Transcriptome Analysis Reveals the Mechanisms of Organismal Response in Exopalaemon carinicauda Infected by Metschnikowia bicuspidata

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

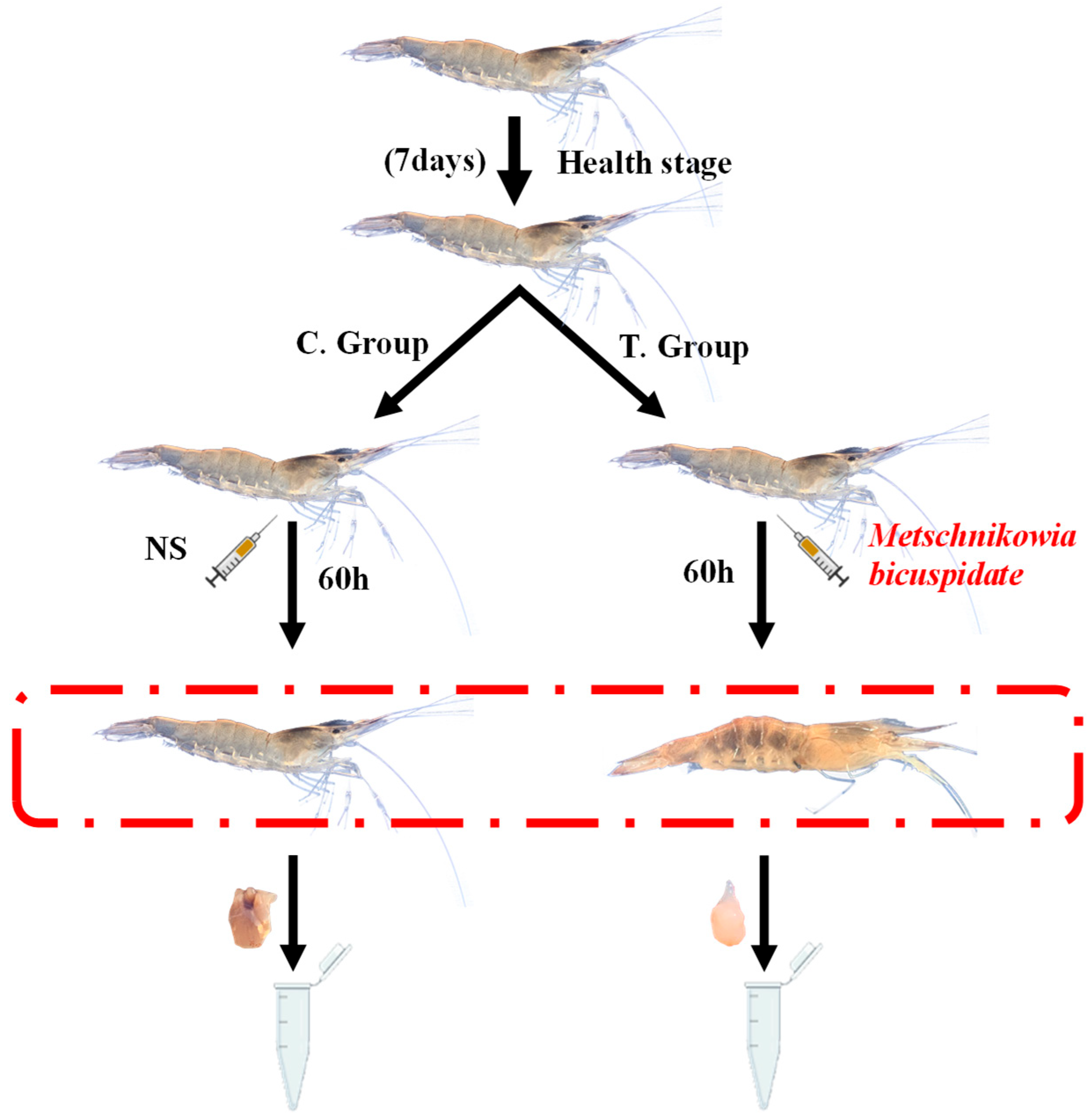

2.1. Experimental Infection and Sample Collection of E. carinicauda

2.2. RNA Extraction, cDNA Library Preparation, and Sequencing

2.3. Unigene Denovo Assembly and Annotation

2.4. Analysis of DEGs

2.5. Validation of DEGs from RNA-Seq

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

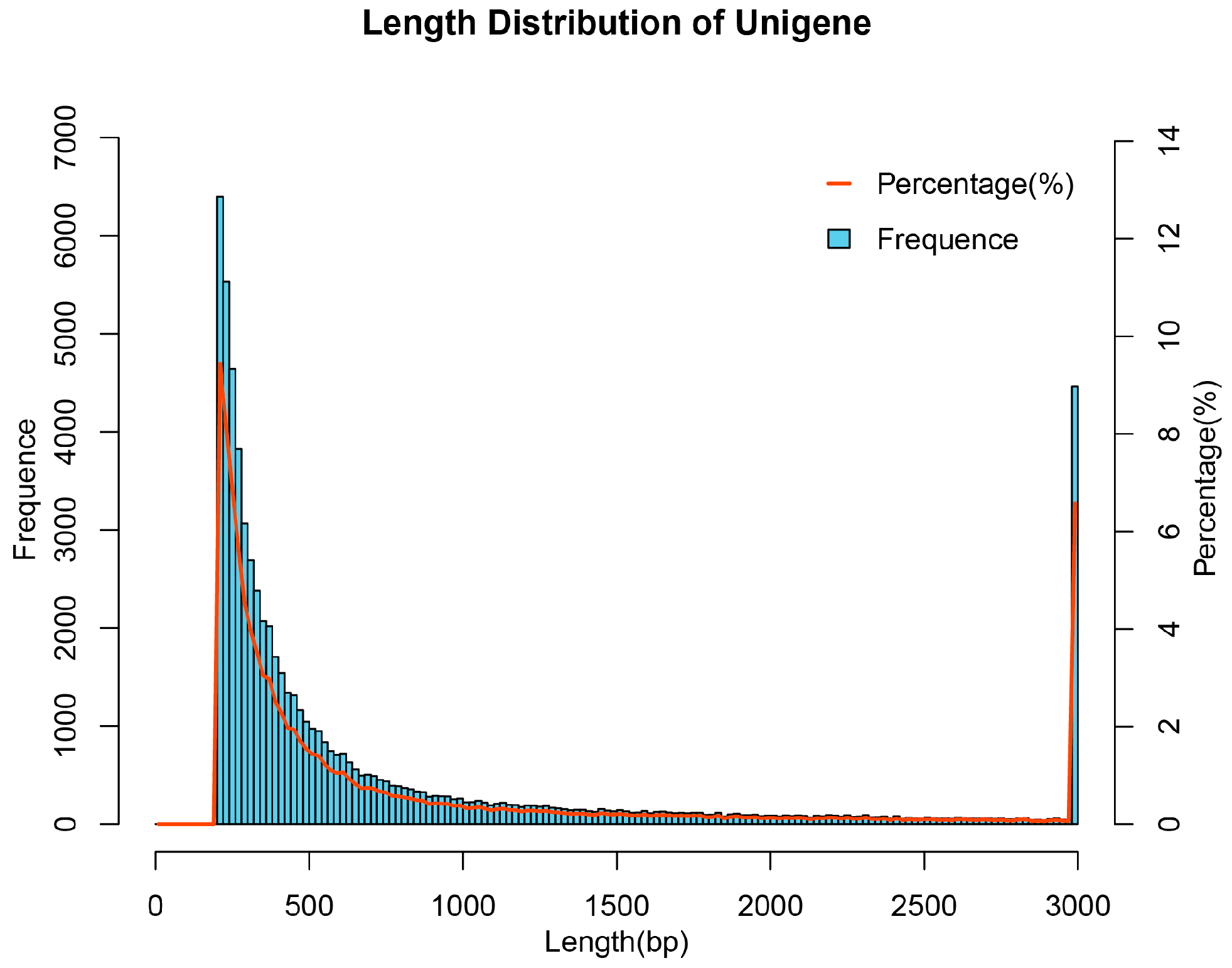

3.1. RNA-Seq Data Quality and De Novo Transcriptome Assembly

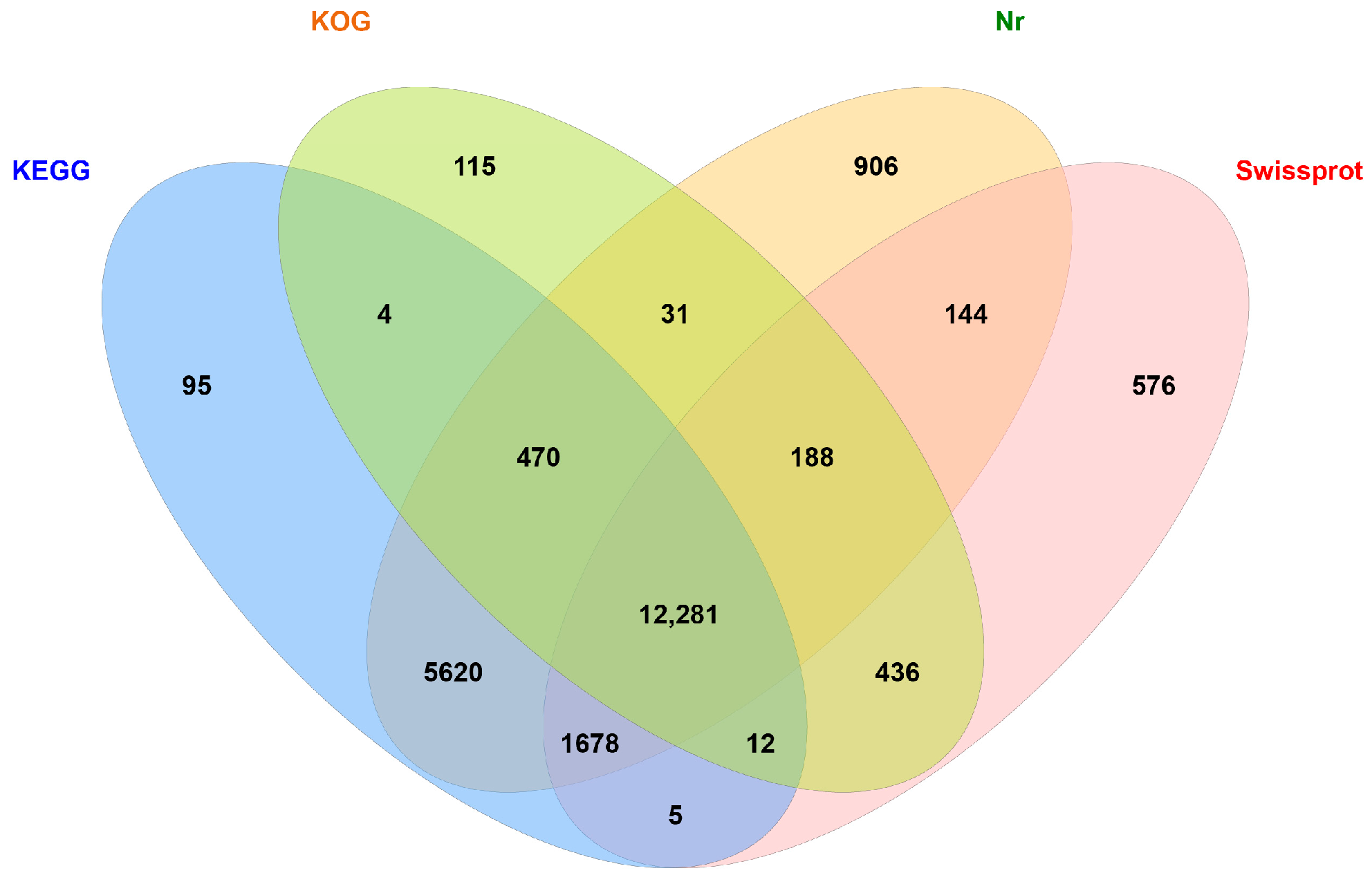

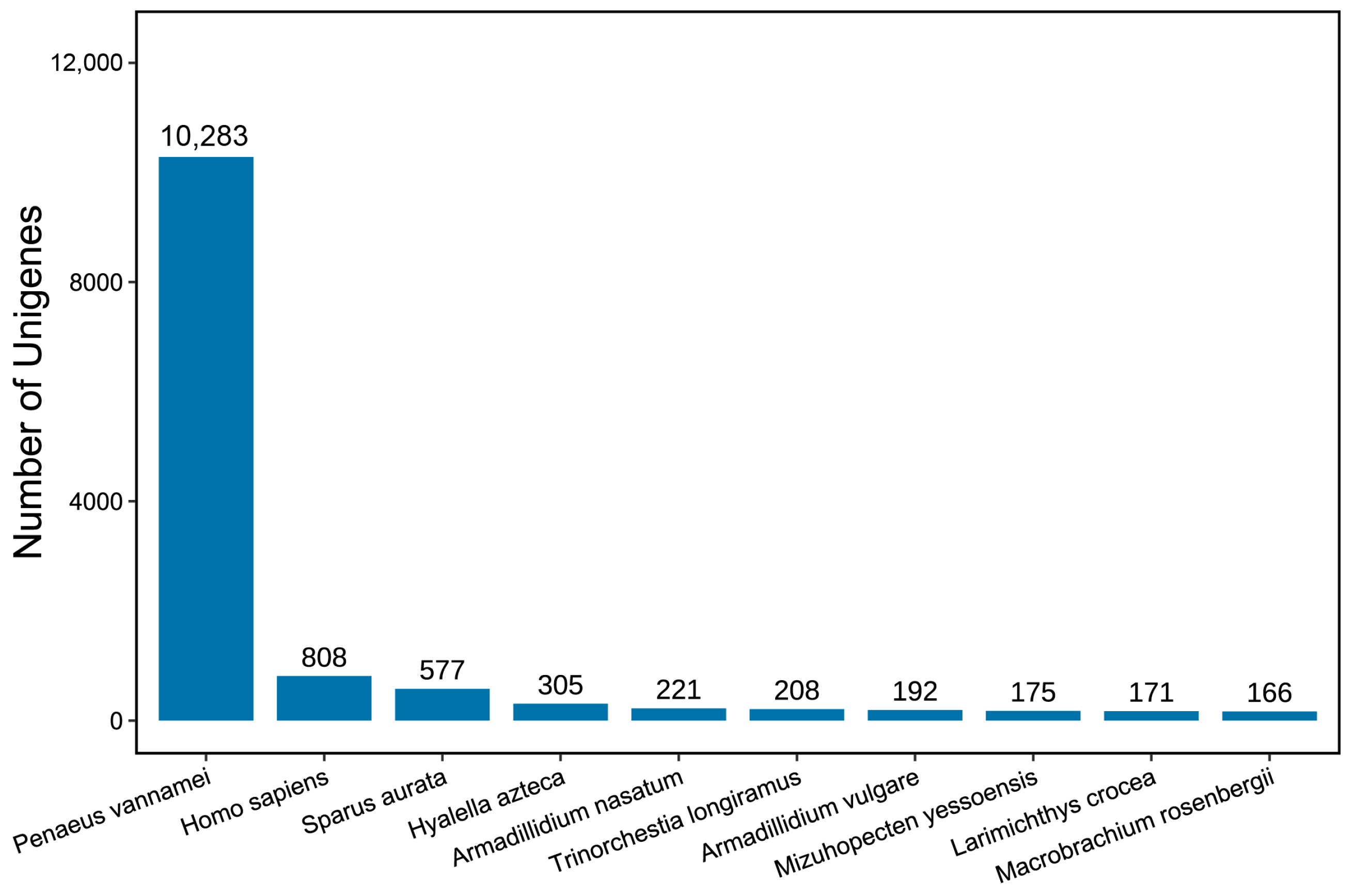

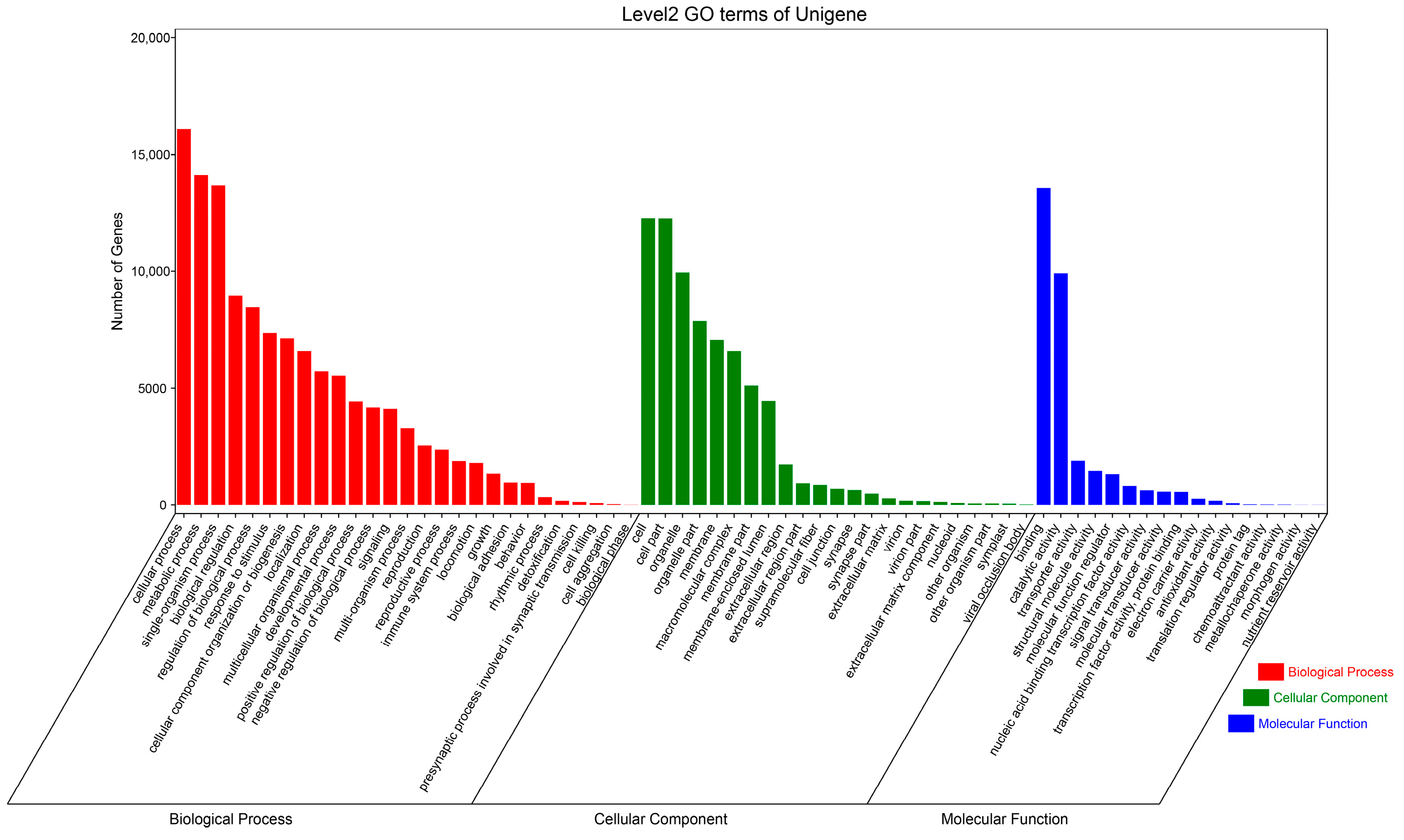

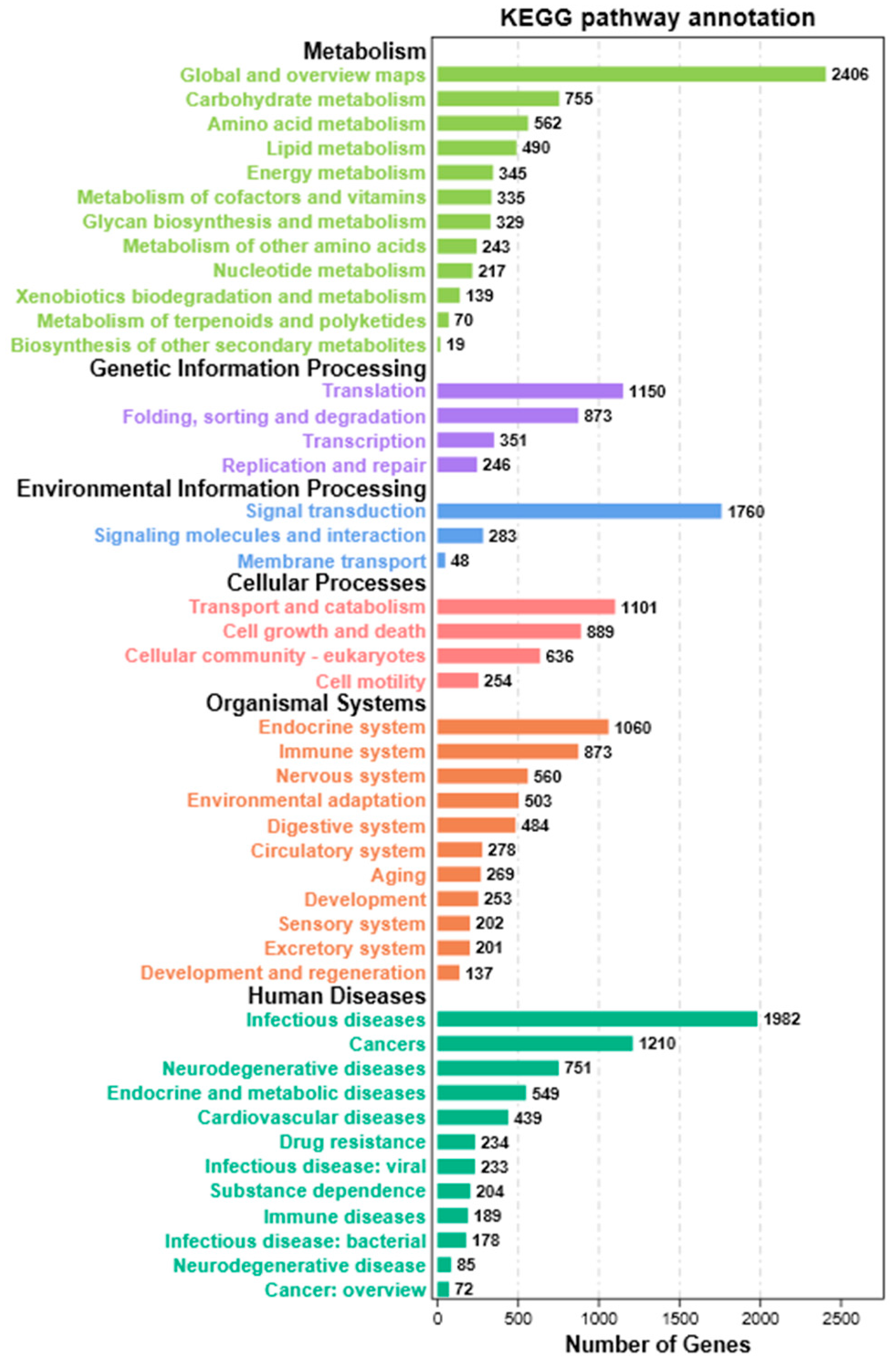

3.2. Function Annotation of Unigenes

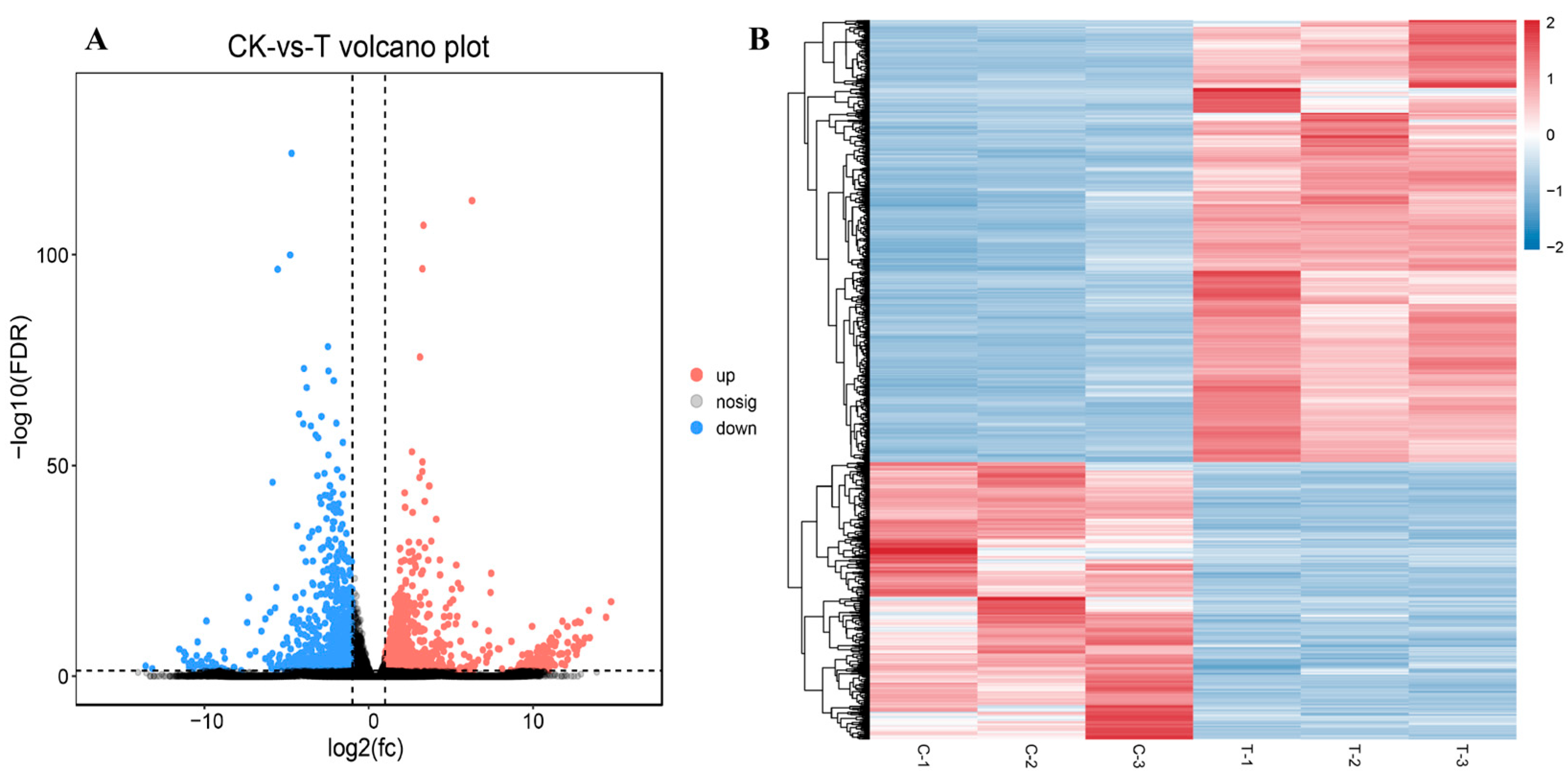

3.3. Identification and Analysis of DEGs

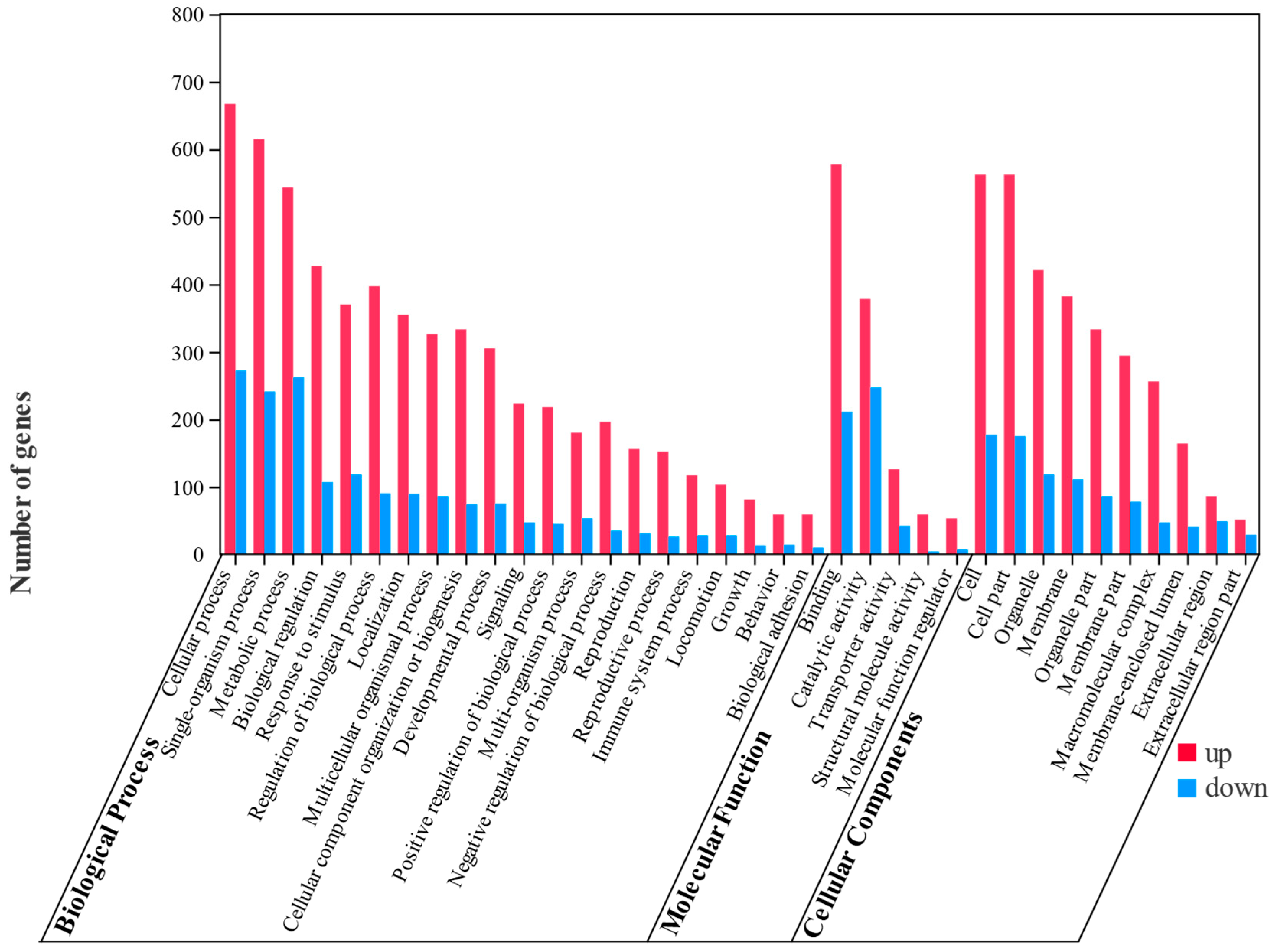

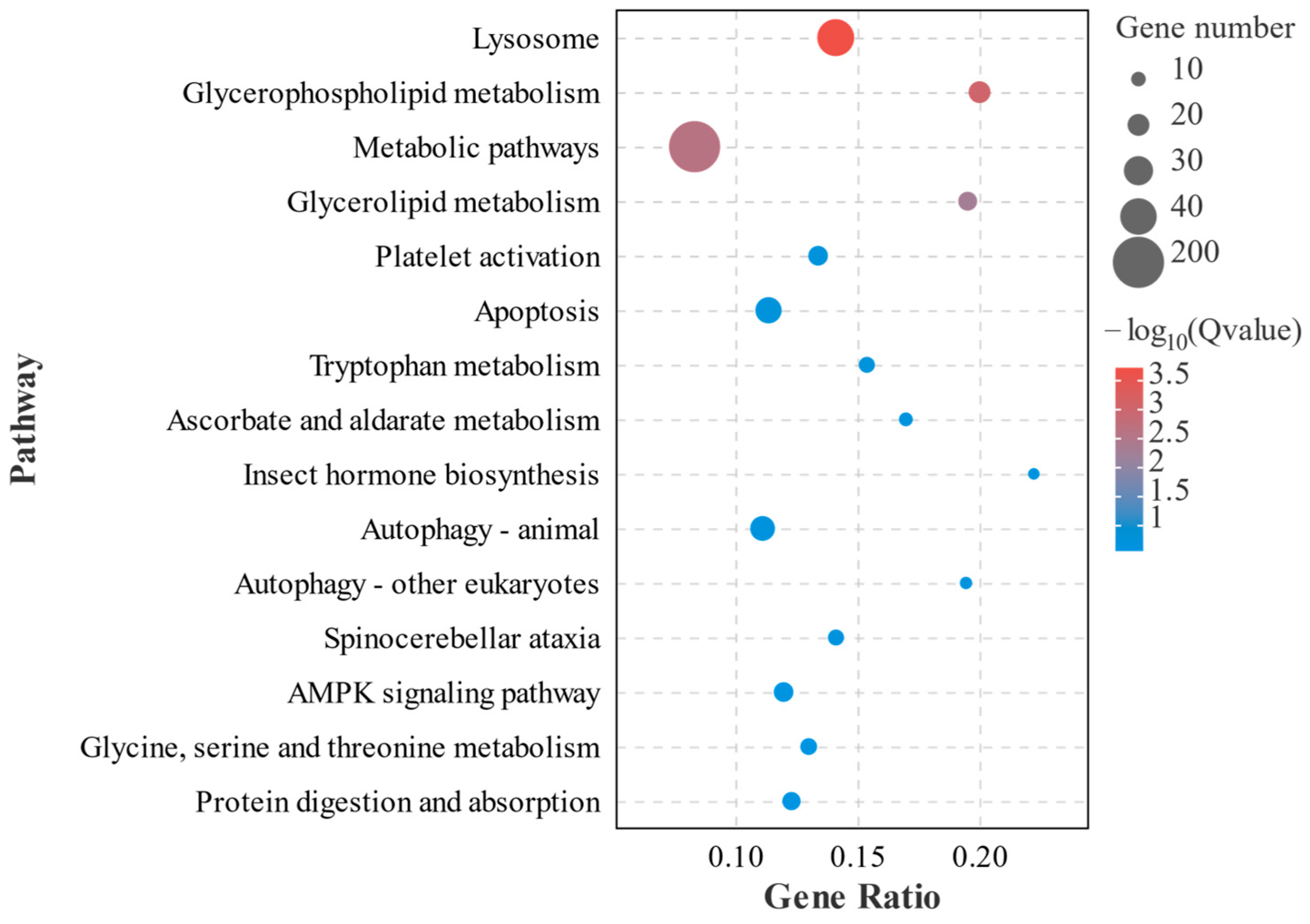

3.4. Analysis of Differentially Expressed Genes

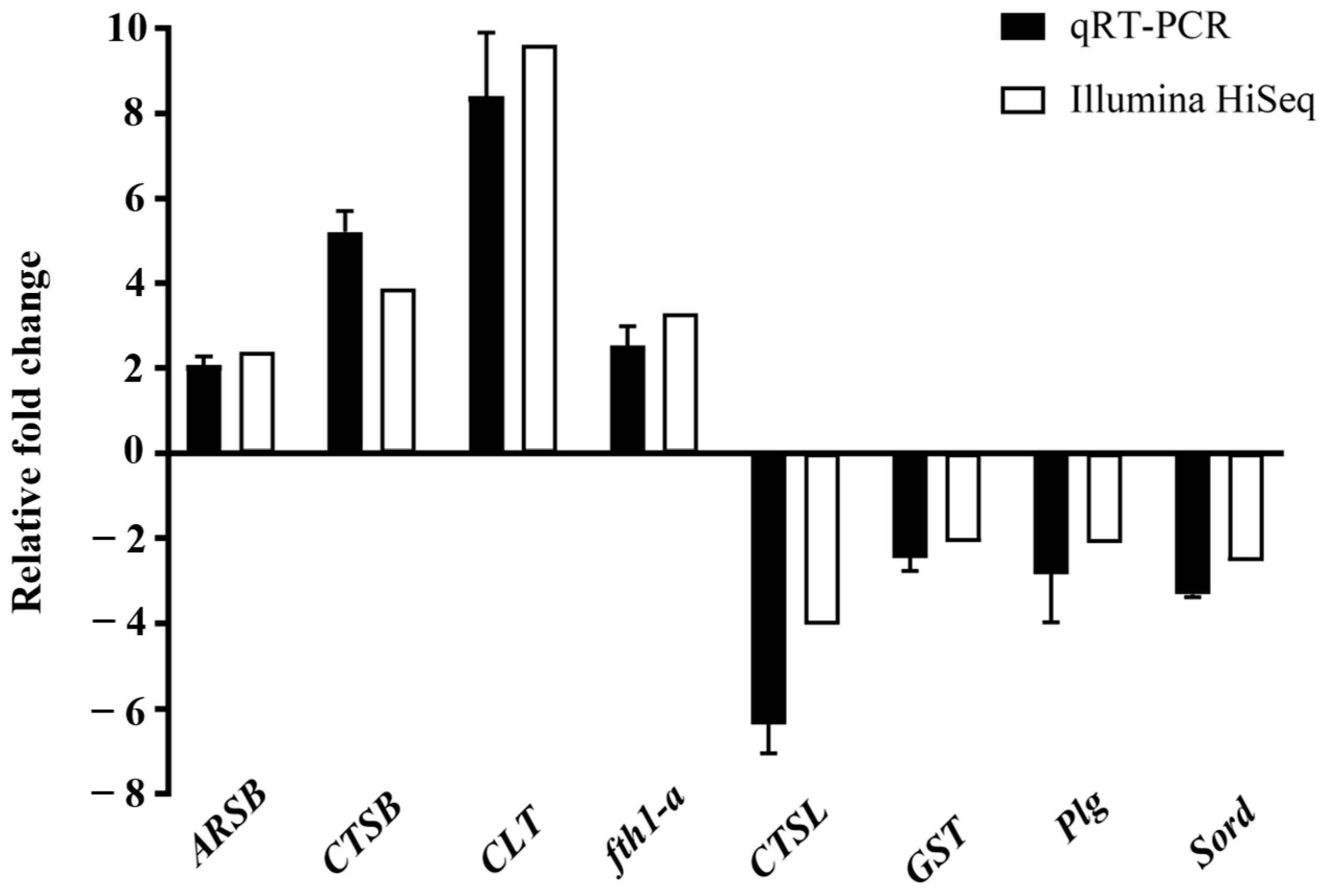

3.5. Validation of DEGs from RNA-Seq

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, J.; Feng, G.; Han, Z.; Zhang, T.; Chen, J.; Wu, J. Insights into the Intestinal Microbiota of Exopalaemon annandalei and Exopalaemon carinicauda in the Yangtze River Estuary. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1420928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Lv, J.; Shi, M.; Ge, Q.; Wang, Q.; He, Y.; Li, J.; Li, J. Chromosome-Level Genome Assembly of Ridgetail White Shrimp Exopalaemon carinicauda. Sci. Data 2024, 11, 576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Miao, X.; Li, C.; Xu, W.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Z. Genetic Variations of the Parasitic Dinoflagellate Hematodinium Infecting Cultured Marine Crustaceans in China. Protist 2016, 167, 597–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Q.; Li, J.; Li, J.; Wang, J.; Li, Z. Immune Response of Exopalaemon carinicauda Infected with an AHPND-Causing Strain of Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2018, 74, 223–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Liu, P.; Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Chen, P. Molecular Responses of Calreticulin Gene to Vibrio anguillarum and WSSV Challenge in the Ridgetail White Prawn Exopalaemon carinicauda. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2014, 36, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Shi, W.; Wang, L.; Li, H.; Yu, Z.; Hu, R.; Wu, X.; Shen, H.; Qi, Y.; Chen, J.; et al. A preliminary study on the “Zombie disease” of Exopalaemon carinicauda. J. Fish. China 2022, 47, 099414. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Chen, T.; Wang, P.; Chen, Y.; Huang, J.; Lin, Y.; Chaung, H. Metschnikowia bicuspidata and Enterococcus Faecium Co-Infection in the Giant Freshwater Prawn Macrobrachium rosenbergii. Dis. Aquat. Org. 2003, 55, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Yue, L.; Chi, Z.; Wang, X. Marine Killer Yeasts Active against a Yeast Strain Pathogenic to Crab Portunus trituberculatus. Dis. Aquat. Org. 2008, 80, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, J.; Jiang, H.; Shen, H.; Xing, Y.; Feng, C.; Li, X.; Chen, Q. First Description of Milky Disease in the Chinese Mitten Crab Eriocheir sinensis Caused by the Yeast Metschnikowia bicuspidata. Aquaculture 2021, 532, 735984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, T.; Gao, J.; Xu, W.; Liu, X.; Yan, B.; Azra, M.N.; Baloch, W.A.; Wang, P.; Gao, H. The Mannose-Binding Lectin (MBL) Gene Cloned from Exopalaemon carinicauda Plays a Key Role in Resisting Infection by Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2024, 274, 111001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.; Liu, Z.; Jiang, Q.; Xu, J.; An, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Xiong, D.; Wang, L. A Novel Ferritin Gene from Procambarus clarkii Involved in the Immune Defense against Aeromonas hydrophila Infection and Inhibits WSSV Replication. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2019, 86, 882–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, J.; Mao, Y.; Su, Y.; Wang, J. Identification of Two Novel C-Type Lectins Involved in Immune Defense against White Spot Syndrome Virus and Vibrio parahaemolyticus from Marsupenaeus japonicus. Aquaculture 2020, 519, 734797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Wang, L.; Liu, M.; Jiang, K.; Wang, M.; Yang, G.; Qi, C.; Wang, B. Transcriptome, Antioxidant Enzyme Activity and Histopathology Analysis of Hepatopancreas from the White Shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei Fed with Aflatoxin B1(AFB1). Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2017, 74, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, C.; Lv, X.; Chen, D.; Sun, B.; Guo, L.; Wang, S.; Ru, Y.; Wang, H.; Zeng, Q. Transcriptome Analysis of the Macrobrachium nipponense Hepatopancreas Provides Insights into Immunoregulation under Aeromonas veronii Infection. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 208, 111503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, Y.; Zhang, F.; Ma, C.; Wang, W.; Liu, Z.; Chen, W.; Zhao, M.; Ma, L. Comparative Metabolomics and Lipidomics of Four Juvenoids Application to Scylla paramamosain Hepatopancreas: Implications of Lipid Metabolism During Ovarian Maturation. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 886351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Shi, W.; Zhao, R.; Gu, C.; Shen, H.; Li, H.; Wang, L.; Cheng, J.; Wan, X. Integrated Physiological, Transcriptome, and Metabolome Analyses of the Hepatopancreas of Litopenaeus vannamei under Cold Stress. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part D Genom. Proteom. 2024, 49, 101196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metzker, M.L. Sequencing Technologies—The next Generation. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2010, 11, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Gerstein, M.; Snyder, M. RNA-Seq: A Revolutionary Tool for Transcriptomics. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2009, 10, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nian, Y.-Y.; Chen, B.-K.; Wang, J.-J.; Zhong, W.-T.; Fang, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Q.-S.; Yan, D.-C. Transcriptome Analysis of Procambarus clarkii Infected with Infectious Hypodermal and Haematopoietic Necrosis Virus. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2020, 98, 766–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Jiang, Z.; Zhang, S.; Chen, Q.; Tong, S.; Liu, X.; Jiang, Q.; Yang, H.; Wei, W.; Zhang, X. Transcriptome Analysis and Immune-Related Genes Expression Reveals the Immune Responses of Macrobrachium rosenbergii Infected by Enterobacter cloacae. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2020, 101, 66–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Gu, J. Fastp: An Ultra-Fast All-in-One FASTQ Preprocessor. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, i884–i890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grabherr, M.G.; Haas, B.J.; Yassour, M.; Levin, J.Z.; Thompson, D.A.; Amit, I.; Adiconis, X.; Fan, L.; Raychowdhury, R.; Zeng, Q.; et al. Full-Length Transcriptome Assembly from RNA-Seq Data without a Reference Genome. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011, 29, 644–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated Estimation of Fold Change and Dispersion for RNA-Seq Data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashburner, M.; Ball, C.A.; Blake, J.A.; Botstein, D.; Butler, H.; Cherry, J.M.; Davis, A.P.; Dolinski, K.; Dwight, S.S.; Eppig, J.T.; et al. Gene Ontology: Tool for the Unification of Biology. Nat. Genet. 2000, 25, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanehisa, M.; Goto, S. KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000, 28, 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of Relative Gene Expression Data Using Real-Time Quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amparyup, P.; Charoensapsri, W.; Tassanakajon, A. Prophenoloxidase System and Its Role in Shrimp Immune Responses against Major Pathogens. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2013, 34, 990–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Salgado, J.L.; Pereyra, M.A.; Alpuche-Osorno, J.J.; Zenteno, E. Pattern Recognition Receptors in the Crustacean Immune Response against Bacterial Infections. Aquaculture 2021, 532, 735998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kar, N.S.; Ashraf, M.Z.; Valiyaveettil, M.; Podrez, E.A. Mapping and Characterization of the Binding Site for Specific Oxidized Phospholipids and Oxidized Low Density Lipoprotein of Scavenger Receptor CD36. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 8765–8771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverstein, R.L.; Febbraio, M. CD36, a Scavenger Receptor Involved in Immunity, Metabolism, Angiogenesis, and Behavior. Sci. Signal. 2009, 2, re3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, W.-J.; Li, D.-X.; Xu, Y.-H.; Xu, S.; Li, J.; Zhao, X.-F.; Wang, J.-X. Scavenger Receptor B Protects Shrimp from Bacteria by Enhancing Phagocytosis and Regulating Expression of Antimicrobial Peptides. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2015, 51, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willment, J.A.; Gordon, S.; Brown, G.D. Characterization of the Human β-Glucan Receptor and Its Alternatively Spliced Isoforms. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 43818–43823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiegertjes, G.F. Studies into β-Glucan Recognition in Fish Suggests a Key Role for the C-Type Lectin Pathway. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 280. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, X.; Liu, H.; Li, J.; Guo, K.; Han, W.; Dong, Y.; Wan, S.; Wang, X.; Jia, P.; Li, S.; et al. Heat Shock Factor 4 Regulates Lens Epithelial Cell Homeostasis by Working with Lysosome and Anti-Apoptosis Pathways. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2016, 79, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Zhuang, X.; Liao, M.; Huang, L.; Cui, Q.; Liu, C.; Dong, W.; Wang, F.; Liu, Y.; Wang, W. Transcriptome Analysis of Pacific White Shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) Hepatopancreas Challenged by Vibrio Alginolyticus Reveals Lipid Metabolic Disturbance. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2022, 123, 238–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, F.; Sun, C.; Li, S.; Hou, T.; Li, C. Therapeutic Effect and Immune Mechanism of Chitosan-Gentamicin Conjugate on Pacific White Shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) Infected with Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 269, 118334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, Y.; Sun, Y.; Yang, H.; Cao, Z.; Qin, Q.; Liu, C.; Guo, W. Functional Characterization of Cathepsin B and Its Role in the Antimicrobial Immune Responses in Golden Pompano (Trachinotus ovatus). Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2021, 123, 104128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsumoto, F.; Saitoh, S.; Fukui, R.; Kobayashi, T.; Tanimura, N.; Konno, K.; Kusumoto, Y.; Akashi-Takamura, S.; Miyake, K. Cathepsins Are Required for Toll-like Receptor 9 Responses. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2008, 367, 693–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Cattaneo, A.; Gobert, F.-X.; Müller, M.; Toscano, F.; Flores, M.; Lescure, A.; Del Nery, E.; Benaroch, P. Cleavage of Toll-like Receptor 3 by Cathepsins B and H Is Essential for Signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 9053–9058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Meng, X.; Kong, J.; Luo, K.; Luan, S.; Cao, B.; Liu, N.; Pang, J.; Shi, X. Molecular Cloning and Characterization of a Cathepsin B Gene from the Chinese Shrimp Fenneropenaeus chinensis. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2013, 35, 1604–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Q.; Zhang, X.-W.; Sun, Y.-D.; Sun, S.-S.; Zhou, J.; Wang, Z.-H.; Zhao, X.-F.; Wang, J.-X. Two Cysteine Proteinases Respond to Bacterial and WSSV Challenge in Chinese White Shrimp Fenneropenaeus chinensis. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2010, 29, 551–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velásquez, A.M.A.; Bartlett, P.J.; Linares, I.A.P.; Passalacqua, T.G.; Teodoro, D.D.L.; Imamura, K.B.; Virgilio, S.; Tosi, L.R.O.; Leite, A.D.L.; Buzalaf, M.A.R.; et al. New Insights into the Mechanism of Action of the Cyclopalladated Complex (CP2) in Leishmania: Calcium Dysregulation, Mitochondrial Dysfunction, and Cell Death. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2022, 66, e00767-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estrada-Cárdenas, P.; Camacho-Jiménez, L.; Peregrino-Uriarte, A.B.; Contreras-Vergara, C.A.; Hernandez-López, J.; Yepiz-Plascencia, G. P53 Knock-down and Hypoxia Affects Glutathione Peroxidase 4 Antioxidant Response in Hepatopancreas of the White Shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei. Biochimie 2022, 199, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Z.Q.; Tu, Y.Q.; Guo, P.Y.; He, W.; Jing, T.X.; Wang, J.J.; Wei, D.D. Antioxidant Enzymes and Heat Shock Protein Genes from Liposcelis bostrychophila Are Involved in Stress Defense upon Heat Shock. Insects 2020, 11, 839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heath, R.J.; Rock, C.O. A Conserved Histidine Is Essential for Glycerolipid Acyltransferase Catalysis. J. Bacteriol. 1998, 180, 1425–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abate, W.; Alrammah, H.; Kiernan, M.; Tonks, A.J.; Jackson, S.K. Lysophosphatidylcholine Acyltransferase 2 (LPCAT2) Co-Localises with TLR4 and Regulates Macrophage Inflammatory Gene Expression in Response to LPS. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 10355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gervais, O.; Renault, T.; Arzul, I. Molecular and Cellular Characterization of Apoptosis in Flat Oyster a Key Mechanisms at the Heart of Host-Parasite Interactions. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 12494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagata, S.; Tanaka, M. Programmed Cell Death and the Immune System. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2017, 17, 333–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaree, P.; Somboonwiwat, K. DnaJC16, the Molecular Chaperone, Is Implicated in Hemocyte Apoptosis and Facilitates of WSSV Infection in Shrimp. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2023, 137, 108770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chi, C.; Giri, S.S.; Yu, X.W.; Liu, Y.; Chen, K.K.; Liu, W.B.; Zhang, D.D.; Jiang, G.Z.; Li, X.F.; Gao, X.; et al. Lipid Metabolism, Immune and Apoptosis Transcriptomic Responses of the Hepatopancreas of Chinese Mitten Crab to the Exposure to Microcystin-LR. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022, 236, 113439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalpage, H.A.; Wan, J.; Morse, P.T.; Zurek, M.P.; Turner, A.A.; Khobeir, A.; Yazdi, N.; Hakim, L.; Liu, J.; Vaishnav, A.; et al. Cytochrome c Phosphorylation: Control of Mitochondrial Electron Transport Chain Flux and Apoptosis. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2020, 121, 105704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orrenius, S.; Zhivotovsky, B. Cardiolipin Oxidation Sets Cytochrome c Free. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2005, 1, 188–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, D.R.; Kroemer, G. The Pathophysiology of Mitochondrial Cell Death. Science 2004, 305, 626–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wartmann, T.; Mayerle, J.; Kähne, T.; Sahin–Tóth, M.; Ruthenbürger, M.; Matthias, R.; Kruse, A.; Reinheckel, T.; Peters, C.; Weiss, F.U.; et al. Cathepsin L Inactivates Human Trypsinogen, Whereas Cathepsin L-Deletion Reduces the Severity of Pancreatitis in Mice. Gastroenterology 2010, 138, 726–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Gene | Description | Primer Sequence (5′ to 3′) |

|---|---|---|

| ARSB | Arylsulfatase B-like | F-CGTCAGGTCCAACATCATCC |

| R-CTTCGTTCGCCAGTTCTTCC | ||

| CTSB | Cathepsin B | F-TAATACTGGGTGTGGTGTGTG |

| R-TACTTTGAGTCGGGATGAACG | ||

| CTL | C-type lectin | F-CAATACGACAGTCTGGGCTTC |

| R-CGCACCTCCATCAACATCAG | ||

| fth1-a | Ferritin | F-GAGACGATGTTGCTCTTCCTG |

| R-TCCACCACGGCTGTTCTG | ||

| CTSL | Cathepsin L | F-CGACTGCTAACGAAAGATGGG |

| R-CGGTAGTTGAAGGTTCTGGAAG | ||

| GST | Glutathione S-transferase | F-ATACTTAGCCAACCAGCAACAG |

| R-ACGAGGCAAACTTCTTGATAGC | ||

| Plg | Trypsin | F-AGGCACAGAACAGCGTATAAC |

| R-TCCAGCAACTTCACACATTCC | ||

| Sorb | Sorbitol dehydrogenase-like | F-TGCTTTCATTCGGCTGCTG |

| R-ACCTTCCTCTTGGCTGACG | ||

| EC18S | 18S ribosomal | F-ACCTATCCTGAGTGCCTAAGC |

| R-CTTCGTCCTTCCATCTTCTGC |

| Sample | Raw Reads | Clean Reads | Clean Bases | Q20 (%) | Q30 (%) | GC (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C-1 | 73,264,638 | 72,853,978 | 10,875,846,060 | 97.46 | 93.11 | 43.69 |

| C-2 | 69,762,456 | 69,449,584 | 10,367,317,033 | 97.76 | 93.63 | 43.91 |

| C-3 | 72,742,586 | 72,387,824 | 10,804,261,763 | 97.90 | 93.90 | 43.42 |

| T-1 | 69,891,130 | 69,590,130 | 10,380,228,574 | 97.81 | 93.75 | 43.70 |

| T-2 | 65,801,936 | 65,524,978 | 9,779,274,278 | 97.72 | 93.57 | 43.93 |

| T-3 | 68,803,894 | 68,501,780 | 10,219,018,610 | 97.61 | 93.34 | 43.90 |

| Category | Number |

|---|---|

| Transcriptome statistics | |

| Number of genes | 67,811 |

| Total size of transcripts (bp) | 61,403,893 |

| GC percentage (%) | 39.1699 |

| N50 number | 7792 |

| N50 length | 1977 |

| Max length | 35,367 |

| Min length | 201 |

| Average length | 905 |

| BUSCO Completeness | |

| Complete BUSCOs | 94.68% |

| single | 86.61% |

| Duplicated | 8.07% |

| Fragmented | 2.15% |

| Missing | 3.17% |

| Gene | Description | Flod Change |

|---|---|---|

| pattern recognition receptors | ||

| CTL | C-type lectin | 8.19 |

| SR-B | Scavenger receptor class B | 4.09 |

| Lysosome | ||

| CTSB | Cathepsin B | 3.88 |

| CTSA | Cathepsin A | 14.19 |

| LIPA | Lysosomal acid lipase | 4.55 |

| ARSB | Arylsulfatase B | 2.39 |

| Antioxidant system | ||

| GST | Glutathione S-transferase | −2.09 |

| Glycerophospholipid metabolism | ||

| MBOAT1 | lysophospholipid acyltransferase | −2.67 |

| AGPAT1 | lysophosphatidiate acyltransferase | −4.58 |

| Apoptosis | ||

| CASP2 | Caspase 2 | 2.44 |

| CASP7 | Caspase 7 | 2.74 |

| CYTC | Cytochrome c | 3.35 |

| CTSL | Cathepsin L | −4.03 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhao, R.; Li, H.; Wang, L.; Shi, W.; Wan, X. Transcriptome Analysis Reveals the Mechanisms of Organismal Response in Exopalaemon carinicauda Infected by Metschnikowia bicuspidata. Fishes 2025, 10, 628. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes10120628

Zhao R, Li H, Wang L, Shi W, Wan X. Transcriptome Analysis Reveals the Mechanisms of Organismal Response in Exopalaemon carinicauda Infected by Metschnikowia bicuspidata. Fishes. 2025; 10(12):628. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes10120628

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Ran, Hui Li, Libao Wang, Wenjun Shi, and Xihe Wan. 2025. "Transcriptome Analysis Reveals the Mechanisms of Organismal Response in Exopalaemon carinicauda Infected by Metschnikowia bicuspidata" Fishes 10, no. 12: 628. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes10120628

APA StyleZhao, R., Li, H., Wang, L., Shi, W., & Wan, X. (2025). Transcriptome Analysis Reveals the Mechanisms of Organismal Response in Exopalaemon carinicauda Infected by Metschnikowia bicuspidata. Fishes, 10(12), 628. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes10120628