Functional Nanocomposites with a Positive Temperature Coefficient of Resistance Based on Carbon Nanotubes Synthesized by Laser Ablation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

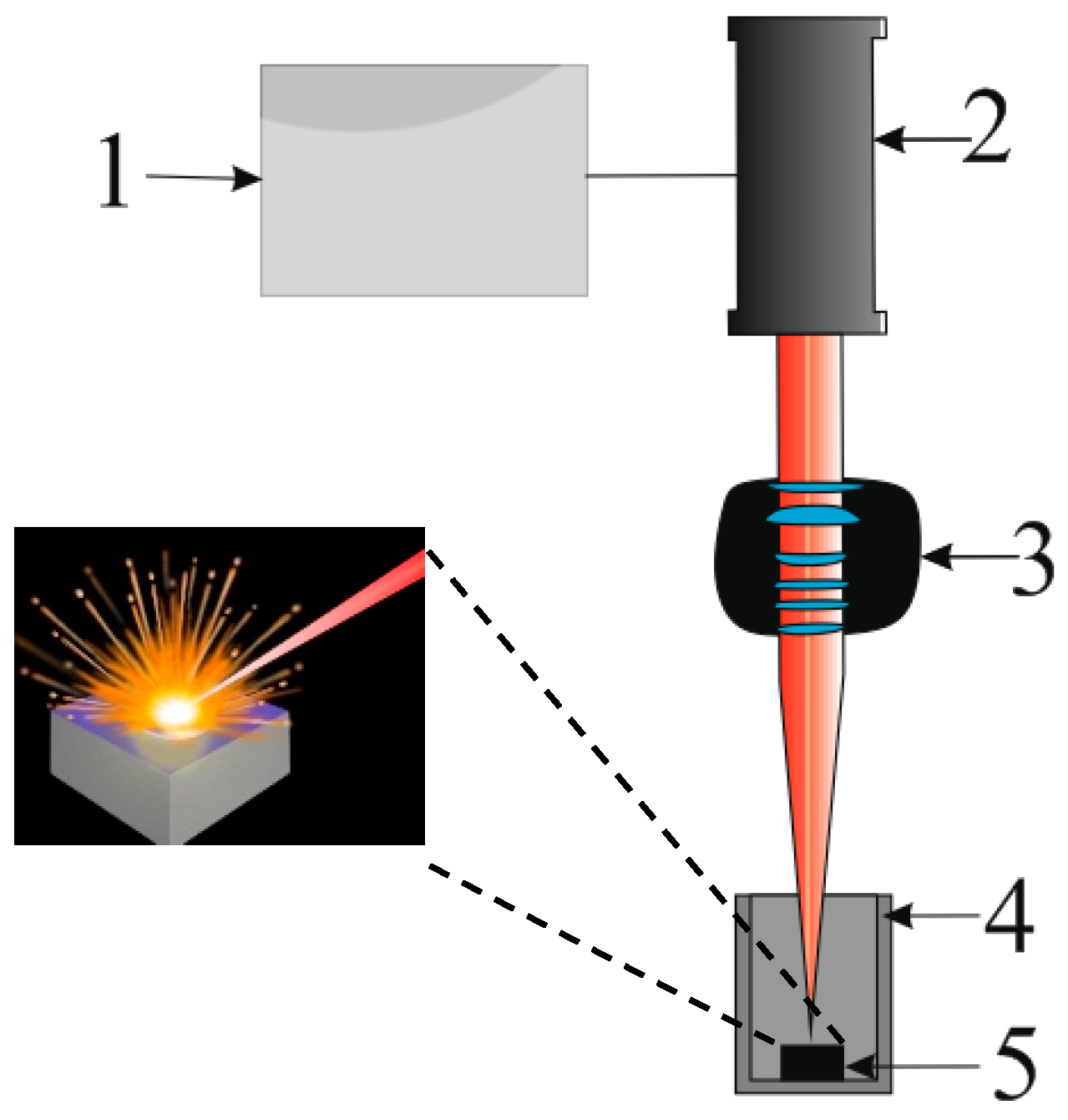

2.1. Synthesis of Carbon Nanotubes by Laser Ablation

2.2. Manufacture of Conductive Nanocomposite

2.3. Characterization

2.4. Specific Surface Area Measurement and Identification of Synthesized CNTs

2.5. Non-Contact Temperature Investigation Methodology

3. Results and Discussion

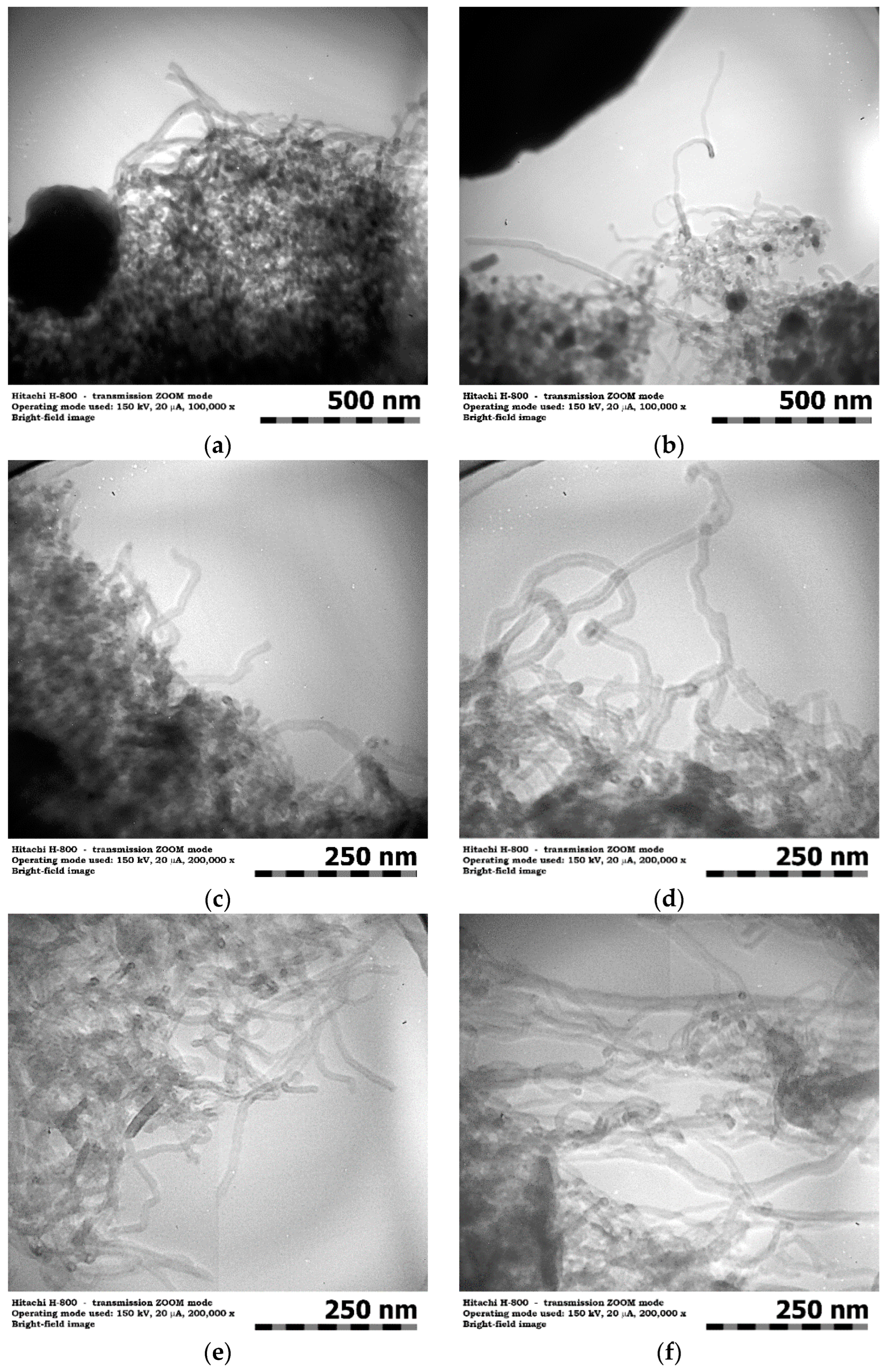

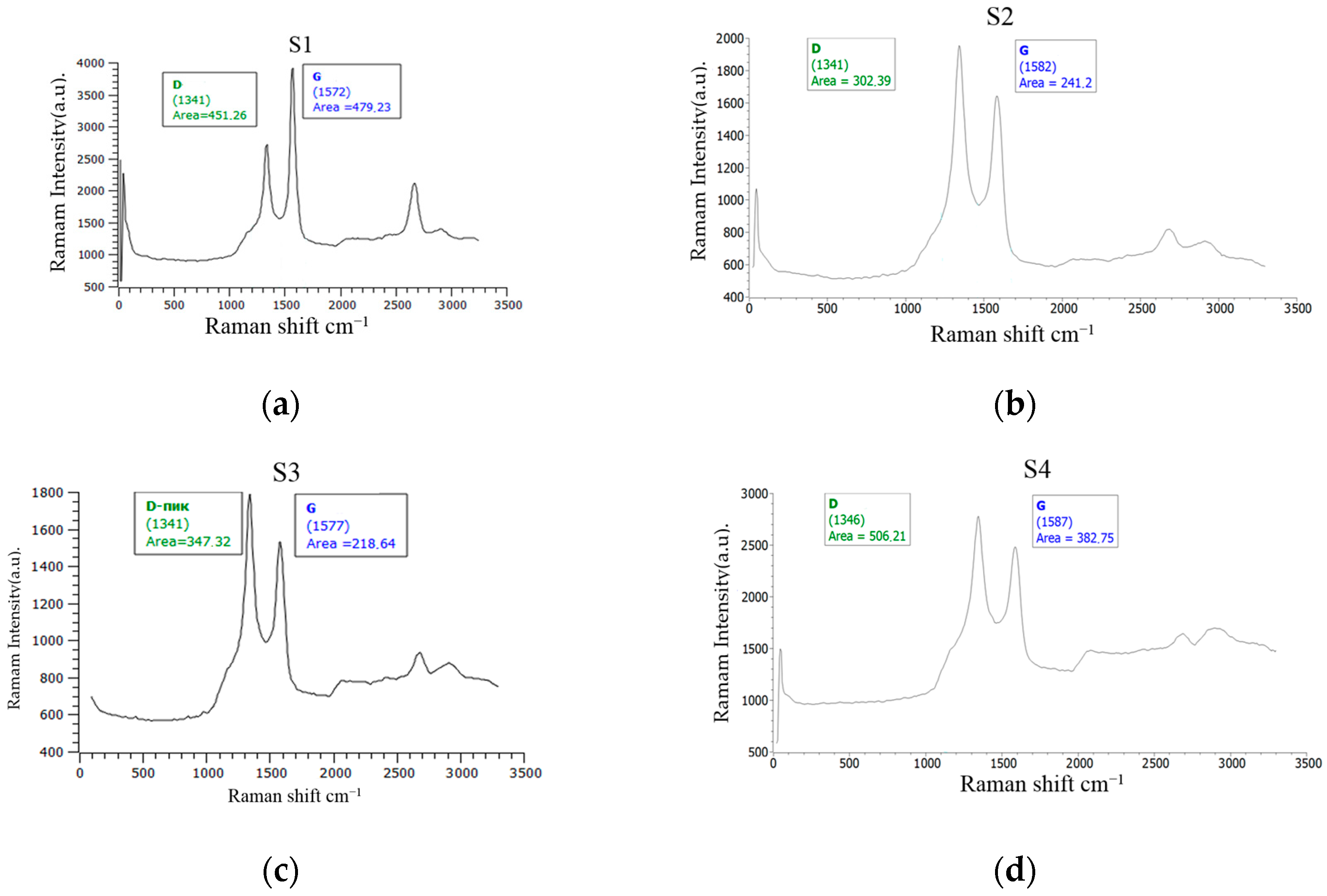

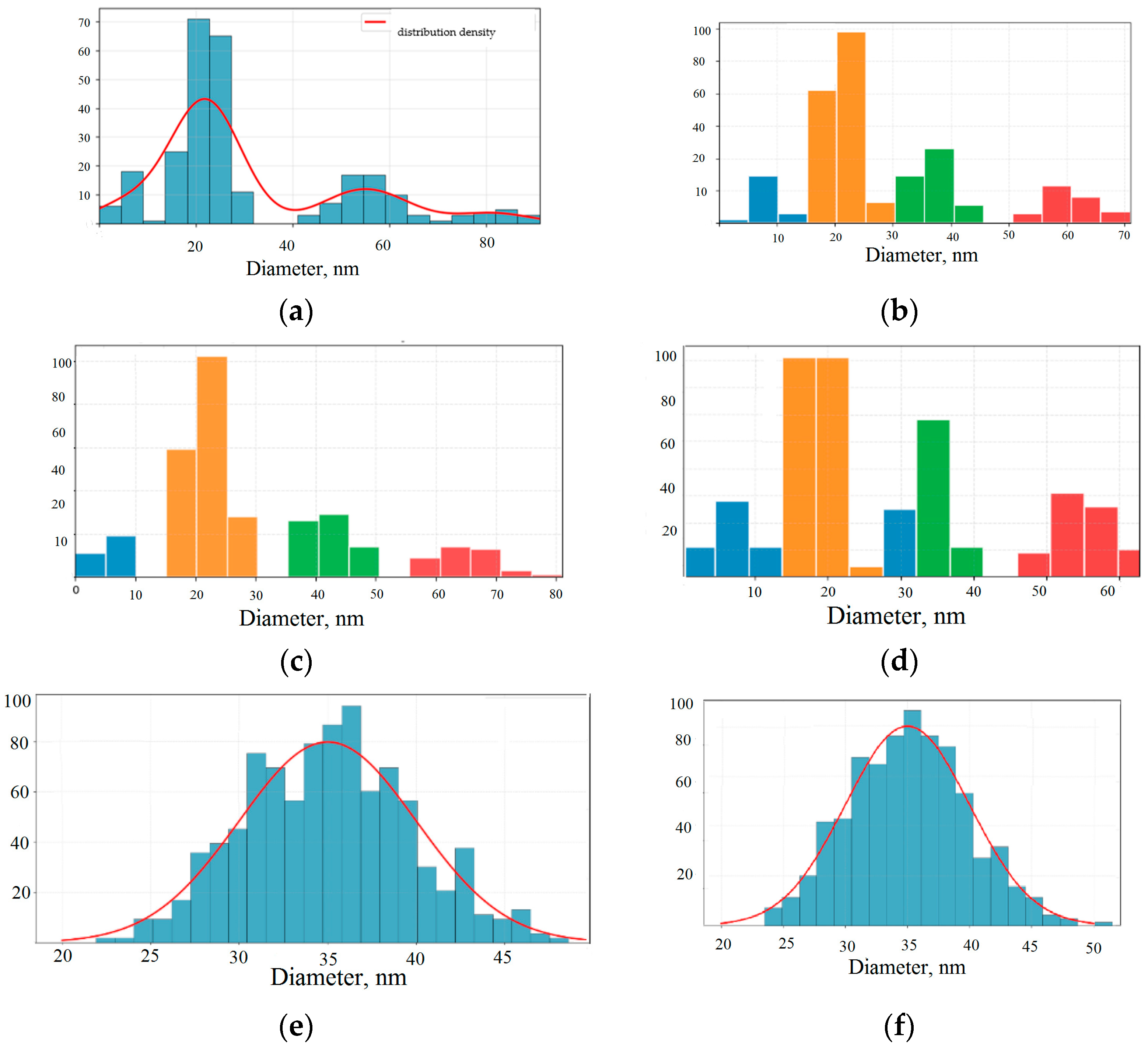

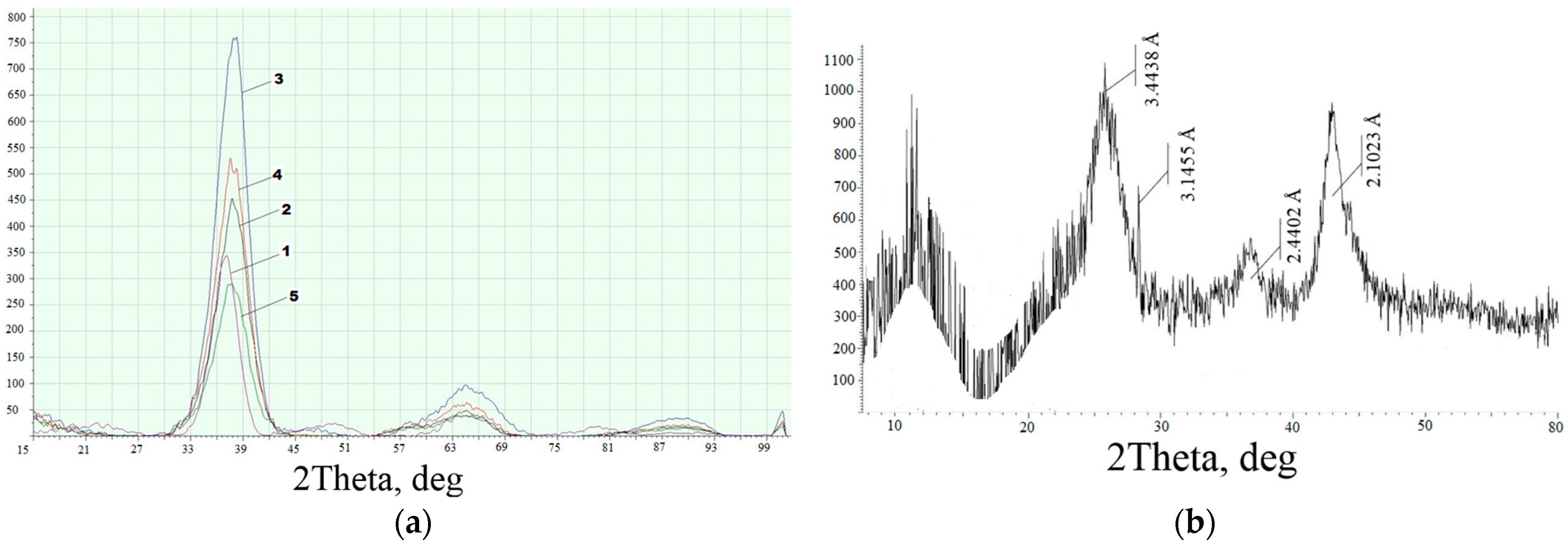

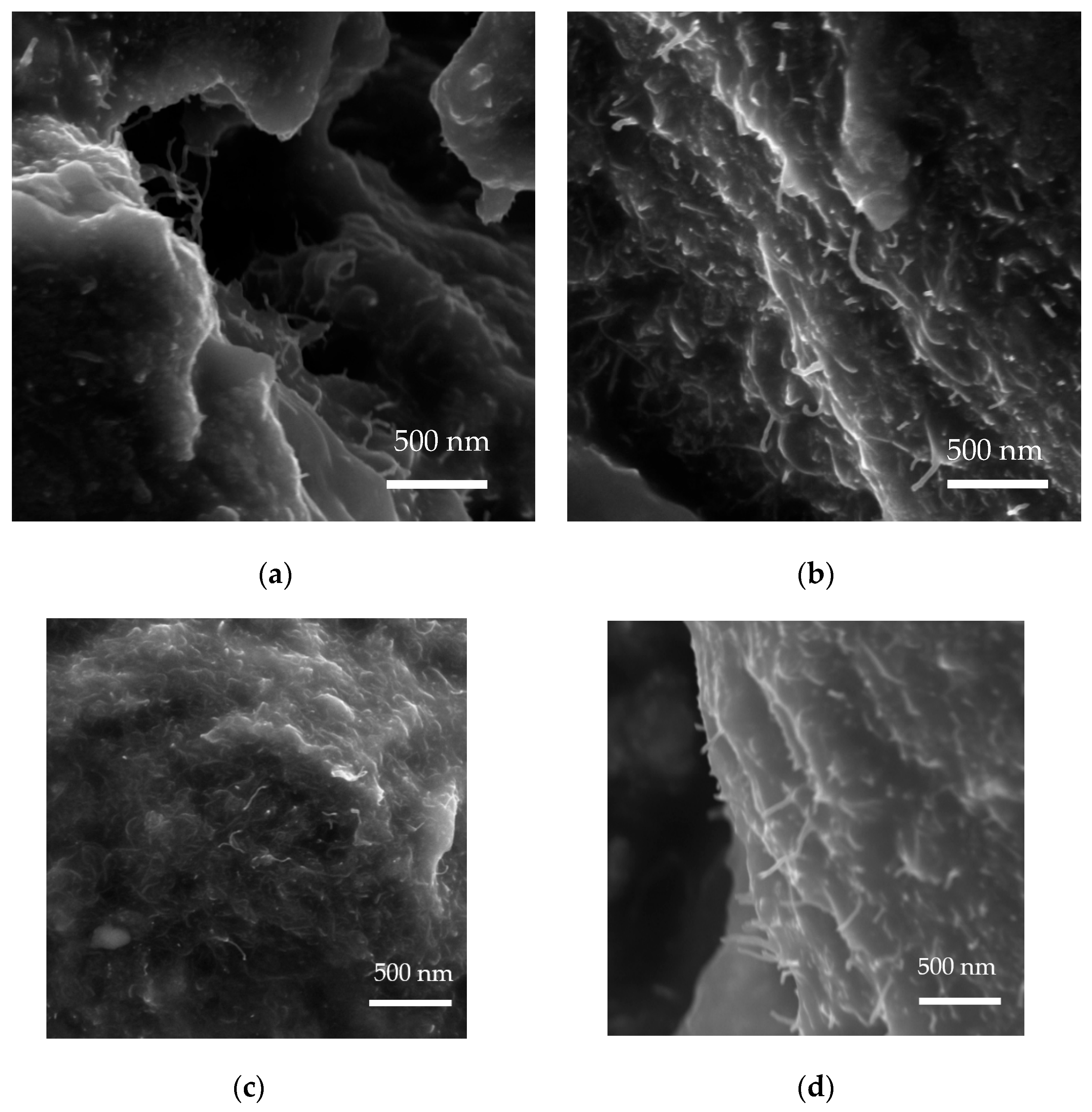

3.1. Analysis of the Morphology and Microstructure of Synthesized CNTs

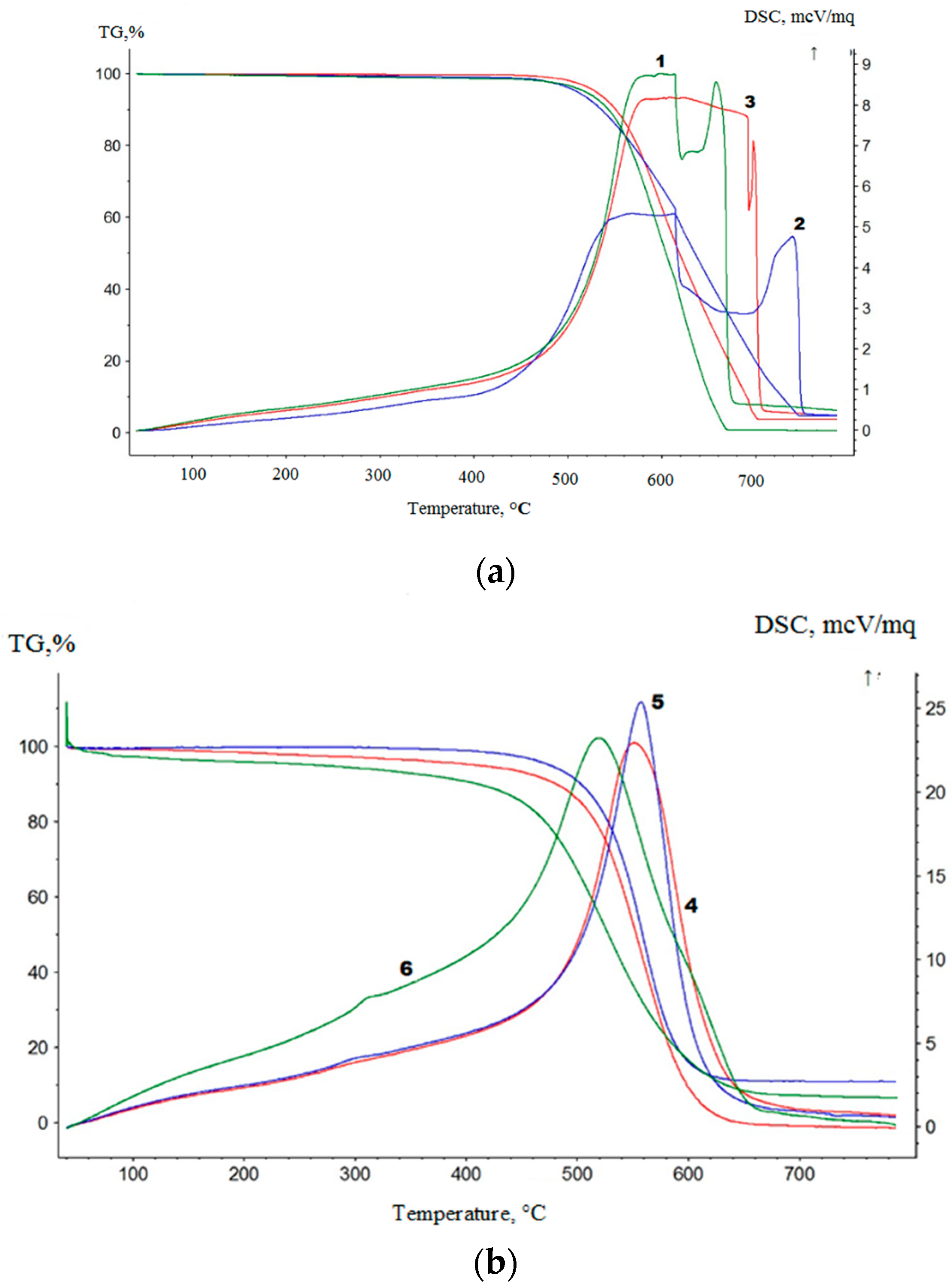

3.2. Thermal Analysis of Synthesized CNTs

3.3. Analysis of the Thermal Behavior of an MWCNTs/Elastomer Under Mechanical Deformation

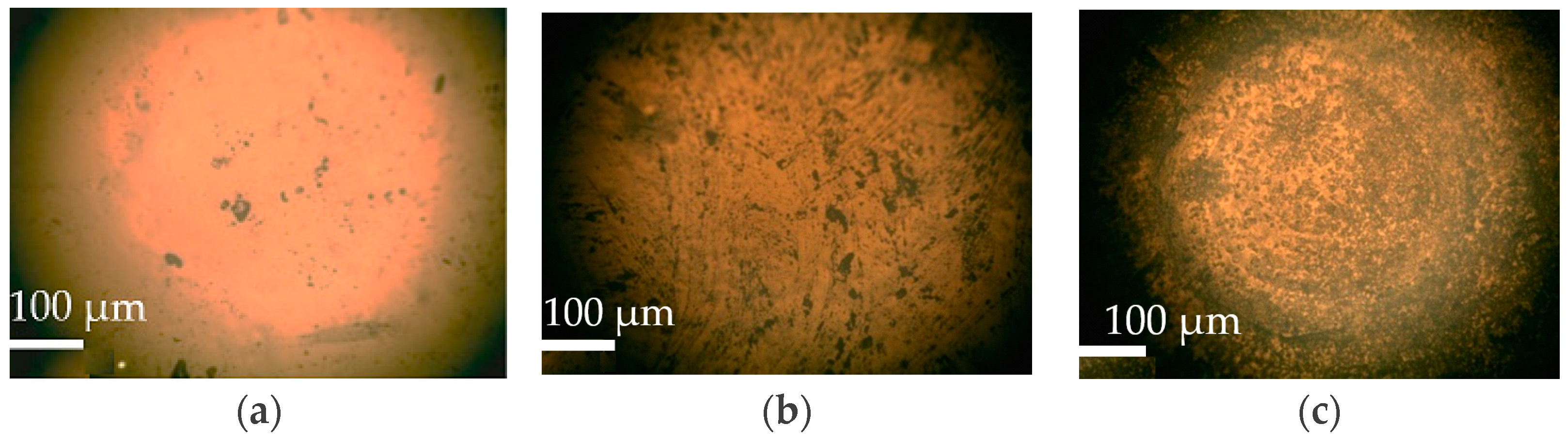

3.4. Performance Evaluation of Heating Elements Under Ice Accretion Conditions

3.5. Analysis of Self-Regulating Properties and Comparative Characteristics of Heating Elements

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CNM | carbon nanomaterials |

| CNT | carbon nanotubes |

| DSC | differential scanning calorimetry |

| MWCNT | multi-walled carbon nanotubes |

| SEM | scanning electron microscopy |

| TG | thermally expandable graphite |

References

- Alsulami, Q.A.; Rajeh, A. Modification and development in the microstructure of PVA/CMC-GO/Fe3O4 nanocomposites films as an application in energy storage devices and magnetic electronics industry. Ceram. Int. 2023, 49, 14399–14407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodson, A.D.; Rick, M.S.; Troxler, J.E.; Ashbaugh, H.S.; Albert, J.N.L. Blending linear and cyclic block copolymers to manipulate nanolithographic feature dimensions. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2021, 4, 327–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tazwar, H.T.; Antora, M.F.; Nowroj, I.; Rashid, A.B. Conductive polymer composites in soft robotics, flexible sensors and energy storage: Fabrication, applications and challenges. Biosens. Bioelectron. X 2025, 24, 100597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díez-Pascual, A.M. Carbon-Based Polymer Nanocomposites for High-Performance applications. Polymers 2020, 12, 872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shchegolkov, A.V.; Shchegolkov, A.V.; Kaminskii, V.V.; Iturralde, P.; Chumak, M.A. Advances in electrically and thermally conductive functional nanocomposites based on carbon nanotubes. Polymers 2024, 17, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Liang, T.; Shi, M.; Chen, H. Graphene-Like Two-Dimensional Materials. Chem. Rev. 2013, 113, 3766–3798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Z.U.; Kausar, A.; Ullah, H. A review on Composite Papers of graphene oxide, carbon nanotube, Polymer/GO, and Polymer/CNT: Processing Strategies, Properties, and Relevance. Polym.-Plast. Technol. Eng. 2015, 55, 559–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colomer, J.-F.; Stephan, C.; Lefrant, S.; Van Tendeloo, G.; Willems, I.; Kónya, Z.; Fonseca, A.; Laurent, C.; Nagy, J.B. Large-scale synthesis of single-wall carbon nanotubes by catalytic chemical vapor deposition (CCVD) method. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2000, 317, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khavrus, V.O.; Lemesh, N.V.; Gordijchuk, S.V.; Tripolsky, A.I.; Ivashchenko, T.S.; Biliy, M.M.; Strizhak, P.E. Chemical catalytic vapor deposition (CCVD) synthesis of carbon nanotubes by decomposition of ethylene on metal (Ni, Co, Fe) nanoparticles. React. Kinet. Catal. Lett. 2008, 93, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Wu, H.; Deng, Y.; Miao, R.; Lai, D.; Deng, J.; Zhang, J.; Chen, Q.; Shao, Q.; Shao, C. Synthesis of high-quality multi-walled carbon nanotubes by arc discharge in nitrogen atmosphere. Vacuum 2024, 225, 113198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, R.; Shahnavaz, Z.; Ali, M.E.; Islam, M.M.; Hamid, S.B.A. Can we optimize arc discharge and laser ablation for Well-Controlled Carbon Nanotube synthesis? Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2016, 11, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shukla, P.; Saxena, P. Polymer Nanocomposites in Sensor Applications: A Review on Present Trends and Future Scope. Chin. J. Polym. Sci. 2021, 39, 665–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Zhao, L.; Zeng, Y.; Zhang, L.; Li, F.; Liu, P.; Liu, C. Comparison of electrical properties between multi-walled carbon nanotube and graphene nanosheet/high density polyethylene composites with a segregated network structure. Carbon 2010, 49, 1094–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.T.; Shahid, M.A.; Mahmud, N.; Habib, A.; Rana, M.M.; Khan, S.A.; Hossain, M.D. Research and application of polypropylene: A review. Discov. Nano 2024, 19, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Bian, L. Influence of agglomeration parameters on carbon nanotube composites. Acta Mech. 2017, 228, 2207–2217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Hu, C.; Zhai, W.; Zhao, S.; Zheng, G.; Dai, K.; Liu, C.; Shen, C. Particle size induced tunable positive temperature coefficient characteristics in electrically conductive carbon nanotubes/polypropylene composites. Mater. Lett. 2016, 182, 314–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiyanova, K.A.; Gudkov, M.V.; Torkunov, M.K.; Goncharuk, G.P.; Gulin, A.A.; Sysa, A.V.; Ryvkina, N.G.; Bazhenov, S.L.; Melnikov, V.P. Effect of reduced graphene oxide, multi-walled carbon nanotubes and their mixtures on the electrical conductivity and mechanical properties of a polymer composite with a segregated structure. J. Compos. Mater. 2022, 57, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taib, N.-A.A.B.; Rahman, M.R.; Matin, M.M.; Uddin, J.; Bakri, M.K.B.; Khan, A. A Review on Carbon Nanotubes (CNT): Structure, Synthesis, Purification and Properties for Modern day Applications. Res. Sq. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, M.; Xia, K.; Wang, Q.; Yin, Z.; Wang, H.; Wang, C.; Xie, H.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, Y. Flexible and highly sensitive pressure sensors based on bionic hierarchical structures. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2017, 27, 1606066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Zhi, C.; Lin, Y.; Bao, H.; Wu, G.; Jiang, P.; Mai, Y.-W. Thermal conductivity of graphene-based polymer nanocomposites. Mater. Sci. Eng. R Rep. 2020, 142, 100577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yablokov, M.Y.; Kuznetsov, A.A. Electret properties and wettability of polymer materials treated by DC glow discharge. Phys. Complex Syst. 2024, 5, 202–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmatiy, G.Y.; Kalynyak, B.M.; Kutniv, M.V. Uncoupled quasistatic problem of thermoelasticity for a Two-Layer hollow thermally sensitive cylinder under the conditions of convective heat exchange. J. Math. Sci. 2021, 256, 439–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokobza, L. Elastomer nanocomposites: Effect of Filler–Matrix and Filler–Filler interactions. Polymers 2023, 15, 2900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martone, A.; Faiella, G.; Antonucci, V.; Giordano, M.; Zarrelli, M. The effect of the aspect ratio of carbon nanotubes on their effective reinforcement modulus in an epoxy matrix. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2011, 71, 1117–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anusak, N.; Virtanen, J.; Kangas, V.; Promarak, V.; Yotprayoonsak, P. Enhanced Joule heating performance of flexible transparent conductive double-walled carbon nanotube films on sparked Ag nanoparticles. Thin Solid Film. 2022, 750, 139201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, B.; Yu, X.; Wang, Y.; Porwal, H.; Evans, J.; Newton, M.; Papageorgiou, D.; Zhang, H.; Bilotti, E. High temperature co-polyester thermoplastic elastomer nanocomposites for flexible self-regulating heating devices. Mater. Des. 2024, 242, 113000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulhameed, A.; Halin, I.A.; Mohtar, M.N.; Hamidon, M.N. Airflow-assisted dielectrophoresis to reduce the resistance mismatch in carbon nanotube-based temperature sensors. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 39311–39318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Yan, D.; Huang, H.; Dai, K.; Li, Z. Positive temperature coefficient and time-dependent resistivity of carbon nanotubes (CNTs)/ultrahigh molecular weight polyethylene (UHMWPE) composite. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2009, 114, 1002–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shchegolkov, A.; Shchegolkov, A.; Zemtsova, N.; Vetcher, A.; Stanishevskiy, Y. Properties of Organosilicon Elastomers Modified with Multilayer Carbon Nanotubes and Metallic (Cu or Ni) Microparticles. Polymers 2024, 16, 774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yudasaka, M.; Kokai, F.; Takahashi, K.; Yamada, R.; Sensui, N.; Ichihashi, T.; Iijima, S. Formation of Single-Wall carbon nanotubes: Comparison of CO2 laser ablation and ND:YAG laser ablation. J. Phys. Chem. B 1999, 103, 3576–3581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danilov, P.A.; Ionin, A.A.; Kudryashov, S.I.; Makarov, S.V.; Mel’nik, N.N.; Rudenko, A.A.; Yurovskikh, V.I.; Zayarny, D.V.; Lednev, V.N.; Obraztsova, E.D.; et al. Femtosecond laser ablation of single-wall carbon nanotube-based material. Laser Phys. Lett. 2014, 11, 106101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, L.; Zuo, P.; Li, F.; Wang, G.; Zhang, K.; Tian, H.; Han, W.; Liu, S.; Xu, R.; Huo, Y.; et al. Femtosecond laser processing of carbon nanotubes: Synthesis, surface modification, and cutting. Nanoscale 2025, 17, 19590–19612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habeeb, N.F.D.; Khashan, N.K.S.; Hadi, N.A.A.; Sadia, N.H. A review of carbon nanotubes and alloys synthesized by the laser ablation technique. Int. J. Nanoelectron. Mater. (IJNeaM) 2025, 18, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baroot, A.A.; Elsayed, K.A.; Haladu, S.A.; Magami, S.M.; Alheshibri, M.; Ercan, F.; Çevik, E.; Akhtar, S.; AManda, A.; Kayed, T.S.; et al. One-pot synthesis of SnO2 nanoparticles decorated multi-walled carbon nanotubes using pulsed laser ablation for photocatalytic applications. Opt. Laser Technol. 2022, 157, 108734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baroot, A.A.; Elsayed, K.A.; Khan, F.A.; Haladu, S.A.; Ercan, F.; Çevik, E.; Drmosh, Q.A.; Almessiere, M.A. Anticancer activity of AU/CNT nanocomposite fabricated by nanosecond pulsed laser ablation method on colon and cervical cancer. Micromachines 2023, 14, 1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonathan, F.; Ahmad, H.Z.; Nida, K.; Khumaeni, A. Characteristics and antibacterial properties of carbon nanoparticles synthesized by the pulsed laser ablation method in various liquid media. Environ. Nanotechnol. Monit. Manag. 2023, 21, 100909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Merino, J.A.; Villarroel, R.; Chávez-Ángel, E.; Hevia, S.A. Laser ablation fingerprint in low crystalline carbon nanotubes: A structural and photothermal analysis. Opt. Laser Technol. 2024, 178, 111255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Li, N.; Kang, J.; Li, Z.; Hong, N.; Han, S.; Chen, L.; Zhang, S.; Liu, C.; Song, C.; et al. Heterostructure-anchored 3D CNT-bridged graphene architecture via layer-by-layer structural engineering for thick electrodes of supercapacitors. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 497, 154557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, H.-Y.; Chen, Y.-H.; Wang, K.-C.; Leu, P.W.; Leu, M.C. Study on field emission characteristics of carbon nanotube arrays patterned via laser welding of dissimilar materials. CIRP Ann. 2025, 74, 275–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vennam, G.; Singh, A.; Dunlop, A.R.; Islam, S.; Weddle, P.J.; Mak, B.W.; Tancin, R.; Evans, M.C.; Trask, S.E.; Dufek, E.J.; et al. Fast-charging lithium-ion batteries: Synergy of carbon nanotubes and laser ablation. J. Power Sources 2025, 636, 236566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaheen, M.E.; Abdelwahab, A.Y.E. Laser ablation in liquids: A versatile technique for nanoparticle generation. Opt. Laser Technol. 2025, 186, 112705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazemizadeh, F.; Bellah, S.M.; Malekfar, R. Optimization of cooling devices used in laser ablation setups for carbon nanotube synthesis. J. Laser Appl. 2017, 29, 042004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eason, R. Pulsed Laser Deposition of Thin Films; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yogesh, G.K.; Shukla, S.; Sastikumar, D.; Koinkar, P. Progress in pulsed laser ablation in liquid (PLAL) technique for the synthesis of carbon nanomaterials: A review. Appl. Phys. A 2021, 127, 810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar-Alarcón, L.; Espinosa-Pesqueira, M.E.; Solis-Casados, D.A.; Gonzalo, J.; Solis, J.; Martinez-Orts, M.; Haro-Poniatowski, E. Two-dimensional carbon nanostructures obtained by laser ablation in liquid: Effect of an ultrasonic field. Appl. Phys. A 2018, 124, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerasimenko, A.Y.; Kitsyuk, E.P.; Kuksin, A.V.; Ryazanov, R.M.; Savitskiy, A.I.; Savelyev, M.S.; Pavlov, A.A. Influence of laser structuring and barium nitrate treatment on morphology and electrophysical characteristics of vertically aligned carbon nanotube arrays. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2019, 96, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kichambare, P.D.; Chen, L.C.; Wang, C.T.; Ma, K.J.; Wu, C.T.; Chen, K.H. Laser irradiation of carbon nanotubes. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2001, 72, 218–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerasimenko, A.Y.; Kuksin, A.V.; Shaman, Y.P.; Kitsyuk, E.P.; Fedorova, Y.O.; Sysa, A.V.; Pavlov, A.A.; Glukhova, O.E. Electrically Conductive Networks from Hybrids of Carbon Nanotubes and Graphene Created by Laser Radiation. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bystrzejewski, M.; Rümmeli, M.H.; Lange, H.; Huczko, A.; Baranowski, P.; Gemming, T.; Pichler, T. Single-Walled carbon Nanotubes Synthesis: A direct comparison of laser ablation and carbon arc routes. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2008, 8, 6178–6186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorbunov, A.A.; Graff, A.; Jost, O.; Pompe, W. Mechanism of carbon nanotube synthesis by laser ablation. Proc. SPIE Int. Soc. Opt. Eng. 2001, 4423, 212–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bal’makov, M.D.; Muradova, G.M. Control of the synthesis of nanostructured materials under laser and microwave irradiation. Glass Phys. Chem. 2010, 36, 116–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlov, G.I.; Assovskii, I.G. Synthesis of single-walled carbon nanotubes in an expanding vapor-gas flow produced by laser ablation of a graphite-catalyst mixture. Tech. Phys. 2003, 48, 1436–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, Q.; Tanaka, T.; Mesko, M.; Ogino, A.; Nagatsu, M. Characteristics of graphene-layer encapsulated nanoparticles fabricated using laser ablation method. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2007, 17, 664–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, L.; Sun, J. Mechanical Properties of Carbon Nanotubes-Polymer Composites; InTechOpen: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B. Carbon nanotubes and their polymeric composites: The applications in tissue engineering. Biomanuf. Rev. 2020, 5, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arepalli, S. Laser ablation process for Single-Walled carbon nanotube production. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2004, 4, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazakova, M.A.; Selyutin, A.G.; Semikolenova, N.V.; Ishchenko, A.V.; Moseenkov, S.I.; Matsko, M.A.; Zakharov, V.A.; Kuznetsov, V.L. Structure of the in situ produced polyethylene based composites modified with multi-walled carbon nanotubes: In situ synchrotron X-ray diffraction and differential scanning calorimetry study. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2018, 167, 148–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schawe, J.E.K.; Pötschke, P.; Alig, I. Nucleation efficiency of fillers in polymer crystallization studied by fast scanning calorimetry: Carbon nanotubes in polypropylene. Polymer 2017, 116, 160–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadegh, H.; Shahryari-Ghoshekandi, R.; Kazemi, M. Study in synthesis and characterization of carbon nanotubes decorated by magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles. Int. Nano Lett. 2014, 4, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hároz, E.H.; Duque, J.G.; Rice, W.D.; Densmore, C.G.; Kono, J.; Doorn, S.K. Resonant Raman spectroscopy of armchair carbon nanotubes: Absence of broadG−feature. Phys. Rev. B 2011, 84, 121403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moura, L.G.; Moutinho, M.V.O.; Venezuela, P.; Mauri, F.; Righi, A.; Strano, M.S.; Fantini, C.; Pimenta, M.A. The double-resonance Raman spectra in single-chirality (n, m) carbon nanotubes. Carbon 2017, 117, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolotov, V.V.; Kan, V.E.; Knyazev, E.V.; Korusenko, P.M.; Nesov, S.N.; Sten’kin, Y.A.; Sachkov, V.A.; Ponomareva, I.V. An observation of the radial breathing mode in the Raman spectra of CVD-grown multi-wall carbon nanotubes. New Carbon Mater. 2015, 30, 385–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Chen, K.; He, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wu, C.; Wang, J.; Liao, J.H.; Liu, S.H. Formation and Raman spectroscopy of single wall carbon nanotubes synthesized by CO2 continuous laser vaporization. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2001, 62, 2007–2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saranya, M.; Kekkonen, J.; Pitkänen, O.; Talala, T.; Nissinen, I.; Schmid, R.; Lorite, G.S. Carbon nanotube profiling in biological media via advanced Raman spectroscopy techniques. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2025, 349, 127357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Kitahama, Y.; Sato, H.; Suzuki, T.; Han, X.; Itoh, T.; Bokobza, L.; Ozaki, Y. Laser heating effect on Raman spectra of styrene–butadiene rubber/multiwalled carbon nanotube nanocomposites. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2011, 523, 87–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, P.; Mohapatra, D.R.; Hazra, K.S.; Misra, D.S.; Ghatak, J.; Satyam, P.V. Appearance of radial breathing modes in Raman spectra of multi-walled carbon nanotubes upon laser illumination. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2008, 455, 83–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Kim, B.; Jeong, Y.G. Thermomechanical and electrical properties of PDMS/MWCNT composite films crosslinked by electron beam irradiation. J. Mater. Sci. 2015, 50, 5599–5608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, Y.G.; Jeon, G.W. Microstructure and performance of multiwalled carbon Nanotube/M-Aramid composite films as electric heating elements. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2013, 5, 6527–6534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, J.; Jeong, Y.G. Multiwalled carbon nanotube/polydimethylsiloxane composite films as high performance flexible electric heating elements. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2014, 105, 051907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Jeong, Y.G. Highly elastic and transparent multiwalled carbon nanotube/polydimethylsiloxane bilayer films as electric heating materials. Mater. Des. 2015, 86, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Lu, H.; Zhang, Q.; Yao, Y.; Chen, M.; Li, Q. Flexible carbon nanotube/polyurethane electrothermal films. Carbon 2016, 110, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.-W.; Lee, S.-E.; Jeong, Y.G. Carbon nanotube/cellulose papers with high performance in electric heating and electromagnetic interference shielding. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2016, 131, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, D.; Yoon, H.N.; Seo, J.; Park, S.; Kil, T.; Lee, H.K. Improved electric heating characteristics of CNT-embedded polymeric composites with an addition of silica aerogel. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2021, 212, 108866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoecker, C.; Smail, F.; Pick, M.; Boies, A. The influence of carbon source and catalyst nanoparticles on CVD synthesis of CNT aerogel. Chem. Eng. J. 2016, 314, 388–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shchegolkov, A.V.; Babaev, A.A.; Shchegolkov, A.V.; Chumak, M.A. Synthesis of carbon nanotubes by Microwave Method: Mathematical modeling and Practical implementation. Theor. Found. Chem. Eng. 2024, 58, 929–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shchegolkov, A.V.; Nachtane, M.; Stanishevskiy, Y.M.; Dodina, E.P.; Rejepov, D.T.; Vetcher, A.A. The effect of Multi-Walled carbon nanotubes on the Heat-Release properties of elastic nanocomposites. J. Compos. Sci. 2022, 6, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colomer, J.-F.; Piedigrosso, P.; Fonseca, A.; Nagy, J.B. Different purification methods of carbon nanotubes produced by catalytic synthesis. Synth. Met. 1999, 103, 2482–2483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelghany, I.A.H.; Lu, P.; Ummethala, R.; Saif, O.; Ohlckers, P.; Soltani, N. Enhanced CNT electrode production via optimized roll-to-roll CVD reactor geometry and gas flow rate: A pathway to cost-effective supercapacitors. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2025, 347, 131441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sain, S.; Chowdhury, S.; Maity, S.; Maity, G.; Roy, S.S. Sputtered thin film deposited laser induced graphene based novel micro-supercapacitor device for energy storage application. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 16289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chrzanowska, J.; Hoffman, J.; Małolepszy, A.; Mazurkiewicz, M.; Kowalewski, T.A.; Szymanski, Z.; Stobinski, L. Synthesis of carbon nanotubes by the laser ablation method: Effect of laser wavelength. Phys. Status Solidi B 2015, 252, 1860–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thongpool, V.; Denchitcharoen, S.; Asanithi, P.; Limsuwan, P. Preparation of Carbon Nanoparticles by Long Pulsed Laser Ablation in Water with Different Laser Energies. Adv. Mater. Res. 2011, 214, 402–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Aspect of Synthesis | Physical Essence | Role in the Synthesis of Carbon Nanostructures | Examples/Effects in Materials |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ultrafast Heating and Cooling |

|

| |

| Localized Energy Delivery | Non-contact action by a focused beam on micro-areas [46] | Spatially selective modification of structure [47] | Laser “welding” of CNTs with graphene [48] |

| Special Reaction Kinetics | Controlled synthesis of nanostructures under non-equilibrium conditions [51,52] | Encapsulation of nanoparticles in a graphene layer [53] |

| № | Sample | Synthesis Time, s | Ratio of Fe(C5H5)2 to Graphite |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | S1 | 0.1 | 3:1 |

| 2 | S2 | 0.1 | 4:1 |

| 3 | S3 | 0.1 | 5:1 |

| 4 | S4 | 0.1 | 6:1 |

| 5 | S5 | 0.1 | 7:1 |

| 6 | S6 | 0.1 | 8:1 |

| Sample | Ratio of Ferrocene to Graphite | ID/IG Ratio Values for CNTs | Syд, m2/g |

|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | 3:1 | 0.853 | 215 |

| S2 | 4:1 | 0.847 | 242 |

| S3 | 5:1 | 0.85 | 275 |

| S4 | 6:1 | 0.848 | 255 |

| S5 | 7:1 | 0.848 | 243 |

| S6 | 8:1 | 0.850 | 240 |

| Materials | Method of Production | Size, mm | Voltage, V | Tensile Strength | Literary Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MWCNT/PDMS | Casting mortar | 20 × 5 | 35 | Changes | [67] |

| MWCNT/M-Aramid | Casting mortar | 40 × 5 | 10 | Non-stretchable | [68] |

| MWCNT/TPU | Casting mortar | 30 × 10 | 10 | Changes | [69] |

| MWCNT/PDMS | Casting mortar and electron beam radiation | 20 × 5 | 35 | Changes | [70] |

| carbon nanotube/polyurethane | Casting mortar | 20 × 5 | 10 | Changes | [71] |

| MWCNT/PDMS | Spray coating | 20 × 0.5 | 110 | Changes | [72] |

| MWCNT/PDMS | Casting mortar | - | 5 | Changes | [73] |

| MWCNT/elastomer | Mould casting | 5 × 5 | 14–36 | Changes | At work |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Shchegolkov, A.V.; Shchegolkov, A.V.; Parfimovich, I.D.; Kaminskii, V.V.; Putyrskaya, M.Y. Functional Nanocomposites with a Positive Temperature Coefficient of Resistance Based on Carbon Nanotubes Synthesized by Laser Ablation. J. Compos. Sci. 2026, 10, 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs10010019

Shchegolkov AV, Shchegolkov AV, Parfimovich ID, Kaminskii VV, Putyrskaya MY. Functional Nanocomposites with a Positive Temperature Coefficient of Resistance Based on Carbon Nanotubes Synthesized by Laser Ablation. Journal of Composites Science. 2026; 10(1):19. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs10010019

Chicago/Turabian StyleShchegolkov, Alexandr V., Aleksei V. Shchegolkov, Ivan D. Parfimovich, Vladimir V. Kaminskii, and Mariya Y. Putyrskaya. 2026. "Functional Nanocomposites with a Positive Temperature Coefficient of Resistance Based on Carbon Nanotubes Synthesized by Laser Ablation" Journal of Composites Science 10, no. 1: 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs10010019

APA StyleShchegolkov, A. V., Shchegolkov, A. V., Parfimovich, I. D., Kaminskii, V. V., & Putyrskaya, M. Y. (2026). Functional Nanocomposites with a Positive Temperature Coefficient of Resistance Based on Carbon Nanotubes Synthesized by Laser Ablation. Journal of Composites Science, 10(1), 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs10010019