Optimizing Nitrogen Inputs for High-Yielding and Environmentally Sustainable Potato Systems

Abstract

1. Introduction

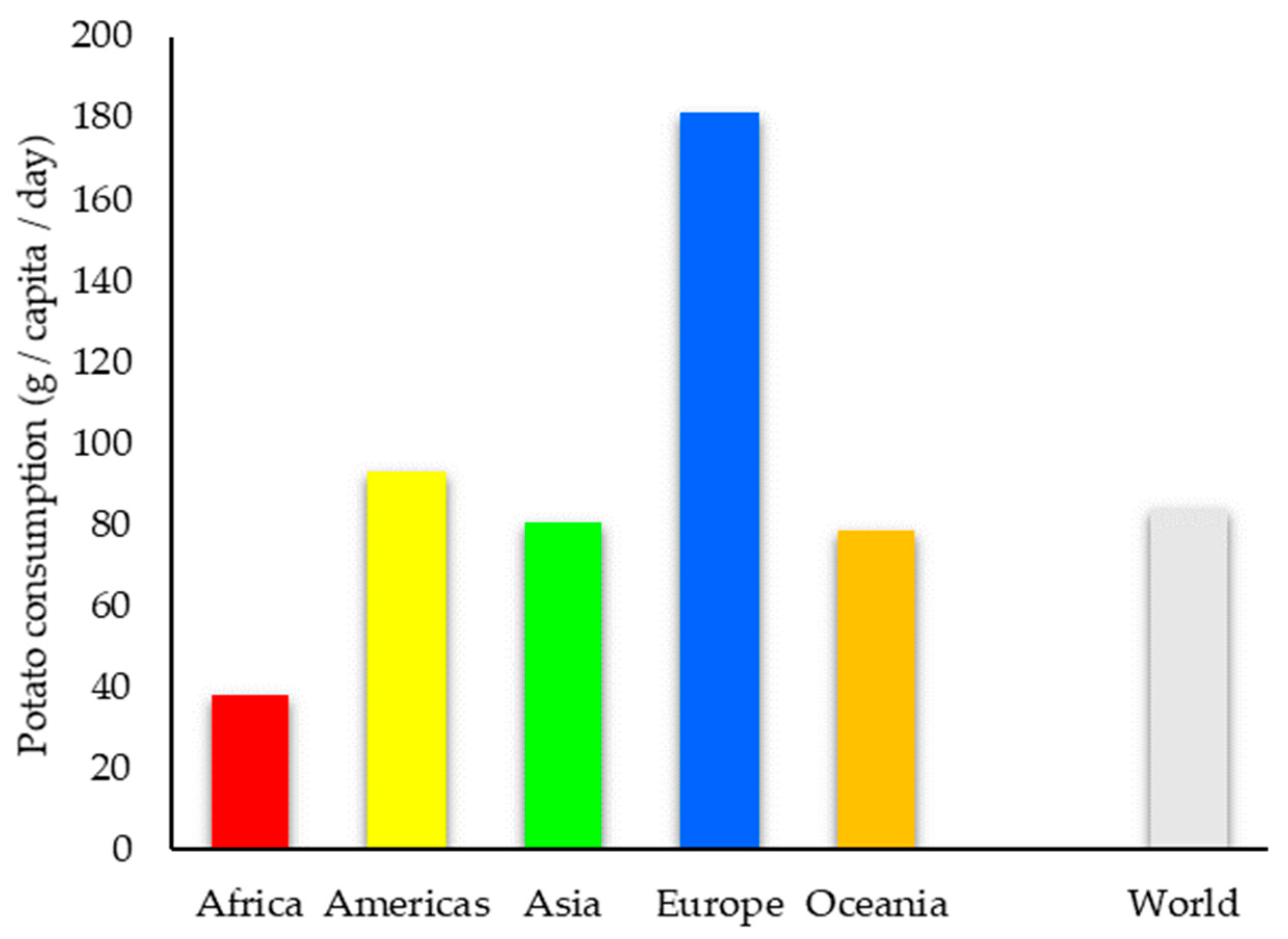

2. Worldwide Potato Production and Uses

2.1. Potato Production in the World

2.2. Uses and Importance of Potato Production

3. Sources and Forms of N Fertilizers

4. Environmental Implications of N Fertilization

4.1. Nitrate Leaching and Groundwater Pollution

4.2. Nitrous Oxide (N2O) Emissions

4.3. Soil Health Impacts

5. Mechanisms of Leaf Expansion, N Partitioning, and Enzymatic Activation

6. N Management in Potato Production

7. Beneficial Microorganisms

8. Sustainable N Frameworks

9. Conclusions and Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Haile, B. Biochar and Inorganic Fertilizers for Acidic Soil Management: Improving Soil Properties and Potato Productivity in Ethiopia. Curr. Trends Agron. Agric. Res. 2025, 1, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Pande, K.R.; Upadhyay, K.; Gaihre, Y.K. Improving Nitrogen Use Efficiency and Yields of Potato through Integrated Use of nitrogen Fertilizer and Organic Manures under Irrigated Condition in Nepal. SAARC J. Agric. 2025, 23, 237–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapčan, I.; Radočaj, D.M.; Jurišić, M. Analiza duljine vegetativnoga perioda za uzgoj kukuruza iz fenoloških metrika određenih korištenjem satelitskih snimaka sa sentinela-2. Poljoprivreda 2025, 31, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Jabeen, N.; Farruhbek, R.; Chachar, Z.; Laghari, A.A.; Chachar, S.; Ahmed, N.; Ahmed, S.; Yang, Z. Enhancing nitrogen use efficiency in agriculture by integrating agronomic practices and genetic advances. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1543714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benković, R.; Mirosavljević, K.; Brmež, M.; Etongo, D.; Zimmer, D.; Jug, D.; Benković-Lačić, T. Different Tillage Systems and Their Influence on Crops Yield Formation and Post-Harvest Residues. Poljoprivreda 2025, 31, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varga, I.; Markulj Kulundžić, A.; Tkalec Kojić, M.; Antunović, M. Does the Amount of Pre-Sowing Nitrogen Fertilization Affect Sugar Beet Root Yield and Quality of Different Genotypes? Nitrogen 2024, 5, 386–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Xu, Z.; Zhao, J.; Wang, Y.; Yu, Z. Excessive nitrogen application decreases grain yield and increases nitrogen loss in a wheat–soil system. Acta Agric. Scand. Sect. B Soil Plant Sci. 2011, 61, 681–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awadelkareem, W.; Haroun, M.; Wang, J.; Qian, X. Nitrogen Interactions Cause Soil Degradation in Greenhouses: Their Relationship to Soil Preservation in China. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getahun, B.B.; Kassie, M.M.; Visser, R.G.F.; van der Linden, C.G. Genetic Diversity of Potato Cultivars for Nitrogen Use Efficiency Under Contrasting N Regimes. Potato Res. 2020, 63, 267–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jozefowicz, A.M.; Hartmann, A.; Matros, A.; Schum, A.; Mock, H.-P. Nitrogen Deficiency Induced Alterations in the Root Proteome of a Pair of Potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) Varieties Contrasting for Their Response to Low N. Proteomics 2017, 17, 1700231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamaya, T. Genetic manipulation and quantitative-trait loci mapping for nitrogen recycling in rice. J. Exp. Bot. 2002, 53, 917–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kollaricsné Horváth, M.; Hoffmann, B.; Cernák, I.; Baráth, S.; Polgár, Z.; Taller, J. Nitrogen utilization of potato genotypes and expression analysis of genes controlling nitrogen assimilation. Biol. Futur. 2019, 70, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barandalla, L.; Alvarez-Morezuelas, A.; Iribar, C.; Ritter, E.; Riga, P.; Lacuesta, M.; de Galarreta, J.I.R. Physiological Response to nitrogen Deficit in Potato Under Greenhouse Conditions. Plants 2025, 14, 3237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varga, I.; Cerovečki, M.; Žulj, I.; Gantner, R.; Tadić, V.; Stošić, M. Redoslijed agrotehničkih mjera u proizvodnji krumpira za preradu u čips. Glas. Zaštite Bilja 2022, 45, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pospišil, A.; Vugrinec, J.; Pospišil, M. Gospodarska svojstva tradicijskih sorata krumpira Poli i Brinjak. Poljoprivreda 2023, 29, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarajlić, A.; Štreitenberger, L.; Kajan, L.; Mak, M.K.; Martić, B.; Šmituc, I.; Majić, I. Perillus bioculatus (Pentatomidae) kao potencijalni biološki agens u suzbijanju krumpirove zlatice (Leptinotarsa decemlineata). Poljoprivreda 2025, 31, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flint, E.A.; Yost, M.A.; Hopkins, B.G. On-Farm Variable Rate Nitrogen Management in Irrigated Potato. Precis. Agric. 2025, 26, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trenkel, M.E. Slow- and Controlled-Release and Stabilized Fertilizers: An Option for Enhancing Nutrient Use Efficiency in Agriculture; International Fertilizer Industry Association (IFA): Paris, France, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Shoji, S.; Delgado, J.; Mosier, A.; Miura, Y. Use of Controlled Release Fertilizers and Nitrification Inhibitors to Increase Nitrogen Use Efficiency and to Conserve Air and Water Quality. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2001, 32, 1051–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zareabyaneh, H.; Bayatvarkeshi, M. Effects of Slow-Release Fertilizers on Nitrate Leaching, Its Distribution in Soil Profile, N-Use Efficiency, and Yield in Potato Crop. Environ. Earth Sci. 2015, 74, 3385–3393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Ling, Y.; Chang, W.; Yin, M.; Kang, Y.; Ma, Y.; Wang, Y.; Qi, G.; Liu, B. Exploring the Potential of N Fertilizer Mixed Application to Improve Crop Yield and Nitrogen Partial Productivity: A Meta-Analysis. Plants 2025, 14, 2417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, G.; Fan, X.; Miller, A.J. Plant Nitrogen Assimilation and Use Efficiency. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2012, 63, 153–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Sangwan, P.; Kumar, V.; Pandey, A.K.; Pooja; Kumar, A.; Chauhan, P.; Koubouris, G.; Fanourakis, D.; Parmar, K. Physio-Biochemical Insights of Endophytic Microbial Community for Crop Stress Resilience: An Updated Overview. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2025, 44, 2641–2664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Rithesh, L.; Raghuvanshi, N.; Kumar, A.; Parmar, K. Advancing N use efficiency in cereal crops: A comprehensive exploration of genetic manipulation, N dynamics, and plant Nitrogen assimilation. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2024, 169, 486–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Sámano, M.; Nanjareddy, K.; Arthikala, M.-K. NIN-like proteins (NLPs) as crucial nitrate sensors: An overview of their roles in N signaling, symbiosis, abiotic stress, and beyond. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2024, 30, 1209–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, W.; Feng, Y.; Liu, C.; Shi, X.; Han, L.; Liu, C.; Zhou, Y. Transcriptomic and Metabolomic Unraveling of Nitrogen Use Efficiency in Sorghum: The Quest for Molecular Adaptations to Low-N Stress. Plant Growth Regul. 2025, 105, 687–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Ma, Q.; Shan, F.; Tian, L.; Gong, J.; Quan, W.; Yang, W.; Hou, Q.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, S. Transcriptional Regulation Mechanism of Wheat Varieties with Different Nitrogen Use Efficiencies in Response to N Deficiency Stress. BMC Genom. 2022, 23, 727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Li, S.; Li, J.; Huang, D. The Utilization and Roles of Nitrogen in Plants. Forests 2024, 15, 1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The, S.V.; Snyder, R.; Tegeder, M. Targeting Nitrogen Metabolism and Transport Processes to Improve Plant Nitrogen Use Efficiency. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 11, 628366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zebarth, B.J.; Rosen, C.J. Research perspective on nitrogen BMP development for potato. Am. J. Potato Res. 2007, 84, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.; Qin, J.; Jian, Y.; Liu, J.; Bian, C.; Jin, L.; Li, G. Analysis of Potato Physiological and Molecular Adaptation in Response to Different Water and Nitrogen Combined Regimes. Plants 2023, 12, 1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutula, M.; Tussipkan, D.; Kali, B.; Manabayeva, S. Molecular Mechanisms Underlying Defense Responses of Potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) to Environmental Stress and CRISPR/Cas-Mediated Engineering of Stress Tolerance. Plants 2025, 14, 1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawkes, J.G. History of the Potato. In The Potato Crop; Harris, P.M., Ed.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swamy, K.R.M. Origin, domestication, taxonomy, botanical description, genetics and cytogenetics, genetic diversity and breeding of potato (Solanum tuberosum L.). Int. J. Curr. Res. 2023, 15, 24352–24372. Available online: https://journalcra.com/article/origin-domestication-taxonomy-botanical-description-genetics-and-cytogenetics-genetc (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- FAOStat. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#home (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Mickiewicz, B.; Volkova, E.; Jurczak, R. The Global Market for Potato and Potato Products in the Current and Forecast Period. Eur. Res. Stud. J. 2022, 25, 740–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldiz, D.O. Potato Production in South America. In Potato Production Worldwide; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 409–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loayza Aguilar, J.; Villca Goméz, Z.; Canqui Villarroel, J.C. Producción de Papa (Solanum tuberosum) y Tizón Tardío en Bolivia. Rev. Cambios Permanencias 2024, 8, 12171–12181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devaux, A.; Ordinola, M.; Suarez, V.; Hareau, G. Current Status and Prospects of Potato Processing in the Andean Zone, Implications for Breeding and Variety Selection; International Potato Center (CIP); CGIAR: Lima, Peru; Available online: https://cgspace.cgiar.org (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Muthoni, J.; Shimelis, H. An Overview of Potato Production in Africa. In Potato Production Worldwide; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 435–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthoni, J.; Shimelis, H.; Mashilo, J. Production and Availability of Good Quality Seed Potatoes in the East African Region: A Review. Aust. J. Crop Sci. 2022, 16, 907–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, R.; Robinson, A.; Thornton, M.; Vander Zaag, P. Potato Production in the United States and Canada. In Potato Production Worldwide; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 365–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, E.; Ines, A.V.M.; Fleisher, D.H. Past and Future Changes in Potato Production Vulnerabilities in Maine, U.S. Clim. Change 2025, 178, 140. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10584-025-03977-6 (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Scott, G.J.; Suarez, V. The Rise of Asia as the Centre of Global Potato Production and Some Implications for Industry. Potato J. 2012, 39, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Levy, D.; Veilleux, R.E. Adaptation of Potato to High Temperatures and Salinity: A Review. Am. J. Potato Res. 2007, 84, 487–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handayani, T.; Gilani, S.A.; Watanabe, K.N. Climatic Changes and Potatoes: How Can We Cope with the Abiotic Stresses? Breed. Sci. 2019, 69, 545–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CGIAR. Available online: https://www.cgiar.org/research/center/cip/ (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Varga, I.; Đurović, V. Trendovi proizvodnje i konzumacije krumpira u svijetu. Glas. Zaštite Bilja 2023, 46, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Martínez, B.; Coelho, E.; Gullón, B.; Yáñez, R.; Domingues, L. Potato Peels Waste as a Sustainable Source for Biotechnological Production of Biofuels: Process Optimization. Waste Manag. 2023, 155, 320–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanal, S.; Karimi, K.; Majumdar, S.; Rodríguez-Martínez, B.; Coelho, E.; Gullón, B.; Yáñez, R.; Domingues, L. Sustainable Utilization and Valorization of Potato Waste: State of the Art, Challenges, and Perspectives. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 2024, 14, 23335–23360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amicarelli, V.; Roe, B.E.; Bux, C. Measuring Food Loss and Waste Costs in the Italian Potato Chip Industry Using Material Flow Cost Accounting. Agriculture 2022, 12, 523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhivkova, V. Potato Waste and Sweet Potato Waste Utilization—Some Research Trends. E3S Web Conf. 2024, 563, 03080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalczyk, T.; Muskała, M.; Merecz-Sadowska, A.; Sikora, J.; Picot, L.; Sitarek, P. Anti-Inflammatory and Anticancer Effects of Anthocyanins in In Vitro and In Vivo Studies. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andre, C.M.; Schafleitner, R.; Guignard, C.; Oufir, M.; Aliaga, C.A.; Nomberto, G.; Hoffmann, L.; Hausman, J.F.; Evers, D.; Larondelle, Y. Modification of the health-promoting value of potato tubers field grown under drought stress: Emphasis on dietary antioxidant and glycoalkaloid contents in five native Andean cultivars (Solanum tuberosum L.). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 599–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnesen, E.K.; Laake, I.; Carlsen, M.H.; Veierød, M.B.; Retterstøl, K. Potato Consumption and All-Cause and Cardiovascular Disease Mortality: A Long-Term Follow-Up of a Norwegian Cohort. J. Nutr. 2024, 154, 2226–2235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visvanathan, R.; Jayathilake, C.; Jayawardana, B.C.; Liyanage, R. Health-beneficial properties of potato and compounds of interest. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2016, 96, 4850–4860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muttucumaru, N.; Powers, S.J.; Elmore, J.S.; Mottram, D.S.; Halford, N.G. Effects of Nitrogen and Sulfur Fertilization on Free Amino Acids, Sugars, and Acrylamide-Forming Potential in Potato. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013, 61, 6511–6520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, N.; Rosen, C.J.; Thompson, A.L. Acrylamide Formation in Processed Potatoes as Affected by Cultivar, Nitrogen Fertilization and Storage Time. Am. J. Potato Res. 2018, 95, 473–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Wilde, T.; De Meulenaer, B.; Mestdagh, F.; Govaert, Y.; Vandeburie, S.; Ooghe, W.; Fraselle, S.; Demeulemeester, K.; Van Peteghem, C.; Calus, A.; et al. Influence of Fertilization on Acrylamide Formation during Frying of Potatoes Harvested in 2003. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 54, 7010–7016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hina, N.S. Global Meta-Analysis of Nitrate Leaching Vulnerability in Synthetic and Organic Fertilizers over the Past Four Decades. Water 2024, 16, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagan, K.; Jonak, K.; Wolińska, A. The Impact of Reduced N Fertilization Rates According to the “Farm to Fork” Strategy on the Environment and Human Health. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 10726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Q.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, F.; Shen, Y.; Yue, S.; Li, S. Optimized N Application for Maximizing Yield and Minimizing N Loss in Film Mulching Spring Maize Production on the Loess Plateau, China. J. Integr. Agric. 2024, 23, 1671–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, S.; Cui, N.; Wang, Y.; Gong, D.; Xing, L.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z. Determining Effect of Fertilization on Reactive Nitrogen Losses through Nitrate Leaching and Key Influencing Factors in Chinese Agricultural Systems. Agric. Water Manag. 2024, 303, 109055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, I.; Lv, J.; Yang, L.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Liu, H. Low Irrigation Water Minimizes the Nitrate Nitrogen Losses without Compromising the Soil Fertility, Enzymatic Activities and Maize Growth. BMC Plant Biol. 2022, 22, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, W.; Wang, Q.; Chen, S.; Chen, F.; Lv, H.; Li, J.; Chen, Q.; Zhou, J.; Liang, B. Nitrate Leaching Is the Main Driving Factor of Soil Calcium and Magnesium Leaching Loss in Intensive Plastic-Shed Vegetable Production Systems. Agric. Water Manag. 2024, 293, 108708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peralta, J.M.; Stockle, C.O. Dynamics of Nitrate Leaching under Irrigated Potato Rotation in Washington State: A Long-Term Simulation Study. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2002, 88, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Dalmau, J.; Berbel, J.; Ordóñez-Fernández, R. Nitrogen Fertilization. A Review of the Risks Associated with the Inefficiency of Its Use and Policy Responses. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sainju, U.M.; Ghimire, R.; Pradhan, G.P. N Fertilization I: Impact on Crop, Soil, and Environment; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemmou, L.; Amanatidou, E. Factors Affecting Nitrous Oxide Emissions from Activated Sludge Wastewater Treatment Plants—A Review. Resources 2023, 12, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.; Ni, B.J.; Erler, D.; Ye, L.; Yuan, Z. The effect of dissolved oxygen on N2O production by ammonia-oxidizing bacteria in an enriched nitrifying sludge. Water Res. 2014, 66, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis; Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Masson-Delmotte, V., Zhai, P., Pirani, A., Connors, S.L., Péan, C., Berger, S., Caud, N., Chen, Y., Goldfarb, L., Gomis, M.I., et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2021; p. 2391. [Google Scholar]

- WMO. Greenhouse Gas Bulletin No. 20: The State of Greenhouse Gases in the Atmosphere Based on Global Observations Through 2023; World Meteorological Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024; Available online: https://public.wmo.int/ (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- NOAA. Trends in Atmospheric Nitrous Oxide (N2O); Global Monitoring Laboratory, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. Available online: https://gml.noaa.gov/ccgg/trends_n2o/ (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Butterbach-Bahl, K.; Baggs, E.M.; Dannenmann, M.; Kiese, R.; Zechmeister-Boltenstern, S. Nitrous Oxide Emissions from Soils: How Well Do We Understand the Processes and Their Controls? Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2013, 368, 20130122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Lu, P.; Feng, S.; Hamel, C.; Sun, D.; Siddique, K.H.M.; Gan, G.Y. Strategies to Improve Soil Health by Optimizing the Plant–Soil–Microbe–Anthropogenic Activity Nexus. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2024, 359, 108750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Xiang, T.; Wang, F.; Peng, J.; Yang, S.; Cao, W. Nitrification regulates the responses of soil nitrous oxide emissions to N addition in China: A meta-analysis from a gene perspective. Environ. Sci. Process. Impacts 2025, 27, 2367–2378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Signor, D.; Cerri, C.E.P. Nitrous oxide emissions in agricultural soils: A review. Pesqui. Agropecuária Trop. 2013, 43, 322–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shcherbak, I.; Millar, N.; Robertson, G.P. Global metanalysis of the nonlinear response of soil nitrous oxide (N2O) emissions to fertilizer nitrogen. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 9199–9204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, S.K.; Suter, H.; Mosier, A.R.; Chen, D. Using nitrification inhibitors to mitigate agricultural N2O emission: A double-edged sword? Glob. Change Biol. 2017, 23, 485–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akiyama, H.; Yan, X.; Yagi, K. Evaluation of effectiveness of enhanced-efficiency fertilizers as mitigation options for N2O and NO emissions from agricultural soils: Meta-analysis. Glob. Change Biol. 2010, 16, 1837–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cayuela, M.L.; van Zwieten, L.; Singh, B.P.; Jeffery, S.; Roig, A.; Sánchez-Monedero, M.A. Biochar’s role in mitigating soil nitrous oxide emissions: A review and meta-analysis. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2014, 191, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reay, D.S.; Davidson, E.A.; Smith, K.A.; Smith, P.; Melillo, J.M.; Dentener, F.; Crutzen, P.J. Global agriculture and nitrous oxide emissions. Nat. Clim. Change 2012, 2, 410–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Xu, R.; Canadell, J.G.; Thompson, R.L.; Winiwarter, W.; Suntharalingam, P.; Davidson, E.A.; Ciais, P.; Jackson, R.B.; Janssens-Maenhout, G.; et al. A comprehensive quantification of global nitrous oxide sources and sinks. Nature 2020, 586, 248–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braakhekke, M.C.; Rebel, K.T.; Dekker, S.C.; Smith, B.; Beusen, A.H.W.; Wassen, M.J. Nitrogen Leaching from Natural Ecosystems under Global Change: A Modelling Study. Earth Syst. Dynam 2017, 8, 1121–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garthen, A.; Berg, J.P.; Ehrnsten, E.; Klisz, M.; Weigel, R.; Wilke, L.; Kreyling, J. High Nitrate and Sulfate Leaching in Response to Wetter Winters in Temperate Beech Forests. Basic. Appl. Ecol. 2024, 80, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. FAOSTAT: Crops; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2022; Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/FBS (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Doran, J.W.; Parkin, T.B. Defining and assessing soil quality. In Defining Soil Quality for a Sustainable Environment; SSSA Special Publication 35; Doran, J.W., Coleman, D.C., Bezdicek, D.F., Stewart, B.A., Eds.; Soil Science Society of America: Madison, WI, USA, 1994; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- FAO; ITPS; GSBI; SCBD; EC. State of Knowledge of Soil Biodiversity—Status, Challenges and Potentialities, Report 2020; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020; Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/items/24035f6b-eed4-40a8-a838-b45b866c35c2 (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Lal, R. Soil carbon sequestration impacts on global climate change and food security. Science 2004, 304, 1623–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.H.; Liu, X.J.; Zhang, Y.; Shen, J.L.; Han, W.X.; Zhang, W.F.; Christie, P.; Goulding, K.W.T.; Vitousek, P.M.; Zhang, F.S. Significant acidification in major Chinese croplands. Science 2010, 327, 1008–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geisseler, D.; Scow, K.M. Long-term effects of mineral fertilizers on soil microorganisms—A review. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2014, 75, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhao, Z.; Jiang, B.; Baoyin, B.; Cui, Z.; Wang, H.; Li, Q.; Cui, J. Effects of Long-Term Application of N Fertilizer on Soil Acidification and Biological Properties in China: A Meta-Analysis. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B. Are N Fertilizers Deleterious to Soil Health? Agronomy 2018, 8, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, J.; Dungait, J.A.J.; Delgado-Baquerizo, M.; Cui, Z.; Zhou, R.; Zhang, W.; Gao, Q.; Chen, Y.; Yue, S.; Kuzyakov, Y.; et al. Soil organic carbon thresholds control fertilizer effects on carbon accrual in croplands worldwide. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 3009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ierna, A.; Mauromicale, G. Sustainable and Profitable N Fertilization Management of Potato. Agronomy 2019, 9, 582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuoka, M.; Furbank, R.T.; Fukayama, H.; Miyao, M. Molecular engineering of C4 photosynthesis. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 2001, 52, 297–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahal, K.; Li, X.-Q.; Tai, H.; Creelman, A.; Bizimungu, B. Improving potato stress tolerance and tuber yield under a climate change scenario—A current overview. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vos, J.; van der Putten, P.E.L. Effect of nitrogen supply on leaf growth, leaf nitrogen economy and photosynthetic capacity in potato. Field Crops Res. 1998, 59, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vos, J.; Biemond, H. N Nutrition Effects on Development, Growth and nitrogen Accumulation of Vegetables: Effects of nitrogen on the Development and Growth of the Potato Plant. 1. Leaf Appearance, Expansion Growth, Life Spans of Leaves and Stem Branching. Ph.D. Thesis, Wageningen Agricultural University, Wageningen, The Netherlands, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Villa, P.M.; Sarmiento, L.; Rada, F.J.; Machado, D.; Rodrigues, A.C. Leaf area index of potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) crop under three N fertilization treatments. Agron. Colomb. 2017, 35, 171–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadas, W.; Dziugieł, T. Effect of complex fertilizers used in early crop potato culture on loamy sand soil. J. Cent. Eur. Agric. 2015, 16, 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, J.K.; Buckseth, T.; Singh, R.K.; Kumar, M.; Kant, S. Prospects of improving nitrogen use efficiency in potato: Lessons from transgenics to genome editing strategies in plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 597481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Pu, X.; Jia, H.; Zhou, Y.; Ye, G.; Yang, Y.; Na, T.; Wang, J. Transcriptome analysis reveals multiple effects of nitrogen accumulation and metabolism in the roots, shoots, and leaves of potato (Solanum tuberosum L.). BMC Plant Biol. 2022, 22, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Lu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Han, Z.; Han, Y.; Zhang, J. Analysis of Relative Expression of Key Enzyme Genes and Enzyme Activity in N Metabolic Pathway of Two Genotypes of Potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) under Different Nitrogen Supply Levels. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, R.; Jin, X.; Fang, J.; Wei, S.; Ma, J.; Liu, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Chen, L.; Liu, J.; Liu, Y.; et al. Exploring the Molecular Landscape of Nitrogen Use Efficiency in Potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) under Low Nitrogen Stress: A Transcriptomic and Metabolomic Approach. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsibart, A.S.; Dillen, J.; Van Craenenbroeck, L.; Elsen, A.; Postelmans, A.; van De Ven, G.; Saeys, W. Scenarios for Precision Nitrogen Management in Potato: Impact on Yield, Tuber Quality and Post-Harvest Nitrate Residues in the Soil. Field Crops Res. 2024, 319, 109648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şanlı, A.; Cansever, G.; Ok, F.Z. Effects of Humic Acid Applications along with Reduced Nitrogen Fertilization on Potato Tuber Yield and Quality. Turk. J. Agric.-Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 12, 2895–2900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Wang, H.; Liu, J.; Wang, R.; Che, Z. Effects of Root Trace N Reduction in Arid Areas on Sucrose–Starch Metabolism of Flag Leaves and Grains and Yield of Drip-Irrigated Spring Wheat. Agronomy 2024, 14, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bešlić, M.; Varga, I.; Antunović, M. Agrotechnical Approaches in Potato Production: A SWOT-Based Review. In Proceedings of the 60th Croatian & 20th International Symposium on Agriculture; Majić, I., Antunović, Z., Eds.; Faculty of Agrobiotechnical Sciences Osijek, University Josip Juraj Strossmayer in Osijek: Bol, Croatia, 2025; pp. 33–37. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Zhou, Q.; Liu, L.; Yang, Y.; An, J. Plastic Film Mulching and Compound Fertilizer Ratios Synergistically Enhance Potato Yield, Quality, and Nutrient Use Efficiency in Alpine Regions of Southwestern China. Preprint 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Jhangiryan, T.; Hunanyan, S.; Markosyan, A.; Yeritsyan, S.; Eloyan, A.; Barseghyan, M.; Gasparyan, G. Assessing the Effect of Joint Application of Mineral Fertilizers and Biohumus on Potato Yield Quality Indicators. Funct. Food Sci. 2024, 4, 508–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Luo, S.; Zha, Y.; Jiang, X.; Wang, X.; Chen, H.; Han, S. Impacts of Multi-Strategy Nitrogen Fertilizer Management on Potato Yield and Economic Gains in Northeast China. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kołodziejczyk, M.; Wszelaczyńska, E.; Flis, B. Effect of Nitrogen Fertilization and Microbial Preparations on Potato Yielding. Plant Soil Environ. 2014, 60, 322–327. Available online: https://pse.agriculturejournals.cz/artkey/pse-201408-0007_effect-of-nitrogen-fertilization-and-microbial-preparations-on-potato-yielding.php (accessed on 10 October 2025). [CrossRef]

- Nurmanov, Y.T.; Chernenok, V.G.; Kuzdanova, R.S. Potato in response to nitrogen nutrition regime and N fertilization. Field Crops Res. 2019, 231, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badr, M.A.; El-Tohamy, W.A.; Zaghloul, A.M. Yield and Water Use Efficiency of Potato Grown under Different Irrigation and Nitrogen Levels in an Arid Region. Agric. Water Manag. 2012, 110, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zewide, I.; Mohammed, A.; Tulu, S. Effect of different rates of nitrogen and phosphorus on yield and yield components of potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) at Masha District, Southwestern Ethiopia. Int. J. Soil Sci. 2012, 7, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, G.A.; Ocaya, P.C. N, Calcium, Boron, and Potassium Effects on Potato Quality; Progress Report to the Maine Potato Board; University of Maine, Aroostook Research Farm: Orono, ME, USA, 2018. Available online: https://www.mainepotatoes.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Nitrogen-calcium-boron-and-potassium-effects-on-potato-quality.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Su, W.; Ma, L.; Yang, J.; Li, J.; Song, W.; Gao, Y. Potato Growth, N Balance, Quality, and Productivity in Response to Different Nitrogen and Water Regimes. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1451350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zebarth, B.J.; Leclerc, Y.; Moreau, G.; Lalonde, M. Rate and Timing of Nitrogen Fertilization of Russet Burbank Potato: Yield and Processing Quality. Can. J. Plant Sci. 2004, 84, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardo, S.; Pandino, G.; Mauromicale, G. Optimizing Nitrogen Fertilization to Improve Qualitative Performances and Physiological and Yield Responses of Potato (Solanum tuberosum L.). Agronomy 2020, 10, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abewoy, D. Plant spacing and nitrogen fertilizer effect on potato (Solanum tuberosum) growth, yield and quality: Review. Glob. Acad. J. Agri. Biosci. 2024, 6, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Duan, Y.; Zhang, J.; Ciampitti, I.A.; Cui, J.; Qiu, S.; Xu, X.; Zhao, S.; He, P. Response of potato yield, soil chemical and microbial properties to different rotation sequences of green manure–potato cropping in North China. Soil Tillage Res. 2022, 217, 105273. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0167198721003469 (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Jović, J.; Ivezić, V.; Popović, B.; Guberac, V.; Rastija, M.; Dujmović, L.; Kristek, S. Utjecaj primjene mikrobioloških preparata na odabrana svojstva kiselih tala. Poljoprivreda 2025, 31, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, D.H.; Sharifi, M.; Hammermeister, A.; Burton, D. N Management in Organic Potato Production. In Sustainable Potato Production: Global Case Studies; He, Z., Ed.; Springer Science+Business Media B.V.: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012; p. 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Song, Y.; An, Y.; Lu, Y.; Zhong, G. Soil Microorganisms: Their Role in Enhancing Crop Nutrition and Health. Diversity 2024, 16, 734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lončarić, Z.; Novaković, I.; Perić, K.; Nemet, F.; Ravnjak, B.; Tkalec Kojić, M.; Vinković, T. Biološki test s četiri biljne vrste za procjenu pogodnosti vermikomposta i komposta kao uzgojnog medija. Poljoprivreda 2024, 30, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Țopa, D.-C.; Căpșună, S.; Calistru, A.-E.; Ailincăi, C. Sustainable Practices for Enhancing Soil Health and Crop Quality in Modern Agriculture: A Review. Agriculture 2025, 15, 998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brundrett, M.C.; Tedersoo, L. Evolutionary history of mycorrhizal symbioses and global host plant diversity. New Phytol. 2018, 220, 1108–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, F.A.; Smith, S.E. What is the significance of the arbuscular mycorrhizal colonisation of many economically important crop plants? Plant Soil 2011, 348, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Geel, M.; De Beenhouwer, M.; Lievens, B.; Honnay, O. Crop-specific and single-species mycorrhizal inoculation is the best approach to improve crop growth in controlled environments. Agron. Sustain. 2016, 36, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitterlich, M.; Franken, P. Connecting polyphosphate translocation and hyphal water transport points to a key of mycorrhizal functioning. New Phytol. 2016, 211, 1147–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercy, L.; Lucic-Mercy, E.; Nogales, A.; Poghosyan, A.; Schneider, C.; Arnholdt-Schmitt, B. A functional approach towards understanding the role of the mitochondrial respiratory chain in an Endomycorrhizal symbiosis. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rich, M.K.; Nouri, E.; Courty, P.E.; Reinhardt, D. Diet of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi: Bread and Butter? Trends Plant Sci. 2017, 22, 652–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Shi, J.; Xie, Q.; Jiang, Y.; Yu, N.; Wang, E. Nutrient Exchange and Regulation in Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Symbiosis. Mol. Plant 2017, 10, 1147–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bücking, H.; Mensah, J.A.; Fellbaum, C.R. Common Mycorrhizal Networks and Their Effect on the Bargaining Power of the Fungal Partner in the Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Symbiosis. Commun. Integr. Biol. 2016, 9, e1107684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deja-Sikora, E.; Mercy, L.; Baum, C.; Hrynkiewicz, K. The Contribution of Endomycorrhiza to the Performance of Potato Virus Y-Infected Solanaceous Plants: Disease Alleviation or Exacerbation? Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, M.; Ehret, D.L.; Krumbein, A.; Leung, C.; Murch, S.; Turi, C.; Franken, P. Inoculation with Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi Improves the Nutritional Value of Tomatoes. Mycorrhiza 2015, 25, 359–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouphael, Y.; Franken, P.; Schneider, C.; Schwarz, D.; Giovannetti, M.; Agnolucci, M.; de Pascale, S.; Bonini, P.; Colla, G. Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi Act as Biostimulants in Horticultural Crops. Sci. Hortic. 2015, 196, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, S.; Rabara, R.C.; Negi, S. AMF: The future prospect for sustainable agriculture. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2018, 102, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitterlich, M.; Rouphael, Y.; Graefe, J.; Franken, P. Arbuscular Mycorrhizas: A promising component of plant production systems provided favorable conditions for their growth. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, P.D.; Mahmood, S. Dry matter production and partitioning in potato plants subjected to combined deficiencies of N, phosphorus and potassium. Ann. Appl. Biol. 2003, 143, 215–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potatoes South Africa. Multimedia Guide to Potato Production in South Africa. 2020. Available online: https://www.nbsystems.co.za/potato/ (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Jin, H.; Pfeffer, P.E.; Douds, D.D.; Piotrowski, E.; Lammers, P.J.; Shachar-Hill, Y. The uptake, metabolism, transport and transfer of N in an arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis. New Phytol. 2005, 168, 687–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuab, R.; Lone, R.; Koul, K.K. Influence of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi on storage metabolites, mineral nutrition, and N-assimilating enzymes in potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) plant. J. Plant Nutr. 2017, 40, 1386–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindarajulu, M.; Pfeffer, P.E.; Jin, H.R.; Abubaker, J.; Douds, D.D.; Allen, J.W.; Bucking, H.; Lammers, P.J.; Shachar-Hill, Y. N transfer in the arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis. Nature 2005, 435, 819–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawkins, H.J.; Johansen, A.; George, E. Uptake and transport of organic and inorganic N by arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Plant Soil 2000, 226, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saia, S.; Rappa, V.; Ruisi, P.; Abenavoli, M.R.; Sunseri, F.; Giambalvo, D.; Frenda, A.S.; Martinelli, F. Soil inoculation with symbiotic microorganisms promotes plant growth and nutrient transporter genes expression in durum wheat. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 815. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/plant-science/articles/10.3389/fpls.2015.00815/full (accessed on 10 October 2025). [CrossRef]

- Thirkell, T.J.; Cameron, D.D.; Hodge, A. Resolving the ‘N paradox’of Arbuscular mycorrhizas: Fertilization with organic matter brings considerable benefits for plant nutrition and growth. Plant Cell Environ. 2016, 39, 1683–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guether, M.; Balestrini, R.; Hannah, M.; He, J.; Udvardi, M.K.; Bonfante, P. Genome-wide reprogramming of regulatory networks, transport, cell wall and membrane biogenesis during arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis in Lotus japonicus. New Phytol. 2009, 182, 200–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guether, M.; Neuhäuser, B.; Balestrini, R.; Dynowski, M.; Ludewig, U.; Bonfante, P. A mycorrhizal-specific ammonium transporter from Lotus japonicus acquires nitrogen released by arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Plant Physiol. 2009, 150, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asghari, H.R.; Cavagnaro, T.R. Arbuscular mycorrhizas reduce nitrogen loss via leaching. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e29825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavagnaro, T.R.; Bender, S.F.; Asghari, H.R.; van der Heijden, M.G. The role of Arbuscular mycorrhizas in reducing soil nutrient loss. Trends Plant Sci. 2015, 20, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köhl, L.; van der Heijden, M.G. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal species differ in their effect on nutrient leaching. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2016, 94, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodge, A.; Fitter, A.H. Substantial nitrogen acquisition by arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi from organic material has implications for N cycling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 13754–13759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treseder, K.K.; Allen, M.F. Direct nitrogen and phosphorus limitation of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi: A model and field test. New Phytol. 2002, 155, 507–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Püschel, D.; Janoušková, M.; Hujslová, M.; Slavíková, R.; Gryndlerová, H.; Jansa, J. Plant–fungus competition for nitrogen erases mycorrhizal growth benefits of Andropogon gerardii under limited N supply. Ecol. Evol. 2016, 6, 4332–4346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treseder, K.K.; Allen, E.B.; Egerton-Warburton, L.M.; Hart, M.M.; Klironomos, J.N.; Maherali, H.; Tedersoo, L. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi as mediators of ecosystem responses to nitrogen deposition: A trait-based predictive framework. J. Ecol. 2018, 106, 480–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingraffia, R.; Amato, G.; Sosa-Hernández, M.A.; Frenda, A.S.; Rillig, M.C.; Giambalvo, D. N Type and Availability Drive Mycorrhizal Effects on Wheat Performance, N Uptake and Recovery, and Production Sustainability. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, L.; Luo, W.; Hou, Z.; Min, W.; Liu, T. Effects of Nitrification Inhibitors on Nitrous Oxide Emissions, Main Crop Yield and N Use Efficiency in Cropland in China: A Meta-Analysis. Chin. Agric. Sci. Bull. 2024, 40, 107–115. [Google Scholar]

- Naqqash, T.; Hameed, S.; Imran, A.; Hanif, M.K.; Majeed, A.; van Elsas, J.D. Differential Response of Potato Toward Inoculation with Taxonomically Diverse Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacteria. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pilić, S.; Bešta-Gajević, R.; Dahija, S.; Grahić, J. Utjecaj fungicida i biopesticida na morfološke promjene na malini (Rubus ideaus L. „POLKA”) inficiranoj bakterijom Agrobaterium tumefaciens. Poljoprivreda 2023, 29, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marjanović, J.; Zubairu, A.M.; Varga, S.; Turdalieva, S.; Ramos-Diaz, F.; Ujj, A. Demonstrating Agroecological Practices in Potato Production with Conservation Tillage and Pseudomonas spp., Azotobacter spp., Bacillus spp. Bacterial Inoculants—Evidence from Hungary. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawaa, A.; Hichem, H.; Labidi, S.; Ben Jeddi, F.; Mhadhbi, H.; Naceur, D. Influence of biofertilizers on potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) growth and physiological modulations for water and fertilizers managing. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2024, 174, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.; Hu, X.; Liu, X.; Zhang, P.; Yang, S.; Xia, F. Bioorganic Fertilizer Can Improve Potato Yield by Replacing Fertilizer with IsoNous Content to Improve Microbial Community Composition. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paschalidis, K.; Fanourakis, D.; Tsaniklidis, G.; Tsichlas, I.; Tzanakakis, V.A.; Bilias, F.; Samara, E.; Ipsilantis, I.; Grigoriadou, K.; Samartza, I.; et al. DNA Barcoding and Fertilization Strategies in Sideritis syriaca subsp. syriaca, a Local Endemic Plant of Crete with High Medicinal Value. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Commission. Farm to Fork Strategy: For a Fair, Healthy and Environmentally-Friendly Food System; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium. Available online: https://food.ec.europa.eu/horizontal-topics/farm-fork-strategy_en (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- European Commission. The European Green Deal; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Batool, M.; Sarrazin, F.J.; Zhang, X.; Musolff, A.; Nguyen, T.V.; Attinger, S.; Kumar, R. Scenario analysis of N surplus typologies in Europe shows that a 20% fertilizer reduction may fall short of 2030 EU Green Deal goals. Nat. Food 2025, 6, 787–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugelnik, I.; Rebekić, A.; Jelić Milković, S.; Lončarić, R. Stavovi ekoloških proizvođača o ekološkoj poljoprivredi u Republici Hrvatskoj. Poljoprivreda 2024, 30, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y.; Wang, J.; Wei, Z.; Dodla, S.; Fultz, L.; Gaston, L.; Xiao, R.; Park, J.-H.; Scaglia, G. Nitrification inhibitors reduce N losses and improve soil health in a subtropical pastureland. Geoderma 2021, 388, 114947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasile Scăețeanu, G.; Madjar, R.M. The Control of N in Farmlands for Sustainability in Agriculture. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council of the European Union. Council Directive 91/676/EEC of 12 December 1991 Concerning the Protection of Waters Against Pollution Caused by Nitrates from Agricultural Sources. Off. J. Eur. Communities 1991, L 375, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Sustainable N Management in Agrifood Systems; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2025; Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/items/471bc50f-d855-47ff-80d8-361577cbed99 (accessed on 23 November 2025). [CrossRef]

- Action on N Vital for Efforts Across the Sustainable Development Goals. Available online: https://srilanka.un.org/en/126681-action-N-vital-efforts-across-sustainable-development-goals (accessed on 23 November 2025).

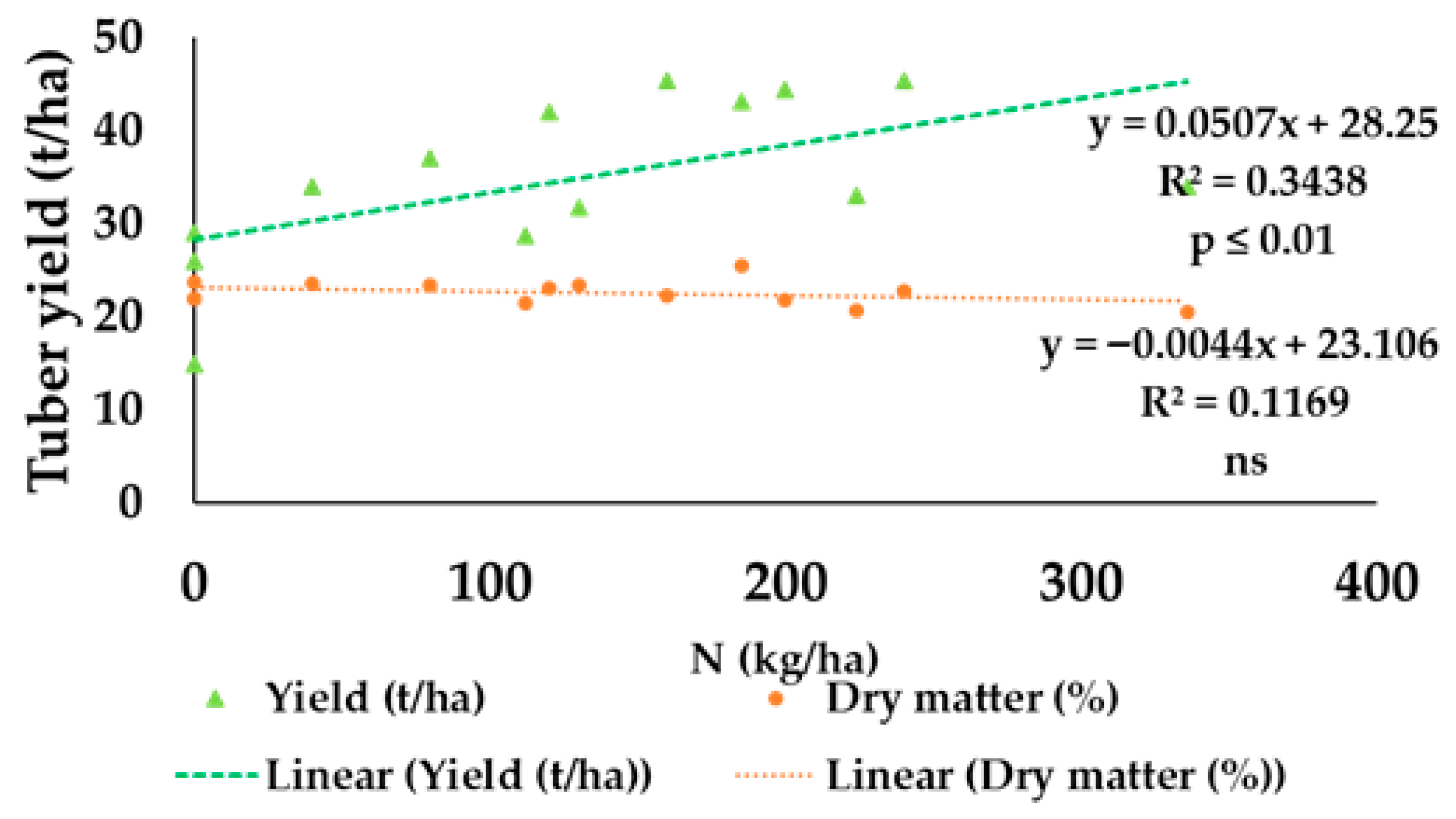

| Location | N Applied (kg/ha) | Tuber Yield (t/ha) | Dry Matter (%) | Strach | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Italy | 0 | 14.3 | – | – | Ierna, Mauromicale [95] |

| 100 | 35.9 | ||||

| 200 | 46.7 | ||||

| 300 | 48.7 | ||||

| 400 | 48.5 | ||||

| Poland | 0 | 16.7 | – | – | Kołodziejczyk et al. [113] |

| 60 | 27.8 | ||||

| 120 | 35.2 | ||||

| 180 | 40.0 | ||||

| Kazahstan | 0 | 27.2 | – | – | Nurmanov et al. [114] |

| 30 | 34.9 | ||||

| 60 | 39.2 | ||||

| 90 | 36.4 | ||||

| Egypt | 160 | 29.68 | – | – | Badr et al. [115] |

| 220 | 37.87 | ||||

| 280 | 43.76 | ||||

| 340 | 47.84 | ||||

| Ethiopia | 0 | 23.8 | Zewide et al. [116] | ||

| 55 | 30.2 | ||||

| 110 | 34.6 | ||||

| 165 | 38.1 | ||||

| USA | 0 | 14.9 | 21.9 | – | Porter et al. [117] |

| 112 | 28.7 | 21.5 | |||

| 224 | 33.0 | 20.6 | |||

| 336 | 34.0 | 20.4 | |||

| China (1) | 0 | 25.91 | 21.97 | 14.62 | Su et al. [118] |

| 130 | 31.65 | 23.39 | 15.89 | ||

| 185 | 43.16 | 25.38 | 17.66 | ||

| 240 | 45.37 | 22.76 | 15.32 | ||

| Canada | 0 | 28.9 | 23.6 | – | Zebarth et al. [119] |

| 40 | 33.9 | 23.5 | |||

| 80 | 37.0 | 23.3 | |||

| Italy (2) | 0 | – | 17.25 | 640 | Lombardo et al. [120] |

| 140 | 16.65 | 635 | |||

| 280 | 16.45 | 581 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Varga, I.; Bešlić, M.; Antunović, M.; Jović, J.; Markulj Kulundžić, A. Optimizing Nitrogen Inputs for High-Yielding and Environmentally Sustainable Potato Systems. Nitrogen 2025, 6, 117. https://doi.org/10.3390/nitrogen6040117

Varga I, Bešlić M, Antunović M, Jović J, Markulj Kulundžić A. Optimizing Nitrogen Inputs for High-Yielding and Environmentally Sustainable Potato Systems. Nitrogen. 2025; 6(4):117. https://doi.org/10.3390/nitrogen6040117

Chicago/Turabian StyleVarga, Ivana, Marina Bešlić, Manda Antunović, Jurica Jović, and Antonela Markulj Kulundžić. 2025. "Optimizing Nitrogen Inputs for High-Yielding and Environmentally Sustainable Potato Systems" Nitrogen 6, no. 4: 117. https://doi.org/10.3390/nitrogen6040117

APA StyleVarga, I., Bešlić, M., Antunović, M., Jović, J., & Markulj Kulundžić, A. (2025). Optimizing Nitrogen Inputs for High-Yielding and Environmentally Sustainable Potato Systems. Nitrogen, 6(4), 117. https://doi.org/10.3390/nitrogen6040117