1. Introduction

Urban scholars can benefit from the recapitulation of human ecology to understand how it has shaped public policies and the built environment. More specifically, how this way of thinking has affected the metamorphoses of neighborhoods over time. The ideas of ecological order within cities provide critical insights into modern presumptions within urban studies. The analyses of human ecologists delve into ethnic and racial conflicts. They also shaped segregation and processes of assimilation.

Although not clearly stated by the urban ecologists, this article argues that the theories underlying their conceptions of urban development take similar assumptions proposed by economists. As one such example, at the forefront of their analysis lie the western notions of personal responsibility. Social ills are taken to be the manifestations of psychological problems, such as depravity and immorality. Historical considerations and circumstances are left aside. Systemic problems, at the core of their assumptions, are depicted as the problems of individuals.

To the degree that sociology is recognizable in the works of the ecologists, the field is taken to be the study of agglomerations of individuals. When these individuals interact, they are capable of improving or corrupting one another toward or away from an assumed ideal type which is intimated but never fully articulated. Within this framework, groups abstain from the harmful consequences of these “social” interactions. They do so, on the one hand, by barricading themselves against the forces of corruption in (white) suburbs. On the other hand, by fleeing from invading corruptors (any grouping of people with a complexion darker than white) while their former neighborhood succumbs to the immanent desolation and decay caused by disinvestment. In this manner, neighborhoods once thought of as prosperous are easily reducible to the rationalized imaginary of blighted inner-city slum and displacement. As a result, slum clearance becomes an imminent, looming threat for those caught up in it.

Along these lines, this article makes two important theoretical contributions: (1) It illustrates the way the positivist theories of Park, Burgess, Hoyt, and others functioned and influenced policy and theoretical conceptualizations (e.g., redlining, lending practices, tipping point etc.) and, (2) it critiques the failing of these models in acknowledging the structural racism embedded in the US housing market and land use policies.

2. Human Ecology

The Chicago School of Urban Sociology interested itself in the positive prescriptions of the nature of cities [

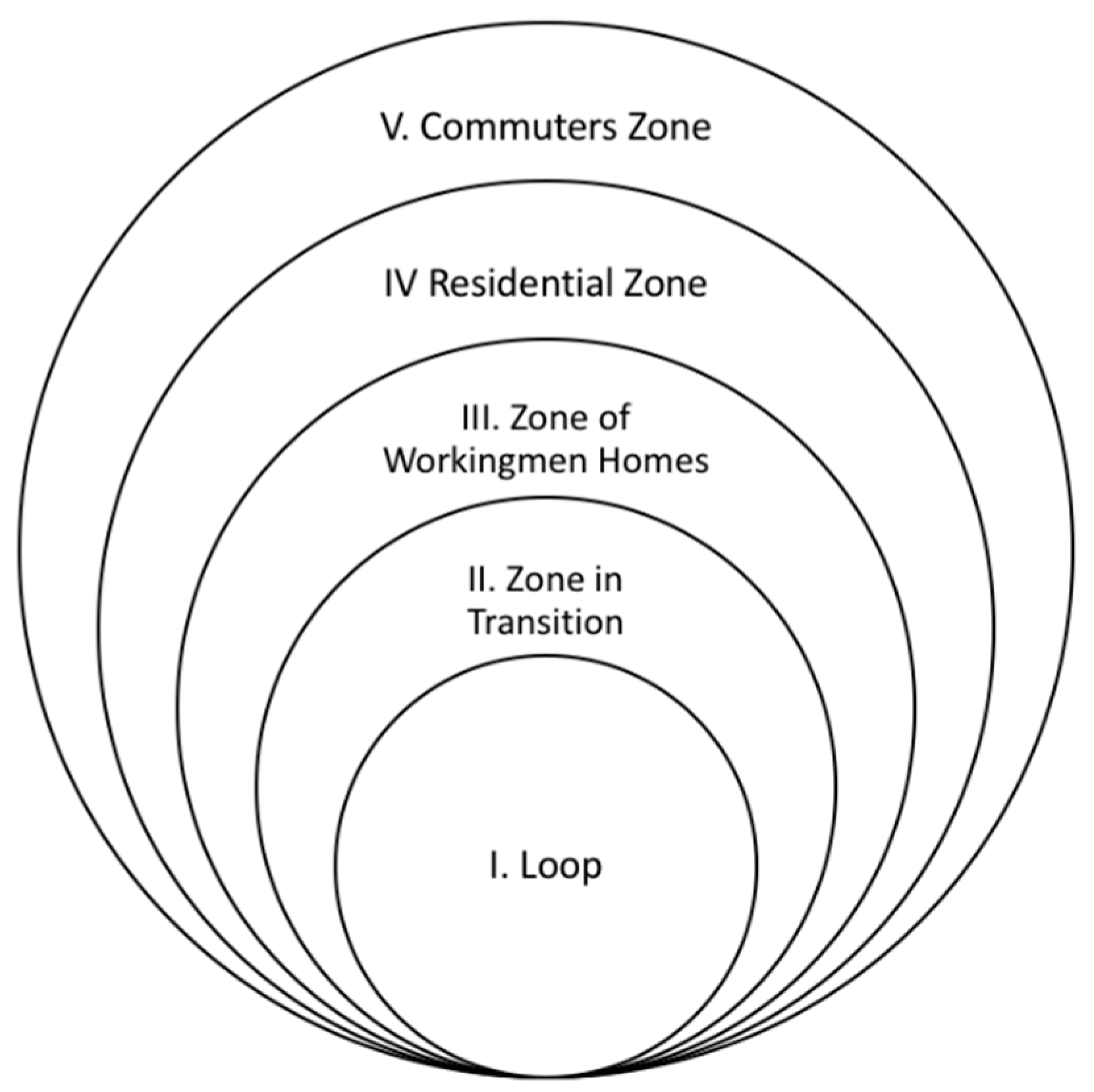

1]. As such, the field of human ecology, in its heyday, consumed itself with studying the environment ‘as is’ without the apparent bias that would inevitably come from critical works on social and economic relations therein. With these assumptions in hand, Ernest Burgess, one of Robert Park’s colleagues at the University of Chicago, in The City (1925) concluded that the intensification of industrial growth created structural pressures that caused the city to expand in a continuous sequence. This formulation, known as the ‘concentric zone’ model, posited that the city operated in a continuously blooming fashion. As newcomers came, long-time residents would move outward from the core.

In this model, the least successful at any given time would live in or at the core. They would, eventually, find their way outside of the city core. Socially and economically, they moved outward. This process continually churns the poor (as they improved their economic standing) out from the center into more and more suburban areas. As a simple illustration for his model, Burgess created the (now famous) diagram pictured below (see

Figure 1).

Burgess elaborated on this concept by noting that, during the continual movement outward from the core, each zone would experience a temporary period of equilibrium (succession) before being pushed into an outer ring by newcomers (invasion):

The tendency of each inner zone to extend its area by the invasion of the next outer zone. This aspect of expansion may be called succession, a process which has been studied in detail in plant ecology.

In the ecological order, individuals integrate themselves into their social strata which they are then bound to and move outwards. A specific social and cultural context is created by neighborhood members’ relative resemblance to one another as they are in both the same socio-economic strata and vicinity at any given time. This neighborhood, then, comes to constitute a “community” by space and time.

Evan McKenzie (1925) conceives of these communities as homogeneous—composed of clusters of people from the same race, class, occupation, etc. This view helped to rationalize the long-standing apartheid system of residential segregation that plagues American cities today as well as cities across the world such as Rio de Janeiro, Mexico City, Cairo, Mumbai, Algiers, to mention a few [

3]. Burgess stressed the point that, as with the Black Belt in Chicago, boundaries were permeable. This meant that residents lived where they live because they wanted to, voluntarily [

4]. According to urban ecologists from the University of Chicago, spatial segregation resulted in harmonious relationships and therefore created natural social order.

The way that neighborhoods were organized was a mere representation of the optimal order of human settlement more generally. Periods of ‘invasion’ were understood as periods of ecological crisis—that is, as periods of instability and unbalance. Periods of ‘succession,’ on the other hand, were constituted by the rehabilitation of social relations within a neighborhood. With these theories in hand, the authors of The City (1925) similarly defined the boundaries of neighborhoods as being natural. Different kinds of people would move in and out. However, by the end of the invasion-succession process, the boundaries would eventually re-equilibrate into a stable and natural state. Smith, an academic urban planner, explains how,

In the human ecologist’s framework, the social order and the physical space of the city were congruent. Even though the economic system was fluid, it was also presumed that spatial patterns were maintained over time, keeping different groups of people naturally segregated. From their perspective, social differentiation was evidence of economic progress, and spatial segregation was necessary for social progress.

The Chicago School conceived the city as a natural space for differentiation and competition. As cities grew, and as industries competed with one another, so too did workers. Workers would distinguish themselves from one another by acquiring new skills and filling niches—that is, empty voids in the market that could be filled. We can see that workers, and therefore, the nature of the economy itself, would provide a social good naturally and without intervention. The division of labor in capitalist society became ever more specialized and, thus, the functional differentiation of work became fundamental to the urbanization process itself.

From this classical perspective, workers earn wages according to their abilities and capabilities. This wage-gap is taken to be just as natural as their organic conceptions of city growth patterns. Importantly, this was true both for the nature of the city and the nature of human competition. Natural results were taken to be the best and most equitable and should, therefore, be allowed to work their magic without intervention.

These two conceptions of the city were taken in tandem. The city’s marketplace would naturally apportion housing to groups throughout the income strata, while each worker would place himself into his correct social order. It was only natural and fair for the more intelligent or stronger man (the best adapted from the perspective of biotic perspective) to be able to get a higher paying job. He should, according to this classical purview, be compensated only by his productivity and merit.

Assuming that minorities were hard working, through the assimilation process, they should be able to move up the economic ladder. Moving up would happen by their own volition and after only a short period of incubation in a well-functioning free market. This was seen as true no matter if the worker was male or female, Black, Jewish, Irish, Mexican, Puerto Rican, a newly arrived immigrant of any race or ethnicity. Neighborhoods were available for all groups, and the potentiality for niche-creation in the marketplace was, just like the city itself, capable of exponential growth. In the interim, former agricultural workers were adapting to the workings of industrial factories and city living.

3. Equilibrium and Personal Responsibility

The concept of “personal responsibility” (being applied to both the individual and his place in the market) is an important one, here, but it certainly is not a new one. Under this rubric, each is free to either succeed or fail of his own volition. The concept of consumer choice is a logical extension of the personal responsibility ideal. If the logic of choice fails, even if only for a moment, “it is not the fault of the system,” as Abraham Lincoln (1905) once put it, “but because of either a dependent nature which prefers it, or improvidence, folly, or singular misfortune” [

6].

Competition in the marketplace creates fairness should create an equality of opportunity evident by the outcome—whatever is, is what is supposed to be. Meanwhile, inequality is a natural part of the functional differentiation that results from this competition. For the urban ecologist, this is how the city was able to modernize. Individuals needed to compete economically with one another and, if they were self-determined, they would advance in socio-economic status. They would then have an opportunity to move to a new neighborhood with people of their new class and type of occupation. Through these entirely natural mechanisms, the city, the firm, and the individual were steadily evolving and progressing.

Classical political economy helped to validate this conception with the logic of the pricing mechanism. When a certain quantity of goods meets with a certain amount of demand in a freely functioning marketplace, the result should be a price level in a similar state of equilibrium as that of the city itself. The convenience of the combined premises of urban balance and market equilibrium did not escape the work of Robert Park (1984):

The city cannot fix land values. We leave to private enterprise, for the most part, the task of determining the city’s limits and the location of its residential and industrial districts. Personal tastes and convenience, vocational and economic interests, infallibly tend to, segregate and thus to classify the populations of great cities. In this way, the city acquires an organization and distribution of population which is neither designed nor controlled.

While the idea of balance and equilibrium existing in nature is not new, its application as a principle for understanding the physics of a city had never been as heavily formalized as it was by the Chicago School’s human ecologists. However, the self-fulfilling element of this logic (that whatever is supposed to be), constitutes a transparent attempt at rationalizing power structures and inequality. In terms of economics, this idea went too far even for Alfred Marshall (1898), the father of neoclassical economics, who denounced those who had similarly interpreted Adam Smith’s work:

Many of his followers with less philosophic insight, and in some cases with less real knowledge of the world, argued boldly that whatever is, is right...For a while, they fascinated the world by their romantic accounts of the flawless proportions of that “natural” organization of industry which had grown from the rudimentary germ of self-interest; each man selecting his daily work with the sole view of getting for it the best pay he could, but with the inevitable result of choosing that in which he could be of most service to others. They argued for instance that, if a man had a talent for managing business, he would be surely led to use that talent for the benefit of mankind: that meanwhile a like pursuit of their own interests would lead others to provide for his use such capital as he could turn to best account; and that his own interest would lead him so to arrange those in his employment that everyone should do the highest work of which he was capable, and no other […] The romantic subtilty of this “natural organization of industry” had a fascination for earnest and thoughtful minds; it prevented them from seeing and removing the evil that was intertwined with the good in the changes that were going on around them; and it hindered them from inquiring whether many even of the broader features of modern industry may not be transitional, having indeed good work to do in their time, as the caste system had in its time.

To paraphrase the quote of Marshall used above, the self-fulfilling prophecy of spontaneous order can be used to legitimize nearly any evil. For those who seek to use economism and rationalize their predilection to blame systemic problems on individuals, this way of thinking has been quite useful. People want, the argument goes, better access to jobs, parks, houses, and services. Individuals should be willing to leave their homes and communities whenever it is convenient so that they can crawl up the housing ladder. Workers should move up through the income-strata by continually finding new and better employment. If they—through impudence or laziness or merely preference—decided to stay where they were, it was their choice and so should be respected and left alone. Similarly, if they are improving their station in life, they should not be kept from the things that they are doing (e.g., moving to suburbia and gentrifying whole neighborhoods). It is what is happening, so it must be what people want.

Robert Park shared in these ideologies with the economist Friedrich von Hayek. Hayek (1978), himself, refuted the idea that organizations would ever be capable of scientifically and rationally managing and designing an economy that would ever result in a Great Society. He thought that it was impossible for an individual or an organization to acquire full knowledge over the factors of production, consumption, and distribution. For Hayek, centralized decision-making is not only pretentious but also antithetical to progress and liberty. Institutions, if allowed to function at their liberty, where individuals each act upon their knowledge in a system of abstract relations and interactions, giving one another signals about what to produce and what not to produce, would not only function better but would also protect individual freedoms in the process. Great things in society, Hayek argues, “result of human action but not of human design” [

9].

4. Theories of Neighborhood Change

I turn now to Homer Hoyt who revised Burgess’ concentric zones model into one emphasizing a sectoral formulation of cities. Hoyt (1999) also introduced the idea of ‘filtering’ which meant that as higher income class people did better, they would move “outward toward the periphery of the city” in order to get better and bigger houses [

10]. As households moved to the periphery, they would free-up the older and deteriorating housing stock they left behind in the city center.

This housing would then be passed on to more impoverished populations. The quality of this housing was for the newcomers marginally better than previously. Lower-income individuals were also seen to be advancing in their progression up through the housing ladder. Under the filtering theory, homes are seen almost solely as utilities. Homes were not seen as the center of one’s social life, nor as a centerpiece for a community that might be integral to improving an individual or household’s social standing. Moving to the periphery was just a matter of maximizing utility and efficiency for the household. Through the addition of this lens, ecological conversations shifted from houses to housing markets and housing values. As Smith (1998) notes,

A crucial distinction of the filtering model is the transition from the neighborhood as a site for community-based on common ethnicity or race, to the neighborhood as a “housing market” occupied by different income groups. Overall, the boundaries that produce neighborhoods in space—census tracts—remain unchanged as the contents are recast. In part, this transition may reflect a “retooling” to capture the rise in home buyers as mortgages became available. Not only is the previous preference for homeownership reinforced in the filtering model, but it is also elevated to a new form of status. Filtering is also a tool to construct identity-based neighborhoods on both social distance and economic distance.

With Hoyt’s model, as opposed to those stemming from the Chicago School, the government could now be conceived of as an agent for social change. On the one hand, the state could be responsible for assisting developers with the construction of new housing in the periphery. While, on the other hand, providing homeowners with mortgages so they could afford these newly constructed homes—to smoothen the organic and natural process of filtering.

As noted above, Hoyt’s principles necessitated the existence of a rational economic man, opting where to live based purely on his utility and marginal gains. Again, depictions of the city ignored fundamental questions of race and how the capitalist state institutionalized racism. Even though the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) was created to provide mortgages to low-income but otherwise qualified households, refused to offer mortgages to African Americans and other minority communities [

11]. Furthermore, the Savings and Loan industry’s Federal Home Loan Bank Board required member thrifts to practice exclusionary lending practices by arbitrarily exorcizing perceivably ethnic communities from their lending areas—a process known as redlining [

12].

Redlining was justifiable, according to policy-makers’ interpretation of Morton Grodzin’s work, because as neighborhoods with too large of a minority population would cause whites to flee the area. The point at which whites would allow another ethnicity to live in their neighborhood before moving out, according to Grodzin, represented a racial “tip point” which was to be avoided if one sought to maintain a stable neighborhood.

This process of “tipping” proceeds more rapidly in some neighborhoods than in others. White residents who will tolerate a few Negroes as neighbors, either willingly or unwillingly, begin to move out when the proportion of Negroes in the neighborhood or apartment building passes a certain critical point. This “tip point” varies from city to city and from neighborhood to neighborhood. But for the vast majority of white Americans a tip point exists. Once it is exceeded, they will no longer stay among Negro neighbors.

Tipping is a concept that emerges from the human ecologist’s point of view. It is assumed that invasion will inevitably result in succession because social groups will not live in the same neighborhood. What is interesting here is also who invades and who engages in succession. African Americans were seen as the invaders, while whites were seen as the ones that responded to threat communally.

Policies built from and rationalized by these ideas worked to exclude minorities from white communities and created a dual housing market in the United States. Under New Deal policy structures, segregated blacks were forced into inner-city slums. Meanwhile, new highways and continually expanding suburban developments were facilitated through tax deductions on home mortgage interest payments for the benefit of middle- and upper-class whites [

14]. As Gail Radford (1996) writes,

Much of the new scholarship on the history of the state has probed the origins and outcomes of the tiered pattern of policy development …, particularly concerning income-support programs where social security has become highly differentiated from so-called welfare programs. State activity about housing manifests a similar structure, with an upper tier composed of mortgage guarantee programs, quasi-public secondary mortgage markets, highway building, and tax subsidies that support private homeowners, businesses in the real estate sector (developers, contractors, brokers, etc.), and financial institutions.

The ramifications of these policy structures and their underlying ideologies had significant repercussions throughout the history of the US, as Radford goes on to write,

Given that the mechanisms to reorganize the financial system used by New Deal housing programs were largely invisible to the average person, many core Democratic constituencies came to believe that they were not receiving any public help. Meanwhile, these groups perceived themselves to be paying for programs to benefit groups they regarded as less hardworking and deserving than themselves. As it worked out, then, most Americans came to credit the market and their own efforts for the increase in living standards that occurred after the New Deal.

Throughout the New Deal era, during the explosive urban growth of the so-called long boom, whites were put in a preferred and lucrative position to accumulate wealth through homeownership credits, access to cheap and reliable credit, and other public subsidies. In contrast, blacks and other minority groups were, excluded entirely from any possibility of achieving the self-realization potential proffered by human ecologists. Through the self-fulfilling logic of ecological providence, combined with the near invisibility of welfare provision in the form of subsidies to whites. As noted by Radford above, the nations’ emergent leisure class were blinded from the reality of the massive inequalities that were fueling their success.

The overtly racist activities of the state were also combined to facilitate capital accumulation in general as banks, realtors, and developers profited from the massive suburban boom fortified by cheap credit and tax incentives. By emphasizing the human ecological ideas of difference and competition, and by insisting on the neutrality and naturalness of homogeneity in outcomes, the state was able to facilitate the massive absorption of populations into urbanity (a necessary component for the expansion of capital) while maintaining the values and ideals of the dominant classes.

Anthony Downs (1994) attributed suburban development to the deterioration of housing in the urban core. As homes degraded, he felt, over time, the homes would trickle-down into the hands of low-income households, often racial minorities. Meanwhile, wealthier populations would move to newer houses in the periphery [

16]. From the ecological perspective, individuals improved their standing within the housing ladder through this hand-me-down process. This process, known as housing life-cycle theory, explained that while homes age, they are either redeveloped or fall into disrepair. Whole neighborhoods—thus constituted as an agglomeration of individual houses—can fall into disrepair in this process and render whole areas as a ghetto. The intuitive nature of the housing life-cycle theory helped to justify urban renewal efforts in which Public Housing Authorities tore down ‘blighted’ buildings and, indeed, entire neighborhoods where people of color lived [

17].

For the urban ecologist, the inner-city neighborhood was ‘sick’—that is, crime-ridden, immoral, full of decadence and obsolete land uses. Characters with fragmented personalities inhabited the inner-city, be they promiscuous, drunk, or otherwise vice-prone, etc. Illnesses were a sign of inhabitants who failed to adapt and, thus, disturbed the equilibrium of the community. The government decided to intervene to give loans and subsidies to private developers and businesses who would redevelop decaying inner-city neighborhoods. The interventionist act resulted in the wholesale destruction, gentrification, and displacement of poor communities (mostly black—this, is why the program became infamously known as ‘Negro removal’). However, it did so while expanding the capacity for capital’s continued expansion and growth.

The federal government did build public housing for some (perhaps one of every ten) residents displaced by urban renewal programs [

18]. Public housing mainly came in the form of Le Corbusier-style towers. The high-rises were plopped into vast expanses of empty green space and placed into superblocks erected where the blight once thrived in large cities like Chicago, New York, St. Louis, and others. These modern-styled buildings, although centrally planned, were a symbol for order and were meant to emulate and harness the ecologist’s sense of balance existing in nature. Le Corbusier (1987) even went so far as to compare the home to the human cell:

We must never, in our studies, lose sight of the purely human “cell,” the cell which response most perfectly to our physiological and sentimental needs. We must arrive at the “house-machine,” which must be both practical and emotionally satisfying and designed for a succession of tenants.

Public housing in the US was viewed as temporary by planners as, after balance was reestablished, residents were expected to find jobs and find their way into the private market to become homeowners. Though the scope of this paper does not allow me to delve into this here, there are lengthy explanations about just why, in a matter of only 10–15 years, these once majestic buildings fell into disrepair and became. As Oscar Newman (1973) once put it, these vertical towers surrounded by horizontal green spaces became “indefensible spaces” [

20]. The point here, however, is that even while these cities of towers were perceived to be emulating the ordered systems ecologists obsess over, the failures of central planning were attacked by those who believed that the free market knows best for not being natural enough.

HOPE VI developments later sought to create brand new communities where Le Corbusierian towers once stood in an attempt to redevise the long-sought ideal of a managed, natural balance. Tacitly, these neo-ecologists, as we might call them, sought to create balance quantitatively by composing communities with a mixture of 1/3 public, 1/3 affordable, and 1/3 market-rate housing. This ideal is similar to those of Hoyt, who saw a tipping point in race as being problematic for neighborhoods. Contemporary planners, conversely, feel they can achieve the original goals by disregarding race altogether and merely stabilizing a community through an admixture of different income groups. Neighborhoods, apparently, as Jane Jacobs (1992) once wrote, “need the talents and stabilizing influence of the middle class. Presumably,” she continues, “these qualities are to seep out by osmosis” [

21].

5. Discrimination in Housing Policy

Much of Park’s, Burgess’, Hoyt’s, and other’s assumptions are undermined by the fact that there has been intentional discrimination in housing policy. Several federal policy changes after the war helped to facilitate the movement of residents from urban to suburban areas. Perhaps most notable among these policy changes were the Interstate Highway System of 1955 and the National Housing Act of 1949. In particular, the Housing Act of 1949 provided funds for slum clearance (title I), FHA insured mortgage programs (title II), and the construction of public housing (title III). From the time of the passage of the act, suburbs sprawled impulsively as middle and upper-class residents left city centers in search of greener (or, perhaps more appropriately, “whiter”) pastures [

22]. The process of suburbanization was further exacerbated by racist fears among whites of blacks and other minority groups. This fear was coupled with a cultural disdain for working-class populations more generally. Again, the federal government facilitated the isolation of the poor into urban slums through federally supported programs, such as redlining and public housing concentrations [

23]. Coupled with federal and state expenditures on systems of highways throughout the country starting in the mid-1950s and tax incentives which most significantly privileged white, suburban homeowners, their schools, their jobs, and so forth, the US effectively established a two-tiered housing and economic structure which came to benefit the wealthy at the expense of the poor [

24].

As the white middle-class fled to the periphery, the tax bases of city centers contracted, and merchant and industrial capitalists followed the moneyed classes into the suburbs. With the loss of an economic base, city centers declined precipitously [

25]. Minorities suffered the most in the processes of suburbanization and decentralization [

26]. As city centers declined, as buildings, streets and parks collapsed into disrepair. As urban populations struggled for survival, and as city governments continually fought to reestablish their city’s cores—American suburbanites enjoyed rising wages and increasing prosperity [

27].

In 1974, the Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) program was instituted as a further attempt to revitalize the urban centers of American cities, which remained the domain of the poor and disenfranchised [

27]. While modern ideas of inclusion are currently ubiquitous in the planning community, at this time in American history, diversity was nearly an unheard argument. Planning, up to this point, was dominated by segregation of races, by compartmentalization of uses in rationally planned cities. Planning was not dominated by community-building, but by the perpetual clearance of so-called “blighted” communities and continual urban renewal, which had devastating consequences for American cities [

21].

Since the metamorphosis of urban renewal as a city planning platform, cities are now—and are increasingly becoming more so—post-industrial in their orientation [

28]. This has again picked the interest of those who most desire an urban lifestyle and put increasing pressures on those already inhabiting spaces with location and other qualities. Since the 1970s, American cities have become increasingly desirable to younger generations and those seeking work in the (now dominant) service industries [

29]. Moreover, an investment inside and near the city’s central business district (CBD) provides the combined opportunity of capturing rent and living in an environment of spectacle near work and the cathedrals of consumption.

Although many American cities have been losing population (especially former industrial cities like Detroit), according to many scholars, others have grown exponentially in the face of reinvestment in urban centers over the past few decades [

30]. It is important to note, however, that this is not necessarily the result of people moving to cities. Cities in the South, for instance, have been growing steadily for a long time while cities like New York and Los Angeles may capture the bulk of this growth.

However, despite the myth of a “melting pot”—that is, the perception that a slow but permanent homogenization of classes and races in cities takes place—racial and ethnic marginalization remain as dominant themes in the modern American metropolis [

31]. Meanwhile, as Wyly and Hammel (1999) noted, the reality of cities today is more like “islands of decay in seas of renewal” rather than Brian Berry’s original dictum [

32]. The tendencies further exacerbate this for ethnic and racial groups to cluster.

Furthermore, disparities in income and educational attainment still dominate and have grown in the urban fabric. In 2017, 21 percent of the white populous 25 years and older had the opportunity of obtaining a college degree. Only 13 percent of blacks and 11 percent of Latinos were able to achieve a similar status [

33].

Being trapped in ethnic/racial enclaves with little chance of achieving the educational or economic status of whites coupled with the increasing interest of younger generations for urban lifestyles and jobs returning to the core, minorities in cities are now undergoing the pressures of gentrification. Under the circumstances, it is becoming increasingly important to develop new and innovative ways of maintaining valuable urban spaces for minority populations. However, this challenge is met with broader socio-economic changes. Most importantly, the rise of service-sector employment, of finance and of the increasing necessity to obtain a high-skill level to compete for jobs in the city. This is also a problem because many ethnic neighborhoods are simultaneously compelled to sell their culture to attract dollars from potential tourists.

On the one hand, it is a balancing act to create both a unique, identifiable and attractive place for investment and tourism and on the other hand, to prevent displacement by wealthier groups—particularly white, college-educated, yuppies, pre-professionals. In a way, much of the human ecologists’ assumptions have helped to normalize what has been intentional discrimination in housing policy. These processes are not the natural organization of cities.

6. Conclusions

One of the most fundamental problems with ecological models, especially as formulated by those seeking to discover “laws” pertaining to the growth of cities or of urban change more generally, is that they, echoing conceptions of personal responsibility used by economists, rationalize power structures and make them seem to be natural and normal mechanisms of human behavior. We can easily see that from the lens of the ecologist, the current state of things appears to be precisely as it should be. Both of these topics are presented in such a way as to lead audiences to the conclusion that any attempt to stop these apparently natural processes would inevitably entail creating disequilibrium in the overall structure. All interaction would, therefore (and this is as true for the urban ecologist as it is for economists), necessarily have deleterious and damaging consequences in the last instance—regardless of the benevolent intentions of the urban planner.

The existence of gentrification inverts the underlying logic embedded in the ecologists’ depiction of equilibrium by recognizing the disparities existing between properties and neighborhoods. By understanding the history of housing policy in the US, one driven by discrimination, we are able to create a reasonable depiction of the concrete interactions of players “on the ground” such as the banking industry which drove redlining practices. Understanding how housing policy was discriminatory to people of color provides us with a critical theoretical model from which to counter the narratives of personal responsibility and demonstrating that the current state of things did not—and does not—comprise the only result that may have been possible. In other words, rejecting human ecology and the natural organization of communities opens a door through which urban planning and intervention might be legitimized in the face of laissez-faire ideals. Gentrification is not the result of natural mechanisms which rightfully renew the city. It is the result of policies that allow the increase of wealth at the expense of those that are displaced.

It is essential, however, to understand that new theories of gentrification and neighborhood change do not replace the ecological models advanced by early 20th-century urban theorists. It merely rearticulates their ecological argument within the modern economistic modality. Gentrification is not natural, as opposed to the ecologists who perceive the accumulation blight to be, in essence, inevitable and its clearance to be a civic necessity. Still, gentrification does happen when investors start gobbling up distressed or otherwise undervalued properties. As they do this, we can presume, other investors are likely to see this investment as a clue that they too should invest. Slowly or quickly, the result is the clearance of one population (articulated here as being represented by their concentration within income strata) by another, wealthier, population capable of affording the increased rents. The increased demand is, however, dependent on a conception of cities which conforms quite nicely to ecological ideals. Here, as it is with ecologists, a neighborhood is such only as a relational object to the rest of the city.

For the urban ecologists, blight was a result of the relative delinquency and the filtering out of better and worse populations. Today, displacement is a result of changes in relative prices and the filtering out of higher and lower income strata. In substance, these two arguments are more similar than dissimilar, but at least in more modern urban theory, we see a fundamental critical component with the capacity to provide a necessary counterpoint to theories which fetishize personal responsibility.

All that being said, ecological conceptions of spontaneous and natural order within cities permeate theoretical discourses and urban ideologies about urbanity. Embedded within these urban theoretical frameworks is the tendency to see urban actors in either wildly generalized terms. For example, in groupings which are never explored critically, but assumed without elaboration. They are also seen in the idealized and highly abstract terms of individuality—a discourse which, more often than not, serves as little more than a shroud from which to criticize those found to be at fault for disequilibrium and disorder. With these ideological pretensions in hand, urban theorists have constructed an array of elaborate and complex models to elucidate urban economic, political, and social change, none of which, incidentally, have provoked any form of unanimity within the academic community.