Research on Legal Risk Identification, Causes and Remedies for Prevention and Control in China’s Aquaculture Industry

Abstract

:1. Introduction

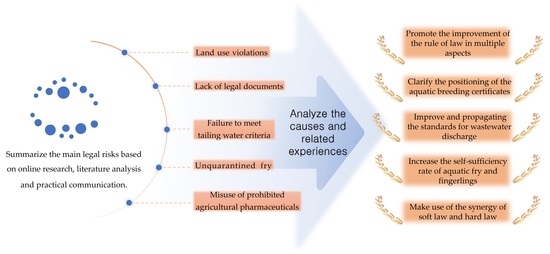

2. Legal Risk Identification in Aquaculture

2.1. Status of Administrative Penalties in Aquaculture

2.2. Legal Risks in Aquaculture

2.2.1. Legal Risk I: Property Rights Legal Risk

2.2.2. Legal Risk II: Licensing Legal Risks

2.2.3. Legal Risk III: Legal Risk No. 3: Wastewater Discharge Legal Risks

2.2.4. Legal Risk IV: Aquatic Fry and Fingerlings Legal Risk

2.2.5. Legal Risk V: Pharmaceutical Legal Risks

3. Causes of Legal Risk in Aquaculture

3.1. Objective Reasons

3.2. Subjective Reasons

4. Related Beneficial Experiences

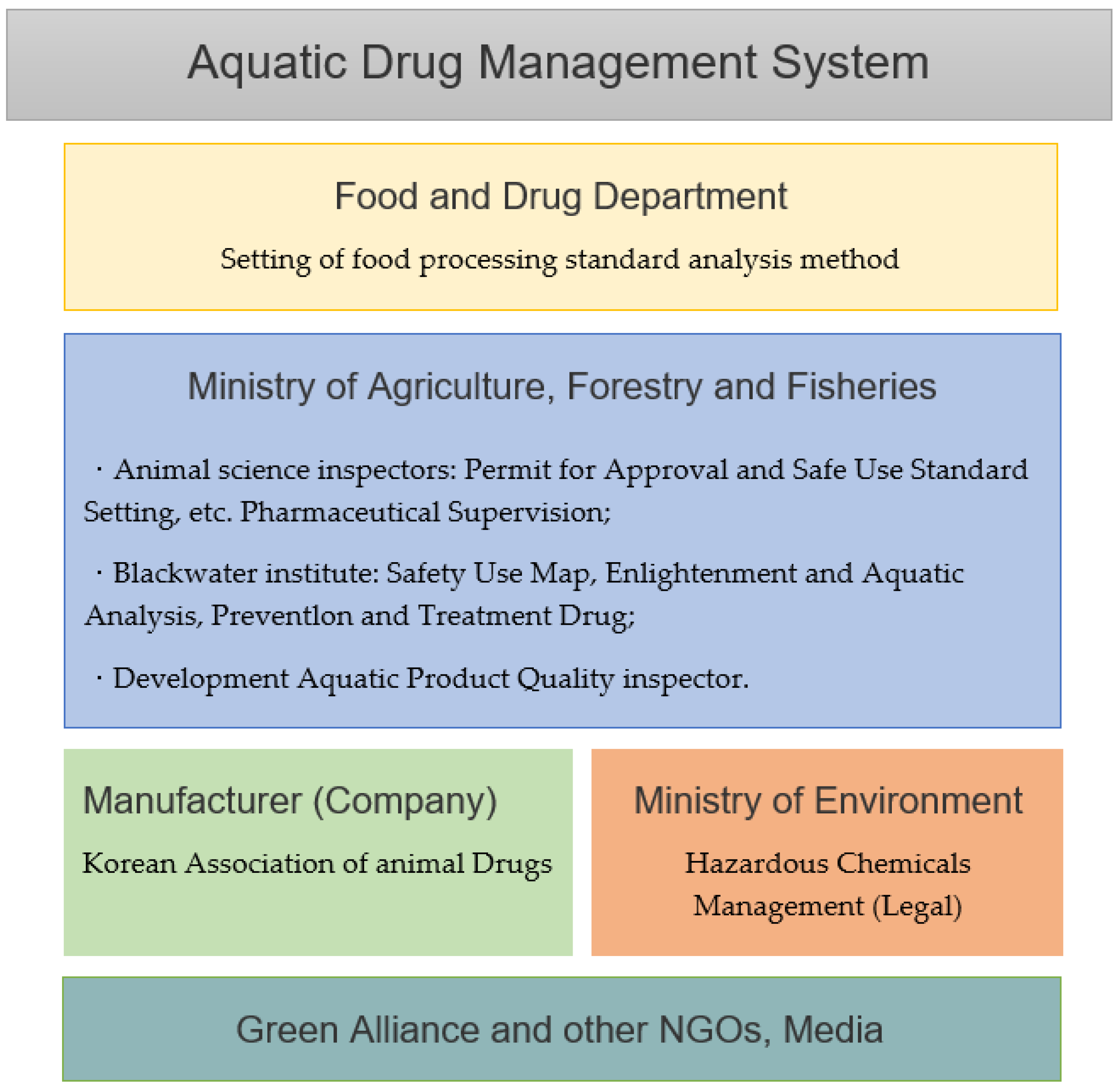

4.1. Korea

4.2. Norway

4.3. Chile

5. Preventing and Controlling Legal Risks in Aquaculture

5.1. Promote an Improved Rule of Law

5.1.1. Raise Legal Awareness among Operators

5.1.2. Follow the Principle of Proportionality and the Principle of Reliance Interests

5.1.3. Clear Guidance from Legislators

5.1.4. Upgrade of Government-Supported Aquaculture

5.2. Clarify the Positioning of Aquatic Breeding Certificates

5.3. Improve and Popularize Wastewater Discharge Standards

5.4. Increase the Self-Sufficiency Rate of Aquatic Fry and Fingerlings

5.5. Make Use of the Synergy of Soft Law and Hard Law

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FAO. World Review. In State of the World Fisheries and Aquaculture: Sustainability in Action, 1st ed.; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020; p. 5. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Executive Summary. In The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2022. Towards Blue Transformation, 1st ed.; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2022; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Noor, N.; Harun, S.N. Towards Sustainable Aquaculture: A Brief Look into Management Issues. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 7448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tacon, A.G.J. Trends in global aquaculture and aquafeed production: 2000–2017. Rev. Fish. Sci. Aquac. 2020, 28, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilborn, R.; Banobi, J.; Hall, S.J.; Pucylowski, T.; Walsworth, T.E. The environmental cost of animal source foods. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2018, 16, 329–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poore, J.; Nemecek, T. Reducing food’s environmental impacts through producers and consumers. Science 2018, 360, 987–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naylor, R.; Fang, S.; Fanzo, J. A global view of aquaculture policy. Food Policy 2023, 116, 102422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galparsoro, I.; Murillas, A.; Pinarbasi, K.; Sequeira, A.M.; Stelzenmüller, V.; Borja, A.; O’ Hagan, A.M.; Boyd, A.; Bricker, S.; Garmendia, J.M. Global stakeholder vision for ecosystem-based marine aquaculture expansion from coastal to offshore areas. Rev. Aquac. 2020, 12, 2061–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, D.; Balint, T.; Liversage, H.; Winters, P. Investigating the impacts of increased rural land tenure security: A systematic review of the evidence. J. Rural Stud. 2018, 61, 34–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hishamunda, N.; Ridler, N.; Martone, E. Policy and governance in aquaculture: Lessons learned and way forward. FAO Fish. Aquac. Tech. Pap. 2014, 577, I. [Google Scholar]

- Lawry, S.; Samii, C.; Hall, R.; Leopold, A.; Hornby, D.; Mtero, F. The impact of land property rights interventions on investment and agricultural productivity in developing countries: A systematic review. J. Dev. Eff. 2017, 9, 61–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, N.; Van der Meulen Rodgers, Y.; Nguyen, H. Women’s land rights and children’s human capital in Vietnam. World Dev. 2014, 54, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sayed, A.F.M. Regional review on status and trends in aquaculture development in the Near East and North Africa-2015. FAO Fish. Aquac. Circ. 2017, C1135, I. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, R.G. Coastal planning on the Atlantic fringe, north Norway: The power game. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2000, 43, 879–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokke, K. Municipal planning in sea areas–increasing ambitions for sustainable fish farming. Kart Og Plan 2017, 77, 219–230. [Google Scholar]

- Kvalvik, I.; Robertsen, R. Inter-municipal coastal zone planning and designation of areas for aquaculture in Norway: A tool for better and more coordinated planning? Ocean Coast. Manag. 2017, 142, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belton, B.; Filipski, M. Rural transformation in central Myanmar: By how much, and for whom? J. Rural Stud. 2019, 67, 166–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belton, B.; Hein, A.; Htoo, K.; Kham, L.S.; Nischan, U.; Reardon, T.; Boughton, D. A Quiet Revolution Emerging in the Fish-Farming Value Chain in Myanmar: Implication for National Food Security. 2015. Available online: https://ageconsearch.umn.edu/record/259801/ (accessed on 24 October 2023).

- Filipski, M.; Belton, B. Give a man a fishpond: Modeling the impacts of aquaculture in the rural economy. World Dev. 2018, 110, 205–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asche, F.; Eggert, H.; Oglend, A.; Roheim, C.A.; Smith, M.D. Aquaculture: Externalities and Policy Options. Rev. Environ. Econ. Policy 2022, 16, 282–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deniz, H.; Benli, A.C.K. Environmental Policies in Force and Its Effects on Aquaculture in Turkey. In Proceedings of the Workshop on the State-of-the-Art of ICM in the Mediterranean and the Black Sea, Mugla, Turkey, 14–18 October 2008; pp. 193–195. [Google Scholar]

- Dierberg, F.E.; Kiattisimkul, W. Issues, impacts, and implications of shrimp aquaculture in Thailand. Environ. Manag. 1996, 20, 649–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galland, D.; McDaniels, T. Are new industry policies precautionary? The case of salmon aquaculture siting policy in British Columbia. Environ. Sci. Policy 2008, 11, 517–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zajicek, P.; Corbin, J.; Belle, S.; Rheault, R. Refuting Marine Aquaculture Myths, Unfounded Criticisms, and Assumptions. Rev. Fish. Sci. Aquac. 2023, 31, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jianyuan, C. System of the Right to Use Maritime Space and Its Reflection. Trib. Political Sci. Law 2004, 22, 55–64. [Google Scholar]

- Available online: http://www.maxlaw.cn/htf-dlhtjflawer-com (accessed on 24 October 2023).

- Zhao, W. On National Legislative Perfection of Fishing Rights. J. Guangdong Ocean Univ. 2008, 28, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y. Government could issue both land use rights certificates and aquaculture certificates for the same aquaculture water surface. People’s Jurisd. 2011, 55, 50–52. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, L. Revision and improvement of the aquaculture license system to provide rule of law safeguards for the high-quality development of the fisheries industry. China Fish. 2021, 64, 50–52. [Google Scholar]

- Study on Difficult Issues in the Trial of Cases of Illegal Use of Sea Area. Available online: http://mp.weixin.qq.com/s?__biz=MzU3NTY0ODcwNA==&mid=2247485493&idx=1&sn=8abacee8c13821539235a018ac148fd5&chksm=fd1eae9aca69278c832d42f29d61dfcf29ad12ec546335d27baf3d5529e06fd0477efd78396b&mpshare=1&scene=1&srcid=0907cDsyoBOKpAkExHnbz8F4&sharer_shareinfo=87b800e9b94bb7958bba2daed9903d39&sharer_shareinfo_first=87b800e9b94bb7958bba2daed9903d39#rd (accessed on 24 October 2023).

- Engle, C.R.; Stone, N.M. Competitiveness of US aquaculture within the current US regulatory framework. Aquac. Econ. Manag. 2013, 17, 251–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Agostino, J. Posner’s Folly: The End Of Legal Pragmatism And Coercion’s Clarity. Br. J. Am. Leg. Stud. 2018, 7, 365–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthew, A. Trust, Social Licence and Regulation: Lessons from the Hayne Royal Commission. J. Bank. Financ. Law Pract. 2020, 31, 103–118. [Google Scholar]

- Tafani, L. Enhancing the quality of legislation: The Italian experience. Theory Pract. Legis. 2022, 10, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valles, C.; Pogoretskyy, V.; Yanguas, T. Challenging Unwritten Measures in the World Trade Organization: The Need for Clear Legal Standards. J. Int. Econ. Law 2019, 22, 459–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Júnior, C.A.M.; da Costa Luchiari, N.; Gomes, P.C.F.L. Occurrence of caffeine in wastewater and sewage and applied techniques for analysis: A review. Eclética Química, 2019; 44, 11–26. [Google Scholar]

- Naidu, R.; Jit, J.; Kennedy, B.; Arias, V. Emerging contaminant uncertainties and policy: The chicken or the egg conundrum. Chemosphere 2016, 154, 385–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Kurniawan, S.B.; Abdullah, S.R.S.; Othman, A.R.; Hasan, H.A. Contaminants of emerging concern (CECs) in aquaculture effluent: Insight into breeding and rearing activities, alarming impacts, regulations, performance of wastewater treatment unit and future approaches. Chemosphere 2022, 290, 133319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindmark, M.; Vikström, P. The determinants of structural change: Transformation pressure and structural change in Swedish manufacturing industry, 1870–1993. Eur. Rev. Econ. Hist. 2002, 6, 87–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, X.; Zhang, J.; Ding, J. Best management practices on non-point source pollution of aquaculture. South China Fish. Sci. 2012, 8, 79–86. [Google Scholar]

- Aquaculture Site Selection and Carrying Capacity Management in the People’s Republic of China. Available online: https://www.fao.org/fishery/docs/CDrom/P21/root/14.pdf (accessed on 24 October 2023).

- Wang, X.; Cuthbertson, A.; Gualtieri, C.; Shao, D. A review on mariculture effluent: Characterization and management tools. Water 2020, 12, 2991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottinger, M.; Clauss, K.; Kuenzer, C. Aquaculture: Relevance, distribution, impacts and spatial assessments–A review. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2016, 119, 244–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biosecurity in Aquaculture, Part 1: An Overview. Available online: https://thefishsite.com/articles/biosecurity-in-aquaculture-part-1-an-overview (accessed on 24 October 2023).

- Goel, A.D.; Bhardwaj, P.; Gupta, M.; Kumar, N.; Jain, V.; Misra, S.; Saurabh, S.; Garg, M.K.; Nag, V.L. Swift contact tracing can prevent transmission—Case report of an early COVID-19 positive case. J. Infect. Public Health 2021, 14, 260–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasan, S.S.; Kow, C.S.; Zaidi, S.T.R. Social distancing and the use of PPE by community pharmacy personnel: Does evidence support these measures? Res. Soc. Admin. Pharm. 2021, 17, 456–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortega, C.; Valladares, B. Analysis on the development and current situation of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) farming in Mexico. Rev. Aquac. 2017, 9, 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 7, U.S. Code § 8303—Restriction on importation or entry. Available online: https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/7/8303 (accessed on 24 October 2023).

- Palermo, D. A Ribbiting Proposal. Vermont J. Environ. Law 2021, 22, 77–99. [Google Scholar]

- Peeler, E.J.; Oidtmann, B.C.; Midtlyng, P.J.; Miossec, L.; Gozlan, R.E. Non-native aquatic animals introductions have driven disease emergence in Europe. Biol. Invasions 2011, 13, 1291–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittington, R.; Chong, R. Global trade in ornamental fish from an Australian perspective: The case for revised import risk analysis and management strategies. Prev. Vet. Med. 2007, 81, 92–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.C.D. The innovative development path of modern aquaculture seed industry in China. Res. Agric. Mod. 2021, 42, 377–389. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H. Several strategies for the modernization of the construction of the aquaculture seed industry silicon valley. Mar. Sci. 2018, 42, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, G.M. A Day on the Fish Farm: FDA and the Regulation of Aquaculture. Va. Environ. Law J. 2004, 23, 351–395. [Google Scholar]

- Antimicrobial Usage and Antimicrobial Resistance in Vietnam. Available online: https://dokumen.tips/documents/antimicrobial-usage-and-antimicrobial-resistance-in-usage-and-antimicrobial-resistance.html?page=1 (accessed on 24 October 2023).

- Mujeeb Rahiman, K.M.; Mohamed Hatha, A.A.; Gnana Selvam, A.D.; Thomas, A.P. Relative prevalence of antibiotic resistance among heterotrophic bacteria from natural and culture environments of freshwater prawn, Macrobrachium Rosenbergii. J. World Aquac. Soc. 2016, 47, 470–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rico, A.; Phu, T.M.; Satapornvanit, K.; Min, J.; Shahabuddin, A.; Henriksson, P.J.; Murray, F.J.; Little, D.C.; Dalsgaard, A.; Van den Brink, P.J. Use of veterinary medicines, feed additives and probiotics in four major internationally traded aquaculture species farmed in Asia. Aquaculture 2013, 412, 231–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rico, A.; Satapornvanit, K.; Haque, M.M.; Min, J.; Nguyen, P.T.; Telfer, T.C.; Van Den Brink, P.J. Use of chemicals and biological products in Asian aquaculture and their potential environmental risks: A critical review. Rev. Aquac. 2012, 4, 75–93. [Google Scholar]

- Tacon, A.G.; Metian, M. Aquaculture feed and food safety: The role of the food and agriculture organization and the Codex Alimentarius. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2008, 1140, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FAO; WHO. Aquaculture Production. In Code of Practice for Fish and Fishery Products, 1st ed.; WHO: Rome, Italy, 2020; p. 76. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y. The history and current situation of the development of aquatic animal protection industry. Curr. Fish. 2019, 44, 84–87. [Google Scholar]

- Li, N. Impact of fishery drugs on quality and safety of aquaculture products and countermeasures. Heilongjiang Anim. Sci. Vet. Med. 2017, 60, 283–285. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X. Strengthening the management of aquatic non-pharmaceuticals to promote the healthy development of aquaculture industry. Anhui Agric. Sci. Bull. 2019, 25, 63–64+76. [Google Scholar]

- Bei, Y.; Zhou, F.; Zhu, N.; Ma, W.; Ding, X. Problems and Suggestions in Production and Use of Water and Sediment Quality Improver for Aquaculture. Mod. Agric. Sci. Technol. 2019, 14, 212–214. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, L.W. Research on the Eligibility of Natural Resource Concession Guarantee-Based on Article 329 of the Civil Code. Res. Real Estate Law China 2022, 26, 121–136. [Google Scholar]

- Ruan, R.; Su, J.; Zheng, F. Use Right Confirmation and Rural Finance—An example of the impact of farming certificates on the availability of loans to fishermen. Econ. Perspect. 2017, 58, 53–67. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, F.W.; Dai, M.H.; Lin, S. Cultivated Land Protection Based on Bottom Line Thinking of Food Security: Current Situation, Difficulties and Countermeasures. Econ. Rev. 2022, 38, 9–16. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, R.H.; Pei, Z.B. On Perfecting the Legal System and Supervision Mechanism of Fishery Administrative Licensing. J. Shenyang Agric. Univ. 2020, 22, 348–353. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, Z.J.; Liu, X.G.; Cheng, G.F.; Wang, X.D. The effect of ecological ditches in the management of wastewater from freshwater pond culture and the technology of construction. Technol. Innov. Appl. 2019, 26, 127–132. [Google Scholar]

- Integrated Wastewater Discharge Standard. Available online: https://www.mee.gov.cn/ywgz/fgbz/bz/bzwb/shjbh/swrwpfbz/199801/t19980101_66568.shtml (accessed on 24 October 2023).

- Freshwater Pond Culture Water Discharge Requirements. Available online: https://www.doc88.com/p-1075432615259.html (accessed on 24 October 2023).

- Mariculture Water Discharge Requirements. Available online: https://max.book118.com/html/2019/1106/8070000006002062.shtm (accessed on 24 October 2023).

- Standard for Irrigation Water Quality. Available online: https://www.mee.gov.cn/ywgz/fgbz/bz/bzwb/shjbh/shjzlbz/202102/t20210209_821075.shtml (accessed on 24 October 2023).

- Environmental Quality Standards for Surface Water. Available online: https://www.mee.gov.cn/ywgz/fgbz/bz/bzwb/shjbh/shjzlbz/200206/t20020601_66497.shtml (accessed on 24 October 2023).

- Discharge Standard of Pollutants for Municipal Wastewater Treatment Plant. Available online: https://english.mee.gov.cn/Resources/standards/water_environment/Discharge_standard/200710/t20071024_111808.shtml (accessed on 24 October 2023).

- Yu, X.J. Stabilizing Aquaculture: An Analysis Based on National Fisheries Statistics. China Fish. 2023, 66, 22–25. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, J.Y.; Wang, J.; Sun, P.; Tang, B.J. Physiological response of Larimichthys crocea under different stocking densities and screening of stress sensitive biomarkers. Mar. Fish. 2021, 43, 327–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquaculture, the Concept of Disease Prevention Focused on Treatment Should be Changed. Available online: http://www.ysfri.ac.cn/info/2048/38463.htm (accessed on 24 October 2023).

- Guo, H.; Dong, X. Discussion on drug residues in aquaculture animals and aquatic product safety. J. Aquac. 2015, 36, 46–48. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Q.; Hu, K. Driving Forces and Equilibrium Analysis of Social Responsibilityin Marine Aquatic Products Supply Chain. Ocean Dev. Manag. 2016, 33, 50–54. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, W.; Luo, Q.; Liu, W.; Lin, Q.; Tu, J. Analysis and Countermeasure of the Problems of Drug Residues in Aquatic Product and Aquatic Feed. Fujian J. Agric. Sci. 2011, 26, 1096–1100. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Liu, X.; Ren, X.; Zhang, J.; Nelson, R.G. Drug residue issues of aquatic products export from China. In LISS 2014, Proceedings of 4th International Conference on Logistics, Informatics and Service Science; Springer: Berlin/Heildelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 1135–1141. [Google Scholar]

- Discussion on the Significance of Setting Group Standards for Water Adjustment Products in Aquaculture for the Development of Aquatic Science and Technology. Available online: https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/kcuDceuRX605ZlN4TR8edA (accessed on 24 October 2023).

- Rectification of fake drugs! Yang Xianle voice: The future of aquatic animal protection + fishing medicine is “0”. Available online: https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/JEYn2nDB63y1GemmPR_lKA (accessed on 24 October 2023).

- Chen, C.F.; Chen, H. Analysis of the Problem of Aquatic Non-pharmaceutical and Suggestions for Management in China. China Fish. 2018, 61, 99–100. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.F. Screening of Unlabeled Pesticide and Veterinary Drugs in Non-drugs Fishery Inputs and Its Impact on Aquaculture. Master’s Thesis, Shanghai Ocean University, Shanghai, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, Y. Exploring the key to aquaculture development in the new era from a multi-dimensional perspective. Mod. Agric. Mach. 2022, 40, 107–108. [Google Scholar]

- Aquaculture Industry Leaders Comprehensively Explain Aquaculture Development Trends, Cutting-Edge Technology. Available online: https://www.ixueshu.com/h5/document/03d3884ec484856c1defc7dec9f46d64318947a18e7f9386.html (accessed on 24 October 2023).

- Several Opinions on Accelerating the Green Development of Aquaculture. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2019-10/22/content_5443445.htm (accessed on 24 October 2023).

- Finance and Economics: Quality and Safety of Fish Products in China. Available online: https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/Rvu_FVaSQDmmqj0SnBd5Pg (accessed on 24 October 2023).

- Research Report on the Quality and Safety Status of Fish Products in China. Available online: https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/1PuhwKmL5nTwiAz7o1NT8A (accessed on 24 October 2023).

- The Aquaculture Safety Problems and Countermeasures Research of GangKou ZhongShan. Available online: http://www.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=CMFD&dbname=CMFD201701&filename=1017004568.nh&uniplatform=OVERSEA&v=kssYELNVfsT7uiCQODmbb72zkLln4t1n2yZsYEOwcCWbW2lrkao9Y4-xag6XfIoM (accessed on 24 October 2023).

- Deng, J.; Jia, B.; Zhao, Y.; Ma, H.; Cen, J.; Chen, S.; Yang, X.; Li, L. Application status and standard management of aquaculture inputs. J. Food Saf. Qual. 2023, 14, 200–206. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, H.; Xie, X. Jinxi:How aquaculture breaks through in the new normal. Jiangxi Agric. 2015, 34, 51. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, C.; Yuan, S. Research of aquatic products quality and safety problem in China based on circulation channel. Sci. Technol. Food Ind. 2014, 35, 275–279. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, I.B. Aquaculture–For Sustainable Systems of the Future. Korean Soc. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2015, 61, 306. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, K.; Wu, W. Main Measures for Efficient Development of Norwegian Mariculture and Lessons Learned from Experience. World Agric. 2016, 38, 190–193. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Liu, H.; Liu, X.; Lu, S.; Xu, Y.; Long, L.; Zhang, C. Reference from sustainable development of Norwegian Atlantic salmon industry to Chinese aquaculture. Fish. Inform. Strategy 2021, 36, 208–216. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, H.; Luo, S. Upgrading Path of Chilean Salmon Aquaculture Industry and Implications for the Development of China’s Mariculture Industry. Ocean Dev. Manag. 2010, 27, 83–88. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, B.R. Environmental status of aquaculture farms in Korea and countermeasures. China Fish. 2007, 50, 24–25. [Google Scholar]

- Ming, L. Developing Large-Scale Deep Sea Aquaculture: Problems, Modes and Realization Ways. Manag. World 2022, 38, 39–58. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, G.Q.; Ni, X.H.; Mo, J.S. Research Status and Development Tendency of Deep Sea Aquaculture Equipments: A Review. J. Dalian Ocean Univ. 2018, 33, 123–129. [Google Scholar]

- Fisheries and Aquaculture Country Profiles. Available online: https://www.fao.org/fishery/zh/facp/nor?lang=en (accessed on 24 October 2023).

- Li, Z. Study on Countermeasures for the Development of Deep-water Net-pen Aquaculture in Hainan Province. Rural Agric. Farmer 2023, 38, 22–24. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.; Wang, W.; Li, Q.; Fu, Q. Discussion on the development of deep-water net-pen aquaculture in Lingshui County, Hainan, China. Ocean Dev. Manag. 2015, 32, 49–52. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y.; Ju, X.; Chen, Y. Offshore cage aquaculture of China: Current situation, problems andcountermeasures. Chin. Fish. Econ. 2017, 35, 72–78. [Google Scholar]

- Thodesen, J.; Gjedrem, T. Breeding Programs on Atlantic Salmon in Norway: Lessons Learned. World Fish Cent. 2006, 73, 22–26. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.D.; Li, Y.X.; Jiang, Y.; Tian, J.Y.; Liu, X.Q.; Zhao, X.X.; Ma, J.; Du, W.; Hu, J.T. Pathway Analysis for Developing Modern Mariculture Under the Background of Oceanic Great Power Strategy. Ocean Dev. Manag. 2021, 38, 18–26. [Google Scholar]

- Gjedrem, T.; Robinson, N.; Rye, M. The Importance of Selective Breeding in Aquaculture to Meet Future Demands for Animal Protein: A Review. J. Aquac. 2012, 350, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishery and Aquaculture Country Profiles-Chile. Available online: https://www.fao.org/fishery/zh/facp/chl?lang=es (accessed on 24 October 2023).

- Basulto, S. El Largo Viaje de los Salmones. Una crónica olvidada. Propagación y cultivos de Especies Acuáticos en Chile. Not. Mus. Nat. Hist. Mon. Newsl. 2003, 352, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Evolution of the Aquaculture Environmental Regime in Chile. Available online: https://www.scielo.cl/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0718-68512014000100013 (accessed on 24 October 2023).

- Yu, H.G.; Liang, Z.L. Property rights arrangements and aquaculture development—The case of Mexico, Chile and Washington State, USA. Ocean Dev. Manag. 2006, 23, 145–149. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, C.L.; Gao, J.J. On the Successful Experience of the Atlantic Salmon Breeding in Chile. Ocean Dev. Manag. 2016, 33, 70–74. [Google Scholar]

- Rabellotti, R. Chile’s Salmon Industry: Policy Challenges in Managing Public Goods. Res. Policy 2017, 46, 898–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, P.; Kirsch, S. Capitalism and the Politics of Resignation. Curr. Anthropol. 2010, 51, 459–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Current Land Use Classification. Available online: http://c.gb688.cn/bzgk/gb/showGb?type=online&hcno=224BF9DA69F053DA22AC758AAAADEEAA (accessed on 24 October 2023).

- Zhou, H.X. Research on the Right to Use Inland Waters. Ph.D’s Thesis, Hunan University, Hunan, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Is It Allowed to Build Farms on General Arable Land or Not? The New Rules in 2022 Have Changed! Available online: https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/2IkE9yMWli5q9qD3HYUkGg (accessed on 24 October 2023).

- Zhu, G.M. Whether Land for Construction of Agricultural Facilities Requires Approval for Agricultural Land Conversion. China Land 2023, 444, 60. [Google Scholar]

- Judgment of the Second Instance of Deng Wencai v. Shimen County Natural Resources Bureau Land Administrative Punishment. Available online: https://wenshu.court.gov.cn/website/wenshu/181107ANFZ0BXSK4/index.html?docId=rnZKb0y5gfy2RR3+pd+HjOFhe99IWbLANum/yaGfazZ1an2gITk79Z/dgBYosE2g8gUOT8PqpyXZgHiZSnIM/jTFP25au9Azif75qfqTGRD8SME6W5nnHXuIZ5YpeFXW (accessed on 24 October 2023).

- Jiangsu Province Reclaims the Right to Use Taihu Lake for Aquaculture. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2018-04/16/content_5282806.htm (accessed on 24 October 2023).

- Yuan, Y. On the Definition of the Normative Document—Centered on the Constitutive Conditions and Identification Standards. Polit. Sci. Law 2021, 316, 114–130. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.B.; Liu, Y.S.; Shi, Y.H.; Yuan, X.C.; Wang, J.J.; Liu, J.Z.; Jia, C.P. Dynamic Changes of Water Quality During Wastewater Discharge Cycle of Different Aquaculture Varieties. Fish. Mod. 2023, 50, 26–33. [Google Scholar]

- Song, L.; Zhang, W.; Sun, X.; Liu, X.; Lu, Y.; Li, N.; Wang, Y. Tail Water of Aquatic Animal Culture: Control Strategy. J. Agric. 2019, 9, 59–64. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.F.; Zhou, X.J. Discussion of how aquaculture input production and sales enterprises should act to face the supervision of the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural. Curr. Fish. 2021, 46, 72–73+77. [Google Scholar]

- Bergleiter, S.; Meisch, S. Certification Standards for Aquaculture Products: Bringing Together the Values of Producers and Consumers in Globalised Organic Food Markets. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2015, 28, 553–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahuelhual, L.; Defeo, O.; Vergara, X.; Blanco, G.; Marín, S.L.; Bozzeda, F. Is There a Blue Transition Underway? Fish Fish. 2019, 20, 584–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villasante, S.; González, D.; Antelo, M.; Rodríguez, S.; de Santiago, J.A.; Macho, G. All Fish for China? J. Ambio. 2013, 42, 923–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Law | Content |

|---|---|

| Article 85(3) of the Pharmaceutical Affairs Law | A person who intends to use animal drugs shall observe the standards. |

| Article 3 of the Standard for the Safe Use of Veterinary Drugs | The matters to be observed by the user, including the target animals prescribed in the declaration license or the objects and usage and dosage. |

| Article 40(1) of the Aquatic Organism Disease Control Act | No aquaculture business entity and its worker shall use animal drugs which have not been approved or reported under Article 31(2) of Pharmaceutical Affairs Act and Article 85(1) of the same Act or hazardous chemical substances under subparagraph 7 of Article 2 of Chemical Substances Control Act: Provided, That the same shall not apply where he or she has obtained approval for use under other Acts, such as approval for use under the proviso of Article 25(2) of the Fishery Resources Management Act. |

| Article 98(10) of the Pharmaceutical Affairs Act | Any of the following persons shall be subject to an administrative fine of not more than one million won: a person who fails to observe the standards for use of drugs, etc. for animals, in violation of Article 85(3). |

| Article 53(9) of the Aquatic Animal Disease Management Act | Those who use veterinary drugs or dangerous chemicals in violation of Article 40(1) shall be punished by imprisonment of up to three years or a fine of up to 30 million won, and their crimes shall be prosecuted by the judicial police. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, C.; Liu, Y.; Pei, Z. Research on Legal Risk Identification, Causes and Remedies for Prevention and Control in China’s Aquaculture Industry. Fishes 2023, 8, 537. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes8110537

Xu C, Liu Y, Pei Z. Research on Legal Risk Identification, Causes and Remedies for Prevention and Control in China’s Aquaculture Industry. Fishes. 2023; 8(11):537. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes8110537

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Chang, Yang Liu, and Zhaobin Pei. 2023. "Research on Legal Risk Identification, Causes and Remedies for Prevention and Control in China’s Aquaculture Industry" Fishes 8, no. 11: 537. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes8110537

APA StyleXu, C., Liu, Y., & Pei, Z. (2023). Research on Legal Risk Identification, Causes and Remedies for Prevention and Control in China’s Aquaculture Industry. Fishes, 8(11), 537. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes8110537