1. Introduction

The rapid growth of digital services, cloud infrastructures, and high-performance computing has increased data center energy use, raising concerns about ICT systems’ environmental impact. Recent research reveals that ICT’s climate impact has been underestimated, emphasizing the necessity for proper sustainability evaluations and responsible infrastructure development [

1]. Virtualization technologies can consolidate workloads and reduce hardware consumption, but their energy performance depends on the operating system and hypervisor architecture [

2]. Server virtualization optimizes resource usage and reduces idle capacity in data centers, improving energy efficiency [

3,

4]. Virtualization selection is still a difficult multi-dimensional challenge, despite hypervisor research advances, including green virtualization strategy optimization [

5]. Modern virtualization platforms are characterized by hypervisor architectures such as Xen [

6], performance diagnoses in virtual machine environments [

7], and live migration mechanisms [

8]. Recent research stresses virtualization’s power-saving potential in sustainable computing [

9]. Further evaluations of green computing emphasize the importance of virtualization in enabling energy-efficient and environmentally friendly digital ecosystems [

10]. Global sustainability frameworks such as the SDGs recognize the importance of ICT systems in increasing climate resilience, sustainable industrial innovation, and responsible consumption and production (SDG 9, 12, 13) [

11,

12]. Sustainable virtualization assessment evaluates virtualization technologies’ ability to support energy-efficient resource utilization, reduced operational energy consumption and emissions, hardware lifespan extension through improved consolidation, and long-term operational sustainability. Beyond technical performance, sustainable virtualization stresses software quality attributes, including performance efficiency, stability, security, maintainability, and portability, which affect IT infrastructure lifecycle sustainability. Sustainable virtualization supports SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure) through efficient digital infrastructure, SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production) through resource optimization, and SDG 13 (Climate Action) through data center energy savings and emission reduction. This definition underpins the proposed decision-support system and motivates ISO/IEC 25010–based evaluation criteria.

Choosing a sustainable virtualization platform is still difficult due to opposing requirements such as performance, interoperability, maintainability, security, power consumption, and usability. The ISO/IEC 25010 quality model evaluates software-intensive systems for functional suitability, dependability, performance efficiency, compatibility, usability, security, maintainability, and portability [

13]. Most benchmarking and assessment studies focus on quantitative performance indicators such as throughput, CPU cycles, memory bandwidth, and latency [

6,

7,

8,

14], while real-world decision-making demands qualitative and software-quality qualities. Despite its importance, this approach is rarely used in sustainability-oriented virtualization technology assessments, resulting in evaluations that neglect key elements affecting long-term operational and environmental performance.

Human expert judgment is imperfect, uncertain, and naturally articulated in linguistic terms, complicating virtualization sustainability assessment. Fuzzy multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) has been frequently used in IT service or application selection, cloud sustainability assessment, and energy optimization studies to address this difficulty [

15,

16,

17,

18]. Soft computing technologies such as fuzzy logic, rough sets, and machine learning may handle uncertainty and complexity in virtualized and cloud environments [

17]. Based on this basis, hybrid fuzzy MCDM techniques such as the fuzzy AHP (FAHP) have been used in mobile learning and educational technology assessment [

18].

The FAHP converts language expert judgments into fuzzy numerical scales, minimizing inconsistency and better representing expert preference structures [

19]. However, purely fuzzy algorithms may yield enormous or redundant attribute sets, restricting interpretability. Pawlak [

20,

21] presented rough set theory (RST), which provides a supplementary mechanism for attribute reduction, dependency analysis, and rule extraction without probability distributions or membership functions. By eliminating extraneous features and creating short rule-based explanations, hybrid fuzzy–rough approaches have enhanced sustainability evaluations in smart energy management [

22], environmental systems [

23], and big data [

24].

Hybrid intelligent approaches have great potential, but the literature is lacking. Most virtualization studies measure performance, cost, or energy consumption [

2,

3,

4,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

25,

26,

27], but few include ISO/IEC 25010 quality parameters including dependability, usability, maintainability, and security [

13].

Additionally, while fuzzy MCDM techniques have been applied widely in ICT and sustainability domains [

15,

16,

17,

18], no prior study integrates FAHP weighting, RST attribute reduction, and TOPSIS ranking into a unified evaluation model for virtualization sustainability. Existing models also remain largely theoretical, with limited translation into practitioner-oriented tools; thus, IT managers lack accessible mechanisms for applying advanced multi-criteria techniques in real-world virtualization decisions. Furthermore, few studies explicitly situate virtualization evaluation within broader sustainability agendas such as SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation & Infrastructure), SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption & Production), and SDG 13 (Climate Action) [

11,

12], limiting the strategic alignment of technical decisions with global sustainability priorities.

To address these gaps, the current approach proposes a hybrid fuzzy–rough MCDM framework that integrates the Fuzzy Analytic Hierarchy Process (FAHP) for modeling uncertain expert judgments and deriving robust sustainability-oriented weights [

15,

16,

17,

18], rough set theory (RST) for attribute dependency analysis, removal of redundant criteria, and extraction of interpretable decision rules [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24], and the TOPSIS for ideal-solution ranking and sustainability prioritization of virtualization alternatives [

28]. This study provides a web-based decision-support dashboard that operationalizes the whole hybrid architecture, enabling automated fuzzy weighing, RST rule extraction, and interactive sustainability ranking display to improve real-world applicability. The incorporation of rough set theory (RST) in this work is not due to the computationally extensive number of evaluation criteria, but rather to address a conceptual challenge that is frequently encountered in sustainability-oriented multi-criteria decision-making: criterion redundancy and limited discriminative power among interrelated quality attributes. There is often partial overlap among the criteria derived from software quality and sustainability frameworks, such as ISO/IEC 25010. This can obfuscate the criteria that are truly decisive in distinguishing alternatives. For example, performance efficiency, adaptability, and perceived value.

Therefore, RST is implemented as a mechanism for knowledge reduction and interpretability, which facilitates the identification of minimal criterion subsets that maintain the same classification capability as the complete set. This enhances transparency and managerial usability by enabling decision-makers to more effectively understand which criteria (or combinations of criteria) are essential for differentiation. It is crucial to note that RST is employed as a complementary analytical layer, rather than as a substitute for classical MCDM aggregation.

Hybrid fuzzy–rough multi-criteria decision-making systems have been developed to address uncertainty and indiscernibility by integrating fuzzy sets with rough set theory, especially for attribute reduction and interpretability [

21,

29]. Recent domain-specific research includes employing a fuzzy–rough framework for stakeholder-oriented sustainability evaluation in agritourism [

30], and another study introduces a bipolar fuzzy rough extension of the VIKOR technique, emphasizing preference modeling and compromise ranking [

31]. Although these research illustrate the theoretical adaptability of fuzzy–rough hybridization, they are predominantly survey-based or too theoretical, failing to tackle software quality-related choice issues or explicit criterion dependency and redundancy analysis. Conversely, numerous fuzzy–rough MCDM investigations inside engineering and information systems highlight the utilization of rough sets for analyzing attribute dependency and identifying reducts, hence facilitating transparent and succinct decision models [

32,

33]. The proposed FAHP–RST–TOPSIS methodology builds upon this research, aiming for an ISO/IEC 25010-compliant sustainable assessment of virtualization technologies, utilizing RST to improve interpretability and robustness before ranking.

This study uses hybrid soft computing approaches and a practical decision-support application to create a rigorous and holistic evaluation framework for sustainable virtualization platforms, a transparent and interpretable fuzzy and rough-set logic decision-making process, a practitioner-friendly tool that simplifies complex MCDM methods, and a sustainability-aligned mechanism for energy-efficient, ISO/IEC 25010-compliant virtualization decisions. It helps enterprises choose energy-efficient, reliable, and environmentally friendly virtualization solutions with analytical rigor and practical applicability. By integrating the FAHP for uncertainty modeling, RST for criterion reduction, and the TOPSIS for sustainability ranking within an ISO/IEC 25010 and SDG-aligned framework, this study directly addresses the lack of holistic, interpretable, and practitioner-oriented sustainability evaluation models for virtualization technologies identified in the existing literature.

1.1. Motivation for This Study

Most benchmarking and assessment studies of virtualization technologies focus primarily on quantitative performance indicators such as throughput, CPU cycles, memory bandwidth, and latency [

2,

3,

4,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

14]. While these metrics are important, real-world virtualization decisions increasingly require the consideration of qualitative and software-quality attributes, particularly in sustainability-oriented contexts. Evaluations that rely solely on technical performance often neglect factors affecting long-term operational efficiency, environmental impact, reliability, and adaptability, which are critical for sustainable digital infrastructure [

11,

12,

13].

Virtualization sustainability assessment is further complicated by the nature of human expert judgment, which is inherently uncertain and commonly expressed using linguistic terms. To address this challenge, fuzzy multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) methods have been widely applied in IT service selection, cloud sustainability assessment, and energy optimization studies [

15,

16,

17,

18]. Fuzzy approaches enable the transformation of linguistic judgments into numerical representations, improving consistency and the modeling of uncertainty in expert-driven evaluations [

19]. However, sustainability-related quality criteria—particularly those derived from standardized frameworks such as ISO/IEC 25010—often exhibit conceptual overlap and interdependence. In such cases, direct aggregation of weighted criteria may reduce interpretability and obscure which attributes are truly decisive in differentiating alternatives. This motivates the need for an analytical mechanism that not only supports ranking but also enhances transparency and interpretability by identifying essential criteria and dependency relationships among them.

1.2. Research Gap and Contribution

Fuzzy MCDM is widely used in ICT and sustainability [

15,

16,

17,

18], though there remain gaps in the literature. First, most virtualization evaluation studies focus on performance, cost, or energy consumption, but few include ISO/IEC 25010 software quality factors such as dependability, usability, maintainability, and security [

13]. Therefore, sustainability assessments are typically incomplete and not connected with long-term quality and resilience. Second, hybrid intelligent approaches that combine fuzzy logic with other soft-computing techniques have shown success in smart energy management, environmental systems, and big data analytics [

22,

23,

24], but their use in virtualization sustainability assessment is limited. Rough set theory (RST) has not been properly studied as a complementary analytical technique for attribute dependency analysis, redundancy reduction, and rule extraction [

20,

21]. Third, current models are mostly theoretical and lack actual deployment assistance. Therefore, decision-makers lack accessible, practitioner-oriented tools to turn advanced MCDM techniques into sustainable insights. Few studies clearly link virtualization evaluation to the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 9, 12, and 13 [

11,

12]. This paper presents a hybrid FAHP–RST–TOPSIS methodology for evaluating sustainable virtualization technologies to address these shortcomings. FAHP models expert judgment uncertainty and derives sustainability-oriented criterion weights [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19], RST analyzes attribute dependencies and improves interpretability through criterion reduction [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24], and the TOPSIS ranks alternatives based on ideal-solution proximity [

28]. To operationalize the framework, a web-based decision-support dashboard is created, making it more useful in real-world virtualized decision-making.

2. Materials and Methods

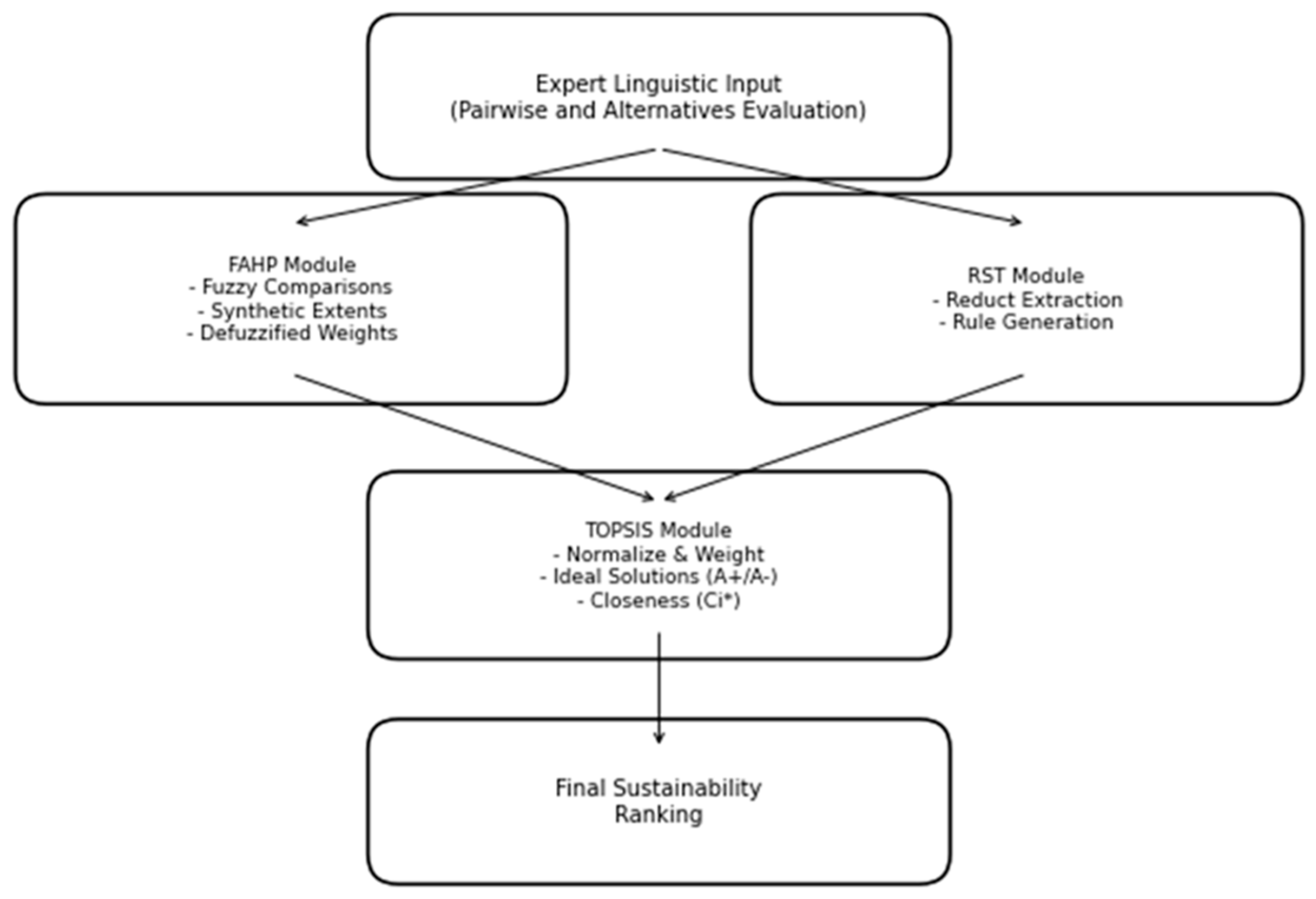

The current work employs a hybrid FAHP–RST–TOPSIS framework integrating the Fuzzy Analytic Hierarchy Process (FAHP), rough set theory (RST), and TOPSIS to evaluate the sustainability performance of server virtualization technologies in alignment with ISO/IEC 25010 and SDGs 9, 12, and 13. The three methods are systematically connected to ensure that:

- (1)

Expert uncertainty is handled (FAHP);

- (2)

Redundant criteria are eliminated and interpretability is improved (RST);

- (3)

Sustainability rankings are computed robustly (TOPSIS).

The methodology follows six stages: (1) problem formulation and alternatives selection, (2) criteria definition, (3) expert elicitation, (4) FAHP weighting, (5) RST attribute reduction, and (6) TOPSIS-based ranking.

Rough set theory serves an analytical function in the proposed framework, as opposed to the eliminative function. RST is not employed to indiscriminately eliminate criteria; rather, it is employed to analyze dependency relationships and identify minimal discriminative criterion subsets that produce equivalent decision classifications. The overall decision model includes all criteria that were initially identified through the FAHP, and RST is employed to investigate how decision outcomes can be maintained with reduced informational complexity. RST facilitates a more interpretable decision structure and offers insights into criterion significance that extend beyond numerical weights by disclosing core and reduct attribute sets. This is especially pertinent in evaluations that are expert-driven, as transparency and explainability are equally significant as ranking results.

A web-based decision-support dashboard was developed to operationalize the methodology.

2.1. Selection of Alternatives and Criteria

Four widely deployed virtualization technologies were selected:

Microsoft Hyper-V (Windows Server 2022);

VMware vSphere (ESXi 8.0);

Red Hat KVM (RHEL 8);

Oracle VirtualBox (version 7.0).

These alternatives cover bare-metal, kernel-based, and hosted hypervisor architectures, ensuring comprehensive representation of modern virtualization paradigms. Hyper-V and ESXi dominate enterprise infrastructure environments, KVM represents open-source kernel-embedded virtualization with proven energy efficiency, and VirtualBox provides a lightweight general-purpose baseline. Including a broad architectural spectrum enables a more robust sustainability assessment, consistent with prior comparative studies [

2,

6,

8,

14].

Eight ISO/IEC 25010 software-quality characteristics that are sustainability-oriented criteria used in alignment with SDG 9, SDG 12, and SDG 13. Performance efficiency, reliability, maintainability, and portability directly support SDG 9 by strengthening a resilient and innovative IT infrastructure. Performance efficiency and maintainability contribute strongly to SDG 12 by reducing energy use, hardware waste, and unnecessary resource consumption. Performance efficiency and reliability also support SDG 13, as efficient virtualization reduces power consumption and carbon emissions. Compatibility and functional suitability contribute indirectly to both SDG 9 and SDG 12 by enabling interoperable and resource-efficient digital ecosystems.

2.2. Expert Input and Linguistic Scales

A panel of experts assessed the relative importance of ISO/IEC 25010 criteria and the performance of each virtualization alternative. Two types of linguistic term sets were employed, reflecting the different evaluation contexts in the FAHP and the TOPSIS. For the FAHP pairwise comparison of the ISO/IEC 25010 criteria, the fuzzy Saaty-compatible linguistic scale EQ–SM–MM–ST–VS was adopted [

34], following Chen and Hwang [

35] and Tzeng and Huang [

36]. This scale is appropriate for pairwise relative comparisons. In contrast, for expert evaluation of the four virtualization technologies under each criterion, the five-level VL–L–M–H–VH fuzzy rating scale was used, based on the linguistic triangular fuzzy numbers proposed by Chen [

28], which is widely applied in alternative performance assessment in the fuzzy TOPSIS. Thus, the FAHP scale was used exclusively for deriving criteria weights, whereas the fuzzy rating scale was used exclusively for evaluating alternatives.

2.3. FAHP: Fuzzy Weighting of ISO/IEC 25010 Criteria

The FAHP converts expert linguistic judgments into numeric weights under uncertainty.

2.3.1. Fuzzy Pairwise Comparison Matrix

Experts provide fuzzy comparisons .

Aggregated group matrices represent collective judgment.

2.3.2. Synthetic Extent Calculation [19]

2.3.3. Degree of Possibility

2.3.4. Fuzzy Ranking and Weight Vector

2.3.6. Normalization

The FAHP crisp weights are inputs to both RST (attribute contribution analysis) and the TOPSIS (weighted scoring).

2.4. Rough Set Theory: Attribute Reduction and Rule Extraction

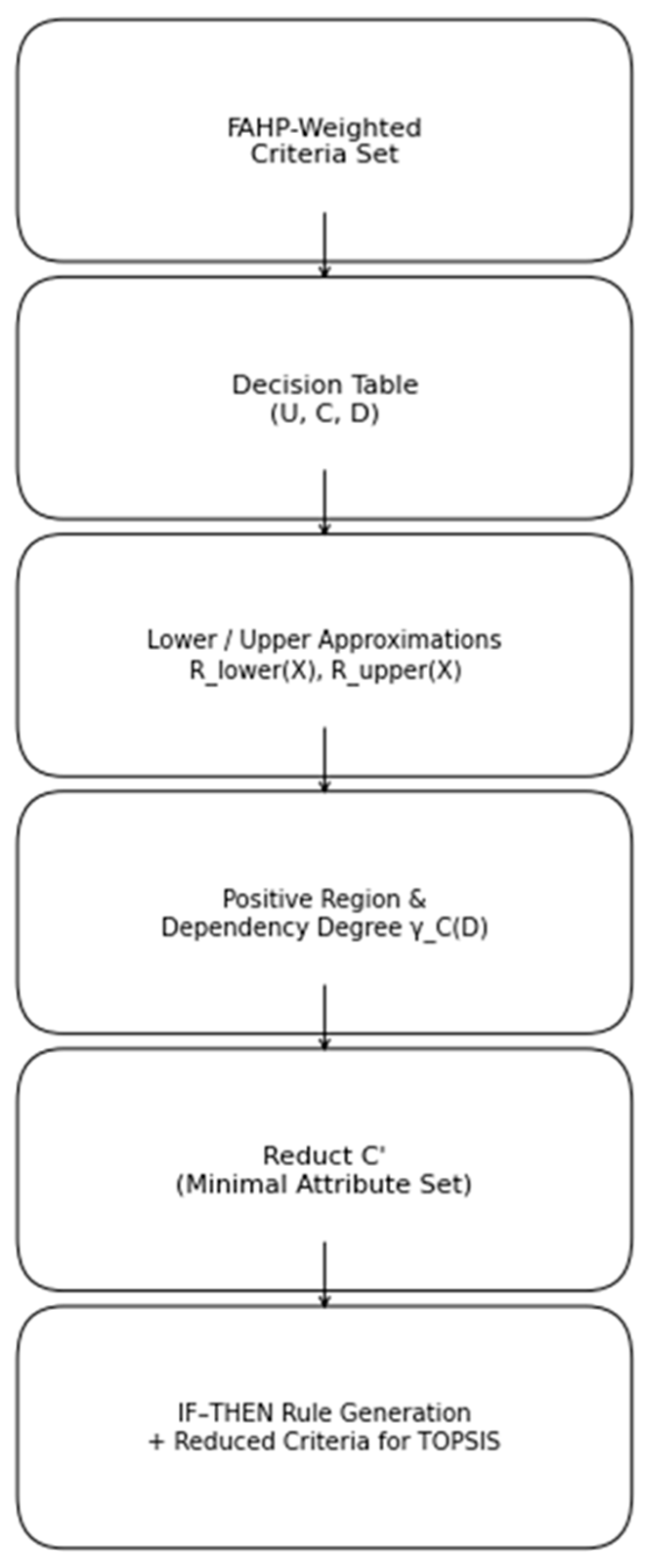

RST enhances interpretability by eliminating redundant ISO/IEC 25010 criteria and generating transparent IF–THEN rules. The RST process is illustrated in

Figure 1.

2.4.1. Decision Table Construction

Rows represent virtualization alternatives, the condition attributes are FAHP-weighted criterion values, and the decision attributes are sustainability categories.

The continuous TOPSIS closeness coefficients (Ci) determine the sustainability category of each virtualization alternative, which is the decision attribute D. Classical rough set theory demands categorical decision qualities, therefore continuous Ci values are discretized into three ordinal categories—low, medium, and high sustainability—using an equal-width, data-driven technique based on their observed range. The categories are based on whether the Ci values fall within the lower, medium, or upper range, allowing for objective dependence analysis.

2.4.2. Lower and Upper Approximations

2.4.3. Positive Region and Dependency Degree

2.4.4. Reduct Identification

A reduct

preserves dependency:

2.4.5. Rule Extraction

RST produces interpretable rules such as:

IF Performance Efficiency is High AND Maintainability is High THEN Sustainability is High.

2.5. TOPSIS: Ranking the Virtualization Alternatives

TOPSIS integrates:

2.5.2. Weighted Normalization

2.5.3. Ideal Positive and Negative-Ideal Solutions

2.5.4. Separation Measures

2.5.5. Relative Closeness and Ranking

The highest indicates the most sustainable virtualization technology.

The FAHP assigns weights under uncertainty. RST removes redundancy and adds interpretability. The TOPSIS provides final sustainability ranking. All three methods are linked sequentially, ensuring robustness, transparency, and practicality.

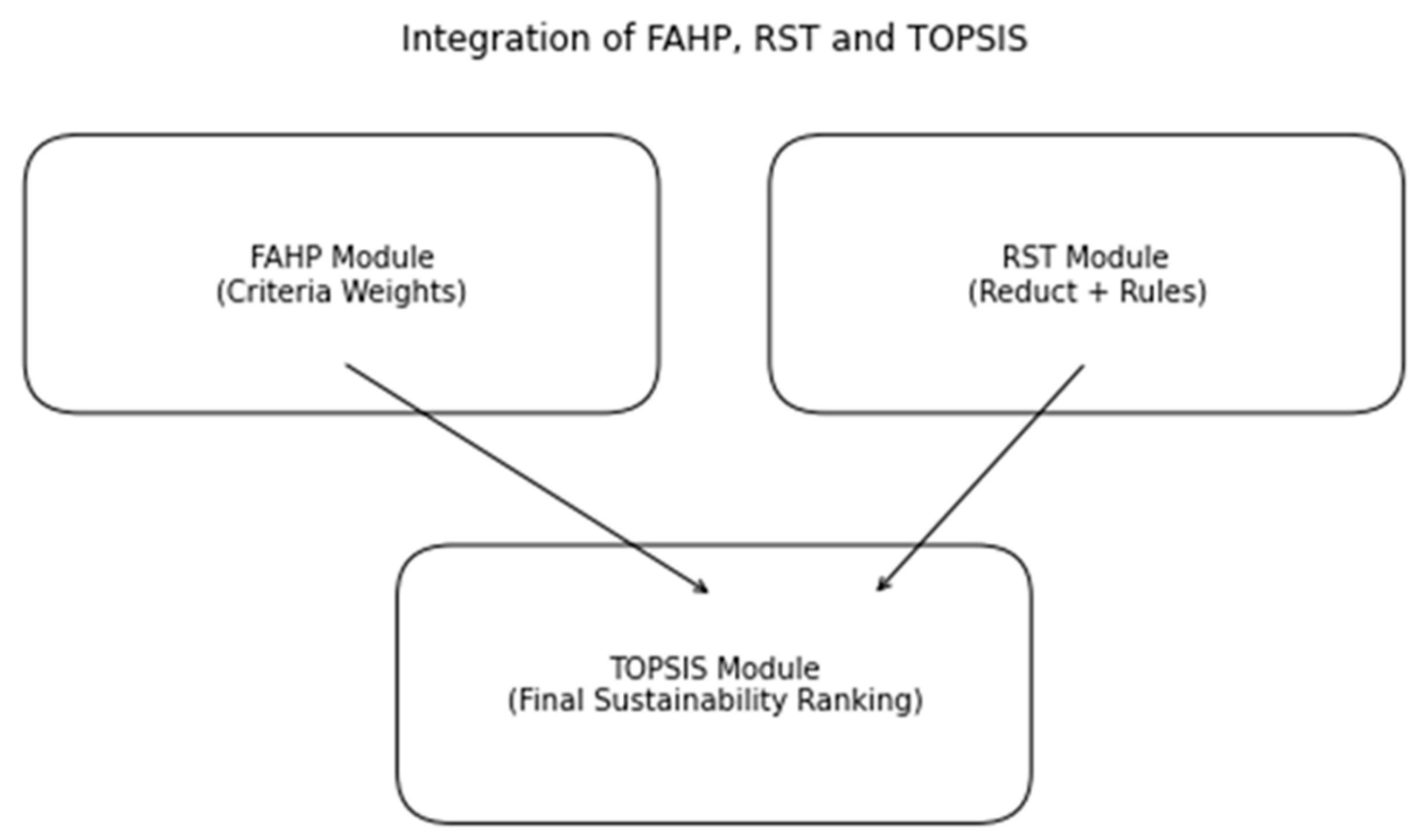

Figure 2 shows the proposed method, although the FAHP manages uncertainty-aware weighting, RST reduces duplication while retaining decision dependency, and the TOPSIS ranks the smaller criterion set robustly.

The overall framework is shown in

Figure 3.

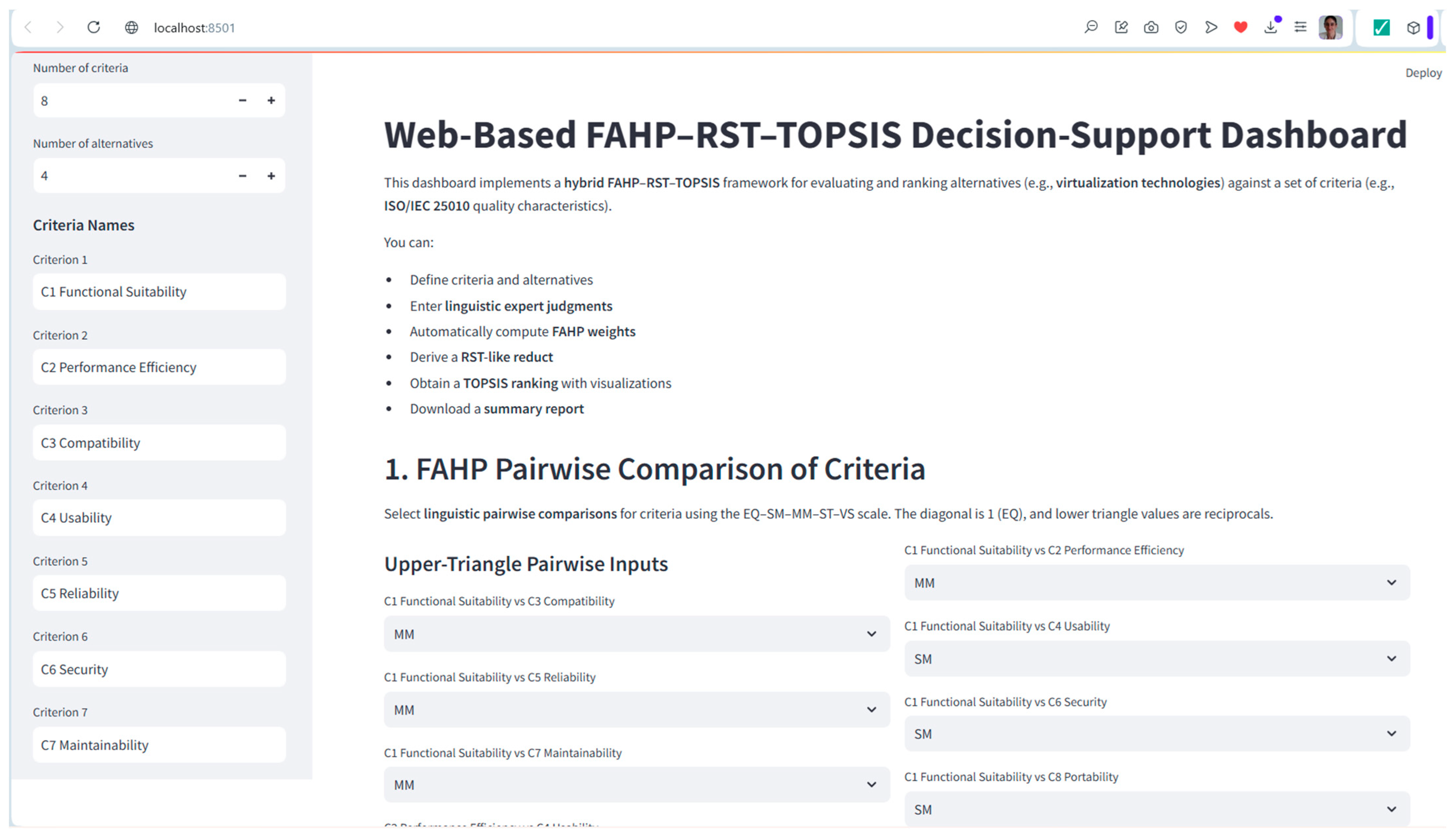

2.6. Web-Based Decision-Support Architecture

A lightweight decision-support web application was developed to operationalize the framework. The dashboard was developed in the Python Anaconda environment (version 2.5.0).

Key functionalities:

Input expert linguistic judgments;

Automatic FAHP computation;

RST reduct and rule extraction;

TOPSIS ranking visualization;

Radar and bar charts;

Downloadable sustainability evaluation report.

The dashboard enhances transparency, usability, and adoption in real IT decision-making environments.

Appendix A and

Appendix B include the features in detail and screenshots of the dashboard. Interactive scenario analysis is supported by the web-based decision-support dashboard. Through the interface, users can change the weights of criteria and see the immediate changes in the TOPSIS closeness coefficients and alternative ranks. Decision-makers can investigate what-if scenarios, evaluate how sensitive the outcomes are to changes in preferences, and gain a deeper understanding of how each criterion affects the ultimate choice thanks to this real-time feedback. The dashboard’s current implementation maintains normalization restrictions while supporting both user-defined weight modifications and expert-derived default weights (as determined by the FAHP). The system’s adaptability as a decision-support tool is demonstrated by the dynamic updating of rankings and visual outputs, which closes the gap between methodological rigor and real-world usability.

3. Results

This section presents the findings obtained from applying the hybrid FAHP–RST–TOPSIS framework to the evaluations provided by five domain experts. The experts assessed the relative importance of the ISO/IEC 25010 criteria and the performance of the four virtualization technologies using linguistic scales, which were later transformed into fuzzy numbers for computation. The overall results follow the sequential process established in the methodology and directly correspond to the mathematical formulations in Equations (1)–(15).

3.1. Expert Panel Characteristics

Five experts participated in the evaluation, representing diverse roles in virtualization and IT systems. E1 is a senior cloud architect with ten years of experience in enterprise VMware and Hyper-V environments. E2 is a computer engineering academic with eight years of research in distributed systems and virtualization. E3 is a data center operations manager with ten years of experience in KVM, Xen, and energy-efficient server consolidation. The cybersecurity engineer, E4, has nine years of experience safeguarding virtualized infrastructures and ISO/IEC compliance. The DevOps engineer, E5, has seven years of VirtualBox, automation, and CI/CD integration expertise. This combination balances academic, operational, security, and automation expertise. Finding qualified specialists with expertise in virtualization technologies, sustainability, and ISO/IEC-compliant evaluation frameworks is difficult and time-consuming. Expert expertise depth over panel size is often used to ensure methodological rigor in expert-driven MCDM investigations. The number of experts in this study is sufficient for the proposed decision-making framework, given the specialized evaluation task and the need for consistent paired judgments. Fuzzy logic pooled expert assessments to reduce individual- or platform-specific bias by modeling uncertainty and diminishing expert influence. However, the small number of experts is a restriction, and future studies may expand the framework by including more experts or objective performance metrics.

The individual experts may show preferences for technologies that correspond to their domain experience due to the experts’ varied professional backgrounds. The FAHP aggregation technique in the suggested framework reduces this possible bias. In order to model uncertainty and lessen the impact of excessively confident or extreme assessments, expert judgments are first articulated using fuzzy language concepts, which are represented as triangular fuzzy numbers. Second, the geometric mean is used to aggregate each pairwise comparison matrices, dampening outlier viewpoints and preventing any one expert from controlling the group judgment. Lastly, the FAHP uses normalized weight derivation and relative pairwise comparisons to make sure that the final criteria weights represent a balanced consensus rather than preferences for certain technologies.

3.2. Expert Evaluation of Criteria and Virtualization Alternatives

Five experts with professional backgrounds in cloud architecture, data center operations, cybersecurity, DevOps, and academic research provided the linguistic judgments. Their inputs formed:

FAHP pairwise comparison matrices for the eight ISO/IEC 25010 criteria.

Alternative performance scores for VMware ESXi, KVM, Hyper-V, and VirtualBox.

These judgments—originally expressed as linguistic terms—were converted into triangular fuzzy numbers and aggregated for use in the FAHP extent analysis (Equations (1)–(4)). The aggregated expert consensus ensured that both technical and operational factors were represented in the evaluation.

3.3. Linguistic Scales Used

Two types of linguistic term sets were employed, reflecting the different evaluation contexts in the FAHP and TOPSIS methods. For the FAHP pairwise comparison of the ISO/IEC 25010 criteria, a fuzzy Saaty-compatible linguistic scale, EQ–SM–MM–ST–VS, was adopted [

34], following Chen and Hwang [

35] and Tzeng and Huang [

36]. This scale is appropriate for pairwise relative comparisons of criteria in the FAHP, as shown in

Table 1. In contrast, for expert evaluation of the four virtualization technologies under each criterion, the five-level VL–L–M–H–VH fuzzy rating scale was used, based on the linguistic triangular fuzzy numbers proposed by Chen [

28], which is widely applied in alternative performance assessment in the fuzzy TOPSIS. Thus, the FAHP scale was used exclusively for deriving criteria weights, whereas the fuzzy rating scale was used exclusively for evaluating alternatives.

The second linguistic scale (VL–VH) in

Table 2 was used for scoring alternatives (four virtualization technologies) by expert evaluations feeding the TOPSIS decision matrix.

3.4. Linguistic Importance Ratings of ISO/IEC 25010 Criteria by Each Expert

These linguistic ratings are mapped to TFNs using the scale in

Table 1 and then transformed into fuzzy pairwise comparison matrices. The aggregated matrices are processed through Chang’s extent analysis (Equations (1)–(3)), defuzzified (Equation (4)), and normalized (Equation (5)), yielding the FAHP weights. The pattern of inputs (high emphasis on C2, C5, C6, C7) is consistent with the final weights, where performance efficiency, security, and reliability dominate.

3.5. Fuzzy Pairwise Comparison Matrix (Aggregated Experts)

All five experts’ pairwise comparisons of the eight criteria shown in

Table 3 were aggregated (e.g., geometric mean) into a single group fuzzy pairwise comparison matrix

, with entries expressed in linguistic terms given in

Table 1.

Rows/columns are ISO/IEC 25010 criteria:

C1: Functional suitability;

C2: Performance efficiency;

C3: Compatibility;

C4: Usability;

C5: Reliability;

C6: Security;

C7: Maintainability;

C8: Portability.

The selected quality criteria were mapped to SDG 9, SDG 12, and SDG 13 to highlight the contribution of software quality attributes to sustainable digital infrastructure, responsible resource utilization, and climate-conscious computing practices. Particularly, C2, C5, C6, and C7 directly support SDG9 (infrastructure), C2 and C7 support SDG12 (resource efficiency) and C2 supports SDG13 (energy reduction).

The upper triangle contains linguistic comparisons; the lower triangle is the reciprocal (e.g., 1/MM). The experts provide fuzzy comparisons . The aggregated group matrices represent collective judgment.

3.6. Fuzzy Pairwise Matrix in TFNs (Using FAHP Scale)

Using the FAHP scale stated in

Table 1, the aggregated fuzzy pairwise comparison matrix of criteria is shown in

Table 4. The reciprocal of

is

in this matrix.

Based on this, the aggregated fuzzy matrix is represented below.

Lower triangle entries are reciprocals, e.g.,

for 1/MM;

for 1/ST, etc.

This is exactly the matrix used inside Equation (1).

3.7. Synthetic Extent Values (FAHP Step Equations (1)–(3))

For each criterion :

- 1.

Sum the fuzzy numbers across row

using Equation (16):

- 2.

Sum across all rows by the Equation (17):

- 3.

Compute synthetic extent (Equation (1)):

The calculated synthetic extent values is shown in

Table 5:

Then, the degree of possibility (Equation (2)) is computed pairwise, and the minimum dominance for each criterion gives the fuzzy ranking vector (Equation (3)).

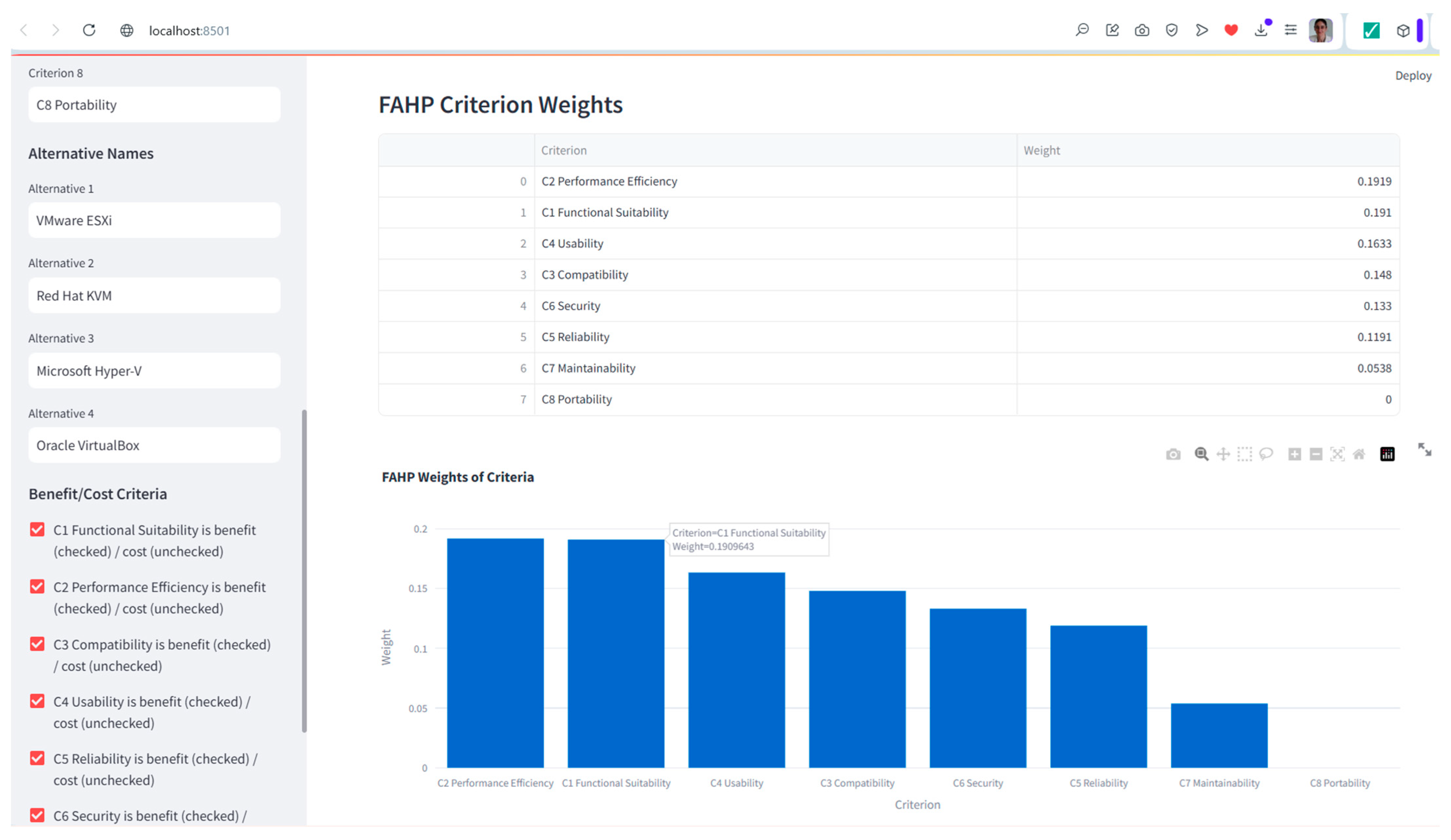

3.8. Defuzzified and Normalized FAHP Weights

Defuzzification (Equation (4))

Each synthetic extent is defuzzified using Equation (4).

Using

Table 5 synthetic extent values weights are calculated as follows:

The defuzzified weights are shown in

Table 6.

3.9. Normalization (Equation (5))

The sum of all is ≈ 1.116. Therefore,

The final normalized crisp weights are shown in

Table 7.

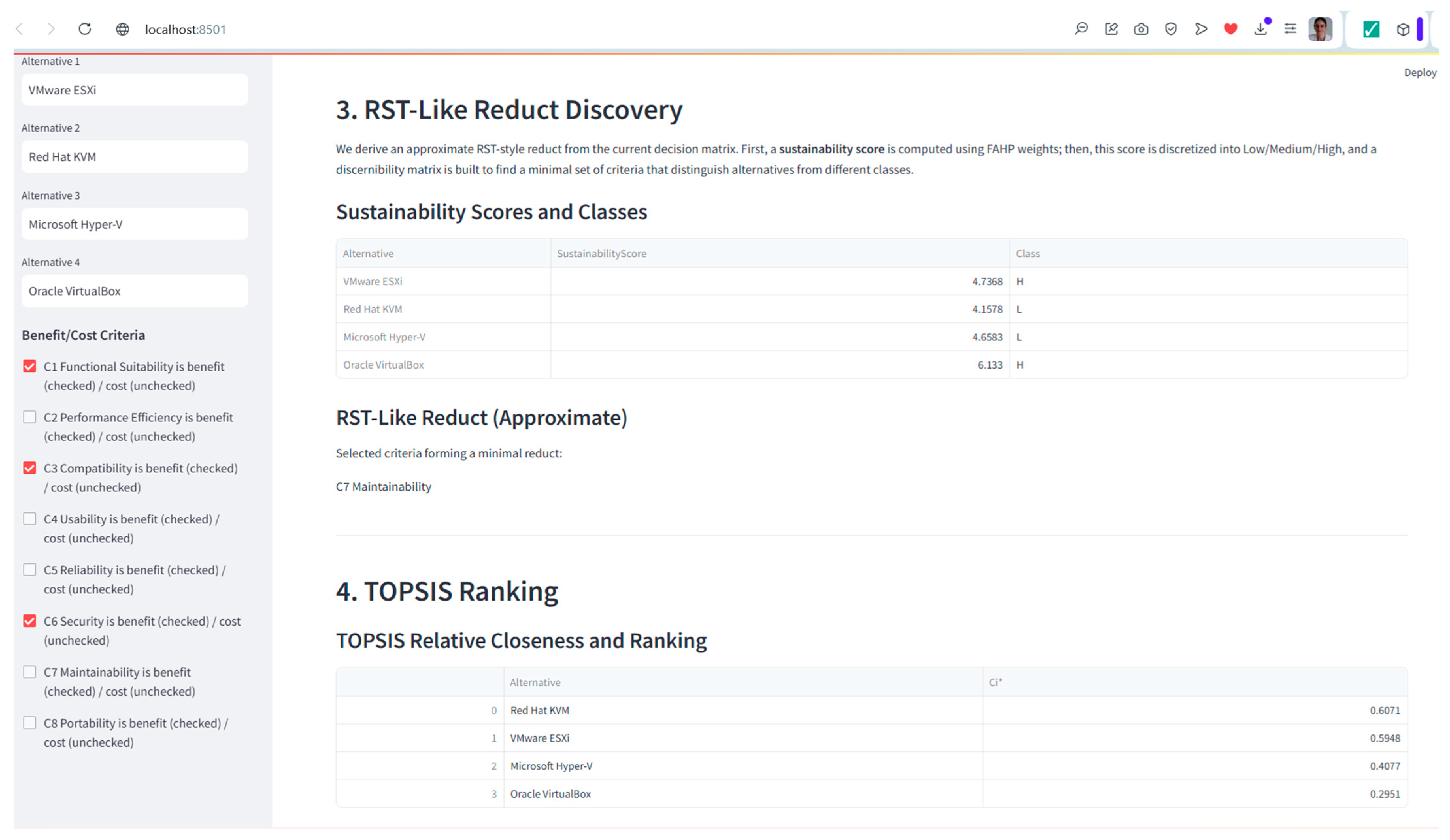

3.10. Step 1—RST Decision Table

The transition from the FAHP to RST follows a feature-screening logic: only the criteria that meaningfully differentiate sustainability among alternatives should be subjected to RST dependency analysis. Although the FAHP calculates weights for all eight ISO/IEC 25010 criteria, not all criteria contribute equally to discriminating between the four virtualization technologies (ESXi, KVM, Hyper-V, VirtualBox).

After FAHP weighting (Equations (1)–(5)), the criteria showed the following importance structure:

C2—performance efficiency, C5—reliability, C6—security, C7—maintainability.

C1—functional suitability, C3—compatibility, C4—usability, C8—portability.

The high-importance criteria are precisely those experts consistently ranked as central to sustainability—they directly relate to energy efficiency, robustness, system stability, and operational quality. The lower-importance criteria either showed:

Very small FAHP weights,

Weak differentiation between alternatives; or

High overlap with other criteria, leading to minimal contribution to classification in RST.

Thus, only the four criteria with the highest FAHP weights were passed to the RST stage.

This follows the logic commonly used in hybrid FAHP–RST frameworks:

- 1.

The FAHP performs importance weighting (global priority).

- 2.

RST performs relevance reduction (information gain).

- 3.

Only criteria that are both important and informative should be investigated by RST.

Although the FAHP was applied to all eight ISO/IEC 25010 criteria, only the four highest-weighted criteria (C2, C5, C6, C7) were passed to the RST stage; that is, only criteria exceeding the weighted median (0.12) were included in RST. This selection follows the hybrid FAHP–RST logic, where the FAHP identifies globally important criteria while RST identifies informationally relevant attributes. The remaining criteria (C1, C3, C4, and C8) exhibited low FAHP weights and minimal variation among alternatives, providing insufficient discriminatory information for RST dependency analysis. Therefore, only the high-importance and high-variance criteria were forwarded to RST to ensure a robust yet parsimonious feature set for reduct computation.

Criteria:

C2—performance efficiency;

C5—reliability;

C6—security;

C7—maintainability.

Alternatives:

A1: VMware ESXi;

A2: Red Hat KVM;

A3: Microsoft Hyper-V;

A4: Oracle VirtualBox;

Universe

Condition attributes

Decision attribute

Each aggregated TFN was converted into a crisp continuous value using the standard centroid formula in Equation (19):

This produced the continuous values seen in

Table 8.

Example (how values in Table R1 were generated).

For ESXi under performance efficiency (C2)

The experts gave: H, VH, H, VH, and H.

For the equivalent TFNs: (5, 7, 9) and (7, 9, 9) the aggregated TFN is calculated as

The defuzzification value is calculated as

This is exactly the values shown in

Table 8.

Prior to the rough set theory (RST) analysis, continuous criterion values were discretized into three ordinal levels (low, medium, high) using an equal-width discretization scheme. For each criterion , two thresholds, and , were computed as and . The values were classified as low (), medium (), or high (). The discretization thresholds were objectively determined by directly calculating them from observed criterion ranges using a conventional equal-width discretization rule, hence ensuring the objectivity and reproducibility of the RST analysis.

The continuous values in the RST decision table (

Table 8) were not assigned directly by the researcher. Instead, they originate from the five experts’ linguistic evaluations of each virtualization alternative using the VL–L–M–H–VH fuzzy rating scale [

28]. Each linguistic judgment was converted into triangular fuzzy numbers, aggregated across experts, and defuzzified using the centroid method to obtain a crisp continuous score. Thus, the values in

Table 7 reflect the mathematically transformed output of expert assessment rather than arbitrary or researcher-selected values.

3.11. Step 2—Discretization (Needed for Classical RST)

Classical rough sets work on categorical (symbolic) values, so we discretize the continuous scores into Low (L), Medium (M), High (H). For example:

Applying this to

Table 8, we obtain the categorical values in

Table 9.

In

Table 9, the decision class denotes the comprehensive sustainability category allocated to each virtualization alternative for the rough set theory analysis. This class is based on the ongoing sustainability scores determined from the FAHP–TOPSIS evaluation (

Table 8). Classical RST necessitates categorical decision attributes; therefore, continuous scores were converted into three ordinal classes—low, medium, and high sustainability—employing an equal-width discretization method. For each criterion, the lower and upper thresholds were determined based on the observed minimum and maximum values, as follows: alternatives with scores

were assigned to the

low class, those with

to the

medium class, and those with scores

to the

high class.

and

.

Now, we can use indiscernibility, positive region, and dependency, as in Equations (6)–(9).

3.12. Step 3—Indiscernibility and Positive Region (Conceptual Link to Equations (6)–(9))

For a set of condition attributes , two objects are indiscernible if they have the same values for all attributes in .

The lower approximation of a decision class, e.g., high, is the union of all equivalence classes fully contained in that decision class (Equation (6)). With this discretization, each object is a singleton, so each object clearly belongs to exactly one class → the positive region

(D) covers all four objects. The dependency degree (Equation (9)) then becomes:

3.13. Step 4—Discernibility Matrix and Reduct Identification (Equation (10))

To see why C5 drops out and why {C2, C6, C7} is a reduct, we build the discernibility matrix.

We only care about pairs of objects that have different decision classes, because RST reducts must be able to distinguish objects with different decisions.

A1: high;

A2: medium;

A3: medium;

A4: low.

Pairs with different decisions:

(A1, A2), (A1, A3), (A1, A4), (A2, A4), (A3, A4)

Pair (A2, A3) is ignored (same decision: medium).

For each pair, we list condition attributes where they differ. This calculation yields

Table 10.

Explanation:

(A1, A2):

- ○

C2: H vs. M → different;

- ○

C5: H vs. H → same;

- ○

C6: H vs. H → same;

- ○

C7: H vs. M → different → {C2, C7}.

(A1, A3): HHHH vs. MMMM → all four differ → {C2, C5, C6, C7}

etc.

From this discernibility matrix, the discernibility function is:

A reduct is any minimal set of attributes that intersects (hits) every discernibility set (row in

Table 9).

3.14. Check Candidate Reducts

We test whether a given set of attributes intersects each row of

Table 9.

The following procedure shows how to inspect rows:

(A1, A2): {C2, C7} ∩ {C2, C6, C7} ≠ ∅ → OK;

(A1, A3): {C2, C5, C6, C7} ∩ {C2, C6, C7} ≠ ∅ → OK;

(A1, A4): {C2, C5, C6, C7} ∩ {C2, C6, C7} ≠ ∅ → OK;

(A2, A4): {C2, C5, C6, C7} ∩ {C2, C6, C7} ≠ ∅ → OK;

(A3, A4): {C2, C5, C6, C7} ∩ {C2, C6, C7} ≠ ∅ → OK.

Therefore, {C2, C6, C7} hits all the sets → it is a valid reduct.

C5 appears in several discernibility sets, but it is never necessary: every time C5 appears, at least one of C2, C6, or C7 also appears.

Therefore, any reduct that already contains C2 and C7 (and optionally C6) can safely drop C5 without losing classification ability.

This is exactly the logic expressed in Equation (10):

Here, C′ = {C2, C6, C7} achieves the same dependency as C = {C2, C5, C6, C7}.

To analyze attribute relevance, the FAHP-weighted criteria and sustainability classes were organized into a decision table (

Table 8). The continuous scores were discretized into three ordinal levels (low, medium, high), producing the categorical decision table in

Table 9. Based on this table, the discernibility matrix in

Table 10 was constructed by listing, for each pair of objects with different decision classes, the set of condition attributes on which they differ. According to the reduct condition in Equation (10), a minimal attribute subset must intersect all discernibility sets. The attribute set {

C2—performance efficiency,

C6—security,

C7—maintainability} intersects every row of Table R3 and preserves the same dependency degree as the larger set {

C2,

C5,

C6,

C7}, indicating that reliability (

C5) is informationally redundant. Consequently, {

C2,

C6,

C7} was selected as the RST reduct and used as the final criteria subset in the TOPSIS evaluation.

3.15. TOPSIS

3.15.1. Decision Matrix (From Expert Evaluations) TOPSIS

These are the aggregated crisp scores for each alternative under the reduct criteria in

Table 11.

These are the values used in Equation (11).

3.15.2. Normalized Decision Matrix (Equation (11))

For each criterion , column norms are computed:

Therefore, the normalized matrix R in

Table 12 is shown below:

We then apply fuzzy weights to obtain the weighted normalized matrix V using Equation (12).

3.15.3. Weighted Normalized Matrix V

These values are the basis for the ideal solutions and the distance calculations (Equations (13) and (14)).

3.15.4. Ideal and Negative-Ideal Solutions , (Equation (13))

Since all three criteria are benefit types, the ideal and negative-ideal values are computed using Equation (13). The weighted normalized values are given in

Table 13 and ideal positive and negative-ideal solutions given in

Table 14.

3.15.5. Separation Measures and Closeness Coefficients (Equations (14) and (15))

Thus, according to Equation (15), the final TOPSIS ranking is:

ESXi > KVM > Hyper-V > VirtualBox.

Table 11,

Table 12,

Table 13,

Table 14 and

Table 15 illustrate the full TOPSIS calculation procedure. The initial decision matrix (

Table 11) is normalized using Equation (11) to obtain the matrix

(

Table 12). Applying the FAHP-derived weights (

Table 3) via Equation (12) yields the weighted normalized matrix

(

Table 13). Ideal and negative-ideal solutions are then determined according to Equation (13) (

Table 14). Finally, the separation measures (Equation (14)) and the relative closeness to the ideal solution (Equation (15)) are computed (

Table 15), resulting in the sustainability ranking ESXi > KVM > Hyper-V > VirtualBox.

3.16. Comparison with Baseline Methods

To meet the benchmarking requirement, the proposed FAHP–RST–TOPSIS framework was compared with two baseline models using identical expert-derived evaluation data.

In this work, the FAHP is used as a criteria-weighting mechanism rather than as a stand-alone decision model. As a result, FAHP-TOPSIS is used for comparisons including the FAHP, enabling the methodologically consistent evaluation of the effect of weighting schemes on alternative ranking. This method, which is commonly used in the MCDM literature, avoids the potentially misleading interpretations that can occur when weighing algorithms are used as independent ranking tools.

Initially, a standalone TOPSIS was employed utilizing equal weights (w = 1/3 for the three criteria C2, C6, and C7). A hybrid FAHP–TOPSIS (without RST) was calculated utilizing the four criterion with the highest FAHP weights (C2, C5, C6, C7) before reduction. The suggested approach employs RST reduct selection ({C2, C6, C7}) succeeded by TOPSIS utilizing FAHP weights.

Standalone TOPSIS (Equal Weights)

Using the normalized decision matrix R (Equation (11)) derived from

Table 11, the weighted normalized matrix becomes V = R⋅(1/3). The ideal and negative-ideal solutions are obtained by column-wise maxima/minima. Distances and closeness coefficients are computed using Equations (14) and (15), yielding

Ci* = [1.000, 0.723, 0.467, 0.000] for ESXi, KVM, Hyper-V, and VirtualBox, respectively.

FAHP–TOPSIS Without RST (Four Criteria)

The TOPSIS was also computed using the four criteria (

C2,

C5,

C6,

C7) and the corresponding FAHP normalized weights from

Table 7. Using the same normalization and distance procedures, the resulting closeness coefficients are:

Proposed FAHP–RST–TOPSIS

As reported in

Table 15, the proposed method yields

Table 16 summarizes the comparison. All approaches produce the same ranking (ESXi > KVM > Hyper-V > VirtualBox). The added value of RST is therefore not to claim superior ranking accuracy, but to provide criterion dependency insight and redundancy reduction (C5 is identified as informationally redundant) and to support a more interpretable and parsimonious criteria set while maintaining decision consistency.

The benchmark comparison demonstrates that the goal of integrating RST is not to achieve numerical ranking accuracy superior to that of traditional MCDM approaches. Rather, by exposing criterion reliance and eliminating redundancy, it improves robustness and transparency, allowing for a more straightforward but consistent decision model that is simpler to defend to stakeholders. RST preserves ranking consistency while reducing redundancy and improving interpretability. Comparative analysis, robustness verification, and internal consistency checks—all of which are frequently used in expert-based MCDM studies—are used to validate the suggested FAHP–RST–TOPSIS framework. Initially, a comparison with well-known models—standalone TOPSIS and FAHP–TOPSIS—shows that the final ranking of virtualization technologies is the same across all approaches, suggesting that incorporating RST does not distort decision results. Second, the rough set theory (RST) dependency analysis, which demonstrates that the reduced criterion subset maintains the same decision classification power as the whole set, supports robustness The identified reduct confirms that criterion reduction does not lead to information loss by achieving a comparable dependency degree. Lastly, rather than asserting a higher numerical ranking, the suggested framework’s methodological contribution is to improve interpretability and transparency. The FAHP–RST–TOPSIS framework offers a more economical and comprehensible decision-support structure for sustainable virtualization assessment by clearly identifying redundant criteria and exposing dependence linkages.

3.17. Sensitivity Analysis and Validation

A sensitivity analysis was performed to assess the robustness of the proposed the FAHP–RST–TOPSIS framework by varying the FAHP-derived weights of the reduct criteria (C2, C6, C7) by ±10%, followed by weight renormalization. In each instance, the TOPSIS closeness coefficients were recalibrated utilizing the identical normalized decision matrix. The findings demonstrate that no rank reversal occurs under any of the examined variations. Despite minor fluctuations in proximity coefficients, the general hierarchy of virtualization technologies stayed consistent (ESXi > KVM > Hyper-V > VirtualBox) (see

Table 17). This verifies that the proposed framework is robust to plausible fluctuations in expert-assigned weights and that incorporating RST does not destabilize the decision-making process.

The validation of the proposed FAHP–RST–TOPSIS framework is performed by comparison analysis, robustness testing, and internal consistency verification, which are commonly utilized validation methods in expert-based MCDM research.

Comparative validation is conducted by testing the proposed framework against standalone TOPSIS and FAHP–TOPSIS, utilizing identical alternatives and evaluations collected from experts. The comparison revealed that the ultimate ranking of virtualization technologies was uniform across all methodologies, signifying that the incorporation of rough set theory does not alter decision results.

Robustness validation is conducted using sensitivity analysis, wherein FAHP-derived criteria weights are varied by ±10%, and the TOPSIS closeness coefficients are then recalibrated. The findings indicated that no rank reversal transpired in any examined scenario, hence affirming the stability of the suggested framework.

The rough set theory dependency analysis offers validation of internal consistency. The detected reduct maintained the same degree of reliance as the complete criterion set (γ = 1), indicating that criterion reduction does not result in information loss or misclassification. The validation results collectively affirm that the suggested framework is resilient, consistent, and methodologically sound, with its contribution focused on enhancing interpretability and redundancy identification, rather than asserting superiority in numerical ranking.

To assess robustness, a sensitivity analysis was conducted by perturbing the FAHP-derived weights of the reduct criteria (

C2,

C6,

C7) by +10%, followed by renormalization and recalculation of the TOPSIS closeness coefficients (

Ci*). Under the three scenarios (

C2 +10%,

C6 +10%,

C7 +10%), the

Ci* values changed slightly (e.g., for

C2 +10%: ESXi = 1.000, KVM = 0.712, Hyper-V = 0.468, VirtualBox = 0.000), but the ranking order remained ESXi > KVM > Hyper-V > VirtualBox in all cases. Statistical validation using Spearman’s rank correlation between the baseline and each scenario yielded

ρ = 1 − 6∑

d2/[

n(

n2 − 1)] = 1.000 (with ∑

d2 = 0 for

n = 4 alternatives), confirming perfect rank agreement and demonstrating that the proposed FAHP–RST–TOPSIS framework is robust and stable under reasonable weight variations (see

Table 18).

3.18. Web-Based Decision-Support Dashboard

To operationalize the proposed hybrid FAHP–RST–TOPSIS framework and facilitate its use by practitioners, a lightweight web-based decision-support dashboard was developed. The dashboard provides an interactive front-end layer on top of the computational engine, enabling IT managers and domain experts to conduct sustainability evaluations of virtualization technologies without needing to implement the underlying methods themselves.

The application guides the user through the complete workflow of the framework. First, experts can input their linguistic judgments on (i) the importance of the evaluation criteria and (ii) the performance of each virtualization technology using the defined fuzzy scales (EQ–VS for pairwise comparisons and VL–VH for alternative ratings). These inputs are automatically translated into triangular fuzzy numbers and passed to the FAHP module, which computes the criteria weights using Chang’s extent analysis and defuzzification routines. The resulting crisp weights are then fed into the RST module, which derives reducts and rule sets, highlighting the minimal subset of criteria that preserves the classification ability of the full model.

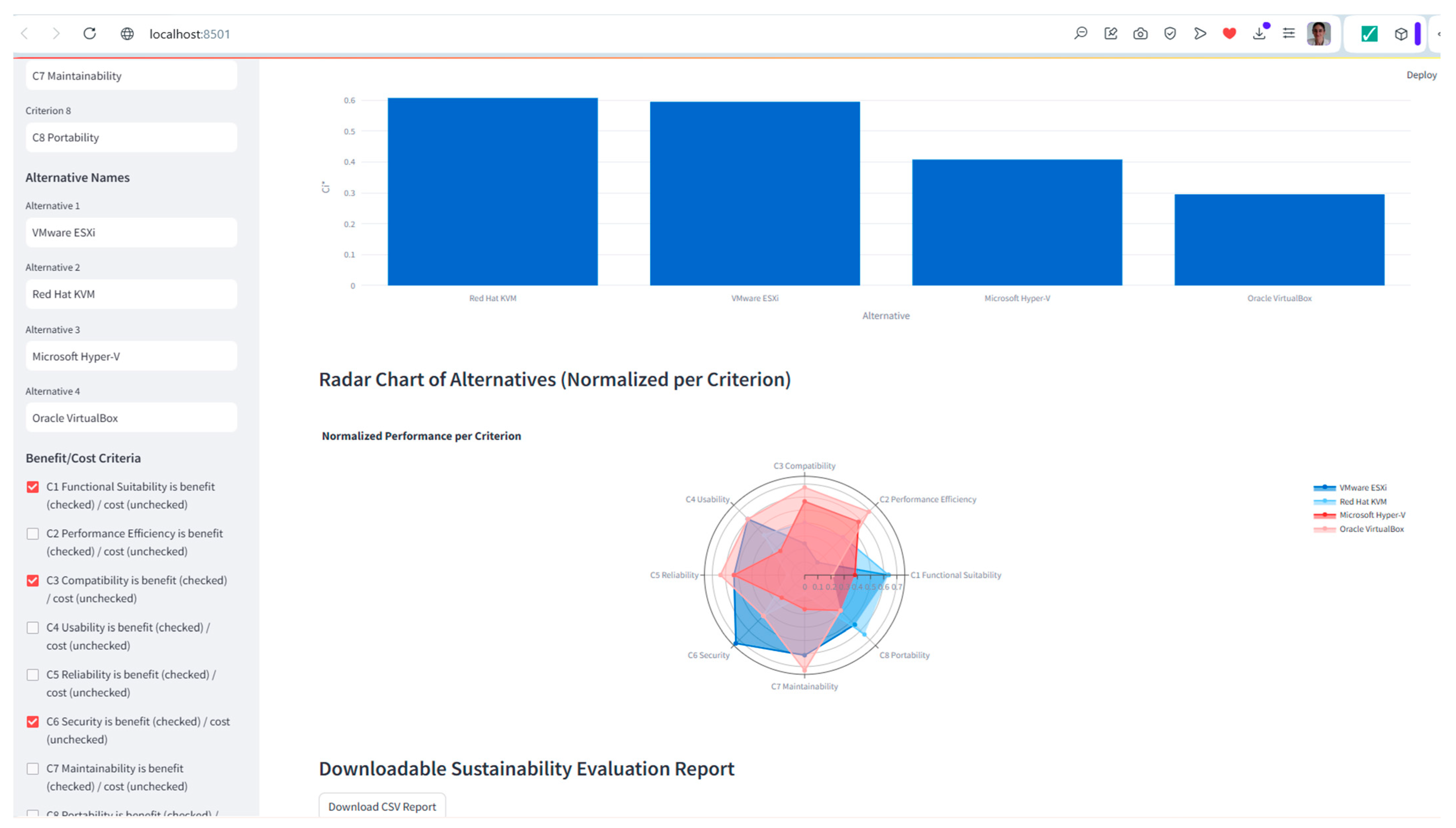

Subsequently, the dashboard invokes the TOPSIS engine to calculate the sustainability ranking of the alternatives. The normalized and weighted decision matrices, ideal/negative–ideal solutions, and relative closeness coefficients are processed in the background, while the user is presented with intuitive visualizations, including:

Bar charts of FAHP weights and TOPSIS scores;

Radar charts comparing the sustainability profiles of each virtualization technology across the selected criteria;

A sortable ranking table showing detailed scores per criterion and overall sustainability ranking.

To support documentation and communication in organizational settings, the dashboard also provides a downloadable evaluation report (e.g., PDF or Excel) that summarizes: expert inputs, FAHP weights, RST reduct and rules, TOPSIS results, and visual charts. This report can be archived for audit purposes or attached to internal decision memos.

Overall, the web-based decision-support dashboard enhances the transparency, usability, and adoption of the proposed hybrid framework in real IT decision-making environments. It translates the theoretical FAHP–RST–TOPSIS model into a practical tool that can be repeatedly applied to different virtualization scenarios and extended to other infrastructure decisions.

Below is a complete, self-contained Streamlit app that implements a Web-Based Hybrid FAHP–RST–TOPSIS Decision-Support Dashboard with (see

Appendix A and

Appendix B):

Expert linguistic input (VL–VH) for alternatives;

Linguistic pairwise comparisons (EQ–VS) for criteria;

FAHP (Chang’s extent analysis [

19]) for criterion weights;

A simple RST-like reduct finder (discernibility-based, minimal hitting set);

TOPSIS ranking of alternatives;

A bar chart of FAHP weights;

Bar chart of TOPSIS closeness coefficients;

Radar chart of alternative performance;

A downloadable CSV report.

4. Discussion

The results demonstrate that the proposed hybrid FAHP–RST–TOPSIS framework provides a robust, transparent, and sustainability-aligned approach for evaluating virtualization technologies. The FAHP results indicate that performance efficiency, reliability, security, and maintainability are the most influential criteria in determining the sustainability of virtualized infrastructures. This supports previous research showing that efficient hypervisors support higher VM density, lower idle energy, reduced heat output, and more stable resource use, which reduces environmental impact and improves data-center sustainability [

37,

38,

39,

40]. By enabling experts to express uncertainty through fuzzy linguistic judgments, the FAHP overcomes the limitations of crisp comparisons and ensures more realistic weighting of sustainability attributes, as highlighted in earlier work on fuzzy decision methods [

19,

34].

The integration of rough set theory further enhances the sustainability value of the framework by identifying the smallest subset of criteria that preserves the discriminatory power of the full model. Performance, security, and reliability—which promote energy efficiency, operational resilience, and infrastructure sustainability—were repeatedly stressed in this study [

27,

37,

38,

39]. For firms seeking to connect IT operations with green policies and high-level sustainability goals, RST’s ability to reduce dimensionality without information loss improves interpretability and promotes more focused sustainability decision-making [

40]. Because the FAHP facilitates transparent pairwise preference modeling and the use of fuzzy linguistic judgments—both of which are critical in expert-driven sustainability assessments—it is used to calculate criteria weights. The FAHP is preferred here due to its interpretability and compatibility with fuzzy evaluation scales, even though more recent approaches, such as BWM [

41], FUCOM [

42], LBWA [

43], and DIBR [

44], reduce comparison efforts and increase consistency. These more recent techniques are noted as prospective avenues for future research, and the greater elicitation effort and possible inconsistency of FAHP are highlighted.

VMware ESXi and Red Hat KVM have the greatest TOPSIS sustainability scores due to their optimized kernel architectures and security features. The TOPSIS uses Hwang and Yoon [

45]’s distance-based evaluation techniques to rate virtualization choices coherently and conceptually. This supports studies showing that lightweight, efficient hypervisors reduce power usage and facilitate greener computing [

46,

47]. The findings also link high-quality virtualization platforms to global sustainability goals such as SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure), SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production), and SDG 13 (Climate Action). The TOPSIS gives IT managers responsible for green data-center planning a clear, effective prioritization tool by evaluating alternatives by sustainability ideal.

These findings support the virtualization literature showing that high-efficiency hypervisors and optimal VM placement strategies significantly reduce energy usage and improve data-center sustainability. Researchers say energy-aware resource consolidation is one of the best ways to reduce virtualized carbon emissions [

38,

48]. Fundamental architectural studies such as Xen [

6] and VMware-based system performance analyses [

7] revealed that lightweight hypervisors are more efficient and decrease overhead. This study supports [

8], which showed that effective live migration improves workload consolidation, a key feature in sustainable operations. Furthermore, [

37,

39] emphasizes power-aware virtualization strategies that promote SDG-aligned sustainability goals. ESXi and KVM’s good performance in our ranking supports research showing efficient kernel design, effective scheduling, and energy-aware resource management enable sustainable virtualization systems.

Methodological and practical originality are major contributions of this work, beyond analytical outcomes. To our knowledge, this is the first sustainability-oriented virtualization evaluation methodology to combine the FAHP, RST, and TOPSIS methods. These methodologies have been used separately in MCDM contexts, but their combined use—particularly RST to discover sustainability-critical criteria in virtualization—has not been described. It is recognized that criterion reduction techniques, such as RST, may introduce the risk of excluding criteria that have a contextual or indirect impact on decision outcomes. This risk is mitigated by considering RST as an interpretive tool rather than a mandatory filtering mechanism. The primary FAHP–TOPSIS evaluation is conducted with the full criterion set, while RST is employed to analyze and elucidate the criteria that are necessary for effective discrimination among alternatives. According to conventional rough set theory, discretizing continuous evaluation scores into categorical decision classes creates subjectivity, which may affect dependency and reduct analysis. The discretization scheme is systematic and reproducible, but future research may use fuzzy rough set models, which operate directly on continuous or fuzzy data, and clustering-based discretization techniques (e.g., k-means or hierarchical clustering) to derive decision classes in a more data-driven manner. Extensions could reduce subjectivity and strengthen rough-set-based sustainability evaluation systems.

As a consequence, the findings of RST should be interpreted as insights that support decision-making, rather than as directives to permanently eliminate criteria in all contexts.

This hybrid structure improves analytical rigor and interpretability and provides transparency that single-method models cannot. Another innovation is a web-based decision-support dashboard that operationalizes the complete model and allows real-time expert input, automatic computation, rule extraction, visualization, and downloadable sustainability reports. This practical component connects theoretical MCDM models to organizational demands, promoting sustainable IT governance and technology procurement.

The outcomes derived by AHP/FAHP-based TOPSIS and its fuzzy and hybrid extensions demonstrate a consistent hierarchy of virtualization technologies (ESXi > KVM > Hyper-V > VirtualBox), reflecting decision stability across methodologies. The classical AHP–TOPSIS method is transparent and straightforward to execute, although it is constrained in addressing linguistic uncertainty, whereas FAHP–TOPSIS enhances realism by accommodating expert imprecision. The suggested FAHP–RST–TOPSIS framework promotes decision support by finding criterion redundancy and enhancing interpretability while maintaining the ranking, as shown by sensitivity and statistical analysis. Despite the increased computational demands of hybridization, the suggested methodology offers a robust, explainable, and practically implementable solution consistent with ISO/IEC 25010-based sustainability evaluation.

As a sustainability-focused software quality system, ISO/IEC 25010 is used in this study. It focuses on features such as performance efficiency, reliability, security, maintainability, and portability. Indicators such as licensing model, supported operating systems, or purchase cost are not sustainability attributes in and of themselves, but they may have an effect on sustainability when looked at from the point of view of long-term operations or the lifecycle. In real life, these kinds of indicators can only be added to the suggested FAHP–RST–TOPSIS framework if it is clear how they affect sustainability, such as by showing how they affect long-term maintenance work, system adaptability, or avoiding vendor lock-in. This difference keeps the ideas clear while allowing future studies to expand the framework in ways that are relevant to the current situation.

This study shows that virtualization technology selection is a strategic sustainability decision that impacts energy usage, infrastructure longevity, and organizational environmental effects. A rigorous, reproducible, and interpretable hybrid FAHP–RST–TOPSIS paradigm helps IT decision-makers to choose virtualized solutions that meet green IT and sustainable development goals. Life cycle assessment data, carbon footprint indicators, and real-time dashboard monitoring may be included to improve sustainability intelligence in virtualized environments.

5. Conclusions

This study presented a hybrid FAHP–RST–TOPSIS framework for sustainable virtualization technology selection. VMware ESXi and Red Hat KVM perform best among the tested options, and performance efficiency, reliability, security, and maintainability are the most important characteristics for sustainable virtualization infrastructures. Fuzzy weighting, rule-based attribute reduction, and ideal-solution ranking handle expert judgment uncertainty and complexity, making the model more transparent and analytically robust than single-method evaluations. The framework’s operationalization into a web-based decision-support dashboard helps organizations guide greener IT procurement, optimize resource utilization, and align data-center decisions with sustainability targets such as SDG 9, SDG 12, and SDG 13.

Multiple implications arise from this study. The research advances hybrid MCDM methodologies by showing how fuzzy logic and rough set theory may be used together to gain sustainability insights from complex ICT environments. It also shows how interpretability-focused methodologies such as RST can improve sustainability assessment frameworks by explaining why certain criteria dominate decision outcomes. The proposed framework does not intend to assert numerical ranking accuracy superiority over conventional MCDM methods through the integration of RST. Rather, it improves interpretability, transparency, and robustness by illustrating that a diminished and more comprehensible set of criteria can be employed to achieve comparable decision outcomes. This property is especially advantageous for professionals who are in search of sustainability assessment models for virtualization technologies that are both dependable and straightforward.

The findings provide IT managers, infrastructure planners, and sustainability officers with an organized and replicable strategy for evaluating hypervisor choices and improving digital infrastructure sustainability. The dashboard lets practitioners standardize evaluations, justify virtualization decisions, and include sustainability into IT governance procedures. This study highlights how efficient virtualization technologies reduce energy consumption, carbon emissions, and hardware dependency, and provides organizations with actionable insights for environmentally responsible digital transformation.

This study has various drawbacks. The review uses a restricted number of expert judgments to demonstrate the concept, which may not cover all perspectives across organizational or industry contexts. ISO/IEC 25010 and sustainability priorities form the criteria, but lifetime carbon footprint, embodied energy, and e-waste reduction could strengthen the analysis. Although effective, the RST discretization approach compresses continuous sustainability performance into category levels, which may lose minor information. This study only examines a range of virtualization options; future research could incorporate containerization, cloud orchestration, and edge computing. The integration of real-time operational data, carbon accounting models, or machine learning-based prediction could improve framework decision support. Virtualization research focused on performance or energy indicators without a sustainability assessment approach. The results show how the FAHP, RST, and TOPSIS methods expose the most influential variables and generate a transparent sustainability score, validating the necessity for a holistic, multi-method approach that overcomes single-dimensional evaluations. The suggested methodology is interpretable and applicable; however, it was tested with four virtualization technologies and five experts. Future research may use larger expert panels and real-time operational indicators. Expert judgment is suited for qualitative sustainability assessment, but future applications may include objective benchmark data to calibrate expert inputs. FAHP weighting, RST redundancy analysis, and TOPSIS ranking can improve robustness and generalizability by combining such data with subjective assessments. The proposed framework tests four common virtualization technologies for practicality; however, the FAHP–RST–TOPSIS framework is not virtualization-specific. The methodologically generic approach can be applied to different technical domains, such as cloud service selection, energy systems, cybersecurity solutions, and smart infrastructure, by redefining the evaluation criteria and alternatives. The FAHP allows domain-specific weighting, RST analyzes criterion redundancy and dependency, and the TOPSIS ranks alternatives. That the framework is general beyond the case study is shown by its adaptability. The suggested FAHP–RST–TOPSIS paradigm involves expert time and cognitive effort, especially during FAHP pairwise comparisons, which may introduce learning and elicitation costs in real decision-making situations. In businesses without MCDM experience, practitioners may also struggle with methodological familiarity, data preparation, and result interpretation. The framework uses a web-based decision-support dashboard to automate calculations, standardize input formats, and offer immediate rating feedback to overcome these challenges. Repeated use and predefined evaluation templates should save expert time and reduce the learning burden. Future research may simplify elicitation approaches or partially automate expert engagement using benchmark data.

This study provides a complete, scalable decision-support solution that advances methodological innovation, IT governance, and sustainable systems design. The hybrid FAHP–RST–TOPSIS technique and dashboard provide a replicable platform for future sustainable IT evaluations and useful advice for enterprises seeking to improve their virtualized infrastructures’ environmental performance.