1. Introduction

We consider the following nonlinear fourth-order time fractional diffusion equations.

Problem 1. Find satisfyingin which is a bounded domain and has a smooth boundary ; , is a given initial function. Where κ is the diffusion mobility constant, ε is a positive constant. The function satisfies and the Lipschitz conditionwhere is a constant. represents the Caputo fractional derivative with defined bywhere is the Gamma function. Throughout this work, C is defined as a positive constant that could take different values at different places. Diffusion is a fundamental physical process for mass and energy transport. Its classical description relies on Fick’s law, which leads to an integer-order diffusion equation [

1]. However, numerous experiments have revealed non-classical phenomena in diffusion processes, such as slow diffusion and long-term memory effects. These observations have motivated the development of time-fractional diffusion equations, with applications to seepage in porous media [

2], anomalous transport [

3], and bioengineering [

4]. By replacing the first-order time derivative with Caputo, Gr

nwald−Letnikov or Riemann−Liouville fractional derivatives, these models provide a more precise mathematical framework for anomalous diffusion [

5,

6]. Despite the advantages of time-fractional models for physical modeling, their analytical solutions typically involve complex Mittag–Leffler functions [

7], which hinders practical application. Thus, the development of efficient numerical methods is essential. For spatial discretization, common techniques include finite difference [

8], Galerkin finite element [

9], weak Galerkin finite element [

10], discontinuous Galerkin [

11], and spectral methods [

12]. However, when these numerical methods solve directly for the primary variable (e.g., concentration or temperature), their approximations for the corresponding flux (e.g., mass or heat flux) are typically of low order. In contrast, the mixed finite element method (MFE) introduces the flux as an independent variable, yielding a coupled system that simultaneously approximates both the primary variable and the flux field with high precision [

13,

14]. This characteristic gives it a significant advantage in fields where high-precision approximation of the flux field is essential, such as groundwater flow simulation [

15] and composite material mechanics [

16]. The non-local nature of time-fractional derivatives poses severe challenges for computation and storage. For the temporal discretization of such problems, the Crank–Nicolson (CN) scheme is widely adopted because of its unconditional stability and accuracy [

17,

18,

19]. In practice, the CN scheme is often combined with the

formula. This approach effectively handles the historical memory term while preserving numerical accuracy [

20,

21]. Nevertheless, the high degrees of freedom in MFE methods, combined with the full-history dependence of fractional operators, leads to high computational costs. This limits the practicality of high-accuracy CN mixed finite element schemes for problems requiring multiple simulations.

To overcome this bottleneck, model reduction techniques are considered effective. Among them, the Proper Orthogonal Decomposition (POD) method is one of the most prominent spatial reduction techniques [

22,

23]. Its core idea is to extract solutions from the full-order model at specific parameters or time instances (known as “snapshots”) to construct an optimal orthogonal basis. A reduced-order model is then built by projecting the original system onto the low-dimensional subspace spanned by this POD basis. This method has been successfully applied to various partial differential equations, including parabolic equations [

24] and two-dimensional Sobolev equations [

25,

26]. However, the traditional spatial dimensionality reduction method has certain limitations. The global basis functions it generates are highly dependent on the initial and boundary conditions of the problem. When these parameters change, the precomputed POD basis may become ineffective, necessitating the regeneration of snapshots and the reconstruction of new basis functions. This process is not only computationally expensive but also lacks clear criteria for updating the basis, which limits its flexibility in tackling complex problems. To circumvent this, Luo et al. proposed a novel approach where the POD method is applied directly to the solution coefficient vectors obtained from finite element discretization, rather than to the physical function space. This method is called reduced-order extrapolated Crank–Nicolson mixed finite element (ROECNMFE). This significantly improves computational efficiency and has been successfully applied to Sobolev equations [

27], Stokes equations [

28], and hyperbolic equations [

29]. In recent years, this method has also been used to solve fractional partial differential equations [

30,

31,

32].

In this work, the solution coefficient vector dimensionality reduction technique is applied to the fourth-order nonlinear diffusion equations with temporal fractional derivative for the first time. The core innovation lies in the integration of a high-precision CNMFE model with a solution coefficient vector dimensionality reduction technique. The main contributions of this work are threefold:

1. We construct a CNMFE scheme for the time-fractional diffusion equation. This scheme is designed to achieve high-order accuracy in both temporal and spatial discretizations, enabling the simultaneous and high-precision approximation of the primary variable and its associated flux variable.

2. To address the significant computational cost of the high-fidelity CNMFE model, we introduce a ROECNMFE method that acts directly on the solution coefficient vectors. By constructing an optimal POD basis from a set of snapshot solutions obtained from the full-order finite element model, we establish a reduced-order model that dramatically improves computational efficiency while maintaining satisfactory accuracy.

3. The designed numerical examples serve to verify the correctness of both schemes and the superior efficiency of the ROECNMFE model.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 is devoted to formulating the CNMFE scheme for the time-fractional diffusion equation, followed by a rigorous analysis of its stability and a priori error estimates.

Section 3 elaborates on the detailed construction process of the ROECNMFE model based on the coefficient vector reduction technique. This section also provides a theoretical analysis of the stability and error estimates.

Section 4 verifies the effectiveness and advantages of the proposed method through a series of numerical experiments. Finally,

Section 5 concludes the paper with a summary of our findings and a discussion on potential future research directions.

2. The CNMFE Method for the Diffusion Equation

First, introduce an intermediate variable . Thereby, a system of second-order coupled equations is obtained.

Problem 2. Find satisfies The Sobolev space and their norms in this article are classical [

33,

34]. The space of square-integrable functions on

, denoted by

, is defined as

It is a Hilbert space equipped with the inner product

which induces the norm

Let . Then the variational form for equations as follows:

Problem 3. For , find that satisfies The time interval

is partitioned as:

, where

N is a positive integer. For convenience, we introduce some symbols

Then, we consider the discretization for the Caputo fractional derivative of

[

35]

where

[

35] is the truncation error, and

At

, (

5) can be reformulated into the following form:

Furthermore, the equivalent weak form of (

5) is obtained as follows:

Let

be the quasi-uniform triangulation of

,

h denote the spatial grid size. Then the

M-dimensional finite element subspace can be defined as follows:

where

denotes the space of polynomials with no more than

degrees on

, and

forms a set of orthonormal bases under the inner product in

. To ensure the subsequent error estimates are valid, we make the following regularity assumption on the exact solution

. This implies that the solution has sufficient smoothness in both time and space. We introduce the Ritz projection operator

, which satisfies

and the operator satisfies the following inequality [

36]:

Using the subspace , we can build the CNMFE scheme as follows:

Problem 4. Find that satisfieswhere the finite element space , defined in (11), is a standard Lagrange finite element space consisting of continuous piecewise polynomials. Both the solution u and the auxiliary variable v are approximated in this same space. Lemma 1 ([

35]).

For the coefficients of (7), it holds that Lemma 2 ((Discrete Fractional

Inequality) [

17]).

Suppose that the nonnegative sequence and satisfieswhere is well defined in (7), and are constants independent of τ. Especially, we let when . There exist positive constant , when ,where and is the Mittag–Leffler function. Theorem 1. The mixed finite element solution is unconditionally stable.

Proof. We let

at (

14)

The sum of the above two formulas is obtained

Using the definition of

and Lemma 1, the first term on the left side of the equation can be treated as

Substitute it into (

19), using Cauchy inequality and

Further organizing the above equation and applying lemma 2, we obtain

Combining the above two formulas, the following is obtained:

The above results prove that solution is unconditionally stable. □

Theorem 2. Let be solutions of (9) and (14) respectively. The following estimator is satisfied Proof. First give some symbols

Then, using the above relationship, from Equations (

9) and (

14), we can obtain

Take

in (

26). Obtain two equations and add them

Similar to (

20), we have

. Then, by using the Cauchy inequality, the above equation can be organized as

Using (

13), we obtain the estimation of the first term on the right

Therefore, (

28) can be concluded

By using Lemma 2, we obtain

The above results, combined with (

28), yield the following error estimation

□

Let . By using the orthonormal basis , we can obtain the matrix model for Problem 4.

Problem 5. Find that satisfieswhere . And we can find that is a positive definite symmetric matrix. To demonstrate the stability of the solution obtained by CNMFE scheme, we introduce a properties of from Problem 5. Lemma 3. Matrix satisfies the following inequality [34,37] 4. The Numerical Examples for the Diffusion Equation

Solve the following system of equations: find

satisfy

The ROECNMFE solutions can be solved in the following four steps.

Step 1. Calculate out two sets of initial CNMFE solution coefficient vectors by Problem 5. Here, the nonlinear system at each time step is solved using the Newton-Raphson iterative method. These vectors are used to compose two snapshot matrices , when (in different calculation examples, parameters can be changed).

Step 2. By using the technique in

Section 3.1, calculate four sets of non-negative eigenvalues

and the corresponding four sets of orthonormal eigenvectors

for matrices

.

Step 3. By estimating, we come to the conclusion that . Thereupon, with two sets of formulas and the eigenvector of ). We obtain four POD bases .

Step 4. By substituting into Problem 6, we calculate the ROECNMFE solutions.

According to the above calculation steps, we designed two sets of experiments with parameters and . The key findings are summarized as follows:

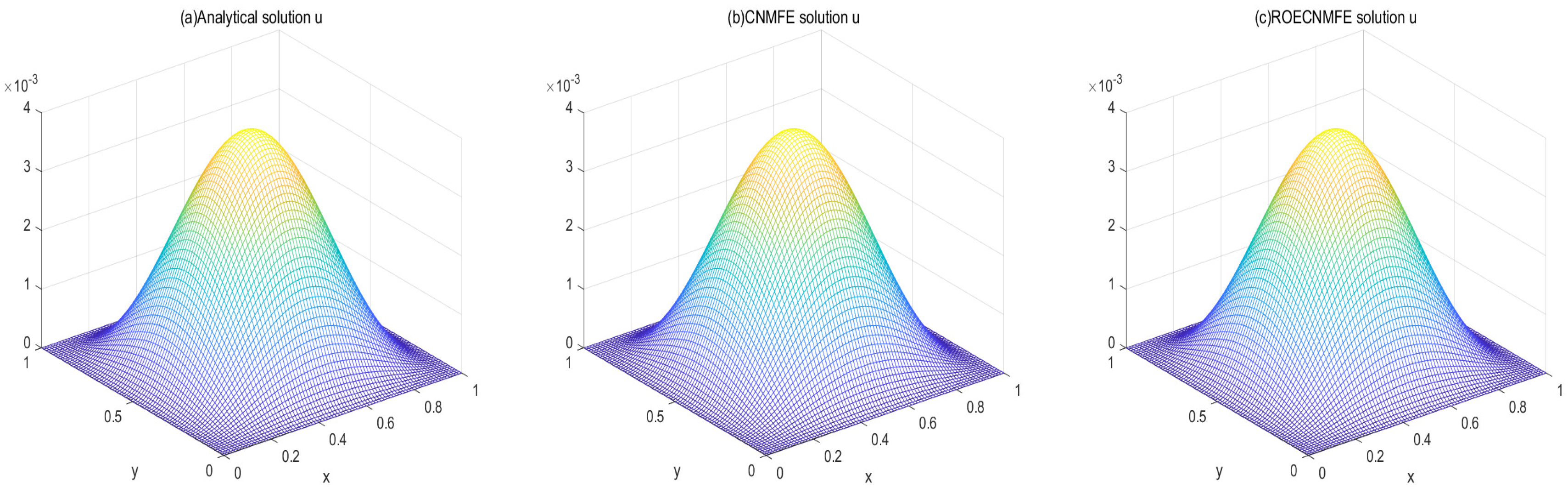

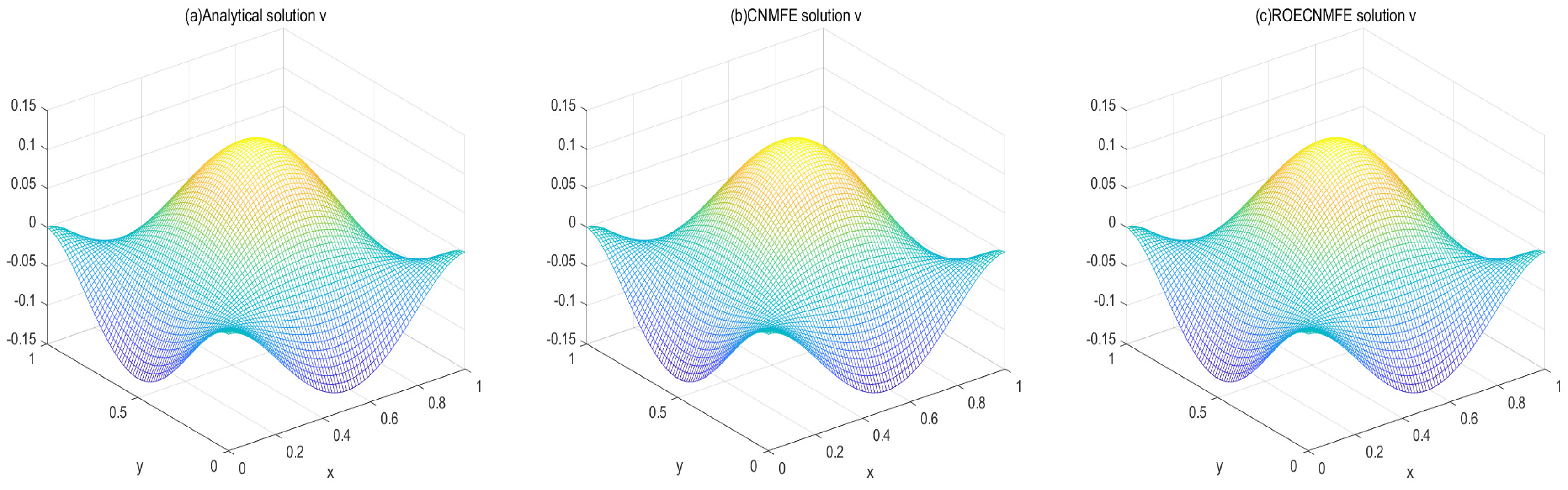

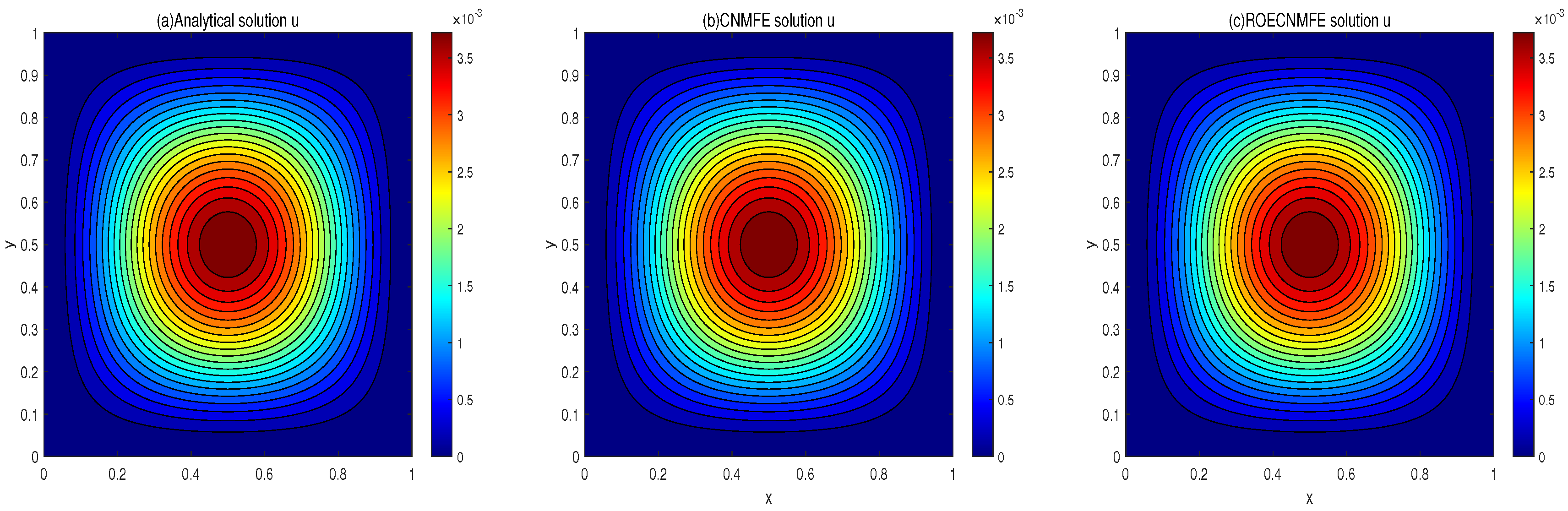

(i) Surface and contour plots at compare the analytical solution with the CNMFE and ROECNMFE solutions for u and v. The three sets of results are visually nearly identical.

(ii) The errors and convergence orders for both variables were computed under different and .

(iii) Under the same experimental setup, the CPU time of the ROECNMFE method is only about of that required by the CNMFE method, highlighting the significant computational advantage of the reduced-order approach.

Example 1. Consider the source term . , , with parameters κ = 1 and ε = 1, 0.1, 0.01. The computational domain is discretized using spatial step size and temporal step size .

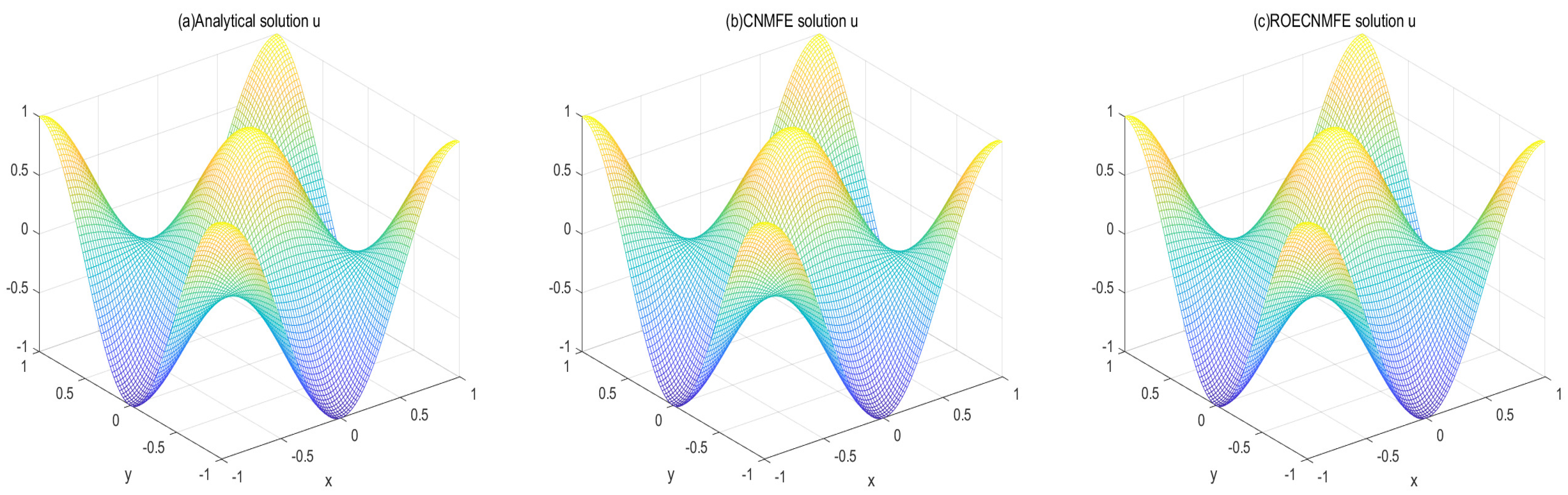

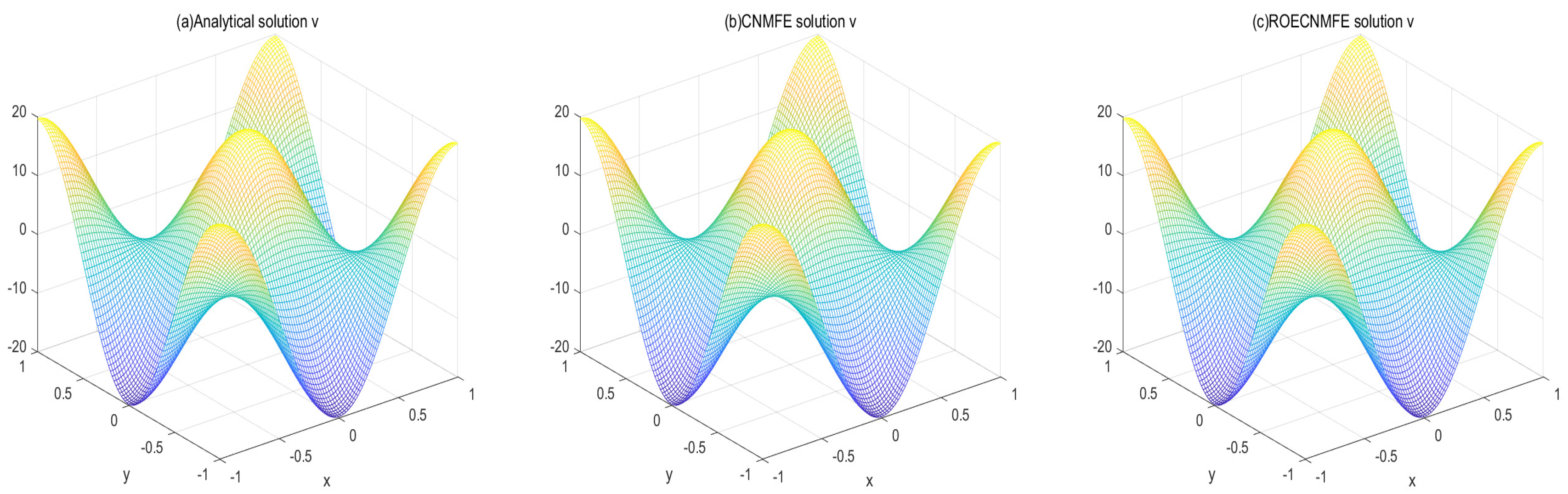

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 compare the analytical, CNMFE, and ROECNMFE solutions for variables

u and

v at

, respectively. The three solutions in each figure show close visual agreement. Similarly,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 present contour plots of the same solutions at

, where the contour distributions are nearly identical across all three methods. These comparisons preliminarily demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed scheme in solving the time-fractional fourth-order nonlinear diffusion equation. To further quantify the accuracy, we conducted two sets of experiments: (i) with

fixed and

. (ii) with

fixed and

. In each case, the

errors and convergence orders were computed for both the CNMFE and ROECNMFE solutions against the analytical solution.

Table 1,

Table 2,

Table 3 and

Table 4 present the numerical errors and convergence orders under successive spatial refinement (

) and a fixed time step

. The results indicate that for different fractional orders

, both the CNMFE and ROECNMFE schemes yield nearly identical error estimates for the variables

u and

v, and consistently achieve second-order convergence—in full agreement with theoretical predictions. It is also observed that smaller values of

lead to smaller numerical errors. To further assess computational performance, we compare the CPU runtimes of the CNMFE and ROECNMFE methods.

Theoretically, at each time level, the CNMFE method requires solving for

unknowns, whereas the ROECNMFE method only needs to dolve for

unknowns. As a result, the ROECNMFE method is expected to have a significantly shorter CPU runtime. To validate this theoretical expectation, we compared the computation times of both methods on the same computer.

Table 5 presents the CPU running time when the spatial step is

and the time step is

and

. The data unequivocally show that under identical conditions, the ROECNMFE method is faster than the CNMFE method, with a speed-up factor ranging from approximately 40 to 104 times across different time points. These findings highlight the considerable advantage of the ROECNMFE method in drastically reducing computational time.

Example 2. Consider the source term , , , , with parameters κ = 1 and ε = 1, 0.1, 0.01. The computational domain is discretized using spatial step size and temporal step size .

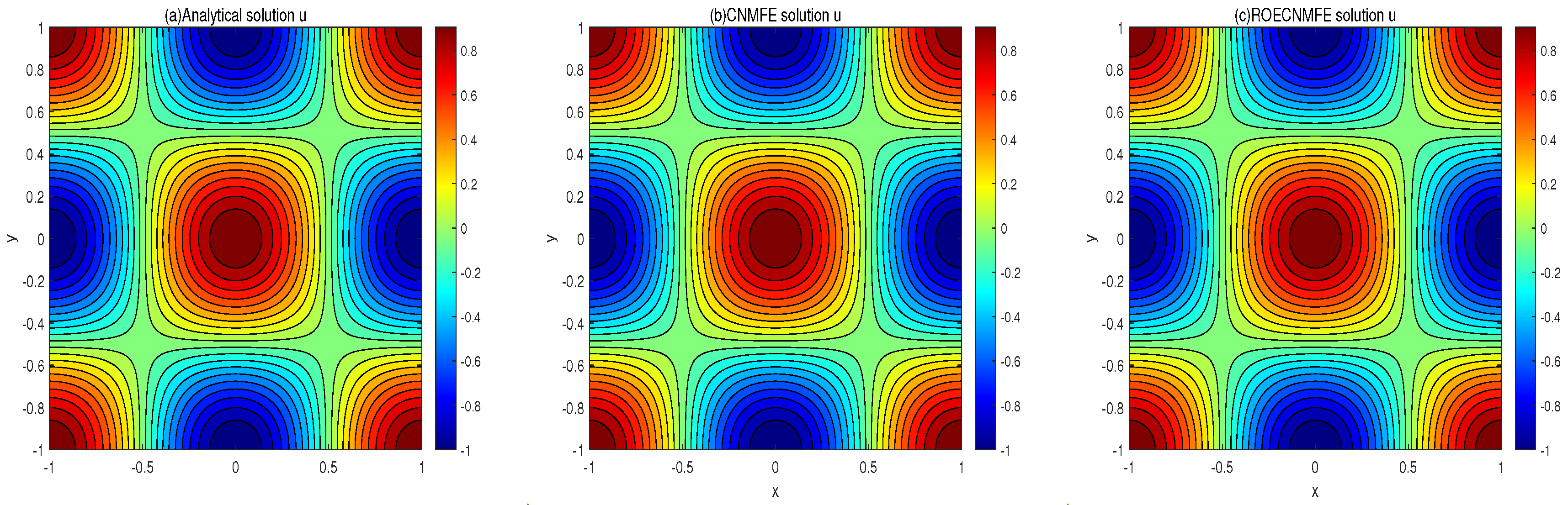

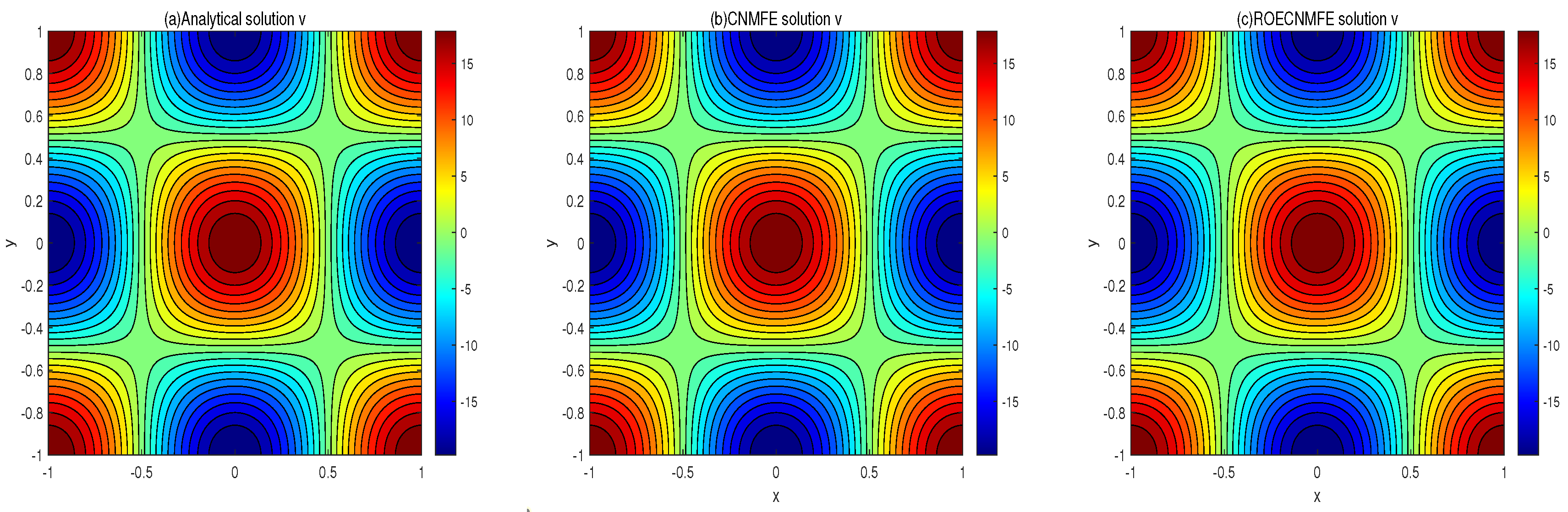

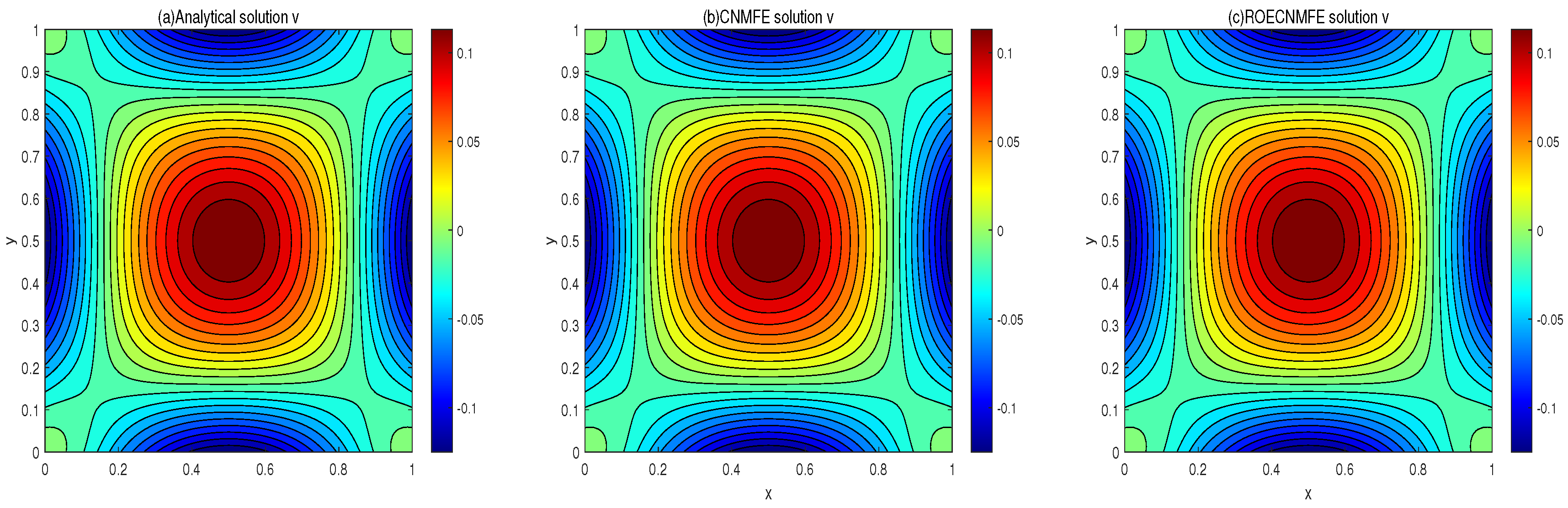

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 compare the analytical, CNMFE, and ROECNMFE solutions for variables

u and

v at

, respectively. The three solutions in each figure show close visual agreement. Similarly,

Figure 7 and

Figure 8 present contour plots of the same solutions at

, where the contour distributions are nearly identical across all three methods. These comparisons preliminarily demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed scheme in solving the time-fractional fourth-order nonlinear diffusion equation. To further quantify the accuracy, we conducted two sets of experiments: (i) with

fixed and

; (ii) with

fixed and

. In each case, the

errors and convergence orders were computed for both the CNMFE and ROECNMFE solutions against the analytical solution.

Table 6,

Table 7,

Table 8 and

Table 9 present the numerical errors and convergence orders under successive spatial refinement (

) and a fixed time step

. The results indicate that for different fractional orders

, both the CNMFE and ROECNMFE schemes yield nearly identical error estimates for the variables

u and

v, and consistently achieve second-order convergence in full agreement with theoretical predictions. It is also observed that smaller values of

lead to smaller numerical errors. To further assess computational performance, we compare the CPU runtimes of the CNMFE and ROECNMFE methods.

Theoretically, at each time level, the CNMFE method requires solving for

unknowns, whereas the ROECNMFE method only needs to solve for

unknowns. As a result, the ROECNMFE method is expected to have a significantly shorter CPU runtime. To validate this theoretical expectation, we compared the computation times of both methods on the same computer.

Table 10 presents the CPU running time when the spatial step is

and the time step is

and

. The data unequivocally show that under identical conditions, the ROECNMFE method is faster than the CNMFE method, with a speed-up factor ranging from approximately 50 times across different time points. These findings highlight the considerable advantage of the ROECNMFE method in drastically reducing computational time.