Quality Assessment of Cooked Ham from Medium-Heavy Pigs Fed with Antioxidant Blend

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animal and Dietary Treatment

2.2. Carcass Traits

2.3. Sampling

2.4. Physical Parameters

2.5. Chemical Parameters

2.6. Oxidative Stability

2.7. Sensory Analysis

2.8. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Physical Parameters

3.2. Chemical Parameters

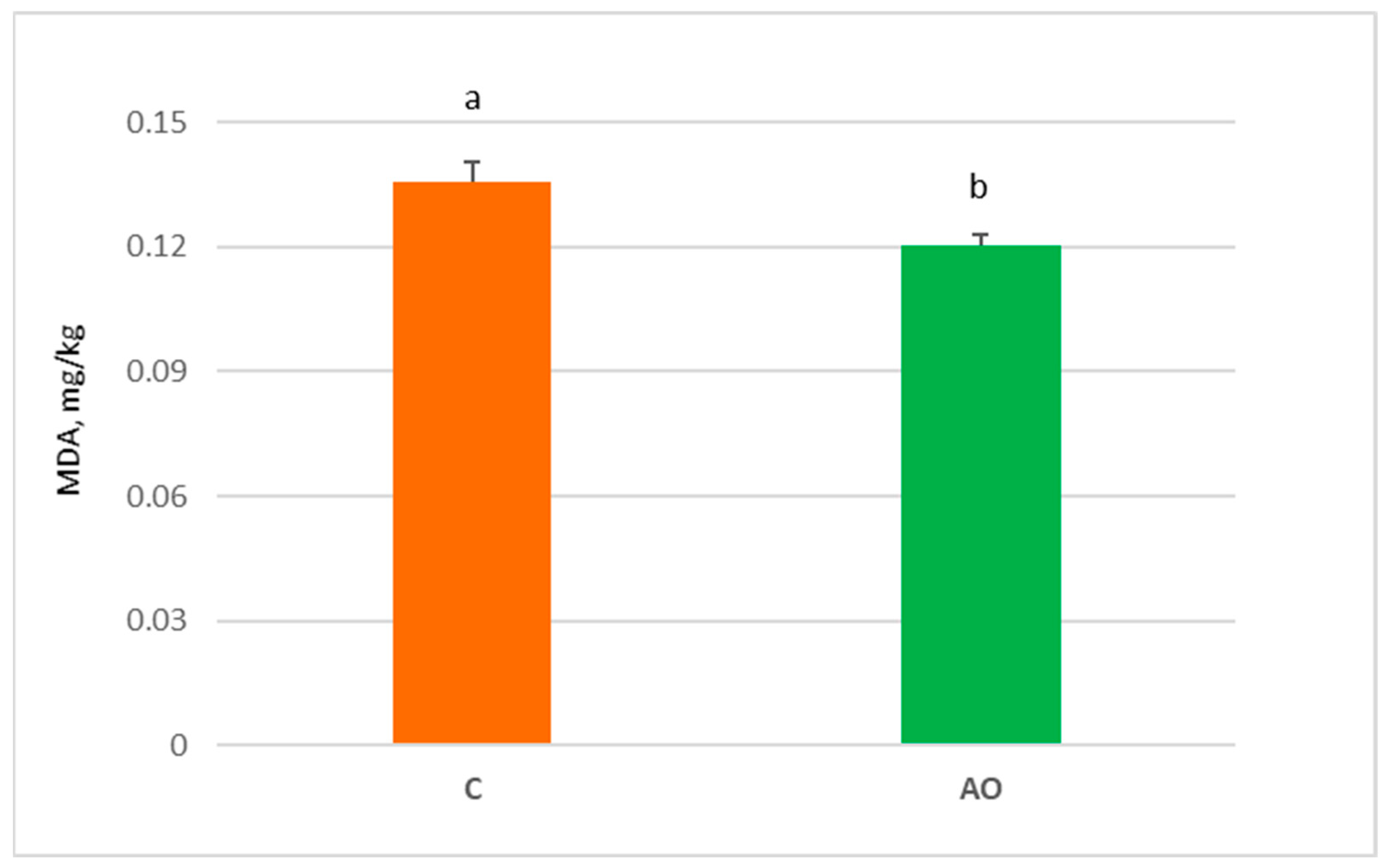

3.3. Oxidative Stability

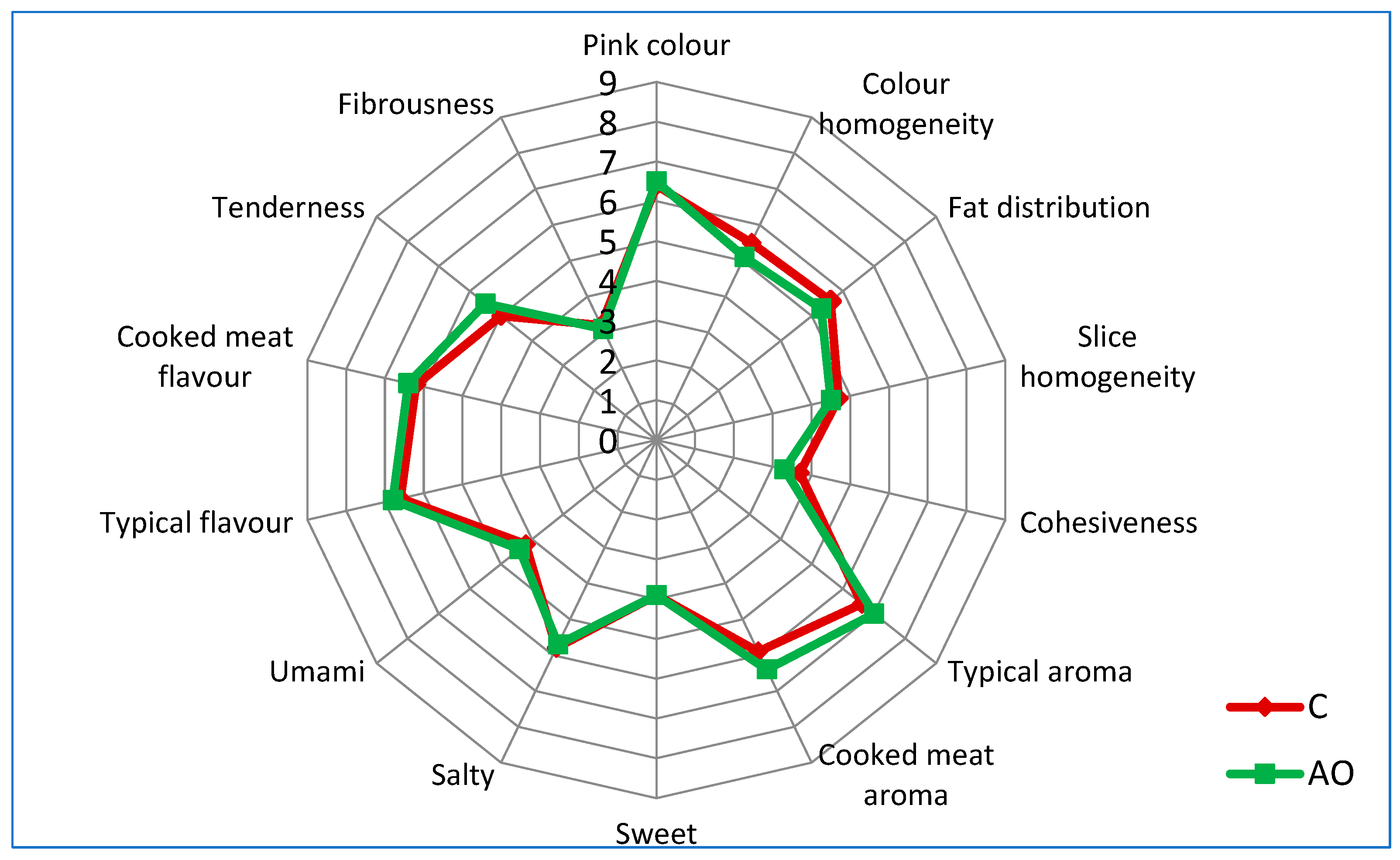

3.4. Sensory Profile

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Associazione Industrial Delle Carni e dei Salumi (ASSICA). Annual Report 2021. Available online: https://www.assica.it/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/Rapporto-Annuale-ASSICA-2021_def.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- Benet, I.; Guàrdia, M.D.; Ibañez, C.; Sola, J.; Arnau, J.; Roura, E. Roura Low intramuscular fat (but high in PUFA) content in cooked cured pork ham decreased Maillard reaction volatiles and pleasing aroma attributes. Food Chem. 2016, 196, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebret, B.; Čandek-Potokar, M. Review: Pork quality attributes from farm to fork. Part II. Processed pork products. Animal 2022, 16, 100383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moretti, V.M.; Bellagamba, F.; Paleari, M.; Beretta, G.; Busetto, M.L.; Caprino, F. Differentiation of cured cooked hams by physico-chemical properties and chemometrics. J. Food Qual. 2009, 32, 125–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez, R.; Pateiro, M.; Gagaoua, M.; Barba, F.J.; Zhang, W.; Lorenzo, J.M. A Comprehensive Review on Lipid Oxidation in Meat and Meat Products. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, S.A.; Zhang, G.; Decker, E.A. Biological Implications of Lipid Oxidation Products. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2017, 94, 339–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haile, D.; De Smet, S.; Claeys, E.; Vossen, E. Effect of light, packaging condition and dark storage durations on colour and lipid oxidative stability of cooked ham. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2013, 50, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haak, L.; Raes, K.; Smet, K.; Claeys, E.; Paelinck, H.; De Smet, S. Effect of dietary antioxidant and fatty acid supply on the oxidative stability of fresh and cooked pork. Meat Sci. 2006, 74, 476–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranucci, D.; Miraglia, D.; Trabalza-Marinucci, M.; Acuti, G.; Codini, M.; Ceccarini, M.R.; Forte, C.; Branciari, R. Dietary effects of oregano (Origanum vulgaris L.) plant or sweet chestnut (Castanea sativa Mill.) wood extracts on microbiological, chemico-physical characteristics and lipid oxidation of cooked ham during storage. It. J. Food Saf. 2015, 4, 5497. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.; Hernandez, P.; Djordjevic, D.; Faraji, H.; Hollender, R.; Faustman, C.; Decker, E.A. Effect of antioxidants and cooking on stability of n-3 fatty acids in fortified meat products. J. Food Sci. 2006, 71, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karre, L.; Lopez, K.; Getty, K.J.K. Natural antioxidants in meat and poultry products. Meat Sci. 2013, 94, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gülçin, I. Antioxidant activity of food constituents: An overview. Arch. Toxicol. 2011, 86, 345–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Kempen, T.A.T.G.; de Bruijn, C.; Reijersen, M.H.; Traber, M.G. Water-soluble all-rac α-tocopheryl-phosphate and fat-soluble all-rac α-tocopheryl-acetate are comparable vitamin E sources for swine. J. Anim. Sci. 2018, 28, 3330–3336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vossen, E.; Claeys, E.; Raes, K.; van Mullem, D.; De Smet, S. Supra-nutritional levels of α-tocopherol maintain the oxidative stability of n-3 long-chain fatty acid enriched subcutaneous fat and frozen loin, but not of dry fermented sausage. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2016, 96, 4523–4530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Winne, A.; Dirinck, P. Studies on Vitamin E and Meat Quality. 3. Effect of Feeding High Vitamin E Levels to Pigs on the Sensory and Keeping Quality of Cooked Ham. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1997, 45, 4309–4317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Goel, N. Phenolic acids: Natural versatile molecules with promising therapeutic applications. Biotechnol. Rep. 2019, 24, e00370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alipieva, K.; Korkina, L.; Orhan, I.E.; Georgiev, M.I. Verbascoside—A review of its occurrence, (bio)synthesis and pharmacological significance. Biotechnol. Adv. 2014, 32, 1065–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, R.; Pastorelli, G.; Cannata, S.; Tavaniello, S.; Maiorano, G.; Corino, C. Effect of long term dietary supplementation with plant extract on carcass characteristics meat quality and oxidative stability in pork. Meat Sci. 2013, 95, 542–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossi, R.; Stella, S.; Ratti, S.; Maghin, F.; Tirloni, E.; Corino, C. Effects of antioxidant mixtures in the diet of finishing pigs on the oxidative status and shelf life of longissimus dorsi muscle packaged under modified atmosphere. J. Anim. Sci. 2017, 95, 4986–4997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Research Council (NRC). Nutrition Requirements of Swine, 10th ed.; National Academy Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- AOAC. Official Methods of Analysis, 17th ed.; Association of Analytical Communities: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Monin, G.; Hortos, M.; Diaz, I.; Rock, E.; Garcia-Regueiro, J.A. Lipolysis and lipid oxidation during chilled storage of meat from Large White and Pietrain pigs. Meat Sci. 2003, 64, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 13299:2016; Sensory Analysis—Methodology—General Guidance to Establish a Sensory Profile. ISO International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016.

- ISO/DIS 8589:2007; Sensory Analysis—General Guidance for the Design of Test Rooms. ISO International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007.

- MacFie, H.J.; Bratchell, N.; Greenhoff, K.; Vallis, L.V. Designs to balance the effect of order of presentation and first-order carry-over effects in hall tests. J. Sens. Studies 1989, 4, 129–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lea, P.; Naes, T.; Rodbotten, M. Analysis of Variance for Sensory Data, 1st ed.; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 1997; pp. 99–101. [Google Scholar]

- Pancrazio, G.; Cunha, S.C.; De Pinho, P.G.; Loureiro, M.; Ferreira, I.M.; Pinho, O. Effect of Tumbling Time on Cooked Ham. J. Food Qual. 2015, 38, 359–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sárraga, C.; Guàrdia, M.D.; Díaz, I.; Guerrero, L.; García Regueiro, J.A.; Arnau, J. Nutritional and sensory quality of porcine raw meat, cooked ham and dry-cured shoulder as affected by dietary enrichment wit docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) and α-tocopheryl acetate. Meat Sci. 2007, 76, 377–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pateiro, M.; Domínguez, R.; Bermúdez, R.; Munekata, P.E.S.; Zhang, W.; Gagaoua, M.; Lorenzo, J.M. Antioxidant active packaging systems to extend the shelf life of sliced cooked ham. Current Res. Food Sci. 2019, 1, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomović, V.M.; Jokanović, M.R.; Petrović, L.S.; Tomović, M.S.; Tasić, T.A.; Ikonić, P.M.; Šumić, Z.M.; Šojić, B.V.; Škaljac, S.B.; Šošo, M.M. Sensory, physical and chemical characteristics of cooked ham manufactured from rapidly chilled and earlier deboned M. semimembranosus. Meat Sci. 2013, 93, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoving-Bolink, A.H.; Eikelenboom, G.; van Diepen, J.T.; Jongbloed, A.W.; Houben, J.H. Effect of dietary vitamin E supplementation on pork quality. Meat Sci. 1998, 49, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahucky, R.; Nuernberg, K.; Kovac, L.; Bucko, O.; Nuernberg, G. Assessment of the antioxidant potential of selected plant extracts—In vitro and in vivo experiments on pork. Meat Sci. 2010, 85, 779–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Válková, V.; Saláková, A.; Buchtová, H.; Tremlová, B. Chemical, instrumental and sensory characteristics of cooked pork ham. Meat Sci. 2007, 77, 608–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Q.; Sun, D.W.; Scannell, A.G.M. Feasibility of water cooking for pork ham processing as compared with traditional dry and wet air cooking methods. J. Food Eng. 2005, 67, 427–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desmond, E.M.; Kenny, T.A.; Ward, P. The effect of injection level and cooling method on the quality of cooked ham joints. Meat Sci. 2002, 60, 271–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pateiro, M.; Barba, F.J.; Domínguez, R.; Sant’Ana, A.S.; Khaneghah, A.M.; Gavahian, M.; Gómez, B.; Lorenzo, J.M. Essential oils as natural additives to prevent oxidation reactions in meat and meat products: A review. Food Res. Int. 2018, 113, 156–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manach, C.A.; Scalbert, C.; Morand, C.; Rémésy, L. Jiménez Polyphenols: Food sources and bioavailability. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2004, 79, 727–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Item 1 | C | AO | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dry matter % | 31.94 ± 0.26 | 31.99 ± 0.22 | 0.955 |

| Crude protein, % 2 | 20.25 ± 0.25 | 19.78 ± 0.29 | 0.401 |

| Crude fat, % 2 | 7.49 ± 0.40 | 7.71 ± 0.20 | 0.801 |

| Ash, % 2 | 2.55 ± 0.01 | 2.56 ± 0.03 | 0.375 |

| F Value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Descriptor | Samples | Judges | Replicates | S × J * | S × R * | J × R * |

| Appearance | ||||||

| Pink colour | 0.01 | 14.22 * | 0.69 | 1.39 | 1.52 | 0.82 |

| Colour homogeneity | 1.12 | 8.47 * | 1.20 | 1.54 | 2.99 | 0.48 |

| Fat distribution | 0.53 | 4.39 * | 0.58 | 1.14 | 0.09 | 0.59 |

| Slice homogeneity | 0.35 | 4.72 * | 3.04 | 0.88 | 2.59 | 0.52 |

| Cohesiveness | 0.55 | 4.69 * | 0.33 | 0.33 | 0.18 | 0.67 |

| Aroma | ||||||

| Typical | 3.36 | 43.99 * | 0.33 | 1.41 | 0.13 | 1.37 |

| Cooked meat | 2.18 | 16.54 * | 0.23 | 0.50 | 3.08 | 1.16 |

| Taste | ||||||

| Sweet | 0.001 | 13.87 * | 1.15 | 0.65 | 1.97 | 0.78 |

| Salty | 0.81 | 2.91 * | 0.74 | 0.65 | 1.36 | 0.48 |

| Umami | 0.60 | 30.71 * | 2.38 | 0.60 | 0.32 | 0.76 |

| Flavour | ||||||

| Typical | 1.10 | 25.62 * | 1.66 | 1.14 | 0.20 | 1.78 |

| Cooked meat | 0.28 | 9.41 * | 2.23 | 0.47 | 0.38 | 1.44 |

| Texture | ||||||

| Tender | 2.34 | 22.64 * | 0.78 | 1.41 | 0.86 | 0.62 |

| Fibrous | 0.18 | 28.01 * | 1.89 | 1.31 | 0.77 | 1.27 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rossi, R.; Corino, C.; Ratti, S.; Mainardi, E.; Vizzarri, F. Quality Assessment of Cooked Ham from Medium-Heavy Pigs Fed with Antioxidant Blend. Sci 2025, 7, 153. https://doi.org/10.3390/sci7040153

Rossi R, Corino C, Ratti S, Mainardi E, Vizzarri F. Quality Assessment of Cooked Ham from Medium-Heavy Pigs Fed with Antioxidant Blend. Sci. 2025; 7(4):153. https://doi.org/10.3390/sci7040153

Chicago/Turabian StyleRossi, Raffaella, Carlo Corino, Sabrina Ratti, Edda Mainardi, and Francesco Vizzarri. 2025. "Quality Assessment of Cooked Ham from Medium-Heavy Pigs Fed with Antioxidant Blend" Sci 7, no. 4: 153. https://doi.org/10.3390/sci7040153

APA StyleRossi, R., Corino, C., Ratti, S., Mainardi, E., & Vizzarri, F. (2025). Quality Assessment of Cooked Ham from Medium-Heavy Pigs Fed with Antioxidant Blend. Sci, 7(4), 153. https://doi.org/10.3390/sci7040153