Thermal Modeling of Temperature Distribution in Metal Additive Manufacturing Considering Effects of Build Layers, Latent Heat, and Temperature-Sensitivity of Material Properties

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Approach and Methodology

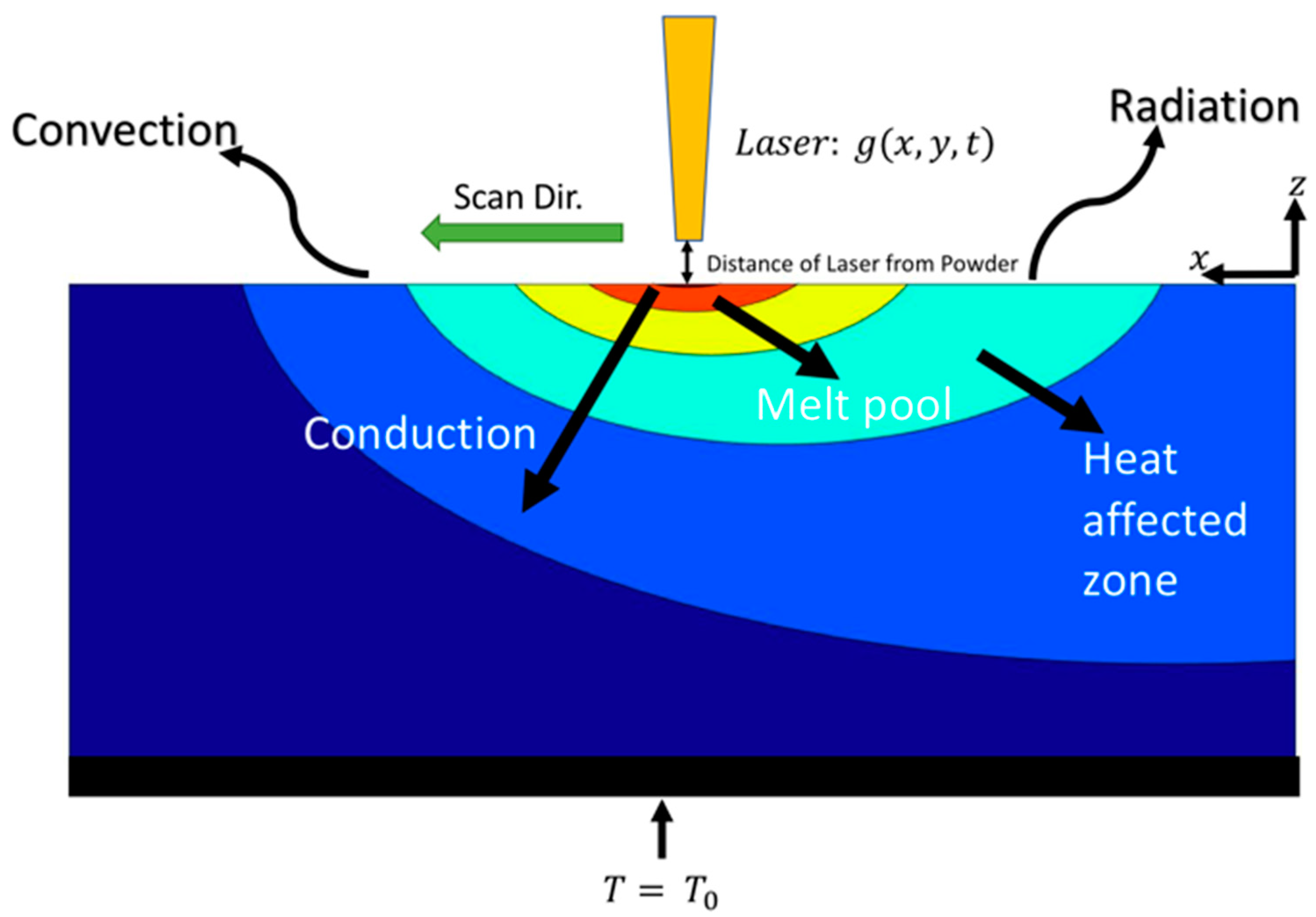

2.1. Analytical Modeling

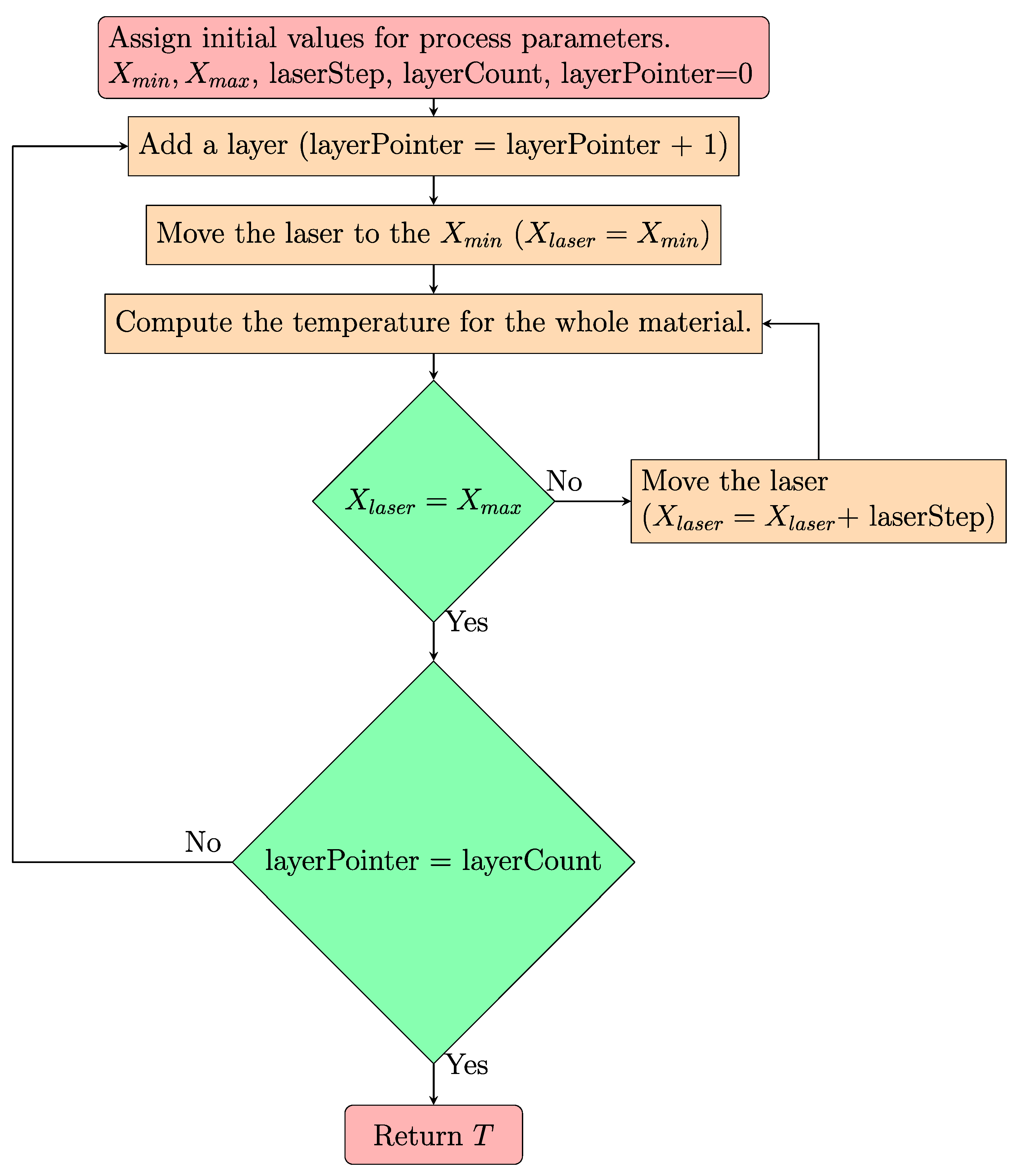

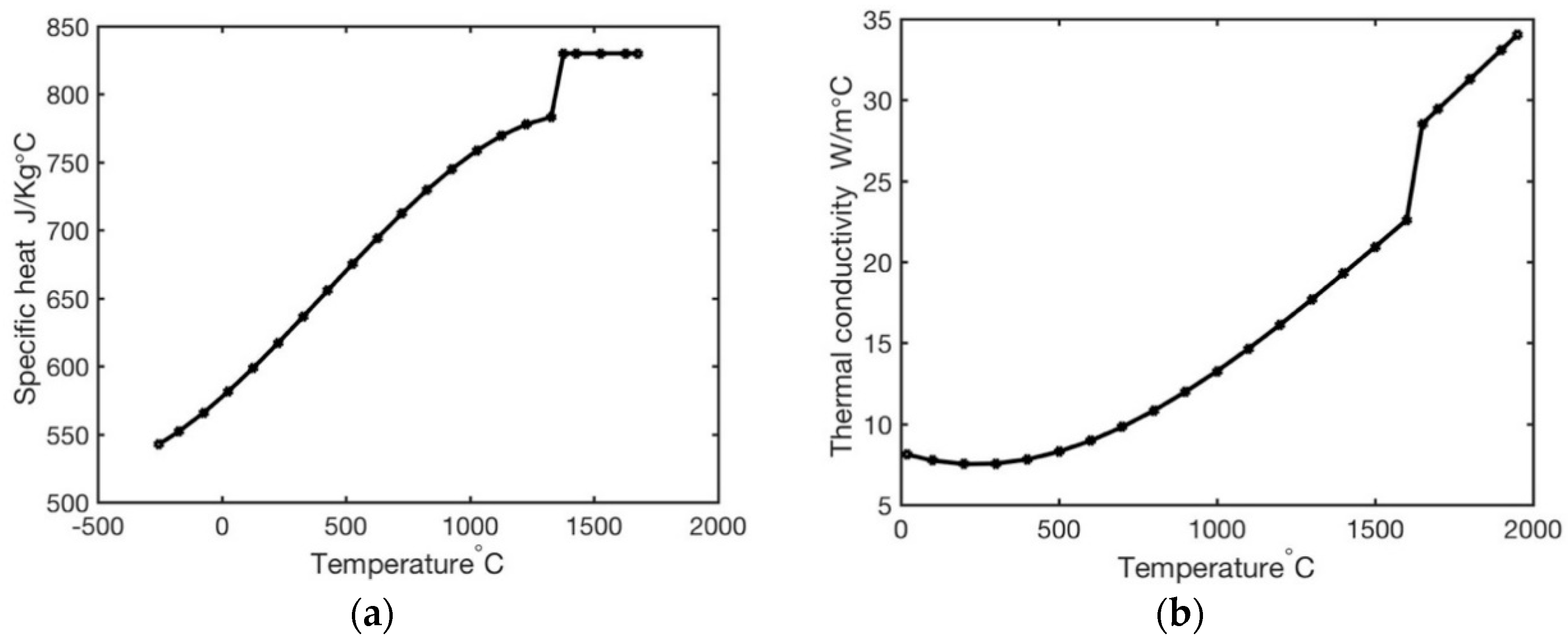

2.2. Numerical Modeling

3. Modeling Results and Experimental Comparison

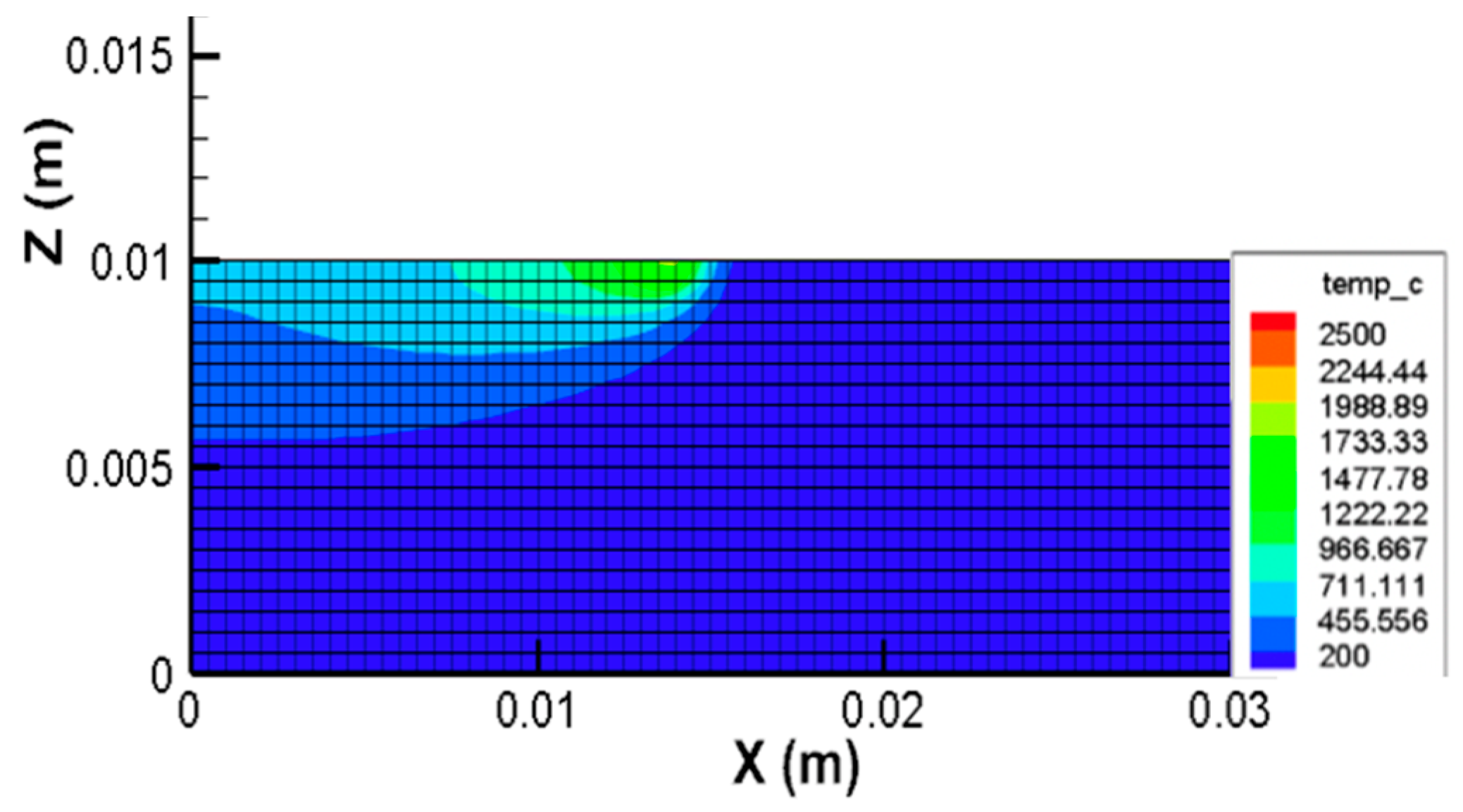

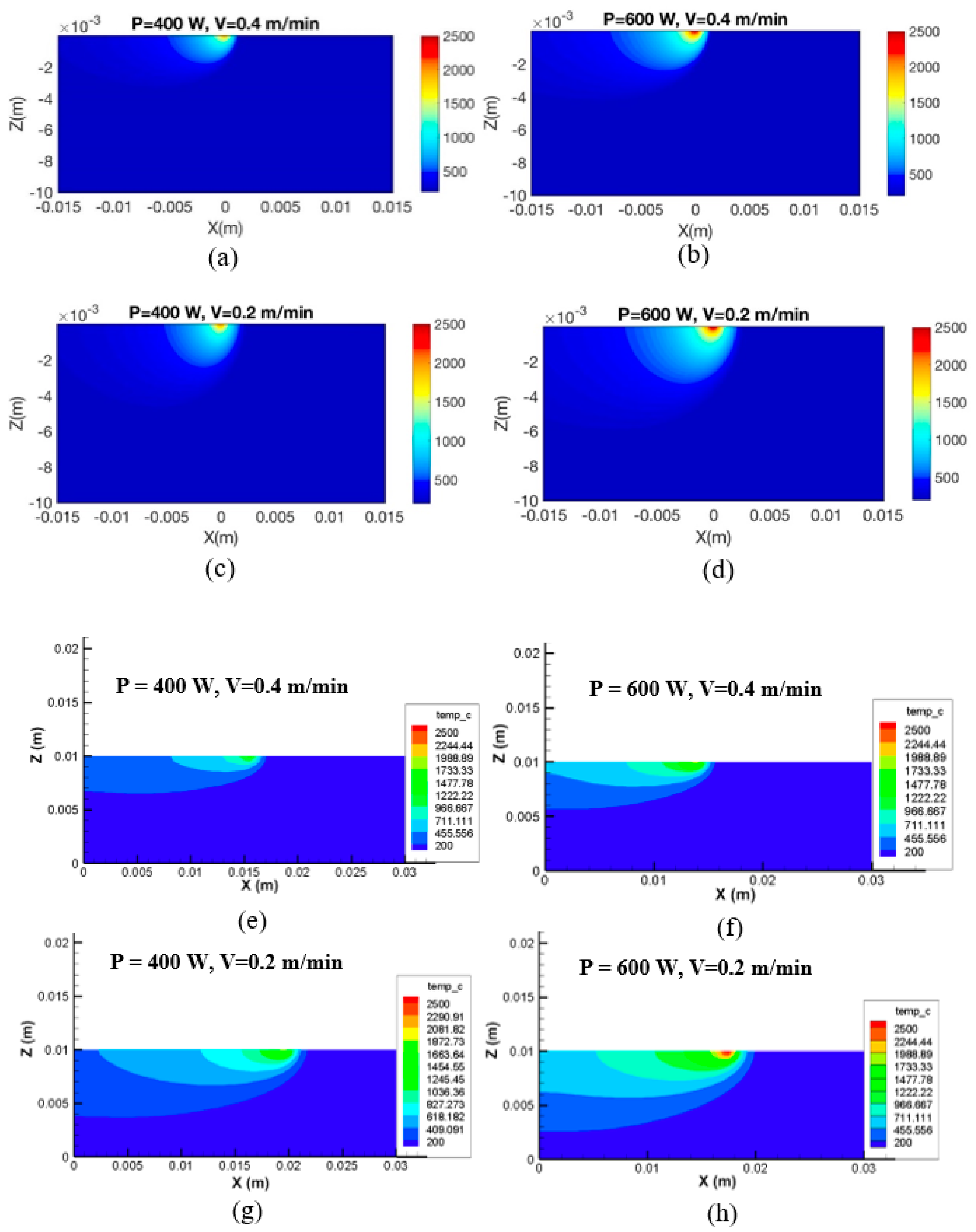

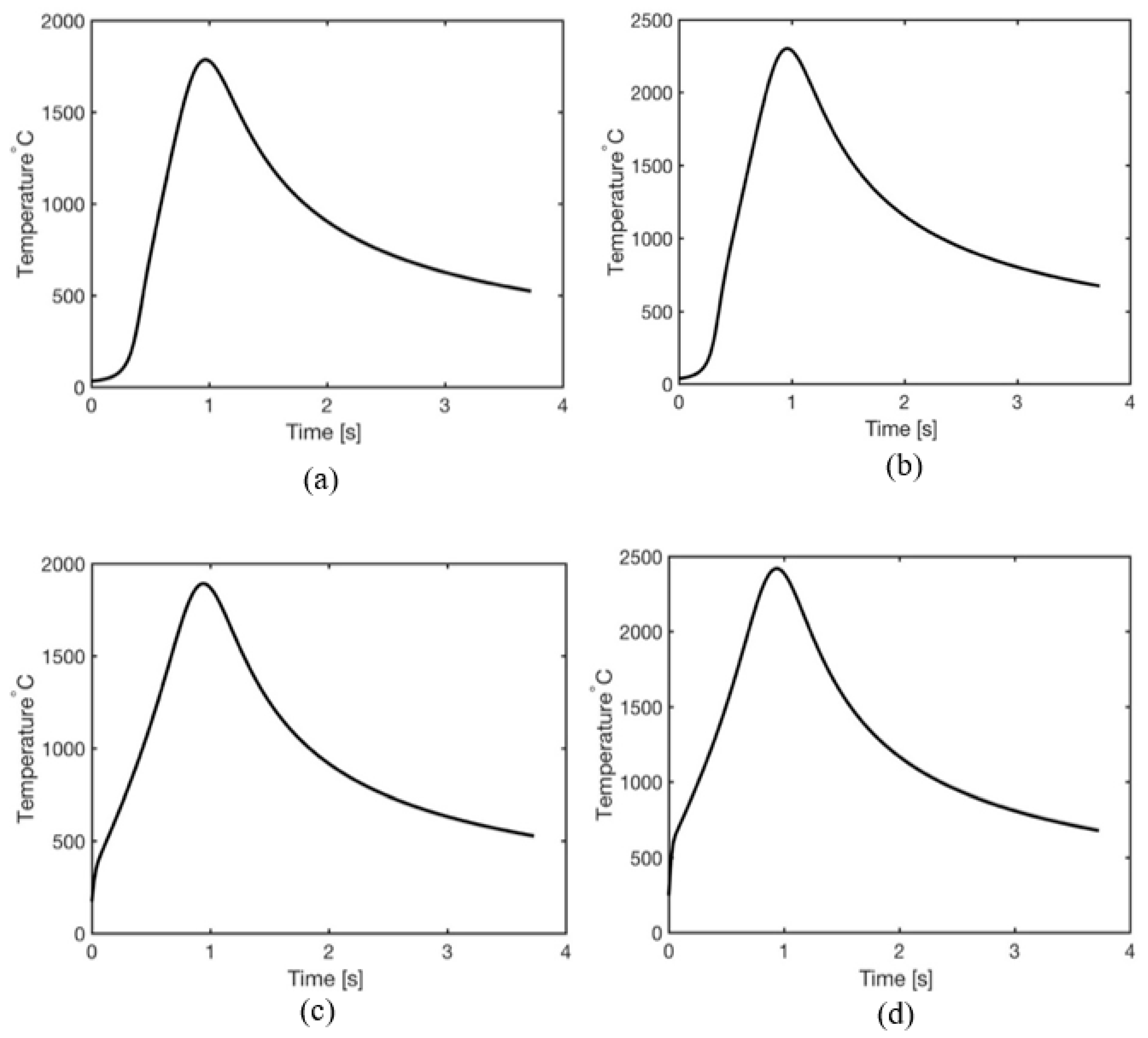

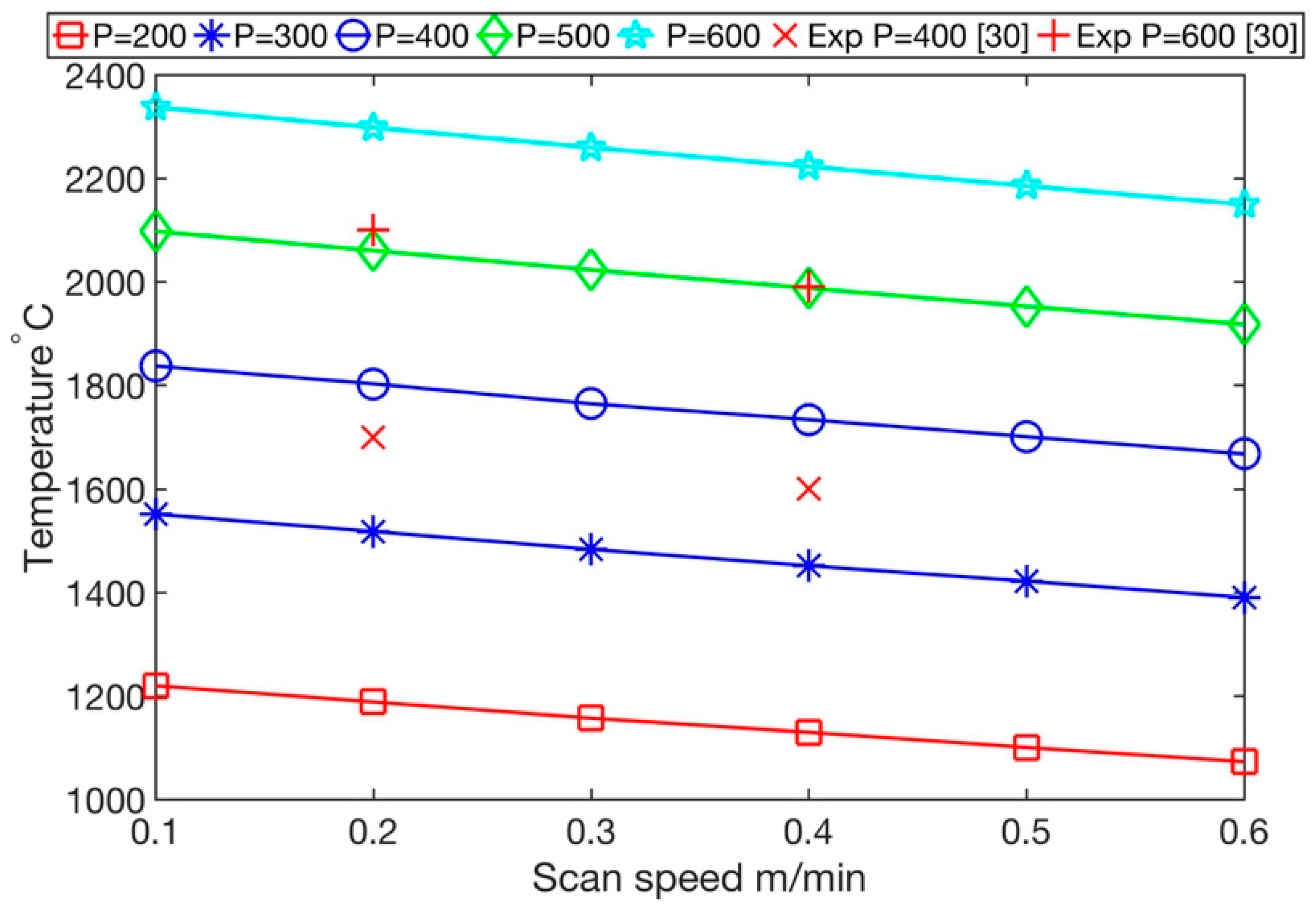

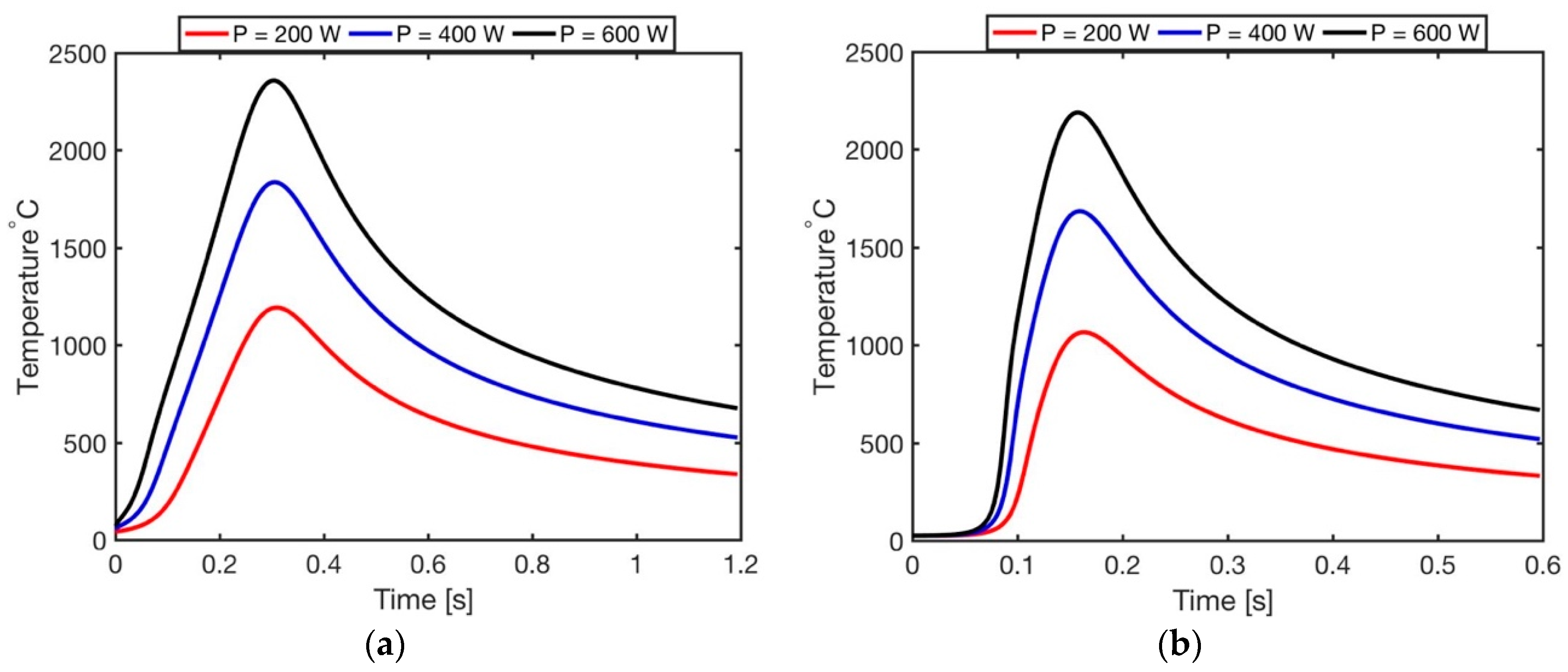

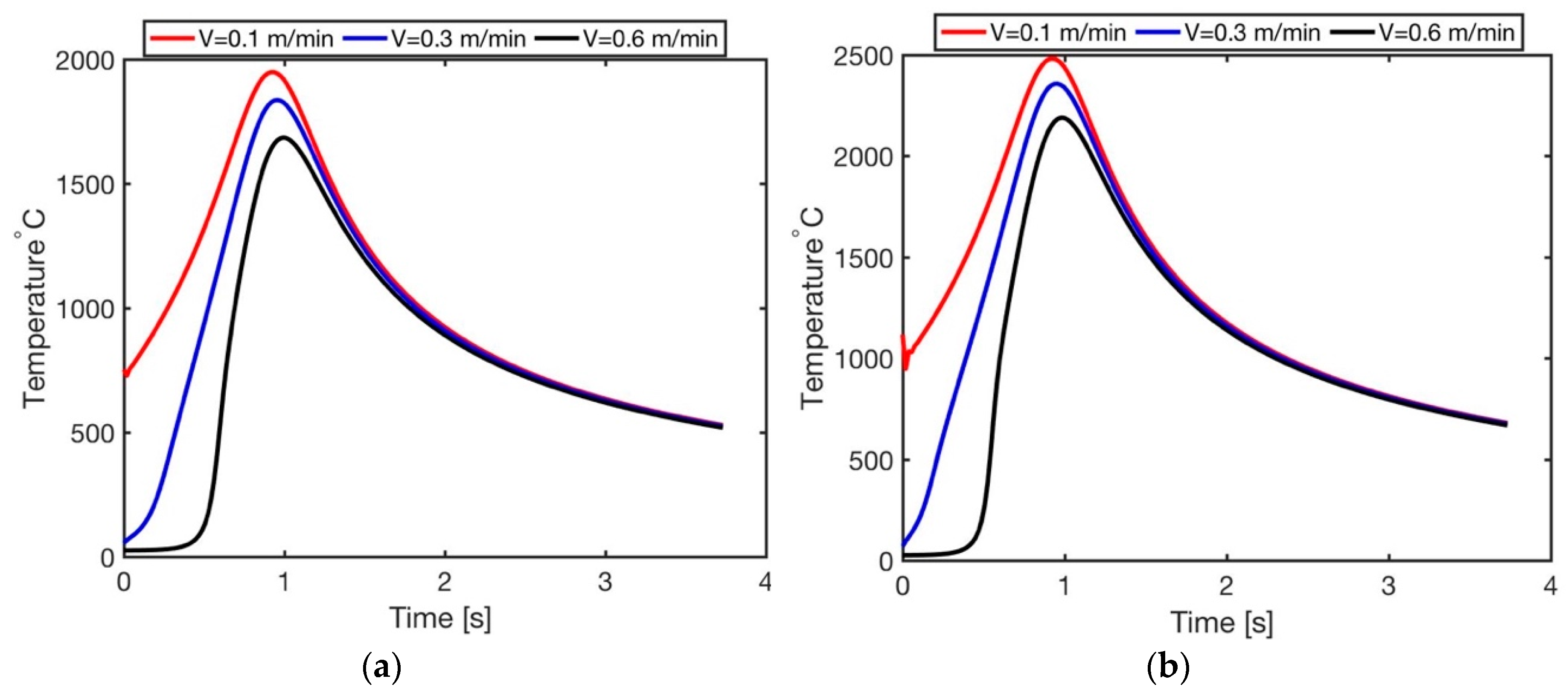

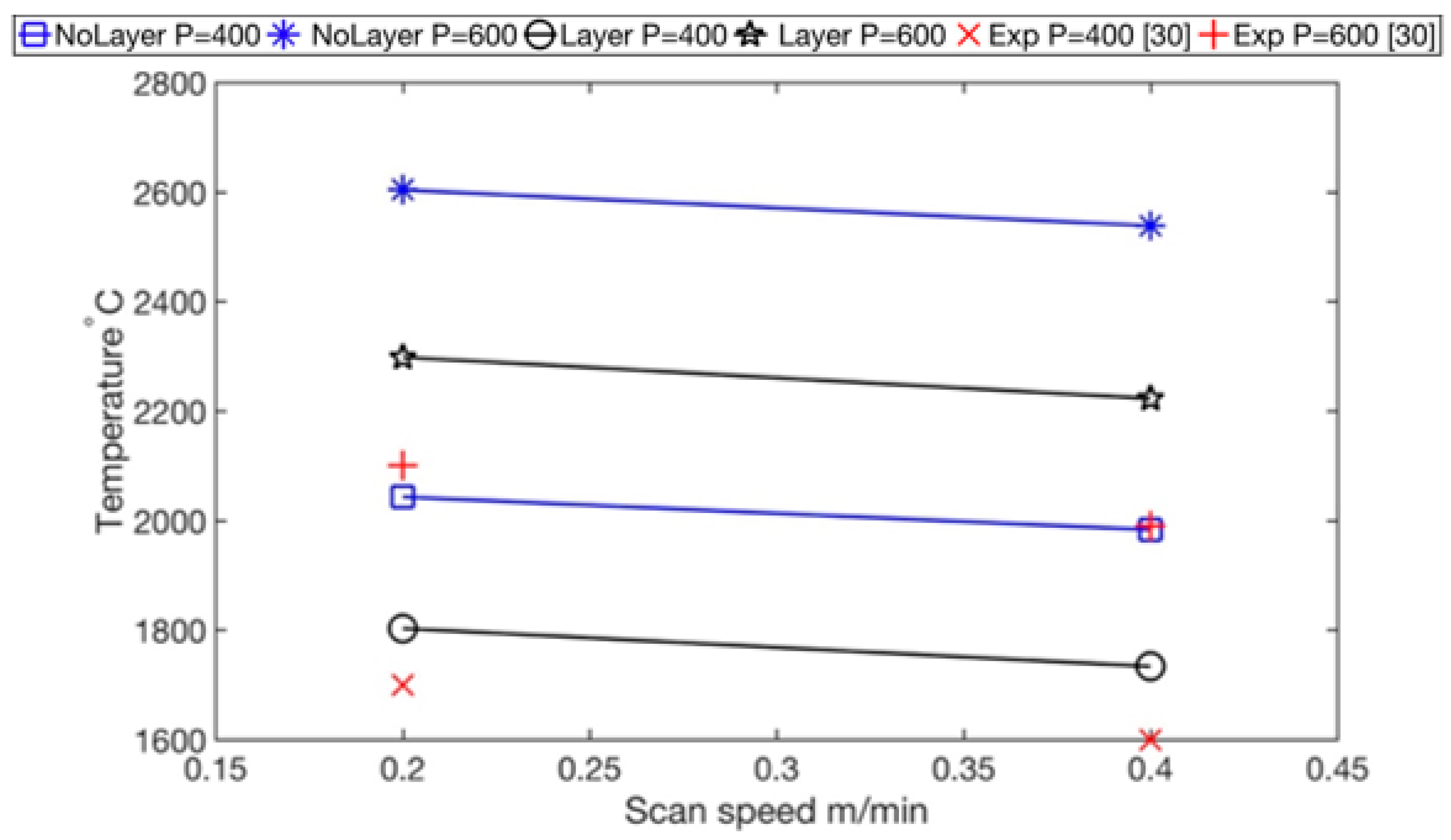

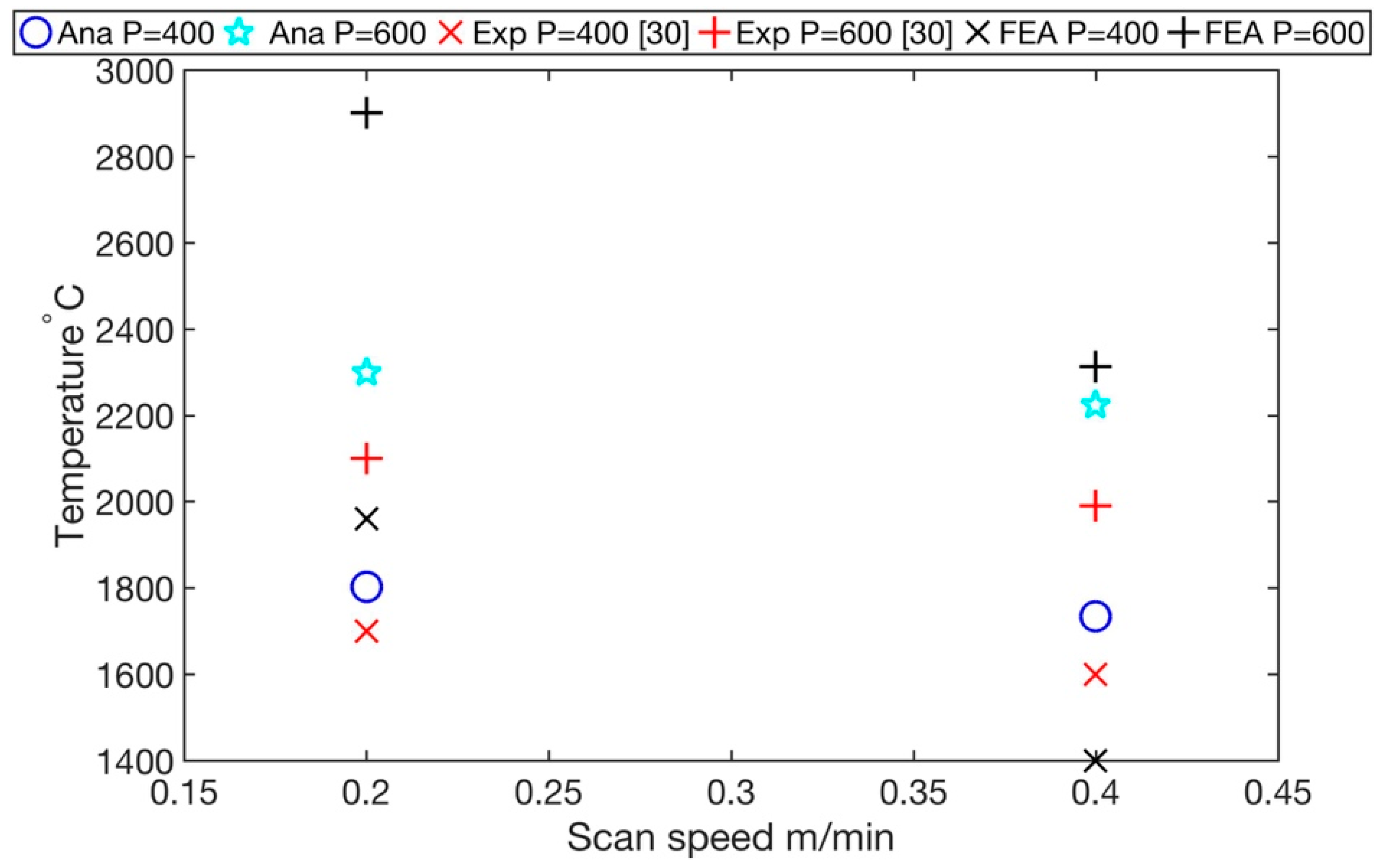

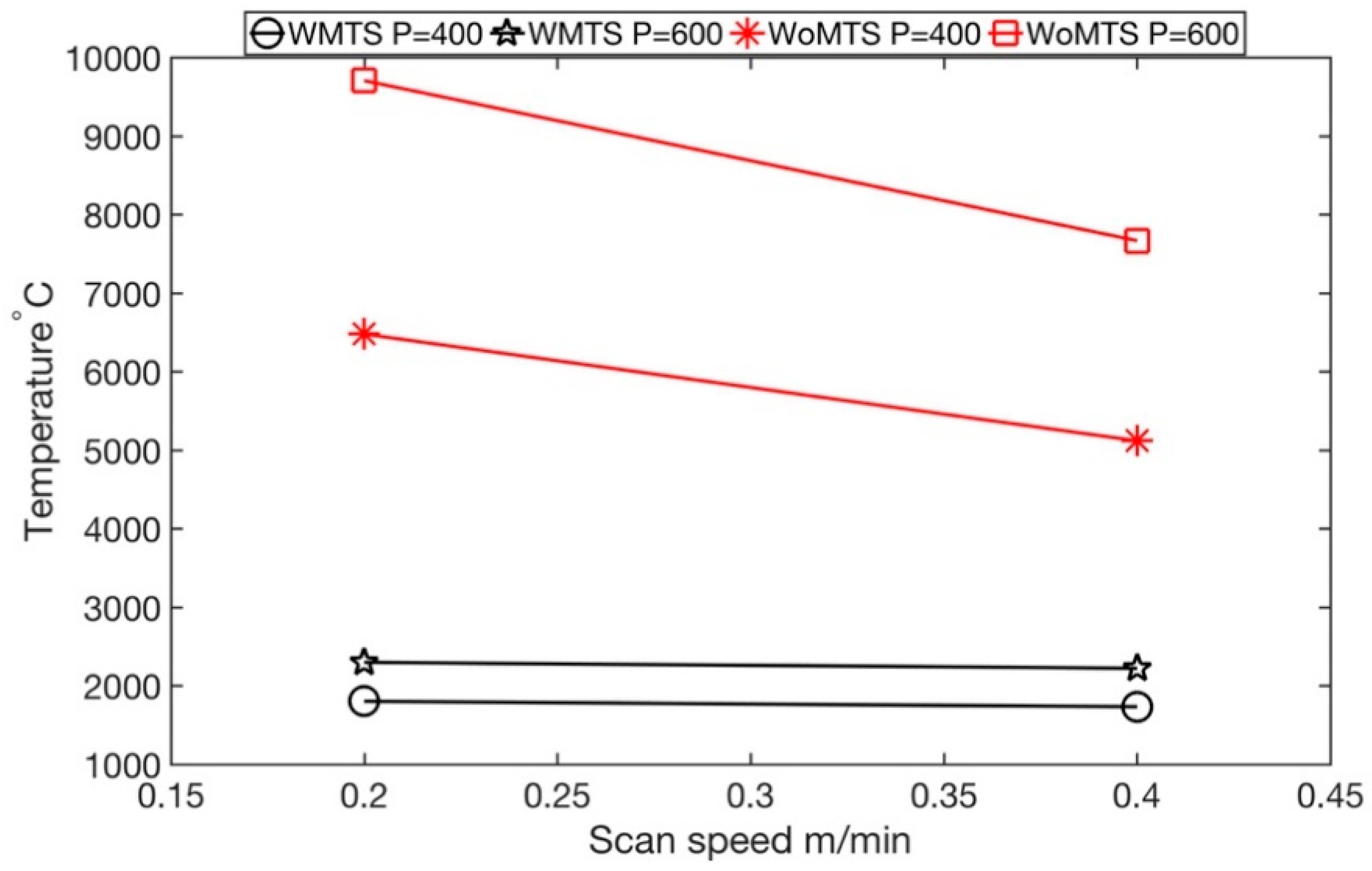

3.1. Temperature Profile, Maximum Temperature, and Surface Temperature

3.2. Experimental Validation Based on Melt Pool Geometry Measurement

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mellor, S.; Hao, L.; Zhang, D. Additive manufacturing: A framework for implementation. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2014, 149, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bikas, H.; Stavropoulos, P.; Chryssolouris, G. Additive manufacturing methods and modelling approaches: A critical review. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2016, 83, 389–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, B.N.; Strong, R.; Gold, S.A. A review of melt extrusion additive manufacturing processes: I. Process design and modeling. Rapid Prototyp. J. 2014, 20, 192–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruth, J.-P.; Levy, G.; Klocke, F.; Childs, T. Consolidation phenomena in laser and powder-bed based layered manufacturing. CIRP Ann. 2007, 56, 730–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woesz, A. Rapid prototyping to produce porous scaffolds with controlled architecture for possible use in bone tissue engineering. In Virtual Prototyping & Bio Manufacturing in Medical Applications; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 171–206. [Google Scholar]

- Frazier, W.E. Metal additive manufacturing: A review. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2014, 23, 1917–1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasinonta, A.; Beuth, J.L.; Griffith, M.L. Process maps for controlling residual stress and melt pool size in laser-based SFF processes. In Proceedings of the Solid Freeform Fabrication Symposium, Austin, TX, USA, 7–9 August 2000; p. 206. [Google Scholar]

- Pang, T.H.; Guertin, M.D.; Nguyen, H.D. Accuracy of Stereolithography Parts: Mechanism and Modes of Distortion for a “Letter H” Diagnostic Part. In Proceedings of the Solid Free Form Fabrication Symposium, Austin, TX, USA, 7–9 August 1995; pp. 170–180. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Chou, Y.K. A parametric study of part distortions in FDM using 3D FEA. In Proceedings of the 17th Solid Freeform Fabrication Symposium, Austin, TX, USA, 14–16 August 2006; pp. 410–420. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, I.A.; Wang, C.; Esterlein, R.; Stanford, M.; Mynors, D. A three-dimensional finite element analysis of the temperature field during laser melting of metal powders in additive layer manufacturing. Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf. 2009, 49, 916–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaleris, P. Modeling metal deposition in heat transfer analyses of additive manufacturing processes. Finite Elem. Anal. Des. 2014, 86, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krol, T.; Seidel, C.; Zaeh, M. Prioritization of process parameters for an efficient optimisation of additive manufacturing by means of a finite element method. Procedia CIRP 2013, 12, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, D.; Kovacevic, R. Sensing, modeling and control for laser-based additive manufacturing. Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf. 2003, 43, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contuzzi, N.; Campanelli, S.; Ludovico, A. 3 D Finite Element Analysis in the Selective Laser Melting Process. Int. J. Simul. Model. 2011, 10, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Colegrove, P.; Mehnen, J.; Ganguly, S.; Almeida, P.S.; Wang, F.; Williams, S. Thermo-mechanical analysis of Wire and Arc Additive Layer Manufacturing process on large multi-layer parts. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2011, 50, 3315–3322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denlinger, E.R.; Heigel, J.C.; Michaleris, P.; Palmer, T. Effect of inter-layer dwell time on distortion and residual stress in additive manufacturing of titanium and nickel alloys. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2015, 215, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarangsi, P.; Beuth, J.L. Localized preheating approaches for reducing residual stress in additive manufacturing. In Proceedings of the SFF Symposium, Austin, TX, USA, 14–16 August 2006; pp. 709–720. [Google Scholar]

- De La Batut, B.; Fergani, O.; Brotan, V.; Bambach, M.; El Mansouri, M. Analytical and Numerical Temperature Prediction in Direct Metal Deposition of Ti6Al4V. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2017, 1, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, C.Y.; Tan, H.K.; Du, Z.; Chua, C.K.; Dong, Z. Selective laser melting of nickel powder. Rapid Prototyp. J. 2017, 23, 750–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galarraga, H.; Warren, R.J.; Lados, D.A.; Dehoff, R.R.; Kirka, M.M.; Nandwana, P. Effects of heat treatments on microstructure and properties of Ti-6Al-4V ELI alloy fabricated by electron beam melting (EBM). Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2017, 685, 417–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, S.; Kampe, S. Microstructural evolution in laser-deposited multilayer Ti-6Al-4V builds: Part II. Thermal modeling. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2004, 35, 1869–1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoadley, A.; Rappaz, M. A thermal model of laser cladding by powder injection. Metall. Trans. B 1992, 23, 631–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyserkani, E.; Khajepour, A.; Corbin, S. 3-D finite element modeling of laser cladding by powder injection: Effects of laser pulse shaping on the process. Opt. Lasers Eng. 2004, 41, 849–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Ayalew, B. Control-oriented MIMO modeling of laser-aided powder deposition processes. In Proceedings of the American Control Conference (ACC), Chicago, IL, USA, 1–3 July 2015; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 3637–3642. [Google Scholar]

- Hitzler, L.; Hirsch, J.; Heine, B.; Merkel, M.; Hall, W.; Öchsner, A. On the anisotropic mechanical properties of selective laser-melted stainless steel. Materials 2017, 10, 1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hitzler, L.; Merkel, M.; Hall, W.; Öchsner, A. A Review of Metal Fabricated with Laser-and Powder-Bed Based Additive Manufacturing Techniques: Process, Nomenclature, Materials, Achievable Properties, and its Utilization in the Medical Sector. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2018, 20, 1700658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, R.; Masood, S.; Ruan, D.; Palanisamy, S.; Rashid, R.R.; Brandt, M. Effect of scan strategy on density and metallurgical properties of 17-4PH parts printed by Selective Laser Melting (SLM). J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2017, 249, 502–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Jiang, X.; Zhu, Y.; Zhu, X.; Sun, J.; Yan, B. An approach to predict the residual stress and distortion during the selective laser melting of AlSi10Mg parts. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2018, 97, 3535–3546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiva, S.; Palani, I.; Paul, C.; Singh, B. Laser annealing of laser additive–manufactured Ni-Ti structures: An experimental–numerical investigation. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part B J. Eng. Manuf. 2018, 232, 1054–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirkoohi, E.; Bocchini, P.; Liang, S.Y. An Analytical Modeling for Designing the Process Parameters for Temperature Specifications in Machining. Preprints 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirkoohi, E.; Bocchini, P.; Liang, S.Y. An analytical modeling for process parameter planning in the machining of Ti-6Al-4V for force specifications using an inverse analysis. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2018, 98, 2347–2355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carslaw, H.; Jaeger, J. Conduction of Heat in Solids: Oxford Science Publications; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Mirkoohi, E.; Malhotra, R. Effect of Particle Shape on Neck Growth and Shrinkage of Nanoparticles. In Proceedings of the ASME 2017 12th International Manufacturing Science and Engineering Conference Collocated with the JSME/ASME 2017 6th International Conference on Materials and Processing, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 4–8 June 2017; American Society of Mechanical Engineers: New York, NY, USA, 2017; p. V002T001A026. [Google Scholar]

- Mills, K.C. Recommended Values of Thermophysical Properties for Selected Commercial Alloys; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Pouzet, S.B. Fabrication Additive de Composites à Matrice titane par Fusion Laser de Poudre Projetée; ENSAM: Paris, France, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Pinkerton, A.J.; Li, L. Modelling the geometry of a moving laser melt pool and deposition track via energy and mass balances. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2004, 37, 1885–1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, B.; Chou, K. Melt pool geometry simulations for powder-based electron beam additive manufacturing. In Proceedings of the 24th Annual International Solid Freeform Fabrication Symposium—An Additive Manufacturing Conference, Austin, TX, USA, 12–14 August 2013; pp. 644–654. [Google Scholar]

- Peyre, P.; Aubry, P.; Fabbro, R.; Neveu, R.; Longuet, A. Analytical and numerical modelling of the direct metal deposition laser process. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2008, 41, 025403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Properties | Ti-6Al-4V |

|---|---|

| Liquidus temperature (K) | 1928 |

| Solidus temperature (K) | 1878 |

| Thermal conductivity (W/m K) | |

| Specific heat (J/Kg K) | |

| Density (Kg/m3) | 4420 |

| Viscosity (Kg/m s) | 4 × 10−3 |

| Latent heat (J/Kg) | 2 × 105 |

| Name | Value |

|---|---|

| Thermal radiation coefficient (W/m2·°C4) | 5.67 × 10−8 |

| Heat transfer coefficient (W/m2·°C) | 24 |

| Material emissivity | 0.9 |

| D | [0.2–0.4] |

| Gaussian shape factor | 2 |

| Laser spot radius (mm) | 0.7 |

| Ambient temperature | 25 |

| Laser Power (W) | 400 | 400 | 600 | 600 |

| Scanning Speed (m/min) | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.4 |

| Max Temperature w/o Layer | 2043.7 | 1998.1 | 2603.7 | 2538.1 |

| Max Temperature with Layer | 1802.8 | 1733.6 | 2298.1 | 2222.7 |

| Experimental Values | 1730 | 1605 | 2100 | 1970 |

| P (W) | V (mm/s) | Melt Pool Length (mm) Model | Melt Pool Length (mm) Exp/sim | Melt Pool Depth (mm) Model | Melt Pool Depth (mm) Exp/sim | Error in Length | Error in Depth |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

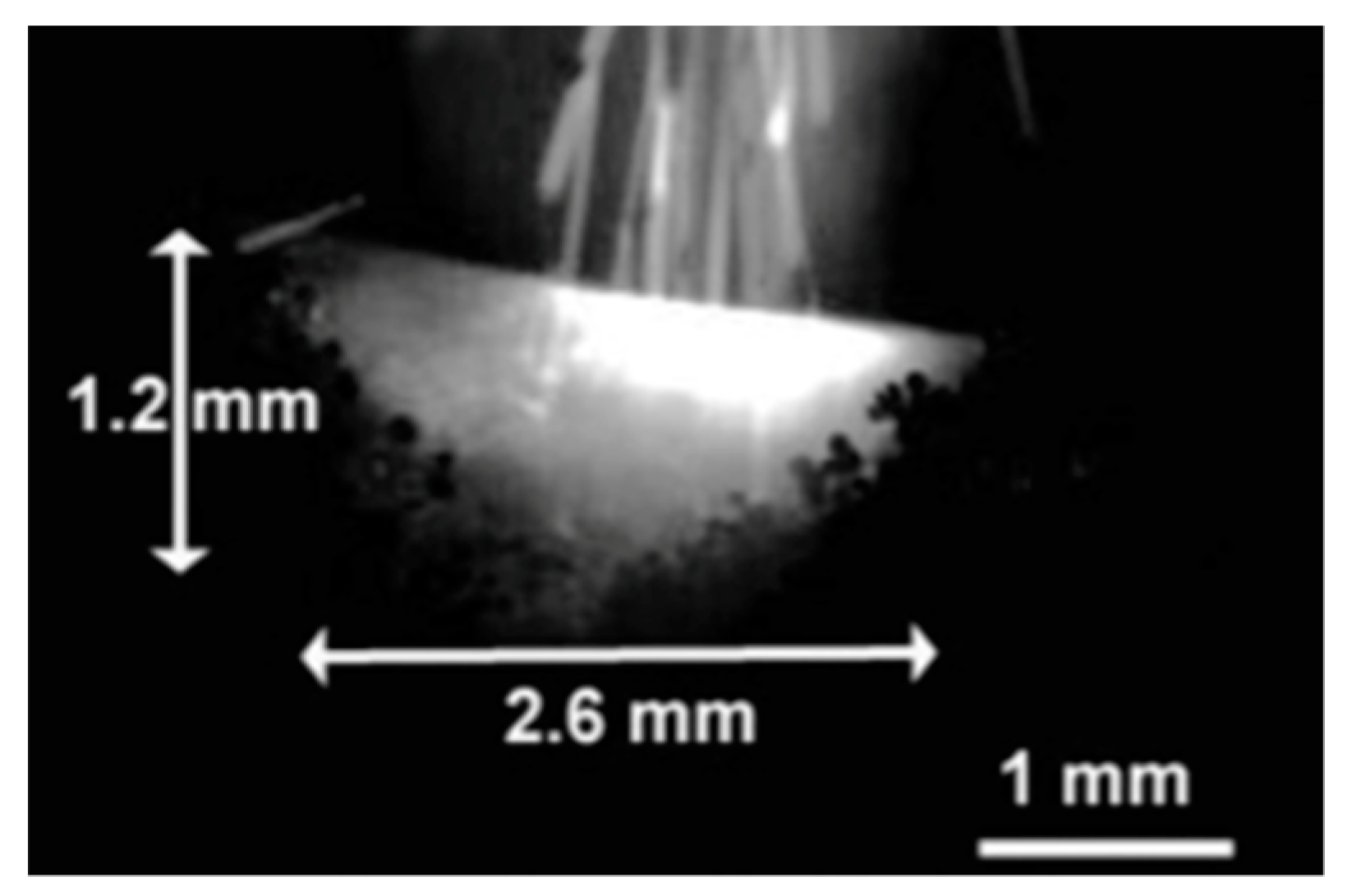

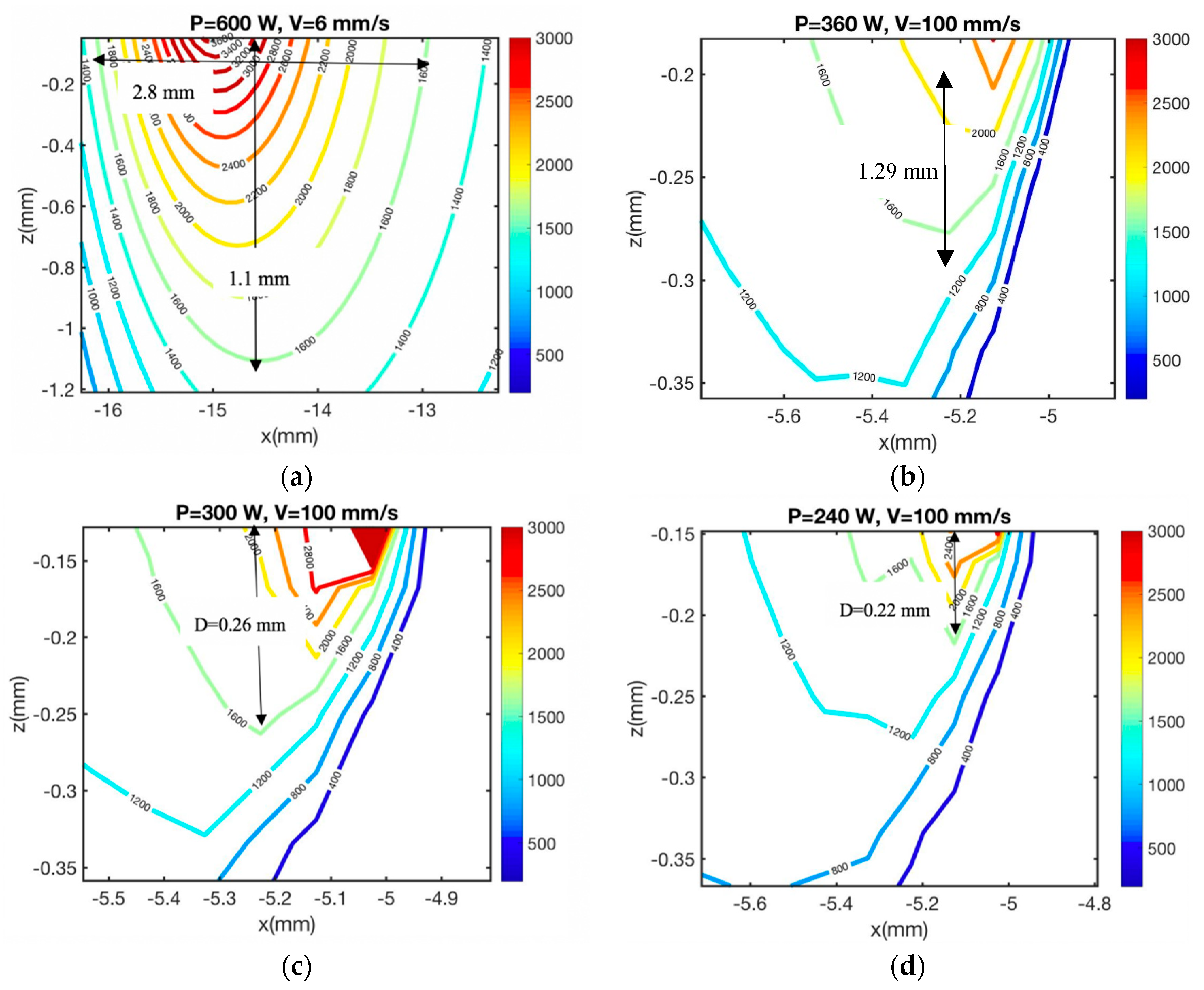

| 600 [38] | 6 | 2.80 | 2.60 | 1.10 | 1.20 | 7.60% | 2.00% |

| 360 [37] | 100 | - | - | 0.29 | 0.30 | - | 3.40% |

| 300 [37] | 100 | - | - | 0.26 | 0.27 | - | 3.70% |

| 240 [37] | 100 | - | - | 0.22 | 0.20 | - | 1.00% |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mirkoohi, E.; Ning, J.; Bocchini, P.; Fergani, O.; Chiang, K.-N.; Liang, S.Y. Thermal Modeling of Temperature Distribution in Metal Additive Manufacturing Considering Effects of Build Layers, Latent Heat, and Temperature-Sensitivity of Material Properties. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2018, 2, 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmmp2030063

Mirkoohi E, Ning J, Bocchini P, Fergani O, Chiang K-N, Liang SY. Thermal Modeling of Temperature Distribution in Metal Additive Manufacturing Considering Effects of Build Layers, Latent Heat, and Temperature-Sensitivity of Material Properties. Journal of Manufacturing and Materials Processing. 2018; 2(3):63. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmmp2030063

Chicago/Turabian StyleMirkoohi, Elham, Jinqiang Ning, Peter Bocchini, Omar Fergani, Kuo-Ning Chiang, and Steven Y. Liang. 2018. "Thermal Modeling of Temperature Distribution in Metal Additive Manufacturing Considering Effects of Build Layers, Latent Heat, and Temperature-Sensitivity of Material Properties" Journal of Manufacturing and Materials Processing 2, no. 3: 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmmp2030063

APA StyleMirkoohi, E., Ning, J., Bocchini, P., Fergani, O., Chiang, K.-N., & Liang, S. Y. (2018). Thermal Modeling of Temperature Distribution in Metal Additive Manufacturing Considering Effects of Build Layers, Latent Heat, and Temperature-Sensitivity of Material Properties. Journal of Manufacturing and Materials Processing, 2(3), 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmmp2030063