The Impact of Sports Drink Exposure on the Colour Stability of Restorative Materials: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy and Data Extraction

| Parameter | Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Dental composite or glass ionomer samples | Samples from other dental materials |

| Intervention | Exposure to sports drinks | |

| Comparison | Not applicable | |

| Outcomes | Determined colourimetric parameters | Determined other technical or mechanical parameters |

| Study design | In vitro studies | Other original articles, literature reviews, case reports, letters to the editor, conference reports |

| Published after 1 January 2005 | Not published in English |

2.2. Data Synthesis and Analysis

2.3. Quality Assessment and Critical Appraisal for the Systematic Review of Included Studies

3. Results

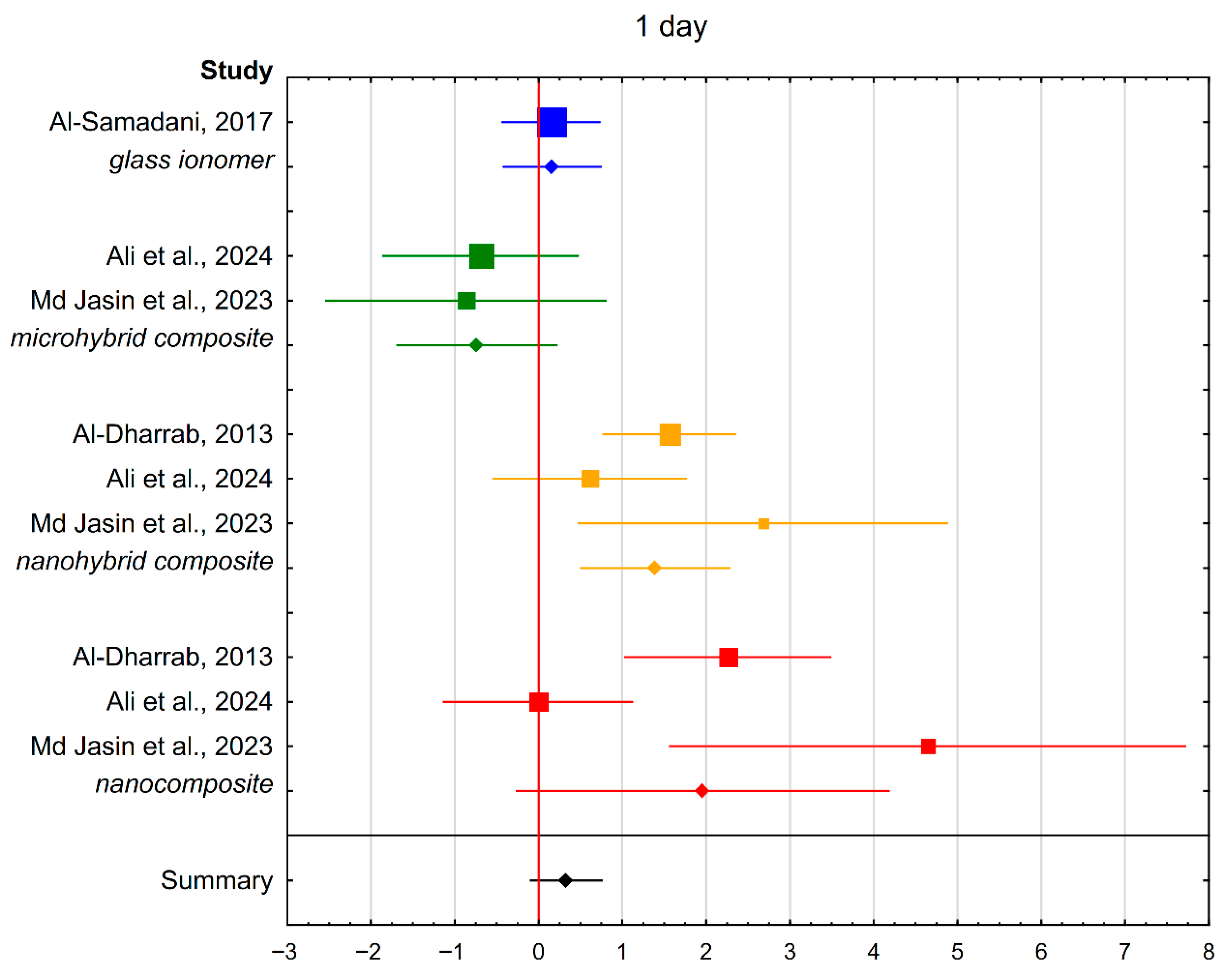

3.1. One-Day Exposure

3.2. One-Week Exposure

3.3. One-Month Exposure

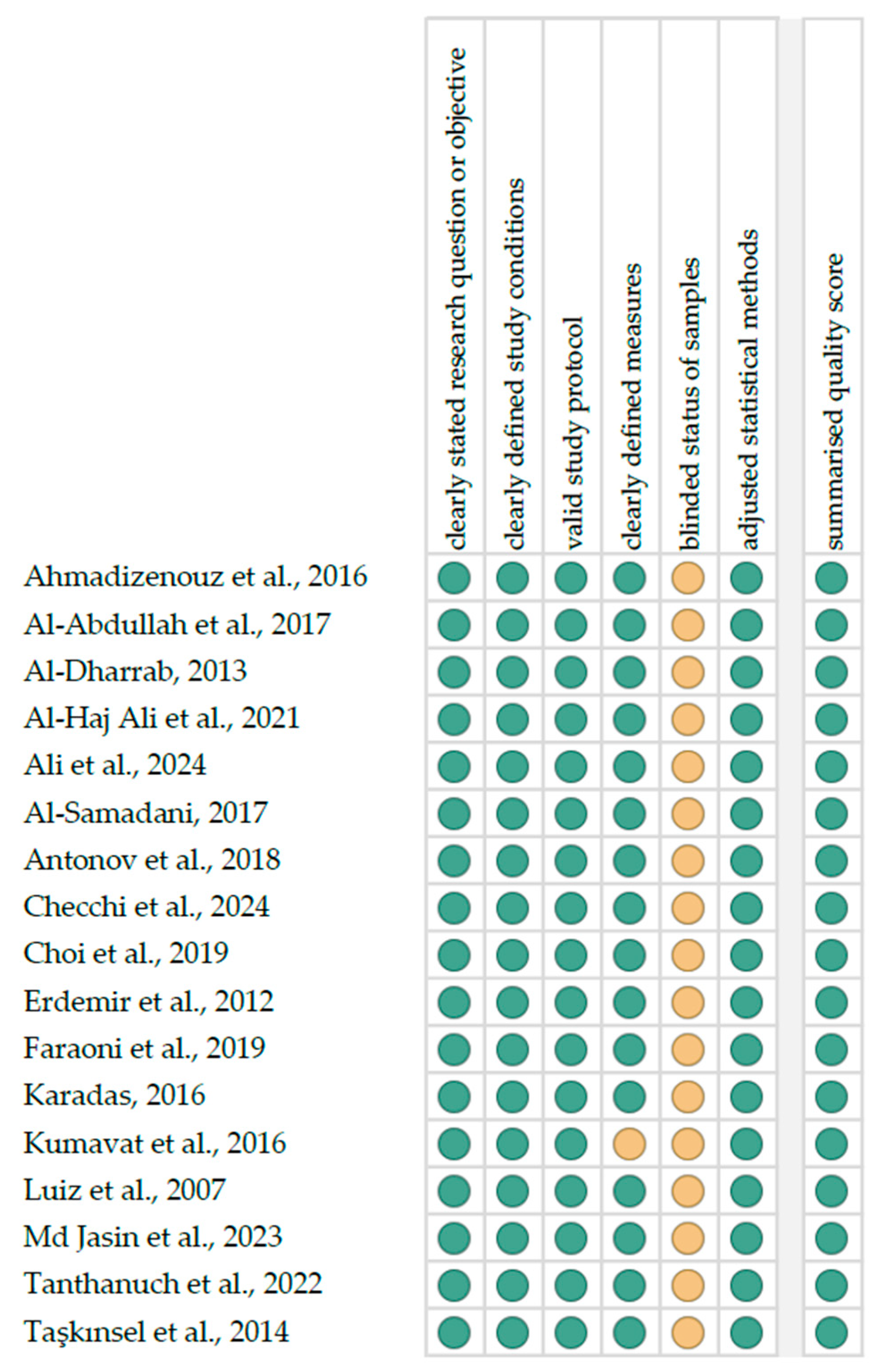

3.4. Quality Assessment and Critical Appraisal for the Systematic Review of the Included Studies

4. Discussion

4.1. Narrative Synthesis of Findings

4.2. Technical Implications of Material Compositions and Properties

4.3. Strengths and Limitations

4.4. Clinical Implications and Future Research Directions

5. Conclusions

- •

- Prolonged exposure to sports drinks causes a clear, time-dependent increase in the colour change of dental restorative materials, with exposure duration being the dominant factor in discolouration.

- •

- Short-term (one-day) exposure does not produce statistically significant overall discolouration; however, early material-dependent differences indicate variable initial susceptibility.

- •

- After one week and one month of exposure, colour changes become significant and more pronounced across materials.

- •

- Composite resins, particularly microhybrid and nanocomposite types, demonstrate greater colour instability during extended exposure compared with glass ionomer materials.

- •

- Over longer exposure periods, the influence of material composition diminishes, suggesting that sustained contact with acidic sports drinks outweighs inter-material differences.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kanzow, P.; Wegehaupt, F.J.; Attin, T.; Wiegand, A. Etiology and Pathogenesis of Dental Erosion. Quintessence Int. 2016, 47, 275–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donovan, T.; Nguyen-Ngoc, C.; Abd Alraheam, I.; Irusa, K. Contemporary Diagnosis and Management of Dental Erosion. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2021, 33, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inchingolo, A.M.; Malcangi, G.; Ferrante, L.; Del Vecchio, G.; Viapiano, F.; Mancini, A.; Inchingolo, F.; Inchingolo, A.D.; Di Venere, D.; Dipalma, G.; et al. Damage from Carbonated Soft Drinks on Enamel: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, J.; Huang, B. Awareness and Knowledge of Dental Erosion and Its Association with Beverage Consumption: A Multidisciplinary Survey. BMC Oral Health 2022, 22, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Søvik, J.B.; Skudutyte-Rysstad, R.; Tveit, A.B.; Sandvik, L.; Mulic, A. Sour Sweets and Acidic Beverage Consumption Are Risk Indicators for Dental Erosion. Caries Res. 2015, 49, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijakowski, K.; Walerczyk-Sas, A.; Surdacka, A. Regular Physical Activity as a Potential Risk Factor for Erosive Lesions in Adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijakowski, K.; Zdrojewski, J.; Nowak, M.; Podgórski, F.; Surdacka, A. Regular Physical Activity and Dental Erosion: A Systematic Review. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picos, A.; Chisnoiu, A.; Dumitrasc, D.L. Dental Erosion in Patients with Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. Adv. Clin. Exp. Med. 2013, 22, 303–307. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lan, Z.; Zhao, I.S.; Li, J.; Li, X.; Yuan, L.; Sha, O. Erosive Effects of Commercially Available Alcoholic Beverages on Enamel. Dent. Mater. J. 2023, 42, 236–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, K.; Qadir, A.; Trakman, G.; Aziz, T.; Khattak, M.; Nabi, G.; Alharbi, M.; Alshammari, A.; Shahzad, M. Sports and Energy Drink Consumption, Oral Health Problems and Performance Impact among Elite Athletes. Nutrients 2022, 14, 5089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antunes, L.S.; Veiga, L.; Nery, V.S.; Nery, C.C.; Antunes, L.A. Sports Drink Consumption and Dental Erosion among Amateur Runners. J. Oral Sci. 2017, 59, 639–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podgórski, F.; Musyt, W.; Nijakowski, K. The Impact of Sports Drink Exposure on the Surface Roughness of Restorative Materials: A Systematic Review. J. Compos. Sci. 2025, 9, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, C.E.; Silva-Acevedo, C.A.; Padilla-Orellana, F.; Zero, D.; Carvalho, T.S.; Lussi, A. Should We Wait to Brush Our Teeth? A Scoping Review Regarding Dental Caries and Erosive Tooth Wear. Caries Res. 2024, 58, 454–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdemir, U.; Yıldız, E.; Eren, M.M. Effects of Sports Drinks on Color Stability of Nanofilled and Microhybrid Composites after Long-Term Immersion. J. Dent. 2012, 40, e55–e63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarac, D.; Sarac, Y.S.; Kulunk, S.; Ural, C.; Kulunk, T. The Effect of Polishing Techniques on the Surface Roughness and Color Change of Composite Resins. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2006, 96, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ergücü, Z.; Türkün, L.S.; Aladag, A. Color Stability of Nanocomposites Polished with One-Step Systems. Oper. Dent. 2008, 33, 413–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Haj Ali, S.N.; Alsulaim, H.N.; Albarrak, M.I.; Farah, R.I. Spectrophotometric Comparison of Color Stability of Microhybrid and Nanocomposites Following Exposure to Common Soft Drinks among Adolescents: An in Vitro Study. Eur. Arch. Paediatr. Dent. 2021, 22, 675–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.; Meena, A.; Patnaik, A. Biomaterials for Dental Composite Applications: A Comprehensive Review of Physical, Chemical, Mechanical, Thermal, Tribological, and Biological Properties. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2022, 33, 1762–1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanthanuch, S.; Kukiattrakoon, B.; Thongsroi, T.; Saesaw, P.; Pongpaiboon, N.; Saewong, S. In Vitro Surface and Color Changes of Tooth-Colored Restorative Materials after Sport and Energy Drink Cyclic Immersions. BMC Oral Health 2022, 22, 578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taşkinsel, E.; Özel, E.; Öztürk, E. Effects of Sports Beverages and Polishing Systems on Color Stability of Different Resin Composites. J. Conserv. Dent. 2014, 17, 325–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faris, T.M.; Abdulrahim, R.H.; Mahmood, M.A.; Mhammed Dalloo, G.A.; Gul, S.S. In Vitro Evaluation of Dental Color Stability Using Various Aesthetic Restorative Materials after Immersion in Different Drinks. BMC Oral Health 2023, 23, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kose, H.D.; Giray, I.; Boyacioglu, H.; Turkun, L.S. Can Energy Drinks Affect the Surface Quality of Bioactive Restorative Materials? BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Study Quality Assessment Tools|NHLBI, NIH. Available online: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools (accessed on 7 November 2024).

- Ahmadizenouz, G.; Esmaeili, B.; Ahangari, Z.; Khafri, S.; Rahmani, A. Effect of Energy Drinks on Discoloration of Silorane and Dimethacrylate-Based Composite Resins. J. Dent. 2016, 13, 261–270. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Abdullah, A.S.; Al-Bounni, R.S.; Al-Omari, M. Color Stability of Tetric® N-Ceram Bulk Fill Restorative Composite Resin after Immersion in Different Drinks. J. Adv. Oral Res. 2017, 8, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Dharrab, A. Effect of Energy Drinks on the Color Stability of Nanofilled Composite Resin. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 2013, 14, 704–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, S.A.-H.; Alsedrani, R.; Alharbi, N.; Farah, R.; Alharbi, E.; Alkhuwaiter, S. Impact of Carbonated Beverages on Color Stability and Home Bleaching Efficacy of BulkFill Composite Resins. Pediatr. Dent. 2024, 46, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Al-Samadani, K.H. Glass Ionomer Restorative Materials Response to Its Color Stability with Effect of Energy Beverages. World J. Dent. 2017, 8, 255–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonov, M.; Lenhardt, L.; Manojlović, D.; Milićević, B.; Dramićanin, M.D. Discoloration of Resin Based Composites in Natural Juices and Energy Drinks. Vojnosanit. Pregl. 2018, 75, 787–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Checchi, V.; Forabosco, E.; Della Casa, G.; Kaleci, S.; Giannetti, L.; Generali, L.; Bellini, P. Color Stability Assessment of Single- and Multi-Shade Composites Following Immersion in Staining Food Substances. Dent. J. 2024, 12, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.-W.; Lee, M.-J.; Oh, S.-H.; Kim, K.-M. Changes in the Physical Properties and Color Stability of Aesthetic Restorative Materials Caused by Various Beverages. Dent. Mater. J. 2019, 38, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraoni, J.J.; Quero, I.B.; Schiavuzzo, L.S.; Palma-Dibb, R.G. Color Stability of Nanohybrid Composite Resins in Drinks. Braz. J. Oral Sci. 2019, 18, e191601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karadas, M. The Effect of Different Beverages on the Color and Translucency of Flowable Composites. Scanning 2016, 38, 701–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumavat, V.; Raghvendra, S.S.; Vyavahare, N.; Khare, U.; Kotadia, P. Effect of Alcoholic and Non-Alcoholic Beverages on Color Stability, Surface Roughness and Fracture Toughness of Resin Composites: An in Vitro Study. IIOAB J. 2016, 7, 48–54. [Google Scholar]

- Luiz, B.K.M.; Amboni, R.D.M.C.; Prates, L.H.M.; Roberto Bertolino, J.; Pires, A.T.N. Influence of Drinks on Resin Composite: Evaluation of Degree of Cure and Color Change Parameters. Polym. Test. 2007, 26, 438–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Md Jasin, N.; Roslan, H.; Mohamad Suhaimi, F.; Omar, A.F.; Bahoudela, N. Influences of Different Solutions on the Colour Stability and Microhardness of Contemporary Light Cured Composites: An in Vitro Study. JUMMEC 2023, 2023, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, G.F.; Cardoso, M.B. Effects of Carbonated Beverages on Resin Composite Stability. Am. J. Dent. 2018, 31, 313–316. [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann, A.; Nijakowski, K.; Jankowski, J.; Donnermeyer, D.; Ramos, J.C.; Drobac, M.; Martins, J.F.B.; Hatipoğlu, Ö.; Omarova, B.; Javed, M.Q.; et al. Clinical Difficulties Related to Direct Composite Restorations: A Multinational Survey. Int. Dent. J. 2025, 75, 797–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehmann, A.; Nijakowski, K.; Jankowski, J.; Donnermeyer, D.; Palma, P.J.; Drobac, M.; Martins, J.F.B.; Pertek Hatipoğlu, F.; Tulegenova, I.; Javed, M.Q.; et al. Awareness of Possible Complications Associated with Direct Composite Restorations: A Multinational Survey among Dentists from 13 Countries with Meta-Analysis. J. Dent. 2024, 145, 105009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Database | Search Query |

|---|---|

| PubMed | (“soft drink” OR “sport drink” OR “sports drink” OR “sport beverage” OR “sports beverage” OR “fruit juice” OR “isotonic beverage” OR “energy beverage” OR “isotonic drink” OR “energy drink”) AND (“dental material” OR “restorative material” OR “composite” OR “glass-ionomer” OR “compomer”) |

| Scopus | TITLE-ABS-KEY ((“soft drink” OR “sport drink” OR “sports drink” OR “sport beverage” OR “sports beverage” OR “fruit juice” OR “isotonic beverage” OR “energy beverage” OR “isotonic drink” OR “energy drink”) AND (“dental material” OR “restorative material” OR “composite” OR “glass-ionomer” OR “compomer”)) |

| Web of Science | TS = ((“soft drink” OR “sport drink” OR “sports drink” OR For Web of Science: TS = ((“soft drink” OR “sport drink” OR “sports drink” OR “sport beverage” OR “sports beverage” OR “fruit juice” OR “isotonic beverage” OR “energy beverage” OR “isotonic drink” OR “energy drink”) AND (“dental material” OR “restorative material” OR “composite” OR “glass-ionomer” OR “compomer”)); “sport beverage” OR “sports beverage” OR “fruit juice” OR “isotonic beverage” OR “energy beverage” OR “isotonic drink” OR “energy drink”) AND (“dental material” OR “restorative material” OR “composite” OR “glass-ionomer” OR “compomer”)) |

| Embase | (“soft drink”: ti,ab,kw OR “sport drink”: ti,ab,kw OR “sports drink”: ti,ab,kw OR “sport beverage”: ti,ab,kw OR “sports beverage”: ti,ab,kw OR “fruit juice”: ti,ab,kw OR “isotonic beverage”: ti,ab,kw OR “energy beverage”: ti,ab,kw For Embase: (“soft drink”: ti,ab,kw OR “sport drink”: ti,ab,kw OR “sports drink”: ti,ab,kw OR “sport beverage”: ti,ab,kw OR “sports beverage”: ti,ab,kw OR “fruit juice”: ti,ab,kw OR “isotonic beverage”: ti,ab,kw OR “energy beverage”: ti,ab,kw OR “isotonic drink”: ti,ab,kw OR “energy drink”: ti,ab,kw) AND (“dental material”: ti,ab,kw OR “restorative material”: ti,ab,kw OR “composite”: ti,ab,kw OR “glass-ion omer”: ti,ab,kw OR “compomer”: ti,ab,kw). OR “isotonic drink”: ti,ab,kw OR “energy drink”: ti,ab,kw) AND (“dental material”: ti,ab,kw OR “restorative material”: ti,ab,kw OR “composite”: ti,ab,kw OR “glass ionomer”: ti,ab,kw OR “compomer”: ti,ab,kw) |

| Study | Test Group | Control Group | Test Materials | Test Beverages | Control Beverage | Exposure Protocol | Exposure Duration | Outcome Measure | Evaluation Methods | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ahmadizenouz et al., 2016 [25] | 60 | 30 | Composites (n = 60): Filtek Z250 (n = 30), Filtek Z350 XT (n = 30); Silorane (n = 30): Filtek P90 (n = 30) | Red Bull (n = 30), Hype (n = 30) | Artificial saliva | 5 min daily, then stored in artificial saliva | 7 days, 30 days | ∆E | Spectrophotometer (Vita Easyshade, Vident, Brea, CA, USA) | The Filtek Z250 composite showed the highest ∆E irrespective of the solution at both time points. After seven days and one month, the lowest ∆E values were observed in the Filtek Z350XT and Filtek P90 composites immersed in artificial saliva, respectively. |

| Al-Abdullah et al., 2017 [26] | 20 | 10 | Composites: Tetric N-Ceram (n = 30) | Red Bull (n = 10), Zero Carb ISOPURE (n = 10) | Distilled water | Continuous exposure | 7 days | ∆E | Spectrophotometer (Color Eye 7000A) | The colour change of the N-Ceram Bulk Fill composite specimens ∆E occurred by immersion in the energy drinks; protein supplement solution after seven days was found to be statistically significant. |

| Al-Dharrab, 2013 [27] | 180 | 60 | Composites: Filtek Z250 XT (n = 80), Filtek Z350XT (n = 80), Tetric EvoCeram (n = 80) | Red Bull (n= 60), Bison (n= 60), Power Horse (n= 60) | Distilled water | Continuous exposure | 1, 7, 30, 60 days | ∆E | Colorimeter (Konica Minolta CR-400/410; Minolta Co., Osaka, Japan) | The colour change ∆E caused by the energy drinks was significantly different for all tested materials at all four times except in the Red Bull group. The highest total colour difference ∆E was found in the Red Bull group after 60 days. |

| Al-Haj Ali et al., 2021 [17] | 18 | 18 | Composites: Filtek Z250 (n = 12), Filtek Z350 (n = 12), Tetric N-Ceram (n = 12) | Red Bull (n = 18) | Distilled water | Continuous exposure | 15 days | ∆E | VITA EasyShade spectrophotometer (VITA Zahnfabrik GmbH, Bad Säckingen, Germany) | Significant change in colour values and total colour (ΔE > 3.3) was observed in the composite materials after immersion in the soft drinks compared to immersion in distilled water (ΔE < 3.3). The highest mean values were those of Filtek Z350, being significantly different from the rest of the materials. |

| Ali et al., 2024 [28] | 18 | 18 | Composites: Filtek Z250 (n = 12), Filtek One Bulk Fill (n = 12), Tetric N-Ceram (n = 12) | Monster Energy (n = 18) | Distilled water | Continuous exposure | 1 day, 1 week, 2 months | ∆E | VITA EasyShade spectrophotometer (VITA Zahnfabrik GmbH, Bad Säckingen, Germany) | All tested composite resins exhibited unacceptable discolouration (ΔE > 3.3) after two months in carbonated beverages. Filtek One Bulk Fill and Filtek Z250 displayed the most significant discolouration, particularly when immersed in the malt drink. |

| Al-Samadani, 2017 [29] | 45 | 15 | Glass ionomers: GC Equia (n = 20), Kerac Molar (n = 20), Ionofil Plus AC (n = 20) | Red Bull (n = 15), Code Red (n = 15), Power Horse (n = 15) | Distilled water | Continuous exposure | 1 day, 1 week, 1 month | ∆E | Colourimeter (Konica Minolta CR-400/410; Minolta Co., Osaka, Japan) | The energy beverages affected the colour stability of the tested GI restorative materials with increasing aging time. The effect on the colour stability of GI was influenced by factors, such as the type of solution and the presence of acids causing erosion. |

| Antonov et al., 2018 [30] | 20 | n/a | Composites: Gradia Direct (n = 20) | Red Bull (n = 5), Guarana Kick (n = 5), Energi-s (n = 5), Burn (n = 5) | n/a | Continuous exposure | 7 days | ∆E | Spectrophotometer Thermo Evolution 600 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) | Change in colour and fluorescence appeared differently with various solutions due to different chemical composition and concentration of colourant species in the different beverages. Solutions with higher optical absorption induced higher total colour change. |

| Checchi et al., 2024 [31] | 60 | 60 | Composites: ONEshade (n = 60), OlicoXP (n = 60) | Monster Energy (n = 60) | Artificial saliva | Continuous exposure | 7 days, 30 days | ∆E | VITA EasyShade spectrophotometer (VITA Zahnfabrik GmbH, Bad Säckingen, Germany) | Single-shade composites showed statistically significant differences in colour change from the energy drink than the multi-shade composites, showing a higher discolouration potential. The polymerisation time did not have significative effects on colour stability. |

| Choi et al., 2019 [32] | 5 | 5 | Composites: Filtek Z250 (n = 10) | Hot6 (n = 5) | Distilled water | 3 h daily, then stored in distilled water | 5 days | ∆E | Spectrophotometer (CM3500-d, Minolta, Tokyo, Japan) | For the resin composite after the 5th day, the colour changes between the water of the control group and the energy drink of the experimental group were significant. |

| Erdemir et al., 2012 [14] | 84 | 28 | Composites: Filtek Z250 (n = 28), Filtek Supreme (n = 28), Clearfil Majesty Posterior (n = 28), Clearfil APX (n = 28) | Red Bull (n = 28), Powerade (n = 28), Burn (n = 28) | Distilled water | 2 min daily, then stored in distilled water | 1 month, 6 months | ∆E | Spectrophotometer (Color Eye 7000; Gretag-Macbeth, NY, USA) | All the test solutions used in the study caused greater discolouration than the clinically acceptable level of threshold (∆E < 3.3) over the 6-month evaluation period except for Clearfil Majesty Posterior immersed in distilled water (2.91 ± 0.28). The effect of each solution on the colour stability of the composite materials depended on the type of solution, exposure time, and composition of the composite material. |

| Faraoni et al., 2019 [33] | 10 | 10 | Composites: Filtek Z350 XT (n = 20) | Gatorade (n = 10) | Artificial saliva | 4 × 5 min daily, then stored in artificial saliva | 15 days | ∆E | Spectrophotometer (Color guide 45/0, PCB 6807 BYK-Gardner GmbH, Geretsried, Bavaria, Germany) | The lemon flavour isotonic drink was the solution that most affected the specimens, making them clearer, which was a statistically significant difference from the other solutions studied. |

| Karadas, 2016 [34] | 25 | 25 | Composites: Filtek Z250 (n = 10), G-aenial Universal Flo (n = 10), Filtek Ultimate (n = 10), Esthelite Flow Quick (n = 10), Clearfil Majesty ES Flow (n = 10) | Red bull (n = 25) | Distilled water | Continuous exposure | 7 days | ∆E | Spectrophotometer (VITA Easyshade Advance, Zahnfabrik, Bad Säckingen, Germany) | The colour changes were significantly different among the composite materials after immersion in beverages. Filtek Ultimate and Esthelite Flow Quick exhibited less discolouration than G-aenial Universal Flo and Clearfil Majesty ES Flow. No significant difference was found between Filtek Z-250 and either Filtek Ultimate or Esthelite Flow Quick. |

| Kumavat et al., 2016 [35] | 20 | n/a | Composites: G-aenial (n = 10), Tetric N-Ceram (n = 10) | Red Bull (n = 20) | n/a | 10 min daily, then stored in distilled water | 7, 14, 28 days | ∆E | Spectrophotometer, Spectrolino (Gretag Macbeth AG, Germany) | The UDMA-based composite (G-aenial) presented higher discolouration in the energy drink than the Bis GMA-based composite (Tetric N-Ceram). |

| Luiz et al., 2007 [36] | 5 | 5 | Composites: Charisma (n = 10) | Gatorade (n = 5) | Distilled water | Continuous exposure | 7 days | ∆E | Spectrophotometer (Konica Minolta colorimeter, Japan) | For the composite specimens immersed in the sports drink, the ∆E values indicated that the colour changes were not appreciable by the human eye (∆E < 1). |

| Md Jasin et al., 2023 [37] | 30 | 10 | Composites: Filtek Z250 (n = 10), Filtek Z250XT (n = 10), Filtek Z350 XT (n = 10) | 100Plus (n = 30) | Artificial saliva | Continuous exposure | 1, 7, 14, 21, 28 days | ∆E | QE65000 Spectrometer (Ocean Optic, Dunedine, FL, USA) | There was a significant difference in discolouration between all three types of composite resins when immersed in all solutions regardless of the pH values. |

| Tanthanuch et al., 2022 [19] | 96 | 48 | Composites: Filtek One Bulk Fill (n = 48), Premise (n = 48); Glass ionomers: Ketac Universal (n = 48) | Sponsor (n = 48), M-150 (n = 48) | Distilled water | 5s in test beverage followed by 5s in artificial saliva—repeated x24, then stored in artificial saliva; repeated daily | 7 day, 14 days | ∆E | Spectrophotometer (ColorQuest XE, Hunter Associates Laboratory, Inc., Reston, VA, USA) | After immersion, the glass ionomer restorative material had statistically more colour changes than the others. The energy drink groups statistically caused more surface and colour changes than the sports drink groups. |

| Taşkınsel et al., 2014 [20] | 64 | 32 | Composites: Clearfil APX (n = 48), Cavex Quadrant Universal (n = 48) | Powerade (n = 32), Buzzer (n = 32) | Distilled water | 3 × 5 min daily, then stored in distilled water | 7 days | ∆E | Spectrophotometer (Vita Easyshade, Vident, Brea, CA, USA) | Significant differences were found between the mean ∆E values of the groups after seven days of immersion. The highest level of the mean colour change was observed in the Clearfil APX specimens immersed in Powerade (∆E = 3.5 ± 0.9). |

| Study | SMD | SE | −95CI | +95CI | p-Value | Weight [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al-Samadani, 2017 | 0.16 | 0.30 | −0.43 | 0.74 | 0.602 | 100.00 |

| glass ionomer | 0.16 | 0.30 | −0.43 | 0.74 | 0.602 | 100.00 |

| Ali et al., 2024 | −0.69 | 0.59 | −1.85 | 0.48 | 0.249 | 67.37 |

| Md Jasin et al., 2023 | −0.86 | 0.85 | −2.53 | 0.81 | 0.313 | 32.63 |

| microhybrid composite | −0.74 | 0.49 | −1.70 | 0.21 | 0.128 | 100.00 |

| Al-Dharrab, 2013 | 1.57 | 0.40 | 0.77 | 2.36 | <0.001 * | 51.10 |

| Ali et al., 2024 | 0.62 | 0.59 | −0.54 | 1.77 | 0.297 | 35.12 |

| Md Jasin et al., 2023 | 2.68 | 1.13 | 0.48 | 4.89 | 0.017 * | 13.78 |

| nanohybrid composite | 1.39 | 0.46 | 0.49 | 2.28 | 0.002 * | 100.00 |

| Al-Dharrab, 2013 | 2.27 | 0.63 | 1.03 | 3.50 | <0.001 * | 37.88 |

| Ali et al., 2024 | 0.00 | 0.58 | −1.13 | 1.13 | >0.999 | 38.58 |

| Md Jasin et al., 2023 | 4.65 | 1.57 | 1.57 | 7.73 | 0.003 * | 23.55 |

| nanocomposite | 1.95 | 1.14 | −0.27 | 4.18 | 0.086 | 100.00 |

| Summary (random effects) | 0.32 | 0.22 | −0.10 | 0.75 | 0.138 | |

| Intergroup comparison | 0.006 * | |||||

| Egger’s test | 0.344 |

| Study | SMD | SE | −95CI | +95CI | p-Value | Weight [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al-Samadani, 2017 | 1.27 | 0.32 | 0.64 | 1.89 | <0.001 * | 50.55 |

| Tanthanuch et al., 2022 | 41.23 | 4.22 | 32.96 | 49.50 | <0.001 * | 49.45 |

| glass ionomer | 21.03 | 19.98 | −18.13 | 60.18 | 0.293 | 100.00 |

| Ahmadizenouz et al., 2016 | 3.15 | 0.56 | 2.05 | 4.25 | <0.001 * | 14.59 |

| Ali et al., 2024 | 0.70 | 0.59 | −0.47 | 1.87 | 0.239 | 14.20 |

| Checchi et al., 2024 | 2.04 | 0.22 | 1.60 | 2.48 | <0.001 * | 17.90 |

| Karadas, 2016 | −0.41 | 0.64 | −1.66 | 0.84 | 0.522 | 13.69 |

| Luiz et al., 2007 | 2.24 | 0.81 | 0.66 | 3.82 | 0.006 * | 11.81 |

| Md Jasin et al., 2023 | −0.79 | 0.85 | −2.45 | 0.87 | 0.353 | 11.37 |

| Taşkinsel et al., 2014 | 2.41 | 0.39 | 1.64 | 3.18 | <0.001 * | 16.44 |

| microhybrid composite | 1.44 | 0.46 | 0.54 | 2.33 | 0.002 * | 100.00 |

| Al-Abdullah et al., 2017 | 0.67 | 0.46 | −0.23 | 1.57 | 0.143 | 17.43 |

| Al-Dharrab, 2013 | −3.33 | 0.52 | −4.36 | −2.31 | <0.001 * | 17.31 |

| Ali et al., 2024 | 1.59 | 0.66 | 0.29 | 2.88 | 0.017 * | 17.00 |

| Md Jasin et al., 2023 | 3.16 | 1.22 | 0.76 | 5.56 | 0.010 * | 15.26 |

| Tanthanuch et al., 2022 | 11.33 | 1.20 | 8.99 | 13.68 | <0.001 * | 15.36 |

| Taşkinsel et al., 2014 | 0.68 | 0.31 | 0.07 | 1.30 | 0.030 * | 17.65 |

| nanohybrid composite | 2.15 | 1.26 | −0.31 | 4.62 | 0.087 | 100.00 |

| Ahmadizenouz et al., 2016 | 1.24 | 0.42 | 0.42 | 2.06 | 0.003 * | 21.05 |

| Al-Dharrab, 2013 | −1.90 | 0.60 | −3.07 | −0.73 | 0.002 * | 20.69 |

| Ali et al., 2024 | 0.63 | 0.59 | −0.53 | 1.79 | 0.289 | 20.70 |

| Md Jasin et al., 2023 | 3.95 | 1.40 | 1.20 | 6.70 | 0.005 * | 17.94 |

| Tanthanuch et al., 2022 | 8.94 | 0.96 | 7.05 | 10.82 | <0.001 * | 19.62 |

| nanocomposite | 2.46 | 1.47 | −0.43 | 5.35 | 0.095 | 100.00 |

| Summary (random effects) | 1.60 | 0.41 | 0.80 | 2.41 | <0.001 * | |

| Intergroup comparison | 0.658 | |||||

| Egger’s test | 0.160 |

| Study | SMD | SE | −95CI | +95CI | p-Value | Weight [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al-Samadani, 2017 | 1.87 | 0.34 | 1.19 | 2.54 | <0.001 * | 100.00 |

| glass ionomer | 1.87 | 0.34 | 1.19 | 2.54 | <0.001 * | 100.00 |

| Ahmadizenouz et al., 2016 | 5.90 | 0.85 | 4.23 | 7.58 | <0.001 * | 23.89 |

| Checchi et al., 2024 | 2.28 | 0.23 | 1.82 | 2.74 | <0.001 * | 26.86 |

| Erdemir et al., 2012 | 5.10 | 0.57 | 3.97 | 6.22 | <0.001 * | 25.58 |

| Md Jasin et al., 2023 | −1.20 | 0.89 | −2.94 | 0.54 | 0.176 | 23.67 |

| microhybrid composite | 3.04 | 1.21 | 0.67 | 5.41 | 0.012 * | 100.00 |

| Al-Dharrab, 2013 | −1.12 | 0.39 | −1.87 | −0.36 | 0.004 * | 53.48 |

| Md Jasin et al., 2023 | 4.81 | 1.61 | 1.65 | 7.96 | 0.003 * | 46.52 |

| nanohybrid composite | 1.64 | 2.96 | −4.15 | 7.43 | 0.579 | 100.00 |

| Ahmadizenouz et al., 2016 | 2.01 | 0.47 | 1.10 | 2.92 | <0.001 * | 27.82 |

| Al-Dharrab, 2013 | 1.20 | 0.55 | 0.12 | 2.28 | 0.029 * | 27.14 |

| Erdemir et al., 2012 | 5.10 | 0.57 | 3.98 | 6.22 | <0.001 * | 26.95 |

| Md Jasin et al., 2023 | 4.10 | 1.44 | 1.28 | 6.92 | 0.004 * | 18.09 |

| nanocomposite | 3.00 | 0.98 | 1.08 | 4.92 | 0.002 * | 100.00 |

| Summary (random effects) | 2.06 | 0.31 | 1.45 | 2.67 | <0.001 * | |

| Intergroup comparison | 0.590 | |||||

| Egger’s test | 0.450 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Podgórski, F.; Musyt, W.; Bociong, K.; Nijakowski, K. The Impact of Sports Drink Exposure on the Colour Stability of Restorative Materials: A Systematic Review. J. Compos. Sci. 2026, 10, 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs10020074

Podgórski F, Musyt W, Bociong K, Nijakowski K. The Impact of Sports Drink Exposure on the Colour Stability of Restorative Materials: A Systematic Review. Journal of Composites Science. 2026; 10(2):74. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs10020074

Chicago/Turabian StylePodgórski, Filip, Wiktoria Musyt, Kinga Bociong, and Kacper Nijakowski. 2026. "The Impact of Sports Drink Exposure on the Colour Stability of Restorative Materials: A Systematic Review" Journal of Composites Science 10, no. 2: 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs10020074

APA StylePodgórski, F., Musyt, W., Bociong, K., & Nijakowski, K. (2026). The Impact of Sports Drink Exposure on the Colour Stability of Restorative Materials: A Systematic Review. Journal of Composites Science, 10(2), 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs10020074