1. Introduction

The transformations brought about by the Industrial Revolution triggered the evolution of the conservative concern—from the isolated monument to historic areas—coinciding with what Françoise Choay called the conquest of the disciplinary status of the conservation of historical monuments [

1]. This was a process that was shaped during the first half of the 20th century, and ultimately consecrated in the 1960s, as a consequence of the restoration of numerous urban areas following the devastation caused by the two world wars.

From this period onwards, the milestones that were to establish the doctrine of cultural heritage in relation to the city, and the consequent task of preserving the values that make it worthy of that condition, began to occur. The notion of a protected urban landscape was established by the jump from the isolated monument to the historic area; although, it was already implicit in the concept of setting of a monument. An international definition of setting is included in the Xi’an Declaration on the Conservation of the Setting of Heritage Structures, Sites and Areas [

2].

The historic urban landscape has been defined by UNESCO as “the urban area understood as the result of a historic layering of cultural and natural values and attributes, extending beyond the notion of “historic centre” or “ensemble” to include the broader urban context and its geographical setting” [

3] (article 8).

The broader context “includes notably the site’s topography, geomorphology, hydrology and natural features, its built environment, both historic and contemporary, its infrastructures above and below ground, its open spaces and gardens, its land use patterns and spatial organization, perceptions and visual relationships, as well as all other elements of the urban structure. It also includes social and cultural practices and values, economic processes and the intangible dimensions of heritage as related to diversity and identity” [

3] (article 9).

Trade is among social and cultural practices and economic processes. The need for the supply and exchange of goods that occurs in every human agglomeration has motivated, throughout history and until now, the continued presence of commercial activity in the focal areas of urban social activity [

4].

The routes generated by the flow of goods and services have impacted upon the emergence, flourishing, and decay of numerous urban centres throughout history [

5,

6], while also allowing contact between cultures, beliefs, and different systems of organization [

7,

8,

9]. Therefore, commercial activity is an essential functional element both in the history of the city and in its present.

Since antiquity, commercial facilities have been located in the vicinity of palaces and temples [

10,

11,

12], next to the gates of cities, and near ports. These thematic facilities, sometimes made up of temporary structures, were complemented by shops installed on the ground floor of residential buildings, usually with direct access from the street. These facilities have been present in urban growth processes and, sometimes, they were determinant in these processes, as was the case during the 16th and 17th centuries, or since the middle of the 20th century [

13,

14,

15,

16].

The profound changes that have taken place since the 19th century—derived from the new economic model, technical development, the increase in urban population, and the transformations that took place within cities—would give increasing importance to commercial activity [

17].

This activity would experience permeability to aesthetic fashions like never before, thanks to the development of interior and exterior design, shop windows, and advertising [

17,

18]. In parallel, there appeared new architectural typologies for commercial use, such as passageways or department stores [

19,

20]. The functional hierarchy of commercial facilities that has determined their location since the mid-19th century would continue to develop to the present day [

21].

These tendencies that began in the 19th century would be accentuated in the 20th century, ultimately determining urban transformations [

22,

23]. In those tendencies, the importance of commercial activity would increase, placing it at the heart of the new models of urban growth that began to develop in the United States in the first half of the century [

24]. These models pursued the perfect commercial city and materialized as residential areas in the suburbs, whose centre of community life is the shopping centre [

25].

The appearance and development of the typology of the shopping centre—a symbol of the consumer society of the 20th century—and the role granted by urbanism to this entity, would set the rhythm between central urban trade and peripheral trade that would be a constant throughout the century [

22,

24].

The 20th century would end with a concept of the city where commercial leisure activities, along with recreational and cultural activities, played a leading role in urban life [

25].

In the elapsed years of the 21st century, there has been a global expansion of the peripheral commercial area typology, especially in Asia and the Middle East [

26], as well as in ex-communist European countries.

At the same time, in the United States, symptoms have been produced that we are in a post-mall era in sense of shopping centre understood as a centre of community life and a relevant institution in society [

27]. One of the most significant symptoms of this phenomenon is the conversion to new non-commercial uses of old malls. The First Baptist Church at the Mall opened since 2006 in Florida (USA) is a case in point [

28].

New types of shopping centres have also appeared, such as the strip shopping centre, strip mall, or affinity centre and villages. In parallel, the situation in city centres is marked by what has been configured as a new urban commerce [

29], with a mix of typologies where the old—with and without modifications—coexist with new types.

Therefore, the urban landscape is composed in a high percentage by elements, isolated or together, of spaces and buildings that are, or have been, destined to trade and exchange. The main objective of the present work is to analyse some commercial typologies that exist in historical urban areas and its relationship with the urban landscape and its heritage values.

Demonstrated from several areas of knowledge the essential role of trade in urban areas, both in the past and in the present, this work also analyses how monumental building typologies whose original function may have been commercial or not constitute essential elements of the current historical city. How the historic buildings and their uses that are part of the commercial urban landscape, create and modify it, but also preserve it as it acts as a cultural element of prestige and attraction of the consumer.

2. Line of Work and Methodology

This research is developed under a working line which is based on the relationship between the preservation of historic urban areas and their adaptation to the needs that contemporary society demands of them in order to continue living within them [

30,

31,

32,

33,

34]. In particular, we focus on urban commerce, as it is one of the elements that have received the least monographic attention relative to the primary focuses of preservation and the scientific knowledge of cultural heritage. There is a large amount of literature devoted to the management of commercial activity in urban areas, which in some cases looks at areas with heritage protection, but generally concentrates on the analysis of economic and management aspects [

29,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41], lacking a deep cultural heritage-oriented approach.

The research method used is based on the empirical study of the object of attention, from the perspective of the visual analysis of the urban landscape. The choice to identify and evaluate the results of the initiatives developed or under development from the visual analysis of the urban landscape is motivated by the specific point of view of the art historian. This is always based on the vision, analysis, and interpretation of the image, what it contains, and how it is perceived—a reading that is integral, allowing one to simultaneously analyze the physical and the functional, the tangible and the intangible.

Research is an integral part of a doctoral thesis entitled ‘Commerce and Cultural Heritage: Management strategies and actions carried out in historic urban areas’ [

42] which objective is to analyse the role of the commercial activity in historic urban areas in relation to the preservation of their heritage values. Entities, models and cities from five continents have been investigated, especially from the United States, Cuba, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, France, Belgium and Spain.

The present work includes different cases of study. The approximation to the historic development of urban commerce is based on United States and Western Europe experience. The results of the field work are based on four European cities: Madrid (Spain), Porto (Portugal), Norwich (UK) and Leiden (Netherlands). All of them have historic urban areas protected in which urban commerce play an important role. Madrid is the capital of Spain and has a population of around 3,222,000 [

43]; Porto is the second most important city in Portugal and its population is around 214,500 [

44]; Norwich has a population around 140,300 [

45] and is ‘one of the five fastest growing cities in the UK’ [

46] (p. 18); Leiden is one of the most important cities in South Holland province and has a population around 124,400 [

47].

The following section presents the analysis of the mentioned cases and the preliminary results extracted. The analysis is mainly focused on elements that allow identifying some of the trends and transformations that commercial activity is experiencing in urban centres. Firstly, commercial formats that are being developed in order to move commercial offer from the peripheries to urban centres. Secondly, new commercial formats that establish a dialogue with the heritage values of the urban landscape, using them as a resource of attraction and differentiation for increasing their clientele.

3. Analysis and Preliminary Results

The traditional commercial areas of urban centres are considered commercial laboratories, especially in large cities, where they try out and filter tendencies that later expand into other small cities and towns [

29].

The analysis of the urban landscape shows that, at present, there is a convergent tendency of commercial typologies that includes the adaptation to urban centres of formats typical of the peripheries, such as supermarkets or the urban stores of companies whose premises were formally only installed in peripheral commercial areas (

Figure 1). Due to this, companies have developed formats in which the concept is adapted to the requirements or limitations of the urban regulations in protected areas and the characteristics of existing commercial premises. This process has contributed to the disappearance of local supermarkets, which cannot compete on prices with those belonging to large groups, which can now also operate as franchises.

At present, we no longer only speak of a traditional supply trade for urban commerce, but also associate it with innovative business profiles that are going to develop their activities in permanent and non-permanent physical spaces, constituting themselves as essential actors in the current urban landscape of historical urban centres.

The rise of electronic commerce, or the simple possibility of purchasing from a computer, has forced retail outlets to change strategies in their stores. They must now make it an experience to visit their stores so that customers will want to go to them [

49].

We speak of an attraction trade whose clientele transcends the residents of the neighbourhood, its extent depending, more or less, on the function that the city represents within the territory, the attraction capacity of the store owners, and the character and state of conservation of the cultural heritage of the urban centre.

A formula that is gaining prominence is that of the shared space, where several business people share the expenses of a single place in which each one has an individualized store space. This is the version of commercial activity known as the co-working premises, a concept associated with offices and professional activities that providing services rather than selling products.

In the search for space optimization and cost reduction, multifunction spaces house different uses or services depending on the hour or day. There are also spaces that house different functions simultaneously, usually selling clothing and decoration associated with cafeterias, to which can be added other functions, such as hairdressing, massage, or sale of art works.

In the ephemeral urban landscape produced by commercial exchange activity, a new format has appeared: pop-up stores/retail/shops. These are installations that appear and disappear, directed not at sales, but to the promotion and branding of the company and/or of certain products. They seek to convey a goal that is not simply to sell a product, but to sell a concept and provide an exclusive experience, thereby attracting the customer to the brand by directing them to both its online store and its digital communication channels.

Another ephemeral manifestation of creation or intervention in the landscape is the punctuated event format similar to a market, but spread or developed over a specific urban area. These actions provide the possibility of buying and selling products to complete cultural programs generated around commercial activity, which is always the main reason for the existence of these events. Sometimes only shops installed in physical stores in the area can participate, which display their products on the street, or the events can be open to other companies to install pop-ups or have temporary displays.

The businesses that represent new urban commerce coexist with other older businesses, these, in many cases, tending to disappear for different reasons: disappearance of shop owners without generational relief, exhaustion of the concept of a particular trade, changes in the commercial dynamics of the street or area where the store is located, regulatory changes, or the disappearance of its clientele. There are also cases in which historic stores are kept alive and accommodate the demands of the current consumer without changing their focus. Another traditional method that is maintained is that of the craftsperson who has a shop-workshop where they make and sell their products.

A historical commercial typology that is maintained is that of the market, whether it be a stable market housed in a building (

Figure 2) or an installation erected for that purpose (

Figure 3a,b), or in a temporary format (usually of a weekly nature) (

Figure 4a,b). However, a substantial number of the markets housed in buildings have being restructured in order to revitalize them and also update its offer (

Figure 5a–c) or turn them into a tourist attraction (

Figure 5d).

Most of the new formats of urban commerce respond to the concept of a city that has been established since the end of the 20th century, where the festive, the immaterial, the playful, and the cultural, and their combinations with commercial leisure, take on greater prominence [

25].

Added to this are the implications of the translation of business management techniques to urban management, from which city marketing has emerged [

50]. Cities develop value creation strategies in which cultural heritage emerges as a differentiation resource that is linked to its ability to attract visitors [

51], strongly associated with cultural tourism, but also with the attraction of other economic activities, such as commercial activities.

This power to attract visitors exerted by heritage is linked with concepts that are going to become hegemonic in the 21st century: the emotional and the sensory [

52], which are characterizing present and future trends of marketing and branding; and also experience, which guides the tourism and luxury industries, “two of the most powerful engines of the planetary economy” [

53] (p. 193).

The clearest case of using the historic urban landscape as a scenario that strengthens and multiplies the brand values that companies want to transmit is found in the ephemeral formats we have discussed. For example, this is the case of the installation of a pop-up of the company Custo Barcelona in one of the buildings that is part of the World Heritage Works of Antoni Gaudí [

54,

55,

56].

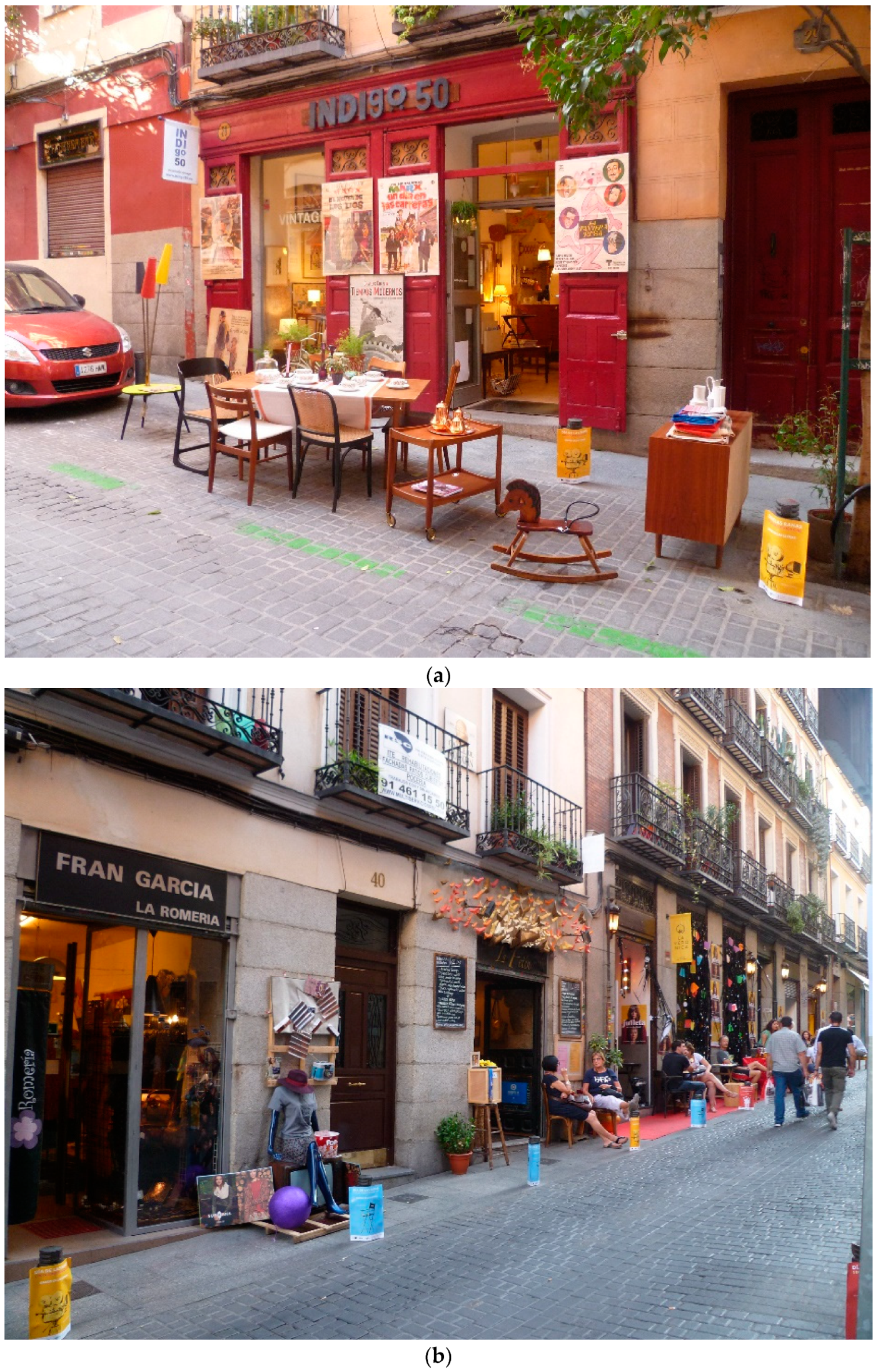

Frequently, these ephemeral formats are promoted and organized by groups of traders who are located in the same urban area (e.g., a neighbourhood, group of streets, or an individual street) with the aim of attracting potential customers of their businesses. This is the case of the so-called Market of the Frogs (

Figure 6a,b), organized on the first Saturday of each month by the Association of Merchants of the Barrio de Las Letras in the city of Madrid (Spain).

These uses of heritage value take place in commercial premises. Mainly in the case of the exteriors, the maintenance of the defining elements of the premises’ facades may be motivated by the requirements of heritage protection regulations. These usually contain guidelines regarding materials, designs, colours, and decorative elements. However, maintenance can also occur, as is usual for the case of the interiors of the premises; a new company recovers historical elements associated with its trade for the design of its premises by maintaining existing elements, or deciding not to part with elements associated with its own activity throughout its history.

These cases are also significant for the recognition of heritage values related to the commercial activity, through the elements associated with it, by its direct participants. In addition to the provision of value, store owners contribute to the preservation process of cultural heritage through the identification of the heritage elements, the realization of intervention projects, and the diffusion of these and of the knowledge related to the commercial activity itself.

4. Discussion, Conclusions and Future Works

The previous analysis allows extracting relevant information about commercial typologies in historical urban areas. It is necessary to remark that trade is a living activity, as are the people who give it meaning, who generate the flow of goods, ideas, and of people who have to pass through the inherited urban fabric. The commercial urban landscape of historic urban areas is a mixture of formats, sizes, and proposals, where hundred-year-old establishments coexist with newly created ones, stores anchored in the past with the avant-garde, stable points of sale with the ephemeral, local shops to supply residents from the neighbourhood with other attractions for clientele that originate from the same city or visitors from another country. All this is in constant movement and susceptible to change.

Given its nature as a private economic activity, trade changes, evolves, and transforms according to the needs of the market and society, or it disappears. This makes it, therefore, difficult to approach from the point of view of protection of cultural heritage, both of its physical and immaterial elements.

Commerce is also a part of the heritage value of protected cities, as it is one of the defining functions of an urban area. From the point of view of the preservation of urban protected areas, it is necessary to unite with this the preservation of the commercial function itself, both for its intrinsic values and for its role in the balance of the urban ecosystem, especially in relation to the establishment of the resident population.

In this sense, it can be said that the substitution of one trade for another is good news because the premises retains a commercial function despite the closure of the previous business. Detailed analyses of the urban landscape frequently reveal periodic changes in terms of products and brands, but globally the use of the premises and the flow of people they generate are maintained.

The new formats of local supermarkets are also helping to recover the service of supplying necessities that has been badly damaged by the expansion of land use in the suburbs and the disappearance of food stores in most central areas. These types of establishments also offer extra services, such as home delivery, for which they have vehicles adapted to the historical layout of the city. It is a clear example of how trade is essential to maintaining the residential character of these areas.

Trade is part of the urban landscape, creating it and modifying it, but also preserving it. At present, the predominant tendencies in promotion and sales strategies look to elements that are contained in cultural heritage, in general, and in historical urban landscapes, in particular. This favours the idea that, in the difficult equation between preservation and destruction, urban commerce is an ally of preservation, despite the complex historical relationship between merchants and administrations in their management of protected areas.

As is already commented at the introduction of this work, there is a close relationship between the urban phenomenon and commercial activity throughout history. Therefore, is possible to affirm that trade is an essential element of the city and its urban landscape. For this reason, the historical research of urban commercial activity provides essential information on the configuration of cities, in general, and of protected urban areas, in particular. It also provides information to understand at present the relationship between commercial activity and urban space.

The transcendence of commercial activity in the historical evolution of the city is reflected in the presence of elements linked to it in the cultural heritage currently existing in urban settlements. The relationship of feedback between stores and markets and the influx of people is manifested throughout the history of the city, and is reflected both in the names of many streets and squares, and in the fact that various commercial uses are currently maintained in certain spaces that have been hosting these activities for decades, even centuries.

It is common that among the elements of urban cultural heritage preserved in many cities today, a direct relationship with their commercial past can be established. In some cases, buildings or other architectural, sculptural, or pictorial elements are preserved specifically because they are associated with the commercial boom in which they appeared. In other cases, it is because the urban framework preserves developments or reforms that have occurred as a result of the impact of commercial activity. There are also cases in which manifestations of intangible heritage are linked to commercial events or the production of certain goods and services that have fuelled an economic boom associated with their trade.

This work is part of a larger project and presents initial analysis and results which are supported by empirical evidences. As future work, an extensive analysis of the role of commercial activity in historic urban areas in relation to the preservation of their heritage values will soon be published in book format.