Reinforced, Toughened, and Antibacterial Polylactides Facilitated by Multi-Arm Zn/Resin Microsphere-Based Polymers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Methods

2.1. General Procedures and Materials

2.2. Characterization

3. Results and Discussion

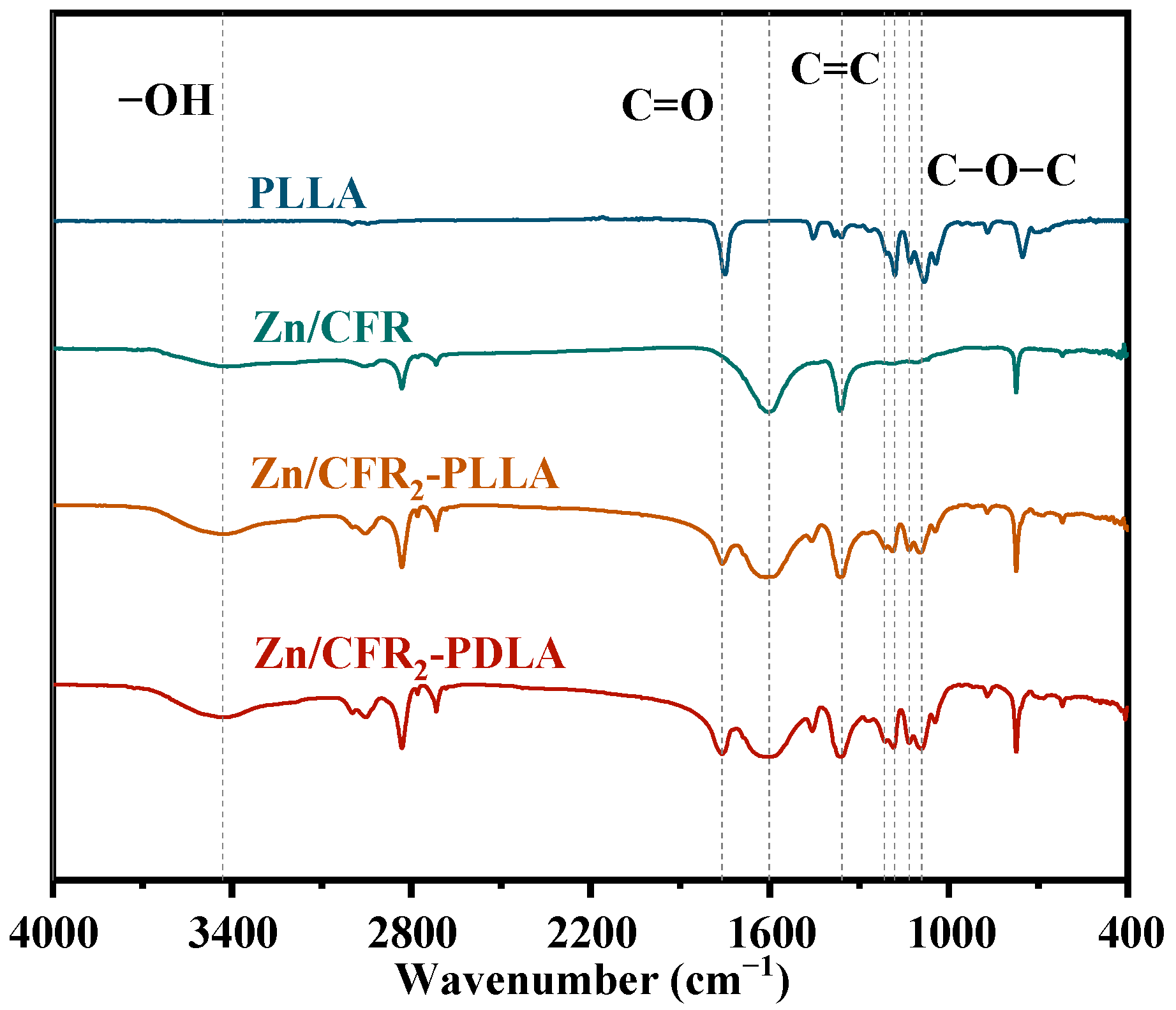

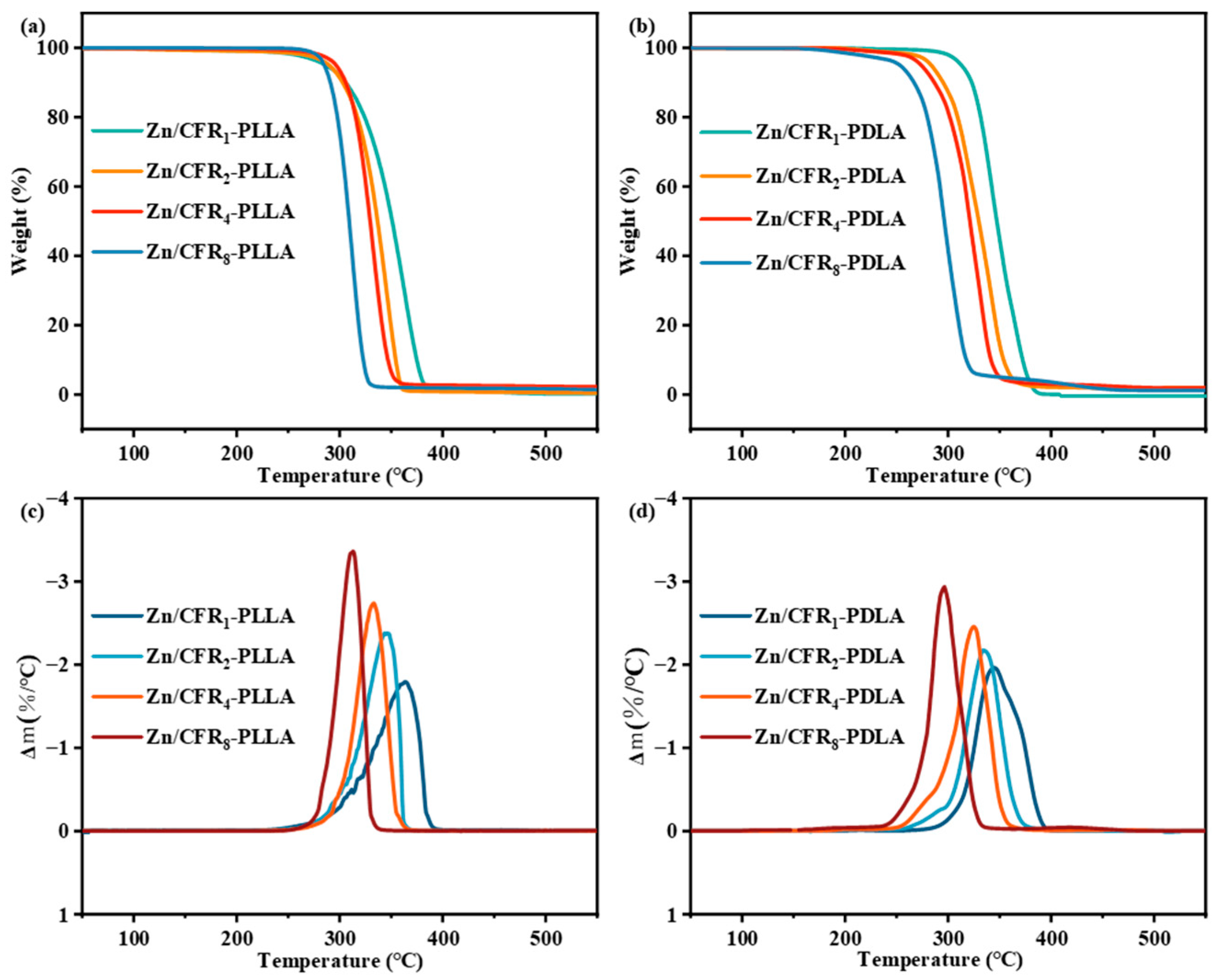

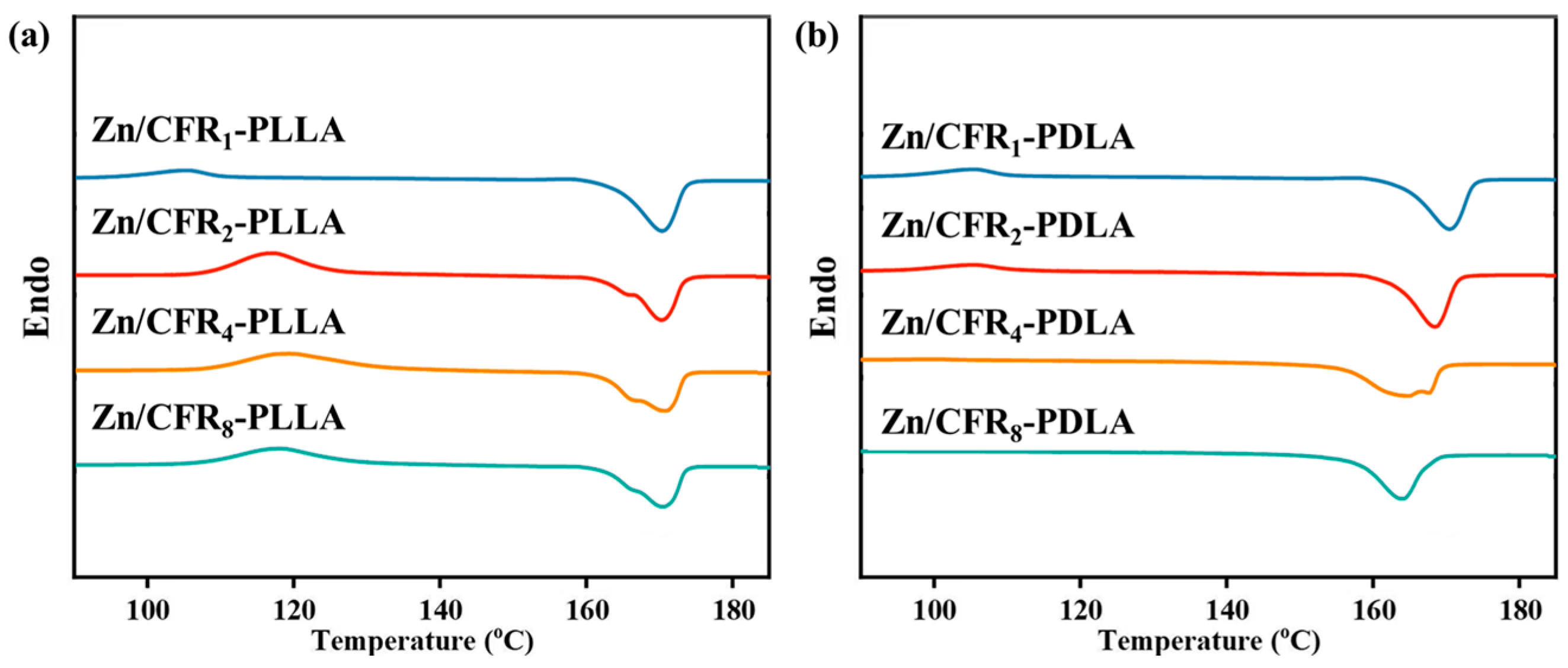

3.1. Synthesis and Characterization of Zn/CFR-PLAs

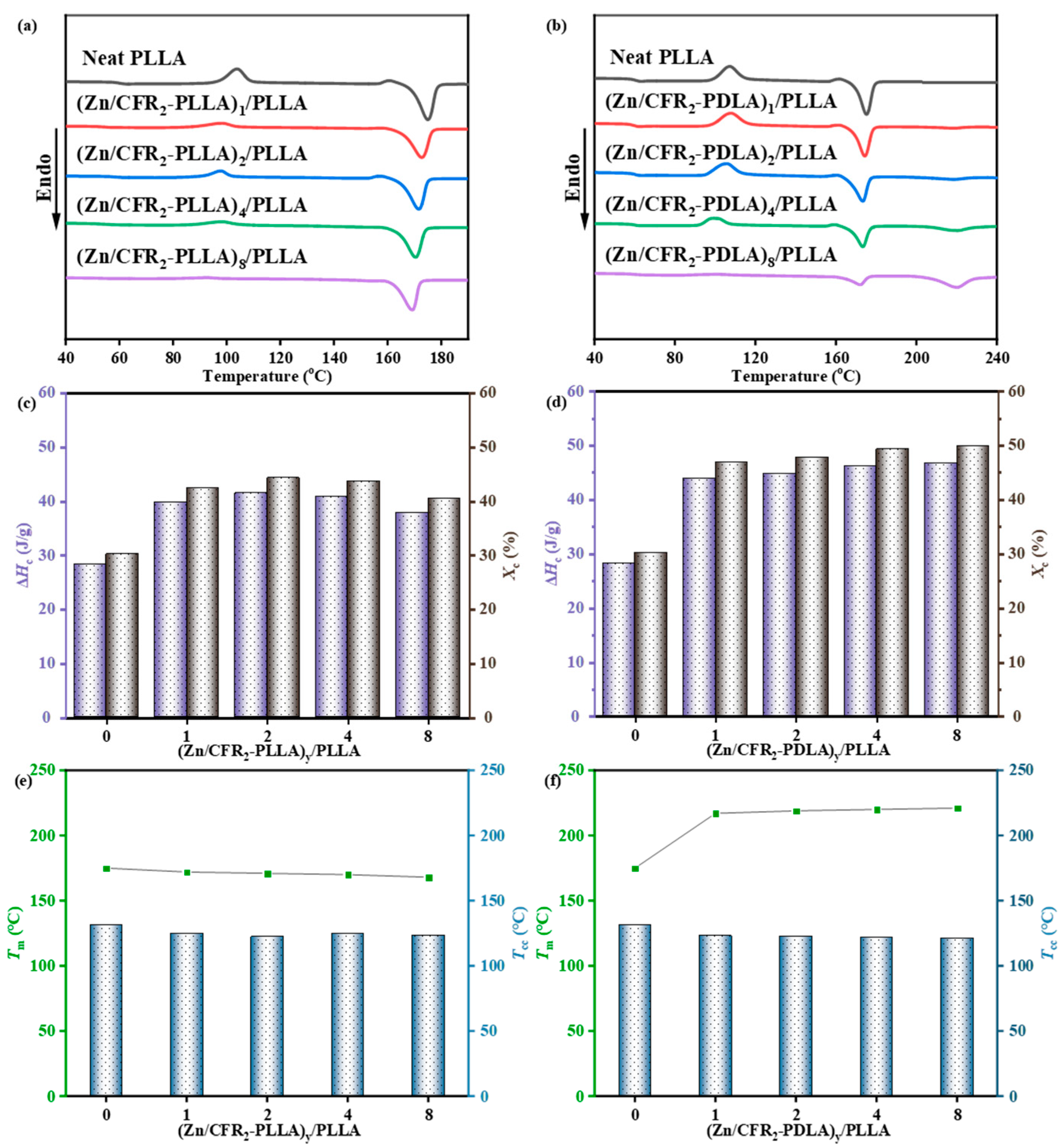

3.2. Preparation and Characterization of (Zn/CFR2-PLLA)/PLLA and (Zn/CFR2-PDLA)/PLLA Composites

3.3. Mechanical Properties and Toughening Mechanism

3.4. Morphological Analyses of Fracture Surfaces

3.5. Antibacterial Performance Analysis

3.6. Spinning Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shahdan, D.; Rosli, N.A.; Chen, R.S.; Ahmad, S.; Gan, S. Strategies for strengthening toughened poly(lactic acid) blend via natural reinforcement with enhanced biodegradability: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 251, 126214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, M.S.; Elahee, G.M.F.; Fang, Y.H.; Yu, X.; Advincula, R.C.; Cao, C.Y. Polylactic acid (PLA)-based multifunctional and biodegradable nanocomposites and their applications. Compos. Part B Eng. 2025, 306, 112842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, N.; Misra, M.; Mohanty, A.K. Durable polylactic acid (PLA)-based sustainable engineered blends and biocomposites: Recent developments, challenges, and opportunities. ACS Eng. Au 2021, 1, 7–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahsan, W.A.; Hussain, A.; Lin, C.; Nguyen, M.K. Biodegradation of different types of bioplastics through composting—A recent trend in green recycling. Catalysts 2023, 13, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maragkaki, A.; Malliaros, N.G.; Sampathianakis, I.; Lolos, T.; Tsompanidis, C.; Manios, T. Evaluation of biodegradability of polylactic acid and compostable bags from food waste under industrial composting. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lors, C.; Leleux, P.; Park, C.H. State of the art on biodegradability of bio-based plastics containing polylactic acid. Front. Mater. 2025, 11, 1476484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baccar Chaabane, A.; Robbe, E.; Schernewski, G.; Schubert, H. Decomposition behavior of biodegradable and single-use tableware items in the Warnow Estuary (Baltic Sea). Sustainability 2022, 14, 2544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagarajan, V.; Mohanty, A.K.; Misra, M. Perspective on polylactic acid (PLA) based sustainable materials for durable applications: Focus on toughness and heat resistance. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2016, 4, 2899–2916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasidharan, S.; Tey, L.-H.; Djearamane, S.; Ab Rashid, N.K.M.; Pa, R.; Rajendran, V.; Syed, A.; Wong, L.S.; Santhanakrishnan, V.K.; Asirvadam, V.S.; et al. Innovative use of chitosan/ZnO NPs bio-nanocomposites for sustainable antimicrobial food packaging of poultry meat. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2024, 43, 101298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farah, S.; Anderson, D.G.; Langer, R. Physical and mechanical properties of PLA, and their functions in widespread applications—A comprehensive review. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2016, 107, 367–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, K.; Schreck, K.; Hillmyer, M. Toughening polylactide. Polym. Rev. 2008, 48, 85–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razavi, M.; Wang, S.Q. Why is crystalline poly(lactic acid) brittle at room temperature? Macromolecules 2019, 52, 5429–5441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, B.Y.; Wang, Y.N.; Gong, T.Y.; Wang, R.; Huang, L.P.; Li, B.J.; Li, J.C. Fabrication of highly efficient biodegradable oligomeric lactate flame-retardant plasticizers for ultra-flexible flame-retardant poly (lactic acid) composites. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 485, 149932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komeijani, M.; Bahri-Laleh, N.; Mirjafary, Z.; D’Alterio, M.C.; Rouhani, M.; Sakhaeinia, H.; Moghaddam, A.H.; Mirmohammadi, S.A.; Poater, A. PLA/PMMA reactive blending in the presence of MgO as an exchange reaction catalyst. Polymers 2025, 17, 845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.T.; Zhang, Z.Q.; He, Y.P.; Yan, W.X.; Yu, M.H.; Han, K.Q. Synergistic toughening of polylactide by layer structure and network structure. Polymer 2025, 317, 127969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, G.Y.; Yong, Q.W.; Hu, L.Q.; Rosqvist, E.; Peltonen, J.; Hu, Y.C.; Xu, W.Y.; Xu, C.L. Molecular engineering of nanocellulose-poly(lactic acid) bio-nanocomposite interface by reactive surface grafting from copolymerization. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 306, 141371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastalygina, E.E.; Aleksanyan, K.V. Recent approaches to the plasticization of poly(lactic Acid) (PLA) (A Review). Polymers 2023, 16, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samadi, K.; Francisco, M.; Hegde, S.; Diaz, C.A.; Trabold, T.A.; Dell, E.M.; Lewis, C.L. Mechanical, rheological and anaerobic biodegradation behavior of a Poly(lactic acid) blend containing a Poly(lactic acid)-co-poly(glycolic acid) copolymer. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2019, 170, 109018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gisbert Roca, F.; Martínez-Ramos, C.; Ivashchenko, S.; García-Bernabé, A.; Compañ, V.; Monleón Pradas, M. Polylactic acid nanofiber membranes grafted with carbon nanotubes with enhanced mechanical and electrical properties. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2023, 5, 6081–6094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valle Reyes, O.S.; Orozco-Guareño, E.; Hernández-Montelongo, R.; Alvarado Mendoza, A.G.; Martínez Chávez, L.; González Núñez, R.; Aguilar Martínez, J.; Moscoso Sánchez, F.J. Grafting of lactic acid and ε-caprolactone onto alpha-cellulose and sugarcane bagasse cellulose: Evaluation of mechanical properties in polylactic acid composites. Polymers 2024, 16, 2964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasidharan, S.; Tey, L.-H.; Djearamane, S.; Mahmud Ab Rashid, N.K.; Pa, R.; Shing Wong, L.; Tanislaus Antony Dhanapal, A.C. Development of novel biofilm using Musa acuminata (waste banana leaves) mediated biogenic zinc oxide nanoparticles reinforced with chitosan blend. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 2024, 36, 103080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerard, T.; Budtova, T. Morphology and molten-state rheology of polylactide and polyhydroxyalkanoate blends. Eur. Polym. J. 2012, 48, 1110–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.F.; Lu, X.; Huang, D.; Ding, Y.L.; Li, J.S.; Dai, Z.Y.; Sun, L.M.; Li, J.; Wei, X.H.; Wei, J.; et al. Ultra-tough polylactide/bromobutyl rubber-based ionomer blends via reactive blending strategy. Front. Chem. 2022, 10, 923174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afshar, S.; Rashedi, S.; Nazockdast, H.; Ghazalian, M. Preparation and characterization of electrospun poly(lactic acid)-chitosan core-shell nanofibers with a new solvent system. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 138, 1130–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.M.; Zhu, M.K.; Huang, Z.G.; Yang, F.; Weng, Y.X.; Zhang, C.L. The effect of polylactic acid-based blend films modified with various biodegradable polymers on the preservation of strawberries. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2024, 45, 101333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alias, N.F.; Ismail, H. An overview of toughening polylactic acid by an elastomer. Polym. Plast. Technol. Mater. 2019, 58, 1399–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, L.H.; Li, L.W.; Mi, H.Y.; Chen, B.Y.; Sharma, P.; Ma, H.Y.; Hsiao, B.S.; Peng, X.F.; Kuang, T.R. Superior impact toughness and excellent storage modulus of poly(lactic acid) foams reinforced by shish-kebab nanoporous structure. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 21071–21076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.P.; Li, J.C.; Liu, J.C.; Zhou, W.Y.; Peng, S.X. Recent progress of preparation of branched poly(lactic acid) and its application in the modification of polylactic acid materials. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 193, 874–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Y.; Jia, S.H.; Fang, C.; Tan, L.C.; Qin, S.; Yin, X.C.; Park, C.B.; Qu, J.P. Constructing synergistically strengthening-toughening 3D network bundle structures by stereocomplex crystals for manufacturing high-performance thermoplastic polyurethane nanofibers reinforced poly(lactic acid) composites. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2023, 232, 109847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.Z.; Zhang, J.W. Research progress in toughening modification of poly(lactic acid). J. Polym. Sci. Part B Polym. Phys. 2011, 49, 1051–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejada-Oliveros, R.; Fiori, S.; Gomez-Caturla, J.; Lascano, D.; Montanes, N.; Quiles-Carrillo, L.; Garcia-Sanoguera, D. Development and characterization of polylactide blends with improved toughness by reactive extrusion with lactic acid oligomers. Polymers 2022, 14, 1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Huang, L.P.; Zhou, S.J.; Li, J.J.; Qi, C.Z.; Tao, H.Y. Synthesis and investigation of sustainable long-chain branched poly(lactic acid-r-malic acid) copolymer as toughening agent for PLA blends. Polymer 2024, 293, 126634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, C.B.; Zheng, S.S.; Sun, S.L. Modification of reactive PB-g-SAG core-shell particles to achieve higher toughening ability for brittle polylactide. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2022, 62, 2283–2293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Ma, J.J.; Yang, J.X. Acrylonitrile-styrene–acrylate@ silicone three layers core-shell nanostructure copolymer with excellent impact toughness and highness-strength balance. React. Funct. Polym. 2025, 209, 106168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.W.; Zhang, Z.; Huang, R.; Tan, L.J. Advances in toughening modification methods for epoxy resins: A comprehensive review. Polymers 2025, 17, 1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.Q.; Chen, J.W.; Ding, S.S.; Kong, W.M.; Xing, M.X.; Wu, M.; Wang, Z.G.; Wang, Z.K. Bio-based polyamide-assisted supertoughening of polylactide through hardening of the EGMA elastomeric domains of much low amount. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 556, 149845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.T.; Zhang, Y.T.; Hu, H.; Li, J.C.; Zhou, W.Y.; Zhao, X.P.; Peng, S.X. Effect of maleic anhydride grafted poly(lactic acid) on rheological behaviors and mechanical performance of poly(lactic acid)/poly(ethylene glycol) (PLA/PEG) blends. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 31629–31638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, L.; Xu, H.; Niu, B.; Ji, X.; Chen, J.; Li, Z.M.; Hsiao, B.S.; Zhong, G.J. Unprecedented access to strong and ductile poly(lactic acid) by introducing in situ nanofibrillar poly(butylene succinate) for green packaging. Biomacromolecules 2014, 15, 4054–4064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, S.T.; Hrymak, A.N. Injection molding of polymers and polymer composites. Polymers 2024, 16, 1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, K.; Wei, Y.; Xiong, J.X.; Ni, Y.P.; Wang, X.F.; Xu, Y.J. Simultaneous strengthening and toughening of PLA with full recyclability enabled by resin-microsphere-modified L-lactide oligomers. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 500, 156743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.M.; Liu, S.B.; Yu, E.L.; Wei, Z. Toughening of poly(l-Lactide) with branched polycaprolactone: Effect of chain length. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 29284–29291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, H.; van Heugten, P.M.H.; Veber, A.; Puskar, L.; Anderson, P.D.; Cardinaels, R. Toughening immiscible polymer blends: The role of interface-crystallization-induced compatibilization explored through nanoscale visualization. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 59174–59187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.F.; Chen, H.S.; Yang, T.; Jia, Z.A.; Weaver, J.C.; Shevchenko, P.D.; de Carlo, F.; Mirzaeifar, R.; Li, L. Strategies for simultaneous strengthening and toughening via nanoscopic intracrystalline defects in a biogenic ceramic. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Lv, R.H.; Wang, B.; Na, B.; Liu, H.S. Direct observation of a stereocomplex crystallite network in the asymmetric polylactide enantiomeric blends. Polymer 2018, 143, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.J.; Li, C.X.; Ding, Y.L.; Li, Y.; Li, J.S.; Sun, L.M.; Wei, J.; Wei, X.H.; Wang, H.; Zhang, K.Y.; et al. Fully bio-based and supertough PLA blends via a novel interlocking strategy combining strong dipolar interactions and stereocomplexation. Macromolecules 2022, 55, 5864–5878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Yousfi, R.; Brahmi, M.; Dalli, M.; Achalhi, N.; Azougagh, O.; Tahani, A.; Touzani, R.; El Idrissi, A. Recent Advances in Nanoparticle Development for Drug Delivery: A Comprehensive Review of Polycaprolactone-Based Multi-Arm Architectures. Polymers 2023, 15, 1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Si, J.; Huang, D.; Li, K.; Xin, Y.; Sui, M. Application of star poly(ethylene glycol) derivatives in drug delivery and controlled release. J. Control. Release 2020, 323, 565–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, L.; Yang, A.; Shi, Y.; Liu, J.; Li, X.; Mao, B.; Li, X.; Zhou, F.; Xu, Y. Heterogeneous zinc/catechol-derived resin microsphere-functionalized composite hydrogels with antibacterial and anti-inflammatory activities promote bacterial-infected wound healing. Regen. Biomater. 2025, 12, rbaf081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ASTM D828-22; Standard Test Method for Tensile Properties of Paper and Paperboard Using Constant-Rate-of-Elongation Apparatus. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2022.

- Shuai, C.J.; Zan, J.; Deng, F.; Yang, Y.W.; Peng, S.P.; Zhao, Z.Y. Core–shell-structured ZIF-8@PDA-HA with controllable Zinc Ion release and superior bioactivity for improving a Poly-l-lactic acid scaffold. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 1814–1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.Q.; Luo, F.L.; Mao, J.; Li, Y.T.; Liu, Y.D.; Sun, X.L. The effect of nanocrystalline ZnO with bare special crystal planes on the crystallization behavior, thermal stability and mechanical properties of PLLA. Polym. Test. 2021, 100, 107244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Cruz Faria, É.; Dias, M.L.; Ferreira, L.M.; Tavares, M.I.B. Crystallization behavior of zinc oxide/poly(lactic acid) nanocomposites. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2021, 146, 1483–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, E.W.; Sterzel, H.J.; Wegner, G. Investigation of the Structure of Solution Grown Crystals of Lactide Copolymers by Means of Chemical Reactions. Kolloid-Z. Z. Polym. 1973, 251, 980–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeidlou, S.; Huneault, M.A.; Li, H.; Park, C.B. Poly(lactic acid) crystallization. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2012, 37, 1657–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.X.; Jiang, D.B.; Qin, Y.Y.; Zhang, Z.H.; Yuan, M.W. ZnO-PLLA/PLLA preparation and application in air filtration by electrospinning technology. Polymers 2023, 15, 1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Y.F.; Liang, X.B.; Feng, Y.L.; Shi, L.F.; Chen, R.P.; Guo, J.Z.; Guan, Y. Manipulation of crystallization nucleation and thermal degradation of PLA films by multi-morphologies CNC-ZnO nanoparticles. Carbohydr. Polym. 2023, 320, 121251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sbardella, F.; Martinelli, A.; Di Lisio, V.; Bavasso, I.; Russo, P.; Tirillò, J.; Sarasini, F. Surface modification of basalt fibres with ZnO nanorods and its effect on thermal and mechanical properties of PLA-based composites. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srisuwan, Y.; Srihanam, P.; Rattanasuk, S.; Baimark, Y. Preparation of Poly(L-lactide)-b-poly(ethylene glycol)-b-poly(L-lactide)/Zinc oxide nanocomposite bioplastics for potential use as flexible and antibacterial food packaging. Polymers 2024, 16, 1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Taweel, S.H.; Hassan, S.S.; Ismail, K.M. Eco-friendly zinc-metal-organic framework as a nucleating agent for poly (lactic acid). Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 271, 132691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lizundia, E.; Ruiz-Rubio, L.; Vilas, J.L.; León, L.M. Towards the development of eco-friendly disposable polymers: ZnO-initiated thermal and hydrolytic degradation in poly(l-lactide)/ZnO nanocomposites. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 15660–15669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khadka, A.; Joshi, B.; Samuel, E.; Ojha, D.P.; An, S.; Lee, H.S.; Yoon, S.S. The effect of ZnO–TiO2 fillers on the electroactive phase of PVDF and effective charge separation for fabricating high-performance piezoelectric nanogenerators. Compos. Commun. 2025, 60, 102640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Z.H.; Wang, D.X.; Li, H.L.; Yu, H.L.; Zhou, Y.N.; Yang, B.; Li, Y.L. Reinforcement mechanisms in Core@Shell ZnO/PP composites: Machine learning-driven filler optimization and interfacial engineering strategies for enhanced mechanical performance. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2025, 142, e57819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.Y.; Zhang, Z.X.; Sun, D.X.; Wang, Y. Synchronously enhancing crystallization ability and mechanical properties of the polylactide film via incorporating stereocomplex crystallite fibers. Chin. J. Polym. Sci. 2025, 43, 793–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.L.; Feng, L.H.; Yu, D.M. Formation of stereocomplex crystal and its effect on the morphology and property of PDLA/PLLA Blends. Polymers 2020, 12, 2515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, D.A.L.V.; Marega, F.M.; Pinto, L.A.; Backes, E.H.; Steffen, T.T.; Klok, L.A.; Hammer, P.; Pessan, L.A.; Becker, D.; Costa, L.C. Controlling plasma-functionalized fillers for enhanced properties of PLA/ZnO biocomposites: Effects of excess l-Lactic acid and biomedical implications. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 17, 17965–17978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiran, A.S.K.; Kumar, T.S.S.; Sanghavi, R.; Doble, M.; Ramakrishna, S. Antibacterial and bioactive surface modifications of titanium implants by PCL/TiO2 nanocomposite coatings. Nanomaterials 2018, 8, 860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramaniam, H.; Lim, C.K.; Tey, L.H.; Wong, L.S.; Djearamane, S. Oxidative stress-induced cytotoxicity of HCC2998 colon carcinoma cells by ZnO nanoparticles synthesized from Calophyllum teysmannii. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 30198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, L.; Huang, W.; Zhang, J.; Yu, Y.; Sun, T. Metal-Based Nanoparticles as Antimicrobial Agents: A Review. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2024, 7, 2529–2545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, Y.; Zeng, H.; Ye, X.; Dai, M.; Fang, B.; Liu, L. Zn2+ incorporated composite polysaccharide microspheres for sustained growth factor release and wound healing. Mater. Today Bio 2023, 22, 100739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Liu, X.; Tan, L.; Cui, Z.; Yang, X.; Liang, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhu, S.; Zheng, Y.; Yeung, K.W.K.; et al. Zinc-doped Prussian blue enhances photothermal clearance of Staphylococcus aureus and promotes tissue repair in infected wounds. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arrabito, G.; Prestopino, G.; Medaglia, P.G.; Ferrara, V.; Sancataldo, G.; Cavallaro, G.; Di Franco, F.; Scopelliti, M.; Pignataro, B. Freestanding cellulose acetate/ZnO flowers composites for solar photocatalysis and controlled zinc ions release. Colloid Surf. Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2024, 698, 134526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voorhis, C.; González-Benito, J.; Kramar, A. “Nano in Nano”—Incorporation of ZnO Nanoparticles into Cellulose Acetate–Poly(Ethylene Oxide) Composite Nanofibers Using Solution Blow Spinning. Polymers 2024, 16, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, W.J.; Pejak Simunec, D.; Trinchi, A.; Kyratzis, I.; Li, Y.C.; Wright, P.; Shen, S.; Sola, A.; Wen, C. Advancing the additive manufacturing of PLA-ZnO nanocomposites by fused filament fabrication. Virtual Phys. Prototyp. 2024, 19, e2285418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazkooh, H.K.; Sadhu, A.; Liu, K.F. Vibration-based energy harvesting in large-scale civil infrastructure: A comprehensive outlook of current technologies and future prospects. Discov. Civ. Eng. 2025, 2, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.J.; Min, J.; Zhang, J.W.; Luo, M.N.; Wang, T.; Fu, Q.; Zhang, J. Enhancing the stereocomplex crystallization of PLLA/PDLA symmetric blend by controlling the degree of molecular chain entanglement. Polymer 2024, 313, 127740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Yang, J.; Zhang, T.R.; Li, L. Achieving PLA with excellent heat resistance and transparency via synergistic nucleation effect assisted by hydrogen bonding. ACS Macro Lett. 2025, 14, 1352–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srinivas, V.; Bertella, F.; van Hooy-Corstjens, C.S.J.; Leeuwen, B.v.; Craenmehr, E.G.M.; Cavallo, D.; Rastogi, S.; Harings, J.A.W. Interfacial stereocomplexation in heterogeneous polymer powder formulations for reinforcing (laser) sintered welds. Addit. Manuf. 2020, 36, 101665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx, B.; Bostan, L.; Herrmann, A.S.; Boskamp, L.; Koschek, K. Properties of stereocomplex PLA for melt spinning. Polymers 2023, 15, 4510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Run | Polymer | Ratio of Initiator | Monomer b | Avg. MW c (×104) | T5% c (°C) | Tmax d (°C) | ΔHm d (J/g) | Xc d (%) | Yield Strength (MPa) | Elongation at Break (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Zn/CFR1-PLLA | 1 wt% | L-LA | 13.6 | 292.2 | 334.3 | 36 | 38.5 | 16.5 ± 0.8 | 17.2 ± 0.8 |

| 2 | Zn/CFR2-PLLA | 2 wt% | L-LA | 8.5 | 297.4 | 326.8 | 40.5 | 43.2 | 18.6 ± 0.9 | 20.2 ± 1.1 |

| 3 | Zn/CFR4-PLLA | 4 wt% | L-LA | 3.4 | 304.3 | 324.5 | 39.8 | 42.5 | 12.5 ± 0.6 | 8.7 ± 0.4 |

| 4 | Zn/CFR8-PLLA | 8 wt% | L-LA | 1.2 | 287.5 | 318.5 | 38.2 | 40.8 | 7.2 ± 0.4 | 4.2 ± 0.2 |

| 5 | Zn/CFR1-PDLA | 1 wt% | D-LA | 14.5 | 281.3 | 300.4 | 35.7 | 38.1 | 14.5 ± 0.7 | 16.5 ± 0.8 |

| 6 | Zn/CFR2-PDLA | 2 wt% | D-LA | 8.6 | 284.4 | 306.5 | 39.8 | 42.5 | 19.1 ± 1.0 | 21.6 ± 0.9 |

| 7 | Zn/CFR4-PDLA | 4 wt% | D-LA | 5.0 | 293.8 | 312.2 | 37.9 | 40.5 | 11.8 ± 0.5 | 7.8 ± 0.4 |

| 8 | Zn/CFR8-PDLA | 8 wt% | D-LA | 1.3 | 297.3 | 316.3 | 37.2 | 39.7 | 6.5 ± 0.3 | 3.5 ± 0.2 |

| Sample b | Tg (°C) | Tm (°C) | Tcc (°C) | ΔHc (J/g) | Xc (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neat PLLA | 60.0 | 175 | 131.6 | 28.3 | 30.2 |

| (Zn/CFR2-PLLA)1/PLLA | 59.0 | 172 | 125.0 | 39.8 | 42.5 |

| (Zn/CFR2-PLLA)2/PLLA | 59.5 | 171 | 122.3 | 41.5 | 44.3 |

| (Zn/CFR2-PLLA)4/PLLA | 59.9 | 170 | 124.8 | 40.9 | 43.7 |

| (Zn/CFR2-PLLA)8/PLLA | 59.8 | 168 | 123.3 | 37.9 | 40.4 |

| (Zn/CFR2-PDLA)1/PLLA | 57.1 | 217 | 123.0 | 43.9 | 46.9 |

| (Zn/CFR2-PDLA)2/PLLA | 56.1 | 219 | 122.7 | 44.8 | 47.8 |

| (Zn/CFR2-PDLA)4/PLLA | 60.1 | 220 | 122.1 | 46.2 | 49.3 |

| (Zn/CFR2-PDLA)8/PLLA | 61.5 | 221 | 121.4 | 46.7 | 49.8 |

| Material | E. coli Inhibition Rate | S. aureus Inhibition Rate |

|---|---|---|

| Blank control sample | 0% | 0% |

| (Zn/CFR2-PLLA)2/PLLA | 98.3 ± 0.3% | 98.1 ± 0.4% |

| (Zn/CFR2-PDLA)2/PLLA | 99.1 ± 0.2% | 98.6 ± 0.3% |

| Samples | Tensile Strength (MPa) | Tensile Modulus (GPa) | Fracture Elongation (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neat PLLA (Zn/CFR2-PLLA)1/PLLA (Zn/CFR2-PLLA)2/PLLA | 67.7 ± 0.7 | 2.73 ± 0.1 | 14.9 ± 1.4 |

| 83.2 ± 1.2 | 3.15 ± 0.2 | 9.8 ± 0.6 | |

| 105.4 ± 2.5 | 3.89 ± 0.3 | 7.2 ± 0.4 | |

| (Zn/CFR2-PLLA)4/PLLA (Zn/CFR2-PLLA)8/PLLA | 92.7 ± 1.8 | 4.02 ± 0.2 | 5.1 ± 0.3 |

| 85.1 ± 2.1 | 4.15 ± 0.3 | 3.9 ± 0.2 | |

| (Zn/CFR2-PDLA)1/PLLA (Zn/CFR2-PDLA)2/PLLA (Zn/CFR2-PDLA)4/PLLA | 112.3 ± 2.7 | 4.33 ± 0.3 | 7.9 ± 0.6 |

| 128.6 ± 3.1 | 4.51 ± 0.4 | 6.5 ± 0.5 | |

| 115.8 ± 2.5 | 4.68 ± 0.3 | 5.2 ± 0.4 | |

| (Zn/CFR2-PDLA)8/PLLA | 98.4 ± 2.3 | 4.85 ± 0.4 | 4.1 ± 0.3 |

| Fiber | Moisture Regain (%) | Equilibrium Moisture Absorption Time (min) | Capillary Effect Height (mm/10 min) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neat PLLA (Zn/CFR2-PLLA)2/PLLA (Zn/CFR2-PDLA) 2/PLLA | 0.49 ± 0.03 | 125 ± 8 | 7.5 ± 0.6 |

| 0.73 ± 0.05 | 78 ± 4 | 16.2 ± 1.3 | |

| 0.58 ± 0.04 | 92 ± 5 | 12.8 ± 1.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhao, L.; Liu, N.; Shi, Y.-L.; Zhang, K.; Xu, Y.-J.; Pan, Y. Reinforced, Toughened, and Antibacterial Polylactides Facilitated by Multi-Arm Zn/Resin Microsphere-Based Polymers. J. Compos. Sci. 2026, 10, 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs10020075

Zhao L, Liu N, Shi Y-L, Zhang K, Xu Y-J, Pan Y. Reinforced, Toughened, and Antibacterial Polylactides Facilitated by Multi-Arm Zn/Resin Microsphere-Based Polymers. Journal of Composites Science. 2026; 10(2):75. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs10020075

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Longchen, Na Liu, Yu-Lei Shi, Kaitao Zhang, Ying-Jun Xu, and Yu Pan. 2026. "Reinforced, Toughened, and Antibacterial Polylactides Facilitated by Multi-Arm Zn/Resin Microsphere-Based Polymers" Journal of Composites Science 10, no. 2: 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs10020075

APA StyleZhao, L., Liu, N., Shi, Y.-L., Zhang, K., Xu, Y.-J., & Pan, Y. (2026). Reinforced, Toughened, and Antibacterial Polylactides Facilitated by Multi-Arm Zn/Resin Microsphere-Based Polymers. Journal of Composites Science, 10(2), 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs10020075