Spatiotemporal and Environmental Effects on Demersal Fishes Along the Nearshore Texas Continental Shelf

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

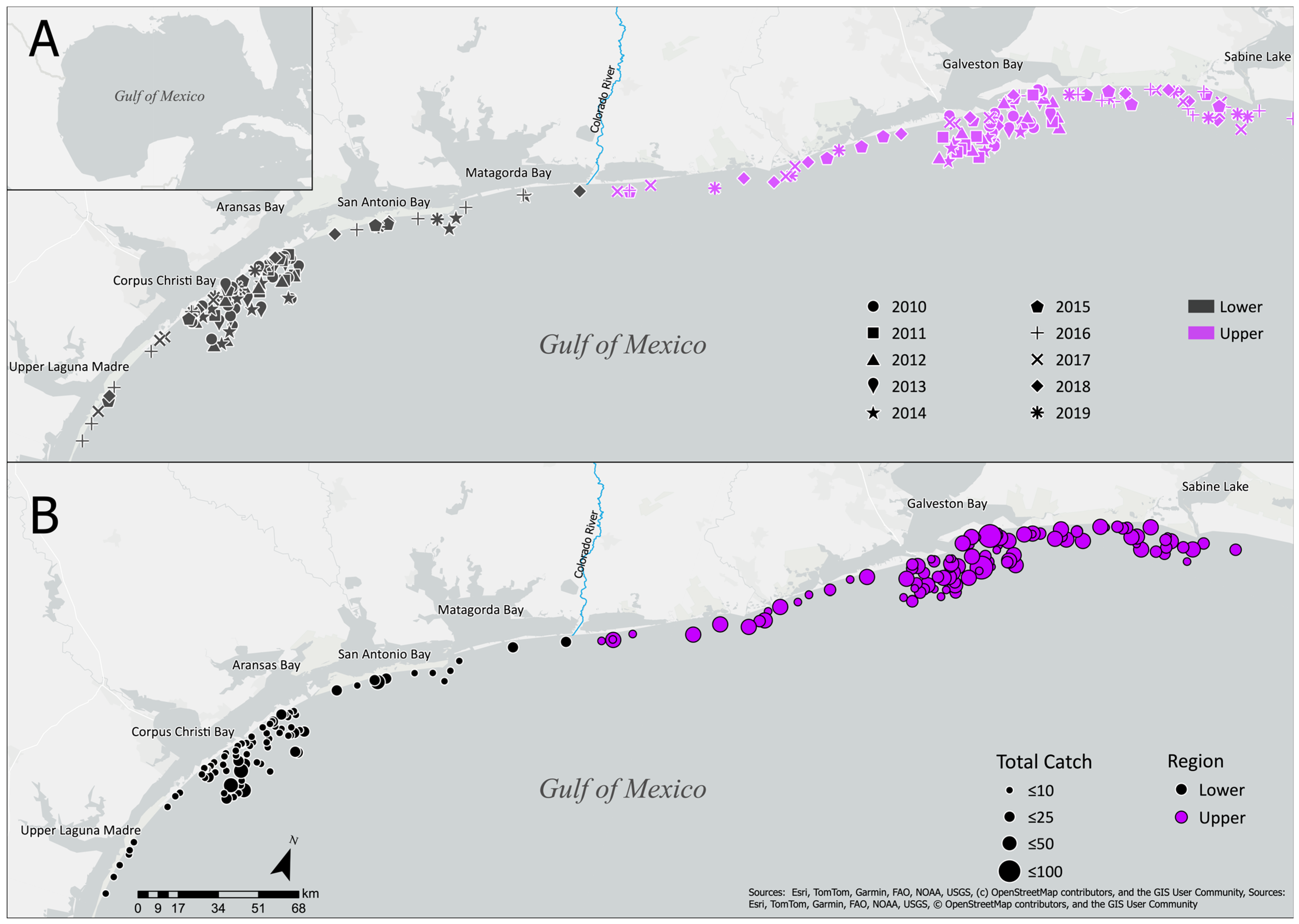

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Survey Protocol

2.3. Data Standardization

2.4. Species Composition and Relative Abundance

2.5. Predicted Presence Probability

3. Results

3.1. Data Summary

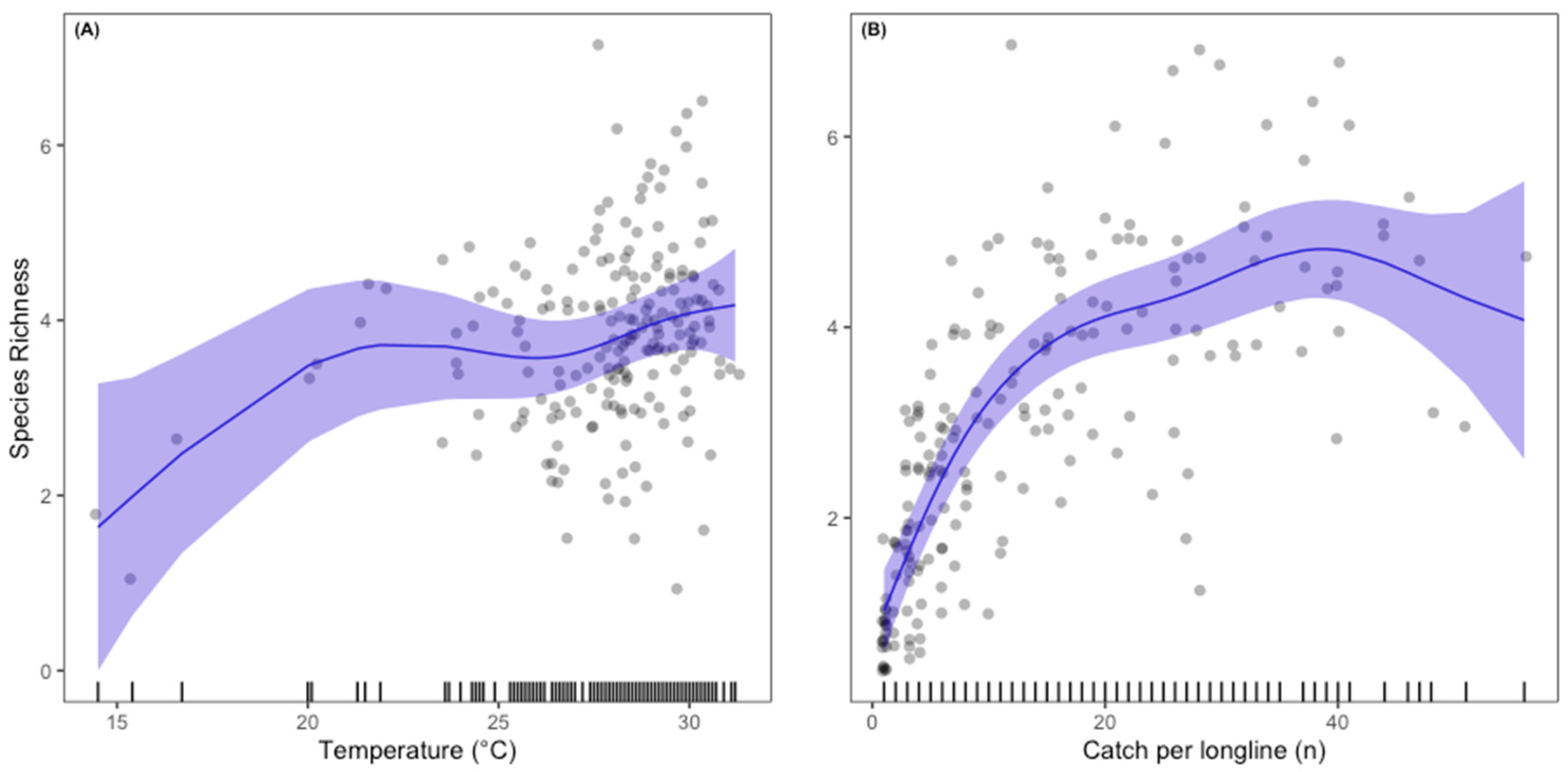

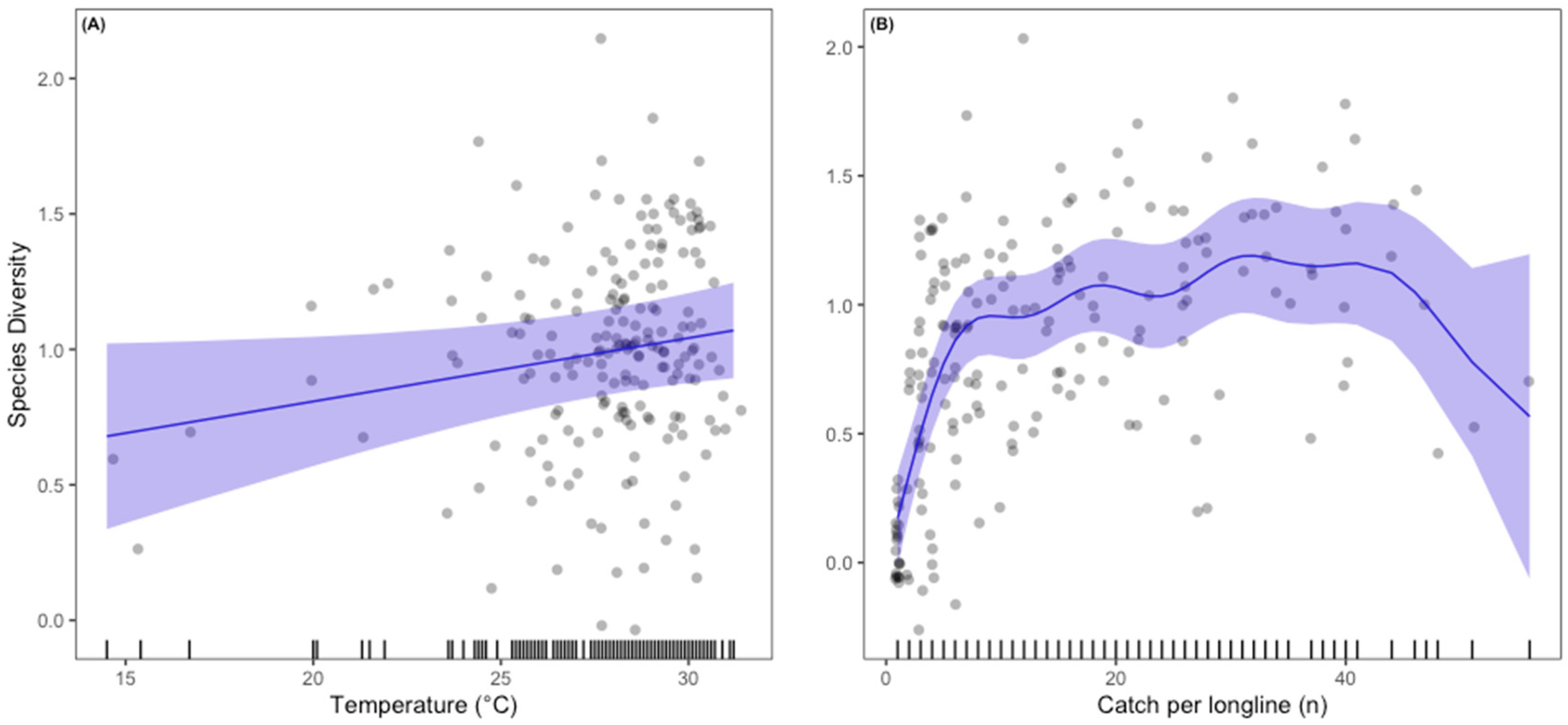

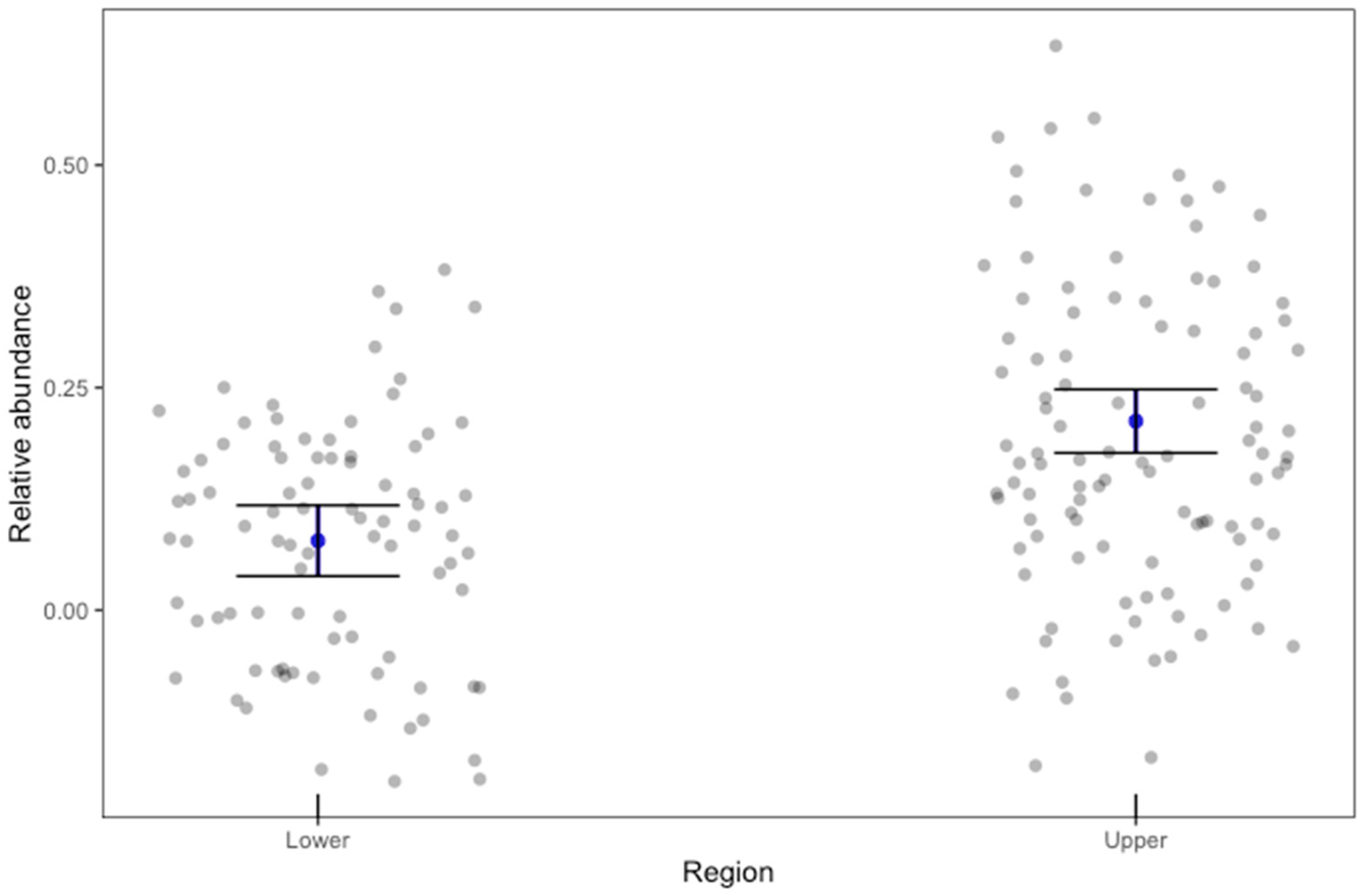

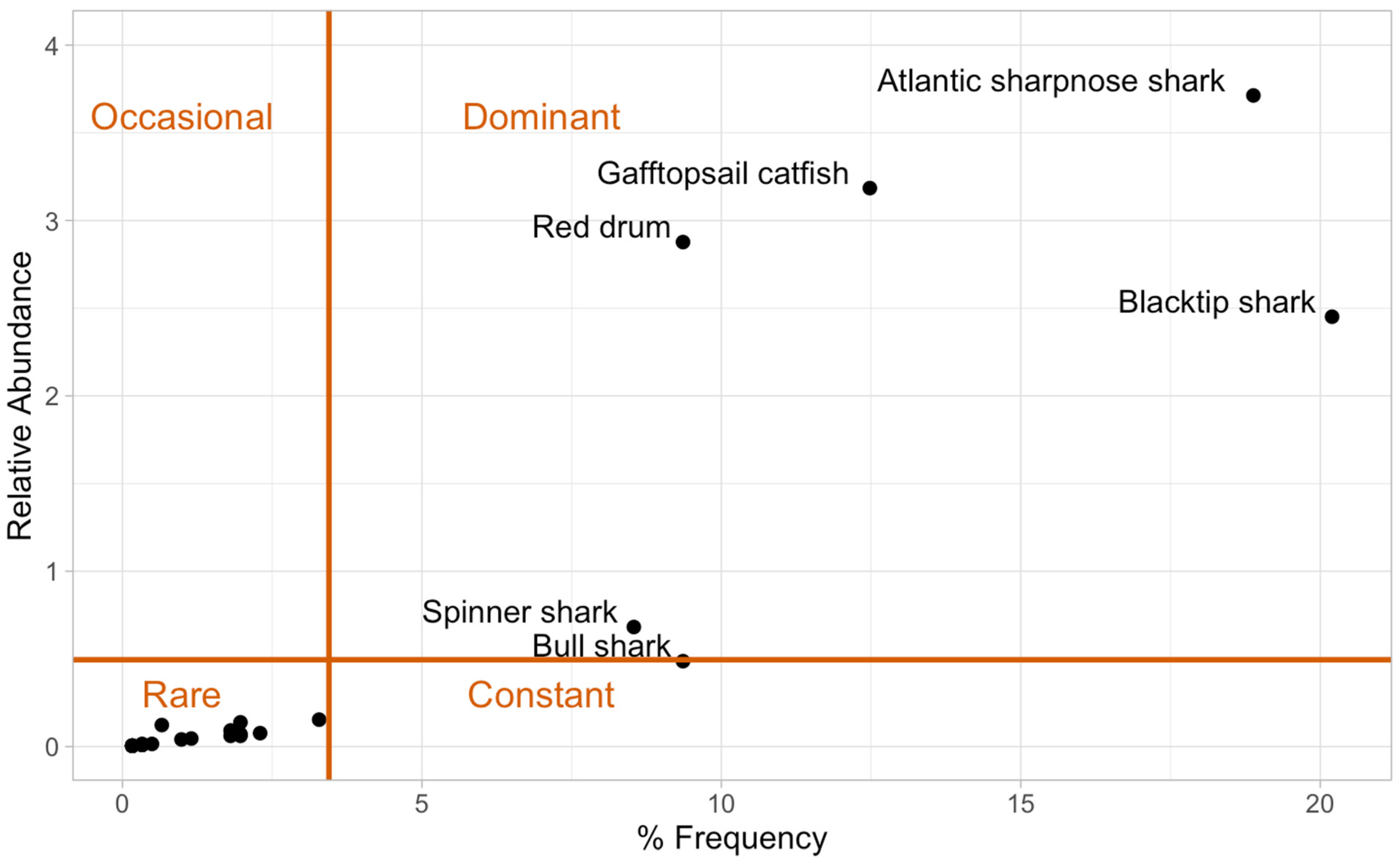

3.2. Species Composition and Relative Abundance

3.3. Predicted Presence Probability

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GoM | Gulf of Mexico |

| TPWD | Texas Parks & Wildlife Department |

| SEAMAP | Southeast Area Monitoring and Assessment Program |

| NMFS | National Marine Fisheries Service |

| CPUE | Catch Per Unit Effort |

| DO | Dissolved Oxygen |

| AICc | Corrected Akaike Information Criterion |

| edf | Effective Degrees of Freedom |

| GAMs | Generalizes Additive Models |

References

- Nogueira, A.; Gonzalez-Troncoso, D.; Tolimieri, N. Changes and Trends in the Overexploited Fish Assemblages of Two Fishing Grounds of the Northwest Atlantic. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2015, 73, 345–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steichen, J.; Quigg, A. Fish Species as Indicators of Freshwater Inflow within a Subtropical Estuary in the Gulf of Mexico. Ecol. Indic. 2018, 85, 180–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, H.; Johnson, K.; Kelly, M. Synergistic Effects of Temperature and Salinity on the Gene Expression and Physiology of Crassostrea virginica. Integr. Comp. Biol. 2019, 59, 306–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vergés, A.; Steinberg, P.D.; Hay, M.E.; Poore, A.G.B.; Campbell, A.H.; Ballesteros, E.; Heck, K.L.; Booth, D.J.; Coleman, M.A.; Feary, D.A.; et al. The Tropicalization of Temperate Marine Ecosystems: Climate-Mediated Changes in Herbivory and Community Phase Shifts. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2014, 281, 20140846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zenteno-Savín, T. Diurnal and Seasonal Hsp70 Gene Expression in a Cryptic Reef Fish, the Bluebanded Goby Lythrypnus dalli (Gilbert 1890). Biotecnia 2021, 23, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radfar, S.; Moftakhari, H.; Moradkhani, H. Rapid Intensification of Tropical Cyclones in the Gulf of Mexico Is More Likely during Marine Heatwaves. Commun. Earth Environ. 2024, 5, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Boyer, T.; Reagan, J.; Hogan, P. Upper-Oceanic Warming in the Gulf of Mexico between 1950 and 2020. J. Clim. 2023, 36, 2721–2734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilford, D.M.; Giguere, J.; Pershing, A.J. Human-Caused Ocean Warming Has Intensified Recent Hurricanes. Environ. Res. Clim. 2024, 3, 045019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujiwara, M.; Martinez-Andrade, F.; Wells, R.J.D.; Fisher, M.; Pawluk, M.; Livernois, M.C. Climate-Related Factors Cause Changes in the Diversity of Fish and Invertebrates in Subtropical Coast of the Gulf of Mexico. Commun. Biol. 2019, 2, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabalais, N.N.; Turner, R.E. Gulf of Mexico Hypoxia: Past, Present, and Future. Limnol. Ocean. Bull. 2019, 28, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohner, T.; Dixon, D. The Value of Long-Term Environmental Monitoring Programs: An Ohio River Case Study. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2013, 185, 9385–9396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabalais, N.; Turner, R.E.; Scavia, D. Beyond Science into Policy: Gulf of Mexico Hypoxia and the Mississippi River: Nutrient Policy Development for the Mississippi River Watershed Reflects the Accumulated Scientific Evidence That the Increase in Nitrogen Loading Is the Primary Factor in the Worsening of Hypoxia in the Northern Gulf of Mexico. BioScience 2002, 52, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murawski, S.A.; Peebles, E.B.; Gracia, A.; Tunnell, J.W.; Armenteros, M. Comparative Abundance, Species Composition, and Demographics of Continental Shelf Fish Assemblages throughout the Gulf of Mexico. Mar. Coast. Fish. 2018, 10, 325–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, R.J.D.; Harper, J.O.; Rooker, J.R.; Landry, A.M., Jr.; Dellapenna, T.M. Fish Assemblage Structure on a Drowned Barrier Island in the Northwestern Gulf of Mexico. Hydrobiologia 2009, 625, 207–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monk, M.; Powers, J.; Brooks, E. Spatial Patterns in Species Assemblages Associated with the Northwestern Gulf of Mexico Shrimp Trawl Fishery. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2015, 519, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, C.; Tunnell, J., Jr. Habitats and Biota of the Gulf of Mexico: An Overview. In Habitats and Biota of the Gulf of Mexico: Before the Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ajemian, M.; Wetz, J.; Shipley-Lozano, B.; Shively, J.D.; Stunz, G. An Analysis of Artificial Reef Fish Community Structure along the Northwestern Gulf of Mexico Shelf: Potential Impacts of “Rigs-to-Reefs” Programs. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0126354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendelssohn, I.; Byrnes, M.; Kneib, R.; Vittor, B. Coastal Habitats of the Gulf of Mexico. In Habitats and Biota of the Gulf of Mexico: Before the Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 359–640. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, J.W.; Tunnicliffe, V. Oxygen Limitations on Marine Animal Distributions and the Collapse of Epibenthic Community Structure during Shoaling Hypoxia. Glob. Change Biol. 2015, 21, 2989–3004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heupel, M.; Yeiser, B.; Collins, A.; Ortega, L.; Cimpfendorfer, C. Long-Term Presence and Movement Patterns of Juvenile Bull Sharks, Carcharhinus leucas, in an Estuarine River System. Mar. Freshw. Res. 2010, 61, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendon, J.M.; Hoffmayer, E.R.; Pollack, A.G.; Mareska, J.; Martinez-Andrade, F.; Rester, J.; Switzer, T.S.; Zuckerman, Z.C. Impacts of Survey Design on a Gulf of Mexico Bottom Longline Survey and the Transition to a Unified, Stratified - Random Design. Front. Mar. Sci. 2025, 11, 1426756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugica, K.; Sterba-Boatwright, B.; Wetz, M.S. Water Quality Trends in Texas Estuaries. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020, 152, 110903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menezes, G.; Sigler, M.F. Longlines. In Biological Sampling in the Deep Sea; Clark, M.R., Consalvey, M., Rowden, A.A., Eds.; Wiley Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 159–183. [Google Scholar]

- Drymon, J.M.; Carassou, L.; Powers, S.P.; Grace, M.; Dindo, J.; Dzwonkowski, B. Multiscale Analysis of Factors That Affect the Distribution of Sharks throughout the Northern Gulf of Mexico. Fish. Bull. 2013, 111, 370–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Q. A Relationship between Species Richness and Evenness That Depends on Specific Relative Abundance Distribution. PeerJ 2018, 6, e4951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oksanen, J.; Simpson, G.L.; Blanchet, F.G.; Kindt, R.; Legendre, P.; Minchin, P.R.; O’Hara, R.B.; Solymos, P.; Stevens, M.H.H.; Szoecs, E.; et al. Vegan: Community Ecology Package 2001, 2.7-2. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/vegan/index.html (accessed on 3 October 2025).

- Shannon, C.E. A Mathematical Theory of Communication. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 1948, 27, 379–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, M.L.; Roberts, N.M.; Bauder, J.M. Relationships of Catch-per-Unit-Effort Metrics with Abundance Vary Depending on Sampling Method and Population Trajectory. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0233444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotelli, N.J.; Colwell, R.K. Quantifying Biodiversity: Procedures and Pitfalls in the Measurement and Comparison of Species Richness. Ecol. Lett. 2001, 4, 379–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwinn, D.C.; Allen, M.S.; Bonvechio, K.I.; Hoyer, M.V.; Beesley, L.S. Evaluating Estimators of Species Richness: The Importance of Considering Statistical Error Rates. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2016, 7, 294–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, S.N. Fast Stable Restricted Maximum Likelihood and Marginal Likelihood Estimation of Semiparametric Generalized Linear Models. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Stat. Methodol. 2011, 73, 3–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuur, A.; Ieno, E.; Walker, N.; Saveliev, A.; Smith, G. Mixed Effects Models and Extensions in Ecology with R; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009; ISBN 978-0-387-87457-9. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, D.; Burnham, K. Model Selection and Multimodel Inference: A Practical Information-Theoretic Approach; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2002; ISBN 978-0-387-95364-9. [Google Scholar]

- Olmstead, P.S.; Tukey, J.W. A Corner Test for Association. Ann. Math. Stat. 1947, 18, 495–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livernois, M.C.; Power, S.; Albins, M. Habitat Associations and Co-Occurrence Patterns of Two Estuarine-Dependent Predatory Fishes. Mar. Coast. Fish. 2020, 12, 64–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCabe, C.; Halvorson, M.; King, K.; Cao, X.; Kim, D. Interpreting Interaction Effects in Generalized Linear Models of Nonlinear Probabilities and Counts. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2021, 57, 243–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezneat, D. Regional Environments and Topographic Features. In The American Sea: A Natural History of the Gulf of Mexico; Texas A&M University Press: College Station, TX, USA, 2015; pp. 38–59. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, A.; Hayes, C.; Booth, D.J.; Nagelkerken, I. Future Shock: Ocean Acidification and Seasonal Water Temperatures Alter the Physiology of Competing Temperate and Coral Reef Fishes. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 883, 163684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindmark, M.; Audzijonyte, A.; Blanchard, J.L.; Gårdmark, A. Temperature Impacts on Fish Physiology and Resource Abundance Lead to Faster Growth but Smaller Fish Sizes and Yields under Warming. Glob. Change Biol. 2022, 28, 6239–6253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharf, F.S.; Schlight, K.K. Feeding Habits of Red Drum (Sciaenops ocellatus) in Galveston Bay, Texas: Seasonal Diet Variation and Predator-Prey Size Relationships. Estuaries 2000, 23, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.L.; Zimmerman, R.J.; Minello, T.J. Abundance patterns of juvenile blue crabs (Callinectes sapidus) in nursery habitats of two Texas bays. Bull. Mar. Sci. 1990, 46, 115–125. [Google Scholar]

- Marchessaux, G.; Gjoni, V.; Sarà, G. Environmental Drivers of Size-Based Population Structure, Sexual Maturity and Fecundity: A Study of the Invasive Blue Crab Callinectes sapidus (Rathbun, 1896) in the Mediterranean Sea. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0289611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cottrant, E.; Matich, P.; Fisher, M. Boosted Regression Tree Models Predict the Diets of Juvenile Bull Sharks in a Subtropical Estuary. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2021, 659, 127–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TinHan, T.C.; Wells, R.J.D. Spatial and Ontogenetic Patterns in the Trophic Ecology of Juvenile Bull Sharks (Carcharhinus leucas) From the Northwest Gulf of Mexico. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 664316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osmany, H.B.; Moazzam, M. Species composition, commercial landings, distribution and some aspects of biology of shark (Class Pisces) of Pakistan: Large demersal sharks. Int. J. Biol. Biotechnol. 2022, 19, 89–111. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.; Franco, A.C.; Sumaila, U.R. A Selected Review of Impacts of Ocean Deoxygenation on Fish and Fisheries. Fishes 2023, 8, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nodo, P.; Childs, A.-R.; Pattrick, P.; Lemley, D.A.; James, N.C. Response of Demersal Fishes to Low Dissolved Oxygen Events in Two Eutrophic Estuaries. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2023, 293, 108514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchheister, A.; Bonzek, C.; Gartland, J.; Latour, R. Patterns and Drivers of the Demersal Fish Community of Chesapeake Bay. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2013, 481, 161–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, J.R.; Condon, N.E.; Drazen, J.C. Gill Surface Area and Metabolic Enzyme Activities of Demersal Fishes Associated with the Oxygen Minimum Zone off California. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2012, 57, 1701–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robb, T.; Abrahams, M.V. Variation in Tolerance to Hypoxia in a Predator and Prey Species: An Ecological Advantage of Being Small? J. Fish Biol. 2003, 62, 1067–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, G.E.; Östlund-Nilsson, S. Does Size Matter for Hypoxia Tolerance in Fish? Biol. Rev. 2008, 83, 173–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hubert, W.; Pope, K.; Dettmers, J. Passive Capture Techniques. In Fisheries Techniques; Zale, A.V., Parrish, D.L., Sutton, T.M., Eds.; American Fisheries Society: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2012; pp. 223–265. [Google Scholar]

| Common Name | Scientific Name | n | TL/DW (mm) | Freq | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Min | Max | ||||

| Atlantic Sharpnose Shark | Rhizoprionodon terraenovae | 724 | 891 | 134.0 | 335 | 1136 | 115 |

| Gafftopsail Catfish | Bagre marinus | 621 | 514 | 55.8 | 195 | 880 | 76 |

| Red Drum | Sciaenops ocellatus | 561 | 935 | 60.7 | 745 | 1876 | 57 |

| Blacktip Shark | Carcharhinus limbatus | 478 | 1282 | 268.3 | 439 | 1923 | 123 |

| Spinner Shark | Carcharhinus brevipinna | 133 | 1118 | 345.2 | 645 | 2040 | 52 |

| Bull Shark | Carcharhinus leucas | 95 | 1705 | 330.5 | 886 | 2743 | 57 |

| Finetooth Shark | Carcharhinus isodon | 30 | 1080 | 290.3 | 650 | 1453 | 20 |

| Blacknose Shark | Carcharhinus acronotus | 27 | 1098 | 53.8 | 944 | 1173 | 12 |

| Sandbar Shark | Carcharhinus plumbeus | 24 | 1104 | 174.6 | 881 | 1575 | 4 |

| Black Drum | Pogonias cromis | 18 | 829 | 76.9 | 638 | 993 | 11 |

| Scalloped Hammerhead | Sphyrna lewini | 15 | 1563 | 645.6 | 543 | 2474 | 14 |

| Southern Stingray | Hypanus americanus | 14 | 1053 | 221.0 | 775 | 1394 | 12 |

| Great Hammerhead | Sphyrna mokarran | 12 | 2147 | 275.3 | 1700 | 2689 | 11 |

| Hardhead Catfish | Ariopsis felis | 12 | 350 | 29.9 | 294 | 406 | 12 |

| Bonnethead | Sphyrna tiburo | 9 | 971 | 149.6 | 711 | 1182 | 7 |

| Roughtail Stingray | Bathytoshia centroura | 8 | 1020 | 246.5 | 787 | 1534 | 6 |

| Sharksucker | Echeneis naucrates | 3 | 140 | 7.6 | 132 | 147 | 2 |

| Tiger Shark | Galeocerdo cuvier | 3 | 2041 | 236.2 | 1874 | 2208 | 3 |

| Atlantic Stingray | Hypanus sabinus | 2 | 686 | 178.9 | 559 | 812 | 2 |

| Bluntnose Stingray | Hypanus say | 2 | 1063 | 89.1 | 1000 | 1126 | 2 |

| Lemon Shark | Negaprion brevirostris | 2 | 2558 | 345.8 | 2313 | 2802 | 2 |

| Spanish Mackerel | Scomberomorus maculatus | 2 | 586 | 54.5 | 547 | 624 | 2 |

| Crevalle Jack | Caranx hippos | 1 | 972 | 1 | |||

| Dolphinfish | Coryphaena hippurus | 1 | 828 | 1 | |||

| Snapper Eel | Echiophis punctifer | 1 | 733 | 1 | |||

| Shrimp Eel | Ophichthus gomesi | 1 | 633 | 1 | |||

| Atlantic Thread Herring | Opisthonema oglinum | 1 | 215 | 1 | |||

| Cobia | Rachycentron canadum | 1 | 1184 | 1 | |||

| Cownose Ray | Rhinoptera bonasus | 1 | 880 | 1 | |||

| Total | 29 | 2802 | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Johnson, E.M.; Martinez-Andrade, F.; Domínguez-Sánchez, P.S.; Gaona-Hernandez, A.; Li, C.; Wells, R.J.D. Spatiotemporal and Environmental Effects on Demersal Fishes Along the Nearshore Texas Continental Shelf. Fishes 2025, 10, 632. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes10120632

Johnson EM, Martinez-Andrade F, Domínguez-Sánchez PS, Gaona-Hernandez A, Li C, Wells RJD. Spatiotemporal and Environmental Effects on Demersal Fishes Along the Nearshore Texas Continental Shelf. Fishes. 2025; 10(12):632. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes10120632

Chicago/Turabian StyleJohnson, Erin M., Fernando Martinez-Andrade, P. Santiago Domínguez-Sánchez, Aurora Gaona-Hernandez, Chengxue Li, and R. J. David Wells. 2025. "Spatiotemporal and Environmental Effects on Demersal Fishes Along the Nearshore Texas Continental Shelf" Fishes 10, no. 12: 632. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes10120632

APA StyleJohnson, E. M., Martinez-Andrade, F., Domínguez-Sánchez, P. S., Gaona-Hernandez, A., Li, C., & Wells, R. J. D. (2025). Spatiotemporal and Environmental Effects on Demersal Fishes Along the Nearshore Texas Continental Shelf. Fishes, 10(12), 632. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes10120632