Eco-Friendly Synthesis of ZnO-Based Nanocomposites Using Haloxylon and Calligonum Extracts for Enhanced Photocatalytic Degradation of Methylene Blue

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Materials

2.2. Plants Extraction

2.3. Preparation of Green ZnO Based Nanocomposites Using Plants Extract/L-Cysteine

2.4. Nanocomposite Catalysts Characterization

2.5. Photocatalytic Degradation Experiments

3. Results and Discussion

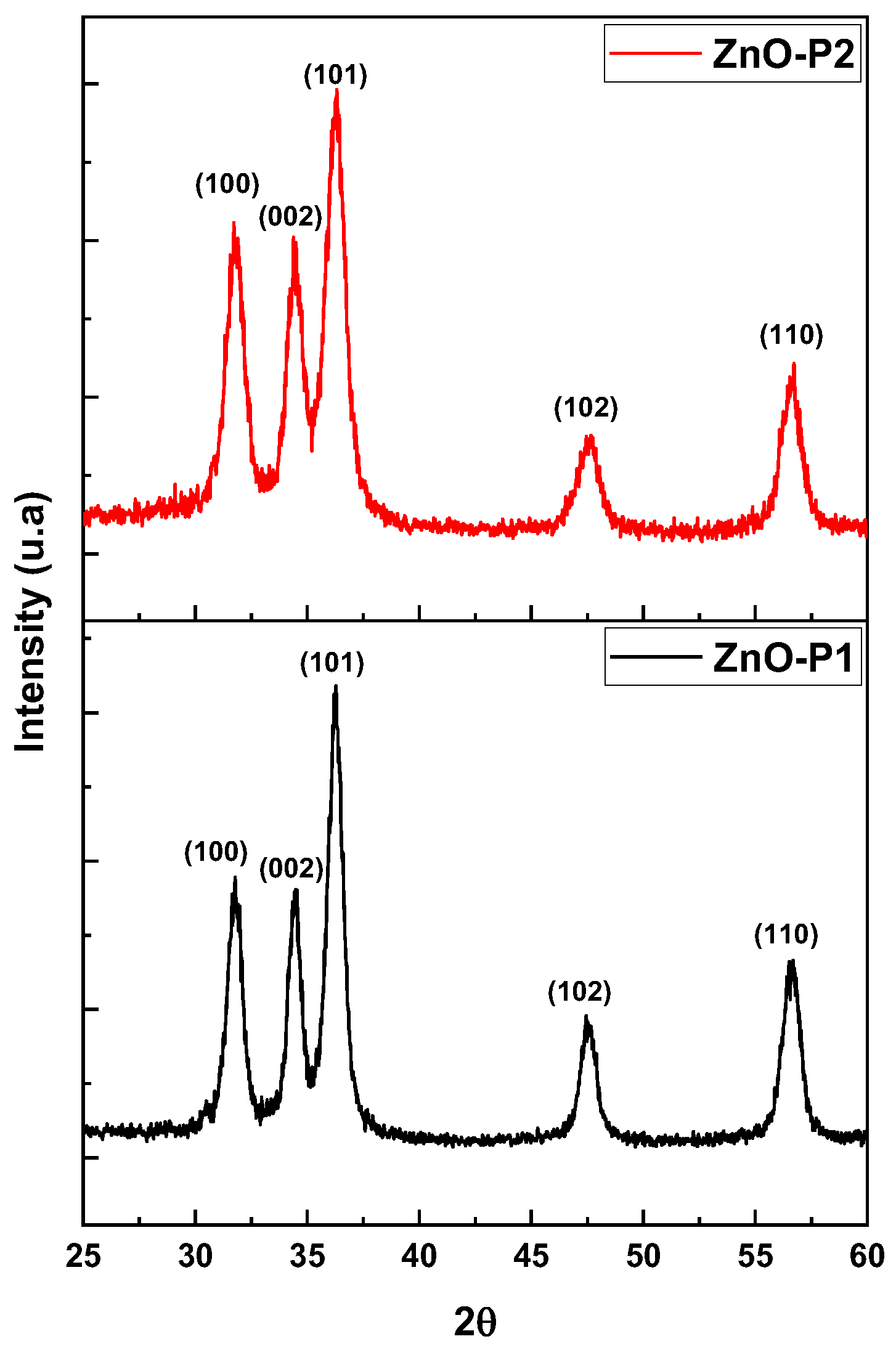

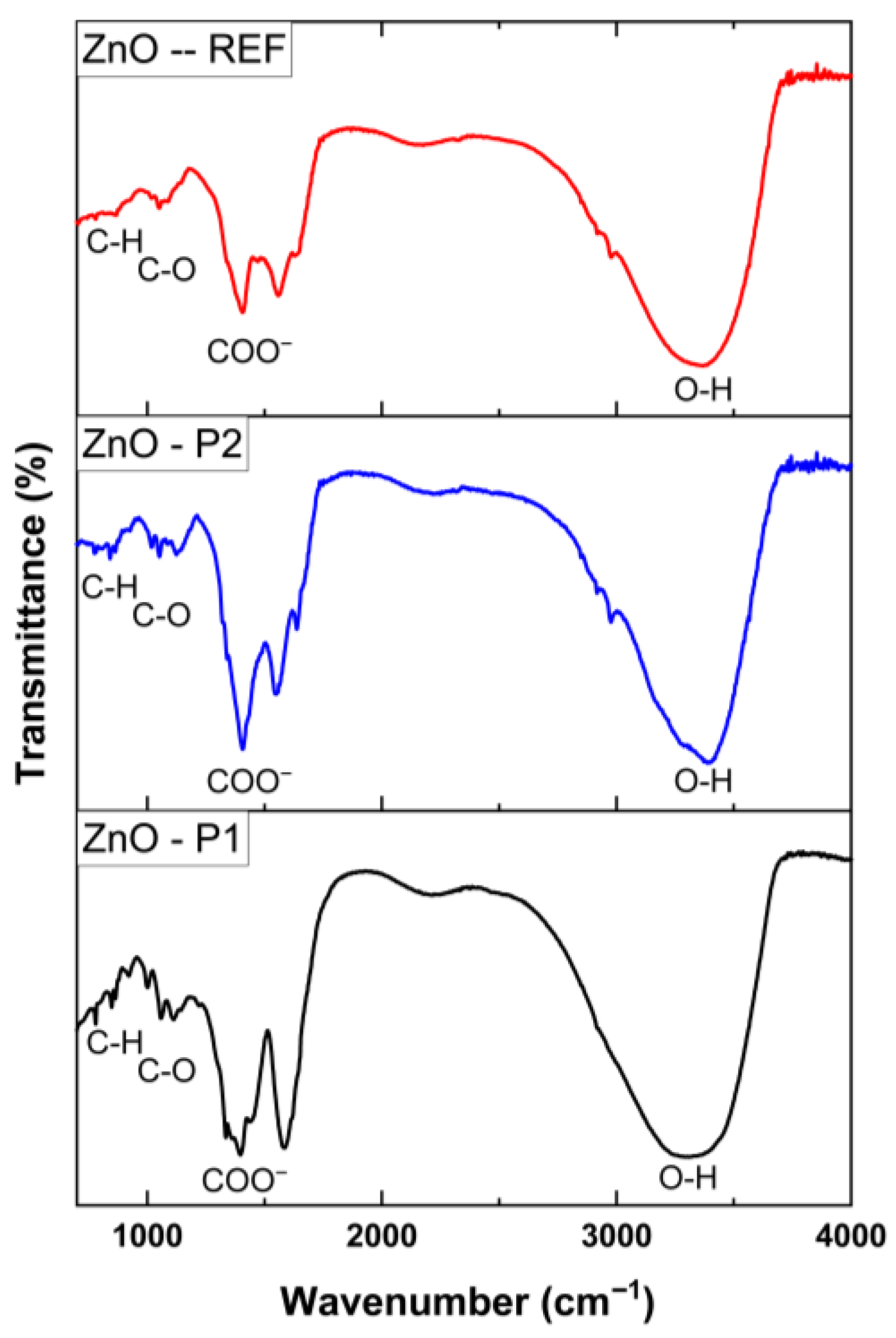

3.1. Nanoparticles Characterization

3.1.1. Morphological Study

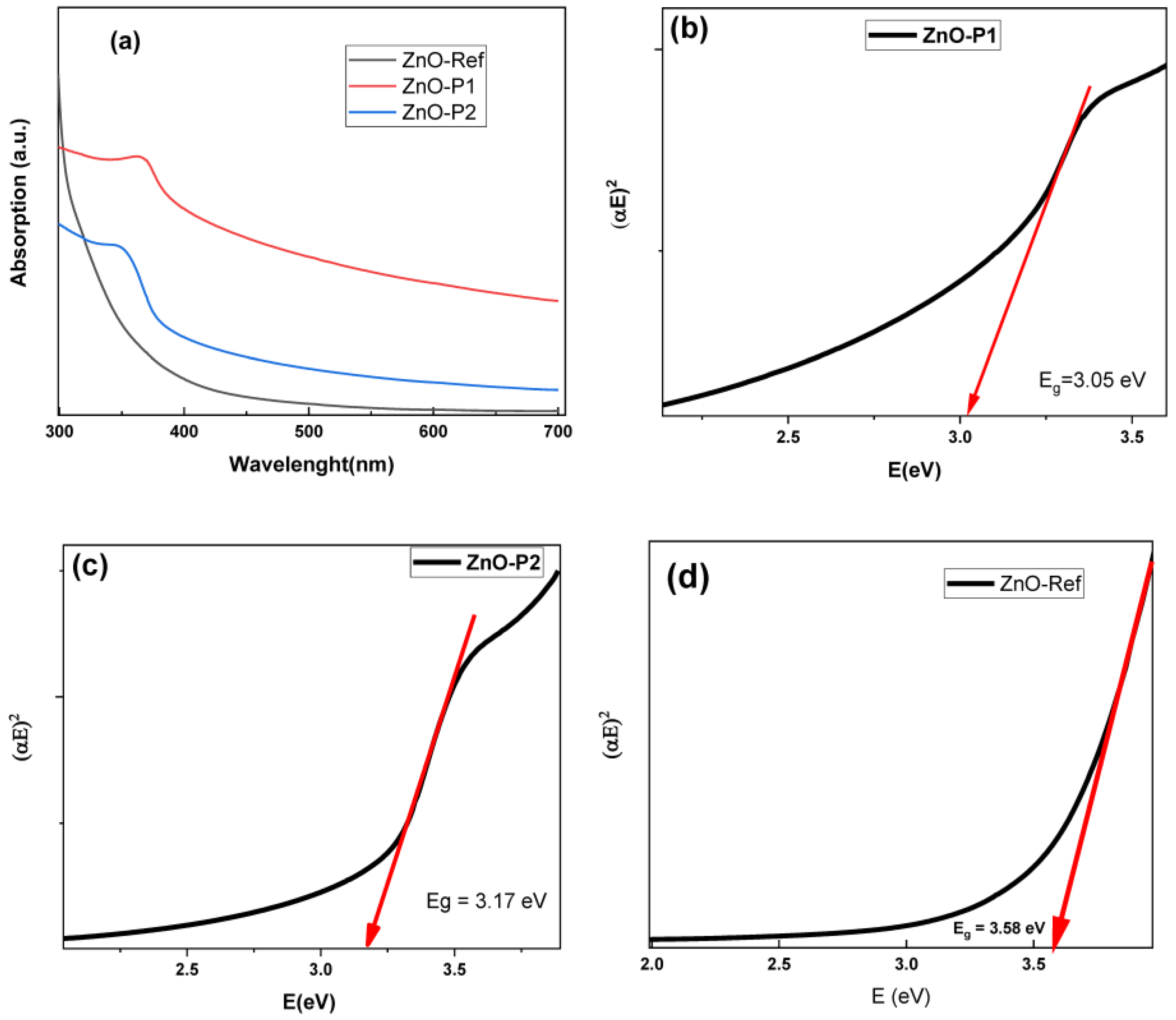

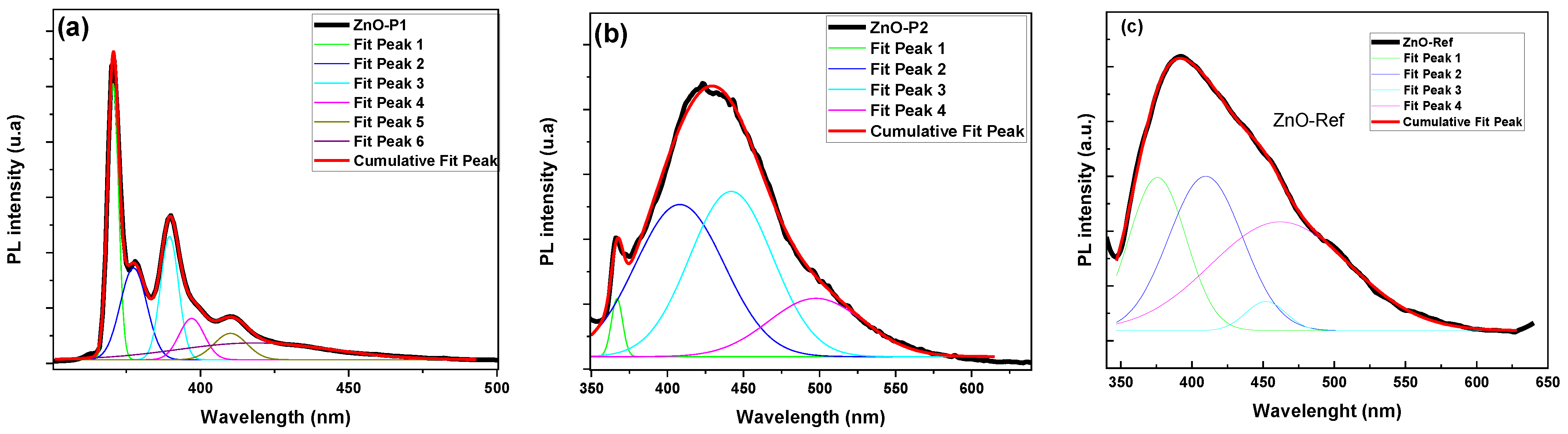

3.1.2. Optical Study

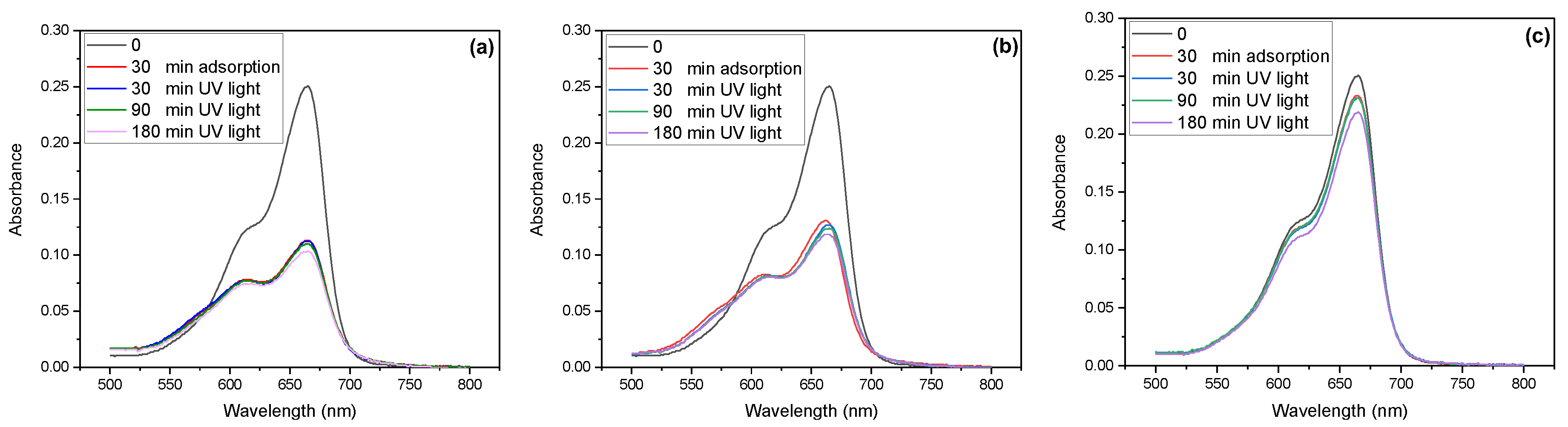

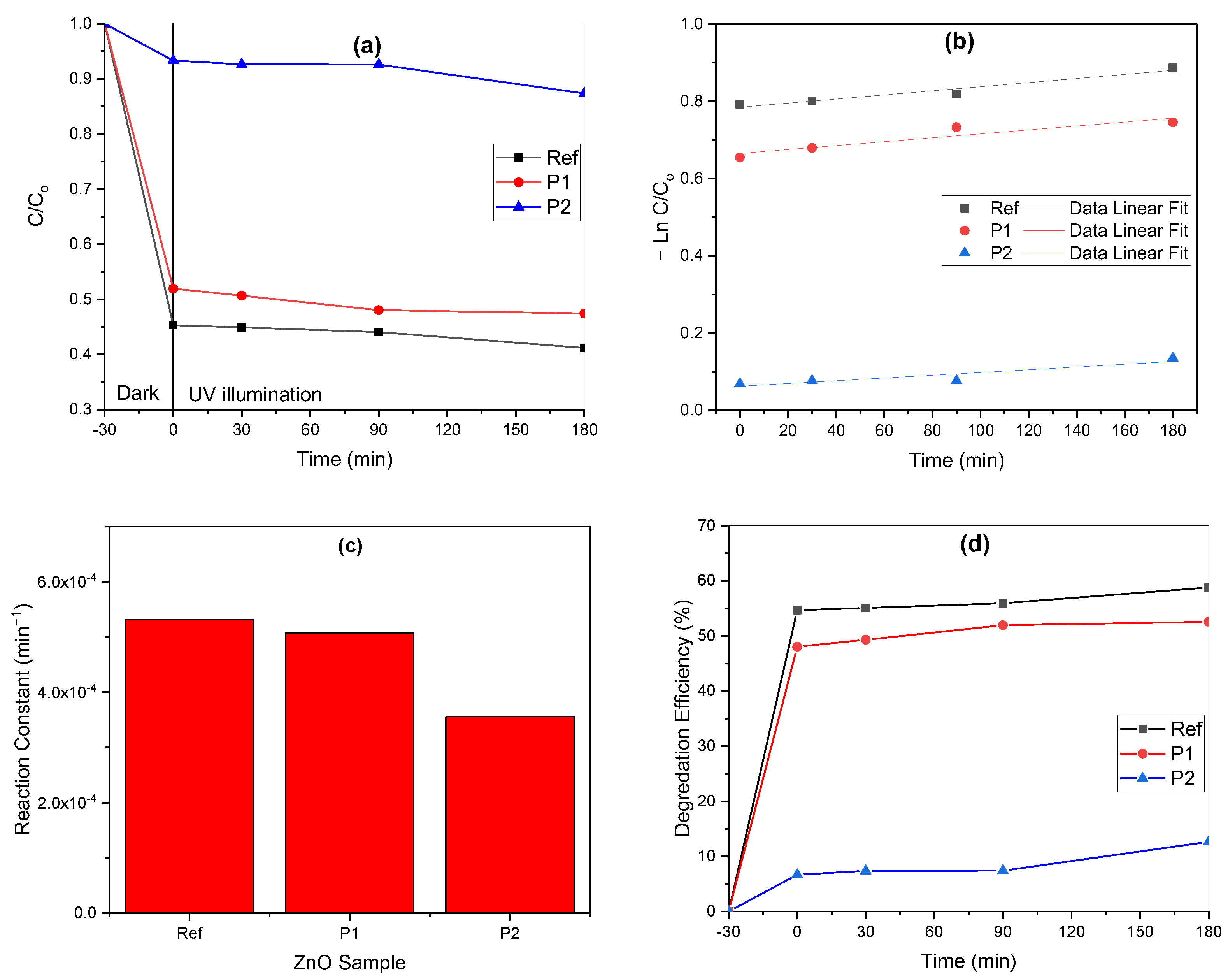

3.2. Photocatalytic Activity of MB Using ZnO Based Nanocomposite Catalysts

- (a)

- Adsorption phase

- (b)

- Photon absorption and electron–hole generation

- (c)

- Reduction of dissolved oxygen to superoxide radicals

- (d)

- Production of superoxide and hydroxyl radicals

- (e)

- Degradation phase

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Luque-Morales, P.A.; Lopez-Peraza, A.; Nava-Olivas, O.J.; Amaya-Parra, G.; Baez-Lopez, Y.A.; Orozco-Carmona, V.M.; Garrafa-Galvez, H.E.; Chinchillas-Chinchillas, M.D.J. ZnO Semiconductor Nanoparticles and Their Application in Photocatalytic Degradation of Various Organic Dyes. Materials 2021, 14, 7537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Huang, Y.; Zhu, S.; Abbes, N.; Jing, X.; Zhang, L. A review of the green synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles using plant extracts and their prospects for application in antibacterial textiles. J. Eng. Fibers Fabr. 2021, 16, 15589250211046242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manoharan, R.; Manjceevan, A.; Velauthamurty, K.; Sashikesh, G.; Vignarooban, K. Conversion of both photon and mechanical energy into chemical energy using higher concentration of Al doped ZnO. J. Alloys Compd. 2023, 948, 169712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hessel, V.; Tran, N.N.; Asrami, M.R.; Tran, Q.D.; Long, N.V.D.; Escribà-Gelonch, M.; Tejada, J.O.; Linke, S.; Sundmacher, K. Sustainability of green solvents—Review and perspective. Green Chem. 2022, 24, 410–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandav, G.; Sharma, T. Green synthesis: An eco friendly approach for metallic nanoparticles synthesis. Part. Sci. Technol. 2024, 42, 874–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouassil, M.; Abdoul-latif, F.; Attahar, W.; Ainane, A.; Mohamed, J.; Tarik, A. Plant-derived metal nanoparticles based nanobiopesticides to control common beans (Phaseolus vulgaris) pests and diseases in Morocco. Ama Agric. Mech. Asia Afr. Lat. Am. 2021, 51, 837–847. [Google Scholar]

- Alqahtani, A.S.; Elbeltagi, S. Advancing chemistry sustainably: From synthesis to benefits and applications of green synthesis. J. Organomet. Chem. 2025, 1027, 123508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, P.; Kaur, A.; Goyal, D. Algae-based metallic nanoparticles: Synthesis, characterization and applications. J. Microbiol. Methods 2019, 163, 105656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangal, A.; Choudhary, K.; Duseja, M.; Shukla, R.K.; Kumar, S. Green synthesis of Silver nanoparticles from plant oil for enzyme-functionalized optical fiber biosensor: Improved sensitivity and selectivity in ascorbic acid detection. Opt. Laser Technol. 2025, 186, 112635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majeed, H.; Iftikhar, T.; Abid, R. Green synthesis of zinc nanoparticles with plant material and their potential application in bulk industrial production of mosquito-repellent antibacterial paint formulations. React. Chem. Eng. 2024, 9, 677–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatraman, S.; Rajendran, D.S.; Vaidyanathan, V.K. Development and Scale-Up of the Bioreactor System in Biorefinery: A Significant Step Toward a Green and Bio-Based Economy. In Biotechnological Advances in Biorefinery; Agrawal, K., Verma, P., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2024; pp. 207–230. [Google Scholar]

- Pirsaheb, M.; Gholami, T.; Seifi, H.; Dawi, E.A.; Said, E.A.; Hamoody, A.-H.M.; Altimari, U.S.; Salavati-Niasari, M. Green synthesis of nanomaterials by using plant extracts as reducing and capping agents. Env. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 24768–24787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vagena, I.-A.; Gatou, M.-A.; Theocharous, G.; Pantelis, P.; Gazouli, M.; Pippa, N.; Gorgoulis, V.G.; Pavlatou, E.A.; Lagopati, N. Functionalized ZnO-Based Nanocomposites for Diverse Biological Applications: Current Trends and Future Perspectives. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, M.; Marwani, H.M.; Shahzad, U.; Asiri, A.M.; Rahman, M.M. Recent Advances, Challenges, and Future Perspectives of ZnO Nanostructure Materials Towards Energy Applications. Chem. Rec. 2024, 24, e202300106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gopi, C.V.V.M.; Alzahmi, S.; Al-Haik, M.Y.; Kumar, Y.A.; Hamed, F.; Haik, Y.; Obaidat, I.M. Recent advances in pseudocapacitive electrode materials for high energy density aqueous supercapacitors: Combining transition metal oxides with carbon nanomaterials. Mater. Today Sustain. 2024, 28, 100981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulab, H.; Fatima, N.; Tariq, U.; Gohar, O.; Irshad, M.; Khan, M.Z.; Saleem, M.; Ghaffar, A.; Hussain, M.; Khaliq Jan, A.; et al. Advancements in zinc oxide nanomaterials: Synthesis, properties, and diverse applications. Nano-Struct. Nano-Objects 2024, 39, 101271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maafa, I.M. Potential of Zinc Oxide Nanostructures in Biosensor Application. Biosensors 2025, 15, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadi, H.; Atmani, E.H.; Fazouan, N. Enhanced photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue dye by ZnO nanoparticles: Synthesis, characterization, and efficiency assessment. Environ. Prog. Sustain. Energy 2025, 44, e14529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, A.; Farhan, A.; Maqbool, F.; Ahmad, H.; Qayyum, W.; Ghazy, E.; Rahdar, A.; Díez-Pascual, A.M.; Fathi-karkan, S. Zinc oxide nanoparticles: Pathways to micropollutant adsorption, dye removal, and antibacterial actions—A study of mechanisms, challenges, and future prospects. J. Mol. Struct. 2024, 1312, 138545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bizuayen Adamu, T.; Melese Mengesha, A.; Assefa Kebede, M.; Lake Bogale, B.; Walle Kassa, T. Facile biosynthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) using Lupinus albus L (Gibto) seed extract for antibacterial and photocatalytic applications. Results Chem. 2024, 10, 101724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, A.; Malan, P.; Ahmad, I.; Khan, A.; Haris, M.; Zahid, Z.; Jameel, M.; Ahmad, A.; Shekhar Seth, C.; Asseri, T.A.Y.; et al. Polyalthia longifolia-mediated green synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles: Characterization, photocatalytic and antifungal activities. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 17535–17546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohideen, A.P.; Loganathan, C.; Khan, M.S.; Abdelzaher, M.H.; Alsanousi, N.; Dayel, S.B. Green Synthesis and Characterization of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles Mediated by Nyctanthes arbor-tristis Leaf Extract: Exploring Antidiabetic, Anticancer, and Antimicrobial Activities. J. Clust. Sci. 2025, 36, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manimegalai, P.; Selvam, K.; Loganathan, S.; Kirubakaran, D.; Shivakumar, M.S.; Govindasamy, M.; Rajaji, U.; Bahajjaj, A.A.A. Green synthesis of zinc oxide (ZnO) nanoparticles using aqueous leaf extract of Hardwickia binata: Their characterizations and biological applications. Biomass Conv. Bioref 2024, 14, 12559–12574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarah, M.; Sihem, A.; Nabila, B.; Asma, Y.; Rafik, C.; Kamilia, M.; Karima, A. Corrosion inhibiting effects of biosynthesized ZnO nanoparticles by the extract of Plectranthus amboinicus leaves. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2024, 168, 112836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Singh, A.; Balomajumder, C.; Vidyarthi, A.K. Assessment of industrial effluent discharges contributing to Ganga water pollution through a multivariate statistical framework: Investigating the context of Indian industries. Env. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhav, S.; Mishra, R.; Kumari, A.; Srivastav, A.L.; Ahamad, A.; Singh, P.; Ahmed, S.; Mishra, P.K.; Sillanpää, M. A review on sources identification of heavy metals in soil and remediation measures by phytoremediation-induced methods. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 21, 1099–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; You, J.; Li, J.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Xu, J.; Duan, M.; Zhang, H. Progress of Copper-based Nanocatalysts in Advanced Oxidation Degraded Organic Pollutants. ChemCatChem 2024, 16, e202301108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adibzadeh, A.; Khodabakhshi, M.R.; Maleki, A. Preparation of novel and recyclable chitosan-alumina nanocomposite as superabsorbent to remove diazinon and tetracycline contaminants from aqueous solution. Heliyon 2024, 10, e23139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahjoub, M.A.; Monier, G.; Robert-Goumet, C.; Réveret, F.; Echabaane, M.; Chaudanson, D.; Petit, M.; Bideux, L.; Gruzza, B. Synthesis and Study of Stable and Size-Controlled ZnO–SiO2 Quantum Dots: Application as a Humidity Sensor. J. Phys. Chem. C 2016, 120, 11652–11662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haiouani, K.; Hegazy, S.; Alsaeedi, H.; Bechelany, M.; Barhoum, A. Green Synthesis of Hexagonal-like ZnO Nanoparticles Modified with Phytochemicals of Clove (Syzygium aromaticum) and Thymus capitatus Extracts: Enhanced Antibacterial, Antifungal, and Antioxidant Activities. Materials 2024, 17, 4340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshammari, A.S.; Mohamed, M.; Bouzidi, M.; Abdulaziz, F. Tailoring the structural and optical properties of sulphur doped g-C3N4 nanostructures and maximizing their photocatalytic performance via controlling carbon content. Opt. Quant. Electron. 2024, 56, 1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouzidi, M.; Yahia, F.; Ouni, S.; Mohamed, N.; Alshammari, A.; Khan, Z.; Mohamed, M.; Alshammari, O.; Abdelwahab, A.; Bonilla-Petriciolet, A.; et al. New insights of the adsorption and photodegradation of reactive black 5 dye using water-soluble semi-conductor nanocrystals: Mechanism interpretation and statistical physics modeling. Opt. Mater. 2024, 159, 116575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chouhan, N.; Yeh, C.; Hu, S.; Huang, J.; Tsai, C.; Liu, R.-S.; Chang, W.; Chen, K. Array of CdSe QD-Sensitized ZnO Nanorods Serves as Photoanode for Water Splitting. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2010, 157, B1430–B1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.; Patel, P.; Sujata, K.; Litoriya, P.K.; Solanki, R.G. Facile synthesis and characterization of ZnSe nanoparticles. Mater. Today Proc. 2023, 80, 1556–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouni, S.; Mohamed, N.B.H.; Haouari, M.; Elaissari, A.; Errachid, A.; Jaffrezic-Renault, N. A Novel Green Synthesis of Zinc Sulfide Nano-Adsorbents Using Artemisia Herba Alba Plant Extract for Adsorption and Photocatalysis of Methylene Blue Dye. Chem. Afr. 2023, 6, 2523–2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, B.H.N.; Bouzidi, M.; Ben brahim, N.; Sellaoui, L.; Haouari, M.; Ezzaouia, H.; Bonilla-Petriciolet, A. Impact of the stacking fault and surface defects states of colloidal CdSe nanocrystals on the removal of reactive black 5. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2021, 265, 115029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolabella, S.; Borzì, A.; Dommann, A.; Neels, A. Lattice Strain and Defects Analysis in Nanostructured Semiconductor Materials and Devices by High-Resolution X-Ray Diffraction: Theoretical and Practical Aspects. Small Methods 2022, 6, 2100932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, W.; Nagase, T.; Umakoshi, Y.; Szpunar, J. Lattice distortion and its effects on physical properties of nanostructured materials. J. Phys.-Condens. Matter 2007, 19, 236217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukhtiar, A.; Zou, B. Low-dimensional II–VI semiconductor nanostructures of ternary alloys and transition metal ion doping: Synthesis, optical properties and applications. Mater. Adv. 2024, 5, 6739–6795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; Ware, P.; Shimpi, N. Synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles using peels of Passiflora foetida and study of its activity as an efficient catalyst for the degradation of hazardous organic dye. SN Appl. Sci. 2021, 3, 528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravhudzulo, I.; Mthana, M.S.; Ogwuegbu, M.C.; Ramachela, K.; Mthiyane, D.M.N.; Onwudiwe, D.C. Phytogenic synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles using extract of Vachellia erioloba seed and their anticancer and antioxidant activity. Discov. Appl. Sci. 2025, 7, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayed, A.M.; Salama, F.M.; Galal, H.K.; Said, M.I. Sustainable production of ZnO nanoparticles via capparis decidua stem extract for efficient photocatalytic Rh 6G dye degradation. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 46890–46907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangwar, C.; Yaseen, B.; Kumar, I.; Singh, N.K.; Naik, R.M. Growth Kinetic Study of Tannic Acid Mediated Monodispersed Silver Nanoparticles Synthesized by Chemical Reduction Method and Its Characterization. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 22344–22356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bushell, M.; Beauchemin, S.; Kunc, F.; Gardner, D.; Ovens, J.; Toll, F.; Kennedy, D.; Nguyen, K.; Vladisavljevic, D.; Rasmussen, P.E.; et al. Characterization of Commercial Metal Oxide Nanomaterials: Crystalline Phase, Particle Size and Specific Surface Area. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouda, A.; Saied, E.; Eid, A.M.; Kouadri, F.; Alemam, A.M.; Hamza, M.F.; Alharbi, M.; Elkelish, A.; Hassan, S.E.-D. Green Synthesis of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles Using an Aqueous Extract of Punica granatum for Antimicrobial and Catalytic Activity. J. Funct. Biomater. 2023, 14, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, A.; Jangid, N.K.; Khan, A.U. Biogenic synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles from Evolvulus alsinoides plant extract. J. Umm Al-Qura Univ. Appll. Sci. 2024, 10, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldeen, T.S.; Ahmed Mohamed, H.E.; Maaza, M. ZnO nanoparticles prepared via a green synthesis approach: Physical properties, photocatalytic and antibacterial activity. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2022, 160, 110313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirnajafizadeh, F.; Ramsey, D.; McAlpine, S.; Wang, F.; Reece, P.; Stride, J.A. Hydrothermal synthesis of highly luminescent blue-emitting ZnSe(S) quantum dots exhibiting low toxicity. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2016, 64, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piña-Pérez, Y.; Aguilar-Martínez, O.; Acevedo-Peña, P.; Santolalla-Vargas, C.E.; Oros-Ruíz, S.; Galindo-Hernández, F.; Gómez, R.; Tzompantzi, F. Novel ZnS-ZnO composite synthesized by the solvothermal method through the partial sulfidation of ZnO for H2 production without sacrificial agent. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2018, 230, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahayu, E.; Wonoputri, V.; Samadhi, T. Plant extract-assisted biosynthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles and their antibacterial application. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 823, 012036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faisal, S.; Jan, H.; Shah, S.A.; Shah, S.; Khan, A.; Akbar, M.T.; Rizwan, M.; Jan, F.; Wajidullah; Akhtar, N.; et al. Green Synthesis of Zinc Oxide (ZnO) Nanoparticles Using Aqueous Fruit Extracts of Myristica fragrans: Their Characterizations and Biological and Environmental Applications. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 9709–9722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Harbi, H.F.; Awad, M.A.; Ortashi, K.M.O.; AL-Humaid, L.A.; Ibrahim, A.A.; Al-Huqail, A.A. Green Synthesis of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles: Physicochemical Characterization, Photocatalytic Performance, and Evaluation of Their Impact on Seed Germination Parameters in Crops. Catalysts 2025, 15, 924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jangir, L.K.; Kumari, Y.; Kumar, A.; Kumar, M.; Awasthi, K. Investigation of luminescence and structural properties of ZnO nanoparticles, synthesized with different precursors. Mater. Chem. Front. 2017, 1, 1413–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Kaur, S.; Kaur, G.; Basu, S.; Rawat, M. Biogenic ZnO nanoparticles: A study of blueshift of optical band gap and photocatalytic degradation of reactive yellow 186 dye under direct sunlight. Green Process. Synth. 2019, 8, 272–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neamah, S.A.; Albukhaty, S.; Falih, I.Q.; Dewir, Y.H.; Mahood, H.B. Biosynthesis of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles Using Capparis spinosa L. Fruit Extract: Characterization, Biocompatibility, and Antioxidant Activity. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 6604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Sinha, O.P.; Srivastava, R.; Srivastava, A.K.; Thomas, S.V.; Sood, K.N.; Kamalasanan, M.N. Surface modified ZnO nanoparticles: Structure, photophysics, and its optoelectronic application. J. Nanopart Res. 2013, 15, 1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Singh, A.; Singh, S.; Singh, R. Synthesis and characterization of ZnO nanoparticles prepared by green routes: Controlling morphologies by maintaining pH. Phys. Scr. 2024, 99, 1059b9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.-M.; Shieh, J.; Chu, P.-Y.; Lee, H.-Y.; Lin, C.-M.; Juang, J.-Y. Enhanced free exciton and direct band-edge emissions at room temperature in ultrathin ZnO films grown on Si nanopillars by atomic layer deposition. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2011, 3, 4415–4419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SMITH, A.M.; NIE, S. Semiconductor Nanocrystals: Structure, Properties, and Band Gap Engineering. Acc. Chem. Res. 2010, 43, 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giles, N.C.; Xu, C.; Callahan, M.J.; Wang, B.; Neal, J.S.; Boatner, L.A. Effects of phonon coupling and free carriers on band-edge emission at room temperature in n-type ZnO crystals. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2006, 89, 251906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willander, M.; Nur, O.; Sadaf, J.R.; Qadir, M.I.; Zaman, S.; Zainelabdin, A.; Bano, N.; Hussain, I. Luminescence from Zinc Oxide Nanostructures and Polymers and their Hybrid Devices. Materials 2010, 3, 2643–2667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayaci, F.; Vempati, S.; Donmez, I.; Biyikli, N.; Uyar, T. Role of zinc interstitials and oxygen vacancies of ZnO in photocatalysis: A bottom-up approach to control defect density. Nanoscale 2014, 6, 10224–10234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Król-Górniak, A.; Railean, V.; Pomastowski, P.; Płociński, T.; Gloc, M.; Dobrucka, R.; Kurzydłowski, K.J.; Buszewski, B. Comprehensive study upon physicochemical properties of bio-ZnO NCs. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basnet, P.; Inakhunbi Chanu, T.; Samanta, D.; Chatterjee, S. A review on bio-synthesized zinc oxide nanoparticles using plant extracts as reductants and stabilizing agents. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2018, 183, 201–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahraman, A.; Socie, E.; Nazari, M.; Kazazis, D.; Buldu-Akturk, M.; Kabanova, V.; Biasin, E.; Smolentsev, G.; Grolimund, D.; Erdem, E.; et al. Tailoring p-Type Behavior in ZnO Quantum Dots through Enhanced Sol–Gel Synthesis: Mechanistic Insights into Zinc Vacancies. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2024, 15, 1755–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knutsen, K.E.; Galeckas, A.; Zubiaga, A.; Tuomisto, F.; Farlow, G.C.; Svensson, B.G.; Kuznetsov, A.Y. Zinc vacancy and oxygen interstitial in ZnO revealed by sequential annealing and electron irradiation. Phys. Rev. B 2012, 86, 121203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayoub, I.; Kumar, V.; Abolhassani, R.; Sehgal, R.; Sharma, V.; Sehgal, R.; Swart, H.C.; Mishra, Y.K. Advances in ZnO: Manipulation of defects for enhancing their technological potentials. Nanotechnol. Rev. 2022, 11, 575–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Fernandez-Alberti, S.; Long, R. Resolving the Puzzle of Charge Carrier Lifetime in ZnO by Revisiting the Role of Oxygen Vacancy. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2024, 15, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Purushotham, D.; Mavinakere Ramesh, A.; Shetty Thimmappa, D.; Kalegowda, N.; Hittanahallikoppal Gajendramurthy, G.; Kollur, S.P.; Mahadevamurthy, M. Green Synthesis of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles Using Aqueous Extract of Pavonia zeylanica to Mediate Photocatalytic Degradation of Methylene Blue: Studies on Reaction Kinetics, Reusability and Mineralization. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 4739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atta, D.; Wahab, H.A.; Ibrahim, M.A.; Battisha, I.K. Photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue dye by ZnO nanoparticle thin films, using Sol–gel technique and UV laser irradiation. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 26961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, X.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, X. Highly Branched Sn-Doped ZnO Nanostructures for Sunlight Driven Photocatalytic Reactions. J. Nanomater. 2014, 2014, 381819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrix, Y.; Rauwel, E.; Nagpal, K.; Haddad, R.; Estephan, E.; Boissière, C.; Rauwel, P. Revealing the Dependency of Dye Adsorption and Photocatalytic Activity of ZnO Nanoparticles on Their Morphology and Defect States. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilyas, A.M.; Musah, J.-D.; Or, S.W.; Awodugba, A.O. Precursor impurity-mediated effect in the photocatalytic activity of precipitated zinc oxide. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2024, 107, 8269–8280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Li, T.; Wen, W.; Luo, X.; Zhao, L. ZnSe/CdSe core-shell nanoribbon arrays for photocatalytic applications. CrystEngComm 2020, 22, 895–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabar, M.B.; Elahi, S.M.; Ghoranneviss, M.; Yousefi, R. Controlled morphology of ZnSe nanostructures by varying Zn/Se molar ratio: The effects of different morphologies on optical properties and photocatalytic performance. CrystEngComm 2018, 20, 4590–4599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etay, H. Kinetics of photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue dye in aqueous medium using ZnO nanoparticles under UV radiation. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 25485–25493. [Google Scholar]

- Lachkar, N.; Lamchouri, F.; Bouabid, K.; Boulfia, M.; Senhaji, S.; Stitou, M.; Toufik, H. Mineral Composition, Phenolic Content, and In Vitro Antidiabetic and Antioxidant Properties of Aqueous and Organic Extracts of Haloxylon scoparium Aerial Parts. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2021, 2021, 9011168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinaldi, R.; Benedetto, A.D.; Cascione, M.; Matteis, V.D.; Corato, R.D.; Corrado, M.; Rinaldi, R. Eco-Friendly TiO2 Nanoparticles: Harnessing Aloe Vera for Superior Photocatalytic Degradation of Methylene Blue. Catalysts 2024, 14, 820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirza, S.; Hussaini, A.A.; Ozturk, G.; Turgut, M.; Ozturk, T.; Tugay, O.; Ulukus, D.; Yildirim, M. Photocatalytic and antibacterial activities of ZnO nanoparticles synthesized from Lupinus albus and Lupinus pilosus plant extracts via green synthesis approach. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2023, 155, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, A.; Patel, A.S.; Chakraborti, A.; Singh, K.; Sharma, P. Enhanced photocatalytic activity of plasmonic Au nanoparticles incorporated MoS2 nanosheets for degradation of organic dyes. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2021, 32, 6168–6184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouni, S.; Yahia, F.; BelHaj Mohamed, N.; Bouzidi, M.; Alshammari, A.S.; Abdulaziz, F.; Bonilla-Petriciolet, A.; Mohamed, M.; Khan, Z.R.; Chaaben, N.; et al. Effective removal of textile dye via synergy of adsorption and photocatalysis over ZnS nanoparticles: Synthesis, modeling, and mechanism. Heliyon 2024, 10, e36949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alprol, A.E.; Eleryan, A.; Abouelwafa, A.; Gad, A.M.; Hamad, T.M. Green synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles using Padina pavonica extract for efficient photocatalytic removal of methylene blue. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 32160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houas, A.; Lachheb, H.; Ksibi, M.; Elaloui, E.; Guillard, C.; Herrmann, J.-M. Photocatalytic degradation pathway of methylene blue in water. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2001, 31, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Crystallite Size D (nm) | Dominant Plans dhkl | Lattice Constant (Å) | Strain(ε) | Dislocation Density (δ) (lines/m2) × 1015 | Stacking Fault (SF) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZnO-P1 | 10.93 | −101 | a = 3.23 c = 5.21 | 0.0032 | 8.37 | 0.006 |

| ZnO-P2 | 8.95 | −101 | a = 3.19 c = 5.15 | 0.0041 | 12.48 | 0.0077 |

| Nanoparticles | Peaks (nm) | FWHM (nm) |

|---|---|---|

| ZnO-P1 | Peak 1 = 370 | 4.26 |

| Peak 2 = 377 | 10.57 | |

| Peak 3 = 389 | 7.21 | |

| Peak 4 = 396 | 9.97 | |

| Peak 5 = 410 | 12.99 | |

| Peak 6 = 430 | 60.81 | |

| ZnO-P2 | Peak 1 = 366 | 50.43 |

| Peak 2 = 408 | 42.84 | |

| Peak 3 = 442 | 83.57 | |

| Peak 4 = 497 | 73.46 | |

| ZnO-Ref | Peak 1 = 376 | 47.4 |

| Peak 2 = 409 | 61.04 | |

| Peak 3 = 452 | 33.33 | |

| Peak 4 = 462 | 115.06 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Alzahrani, E.A.; Ouni, S.; Bouzidi, M.; Alshammari, A.S.; Alshammari, A.F.; Ali, R.; Alshammari, O.A.O.; Mohamed, N.B.; Chaaben, N. Eco-Friendly Synthesis of ZnO-Based Nanocomposites Using Haloxylon and Calligonum Extracts for Enhanced Photocatalytic Degradation of Methylene Blue. J. Compos. Sci. 2026, 10, 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs10010018

Alzahrani EA, Ouni S, Bouzidi M, Alshammari AS, Alshammari AF, Ali R, Alshammari OAO, Mohamed NB, Chaaben N. Eco-Friendly Synthesis of ZnO-Based Nanocomposites Using Haloxylon and Calligonum Extracts for Enhanced Photocatalytic Degradation of Methylene Blue. Journal of Composites Science. 2026; 10(1):18. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs10010018

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlzahrani, Elham A., Sabri Ouni, Mohamed Bouzidi, Abdullah S. Alshammari, Ahlam F. Alshammari, Rizwan Ali, Odeh A. O. Alshammari, Naim Belhaj Mohamed, and Noureddine Chaaben. 2026. "Eco-Friendly Synthesis of ZnO-Based Nanocomposites Using Haloxylon and Calligonum Extracts for Enhanced Photocatalytic Degradation of Methylene Blue" Journal of Composites Science 10, no. 1: 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs10010018

APA StyleAlzahrani, E. A., Ouni, S., Bouzidi, M., Alshammari, A. S., Alshammari, A. F., Ali, R., Alshammari, O. A. O., Mohamed, N. B., & Chaaben, N. (2026). Eco-Friendly Synthesis of ZnO-Based Nanocomposites Using Haloxylon and Calligonum Extracts for Enhanced Photocatalytic Degradation of Methylene Blue. Journal of Composites Science, 10(1), 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs10010018