menon, U.; Chatterjee, H. Heritage, health and wellbeing: Assessing the impact of a heritage focused intervention on health and wellbeing. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2009, 19, 229–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, M. Museums and restorative justice: Heritage, repatriation and cultural education. Mus. Int. 2018, 61, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, D. Partnerships in the heritage of the displaced. Mus. Int. 2004, 224, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, D.; Nugent, M. Mapping Attachment: A Spatial Approach to Aboriginal Post-Contact Heritage; Department of Environment and Conservation: Hurstville, Australia, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Carrington, B.; Young, P. Aboriginal Heritage and Wellbeing; Department of Environment, Climate Change and Water (NSW): Sydney South, Australia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Grieves, V. Indigenous Wellbeing: A Framework for Governments’ Aboriginal Cultural Heritage Activities; Department of Environment and Conservation: Hurstville, Australia, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Sutton, M.-J.; Huntley, J.; Anderson, B. “All our sites are of high significance”, reflections from recent work in the Hunter Valley—Archaeological and Indigenous Perspectives. J. Aust. Assoc. Consult. Archaeol. 2013, 1, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Brady, L.; Taçon, P. Relating to Rock Art in the Contemporary World: Navigating Symbolism, Meaning and Significance; University Press of Colorado: Boulder, CO, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Oldenburg, R. The Great Good Place: Cafes, Coffee Shops, Bookstores, Bars, Hair Salons, and Other Hangouts at the Heart of a Community; Hachette Books: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, S. Community Custodians of Popular Music’s Past: A DIY Approach to Heritage; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Istvandity, L.; Baker, S.; Collins, J.; Driessen, S.; Strong, C. Understanding popular music heritage practice through the lens of third place. In Rethinking Third Places: Informal Public Spaces and Community Building; Dolley, J., Bosman, C., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cantillon, Z.; Baker, S. DIY heritage institutions as third places: Caring, community and wellbeing among volunteers at the Australian Jazz Museum. Leis. Sci. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monckton, L.; Reilly, S. Wellbeing and historic environment: Why bother? Exploring the relationship between wellbeing and the historic environment. Hist. Engl. Res. 2018, 11, 6–17. [Google Scholar]

- Fujiwara, D.; Cornwall, T.; Dolan, P. Heritage and Wellbeing; English Heritage: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Maeer, G.; Robinson, A. Values and Benefits of Heritage: A Research Review; Heritage Lottery Fund Strategy and Business Development Department: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Frogett, L.; Roy, A. Cultural Attendance and Public Mental Health: Evaluation of Pilot Programme 2012–14; Manchester City Council: Manchester, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Livni, E. Doctors in Montreal Can Now Prescribe a Visit to an Art Museum. World Economic Forum (26 October 2018). Available online: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2018/10/doctors-in-montreal-will-start-prescribing-visits-to-the-art-museum (accessed on 25 March 2019).

- Agnew, N.; Deacon, J.; Hall, N.; Little, T.; Sullivan, S.; Taçon, P.S.C. Rock Art: A Cultural Treasure at Risk; The Getty Conservation Institute: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, M.; Taçon, P.S.C. Past and present, traditional and scientific: The conservation and management of rock art sites in Australia. In Open-Air Rock-Art Conservation and Management: State of the Art and Future Perspectives; Darvill, T., Fernandes, A.P.B., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; pp. 214–228. [Google Scholar]

- Taçon, P.S.C.; Marshall, M. Conservation or Crisis? The Future of Rock Art Management in Australia. In A Monograph of Rock Art Research and Protection; Zhang, Y., Ed.; China Tibetology Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2014; pp. 119–141. [Google Scholar]

- Sayer, F. Understanding well-being: A mechanism for measuring the impact of heritage practice on well-being. In The Oxford Handbook of Public Heritage Theory and Practice; Labrador, A.M., Silberman, N.A., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Darvill, T. Value systems in archaeology. In Managing Archaeology; Cooper, M.A., Firth, A., Carman, J., Wheatley, D., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 1995; pp. 40–50. [Google Scholar]

- Holtorf, C. From Stonehenge to Las Vegas: Archaeology as Popular Culture; Altamira Press: Oxford, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Renfrew, C. Figuring it Out: What are We? Where Do we Come from? Thames and Hudson: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- The EuroQol Group. EuroQol: A new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy 1990, 16, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, D.; Clark, L.A.; Tellegen, A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scale. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 54, 1063–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraro, E.; Barletti, J.P.S. Place wellbeing: Anthropological perspectives on wellbeing and place. Anthropol. Action 2016, 23, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarandona, J.A.G. The destruction of heritage: Rock art in the Burrup Peninsula. Int. J. Hum. 2011, 9, 325–342. [Google Scholar]

- Cunliffe, E.; Curini, L. ISIS and heritage destruction: A sentiment analysis. Antiquity 2018, 92, 1094–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isakhan, B.; Meskell, L. UNESCO’s project to “Revive the spirit pf Mosul”: Iraqi and Syrian opinion on heritage after the Islamic State. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahab, S.; Isakhan, B. The ritualization of heritage destruction under Islamic State. J. Soc. Archaeol. 2018, 18, 212–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarandina, J.A.G.; Albarrán-Torres, C.; Isakhan, B. Digitally mediated iconoclasm: The Islamic State and the war on cultural heritage. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2018, 24, 649–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobbs, C. Australia’s Assault on Norfolk Island, 2015–2016: Despatches from the Front Line; Chris Nobbs: Burnt Pine, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Samuels, K.L. Deliberate heritage: Difference and disagreement after Charlottesville. Public Hist. 2019, 41, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, G. The Battle over Confederate Statues, Explained. Vox. August 2017. Available online: https://www.vox.com/identities/2017/8/16/16151252/confederate-statues-white-supremacists (accessed on 25 September 2017).

- Grant, S. It is a “damaging myth” that Captain Cook discovered Australia. ABC News. 23 August 2017. Available online: http://www.abc.net.au/mews/2017-08-23/stan-grant:-damaging-myth-captain-cook-discovered-australia/8833536 (accessed on 25 September 2017).

- Barnabas, S. Engagement with colonial and apartheid narratives in contemporary South Africa: A monumental debate. J. Lit. Stud. 2016, 32, 109–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLay, E.; Bannister, K.; Joe, L.; Thom, B.; Nicholas, G. A’lhut tut et Sul’hweentst [Respecting the ancestors]: Understanding Hul’qumi’num heritage laws and concerns for the protection of archaeological heritage. In First Nations Cultural Heritage and Law: Case Studies, Voices and Perspectives; Bell, C., Napoleon, V., Eds.; UBC Press: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2008; pp. 158–202. [Google Scholar]

- Auclair, E.; Fairclough, G. Living between past and future: an introduction to heritage and cultural sustainability. In Theory and Practice in Heritage and Sustainability: Between Past and Future; Auclair, E., Fairclough, G., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Barthel-Bouchier, D. Cultural Heritage and the Challenge of Sustainability; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, S.; Collins, J. Popular music heritage, community archives and the challenge of sustainability. Int. J. Cult. Stud. 2017, 20, 476–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willman, C. Musicians Freak Out as They Belatedly Learn Myspace Lost 50 Million Songs. Variety. 18 March 2019. Available online: https://variety.com/2019/music/news/myspace-music-data-loss-50-million-songs-1203165649/ (accessed on 29 March 2019).

- Gao, Q. Social values and rock art tourism: An ethnographic study of the Huashan Rock Art Area (China). Conserv. Manag. Archaeol. Sites 2017, 19, 82–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, N.B.; Zhu, Y. Heritage and tourism. In Global Heritage: A Reader; Meskell, L., Ed.; Wiley Blackwell: Chichester, UK, 2015; pp. 240–258. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, D.; Perry, J. (Eds.) The Future of Heritage as Climates Change: Loss, Adaptation and Creativity; Routledge: Milton Park, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Högberg, A.; Holtorf, C. Heritage futures and the future of heritage. In Counterpoint: Essays in Archaeology and Heritage Studies in Honour of Professor Kristian Kristiansen; Bergerbrant, S., Sabatini, S., Eds.; Archaeopress: Oxford, UK, 2013; pp. 739–746. [Google Scholar]

- Högberg, A.; Holtorf, C.; May, S.; Wollentz, G. No future in archaeological heritage management? World Archaeol. 2018, 49, 639–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wise, P. Minor heritage matters: understanding well-being in the Gold Coast Tweed region. Presented at the “New and Emerging Challenges to Heritage and Well-Being” conference, Griffith University, Gold Coast, QLD, Australia, 23 November 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Katriel, T. “Our future is where our past is”: Studying heritage museums as ideological and performative arenas. Commun. Monogr. 1993, 60, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meskell, L. Introduction: Globalizing heritage. In Global Heritage: A Reader; Meskell, L., Ed.; Wiley Blackwell: Chichester, UK, 2015; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Stanco, F.; Battiato, S.; Gallo, G. Digital Imaging for Cultural Heritage Preservation; CRC Press Inc.: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Beer, D.; Burrows, R. Popular culture, digital archives and the new social life of data. Theory Cult. Soc. 2013, 4, 47–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolick, C.M. Digital archives: Democratizing the doing of history. Int. J. Soc. Educ. 2006, 21, 122–134. [Google Scholar]

- Featherstone, M. Archiving cultures. Brit. J. Sociol. 2000, 51, 161–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieraccini, M.; Guidi, G.; Atzeni, C. 3D digitizing of cultural heritage. J. Cult. Herit. 2001, 2, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silberman, N.A. Beyond theme parks and digitized data: What can cultural heritage technologies contribute to the public understanding of the past? In Proceedings of the VAST: 5th International Symposium on Virtual Reality, Archaeology and Intelligent Cultural Heritage, Brussels and Oudenaarde, Belgium, 7–10 November 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Lerma, J.L.; Navarro, S.; Cabrelles, M.; Villaverde, V. Terrestrial laser scanning and close range photogrammetry for 3D archaeological documentation: The Upper Palaeolithic Cave of Parpalló as a case study. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2010, 37, 499–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, T.; Chalmers, A.; Díaz-Andreu, M.; Ellis, G.; Longhurst, P.; Sharpe, K.; Trinks, I. 3D laser scanning for recording and monitoring rock art erosion. Int. Newsl. Rock Art 2005, 41, 24–29. [Google Scholar]

- Chandler, J.H.; Bryan, P.; Fryer, J.G. The development and application of a simple methodology for recording rock art using consumer-grade digital cameras. Photogramm. Rec. 2007, 22, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Hakim, S.F.; Fryer, J.; Picard, M. Modeling and visualization of Aboriginal rock art in the Baiame Cave. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2004, 35, 990–995. [Google Scholar]

- Di Maida, G. 3D in the cave: Hey young deer, why the long face (and no tail)? Rock Art Res. 2016, 33, 209–281. [Google Scholar]

- Domingo, I.; Villaverde, V.; López-Montalvo, E.; Lerma, J.L.; Cabrelles, M. Latest developments in rock art recording: Towards an integral documentation of Levantine rock art sites combining 2D and 3D recording techniques. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2013, 40, 1879–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraile, F.J.L.; García, L.M.G.; Klink, A.C. Documentation and use of DStretch for two New Sites with Post-Palaeolithic Rock Art in Sierra Morena, Spain. Rock Art Res. 2016, 33, 127–142. [Google Scholar]

- González-Aguilera, D.; Muñoz-Nieto, A.; Gómez-Lahoz, J.; Herrero-Pascual, J.; Gutierrez-Alonso, G. 3D digital surveying and modelling of cave geometry: Application to Paleolithic rock art. Sensors 2009, 9, 1108–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalandoni, A.; Domingo Sanz, I.; Taçon, P.S.C. Testing the value of low-cost Structure-from-Motion (SfM) photogrammetry for metric and visual analysis of rock art. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2018, 17, 605–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haubtm, R.; Taçon, P.S.C. A collaborative, ontological and information visualization model approach in a centralized rock art heritage platform. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2016, 10, 837–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, D.; Dalgity, A.; Avramides, I. The arches heritage inventory and management system: A platform for the heritage field. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2016, 6, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, M.L.; Flores Gutierrez, M.; Coughenour, C.; Lopez-Menchero Bendicho, V.M.; Remondino, F.; Fritsch, D. Crowd-sourcing the 3D digital reconstructions of lost cultural heritage. Dig. Herit. 2015, 1, 171–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, M.; Dowsland, S.; Mazel, A.; Giesen, M. Rock art CARE: A cross-platform mobile application for crowdsourcing heritage conservation data for the safeguarding of open-air rock art. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2018, 8, 420–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, F. Rock-art and digital difference. In Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on Cultural Heritage and New Technologies 2014, Vienna, Austria, 2014; Börner, W., Uhlirz, S., Eds.; Museen der Stadt Wien: Vienna, Austria, 2014; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Galeazzi, F. 3-D virtual replicas and simulations of the past. “Real” or “fake” representations? Curr. Anthropol. 2018, 59, 268–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stobiecka, M. Digital escapism: How objects become deprived of matter? J. Contemp. Archaeol. 2018, 5, 194–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J. Archaeology and Modernity; Routledge: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Taçon, P.S.C. The Creativity Centre: Where art meets science. In Between Indigenous Australia and Europe: John Marwurndjul; Volkenandt, C., Kaufmann, C., Eds.; Aboriginal Studies Press/Reimer: Canberra, Australia; Berlin, Germany, 2009; pp. 211–216. [Google Scholar]

- Colwell, C.; Joy, C. Communities and ethics in the heritage debates. In Global Heritage: A Reader; Meskell, L., Ed.; Wiley Blackwell: Chichester, UK, 2015; pp. 112–130. [Google Scholar]

- Ndoro, W.; Wijesuriya, G. Heritage management and conservation: From colonization to globalization. In Global Heritage: A Reader; Meskell, L., Ed.; Wiley Blackwell: Chichester, UK, 2015; pp. 131–149. [Google Scholar]

- National Trust. Places that Make Us—Research Report; National Trust: Swindon, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, C.; Ralph, J.; Notre Dame: How a Rebuilt Cathedral Could be just as Wonderful. Notre Dame: How a Rebuilt Cathedral Could be just as Wonderful. The Conversation. 16 April 2019. Available online: http://theconversation.com/notre-dame-how-a-rebuilt-cathedral-could-be-just-as-wonderful-115551 (accessed on 17 April 2019).

- DeSilvey, C. Curated Decay: Heritage Beyond Saving; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, R. Forgetting to remember, remembering to forget: Late modern heritage practices, sustainability and the ‘crisis’ of the accumulation of the past. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2011, 19, 579–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulios, I. The Past in the Present: A Living Heritage Approach—Meteora, Greece; Ubiquity Press: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Taçon, P.S.C.; Baker, S. New and Emerging Challenges to Heritage and Well-Being: A Critical Review. Heritage 2019, 2, 1300-1315. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage2020084

Taçon PSC, Baker S. New and Emerging Challenges to Heritage and Well-Being: A Critical Review. Heritage. 2019; 2(2):1300-1315. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage2020084

Chicago/Turabian StyleTaçon, Paul S.C., and Sarah Baker. 2019. "New and Emerging Challenges to Heritage and Well-Being: A Critical Review" Heritage 2, no. 2: 1300-1315. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage2020084

APA StyleTaçon, P. S. C., & Baker, S. (2019). New and Emerging Challenges to Heritage and Well-Being: A Critical Review. Heritage, 2(2), 1300-1315. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage2020084