Embankment Fires on Railways—Where and How to Mitigate?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Hazard Indication Map for Embankment Fires

2.2. Case Study Site Open Digital Test Field (ODT)

2.3. Fire Mitigation Measures

3. Results

3.1. Embankment Fire Susceptibility Class Distribution Within the Test Field

3.2. Technical Solutions to Reduce Embankment-Fire Susceptibility

- Mechanical clearance and mowing:

- Chemical herbicides:

- Mineral firebreaks:

- Prescribed burning:

- Irrigation systems:

3.3. Vegetation-Based Mitigation

4. Discussion

4.1. Site-Specific Implementation Strategy

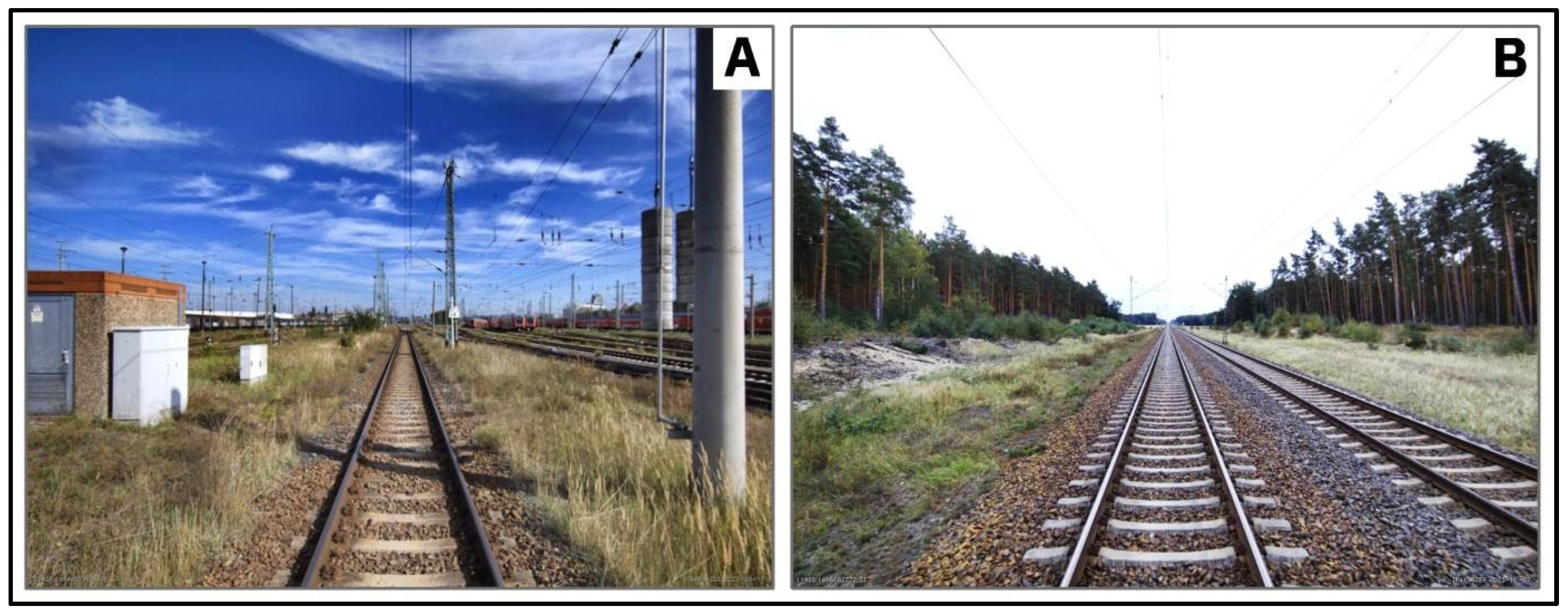

4.1.1. Urban Hotspot

4.1.2. Rural Hotspot

4.2. Nature-Based Solutions to Reduce Embankment Fire Susceptibility

4.3. Limitations and Research Needs

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DZSF | Deutsches Zentrum für Schienenverkehrsforschung (German Centre for Rail Traffic Research) |

| EBA | Eisenbahn-Bundesamt (Federal Railway Authority) |

| ODT | Open Digital Test Field |

| NbS | Nature-based Solutions |

| SMI | Soil Moisture Index |

| ROC | Receiver Operating Characteristic |

| AUC | Area Under Curve |

| MaxEnt | Maximum Entropy (model) |

| LFMC | Live Fuel Moisture Content |

| SLA | Specific Leaf Area |

| BD | Bulk Density |

| VOCs | Volatile Organic Compounds |

| BfN | Bundesamt für Naturschutz (Federal Agency for Nature Conservation) |

| DWD | Deutscher Wetterdienst (German Weather Service) |

| GIS | Geographic Information System |

| RCP | Representative Concentration Pathway |

References

- Trinks, C.; Hiete, M.; Comes, T.; Schultmann, F. Extreme Weather Events and Road and Rail Transportation in Germany. Int. J. Emerg. Manag. 2012, 8, 207–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hetzel, G.; Goldammer, J.G. The use of prescribed fire on embankments along railway tracks for reducing wildfire ignition in Germany. Int. For. Fire News (IFFN) 2004, 30, 65–69. Available online: https://gfmc.online/iffn/iffn_30/13-IFFN-30-Germany-Railways.pdf (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Szymczak, S.; Backendorf, F.; Blauhut, V.; Bott, F.; Fricke, K.; Herrmann, C.; Klippel, L.; Walter, A. Heat and Drought Induced Impacts on the German Railway Network. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 72, 696–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutscher Bundestag. Antwort der Bundesregierung auf die Kleine Anfrage der Abgeordneten Matthias Gastel, Lisa Badum, Harald Ebner, weiterer Abgeordneter und der Fraktion BÜNDNIS 90/DIE GRÜNEN—Drucksache 19/32178—Resilienz der Verkehrsinfrastruktur unter Bedingungen der Klimakrise; Deutscher Bundestag: Berlin, Germany, 2021; Available online: https://dserver.bundestag.de/btd/19/321/1932178.pdf (accessed on 6 September 2025).

- Blackwood, L.; Renaud, F.G.; Gillespie, S. Nature-based solutions as climate change adaptation measures for rail infrastructure. Nat. Based Solut. 2022, 2, 100013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackwood, L. A framework for the successful application of nature-based solutions for climate change adaptation on rail infrastructure developed through the examination of two case studies. Nat. Based Solut. 2024, 5, 100126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeanneau, A.; Zecchin, A.; van Zelden, H.; Vanhout, R.; McNaught, T.; Wouters, M.; Maier, H. Opportunities for Alternative Fuel Load Reduction Approaches—Summary Report, Mechanical Fuel Load Reduction Utilisation Project; Bushfire and Natural Hazards CRC: Melbourne, Australia, 2022; Available online: https://www.naturalhazards.com.au/crc-collection/downloads/opportunities_for_alternative_fuel_load_reduction_approaches.pdf (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Kim, K.; Spirandelli, D.; Rother, D.; Yamashita, E.; Toner, M. Tracking wildfire risk to California railroads: Integrating environmental data and railway operations. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2025, 32, 101526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackwood, L.; Renaud, F.G. Barriers and tools for implementing Nature-based solutions for rail climate change adaptation. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2022, 113, 103529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackwood, L.; Renaud, F.G.; Gillespie, S. Rail industry knowledge, experience and perceptions on the use of nature-based solutions as climate change adaptation measures in Australia and the United Kingdom. Environ. Res. Infrastruct. Sustain. 2023, 3, 045011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifert, L.; Heffer Flaata, E.; Conevski, S.; Jessen Graae, B.; Machí Castañer, C.; Canga, E.; Hartl, M.; Wirth, M.; Kuzmanić, T.; Barrios-Crespo, E.; et al. Nature-based solutions for climate-resilient infrastructure: Insights from infrastructure managers across Europe. Infrastructures 2026. submitted. [Google Scholar]

- Szymczak, S.; Bott, F.; Babeck, P.; Frick, A.; Stöckigt, B.; Wagner, K. Estimating the hazard of tree fall along railway lines: A new GIS tool. Nat. Hazards 2022, 112, 2237–2258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymczak, S.; Bott, F.; von den Driesch, F. Gefahrenhinweiskarten als Tool der Klimafolgenanpassung im Schienenverkehr. gis.Science 2025, 1, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenack, K.; Stecker, R.; Reckien, D.; Hoffmann, E. Adaptation to climate change in the transport sector: A review of actions and actors. Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Change 2012, 17, 451–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolte, R.; Behrendt, S.; Magro, M. UIC Guideline for Integrated Vegetation Management—Part A; International Union of Railways (UIC): Paris, France, 2018; Available online: https://uic.org/IMG/pdf/herbie_project_-_part_a.pdf (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- Lindgren, J.; Jonsson, D.K.; Carlsson-Kanyama, A. Climate Adaptation of Railways: Lessons from Sweden. Eur. J. Transp. Infrastruct. Res. 2009, 9, 164–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frick, A.; Wagner, K.; Stöckigt, B. Sensitivitätsanalyse Vegetation Entlang der Bundesverkehrswege Bezüglich Sturmwurfgefahren und Böschungsbränden. In DZSF-Forschungsberichte; Deutsches Zentrum für Schienenverkehrsforschung beim Eisenbahn-Bundesamt: Dresden, Germany, 2023; 127p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, S.J.; Anderson, R.P.; Schapire, R.E. Maximum entropy modelling of species geographic distribution. Ecol. Model. 2006, 190, 231–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renner, I.W.; Elith, J.; Baddeley, A.; Fithian, W.; Hastie, T.; Phillips, S.J.; Popovic, G.; Warton, D.I. Point process models for presence-only analysis. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2015, 6, 366–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, P. Maximum entropy-based forest fire likelihood mapping: Analysing the trends, distribution, and drivers of forest fires in Sikkim Himalaya. Scand. J. For. Res. 2021, 36, 275–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenbahn-Bundesamt (EBA). GeoPortal des Eisenbahn-Bundesamtes. 2025. Available online: https://geoportal.eisenbahn-bundesamt.de (accessed on 6 September 2025).

- Nature-DEMO Project. Nature-Based Solutions for Demonstrating Climate-Resilient Critical Infrastructure (NATURE-DEMO). In Horizon Europe, Grant Agreement No. 101157448; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2024; Available online: https://nature-demo.eu/ (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Bundesamt für Naturschutz (BfN). Biogeografische Regionen und Naturräumliche Haupteinheiten Deutschlands. 2011. Available online: https://www.bfn.de/daten-und-fakten/biogeografische-regionen-und-naturraeumliche-haupteinheiten-deutschlands (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- Brasseur, G.P.; Jacob, D.; Schuck-Zöller, S. (Eds.) Klimawandel in Deutschland: Entwicklung, Folgen, Risiken und Perspektiven, 2nd ed.; Springer Spektrum: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutscher Wetterdienst (DWD). Climate Atlas. Available online: https://www.dwd.de/DE/klimaumwelt/klimaatlas/klimaatlas_node.html (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- Wittich, K.-P.; Böttcher, C.; Stammer, P.; Herbst, M. Calculating Fire Danger of Cured Grasslands in Temperate Climates: The Elements of the Grassland Fire Index (GLFI). Int. J. Wildland Fire 2023, 32, 1212–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuppelwieser, H. Vegetation Control as Part of Environment Strategy of Swiss Federal Railways. Jpn. Railw. Transp. Rev. 1998, 16, 48–50. Available online: https://www.ejrcf.or.jp/jrtr/jrtr17/pdf/f08_helmut.pdf (accessed on 8 September 2025).

- Bukowski, C.J.; Nowak, C.A.; Engelman, H.M.; Ballard, B.D.; Boley, J.D. Alternatives for Treating Roadside Right-of-Way Vegetation: Literature Review and Annotated Bibliography; Prepared for New York State Department of Transportation; State University of New York, College of Environmental Science and Forestry: Syracuse, NY, USA, 2005. Available online: https://www.dot.ny.gov/divisions/engineering/environmental-analysis/repository/c-02-09-1.pdf (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Hansen, P.K.; Kristoffersen, P.; Kristensen, K. Strategies for non-chemical weed control on public paved areas in Denmark. Pest Manag. Sci. 2004, 60, 600–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archut, C.; Jendrny, N.; Schulte-Marxloh, A.; Eberius, M.; Conrath, U.; Schindler, C. Experimental Comparison of Herbicide-Free Methods for Weed Management on Railway Tracks. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 72, 1169–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyburski, Ł.; Szczygieł, R. Rules for the construction of firebreaks along public roads in selected European countries. Folia For. Pol. 2023, 65, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, A. Sprinkler Systems for the Protection of Buildings from Wildfire. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Wollongong, Wollongong, Australia, 2019. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10779/uow.27667539.v1 (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Pellizzaro, G.; Duce, P.; Ventura, A.; Zara, P. Seasonal Variations of Live Moisture Content and Ignitability in Shrubs of the Mediterranean Basin. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2007, 16, 633–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grootemaat, S.; Wright, I.J.; van Bodegom, P.M.; Cornelissen, J.H.C.; Cornwell, W.K. Burn or Rot: Leaf Traits Explain Why Flammability and Decomposability Are Decoupled across Species. Funct. Ecol. 2015, 29, 1486–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwilk, D.W. Dimensions of plant flammability. New Phytol. 2015, 206, 486–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popović, Z.; Bojović, S.; Marković, M.; Cerdà, A. Tree species flammability based on plant traits: A synthesis. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 795, 149625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jurdao, S.; Chuvieco, E.; Arevalillo, J.M. Modelling Fire Ignition Probability from Satellite Estimates of Live Fuel Moisture Content. Fire Ecol. 2012, 8, 77–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, F.X.; Tudela, A.; Sebastià, M.T. Modeling moisture content in shrubs to predict fire risk in Catalonia (Spain). Agric. For. Meteorol. 2003, 116, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, J.E.; Cawson, J.G.; Filkov, A.I.; Penman, T.D. Leaf traits predict global patterns in the structure and flammability of forest litter beds. J. Ecol. 2020, 109, 1344–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, E.; Dupuy, J.-L.; Pimont, F.; Guijarro, M.; Hernando, C.; Linn, R. Fuel bulk density and fuel moisture content effects on fire rate of spread: A comparison between FIRETEC model predictions and experimental results in shrub fuels. J. Fire Sci. 2012, 30, 27–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahale, A.; Ferguson, S.; Shotorban, B.; Mahalingam, S. Effects of Distribution of Bulk Density and Moisture Content on Shrub Fires. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2013, 22, 625–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Mahalingam, S.; Weise, D.R. Experimental Investigation of Fire Propagation in Single Live Shrubs. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2017, 26, 58–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plucinski, M.P.; Anderson, W.R. Laboratory Determination of Factors Influencing Successful Point Ignition in the Litter Layer of Shrubland Vegetation. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2008, 17, 628–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganteaume, A.; Romero, B.; Fernandez, C.; Ormeño, E.; Lecareux, C. Volatile and semi-volatile terpenes impact leaf flammability: Differences according to the level of terpene identification. Chemoecology 2021, 31, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, F.; Carmona, C.; Hernández, C.; Toledo, M.; Arriagada, A.; Espinoza, L.; Bergmann, J.; Taborga, L.; Yáñez, K.; Carrasco, Y.; et al. Drivers of flammability of Eucalyptus globulus Labill leaves: Terpenes, essential oils, and moisture content. Forests 2022, 13, 908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, F.; Espinoza, L.; Carmona, C.; Blackhall, M.; Quintero, C.; Ocampo-Zuleta, K.; Paula, S.; Madrigal, J.; Guijarro, M.; Carrasco, Y.; et al. Unraveling the chemistry of plant flammability: Exploring the role of volatile secondary metabolites beyond terpenes. For. Ecol. Manag. 2024, 572, 122269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nezval, V.; Andrášik, R.; Bíl, M. Vegetation fires along the Czech rail network. Fire Ecol. 2022, 18, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castañer, L.M.; Bertino, G.; Findlay, S.; Wirth, M.; Canga, E.; Kuzmanić, T.; Mikoš, M.; Seifert, L.; Ionescu, F.D.; Kuschel, E.; et al. Integrated Spatial Planning Design with NbS for Critical Infrastructure Protection against Multiple Hazards Driven by Climate Change. Infrastructures 2026. submitted. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J.D.; Putz, F.E.; Van Holsbeeck, S. Green Firebreaks: Potential to Proactively Complement Wildfire Management. Fire 2025, 8, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Alam, M.A.; Perry, G.L.W.; Paterson, A.M.; Wyse, S.V.; Curran, T.J. Green firebreaks as a management tool for wildfires: Lessons from China. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 233, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molina, J.R.; Lora, A.; Prades, C.; Silva, F.R.Y. Roadside vegetation planning and conservation: New approach to prevent and mitigate wildfires based on fire ignition potential. For. Ecol. Manag. 2019, 444, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drexler, S.; Gensior, A.; Don, A. Carbon sequestration in hedgerow biomass and soil in the temperate climate zone. Reg. Environ. Change 2021, 21, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, T.; Kahler, J.; Duthweiler, S.; Winter, S. Schlussbericht FireSafeGreen; Technische Universität München: Munich, Germany, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoerbinger, S.; Obriejetan, M.; Rauch, H.P.; Immitzer, M. Assessment of safety-relevant woody vegetation structures along railway corridors. Ecol. Eng. 2020, 158, 106048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powrie, W.; Smethurst, J. Climate and Vegetation Impacts on Infrastructure Cuttings and Embankments. In Proceedings of the 8th International Congress on Environmental Geotechnics (ICEG 2018), Hangzhou, China, 28–30 October 2018; Zhan, L., Chen, Y., Bouazza, A., Eds.; Environmental Science and Engineering. Springer: Singapore, 2019; Volume 1, pp. 128–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DB. DB-RIL 882 Landschaftsplanung und Vegetationskontrolle, Version 3.0; Internal guideline, not publicly available; Deutsche Bahn AG: Berlin, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Bentrup, G. Conservation Buffers—Design Guidelines for Buffers, Corridors, and Greenways; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Southern Research Station: Asheville, NC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punetha, P.; Samanta, M.; Sarkar, S. Bioengineering as an Effective and Ecofriendly Soil Slope Stabilization Method: A Review. In Landslides: Theory, Practice and Modelling; Pradhan, S., Vishal, V., Singh, T., Eds.; Advances in Natural and Technological Hazards Research; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 50, pp. 201–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, C.; Bhattacharya, S. Landslides and Erosion Control Measures by Vetiver System. In Disaster Risk Governance in India and Cross Cutting Issues; Pal, I., Shaw, R., Eds.; Disaster Risk Reduction; Springer: Singapore, 2018; pp. 387–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadzadeh, S.; Scholz, T.; Symmank, L. Bridging Ecology and Infrastructure: Evaluating the Integrated Benefits of Nature-Based Solutions. In Proceedings of the 3rd Conference of the European Association on Quality Control of Bridges and Structures (EUROSTRUCT 2025), Dublin, Ireland, 8 September 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Kuschel, E.; Obriejetan, M.; Kuzmanić, T.; Mikoš, M.; Seifert, L.; Conevski, S.; Wirth, M.; Canga, E.; Fernandes, S.; Hübl, J.; et al. Hazard Mitigation Profiling: A Systematic Approach for Strategic Nature-Based Solution Deployment. Manuscript submitted for publication. Special Issue: Nature-Based Solutions and Resilience of Infrastructure Systems. Infrastructures 2025, 10, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, J.R.; Martín, T.; Silva, F.R.Y.; Herrera, M.Á. The ignition index based on flammability of vegetation improves planning in the wildland-urban interface: A case study in Southern Spain. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2016, 158, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grootemaat, S.; Wright, I.J.; van Bodegom, P.M.; Cornelissen, J.H.C. Scaling up flammability from individual leaves to fuel beds. Oikos 2017, 126, 1428–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyšek, P.; Hulme, P.E.; Simberloff, D.; Bacher, S.; Blackburn, T.M.; Carlton, J.T.; Dawson, W.; Essl, F.; Foxcroft, L.C.; Genovesi, P.; et al. Scientists’ warning on invasive alien species. Biol. Rev. 2020, 95, 1511–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, S.; Strauss, A.; Kuschel, E.; Obriejetan, M.; Stangl, R.; Hübl, J.; Ionescu, F.D.; Bigaj-van Vliet, A.; Matos, J. Resilience-Oriented Extension of the RAMSHEEP Framework to Address Natural Hazards through Nature-Based Solutions: Insights from an Alpine Infrastructure Study. Infrastructures 2025. accepted. [Google Scholar]

| Embankment-Fire Susceptibility Class | Segments | Track Length (km) | % of Total | Site A (km) | Site B (km) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Very low | 1677 | 765.4 | 48.8 | 5.0 | 1.7 |

| Low | 1335 | 605.2 | 38.6 | 13.0 | 1.5 |

| Medium | 418 | 180.0 | 11.5 | 11.1 | 4.0 |

| High | 43 | 16.3 | 1.0 | 2.5 | 2.5 |

| Very high | 8 | 1.9 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 1.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Symmank, L.; Mohammadzadeh, S.; Szymczak, S. Embankment Fires on Railways—Where and How to Mitigate? Infrastructures 2025, 10, 337. https://doi.org/10.3390/infrastructures10120337

Symmank L, Mohammadzadeh S, Szymczak S. Embankment Fires on Railways—Where and How to Mitigate? Infrastructures. 2025; 10(12):337. https://doi.org/10.3390/infrastructures10120337

Chicago/Turabian StyleSymmank, Lars, Shahriar Mohammadzadeh, and Sonja Szymczak. 2025. "Embankment Fires on Railways—Where and How to Mitigate?" Infrastructures 10, no. 12: 337. https://doi.org/10.3390/infrastructures10120337

APA StyleSymmank, L., Mohammadzadeh, S., & Szymczak, S. (2025). Embankment Fires on Railways—Where and How to Mitigate? Infrastructures, 10(12), 337. https://doi.org/10.3390/infrastructures10120337