Douro Carboniferous System: Integration of the Built Environment Heritage Aspect within the Territorial Planning Framework

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- The key role they played in SCD, not only due to the productive structures involved but also due to the urban structure they established and constituted (criterion ii, iii);

- The concentration of representative structures within a given period and the form of building due to a technological response to the productive structure (criterion iv);

- The recognition of the population when confronted with the patrimonial identification and its documental characterization (authenticity);

- The conservation up to the present day of most of the constituent structures of the core able to be organized as such (integrity).

3. Results

4. Discussion

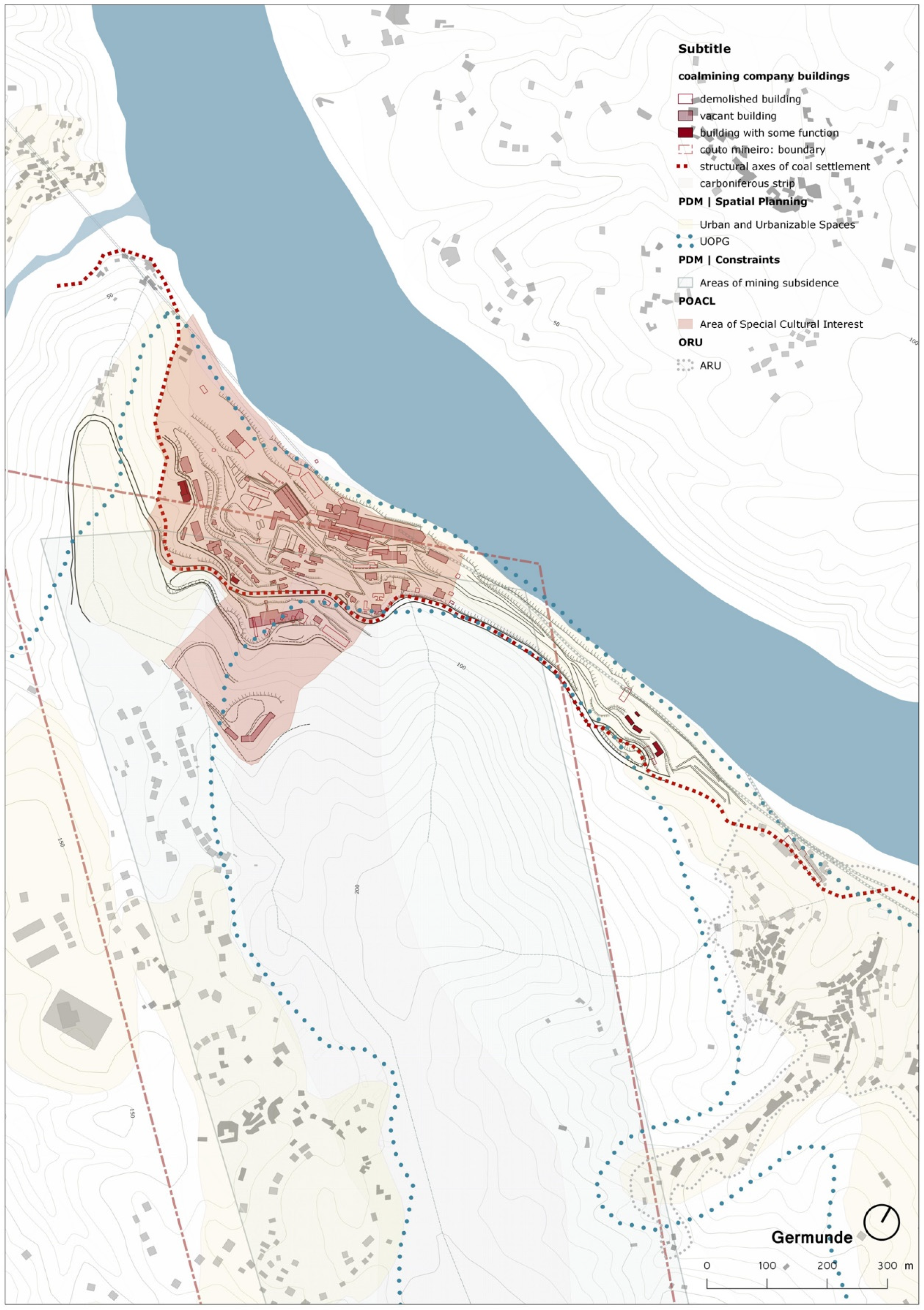

- The Carboniferous structures are recognized within a heritage understanding both through its classification as “Monument of Public Interest”, in the case of the Cavalete de S. Vicente and surrounding area (S. Pedro da Cova), as shown in Figure 4, and as “Area of Special Cultural Interest (Área de Especial Interesse Cultural (AEIC))” (POACL) in the case of the Germunde core, as shown in Figure 5.

- The concept of heritage takes on distinct shapes [35] gaining greater weight in the territorial management instruments of the current generation of PDM. At the same time, this investment in heritage as a factor of differentiation and territorial competitiveness [21] is affirmed by the definition of ARU, as exemplified by ARUs in or near the nuclei addressed.

- The SCD fragments are not understood within a wholistic logic but rather, within a piecemeal view determined by the individual value of each of the physical structures inherent to this system. The idea of landscape as a result of history acting on the territory [36] loses power in the context of land planning and thus equating the heritage issue in a disjointed way to the logics that structured it as such, as shown in Figure 8.

- The “structural invariants” [13] which determined the territory and the identifying role which the population assigned to them are integrated into the planning and land management instruments in a passive manner being given a rather inconsequential, although binding, role in endogenous development. This is referring to the built structures but also to logistics involving the connectivity and articulation of different centralities [39] by which the SCD determined.

- An understanding of the rules of growths linked to the identity of each place as enhancing transformation would be a valid response to the envisaged urban renewal [18] extending the intervention in buildings and promoting individual and collective re-appropriation of the place.

- The autonomy that allowed the nuclei to develop as a centrality concentrated around key functions and agglutinating the structures that guaranteed a response to the daily life of those who inhabited it and gives rise to hierarchical and disjointed nuclei within the municipal structure with little consequence for the guarantor in the quality of life.

- The priority given to urban fabrics to be renewed is influenced by the financing instruments, one of the most determining factors on landscape transformation currently [40]. Within the 2020 funding framework ARU on the riverfront, as shown in Figure 7, Abandoned Industrial Areas and Historical Centers (through Instrumento Financeiro para a Reabilitação e Revitalização Urbanas (IFRRU)) have been given priority [41]. Hence, in the ARU delimitation that was referred to it was hardly articulated with the logics of the structuring of urban settlement and the risk that in a few years there will be a series of “ghost” structures/equipment, without promoting any effective rehabilitation of the urban fabric within which they are integrated (Figure 9).

- There are no operational units capable of covering the logistics of construction/transformation of the territory in a unitary and systemic way and encompassing a municipal vision. As a unit to program the transformation of the territory this should be subjugated to a planning logic determined by its construction [23], underlying the understanding of the SCD landscape. Although provided for in the Legal Regime of Territorial Management Instruments (Regime Jurídico dos Instrumentos de Gestão Territorial (RJIGT)) [42], the intermunicipal scope that should be thought of concerning territorial transformation has not yet been considered and has already happened in countries with regional self-governments [22,25].

5. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ivancic, A. Energyscapes; Gustavo Gili: Barcelona, Spain, 2010; ISBN 9788425222726. [Google Scholar]

- Nadaï, A.; van der Horst, D. Introduction: Landscapes of Energies. Landsc. Res. 2010, 35, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves Ribeiro, D. Territories of energy production and landscape heritage. The Coal Basin of Douro. Joelho, Revista de Cultura Arquitectónica 2015, 6, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves Ribeiro, D. (Infra)estruturas de Produção Energética. O Carvão no Sistema Urbano do Porto; Grant Report of the Programa Millennium de Bolsas de Investigação na Área da Cidade e da Arquitetura, 2016; Fundação da Juventude, Ordem dos Arquitectos, Município do Porto, Milenium BCP: Porto, Portugal, unpublished.

- Lemos de Sousa, J.M. Contribuição para o conhecimento da Bacia Carbonífera do Douro. Dissertação de Doutoramento em Geologia, Universidade do Porto, Porto, Portuga, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Macedo, M. Projectar e Construir a Nação. Engenheiros, Ciência e território em Portugal no século XIX; Imprensa de Ciências Sociais: Lisboa, Portugal, 2012; ISBN 9789726712954. [Google Scholar]

- Magnaghi, A. Il Progetto Locale. Verso la Coscienza di Luogo; Bollati Boringhieri Editore: Torino, Italy, 2017; ISBN 9788833921501. [Google Scholar]

- Gregotti, V. Il Territorio dell’ Architettura; Feltrinelli: Milano, Italy, 2008; ISBN 9788807720017. [Google Scholar]

- Rossa, W. Património Urbanístico: (Re)fazer Cidade Parcela a Parcela; Sumário Pormenorizado da lição Apresentado para Provas de Agregação; Universidade de Coimbra: Coimbra, Portugal, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Choay, F. L’urbanisme: Utopies et Réalités. Une Anthologie; Éditions du Seuil: Paris, France, 1979; ISBN 9782020053280. [Google Scholar]

- Sauer, C.O. La morfología del paisaje. Polis, Revista de la Universidad Bolivarian 2006, 5, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Corboz, A. El territorio como palimpsesto. In LO Urbano; Martín Ramos, Ángel, Ed.; Edicions de la Universitat Politécnica de Catalunya, Ed.: Barcelona, Spain, 2004; ISBN 8483017520. [Google Scholar]

- Maggio, M. Invarianti Strutturali nel Governo del Territorio; Firenze University Press: Firenze, Italy, 2014; Volume 22, ISBN 9788866556299. [Google Scholar]

- Barba, R. El Proyeto del Lugar. In Rosa Barba Casanovas. 1970–2000. Obras y Escritos; AS Flor Ediciones: Barcelona, Spain, 2010; pp. 114–124. ISBN 9788461438013. [Google Scholar]

- Territorial Agenda of the European Union 2020; Toward an Inclusive, Smart and Sustainable Europe of Diverse Regions; Agreed at the Informal Ministerial Meeting of Ministers responsible for Spatial Planning and Territorial Development; European Union (EU): Gödöllő, Hungary, 2011.

- PNPOT, Alteração. Uma Agenda para o Território (Programa de Ação); Território, Direcção Geral do Território: Lisboa, Portugal, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Henriques, E.B. Opatrimónio nas Políticas Territoriais. In Proceedings of the V Congresso da Geografia Portuguesa; Portugal: Territórios e Protagonistas, Guimarães. Available online: http://www.apgeo.pt/files/docs/CD_V_Congresso_APG/web/_pdf/E5_14Out_Eduardo%20Brito%20Henriques.pdf (accessed on 30 November 2018).

- Plano Director Municipal de Castelo de Paiva (Resolução de Conselhos de Ministros n.º 68/1995); Diário da República I Série- B, n. º163; Governo de Portugal: Lisboa, Portugal, 1995.

- Alteração do Plano Diretor Municipal de Gondomar (Aviso n.º3337/2018); Diário da República, 2.ª Série—N.º 51; Governo de Portugal: Lisboa, Portugal, 2018.

- Plano de Ordenamento da Albufeira de Crestuma-Lever (Resolução de Conselhos de Ministros n.º 187/2007); Diário da República, 1.ª Série—N.º 246; Governo de Portugal: Lisboa, Portugal, 2007.

- Regime Jurídico da Reabilitação Urbana (Lei, n.º Lei n.º 32/2012); Diário da República n.º 157/2012, 1.ª Série; Governo de Portugal: Lisboa, Portugal, 2012.

- Norme per il Governo del Territorio, Proposta di Legge Regionale (L. R n.º 5/1995); Bollettino Ufficiale della Regione Toscana - n. 6; Giunta Regionale della Toscana: Firenze, Italy, 1995.

- Regole e Progetti per il Paesaggio. Verso il Nuovo Piano Paesaggistico Della Toscana; Poli, D. (Ed.) Università degli Studi di Firenze, Facoltà di Architettura: Firenze, Italy, 2012; ISBN 9788866551577. [Google Scholar]

- Piano Paesaggistico Territoriale Regionale della Puglia; Bollettino Ufficiale della Regione Puglia - n. 40; Giunta Regionale della Puglia: Bari, Italy, 2015.

- Pla Director Urbanístic de les Colònies del Llobregat. Géneralitat de Catalunya; Departament de Politica Territorial Obres Publiques, Direcció General d’Urbanisme. Comissiò d’ Urbanisme de Catalunya: Barcelona, Spain, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Codice dei beni Culturali e del Paesaggio; Decreto Legislativo n. 42, del 22 gennaio; Repubblica Italiana: Roma, Italy, 2004.

- The Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention; UNESCO World Heritage Centre: Paris, France, 2017.

- Box, P. GIS and Cultural Resource Management: A Manual for Heritage Managers; Dixon, S., Ed.; UNESCO: Bangkok, Thailand, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Cordovez, R.R.T. Aplicaciones Informaticas al Proyecto Urbano; Universidad Politécnica de Valencia: Valencia, Spain, 2008; ISBN 9788483632543. [Google Scholar]

- Legislação Mineira; Decreto n.º 18713/1930; Direcção Geral de Minas e Serviços Geológicos, Governo de Portugal: Lisboa, Portugal, 1930.

- Alves Ribeiro, D. Estruturas territoriais do carvão: Do espaço produtivo ao espaço social. In Proceedings of the X Congresso Docomomo Ibérico: O Fundamento Social da Arquitetura; do Vernáculo e do Moderno, uma Síntese Cheia de Oportunidades, Badajoz, Spain, 18–20 April 2018. accepted. [Google Scholar]

- Operação de Reabilitação Urbana de S. Pedro da Cova e Fânzeres; Município de Gondomar: Gondomar, Portugal, 2018.

- Programa Estartégico de Reabilitação Urbana; Município de Castelo de Paiva: Castelo de Paiva, Portugal, 2017.

- Classificação do Cavalete de S. Vicente como Monumento de Interesse Público (Portaria n.º 221/2010); Diário da República, 2.ª Série—N.º 55; Governo de Portugal: Lisboa, Portugal, 2010.

- Tarrafa, A. Historic Urban Landscape approach and spatial planning. Exploring the integration of heritage issues in local planning in Portugal. Dissertação de Mestrado, Instituto Superior Técnico, Lisboa, Portugal, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zampieri, L. Per um Progetto nel Paesaggio; Quodlibet: Macerata, Italy, 2012; ISBN 9788874624416. [Google Scholar]

- Vanderhülst, G. Industry, man and Landscape. In Proceedings of the TICCIH Congress 1990, Industry, Man and Landscape, Bruxelles, Belgium, 3–8 September 1990; pp. 28–50. [Google Scholar]

- Lei de Bases do Património Cultural (Lei n.º 107/2001); Diário da República n.º 209/2001, Série I-A; Governo de Portugal: Lisboa, Portugal, 2001.

- Portas, N. Da Estratégia ao Projecto. In Nuno Portas, Escritos 1975-2012. Os Tempos das Formas; Volume II: A -cidade Imperfeita e a Fazer; Oliveira, I., Bandeira, P., Eds.; Escola de Arquitectura da Universidade do Minho: Guimarães, Portugal, 2012; pp. 87–101. ISBN 9789899616356. [Google Scholar]

- Il Paesaggio nel Governo del Territorio: Riflessioni sul Piano Paesaggistico Della Toscana; Morisi, M.; Poli, D.; Rossi, M. (Eds.) Firenze University Press: Firenze, Italy, 2018; ISBN 9788864536699. [Google Scholar]

- Programa de Ação IFRRU 2020; Estrutura de Gestão do Instrumento Financeiro para a Reabilitação e Revitalização Urbanas: Lisboa, Portugal, 2017.

- Regime Jurídico dos Instrumentos de Gestão Territorial (Lei n.º 80/2015); Governo de Portugal: Lisboa, Portugal, 2015.

| Nuclei | Plans | Strategic Urban Rehabilitation Programme | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PDM | POACL | |||

| Spatial Planning Charter | Charter of Constraints | |||

| Germunde (does not include malt house) | -Urban and Urbanizable Spaces: Urban Agglomerates, Consolidated Areas -Urban and Urbanizable Spaces: Areas of urban expansion Within the UOPG 8 | -Areas of mining subsidence -Coal mining concession -REN 1 safeguard area | Areas protecting and valorizing specific resources and values: Protection Area, Area of Special Cultural Interest | Not integrated 2 |

| S. Pedro da Cova | -Rural land: cultural spaces -Urban land: urbanized land—areas of economic activities -Urban land, urbanized land—structuring equipment spaces” -Urban land, urbanized land—Type I residential areas -Essential municipal ecological structure: others | -Cavalete de S. Vicente: Monument of public interest -REN safeguard area | Not covered | S. Pedro das Cova e Fânzeres ARU |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alves Ribeiro, D. Douro Carboniferous System: Integration of the Built Environment Heritage Aspect within the Territorial Planning Framework. Heritage 2019, 2, 104-120. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage2010008

Alves Ribeiro D. Douro Carboniferous System: Integration of the Built Environment Heritage Aspect within the Territorial Planning Framework. Heritage. 2019; 2(1):104-120. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage2010008

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlves Ribeiro, Daniela. 2019. "Douro Carboniferous System: Integration of the Built Environment Heritage Aspect within the Territorial Planning Framework" Heritage 2, no. 1: 104-120. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage2010008

APA StyleAlves Ribeiro, D. (2019). Douro Carboniferous System: Integration of the Built Environment Heritage Aspect within the Territorial Planning Framework. Heritage, 2(1), 104-120. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage2010008