Smart Surveillance of Structural Health: A Systematic Review of Deep Learning-Based Visual Inspection of Concrete Bridges Using 2D Images

Abstract

1. Introduction

- How have deep learning-based visual inspection methods for concrete bridge surface defects evolved since 2018 in terms of: (a) defect types, and (b) computer-vision tasks (classification, object detection, segmentation, and hybrid methods)?

- For each main task (classification, object detection, segmentation), which families of deep learning models are most commonly used for detecting concrete bridge defects, and what trade-offs do they show between performance (e.g., accuracy, F1-score, mAP, mIoU) and computational efficiency (e.g., inference time)?

- What are the main characteristics and limitations of the datasets used to train and validate deep learning models for concrete bridge visual inspection (e.g., dataset size, defect classes, annotation level)?

2. Background on Deep Learning

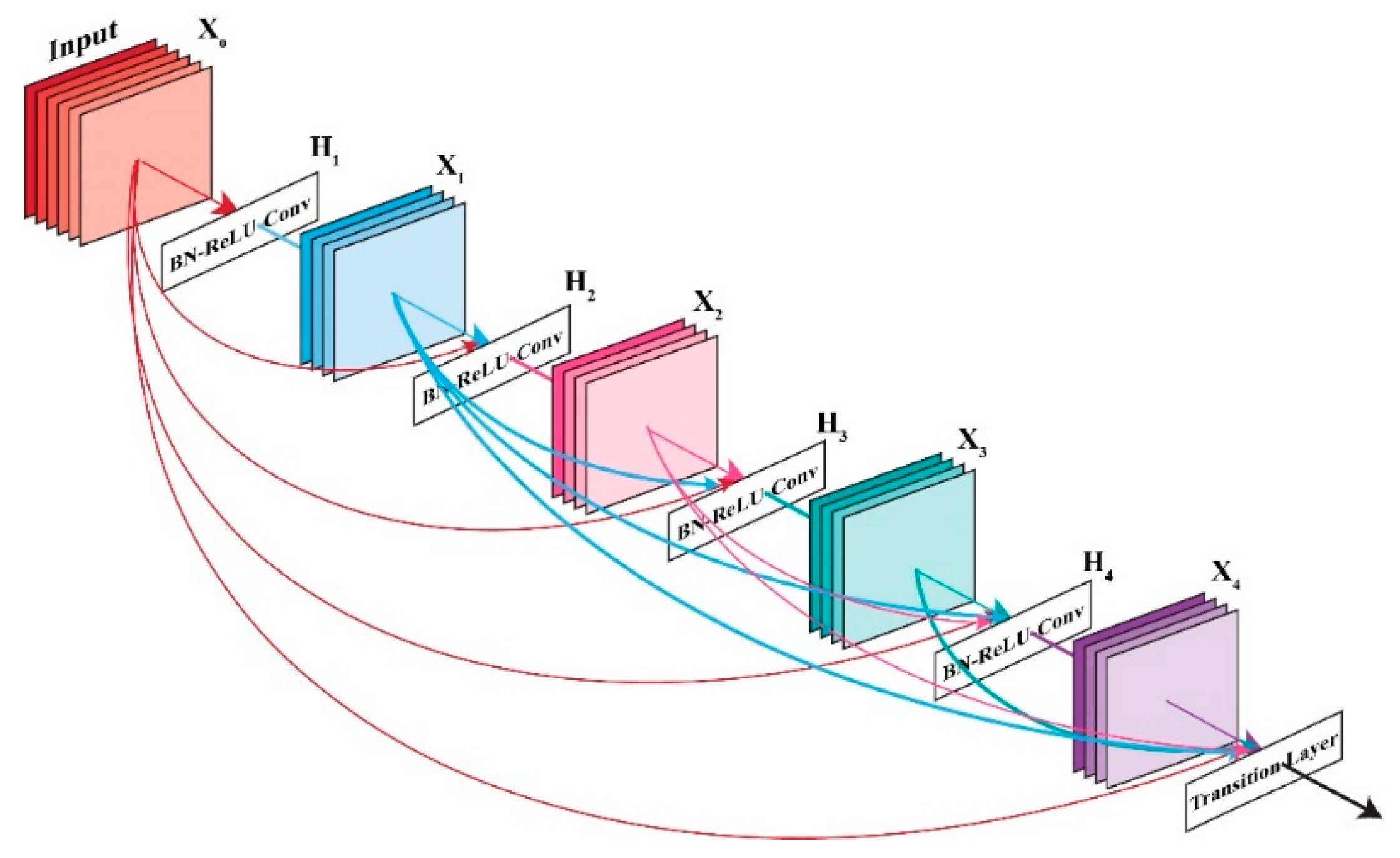

2.1. Deep Learning-Based Image Classification Algorithms

2.2. Deep Learning-Based Image Segmentation Algorithms

2.3. Deep Learning-Based Object Detection Algorithms

2.4. Evaluation Metrics

- Accuracy: Classification algorithms don’t always predict correctly, and their performance is measured according to their true and false predictions. True positives (TP) are when the model accurately predicts the positive class, while true negatives (TN) are when it accurately predicts the negative class. False positives (FP) happen when the model wrongly predicts the negative class as positive, and false negatives (FN) occur when the model incorrectly predicts the positive class as negative. Accuracy is the ratio of correct predictions to the total predictions, and mean accuracy is the average of accuracy across multiple model runs.

- Precision:

- Recall (Sensitivity):

- F1 Score:

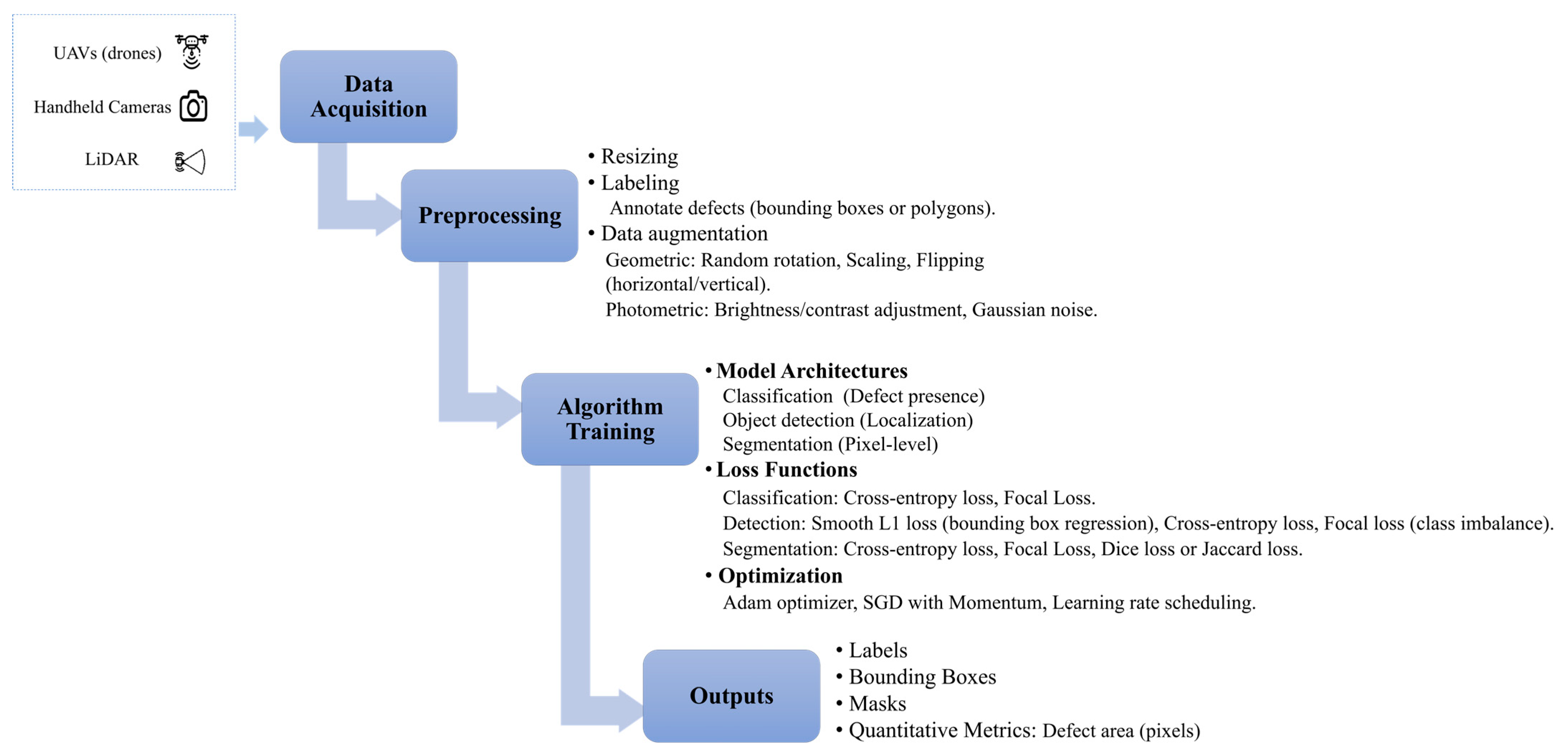

3. Research Methodology

4. Analysis and Results

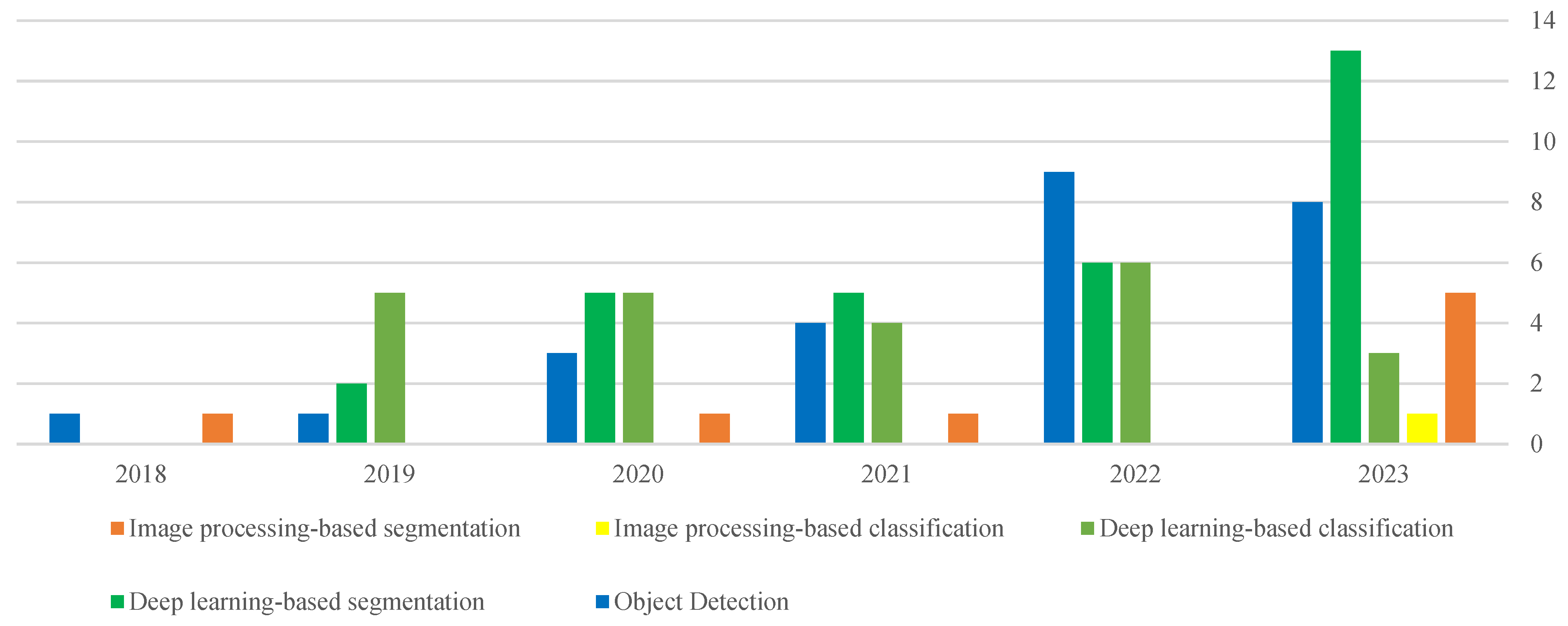

4.1. Descriptive Analysis

4.2. Content Analysis

4.2.1. Image Classification

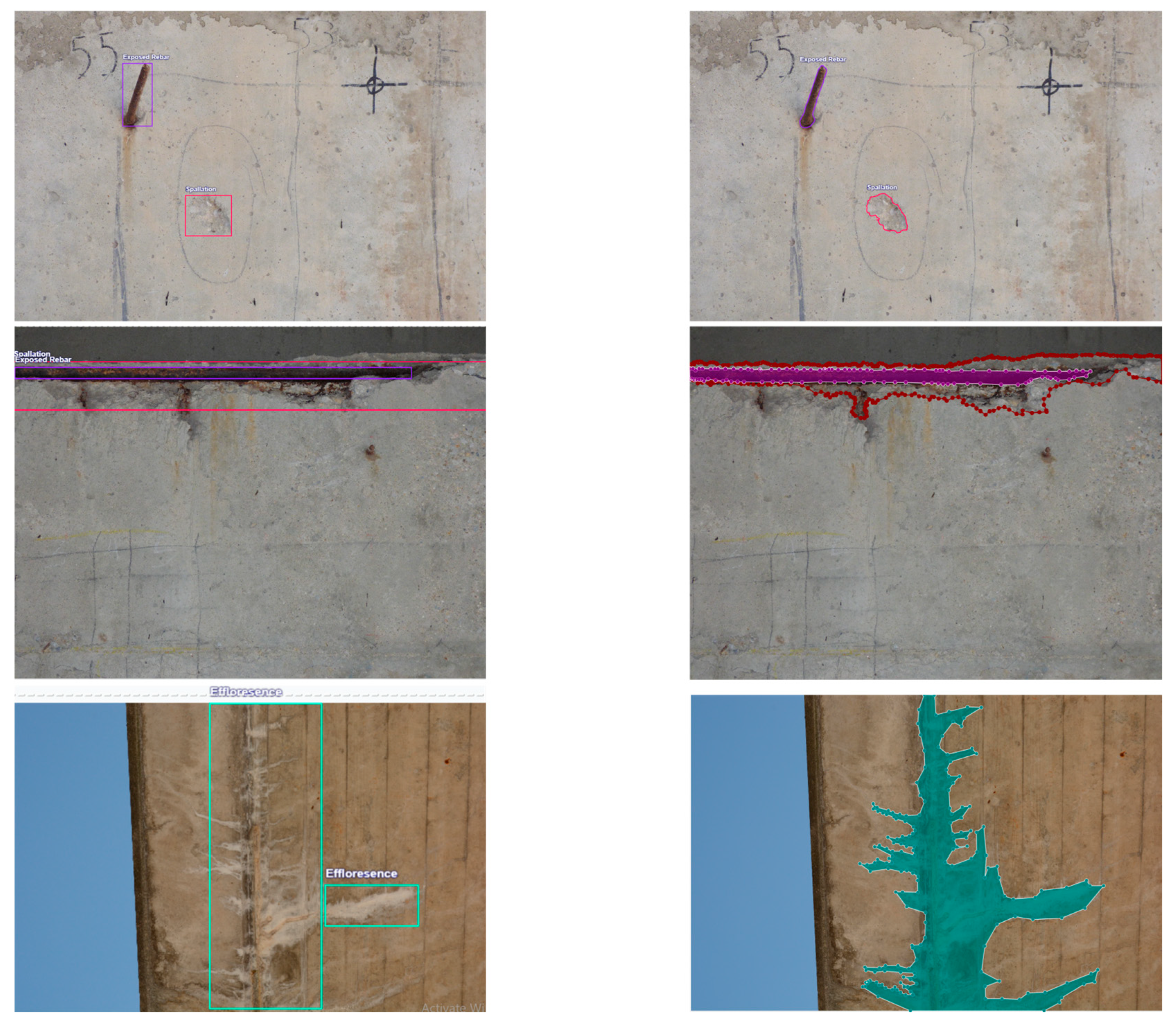

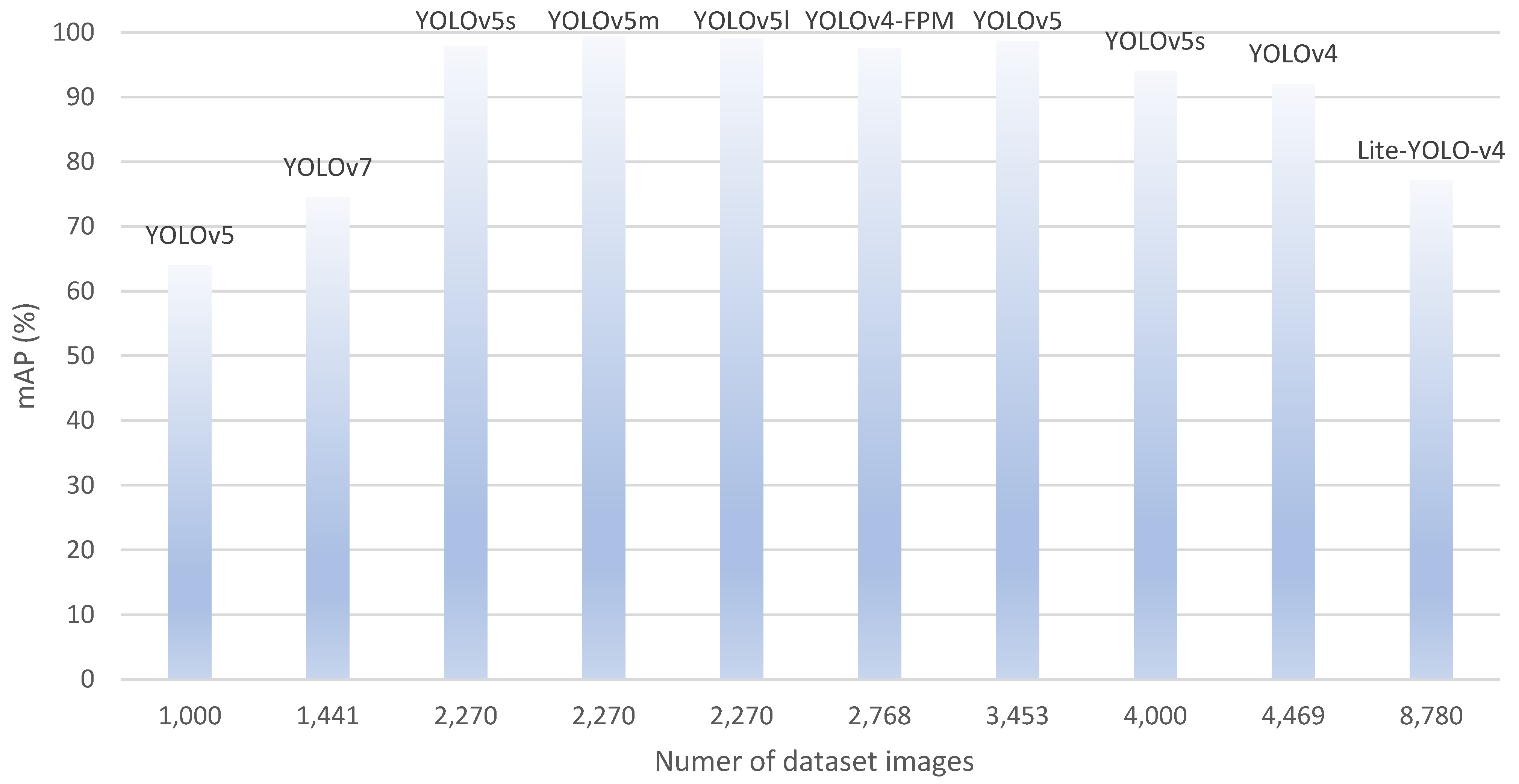

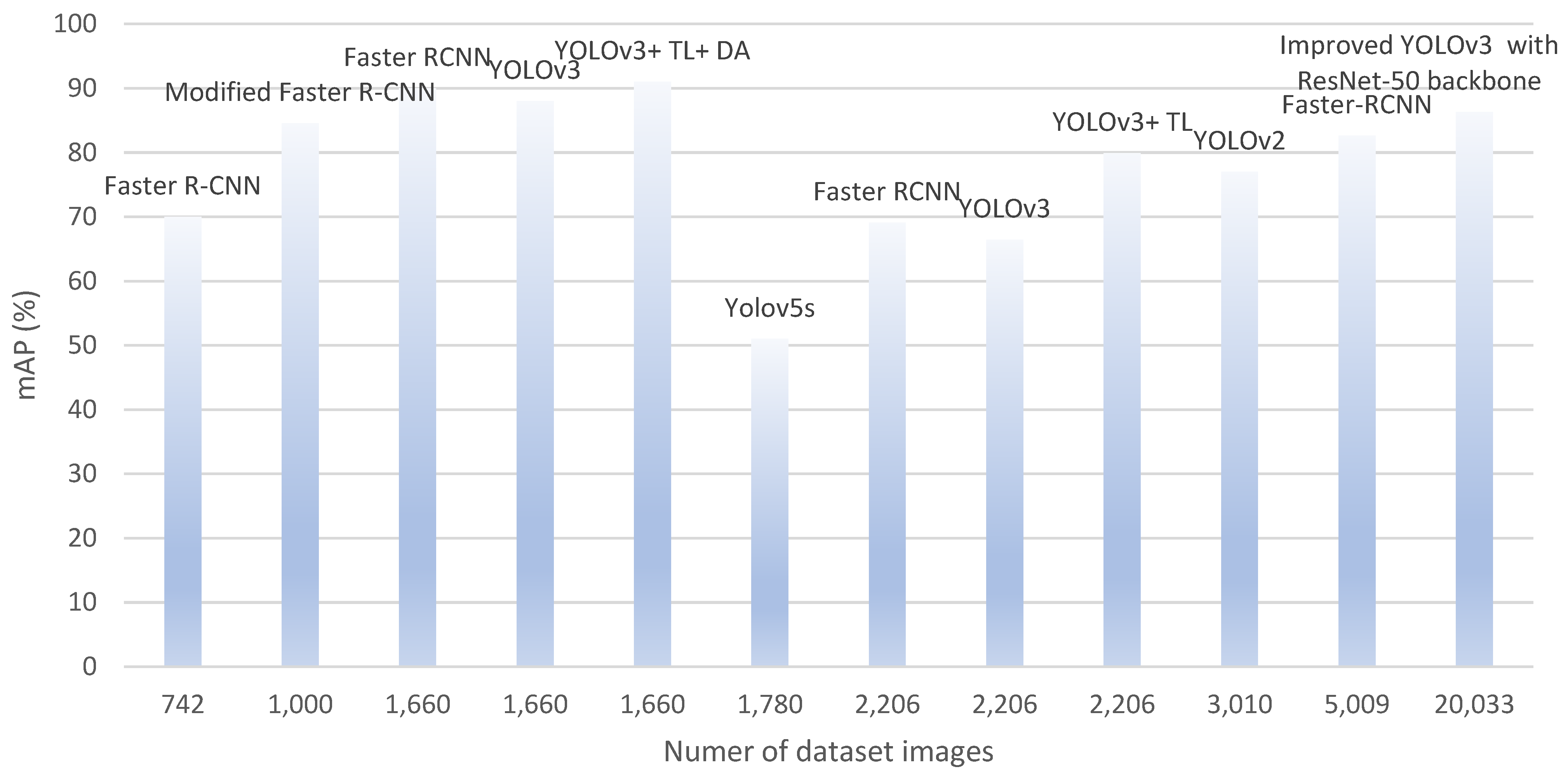

4.2.2. Object Detection

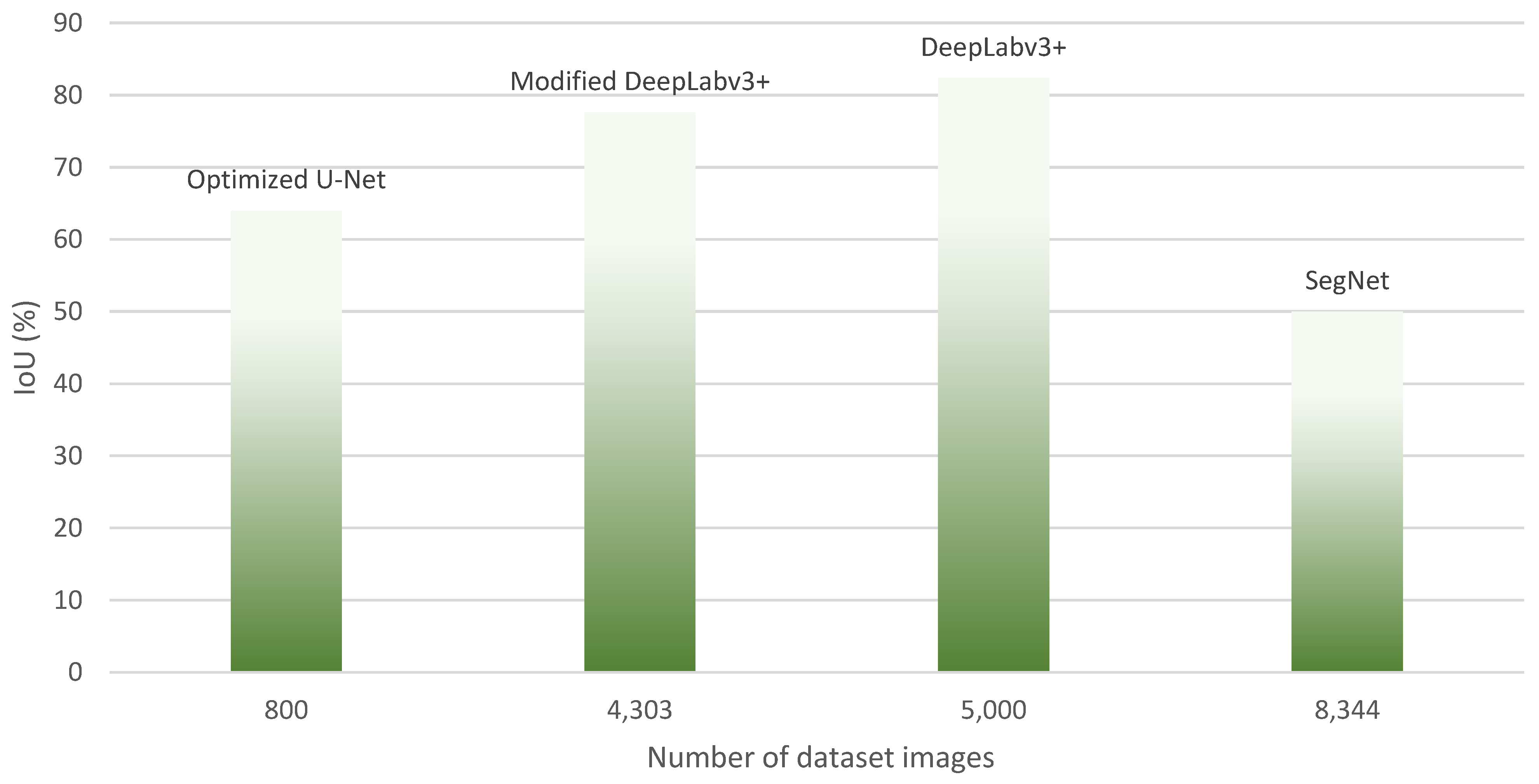

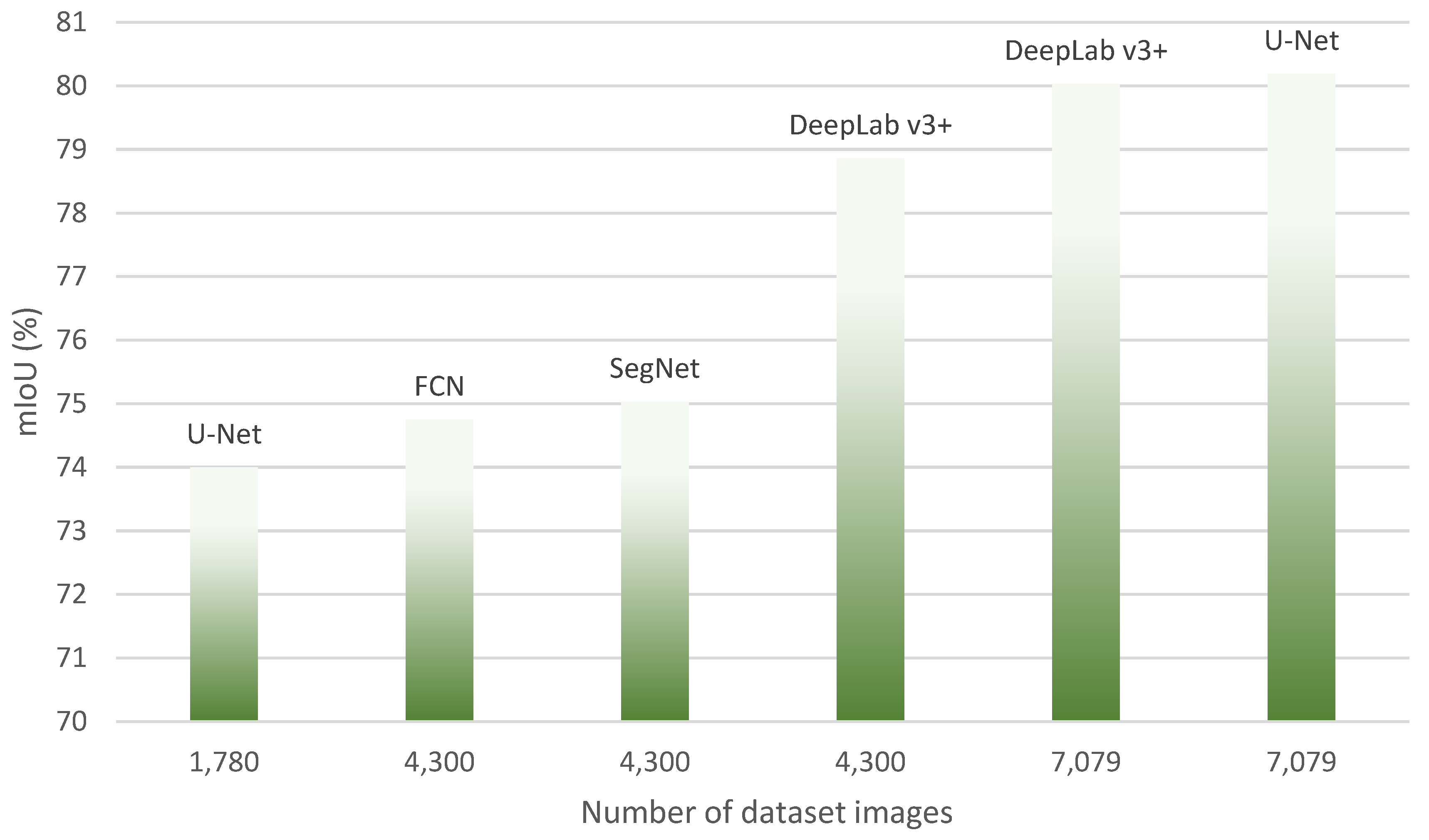

4.2.3. Image Segmentation

4.2.4. Hybrid Methods

5. Discussion and Comparison of Algorithms

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Studies | Study Design | Data Handling | Reporting Transparency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chen [38] | low | low | Some concerns |

| Hüthwohl et al. [42] | low | low | low |

| Zhu et al. [5] | low | low | low |

| Mundt et al. [44] | low | low | low |

| Zoubir et al. [49] | low | low | low |

| Bukhsh et al. [48] | low | low | low |

| Kruachottikul et al. [50] | low | Some concerns | low |

| Xu et al. [36] | low | low | low |

| Zhang et al. [37] | low | low | low |

| Cardellicchio et al. [45] | low | Some concerns | low |

| Trach [46] | low | Some concerns | low |

| Chen et al. [41] | low | low | low |

| Zhang et al. [54] | low | low | low |

| Abubakr et al. [47] | low | low | low |

| Alfaz et al. [39] | low | Some concerns | low |

| Aliyari et al. [51] | low | low | low |

| Li et al. [40] | low | Some concerns | low |

| Murao et al. [55] | Some concerns | Some concerns | Some concerns |

| Yu et al. [56] | low | low | low |

| Li et al. [57] | low | low | low |

| Deng et al. [58] | low | Some concerns | low |

| Ji [59] | low | Some concerns | low |

| Deng et al. [71] | low | Some concerns | low |

| Ruggieri et al. [60] | low | low | low |

| Zhang et al. [61] | low | low | low |

| Liu et al. [62] | low | Some concerns | low |

| Yamane et al. [63] | low | low | low |

| Teng et al. [64] | low | low | low |

| Hong et al. [70] | low | low | low |

| Yu et al. [65] | low | low | low |

| Gan et al. [68] | low | low | Some concerns |

| Lin et al. [67] | low | low | low |

| Ngo et al. [74] | low | low | Some concerns |

| Lu et al. [75] | low | low | Some concerns |

| Ruggieri et al. [72] | low | low | low |

| Rubio et al. [81] | low | low | low |

| Lopez Droguett et al. [82] | low | Some concerns | low |

| Merkle et al. [83] | low | low | low |

| Fukuoka and Fujiu [85] | low | low | low |

| Li et al. [86] | low | Some concerns | low |

| Yamane et al. [87] | low | low | Some concerns |

| Xu et al. [88] | low | low | low |

| Bae et al. [89] | low | low | Some concerns |

| Deng et al. [90] | low | low | low |

| Munawar et al. [92] | low | Some concerns | low |

| Li et al. [106] | low | low | Some concerns |

| Fu et al. [91] | low | Some concerns | low |

| Qiao et al. [93] | low | Some concerns | low |

| Jin et al. [95] | low | low | low |

| Subedi et al. [96] | low | low | low |

| Ayele et al. [97] | low | Some concerns | Some concerns |

| Wang et al. [98] | low | low | low |

| Montes et al. [99] | low | Some concerns | low |

| Artus et al. [100] | low | Some concerns | low |

| Borin and Cavazzini [101] | low | Some concerns | Some concerns |

| Jang et al. [102] | low | low | low |

| McLaughlin et al. [103] | low | low | low |

| Ye et al. [104] | low | low | low |

| Shen et al. [105] | low | low | low |

| Na and Kim [84] | low | low | Some concerns |

| Peng et al. [112] | low | Some concerns | low |

| Flah et al. [113] | low | low | low |

| Kim et al. [114] | low | low | low |

| Liang [115] | low | low | low |

| Mirzazade et al. [116] | low | Some concerns | low |

| Kun et al. [117] | low | Some concerns | low |

| Kim et al. [118] | low | Some concerns | Some concerns |

| Yu et al. [128] | low | low | low |

| Ni et al. [119] | low | low | low |

| Jiang et al. [120] | low | low | low |

| Tran et al. [121] | low | Some concerns | low |

| Kao et al. [122] | low | Some concerns | low |

| Ma et al. [123] | low | low | Some concerns |

| Inam et al. [124] | low | Some concerns | low |

| Zakaria et al. [125] | low | low | low |

| Meng et al. [126] | low | low | low |

| Zhang et al. [80] | low | Some concerns | Some concerns |

References

- Munawar, H.S.; Hammad, A.W.; Haddad, A.; Soares, C.A.P.; Waller, S.T. Image-based crack detection methods: A review. Infrastructures 2021, 6, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iron, A.; Institute, S. Steel Bridge Construction: Myths & Realities; American Iron and Steel Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Koch, C.; Georgieva, K.; Kasireddy, V.; Akinci, B.; Fieguth, P. A review on computer vision based defect detection and condition assessment of concrete and asphalt civil infrastructure. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2015, 29, 196–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.-K.; Jang, G.; Oh, S.; Lee, J.H.; Yi, B.-J.; Moon, Y.S.; Lee, J.S.; Choi, Y. Bridge inspection robot system with machine vision. Autom. Constr. 2009, 18, 929–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Zhang, C.; Qi, H.; Lu, Z. Vision-based defects detection for bridges using transfer learning and convolutional neural networks. Struct. Infrastruct. Eng. 2020, 16, 1037–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, B.F., Jr.; Hoskere, V.; Narazaki, Y. Advances in computer vision-based civil infrastructure inspection and monitoring. Engineering 2019, 5, 199–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.-M.; Kee, S.-H.; Pathan, A.-S.K.; Nahid, A.-A. Image Processing Techniques for Concrete Crack Detection: A Scientometrics Literature Review. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 2400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, K.; Kong, X.; Zhang, J.; Hu, J.; Li, J.; Tang, H. Computer vision-based bridge inspection and monitoring: A review. Sensors 2023, 23, 7863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Yuen, K.-V. Review of artificial intelligence-based bridge damage detection. Adv. Mech. Eng. 2022, 14, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzubaidi, L.; Zhang, J.; Humaidi, A.J.; Al-Dujaili, A.; Duan, Y.; Al-Shamma, O.; Santamaría, J.; Fadhel, M.A.; Al-Amidie, M.; Farhan, L. Review of deep learning: Concepts, CNN architectures, challenges, applications, future directions. J. Big Data 2021, 8, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulkarni, S.; Harnoorkar, S.; Pintelas, P. Comparative analysis of CNN architectures. Int. Res. J. Eng. Technol. 2020, 7, 1459–1464. [Google Scholar]

- Neu, D.A.; Lahann, J.; Fettke, P. A systematic literature review on state-of-the-art deep learning methods for process prediction. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2022, 55, 801–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.; Wang, Z.; Kuen, J.; Ma, L.; Shahroudy, A.; Shuai, B.; Liu, T.; Wang, X.; Wang, G.; Cai, J. Recent advances in convolutional neural networks. Pattern Recognit. 2018, 77, 354–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Hinton, G.E. Imagenet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2012, 25, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1409.1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Liu, Z.; Van Der Maaten, L.; Weinberger, K.Q. Densely connected convolutional networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 4700–4708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, A.G.; Zhu, M.; Chen, B.; Kalenichenko, D.; Wang, W.; Weyand, T.; Andreetto, M.; Adam, H. Mobilenets: Efficient convolutional neural networks for mobile vision applications. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1704.04861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chollet, F. Xception: Deep learning with depthwise separable convolutions. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 1251–1258. [Google Scholar]

- Gurita, A.; Mocanu, I.G. Image segmentation using encoder-decoder with deformable convolutions. Sensors 2021, 21, 1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, J.; Shelhamer, E.; Darrell, T. Fully convolutional networks for semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Boston, MA, USA, 7–12 June 2015; pp. 3431–3440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention–MICCAI 2015: 18th International Conference, Munich, Germany, 5–9 October 2015; part III 18. pp. 234–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.-C.; Papandreou, G.; Kokkinos, I.; Murphy, K.; Yuille, A.L. Semantic image segmentation with deep convolutional nets and fully connected crfs. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1412.7062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Gkioxari, G.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R. Mask r-cnn. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 2961–2969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girshick, R.; Donahue, J.; Darrell, T.; Malik, J. Rich feature hierarchies for accurate object detection and semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Columbus, OH, USA, 24–28 June 2014; pp. 580–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girshick, R. Fast r-cnn. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1504.08083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S. Faster r-cnn: Towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1506.01497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redmon, J. You only look once: Unified, real-time object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otsu, N. A threshold selection method from gray-level histograms. Automatica 1975, 11, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrmann, A.; König, M.; Koch, C.; Beetz, J. Building Information Modeling: Why? What? How? Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hüthwohl, P.; Borrmann, A.; Sacks, R. Integrating RC bridge defect information into BIM models. J. Comput. Civ. Eng. 2018, 32, 04018013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacks, R.; Eastman, C.; Lee, G.; Teicholz, P. BIM Handbook: A Guide to Building Information Modeling for Owners, Designers, Engineers, Contractors, and Facility Managers; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Cho, S. Automated vision-based detection of cracks on concrete surfaces using a deep learning technique. Sensors 2018, 18, 3452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasanna, P.; Dana, K.; Gucunski, N.; Basily, B. Computer-vision based crack detection and analysis. In Proceedings of the Sensors and Smart Structures Technologies for Civil, Mechanical, and Aerospace Systems 2012, San Diego, CA, USA, 12–15 March 2012; pp. 1143–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Canchila, C.; Song, W. Deep learning-based crack segmentation for civil infrastructure: Data types, architectures, and benchmarked performance. Autom. Constr. 2023, 146, 104678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Su, X.; Wang, Y.; Cai, H.; Cui, K.; Chen, X. Automatic bridge crack detection using a convolutional neural network. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 2867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Barri, K.; Babanajad, S.K.; Alavi, A.H. Real-time detection of cracks on concrete bridge decks using deep learning in the frequency domain. Engineering 2021, 7, 1786–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R. Migration learning-based bridge structure damage detection algorithm. Sci. Program. 2021, 2021, 1102521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfaz, N.; Hasnat, A.; Khan, A.M.R.N.; Sayom, N.S.; Bhowmik, A. Bridge crack detection using dense convolutional network (densenet). In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Computing Advancements, Dhaka, Bangladesh, 10–12 March 2022; pp. 509–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Xu, H.; Tian, X.; Wang, Y.; Cai, H.; Cui, K.; Chen, X. Bridge crack detection based on SSENets. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 4230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Yao, H.; Fu, J.; Ng, C.T. The classification and localization of crack using lightweight convolutional neural network with CBAM. Eng. Struct. 2023, 275, 115291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hüthwohl, P.; Lu, R.; Brilakis, I. Multi-classifier for reinforced concrete bridge defects. Autom. Constr. 2019, 105, 102824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruachottikul, P.; Cooharojananone, N.; Phanomchoeng, G.; Chavarnakul, T.; Kovitanggoon, K.; Trakulwaranont, D.; Atchariyachanvanich, K. Bridge sub structure defect inspection assistance by using deep learning. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 10th International Conference on Awareness Science and Technology (iCAST), Morioka, Japan, 23–25 October 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mundt, M.; Majumder, S.; Murali, S.; Panetsos, P.; Ramesh, V. Meta-learning convolutional neural architectures for multi-target concrete defect classification with the concrete defect bridge image dataset. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Long Beach, CA, USA, 16–20 June 2019; pp. 11196–11205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardellicchio, A.; Ruggieri, S.; Nettis, A.; Patruno, C.; Uva, G.; Renò, V. Deep learning approaches for image-based detection and classification of structural defects in bridges. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Image Analysis and Processing, Lecce, Italy, 23–27 May 2022; pp. 269–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trach, R. A Model Classifying Four Classes of Defects in Reinforced Concrete Bridge Elements Using Convolutional Neural Networks. Infrastructures 2023, 8, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubakr, M.; Rady, M.; Badran, K.; Mahfouz, S.Y. Application of deep learning in damage classification of reinforced concrete bridges. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2024, 15, 102297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukhsh, Z.A.; Anžlin, A.; Stipanović, I. BiNet: Bridge Visual Inspection Dataset and Approach for Damage Detection. In Proceedings of the 1st Conference of the European Association on Quality Control of Bridges and Structures: EUROSTRUCT 2021, Padua, Italy, 29 August–1 September 2021; pp. 1027–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoubir, H.; Rguig, M.; El Aroussi, M.; Chehri, A.; Saadane, R.; Jeon, G. Concrete Bridge defects identification and localization based on classification deep convolutional neural networks and transfer learning. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 4882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruachottikul, P.; Cooharojananone, N.; Phanomchoeng, G.; Chavarnakul, T.; Kovitanggoon, K.; Trakulwaranont, D. Deep learning-based visual defect-inspection system for reinforced concrete bridge substructure: A case of Thailand’s department of highways. J. Civ. Struct. Health Monit. 2021, 11, 949–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliyari, M.; Droguett, E.L.; Ayele, Y.Z. UAV-based bridge inspection via transfer learning. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorafshan, S.; Thomas, R.J.; Maguire, M. SDNET2018: An annotated image dataset for non-contact concrete crack detection using deep convolutional neural networks. Data Brief 2018, 21, 1664–1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.-F.; Ma, W.-F.; Li, L.; Lu, C. Research on detection algorithm for bridge cracks based on deep learning. Acta Autom. Sin. 2019, 45, 1727–1742. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Ni, Y.-Q.; Jia, X.; Wang, Y.-W. Identification of concrete surface damage based on probabilistic deep learning of images. Autom. Constr. 2023, 156, 105141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murao, S.; Nomura, Y.; Furuta, H.; Kim, C.-W. Concrete crack detection using uav and deep learning. In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Applications of Statistics and Probability in Civil Engineering (ICASP), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 26–20 May 2019; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Z.; Shen, Y.; Shen, C. A real-time detection approach for bridge cracks based on YOLOv4-FPM. Autom. Constr. 2021, 122, 103514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Sun, H.; Song, T.; Zhang, T.; Meng, Q. A method of underwater bridge structure damage detection method based on a lightweight deep convolutional network. IET Image Process. 2022, 16, 3893–3909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Lu, Y.; Lee, V.C.-S. Imaging-based crack detection on concrete surfaces using You Only Look Once network. Struct. Health Monit. 2021, 20, 484–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, H. Development of an Autonomous Column-Climbing Robotic System for Real-time Detection and Mapping of Surface Cracks on Bridges. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE IAS Global Conference on Emerging Technologies (GlobConET), London, UK, 19–21 May 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggieri, S.; Cardellicchio, A.; Nettis, A.; Renò, V.; Uva, G. Using machine learning approaches to perform defect detection of existing bridges. Procedia Struct. Integr. 2023, 44, 2028–2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Chang, C.c.; Jamshidi, M. Concrete bridge surface damage detection using a single-stage detector. Comput.-Aided Civ. Infrastruct. Eng. 2020, 35, 389–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Gao, W.; Zhao, T.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Z. A Rapid Bridge Crack Detection Method Based on Deep Learning. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 9878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamane, T.; Chun, P.-J.; Honda, R. Detecting and localising damage based on image recognition and structure from motion, and reflecting it in a 3D bridge model. Struct. Infrastruct. Eng. 2022, 20, 594–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, S.; Liu, Z.; Li, X. Improved YOLOv3-based bridge surface defect detection by combining High-and low-resolution feature images. Buildings 2022, 12, 1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; He, S.; Liu, X.; Ma, M.; Xiang, S. Engineering-oriented bridge multiple-damage detection with damage integrity using modified faster region-based convolutional neural network. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2022, 81, 18279–18304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Yu, J.; Li, F.; Yang, R.; Wang, Y.; Peng, Z. Automatic bridge crack detection using Unmanned aerial vehicle and Faster R-CNN. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 362, 129659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.J.; Ibrahim, A.; Sarwade, S.; Golparvar-Fard, M. Bridge inspection with aerial robots: Automating the entire pipeline of visual data capture, 3D mapping, defect detection, analysis, and reporting. J. Comput. Civ. Eng. 2021, 35, 04020064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, L.; Liu, H.; Yan, Y.; Chen, A. Bridge bottom crack detection and modeling based on faster R-CNN and BIM. IET Image Process. 2023, 18, 664–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhejiang-Highway-Administration. JTG H10-2009: Technical Specification for Highway Maintenance. Available online: https://www.chinesestandard.net/PDF/BOOK.aspx/JTGH10-2009 (accessed on 5 November 2024).

- Hong, S.-S.; Hwang, C.-H.; Chung, S.-W.; Kim, B.-K. A deep-learning-based bridge damaged object automatic detection model using a bridge member model combination framework. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 12868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Lu, Y.; Lee, V.C.S. Concrete crack detection with handwriting script interferences using faster region-based convolutional neural network. Comput.-Aided Civ. Infrastruct. Eng. 2020, 35, 373–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggieri, S.; Cardellicchio, A.; Nettis, A.; Renò, V.; Uva, G. Using attention for improving defect detection in existing RC bridges. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 18994–19015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, B.; Nelson, J.; Hansen, T.; Solawetz, J. Roboflow, Version 1.0; Roboflow: Des Moines, IA, USA, 2022.

- Ngo, L.; Xuan, C.L.; Luong, H.M.; Thanh, B.N.; Ngoc, D.B. Designing image processing tools for testing concrete bridges by a drone based on deep learning. J. Inf. Telecommun. 2023, 7, 227–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, G.; He, X.; Wang, Q.; Shao, F.; Wang, J.; Zhao, X. MSCNet: A Framework With a Texture Enhancement Mechanism and Feature Aggregation for Crack Detection. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 26127–26139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, R.; Moselhi, O.; Bagchi, A. Image-based retrieval of concrete crack properties. In Proceedings of the ISARC International Symposium on Automation and Robotics in Construction, Eindhoven, The Netherlands, 26–29 June 2012; p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Y.; Zhang, X.; Chen, H.; Wang, Y.; Wu, H. A Bridge Damage Visualization Technique Based on Image Processing Technology and the IFC Standard. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivekananthan, V.; Vignesh, R.; Vasanthaseelan, S.; Joel, E.; Kumar, K.S. Concrete bridge crack detection by image processing technique by using the improved OTSU method. Mater. Today Proc. 2023, 74, 1002–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minaee, S.; Boykov, Y.; Porikli, F.; Plaza, A.; Kehtarnavaz, N.; Terzopoulos, D. Image segmentation using deep learning: A survey. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2021, 44, 3523–3542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Qian, S.; Tan, C. Automated bridge surface crack detection and segmentation using computer vision-based deep learning model. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2022, 115, 105225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio, J.J.; Kashiwa, T.; Laiteerapong, T.; Deng, W.; Nagai, K.; Escalera, S.; Nakayama, K.; Matsuo, Y.; Prendinger, H. Multi-class structural damage segmentation using fully convolutional networks. Comput. Ind. 2019, 112, 103121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez Droguett, E.; Tapia, J.; Yanez, C.; Boroschek, R. Semantic segmentation model for crack images from concrete bridges for mobile devices. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part O J. Risk Reliab. 2022, 236, 570–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merkle, D.; Solass, J.; Schmitt, A.; Rosin, J.; Reiterer, A.; Stolz, A. Semi-automatic 3D crack map generation and width evaluation for structural monitoring of reinforced concrete structures. J. Inf. Technol. Constr. 2023, 28, 774–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na, Y.-H.; Kim, D.-K. Deep Learning Strategy for UAV-Based Multi-Class Damage Detection on Railway Bridges Using U-Net with Different Loss Functions. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 8719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuoka, T.; Fujiu, M. Detection of Bridge Damages by Image Processing Using the Deep Learning Transformer Model. Buildings 2023, 13, 788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Fang, Z.; Mohammed, A.M.; Liu, T.; Deng, Z. Automated Bridge Crack Detection Based on Improving Encoder–Decoder Network and Strip Pooling. J. Infrastruct. Syst. 2023, 29, 04023004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamane, T.; Chun, P.j.; Dang, J.; Honda, R. Recording of bridge damage areas by 3D integration of multiple images and reduction of the variability in detected results. Comput.-Aided Civ. Infrastruct. Eng. 2023, 38, 2391–2407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Fan, Y.; Li, H. Lightweight semantic segmentation of complex structural damage recognition for actual bridges. Struct. Health Monit. 2023, 22, 3250–3269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, H.; Jang, K.; An, Y.-K. Deep super resolution crack network (SrcNet) for improving computer vision–based automated crack detectability in in situ bridges. Struct. Health Monit. 2021, 20, 1428–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, W.; Mou, Y.; Kashiwa, T.; Escalera, S.; Nagai, K.; Nakayama, K.; Matsuo, Y.; Prendinger, H. Vision based pixel-level bridge structural damage detection using a link ASPP network. Autom. Constr. 2020, 110, 102973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.; Meng, D.; Li, W.; Wang, Y. Bridge crack semantic segmentation based on improved Deeplabv3+. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munawar, H.S.; Ullah, F.; Shahzad, D.; Heravi, A.; Qayyum, S.; Akram, J. Civil infrastructure damage and corrosion detection: An application of machine learning. Buildings 2022, 12, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, W.; Ma, B.; Liu, Q.; Wu, X.; Li, G. Computer vision-based bridge damage detection using deep convolutional networks with expectation maximum attention module. Sensors 2021, 21, 824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddhartha, V.R. Bridge Crack Detection Using Horse Herd Optimization Algorithm. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Smart Electronics and Communication (ICOSEC), Trichy, India, 20–22 September 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, T.; Ye, X.; Li, Z. Establishment and evaluation of conditional GAN-based image dataset for semantic segmentation of structural cracks. Eng. Struct. 2023, 285, 116058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subedi, A.; Tang, W.; Mondal, T.G.; Wu, R.-T.; Jahanshahi, M.R. Ensemble-based deep learning for autonomous bridge component and damage segmentation leveraging Nested Reg-UNet. Smart Struct. Syst. 2023, 31, 335–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayele, Y.Z.; Aliyari, M.; Griffiths, D.; Droguett, E.L. Automatic crack segmentation for UAV-assisted bridge inspection. Energies 2020, 13, 6250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Lei, Y.; Yang, X.; Zhang, F. A refinement network embedded with attention mechanism for computer vision based post-earthquake inspections of railway viaduct. Eng. Struct. 2023, 279, 115572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montes, K.; Zhang, M.; Liu, J.; Hajmousa, L.; Chen, Z.; Dang, J. Integrated 3D Structural Element and Damage Identification: Dataset and Benchmarking. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Experimental Vibration Analysis for Civil Engineering Structures, Milan, Italy, 30 August–1 September 2023; pp. 712–720. [Google Scholar]

- Artus, M.; Alabassy, M.S.H.; Koch, C. A BIM Based Framework for Damage Segmentation, Modeling, and Visualization Using IFC. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 2772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borin, P.; Cavazzini, F. Condition assessment of RC bridges. Integrating machine learning, photogrammetry and BIM. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2019, 42, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, K.; An, Y.K.; Kim, B.; Cho, S. Automated crack evaluation of a high-rise bridge pier using a ring-type climbing robot. Comput.-Aided Civ. Infrastruct. Eng. 2021, 36, 14–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, E.; Charron, N.; Narasimhan, S. Automated defect quantification in concrete bridges using robotics and deep learning. J. Comput. Civ. Eng. 2020, 34, 04020029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.W.; Ma, S.Y.; Liu, Z.X.; Ding, Y.; Li, Z.X.; Jin, T. Post-earthquake damage recognition and condition assessment of bridges using UAV integrated with deep learning approach. Struct. Control Health Monit. 2022, 29, e3128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Q.; Xiao, B.; Mi, H.; Yu, J.; Xiao, L. Adaptive Learning Filters–Embedded Vision Transformer for Pixel-Level Segmentation of Low-Light Concrete Cracks. J. Perform. Constr. Facil. 2025, 39, 04025007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Liu, Q.; Zhao, S.; Qiao, W.; Ren, X. Automatic crack recognition for concrete bridges using a fully convolutional neural network and naive Bayes data fusion based on a visual detection system. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2020, 31, 075403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Li, H.; Yu, Y.; Luo, X.; Huang, T.; Yang, X. Automatic pixel-level crack detection and measurement using fully convolutional network. Comput.-Aided Civ. Infrastruct. Eng. 2018, 33, 1090–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narazaki, Y.; Hoskere, V.; Yoshida, K.; Spencer, B.F.; Fujino, Y. Synthetic environments for vision-based structural condition assessment of Japanese high-speed railway viaducts. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2021, 160, 107850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Li, B.; Li, W.; Liu, Z.; Yang, G.; Xiao, J. A robotic system towards concrete structure spalling and crack database. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Biomimetics (ROBIO), Macau, China, 5–8 December 2017; pp. 1276–1281. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Y.; Cui, L.; Qi, Z.; Meng, F.; Chen, Z. Automatic road crack detection using random structured forests. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2016, 17, 3434–3445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Zhang, L.; Yu, S.; Prokhorov, D.; Mei, X.; Ling, H. Feature pyramid and hierarchical boosting network for pavement crack detection. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2019, 21, 1525–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Zhong, X.; Zhao, C.; Chen, A.; Zhang, T. A UAV-based machine vision method for bridge crack recognition and width quantification through hybrid feature learning. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 299, 123896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flah, M.; Suleiman, A.R.; Nehdi, M.L. Classification and quantification of cracks in concrete structures using deep learning image-based techniques. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2020, 114, 103781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-Y.; Park, M.-W.; Huynh, N.T.; Shim, C.; Park, J.-W. Detection and Length Measurement of Cracks Captured in Low Definitions Using Convolutional Neural Networks. Sensors 2023, 23, 3990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X. Image-based post-disaster inspection of reinforced concrete bridge systems using deep learning with Bayesian optimization. Comput.-Aided Civ. Infrastruct. Eng. 2019, 34, 415–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzazade, A.; Popescu, C.; Blanksvärd, T.; Täljsten, B. Workflow for off-site bridge inspection using automatic damage detection-case study of the pahtajokk bridge. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 2665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kun, J.; Zhenhai, Z.; Jiale, Y.; Jianwu, D. A deep learning-based method for pixel-level crack detection on concrete bridges. IET Image Process. 2022, 16, 2609–2622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, I.-H.; Jeon, H.; Baek, S.-C.; Hong, W.-H.; Jung, H.-J. Application of crack identification techniques for an aging concrete bridge inspection using an unmanned aerial vehicle. Sensors 2018, 18, 1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, Y.; Mao, J.; Wang, H.; Xi, Z.; Xu, Y. Toward High-Precision Crack Detection in Concrete Bridges Using Deep Learning. J. Perform. Constr. Facil. 2023, 37, 04023017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Liu, M.; Peng, Y.; Wu, L.; Wang, Y. HDCB-Net: A neural network with the hybrid dilated convolution for pixel-level crack detection on concrete bridges. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2020, 17, 5485–5494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.S.; Nguyen, S.D.; Lee, H.J.; Tran, V.P. Advanced crack detection and segmentation on bridge decks using deep learning. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 400, 132839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, S.-P.; Chang, Y.-C.; Wang, F.-L. Combining the YOLOv4 deep learning model with UAV imagery processing technology in the extraction and quantization of cracks in bridges. Sensors 2023, 23, 2572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, K.; Meng, X.; Hao, M.; Huang, G.; Hu, Q.; He, P. Research on the Efficiency of Bridge Crack Detection by Coupling Deep Learning Frameworks with Convolutional Neural Networks. Sensors 2023, 23, 7272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inam, H.; Islam, N.U.; Akram, M.U.; Ullah, F. Smart and Automated Infrastructure Management: A Deep Learning Approach for Crack Detection in Bridge Images. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakaria, M.; Karaaslan, E.; Catbas, F.N. Advanced bridge visual inspection using real-time machine learning in edge devices. Adv. Bridge Eng. 2022, 3, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q.; Yang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Song, J.; Wang, J. A Robot System for Rapid and Intelligent Bridge Damage Inspection Based on Deep-Learning Algorithms. J. Perform. Constr. Facil. 2023, 37, 04023052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozgenel, F. Concrete crack images for classification. Mendeley Data 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; He, S.; Liu, X.; Jiang, S.; Xiang, S. Intelligent crack detection and quantification in the concrete bridge: A deep learning-assisted image processing approach. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2022, 2022, 1813821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, C.; Zhang, H.; Wang, S.; Li, Y.; Wang, H.; Yan, F. Structural damage detection using deep convolutional neural network and transfer learning. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2019, 23, 4493–4502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carranza-García, M.; Torres-Mateo, J.; Lara-Benítez, P.; García-Gutiérrez, J. On the performance of one-stage and two-stage object detectors in autonomous vehicles using camera data. Remote Sens. 2020, 13, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Z.; Chen, K.; Shi, Z.; Guo, Y.; Ye, J. Object detection in 20 years: A survey. Proc. IEEE 2023, 111, 257–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, S.; Divekar, A.V.; Anilkumar, C.; Naik, I.; Kulkarni, V.; Pattabiraman, V. Comparative analysis of deep learning image detection algorithms. J. Big Data 2021, 8, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.-H.; Lee, J.-C.; Wang, Y.-M. A study of defect detection techniques for metallographic images. Sensors 2020, 20, 5593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| String |

|---|

| (“Viaducts” OR “Bridge”) AND (“Artificial intelligence” OR “Image processing” OR “Machine learning” OR “Deep learning” OR “CNN” OR “convolutional neural network”) AND (“Defect detection” OR “Crack detection” OR “Damage detection” OR “spalling” OR “vegetation” OR “scaling” OR “Delamination” OR “Efflorescence” OR “bulging” OR “Pop-outs” OR “Honeycombs” OR “Reinforcing steel corrosion” OR “Exposed bar” OR “Exposed rebar” OR “corrosion stain “ OR “Water leak” OR “Water leakage” OR “material loss” OR “Loss of section” OR “displacement” OR “deformation” OR “degradation” OR “damage quantification” OR “damage measurement” OR “damage evaluation” OR “damage severity”) AND (“image” OR “video”) |

| Phases | Criteria |

|---|---|

| Title and Abstract Screening | Review papers were excluded. Titles lacking clarity were excluded. Only articles related to visual defect detection on concrete bridges were included. Articles with abstracts lacking sufficient methodological detail to determine whether deep learning was applied to concrete bridge surface defect detection using standard 2D images were excluded. Non-English language articles and non-peer-reviewed documents (e.g., theses, technical reports) were excluded. |

| Full-text Screening | Articles focusing on hardware-only aspects (e.g., camera hardware, UAV trajectory planning, or sensor placement) without proposing or evaluating a deep learning model for defect detection were excluded. Articles focusing on other bridge defects like cable defects instead of concrete damages were excluded. |

| Author | Algorithm | Type of Defect(s) | Preprocessing | Dataset Details | Performance (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dataset Name | Number of Images | |||||

| Chen [38] | A Variant of the VGG structure | Crack | Labeling Data augmentation Cropping | Own data collection using a UAV and a handheld DSLR camera | 2000 | Accuracy = 99.1% |

| Hüthwohl et al. [42] | Inception V3 | Cracks | Labeling | Own data collection and authority image sets | 38,408 | Accuracy = 97.4% |

| Efflorescence | Accuracy = 96.9% | |||||

| Scaling | Accuracy = 94.6% | |||||

| Spallation | Accuracy = 94.3% | |||||

| General defects | Accuracy = 95.4% | |||||

| No defect | Accuracy = 97.2% | |||||

| Spallation scaling | Accuracy = 95.2% | |||||

| Exposed bars | Accuracy = 87% | |||||

| Corrosion | Accuracy = 94.9% | |||||

| Zhu et al. [5] | CNN | Spallation Exposed bars Crack Pockmark | Brightness adjustment, saturation adjustment, and flip adjustment labeling | Own data collection using a digital camera (Canon EOS 700 D, 18 megapixels) | 1458 | Accuracy = 97.8% |

| Mundt et al. [44] | Efficient Neural Architecture Search (ENAS) | Crack Spallation Exposed bars Efflorescence Corrosion (stains) | Labeling | COncrete DEfect Bridge IMage: CODEBRIM | 1590 | Accuracy = 70.78% |

| MetaQNN | Accuracy = 72.19% | |||||

| Zoubir et al. [49] | VGG16 | Efflorescence Spallation Crack | Data augmentation (flipping, rotating) Labeling | Own data collection using two 20-MP consumer digital cameras with 5 mm focal length | 6952 | Accuracy = 97.13% |

| Bukhsh et al. [48] | CNN | Crack Spallation Exposed bars Corrosion stain | Labeling | BiNet | 3588 | Accuracy = 80 ± 1% |

| VGG16 | Accuracy = 80 ± 2% | |||||

| Pretrained VGG16-ImageNet | Accuracy = 88 ± 1% | |||||

| Pretrained VGG16-CODEBRIM | Accuracy = 81 ± 1% | |||||

| Kruachottikul et al. [50] | ResNet-50 | Crack Erosion Honeycombing Spallation Scaling | Data augmentation (image rotations, adding noises, and flipping images), labeling | Own data collection using a mobile application | 3618 | Accuracy = 81% |

| Xu et al. [36] | End-to-end CNN | Crack | Filtering, cropping, flipping, resizing | Own data collection using the Phantom 4 Pro’s CMOS surface array camera | 6069 | Accuracy = 96.37% |

| Zhang et al. [37] | 1D-CNN-LSTM | Crack | Images were transformed into the frequency domain Cropping Labeling | SDNET2018 | 16,789 | Accuracy = 99.25% |

| Cardellicchio et al. [45] | DenseNet121 + transfer learning, InceptionV3 + transfer learning, ResNet50V2 + transfer learning, MobileNetV3 + transfer learning, NASNetMobile + transfer learning | Corroded/oxidized steel reinforcement Cracks Deteriorated concrete Honeycombs Moisture spots Pavement degradation shrinkage cracks | Labeling Data enrichment and augmentation (horizontal and vertical flipping) | Own data collection | 2436 | Best Accuracy = 85.19% for crack 85.4% for corroded and oxidized steel reinforcement 91.78% for deteriorated concrete 90.96% for honeycombs 76.43% for moisture spots 93.44% for pavement degradation 96.13% for shrinkage cracks |

| Trach [46] | CNN (MobileNet architecture) | Crack Spallation (this class includes two groups of defects—(scaling) and (spallation)) Popout | Manually crop 256 by 256 pixel rotating part of the images by 90◦ to overcome the unbalanced dataset | Data collected from real inspection reports of bridge structures, which were taken for over 15 years in different regions of Ukraine | 5200 | Accuracy = 94.61% |

| Chen et al. [41] | MobileNetV3-Large-CBAM | Crack | Data augmentation (flipping, mirroring, cropping, and rotating data) Labeling | Bridge crack dataset [53] | 6532 | Accuracy = 95.9% |

| Open-source datasets and images collected from the web | 15,068 | Accuracy = 99.66% for various material cracks test set and 99.69 for huge-width cracks test set | ||||

| Zhang et al. [54] | Hybrid probabilistic deep convolutional neural network | Crack | Labeling | Own data collection | 40,000 | Accuracy = 99.09% |

| Own data collection | 2600 | Accuracy = 92.49% | ||||

| Abubakr et al. [47] | Xception | Cracks, corrosion, efflorescence, spallation, and exposed bars | Labeling | CODEBRIM | 1590 | Accuracy = 94.95% |

| Vanilla | Accuracy = 85.71% | |||||

| Alfaz et al. [39] | Dense Convolutional Network (DenseNet) | Crack | Cleaning, resizing, and manual categorization | Crack dataset, gathered by Xu et al. [36] | 6069 | Accuracy = 99.83% |

| Aliyari et al. [51] | CNNs | crack | Rotation, zooming in, cropping, flipping | SDNET | 19,023 | Accuracy (DenseNet210) = 97% |

| Rotation, vertical and horizontal flipping, and zoom-in | Heterogeneous dataset: own data collection | 308 | Accuracy (VGG16, Resnet152v2) = 69% | |||

| Rotation, vertical and horizontal flipping, and zoom-in | Homogeneous dataset: own data collection | 400 | Accuracy (Xception) = 74% | |||

| Li et al. [40] | A convolutional neural network named Skip-Squeeze-and-Excitation Networks (SSENets) | Crack | Filtering, cropping, and flipping Labeling | Crack dataset, gathered by Xu et al. [36] | 6069 | Accuracy = 97.77% Precision = 95.45% |

| Author | Algorithm | Type of Defect(s) | Preprocessing | Dataset Details | Performance (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dataset Name | Number of Images | |||||

| Murao et al. [55] | YOLOv2 | Crack | Labeling, resized, inverted, rotated, HSV (Hue, Saturation, Value) | Own data collection using a UAV equipped with a camera and various image data collected from the Internet | 164 for system 1 | |

| Concrete joints with line forms other than cracks:, etc., Crack Branch-crack chalk Branch-chalk | 166 for system 2 | Precision = 27.95% | ||||

| Concrete joints with line forms other than cracks: etc., Crack Branch-crack chalk Branch-chalk | 253 for system 3 | Precision = 41.63% | ||||

| Yu et al. [56] | YOLOv4-FPM | Crack | Cropping, Labeling | Own data collection using digital SLR camera (Canon EOS M10) and UAV | 2768 | mAP = 97.6% |

| Li et al. [57] | Lite-YOLO-v4 | Crack | Mosaic data augmentation Labeling | Data collected from a bridge underwater inspection company and the Internet, including Crack 500 dataset | 8780 | mAP = 77.07% Precision = 93.97% Recall = 47.98% |

| Deng et al. [58] | YOLOv2 | Cracks and handwriting | Horizontal flipping labeling | Data collected by inspectors during annual visual inspections | 3010 | mAP = 77% |

| Ji [59] | YOLO Autobot | Crack | labeling | Crack dataset provided by RoboFlow [73] | 3917 | mAP = 82.6% |

| Deng et al. [71] | Faster R-CNN | Cracks and handwriting | labeling horizontal flipping cropping | Images from inspection records of concrete bridges taken by consumer-grade cameras with complex background information | 5009 | mAP = 82% |

| Ruggieri et al. [60] | YOLOv5 (different versions) | Crack, corroded steel reinforcement, deteriorated concrete, honeycombs, moisture spots, pavement degradation | Labeling | Collecting figures from the observations of some existing bridges in Italy | 2685 | For YOLOv5m6: mAP = 20.66% Precision = 43.63% Recall = 24.24% |

| Zhang et al. [61] | Modified YOLOv3 | Crack Spallation Exposed bars Pop-out | Downsampling Labeling Data augmentation: (scaling and cropping, flipping, manipulating the images by applying the motion blur, changing brightness, or adding salt and pepper noise) | Data acquired from the Hong Kong Highways Department + Own data collection | 2206 | mAP = 79.9% |

| Liu et al. [62] | YOLOv5 | Crack | Labeling | Own data collection: The original dataset | 180 sets of training samples and 10 sets of validation samples | |

| The extended dataset produced by DCGAN | 180 sets of training samples and 10 sets of validation samples) | |||||

| Yamane et al. [63] | YOLOv5 | Exposed bars | Labeling | Data were taken during the inspection of bridges managed by the Kanto Regional Development Bureau of Japan’s Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism from 2004 to 2018 using Skydio 2, a small UAV developed by Skydio. | 1000 | AP = 64% |

| Teng et al. [64] | Improved YOLOv3 | Cracks Exposed bars | Data augmentation (color jitter augmentation, flipping, scaling) Labeling | Data from concrete bridges (along the Erenhot–Guangzhou and Guangzhou–Kunming Expressways) | 1660 | mAP= 91% |

| Hong et al. [70] | (BDODC-F): Mask R-CNN Blendmask | Efflorescence Spallation Crack Corrosion Water leak Concrete scaling | Enhancing the image quality Labeling | Own data collection | 100 for Aggregated model training | Blendmask accuracy = 92.675% Mask-RCNN accuracy = 98.679% |

| Yu et al. [65] | Modified Faster R-CNN | Crack Spallation Exposed bars | Resizing Labeling | Images taken by a Canon EOS 5DS R camera from the periodic inspection of bridges by the CCCC First Highway Consultants Co., Ltd. | 1000 | mAP = 84.56% |

| Gan et al. [68] | Faster R-CNN | Crack | Labeling | Own data collection using DJI M210-RTK | 637 | Precision = 92.03% Recall = 92.26% |

| Lin et al. [67] | Faster-RCNN | Crack | Labeling Data augmentation (flipping, rotation, shearing, and changing brightness and contrast) | Own data collection using UAV | 742 | Average precision = 49.2% |

| Spallation | Average precision = 84.6% | |||||

| Efflorescence | Average precision = 57.6% | |||||

| Corrosion stains | Average precision = 74.1% | |||||

| Exposed bars | Average precision = 84.5% | |||||

| Ngo et al. [74] | CNN | Crack | Changed in brightness and rotation to increase the training image’s quality | Own data collection and the existing datasets (from Kaggle’s image, SDNet2018, and …) | 51,000 | Accuracy = 95.19% |

| Lu et al. [75] | MSCNet | Crack | Labeling | SDNET dataset and CCIC dataset | 30,000 | Accuracy = 92.7% Precision = 93.5% Recall = 94.2% F1-score = 93.8% |

| Ruggieri et al. [72] | Yolo11x+ attention mechanisms | Crack Corroded steel bar Deteriorated concrete Honeycomb Moisture spot Shrinkage Pavement degradation | Labeling | Dataset proposed by [45] | 6580 | mAP = 59.38% Precision = 82.87% Recall = 52.61% F1-score = 64.36% |

| Author | Algorithm | Type of Defect(s) | Aim | Quantified Attribute | Preprocessing | Dataset Details | Performance (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dataset Name | Number of Images | |||||||

| Rubio et al. [81] | Fully convolutional networks | Delamination | Detection | Labeling Flipping Changing in illumination and slight affine transformations | Data collected from inspection records of bridges in Niigata Prefecture, Japan | 734 | Mean accuracy = 89.7% | |

| Exposed bars | Mean accuracy = 78.4% | |||||||

| Tian et al. [77] | Otsu binarization method (threshold segmentation) | Crack Other damages, such as concrete cavities and damage | Detection and quantification (in physical units) | Width Length Area | Grayscale processing Gray adjustment Adaptive filter function Wiener2 for noise removal | Image processing method | ||

| Vivekananthan et al. [78] | Image processing-based segmentation (gray-level discrimination approach) | Crack | Detection and quantification | Area and orientation | Gray level discrimination | Own data collection using CMOS cluster camera | 2068 | Accuracy = 95% |

| Adhikari et al. [76] | Image processing-based segmentation (threshold operation:(a) maximum entropy; (b) Otsu; and mean of the intensity in the given image Erode and Dilate) | Crack | Detection and quantification (in physical units) | Width Length | Image enhancement using point processing, histogram equalization, and mask processing | Own data collection using SONY-DSC T5 digital camera | Image processing method | |

| Lopez Droguett et al. [82] | DenseNet-13 | Crack | Detection | Labeling | Own data collection: CRACKV2 | 409,432 | mIoU = 92.13% | |

| Merkle et al. [83] | U-NET | Crack | Detection and quantification (in physical units) | Width Length | Labeling | Own data collection | 126 | Precision = 56.1% Recall = 59.9% IoU = 40.8% |

| Fukuoka and Fujiu [85] | SegFormer | Delamination Exposed bars | Detection | Data augmentation (flipping, scaling, rotation) Labeling | Data collected from the Japanese bridge inspection report: dataset A | 17,810 | Precision: Delamination detection = 80.8% Rebar-exposure detection = 70.8% | |

| Data collected from the Japanese bridge inspection report: dataset B | 17,810 | Precision: Delamination detection = 77.1% Rebar-exposure detection = 74.7% | ||||||

| Data collected from the Japanese bridge inspection report: dataset C | 17,810 | Precision: delamination detection = 76.9% rebar-exposure detection = 76.5% | ||||||

| Li et al. [86] | A neural network based on the encoder–decoder | Crack | Detection | 90°, 180° clockwise rotation and horizontal inversion Labeling | Own data collection using a telephoto camera on the equipment cart to take pictures of the bridge cracks | 2240 which were expanded to 10,000 images | mIoU = 84.5% Precision = 98.3% Recall = 97.3% | |

| Yamane et al. [87] | Mask-R-CNN | Corrosion | Detection | Resizing Labeling | Own data collection | 1966 | Accuracy = 94% Precision = 80% | |

| Xu et al. [88] | Modified DeepLabv3+ | Crack | Detection | Data augmentation (horizontal and vertical flipping, random rotation, and random translation) Labeling | Own data collection captured from several actual bridges in multiple scenes, scales, and resolutions | 4303 | mAP = 88.8% mIoU = 77.6% | |

| Bae et al. [89] | End-to-end deep super-resolution crack network (SrcNet) | Crack | Detection | Rotating, flipping, labeling | Own data collection and web scraping | 4055 | Precision on Jang-Duck bridge = 81.18% Recall on Jang-Duck bridge = 92.65% | |

| Deng et al. [90] | LinkASPPNet | Delamination, exposed bars | Detection | Labeling | Images from inspection records of Japanese concrete bridges | 732 | Mean precision= 73.59% Mean IoU = 61.95% | |

| Munawar et al. [92] | CycleGAN | Corrosion | Detection | Adjusting the image brightness and size Data augmentation (flipping, rotation, cropping) Labeling | Own data collection using the UAV model DJI-M200 Also, images were extracted from public datasets | 1300 | mIoU = 87.8% Precision = 84.9% Recall = 81.8% | |

| Li et al. [106] | Fully convolutional network and a Naive Bayes data fusion (NB-FCN) model | Crack-only Handwriting Peel off Water stain Repair trace | Detection and Quantification (in physical units) | Crack Length and width | Rotating Flipping Labeling Resizing | Own data collection using an image acquisition device named Bridge Substructure Detection (BSD-10) | 7200 | Accuracy = 97.96% Precision = 81.73% Recall = 78.97% F1-score = 79.95% |

| Fu et al. [91] | DeepLabv3+ | Crack | Detection | Flipping, rotation, scaling Labeling | Own data collection using digital equipment and from the Internet in various environments. | 5000 | mIoU = 82.37% | |

| Qiao et al. [93] | EMA-DenseNet | Cracks, exposed bars | Detection | Pixel-level labeling Rotation Cropping | Yang et al. [107] dataset | 800 | Validation mIoU = 87.42% | |

| Own data collection from bridges in Xuzhou (Zhejiang Province, China) | 1800 crack images and 2500 rebar images | Validation mIoU = 79.87% Test mIoU= 80.4% | ||||||

| Jin et al. [95] | PCR-Net-based model | Crack | Detection | Labeling | Synthesized crack image dataset named Bridge Crack Library 2.0 | 26,600 | Accuracy = 98.9% mIoU = 61.49% Precision = 81.63% Recall = 71.36% | |

| Subedi et al. [96] | Nested Reg-Unet | Concrete damage and exposed bars | Detection | Data augmentations (flipping, random brightness. and contrast change) Labeling | Tokaido Dataset [108] | 7079 | mIoU = 84.19% Precision = 90.98% Recall = 91.04% | |

| Ayele et al. [97] | Mask R-CNN | Crack | Detection and quantification (in physical units) | Cracks length and width | Labeling | Own data collection using a UAV | Accuracy = 90% | |

| Wang et al. [98] | RefineNet with Attention Mechanism (RefineNet-AM) | Concrete damage and exposed bars | Detection | Tokaido Dataset [108] | 8599 | mIoU = 67.3% Precision = 84.4% Recall = 73.8% | ||

| Montes et al. [99] | 3D GNN | Corrosion, spallation, cracks, and leaking water | Detection | Labeling | Own data collection using a lidar | Accuracy = 93.914% mIoU = 33.98% | ||

| Artus et al. [100] | TernausNet16 | Spallation | Detection and quantification (in physical units) | Spallation and crack (CSSC) database [109] | 715 | Accuracy = 91.96% mIoU = 83.26% Precision = 87.55% Recall = 81.36% | ||

| Borin and Cavazzini [101] | Mask R-CNN | Spallation | Detection and visualization | Labeling | Own data collection | 575 | ||

| Jang et al. [102] | Modified SegNet | Intact Crack Marker | Detection and quantification (in physical units) | Crack length and width | Contrast enhancement, Labeling | Own data collection using a ring-type climbing robot at Jang-Duck Bridge in Gangneung City. South Korea | 1021 | Precision = 90.92% Recall = 97.47% |

| McLaughlin et al. [103] | DeepLab V3 | Spallation Delaminations | Detection and quantification (in physical units) | Area | Flip horizontal Flip vertical, Rotation Width and height shift Labeling | Own data collection | 496 infrared images 600 visual spectrum images | Validation mIoU = 71.4% |

| Validation mIoU = 82.7% | ||||||||

| Ye et al. [104] | Multi-task high-resolution net (MT HRNet) | Concrete damage (crack and spallation) and exposed bars | Detection and quantification | Spallation area and the width of the cracks (in pixels) | Tokaido dataset [108] | 13,956 | Accuracy = 99.44% mIoU = 80.47% Precision = 94.66% Recall = 83.62% | |

| Shen et al. [105] | Adaptive learning filters vision transformer (ALF-ViT), | Crack | Detection | Enhancement | CrackForest data set [110], Crack500 data set [111] and own data collection using mobile devices | 1339 | mIoU = 73.3% | |

| Na and Kim [84] | U-Net | Crack, spallation and delamination, water leakage, exposed bars, and paint peeling | Detection | Data augmentation Labeling | Own data collection using a UAV | 14,155 | Accuracy = 95.7% Precision = 91.2% Recall = 91.4% F1-Score = 91.3% | |

| Author | Task (Segmentation/Object Detection/Classification) | Algorithm | Type of Defect (s) | Aim | Quantified Attribute | Preprocessing | Dataset Details | Performance (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dataset Name | Number of Data | ||||||||

| Peng et al. [112] | Object detection + Segmentation | R-FCN + Haar-AdaBoos t + A local threshold segmentation | Crack | Detection and quantification (in physical units) | Width | Labeling Data augmentation | Own data collection using a UAV | 3540 | Average IoU = 90% for crack segmentation Precision = over 95% for detection |

| Flah et al. [113] | Classification + Segmentation | CNN + Edge detection and thresholding (Otsu method) | Crack | Detection and quantification (in physical units) | Length, width, angle of crack | Manual image selection Labeling Filter utilization to remove the non-uniform background intensity | Concrete crack image classification database [127] | 6000 | Classification accuracy = 98.25% |

| Kim et al. [114] | Classification + Segmentation | CNN (AlexNet, VGG16, ResNet152) + Morphological segmentation | Crack | Detection and quantification (in physical units) | Length | Labeling | Data collected by the Korea Expressway Corporation’s bridge monitoring system | 192 | Precision: AlexNet = 87.74% VGG-16 = 88.76% ResNet 152 = 87.59% |

| Liang [115] | Classification | Pre-trained VGG16 | Bridge damage | Detection | Labeling Data augmentation | Collected from different studies and Google images | 492 | Accuracy = 98.98% | |

| Semantic segmentation | Fully deep CNN | Pixel-wise labeling | 436 | Accuracy = 93.14% Weighted IoU = 87.65% | |||||

| Mirzazade et al. [116] | Classification + Localization + Segmentation | Inception v3 for damage area detection+ U-Net and SegNet for pixel-wise defect segmentation | Damage classification + joints segmentation | Detection and quantification (in physical units) | Joint length and width | Cropping Labeling | Own data collection using a UAV | 140 images cropped to 8344 slices and 238 images for segmentation | Inception v3 validation accuracy = 96.2% SegNet mIoU = 49.98% U-Net mIoU = 47.102 |

| Kun et al. [117] | Classification + Segmentation | Deep bridge crack classification (DBCC)-Net: (A CNN-based neural network for crack patch classification) segmentation: DDRNet | Crack | Detection | Labeling | Own data collection using an I-800 UAV | 385 | DBCC-Net F1-score = 72.6% IoU = 83.4% | |

| Kim et al. [118] | Object detection + Segmentation | R-CNN+ image processing | Crack | Detection, localization, and quantification (in physical units) | Thickness and length | Labeling | Images were taken using human resources and the UAV | 384 | Crack quantification relative error = 1–2%, |

| Yu et al. [128] | Object detection + Segmentation | YOLOv5+ image processing segmentation | Crack | Detection and quantification (in physical units) | Length and width | Cropping Extract the binary image Median filtering and graying Mask filter and ratio filter Labeling Data augmentation (mosaic, random rotation, random cropping, Gaussian noise, and manual exposure) | Own data collection using a Canon EOS 5DS R camera. | 487 processed by offline data augmentation to obtain 3453 images | For YOLOv5: mAP = 98.7% Precision = 92% Recall = 97.5% For crack quantification: Absolute error is within 0.05 mm |

| Ni et al. [119] | Object detection + Segmentation | YOLOv5s+ Ostu method and the medial axis algorithm | Crack | Detection and quantification (in physical units) | Crack length and width | Denoising, filtering, and image enhancement (including image flipping, mirroring, rotation, translation, shearing) Dataset Augmentation through DCGANs Labeling | The concrete crack dataset is divided into two sections. The authors created one portion, while the other was obtained from publicly available data sources [52] | 4000 | For YOLOv5 Precision = 83.3% Recall = 95.3% mAP = 94% |

| Jiang et al. [120] | Object detection + Segmentation | YOLOv4 + HDCB-Net | Crack | Detection | Labeling | Own data collection: Blurred Crack, which contains five sub-datasets | 150 632 | Highest mAP of YOLOv4 = 80.1% on the BridgeXQ48 | |

| Own data collection: Bridge Nonblurred | 1536 | HDCB-Net precision = 61.72% | |||||||

| Tran et al. [121] | Object detection + Segmentation | Detecting cracks: YOLOv7 Segmentation: optimized U-Net | Crack | Detection and quantification (in physical units) | Crack length and width | Labeling | Own data collection from bridge decks in South Korea using a 3D-mounted vehicle camera | 1441 for the crack detection algorithm 800 to train the crack segmentation algorithm | mAP@0.5 = 74.5% for YOLOv7 IoU= 64% for optimized U-Net |

| Kao et al. [122] | Object detection + Segmentation | YOLOv4 + Thresholding (Sauvola local thresholding method) and edge detection for segmentation (Canny edge detection and morphological edge detection) | Crack | Detection and quantification (in physical units) | Crack width | Labeling for object detection For segmentation: Cropping to the Bounding Box Converting into grayscale image Image Binarization | Own data collection using Smartphones and UAVs + Open-source data on cracks (SDNET 2018 dataset [52]) | 1463 + 3006 = 4469 | mAP = 92% for YOLOv4 |

| Ma et al. [123] | Object detection + Segmentation | Object detection: Faster R-CNN SSD (YOLO)-v5(x) Segmentation: U-Net PSPNet | Crack | Detection | Labeling | Open-source dataset [53] | 2068 | F1-score: Faster R-CNN = 76% SSD = 67% YOLOv5 = 67% Accuracy: U-Net = 98.37% PSPNet = 97.86% | |

| Inam et al. [124] | Object detection + Segmentation | YOLOv5 s, m, and l U-Net | Crack | Detection | Width, height, area | Data resizing and augmentation (rotation and cropping) Labeling | Own data collection dataset from Pakistan bridges + SDNET2018 dataset [52] | 1370 2270 after data augmentation | YOLOv5 s, m, and l mAP = 97.8%, 99.3%, and 99.1% U-Net accuracy on validation set of SDNET2018 = 93.4% |

| Zakaria et al. [125] | Object detection + Segmentation | Object detection: Yolov5s Segmentation: U-Net | Crack and spallation | Detection, localization, and quantification (in physical units) | Maximum crack width or area of spallation | bounding box labeling data augmentation | Own data collection + also from datasets published by other researchers, including CODEBRM [44] and SDNET2018 [52] | 1600 + 180 | mAP = 51% for Yolov5s mIoU = 74% for U-Net |

| Meng et al. [126] | Object detection + Segmentation | Object detection: Improved YOLOv3 Crack Segmentation algorithm: DeepLab | cracks, spallation, exposed bars, and efflorescence | Detection and quantification | Crack length and width | Retinex image denoising algorithm Labeling | Own data collection | 20,033 | For improved YOLOv3: mAP = 86.3% precision = 92.9% Recall = 86.9% F1-score = 90% For DeepLab: Accuracy = 85% |

| Zhang et al. [80] | Object detection + Segmentation | Object detection: CR-YOLO Segmentation: PSPNet | Cracks | Detection | Data enhancement (geometric transformation, optical transformation, and noise addition) | Own data collection using a digital camera + portion of an open-sourced dataset [36] | 5000 | For CR-YOLO: Precision = 90.88% Recall = 88.69% PSPNet: Precision = 87.03 Recall = 85.45% | |

| Reference | Task | Algorithm | Performance (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mirzazade et al. [116] | Segmentation | SegNet | Mean Accuracy in large-scale object segmentation = 97.299 Mean Accuracy in small-scale object segmentation = 50 | ||||

| U-Net | Mean Accuracy in large-scale object segmentation = 84.144 Mean Accuracy in small-scale object segmentation = 79.5 | ||||||

| Liang [115] | Classification | VGG-16 | Testing Accuracy = 98.98 | ||||

| AlexNet | Testing Accuracy = 93.88 | ||||||

| Tran et al. [121] | Object Detection | YOLOv7 | MAP@0.5 = 74.8 | Speed (Time to analyze a 1024 × 1024-pixel image) (s) = 0.022 | |||

| Faster RCNN-ResNet101 | MAP@0.5 = 72.8 | Speed (s) = 0.18 | |||||

| RetinaNet-ResNet101 | MAP@0.5 = 72.7 | Speed (s) = 0.065 | |||||

| RetinaNet-ResNet50 | MAP@0.5 = 72 | Speed (s) = 0.055 | |||||

| Faster RCNN-ResNet50 | MAP@0.5 = 71.2 | Speed (s) = 0.164 | |||||

| Trach [46] | Classification | MobileNet | Accuracy = 94.61 | Mean times (training time of one epoch) (s) = 63 | |||

| ResNet 50 | Accuracy = 93.1 | Mean times (s) = 79 | |||||

| VGG16 | Accuracy = 92.73 | Mean times (s) = 101 | |||||

| DenseNet201 | Accuracy = 91.82 | Mean times (s) = 120 | |||||

| Inception V3 | Accuracy = 89.54 | Mean times (s) = 63 | |||||

| Cardellicchio et al. [45] | Classification | DenseNet121 | Accuracy = 85.19 for crack, 81.92 for Corroded and oxidized steel reinforcement, 91.10 for Deteriorated concrete, 90.37 for Honeycombs, 73.94 for Moisture spots, 89.89 for Pavement degradation, 96.05 for Shrinkage cracks | ||||

| InceptionV3 | Accuracy = 79.7 for crack, 85.03 for Corroded and oxidized steel reinforcement, 91.78 for Deteriorated concrete, 90.37 for Honeycombs, 73.26 for Moisture spots, 93.44 for Pavement degradation, 96.04 for Shrinkage cracks | ||||||

| ResNet50V2 | Accuracy = 83.33 for crack, 81.85 for Corroded and oxidized steel reinforcement, 91.78 for Deteriorated concrete, 90.96 for Honeycombs, 74.77 for Moisture spots, 89.88 for Pavement degradation, 96.12 for Shrinkage cracks | ||||||

| MobileNetV3 | Accuracy = 84.30 for crack, 83.26 for Corroded and oxidized steel reinforcement, 90.96 for Deteriorated concrete, 89.56 for Honeycombs, 76.43 for Moisture spots, 92.25 for Pavement degradation, 96.13 for Shrinkage cracks | ||||||

| NASNetMobile | Accuracy = 81.93 for crack, 85.4 for Corroded and oxidized steel reinforcement, 91.78 for Deteriorated concrete, 90.44 for Honeycombs, 76.43 for Moisture spots, 89.88 for Pavement degradation, 96.05 for Shrinkage cracks | ||||||

| Ma et al. [123] | Object Detection | Faster R-CNN | F1-score = 76 | Precision = 80.53 | Recall = 71.37 | ||

| YOLOv5 | F1-score = 67 | Precision = 87.5 | Recall = 54.9 | ||||

| SSD | F1-score = 67 | Precision = 82.76 | Recall = 56.47 | ||||

| Ni et al. [119] | Object Detection | YOLOv5l | mAP = 99.6 | Inference time (s = frame) = 0.083 | |||

| Faster R-CNN | mAP = 98.3 | Inference time (s = frame) = 0.5 | |||||

| YOLOv3 | mAP = 98.3 | Inference time (s = frame) = 0.103 | |||||

| YOLOv4 | mAP = 82.8 | Inference time (s = frame) = 0.022 | |||||

| SSD | mAP = 71.8 | Inference time (s = frame) = 0.022 | |||||

| Qiao et al. [93] | Segmentation | DeepLab v3+ | mIoU (%) = 86.5 | FPS (f/s) = 12.8 | |||

| FCN | mIoU (%) = 85.77 | FPS (f/s) = 15.6 | |||||

| SegNet | mIoU (%) = 85.35 | FPS (f/s) = 18.5 | |||||

| Jin et al. [95] | Segmentation | DeepLab | mIoU (%) = 54.23 | Precision = 67.56 | Recall = 76.18 | Accuracy = 98.6 | F1-score = 71.61 |

| U-Net | mIoU (%) = 52.65 | Precision = 75.93 | Recall = 65.39 | Accuracy = 98.75 | F1-score = 70.26 | ||

| FCN | mIoU (%) = 51.22 | Precision = 62.35 | Recall = 77.1 | Accuracy = 98.72 | F1-score = 68.91 | ||

| Subedi et al. [96] | Segmentation | DeepLabV3+ | Precision = 89.24 | Recall = 87.27 | F1-score = 88.24 | mIoU (%) = 80.03 | Inference time (ms) = 32 |

| U-Net | Precision = 88.83 | Recall = 87.9 | F1-score = 88.36 | mIoU (%) = 80.19 | Inference time (ms) = 32 | ||

| LinkNet | Precision = 88.8 | Recall = 87.86 | F1-score = 88.33 | mIoU (%) = 80.15 | Inference time (ms) = 31 | ||

| RefineNet | Precision = 85.64 | Recall = 65.65 | F1-score = 85.64 | mIoU (%) = 76.5 | Inference time (ms) = 31 | ||

| PSPNet | Precision = 85.42 | Recall = 82.87 | F1-score = 84.13 | mIoU (%) = 74.42 | Inference time (ms) = 12 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lotfi Karkan, N.; Shakeri, E.; Sadeghi, N.; Banihashemi, S. Smart Surveillance of Structural Health: A Systematic Review of Deep Learning-Based Visual Inspection of Concrete Bridges Using 2D Images. Infrastructures 2025, 10, 338. https://doi.org/10.3390/infrastructures10120338

Lotfi Karkan N, Shakeri E, Sadeghi N, Banihashemi S. Smart Surveillance of Structural Health: A Systematic Review of Deep Learning-Based Visual Inspection of Concrete Bridges Using 2D Images. Infrastructures. 2025; 10(12):338. https://doi.org/10.3390/infrastructures10120338

Chicago/Turabian StyleLotfi Karkan, Nasrin, Eghbal Shakeri, Naimeh Sadeghi, and Saeed Banihashemi. 2025. "Smart Surveillance of Structural Health: A Systematic Review of Deep Learning-Based Visual Inspection of Concrete Bridges Using 2D Images" Infrastructures 10, no. 12: 338. https://doi.org/10.3390/infrastructures10120338

APA StyleLotfi Karkan, N., Shakeri, E., Sadeghi, N., & Banihashemi, S. (2025). Smart Surveillance of Structural Health: A Systematic Review of Deep Learning-Based Visual Inspection of Concrete Bridges Using 2D Images. Infrastructures, 10(12), 338. https://doi.org/10.3390/infrastructures10120338