Abstract

This study systematically compares how three counterions (Na+, K+, NH4+) regulate the interfacial properties, foaming behavior, and foam stability of lauroyl glutamate (LG) surfactants, and further examines how added NaCl modifies these properties in the sodium salt (SLG). The three counterions induce only slight variations in surface activity and foam generation. Their influence is more evident in foam stability, with the sodium salt exhibiting enhanced stability across a wider concentration range. For SLG, NaCl addition markedly lowers the critical micelle concentration and induces concentration-dependent changes in foaming behavior: 1% NaCl enhances foam generation, while higher salt levels diminish this effect. Foam stability is strongly affected in the sub-cmc regime, with 3% NaCl producing the most stable foams. Surfactant concentration and salt content are the main factors affecting foam performance.

1. Introduction

Amino acid surfactants possess many favorable features, including high surface activity, good biodegradability, low toxicity, low irritation to human skin, rich and delicate foaming capacity, and notable antimicrobial activities, compared with conventional surfactants [1,2,3,4]. In addition, they exhibit good compatibility when compounded with other surfactants. Consequently, they have found extensive applications in cosmetics, personal care products, cleansing agents, pharmaceuticals, food, and other sectors of the daily chemical industry [5,6,7,8].

Sodium lauroyl glutamate (SLG) is a representative amino acid surfactant derived from the widely available glutamic acid. Owing to its safety, mildness, and low irritation, it meets the criteria of green chemistry and has become increasingly used in the daily chemical industry. Structurally, SLG contains an amide group linking the hydrophobic alkyl chain to the hydrophilic moiety. The hydrophilic group originates from glutamic acid and contains two carboxyl groups. As a result, this dicarboxylate anionic surfactant exhibits distinct interfacial adsorption behavior and self-assembly characteristics in aqueous solutions [9].

Although numerous studies have reported the synthesis and physicochemical properties of SLG [10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17], investigations into its foam properties remain limited [18,19,20,21,22]. To date, no systematic studies have examined the potassium and ammonium salts of lauroyl glutamic acid or their foaming behavior. Moreover, investigations into the influence of inorganic salts, such as sodium chloride, on the interfacial properties and foam performance of lauroyl glutamic acid are also scarce. Given that surfactant foams are widely applied in diverse industrial processes, including fire extinguishing, food processing, mineral flotation, petroleum exploitation, and chemical manufacturing, such studies are of both scientific and practical significance.

To clarify how foams respond to changes in ionic conditions, it is necessary to investigate the influence of counterion identity on surface activity and foaming characteristics. Potassium and ammonium ions, with their distinct hydration and interfacial interaction properties, may alter the foam behavior of amino acid–based surfactants. In addition, inorganic electrolytes such as sodium chloride can further regulate the interfacial adsorption and foam performance of lauroyl glutamic acid. Accordingly, the present work systematically examines the surface activity and foam behavior of lauroyl glutamate salts with sodium, potassium, and ammonium counterions (abbreviated as SLG, PLG, and ALG, respectively), and evaluates the effect of NaCl concentration on sodium lauroyl glutamate. The structures of these dicarboxyl-containing anionic amino acid surfactants are shown in Scheme 1.

Scheme 1.

Structure of lauroyl glutamate (LG) surfactant.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Lauroyl glutamic acid (95%) was purchased from Changsha Puji Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Changsha, China). Sodium hydroxide, potassium hydroxide, ammonia, sodium chloride, disodium hydrogen phosphate, and sodium dihydrogen phosphate were purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Beijing Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). Petroleum ether was purchased from Beijing InnoChem Science & Technology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China).

Commercially obtained lauroyl glutamic acid was washed with petroleum ether three times and then recrystallized in anhydrous methanol to obtain the pure N-lauroyl glutamic acid. Its structure and purity were confirmed by 1H NMR, 13C NMR, and ESI-MS, and the corresponding spectra have been included in the Supporting Information (Figures S1–S3). The N-lauroyl glutamic acid was dissolved in absolute ethanol, and an equimolar amount of sodium hydroxide (potassium hydroxide, ammonia) in ethanol solution was added. After cooling, the sodium N-lauroyl glutamate (potassium N-lauroyl glutamate, ammonium N-lauroyl glutamate) white precipitate was obtained.

All other reagents are analytical grade and were used without further purification. All solutions were prepared with deionized water (specific resistivity is 18.25 MΩ·cm).

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Preparation of the Aqueous Solutions

The concentrated stock solutions of the surfactant were prepared by dissolving appropriate amounts of the surfactant in 10 mmol·L−1 phosphate buffer (pH = 7.00 ± 0.05), prepared from NaH2PO4 and Na2HPO4. For surface tension and foam measurements, the samples containing different concentrations were prepared by diluting concentrated stock solutions of the surfactants with the above-mentioned phosphate buffer. After preparation, the samples were kept in sealed bottles.

Brine stock solutions were prepared by dissolving appropriate amounts of sodium chloride in the same phosphate buffer. Samples with controlled ionic strength were prepared by mixing appropriate volumes of the brine stock solution and surfactant stock solutions in the phosphate buffer to obtain varying salt concentrations.

All samples in this study shared the same buffered background. As the phosphate buffer is composed of sodium salts, it introduces a uniform and low-level background concentration of Na+ into all solutions. The pH of all solutions was maintained at 7.00 ± 0.05 under 25 °C, stabilized by the phosphate buffer and verified using a METTLER TOLEDO SevenExcellence S470 (Mettler Toledo, Schwerzenbach, Zürich, Switzerland) benchtop pH/Conductivity meter.

2.2.2. Surface Tension Measurements

Surface tension was measured by using the Wilhelmy plate method at 25.0 ± 0.1 °C with a DCAT21 tensiometer (Dataphysics, Filderstadt, Baden-Württemberg, Germany), operating with a standard deviation of 0.1 mN·m−1. Each sample was measured at least three times, yielding standard deviations below 0.3 mN·m−1; the values reported in the figures represent the corresponding means. The pH value of the measured solution was controlled at 7.00 ± 0.05.

2.2.3. Foam Measurements

Foam performance of the surfactant solutions was analyzed by using the FoamScan instrument (Teclis-IT Concept, Lyon, Rhône, France). The electrodes in the instrument were used to calibrate the conductivity. A pair of vertical electrodes at the base of the measuring column detected the total liquid volume by conductivity, while multiple circular electrodes along the column measured foam conductivity at different heights. The measurement method refers to reference [23]. A 60 mL solution was divided into three portions and injected into the sample column (the height was 300 mm, and the inner diameter was 35 mm). Each injection volume was 20 mL. Nitrogen gas was blown into the liquid to form foam at a flow rate of 80 mL·min−1. The time required for the foam volume to reach 150 mL was used to characterize foamability. When the foam volume of the samples reached 150 mL, aeration was stopped. After 1000 s, the foam volume was recorded to characterize the foam stability of the sample. All testing processes were carried out at a constant temperature of 25 °C. The images were taken using the built-in optical system of the FoamScan analyzer. The foam was observed through the second prism on the side of the foam measuring column, and the camera was positioned at a vertical height of 11.5 cm to receive the refracted image. All tests were conducted at least three times, and the quoted results are the average of three measurements.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Surface Activity

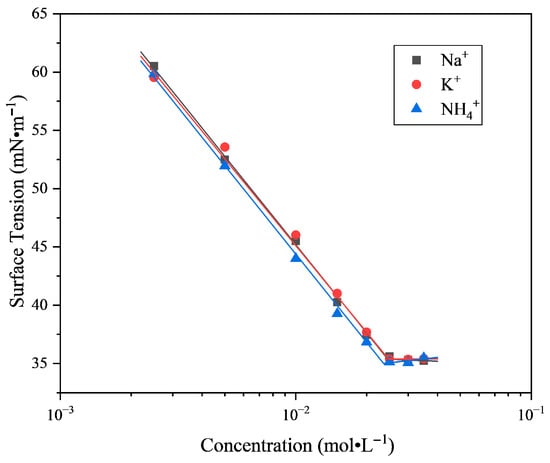

The equilibrium surface tension of aqueous solutions of the LG surfactant with different counter ions was measured. The aqueous surfactant solutions were prepared with phosphate-buffered solution. The curves of surface tension versus concentration of the LG surfactant are shown in Figure 1. The cmc is taken at the intersection of the linear portions of the plots. The minimum surface tension () is acquired by determining the corresponding surface tension at the cmc.

Figure 1.

Plots of surface tension versus concentration of LG with different counter ions. Surface tension was measured by using the plate method at 25.0 °C and pH = 7.00 ± 0.05.

The surface excess () and area occupied by the surfactant molecules at the air/water interface () are obtained from the slope of the surface tension versus log concentration plots (Figure 1) by using the approximate form of the Gibbs adsorption isotherm equations (Equations (1) and (2)).

where R is the universal gas constant (8.314 J·mol−1·K−1), NA is Avogadro’s number (6.022 × 1023), T is the absolute temperature (K), is in mol·cm−2, and is in nm2·molecule−1. n is assumed to be 3 for ionic surfactants containing two carboxyl groups [19], whereas under conditions where a large and constant concentration of sodium chloride is present, n is set to 1 [24].

It can be seen from Figure 1 and Table 1 that the values of and cmc of the LG surfactants vary only slightly among the different counter ions. At pH = 7, the surface tension value of SLG reaches 35.01 mN·m−1 in 2.46 × 10−2 mol·L−1, that of PLG reaches 35.37 mN·m−1 in 2.48 × 10−2 mol·L−1, and that of ALG reaches 35.01 mN·m−1 in 2.36 × 10−2 mol·L−1. The values of and cmc for SLG and PLG are very close, indicating that Na+ and K+ exert similar influences on the interfacial behavior of lauroyl glutamate.

Table 1.

The aqueous surface activity of the LG surfactant with different counter ions and NaCl.

In contrast, ALG shows slightly lower and cmc values. The tetrahedral structure of NH4+ may affect the arrangement of water molecules. NH4+ is more likely to accumulate at the air/water interface compared to Na+ and K+. NH4+ with N-H bonds can form intermolecular hydrogen bonds with the lauroyl glutamate anion head group, which helps to reduce charge repulsion between head groups and thus lowers the surface tension and cmc [25,26]. Overall, the cmc and values of the three LG surfactants are very similar, indicating that their surface activities are essentially identical within experimental uncertainty.

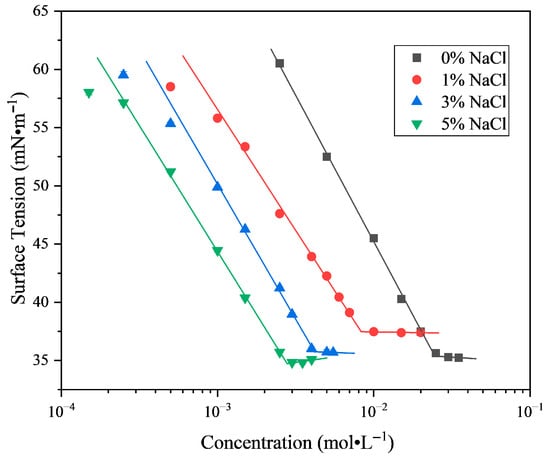

It can be seen from Figure 2 and Table 1 that the values of and cmc of the SLG surfactant decrease with increasing NaCl concentration (the concentration of salt given in the text refers to the mass percentage). The surface tension value of the SLG surfactant solution containing 1% NaCl reaches 37.48 mN·m−1 in 8.29 × 10−3 mol·L−1, that of SLG containing 3% NaCl reaches 35.75 mN·m−1 in 4.19 × 10−3 mol·L−1, and that of SLG containing 5% NaCl reaches 34.73 mN·m−1 in 2.79 × 10−3 mol·L−1. With the addition of salt, the effective negative charge of surfactant molecules decreases and the repulsive force between molecules at the interface decreases. The surfactant molecules are arranged more closely at the interface. At the same time, the addition of NaCl reduces the electrostatic repulsion between the surfactant head groups, promoting easier formation of micelles. The surface activity trend of SLG containing NaCl is consistent with that of typical ionic surfactants [27,28].

Figure 2.

Plots of surface tension versus concentration of SLG. The added NaCl concentrations are 0%, 1%, 3%, and 5%. Surface tension was measured by using the plate method at 25.0 °C and pH = 7.00 ± 0.05.

LG surfactants mainly exist as the dianion at pH = 7 [18]. Variations in electrolyte concentration modify the interfacial electrostatic potential, which, in turn, affects the dissociation degree of ionizable surface groups [29]. Additionally, many disodium carboxylates at the interface are protonated to form monosodium carboxylates. The charges of molecules decrease and several intermolecular hydrogen bonds are formed at the interface [19]. The tightly arranged surfactant molecules on the interface result in a lower surface tension of the LG aqueous solution without salt addition. The addition of NaCl induces the conversion of interfacial monosodium carboxylates into disodium carboxylates, which disrupts hydrogen bonding and enhances intermolecular repulsion; consequently, the surface tension increases. As the NaCl concentration increases further, the electrostatic shielding effect of counter ions compensates for the loss of hydrogen bonding, allowing surfactant molecules at the interface to rearrange tightly, which in turn decreases the surface tension.

In Table 1, the surface excess and areas occupied by the LG surfactant molecules with different counter ions at the air/water interface are almost the same. The influence of three types of counter ions on the adsorption of the LG surfactant is negligible.

When the NaCl content in the system increases, the value of n in the Gibbs adsorption isotherm decreases. In the presence of a large amount of inorganic electrolytes sharing the same counterions with the surfactant ions, the isotherm can be calculated with n = 1 [24]. Under this condition, the calculated surface excess increases and the molecular occupied area () decreases, indicating a higher adsorption density of surfactant molecules at the air/water interface. When the NaCl content reaches 5%, further decreases compared with 3%, suggesting that the interfacial film becomes more stable under stronger electrostatic screening and headgroup dehydration. At the same time, the curve in the pre-cmc region becomes flatter, i.e., decreases. According to Gibbs’ equation, this flatter slope leads to a smaller and consequently a larger calculated molecular occupied area (). It should be noted that this deviation does not necessarily indicate looser interfacial packing. Instead, it reflects the reduced marginal surface-pressure contribution of each molecule under high ionic strength, most likely caused by counterion binding and partial dehydration. Therefore, the increase in at 5% NaCl can be attributed to the diminished efficiency of individual molecules in lowering surface tension, while the continuous decrease in still supports the presence of a compact and ordered interfacial arrangement of LG molecules.

The efficiency of adsorption of the surfactant at the air/water interface can be characterized by the value of pC20. It can be seen from Table 1 that the pC20 values of the LG surfactant with different counter ions are almost the same, indicating the same adsorption efficiency. The pC20 values increase with the increase in sodium chloride concentration. This indicates that SLG more efficiently reduces the surface tension at high salt concentrations.

3.2. Foam Performance

Foamability and foam stability are two important properties of surfactants. The foamability of a surfactant refers to the difficulty with which the surfactant solution produces foam under the action of external conditions. The time taken for the foam volume to reach 150 mL via nitrogen blowing was used to characterize the foamability of the surfactant. The shorter the time, the better the foamability of the surfactant in aqueous solutions.

Foam stability refers to the persistence of foam or the life span of foam after the surfactant produces foam. Foam stability is usually expressed in terms of foam volume at a certain time or the liquid drainage rate in foam. The foam volume at 1000 s was used to characterize the foam stability of the surfactant. The larger the volume, the better the foam stability of the surfactant in aqueous solutions.

Anionic surfactants have different counter ions. There may be inorganic salts in the preparation process or formula of surfactants. These factors will affect the foamability and foam stability of the system.

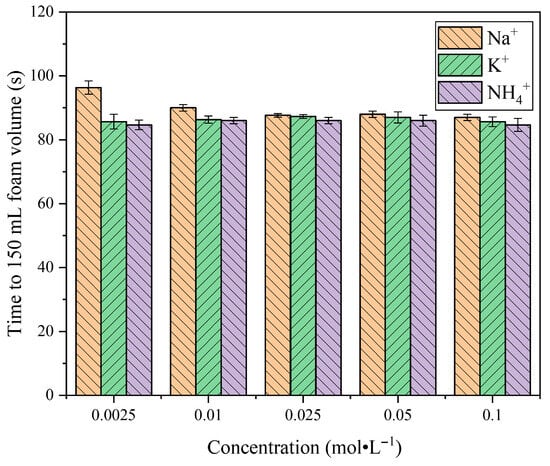

3.2.1. Counterions

The time required to reach 150 mL of foam volume for LG surfactants with different counterions in aqueous solutions at varying concentrations is shown in Figure 3. As shown in Figure 1, the surface tensions of SLG, PLG, and ALG solutions are comparable at the same concentration. Correspondingly, ALG and PLG exhibit almost the same foaming behavior across the examined concentration range. SLG shows a noticeably longer foaming time only at the lowest concentrations, and this deviation diminishes progressively as the concentration increases. Thus, although the equilibrium surface tensions are similar, slight counterion-related differences in dynamic foaming appear only under dilute conditions. This behavior is consistent with the Marangoni effect, whereby surface tension gradients drive interfacial replenishment [30]. In dilute solutions, Na+, due to its stronger hydration and weaker interfacial binding, is less effective than K+ and NH4+ in promoting the rapid adsorption of LG molecules at the interface, thereby reducing the efficiency of stable film formation during foaming. Overall, the foaming behaviors of the three surfactants are largely similar, with ALG and PLG showing comparable performance and SLG exhibiting slightly lower foamability only at the lowest concentrations.

Figure 3.

The foamability of the LG surfactant with different counter ions at different concentrations. The foam is generated via nitrogen blowing. Foaming ability is evaluated according to the time taken to reach 150 mL foam volume at 25.0 °C and pH = 7.00 ± 0.05.

The influence of concentration on foaming behavior differs among the three surfactants. For SLG, foamability is strongly dependent on concentration, especially at low concentrations. As the concentration increases, the foaming time decreases, reflecting improved foamability. This concentration-dependent behavior is consistent with the Gibbs adsorption effect: higher bulk concentrations increase surface excess adsorption and reduce surface tension, thereby accelerating foam formation. In contrast, the foamability of PLG and ALG is only marginally affected by concentration. When the concentration of LG surfactants exceeds 0.025 mol·L−1, the foaming times of all three species converge, suggesting that interfacial adsorption sites approach saturation and the specific influence of counter ions diminishes at higher concentrations.

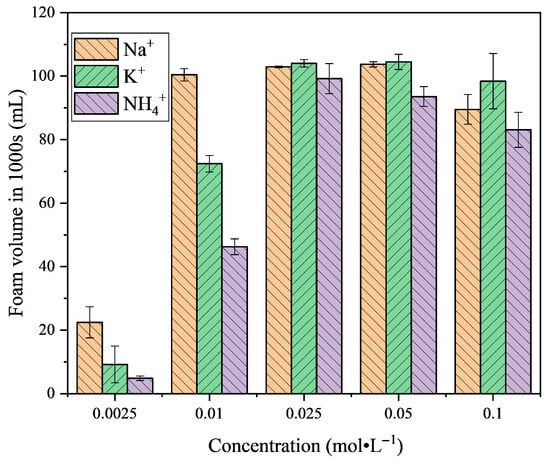

Figure 4 shows the foam volume of LG surfactants with different counterions at 1000 s under various concentrations. The results indicate that both counterion type and concentration exert significant effects on foam stability. At low concentrations (0.0025 and 0.01 mol·L−1), the foam volume with Na+ is much larger than that with K+ and NH4+, and even at 0.01 mol·L−1 the SLG solution exhibits a relatively high foam volume. This trend can be rationalized by the strong hydration of Na+, which sustains an extended electrostatic double layer and enhances the stability of the liquid films, effectively delaying bubble coalescence [31]. In contrast, K+ and NH4+, with weaker hydration and stronger interfacial association, show lower foam stability in the dilute regime.

Figure 4.

The foam volume of the LG surfactant with different counter ions at different concentrations. Foam stability is evaluated according to the foam volume in 1000 s at 25.0 °C and pH = 7.00 ± 0.05.

As the concentration reaches and exceeds the cmc (0.025 mol·L−1), the foam stability with K+ and NH4+ increases significantly. This enhancement arises from the stronger binding of these counterions to the carboxylate headgroups, which promotes denser interfacial adsorption of LG molecules and improves interfacial elasticity. In particular, K+ exhibits the most pronounced stabilizing effect, leading to the highest foam stability in the concentrated regime. Although further increase in concentration (0.05–0.1 mol·L−1) does not result in additional foam growth, the relative order of stability (K+ > Na+ > NH4+) remains consistent [32]. These results suggest that the interplay of counterion hydration and interfacial binding governs the foam stability of LG surfactants across different concentration regimes.

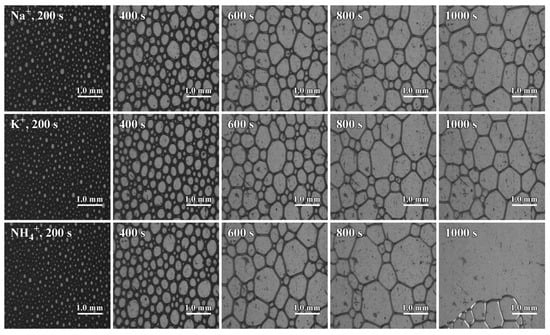

It can be seen from Figure 5 that as time goes on, the liquid volume in the foam gradually decreases, and the bubbles gradually become larger. After more than 600 s, the foam of the SLG surfactant is uniform and stable, while the bubbles of the ALG surfactant increase significantly and rapidly, and the bubbles collapse fast at 1000 s.

Figure 5.

Foam morphology of LG with different counter ions at different times. The concentration of the LG surfactant is 0.01 mol·L−1. The flow rate of nitrogen gas that generates foam is 80 mL·min−1. The foam was recorded through the side prism, with the camera positioned 11.5 cm above the base to capture the refracted image.

The aqueous solution of the ALG surfactant has a larger bubble compared to SLG and PLG surfactants, and the curvature radius of the bubble is larger. Plateau drainage within the liquid film is more pronounced, leading to thinning of the bubble film. Afterwards, the adjacent bubbles undergo coalescence and merging events. Eventually, this results in the transition to dry foam, which then collapses.

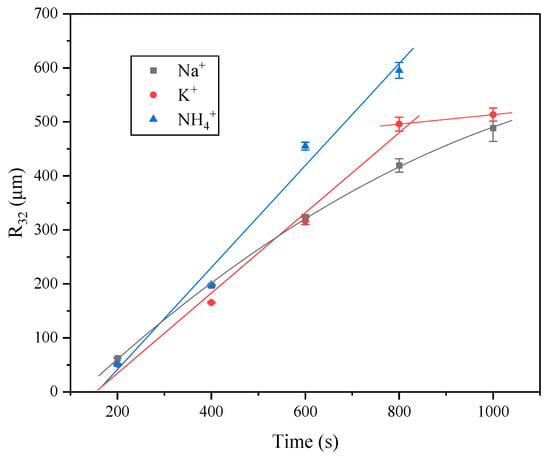

Figure 6 presents the time-dependent evolution of the Sauter mean radius (R32) of foams stabilized by lauroyl glutamate with different counterions (Na+, K+, and NH4+). In the case of Na+, the variation of R32 is well fitted by a quadratic function, where the slope gradually decreases with increasing time. This trend indicates that bubble growth slows down at the later stage, suggesting enhanced resistance to coarsening. For K+, the growth of R32 is approximately linear up to 800 s, followed by a pronounced reduction in slope between 800 and 1000 s, implying a transition in coarsening dynamics. Accordingly, the data were fitted with a segmented linear model, introducing an inflection point at 800 s. In contrast, the NH4+ system follows a linear growth over the measured period with a slope that is steeper than that of K+ in the 0–800 s interval, resulting in significantly larger bubble sizes at equivalent times. These results indicate that the counterion species modulates the kinetics of foam coarsening, with the fastest growth observed for NH4+, an intermediate behavior for K+, and the slowest increase for Na+.

Figure 6.

Bubble size (R32) of LG with different counter ions at different times. The concentration of the LG surfactant is 0.01 mol·L−1. Error bars indicate the variation in mean R32 values from three independent measurements.

The distinct behaviors observed for the three counterions can be attributed to differences in their hydration and specific interactions with the carboxylate headgroups of lauroyl glutamate. Na+, with its strong hydration and weaker binding affinity to the interface, enhances electrostatic repulsion and promotes Marangoni flows, thereby suppressing bubble coarsening in the later stage. K+, which is less hydrated and binds more strongly to the headgroups, initially reduces headgroup repulsion and surface elasticity, leading to faster coarsening in the early stage [25]. However, as the foam becomes drier and interfacial rearrangements occur, the system exhibits improved resistance to bubble growth, reflected by the reduced slope after 800 s. In the case of NH4+, the ability to form ion pairs and hydrogen bonds with carboxylate groups significantly decreases interfacial charge density and weakens surface elasticity, thereby accelerating coarsening throughout the observed period. Consequently, the relative coarsening rates can be ranked as NH4+ > K+ > Na+, which is consistent with the decreasing hydration strength and increasing interfacial binding of the counterions.

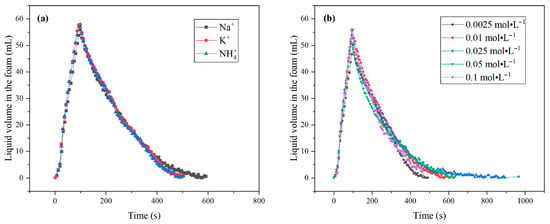

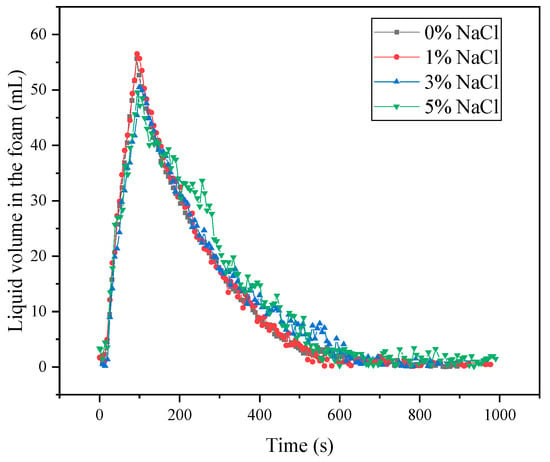

The curves of the water content of the foam liquid film over time are shown in Figure 7. As can be seen from Figure 7a, after 500 s the foam film of SLG retains more water than those of PLG and ALG, and Plateau drainage in the liquid film is slower. The higher water content of foam and better liquid-holding capacity are favorable for the stability of foam. Therefore, the foam stability of SLG is better.

Figure 7.

Liquid volume in the foam of the LG surfactant: (a) LG with different counter ions at a concentration of 0.01 mol·L−1; (b) sodium N-lauroyl glutamate at different concentrations.

As shown in Figure 7b, the concentration has a significant impact on liquid volume in the foam. The drainage rate is very fast at low concentrations. When the concentration reaches the cmc, the liquid volume in the foam is maximum and Plateau drainage in the liquid film is slowest. As the concentration further increases, the liquid volume in the foam decreases. This may be due to drainage caused by gravity.

3.2.2. Inorganic Salts

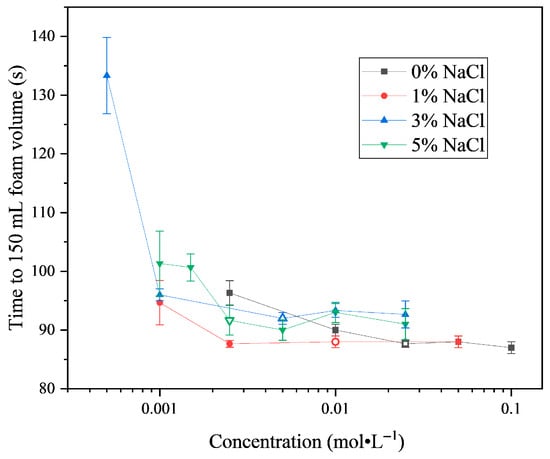

The foaming time of SLG aqueous solutions with different NaCl concentrations is shown in Figure 8. The effect of NaCl on the foaming performance of SLG is clearly concentration dependent. At low SLG concentrations (<0.01 mol·L−1), the addition of NaCl markedly reduces the foaming time, indicating enhanced foaming ability. The most pronounced effect is observed at 1% NaCl, which yields the shortest foaming time. The hollow symbols in Figure 8 represent the foaming times at the cmc concentrations of SLG solutions with different NaCl contents. It is evident that at their respective cmc concentrations, the foaming time with 0% and 1% NaCl is shorter than that with 3% and 5% NaCl, indicating that the foaming ability decreases with increasing salt content. For a given NaCl concentration, however, the foaming performance of SLG solutions shows little further change once the surfactant concentration exceeds the cmc, because the air–water interface is already saturated with surfactant molecules and additional surfactant primarily contributes to micelle formation in the bulk rather than further improving interfacial stabilization [32].

Figure 8.

Foamability of SLG at different NaCl concentrations at 25.0 °C. The surfactant solution is prepared using a buffer solution (pH = 7) containing NaCl. The hollow symbols represent the cmc concentrations of SLG solutions at different NaCl contents.

A closer examination of the data reveals that for SLG solutions containing 1% and 3% NaCl, the foaming performance at the concentration just below the cmc is nearly identical to that at the cmc. In contrast, for solutions containing 0% and 5% NaCl, the foaming performance at the concentration just below the cmc is lower than that at the cmc. This comparison suggests that a small amount of electrolyte promotes adsorption and enhances the foaming performance of dilute SLG solutions. However, as the NaCl concentration increases further, the foaming ability begins to diminish. The weaker performance at 3% compared with 1% NaCl indicates that higher ionic strength shifts the system toward micelle formation at the expense of interfacial adsorption, thereby reducing the efficiency of bubble stabilization. At very high NaCl concentrations (e.g., 5%), this effect becomes more pronounced, and the foaming ability decreases sharply when the SLG concentration is below the cmc. These findings highlight the dual role of electrolytes in regulating adsorption and micellization, which together govern the foaming performance of SLG solutions across different salt concentrations.

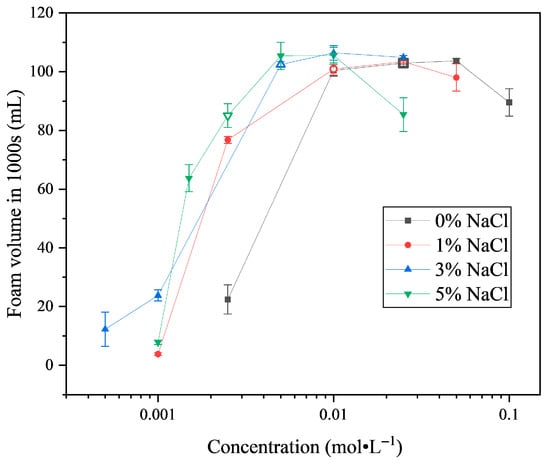

As shown in Figure 9, the foam stability of SLG solutions was measured by the foam volume remaining at 1000 s and shows a strong dependence on both surfactant concentration and added NaCl. With increasing SLG concentration, the residual foam volume rises sharply, reaches a maximum slightly above the cmc, and then decreases. The fact that the maximum stability does not occur exactly at the cmc can be explained by the limited ability of monomers at the cmc to rapidly replenish newly created interfaces during foaming, even though the interface is already saturated with a monolayer of surfactant. At concentrations above the cmc, the presence of excess free monomers and the dynamic exchange between micelles and monomers allow more efficient interfacial replenishment, thereby enhancing the viscoelasticity of the lamellae and improving foam stability. Nevertheless, in the absence of NaCl, foam stability decreases again at high concentrations, which can be attributed to persistent electrostatic repulsion between charged headgroups and the limited efficiency of micelle–monomer exchange, both of which restrict interfacial packing and promote faster film rupture [33].

Figure 9.

The foam volume of SLG at 1000 s at different NaCl concentrations at 25.0 °C. The surfactant solution is prepared using a buffer solution (pH = 7) containing NaCl at different concentrations. The hollow symbols represent the cmc concentrations of SLG solutions at different NaCl contents.

The addition of NaCl markedly improves foam stability at low SLG concentrations by reducing electrostatic repulsion between headgroups and promoting more compact interfacial adsorption [34]. Within the range of 0–3% NaCl, the variation in foam stability at the cmc is consistent with the differences in equilibrium surface tension (). Solutions with lower values, such as 0% and 3% NaCl, exhibit higher foam stability, whereas the 1% NaCl solution, with a slightly higher , shows comparatively weaker stability. This trend is consistent with the Gibbs effect, whereby a lower equilibrium surface tension enhances the restoring forces arising from surface tension gradients, improving the elasticity and stability of the foam films. However, at 5% NaCl, a distinct deviation is observed, and the relationship between and foam stability described above no longer holds. The foam stability at the cmc is significantly lower than that at lower NaCl contents, despite the interfacial saturation of surfactant molecules. This can be attributed to the fact that under such high ionic strength, surfactant molecules preferentially aggregate into micelles rather than remain adsorbed at the interface, thereby reducing the efficiency of interfacial replenishment and weakening foam film stability. Furthermore, at higher SLG concentrations such as 0.025 mol·L−1, the foam stability of the 5% NaCl solution decreases again. In this case, excessive ionic strength induces strong dehydration of the headgroups and compresses the electrical double layer, resulting in fragile lamellae that collapse more rapidly, even though the bulk surfactant concentration is high.

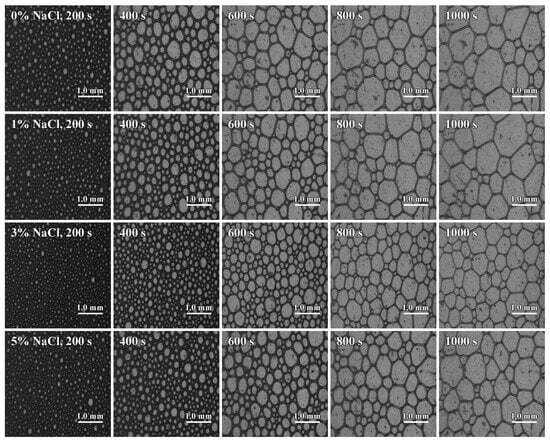

Since the differences in foam stability among the 0.01 mol·L−1 SLG solutions with different NaCl contents are small, the foam evolution can be compared more clearly. Figure 10 shows that, with time, bubbles become fewer and larger, and the liquid-holding capacity of the foam declines. When the NaCl content is 3%, the speed of bubble growth slows down. The bubbles are small in size and large in quantity, resulting in a rich, fine, and more stable foam.

Figure 10.

Foam morphology of SLG with different NaCl concentrations at different times. The concentration of the LG surfactant is 0.01 mol·L−1. The flow rate of nitrogen gas that generates foam is 80 mL·min−1. The foam was recorded through the side prism, with the camera positioned 11.5 cm above the base to capture the refracted image.

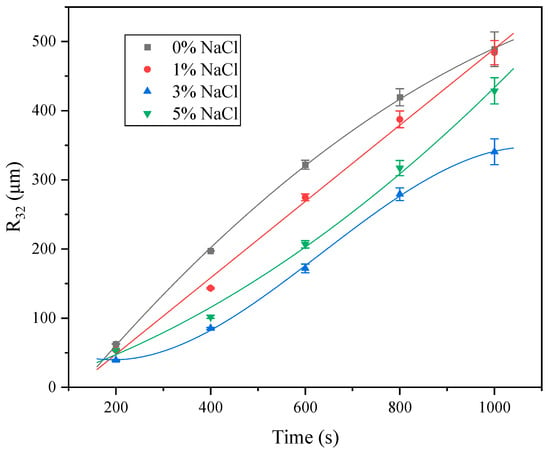

Figure 11 shows the evolution of the R32 of foams generated from 0.01 mol·L−1 SLG solutions with different NaCl concentrations. For the salt-free system (0% NaCl), the data are best fitted by a quadratic curve, where the slope decreases with time, indicating that bubble growth slows down during the later stage. In the presence of 1% NaCl, the growth of R32 follows a linear function, suggesting a nearly constant coarsening rate throughout the measurement. At 5% NaCl, however, the quadratic fit exhibits an increasing slope with time, implying that bubble coarsening accelerates at the later stage. For the 3% NaCl system, the variation of R32 is described by a cubic function, with an inflection point appearing at approximately 600 s. This inflection is characteristic of a transition in the dominant coarsening mechanism, and it provides a useful marker when comparing the effects of NaCl concentration.

Figure 11.

Bubble size (R32) of SLG with different NaCl concentrations at different times. The concentration of the LG surfactant is 0.01 mol·L−1. Error bars indicate the variation in mean R32 values from three independent measurements.

The distinct fitting behaviors observed at different NaCl concentrations reflect the influence of ionic strength on interfacial properties and foam stability. In the absence of NaCl, strong electrostatic repulsion between the doubly charged carboxylate headgroups enhances interfacial elasticity and Marangoni effects, thereby retarding bubble coarsening in the later stage. At 1% NaCl, partial electrostatic screening reduces headgroup repulsion but still maintains sufficient interfacial stability, leading to a constant coarsening rate dominated by drainage and moderate gas diffusion. The 3% NaCl system exhibits a transitional behavior, with a clear inflection at 600 s: before 600 s, the coarsening process is mainly governed by gravitational drainage, whereas after 600 s, gas diffusion through the thinning films becomes the predominant mechanism. This mechanistic shift explains the cubic fitting and underscores the role of ionic strength in modulating the balance between drainage and diffusion during foam aging. When the NaCl concentration increases to 5%, the extensive screening and counterion binding significantly reduce surface elasticity and Marangoni recovery, resulting in accelerated gas diffusion across thin films and faster bubble growth at the later stage [35].

The curves of the water content of the foam liquid film over time are shown in Figure 12. SLG solutions containing 3% and 5% NaCl show lower initial liquid hold-up. Between 300 and 600 s, these two solutions retain slightly more water than the 0% and 1% NaCl samples. This behavior aligns with the differences in the bubble-size parameter R32 shown in Figure 11, indicating that variations in drainage dynamics during this period may play a role.

Figure 12.

The liquid volume in the foam of SLG at different NaCl concentrations. The concentration of the SLG surfactant is 0.01 mol·L−1. The SLG surfactant solution is prepared using a buffer solution (pH = 7) containing NaCl at different concentrations.

3.3. Comparison with SDS

Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) is the most common anionic surfactant with good foam performance. We aim to compare the performance of LG and SDS, which is a complex task due to variations in surfactant concentration, kinds of counter ion and inorganic salts, and the anionic head group. Moreover, there is a significant difference between carboxylate and sulfate salts.

The surface tension of SDS reported in the literature is 39 mN·m−1, and the cmc is 0.008 mol·L−1 [36]. The surface tension and cmc of dodecyl sulfate decreases as follows: Li+ > Na+ > Cs+ [37]. This may be related to the hydrated radius of counterions. The hydrated radius of Na+, K+, and NH4+ are relatively close. Similarly, adding NaCl reduces the surface tension and cmc of SDS, and decreases with increasing NaCl concentration [38,39,40].

The foamability of SDS has been studied using the shaking method and the Ross–Miles technique. The foaming ability of dodecyl sulfate at a 0.05 mol·L−1 concentration decreases as follows: Na+ > Li+ > Cs+. The sodium salt of LG forms more stable micelles that cannot break up fast enough to augment the flux of monomers, which is necessary to stabilize the new air/water interface [41]. The addition of NaCl in the solutions with 0.026 mol·L−1 SDS has very little influence on the foaming ability. The NaCl concentration ranges from 0 to 0.18 mol·L−1 [42]. The impact of higher NaCl concentrations has not been addressed.

The foaming stability of dodecyl sulfate increases as follows: Li+ > Na+ > Cs+. However, at high surfactant concentrations (0.025 and 0.05 mol·L−1), the foam stability of the cesium dodecyl sulfate is unusually high [41]. In the SDS solution, the foam stability increases as the NaCl concentration increases and then gradually decreases. On the other hand, the salt concentration corresponding to the peak of foam stability increases as the SDS concentration increases [42].

4. Conclusions

In this study, the effects of different counterions (Na+, K+, NH4+) and NaCl concentrations on the surface activity and foam performance of lauroyl glutamate (LG) surfactant solutions were systematically investigated. Counterions exerted only minor effects on surface tension and cmc. The addition of NaCl decreased both surface tension and cmc by reducing electrostatic repulsion and enhancing interfacial packing. Although the influence of counterions on foaming ability was limited, the ammonium salt exhibited consistently better foaming performance over a relatively wide concentration range. At LG concentrations below 0.01 mol·L−1, the addition of NaCl enhanced foaming. When the concentration exceeded 0.01 mol·L−1, higher salt contents led to an overall reduction in foaming ability. Among the tested conditions, 1% NaCl yielded the most favorable foaming performance. Foam stability was more sensitive to counterions and salt content: Na+ provided greater stability at concentrations below the cmc compared with K+ and NH4+, while K+ enhanced stability at concentrations above the cmc. Notably, increasing NaCl content markedly decreased surface tension, but excessive salt addition destabilized the foam. At 0.01 mol·L−1, the foam stabilities of SLG solutions with different NaCl contents were comparable, but the solution containing 3% NaCl exhibited the slowest foam aging rate. This work offers useful insight into how monovalent counterions and NaCl influence the foaming behavior of LG surfactants, which may help guide future studies on the potential role of electrolyte-induced interfacial structuring in shaping the dynamic interfacial properties of such systems.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/colloids9060082/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.H. and T.C.; investigation, writing—original draft preparation, T.C.; writing—review and editing, supervision, F.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| LG | Lauroyl glutamate |

| SLG | Sodium lauroyl glutamate |

| PLG | Potassium lauroyl glutamate |

| ALG | Ammonium lauroyl glutamate |

| SDS | Sodium dodecyl sulfate |

References

- Guo, J.; Sun, L.; Zhang, F.; Sun, B.; Xu, B.; Zhou, Y. Review: Progress in synthesis, properties and application of amino acid surfactants. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2022, 794, 139499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Hu, X.; Fang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Li, H.; Xia, Y. The α-Substituent effect of amino acids on performance of N-Lauroyl amino acid surfactants. J. Mol. Liq. 2024, 409, 125397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshikur, R.M.; Chowdhury, M.R.; Wakabayashi, R.; Tahara, Y.; Moniruzzaman, M.; Goto, M. Characterization and cytotoxicity evaluation of biocompatible amino acid esters used to convert salicylic acid into ionic liquids. Int. J. Pharm. 2018, 546, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mustahil, N.A.; Baharuddin, S.H.; Abdullah, A.A.; Reddy, A.V.B.; Abdul Mutalib, M.I.; Moniruzzaman, M. Synthesis, characterization, ecotoxicity and biodegradability evaluations of novel biocompatible surface active lauroyl sarcosinate ionic liquids. Chemosphere 2019, 229, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, W.S.; Gitamara, S.; Wartakusumah, R.; Nurdin, M.I.; Masyithah, Z. Implementation of amino acid as a natural feedstock in production of N-acylamides as a biocompatible surfactants: A review on synthesis, behavior, application and scale-up process. J. Pure App. Chem. Res. 2022, 11, 9–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ananthapadmanabhan, K.P. Amino-acid surfactants in personal cleansing (review). Tenside Surfactants Deterg. 2019, 56, 378–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, S.A.; Kamlekar, R.K. Function and therapeutic potential of N-acyl amino acids. Chem. Phys. Lipids 2021, 239, 105114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.; Ménard-Moyon, C.; Bianco, A. Self-assembly of amphiphilic amino acid derivatives for biomedical applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2022, 51, 3535–3560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barai, M.; Manna, E.; Sultana, H.; Mandal, M.K.; Guchhait, K.C.; Manna, T.; Patra, A.; Chang, C.-H.; Moitra, P.; Ghosh, C. Micro-structural investigations on oppositely charged mixed surfactant gels with potential dermal applications. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 15527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ichihara, K.; Sugahara, T.; Akamatsu, M.; Sakai, K.; Sakai, H. Rheology of α-gel formed by amino acid-based surfactant with long-chain alcohol: Effects of inorganic salt concentration. Langmuir 2021, 37, 7032–7038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aramaki, K.; Shiozaki, Y.; Kosono, S.; Ikeda, N. Coacervation in cationic polyelectrolyte solutions with anionic amino acid surfactants. J. Oleo Sci. 2020, 69, 1411–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barai, M.; Mandal, M.K.; Karak, A.; Bordes, R.; Patra, A.; Dalai, S.; Panda, A.K. Interfacial and aggregation behavior of dicarboxylic amino acid-based surfactants in combination with a cationic surfactant. Langmuir 2019, 35, 15306–15314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barai, M.; Mandal, M.K.; Sultana, H.; Manna, E.; Das, S.; Nag, K.; Ghosh, S.; Patra, A.; Panda, A.K. Theoretical approaches on the synergistic interaction between double-headed anionic amino acid-based surfactants and hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide. J. Surfactants Deterg. 2020, 23, 891–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Gao, Z.; Zhu, H.; Zhang, Q. Mixed micellization of cationic/anionic amino acid surfactants: Synergistic effect of sodium lauroyl glutamate and alkyl tri-methyl ammonium chloride. J. Dispers. Sci. Technol. 2022, 43, 2227–2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; He, B.; Huang, J.; Xu, H. Study on the compounding of sodium N-lauroyl glutamate and cationic cellulose. Tenside Surfactants Deterg. 2022, 59, 492–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeda, N.; Aramaki, K. Hydrogel formation by glutamic-acid-based organogelator using surfactant-mediated gelation. J. Oleo Sci. 2022, 71, 1169–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; He, C.; Zhang, D.; Jiang, W.; Zhang, W. Research on viscoelastic properties of SLG-LHSB system: Effects of pH and concentration on micelles in the system. J. Mol. Liq. 2022, 367, 120593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Sun, Y.; Deng, Q.; Qi, X.; Sun, H.; Li, Y. Study of the environmental responsiveness of amino acid-based surfactant sodium lauroylglutamate and its foam characteristics. Colloids Surf. A-Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2016, 504, 384–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Song, Z.; Han, F.; Xu, B.; Xu, B. Synthesis and properties of pH-dependent N-acylglutamate/aspartate surfactants. Colloids Surf. A-Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2022, 640, 128474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, Y.; Zhang, H.; Song, X.; Wang, Z.; Wang, X.; Li, Y. Comparative study on foaming and foam stability of multiple mixed systems of fluorocarbon, hydrocarbon, and amino acid surfactants. J. Surfactants Deterg. 2023, 26, 683–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, W.; Lv, H.; Fan, J.; Qiang, T.; Liu, C.; Ji, Y.; Dong, S. Investigation of a highly efficient foaming mixture compromising cationic Gemini-zwitterionic-anionic surfactants for gas well deliquification. Tenside Surfactants Deterg. 2024, 61, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Fang, Y.; Hu, X.; Sun, Y.; Li, H.; Xia, Y. Predicting the foamability of N-acyl amino acid surfactants via noncovalent interactions. Colloids Surf. A-Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2025, 709, 136072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; He, Z.; Han, F.; Zhou, Y.; Xu, B. Synthesis and properties of two amino carboxylic acid gemini surfactants. J. Surfactants Deterg. 2020, 23, 1033–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, M.J.; Kunjappu, J.T.B. Surfactants and Interfacial Phenomena, 4th ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012; pp. 67–69. [Google Scholar]

- Vlachy, N.; Jagoda-Cwiklik, B.; Vácha, R.; Touraud, D.; Jungwirth, P.; Kunz, W. Hofmeister series and specific interactions of charged headgroups with aqueous ions. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2009, 146, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, K.D.; Neilson, G.W.; Enderby, J.E. Ions in water: Characterizing the forces that control chemical processes and biological structure. Biophys. Chem. 2007, 128, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qazi, M.J.; Schlegel, S.J.; Backus, E.H.G.; Bonn, M.; Bonn, D.; Shahidzadeh, N. Dynamic surface tension of surfactants in the presence of high salt concentrations. Langmuir 2020, 36, 7956–7964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Liu, Y.; Wang, P.; Liu, R.; Jiang, Y. Influence of inorganic salt additives on the surface tension of sodium dodecylbenzene sulfonate solution. Processes 2023, 11, 1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Israelachvili, J.N.B. Intermolecular and Surface Forces, 3rd ed.; Academic Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2011; pp. 309–311. [Google Scholar]

- Le Roux, S.; Roché, M.; Cantat, I.; Saint-Jalmes, A. Soluble surfactant spreading: How the amphiphilicity sets the Marangoni hydrodynamics. Phys. Rev. E 2016, 93, 013107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaminsky, V.V.; Ohnishi, S.; Vogler, E.A.; Horn, R.G. Stability of Aqueous Films between Bubbles. Part 1. The Effect of Speed on Bubble Coalescence in Purified Water and Simple Electrolyte Solutions. Langmuir 2010, 26, 8061–8074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danov, K.D.; Kralchevsky, P.A.; Denkov, N.D.; Ananthapadmanabhan, K.P.; Lips, A. Mass transport in micellar surfactant solutions: 1. Relaxation of micelle concentration, aggregation number and polydispersity. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2006, 119, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danov, K.D.; Kralchevsky, P.A.; Denkov, N.D.; Ananthapadmanabhan, K.P.; Lips, A. Mass transport in micellar surfactant solutions: 2. Theoretical modeling of adsorption at a quiescent interface. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2006, 119, 17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denkov, N.; Tcholakova, S.; Politova-Brinkova, N. Physicochemical control of foam properties. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 2020, 50, 101376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roché, M.; Li, Z.; Griffiths, I.M.; Le Roux, S.; Cantat, I.; Saint-Jalmes, A.; Stone, H.A. Marangoni Flow of Soluble Amphiphiles. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2014, 112, 208302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.X.; Zhu, B.Y.B. Principles of Surfactant Action; China Light Industry Press: Beijing, China, 2003; p. 137. [Google Scholar]

- Schelero, N.; Hedicke, G.; Linse, P.; Klitzing, R.v. Effects of counterions and co-ions on foam films stabilized by anionic dodecyl sulfate. J. Phys. Chem. B 2010, 114, 15523–15529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emami, H.; Ayatizadeh Tanha, A.; Khaksar Manshad, A.; Mohammadi, A.H. Experimental investigation of foam flooding using anionic and nonionic surfactants: A screening scenario to assess the effects of salinity and pH on foam stability and foam height. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 14832–14847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamanis, A.T.; Evgenidis, S.P.; Karapantsios, T.D.; Kostoglou, M. An Innovative Approach for Assessing Foam Stability Based on Electrical Conductivity Measurements of Liquid Films. Colloids Interfaces 2025, 9, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshavarzi, B.; Mahmoudvand, M.; Javadi, A.; Bahramian, A.; Miller, R.; Eckert, K. Salt Effects on Formation and Stability of Colloidal Gas Aphrons Produced by Anionic and Zwitterionic Surfactants in Xanthan Gum Solution. Colloids Interfaces 2020, 4, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, S.; Bagwe, R.P.; Shah, D.O. Effect of counterions on surface and foaming properties of dodecyl sulfate. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2003, 267, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, N.; Yu, X.; Sheng, Y.; Zong, R.; Li, C.; Lu, S. Role of salts in performance of foam stabilized with sodium dodecyl sulfate. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2020, 216, 115474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).