1. Introduction

As described in [

1,

2,

3], a semi-discrete system (SDS) is a kind of system where spatial independent variable(s) is/are discrete but the temporal independent variable remains continuous. Therefore, an SDS combines some characteristics of discrete systems with certain features of continuous systems. For example, in the lattice model, atoms are discretely distributed in space, while time can be viewed as continuous [

4,

5,

6]. When studying nonlinear issues like wave propagation in discrete lattices, an SDS can accurately characterize the relevant physical processes. Meanwhile, there are some methods for finding solutions for SDSs, such as the Jacobian elliptic function method [

7], the exp-function technique [

8], the double commutation method, and IST [

9]. Nevertheless, compared with continuous systems, solving SDSs is still relatively difficult. These methods are mainly used to solve some semi-discrete NLS equations [

4,

5], the Toda hierarchy [

9,

10,

11], etc. In addition, SDSs have wide applications in digital control systems [

12], signal processing and communication [

13], robotics [

14], etc.

Fractional calculus [

15,

16] is an extension of the concept of integer calculus, making the analysis of functions more refined. Integer calculus can only describe change in a function at integer orders, while fractional calculus can capture the more subtle variation characteristics of functions [

17,

18]. For some functions with fractal properties, integer calculus cannot fully reflect their complex local properties. However, fractional calculus can describe the variation rules of functions at multi-scales through different fractional orders, providing a powerful tool for studying the local singularity and irregularity of functions. Combining fractional calculus with Laplace transform [

16,

19,

20,

21] and/or Fourier transform [

18] expands the application scope and theoretical depth of these transformations. Fractional calculus not only has wide applications in mathematics and physics [

22,

23,

24] but also plays an important role in engineering, such as proportional integral derivative (PID) control [

25], robotics [

26], image processing [

27], and automotive engineering [

28].

However, we know that for integrable partial differential equations, they are not necessarily integrable after being partially discretized. Discrete integrable systems can be studied from different angles. It is known from the book [

5] by Ablowitz, Prinari, and Trubatch that they studied the NLS, integrable discrete NLS (IDNLS), matrix NLS (MNLS), and integrable discrete MNLS (IDMNLS) equations, with the NLS equation remaining integrable after discretization. In 2022, Ablowitz, Been, and Carr [

29] utilized the discrete Fourier transform/Z-transform to obtain the fractional IDNLS (fIDNLS) equation and the fractional averaged NLS (fADNLS) equation after studying the fractional mKdV (fmKdV), fractional sine-Gordon (fsine-G), and fractional sinh-Gordon (fsinh-G) equations [

30] by extending the method of [

15]. This is due to the use of the chosen Riesz fractional-order derivative (RFD) [

15], denoted by

:

which has the Fourier multiplier

for

. The discrete RFD used in this article, namely, the DRF derivative, also has a similar multiplier to RFD, as shown in Equations (13) and (14). Although there are many other fractional-order derivatives [

31], such as the Riemann–Liouville fractional derivative, the Caputo fractional derivative, the Grünwald–Letnikov fractional derivative, etc., this multiplier is not possessed by these nonlocal fractional derivatives. Compared to other nonlocal fractional derivatives, the advantage of RFDs is that they are particularly intuitive and easy to understand for physicists who do not specialize in this mathematical field, and they are an ideal tool for describing isotropic anomalous diffusion. In addition, RFDs have an extremely concise form in the frequency domain, making theoretical analysis and numerical solutions very effective. This is an effective tool for describing the behavior of complex systems due to the close correlation between RFDs and non-Gaussian statistics [

32], as indicated in [

30], and it has physical applications in describing the motion of water in porous media and power law decay in materials. It can be seamlessly extended to high-dimensional space, with an invariant definition, and is suitable for solving fractional-order partial differential equations in space.

The core idea of Ablowitz et al.’s method [

15,

29] includes three elements, one of which is to link a set of integrable nonlinear equations or semi-discrete equations to linear scattering problems to characterize the fractional equation with an RFD or DRF derivative to be solved through a power law DR. The second is to determine the fractional operator corresponding to the DR based on the completeness of the squared eigenfunctions of the relevant scattering equations. The third is to follow the steps of the IST [

33] to obtain the solution of the fractional equation being solved. The method proposed by Ablowitz et al. [

15,

29] is not only suitable for the fractional equations [

15,

29,

30] mentioned above but has also been successfully applied to other models with RFDs, such as fractional higher-order NLS equations [

34] and combined mKdV hierarchy [

35], fractional coupled multi-component NLS models [

36,

37], fractional coupled Hirota and Gerdjikov–Ivanov equations [

38,

39], the fractional derivative NLS equation [

40] and generalized NLS equations [

41], the fractional Fokas–Lenells equation [

42], variable-coefficient fractional KdV and generalized NLS equations [

43,

44], and fractional Toda lattice and hierarchy [

45].

In the complex and diverse real world, many profound natural phenomena and inherent rules can all be precisely depicted through ingenious mathematical physics equations. Variable-coefficient equations [

43,

44] with detailed descriptions of the parameter evolution characteristics in dynamic systems have broken through the limitations of constant-coefficient equations, endowed complex problems with higher descriptive accuracy, and have become powerful tools for revealing the essence of nature. However, proving the existence and solvability of solutions for nonlinear equations with variable coefficients has always been a difficult problem in the field of mathematical physics. Such equations are not only limited by their own nonlinear characteristics in analytical methods but also need to deal with the dynamic effects caused by variable coefficients, which poses a dual challenge that makes the related research much more difficult than that of constant-coefficient equations. The fractional NLS-type equation under the framework of continuous systems has successfully revealed the soliton structure characteristics of fractional integrable models solved by the IST constrained with the dual action [

44] of RFDs and variable coefficients, providing an important reference for research in the related field. However, it is worth noting that up to now, within the framework of IST integrability conditions defined by Ablowitz et al. [

29], there have been no systematic studies on variable-coefficient semi-discrete equations with DRF derivatives reported in the public literature, and this research gap urgently needs to be filled. In view of this, this paper is based on the DRF derivative theory and the variable-coefficient analysis method and is committed to deeply exploring the existence, analytical properties, and soliton structure characteristics of IST integrable Riesz fractional semi-discrete models. This research is not only expected to explore the integrability of the theoretical system of fractional-order nonlinear equations but also provides solid theoretical support and innovative research ideas for solving practical problems in multiple interdisciplinary fields such as nonlinear physics, control engineering, and communication engineering.

This paper introduces the DRF calculus

with

[

46,

47], and in a similar way to that of [

29], to obtain the following vcfISDNLS equation:

where

with

; using the index number,

, as the lattice point or spatial position, the time variable is

, and

and

are real functions of

that are independent of each other. When

, Equation (1) degenerates into Ablowitz et al.’s fIDNLS equation [

29],

. In general, a step size,

, exists in Equation (1). In this paper, we take

without losing generality. To generate Equation (1), we only need to convert

and

into

and

. Given the condition of

, Equation (1) can generate new equations:

In this article, we derive the vcfISDNLS Equation (1) using the DRF order derivative and solve it through the IST. In

Section 2, we derive the vcfISDNLS equation, Equation (1), by using the DR. In

Section 3, we first obtain the Jost functions and summation equations and prove their existence and analytical properties. Secondly, we obtain scattering data and normal constants and prove the symmetry of the solution. In

Section 4, we first introduce the boundary conditions and residues, and then, we consider two cases of no poles and poles. Finally, we obtain reflectionless potentials, the Gel’fand–Levitan–Marchenko (GLM) equation, and time evolution. In

Section 5, when

, we determine the one-, three-, and three-soliton solutions and conduct nonlinear dynamic analysis on them. In the final section, we present the corresponding conclusions and opinions and point out the shortcomings and their implications for engineering applications.

2. Derivation of the vcfISDNLS Equation

In order to obtain Equation (1), we first consider the discrete problem:

When

, we rewrite Equation (3) as

and introduce the following time-dependent equation:

Then, the compatibility condition of Equations (4) and (5) is equivalent to Equation (2).

However, obtaining Equation (2) is not the starting point of this article but rather draws inspiration from it and derives Equation (1). For this, we need to find the DR corresponding to Equation (1). Before that, we introduce the following nonlinear evolution equation:

The operator,

, introduced here consists of two factors, and in fact, it is necessary to divide this operator into two factors. The first factor is composed of

. When applying the second factor, we introduce operator

and the inverse operator, which is

. Note that operator

satisfies [

29]

and the inverse operator,

, satisfies [

29]

where

,

, and

with

, providing the definition of

, which satisfies

Specifically, when

is a fully regular function, it is related to the linearized DR, and then, we can solve Equation (1) by using the IST. For Equation (1), we can determine the corresponding operator,

, with a fractional power:

In fact, by utilizing the method of [

29], we let

and determine the linear part of Equation (6):

In this paper, the DRF derivative of

is defined by

Then, the DR,

, corresponding to Equation (11), is obtained as

In addition, the operator,

, can be directly related to the DR,

. As described by

, the linear part of Equation (6) can be obtained:

Further substituting

into Equation (15), we obtain

By comparing Equations (14) and (16), we conclude that

Using Equations (11) and (14), we ultimately obtain Equation (10), thus proving the existence of Equation (1).

5. Soliton Solutions

In the case where the scattering data comprise proper eigenvalues but

on

, the algebraic–integral system, (104)–(107), reduces to the linear algebraic system. Moreover, the potentials are given by

When

, the eigenvalues are

, where

with

and

; then, we can solve for

and

, obtaining, in particular,

where we introduce the modified normalization constants

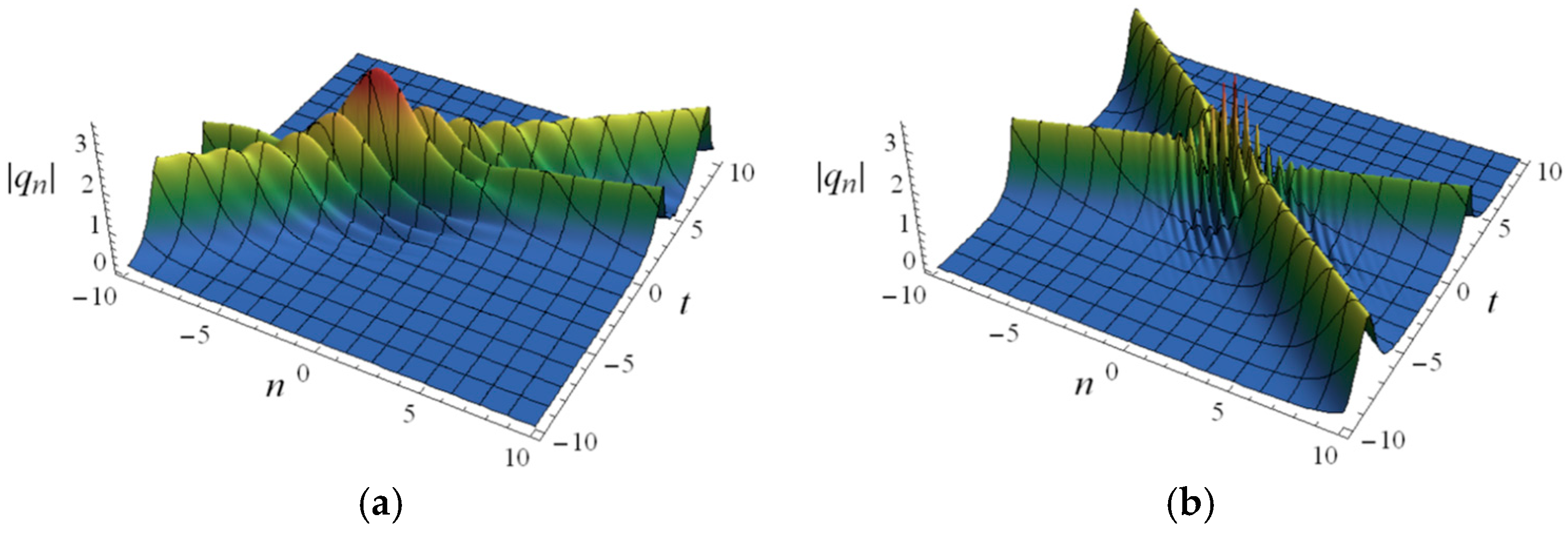

We simulate the spatiotemporal structures of the semi-discrete one-soliton solutions, (151) and (152), in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 by taking different DRF orders,

,

, and

, where

,

,

, and

,

. It can be seen that the bell-solitons formed by solutions (151) and (152) propagate in the positive direction of the

n-axis and have very similar shapes on the

n-axis, and the amplitudes

and

of these bell-solitons are not significantly different. When other parameters remain unchanged and the value of

changes from −0.1 to 0 and then to 0.1, we find that the shape of the bell-soliton remains unchanged, but the angle between the trajectory of the bell-soliton on the coordinate plane and the

n-axis decreases, indicating that the distance traveled by the soliton per unit time increases; that is, the velocity increases.

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 illustrate that the value of fractional order,

, has no significant effect on the shape and amplitude of a soliton but has a visible impact on the soliton velocity (only in terms of quantity rather than direction).

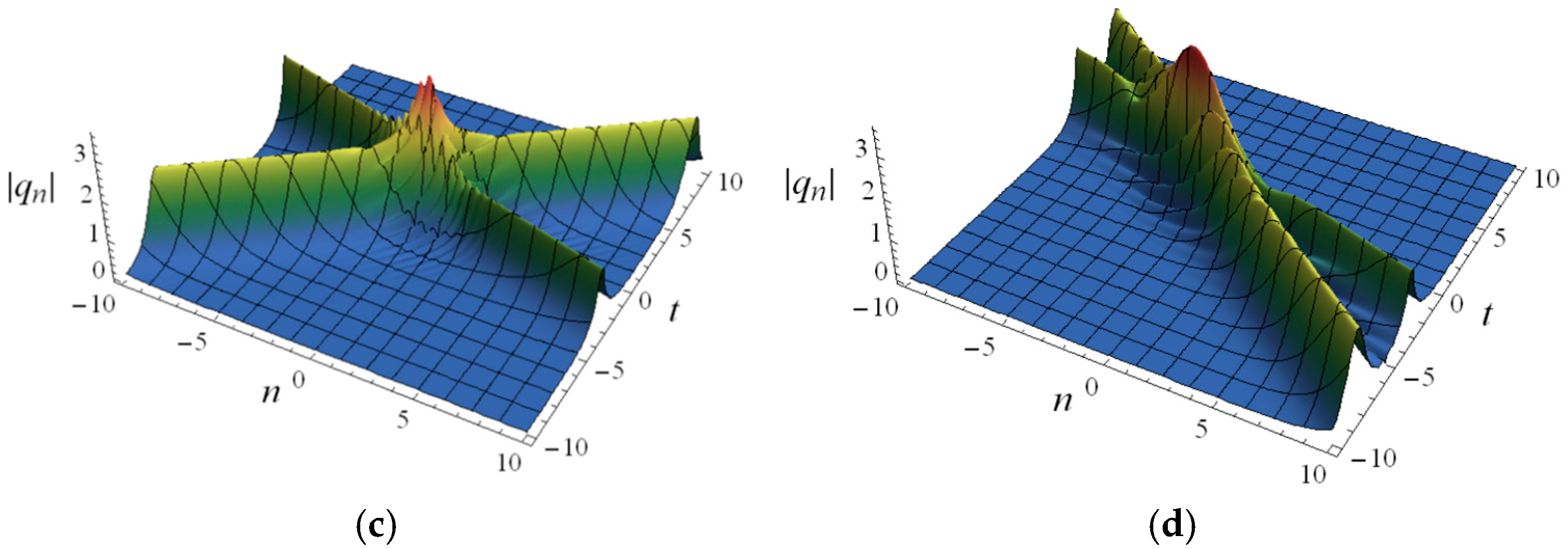

Figure 3 shows that although the coefficients

and

do not have a significant effect on the shape and amplitude of the soliton, they can affect the soliton velocity in both quantity and direction. As a result, the soliton forms a curved plane trajectory, which is completely different from the straight plane trajectory formed when

and

are constants (see

Figure 1 and

Figure 2). In the case where

is zero,

Figure 4 shows that

and

, with time, become factors that constrain soliton velocity, resulting in the formation of rich curved plane trajectory curves, some of which may also have periodicity.

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 indicate that

,

, and

can jointly control the velocity of the solitons together, including the quantity and direction of velocity, but changing them will not result in energy loss or diffusion of soliton propagation.

In fact, when the eigenvalues satisfy (i) the relation

, (ii) the product of the normalization constants

and

are complex numbers, and (iii) the exponential forms

with

; thus, the solutions, (163) and (164), can be rewritten in the forms

Then, the velocity of the solitons formed by Equations (167) and (168) can be expressed mathematically as

This theoretically elucidates the dual effects on the velocity of solitons from the coefficients and and the fractional order, . Meanwhile, we can also see from Equations (167) and (168) that the amplitude of solitons is theoretically unaffected by the choice of , , and .

When

, the eigenvalues are

, where

,

with

,

and

,

; then, we can solve for

and

, obtaining, in particular,

where we introduced the modified normalization constants,

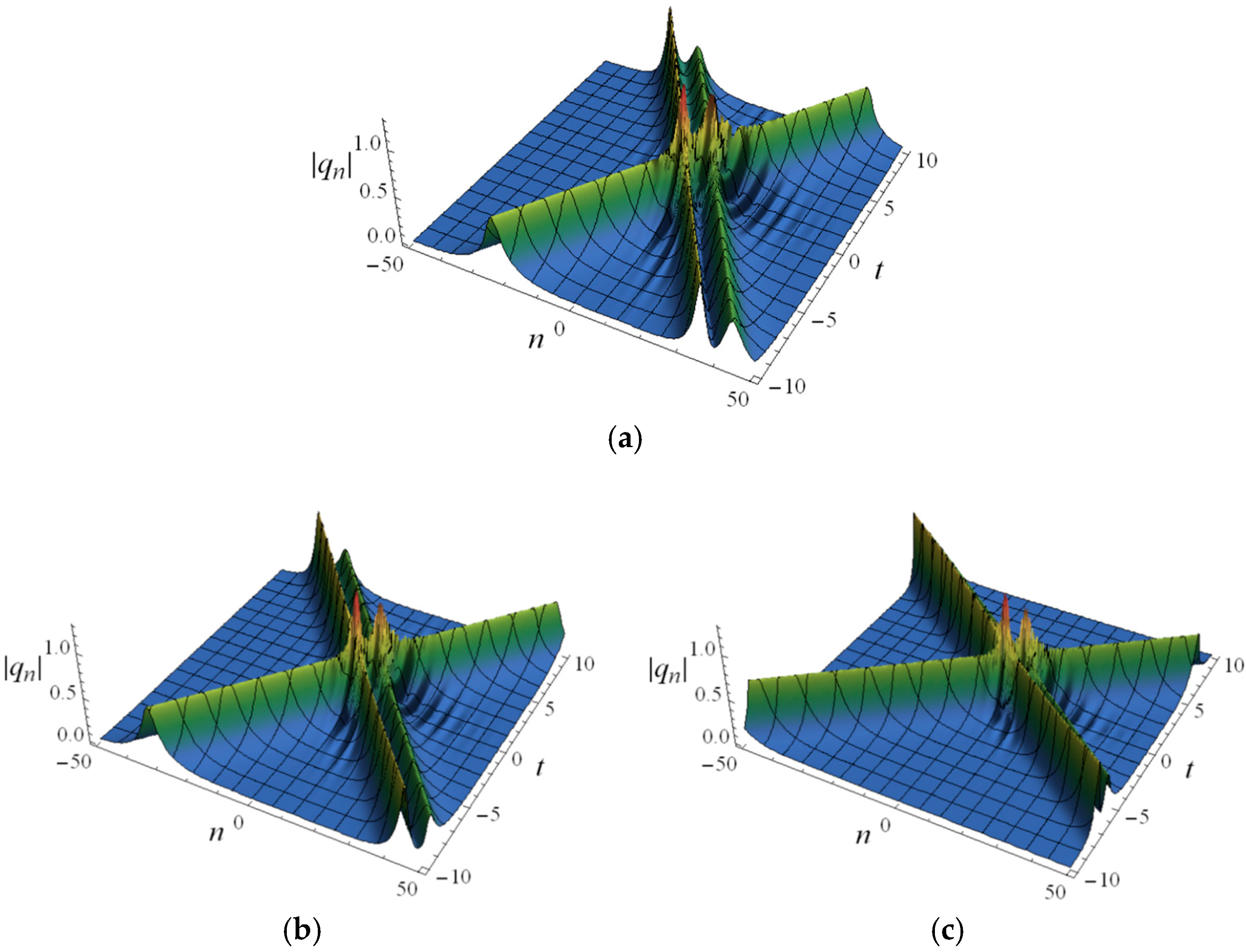

In

Figure 5, the spatiotemporal structures of the semi-discrete two-soliton (172) are shown, and we can see that two types of waves propagate in both positive and negative directions, forming an X-shape. By changing

from 0 to 0.1 and then to 0.3, the distance between the two solitons increases sequentially, but there is no significant difference in soliton amplitude.

Figure 6 indicates that without considering the variation in

, a clear characteristic of soliton propagation is that two seemingly stationary solitons collide and travel opposite to each other with a sharp increase in velocity. This tells us that the coefficient,

, has a decisive impact on the soliton velocity.

In

Figure 7, we specifically set

, and we can see that the two solitons propagate in both positive and negative directions, as shown in

Figure 5 and

Figure 6, forming an X-shape. We can clearly see that when the sign of the imaginary part of

z changes, the direction of the velocity also changes. If the imaginary parts of two solitons have the same sign, the propagation direction is the same; when the imaginary parts have different signs, the propagation direction is opposite, and the amplitudes of the two solitons are also different. Furthermore, it is clear that the two solitons completely penetrate each other, and there is no loss or diffusion during the propagation process.

When

, the eigenvalues are

, where

,

,

with

,

,

and

,

,

; then, we can solve for

and

, obtaining, in particular,

where we introduce the modified normalization constants,

In

Figure 8, we show the spatiotemporal structures of the semi-discrete three-soliton solution (178). We range the fractional order,

, from 0 to 0.1 and then to 0.3, where the directions of the three solitons are different. Two of them travel along the positive

n-axis, but the third one travels in the opposite direction.

Figure 8 shows that the three solitons penetrate each other after interaction without diffusion or loss, and the larger the value of

, the greater the distance between solitons moving in opposite directions.

6. Conclusions

We derived the vcfISDNLS equation, Equation (1), based on the DRF derivative and studied its integrability within the IST framework. As a result, we derived the

-soliton solution of the vcfISDNLS equation, Equation (1), with a focus on analyzing the one-soliton solutions, (163) and (164) or (176) and (168); two-soliton solutions, (172) and (173); and three-soliton solutions, (178) and (179). Equation (1) is first proposed in this article, and there are no other results besides our research here. Due to the coupling of variable coefficients

and

; the fractional order,

; and the discrete variable,

, in the obtained solutions, (163), (164), (172), (173), (176), and (178), it is difficult to directly substitute them back into Equation (1) to verify their correctness. As for the validity of these solutions, we only verified them with the help of computers in the case of

. The verification of single-soliton solutions for continuous Riesz fractional KdV and NLS equations has been achieved based on their explicit representations, as shown in [

15]. In order to demonstrate the completeness of the derivation and calculations, some necessary results from [

5] have been referenced and used in this article. Due to the presence of coefficient functions

and

in Equation (1), it is important to distinguish between the conclusions cited in [

5], which imply different development patterns related to time as used in the present work. As for the shortcomings of the research work, we would like to mention that we have not yet obtained the display of a Lax pair associated with Equation (1). In this work, the integrability of Equation (1) is limited to the meaning of inverse scattering solvability through Ablowitz et al.’s method [

29], but its integrability cannot be verified under the traditional Lax integrability framework. This point was first emphasized by Ablowitz et al. in [

15]. It should be made clear here that for higher-order soliton solutions in the case

, they can be derived by substituting Equations (104)–(107) into Equations (163) and (164). However, given the sufficient complexity of expressions (176) and (177) for the three-soliton solutions, (163) and (164), this article does not specifically elaborate on the derivation of such higher-order soliton solutions. For this reason, it should be noted that this article only considers a few situations. When we take other values for the DRF order,

, we find that the image is sometimes chaotic or exhibits singularity. Therefore, this article does not provide images of solutions corresponding to other values of DRF order

.

Regarding the research conclusions, we particularly point out the following four points: (1) The DRF order,

, does not change the overall spatial structures of the soliton, and its structure is mainly influenced by

and

. (2) The velocity of the soliton is also affected by not only coefficients

and

but also fractional order

when

and

are fixed; the velocity of the one-soliton, two-soliton, and three-soliton increases with the increase in

. (3) Whether it is a 1one-soliton, two-soliton, or three-soliton, their amplitudes are not affected by

,

, and

, which means that the soliton propagation process will not experience amplitude increase or attenuation except for the interaction process. (4) When

, the characteristics of the three-soliton solution (178) are similar to those of the vcRfgNLS equation [

32], indicating that the “continuous” system and the “discrete” system are just as concluded at the beginning of the article.

The vcfISDNLS equation, Equation (1), plays a vital role in the nonlinear field: (i) The vcfISDNLS equation, Equation (1), can be used to describe the propagation of optical pulses in optical fibers. Optical solitons reduce signal attenuation and distortion and improve communication capacity and quality. (ii) The vcfISDNLS equation, Equation (1), can describe the interactions between atoms and the spatial distribution and evolution of Bose–Einstein condensates. (iii) The vcfISDNLS equation, Equation (1), can be used to describe nonlinear wave phenomena in plasmas, such as Langmuir waves, ion acoustic waves, etc. (iv) The successful derivation of the vcfISDNLS equation, Equation (1), through DRF calculations provides a theoretical basis for other SDS equations, which can also be derived and solved using the same method. (v) In automotive suspension systems, the system structure can be optimized to reduce unnecessary vibration reflections, minimize fatigue damage to mechanical components, and improve system stability and lifespan. Given that semi-discrete solitons can maintain stability from chaotic/singular states by considering the dual influence factors of DRF order and coefficient functions, it is expected that such a control mechanism can provide assistance for optimizing automotive suspension systems. However, the application of this control mechanism in practical engineering still needs to be explored. (vi) The nonlinear property of the vcfISDNLS equation, Equation (1), implies that the inclusion of nonlinear components is helpful in designing nonlinear circuits that can generate stable oscillation or pulse signals, which are applied in signal generators, oscillators, and other devices to provide high-quality signal sources for electronic devices. Furthermore, due to the particularity of DRF calculus, we did not utilize or find the explicit form of a Lax pair corresponding to the vcfISDNLS equation, Equation (1), but instead found that the asymptotic forms consist of Equations (18) and (130), which match the explicit Lax pair, which is not contradictory to the statement in [

33]. In addition, for Equation (1), we need to analyze its existence and stability, but the stability is not discussed theoretically here. This is both the weakness of our work and the unsolved problem in the study of such Riesz fractional-integrable systems. At the same time, we believe that Equation (1) still has a lot to learn from a scientific and engineering perspective. This is because the semi-discrete NLS equation has practical applications in optics (all-optical switches), electronic engineering (nonlinear transmission pulse sources), and acoustic engineering (topological phononic crystals).