Impact of Effective Probiotic Microorganisms (EPMs) on Growth Performance, Hematobiochemical Panel, Immuno-Antioxidant Status, and Gut Cultivable Microbiota in Striped Catfish (Pangasianodon hypophthalmus)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

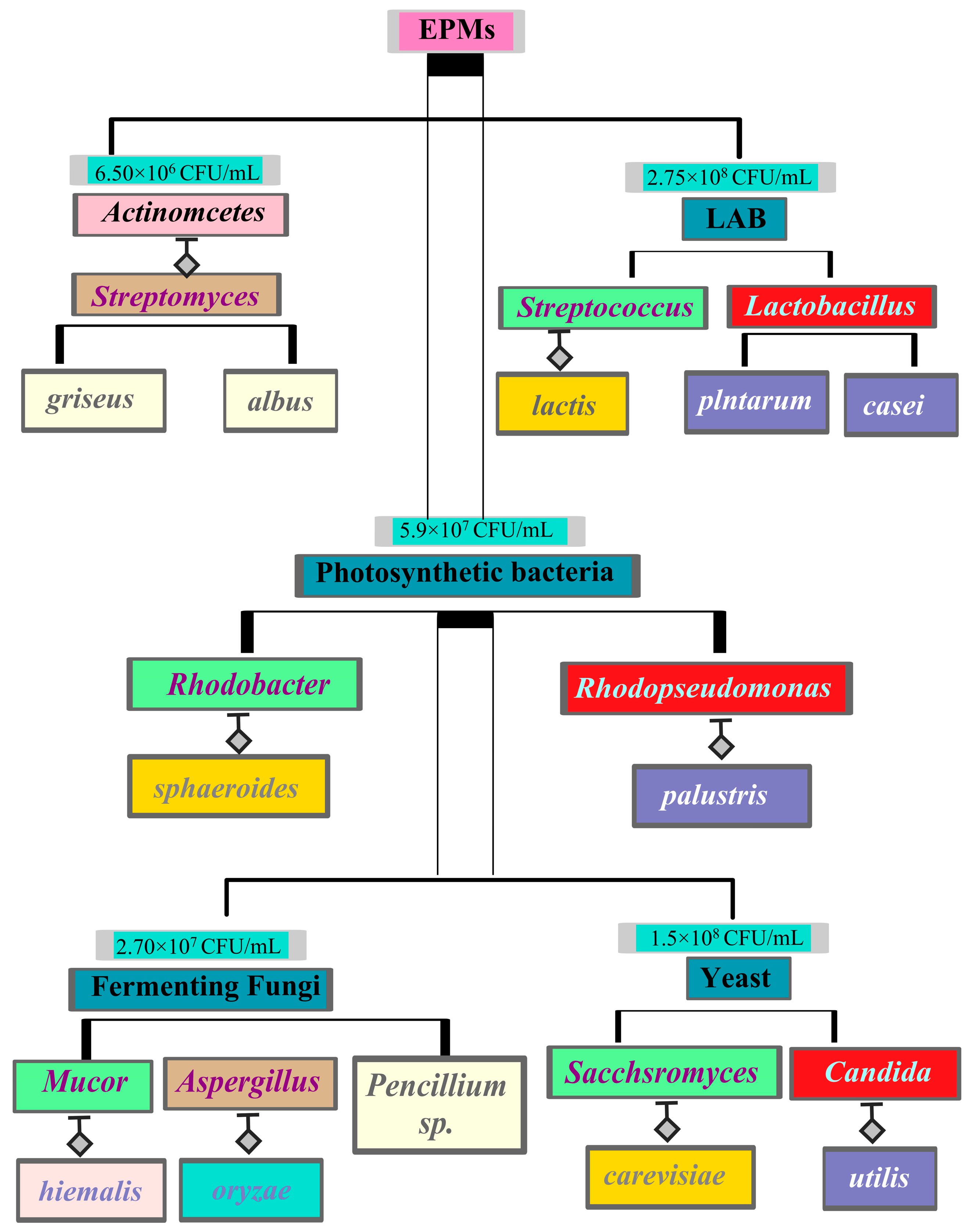

2.1. Source of Fish, Basal Diet, and Probiotics

2.2. Design of Experiments and Fish Husbandry

2.3. Feeding Protocol and Water Quality

2.4. Sample Collection and Processing

2.5. Rates of Survival, Growth Performance, Utilization of Feed, and Somatic Indices

2.6. Total-Body Proximate Composition

2.7. Serum Growth Hormone Assessment

2.8. Digestive Enzyme Efficiencies

2.9. Routine Hemogram Variable Assessment

2.10. Assessment of Liver and Kidney Functions and Lipid Profile

2.11. Assessment of Hepatic Antioxidant Status and Lipid Peroxidation

2.12. Cellular and Humoral Immune Response Assays

2.12.1. Phagocytic Activities in Whole Blood

2.12.2. Oxidative Burst Reaction (NBT)

2.12.3. Serum Lysozyme Activity

2.13. Assessment of Intestinal Microbial Compositional Differences

2.14. Resistance to Bacterial Infection

2.15. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Growth Performance, Feed Efficiency, and Survival Rates

3.2. Body Proximate Composition and Organ Biometric Indicators

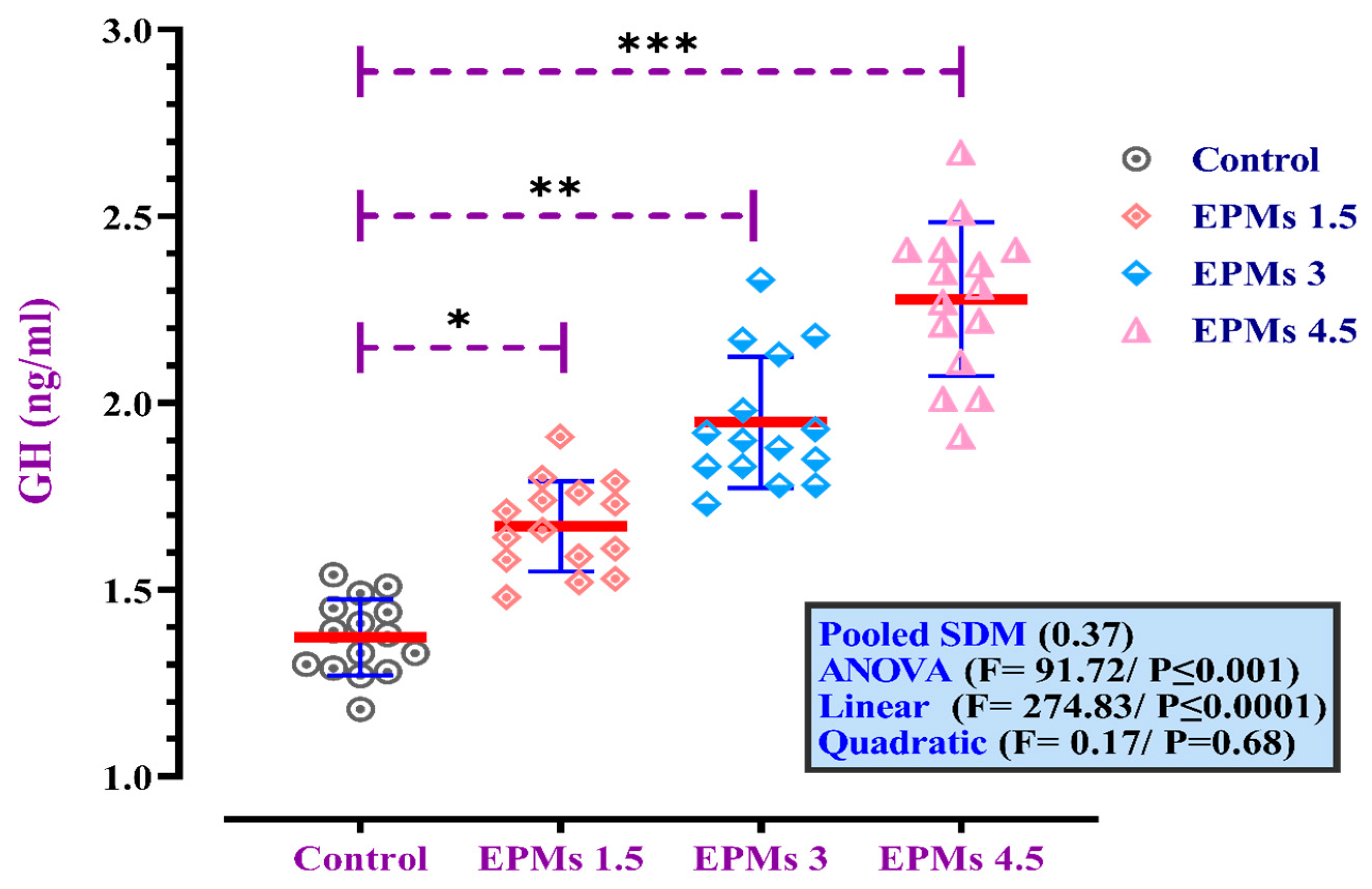

3.3. Serum Growth Hormone Levels

3.4. Digestive Enzyme Efficiency

3.5. Routine Hemogram Findings

3.6. Serum Biochemical Metabolites and Lipid Profile

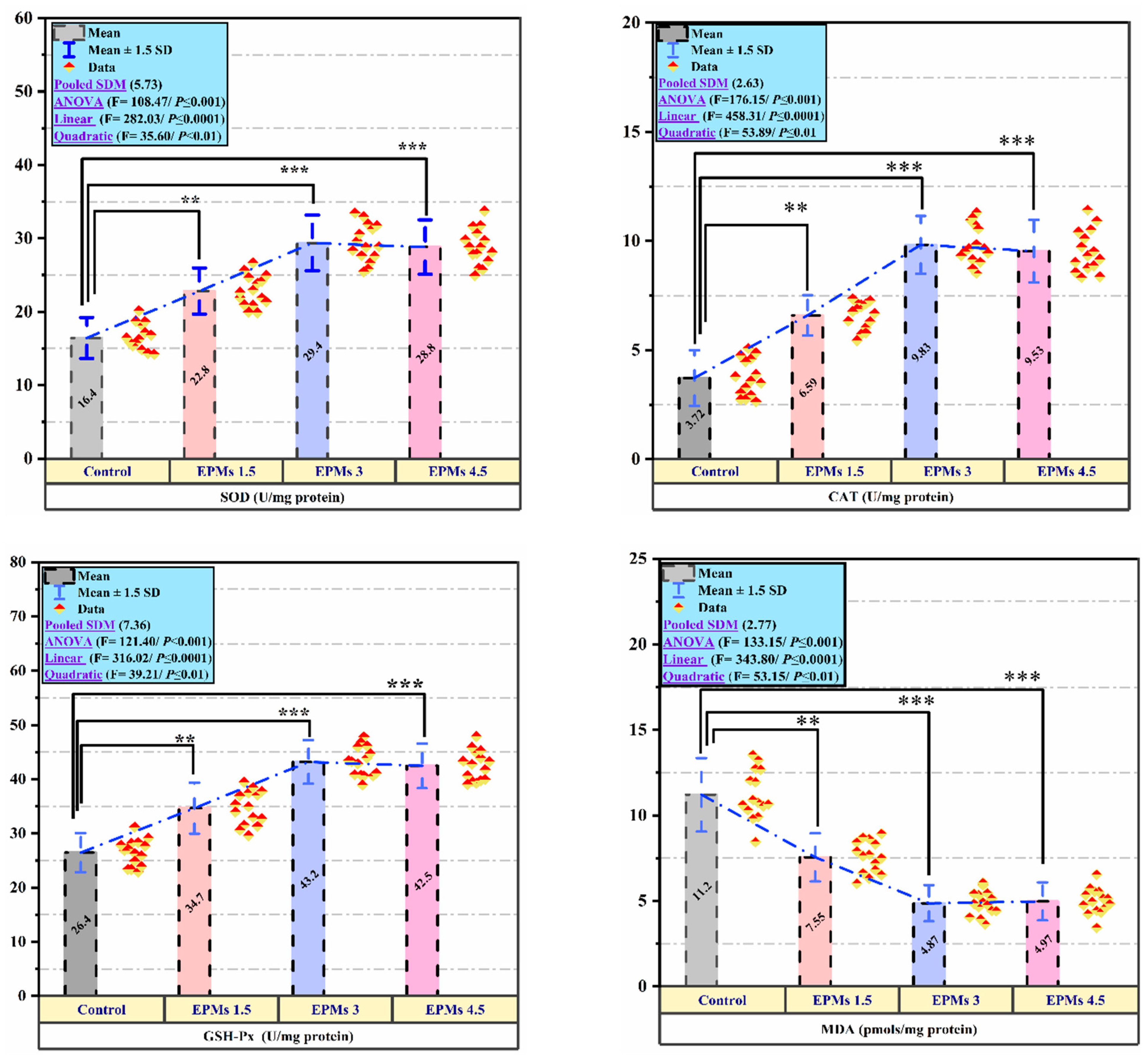

3.7. Hepatic Reduction/Oxidation Balance

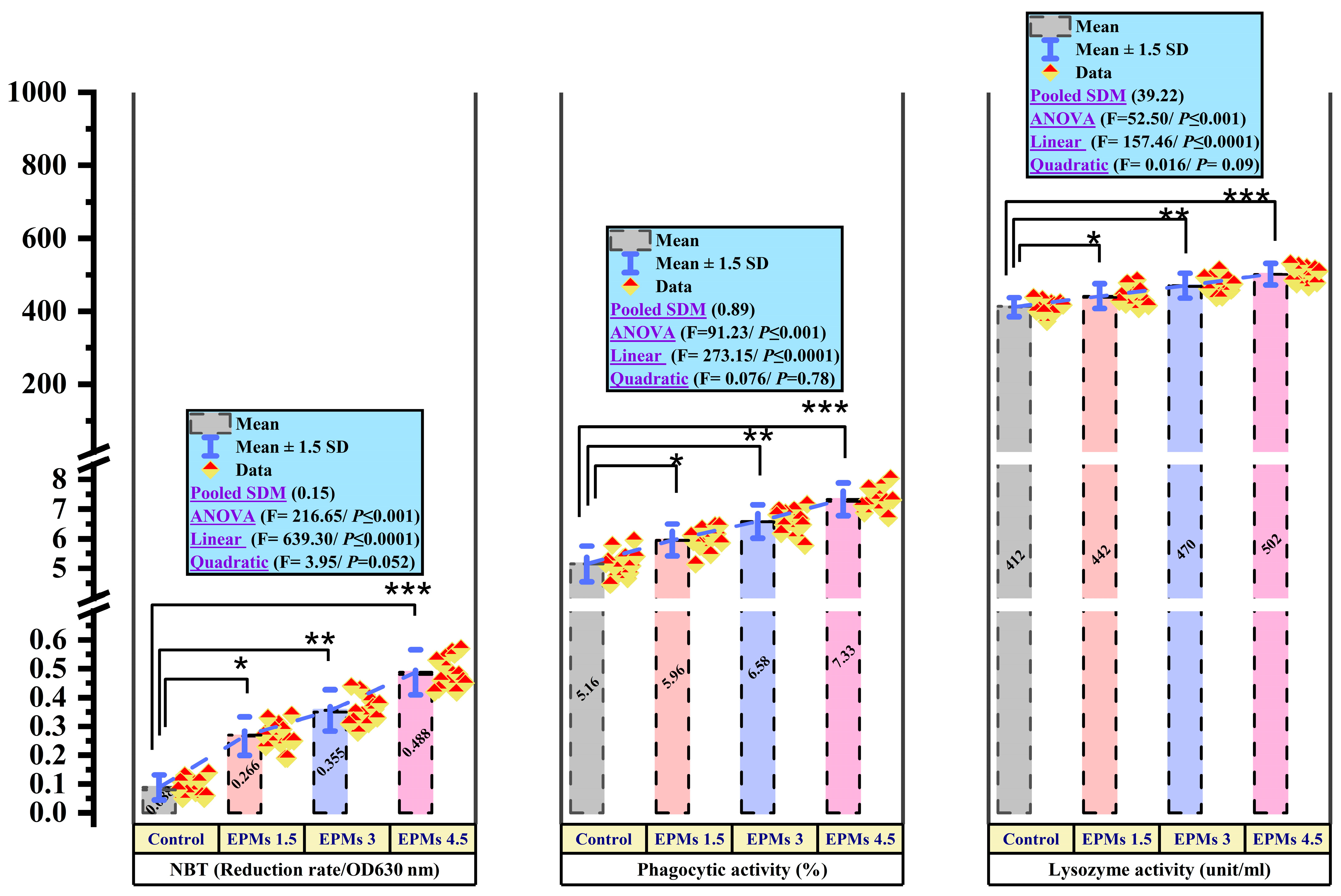

3.8. Cellular and Humoral Immune Response

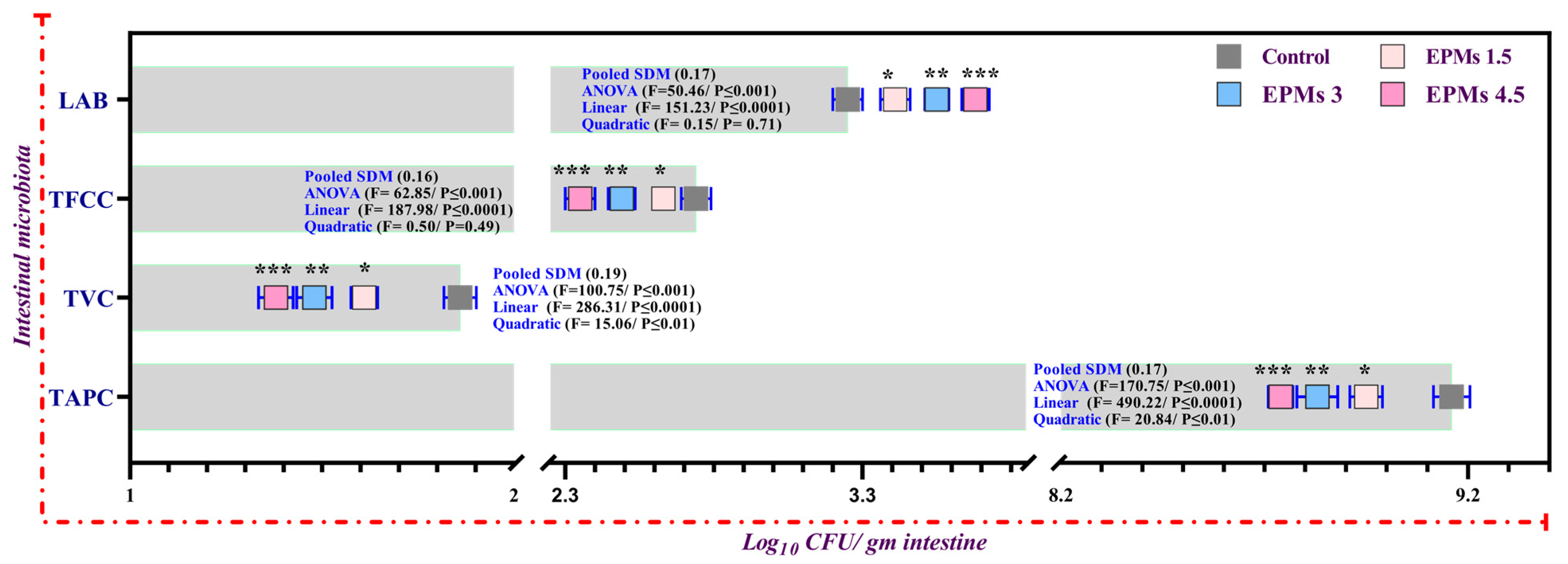

3.9. Intestinal Microbial Diversity

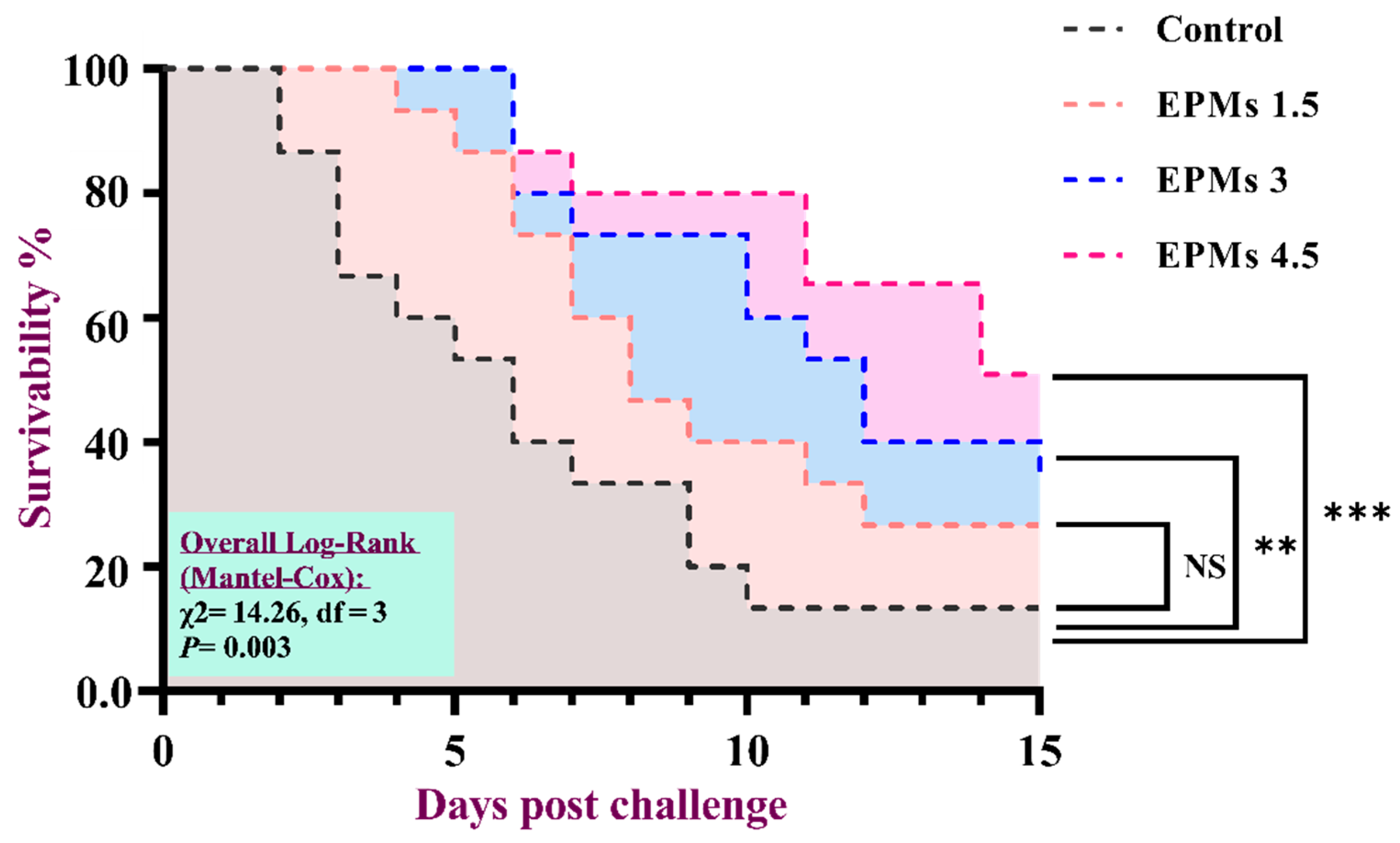

3.10. Resistance to Infection

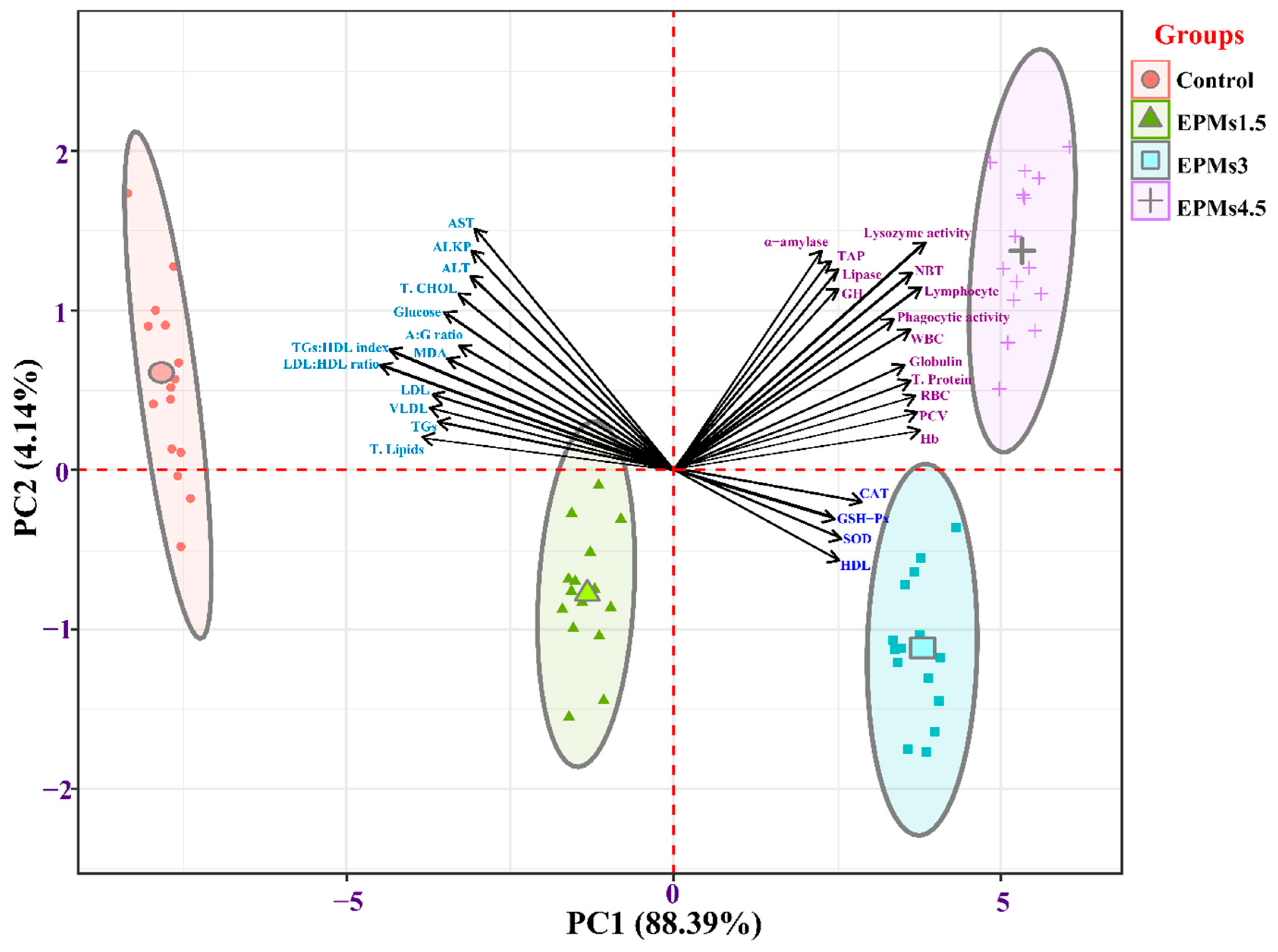

3.11. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) on the Significantly Enhanced Hemato-Biochemical, Hepatic Redox Status, Digestive Enzymes, and Immunity Response Parameters

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ottinger, M.; Clauss, K.; Kuenzer, C. Opportunities and challenges for the estimation of aquaculture production based on earth observation data. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, W.; Wang, W.; de Souza, M.C. The sustainable development goals and the economic contribution of fisheries and aquaculture. FAO Aquac. Newsl. 2019, 60, 51–52. [Google Scholar]

- Kaleem, O.; Sabi, A.-F.B.S. Overview of aquaculture systems in Egypt and Nigeria, prospects, potentials, and constraints. Aquac. Fish. 2021, 6, 535–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feidi, I. Will the new large-scale aquaculture projects make Egypt self sufficient in fish supplies? Mediterr. Fish. Aquac. Res. 2018, 1, 31–41. [Google Scholar]

- Mansour, A.T.; Allam, B.W.; Srour, T.M.; Omar, E.A.; Nour, A.A.M.; Khalil, H.S. The feasibility of monoculture and polyculture of striped catfish and Nile tilapia in different proportions and their effects on growth performance, productivity, and financial revenue. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noseda, B.; Islam, M.T.; Eriksson, M.; Heyndrickx, M.; De Reu, K.; Van Langenhove, H.; Devlieghere, F. Microbiological spoilage of vacuum and modified atmosphere packaged Vietnamese Pangasius hypophthalmus fillets. Food Microbiol. 2012, 30, 408–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K. Assessing the Sustainability and Food Security Implications of Introduced (Sauvage, 1878) and (Burchell, 1822) Into Indian Aquaculture: A OneHealth Perspective. Rev. Aquac. 2025, 17, e12990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd-Elaziz, R.A. Striped catfish (Pangasianodon hypophthalmus) with special emphasis on its suitability to the Egyptian aquaculture: An overview. Egyp. J. Anim. Health 2024, 4, 148–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamad, N.F.A.; Daud, H.H.M.; Ruhil Hayati, H.; Manaf, S.R.; Zin, A.A.M.; Fauzi, N.N.F.N.M. Identification of Fatty Acid Profile of Clariid Catfish Species: Clarias gariepinus (Burchell, 1822), Clarias macrocephalus (Gunther, 1864) and their Hybrids. Adv. Anim. Vet. Sci. 2022, 10, 712–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaki, M.A.A.; Khalil, H.S.; Allam, B.W.; Khalil, R.H.; Basuini, M.F.E.; Nour, A.E.-A.M.; Labib, E.M.H.; Elkholy, I.S.E.; Verdegem, M.; Abdel-Latif, H.M.R. Assessment of zootechnical parameters, intestinal digestive enzymes, haemato-immune responses, and hepatic antioxidant status of Pangasianodon hypophthalmus fingerlings reared under different stocking densities. Aquac. Int. 2023, 31, 2451–2474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Latif, H.M.; Chaklader, M.R.; Shukry, M.; Ahmed, H.A.; Khallaf, M.A. A multispecies probiotic modulates growth, digestive enzymes, immunity, hepatic antioxidant activity, and disease resistance of Pangasianodon hypophthalmus fingerlings. Aquaculture 2023, 563, 738948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naiel, M.A.E.; Farag, M.R.; Gewida, A.G.A.; Elnakeeb, M.A.; Amer, M.S.; Alagawany, M. Using lactic acid bacteria as an immunostimulants in cultured shrimp with special reference to Lactobacillus spp. Aquac. Int. 2021, 29, 219–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelhamid, A.F.; Ayoub, H.F.; Abd El-Gawad, E.A.; Abdelghany, M.F.; Abdel-Tawwab, M. Potential effects of dietary seaweeds mixture on the growth performance, antioxidant status, immunity response, and resistance of striped catfish (Pangasianodon hypophthalmus) against Aeromonas hydrophila infection. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2021, 119, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartie, K.L.; Ngô, T.P.H.; Bekaert, M.; Hoang Oanh, D.T.; Hoare, R.; Adams, A.; Desbois, A.P. Aeromonas hydrophila ST251 and Aeromonas dhakensis are major emerging pathogens of striped catfish in Vietnam. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1067235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamun, A.-A.; Nasren, S.; Rathore, S.S.; Mahbub Alam, M. Histopathological Analysis of Striped Catfish, Pangasianodon hypophthalmus (Sauvage, 1878) Spontaneously Infected with Aeromonas hydrophila. Jordan J. Biol. Sci 2022, 15, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Rasmussen-Ivey, C.R.; Moen, F.S.; Fernández-Bravo, A.; Lamy, B.; Beaz-Hidalgo, R.; Khan, C.D.; Escarpulli, G.C.; Yasin, I.S.M.; Figueras, M.J.; et al. A Global Survey of Hypervirulent Aeromonas hydrophila (vAh) Identified vAh Strains in the Lower Mekong River Basin and Diverse Opportunistic Pathogens from Farmed Fish and Other Environmental Sources. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e03705–e03722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limbu, S.M.; Chen, L.Q.; Zhang, M.L.; Du, Z.Y. A global analysis on the systemic effects of antibiotics in cultured fish and their potential human health risk: A review. Rev. Aquac. 2021, 13, 1015–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, L.T.; Nguyen, L.H.T.; Pham, V.T.; Bui, H.T.T. Usage and knowledge of antibiotics of fish farmers in small-scale freshwater aquaculture in the Red River Delta, Vietnam. Aquac. Res. 2021, 52, 3580–3590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Latif, H.M.R.; Shukry, M.; Noreldin, A.E.; Ahmed, H.A.; El-Bahrawy, A.; Ghetas, H.A.; Khalifa, E. Milk thistle (Silybum marianum) extract improves growth, immunity, serum biochemical indices, antioxidant state, hepatic histoarchitecture, and intestinal histomorphometry of striped catfish, Pangasianodon hypophthalmus. Aquaculture 2023, 562, 738761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanjani, M.H.; Mozanzadeh, M.T.; Gisbert, E.; Hoseinifar, S.H. Probiotics, prebiotics, and synbiotics in shrimp aquaculture: Their effects on growth performance, immune responses, and gut microbiome. Aquac. Rep. 2024, 38, 102362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Status, H.; Toutou, M.M.; Ali, A.; Soliman, A.; Mahrous, M.; Farrag, S. Effect of Probiotic and Synbiotic Food Supplementation on Growth Effect of Probiotic and Synbiotic Food Supplementation on Growth Performance and Healthy Status of Grass Carp, Ctenopharyngodon idella (Valenciennes, 1844). Int. J. Ecotoxicol. Ecobiol. 2016, 1, 111–117. Available online: https://www.sciencepublishinggroup.com/article/10.11648/j.ijee.20160103.18 (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- Rohani, M.F.; Islam, S.M.M.; Hossain, M.K.; Ferdous, Z.; Siddik, M.A.B.; Nuruzzaman, M.; Padeniya, U.; Brown, C.; Shahjahan, M. Probiotics, prebiotics and synbiotics improved the functionality of aquafeed: Upgrading growth, reproduction, immunity and disease resistance in fish. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2022, 120, 569–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanveer, A.; Khan, N.; Fatima, M.; Ali, W.; Nazir, S.; Bano, S.; Asghar, M. Effect of multi-strain probiotics on the growth, hematological profile, blood biochemistry, antioxidant capacity, and physiological responses of Clarias batrachus fingerlings. Aquac. Int. 2024, 32, 1817–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liaqat, R.; Fatima, S.; Komal, W.; Minahal, Q.; Kanwal, Z.; Suleman, M.; Carter, C.G. Effects of Bacillus subtilis as a single strain probiotic on growth, disease resistance and immune response of striped catfish (Pangasius hypophthalmus). PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0294949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puvanasundram, P.; Chong, C.M.; Sabri, S.; Yusoff, M.S.; Karim, M. Multi-strain probiotics: Functions, effectiveness and formulations for aquaculture applications. Aquac. Rep. 2021, 21, 100905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todorov, S.D.; Lima, J.M.S.; Bucheli, J.E.V.; Popov, I.V.; Tiwari, S.K.; Chikindas, M.L. Probiotics for Aquaculture: Hope, Truth, and Reality. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2024, 16, 2007–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghanei-Motlagh, R.; Mohammadian, T.; Gharibi, D.; Khosravi, M.; Mahmoudi, E.; Zarea, M.; El-Matbouli, M.; Menanteau-Ledouble, S. Quorum quenching probiotics modulated digestive enzymes activity, growth performance, gut microflora, haemato-biochemical parameters and resistance against Vibrio harveyi in Asian seabass (Lates calcarifer). Aquaculture 2021, 531, 735874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano-Lozano, J.A.; Villamil Diaz, L.M.; Melo Bolivar, J.F.; Hume, M.E.; Ruiz Pardo, R.Y. Probiotics in tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) culture: Potential probiotic Lactococcus lactis culture conditions. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2022, 133, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amit; Pandey, A.; Tyagi, A.; Khairnar, S.O. Oral feed-based administration of Lactobacillus plantarum enhances growth, haematological and immunological responses in Cyprinus carpio. Emerg. Anim. Species 2022, 3, 100003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chugh, B.; Kamal-Eldin, A. Bioactive compounds produced by probiotics in food products. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2020, 32, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, G.; Chen, X.; Feng, Y.; Yu, Z.; Lu, Q.; Li, M.; Ye, Z.; Lin, H.; Yu, W.; Shu, H. Effects of dietary multi-strain probiotics on growth performance, antioxidant status, immune response, and intestinal microbiota of hybrid groupers (Epinephelus fuscoguttatus♀ × E. Lanceolatus♂). Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, K.; Harikrishnan, R.; Mukhopadhyay, A.; Ringø, E. Fungi and Actinobacteria: Alternative Probiotics for Sustainable Aquaculture. Fishes 2023, 8, 575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd El-Naby, A.S.; El Asely, A.M.; Hussein, M.N.; Khattaby, A.E.-R.A.; Sabry, E.A.; Abdelsalam, M.; Samir, F. Effects of dietary fermented Saccharomyces cerevisiae extract (Hilyses) supplementation on growth, hematology, immunity, antioxidants, and intestinal health in Nile tilapia. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 12583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balami, S.; Paudel, K.; Shrestha, N. A review: Use of probiotics in striped catfish larvae culture. Int. J. Fish. aquat. Stud. 2022, 10, 41–49. [Google Scholar]

- Abdel-Aziz, M.; Bessat, M.; Fadel, A.; Elblehi, S. Responses of dietary supplementation of probiotic effective microorganisms (EMs) in Oreochromis niloticus on growth, hematological, intestinal histopathological, and antiparasitic activities. Aquac. Int. 2020, 28, 947–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Kady, A.A.; Magouz, F.I.; Mahmoud, S.A.; Abdel-Rahim, M.M. The effects of some commercial probiotics as water additive on water quality, fish performance, blood biochemical parameters, expression of growth and immune-related genes, and histology of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Aquaculture 2022, 546, 737249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadir, A.A.; Mohamed, M.A.R.; Ayman, M.L.; Basem, S.A.; Ghada, M.S. The Applicability of Activated Carbon, Natural Zeolites, and Probiotics (EM®) and Its Effects on Ammonia Removal Efficiency and Fry Performance of European Seabass Dicentrarchus labrax. J. Aquac. Res. Dev. 2016, 7, 459–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jwher, D.M.; Al-Sarhan, M. Evaluation the role of effective microorganisms (EM) on the growth performance and health parameters on common carp (Cyprinus carpio L.). J. Appl. Vet. Sci. 2022, 7, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesyk, I.; Puzan, N.; Nikitin, A. EM–Multifunctional Microbiological Preparation; AIJR Publisher: Utraula, Uttar Pradesh, India, 2020; pp. 159–160. Available online: https://books.aijr.org/index.php/press/catalog/download/93/26/535-1?inline=1 (accessed on 21 September 2025).

- Rice, E.W.; Baird, R.B.; Eaton, A.D.; Clesceri, L.S. Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater; American Public Health Association: Washington, DC, USA; American Water Works Association: Denver, CO, USA; Water Environment Federation: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Oladipupo, A.A.; Kelly, A.M.; Davis, D.A.; Bruce, T.J. Investigation of dietary exogenous protease and humic substance on growth, disease resistance to Flavobacterium covae and immune responses in juvenile channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus). J. Fish Dis. 2023, 5, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyle, S.D.; Durborow, R.M.; Tidwell, J.H. Anesthetics in Aquaculture; Southern Regional Aquaculture Center: Stoneville, MS, USA, 2004; Volume 3900, p. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Ashry, A.M.; Habiba, M.M.; Abdel-Warith, A.-w.A.; Younis, E.M.; Davies, S.J.; Elnakeeb, M.A.; Abdelghany, M.F.; El-Zayat, A.M.; El-Sebaey, A.M. Dietary effect of powdered herbal seeds on zootechnical performance, hemato-biochemical indices, immunological status, and intestinal microbiota of European sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax). Aquac. Rep. 2024, 36, 102074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiex, N.; Novotny, L.; Crawford, A. Determination of ash in animal feed: AOAC official method 942.05 revisited. J. AOAC Int. 2012, 95, 1392–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, B.; Singh, A.K. Immunological and physiological validation of enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for growth hormone of the Asian catfish, Clarias batrachus. Fish Physiol. Biochem. 2005, 31, 289–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, M.M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976, 72, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morishita, Y.; Iinuma, Y.; Nakashima, N.; Majima, K.; Mizuguchi, K.; Kawamura, Y. Total and Pancreatic Amylase Measured with 2-Chloro-4-nitrophenyl-4-O-β-d-galactopyranosylmaltoside. Clin. Chem. 2000, 46, 928–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panteghini, M.; Bonora, R.; Pagani, F. Measurement of pancreatic lipase activity in serum by a kinetic colorimetric assay using a new chromogenic substrate. Ann. Clin. Biochem. 2001, 38, 365–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, N.; Firth, K.; Wang AnPing, W.A.; Burka, J.; Johnson, S. Changes in hydrolytic enzyme activities of naive Atlantic salmon, Salmo salar, skin mucus due to infection with the salmon louse, Lepeophtheirus salmonis, and cortisol implantation. Dis. Aquat. Organ. 2000, 41, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walsh, C.J. Elasmobranch hematology: Identification of cell types and practical applications. In Elasmobranch Husbandry Manual: Captive Care of Sharks, Rays, and their Relatives; Mark Smith, D.W., Thoney, D., Hueter, E., Eds.; Ohio Biological Survey, Inc.: Hilliard, OH, USA, 2004; pp. 307–323. [Google Scholar]

- Wells, R.M.; Pankhurst, N.W. Evaluation of simple instruments for the measurement of blood glucose and lactate, and plasma protein as stress indicators in fish. J. World Aquac. Soc. 1999, 30, 276–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirois, M. Hemoglobin, PCV, and Erythrocyte Indices. In Laboratory Procedures for Veterinary Technicians; Sirois, M., Ed.; Elsevier Inc.: Maryland, MO, USA, 2014; pp. 51–56. [Google Scholar]

- Friedewald, W.T.; Levy, R.I.; Fredrickson, D.S. Estimation of the Concentration of Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol in Plasma, Without Use of the Preparative Ultracentrifuge. Clin. Chem. 1972, 18, 499–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peskin, A.V.; Winterbourn, C.C. Assay of superoxide dismutase activity in a plate assay using WST-1. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2017, 103, 188–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamza, T.A.; Hadwan, M.H. New spectrophotometric method for the assessment of catalase enzyme activity in biological tissues. Curr. Anal. Chem. 2020, 16, 1054–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sattar, A.A.; Matin, A.A.; Hadwan, M.H.; Hadwan, A.M.; Mohammed, R.M. Rapid and effective protocol to measure glutathione peroxidase activity. Bull. Natl. Res. Cent. 2024, 48, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchiyama, M.; Mihara, M. Determination of malonaldehyde precursor in tissues by thiobarbituric acid test. Anal. Biochem. 1978, 86, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, D.P.; Siwicki, A.K. Basic Hematology and Serology for Fish Health Programs; Shariff, M., Arthur, J.R., Subasinghe, J.P., Eds.; Fish Health Section, Asian Fisheries Society: Manila, Phillipines, 1995; p. 18. [Google Scholar]

- Ulzanah, N.; Wahjuningrum, D.; Widanarni, W.; Kusumaningtyas, E. Peptide hydrolysate from fish skin collagen to prevent and treat Aeromonas hydrophila infection in Oreochromis niloticus. Vet. Res. Commun. 2023, 47, 487–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurani, F.S.; Sukenda, S.; Nuryati, S. Maternal immunity of tilapia broodstock vaccinated with polyvalent vaccine and resistance of their offspring against Streptococcus agalactiae. Aquac. Res. 2020, 51, 1513–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parry, R.M.; Chandan, R.C.; Shahani, K.M. A Rapid and Sensitive Assay of Muramidase. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 1965, 119, 384–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, E.E.; El Basuini, M.F.; Ashry, A.M.; Habiba, M.M.; Teiba, I.I.; El-Rayes, T.K.; Khattab, A.A.A.; El-Hais, A.M.; Shahin, S.A.; El-Ratel, I.T.; et al. Effect of dietary sage (Salvia officinalis L.) on the growth performance, feed efficacy, blood indices, non-specific immunity, and intestinal microbiota of European sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax). Aquac. Rep. 2023, 28, 101460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagliavia, M.; Salamone, M.; Bennici, C.; Quatrini, P.; Cuttitta, A. A modified culture medium for improved isolation of marine vibrios. MicrobiologyOpen 2019, 8, e00835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamarinou, C.S.; Papadopoulou, O.S.; Doulgeraki, A.I.; Tassou, C.C.; Galanis, A.; Chorianopoulos, N.G.; Argyri, A.A. Mapping the key technological and functional characteristics of indigenous lactic acid bacteria isolated from Greek traditional dairy products. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, K.C.; Patel, R. Systems for Identification of Bacteria and Fungi. In Manual of Clinical Microbiology; Wiley Online Library: London, UK, 2015; pp. 29–43. [Google Scholar]

- Hassanin, M.E.; El-Murr, A.; El-Khattib, A.R.; Abdelwarith, A.A.; Younis, E.M.; Metwally, M.M.M.; Ismail, S.H.; Davies, S.J.; Abdel Rahman, A.N.; Ibrahim, R.E. Nano-Bacillus amyloliquefaciens as a dietary intervention in nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus): Effects on resistance to Aeromonas hydrophila challenge, immune-antioxidant responses, digestive/absorptive capacity, and growth. Heliyon 2024, 10, e40418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Son, M.A.M.; Nofal, M.I.; Abdel-Latif, H.M.R. Co-infection of Aeromonas hydrophila and Vibrio parahaemolyticus isolated from diseased farmed striped mullet (Mugil cephalus) in Manzala, Egypt—A case report. Aquaculture 2021, 530, 735738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-Y. Statistical notes for clinical researchers: Post-hoc multiple comparisons. Restor. Dent. Endod. 2015, 40, 172–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukherjee, A.; Chandra, G.; Ghosh, K. Single or conjoint application of autochthonous Bacillus strains as potential probiotics: Effects on growth, feed utilization, immunity and disease resistance in Rohu, Labeo rohita (Hamilton). Aquaculture 2019, 512, 734302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arciuch-Rutkowska, M.; Nowosad, J.; Łuczyński, M.K.; Jasiński, S.; Kucharczyk, D. Effects of the diet enrichment with β-glucan, sodium salt of butyric acid and vitamins on growth parameters and the profile of the gut microbiome of juvenile African catfish (Clarias gariepinus). Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2024, 310, 115941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerreiro, I.; Oliva-Teles, A.; Enes, P. The Effect of Probiotics and Prebiotics on Feed Intake in Cultured Fish. Rev. Aquac. 2025, 17, e12982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, J.A.R.; Alves, L.L.; Barros, F.A.L.; Cordeiro, C.A.M.; Meneses, J.O.; Santos, T.B.R.; Santos, C.C.M.; Paixão, P.E.G.; Filho, R.M.N.; Martins, M.L.; et al. Comparative effects of using a single strain probiotic and multi-strain probiotic on the productive performance and disease resistance in Oreochromis niloticus. Aquaculture 2022, 550, 737855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, H.; Tariq, A.; Jurrat, H.; Musaddaq, R.; Liaqat, I.; Muhammad, N. Actinomycetes: Ultimate Potential Source of Bioactive Compounds Production: Actinomycetes for Bioactive Compounds Production. Futurist. Biotechnol. 2024, 4, 02–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onomu, A.J.; Okuthe, G.E. The Application of Fungi and Their Secondary Metabolites in Aquaculture. J. Fungi 2024, 10, 711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eissa, E.-S.H.; Okon, E.M.; Abdel-Warith, A.-W.A.; Younis, E.M.; Munir, M.B.; Eissa, H.A.; Ghanem, S.F.; Mahboub, H.H.; Abd Elghany, N.A.; Dighiesh, H.S.; et al. Influence of a mixture of oligosaccharides and β-glucan on growth performance, feed efficacy, body composition, biochemical indices, combating Streptococcus iniae infection, and gene expression of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Aquac. Int. 2024, 32, 5353–5371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Vidakovic, A.; Hjertner, B.; Krikigianni, E.; Karnaouri, A.; Christakopoulos, P.; Rova, U.; Dicksved, J.; Baruah, K.; Lundh, T. Effects of dietary supplementation of lignocellulose-derived cello-oligosaccharides on growth performance, antioxidant capacity, immune response, and intestinal microbiota in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Aquaculture 2024, 578, 740002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omidi, A.H.; Adel, M.; Bahri, A.H.; Yahyavi, M.; Mohammadizadeh, F.; Impellitteri, F.; Faggio, C. Synergistic dietary influence of fermented red grape vinegar and Lactobacillus acidophilus on growth performance, carcass composition, and intestinal morphology of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Aquac. Rep. 2024, 36, 102122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadangin, J.; Lee, J.-H.; Jeon, C.-Y.; Lee, E.-S.; Moon, J.-S.; Park, S.-J.; Hur, S.-W.; Jang, W.-J.; Choi, Y.-H. Effects of dietary supplementation of Bacillus, β-glucooligosaccharide and their synbiotic on the growth, digestion, immunity, and gut microbiota profile of abalone, Haliotis discus hannai. Aquac. Rep. 2024, 35, 102027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdous, Z.; Fariha, F.; Jahan, N.; Shahriar, S.I.M.; Hossain, M.K.; Uddin, M.J.; Shahjahan, M. Influence of Multistrain Probiotics on Growth, Hematology, Gut and Liver Morphometry, and GH and IGFs Genes Expression in Rohu (Labeo Rohita) Fry. Aquac. Res. 2025, 2025, 5892568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- do Carmo Alves, A.P.; Orlando, T.M.; de Oliveira, I.M.; Libeck, L.T.; Silva, K.K.S.; Rodrigues, R.A.F.; da Silva Cerozi, B.; Cyrino, J.E.P. Synbiotic microcapsules of Bacillus subtilis and oat β-glucan on the growth, microbiota, and immunity of Nile tilapia. Aquac. Int. 2024, 32, 3869–3888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatnagar, A.; Mann, D. The Synergic Effect of Gut-Derived Probiotic Bacillus cereus SL1 And Ocimum sanctum on Growth, Intestinal Histopathology, Innate Immunity, and Expression of Enzymatic Antioxidant Genes in Fish, Cirrhinus mrigala (Hamilton, 1822). Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2025, 17, 271–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahriar, F.; Ibnasina, A.H.E.A.; Uddin, N.; Munny, F.J.; Hussain, M.A.; Jang, W.J.; Lee, J.M.; Lee, E.-W.; Hasan, M.T.; Kawsar, M.A. Effects of Commercial Probiotics on the Growth, Hematology, Immunity, and Resistance to Aeromonas hydrophila Challenge in Climbing Perch, Anabas testudineus. Aquac. Res. 2024, 2024, 3901035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutriana, A.; Akter, M.N.; Hashim, R.; Nor, S.A.M. Effectiveness of single and combined use of selected dietary probiotic and prebiotics on growth and intestinal conditions of striped catfish (Pangasianodon hypophthalmus, Sauvage, 1978) juvenile. Aquac. Int. 2021, 29, 2769–2791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zannat, M.M.; Rohani, M.F.; Jeba, R.-O.Z.; Shahjahan, M. Multi-Species Probiotics Ameliorate Salinity-Induced Growth Retardation in Striped Catfish Pangasianodon hypophthalmus. Int. J. Environ. Res. 2024, 18, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobi, N.; Malaikozhundan, B.; Sekar, V.; Shanthi, S.; Vaseeharan, B.; Jayakumar, R.; Khudus Nazar, A. GFP tagged Vibrio parahaemolyticus Dahv2 infection and the protective effects of the probiotic Bacillus licheniformis Dahb1 on the growth, immune and antioxidant responses in Pangasius hypophthalmus. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2016, 52, 230–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Han, D.; Zhang, T.; Li, D.; Tang, R. Ammonium induces oxidative stress, endoplasmic reticulum stress, and apoptosis of hepatocytes in the liver cell line of grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella). Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 30, 27092–27102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassaan, M.S.; El-Sayed, A.M.I.; Mohammady, E.Y.; Zaki, M.A.A.; Elkhyat, M.M.; Jarmołowicz, S.; El-Haroun, E.R. Eubiotic effect of a dietary potassium diformate (KDF) and probiotic (Lactobacillus acidophilus) on growth, hemato-biochemical indices, antioxidant status and intestinal functional topography of cultured Nile tilapia Oreochromis niloticus fed diet free fishmeal. Aquaculture 2021, 533, 736147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alak, G.; Kotan, R.; Uçar, A.; Parlak, V.; Atamanalp, M. Pre-probiotic effects of different bacterial species in aquaculture: Behavioral, hematological and oxidative stress responses. Oceanol. Hydrobiol. Stud. 2022, 51, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringø, E.; Harikrishnan, R.; Soltani, M.; Ghosh, K. The Effect of Gut Microbiota and Probiotics on Metabolism in Fish and Shrimp. Animals 2022, 12, 3016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, T.; Wang, J. Oxidative stress tolerance and antioxidant capacity of lactic acid bacteria as probiotic: A systematic review. Gut Microbes 2020, 12, 1801944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwashita, M.K.P.; Nakandakare, I.B.; Terhune, J.S.; Wood, T.; Ranzani-Paiva, M.J.T. Dietary supplementation with Bacillus subtilis, Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Aspergillus oryzae enhance immunity and disease resistance against Aeromonas hydrophila and Streptococcus iniae infection in juvenile tilapia Oreochromis niloticus. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2015, 43, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddik, M.A.B.; Foysal, M.J.; Fotedar, R.; Francis, D.S.; Gupta, S.K. Probiotic yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae coupled with Lactobacillus casei modulates physiological performance and promotes gut microbiota in juvenile barramundi, Lates calcarifer. Aquaculture 2022, 546, 737346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shawky, A.; Abd El-Razek, I.M.; El-Halawany, R.S.; Zaineldin, A.I.; Amer, A.A.; Gewaily, M.S.; Dawood, M.A.O. Dietary effect of heat-inactivated Bacillus subtilis on the growth performance, blood biochemistry, immunity, and antioxidative response of striped catfish (Pangasianodon hypophthalmus). Aquaculture 2023, 575, 739751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Wang, J.; Guan, Y.; Xing, S.; Liang, X.; Xue, M.; Wang, J.; Chang, Y.; Leclercq, E. Cottonseed protein concentrate as fishmeal alternative for largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides) supplemented a yeast-based paraprobiotic: Effects on growth performance, gut health and microbiome. Aquaculture 2022, 551, 737898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Wang, G.; Xiong, Z.; Xia, Y.; Song, X.; Zhang, H.; Wu, Y.; Ai, L. Probiotics interact with lipids metabolism and affect gut health. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 917043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basto-Silva, C.; Enes, P.; Oliva-Teles, A.; Capilla, E.; Guerreiro, I. Dietary protein/carbohydrate ratio and feeding frequency affect feed utilization, intermediary metabolism, and economic efficiency of gilthead seabream (Sparus aurata) juveniles. Aquaculture 2022, 554, 738182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Wang, Y.; Li, N.; Li, T.; Guan, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, P.; Li, Z.; Liu, H. Effects of dietary carbohydrate levels on growth performance, feed utilization, liver histology and intestinal microflora of juvenile tiger puffer, Takifugu rubripes. Aquac. Rep. 2024, 36, 102035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Becerril, M.; Alamillo, E.; Angulo, C. Probiotic and immunomodulatory activity of marine yeast Yarrowia lipolytica strains and response against Vibrio parahaemolyticus in fish. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2021, 13, 1292–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Maravilla, E.; Parra, M.; Maisey, K.; Vargas, R.A.; Cabezas-Cruz, A.; Gonzalez, A.; Tello, M.; Bermúdez-Humarán, L.G. Importance of Probiotics in Fish Aquaculture: Towards the Identification and Design of Novel Probiotics. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diab, A.M.; El-Rahman, F.A.; Khalfallah, M.M.; Salah, A.S.; Farrag, F.; Darwish, S.I.; Shukry, M. Evaluating the Impact of Dietary and Water-Based Probiotics on Tilapia Health and Resistance to Aeromonas hydrophila. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2024. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12602-024-10415-z (accessed on 28 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- Opiyo, M.A.; Jumbe, J.; Ngugi, C.C.; Charo-Karisa, H. Different levels of probiotics affect growth, survival and body composition of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) cultured in low input ponds. Sci. Afr. 2019, 4, e00103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Xu, S.; Jiang, C.; Peng, X.; Zhou, X.; Sun, Q.; Zhu, L.; Xie, X.; Zhuang, X. Improvement of the growth performance, intestinal health, and water quality in juvenile crucian carp (Carassius auratus gibelio) biofortified system with the bacteria-microalgae association. Aquaculture 2023, 562, 738848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra Segaran, T.; Azra, M.N.; Piah, R.M.; Lananan, F.; Téllez-Isaías, G.; Gao, H.; Torsabo, D.; Kari, Z.A.; Noordin, N.M. Catfishes: A global review of the literature. Heliyon 2023, 9, e20081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Fisheries and Aquaculture Department. Cultured Aquatic Species Information Programme: Clarias gariepinus. Available online: http://www.fao.org/fishery/culturedspecies/Clarias_gariepinus/en (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- Akter, M.N.; Hashim, R.; Sutriana, A.; Nor, S.A.M.; Janaranjani, M. Lactobacillus acidophilus supplementation improves the innate immune response and disease resistance of Striped catfish (Pangasianodon hypophthalmus Sauvage, 1878) Juveniles against Aeromonas hydrophila. Trends Sci. 2023, 20, 4932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Items | Experimental Diets 1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | EPMs Levels | |||

| 1.5 | 3 | 4.5 | ||

| Feed Ingredients (g kg−1) | ||||

| Fish meal 2 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Soybean meal 2 | 220 | 220 | 220 | 220 |

| Gluten 2 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 |

| Rich bran | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Wheat bran | 120 | 120 | 120 | 120 |

| Wheat | 120 | 120 | 120 | 120 |

| Corn | 240 | 225 | 210 | 195 |

| Fish oil | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 |

| Vitamin premix 3 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| Mineral premix 4 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| Dicalcium Phosphate | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| EPM levels | 0 | 15 | 30 | 45 |

| Total | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 |

| Proximate analysis: DM Basis (g kg−1) | ||||

| Dry matter (DM) | 89.52 | 89.51 | 89.53 | 89.55 |

| Crude protein (CP) | 30.08 | 30.04 | 30.01 | 30.07 |

| Ether extract (EE) | 6.89 | 6.70 | 6.58 | 6.45 |

| Crude fiber (CF) | 5.13 | 5.10 | 5.11 | 5.13 |

| Ash | 6.62 | 6.54 | 6.47 | 6.90 |

| NFE 5 | 51.28 | 51.62 | 51.83 | 51.45 |

| Parameters | Control | EPMs Levels % DM (g/kg) | Orthogonal Contrast | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.5 | 3 | 4.5 | Pooled SDM | ANOVA | Linear | Quadratic | ||

| (F Value) p Value | ||||||||

| ITL (cm) | 10.49 | 10.37 NS | 10.62 NS | 10.57 NS | 0.34 | (0.245) =0.863 | (0.258) =0.625 | (0.028) =0.872 |

| FTL (cm) | 21.54 | 25.57 * | 30.01 ** | 32.66 *** | 4.46 | (285.64) ≤0.001 | (848.45) ≤0.0001 | (5.58) =0.06 |

| IBW (g) | 10.04 | 10.02 NS | 10.06 NS | 10.08 NS | 0.61 | (0.004) =1.00 | (0.007) =0.94 | (0.002) =0.962 |

| FBW (g) | 87.71 | 130.29 * | 172.76 ** | 207.83 *** | 47.26 | (377.28 ≤0.001 | (1129.51) ≤0.0001 | (1.97) =0.20 |

| WG (g) | 77.67 | 120.27 ** | 162.71 ** | 197.76 *** | 47.24 | (376.22) ≤0.001 | (1126.33) ≤0.0001 | (1.98) =0.22 |

| ADG (g) | 0.863 | 1.34 * | 1.81 ** | 2.20 *** | 0.53 | (380.05) ≤0.001 | (1137.05) ≤0.0001 | (1.97) =0.21 |

| SGR (%day−1) | 1.93 | 2.13 * | 2.26 ** | 2.34 *** | 0.16 | (269.04) ≤0.001 | (781.07) ≤0.0001 | (25.93) <0.05 |

| RGR (%) | 7.75 | 12.04 * | 16.32 ** | 19.63 *** | 4.70 | (63.61) ≤0.001 | (190.16) ≤0.0001 | (0.576) =0.47 |

| FCR | 1.890 | 1.270 ** | 0.953 *** | 0.81 *** | 0.44 | (68.16) ≤0.001 | (187.69) ≤0.0001 | (16.53) <0.05 |

| PER | 2.13 | 3.15 * | 4.21 ** | 4.97 *** | 1.13 | (161.41) ≤0.001 | (481.89) ≤0.0001 | (1.733) =0.22 |

| SR (%) | 80.00 | 88.00 * | 93.33 ** | 98.67 *** | 30.05 | (5.504) ≤0.001 | (16.328) ≤0.0001 | (0.154) =0.70 |

| Intake (g kg−1 day−1) | ||||||||

| TFI | 146.05 | 152.78 NS | 154.83 NS | 159.22 NS | 6.72 | (3.19) =0.084 | (9.17) =0.06 | (0.15) =0.714 |

| DM | 131.45 | 137.50 NS | 139.35 NS | 143.29 NS | 6.05 | (3.21) =0.082 | (9.17) =0.06 | (0.13) =0.618 |

| PI | 36.52 | 38.19 NS | 38.71 NS | 39.81 NS | 1.68 | (3.19) =0.084 | (9.15) =0.06 | (0.144) =0.714 |

| LI | 9.93 | 10.39 NS | 10.53 NS | 10.83 NS | 0.46 | (33.22) =0.073 | (9.17) =0.06 | (0.17) =0.68 |

| Parameters | Control | EPMs Levels % DM (g/kg) | Orthogonal Contrast | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.5 | 3 | 4.5 | Pooled SDM | ANOVA | Linear | Quadratic | ||

| (F Value) p Value | ||||||||

| Indices (%) | ||||||||

| HSI (%) | 2.65 | 2.70 NS | 2.57 NS | 2.67 NS | 0.23 | (0.13) =0.94 | (0.94) =0.27 | (0.01) =0.87 |

| VSI (%) | 9.99 | 12.48 ** | 13.98 *** | 14.09 *** | 1.76 | (71.58) ≤0.001 | (186.94) ≤0.001 | (27.66) <0.05 |

| K (%) | 0.88 | 0.78 ** | 0.64 *** | 0.59 *** | 0.12 | (59.00) ≤0.001 | (171.16) ≤0.001 | (2.53) =0.15 |

| RGL (cm) | 1.49 | 1.89 ** | 2.53 *** | 2.51 *** | 0.48 | (30.24) ≤0.001 | (80.74) ≤0.001 | (5.31) =0.07 |

| Chemical composition | ||||||||

| Dry matter (g) | 25.16 | 26.88 * | 27.60 * | 27.63 * | 1.27 | (5.45) <0.05 | (13.24) ≤0.01 | (3.08) =0.12 |

| Protein % | 59.86 | 65.82 * | 66.20 * | 67.23 * | 3.98 | (3.60) <0.05 | (8.20) <0.05 | (1.97) =0.20 |

| Lipid % | 23.33 | 15.05 * | 14.13 * | 11.90 * | 5.16 | (6.78) ≤0.05 | (21.79) ≤0.001 | (3.22) =0.11 |

| Ash % | 16.81 | 19.13 NS | 19.67 NS | 20.86 NS | 2.22 | (2.45) =0.138 | (6.84) ≤0.05 | (0.27) =0.62 |

| Enzymes (U × mg tissue protein−1) | Control | EPMs Levels % DM (g/kg) | Orthogonal Contrast | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.5 | 3 | 4.5 | Pooled SDM | ANOVA | Linear | Quadratic | ||

| (F Value) p Value | ||||||||

| TAP | 19.31 | 24.45 * | 29.59 ** | 34.62 *** | 6.12 | (51.23) ≤0.001 | (153.68) ≤0.001 | (0.04) =0.95 |

| Lipase | 44.36 | 51.34 * | 59.42 ** | 66.38 *** | 8.90 | (48.19) ≤0.001 | (144.44) ≤0.001 | (0.01) =1.00 |

| α-amylase | 0.66 | 0.78 * | 0.87 ** | 0.98 *** | 0.12 | (44.55) ≤0.001 | (133.47) ≤0.001 | (0.03) =0.87 |

| Parameters | Control | EPMs Levels % DM (g/kg) | Orthogonal Contrast | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.5 | 3 | 4.5 | Pooled SEM | ANOVA | Linear | Quadratic | ||

| (F Value) p Value | ||||||||

| RBC (106 µL−1) | 1.77 | 2.67 * | 3.49 ** | 4.36 *** | 1.03 | (50.91) ≤0.001 | (152.69) ≤0.001 | (0.94) =0.92 |

| Hb (g dL−1) | 8.62 | 11.86 * | 14.10 ** | 15.97 *** | 3.12 | (99.74) ≤0.001 | (290.75) ≤0.001 | (7.49) <0.05 |

| PCV (%) | 20.00 | 31.33 * | 38.00 ** | 45.00 *** | 9.77 | (83.12) ≤0.001 | (245.00) ≤0.001 | (3.45) =0.10 |

| MCV (fL) | 113.67 | 119.22 NS | 109.36 NS | 103.37 NS | 13.63 | (0.66) =0.60 | (1.22) =0.30 | (0.49) =0.51 |

| MCH (pg) | 45.48 | 44.79 NS | 40.27 NS | 36.75 NS | 4.91 | (3.54) =0.07 | (9.94) ≤0.01 | (0.42) =0.53 |

| MCHC (%) | 40.13 | 37.92 NS | 36.96 NS | 35.60 NS | 2.86 | (1.55 =0.27 | (4.53) =0.07 | (0.08) =0.79 |

| WBC (103 µL−1) | 26.30 | 43.15 *** | 39.36 *** | 44.96 *** | 7.34 | (59.18) ≤0.001 | (175.53) ≤0.001 | (1.19) =0.31 |

| Neutrophil (103 µL−1) | 6.94 | 9.37 NS | 9.18 NS | 9.31 NS | 2.18 | (0.84) =0.51 | (1.44) =0.26 | (0.80) =0.40 |

| Lymphocyte (103 µL−1) | 18.75 | 24.15 * | 29.55 ** | 35.02 *** | 6.53 | (40.73) ≤0.001 | (122.20) ≤0.001 | (0.001) =0.98 |

| Monocyte (103 µL−1) | 0.48 | 0.51 NS | 0.50 NS | 0.53 NS | 0.08 | (0.09 =0.96 | (0.24 =0.64 | (0.01) =0.92 |

| Eosinophil (103 µL−1) | 0.13 | 0.12 NS | 0.14 NS | 0.11 NS | 0.03 | (0.29) =0.83 | (0.53) =0.49 | (0.04) =0.84 |

| Parameters | Control | EPM Levels % DM (g/kg) | Orthogonal Contrast | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.5 | 3 | 4.5 | Pooled SEM | ANOVA | Linear | Quadratic | ||

| (F Value) p Value | ||||||||

| Indicators of liver and kidney function | ||||||||

| ALT (U L−1) | 26.91 | 20.08 ** | 19.49 ** | 18.89 ** | 3.52 | (8.39) ≤0.01 | (18.49) ≤0.001 | (5.56) <0.05 |

| AST (U L−1) | 91.67 | 82.89 ** | 79.27 ** | 81.26 ** | 5.40 | (13.77) ≤0.01 | (27.96) ≤0.001 | (13.33) =0.07 |

| ALKP (U L−1) | 63.17 | 54.78 ** | 52.57 ** | 53.73 ** | 4.86 | (11.01) ≤0.01 | (22.04) ≤0.001 | (10.82) ≤0.01 |

| T. Protein (g dL−1) | 2.85 | 3.65 * | 4.83 ** | 5.11 *** | 0.90 | (40.73) ≤0.001 | (121.06) ≤0.001 | (0.05) =0.83 |

| Albumin (g dL−1) | 1.02 | 0.93 NS | 0.95 NS | 1.05 NS | 0.10 | (1.08) =0.41 | (0.30) =0.61 | (2.93) =0.13 |

| Globulin (g dL−1) | 1.84 | 2.72 * | 3.42 ** | 4.05 *** | 0.90 | (30.72) ≤0.001 | (91.60) ≤0.001 | (0.54) =0.48 |

| A: G ratio | 0.58 | 0.35 * | 0.28 * | 0.26 * | 0.16 | (6.20) <0.05 | (15.18) ≤0.01 | (3.24) =0.11 |

| T. Bilirubin (mg dL−1) | 0.58 | 0.54 NS | 0.51 NS | 0.57 NS | 0.04 | (3.59) =0.07 | (0.56) =0.48 | (8.52) <0.05 |

| Urea (mg dL−1) | 10.02 | 9.60 NS | 9.81 NS | 9.54 NS | 0.54 | (0.39) =0.77 | (0.60) =0.46 | (0.04) =0.85 |

| Creatinine (mg dL−1) | 0.38 | 0.40 NS | 0.43 NS | 0.41 NS | 0.02 | (0.68) =0.59 | (0.41) =0.85 | (0.50) =0.33 |

| Glucose (mg dL−1) | 94.81 | 82.08 ** | 74.06 *** | 75.33 *** | 8.93 | (47.42) ≤0.001 | (115.61) ≤0.001 | (26.11) ≤0.01 |

| Lipid profile | ||||||||

| T. Lipids (mg dL−1) | 932.23 | 916.25 ** | 879.14 *** | 883.96 *** | 23.82 | (84.56) ≤0.001 | (214.58) ≤0.001 | (14.84) ≤0.01 |

| T. CHOL (mg dL−1) | 217.65 | 192.67 ** | 174.33 *** | 178.33 *** | 19.31 | (15.86) ≤0.001 | (36.36) ≤0.001 | (8.75) <0.05 |

| TGs (mg dL−1) | 165.97 | 149.25 ** | 130.39 *** | 131.69 *** | 15.67 | (41.69) ≤0.001 | (109.41) ≤0.001 | (11.99) ≤0.01 |

| VLDL (mg dL−1) | 33.19 | 29.85 ** | 26.08 *** | 26.34 *** | 3.13 | (41.78) ≤0.001 | (109.68) ≤0.001 | (12.10) ≤0.01 |

| LDL (mg dL−1) | 118.21 | 106.61 ** | 95.22 *** | 94.25 *** | 10.47 | (46.28) ≤0.001 | (126.64) ≤0.001 | (10.31) ≤0.01 |

| HDL (mg dL−1) | 59.99 | 66.52 ** | 75.92 *** | 73.23 *** | 6.78 | (26.28) ≤0.001 | (62.14) ≤0.001 | (10.95) ≤0.01 |

| TG: HDL index | 2.77 | 2.25 ** | 1.72 *** | 1.79 *** | 0.44 | (84.88) ≤0.001 | (215.39) ≤0.001 | (32.46) ≤0.01 |

| LDL: HDL ratio | 1.97 | 1.60 ** | 1.26 *** | 1.29 *** | 0.31 | (50.810) ≤0.001 | (131.85) ≤0.001 | (17.81) ≤0.01 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Elnakeeb, M.A.; Ashry, A.M.; El-Zayat, A.M.; Abdel-Warith, A.W.A.-M.; Habiba, M.M.; Younis, E.M.I.; Davies, S.J.; Ibrahim, I.M.; Elzhraa, F.; El-Sebaey, A.M. Impact of Effective Probiotic Microorganisms (EPMs) on Growth Performance, Hematobiochemical Panel, Immuno-Antioxidant Status, and Gut Cultivable Microbiota in Striped Catfish (Pangasianodon hypophthalmus). Fishes 2025, 10, 573. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes10110573

Elnakeeb MA, Ashry AM, El-Zayat AM, Abdel-Warith AWA-M, Habiba MM, Younis EMI, Davies SJ, Ibrahim IM, Elzhraa F, El-Sebaey AM. Impact of Effective Probiotic Microorganisms (EPMs) on Growth Performance, Hematobiochemical Panel, Immuno-Antioxidant Status, and Gut Cultivable Microbiota in Striped Catfish (Pangasianodon hypophthalmus). Fishes. 2025; 10(11):573. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes10110573

Chicago/Turabian StyleElnakeeb, Mahmoud Abdullah, Ahmed Mohamed Ashry, Ahmed Mohamed El-Zayat, Abdel Wahab Abdel-Moez Abdel-Warith, Mahmoud Mohamed Habiba, Elsayed Mohamed Ibrahim Younis, Simon John Davies, Ibrahim Mohamed Ibrahim, Fatma Elzhraa, and Ahmed Mohammed El-Sebaey. 2025. "Impact of Effective Probiotic Microorganisms (EPMs) on Growth Performance, Hematobiochemical Panel, Immuno-Antioxidant Status, and Gut Cultivable Microbiota in Striped Catfish (Pangasianodon hypophthalmus)" Fishes 10, no. 11: 573. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes10110573

APA StyleElnakeeb, M. A., Ashry, A. M., El-Zayat, A. M., Abdel-Warith, A. W. A.-M., Habiba, M. M., Younis, E. M. I., Davies, S. J., Ibrahim, I. M., Elzhraa, F., & El-Sebaey, A. M. (2025). Impact of Effective Probiotic Microorganisms (EPMs) on Growth Performance, Hematobiochemical Panel, Immuno-Antioxidant Status, and Gut Cultivable Microbiota in Striped Catfish (Pangasianodon hypophthalmus). Fishes, 10(11), 573. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes10110573