Abstract

This study investigates the apparent surface-active and emulsifying behaviour of raw Albizia amara (AA) powder suspended in water, reflecting its traditional mode of use. AA suspensions (0.1–1% w/v) were prepared without extraction and evaluated for apparent surface tension, droplet size distribution, emulsification capacity, and emulsion stability. Increasing AA concentration reduced apparent surface tension from 57.13 ± 2.17 mN/m to 48.9 ± 0.06 mN/m, plateauing at higher concentrations. Both blending and high-shear mixing produced oil-in-water emulsions. Blending generated smaller initial droplets (1–10 µm), whilst high-shear mixing produced more uniform distributions (d50 = 31.23 ± 0.95 µm). Emulsion capacity and stability increased with AA concentration, reaching 95.19 ± 3.39% and 89.81 ± 0.02% at 0.8% AA. As the system contains undissolved plant material, all measurements represent the apparent behaviour of a heterogeneous suspension. The specific molecular contributors to surface activity cannot be identified within this study. These findings provide a baseline physicochemical assessment of raw AA powder and support future work involving extraction, purification, and chemical characterisation to establish the mechanisms underlying its surface-active properties.

1. Introduction

Surfactants are amphiphilic molecules capable of reducing the surface tension between two immiscible phases [1] playing a critical role in emulsification, foaming, and cleaning applications. The global surfactant market size is projected to be 18.85 million tonnes in 2025 with an expected increase to 22.18 million tonnes by 2030 [2]. Synthetic surfactants such as sodium lauryl sulphate (SLS) and sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS) are widely used in personal care and household products, including soaps, detergents, shampoos, creams, and serums [3]. However, their low biodegradability has raised environmental concerns, contributing to soil and marine pollution [4,5,6]. With over 15 million tonnes of surfactants used annually and approximately 60% entering aquatic ecosystems, there is growing pressure to transition toward sustainable, plant-based alternatives [7,8,9]. Plant-derived materials are widely reported in the literature to be biodegradable, although this study does not evaluate biodegradability or environmental performance directly [10]. One promising candidate is Albizia amara (AA), commonly known as arappu, a deciduous plant, native to the southern part of Africa and southern India, growing mainly in arid regions [11]. The dried leaf powder of AA is traditionally used as a natural hair cleanser and is known to contain surface-active compounds. Albizia species such as Albizia adianthifolia, Albizia zygia, Albizia julibrissin, Albizzia anthelmintica, Albizia lebbeck, and Albizia procera are widely reported to contain triterpenoid saponins and related glycosides in various tissues and extracts [12,13]. These constituents can display surface activity and have been implicated as natural emulsifiers in other botanical systems. While beyond the scope of the present study, isolation and quantification of these constituents in AA are underway and will be presented in a separate publication. Phytochemical screening and gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS) analyses have confirmed the presence of saponins in both aqueous and ethanolic extracts of AA [11,14,15,16,17]. Saponins are amphiphilic molecules that produce soap-like foams when agitated in water [18] owing to their structural composition: a hydrophilic glycone region composed of sugar chains and a lipophilic aglycone moiety, typically a steroid or triterpenoid [19,20]. This study evaluates raw Albizia amara leaf powder in water, rather than purified or isolated surfactants. All measurements therefore reflect the apparent behaviour of a heterogeneous suspension that may contain both insoluble particles and soluble constituents. Mechanistic interpretation is necessarily limited, and results should be considered an initial screening of practical performance rather than proof of specific molecular mechanisms.

Despite its traditional use, AA has not been widely incorporated into commercial personal care formulations. While previous studies have investigated its anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties [21,22], there is a lack of research on its emulsifying and surface-active behaviour in unprocessed, powdered form.

This study aims to evaluate the feasibility of using raw AA powder suspended in water as a plant-derived surface-active material, without prior extraction. Specifically, the research focuses on assessing the apparent surface tension reduction, oil-in-water emulsion particle size, and identifying the most effective method for preparing uniform and stable AA suspensions. The findings will contribute to understanding the emulsifying potential of AA and its suitability as a natural alternative to synthetic surfactants.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. AA Suspension Preparation and Thermal Stability Assessment

Leaves of Albizia amara were dried and ground into a fine powder. Initial dispersion attempts using a magnetic stirrer proved ineffective due to the hydrophobic nature of the plant material. In this study, AA concentration is expressed as a mass percentage relative to the total suspension volume.

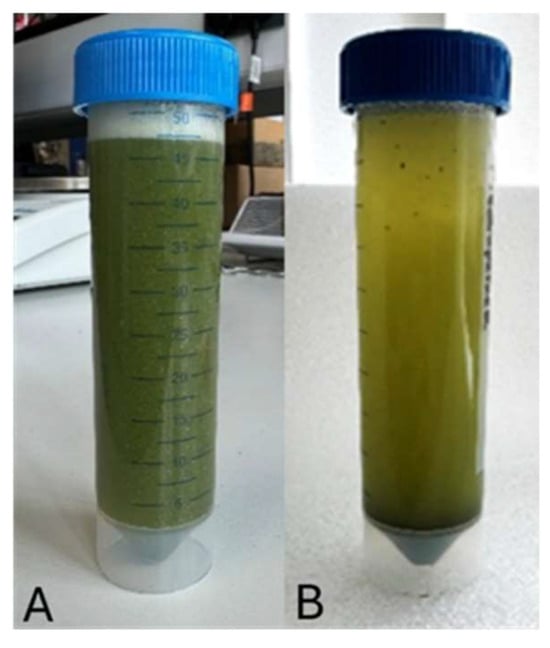

Suspensions were prepared using a blender (Morphy Richards Compact Blender 403060 (1000 W), Morphy Richards, Mexborough, UK). A 0.1% AA suspension was blended at setting 1 for 30 s. The resulting mixture appeared visually homogeneous (Figure 1A), with particles evenly distributed throughout. However, upon standing, sedimentation of powder particles was observed (Figure 1B). Gentle agitation restored the suspension to its original uniform state.

Figure 1.

Suspended Albizia amara in water. (A) Homogeneous suspension, (B) Powder particles sediment at the bottom after left to stand.

This procedure was repeated for AA concentrations of 0.2%, 0.4%, 0.6%, 0.8%, and 1%. To assess thermal stability, one set of suspensions was stored at 4 °C (refrigerated), while another was kept at room temperature (RT).

All mixing and homogenisation steps were performed at ambient temperature (≈21 °C), and no additional heating was applied.

2.2. AA Suspension Stability

2.2.1. pH and Sensory Evaluation

The pH of AA suspensions stored under both conditions was measured at five time points: fresh, 24 h, 1 week, 2 weeks, and 4 weeks. Measurements were performed using a pH metre (ThermoScientific Orion Star A211, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Sensory observations, including changes in colour, odour, and signs of degradation were recorded. For each condition, three replicate suspensions were prepared to ensure statistical reliability.

2.2.2. Particle Size Distribution

Particle size analysis was conducted using a Mastersizer (Malvern Mastersizer 3000, Malvern Panalytical, Malvern, UK) equipped with a Hydro SM disperser (IKA Works, Staufen, Germany) designed for measuring samples in non-aqueous dispersants where solvent usage needs to be minimized), employing Multi-Angle Dynamic Light Scattering (MADLS). This technique estimates particle size based on Brownian motion across multiple laser scattering angles. Volume distribution was selected over intensity distribution to provide a more accurate representation of particle proportions, particularly relevant for suspension and emulsion systems. The instrument was configured to perform 10 measurements at 10 s intervals, and the average particle size distribution was calculated automatically.

2.3. Apparent Surface Tension Measurement

The AA suspensions contained undissolved leaf particles and colloidal material, which prevented the formation of a clean and well-defined liquid interface during pendant-drop measurements. For this reason, the values obtained represent apparent surface tension rather than true equilibrium surface tension. In heterogeneous or turbid systems, suspended solids can distort the drop profile, interfere with optical edge detection, and hinder attainment of interfacial equilibrium. The use of the term “apparent” in such cases is consistent with established surface and colloid science practice and is recommended in tensiometry guidance for dispersions and suspensions (e.g., KRÜSS Technical Note TN31405; Adamson & Gast, Physical Chemistry of Surfaces; Hiemenz & Rajagopalan, Principles of Colloid and Surface Chemistry).

Apparent surface tension of AA powder suspensions was measured with a tensiometer using the pendant drop method (KRÜSS DAS100 Series, KraussMaffei, München, Germany). Each sample underwent 120 individual measurements at 2 s intervals. The surrounding phase was set to air, and the sample density was assumed to be 1 g/cm3, approximating water due to the high-water content of the suspension (>99%).

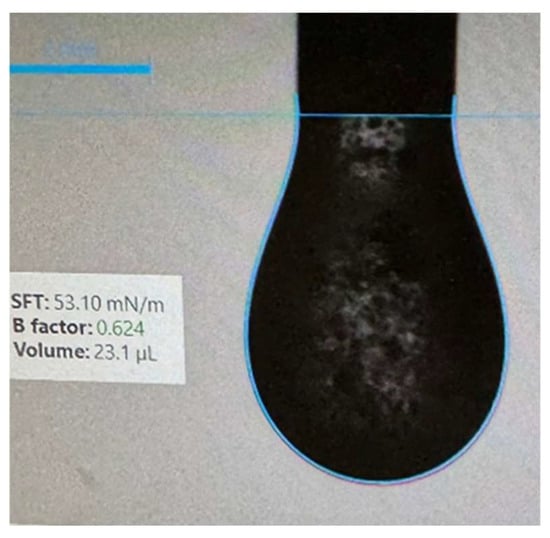

Measurements were conducted in a low-disturbance environment to minimize droplet instability caused by vibration or movement, particularly given the presence of suspended powder particles (Figure 2). A gas-tight syringe was used to extract the sample. Initially, the supernatant layer formed after sedimentation was tested. Subsequently, the suspension was homogenized and remeasured to obtain a representative apparent surface tension value for the entire sample.

Figure 2.

Suspended AA powder particles present in pendent droplet for apparent surface tension measurement.

2.4. Emulsification—Oil-in-Water Emulsion

AA suspensions ranging from 0.1% to 1% were used to prepare oil-in-water emulsions via two methods: blending and high shear mixing. For blending, 95 mL of AA suspension was combined with 5 mL of sunflower oil and processed using a blender (Morphy Richards Compact Blender (setting 1.30 s)). For high shear mixing, the same mixture was blended using a homogeniser mixer (Silverson L5M rotor-stator mixer (Silverson Machines Ltd., Chesham, UK) equipped with a General-Purpose Disintegrating Head) at 5000 rpm for 5 min.

To prevent creaming, emulsions were immediately analysed for droplet size using a Mastersizer (Malvern Mastersizer 3000) equipped with a Hydro SM disperser, following the same MADLS settings as previously described. Microscopic analysis was performed using a 10× objective lens, and droplet sizes were quantified using NIH ImageJ 1.54 software. At least 60 droplets per sample were measured, and pixel values were calibrated to micrometres (µm) using a graticule. Both emulsification methods were applied across AA concentrations of 0.2%, 0.4%, 0.6%, 0.8%, and 1%.

2.5. Emulsion Capacity (EC) and Emulsion Stability (ES)

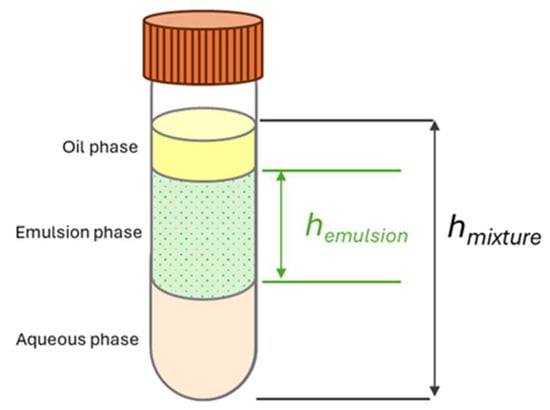

Emulsifying performance was evaluated using two key parameters: emulsion capacity (EC) and emulsion stability (ES) [23,24,25]. 20–22 Equal volumes of AA suspension (50 mL) and sunflower oil (50 mL) were blended using the kitchen blender. Emulsions were transferred into four 15 mL Falcon tubes and stored at room temperature for up to 4 weeks.

To assess stability, samples were centrifuged at 4000× g for 5 min at designated time points: fresh, 1 day, 2 weeks, and 4 weeks. The heights of the separated layers were measured (Figure 3), and EC and ES were calculated using modified equations from Cooper & Goldenberg [26] (1) and (2).

where hemulsion is the height of emulsion phase while hoil is the height of oil phase. hoil was assumed to be half of the total liquid height hmixture. For ES measurement, the height of emulsion phase of the 4-week aged sample, hemulsion,4week was compared to the height of emulsion phase of the fresh sample, hemulsion,fresh. The experiment was repeated three times to obtain an average and standard deviation.

Figure 3.

Schematic of the separated layer after centrifuging.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Stability of Albizia amara Suspension

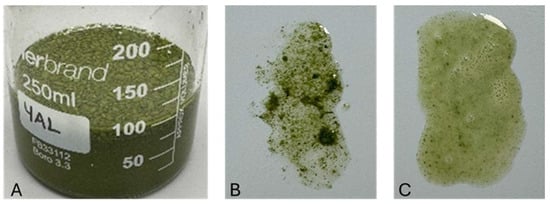

Initial dispersion of AA powder in water using a magnetic stirrer at 700 rpm resulted in poor homogenization, with visible aggregation and flotation of powder particles (Figure 4A,B). According to Gottschalk [27], clumping or flocculation can occur when the surface charges of the powder lead to stronger attractive forces than repulsive ones, resulting in particle aggregation. In addition, variations in density may lead the powder particles to cluster together and rise to the water’s surface instead of sinking to the bottom. In contrast, blending with a high-speed kitchen blender (≈13,000 rpm) produced a more uniform and viscous suspension (Figure 4C). The enhanced dispersion is attributed to the higher shear forces generated during blending, which effectively break down agglomerates and distribute particles evenly throughout the medium.

Figure 4.

(A) Powder aggregated and floated to the surface when mixed with water. (B) Before low shear blending. (C) After high shear blending.

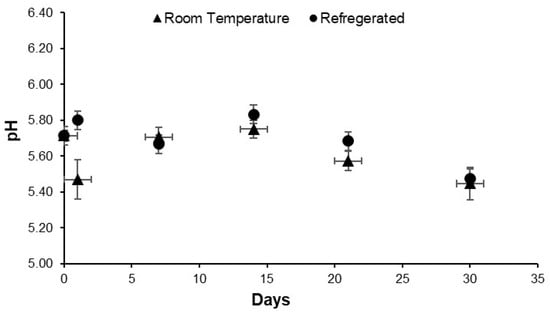

3.2. pH Measurements and Sensory Evaluation

Fresh AA suspensions exhibited a mildly acidic pH of 5.7 at 1% w/w, with higher concentrations expected to yield lower pH values. This acidity is likely due to the presence of organic acids such as tannins, flavonoids, and phenolic compounds, previously identified in ethanolic and acetone extracts of AA [28]. These compounds can contribute to the acidic nature of the suspension. Tannins, in particular have astringent properties, which can influence the overall pH of the suspension [29].

Figure 5 illustrates the pH evolution over a 4-week period under room temperature and refrigerated conditions. Both conditions showed a gradual decline in pH, with more pronounced changes during the final two weeks. Notably, signs of degradation including unpleasant odour were observed at the two-week mark, likely due to microbial or enzymatic activity. Refrigerated samples maintained a slightly higher pH throughout, indicating that lower temperatures help preserve biochemical stability and delay spoilage. Additionally, evidence of particle agglomeration was observed in samples stored for over two months, indicating potential physical degradation. Nevertheless, the continued ability of these aged suspensions to produce foam implies that the surface-active agents retained their functional integrity.

Figure 5.

Effect of storage temperature on the pH of AA suspension.

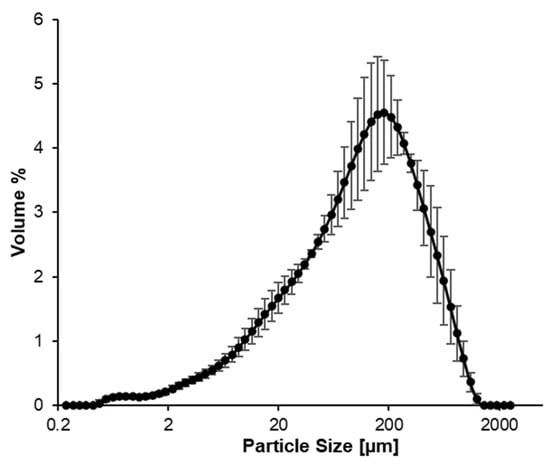

3.3. Particle Size Measurement

The particle size distribution of the fresh leaf suspension (Figure 6) shows the proportion of the total volume against the particle size. The single peak suggests that the suspension has a relatively uniform particle size distribution (monodisperse). The average size was 115.1 ± 3.1 µm.

Figure 6.

Particle size distribution of the fresh AA suspension.

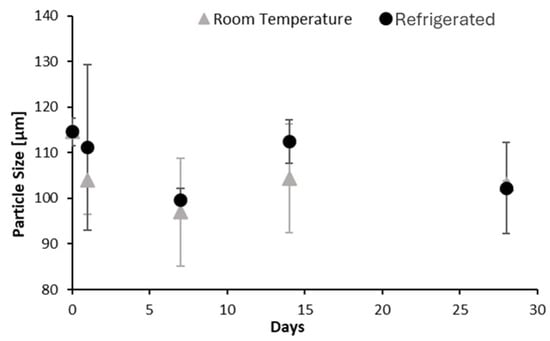

Over time, particle size varied depending on storage conditions. As shown in Figure 7, suspensions stored at room temperature displayed greater variability and wider error bars, suggesting increased aggregation or sedimentation. In contrast, refrigerated samples showed narrower error bars and more consistent particle sizes, likely due to reduced Brownian motion [30] and lower kinetic energy, which minimize particle collisions and aggregation.

Figure 7.

Effect of storage temperature on the size distribution of AA suspension.

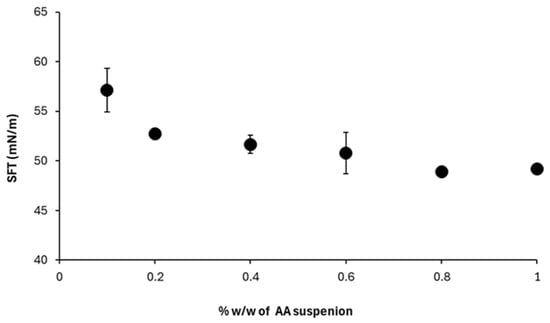

3.4. Apparent Surface Tension

An ideal surfactant needs to effectively reduce apparent surface tension [31] as it is a crucial factor to the initial morphology of emulsions, such as the particle distribution of droplets, as well as emulsion stability [32]. The relationship between AA concentration and apparent surface tension was investigated using the pendant drop method. Measurements were taken from both the supernatant layer and the homogenized suspension to ensure representative data.

3.4.1. Apparent Surface Tension of AA Suspension vs. AA Mass Concentration

Increasing AA concentration from 0.1% to 0.8% reduced the apparent surface tension from 57.13 ± 2.17 mN/m to 48.9 ± 0.06 mN/m, after which an apparent plateau was observed (Figure 8). Since the samples are heterogeneous suspensions, this plateau cannot be interpreted as a true CMC. Instead, it indicates that additional AA powder beyond this range does not further reduce the measured apparent surface tension under the present conditions.

Figure 8.

Apparent Surface tension of AA suspensions at varying concentrations.

These observations are consistent with the presence of surface-active species in the suspension. While adsorption of soluble constituents at the interface may contribute, confirmation requires extract-based studies with chemical identification and interfacial measurements.

For context, recorded SDS and Tween 20 surface tension values were approximately 25.8 ± 1.91 mN/m and 40.5 ± 1.11 mN/m respectively, aligning well with previously reported data [33,34,35,36,37,38]. These values are provided purely as numerical benchmarks.

The reported values represent the apparent surface tension of a heterogeneous, unfiltered suspension. Undissolved particles can affect pendant-drop stability, optical edge detection, and sampling accuracy, especially when phase separation occurs. Although rheological data were not collected, this will be addressed in future studies to better understand the flow behaviour and viscosity changes during processing. To more accurately characterise the contribution of soluble surface-active constituents, future work should use filtered or extract-based samples, temperature-controlled measurements, and methods suited for turbid systems, such as dynamic surface tension analysis.

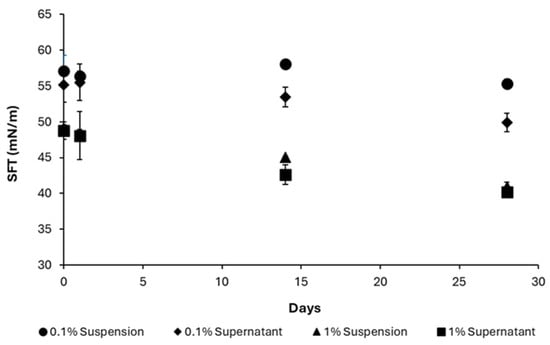

3.4.2. Stability of Apparent Surface Tension of AA Suspension

The temporal variation in apparent surface tension over a 28-day period for both AA suspensions and their corresponding supernatant layers at concentrations of 0.1% and 1% (Figure 9). A progressive decline in apparent surface tension was observed across all samples. Specifically, the apparent surface tension of the 0.1% AA suspension decreased from 57.13 ± 2.17 mN/m to 55.35 ± 0.64 mN/m, while the 1% AA suspension showed a more pronounced reduction from 49.17 ± 0.36 mN/m to 40.95 ± 0.64 mN/m over the same period. Notably, the supernatant layers exhibited greater apparent surface tension reduction than the suspensions, particularly at 0.1%, where values declined from 55.19 ± 2.44 mN/m to 49.90 ± 1.33 mN/m.

Figure 9.

Apparent surface tension of AA suspensions and supernatant at 0.1 and 1%.

This disparity between suspension and supernatant may be attributed to the release of surface-active compounds, such as saponins, from the plant material into the aqueous phase, or to the presence of fine particulate matter within the supernatant. However, in the absence of particle size characterization, the contribution of colloidal particles cannot be conclusively excluded. Future studies should incorporate filtration or centrifugation techniques to effectively distinguish dissolved surface-active molecules from residual particulates, thereby clarifying the origin of the observed surface activity.

3.5. AA Emulsion

3.5.1. Emulsification Methods

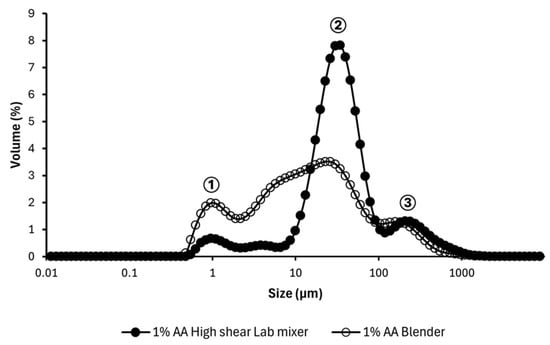

The effectiveness of two emulsification techniques—blending and high shear mixing was evaluated using a 1% AA suspension to produce oil-in-water emulsions. Droplet size distributions resulting from both methods are compared in Figure 10, which shows three primary peaks.

Figure 10.

Particle size distribution of 1% AA emulsion prepared using two blending methods. Size ranges consist of ① ≤1 µm, ② 1< x < 100 µm, ③ >100 µm.

Emulsions prepared with the blender exhibited smaller droplet sizes, predominantly within the 1–10 µm range. In contrast, those produced using the high shear lab mixer showed a dominant peak in the 30–40 µm range, with a median droplet diameter of d50 = 31.23 ± 0.95 µm. This variation in droplet size may be attributed to the more intense shear forces generated by the blender, which facilitate finer dispersion of the oil phase. The high shear mixer yielded a more uniform droplet size distribution, as evidenced by the narrow and sharp peak. Similar distribution profiles have been reported by other studies [39,40,41] when using comparable high shear mixing equipment, likely due to the controlled shear and turbulence that promote consistent emulsification.

As noted earlier, AA powder suspended in water has a D50 of 115.1 ± 3.1 µm, suggesting that peaks above 100 µm in Figure 10 are attributable to undissolved plant powder. Peaks between 1 µm and 90 µm are likely representative of emulsion droplets, with the smallest peak near 1 µm corresponding to microemulsion droplets.

Although droplets near the 1 µm range were observed, these systems cannot be classified as microemulsions. The AA suspensions are heterogeneous and unfiltered, and creaming observed within minutes confirms that the system is not thermodynamically stable. The peak near 1 µm likely reflects fine droplets or particulates rather than true microemulsion structures. Creaming results from density differences between the oil and aqueous phases during prolonged standing [42] necessitating immediate measurement post-emulsification.

The average particle size of the AA powder (≈115.1 µm) is substantially larger than the average oil droplet size (≈31.23 µm), indicating that large-particle adsorption alone is unlikely to explain stabilization. However, contributions from finer particulates or soluble constituents released from the plant material cannot be excluded.

3.5.2. Oil-in-Water Emulsion Droplet Size vs. AA Suspension Amount

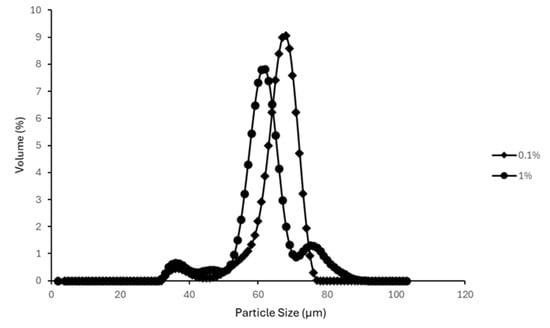

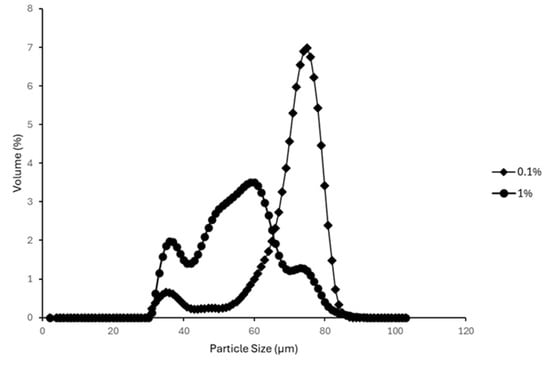

The average particle size distributions of emulsions prepared using a high shear lab mixer and a blender are presented in Figure 11 and Figure 12. Emulsions formulated with 0.1% and 1% AA mass concentrations were selected to represent low and high surfactant conditions, respectively.

Figure 11.

Effect of AA concentration on particle size distribution of emulsions prepared with a High Shear Mixer.

Figure 12.

Effect of AA concentration on particle size distribution of emulsions prepared with a Blender.

Overall, higher AA concentrations were associated with smaller mean droplet sizes. This trend aligns with findings reported in other studies which observed similar effects with increasing surfactant concentrations on emulsion droplet size distribution [43,44]. For emulsions prepared using the high shear lab mixer (Figure 11), the 1% AA suspension exhibited a dominant, sharp peak at a smaller particle size (D50 = 31.23 ± 0.95 µm) compared to the 0.1% AA suspension (D50 = 61.78 ± 3.06 µm). In the case of blender-prepared emulsions (Figure 12), although a dominant peak was not observed for the 1% AA emulsion, the majority of particles fell within a smaller size range relative to the 0.1% AA emulsion.

Additionally, both methods showed a greater proportion of droplets near the 1 µm range at higher AA concentrations, although these do not represent microemulsions. A higher amount of AA in the suspension was associated with a greater proportion of smaller droplets. Since the system was unfiltered and contains both particulate matter and soluble species, this trend may reflect contributions from fine particles, soluble constituents, or a combination of both.

These findings indicate that increasing AA concentration influences droplet size and distribution under the tested conditions. However, the specific mechanism of stabilization cannot be established from the present data.

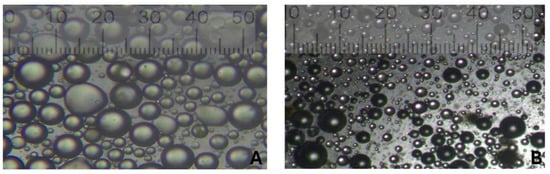

3.6. Microscopy of Oil-in-Water Emulsion

Microscopy images of oil-in-water emulsions prepared using a blender with 0.1% and 1% AA mass concentrations are shown in Figure 13. Visually, the oil droplets in the 0.1% AA emulsion appear larger than those in the 1% AA emulsion. Quantitative analysis confirms this observation, with the 0.1% AA emulsion exhibiting an average droplet diameter of 2.79 ± 1.48 µm, compared to 1.77 ± 0.78 µm for the 1% AA emulsion. The lower standard deviation in the 1% AA emulsion indicates a more uniform droplet size distribution. This reduction in droplet size with higher AA concentration is consistent with the droplet size distributions observed via Mastersizer analysis. These observations describe droplet characteristics but do not identify the specific stabilizing mechanism.

Figure 13.

Microscopy images of oil-in-water emulsions for AA mass concentration of (A) 0.1% and (B) 1% prepared using the blender.

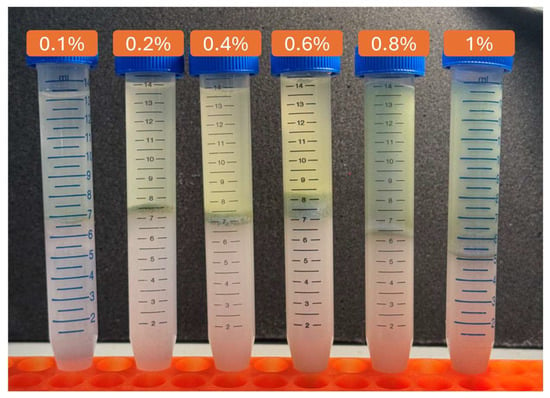

Emulsion capacity typically refers to the ability of an emulsifier to stabilize an emulsion whereas emulsion stability refers to the ability of an emulsion to resist phase separation over time. Centrifuged emulsions prepared with increasing concentrations of AA suspension (0.1% to 1%) are shown in Figure 14. The image illustrates a clear trend in emulsion stability, with higher AA concentrations resulting in more homogeneous and stable emulsions. At lower concentrations, phase separation is more pronounced, indicating insufficient stabilisation. The visual data corroborate the emulsion capacity and stability measurements, indicating that higher AA concentrations influence emulsion appearance and resistance to phase separation under the tested conditions.

Figure 14.

Visual comparison of emulsions at varying AA concentrations after centrifugation.

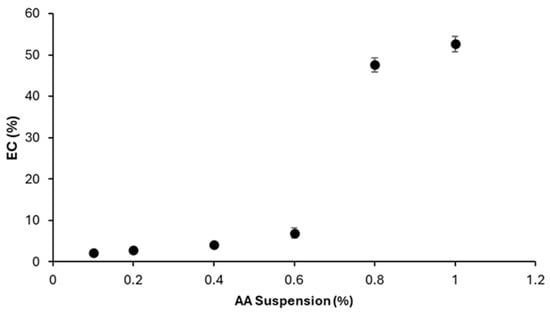

Figure 15 represents the corresponding EC values. A marked increase in EC is observed at concentrations above 0.6%, rising from 13.94 ± 2.38% to 95.19 ± 3.39%.

Figure 15.

Effect of AA suspension concentration on EC.

The sharp increase in EC above 0.6% AA may indicate that higher amounts of the suspension provide more fine particulates or soluble constituents that participate in droplet breakup or interfacial interactions. The specific species responsible for this transition remain unidentified and require further testing using filtered extracts and controlled interfacial measurements.

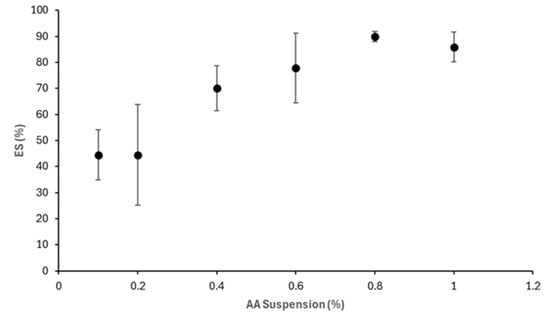

As shown in Figure 16, increasing AA concentration also improves emulsion stability. At concentrations of 0.6% and above, AA suspensions yield more stable emulsions, with ES = 90.32 ± 0.04% achieved at 0.8%. Overall, the observed improvements in droplet uniformity and visual stability at higher AA concentrations suggest promising surface-active behaviour in its raw suspension form.

Figure 16.

Effect of AA suspension concentration on ES.

With growing demand for environmentally friendly surfactants particularly in the cosmetic and personal care sectors, natural alternatives offer significant advantages due to their low toxicity, biodegradability, and cost-effectiveness [45]. Plant-derived bioactive compounds such as saponins possess multifunctional properties, including antibacterial, antioxidant, foaming, and emulsifying activities, making them ideal candidates for sustainable product development [46]. Although plant-derived materials are widely reported to be biodegradable, the present study does not evaluate biodegradability or environmental performance. Continued research into saponin-based systems may contribute meaningfully to reducing reliance on synthetic surfactants and advancing eco-conscious formulation strategies. In future studies, evaluating the zeta potential of the suspension could reveal valuable information about particle surface charge and their likelihood to cluster [47]. This measurement can indicate whether electrostatic repulsion is adequate to maintain particle dispersion. Adjusting the pH of the suspension is one strategy to influence this [48], as pH affects the ionisation of functional groups [49] and performing an optimization of this element may help regulate electrostatic forces and minimize undesired aggregation.

4. Conclusions

The findings of this study show that raw Albizia amara (AA) leaf powder suspensions can contribute meaningfully to surface-active and emulsifying behaviour in simple aqueous systems. Increasing AA concentration was associated with a consistent reduction in apparent surface tension and with the formation of smaller, more uniform emulsion droplets. These trends indicate that AA suspensions exhibit promising surfactant-like behaviour in their traditional, minimally processed form, although the specific molecules responsible have not yet been identified.

AA suspensions also showed strong emulsifying capabilities, evidenced by reduced droplet sizes, high emulsion capacity, and enhanced emulsion stability over time. However, the use of raw powder suspensions presents certain limitations, including challenges in surface tension measurement at higher concentrations and the potential for particle flocculation during prolonged storage. Future studies should aim to isolate and characterise the active components responsible for emulsification. Techniques such as Soxhlet extraction, microwave-assisted extraction, and saponin quantification via the vanillin–sulfuric acid assay could be employed to confirm the role of saponins.

Given that the mean droplet size was considerably smaller than the average AA powder particle size, classical Pickering stabilisation by large particles is unlikely. However, contributions from fine particles or dissolved species remain plausible and warrant further investigation. Exploring AA in combination with complementary plant-derived co-surfactants, assessing zeta potential, and optimising pH could further enhance dispersion stability and overall performance. Collectively, these results establish a strong foundation for the continued development of Albizia amara as a minimally processed, plant-derived material with potential relevance to natural formulation systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.T. and V.P.; methodology, W.F. and Y.S.; validation, A.T., V.P. and A.B.; formal analysis, W.F. and Y.S.; investigation, W.F.; writing—original draft preparation, W.F.; writing—review and editing, A.B., V.P. and Y.S.; visualization, A.B.; supervision, A.T. and V.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication. All authors have consented to this acknowledgement.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AA | Albizia amara |

| MADLS | Multiangle dynamic light scattering |

| RT | Room Temperature |

References

- Aguirre-Ramírez, M.; Silva-Jiménez, H.; Banat, I.M.; Diaz De Rienzo, M.A. Surfactants: Physicochemical interactions with biological macromolecules. Biotechnol. Lett. 2021, 43, 523–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mordor Intelligence. Surfactants Market Size—Industry Report on Share, Growth Trends & Forecasts Analysis (2025–2030). 2025. Available online: https://www.mordorintelligence.com/industry-reports/surfactants-market (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Pradhan, A.; Bhattacharyya, A. Quest for an eco-friendly alternative surfactant: Surface and foam characteristics of natural surfactants. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 150, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asio, J.R.; Garcia, J.S.; Antonatos, C.; Sevilla-Nastor, J.B.; Trinidad, L.C. Sodium lauryl sulfate and its potential impacts on organisms and the environment: A thematic analysis. Emerg. Contam. 2023, 9, 100205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, C.J. Synthetic polymers in the marine environment: A rapidly increasing, long-term threat. Environ. Res. 2008, 108, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suran, M. A planet too rich in fibre: Microfibre pollution may have major consequences on the environment and human health. EMBO Rep. 2018, 19, e46701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, M.S.; Alvarado, J.G.; Zambrano, F.; Marquez, R. Surfactants produced from carbohydrate derivatives: A review of the biobased building blocks used in their synthesis. J. Surfactants Deterg. 2022, 25, 147–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagtode, V.S.; Cardoza, C.; Yasin, H.K.A.; Mali, S.N.; Tambe, S.M.; Roy, P.; Singh, K.; Goel, A.; Amin, P.D.; Thorat, B.R.; et al. Green Surfactants (Biosurfactants): A Petroleum-Free Substitute for Sustainability—Comparison, Applications, Market, and Future Prospects. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 11674–11699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmar, R.; Varsani, V.; Mehta, D.; Dudhagara, D.; Gamit, S.; Nandaniya, N.; Chaun, D.; Vala, A.; Patel, A.; Vyas, S. Biosurfactants production from plant-based saponin: Extraction and innovative applications & sustainable aspect for future commercialization. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2025, 219, 115838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, M.; Miyamoto, T.; Laurens, V.; Lacaille-Dubois, M.-A. Two New Biologically Active Triterpenoidal Saponins Acylated with Salicylic Acid from Albizia adianthifolia. J. Nat. Prod. 2003, 66, 372–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orwa, C.; Mutua, A.; Kindt, R.; Jamnadass, R.; Simons, A. Agroforestree Database: A Tree Reference and Selection Guide Version 4.0. World Agroforestry Centre, Kenya. Available online: https://www.worldagroforestry.org/output/agroforestree-database (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Noté, O.P.; Simo, L.M.; Mbing, J.N.; Guillaume, D.; Muller, C.D.; Pegnyemb, D.E.; Lobstein, A. Structural determination of two new acacic acid-type saponins from the stem barks of Albizia zygia (DC.) J. F. Macbr. Nat. Prod. Res. 2018, 33, 180–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, L.; Pan, G.; Wang, Y.; Song, X.; Gao, X.; Ma, B.; Kang, L. Rapid profiling and identification of triterpe-noid saponins in crude extracts from Albizia julibrissin Durazz. by ultra high-performance liquid chroma-tography coupled with electrospray ionization quadrupole time-of-flight tandem mass spectrometry. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2011, 55, 996–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayakumar, F.A.; Simon, S.E.; Wei, Y.Y.; Woon, Y.P. Characteristic and optimized use of bioactive compounds from gloriosa superba and Albizia amara with apoptotic effect on hepatic and squamous skin carcinoma. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Res. 2018, 9, 1769. [Google Scholar]

- Tamilselvi, S.; Dharani, T.; Padmini, S.; Nivetha, S.; Sangeetha, M.; Das, A.; Balakrishnaraja, R. GC-MS Analysis of Albizia Amara and Phyla Nodiflora Ethanolic Leaf Extracts. Int. J. Recent Technol. Eng. 2018, 7, 466–473. [Google Scholar]

- Sermakkani, M.; Indira Rani, S.; Elakkiya, V.; Kali Devi, K. Studies on preliminary phytochemical, fluorescences and mineral analysis of Albizia amara leaves. World J. Pharm. Life Sci. 2021, 10, 157–163. [Google Scholar]

- Ramya Devi, D.; Sowmiya Lakshna, S.; Veena Parvathi, S.; Vedha Hari, B.N. Investigation of wound healing effect of topical gel of Albizia amara leaves extract. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2018, 119, 400–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushik, G.; Singhal, P.; Chaturvedi, S. Food Processing for increasing consumption: The Case of Legumes. In Food Processing for Increased Quality and Consumption, Handbook of Food Bioengineering; Grumezescu, A.M., Holban, A.M., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Böttger, S.; Hofmann, K.; Melzig, M.F. Saponins can perturb biologic membranes and reduce the surface tension of aqueous solutions: A correlation? Bioorganic Med. Chem. 2012, 20, 2822–2828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oleszek, W.A. Chromatographic determination of plant saponins. J. Chromatogr. A 2002, 967, 147–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, A.; Shah, R.D.; Pallewar, S. Evaluation of anti-inflammatory and analgesic activity of athanolic extracts of Inularacemosa and Albizia amara. Int. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. Res. 2010, 3, 22–27. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, P.S.; Sucheta, S.; Sudarshana, V.D.; Selvamani, P.; Latha, S. Antioxidant activity in some selected Indian medicinal plants. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2010, 7, 1826–1828. [Google Scholar]

- Firebaugh, J.D.; Daubert, C.R. Emulsifying and foaming properties of a derivatized whey protein ingredient. Int. J. Food Prop. 2005, 8, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Tomar, M.; Potkule, J.; Reetu; Punia, S.; Dhakane-Lad, J.; Singh, S.; Dhumal, S.; Pradhan, P.C.; Bhushan, B.; et al. Functional characterization of plant-based protein to determine its quality for food applications. Food Hydrocoll. 2022, 123, 106986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, Q.; Liu, Z.; Zhi, L.; Jiao, B.; Hu, H.; Ma, X.; Agyei, D.; Shi, A. Plant protein-based emulsifiers: Mechanisms, techniques for emulsification enhancement and applications. Food Hydrocoll. 2023, 144, 109008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, D.G.; Goldenberg, B.G. Surface-active agents from two Bacillus species. J. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1987, 53, 224–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gottschalk, U. Overview of Downstream Processing in the Biomanufacturing Industry. In Comprehensive Biotechnology, 2nd ed.; Moo-Young, M., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 669–682. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, K.; Sharma, R.K.; Singh, A. A Detailed pharmacological approach on Albizia amara: A Review. Int. J. Pharm. Res. Appl. 2024, 4, 1658–1664. [Google Scholar]

- Ashok, P.K.; Upadhyaya, K. Tannins are astringent. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. 2012, 3, 45–50. [Google Scholar]

- Lamkin-Kennard, K.A.; Popovic, M.B. Molecular and Cellular Level-Applications in Biotechnology and Medicine Addressing Molecular and Cellular Level. In Biomechatronics; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 201–233. [Google Scholar]

- Ravera, F.; Dziza, K.; Santini, E.; Cristofolini, L.; Liggieri, L. Emulsification and emulsion stability: The role of the interfacial properties. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2021, 288, 102344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Liu, D.; Hu, J. Effect of Surfactant molecular structure on emulsion stability investigated by interfacial dilatational rheology. Polymers 2021, 13, 1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blachechen, L.S.; Silva, J.O.; Barbosa, L.R.S.; Itri, R.; Petri, D.F.S. Hofmeister effects on the colloidal stability of poly(ethylene glycol)-decorated nanoparticles. Colloid Polym. Sci. 2012, 290, 1537–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Dossoki, F.I.; Gomaa, E.A.; Hamza, O.K. Solvation thermodynamic parameters for sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and sodium lauryl ether sulfate (SLES) surfactants in aqueous and alcoholic-aqueous solvents. SN Appl. Sci. 2019, 1, 933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezerra, K.G.O.; Silva, I.G.S.; Almeida, F.C.G.; Rufino, R.D.; Sarubbo, L.A. Plant-derived biosurfactants: Extraction, characteristics and properties for application in cosmetics. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2021, 34, 102036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, A.; Basu, S.; Bandyopadhyay, S.; Chowdhury, R. Optimization of evaporative extraction of natural emulsifier cum surfactant from Sapindus mukorossi—Characterization and cost analysis. Ind. Crops Prod. 2015, 77, 920–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Routray, A.; Das, D.; Parhi, P.K.; Padhy, M.K. Characterization, stabilization, and study of mechanism of coal-water slurry using Sapindous mukorossi as an additive. Energy Sources Part A Recovery Util. Environ. Eff. 2018, 40, 2502–2509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhefian, E.A. Investigation on Some Properties of SDS Solutions. Aust. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2011, 5, 1221–1227. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, S.; Cooke, M.; El-Hamouz, A.; Kowalski, A. Droplet break-up by in-line Silverson rotor–stator mixer. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2011, 66, 2068–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafeiri, I.; Smith, P.; Norton, I.; Spyropoulos, F. Fabrication, characterisation and stability of oil-in-water emulsions stabilised by solid lipid particles: The role of particle characteristics and emulsion microstructure upon Pickering functionality. Food Funct. 2017, 8, 2583–2591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, K.; Hanewald, A.; Vilgis, T.A. Milk Emulsions: Structure and Stability. Foods 2019, 8, 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krog, N. Emulsifiers and Emulsions in Dairy Foods. In Encyclopedia of Dairy Sciences; Roginski, H., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2002; pp. 891–900. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S.; Mahto, V. Emulsification of Indian heavy crude oil using a novel surfactant for pipeline transportation. Pet. Sci. 2017, 14, 372–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laben, A.B.; Kayiem, H.H.A.; Alameen, M.A.; Khan, J.A.; Belhaj, A.F.; Elraies, K.A. Experimental study on the performance of emulsions produced during ASP flooding. J. Pet. Explor. Prod. Technol. 2022, 12, 1797–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banat, M.; Makkar, R.S.; Cameotra, S.S. Potential commercial applications of microbial surfactants. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2000, 53, 495–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bjerk, T.R.; Severino, P.; Jain, S. Biosurfactants: Properties and applications in drug delivery, Biotechnology and Ecotoxicology. Bioengineering 2021, 8, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, G.W.; Gao, P. Emulsions and Microemulsions for Topical and Transdermal Drug Delivery. In Handbook of Non-Invasive Drug Delivery Systems; Kulkarni, V.S., Ed.; Personal Care & Cosmetic Technology; William Andrew Publishing: Boston, MA, USA, 2010; pp. 59–94. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, R.J.; Godínez, L.A.; Robles, I. Waste Resources Utilization for Biosorbent Preparation, Sorption Studies, and Electrocatalytic Applications. In Valorization of Wastes for Sustainable Development; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 395–418. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, F.; Niu, Q.; Lan, Q.; Sun, D. Effect of dispersion pH on the formation and stability of pickering emulsions stabilized by layered double hydroxides particles. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2007, 306, 285–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).