Enhanced UAV-Dot for UAV Crowd Localization: Adaptive Gaussian Heat Map and Attention Mechanism to Address Scale/Low-Light Challenges

Highlights

- The proposed scale-adaptive Gaussian kernel dynamically adjusts heatmap supervision, effectively resolving target merging and fragmentation caused by UAV altitude variations, contributing to a 1.62% gain in L-mAP.

- The integrated CBAM attention module enhances feature extraction under low-light conditions via a “channel–spatial” focusing mechanism, improving feature discriminability and yielding a 0.92% L-mAP increase.

- The enhanced UAV-Dot achieves a state-of-the-art 53.38% L-mAP on DroneCrowd with minimal overhead—parameters increase by only 0.36% (training) and 0.29% (testing), reconciling high accuracy with model efficiency for UAV deployment.

- The synergistic combination of adaptive heatmaps and attention mechanisms establishes a new architectural paradigm for addressing the coupled challenges of scale variation and low-light degradation in aerial crowd localization.

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Drastic image scale variations: changes in UAV flight altitude cause the size of human targets to vary significantly within and across images.

- Severe feature degradation in low light: under poor illumination conditions (e.g., at night or in heavily overcast scenes), the already weak features of small targets are easily submerged by complex background noise, drastically reducing localization accuracy.

- We propose a scale-aware Gaussian heatmap generation mechanism that dynamically adjusts kernel sizes based on a predicted scale factor, effectively resolving the target merging and fragmentation issues caused by altitude variations.

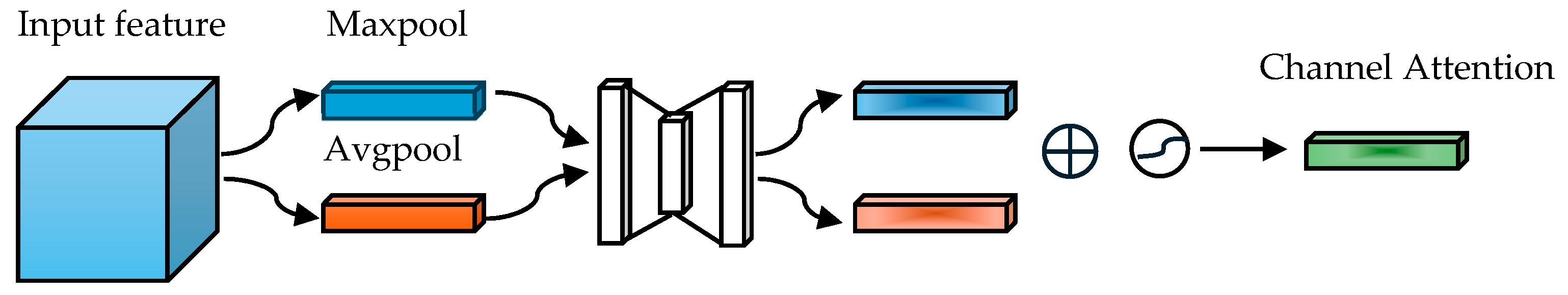

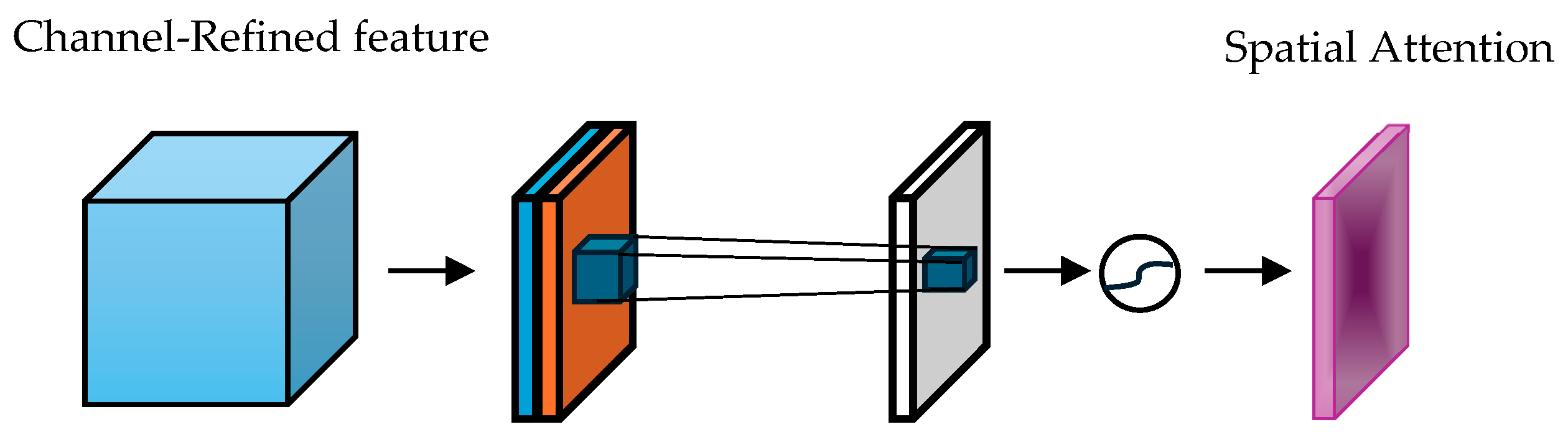

- We embed a convolutional block attention module (CBAM) [11] into the U-Net encoder, creating a “channel–spatial” focusing mechanism that enhances feature discriminability in low-light conditions.

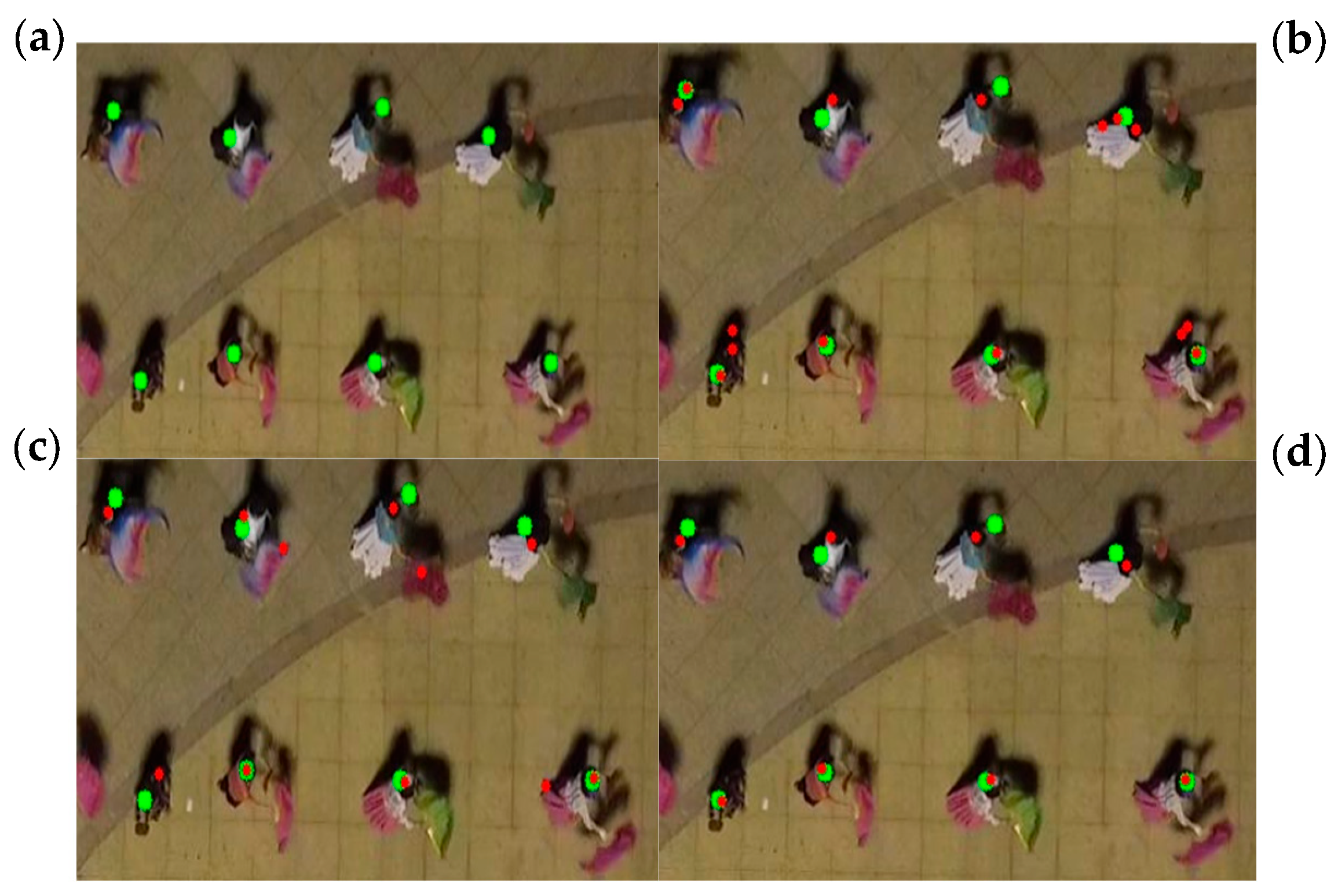

- We adopt an optimized post-processing strategy incorporating dynamic thresholding and DBSCAN clustering to correct residual misdetections, particularly for large-scale targets with complex poses.

2. Related Works

2.1. From Count to Point Regression

2.2. Heatmap Regression Paradigm

2.3. UAV-Specific Frameworks

3. Methods

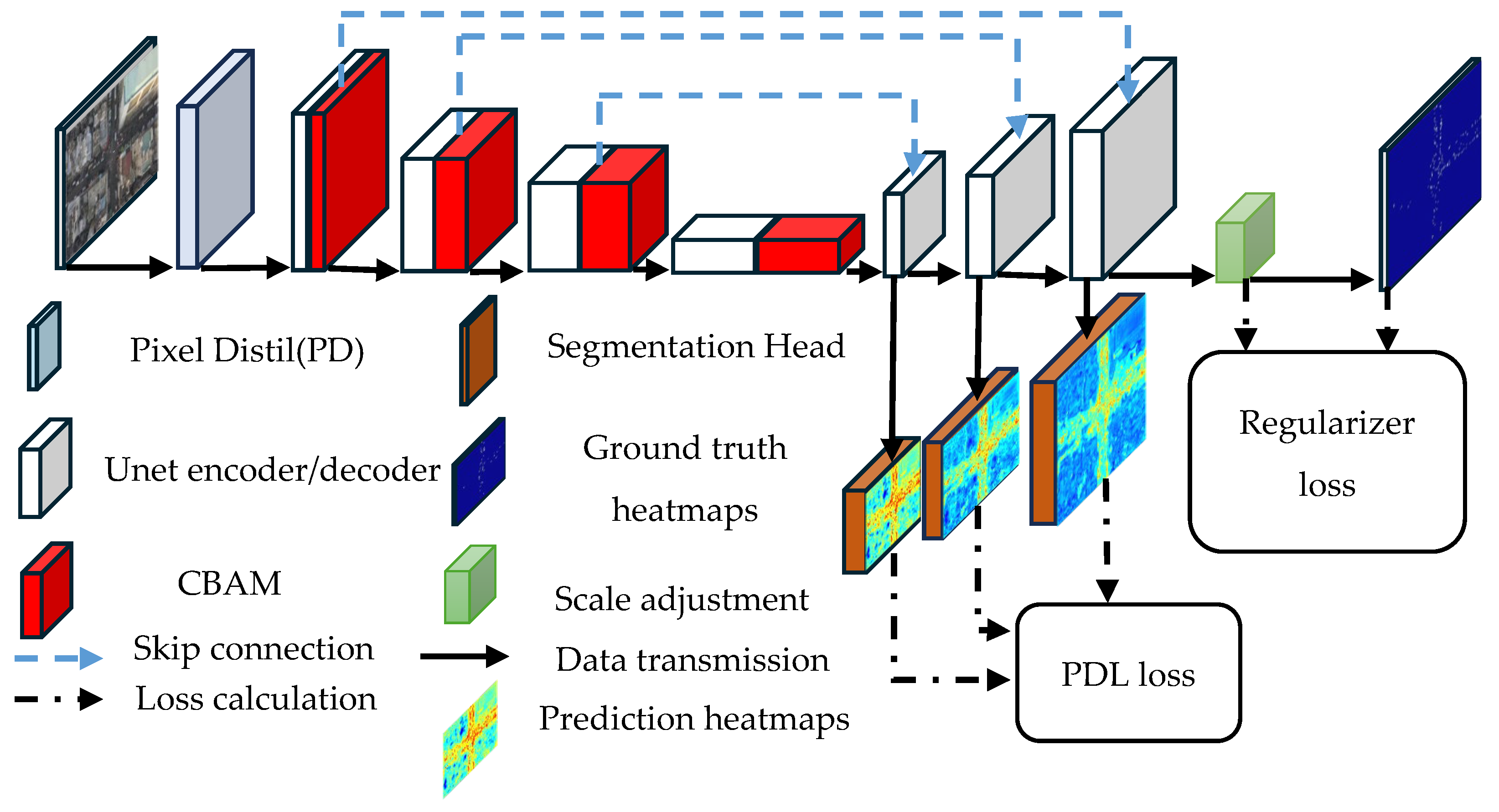

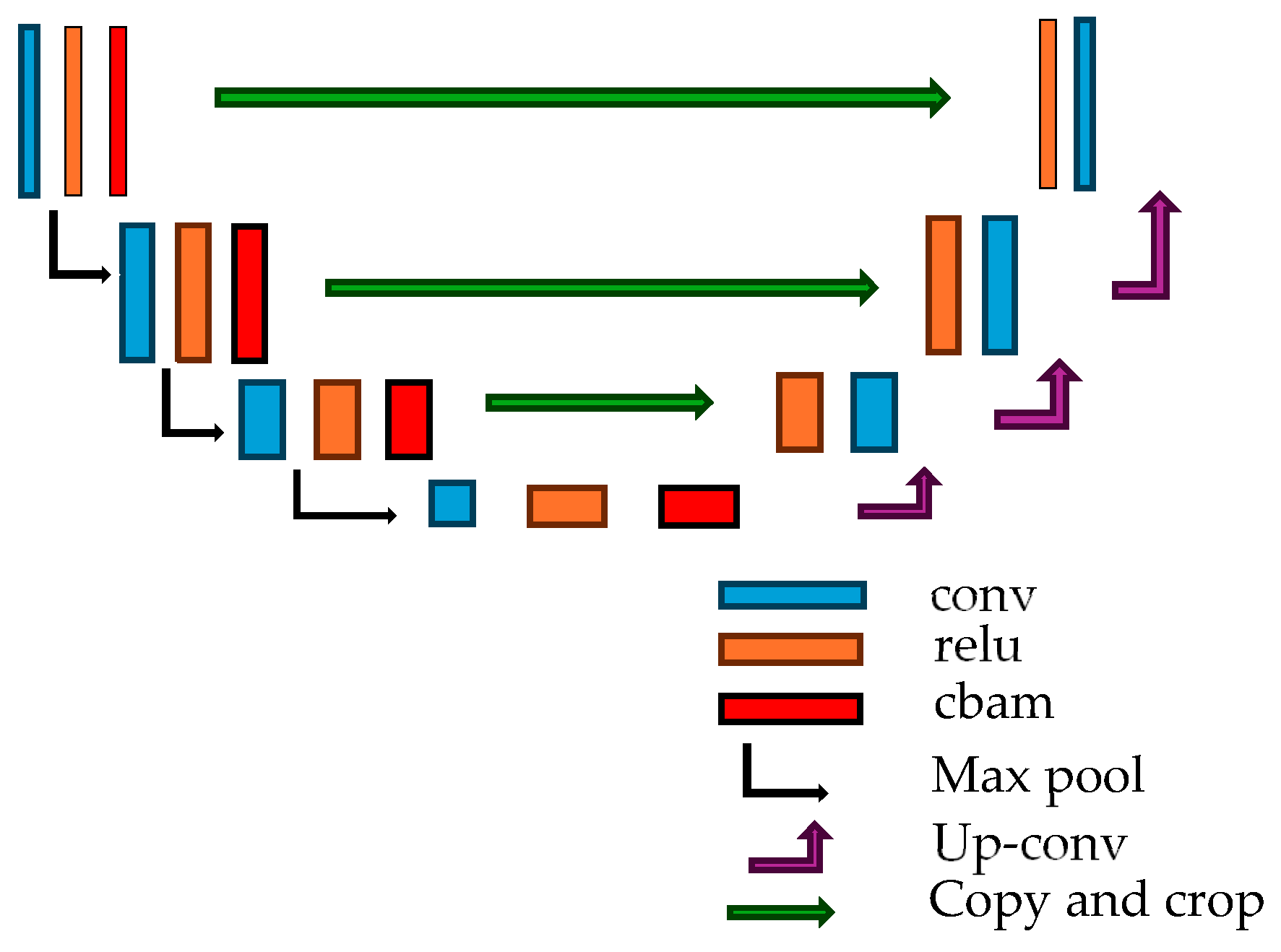

3.1. Baseline Framework: UAV-Dot

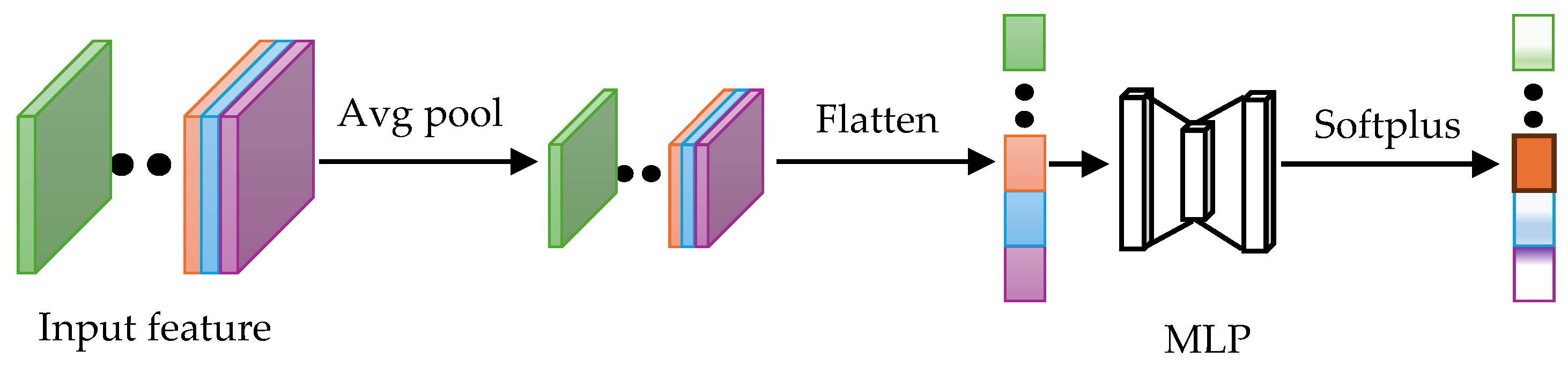

3.2. Scale-Adaptive Gaussian Kernel

3.3. Attention Enhancement for Low-Light Scenarios and Post-Processing Strategy

| Algorithm 1. Flowchart of the proposed post-processing algorithm. |

| local maxima detection strategy. |

| 1: Input: Predicted Gauss heat map |

| 2: Output: The coordinates of the persons |

| 3: function Extract _ Position |

| 4: normalized input = Normalize(input) |

| 5: pos_ind = maxpooling (normalized input, size = (3,3)) |

| 6: pos_ind = (pos_ind == normalized input) 7: heatmap matrix = pos_indnormalized input 8: if max (heatmap matrix) < Tf then 9: count = 0 10: coordinates = None 11: else 12: Ta = 75/255max (heatmap matrix) 13: heatmap matrix [heatmap matrix < Ta] = 0 14: heatmap matrix [heatmap matrix > 0] = 1 15: point = position (heatmap matrix = 1) 16: end if 17: if mean (normalized input) > Tb then 18: point = DBSCAN (point) 19: else 20: point = point 21: end if 22: return point 23: end Function |

4. Experiments and Results

4.1. Dataset and Metrics

4.1.1. Dataset

4.1.2. Metrics

4.2. Implementation Details

4.3. Experiments

4.3.1. Comparative Experiment

4.3.2. Ablation Experiments, Parameter Analysis, and FPS Measurement

4.3.3. Robustness Testing Under Different Lighting Conditions and CBAM Position Analysis

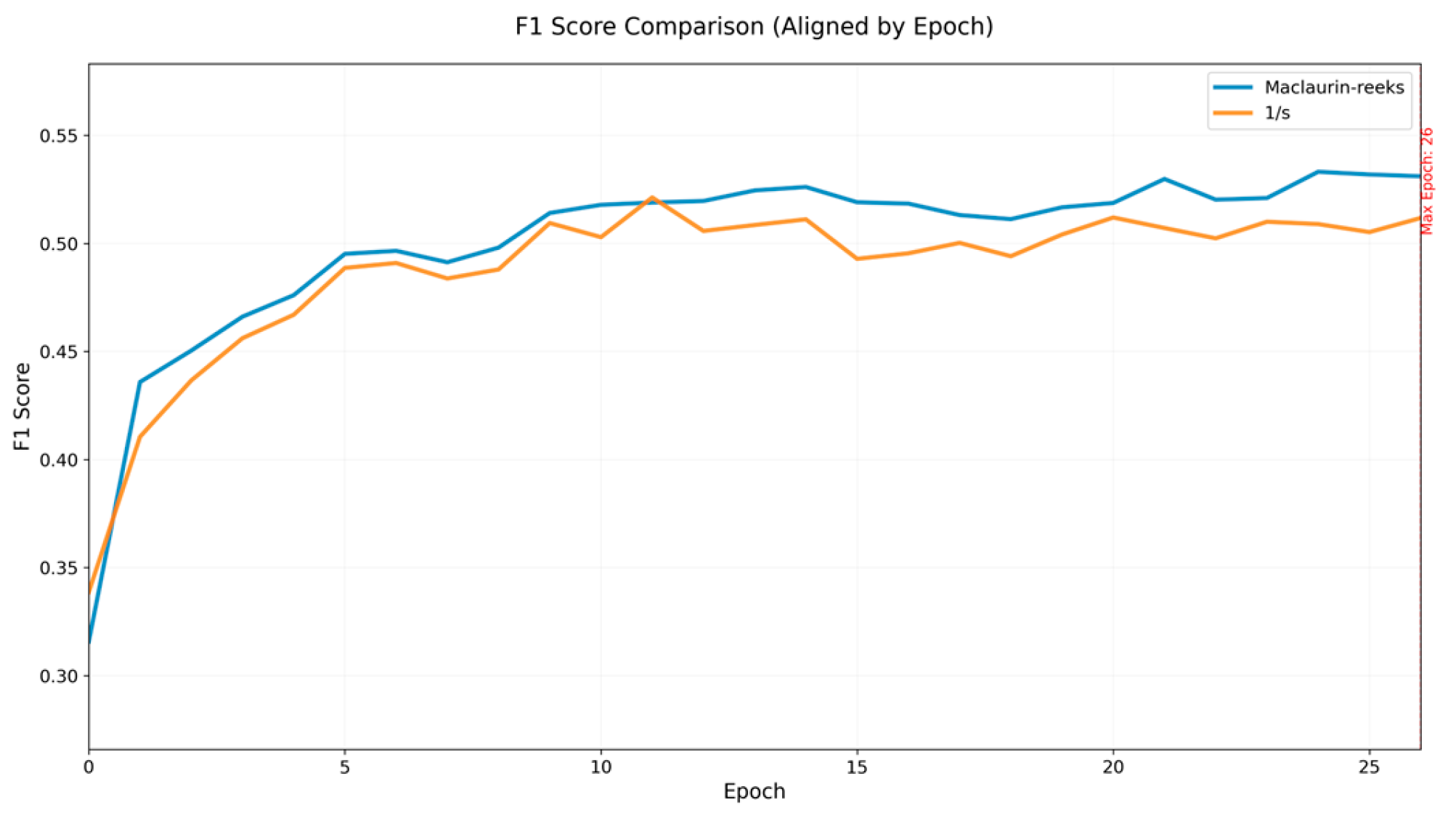

4.3.4. Stability Analysis of Equations (5) and (6) and Analysis of the λ Parameter in Equation (10)

4.3.5. Post-Processing Threshold Optimization Analysis

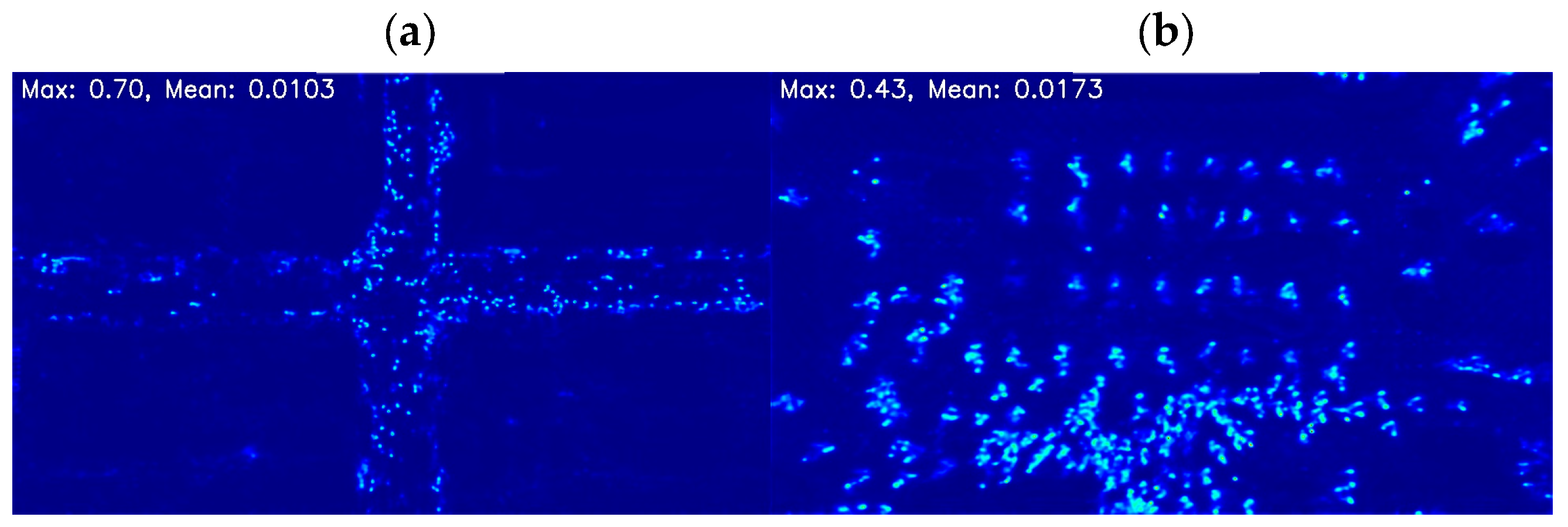

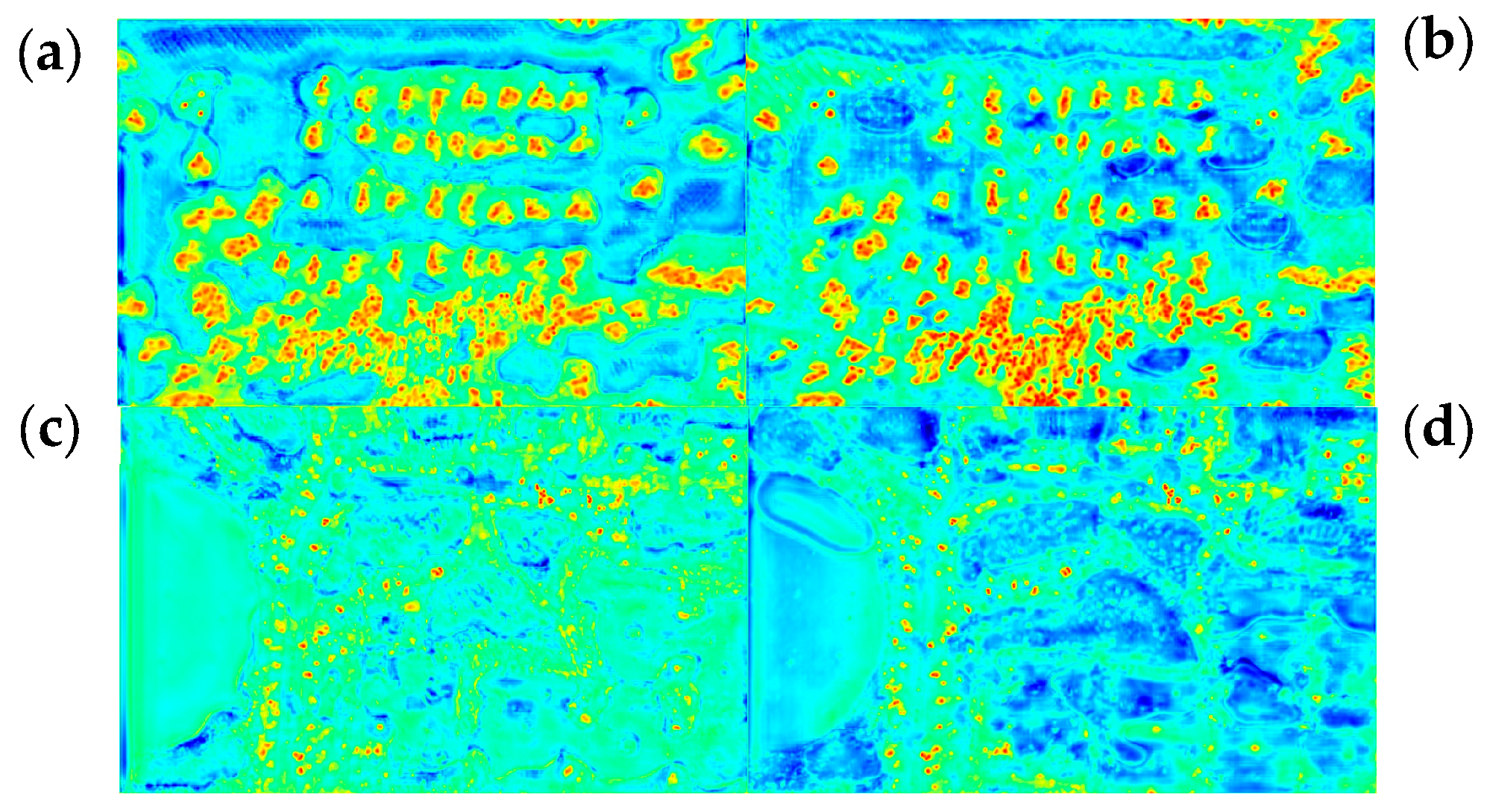

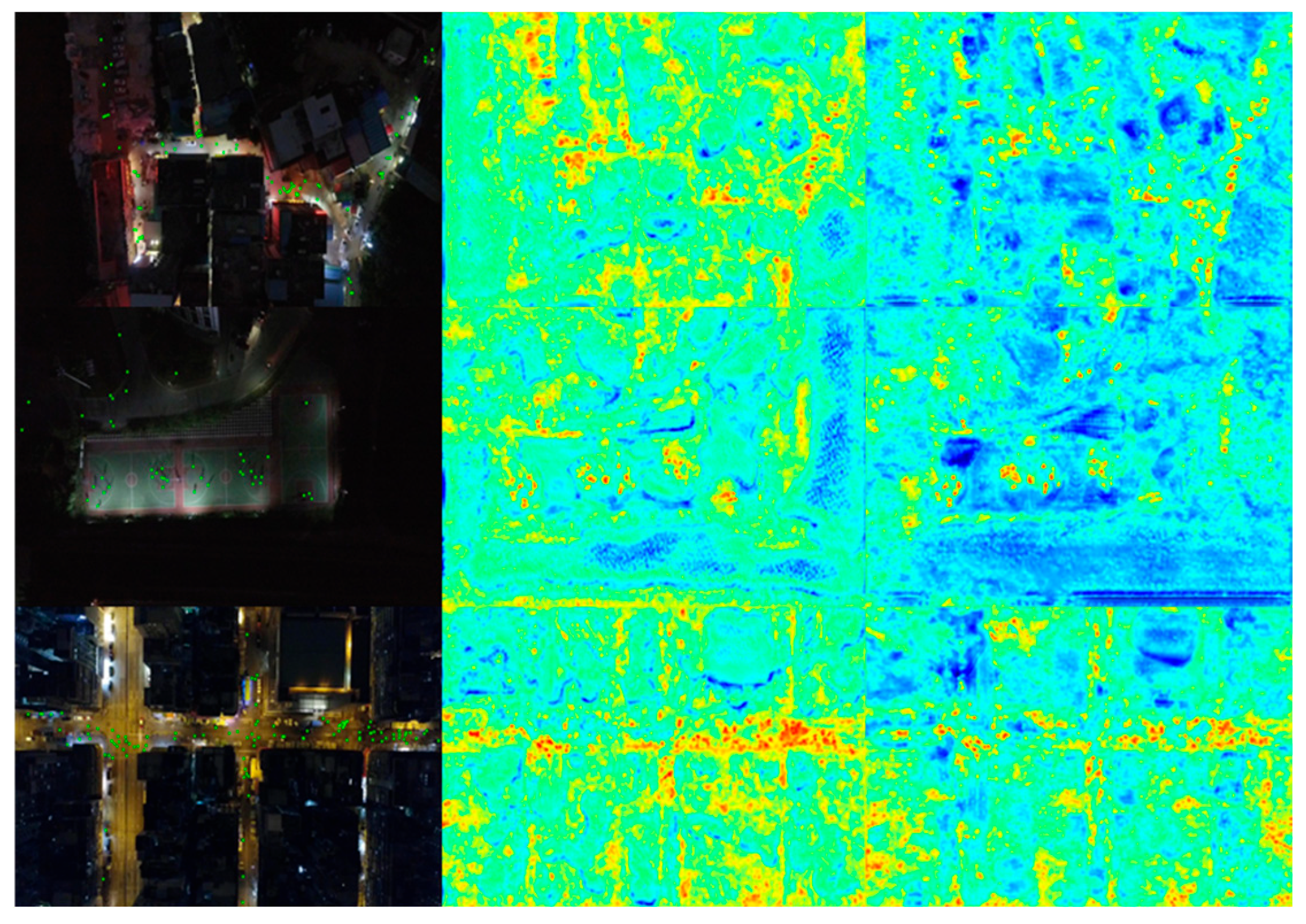

4.4. Visual Heatmap Comparison

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Barr, D.; Drury, J.; Butler, T.; Choudhury, S.; Neville, F. Beyond ‘stampedes’: Towards a new psychology of crowd crush disasters. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2024, 63, 52–69. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.J. Survey of Crowd Crush Disasters and Countermeasures. Prehosp. Disaster Med. 2023, 38, s78. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, A.; McCloskey, B.; Hui, D.S.; Rambia, A.; Zumla, A.; Traore, T.; Shafi, S.; El-Kafrawy, S.A.; Azhar, E.I.; Zumla, A.; et al. Global mass gathering events and deaths due to crowd surge, stampedes, crush and physical injuries-Lessons from the Seoul Halloween and other disasters. Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 2023, 52, 102524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, Y.; Zhu, H.; Yuan, J.; Xiang, G.; Zhong, X.; He, S. DenseTrack: Drone-Based Crowd Tracking via Density-Aware Motion-Appearance Synergy. In Proceedings of the 32nd ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Melbourne, Australia, 28 October–1 November 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Dronova, O.; Parinov, D.; Soloviev, B.; Kasumova, D.; Kochetkov, E.; Medvedeva, O.; Sergeeva, I. Unmanned aerial vehicles as element of road traffic safety monitoring. Transp. Res. Procedia 2022, 63, 2308–2314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butila, E.V.; Boboc, R.G. Urban traffic monitoring and analysis using unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs): A systematic literature review. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Bao, Z.; Xie, Z.; Huang, G.; Rehman, Z.U. A point and density map hybrid network for crowd counting and localization based on unmanned aerial vehicles. Connect. Sci. 2022, 34, 2481–2499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, L.; Du, D.; Zhu, P.; Hu, Q.; Wang, Q.; Bo, L.; Lyu, S. Detection, Tracking, and Counting Meets Drones in Crowds: A Benchmark. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 7808–7817. [Google Scholar]

- Asanomi, T.; Nishimura, K.; Bise, R. Multi-Frame Attention with Feature-Level Warping for Drone Crowd Tracking. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision, Waikoloa, HI, USA, 2–7 January 2023; pp. 1664–1673. [Google Scholar]

- Ptak, B.; Kraft, M. Enhancing people localisation in drone imagery for better crowd management by utilising every pixel in high-resolution images. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.04014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, S.; Park, J.; Lee, J.Y.; Kweon, I.S. CBAM: Convolutional Block Attention Module. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Chen, D. CSRNet: Dilated Convolutional Neural Networks for Understanding the Highly Congested Scenes. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 1091–1100. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Shi, M.; Zhao, Q.; Wang, X. Point in, Box Out: Beyond Counting Persons in Crowds. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 6462–6471. [Google Scholar]

- Sam, D.B.; Peri, S.V.; Sundararaman, M.N.; Kamath, A.; Babu, R.V. Locate, Size, and Count: Accurately Resolving People in Dense Crowds via Detection. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2021, 43, 2739–2751. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Song, Q.; Wang, C.; Jiang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Tai, Y.; Wang, C.; Li, J.; Huang, F.; Wu, Y. Rethinking Counting and Localization in Crowds: A Purely Point-Based Framework. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; pp. 3345–3354. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, D.; Xu, W.; Bai, X. An End-to-End Transformer Model for Crowd Localization. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Tel Aviv, Israel, 23–27 October 2022; pp. 235–251. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Lu, H.; Cao, Z.; Liu, T. Point-Query Quadtree for Crowd Counting, Localization, and More. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Paris, France, 1–6 October 2023; pp. 1676–1685. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, I.H.; Chen, W.T.; Liu, Y.W.; Yang, M.H.; Kuo, S.Y. Improving Point-based Crowd Counting and Localization Based on Auxiliary Point Guidance. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Milan, Italy, 29 September–4 October 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, D.; Xu, W.; Zhu, Y.; Zhou, Y. Focal Inverse Distance Transform Maps for Crowd Localization. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2023, 25, 6040–6052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idrees, H.; Tayyab, M.; Athrey, K.; Zhang, D.; Al-Maadeed, S.; Rajpoot, N.; Shah, M. Composition Loss for Counting, Density Map Estimation and Localization in Dense Crowds. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 532–546. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, J.; Han, T.; Yuan, Y.; Wang, Q. Domain-Adaptive Crowd Counting via High-Quality Image Translation and Density Reconstruction. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2023, 34, 4803–4815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, C.; Liang, D.; Xu, Y.; Bai, S.; Zhan, W.; Bai, X.; Tomizuka, M. AutoScale: Learning to Scale for Crowd Counting. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2022, 130, 405–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Han, T.; Wang, Q.; Yuan, Y.; Li, X. Learning Independent Instance Maps for Crowd Localization. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2012.04176. [Google Scholar]

- Abousamra, S.; Hoai, M.; Samaras, D.; Chen, C. Localization in the Crowd with Topological Constraints. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Virtual, 2–9 February 2021; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Han, T.; Bai, L.; Liu, L.; Ouyang, W. STEERER: Resolving Scale Variations for Counting and Localization via Selective Inheritance Learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 21848–21859. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, C.; Wang, J.; Yang, W.; Yu, H.; Yu, L.; Xia, G.S. RFLA: Gaussian Receptive Field Based Label Assignment for Tiny Object Detection. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Tel Aviv, Israel, 23–27 October 2022; pp. 450–467. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, Y.K.; Lin, G.S.; Yeh, M.C. A Transformer-Based Framework for Tiny Object Detection. In Proceedings of the Asia Pacific Signal and Information Processing Association Annual Summit and Conference, Beijing, China, 12–15 December 2023; pp. 373–377. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, E.; Wang, W.; Yu, Z.; Anandkumar, A.; Alvarez, J.M.; Luo, P. SegFormer: Simple and Efficient Design for Semantic Segmentation with Transformers. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2021, 34, 12077–12090. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, W.; Caballero, J.; Huszár, F.; Totz, J.; Aitken, A.P.; Bishop, R.; Rueckert, D.; Wang, Z. Real-Time Single Image and Video Super-Resolution Using an Efficient Sub-Pixel Convolutional Neural Network. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 1874–1883. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Z.; Wang, Z.; Huang, Y.; Wang, L.; Tan, T.; Zhou, E. Rethinking the Heatmap Regression for Bottom-up Human Pose Estimation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 13259–13268. [Google Scholar]

| Method | L-mAP | L-AP@10 | L-AP@15 | L-AP@20 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSRNet | 14.4% | 15.13% | 19.77% | 21.16% |

| STNNet | 40.45% | 42.75% | 50.98% | 55.77% |

| P2PNet | 29.44% | 17.76% | 38.42% | 52.71% |

| MFA | 43.43% | 47.14% | 51.58% | 54.02% |

| STEERER | 38.31% | 41.96% | 46.58% | 49.07% |

| RFLA | 32.05% | 34.41% | 39.59% | 42.52% |

| SD-DETR | 48.12% | 52.56% | 57.35% | 60.08% |

| UAV-Dot | 51.00% | 57.06% | 60.45% | 62.29% |

| Enhanced UAV-Dot | 53.38% | 59.07% | 63.11% | 64.96% |

| Adaptive Gaussian Kernel | CBAM | Post- Processing Correction | L-mAP | L-AP@10 | L-AP@15 | L-AP@20 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ✓ | 51.92% | 58.22% | 61.16% | 63.02% | ||

| ✓ | 52.62% | 58.34% | 61.99% | 63.83% | ||

| ✓ | ✓ | 52.88% | 58.65% | 62.37% | 64.25% | |

| ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 53.38% | 59.07% | 63.11% | 64.96% |

| Model | Training Parameters | Testing Parameters | Redenerende FPS | Algehele FPS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UAV-Dot | 27.5 M | 110.015 M | 19.63 ± 0.22 | 19.27 ± 0.24 |

| Enhanced UAV-Dot | 27.6 M | 110.314 M | 15.49 ± 0.58 | 15.18 ± 0.16 |

| Lighting Conditions | UAV-Dot | UAV-Dot with CBAM | Growth Situation | Enhanced UAV-Dot | Growth Situation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low-light group | 17.10% | 18.62% | 1.52% | 19.13% | 2.03% |

| Normal-light group | 52.80% | 53.65% | 0.85% | 55.22% | 2.42% |

| Position of CBAM | L-mAP | Training Parameters | Testing Parameters | FPS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| After the effective output layer of the encoder | 51.92% | 27.6 M | 110.209 M | 15.86 ± 0.45 |

| Decoder output | 51.23 % | 27.5 M | 110.060 M | 15.15 ± 0.28 |

| λ | L-mAP | L-AP@10 | L-AP@15 | L-AP@20 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.8 | 51.63% | 57.14% | 61.17% | 62.74% |

| 0.9 | 52.01% | 57.68% | 61.25% | 63.37% |

| 1 | 52.62% | 58.34% | 61.99% | 63.83% |

| 1.1 | 50.58% | 56.12% | 59.82% | 61.96% |

| Post- Processing Threshold | L-mAP | L-AP@10 | L-AP@15 | L-AP@20 | F1 Score@10 | F1 Score@15 | F1 Score@20 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No post-processing | 52.88% | 58.65% | 62.37% | 64.25% | 67.57% | 70.78% | 72.48% |

| 85/255 | 50.81% | 56.33% | 60.01% | 62.27% | 67.16% | 70.40% | 72.33% |

| 80/255 | 51.93% | 57.93% | 61.46% | 63.47% | 67.34% | 70.60% | 72.51% |

| 75/255 | 53.38% | 59.07% | 63.11% | 64.96% | 67.24% | 70.50% | 72.37% |

| 70/255 | 53.87% | 59.27% | 63.53% | 65.92% | 66.83% | 70.07% | 71.91% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, M.; Zhao, F.; Zhang, Y. Enhanced UAV-Dot for UAV Crowd Localization: Adaptive Gaussian Heat Map and Attention Mechanism to Address Scale/Low-Light Challenges. Drones 2025, 9, 833. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones9120833

Zhang M, Zhao F, Zhang Y. Enhanced UAV-Dot for UAV Crowd Localization: Adaptive Gaussian Heat Map and Attention Mechanism to Address Scale/Low-Light Challenges. Drones. 2025; 9(12):833. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones9120833

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Min, Fei Zhao, and Yan Zhang. 2025. "Enhanced UAV-Dot for UAV Crowd Localization: Adaptive Gaussian Heat Map and Attention Mechanism to Address Scale/Low-Light Challenges" Drones 9, no. 12: 833. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones9120833

APA StyleZhang, M., Zhao, F., & Zhang, Y. (2025). Enhanced UAV-Dot for UAV Crowd Localization: Adaptive Gaussian Heat Map and Attention Mechanism to Address Scale/Low-Light Challenges. Drones, 9(12), 833. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones9120833