From Co-Operation to Coercion in Fisheries Management: The Effects of Military Intervention on the Nile Perch Fishery on Lake Victoria in Uganda

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- ○

- How was the military intervention on Lake Victoria organized, and what rules were enforced?

- ○

- To examine how coercive rule enforcement has impacted the fishing effort and fish stocks of the Nile perch on Lake Victoria over time;

- ○

- To understand the fishery policy implications of these interventions.

2. The Challenge of Rule Compliance in African Inland Fisheries

3. Materials and Methods

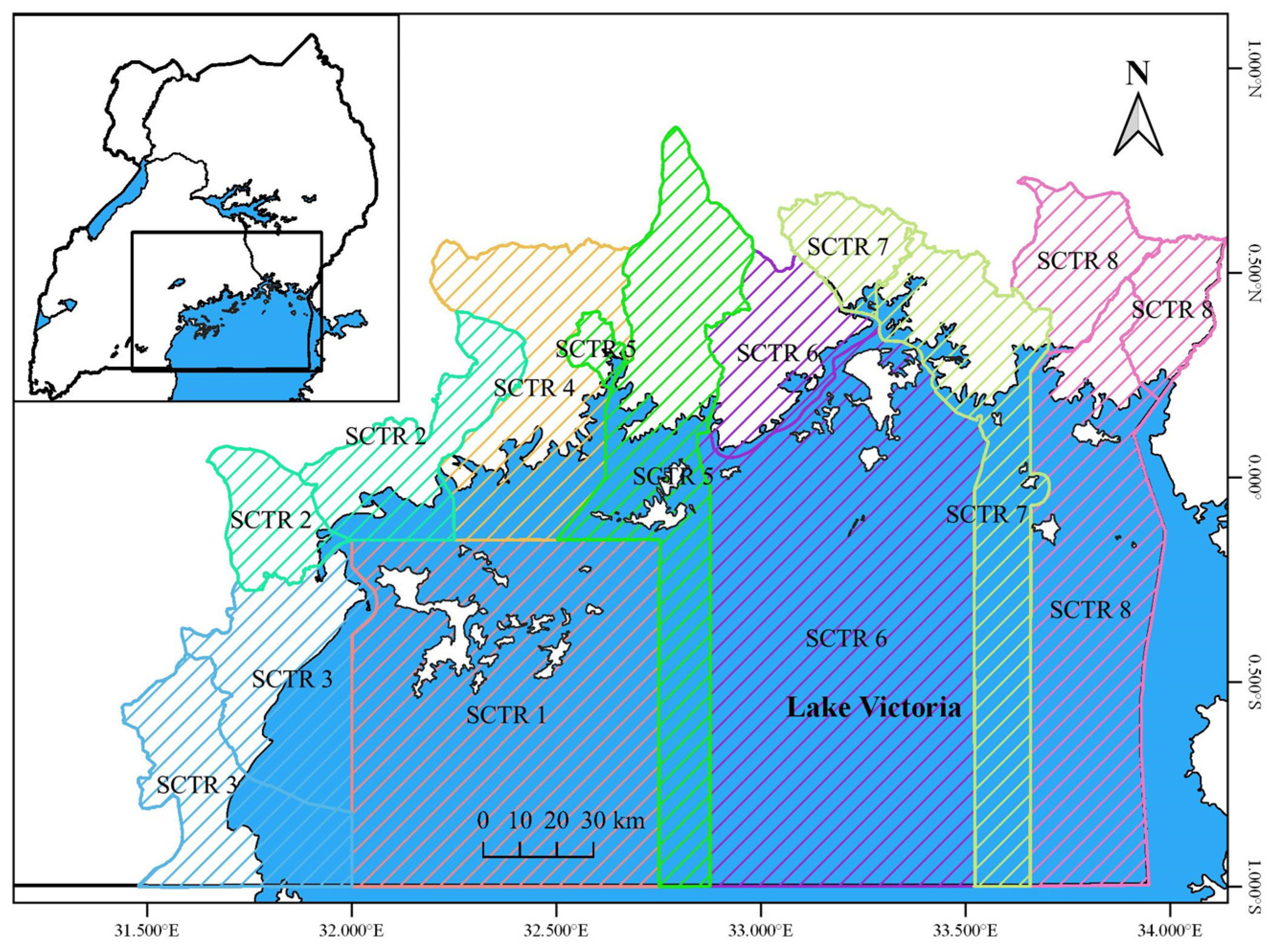

3.1. Study Area and Context

3.2. Data Sources

3.2.1. Data on the FPU Operation

3.2.2. Fishery Effort, Catch, and Export Data

3.3. Data Analysis

3.4. Limitations

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. The Military Operation on the Lake

4.2. Enforcement Activities of the FPU and the Effect on Fishing Effort

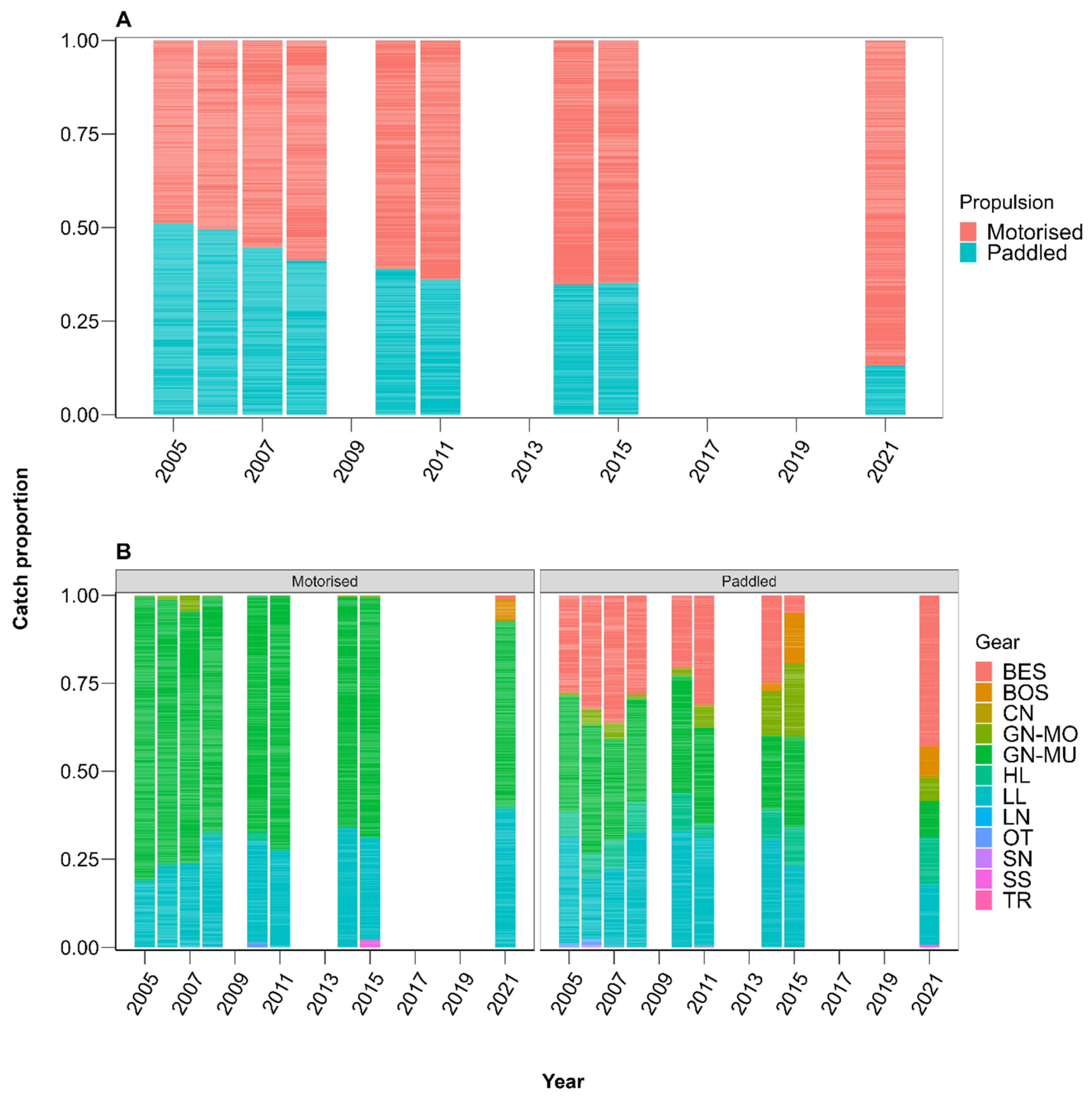

4.2.1. Effect on Fishing Effort

4.2.2. Confiscation of Illegal Gear and Vessels

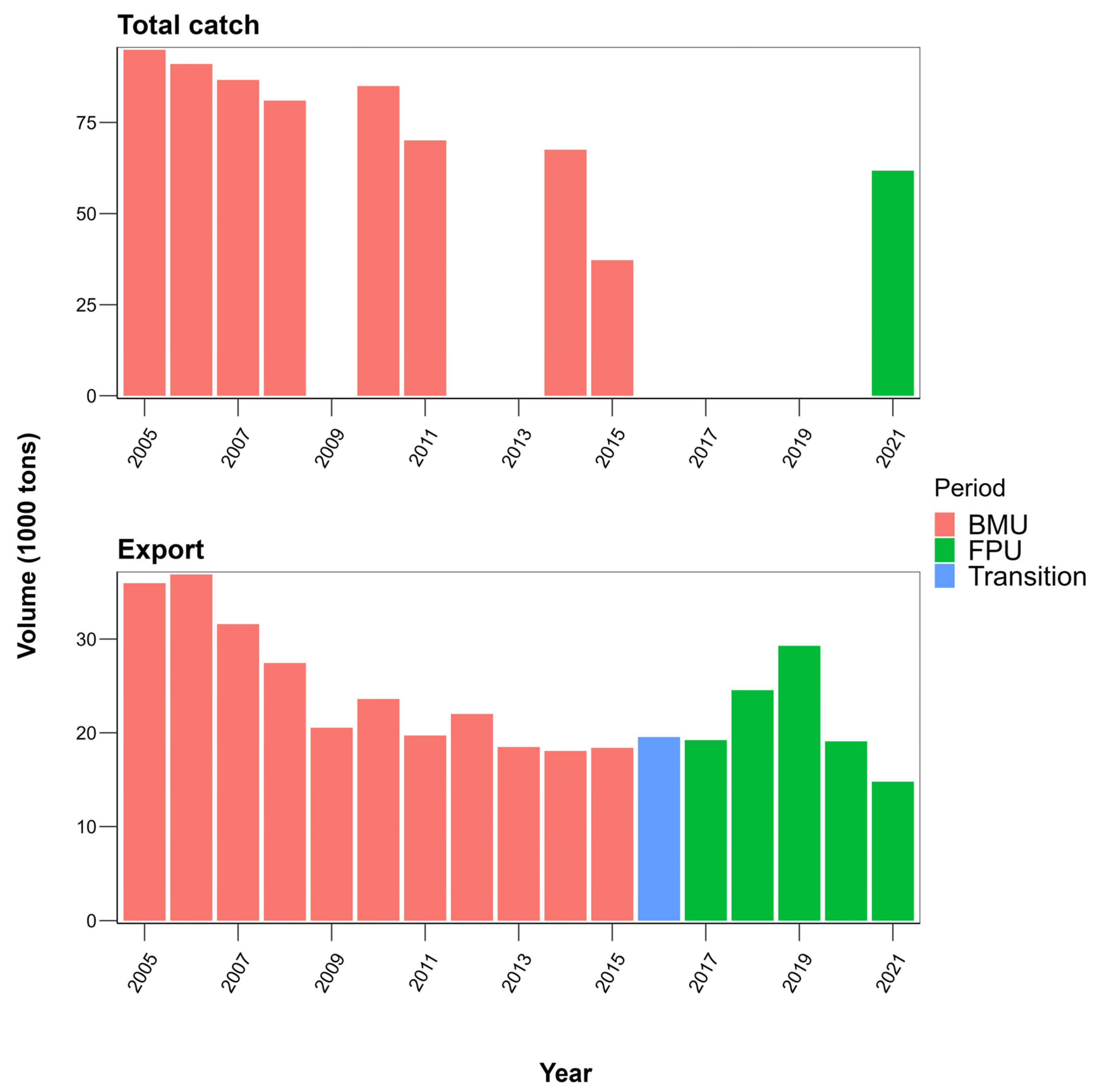

4.3. Changes in Catches during the BMU and FPU Management Regimes

Nile Perch CPUE

5. Conclusions and Implications for Policy

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Andrew, N.L.; Béné, C.; Hall, S.J.; Allison, E.H.; Heck, S.; Ratner, B.D. Diagnosis and management of small-scale fisheries in developing countries. Fish Fish. 2007, 8, 227–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, J.R.; Degnbol, P.; Viswanathan, K.K.; Ahmed, M.; Hara, M.; Abdullah, N.M.R. Fisheries co-management—An institutional innovation? Lessons from South East Asia and Southern Africa. Mar. Policy 2004, 28, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunan, F.; Hara, M.; Onyango, P. Institutions and Co-Management in East African Inland and Malawi Fisheries: A Critical Perspective. World Dev. 2015, 70, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Béné, C.; Belal, E.; Baba, M.O.; Ovie, S.; Raji, A.; Malasha, I.; Njaya, F.; Na Andi, M.; Russell, A.; Neiland, A. Power Struggle, Dispute and Alliance Over Local Resources: Analyzing ‘Democratic’ Decentralization of Natural Resources through the Lenses of Africa Inland Fisheries. World Dev. 2009, 37, 1935–1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, H.; Basurto, X. Defining Small-Scale Fisheries and Examining the Role of Science in Shaping Perceptions of Who and What Counts: A Systematic Review. Front. Mar. Sci. 2019, 6, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branch, G.M.; Hauck, M.; Siqwana-Ndulo, N.; Dye, A.H. Defining fishers in the South African context: Subsistence, artisanal and small-scale commercial sectors. Afr. J. Mar. Sci. 2002, 24, 475–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulgencio, K. Globalisation of the Nile perch: Assessing the socio-cultural implications of the Lake Victoria fishery in Uganda. Afr. J. Political Sci. Int. Relat. 2009, 3, 433–442. [Google Scholar]

- Beuving, J. Spatial diversity in small scale fishing: A socio-cultural interpretation of the Nile perch sector on Lake Victoria, Uganda. Tijdschr. Voor Econ. En. Soc. Geogr. 2015, 106, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, P.J.; Allison, E.H.; Andrew, N.L.; Cinner, J.; Evans, L.S.; Fabinyi, M.; Garces, L.R.; Hall, S.J.; Hicks, C.C.; Hughes, T.P.; et al. Securing a just space for small-scale fisheries in the blue economy. Front. Mar. Sci. 2019, 6, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrese, L.; Tang, X. Africa’s Economic Transformation: The Role of Chinese Investment. Available online: https://degrp.odi.org/publication/africas-economic-transformation-the-role-of-chinese-investment/ (accessed on 23 January 2022).

- Duffy, R.; Massé, F.; Smidt, E.; Marijnen, E.; Büscher, B.; Verweijen, J.; Ramutsindela, M.; Simlai, T.; Joanny, L.; Lunstrum, E. Why we must question the militarization of conservation. Biol. Conserv. 2018, 232, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massé, F.; Lunstrum, E.; Holterman, D. Linking green militarization and critical military studies. Crit. Mil. Stud. 2018, 4, 201–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mpomwenda, V.; Kristófersson, D.M.; Taabu-Munyaho, A.; Tómasson, T.; Pétursson, J.G. Fisheries management on Lake Victoria at a cross-roads: Assessing fishers’ perceptions on future management options in Uganda. Fish. Manag. Ecol. 2021, 2, 196–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunan, F.; Cepić, D.; Yongo, E.; Salehe, M.; Mbilingi, B.; Odongkara, K.; Onyango, P.; Mlahagwa, E.; Owili, M. Compliance, corruption and co-management: How corruption fuels illegalities and undermines the legitimacy of fisheries co-management. Int. J. Commons 2018, 12, 58–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantel, A.J. Fishing for Power: Incursions of the Ugandan Authoritarian State. Ann. Am. Assoc. Geogr. 2019, 109, 443–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunan, F. The political economy of fisheries co-management: Challenging the potential for success on Lake Victoria. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2020, 63, 102101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BOU. Composition of Exports. Available online: https://www.bou.or.ug/bouwebsite/PaymentSystems/dataandstat.html (accessed on 22 March 2022).

- Kjær, A.M. Political Settlements and Productive Sector Policies: Understanding Sector Differences in Uganda. World Dev. 2015, 68, 230–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjær, A.M.; Muhumuza, F.; Mwebaze, T.; Katusiimeh, M. The Political Economy of the Fisheries Sector in Uganda: Ruling Elites, Implementation Costs and Industry Interest; DIIS Working Paper: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2012; Available online: https://nru.uncst.go.ug/handle/123456789/7612 (accessed on 15 February 2023).

- Mkumbo, O.C.; Marshall, B.E. The Nile perch fishery of Lake Victoria: Current status and management challenges. Fish. Manag. Ecol. 2015, 22, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthur, R.I. Small-scale fisheries management and the problem of open access. Mar. Policy 2020, 115, 103867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funge-Smith, S. Review of the State of the World Fishery Resources: Inland; FAO (Fish and Aquaculture Organisation): Rome, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Voluntary Guidelines for Securing Sustainable Small-Scale Fisheries in the Context of Food Security and Poverty Eradication; FAO (Fisheries and Aquaculture Organization): Rome, Italy, 2015; p. 34. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- North, D.C.; Wallis, J.J. Integrating Institutional Change and Technical Change in Economic History A Transaction Cost Approach. J. Institutional Theor. Econ. (JITE)/Z. Die Gesamte Staatswiss 1994, 150, 609–624. [Google Scholar]

- Hanna, S.; Munasinghe, M. Property Rights and the Environment: Social and Ecological Issues; Beijer Institute of Ecological Economics and World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Dletz, T.; Ostrom, E.; Stern, P.C. The struggle to govern the commons. Science 2003, 302, 1907–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, R.J. An analytical framework for studying: Compliance and legitimacy in fisheries management. Mar. Policy 2003, 27, 425–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauck, M.; Kroese, M. Fisheries compliance in South Africa: A decade of challenges and reform 1994–2004. Mar Policy 2006, 30, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauck, M. Rethinking small-scale fisheries compliance. Mar. Policy 2008, 32, 635–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuenpagdee, R.; Jentoft, S. Exploring challenges in small-scale fisheries governance. In Interactive Governance for Small-Scale Fisheries: Global Reflections; Jentoft, S., Chuenpagdee, R., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; Volume 3, pp. 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Hardin, G. The tragedy of the commons. Science 1968, 162, 1243–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purcell, S.W.; Pomeroy, R.S. Driving small-scale fisheries in developing countries. Front. Mar. Sci. 2015, 2, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolding, J.; Van Zwieten, P.A.M. The Tragedy of Our Legacy: How do Global Management Discourses Affect Small Scale Fisheries in the South? Forum Dev. Stud. 2011, 38, 267–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jul-Larsen, E. Analysis of effort dynamics in the Zambian inshore fisheries of Lake Kariba. In Management, Co-Management or No Management ? Major Dilemmas in Southern African Freshwater Fisheries; Jul-Larsen, E., Kolding, J., Overå, R., Nielsen, R.J., van Zwieten, P.A.A.M., Eds.; Food & Agriculture Orgnization: Rome, Italy, 2003; p. 271. [Google Scholar]

- Ogutu-Ohwayo, R.; Wandera, S.B.; Kamanyi, I.R. Fishing gear selectivity for Lates niloticus L., Oreochromis niloticus L. and Rastrineobola argentea P. in Lakes Victoria, Kyoga and Nabugabo. Conserv. Biol. 1998, 7, 33–38. [Google Scholar]

- Malasha, I. Colonial and postcolonial fisheries regulations: The cases of Zambia and Zimbabwe. In Management, Co-Management, or No Management? Major Dilemmas in Southern African Freshwater Fisheries; Fisheries Technical paper 2; Jul-Larsen, E., Kolding, J., Overå, R., Nielsen, R.J., van Zwieten, P.A.M., Eds.; Food & Agriculture Orgnization: Rome, Italy, 2003; pp. 253–266. [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal, A. Common property institutions and sustainable governance of resources. World Dev. 2001, 29, 1649–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cepić, D.; Nunan, F. Justifying non-compliance: The morality of illegalities in small scale-fisheries of Lake Victoria, East Africa. Mar. Policy 2017, 86, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hoof, L. Co-management: An alternative to enforcement? ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2010, 67, 395–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunan, F. Wealth and welfare? Can fisheries management succeed in achieving multiple objectives? A case study of Lake Victoria, East Africa. Fish Fish. 2014, 15, 134–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, T.J.; Watkins, C. It takes more than a village: The challenges of co-management in Uganda’s fishery and forestry sectors. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2012, 19, 144–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjöstedt, M.; Linell, A. Cooperation and coercion: The quest for quasi-voluntary compliance in the governance of African commons. World Dev. 2021, 139, 105333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mafuta, C.; Levi, W.; Lake Victoria Basin Commission. Lake Victoria Basin: Atlas of our Changing Environment; GRID-Arendal: Arendal, Norway, 2017; Available online: https://policycommons.net/artifacts/2390339/lake-victoria-basin/3411606/ (accessed on 17 July 2023).

- Bagumire, A.; Muyanja, C.K.; Kiboneka, F.W. Report for The Value Chain Analysis of Nile Perch Maw Trade in East Africa. In The Responsible Fisheries Business Chains Project of Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) under Contract, 83285575; LVFO (Lake Victoria Fisheries Organisation): Jinja, Uganda, 2018; pp. 1–52. Available online: www.foodsafetyltd.com (accessed on 6 March 2023).

- Creswell, J.W. Research Design; Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Methods Approaches, 3rd ed; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Newing, H.; Eagle, C.M.; Puri, R.K.; Watson, C.W. Conducting Research in Conservation Social Science: A Social Science Perspective, 1st ed.; Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Léopold, M.; Guillemot, N.; Rocklin, D.; Chen, C. A framework for mapping small-scale coastal fisheries using fishers’ knowledge. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2014, 71, 1781–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samy-Kamal, M.; Teixeira, C.M. Diagnosis and Management of Small-Scale and Data-Limited Fisheries. Fishes 2023, 8, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LVFO. The Standard Operating Procedures for Catch Assessment Surveys; LVFO (Lake Victoria Fisheries Organisation): Jinja, Uganda, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- LVFO. Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) for Catch Assessment Surveys on Lake Victoria; LVFO Standard Operating Procedures: Jinja, Uganda, 2007; No. 3. [Google Scholar]

- UBOS. 2022 Uganda Statistical Abstract; UBOS (Uganda Bureau of Statistics): Kampala, Uganda, 2022; Available online: https://www.ubos.org (accessed on 21 March 2023).

- RStudio Team. RStudio: Integrated Development Environment for R. Rstudio; PBC: Boston, MA, USA, 2020; Available online: http://www.rstudio.com/ (accessed on 19 May 2021).

- Wickham, H.; Wickham, H. Data Analysis; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Njiru, M.; Getabu, A.; Taabu, A.M.; Mlaponi, E.; Muhoozi, L.; Mkumbo, O.C. Managing Nile perch using slot size: Is it possible? Afr. J. Trop. Hydrobiol. Fish. 2010, 12, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mpomwenda, V.; Tomasson, T.; Pétursson, J.G.; Taabu-munyaho, A.; Nakiyende, H.; Kristófersson, D.M. Adaptation Strategies to a Changing Resource Base: Case of the Gillnet Nile Perch Fishery on Lake Victoria in Uganda. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayanda, R.; Taabu, A.; Tumwebaze, R.; Muhoozi, L.; Jembe, T.; Mlaponi, E.; Nzungi, P. Status of the Major Commercial Fish Stocks and Proposed Species-specific Management Plans for Lake Victoria. Afr. J. Hydrobiol. Fish. 2008, 12, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyamweya, C.S.; Natugonza, V.; Kashindye, B.B.; Mangeni-Sande, R.; Kagoya, E.; Mpomwenda, V.; Mziri, V.; Elison, M.; Mlaponi, E.; Ongore, C.; et al. Response of fish stocks in Lake Victoria to enforcement of the ban on illegal fishing: Are there lessons for management? J. Great Lakes Res. 2023, 49, 531–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njiru, M.; Van der Knaap, M.; Taabu-Munyaho, A.; Nyamweya, C.S.; Kayanda, R.J.; Marshall, B.E. Management of Lake Victoria fishery: Are we looking for easy solutions ? Aquat. Ecosyst. Health Manag. 2014, 17, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UFPEA. Uganda Fish Processors and Exporters Association: E-Newsletter; UFPEA; no. August; Uganda Fish Processors and Exporters Association: Kampala, Uganda, 2019; p. 17. Available online: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1l44CVnOs03hnIF8eIeFgtv0ijjdpbuCV/view (accessed on 6 July 2023).

- Diyamett, L.D.; Mbilingi, B.; Mutambala, M. COVID-19 Pandemic in Developing Economies: Lockdown versus No Lockdown Scenarios for the Fisheries; Southern Voice: Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Msuku, B.S.; Mrosso, H.D.J.; Nsinda, P.E. A critical look at the current gillnet regulations meant to protect the Nile Perch stocks in Lake Victoria. Aquat. Ecosyst. Health Manag. 2011, 14, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mkumbo, O.C.; Mlaponi, E. Impact of the baited hook fishery on the recovering endemic fish species in Lake Victoria. Aquat. Ecosyst. Health Manag. 2007, 10, 458–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Hasan, A.; de Mitcheson, Y.S.; Cisneros-Mata, M.A.; Jimenez, A.; Daliri, M.; Cisneros-Montemayor, A.M.; Nair, R.J.; Thankappan, S.A.; Walters, C.J.; Christensen, V. China’s fish maw demand and its implications for fisheries in source countries. Mar. Policy 2021, 132, 104696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Mitcheson, Y.S.; To, A.W.L.; Wong, N.W.; Kwan, H.Y.; Bud, W.S. Emerging from the murk: Threats, challenges and opportunities for the global swim bladder trade. Rev. Fish. Biol. Fish. 2019, 29, 809–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LVFO. A Report of the Lake-Wide Hydroacoustic Survey on Lake Victoria 15th September–13th October 2019; LVFO (Lake Victoria Fisheries Organisation): Jinja, Uganda, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Natugonza, V.; Nyamweya, C.; Sturludóttir, E.; Musinguzi, L.; Ogutu-Ohwayo, R.; Bassa, S.; Mlaponi, E.; Tomasson, T.; Stefansson, G. Spatiotemporal variation in fishing patterns and fishing pressure in Lake Victoria (East Africa) in relation to balanced harvest. Fish. Res. 2022, 252, 106355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downing, A.S.; van Nes, E.H.; Balirwa, J.S.; Beuving, J.; Bwathondi, P.; Chapman, L.J.; Cornelissen, I.J.M.; Cowx, I.G.; Goudswaard, K.P.C.; Hecky, R.E.; et al. Coupled human and natural system dynamics as key to the sustainability of Lake Victoria’s Ecosystem services. Ecol. Soc. 2014, 19, 31–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyamweya, C.S.; Natugonza, V.; Taabu-Munyaho, A.; Aura, C.M.; Njiru, J.M.; Ongore, C.; Mangeni-Sande, R.; Kashindye, B.B.; Odoli, C.O.; Ogari, Z.; et al. A century of drastic change: Human-induced changes of Lake Victoria fisheries and ecology. Fish. Res. 2020, 230, 105564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aura, C.M.; Musa, S.; Yongo, E.; Okechi, J.K.; Njiru, J.M.; Ogari, Z.; Wanyama, R.; Charo-Karisa, H.; Mbugua, H.; Kidera, S.; et al. Integration of mapping and socio-economic status of cage culture: Towards balancing lake-use and culture fisheries in Lake Victoria, Kenya. Aquac. Res. 2018, 49, 532–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Legislation | Rules |

|---|---|

| Fish Act Cap 197 of 2000 The fish (fishing) rules of 2010 |

|

| Management Regime | Pre-BMU | BMU | Transition Period | Military Enforcement | Average Yearly Change | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | 2000 | 2002 | 2004 | 2006 | 2008 | 2010 | 2012 | 2014 | 2016 | 2020 | 2002–2004 | 2014–2016 | 2016–2020 | 2000–2020 |

| Landing sites | 597 | 552 | 554 | 481 | 435 | 503 | 555 | 567 | 556 | 446 | 0% | −1% | −6% | −1% |

| Fishers | 34,889 | 41,674 | 37,721 | 54,148 | 51,916 | 56,957 | 63,921 | 64,617 | 66,869 | 60,552 | −5% | 2% | −2% | 3% |

| Motorised vessels | 2031 | 3250 | 3173 | 5047 | 5156 | 6334 | 9351 | 9955 | 11,495 | 17,075 | −1% | 7% | 10% | 11% |

| Paddled vessels | 12,848 | 14,262 | 12,506 | 17,475 | 15,602 | 16,389 | 17,111 | 17,260 | 17,260 | 8460 | −7% | 0% | −18% | −2% |

| Sailed vessels | 665 | 1074 | 1096 | 1466 | 1078 | 682 | 1125 | 857 | 864 | 260 | 1% | 0% | −30% | −5% |

| Towed vessels | 17 | 51 | 28 | 18 | −30% | −11% | 1% | |||||||

| Foot fishers | 50 | 367 | 100 | 463 | 350 | 77% | −7% | 19% | ||||||

| Legal gears | ||||||||||||||

| Multifilament gillnets ≥ 5″ | 243,209 | 374,642 | 402,351 | 498,037 | 327,098 | 307,052 | 423,155 | 384,849 | 355,348 | 556,767 | 4% | −4% | 11% | 4% |

| Hand line hooks 1 | 4585 | 6547 | 8335 | 15,860 | 19,629 | 17,071 | 27,780 | 27,004 | 37,785 | 20,669 | 12% | 17% | −15% | 8% |

| Longline hooks < 10 | 1,681,048 | 1,657,458 | 1,389,548 | 1,525,810 | 850,493 | 479,767 | 3,178,446 | −29% | 47% | 5% | ||||

| Illegal gears | ||||||||||||||

| Multifilament gillnets < 5″ | 54,454 | 52,846 | 56,246 | 91,740 | 76,908 | 66,532 | 59,585 | 78,571 | 79,473 | 8676 | 3% | 1% | −55% | −9% |

| Beach/boat seine | 811 | 880 | 954 | 1425 | 1649 | 1451 | 1233 | 1819 | 1968 | 1093 | 4% | 4% | −15% | 1% |

| Cast net | 1276 | 858 | 659 | 631 | 1000 | 1095 | 1372 | 1359 | 1342 | 873 | −13% | −1% | −11% | −2% |

| Monofilament gillnets | 845 | 11,203 | 12,115 | 15,148 | 21,793 | 31,876 | 15,204 | 19% | −19% | 18% | ||||

| Basket traps | 11,349 | 5781 | 5361 | 499 | 7615 | 10,331 | 7082 | 9000 | 6144 | 3341 | −4% | −19% | −15% | −6% |

| Longline hooks ≥ 10 | 604,561 | 1,106,341 | 1,169,807 | 2,892,575 | 3,737,273 | 3,998,352 | 1,057,646 | 3% | −33% | 4% | ||||

| Effort Variable | Year | February 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | August 2020 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fishing vessels | Parachute (≤6 m) | 6136 | 3622 | 7154 | 5434 | 22,346 |

| Ssesse vessels (6–12 m) | 924 | 2374 | 649 | 649 | 4596 | |

| Unspecified | 318 | 555 | 65 | 938 | ||

| Total of vessels | 7060 | 6314 | 8358 | 6148 | 27,880 | |

| Fishing gears | Hooks size > 10 | 1,123,863 | 2,413,174 | 3,400,299 | 775,111 | 7,712,447 |

| Multifilament gillnets < 5″ | 22,400 | 15,322 | 44,630 | 2500 | 84,852 | |

| Monofilament gillnets | 147,331 | 244,949 | 99,992 | 47,391 | 539,663 | |

| Basket traps | 290 | 631 | 474 | 538 | 1933 | |

| Beach/boat seines | 2014 | 2377 | 1862 | 1185 | 7438 | |

| Cast nets | 1278 | 967 | 324 | 382 | 2951 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mpomwenda, V.; Tómasson, T.; Pétursson, J.G.; Kristófersson, D.M. From Co-Operation to Coercion in Fisheries Management: The Effects of Military Intervention on the Nile Perch Fishery on Lake Victoria in Uganda. Fishes 2023, 8, 563. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes8110563

Mpomwenda V, Tómasson T, Pétursson JG, Kristófersson DM. From Co-Operation to Coercion in Fisheries Management: The Effects of Military Intervention on the Nile Perch Fishery on Lake Victoria in Uganda. Fishes. 2023; 8(11):563. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes8110563

Chicago/Turabian StyleMpomwenda, Veronica, Tumi Tómasson, Jón Geir Pétursson, and Daði Mar Kristófersson. 2023. "From Co-Operation to Coercion in Fisheries Management: The Effects of Military Intervention on the Nile Perch Fishery on Lake Victoria in Uganda" Fishes 8, no. 11: 563. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes8110563

APA StyleMpomwenda, V., Tómasson, T., Pétursson, J. G., & Kristófersson, D. M. (2023). From Co-Operation to Coercion in Fisheries Management: The Effects of Military Intervention on the Nile Perch Fishery on Lake Victoria in Uganda. Fishes, 8(11), 563. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes8110563