1. Introduction

Ceramic matrix composites have garnered considerable attention and application across various fields, including chemistry and mechanical engineering, due to their remarkable mechanical, thermal, and electromagnetic properties and chemical inertness [

1,

2]. Traditional ceramics encompass a wide array of products, including porcelain, pottery, and glass. More generally, advanced ceramics are defined as materials derived from inorganic non-metallic substances through high-temperature sintering processes. This classification includes a diverse range of materials primarily composed of oxides, such as magnesium oxide, aluminum oxide, and silicon dioxide [

3]. Ceramic matrix composites are a rapidly evolving category of advanced materials. The integration of reinforcement phases, such as fiber whiskers, particulates, and platelets, into these composites leads to enhanced toughness, reduced weight, and improved fatigue resistance. These advancements enable ceramic matrix composites to meet the stringent property standards required in various technological domains [

4].

Continuous fiber-reinforced ceramic matrix composites (CFRCMCs) represent a notable category of composite materials that employ continuous fibers as the reinforcement phase to improve their material properties. Prominent examples of these composites include Cf/SiC, SiCf/SiC, and Al

2O

3f/Al

2O

3, among others [

5]. For most CFRCMCs, the fibers and the matrix do not have an ideal connection. Interfaces are artificially formed or generated through chemical reactions [

6]. The growing demand for CFRCMCs in high-temperature industries is becoming increasingly significant [

7]. This trend is particularly observable in the automotive and railway sectors, where CFRCMCs are used in brake pads; the aerospace sector, where they are applied in engine components, thermal protection systems, and structural elements of satellites; the microelectronics field, where they function as cooling components for various devices; and the energy sector, where they play a crucial role in the fabrication of heat exchangers [

8].

In the Non-Metallic Turbine Engine Project conducted by NASA, a CFRCMC material reinforced with 20% SiC fibers was employed in the fabrication of a high-pressure turbine (HPT) nozzle and a cooled doublet vane [

9]. General Electric has actively participated in the research and application of CFRCMC materials. For instance, the HPT shrouds of the LEAP engine are constructed from CFRCMC materials, which have collectively achieved over 50 million flight hours to date. CFRCMC components are utilized in five distinct parts of the GE9X engine, comprising one inner combustor liner, one outer combustor liner, the shrouds and nozzles of the HPT Stage 1, and the nozzles of HPT Stage 2 [

10]. Zhang et al. have engineered scalable ceramic–polymer composites that utilize three-dimensional interconnected piezoelectric microfoams, which possess the ability to concurrently harvest thermal and mechanical energy. This dual-energy harvesting functionality facilitates their utilization in a diverse range of sensing and energy-generating applications [

11].

Hypersonic aerospace vehicles, which operate at velocities surpassing Mach 5, predominantly utilize ultra-high temperature ceramic matrix composites (UHTCMCs) as key materials. These ceramics generally incorporate C/SiC fibers as the reinforcement phase, and ZrB

2, ZrC, and other ultrahigh temperature ceramics comprises the matrix materials [

12]. Their operational temperatures can exceed 1800 °C, and the melting points of the oxides generated can reach up to 3000 °C [

13]. Finally, the German Aerospace Center has successfully developed a UHTCMC material, which incorporates carbon fibers and ZrB

2, utilizing the reactive melt infiltration method. This material maintains a flexural strength of 190 MPa even at temperatures as high as 900 °C [

14].

Clearly, the predominant areas in which CFRCMCs are applied center on thermo-mechanical coupling at elevated temperatures, a focus that is determined by their superior mechanical and thermal properties. However, the measurement of material properties at high temperatures is often challenging and costly. Consequently, the development of cross-property relations may increase measurement difficulties [

15]. Bristow introduced the concept of cross-property correlations, focusing on the relations between elastic modulus and electrical conductivity in solids with low-density, randomly oriented microcracks [

16]. Berryman and Milton expanded upon this work by establishing the relations between geometric parameters and material properties in two-phase composite materials [

17]. Sevostianov and Kachanov further extended the cross-property relations to anisotropic materials [

18].

The properties of composite materials can be described as functions of the same microstructural parameters [

19]. By establishing distinct functions for both mechanical and thermal properties and subsequently eliminating microstructural parameters, cross-property relations can be established in the material [

20]. This approach allows other properties of the material to be rapidly determined based on one property that is easier to measure [

21]. The investigation of cross-property relations has gained considerable attention and been extensively explored in the literature. Sevostianov et al. examined the influence of the tortuosity parameter on effective electrical conductivity and the overall mass transfer coefficient in two-phase materials, subsequently establishing cross-property relations by eliminating this parameter [

22].

There are also some studies that focus on the cross-property relations of ceramic matrix composites. Uhlířová et al. examined the relations between elastic properties and conductivity in alumina–zirconia ceramics with varying grain size ratios [

23]. Pabst et al. investigated the cross-property relations of alumina ceramics and employed thermal conductivity to predict the shear and bulk moduli of the material [

24]. However, current research mainly focuses on two-phase materials composed of fibers and matrices, without considering the significant influence of the interphase on macroscopic property prediction and the establishment of cross-property relations. Moreover, relatively limited attention has been paid to continuous fibers.

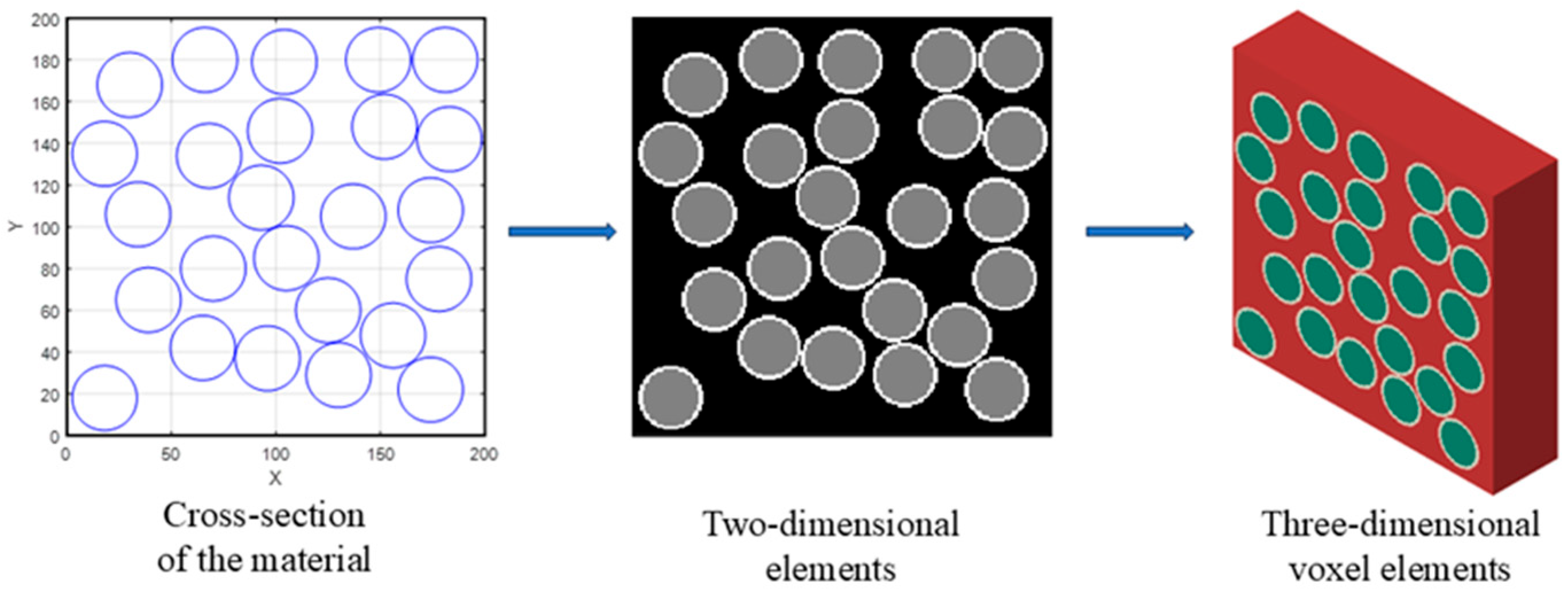

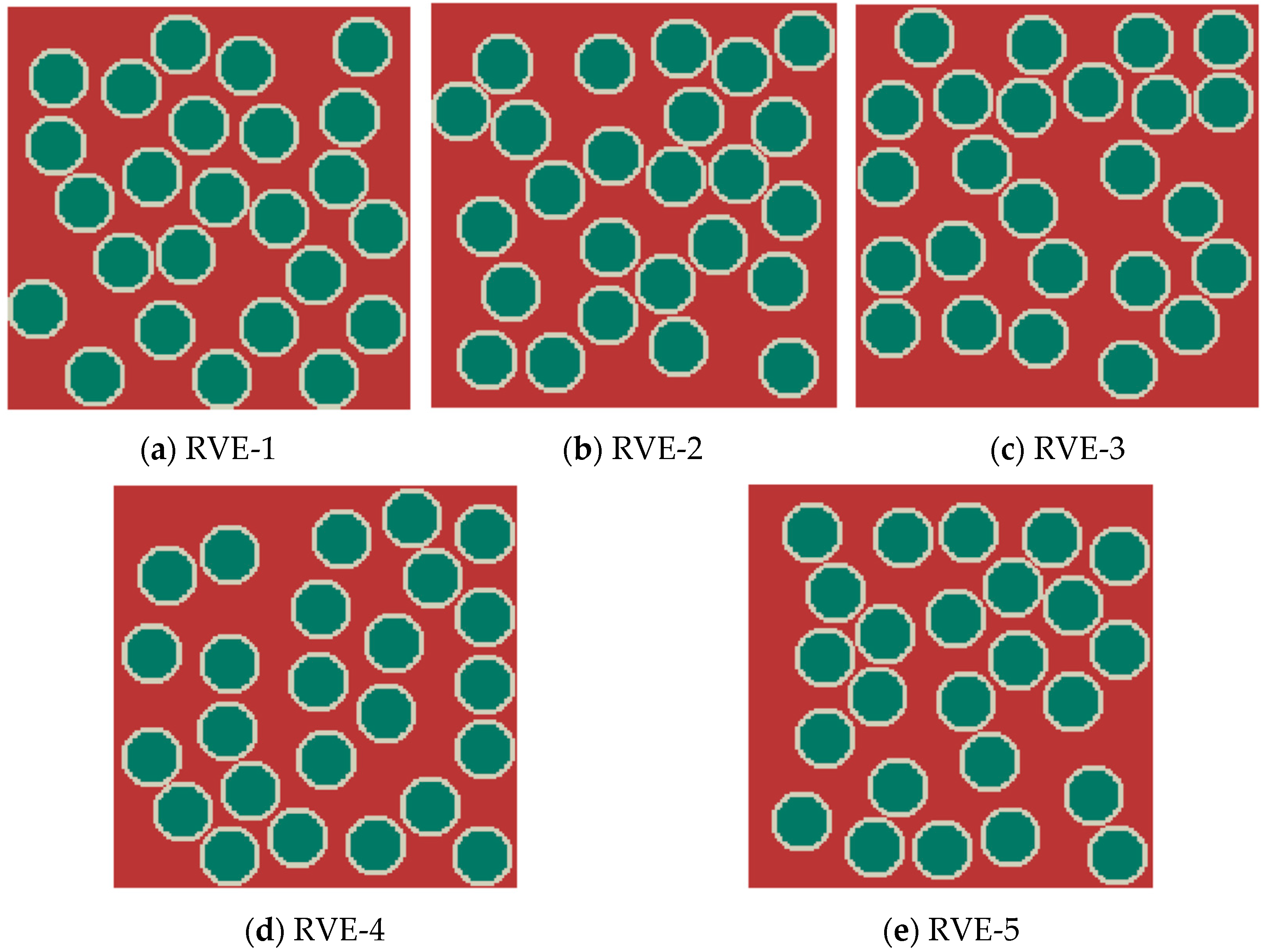

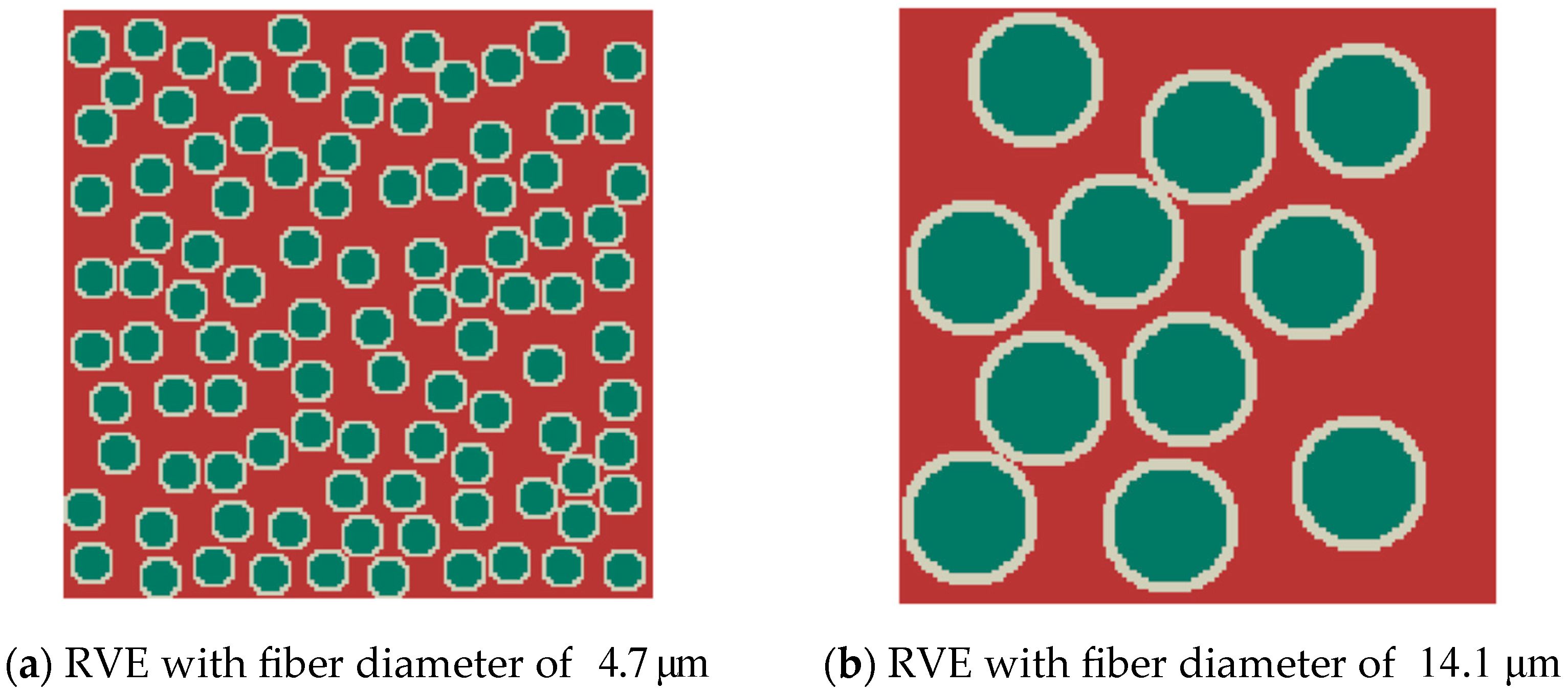

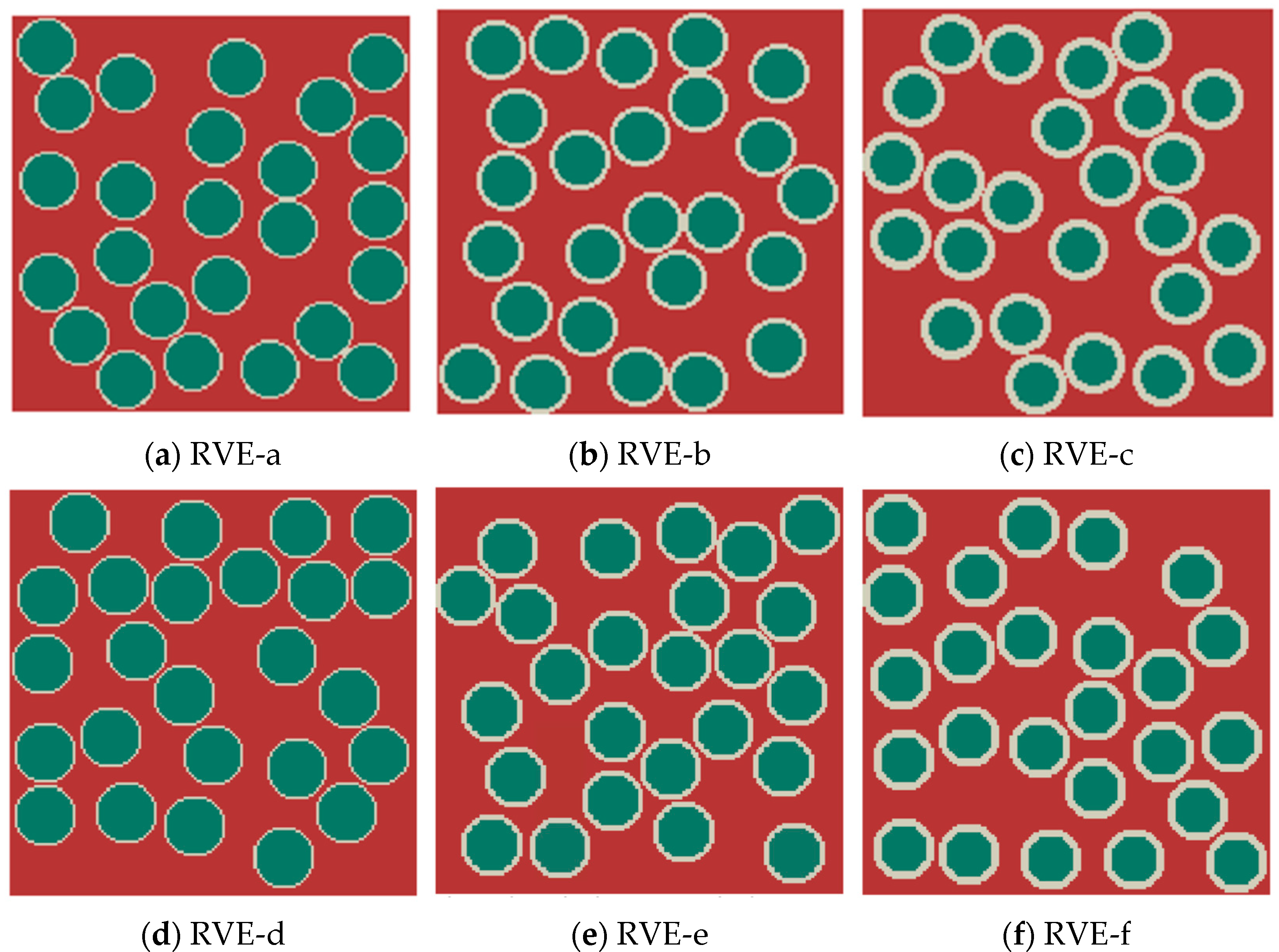

In this research, we review current micromechanics property prediction models for CFRCMCs with interfaces. Corresponding representative volume elements (RVEs) are then constructed using voxel elements to verify the models, establishing both explicit and numerical cross-property relations of CFRCMCs. Consequently, one physical property (e.g., mechanical or magnetic) can be predicted from another, more easily measurable quantity (e.g., thermal or electrical). This approach significantly mitigates the challenges associated with measuring material properties in CMCs. Furthermore, by establishing explicit connections between different physical properties, cross-property relations streamline the complexities of multi-objective optimization for these materials. Consequently, they offer substantial promises for advancing multiphysics applications, particularly in demanding thermo-mechanical environments, among others.

This paper is organized as follows: In

Section 2, the micromechanics prediction models for CFRCMCs with interfaces are first reviewed. Then, corresponding representative volume elements (RVEs) are constructed using voxel elements to verify the models.

Section 3 establishes the cross-property relations of CFRCMCs, including CFRCMCs with a fixed fiber–interphase volume ratio and volume ratios. Finally, the work of this article is summarized, and significant results are presented for guiding engineering measurement and design.

4. Conclusions

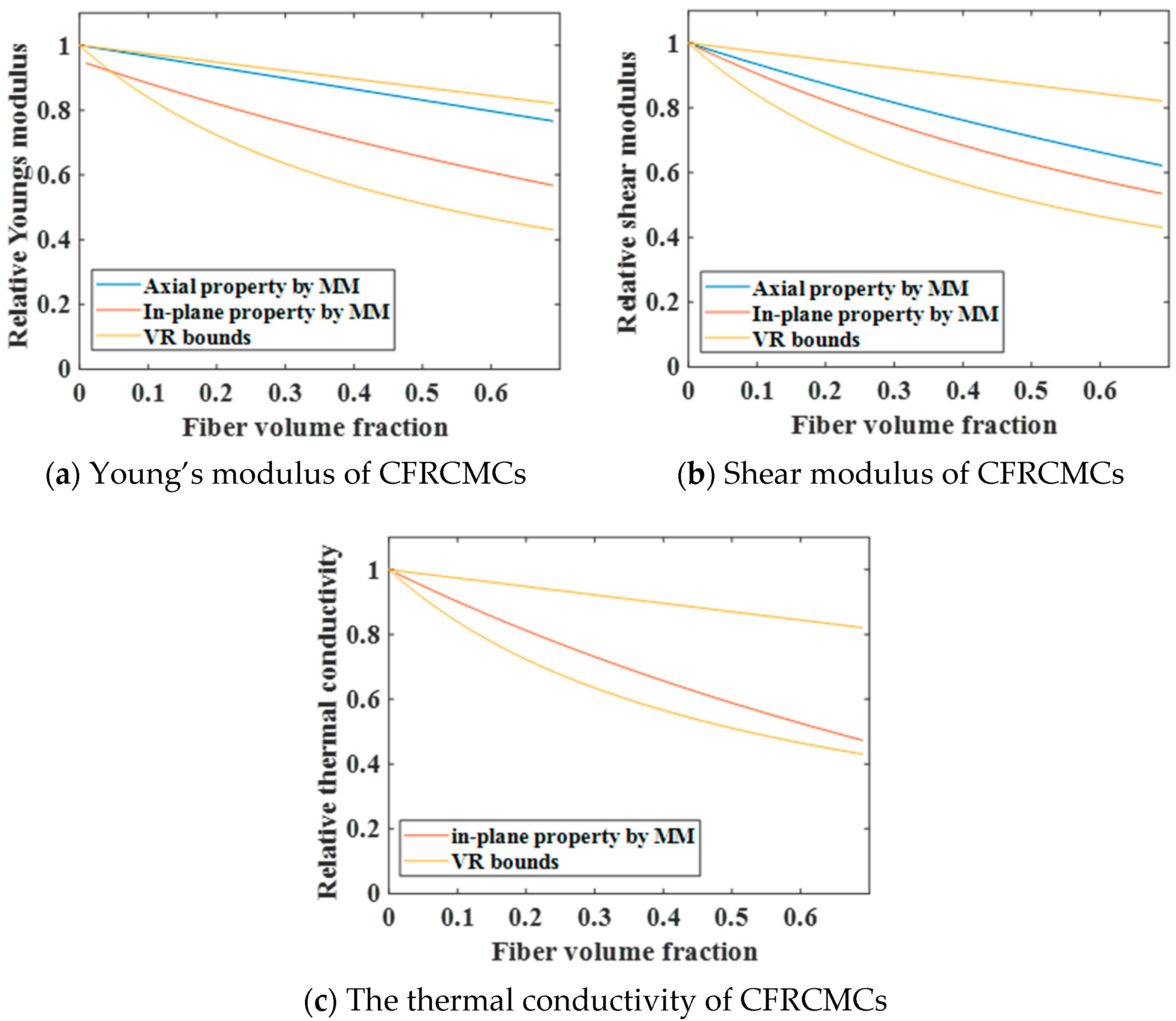

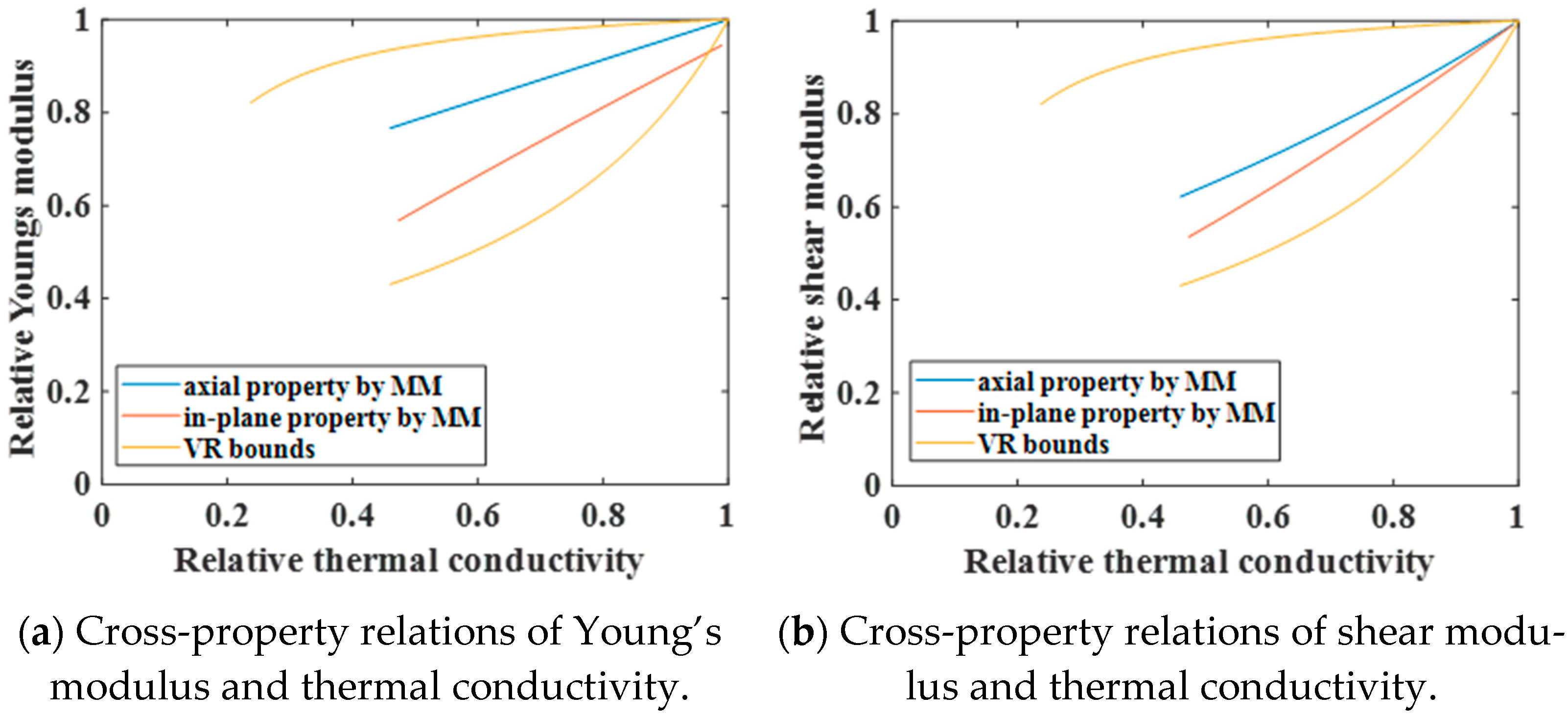

In this work, a systematic framework is established to derive and validate cross-property relations for CFRCMCs that simultaneously couple elastic and thermal responses. By integrating GSCS, effective-medium conduction models, and statistically representative voxel-based finite-element analysis, the following major findings are obtained:

For CFRCMCs, self-consistent micromechanics and effective-medium conduction models like the Hashin model can predict the mechanical and thermal properties of materials. However, for cases where the volume fraction of fibers or interphases is too high, the prediction errors are relatively large.

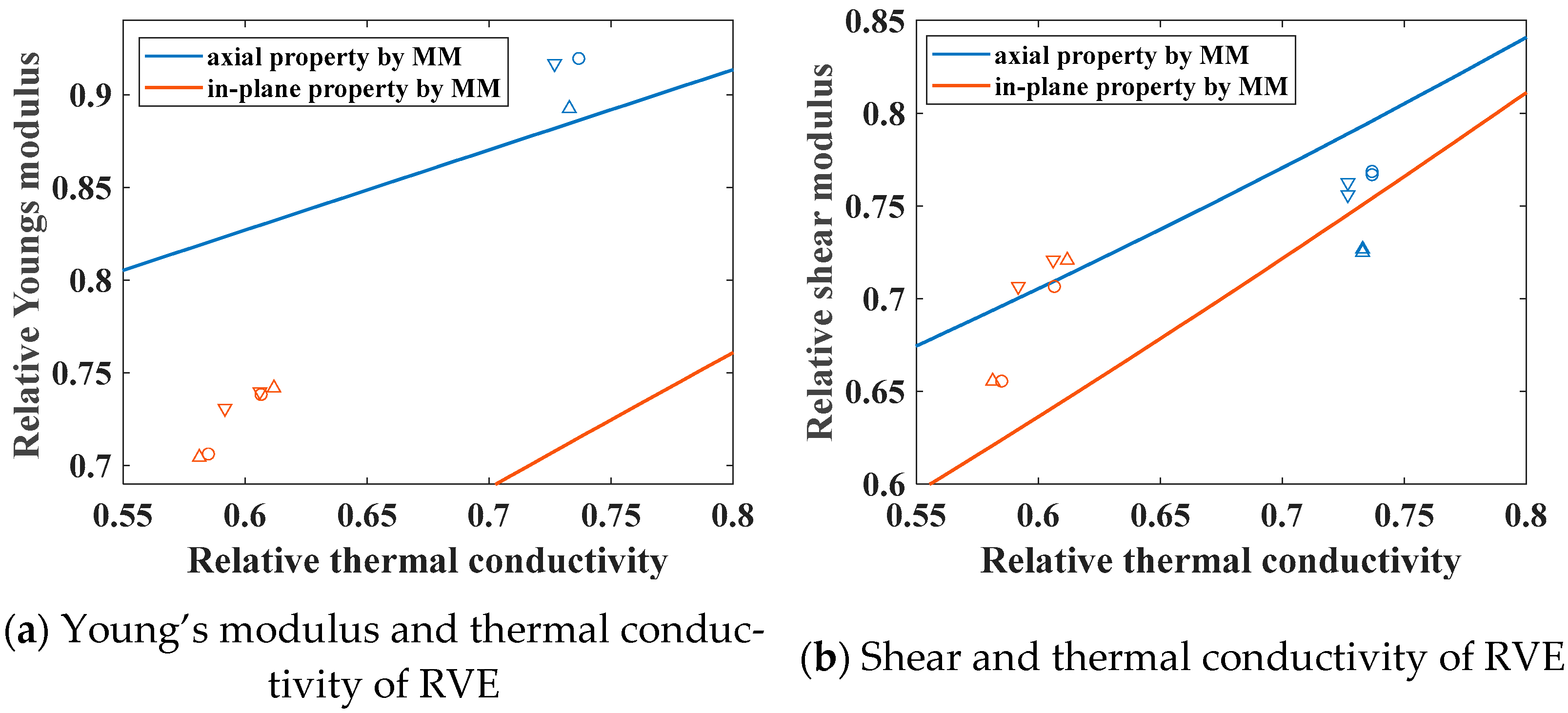

For CFRCMCs with a fixed fiber–interphase volume ratio, cross-property relations are close to being linear. The slope of the axial cross-property relation is smaller than that of its in-plane counterpart, and the slope characterizing the cross-property relation between Young’s modulus and thermal conductivity is marginally lower than that governing the relation between the shear modulus and thermal conductivity.

The influence of the random distribution of fibers, fiber diameter, and interphase properties on cross-property relations was analyzed separately. The influence of the former two parameters is relatively small, while a decrease in the interphase properties causes the curve of cross-property relations to shift downward.

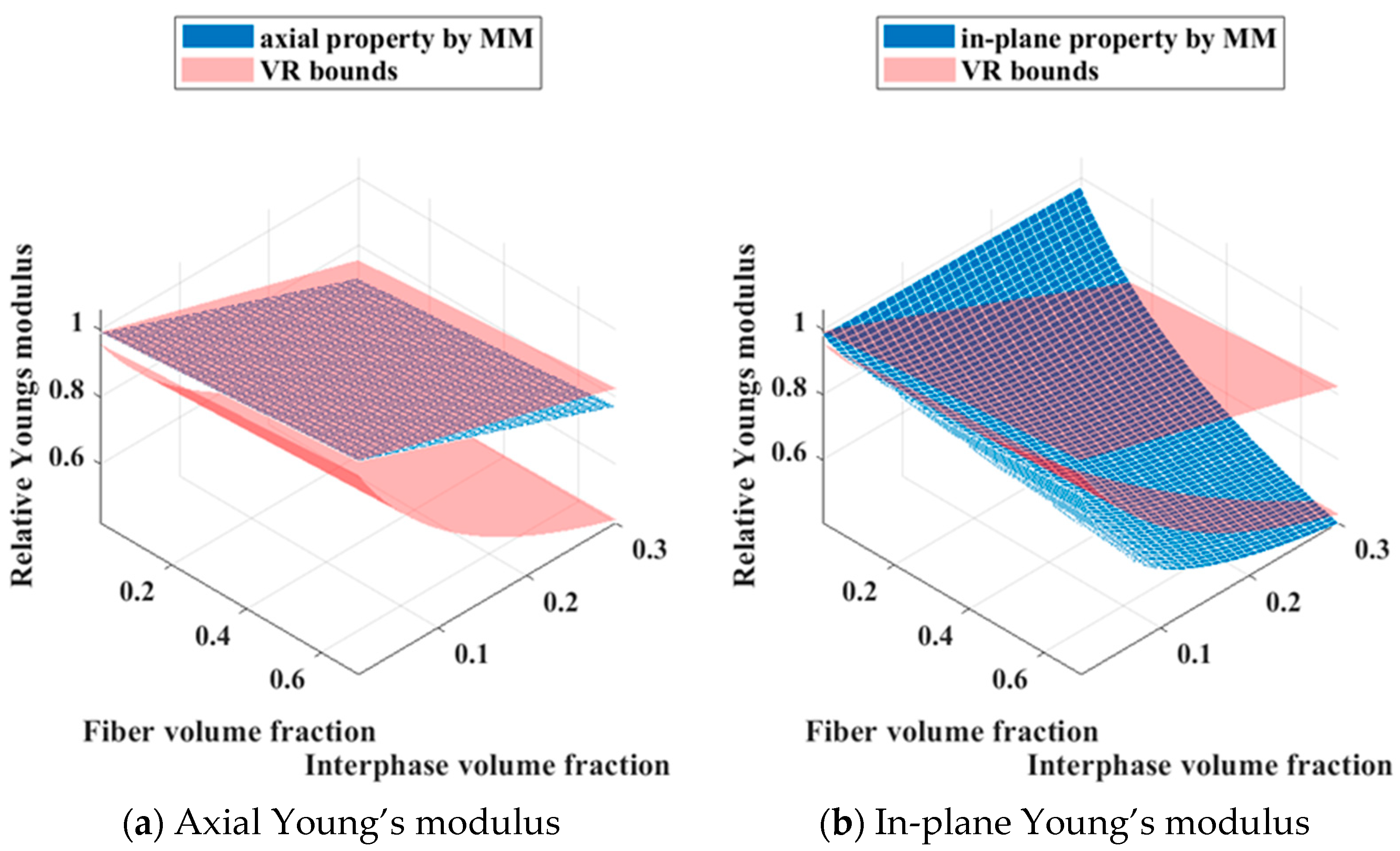

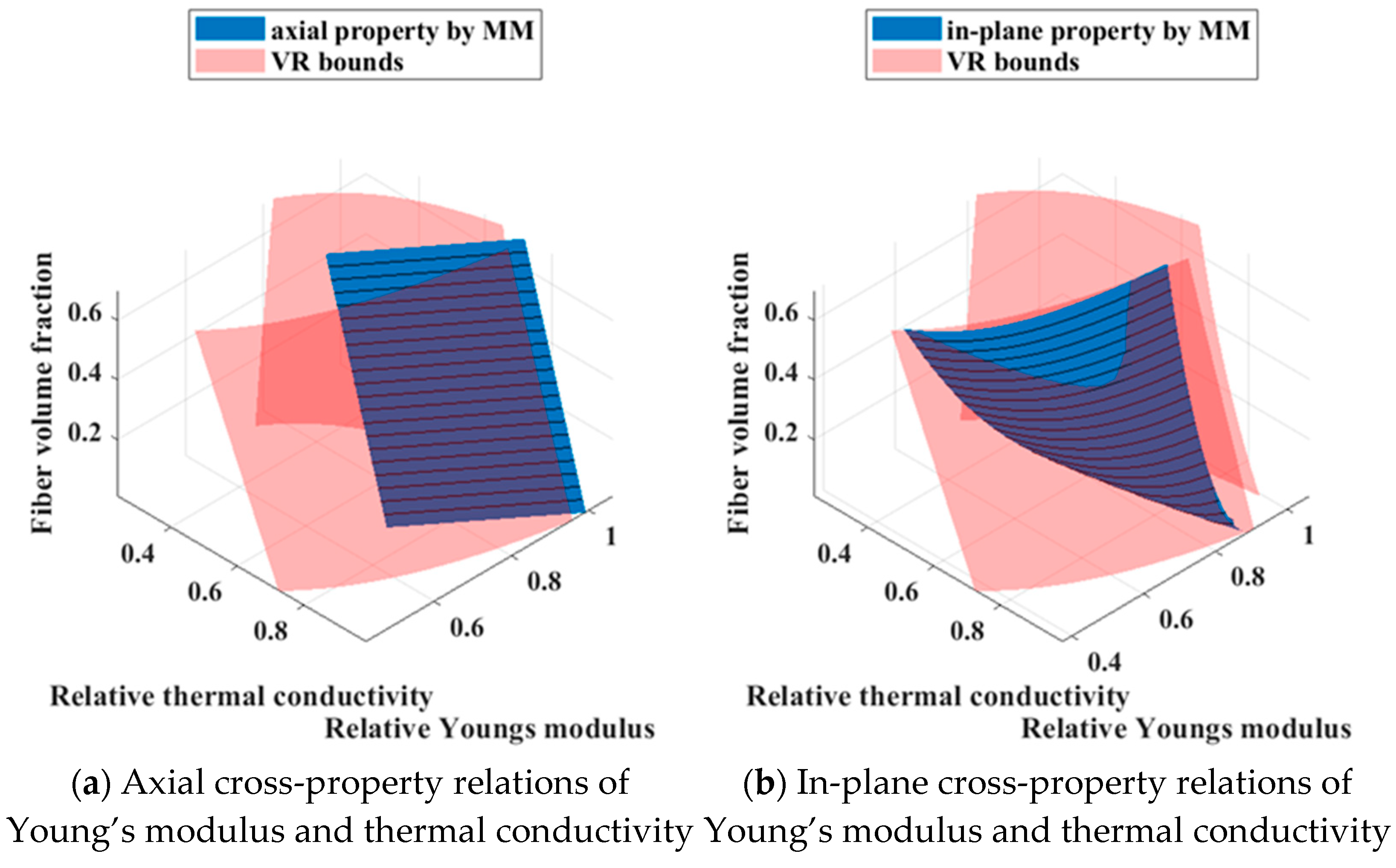

For CFRCMCs with varying fiber–interphase volume ratios, cross-property relation surfaces were established, and FEA verified their correspondence. The errors associated with in-plane cross-property relations exceed those of their axial counterparts, while Young’s modulus exhibits a marginally higher deviation than the shear modulus.

Overall, the findings indicate that CFRCMCs are applicable to cross-property relations. Consequently, one physical property (e.g., mechanical or magnetic) can be predicted from another, more easily measurable quantity (e.g., thermal or electrical). This approach significantly mitigates the challenges associated with measuring material properties in CMCs. Furthermore, by establishing explicit connections between different physical properties, cross-property relations streamline the complexities of multi-objective optimization for these materials. Consequently, they could contribute to advancing multiphysics applications, particularly in demanding thermo-mechanical environments.

To validate this relation, ceramic matrix composites with different fiber volume fractions should be fabricated, and their properties should be characterized individually to evaluate their consistency with the currently established cross-property relations. In addition, more accurate models will be developed to account for the influence of parameters such as interphase thickness on these relations.