1. Introduction

Currently, there is great interest in the use of hydrogen as a fuel due to its high specific calorific value [

1]. Various development lines exist for this technology, but one of the most relevant is the use of tanks with a high structural fraction [

2]. Multiple advances are being made in the development of composite material tanks that improve the tank’s weight efficiency [

3]. The most commonly used tanks today are Type III, which have a metallic liner that prevents leaks, while most mechanical loads are borne by the outer layer made of composite material. This configuration presents problems due to the difference in thermal expansion between the liner and the composite material.

An optimal solution for this type of problem is the use of polymer liners that reduce the aforementioned thermal expansion differences or the complete elimination of any liner. The use of polymer liners shows promising results. It has been implemented by manufacturers such as Toyota, Honda, and Hyundai [

4]. Still, it has issues due to its higher permeability to hydrogen and the increased manufacturing complexity, being much less efficient than solutions without any liner. The use of fully composite tanks (Type V) appears to be an optimal solution for the aerospace sector due to its structural efficiency [

5] and simplicity.

The problem with tanks without metallic liners (Types IV and V) lies in their difficulty in ensuring leak tightness [

6], in addition to the limited number of developments in this area. This concern about leaks is reflected in the European Regulation REGULATION (EC) No 79/2009 [

7], which, in Annex IV, requires leak tests only for Type IV tanks (and, by extension, Type V). One of the challenges with composite material tanks is the influence of damage on their permeability or leakage behavior. Typically, composite materials are designed to be damage-tolerant, defining damage as a characteristic that causes the material to deviate from ideal behavior. On the other hand, fault [

8] is defined as the cause by which a material ceases to operate satisfactorily—in our case, when it leaks or exhibits hydrogen permeation. Consequently, it can be deduced that microcracks considered damage in typical aircraft structures can be considered faults in tanks, as they induce permeation.

The implementation of a structural health monitoring (SHM) system in hydrogen tanks can be especially interesting, as it allows adapting the use and inspection of the tank based on the level of recorded damage, enabling longer nondestructive inspection intervals, and even extending the life of small tanks designed for specific cycles. In the case of hydrogen tanks, relatively few SHM studies have been carried out. Among these, Graue [

9] stands out, providing a comparative study of all structural monitoring systems, including Non-Destructive Inspection (NDI). Additionally, studies have been conducted comparing different adhesives at low temperatures without reaching typical operating temperatures [

10]. Reference [

11] analyzed the possibility of using piezoelectric sensors at specimen corners to detect damage in small test specimens but without results in an actual tank.

The option of monitoring strain in hydrogen tanks using Fiber Bragg Gratings (FBGS) has also been analyzed in reference [

12], obtaining satisfactory real-time flight results. In reference [

13], a Bragg optical fiber was embedded in a small tank between the liner and the first layer, fixing the fiber to the liner before winding. This case uses a residual stress strategy for damage detection and localization but does not directly address the main problem with hydrogen tanks, which are leaks and permeability, focusing instead on Barely Visible Impact Damage (BVID) detection. Reference [

14] used optical fibers to monitor stresses during winding, curing, and exposure to different tests. These studies also include the use of distributed optical fibers to detect pressurization and impacts [

15].

The present work does not primarily address the challenges associated with embedding an optical fiber inside a hydrogen tank but instead focuses on identifying which measurable parameters are most suitable for detecting microcracking within composite laminates. A micromechanical analysis of the Coefficient of Thermal Expansion is performed and subsequently related to the extent of microcracking and, in turn, to permeability or leakage behavior. In

Section 2, the proposed monitoring approach is introduced and all experimental methodologies and modeling strategies employed in this study are described.

Section 3 presents the results, comparing thermal expansion with the measured permeability and microcrack density. Finally,

Section 4 provides an interpretation of the findings and discusses their implications.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. System Description

In the proposed system, an optical fiber will be used as the sensor to measure strain, preferably a Rayleigh distributed fiber [

16], due to the larger number of points it covers, although other methods, such as FBGS or techniques like Sensuron [

17], can also be used. As shown in reference [

18], the sensors do not detect damage per se; rather, a certain feature extraction process is required. For this purpose, an algorithm such as the one in

Figure 1 is implemented, where the main detection parameter is the Coefficient of Thermal Expansion.

To achieve this, during the heating of the tank, temperature and strain are monitored at different points of the tank, and the measured effective thermal expansion is compared with the theoretical one. From this difference, a diagnosis is made of the theoretical microcrack density, which is subsequently associated with the laminate’s permeability. One might think that the intermediate step of determining the level of microcracking is unnecessary, but a review of the literature shows that there are many studies linking microcrack density to mechanical properties [

19,

20] and many studies linking cracks to permeability, whereas very few studies directly relate the effective properties of the laminate to its permeability. The microcracking level is the common link between these two otherwise distinct fields.

Since the chosen sensor is an optical fiber measuring strain, the best way to assess damage is considered to be through the effective mechanical properties of the material. From the analysis of different works, both analytical [

19,

21,

22,

23] and experimental [

24], it can be concluded that in carbon laminates, the stiffness reduction due to microcracking is very small, resulting in low system sensitivity and complicating its application in real cases. On the other hand, it has been shown that the thermal expansion in carbon varies significantly when cracks are present, and this effect is amplified when the laminate is subjected to loads [

25].

As noted earlier, the system focuses on using the liquid hydrogen inside the tank and, knowing that the tank’s operating temperatures are in the range of 20 K to 70 K, calculating the thermal expansion from the measurement of temperature and strain using an optical fiber (one isolated from the strain via a capillary and another bonded to the surface) and comparing it to a healthy state (Second Axiom of [

26]).

The current work focuses on the measurement of a single point on the tank. The crack identification process would require different measurement points along the tank to obtain a statistically representative sample of the tank’s condition. Furthermore, it should be noted that the system does not monitor a leak itself but rather a state of damage that could lead to one. Therefore, the system measures the general health status of the tank before leakage, making the statistical approach valid. Additionally, a distributed fiber approach, such as Rayleigh scattering-based sensing, would be advisable to maximize the number of measurement points.

2.2. Testing Materials

Non-standard test specimens were used for the experiment, differing from ASTM D3039 due to their greater width (30 mm). This width was selected to optimize permeability testing. Cross-ply M21/IMA prepreg specimens with a stacking sequence of

(1.5 mm of thickness as reported in

Figure 2) were used, resembling the configuration that would be found in the cylindrical section of a hypothetical tank. Additionally, glass fabric end tabs were applied as specified in ASTM D3039 (Standard Test Method for Tensile Properties of Polymer Matrix Composite Materials) [

27].

For mechanical cycling and thermal calibration, an Oxford cryostat Model 100 KN S/N 40786 was used, capable of testing at temperatures below 20 K. An INSTRON 5900R load cell was employed for cycling with displacement control, using an Epsilon LG10 extensometer as reference. Cooling was achieved using a Quantum X helium recovery system, and fine thermal adjustment at 20 K was managed with a Lakeshore 336 temperature controller. Temperatures were measured with Lakeshore 218 equipment and using, as reference temperature sensors, DT-670 silicon diodes [

28].

All specimens were instrumented with Fiber Bragg Gratings (FBGS) optical fiber featuring two Bragg gratings located at 1530 nm and 1560 nm and oriented at 90° and 0°, respectively. The specimens were pre-sanded and then bonded using a Tokyo Measuring Instruments Laboratory adhesive, EA-2A, specifically designed for cryogenic temperatures. Four-millimeter gratings were used from the brand FBGS with an Ormocer coating. A shorter grating was selected to minimize the bonded surface and minimize strain gradients in the adhesive caused by high thermal variabilities. The observed Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) of 35 dB confirms the high reflectance of the grating. This strong return signal is notable given the grating’s relatively short physical length. Adhesive curing for all gratings was performed at room temperature, except for the 90°-oriented grating on specimen 5, which was cured at 50 °C. Two different optical interrogators were used for the thermal expansion determination tests. A four-channel Si155 of LUNA and a four-channel HBM SI405 optical interrogator for the Coupon 5.

2.3. Microcracking Mathematical Model

The first step is to determine the relationship between the level of microcracking and the effective thermal expansion of the laminate. Several models exist that relate the spacing between microcracks to the effective properties of the material. Hashin [

25] developed a model that links the effective thermal expansion of a

laminate to its effective expansion when subjected to loading. Using Levin ’s [

29] definition of the effective thermal expansion coefficient, it is indicated that thermal expansion depends not only on the level of cracking but also on the applied loads.

Multiple models derive the effective material conditions from microcracking, with McCartney’s models [

23,

30,

31] being the most applicable to the cross-ply laminates used. On one hand, some models predict thermoelastic constants using a damage parameter

, which can be related to crack density [

30]. While permeability could be used as a damage parameter, it has been considered that the relationship between thermoelastic properties and permeability is less direct than the relationship between crack density and permeability. The drawback is that the elastic constants are expressed as functions of the damage parameter

rather than crack density, which is the observable quantity.

Therefore, it is necessary to study how the effective elastic constants of the material relate to a visible or inspectable quantity, such as the density of microcracks. Another study by McCartney [

31] defines a relationship between microcrack spacing and the various elastic constants of the material for a

laminate. In this way, a function for the thermal expansion coefficient is obtained, dependent on elastic and geometric variables of microcracking.

In the expression for the effective thermal expansion coefficient, the following parameters are defined:

: Longitudinal thermal expansion coefficient of the undamaged ply.

, : Coefficients related to the mechanical properties of the laminate and the crack density.

: Longitudinal Poisson’s ratio of the ply.

: Poisson’s ratio in the longitudinal direction of the central ply.

: Transverse elastic modulus of the ply under the plane strain assumption.

H: A variable dependent on the elastic and geometric properties of the plies.

, : Thermal expansion coefficients in the transverse direction of the ply and the corrected central ply under the plane strain assumption, respectively.

The model has been implemented in Python 3.13.5 and successfully validated against reference [

30], using the same constants as in [

30], and then applying the model with IMA/M21 constants. It can be argued that the model is only applicable for 0-90-0 laminates, but similar crack densities have been observed in all 90° plies throughout the laminate after microscopic inspection. In reference [

30], a one-dimensional shape function in the longitudinal direction of the laminate,

, is obtained by imposing the free stress boundary condition at the crack surface. The strain of the cracked laminate is calculated using the equation, obtaining the elastic moduli and thermal expansions from this strain:

If we have all 90° cracks with similar densities, this function will be similar in all layers, and consequently, the strain field of the cracked laminate will be similar in all plies, and McCartney’s model will be valid. This occurs because this laminate is a third-generation laminate with an interply interface that minimizes the effect of the double thickness in the intermediate layer. In the case of other laminates, an intermediate value will be obtained between the crack density in the central sub-laminate and the rest of the plies, which will have a greater distance between cracks.

2.4. Tests Performed

Two types of tests were conducted in the cryostat: one to measure the thermal expansion of the specimen, and another involving mechanical cycling at different temperatures (

Table 1). In some cases, where a very small reduction in the thermal expansion coefficient was observed, the test was repeated to assess the accuracy in estimating crack density.

The test procedure consisted of the following steps:

- 1.

Determination of the healthy thermal expansion in the cryostat from 20 K to room temperature (RT).

- 2.

Measurement of permeability in an undamaged specimen.

- 3.

Mechanical cycling (70 cycles with varying strain levels).

- 4.

Measurement of permeability in a cycled specimen.

- 5.

Non-destructive inspection of the specimens.

- 6.

Determination of thermal expansion in the cryostat from 20 K to RT for cycled specimens.

- 7.

Destructive testing of the specimen and inspection using Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM).

Table 1.

Summary of mechanical cycling tests performed in the cryostat. The different tests have been designated with an Mi code to identify the specimen condition at the time of thermal expansion measurement, as shown in

Table 2.

Table 1.

Summary of mechanical cycling tests performed in the cryostat. The different tests have been designated with an Mi code to identify the specimen condition at the time of thermal expansion measurement, as shown in

Table 2.

| Specimen Number | Testing Temperature (K) | Mechanical Test Number | Strain Amplitude |

|---|

| 1 | 20 | M1 | 3000 |

| M5 | 3000 |

| 2 | 20 | M2 | 5000 |

| 3 | 77 | M3 | 4000 |

| M6 | 5200 |

| 4 | 20 | M4 | 6500 |

Table 2.

Thermal expansion measurements of the specimens in different post-cycling mechanical states. Mechanical cycling conditions are defined in

Table 1. Coupon 5 was only tested in thermal cycling conditions.

Table 2.

Thermal expansion measurements of the specimens in different post-cycling mechanical states. Mechanical cycling conditions are defined in

Table 1. Coupon 5 was only tested in thermal cycling conditions.

| Test Number | Coupon Tested | Mechanical State |

|---|

| T1 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 | Before M1, M2, M3 and M4 |

| T2 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 | After M1, M2, M3 and M4 and before M5 and M6 |

| T3 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 | After M1, M2, M3, M4 and before M5 and before M6 |

| T4 | 3 | After M6 |

The strain was used as the defining variable for mechanical loading, as it is the determining factor for the appearance of cracks in the central 90° ply [

32], which is also the thickest layer (see

Figure 2).

2.5. Thermomechanical Properties of the Healthy Laminate

During cycling tests, the longitudinal stiffness of the laminate was observed and compared to evaluate repetitiveness of the samples. The mechanical properties of the laminates tested at 20 K are quite similar, with stiffness values ranging from 80.5 to 85.5 GPa. On the other hand, the specimen tested at 77 K showed lower stiffness (78 GPa), which is consistent with the literature [

33].

Experimental results for thermal expansion showed high variability, a consequence of measuring extremely low magnitudes, where the data are highly susceptible to instrumental noise and minor inaccuracies in FBG orientation. Therefore, in order to validate the raw data, the Classical Laminate Theory (CLT) [

34] was used to model the macroscopic response of the laminate.

In this case, the result was 3.3 μm/m °C

−1, which corresponds to a value of the same order of magnitude as the experimental data. These errors may be attributed to FBG misalignment and/or incorrect panel cut orientation. It was also observed in the literature [

35] that this type of laminate exhibits considerable variability in Coefficient of Thermal Expansion (CTE) data, even depending on the stacking sequence. This inherent sensitivity to material parameters (like stacking or orientation) may directly explain the high uncertainty observed in our initial thermal expansion measurements, given the minute magnitudes of

involved.

Additionally, using Classical Laminate Theory (CLT), it was confirmed that variations in transverse and shear elastic moduli can significantly affect the value of the effective thermal expansion coefficient.

It was therefore considered necessary to compare the data from the specimens across different repetitions due to the high variability observed. A very similar response was seen across repetitions, as shown in

Figure 3, where a second and third thermal expansion measurement of the healthy specimen (Specimen 5) was performed.

Thermal Expansion Determination

A linear regression of the thermal expansion was performed across different temperature intervals for the five tested specimens. This approach enables the observation of a progression in the expansion coefficients and characterization of the specimen over a wide temperature range, using micromechanical models for microcrack characterization that incorporate the thermal expansion coefficient as a variable.

The thermal expansion coefficient data for all specimens are presented in

Table 3. The Coefficient of Thermal Expansion (CTE) is considered the average change in thermal strain over a specific temperature range, representing the secant of the thermal expansion curve, provided the thermal strain response exhibits locally linear behavior within that range. Data for the 90° direction in Specimen 4 are not included. Starting from the compensated strain equation [

36], the following is true:

It is assumed that is the gauge factor and is a temperature correction constant, the strain and the Bragg Wavelength. In our case, the temperature has been measured and a curve has been obtained that describes how varies with temperature in a strain-free sensor, thus providing thermal compensation.

To calculate the effective Coefficient of Thermal Expansion (CTE) in each direction, we use the following expression:

Additionally, to compare responses, it is often useful to determine the strain due to thermal expansion directly. For this purpose, the compensation method implemented in reference [

37] is used.

2.6. Permeability Tests

For the evaluation of permeability or leakage, a tracer gas method was used due to the size and morphology of the sample. In this type of permeability testing, a mass spectrometer is employed, as shown in

Figure 4. The setup is based on reference [

38], but simplified since the tests were conducted at room temperature and did not involve a cryostat in the measurement process. The tests were performed at constant temperature, as the results are highly dependent on this variable. The equipment used included a QMG 250 PrismaPro mass spectrometer from Pfeiffer, a HiPace 80 turbomolecular pump, a PKR361 pressure sensor, and an Omnicontrol data acquisition system, also from Pfeiffer Vacuum.

The specimen was connected to helium, and the helium signal was measured by the mass spectrometer while a vacuum was applied using the pump. A pressure gauge was necessary because a high vacuum is required to avoid damaging the tungsten filament of the mass spectrometer.

The mass spectrometer was calibrated using two Pfeiffer calibrated leaks with nominal leak rates of mbar·l/s and mbar·l/s. Both leaks were connected to the ISO KF 40 port, where the specimens are normally mounted.

The standard calibration procedure was followed. First, a vacuum of approximately mbar was established with the calibrated leak valve closed, to define the zero reference. Next, the leak valve was opened, and the signal was allowed to stabilize for several hours. Once stable, the mass spectrometer current (in amperes) was recorded after exposing the specimen location to one bar of helium gas. The procedure was then repeated using the second calibrated leak.

From the three resulting measurements—zero, calibrated leak 1, and calibrated leak 2—a calibration curve was constructed to convert the measured current (A) into leak rate (mbar·l/s), from which the sensitivity was determined.

Once the spectrometer has been calibrated with calibrated leaks, the experiment is performed at different helium pressures so that the permeability can be obtained through Fick’s law in a steady state. The leak rate and therefore permeability were measured for all the cycled specimens before and after the mechanical testing. The Permeability is calculated using the Stationary Fick Law [

39]:

would be the steady state leak rate,

P would be the permeability,

d the specimen thickness

A, the sample surface area, and

the partial pressure difference between both sides of the sample.

3. Results

3.1. Thermal Expansion

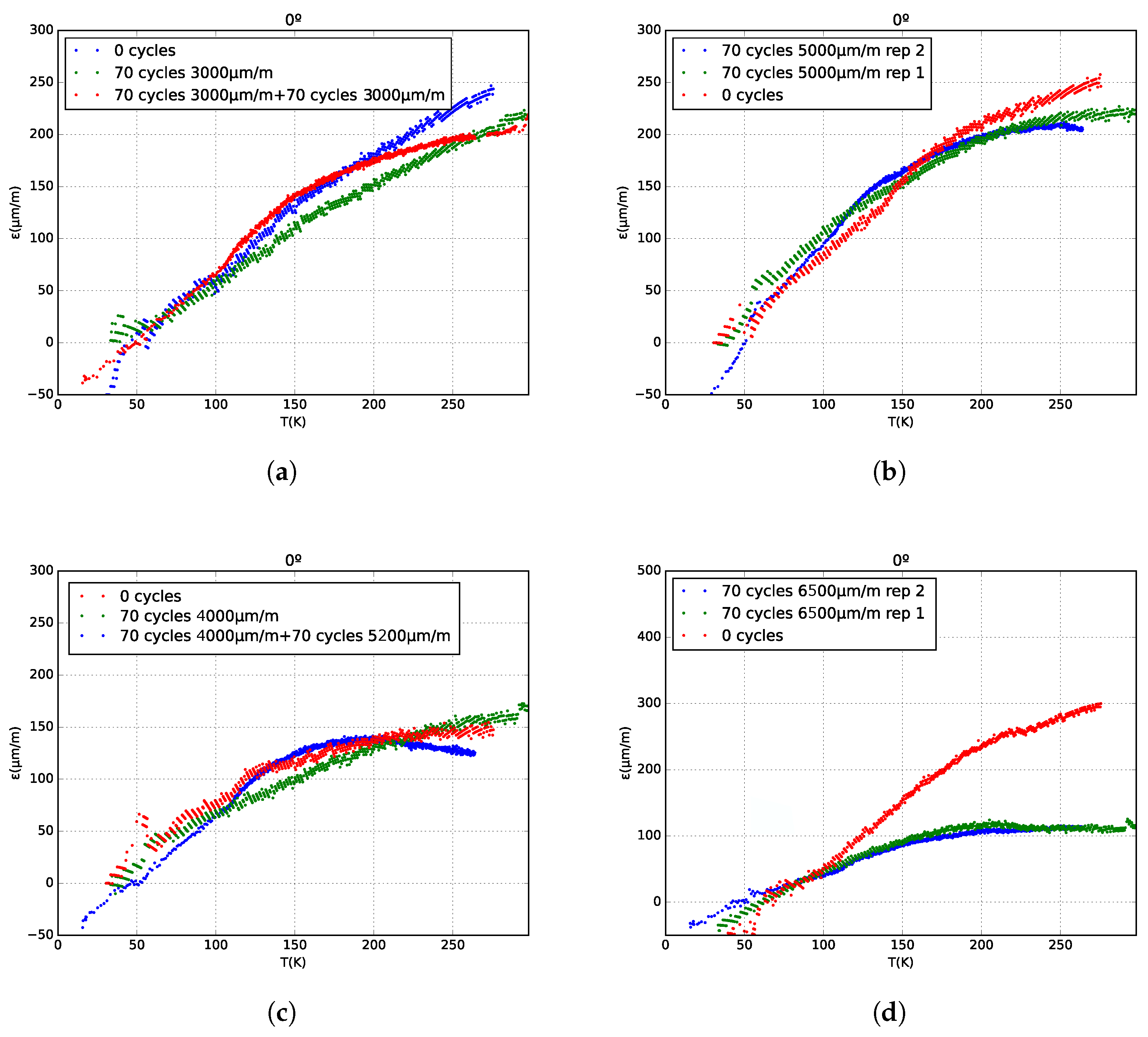

The results have been presented as thermal expansion curves for the different specimens. A clear dependence of the thermal expansion slope on the number of applied cycles and the induced strain can be observed. As previously mentioned, there are significant differences in thermal expansion among the various specimens; however, the strain does not change if the specimen has not been subjected to any mechanical loading.

It can be seen that mechanical strains greater than 5000 µm/m are required to observe noticeable changes in thermal expansion at temperatures above 200 K. Likewise, at temperatures below 150 K, no significant differences in the thermal expansion of the laminate are observed.

As shown in

Figure 5, after the first mechanical cycle, specimens 1 and 3 exhibit nearly identical strain behavior compared to the same specimens without any cycling. However, after the second cycle, a noticeable change begins to appear.

Furthermore, when mechanical cycling induces strains greater than 5000 µm/m, the thermal expansion at temperatures close to room temperature becomes nearly zero, or even negative in the case of specimen 3. This behavior is consistent with experimental data reported in other references, such as Bowles (1982) [

24].

Additionally, it can be observed that specimens 2, 4, and 5—which have two or three repetitions under the same mechanical cycling conditions (5000 m/m in the case of specimen 2, 6500 µm/m for specimen 4, and three repetitions without any mechanical cycling for specimen 5)—show good repeatability. Therefore, a causal relationship can be established between mechanical cycling (and the associated microcracking) and the thermal expansion of the laminate.

Moreover, these same thermal deformations can be expressed using the thermal expansion coefficient. The coefficient is used to express the result as the ratio between the thermal expansion coefficient of the undamaged laminate and that of the damaged one, similar to the approach described in reference [

31].

According to

Table 4, it can be concluded that the trends vary depending on the temperature range. At low temperatures, there is no significant difference, or the expansion is even greater in the cracked specimens. On the other hand, it is observed that the thermal expansion coefficient tends to decrease as higher mechanical loads are applied, and consequently, as more microcracking occurs.

3.2. Permeability Values

Permeability tests were carried out on the cycled specimens to observe possible differences in the permeability of the various samples. First, the intensity value provided by the mass spectrometer was obtained, and knowing that there is a linear relationship with the leak rate [

40], the leak flow value was calculated. Then, using Equation (

8), the permeability value of the specimen after microcracking was determined. It was found that the permeability values are comparable to those of other carbon/epoxy materials [

41] and do not change significantly in the presence of microcracking (

Table 5). This indicates that the system can monitor the condition of the material before any considerable leakage occurs.

3.3. Crack Density Estimation

To estimate the crack density, the McCartney model was used. It was applied to the Coefficient of Thermal Expansion (CTE) measurements at room temperature, since the mechanical properties of the laminate at cryogenic temperatures are not known. Firstly, the thermal expansion coefficient curve (

Figure 6) of the laminate was calculated using Equation (

1), and taking as a reference the thermal expansion coefficient of the uncracked laminate. Then, based on the Coefficient of Thermal Expansion (CTE) experimental values, an equivalent crack density estimation was performed (see

Table 6) for a 0°–90°–0° laminate. This kind of laminate was selected as a reference due to the extensive literature available on this configuration and its recognition as a benchmark in microcracking studies. In the present work, the laminate under investigation is a

, which is expected to exhibit thermomechanical properties and microcracking behavior comparable to those of the reference configuration as pointed out in

Section 2.3. Crack densities were measured using a SEM TM 3000 Microscope and the results were compared with the analytical model using the constants in references [

35,

42] as reported in

Figure 6.

The crack density was quantified by measuring the locations of individual cracks along the X-axis and subsequently calculating the distribution of inter-crack distances. To ensure a robust estimation of the central tendency, the median distance was utilized, as the presence of outliers (extreme values) rendered the arithmetic mean statistically unreliable for modeling the crack spacing.

A fairly close correlation can be observed between the CTE data measured experimentally and the values obtained analytically. Furthermore,

Figure 6 shows that in the analytical calculations there is a linear region in the difference between the CTE of the undamaged and cracked laminates. This region corresponds to the range in which the proposed methodology is most sensitive. Beyond a crack density of approximately 3.5 cracks per millimeter, the curve begins to flatten, indicating that the measured values become nearly independent of the laminate’s crack density.

4. Discussion

There are two main issues that must be discussed. First, why a significant difference in thermal expansion has only been observed at temperatures close to room temperature, and second, why no significant effect on permeability has been detected even in the absence of microcracks.

First, it is suspected that there is no significant difference in thermal expansion at low temperatures, according to Levin [

29] and Hashin’s microcracking paper [

25]. Since no stress exists within the matrix, there is no difference in strain or stress compared to the uncracked laminate. Furthermore, as the laminate continues to expand due to the temperature increase and a non-uniform stress and strain distribution develops between cracks, the laminate begins to exhibit a difference between the behavior of the undamaged and the damaged states.

In the case of permeability, several studies have shown that for a noticeable effect to occur, cracks must develop in both directions. Leakage in CFRP laminates typically arises from the intersection points between cracks formed in the 0° and 90° plies, which create continuous leakage paths toward the exterior surface [

43,

44].

One of the limitations of the present experimental campaign is that the tests were not performed under biaxial loading conditions, which are necessary to generate cracks in all ply orientations [

44]. Additionally, as the material expands, some of the cracks may have partially closed, further restricting the helium flow and thereby reducing the apparent permeability. Another relevant aspect would be to perform the tests at temperatures close to

. At cryogenic temperatures, the cracks would shrink, opening up and affecting potential leaks. Furthermore, permeability is highly dependent on temperature, as can be seen in reference [

45]. Therefore, performing the tests at room temperature might lead to unrepresentative test conditions, even though it may be valid as an initial approximation.

As a result, no representative leakage could be detected in the measurements, even though a clear change in the effective Coefficient of Thermal Expansion was observed.

5. Conclusions

In this work, the thermal expansion behavior of a [0/90]2s laminate has been studied to assess whether this property can be effectively used for the detection of microcracking and leakage in a liquid hydrogen tank. To this end, cracks were induced in the laminate at temperatures close to 20 K, and the thermal expansion of the laminate was subsequently evaluated.

The results are insightful, as they show that the Coefficient of Thermal Expansion varies significantly at temperatures near room temperature. Although the main objective was to detect a potential difference in behavior at temperatures around 70 K—the upper limit of the operating range of the internal tank—no appreciable difference was observed at this temperature or below.

Additional permeability tests were conducted, revealing no clear correlation between microcrack density and permeability. This behavior is attributed to the absence of continuous helium leakage paths between adjacent cracks. Based on these results, it can be concluded that monitoring microcrack formation through thermal expansion measurements could be a viable approach, provided that the internal tank can be heated to sufficiently high temperatures.