1. Introduction

Cities are one of the most sophisticated forms of human creation. They are always in the making [

1], in a constant state of formation, never complete, and involve construction, demolition, and reconstruction in an endless fashion. Growth, restructuring, and decline result in ubiquitous ruptures in the urban surface. Thus human coexistence with building sites, new structures, abandoned constructions, ruins, and voids are as old as cities. Evidently, at certain moments in time and in very specific locations, urban restructuring has occurred at a large scale and rapidly. As a result of the collapse of the Soviet Bloc, for example, many urban spaces have suffered tremendous changes. As Garcia-Allyon [

2] (p. 29) argues, “urbanism from the planned socialist economy has often been replaced by strong and accelerated urbanization processes of neoliberal economies with common issues and specific casuistries of each territory”. Also during the 1970s and early 1980s the impact of post-industrial economies in the West, and the introduction of neoliberal economies, have produced many derelict urban areas. These have come to be part of our contemporary urban landscapes. At the same time, and focusing in Europe, we cannot neglect the fact of population decline in the last decades. Turok’s and Mykhnenko’s [

3] work illustrates how nearly one third of European cities over 200,000 inhabitants has lost population at least for one decade, over the past 45 years. In fact, most of these cities began to lose population in the 1980s and 1990s, and many as a result of suburbanization. While ‘shrinking’ has become a common feature in contemporary urban landscapes in much of Europe, and it is closely tied with population decline, it also reveals the decline of physical and socio-spatial structures, which are perceived through, among other things, high rates of unoccupied and vacant properties and the existence of large brownfields [

4]. Furthermore, while there is no single model or archetype of the ‘shrinking city’ [

5], research reveals how shrinking is a global phenomenon. Thus, many commentators note that our coexistence with ruins, voids, and dereliction, is stronger in contemporary urbanity [

6,

7], possibly due to the urbanization levels we experience in the 21st century and as a result of the increasing pressures that neoliberal capitalist models inflict in cities. Viewing property as a form of accumulation strategy, of fixing capital in space for later usage [

8], stimulates an urban design which encompasses vacant land and suspended projects waiting for development. At the same time, the levels of real estate speculation of the last decades have promoted a discontinuous growth of cities. In many places we have witnessed the construction of urban infrastructures aiming at replicating housing estates. With the financial crisis that strongly affected real estate expansion after 2008, many of the projects consolidated as expectant land and capital accumulation repositories, remain frozen or on waiting. Others, however, saw their construction interrupted for a variety of reasons (ranging from bankruptcy of construction firms, failures in financial mechanisms, to lack of buyers), and crystallized as partially constructed forms, failing to achieve the originally proposed ends [

9]. These semi-built structures, suspended in time and space, have progressively degraded, constituting nowadays new forms of non-historical ruins or modern ruins created by the accelerated creative destruction of financialized capitalism and being an important part of the urban landscape (

Figure 1).

Starting from an understanding of the city as a socio-techno-natural system, Gandy [

10] notes that these settlements are privileged places of socio-natural hybridizations, places of interpenetration of the technological with the biological, of the human with the non-human. Urban wastelands, according to Gandy, may question the organizational logic of modernity. Conceptualizing and understanding them as vibrant dimensions of urban life, points at a myriad of possibilities for cities. Far from being abandoned spaces without human use, these wastelands or

terrains vagues [

11] are often appropriated with various uses and by various actors, from residents in the vicinity, passers-by, and people from other places who seek fun, quietness, or adventure. This poses an ideological as well as a practical challenge for the utilitarian impetus of capitalist urbanization, as the “intrinsic worth” of the ostensibly useless is as much a political question as an aesthetic or scientific one [

10] (p. 1312). In this regard, Yoshida Kenkō’s words are significant, as he argues that “in everything, no matter what it may be, uniformity is undesirable. Leaving something incomplete makes it interesting, and gives one the feeling that there is room for growth” [

12] (p. 22–23). Despite the interest shown by many scholars in urban shrinkage during recent years [

3,

4,

5], there is a dearth of research on the appropriations, uses and micro geographies present at particular sites, which are at the core of living in shrinking cities. This paper argues that buildings or semi constructed buildings, are not only structures made of brick and mortar, but have particular histories and memories, which should be recovered and understood before engaging in future actions. Following Leatherbarrow’s [

13] argument, we must escape the ‘sovereignty of buildings’ and address their wider contexts, relationships and performances. Buildings’ genealogies are key parts of the city as they are. A detailed look of what is happening in unfinished projects, allows for a better understanding of the meaning of abandoned and ruined spaces, contributing to a clearer view of the contemporary city itself. As Barron [

14] (p. 2) argues,

terrains vagues are counter spaces which contain a fragmented shared history, sometimes conceptualized as subversive, as “everyday areas that expose the stratified or palimpsest nature of all places”.

This paper puts forward a methodology to study uses and appropriations of urban ruins and vacant lands based on systematic ethnographic observation and detailed field work. The methodology [

15] was proposed in the context of the NoVOID research project—Ruins and vacant lands in the Portuguese cities: exploring hidden life in urban derelicts and alternative planning proposals for the perforated city (2016–2019). The aim of NoVOID is to study and understand the meaning, the qualities and the potential that ruins and vacant lands may have on planning strategies for the perforated city. Its focus is on a sample of four Portuguese cities, which are representative of different shrinking urban contexts: Lisbon and Barreiro—a metropolitan center and a city of its industrial belt, and, in the northwest, Guimarães and Vizela—an old historical town and a town that has developed in the last decades in association with small and medium size industrial companies. Furthermore, this methodology is applied to a case study—an unfinished project in the city of Vizela—for which fieldwork was carried out during 2017 and 2018. In this sense, the paper seeks to explore the socio-cultural meanings of this ruinous construction, its social life and its material and symbolic transformation through the various human performances it supports.

2. Methodology—An Unfinished Project in Vizela

Kitchin et al. [

16] (p. 30) consider a

ghost estate to be “a development of ten of more houses where 50% of the properties are either vacant or under-construction”. As Kitchin, O’ Callaghan and Gleeson [

9] (p. 1070) put it, “the unfinished estates that litter the Irish landscape offer an example of «new ruins» created through twenty-first-century capitalism”. In the Portuguese context unfinished projects present various situations. Some only have infrastructure in place, such as electricity poles and boxes, sidewalks and street pavement, but do not have any constructions. They have been set aside for further development which can take place at any time. Obsolescence only occurs if the municipality reviews the development plan or if the developer requests a land use change. Other unfinished projects are partially built, but not inhabited, and others still are partially built but have some inhabited units.

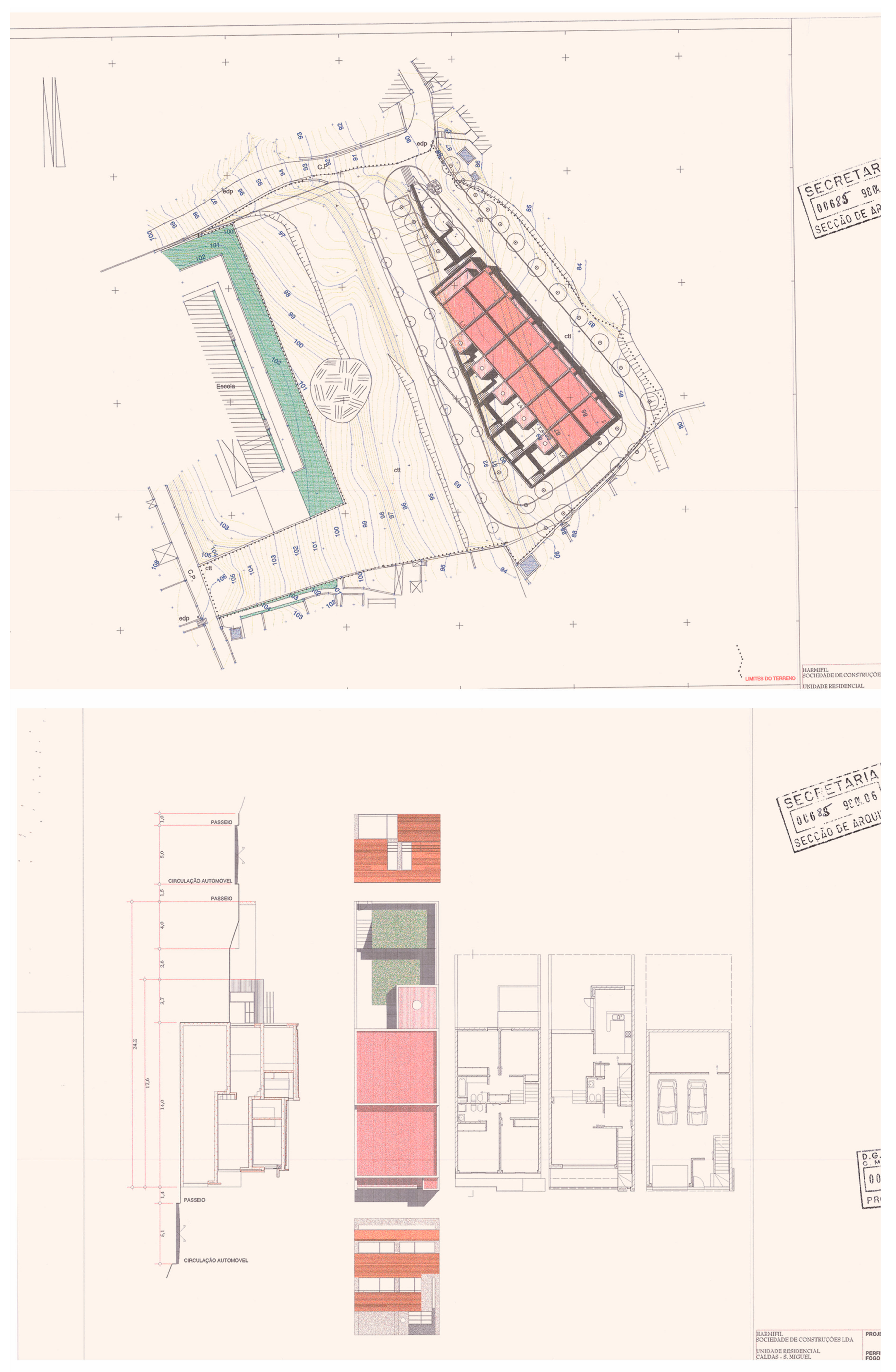

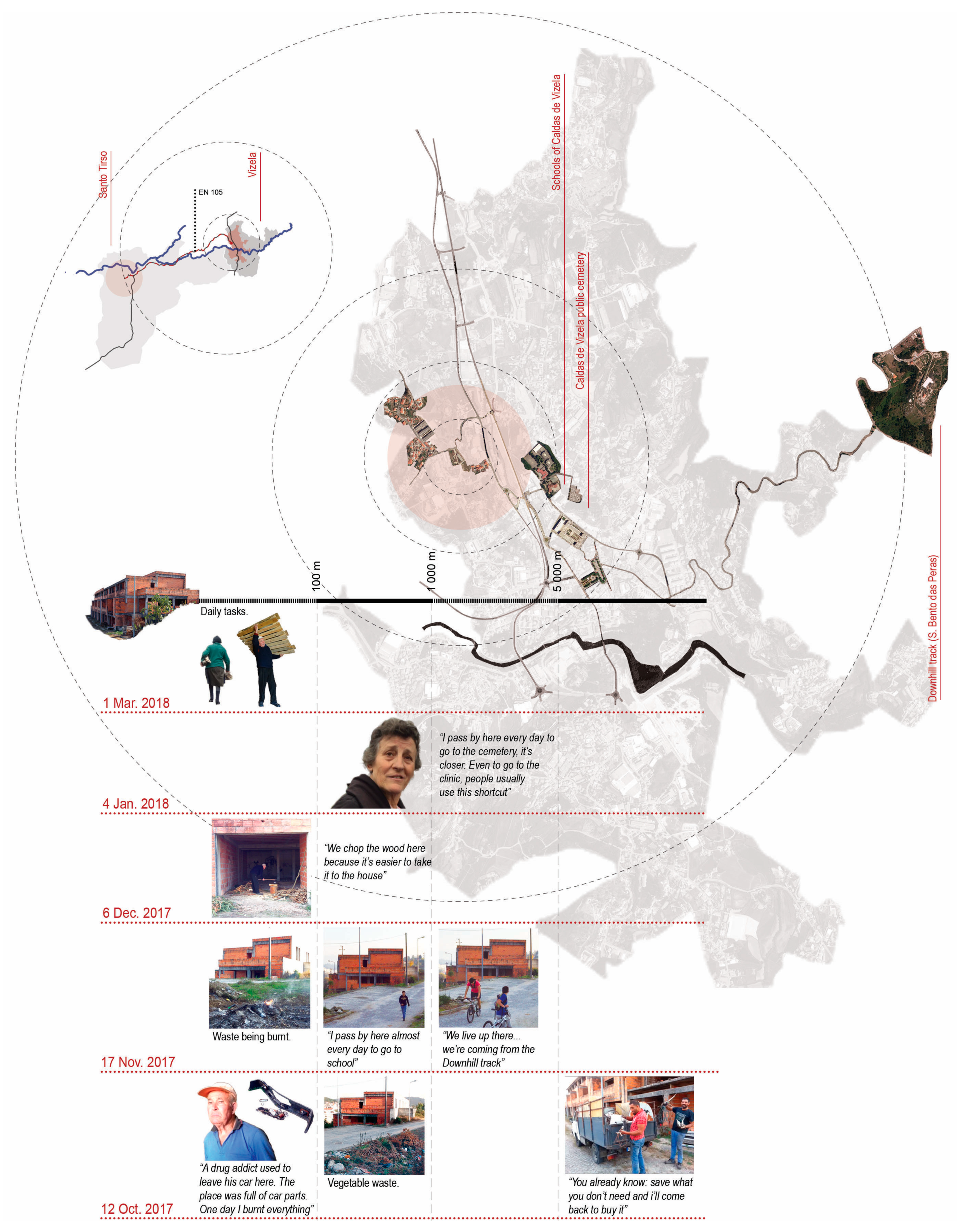

The case study here presented—Lage’s urban development—is one of these private urban development processes, located near the city center of Vizela which is a small city in the northwest of Portugal (

Figure 2). Within the context of the NoVOID research project, a survey to the city of Vizela indicates that the urban perimeter has 70 ruins, corresponding to 2.1 hectares, and 131 units of vacant land, which correspond to 91.2 hectares. Vizela is 6.8 km

2, and in the last census it had 10,633 inhabitants [

17]. It is an industrial city, although also an old thermal town. The city and its municipality is located in the Ave Valley, a region characterized by a diffused urbanization pattern [

18]. Urban limits are difficult to define, and the rural, forestry, industry, and the urban interpenetrate each other. It is often indicated as chaotic and unintelligible. As Travasso and Valle [

19] argue in relation to another city in the Ave Valley—Famalicão—“the urban structure of this region is not the product of any overall design, but the consequence of a process of successive addition of autonomous private urban development projects”. These imply the division of the land in plots to be subsequently built, and are characterized by private ownership, a uniform serial type of housing and a single planning process. They normally disregard the larger existing context in terms of built environment, and do not transform, add, improve or adapt it [

19]. In Vizela, just like in Famalicão or Guimarães and other cities in the region, urban developments of this kind have contributed to the perpetuation and prominence of a very dispersed and fragmented urban pattern.

Lage’s urban development is a building complex consisting of six townhouses, currently in a state of ruin, only with the basic structure, walls and rooftop (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4). Construction started in 2003 and was suspended around 2006, due to the bankruptcy of the building contractor. Once the building process stopped, this site has been the object, on a regular basis, of several and distinct appropriations by different kinds of users.

As Crang [

1] (p. 187) noted, cities are not solid things but becomings. Thus vacant land and unfinished projects are sites which have histories. They are not empty, blank spaces, or the negative image of cities, but lived and living places, full of opportunities. The methodological approach to study uses and appropriations in and of unfinished projects is divided in four parts: genealogy, catalogue, dynamics, and interactions.

‘Genealogy’ attempts to build or reconstruct a simple chronology of the site. It is achieved using two main types of research actions. The first one is using archival work (municipal, private, associative archives), recovering, whenever possible, visual materials which allow for a dynamic reading of the case study. It should include information such as relevant construction dates (start, abandonment, and so on), and may also include aerial photography, images from Google Earth, city plans, photographs, drawings and other project plans. The second one refers to informal conversations with former users of the site (factory workers for instance) and neighbors, and intends to recuperate information related to their memories and experiences of the site. For each case a variable perimeter around the site should be established that defines who the neighbors are.

‘Catalogue’ tries to construct a virtual collection of materials that includes photographic and video records made in loco, in order to build a digital archive for future use. This collection of materials should focus on objects which have apparently been moved after the abandonment of the construction phase. Evidence of squatting or other temporary uses—mattresses, blankets, food packages, syringes, bottles, packs of cigarettes, condoms—may help to capture the appropriations in place. The degradation of materials of the site should be registered as well, as broken glasses, forced doors, graffiti walls also suggest important uses.

‘Dynamics’ focuses on the experiences, rhythms and daily appropriations on site, and is registered through multiple visits during a long period of time. Ideally fieldwork should include seasonal visits and a weekly calendar comprising weekdays and weekends. When possible the survey of ‘dynamics’ should include daily and nocturnal visits. Within the NoVOID project, and taking into consideration financial and human resources, we established a minimum of 10 visits to each of the sites. Each visit should last at least 30 min.

‘Interactions’—the last part of the methodology—refers to the attempt to capture some of the social interfaces on site, through a variety of methodologies that range from informal conversations, interviews and focus groups with users. The principal idea is to establish the multiple relationships that people have with these sites and the feelings and emotions they attached to them: from fear of or indifference towards abandoned spaces, repulsive feelings related to degradation, to happiness resulting from quiet and tranquil spaces. It may include people who walk their dogs on vacant land, people who make detours not to cross degraded spaces, or children playing and exploring through rubble.

Concerning the Lage’s urban development, the methodological approach resulted on a total of 742 photographs and 1 h, 45 min, and 23 s of video recording, which includes informal conversations with 16 local actors, from which 7 are users of the site and 9 are people from the neighborhood. This survey was based on 18 visits to the site, 12 visits during weekdays and 6 during weekends, between June 2017 and April 2018.

3. Results

Because the collected materials had a strong visual propensity, the data was analyzed thought four main processes of graphic representation—Mapping, Translating, Flattening, and Spatializing—in order to understand the complex nuances of the human appropriations on a temporal and spatial dimension.

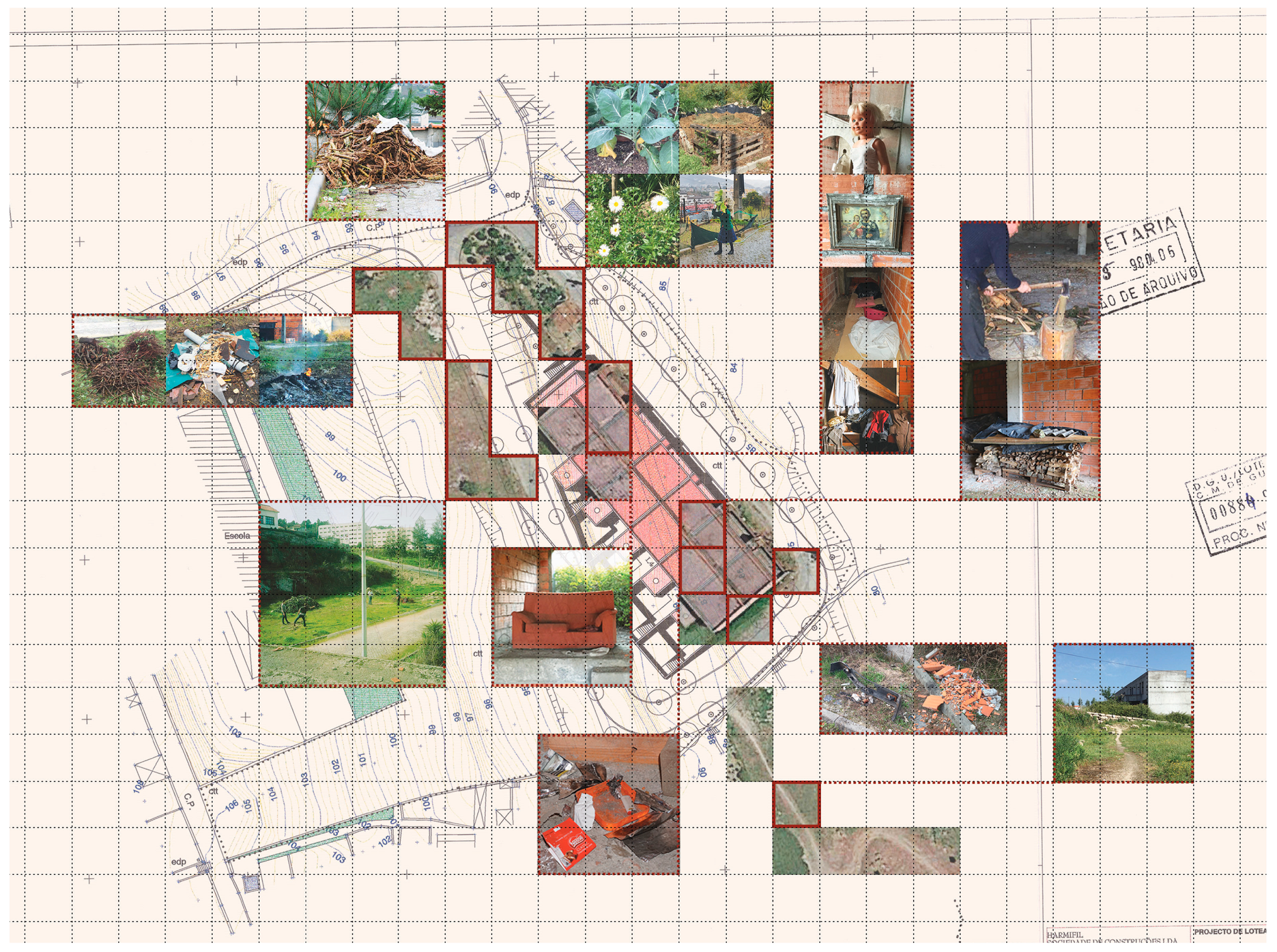

Mapping (

Figure 5) began by identifying and locating traces of human appropriations, through objects, materials or alterations found on site. This process consisted of an ‘archaeological’ survey, represented by overlapping to the initial and supposed building plan (1995), a virtual grid that selectively unveils the analyzed area (through aerial photography), complemented with in situ geotagged photographs. It was possible to verify that the greatest amount of traces were found on two opposite parts of the building, specifically, in the first and the last townhouses of the complex, at the north and south respectively. Among the traces found, there were several food packages, glass bottles, cigarette packs, burned aluminum foils, piles of wood, old furniture, construction materials, a painting hung on the wall, an old doll, and various junk. Also, on close vacant areas around the building, it was possible to find old car parts, vegetable and burnt waste, a small production area with some fruit trees and vegetables, a garden, and traces of an informal path marked on the ground.

While

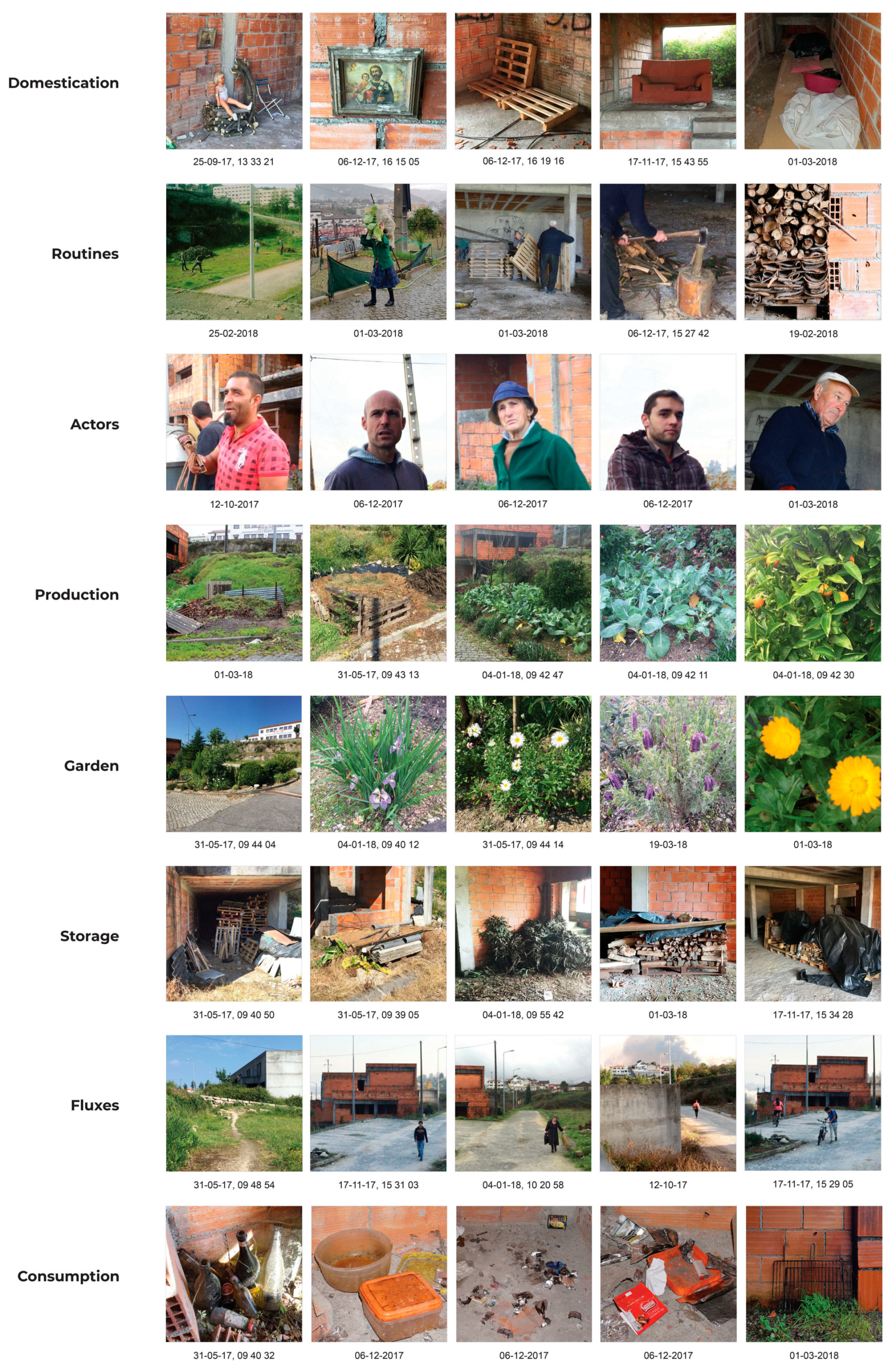

Mapping allowed to locate the traces found and to understand their spatial distribution,

Translating (

Figure 6) allowed the decoding and understanding of them. The observations made in situ resulted on a collection of photographs and video recordings organized chronologically (by date and time) on a Field Notebook. This fragments collection was subjected to a process of selection, regrouping and reordering, on a completely uncommitted relation with its specific spatial and temporal circumstance. The dissociation of these two moments—the collecting at first, and the selection, regrouping and reordering next—provided a re-reading of the findings and helped building an imaginary of the hidden performances involving this building. By detecting visual affinities between the images, the reorganizing of these collected fragments resulted on a new composition that helped creating narratives about the unknown life of these spaces, listing the main appropriation themes it supports.

It was possible to recognize some of the activities taking place but also to understand some of its users and rhythms. For example, one of the main actors of these appropriations, mapped on the north spaces of the building, is Mr. Bento, an 84-year-old man who lives across the street. Mr. Bento and his family (wife, daughter and son) use the ground floor of the building as storage (for piles of wood, vegetable waste, old furniture, construction materials, and various junk) and as a place where they perform routine domestic tasks (like wood chopping or barbecues). One of the spaces has even been personalized by Mr. Bento with a small painting hung on the wall, a chair, and an old doll that was laying around from when his daughter was young. The unbuilt plot area is used by Mr. Bento’s wife, Mrs. Elvira, as a garden and a production site, with a small composting structure, fruit trees and vegetables. Mr. Bento believes in his right to use the land, because he is the only one who does the effort to cultivate it: “everybody depends of the land, but no one wants to work it”. Mrs. Elvira, says that “we started by planting some flowers and bushes and they grew stronger”. After that, “we have cleaned some more, and started planting vegetables and beans”. However, there is a conscience of an alienable right on the land, because “this area belongs to the houses” and “if a buyer shows up, we give it back, and they already know if the soil is good to be cultivated or not”.

On the opposite south part of the building, the site has become a gathering place for alcohol and/or drug consumption, graffitiing, and destruction for some kind of fun. This “spot”, as it was nicknamed with spray on the walls by its users (some local young people), is located on the second floor, and has been personalized as well with an old couch and furniture made up of wooden pallets.

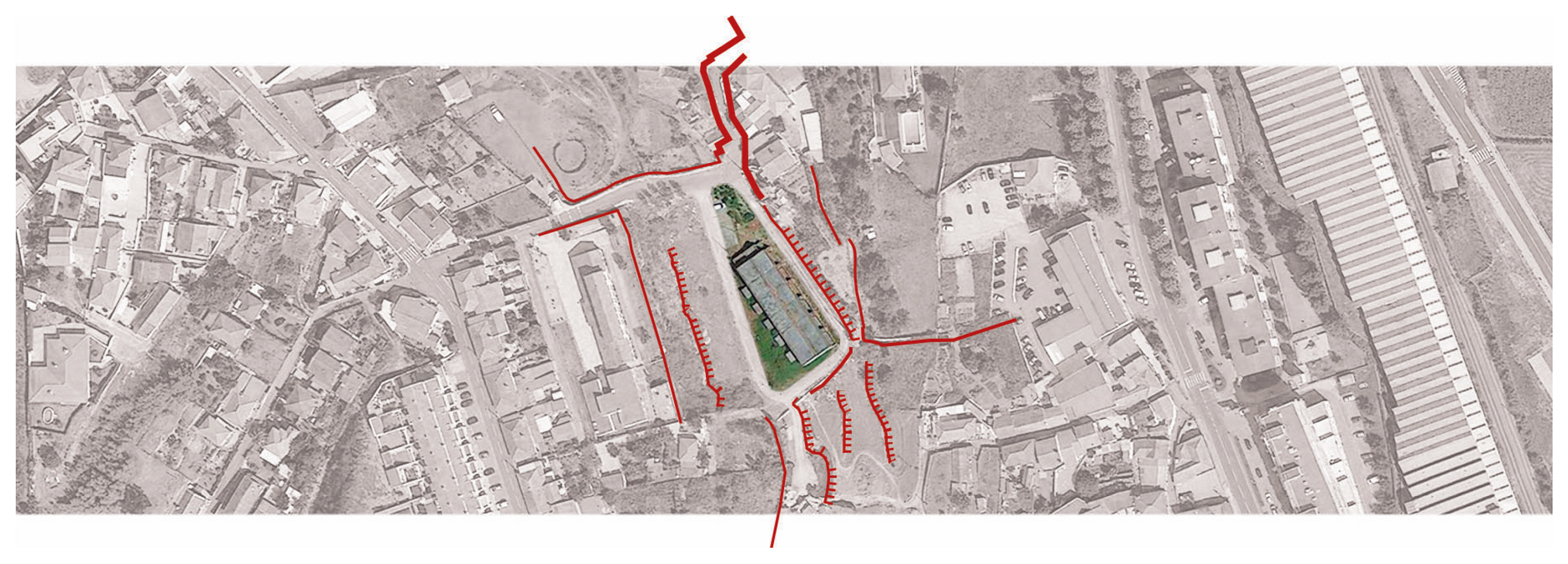

In order to understand a wider spatial and temporal context, a

Flattening analysis was also performed through the overlapping of different cartography (

Figure 7). On the 1948 map, Lage’s future area already shows some small basic constructions and a network of unpaved paths. These link the site to the National Road 106, a structural urban element that connects Vizela to the nearest city, Guimarães. Excluding Lage’s urban development (construction began on 2003), this structural urban system, remained almost unaltered until today (2016), revealing the long-term soil occupation. This stratification is evident when looking at the diversified road profiles connecting the area.

As many of these urban developments, Lage’s emerges with significant autonomy towards its preexisting context, spatially defined by small stone walls and land slopes (

Figure 8). As expressed in the project’s descriptive document, “it was intended a configuration that introduces the building on the landscape as an organizing element that compensates the dispersion and disorganization characterizing the area” [

20].

Once identified all the appropriations taking place in Lage’s urban development, the process of

Spatializing allowed to unveil a complex spatial system of hidden relations between this contemporary ruin and a larger territorial context (

Figure 9). Besides the appropriations by Mr. Bento and his family, just across the street, there are regular pedestrian flows around the ruin by people living on a residential area (at northwest) and seeking a shortcut to the town center, the cemetery, the local school and other important public areas (at southeast). Kids cycling to a downhill track, 5 km away, also use the area. But it was possible to establish some more far urban relations as well, for example, between people working with metal scrap who are located in the Santo Tirso city, about 20 km away, that regularly visit Lage’s development for materials gathered by Mr. Bento.

4. Discussion

The appropriations of urban ruins and vacant lands immediately raise questions over socially accepted behavior. One alternative way of looking at the diversity of uses occurring in these places, is to avoid seeing them indifferently as transgressive negative appropriations, but to analyze their potential contributions towards city life.

In the Lage’s urban development it was possible to identify two main types of appropriations, ranging from the domestic uses, performed by Mr. Bento and his family, to the more subversive uses, by some local young people. Although these behaviors may seem very distinct, there is a relation between these actors. Sometimes, wood stored by Mr. Bento is stolen and brought up to the south spaces of the building, to improvise some basic furniture. At the same time, Mr. Bento’s wife, Mrs. Elvira, reported that there were, at one time, some rocks thrown at her, from that part of the building, resulting on her confronting the aggressors. After that, there were no more reports of this kind. This analysis, along with the timing these happenings occur (the domestic uses during daylight and the more subversive uses usually after midnight), suggests that the more domestic actors take on a discouraging role for the more subversive uses, commonly seen as negative, and avoid, for instance, the emergence of problematic areas in the city, drug or crime related. At the same time, and slightly paradoxically, by supporting deviant behaviors conventionally not tolerated in the formal ordered city, these sites can emerge as spaces of freedom. Because these behaviors are part of human nature, this may nurture and reinforce the legitimacy and need for their existence.

In line with this, Mr. Bento believes on the idea that the site’s current state of abandonment gives him, or anyone else, the right to use it in the “meantime”, despite being a private building. He convincingly states, that “if anyone else [close neighbors] wants to put things here, they can”, on the condition that “if one day they [the owners] need the space, we take everything out”. This posture reveals an awareness of property boundaries mixed, at the same time, with a feeling of a non-transgressive behavior that overcomes a conventional dichotomy between the usage rights of the public and private domain.

The physical and visual continuity between the building and its immediate surroundings may help to understand some of the appropriations taking place, particularly, the occupation of the unbuilt area of the plot with a garden and a production site. Once the building process stopped, a plot context of a rural nature, with very crossable limits, proved to be stronger and more dominant. This reveals the permanence of a use value of the soil (former area of production of the Villa Lage) despite the new residential program for the site and its private domain.

Concerning a wider urban context, the unveiled territorial relations put Lage’s urban development in the center of a complex socio-spatial system, expressing different activities, scales of mobility, rhythms, meanings, etc. These links, being just one small part of what makes urban life, may give some hints for strategical and key interventions, aimed at low cost solutions capable of stimulating new collective dynamics.

5. Conclusions

At present—late 2018—banks are now ‘back in business’ (Troika’s departed in May 2014), property prices are increasing and some of these ‘suspended projects’ are being rescued to the orbit of property development and financial speculation. Still others remain idle, opening breaches and indeterminacy, allowing for the emergence of socio-natural hybridizations.

This paper highlights a political challenge about the right to use vacant spaces in the contemporary city, which implies rethinking the rigidity of public and private boundaries. It is clear that the boundaries of these sites play a central role in the mediation of their uses and appropriations. They can range from built boundaries on consolidated urban fabric, boundaries defined by small walls or fences, to plots only with basic infrastructure and no erected boundaries. As seen in Lage’s case, fragile boundaries characterized by physical and visual continuity made it possible to respond on a close urban scale to programmatic domestic needs. But besides addressing the material boundaries as key elements of the transformation strategies for these sites, its integration in the contemporary city planning may be possible by addressing other immaterial control mechanisms. For instance, because some actors show a caring attitude towards the building (as if it were their own) and have a positive effect concerning the site’s conservation, formalizing these appropriations by articulating ownership rights and user rights may be an appealing option towards an easier construction comeback.

However: formal uses and appropriations or hybrid forms of intervention were not identified in Lage’s development or, apart from a few exceptions, in all case studies of the NoVOID project. This is perhaps related to the fact that there is little tradition, notably in Portugal, in disciplines like architecture, landscape architecture or urban design, and in planning authorities, to engage in processes that diverge from form generation, aesthetics and productivity. Also, in an urban context where the inexistence of a strong social demand does not produce visible and significant squatting practices, this does not seem to be a pressing issue.