Barriers and Enablers in Implementing the Vision Zero Approach to Road Safety: A Case Study of Haryana, India, with Lessons from Sweden

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Human fallibility—People will make mistakes that can lead to road crashes.

- Biomechanical limits—The human body has limited tolerance to crash forces before serious harm occurs.

- Shared responsibility—Road safety is a collective responsibility between system designers and road users.

- System resilience—All parts of the system must be strengthened to multiply protective effects; if one part fails, others should compensate.

- Pillar 1: Road Safety Management—Establishes multi-sectoral partnerships and lead agencies to coordinate national strategies, targets, and data systems.

- Pillar 2: Safer Roads and Mobility—Enhances the inherent safety of road networks, especially for vulnerable users, through infrastructure design and assessment.

- Pillar 3: Safer Vehicles—Promotes the adoption of advanced safety technologies via global standards, consumer information, and incentives.

- Pillar 4: Safer Road Users—Supports behavior-change programs through enforcement, education, and public awareness campaigns.

- Human fallibility—People will make errors that can lead to road crashes.

- Biomechanical limits—The human body has limited tolerance to crash forces before serious harm occurs.

- Shared responsibility—Road safety is a collective responsibility, but ultimate accountability lies with system designers.

- Ethical imperative—No loss of life is acceptable within the road transport system.

1.1. Previous Studies on Vision Zero Implementation

1.1.1. Cultural Perceptions

1.1.2. Political Commitment and Strategic Vision

1.1.3. Multi-Sectoral Collaboration

1.1.4. Governance

1.1.5. Resource Availability

1.1.6. Institutional Capacity

1.1.7. Enforcement and Policy Adherence

1.1.8. Road Safety Research

2. Materials and Methods

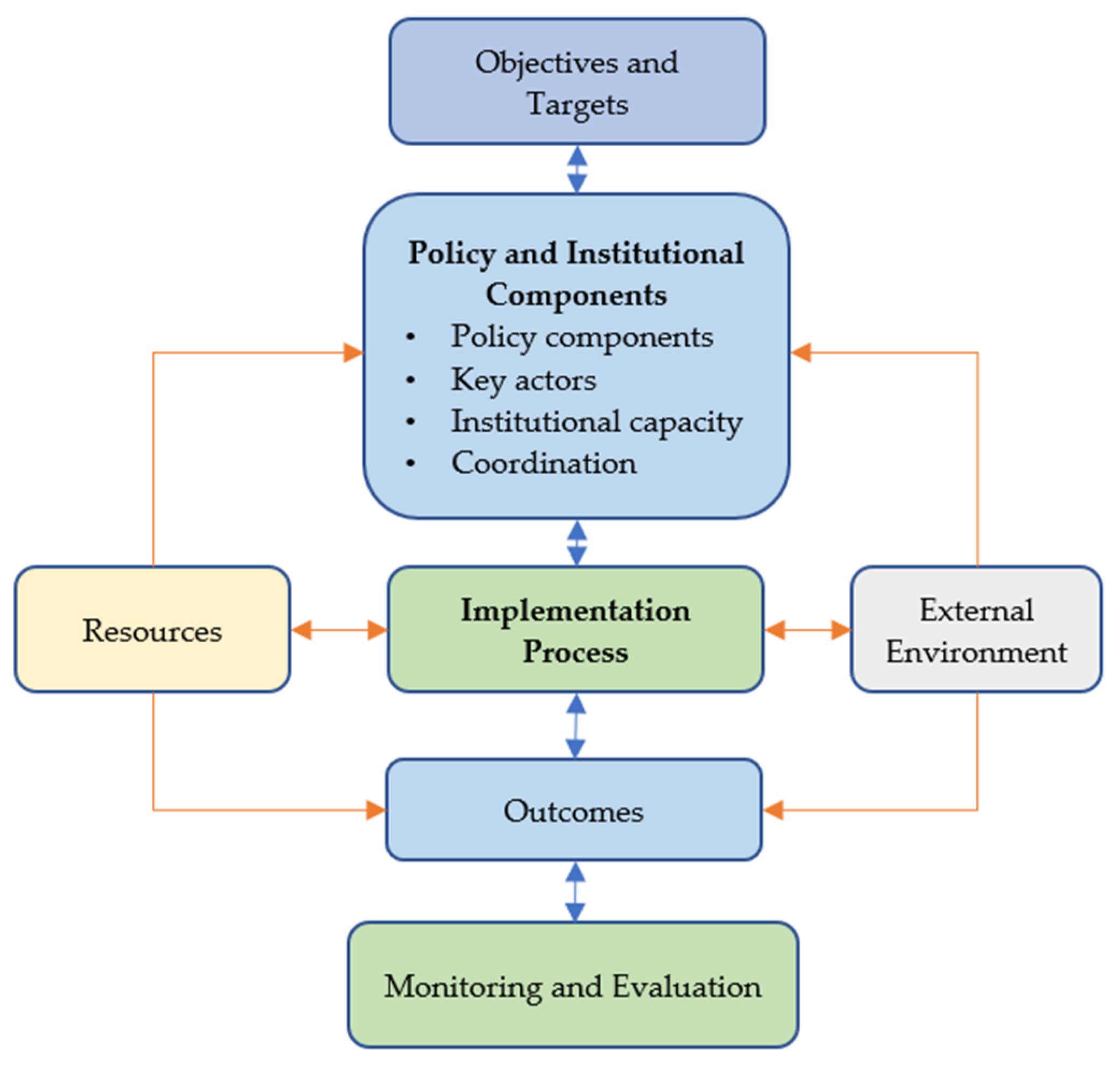

2.1. Conceptual Framework

- Objectives and Targets: It is essential to have long-term vision and to set ambitious, measurable, and achievable road safety targets in vision zero approach.

- Resources: Sufficient resources need to be available for implementing vision zero approach. Both financial and human resources need to be adequate.

- Policy Components: Vision zero policy needs to be based on four guiding principles such as adaptation of traffic system to vulnerabilities of road users; road system should be designed considering the human body tolerance limit; speed limit should be determined according to technical standards of roads and vehicles and should not exceed human body tolerance limit; shared responsibility among road system designers and road users, whereas the ultimate responsibility is upon designers of the system. Furthermore, policy components should incorporate five core components of vision zero such as safe roads, safe vehicles, safe speed, safe road users and post-crash response.

- Implementers and key stakeholders: Commitment and continuous support of implementers and key stakeholders will drive the success of vision zero.

- Implementation process: Well organized implementation process is key. Clearly defined roles and responsibilities are required for vision zero implementation.

- Institutional capacity: Effective institutional management processes to improve operational and management capacity of road safety institutions and implementing organizations.

- Coordination: Lead agency is required to coordinate key actors involved in the vision zero implementation process.

- Outcomes: Vision zero implementation should result in tangible improvements in road safety, such as reduced traffic fatalities, safer road infrastructure and increased public adherence to traffic rules.

- Monitoring and Evaluation: Monitoring activities such as regular review meetings should be established and evaluations conducted to support continuous improvement of the vision zero implementation process.

- External Environment: Impact of political, social, and economic environment needs to be supportive and managed appropriately for successful implementation.

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Trustworthiness

2.6. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

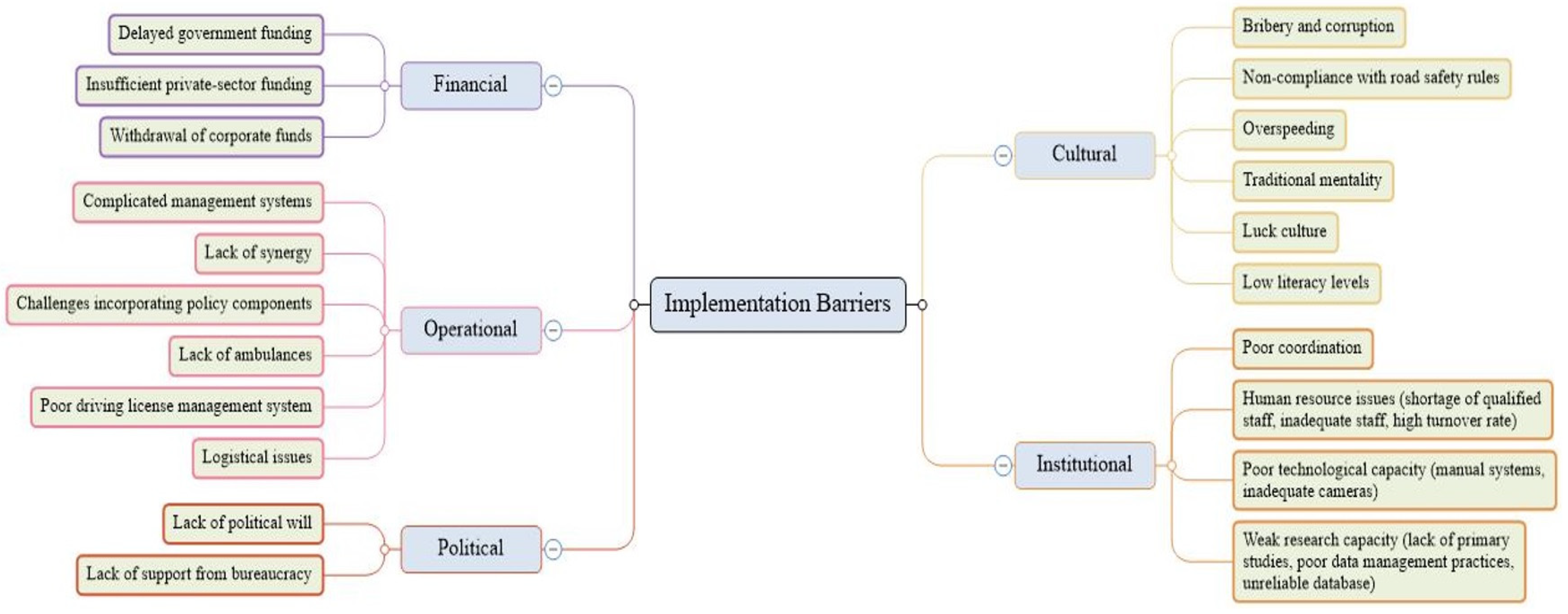

3.1. Barriers to Vision Zero Implementation Process in India

3.1.1. Cultural Barriers

3.1.2. Institutional Barriers

3.1.3. Political Barriers

3.1.4. Operational Barriers

3.1.5. Financial Barriers

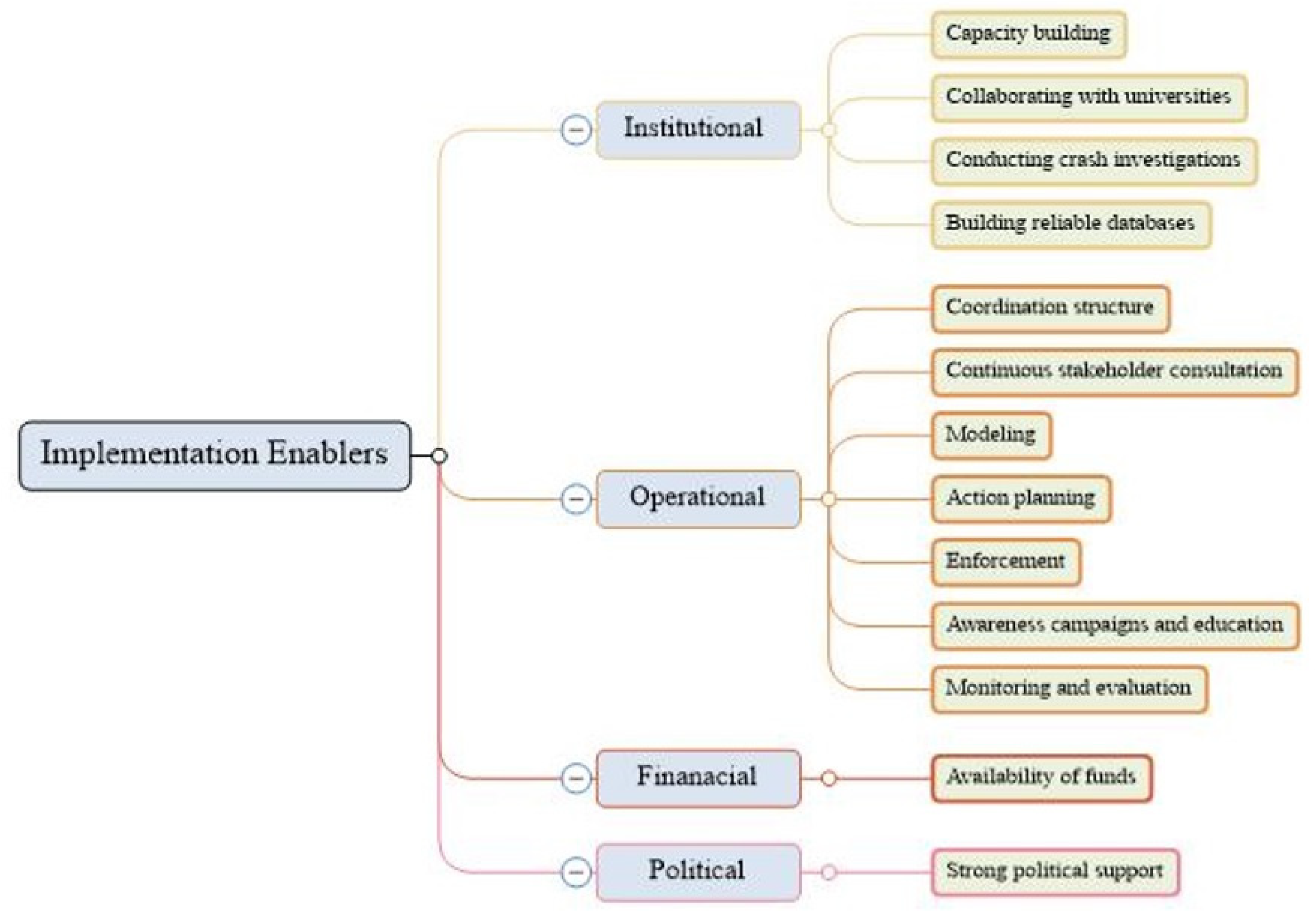

3.2. Enablers of Vision Zero Implementation Process in India

3.2.1. Institutional Enablers

3.2.2. Operational Enablers

3.2.3. Financial Enablers

3.2.4. Political Enablers

3.3. Analysis of Barriers and Enablers in India and Sweden

3.3.1. Analysis of Implementation Barriers

3.3.2. Analysis of Implementation Enablers in Haryana (India) and Sweden

3.4. Conceptual Analysis of the Barriers and Enablers Under the Components of Conceptual Framework in Haryana (India) and Sweden

3.4.1. Conceptual Analysis of Barriers

- 1.

- Objectives and targets; clearly defined policy objectives and achievable road safety targets are essential for effective implementation.

- 2.

- Resources; a successful implementation process requires dedicated and sustainable financial resources and a highly qualified workforce.

- 3.

- Policy components; vision zero should incorporate five core components of vision zero such as safer roads, safer vehicles, safer speed, safer road users and post-crash response.

- 4.

- Implementers and key stakeholders; commitment and continuous support of the various implementers and key stakeholders influence vision zero’s success.

- 5.

- Implementation process; a well-organized implementation process is key.

- 6.

- Institutional capacity; effective institutional management processes are critical for enhancing operational efficiency.

- 7.

- Coordination; a lead agency is required to coordinate with key departments involved in implementation.

- 8.

- Monitoring and evaluation; a robust monitoring and evaluation system is essential for continuous improvement of the implementation process.

- 9.

- External environment; the impact of political, social, and economic environment needs to be managed appropriately for successful implementation.

3.4.2. Conceptual Analysis of the Enablers

- 1.

- Objectives and targets; clearly defined policy objectives and achievable road safety targets are essential for effective implementation.

- 2.

- Resources; a successful implementation process requires dedicated and sustainable financial resources and a highly qualified workforce.

- 3.

- Policy components; Vision zero should incorporate five core components of vision zero such as safer roads, safer vehicles, safer speed, safer road users and post-crash response.

- 4.

- Implementers and key stakeholders; commitment and continuous support of the various implementers and key stakeholders influence vision zero’s success.

- 5.

- Implementation process; a well-organized implementation process is key.

- 6.

- Institutional capacity; effective institutional management processes are critical for enhancing operational efficiency.

- 7.

- Coordination; a lead agency is required to coordinate with key departments involved in implementation.

- 8.

- Monitoring and evaluation; a robust monitoring and evaluation system is essential for continuous improvement of the implementation process.

- 9.

- External environment; impact of political, social, and economic environment needs to be managed appropriately for successful implementation.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LMICs | Low- and middle-income countries |

| HICs | High-income countries |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| UN | United Nations |

| ITF | International Transport Forum |

| UK | United Kingdom |

| TZD | Towards Zero Deaths |

| WRI-India | World Resources Institute India |

| NASSCOM | National Association of Software and Service Companies |

| ETSC | European Transport Safety Council |

| SUPREME | Support for European Road Safety Performance Indicators |

| ODI | Overseas Development Institute |

| IEG | Independent Evaluation Group |

| ITS | Intelligent transport systems |

| GRSA | Gujarat Road Safety Authority |

| MVAA | Motor Vehicles Amendment Act |

Appendix A

| Categories and Subcategories | Files | References |

|---|---|---|

| Implementation barriers | 9 | 241 |

| Cultural | 9 | 66 |

| Professional opposition | 8 | 9 |

| Poor road safety culture | 9 | 41 |

| Culture of bribery and corruption | 9 | 13 |

| Culture of not following road safety rules | 8 | 9 |

| Culture of over speeding | 9 | 10 |

| Victim blaming culture | 8 | 9 |

| Low literacy rates | 8 | 8 |

| Resistance to change | 8 | 8 |

| Institutional | 9 | 82 |

| Human resource issues | 9 | 26 |

| Lack of skilled HRs | 8 | 8 |

| Inadequate staffing | 8 | 11 |

| High staff turnover | 7 | 7 |

| Weak research capacity | 8 | 33 |

| Lack of research studies | 8 | 15 |

| Unreliable databases | 8 | 9 |

| Poor data management system | 7 | 9 |

| Poor technological capacity | 7 | 14 |

| Inadequate speed cameras | 7 | 7 |

| Manual systems | 7 | 7 |

| Lack of coordination | 8 | 9 |

| Operational | 8 | 53 |

| Challenges incorporating vision zero components | 8 | 30 |

| Strong opposition to safe speed | 7 | 7 |

| Road crashes are not investigated | 8 | 8 |

| Unsafe road infrastructure | 7 | 8 |

| Poor enforcement | 7 | 7 |

| Lack of ambulances | 7 | 7 |

| Poor and complicated management processes | 8 | 8 |

| Logistical issues | 7 | 8 |

| Financial | 8 | 26 |

| Unsustainable private-sector funding | 8 | 10 |

| Delayed allocation of government funds | 7 | 7 |

| Inadequate funds | 8 | 9 |

| Political | 7 | 14 |

| Lack of political will | 7 | 7 |

| Lack of support from the bureaucracy | 7 | 7 |

Appendix B

| Categories and Subcategories | Files | References |

|---|---|---|

| Implementation enablers | 9 | 148 |

| Institutional | 8 | 33 |

| Human resources | 7 | 8 |

| Capacity building | 5 | 8 |

| Research studies | 8 | 9 |

| Building reliable database | 6 | 8 |

| Collaborations | 4 | 8 |

| Operational | 9 | 89 |

| Incorporation of vision zero components | 7 | 26 |

| Enforcement | 8 | 12 |

| Awareness creation | 9 | 14 |

| Continuous consultation | 5 | 11 |

| Action planning | 7 | 13 |

| Modeling | 9 | 11 |

| Networked coordination | 8 | 10 |

| Regular review meetings | 8 | 18 |

| Financial | 6 | 14 |

| Availability of funds | 6 | 14 |

| Political | 7 | 12 |

| Strong political support from the beginning and during implementation | 7 | 12 |

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). Global Status Report on Road Safety 2023; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO); United Nations Regional Commissions. Global Plan for the Decade of Action for Road Safety 2021–2030; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- International Transport Forum (ITF). The Safe System Approach in Action; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Safarpour, H.; Khorasani-Zavareh, D.; Soori, H.; Ghomian, Z.; Bagheri-Lankarani, K.; Mohammadi, R. The Challenges of vision zero Implementation in Iran: A Qualitative Study. Front. Future Transp. 2022, 3, 884930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.N.; Das, S. Advancing traffic safety through the Safe System approach: A systematic review. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2024, 199, 107518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitelegg, J.; Haq, G. Vision Zero: Adopting a Target of Zero for Road Traffic Fatalities and Serious Injuries; Stockholm Environment Institute: Stockholm, Sweden, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Johansson, R. Vision zero—Implementing a policy for traffic safety. Safety Sci. 2009, 47, 826–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza, A.; Wybourn, C.; Mendoza, M.; Cruz, M.; Juillard, C.; Dicker, R. The Worldwide Approach to vision zero: Implementing Road Safety Strategies to Eliminate Traffic-Related Fatalities. Curr. Trauma Rep. 2017, 3, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD/ITF. Road Safety Annual Report; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Weijermars, W.; Wegman, F. Ten years of Sustainable Safety in the Netherlands: An assessment. Transp. Res. Rec. 2011, 2213, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Elvik, R.; Nævestad, T.O. Does empirical evidence support the effectiveness of the Safe System approach to road safety management? Accid. Anal. Prev. 2023, 191, 107227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoukrallah, R. Road Safety in Five Leading Countries; ACT Department of Territory and Municipal Services: Canberra, Australia, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- WRI India. Haryana Vision Zero; WRI India: Haryana, India, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gururaj, G.; Gautham, M. Advancing Road Safety in India—Implementation is the Key; National Institute of Mental Health & Neuro Sciences: Bengaluru, India, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Tingvall, C. Europe and Its Road Safety Vision—How Far to Zero? European Transport Safety Council. 2005. Available online: https://archive.etsc.eu/documents/7th_Lecture_vision_zero.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2023).

- Khorasani-Zavreh, D.; Mohammadi, R.; Khankeh, H.; Laflamme, L.; Bikmoradi, A.; Haglund, B. The requirements and challenges in preventing of road traffic injury in Iran: A qualitative study. BMC Public Health 2009, 9, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heydari, S.; Hickford, A.; Mcllroy, R.; Turner, J.; Bachani, A. Road Safety in Low-Income Countries: State of Knowledge and Future Directions. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, I. Beyond ‘best practice’ road safety thinking and systems management—A case for culture change research. Safety Sci. 2010, 48, 1175–1181. [Google Scholar]

- ETSC. A Methodological Approach to National Road Safety Policies: Evaluation of Road Safety Policies in the SEC Belt Countries; European Transport Safety Council: Brussels, Belgium, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- SUPREME. Best Practices in Road Safety: Handbook for Measures at the Country Level; European Commission, Directorate-General for Transport and Energy: Brussels, Belgium, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Tetali, S.; Josyula, L.; Gupta, S. Qualitative study to explore stakeholder perceptions related to road safety in Hyderabad, India. Injury 2013, 44, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Nunez, R.; Híjar, M.; Alfredo, C.; Hidalgo-Solórzano, E. Road traffic injuries in Mexico: Evidences to strengthen the Mexican road safety strategy. Rep. Public Health 2014, 30, 911–925. [Google Scholar]

- ODI/WRI. Securing Safe Roads; ODI: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Federative Republic of Brazil: National Road Safety Capacity Review; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Yannis, G.; Vasiljevic, J.; Milotti, A. Significance of the ROSEE Project—Road Safety in South East European Regions. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Road Safety in the Local Community, Valjevo, Serbia, 18–20 April 2013. [Google Scholar]

- IEG/World Bank. Making Roads Safer: Learning from the World Bank’s Experience; World Bank Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hyder, A.; Vecino-Ortiz, A. BRICS: Opportunities to improve road safety. Bull. World Health Organ. 2014, 92, 423–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaffron, P. The implementation of walking and cycling policies in British local authorities. Transp. Policy 2003, 10, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, B. Implementing the safe system approach to road safety: Some examples of infrastructure-related approaches. In Proceedings of the 16th International Conference Road Safety on Four Continents, Beijing, China, 15–17 May 2013. [Google Scholar]

- WRI. Sustainable & Safe: A Vision and Guidance for Zero Road Deaths; WRI.org: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Khanal, M.; Sarkar, P. Road Safety in Developing Countries. J. Civ. Environ. Eng. 2014, 2, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegman, F.; Eksler, V.; Hayes, S.; Lynam, D.; Morsink, P.; Oppe, S. SUNflower+6. A Comparative Study of the Development of Road Safety in the SUNflower+6 Countries: Final Report; SWOV: Leidschendam, The Netherlands, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Mojarro, F.; Solorzano, E.; Monreal, M. Challenges that hinder the application of the road safety regulation: A local law enforcement (LLE) officer’s perspective in Mexico. Inj. Prev. 2018, 24 (Suppl. 2), A65.2–A65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, R.; Afroz, S.; Khayesi, M.; Peden, M.; Híjar, M.; Odero, W.; Jha, A.; John, D.; Saran, A.; White, H.; et al. Effectiveness of road safety interventions: An evidence and gap map. Campbell Syst. Rev. 2024, 20, e1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PIARC Technical Committee 3. 1.1. Road Safety Manual: A Guide for Practitioners, 2nd ed.; World Road Association (PIARC): Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Erdelean, I.; Schaub, A.; Yannis, G.; Roussou, J. Road safety in low- and middle-income countries: Analysis and recommendations. In Proceedings of the Transport Research Arena (TRA) 2024 Conference, Dublin, Ireland, 15–18 April 2024; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Godthelp, H.; Ksentini, A. Specific road safety issues in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs): An overview and some illustrative examples. Traffic Saf. Res. 2023, 8, 26323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perel, P.; Ker, K.; Ivers, R.; Blackhall, K. Road safety in low- and middle-income countries: A neglected research area. Inj. Prev. 2007, 13, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walt, G.; Gilson, L. Reforming the health sector in developing countries: The central role of policy analysis. Health Policy Plan. 1994, 9, 353–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipsky, M. Street-Level Bureaucracy: Dilemmas of the Individual in Public Services, 2nd ed.; Russell Sage Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Birkland, T.A. An Introduction to the Policy Process: Theories, Concepts, and Models of Public Policy Making, 3rd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Brynard, P.A.; de Coning, C. Policy implementation. In Improving Public Policy: From Theory to Practice, 2nd ed.; Cloete, F., Wissink, H., de Coning, C., Eds.; Van Schaik Publishers: Pretoria, South Africa, 2006; pp. 179–191. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, M.N.K.; Lewis, P.; Thornhill, A. Research Methods for Business Students, 9th ed.; Pearson Education: Harlow, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 4th ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Urban Voices. Gujarat’s Vision 2030: Reimagining Road Safety for a Safer Tomorrow. Available online: https://urbanvoices.in/gujarats-vision-2030-reimagining-road-safety-for-a-safer-tomorrow/ (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- Kerala Public Works Department. Safe Corridor Demonstration Project under Mission Zero Accidents. Kerala State Transport Project Website. Available online: https://multimedia.3m.com/mws/media/1656977O/case-study-on-indias-first-safe-corridor-project-in-kerala.pdf (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- Farquhar, J.D. Case Study Research for Business; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Guest, G.; Bunce, A.; Johnson, L. How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods 2006, 18, 59–82. [Google Scholar]

- Graneheim, U.H.; Lundman, B. Qualitative Content Analysis in Nursing Research: Concepts, Procedures and Measures to Achieve Trustworthiness. Nurse Educ. Today 2004, 24, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, H.F.; Shannon, S.E. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Grbich, C. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Introduction, 2nd ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013; pp. 120–150. [Google Scholar]

- Pope, C.; Ziebland, S.; Mays, N. Qualitative research in health care. Analysing qualitative data. BMJ 2000, 320, 114–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, G.; Namey, E.; Chen, M. A simple method to assess and report thematic saturation in qualitative research. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0232076. [Google Scholar]

- Krippendorff, K. Reliability in content analysis: Some common misconceptions and recommendations. Hum. Commun. Res. 2004, 30, 411–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guba, E.; Lincoln, Y. Competing paradigms in qualitative research. In Handbook of Qualitative Research, 1st ed.; Norman, K.D., Yvonna, S.L., Eds.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994; pp. 105–117. [Google Scholar]

- Bryman, A. Social Research Methods, 5th ed.; Oxford University Press: London, UK, 2012; pp. 134–156. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. The High Toll of Road Traffic Injuries: Unacceptable and Preventable; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Tingvall, C. Vision Zero: Setting a global agenda. In The Vision Zero Handbook: Theory, Technology and Management for a Zero Casualty Policy; Edvardsson Björnberg, K., Hansson, S.O., Belin, M.-Å., Tingvall, C., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- UNECE. Road Safety for All: The UN Sustainable Development Goals; UNECE: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Greenhalgh, T.; Wherton, J.; Papoutsi, C.; Lynch, J.; Hughes, G.; A’Court, C.; Hinder, S.; Fahy, N.; Procter, R.; Shaw, S. Beyond Adoption: A New Framework for Theorizing and Evaluating Nonadoption, Abandonment, and Challenges to the Scale-Up, Scale-Up, Spread, and Sustainability of Health and Care Technologies. J. Med. Internet Res. 2017, 19, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dimension | Vision Zero Approach | Safe System Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Objectives and Targets | Eliminate fatalities and serious injuries; long-term zero-death vision anchored in the ethical imperative that no death or serious injury is acceptable on road transport system and ambitious road safety target. | Minimize fatal and serious injuries; build a forgiving system to accommodate human error. |

| Inputs (Principles and Policy Components) | Foundational principles: human fallibility, biomechanical limits, shared responsibility, ethical imperative. | Foundational principles: human fallibility, biomechanical limits, shared responsibility, system resilience. |

| Implemented through formal government commitments: laws, city-level mandates, strategic plans. | Technical guidelines: structured around the five-pillar framework: road safety management, safer roads and mobility, safer vehicles, safer road users and post-crash response. | |

| Responsibility (Actors) | Responsibility is shared but ultimate accountability lies with system designers and political leadership. | Responsibility is shared between road users and system designers. |

| Implementation Resources | Public investment in speed management: separation and integration infrastructure measures including tunnels, barriers, and dedicated lanes, vehicle safety, behavior change and post-crash response. | Coordinated resources across five pillars: roads, vehicles, users, speed, and post-crash care. |

| Outcomes | Reduced fatalities and serious injuries; cultural shift toward moral accountability and safe mobility. | System-wide reduction in crash severity; improved survivability; institutionalized safety culture. |

| Category | Role and Organization Type | The Rationale for Participant Selection | |

|---|---|---|---|

| IP1 | Independent researcher and academic | Professor in a major Swedish University and consultant | One of the main architects of Vision Zero and Former Director of road safety in public administration. Introduced vision zero in Sweden and was involved in the development of vision zero since the beginning. |

| IP2 | Government official | Senior Policy Advisor at Transport Administration | Safe system expert. He has seen vision zero established and flourished in Sweden since the beginning. Experience of 26 years with vision zero. |

| IP3 | Government official and academic | Senior Advisor at Transport Administration | Safe system expert. Written numerous research reports and articles on vision zero. Involved in the development of vision zero since the beginning. |

| IP4 | Government official and academic | Academic and Director at the Transport Administration | Involved with the development of vision zero since the beginning. Written numerous research reports and articles on vision zero. |

| IP5 | Independent researcher | Academic role at a major Swedish University | An active researcher in the safe system approach in Sweden. |

| IP6 | Academic and independent researcher | Professor at a major Swedish University | A researcher in the safe system approach. Written numerous research reports and articles on the vision zero approach. |

| IP7 | Government official | Senior Policy Advisor at Transport Administration | Safe system expert. Over 20 years of experience with vision zero policy. |

| Category | Role and Organization Type | The Rationale for Participant Selection | |

|---|---|---|---|

| IP8 | Independent researcher | Director role on urban transport in a major research organization | Overall responsibility of road safety section. Organized training for Road safety associates of Haryana vision zero. Involved in all meetings of Haryana vision zero. Written articles about Haryana vision zero. |

| IP9 | Independent researcher | Managerial role on city sustainability in major research organization | Currently working on the Indian state of Haryana—vision zero program |

| IP10 | Independent researcher | Project Associate in a major research organization | Currently working on Road safety projects in India |

| IP11 | Independent researcher | Managerial role in a major research organization | Working on Road safety |

| IP12 | Independent researcher—Global | Leadership role in a major research organization | Road safety expert and written articles and published reports on vision zero. Works on global strategy for addressing road safety issues. |

| IP13 | Academic and independent researcher | Professor at a major Indian University. | Expert in the safe system approach. Over 18 years of experience working closely with state governments to support road safety policies |

| IP14 | Academic and independent researcher | Professor at a major Indian University. | Safe system expert. Experience in capacity building on road safety. |

| IP15 | Government official | Senior Policy Advisor | Involved in the development of Haryana Vision Zero. Written numerous research reports and articles on vision zero. |

| IP16 | Government official | Senior Policy Advisor | Safe system expert. Written research articles and reports on the vision zero approach. |

| Categories | Sub-Categories | Haryana | Sweden | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cultural | Bribery and corruption | ✓ | ✕ | India’s road safety enforcement was weakened due to corruption and bribery. This allowed violations such as unregulated licensing. |

| Non-compliance with road safety rules | ✓ | ✕ | Road users in India frequently disregarded road safety rules and regulations. In contrast, Sweden had a strong culture of compliance that contributed to the successful implementation of their road safety measures. | |

| Overspeeding | ✓ | ✓ | Both India and Sweden experienced resistance to the proposed speed limits. Overspeeding in India was prevalent due to the weak enforcement mechanisms. While there was generally a strong compliance to road safety rules in Sweden, some road users resisted the speed regulations. | |

| Traditional mentality | ✓ | ✓ | In both cases, professionals resisted the systematic approach to road safety. Traditional road safety professionals focused on behavioral-based strategies. Additionally, road engineers, system designers, economists, and cost-to-benefit analysts in Sweden opposed the systematic approach. | |

| Luck culture | ✓ | ✕ | In India, road authorities attributed road accidents to luck, rather than preventable factors. In contrast, Sweden relied on data to develop and implement evidence-based road safety measures. | |

| Low literacy rates | ✓ | ✕ | Low literacy rates in India prevented the public from understanding the vision zero concept. In contrast, good education and high literacy rates ensured that the public in Sweden easily understood the vision zero concept. | |

| Institutional | Poor coordination | ✓ | ✕ | Poor coordination between road safety institutions such as the police and hospitals in India led to fragmented data and compromised the accuracy of the road safety database. In contrast, Sweden maintained strong inter-agency coordination and communication, ensuring accurate data reporting. |

| Human resource issues | ✓ | ✕ | India faced a shortage of qualified staff and a high turnover rate. In contrast, Sweden had a competent workforce that could effectively implement the vision zero initiatives. | |

| Poor technological capacity | ✓ | ✓ | Both India and Sweden experienced challenges with technology. Initially, the number of speed cameras was inadequate to effectively enforce safe speeds. The number of speed cameras were gradually increased in Sweden while India continued to struggle with manual issuance of penalties. | |

| Weak research capacity | ✓ | ✕ | India failed to conduct case studies on road crashes, had poor data management practices and unreliable databases. In contrast, Sweden had structured research strategies that ensured data-driven road safety measures. | |

| Political | Lack of political will and political interference | ✓ | ✓ | Expansion of the vision zero approach in India was hampered by the unwillingness of the government in Punjab to fund the initiative. In Sweden, politicians often interfered in technical decision-making including setting speed limits. Additionally, shifting political priorities affected the continuity of project implementation. |

| Operational | Complicated management processes | ✓ | ✕ | In India, long and complicated approval processes delayed the implementation of road safety measures. In contrast, Sweden did not experience such challenges. |

| Lack of synergy | ✓ | ✕ | In India, a lack of communication between different departments resulted in disjointed efforts. This fragmentation complicated the implementation process. In contrast, the relevant departments in Sweden coordinated effectively to achieve road safety goals. | |

| Challenges incorporating vision zero components | ✓ | ✕ | India experienced significant difficulties incorporating vision zero components due to cultural and institutional factors. The prevalent culture of overspeeding hindered the implementation of speed limits, the understaffed police department struggled to enforce road safety rules and roads lacked dedicated spaces for vulnerable road users. Sweden, successfully integrated all vision zero components. | |

| Lack of ambulances | ✓ | ✕ | In India, emergency response services were severely affected by inadequate and poorly maintained ambulances whereas Sweden had a well-developed emergency service that improved outcomes. | |

| Poor driving license management system | ✓ | ✕ | India’s unregulated driving license management system allowed road users to obtain and operate licenses without proper training. In contrast, Sweden did not report such issues. | |

| Logistical issues | ✓ | ✕ | In India, implementers faced logistical challenges, including poor internet access and the difficulty of reaching remote locations. In contrast, Sweden did not face similar issues. | |

| Financial | Financial resource issues | ✓ | ✓ | Both India and Sweden experienced challenges with financial resources. In India, funding was often inadequate, unsustainable and not always allocated at the right time. The funds were also subject to external environmental factors, making them unreliable. In Sweden, shifting government priorities affected the consistency of financial allocation for road safety initiatives. |

| Categories | Sub-Categories | Haryana | Sweden | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cultural | Safety culture | ✕ | ✓ | Sweden had a strong culture of following road safety rules and regulations. This culture was promoted by leaders modeling safe behavior. Sweden also had professional culture of discussing new things and giving value to human life. In contrast, India struggled with widespread non-compliance with road safety rules. |

| High literacy rate | ✕ | ✓ | In Sweden, good education and high literacy rates facilitated public understanding and subsequently buy-in and commitment to the vision zero initiative. In contrast, the low literacy rates in India making promotion of road safety and policy implementation challenging. | |

| Acceptance to change | ✕ | ✓ | The public acceptance, support, and commitment in Sweden allowed for smooth implementation of safer road measures. In contrast, the widespread resistance faced in India slowed down the implementation process and enforcement efforts. | |

| Institutional | Human resources | ✕ | ✓ | Sweden had access to road safety experts right from the start and high retention rates. This led to a successful implementation process, continuity and stability of their road safety initiatives. In contrast, India suffered from a shortage of skilled personnel and high turnover rates. These hindered the effective implementation of road safety measures. |

| Strong research capacity | ✕ | ✓ | Sweden’s in-depth crash investigations, and a reliable database supported the development of evidence-based road safety measures. In contrast, India had a weak research capacity, which limited the quality of data for informed decision-making in road safety. | |

| Strong technological capacity | ✕ | ✓ | Sweden coordinated with the car industry to collect data from car technologies like event recorders, seatbelt reminders, and electronic stability control. This data helped develop effective road safety interventions. India, on the other hand, gradually embraced the use of technology to enhance data collection. | |

| Collaborations | ✓ | ✓ | Both cases collaborated with universities and research institutions to strengthen their road safety research capacity. | |

| Operational | Coordination Structure | ✓ | ✓ | Sweden adopted a networked coordination approach where each stakeholder contributed towards the achievement of the broader goal. SRA, the lead agency, provided oversight. On the other hand, India utilized a hierarchical structure with different levels of decision-making and clearly defined roles and responsibilities |

| Continuous stakeholder consultation | ✓ | ✓ | Both cases engaged top government officials and stakeholders throughout the implementation process. India structured its consultation through the national workshop and presentation to top officials and involvement in developing action plans. In Sweden, the vision zero proposal was prepared by the ministry of transport in consultation with key stakeholders. It was then presented to parliament, and the outcome was parliament approval. All relevant stakeholders were consulted on developing potential interventions to road safety challenges. | |

| Modeling | ✓ | ✕ | India modeled the implementation process at the state and district level. This helped to produce data to inform the expansion process. The vision zero project was first modelled in 10 districts within Haryana before being scaled up to all the 23 districts and to other states. | |

| Action planning | ✓ | ✓ | In both cases, action plans were developed to ground the implementation process on the core components and principles. The action plans consisted of the vision zero components, objectives, quantified KPIs, and quantified targets. | |

| Enforcement | ✓ | ✓ | Enforcement was a key component of road safety strategies in both cases. Sweden began with manual enforcement and gradually transitioned to technological enforcement by installing speed cameras. However, enforcement was not considered a long-term sustainable solution, and engineering became the major focus of vision zero. Similarly, law enforcement officers in India were proactive and effective in enforcing road traffic rules, monitoring high-risk areas, and ensuring compliance with safety regulations. | |

| Awareness creation and education | ✓ | ✓ | Both cases placed significant emphasis on creating awareness and developing education programs to promote safer road user behavior. Sweden implemented educational campaigns and public awareness programs to ensure that road users understood the importance of road safety and their roles in achieving vision zero. Similarly, India invested in zero-tolerance day, media buzz and roadside events. | |

| Monitoring | ✓ | ✓ | Both cases held monthly and quarterly meetings to track implementation progress. Performance was measured by comparing indicators against previous meetings. Reports were published, and feedback was provided to the concerned departments to ensure continuous improvement. | |

| Financial | Availability of funds | ✓ | ✓ | Both cases received funding from government and the private sector to facilitate the implementation of road safety projects and hire the right people. Sweden received additional funds from NGOs |

| Cost-to benefit analysis | ✕ | ✓ | Sweden conducted cost-to-benefit analysis to identify and allocate funds to cost efficient projects ensuring effective use of resources. India lacked a clear funding allocation framework. | |

| Political | Strong political support | ✓ | ✓ | The vision zero approach received strong political support in both cases. In Sweden, top political leaders took the lead role in promoting vision zero. In India, decision-makers were willing to implement vision zero because it as a politically attractive idea. The government supported the initiative by launching the project and allocating funding. |

| Conceptual Framework Components | Barriers in Haryana (India) | Barriers in Sweden |

|---|---|---|

| Objectives and targets | Unrealistic, complex and costly targets Long-term process | Unrealistic objectives Long-term process |

| Resources | Inadequate funding Unsustainable funding Delayed allocation of funds Lack of skilled human resources Inadequate staffing High staff turnover Lack of ambulances | Lack of a dedicated budget Unsustainable funding Lack of a dedicated team Delay in the allocation of funds |

| Policy components | Unsafe road infrastructure Non-compliant road user’s behavior Vehicle safety yet to be incorporated | Non-compliant road user behavior |

| Implementers and key stakeholders | Lack of support from the bureaucracy Lack of support from engineering dept. Lack of political will in Punjab Lack of motivation and commitment Resistance to change by stakeholders Victim-blaming mindset Resistance to speed limits Lack of road safety awareness | Professional conflict Lack of support from the engineering dept. Political parties had different ideas Opposition from economists Opposition from Behaviorists Opposition from research institutions Resistance to change Victim-blaming mindset Opposition to safe speed Weak institutionalization by STA |

| Implementation process | Complicated management approval process Poor driving license management Complex administrative procedures | Professional opposition Police withdrew their activities Losing momentum |

| Institutional capacity | Weak research capacity Lack of road safety research Unreliable databases Road crashes are not investigated Accidents are not researched Underreporting of accidents Incomplete data entries Ineffective coordination system Poor technological capacity Inadequate speed cameras Manual issuing of penalties | Wastage of resources during the restructuring |

| Coordination | Poor coordination between government agencies | Lack of commitment resulting in internal conflict |

| Monitoring and evaluation | Ineffective evaluation due to lack of data and research | Negative feedback upset some stakeholders |

| External environment | Resistance to change Poor road safety culture Culture of not following road safety rules Culture of over speeding Culture of bribery and corruption Victim blaming culture Low literacy rates Treating road accidents as a matter of luck | Political interference Changing political priorities Resistance to change Professional resistance Opposition from some members of the public Opposition from middle-aged men |

| Conceptual Framework Components | Enablers in Haryana (India) | Enablers in Sweden |

|---|---|---|

| Objectives and targets | Relevant and aligned with the road safety needs in India Measurable through report cards, dynamic charts, and performance ranking | Taking small steps Relevant to road safety management needs in Sweden Quantifiable targets |

| Resources | Availability of state and private sector funds Availability of related skills (civil engineering, architecture, and urban planning) | Availability of funds from govt., private sector and NGOs Cost-to-benefit analysis Availability of highly qualified staff Employee retention |

| Policy components | Promoting safe behavior through awareness and enforcement Conducting crash investigations | Safe-infrastructure; two-plus one roads, roundabouts, speed bumps etc. Safe speed Safe vehicles Promoting safe behavior through awareness and enforcement Conducting crash investigations |

| Implementers and key stakeholders | Approval from the chief minister Government funding Own funding by WRI Support by the private sector Enforcing road safety rules by Police Raising awareness through conferences and workshops | Political support Support from politicians Support from the local government Support from the national govt. Gradual support from the car industry Shared responsibility Support from the media Enforcing road safety rules by Police Raising awareness |

| Implementation process | Continuous consultation with the bureaucracy Modeling Evidence-based expansion Government approval Crash investigations | Continuous consultation Parliament approval Constituting a team of experts Developing an action plan Objectives Key performance indicators Targets Core components Team effort |

| Institutional capacity | Collaboration with universities Geo-location databases Crash investigations Building road safety databases Capacity building | Strong research capacity In-depth research studies Conducting crash investigations A reliable road safety database Collaboration with research institutions Highly educated human resources |

| Coordination | Hierarchical coordination Liaising with hospitals for injury data | Lead agency managed implementation process Networked coordination All the stakeholders were involved Management by objectives |

| Monitoring and evaluation | Continuous monitoring and evaluation of road safety interventions Timely review meetings | Keeping track of progress Improvement of strategies Timely problem solving Informing future plans |

| External environment | Excellent political support from the local Govt Leadership by the Chief Minister of Haryana Promoting vision zero to Govt. agencies No legal issues | Excellent political support Politically attractive idea Safety culture Culture of following road safety rules Culture of giving value to human life Culture of discussing new ideas High literacy rate Supportive legal environment |

| Component | Most-Similar (Transferable Barriers) | Most-Different (Context-Specific Barriers) |

|---|---|---|

| Objectives and Targets | Unrealistic or overly ambitious targets; long-term nature of objectives | Haryana’s targets were perceived as complex and costly |

| Resources | Unsustainable funding; delays in allocation; lack of dedicated budget | Haryana faced acute shortages in skilled staff, ambulances, and high turnover; Sweden had access to highly qualified staff |

| Policy Components | Non-compliant road user behavior | Haryana lacked safe infrastructure and vehicle safety integration; Sweden had already addressed these areas systemically |

| Implementers and Stakeholders | Resistance to change; victim-blaming mindset; lack of support from engineering departments | Haryana faced bureaucratic inertia and low awareness; Sweden saw opposition from economists, researchers, and political factions |

| Implementation Process | Professional opposition; loss of momentum | Haryana struggled with license management and administrative complexity; Sweden’s police withdrew from activities midstream |

| Institutional Capacity | Coordination challenges | Haryana had unreliable crash data and poor tech capacity; Sweden faced restructuring inefficiencies but had stronger data systems |

| Coordination | Inter-agency friction and lack of alignment | Haryana’s coordination gaps were inter-agency (hospital-police); Sweden’s were intra-agency (internal conflict within departments) |

| Monitoring and Evaluation | Stakeholder sensitivity to negative feedback | Haryana lacked baseline data and research systems; Sweden had data but faced political discomfort with evaluation outcomes |

| External Environment | Resistance to change; cultural attitudes that hinder safety reforms | Haryana’s barriers included low literacy, corruption, and fatalism; Sweden’s included political interference and demographic opposition |

| Component | Most-Similar (Transferable Enablers) | Most-Different (Context-Specific Enablers) |

|---|---|---|

| Objectives and Targets | Relevance to national road safety needs; measurable and performance-linked targets | Haryana used dynamic charts and report cards; Sweden emphasized incrementalism and long-term quantifiable goals |

| Resources | Availability of public and private sector funding; presence of technical expertise | Sweden had cost–benefit analysis, high staff retention, and NGO support; Haryana faced skill gaps and turnover risks |

| Policy Components | Promotion of safe behavior through awareness and enforcement; crash investigations | Sweden had systemic integration of safe infrastructure, vehicles, and speed |

| Implementers and Stakeholders | Police enforcement and public awareness campaigns; multi-sectoral support emerging over time | Sweden had political buy-in across levels and media support; Haryana relied on state leadership and WRI’s catalytic role |

| Implementation Process | Continuous consultation and evidence-based expansion; crash investigations as feedback loops | Sweden’s process was formalized via parliamentary approval and expert teams; Haryana’s was more adaptive and bureaucratically negotiated |

| Institutional Capacity | Collaboration with universities and research institutions; crash data collection | Sweden had stronger research depth and reliable databases; Haryana used geo-location audits and was building capacity |

| Coordination | Multi-stakeholder involvement and liaison with health sector | Sweden had a lead agency and networked coordination; Haryana used hierarchical structures |

| Monitoring and Evaluation | Continuous tracking and timely reviews | Sweden had a well-developed monitoring system with quantifiable targets |

| External Environment | Strong political support and legal clarity | Sweden benefited from a safety culture and high literacy |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bajwa, M.U.; Saleh, W.; Fountas, G. Barriers and Enablers in Implementing the Vision Zero Approach to Road Safety: A Case Study of Haryana, India, with Lessons from Sweden. Infrastructures 2025, 10, 329. https://doi.org/10.3390/infrastructures10120329

Bajwa MU, Saleh W, Fountas G. Barriers and Enablers in Implementing the Vision Zero Approach to Road Safety: A Case Study of Haryana, India, with Lessons from Sweden. Infrastructures. 2025; 10(12):329. https://doi.org/10.3390/infrastructures10120329

Chicago/Turabian StyleBajwa, Mahfooz Ulhaq, Wafaa Saleh, and Grigorios Fountas. 2025. "Barriers and Enablers in Implementing the Vision Zero Approach to Road Safety: A Case Study of Haryana, India, with Lessons from Sweden" Infrastructures 10, no. 12: 329. https://doi.org/10.3390/infrastructures10120329

APA StyleBajwa, M. U., Saleh, W., & Fountas, G. (2025). Barriers and Enablers in Implementing the Vision Zero Approach to Road Safety: A Case Study of Haryana, India, with Lessons from Sweden. Infrastructures, 10(12), 329. https://doi.org/10.3390/infrastructures10120329