FishSegNet-PRL: A Lightweight Model for High-Precision Fish Instance Segmentation and Feeding Intensity Quantification

Abstract

1. Introduction

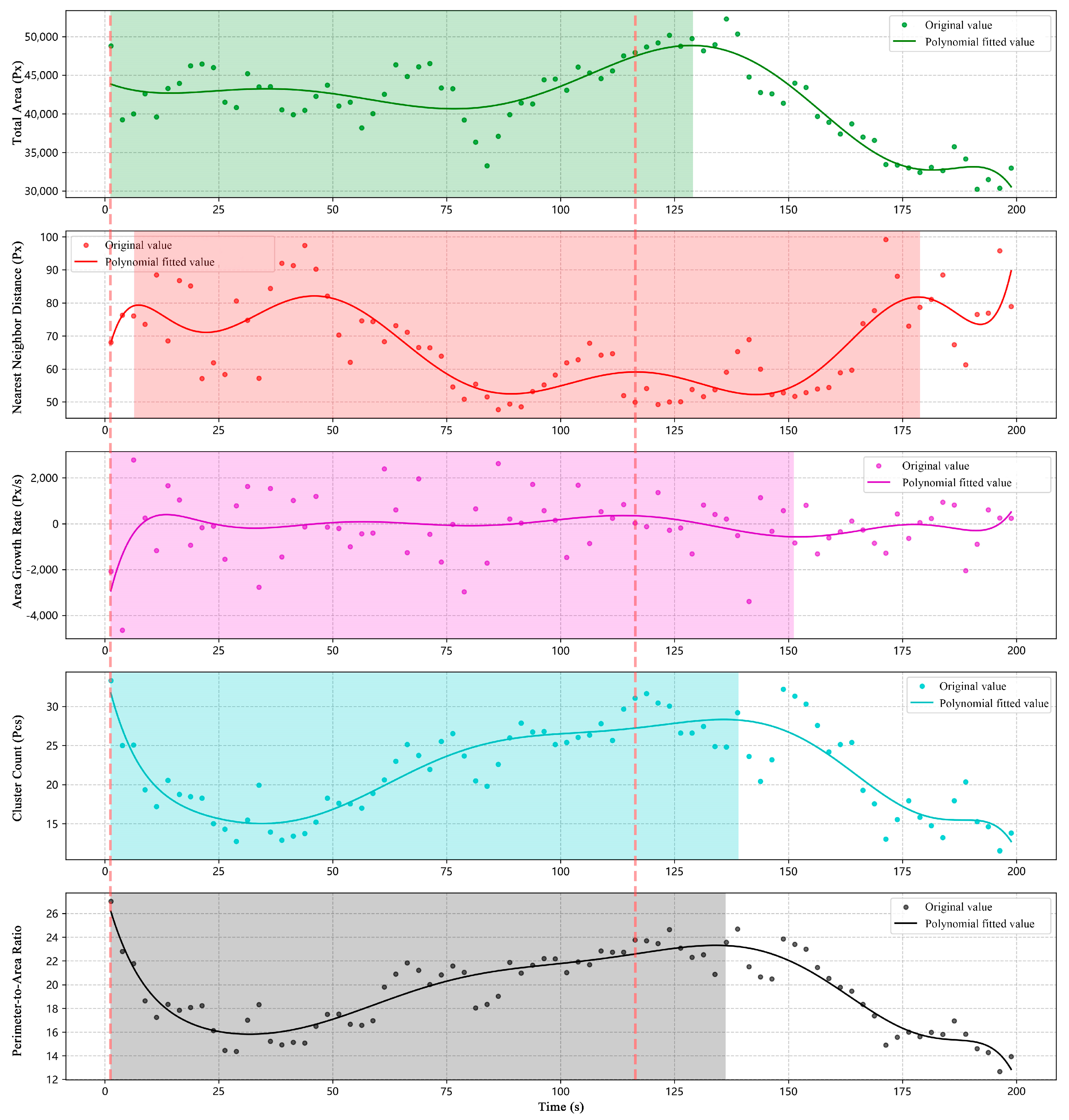

- We propose the FishSegNet-PRL instance segmentation method, which is capable of extracting multiple key feature indices—including total area, nearest-neighbor distance, area growth rate, cluster number, and perimeter-to-area ratio—to comprehensively characterize the spatial structural behavior of fish schools.

- We construct a fish instance segmentation dataset covering diverse feeding image conditions (e.g., occlusion, overlap, and aggregation), which is used to train and evaluate models for extracting spatial structural behavioral features.

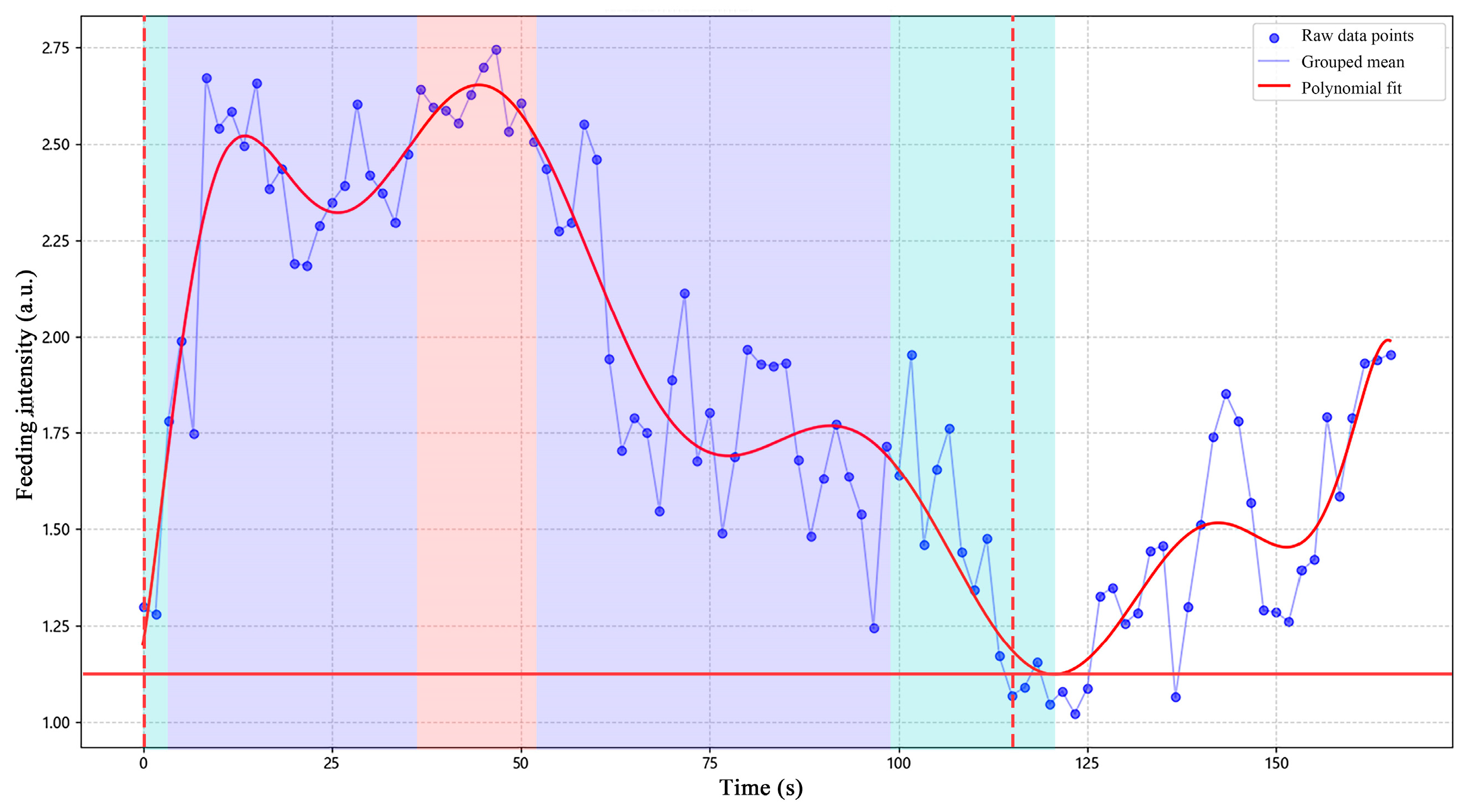

- We experimentally validate the effectiveness of FishSegNet-PRL on video datasets annotated with four feeding intensity levels (none, weak, moderate, strong). Using the spatial behavioral features extracted by FishSegNet-PRL as inputs, the LightGBM model enables fine-grained classification and continuous prediction of feeding intensity, thereby achieving quantitative representation of feeding dynamics.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Acquisition and Dataset Split

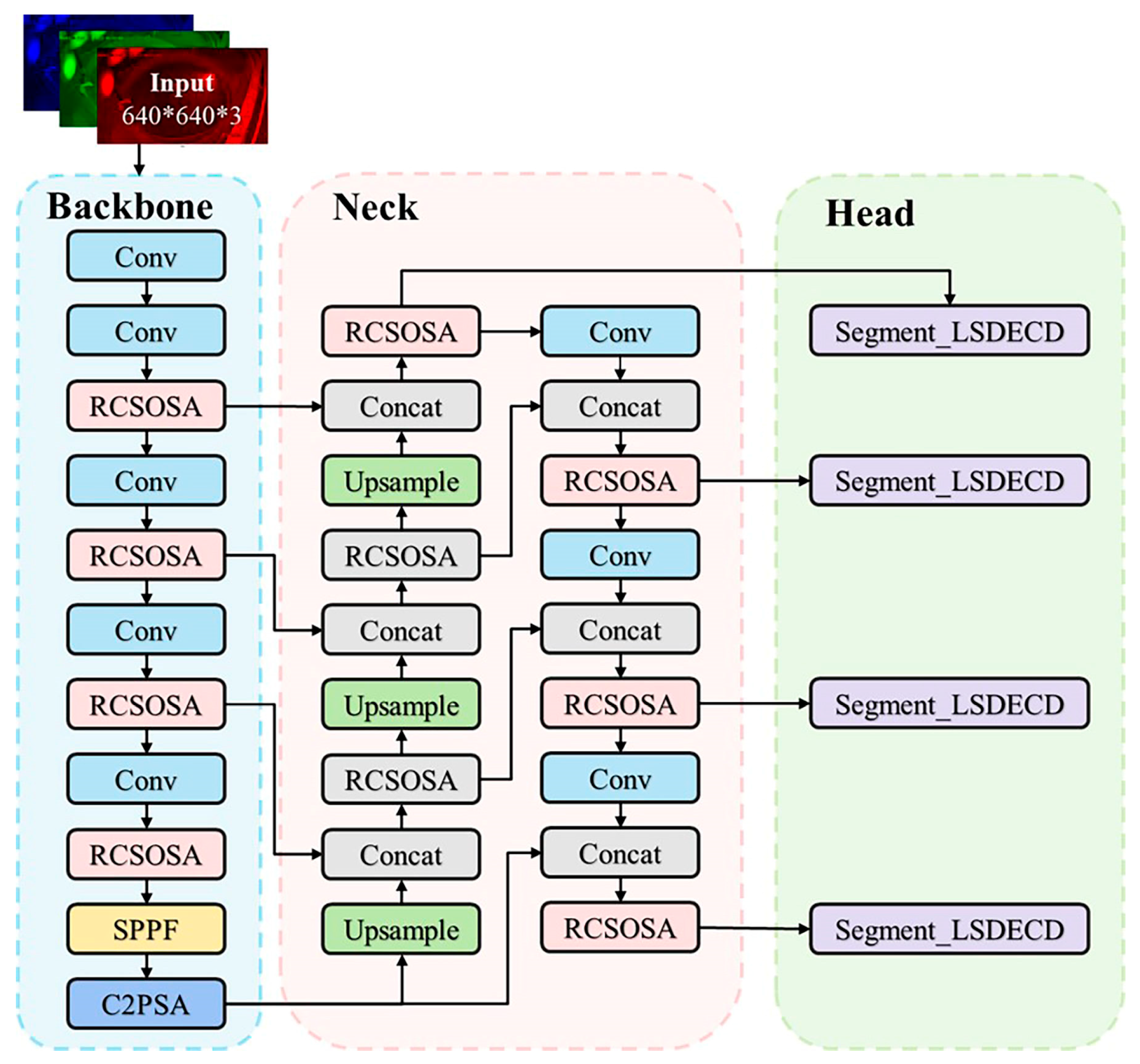

2.2. Instance Segmentation Model: FishSegNet-PRL

2.2.1. Overall Architecture of the FishSegNet-PRL Model

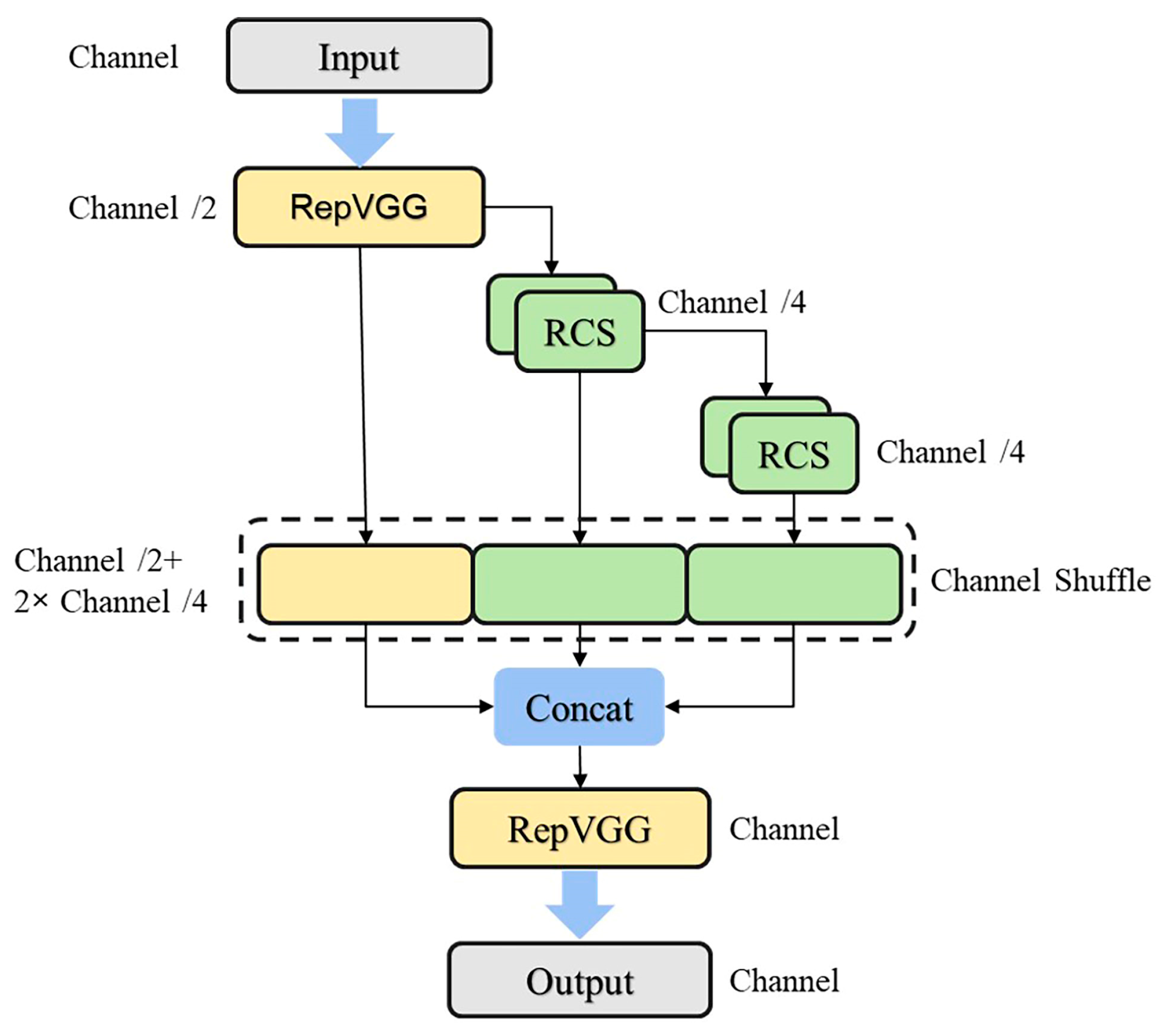

2.2.2. RCSOSA Module

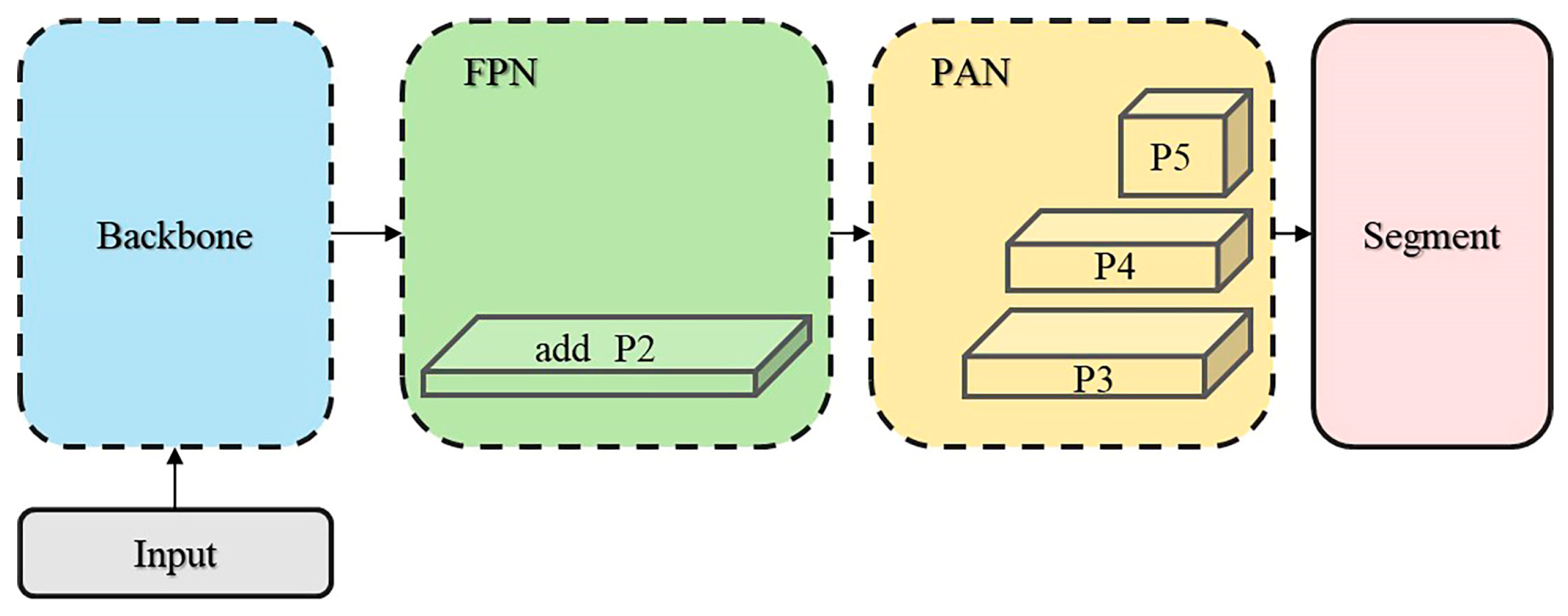

2.2.3. P2 Detection Head

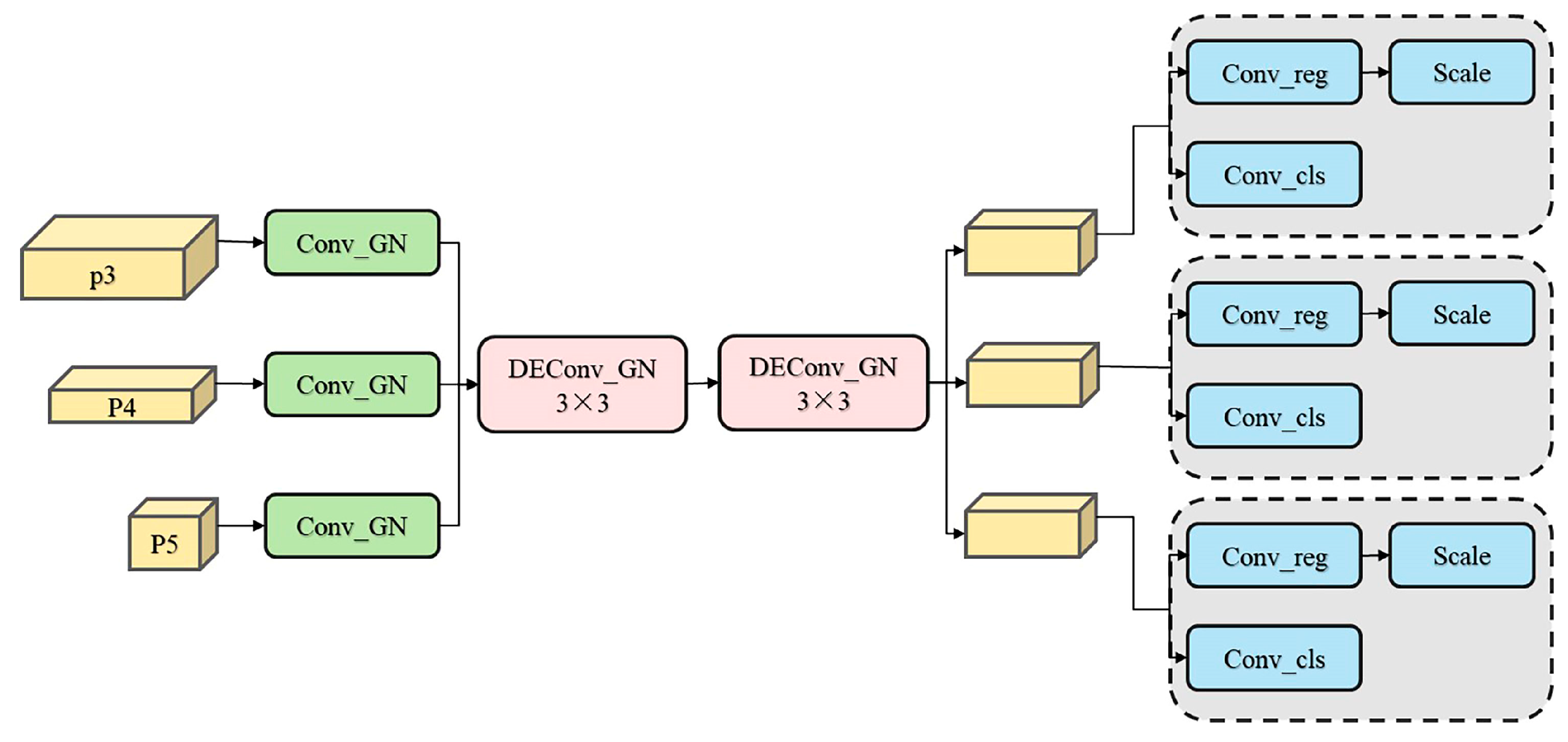

2.2.4. LSDECD

2.3. Feature Construction for Feeding-Intensity

2.4. Feeding-Intensity Modeling with LightGBM

2.5. Evaluation Metrics

2.5.1. Evaluation Metrics for FishSegNet-PRL

Precision (P) and Recall (R)

P–R Curve and mAP

Intersection over Union (IoU) and mIoU

Frames per Second (FPS)

2.5.2. Evaluation Metrics for the LightGBM Model

2.5.3. Quantification of Fish School Features and Feeding Intensity Indicators

3. Results

3.1. Experimental Environment

3.2. Instance Segmentation on PRLSFISH

3.3. Ablation Study

3.4. Comparative Study

3.5. Feeding-Feature Dynamics & Phase Consistency

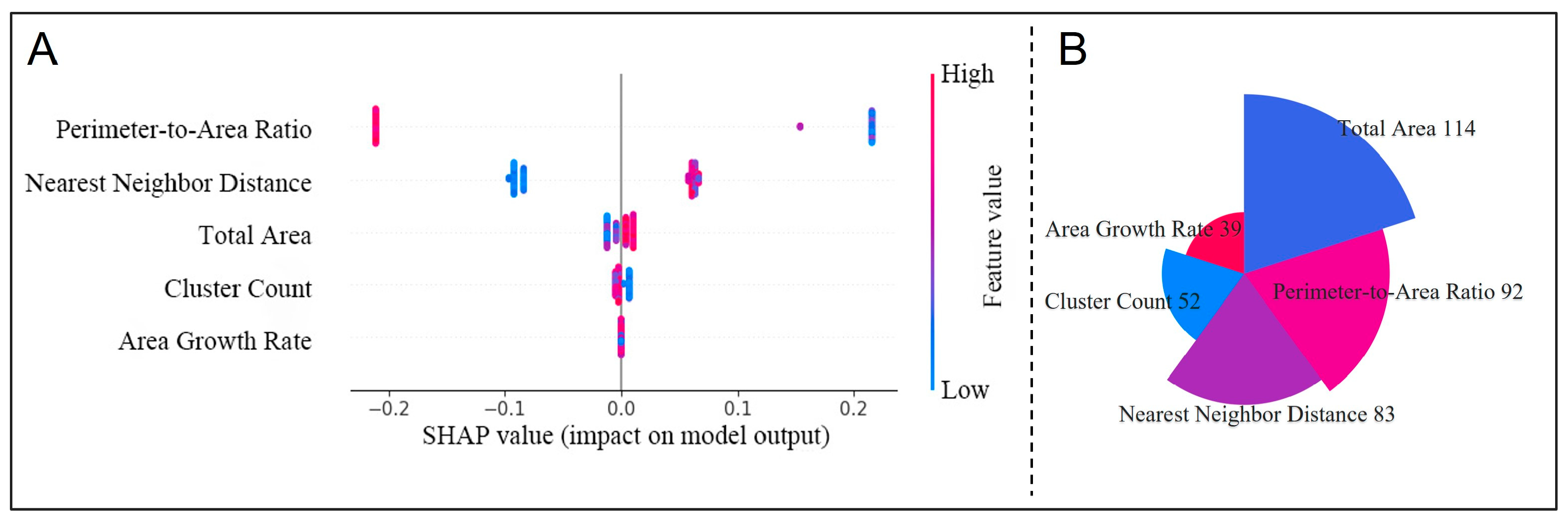

3.6. Feature Importance & Elimination

3.7. Feeding-Intensity Curve & Stage Detection

4. Discussion

4.1. Effectiveness of Architectural Modifications

4.2. Scene Adaptability and Cross-Dataset Performance

4.3. Behavioral Rationale for Feeding-Intensity Modeling

4.4. Interpretable Modeling and Feature Selection

4.5. Engineering Deployability and the Data Ecosystem

4.6. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Han, X.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Y.; Fang, H.; Peng, S.; Yang, S.; Wu, Z. Seedling selection of the large yellow croaker (Larimichthys crocea) for sustainable aquaculture: A review. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 7307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Fao Report: Global Fisheries and Aquaculture Production Reaches a New Record High; FAO Newsroom: Rome, Italy, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Ding, L.; Huang, J.; Zhou, Z.; Chen, W. Farmed chinese perch (Siniperca chuatsi) coinfected with parasites and oomycete pathogens. Fishes 2024, 9, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Cai, K.; Dong, Y.; Feng, G.; Wang, Y.; Pang, H.; Liu, Y. Fish feeding behavior recognition via lightweight two stage network and satiety experiments. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 30025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Li, X.; Fan, L.; Lu, H.; Liu, L.; Liu, Y. Measuring feeding activity of fish in ras using computer vision. Aquac. Eng. 2014, 60, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Li, Z.; Zhang, S. Reviews on the application of automatic feeding technology in aquaculture. Fish. Inf. Strategy 2025, 40, 98–109. [Google Scholar]

- Musalia, L.M.; Jonathan, M.M.; Liti, D.M.; Kyule, D.N.; Ogello, E.O.; Obiero, K.O.; Kirimi, J.G. Aqua-feed wastes: Impact on natural systems and practical mitigations—A review. Agric. Sci. 2020, 13, 111. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, A.-Q.; Li, K.-L.; Song, Z.-Y.; Lou, X.; Hu, P.; Yang, W.; Wang, R.-F. Deep learning for sustainable aquaculture: Opportunities and challenges. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Huang, L.; Zhang, S.; Bi, C.; You, X.; He, S.; Guan, J. Feeding behavior quantification and recognition for intelligent fish farming application: A review. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2025, 285, 106588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.x.; Cui, H.w.; Qu, K.; Zhu, J.; Li, H.; Cui, Z.; Wu, Y. A fish appetite assessment method based on improved bytetrack and spatiotemporal graph convolutional network. Biosyst. Eng. 2024, 240, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Yu, X.; An, D.; Ning, X.; Liu, J.; Tiwari, P. Uniformity and deformation: A benchmark for multi-fish real-time tracking in the farming. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 264, 125653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, H.; Qian, C.; Liu, S. An improved deepsort-based model for multi-target tracking of underwater fish. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Wu, J.; Liu, L.; Qu, B.; Yin, J.; Yu, H.; Jiang, Z.; Zhou, C. A real-time feeding decision method based on density estimation of farmed fish. Front. Mar. Sci. 2024, 11, 1358209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Chen, Y.; Shen, T.; Li, D. An fsfs-net method for occluded and aggregated fish segmentation from fish school feeding images. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 6235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herong, W.; Yingyi, C.; Yingqian, C.; Ling, X.; Huihui, Y. Image segmentation method combined with vovnetv2 and shuffle attention mechanism for fish feeding in aquaculture. Smart Agric. 2023, 5, 137. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L.; Chen, Y.; Shen, T.; Yu, H.; Li, D. A blendmask-vovnetv2 method for quantifying fish school feeding behavior in industrial aquaculture. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 211, 108005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, H.; Wu, J.; Liang, X.; Xie, Y.; Qu, B.; Yu, H. Conceptual validation of high-precision fish feeding behavior recognition using semantic segmentation and real-time temporal variance analysis for aquaculture. Biomimetics 2024, 9, 730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ubina, N.; Cheng, S.-C.; Chang, C.-C.; Chen, H.-Y. Evaluating fish feeding intensity in aquaculture with convolutional neural networks. Aquac. Eng. 2021, 94, 102178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Yang, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, J.; Yan, Y.; Zhou, C. Fish feeding intensity quantification using machine vision and a lightweight 3d resnet-glore network. Aquac. Eng. 2022, 98, 102244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, J.; Li, B.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Duan, Q. A mobilenetv2-senet-based method for identifying fish school feeding behavior. Aquac. Eng. 2022, 99, 102288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wang, X.; Shi, Y.; Wang, Y.; Qian, D.; Jiang, Y. Fish feeding intensity assessment method using deep learning-based analysis of feeding splashes. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 221, 108995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, D.; Ji, B.; Li, H.; Zhu, S.; Ye, Z.; Zhao, J. Modified kinetic energy feature-based graph convolutional network for fish appetite grading using time-limited data in aquaculture. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 1021688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Zhao, S.; Wang, Y.; Cai, K.; Pang, H.; Liu, Y. An integrated three-stream network model for discriminating fish feeding intensity using multi-feature analysis and deep learning. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0310356. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Wei, Y.; Ma, W.; Wang, T. Cross-modal complementarity learning for fish feeding intensity recognition via audio–visual fusion. Animals 2025, 15, 2245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, X. Research on Fish Object Detection and Image Segmentationin Aquaculture Environment. Ph.D. Thesis, Shanghai Ocean University, Shanghai, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Z. Abnormal behavior fish and population detection method based on deep learning. Front. Comput. Intell. Syst. 2023, 4, 44–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Zhang, D. Comparative analysis of traditional and deep learning approaches for underwater remote sensing image enhancement: A quantitative study. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, M.; Paeng, Y.; Lee, S. Color information-based automated mask generation for detecting underwater atypical glare areas. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.16538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Bai, X.; Feng, F.; Liu, X.; Meng, H.; Cui, X.; Yang, X.; Li, X. Adaptive polarizing suppression of sea surface glare based on the geographic polarization suppression model. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 4171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Deng, L.; Hu, C.; Xie, T.; Wang, C. Dense small object detection based on an improved yolov7 model. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 7665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.; Ting, C.-M.; Ting, F.F.; Phan, R.C.-W. Rcs-yolo: A fast and high-accuracy object detector for brain tumor detection. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 8–12 October 2023; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 600–610. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, X. Dangerous driving behavior detection algorithm based on faster-yolo11. Inf. Technol. Informatiz. 2025, 3, 175–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Lu, S.; Yan, Z.; Sha, C. Yolov8s-ewd:A model for ethernet cable wiring defect detection for radar. Mod. Radar 2025, 1–12. Available online: https://link.cnki.net/urlid/32.1353.TN.20250901.1528.002 (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Wang, Q.; Liu, F.; Cao, Y.; Ullah, F.; Zhou, M. Lfir-yolo: Lightweight model for infrared vehicle and pedestrian detection. Sensors 2024, 24, 6609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florek, P.; Zagdański, A. Benchmarking state-of-the-art gradient boosting algorithms for classification. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2305.17094. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L.; Zhou, W.; Zhang, C.; Tang, F. A comparative machine learning study identifies light gradient boosting machine (lightgbm) as the optimal model for unveiling the environmental drivers of yellowfin tuna (Thunnus albacares) distribution using shapley additive explanations (shap) analysis. Biology 2025, 14, 1567. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, J.; Li, Z.; Pinker, R.T.; Wang, J.; Sun, L.; Xue, W.; Li, R.; Cribb, M. Himawari-8-derived diurnal variations in ground-level pm 2.5 pollution across china using the fast space-time light gradient boosting machine (lightgbm). Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2021, 21, 7863–7880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; He, J.; Song, X. Fish feeding behavior recognition and quantification based on body motion and image texture features. Period. Ocean. Univ. China 2022, 52, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, S.; Ding, J. Segmentation of underwater fish in complex aquaculture environments using enhanced soft attention mechanism. Environ. Model. Softw. 2024, 181, 106170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Cao, L.; Xu, X.; Xu, J. Underwater instance segmentation: A method based on channel spatial cross-cooperative attention mechanism and feature prior fusion. Front. Mar. Sci. 2025, 12, 1557965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, W.; Seet, B.C. A lightweight underwater fish image semantic segmentation model based on u-net. IET Image Process. 2024, 18, 3143–3155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Zheng, B.; Kong, X.; Huang, J.; Wang, X.; Ding, T.; Chen, J. Underwater fish segmentation algorithm based on improved pspnet network. Sensors 2023, 23, 8072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Olmeda, J.F.; Sánchez-Vázquez, F.J. Feeding rhythms in fish: From behavioral to molecular approach. Biol. Clock Fish 2010, 8, 155–183. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, K.; Yang, Z.; Gao, T.; Liang, M.; Liu, P.; Zhou, S.; Pang, H.; Liu, Y. Efficient recognition of fish feeding behavior: A novel two-stage framework pioneering intelligent aquaculture strategies. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 224, 109129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Assis Hattori, J.F.; Piovesan, M.R.; Alves, D.R.S.; de Oliveira, S.R.; Gomes, R.L.M.; Bittencourt, F.; Boscolo, W.R. Mathematical modeling applied to fish feeding behavior. Aquac. Int. 2024, 32, 767–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Qiao, J.; Yu, G.; Wang, L.; Li, H.-Y.; Liao, C.; Zhu, Z. Interpretable tree-based ensemble model for predicting beach water quality. Water Res. 2022, 211, 118078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, P.; Tansey, K.; Liu, J.; Delaney, B.; Quan, W. An interpretable approach combining shapley additive explanations and lightgbm based on data augmentation for improving wheat yield estimates. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 229, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Du, Z.; Xu, X.; Bai, Z.; Han, J.; Cui, M.; Li, D. A review of aquaculture: From single modality analysis to multimodality fusion. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 226, 109367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Z.; Cui, M.; Xu, X.; Bai, Z.; Han, J.; Li, W.; Yang, J.; Liu, X.; Wang, C.; Li, D. Harnessing multimodal data fusion to advance accurate identification of fish feeding intensity. Biosyst. Eng. 2024, 246, 135–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.; Zhao, S.; Duan, Y.; Meng, Y.; Li, D.; Zhao, R. Mmfinet: A multimodal fusion network for accurate fish feeding intensity assessment in recirculating aquaculture systems. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 232, 110138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, M.; Liu, X.; Liu, H.; Du, Z.; Chen, T.; Lian, G.; Li, D.; Wang, W. Multimodal fish feeding intensity assessment in aquaculture. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2025, 22, 9485–9497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Cheng, Y.; He, J.; Zhu, X. A review of small object detection based on deep learning. Neural Comput. Appl. 2024, 36, 6283–6303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Zhang, K.; Wei, H.; Chen, W.; Zhao, T. Underwater image quality optimization: Researches, challenges, and future trends. Image Vis. Comput. 2024, 146, 104995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastegari, H.; Nadi, F.; Lam, S.S.; Ikhwanuddin, M.; Kasan, N.A.; Rahmat, R.F.; Mahari, W.A.W. Internet of things in aquaculture: A review of the challenges and potential solutions based on current and future trends. Smart Agric. Technol. 2023, 4, 100187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Date | Time | Feeding Amount | Date | Time | Feeding Amount |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 23 June | 5:56 | Strong | 8 July | 5:22 | Medium |

| 17:46 | Strong | 17:12 | Strong | ||

| 17:39 | Medium | 17:10 | Medium | ||

| 27 June | 5:21 | Medium | 17 July | 5:18 | Medium |

| 5:44 | Strong | 17:08 | Medium | ||

| 16:59 | Medium | 17:06 | Strong | ||

| 2 July | 5:25 | Strong | 24 July | 5:30 | Strong |

| 5:54 | Strong | 17:17 | Medium |

| Intensity Index | Formula | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Total area | Total area represents the proportion of the area occupied by the fish school in each frame relative to the total area of the observation region; represents the total area of the observation region; represents the union area of all instances in this frame. | |

| Nearest Neighbor Distance | Nearest neighbor distance refers to the average distance between each individual in the fish school and its nearest neighbor; dist(i,j) is the Euclidean distance between individual i and j; n is the number of individuals in the calculation. | |

| Area Growth Rate | Area growth rate represents the rate of change in the fish school’s area over a unit of time; is the fish school area at the current time point; is the fish school area at the previous time point; is the time interval. | |

| Cluster Count | Cluster count represents the number of valid clusters in the current frame; a cluster refers to a group of fish within the school that exhibits a certain degree of aggregation; represents the number of valid clusters in this frame (after removing small noise, non-fish instances, and instances outside the ROI). | |

| Perimeter-to-Area Ratio | The perimeter-to-area ratio is the ratio of the fish school’s external contour perimeter (P) to the fish school’s area (A). |

| Model | P2 | RCSOSA | LSDECD | Box P/% | Box R/% | mAP @50/% | mAP @50–95/% | Mask P/% | Mask R/% | mAP @50/% | mAP @50–95/% | FPS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N1 | 79 | 76.9 | 81.1 | 46.9 | 68.1 | 64 | 66.2 | 27 | 116.09 | |||

| N2 | √ | 82 | 81.6 | 84.8 | 49.6 | 76.7 | 75.7 | 78.5 | 35.1 | 95.06 | ||

| N3 | √ | 79.2 | 75.9 | 80.2 | 46.1 | 68.9 | 65.4 | 67.9 | 28 | 151.59 | ||

| N4 | √ | 80.7 | 76.9 | 81.6 | 46.9 | 68.4 | 65.5 | 66.6 | 27.4 | 107.47 | ||

| N5 | √ | √ | 80.6 | 80.8 | 84.8 | 50 | 75.4 | 74.4 | 78.1 | 35.2 | 128.01 | |

| N6 | √ | √ | 81.8 | 82.2 | 86 | 51.4 | 77.8 | 74.5 | 79.1 | 35.4 | 90.13 | |

| N7 | √ | √ | 80.3 | 76.3 | 81 | 46.4 | 69.9 | 65.3 | 67.6 | 27.8 | 138.66 | |

| N8 | √ | √ | √ | 82.8 | 80.1 | 85.7 | 50.6 | 78.5 | 74.7 | 79.4 | 35.6 | 112.13 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Han, X.; Zhang, S.; Cheng, T.; Yang, S.; Fan, M.; Lu, J.; Guo, A. FishSegNet-PRL: A Lightweight Model for High-Precision Fish Instance Segmentation and Feeding Intensity Quantification. Fishes 2025, 10, 630. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes10120630

Han X, Zhang S, Cheng T, Yang S, Fan M, Lu J, Guo A. FishSegNet-PRL: A Lightweight Model for High-Precision Fish Instance Segmentation and Feeding Intensity Quantification. Fishes. 2025; 10(12):630. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes10120630

Chicago/Turabian StyleHan, Xinran, Shengmao Zhang, Tianfei Cheng, Shenglong Yang, Mingjun Fan, Jun Lu, and Ai Guo. 2025. "FishSegNet-PRL: A Lightweight Model for High-Precision Fish Instance Segmentation and Feeding Intensity Quantification" Fishes 10, no. 12: 630. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes10120630

APA StyleHan, X., Zhang, S., Cheng, T., Yang, S., Fan, M., Lu, J., & Guo, A. (2025). FishSegNet-PRL: A Lightweight Model for High-Precision Fish Instance Segmentation and Feeding Intensity Quantification. Fishes, 10(12), 630. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes10120630