1. Background

Between the years 1850 and 1930, Sweden experienced a mass exodus of people fleeing poverty and economic suffering. Approximately one-fifth of the population, 1.5 million people, sought a new life in the US, particularly around Minnesota. Swedish folk historian Vilhelm Moberg documented this diaspora in a series of novels. “The Emigrants” (1949) captured the ethos of many Swedes who could see themselves in this history (

Alexis 1966). In order to memorialize, and perhaps romanticize this mass migration, the communities of Karlsham, Sweden and Lindstrom, Minnesota both placed commemorative statues of the two main characters, Karl Oskar and Kristina, in their town squares. This couple is presented as members of the farming class, pointing to the reality that rural people were hit hardest by economic issues and by industrialization. Many, if not most, of the emigrants had been farmers or workers in factories or mills (

Lowell 1987;

Bohlin and Eurenius 2009).

Labour for working class Swedes remained challenging into the 20th century. After a general strike in 1909, the three Swedish employers’ associations joined forces orchestrating a worker lock-out. This caused such hardship for workers that by 1910 the unions had lost one-third of their members. The employers could then suppress any organized labor unrest until 1917 (

Thomsen 1970). The 1920s brought social transition, the strengthening of agriculture and the development of national corporations. The Swedes had one foot in an old world and one in a new. Despite the strong upward surge in economic development, many rural Swedes still faced archaic conditions, considerable poverty and a harsh working environment. People moved from the countryside to the towns and started to work in industry, including steel and paper mills. Differences between poor and rich were immense and class struggles continued to put stress on the labor market and on the lives of the working people. In agricultural sectors, women worked alongside men as well as being responsible for the gendered domestic work of childcare and home management (

Lowell 1987). They worked the double shift faced by many women living in patriarchal countries (Ibid, 1987). Due partially to the Swedish women’s and trade union movements, Sweden developed a reputation for having the most relative gender equality. However, today some scholars challenge the “myth of gender equality in Sweden” (

Martinsson et al., 20161) and write about The “Nordic Paradox” (

Gracia and Merlo 2016), where levels of gender inequality may be relatively low, compared to other countries globally but there are still major differences in participation and earning levels in the private sector and women are still expected to take the main responsibility for raising children (

Söderström 2019;

Wall 2014). But now, onto our story.

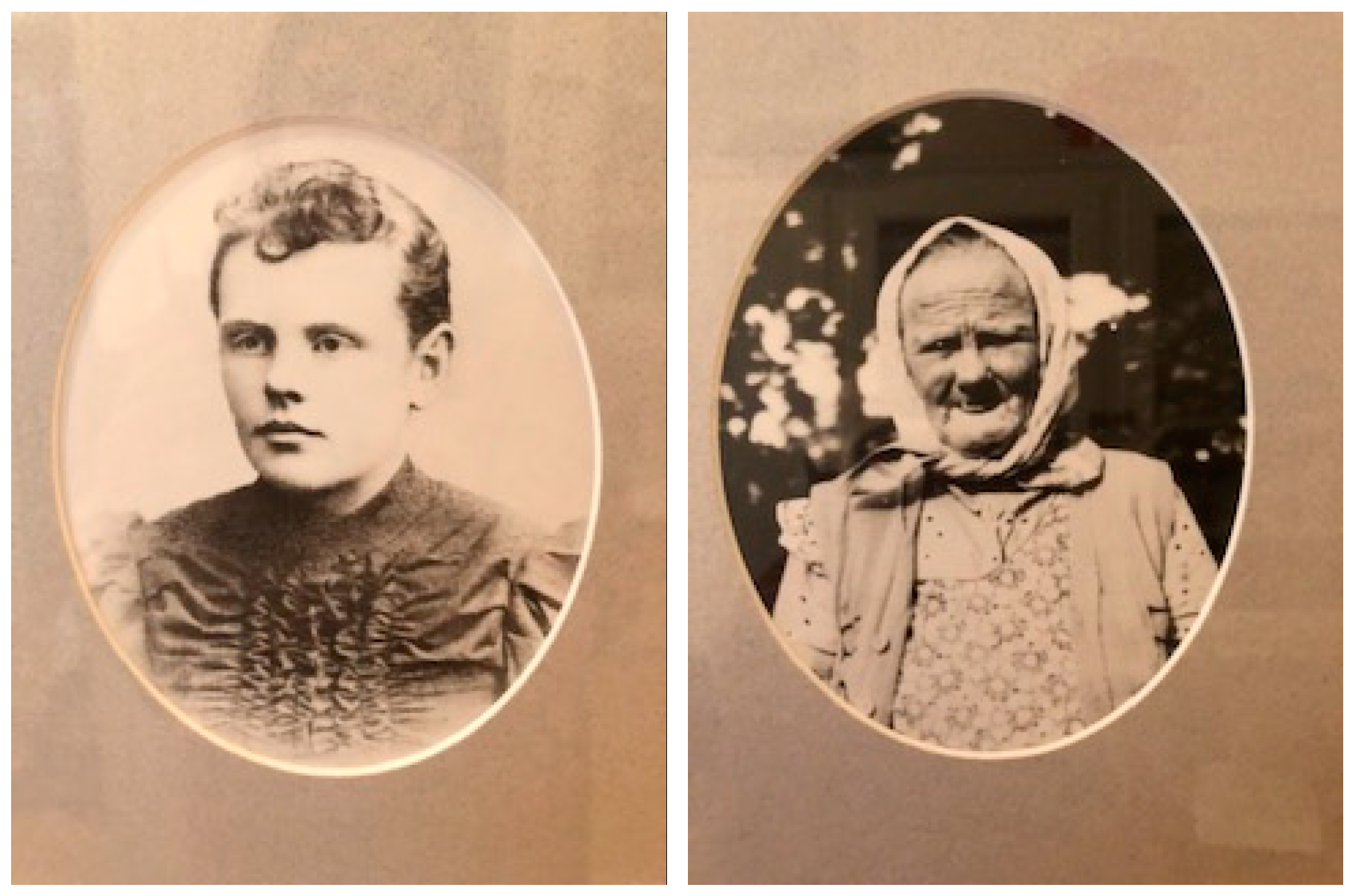

2. Ellen-Maria Ek

During the era hitherto described, our great-grandmother Ellen-Maria lived in Småland in Sweden’s south. She was the ninth of nine children. On 18 July 1876 in Kävsjö, her mother, Ingeborg Stina Petersdotter, gave birth to Ellen-Maria, the ninth of nine children, at the age of 47. Ellen-Maria’s father was Emanuel Svenson. This child was not blessed with a life of ease. At the age of one, her mother died of tuberculosis, which was rampant in Sweden at the time, leaving her to be cared for by her siblings, for all intents and purposes. At the age of ten, Ellen-Maria was required to work, and therefore, took a job as a “vallflick”—a shepherdess. One can imagine that this type of activity could place a young girl in a fair amount of danger, having to work with herds in isolation without adult supervision. In relation to her life story, as a woman, a mother, and a worker, only a patchwork of stories remain. This article represents an attempt to piece together the various short and fragmented narratives held by family members about Ellen-Maria’s life.

In 1897, at the age of 21, Ellen-Maria moved to Timsfors with her first son. There, she married stonemason Karl Oskar Ek, who became her first husband, on 2 May 1898. It was no doubt considered scandalous for an unwed woman to give birth at that time. Karl Oskar turned out to be a violent man who caused her much torment and distress. Today one might say she was traumatized by male violence. We might also consider the many things she had to do to resist the harm and degradation of an abusive man, including soliciting the kind of help from family and friends that would not increase her risk (

Richardson and Wade 2008). There are various accounts of his brutality, including one assault where he permanently damaged her teeth. This would likely cause ongoing humiliation since the working class had no, or only limited, access to dentistry. When Karl Oskar died from tuberculosis in 1908, he left Ellen-Maria behind with seven children. Ellen-Maria was reportedly once arrested for “bakery robbery’”—stealing bread to feed her children.

In addition to Ellen-Maria, the main protagonists in this story are Ture (Cathy’s grandfather) and Elin (Ellen-Maria’s first daughter), as well as the authors themselves. Elin was Ellen-Maria’s sixth child with her second husband, Johannes Ekström and the grandmother of Christina. See

Figure 1 and

Figure 2.

Since Ture’s father died when he was two, Ellen-Maria sent Ture to live with relatives at that time. There, he had a difficult time, being raised by family members who were harsh and dour Christians. In 1928, Ture acted on his long-held ambition to move to Canada. He himself was not a religious man but could quote extensively from the bible. Before leaving Sweden, Ture had trained as a blacksmith and had served in the merchant navy, yet could still find no work. Boarding the steamer “Antonia” of the Cunard Steam Ship company on 7 April 1928, he set forth for Halifax where he arrived on 25 April. Before leaving, Ture had told his family he was going to go to Canada to live with the Indians.

If he could have communicated with his family, they may not have been surprised when on 20 June 19335 he married my (Cathy) grandmother, Evelyn Wylie, and started a new branch of the family from which I would emerge. Evelyn was Metis with Cree, Dene and Gwichin ancestry. The Metis paternal line extends back to the Orkney Islands, and the maternal line into the Red River and a Quebec Cree community, with a forefather called Puckethwanesh. They had three girls, Shirley-Ingeborg, Greta, and Iris-Patricia. Ture’s Swedish family only met his new family when he returned home for a surprise visit in 1957. Ture had been a prospector and sold his uranium claim in northern Saskatchewan. He had made enough money to bankroll the trip

2. In the taxi that was driving Ture and his family to the house in Markaryd, the taxi driver told him that a young man from the area had once emigrated to Canada. They believed him to be dead because they never heard from him. Ture surprised him when he revealed that

he was that young man.

Cathy

I am a Metis-Indigenous woman born on unceded Coast Salish territory, on Vancouver Island in 1962. My mother is Greta Oak, from Fort Chipewyan, a Metis, Cree and Chipewyan community, in northern Alberta. My father is from Northampton, England. They met in pharmacy school at university and I was the first of their two daughters. My Cree name is Kinewesquao. I identify as Metis, as a mother and as a psychotherapist, educator and activist. Today I live in Tiotià; ka (Montreal). I am the granddaughter of Ture Ek (who was renamed Alvar Oak by immigration workers upon entering Canada) and his wife Evelyn Wylie. I am probably one of the few Indigenous people in Canada who can speak Swedish.

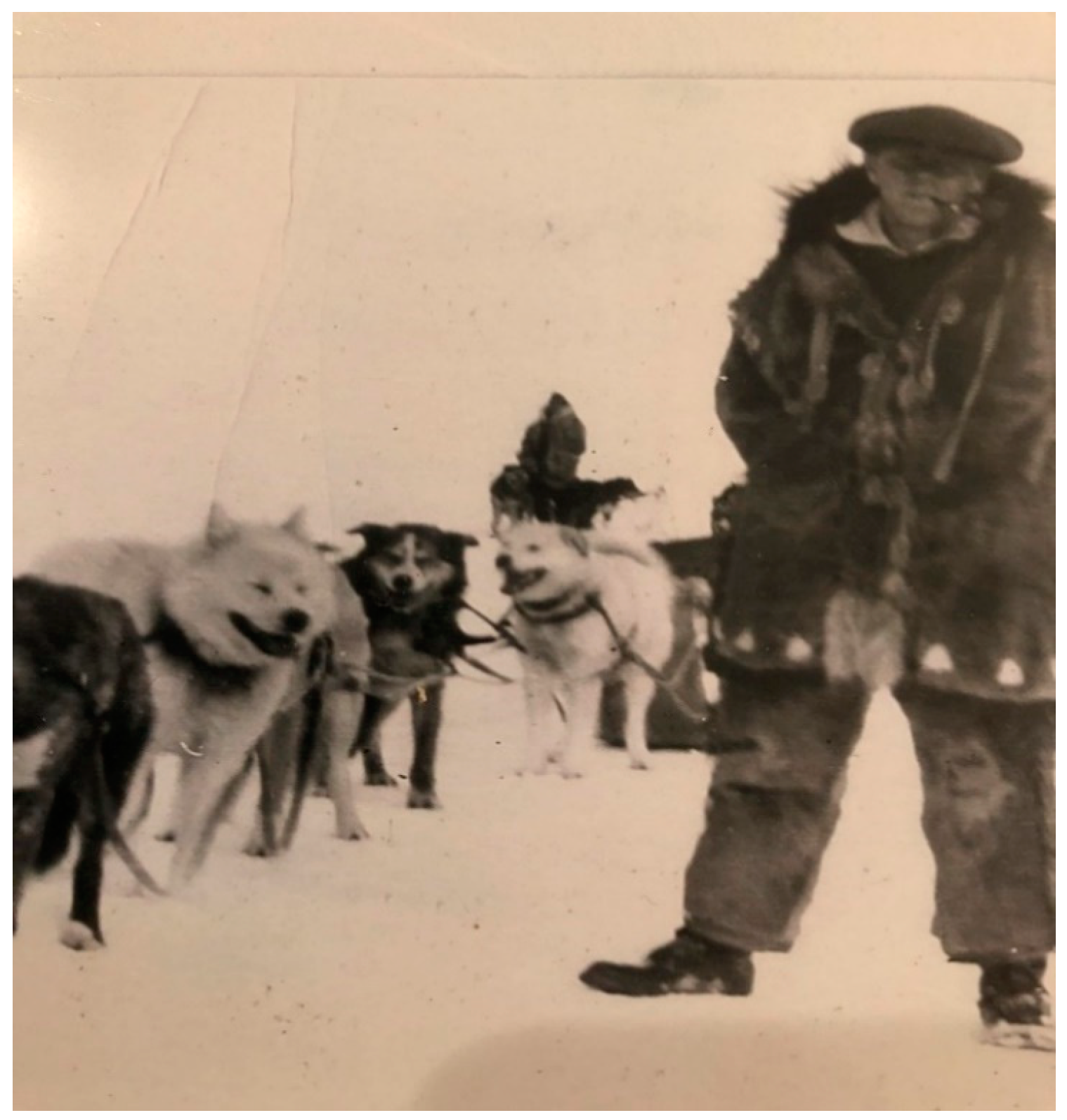

After coming to Canada, my grandfather Ture had become a mythical figure in Markaryd and Timsfors. People heard stories of him wrestling bears, and of falling through the ice on his Ski Doo (twice) and then going back the next day to rescue it from the frozen waters. He was a hunter, a prospector and a trapper. He could survive in the bush and live with minimal human comforts. My grandfather often went to the barrenlands to trap during the icy winters, leaving his wife and daughters to survive on their own in Edmonton. He left them to fend for themselves for eight years, with only one visit a year at Christmas. My aunt told me he arrived at the door one day, looking like a disheveled, hirsute bush man. He asked her, “Is your mother home?” She went and fetched her mother without recognizing him. See

Figure 3.

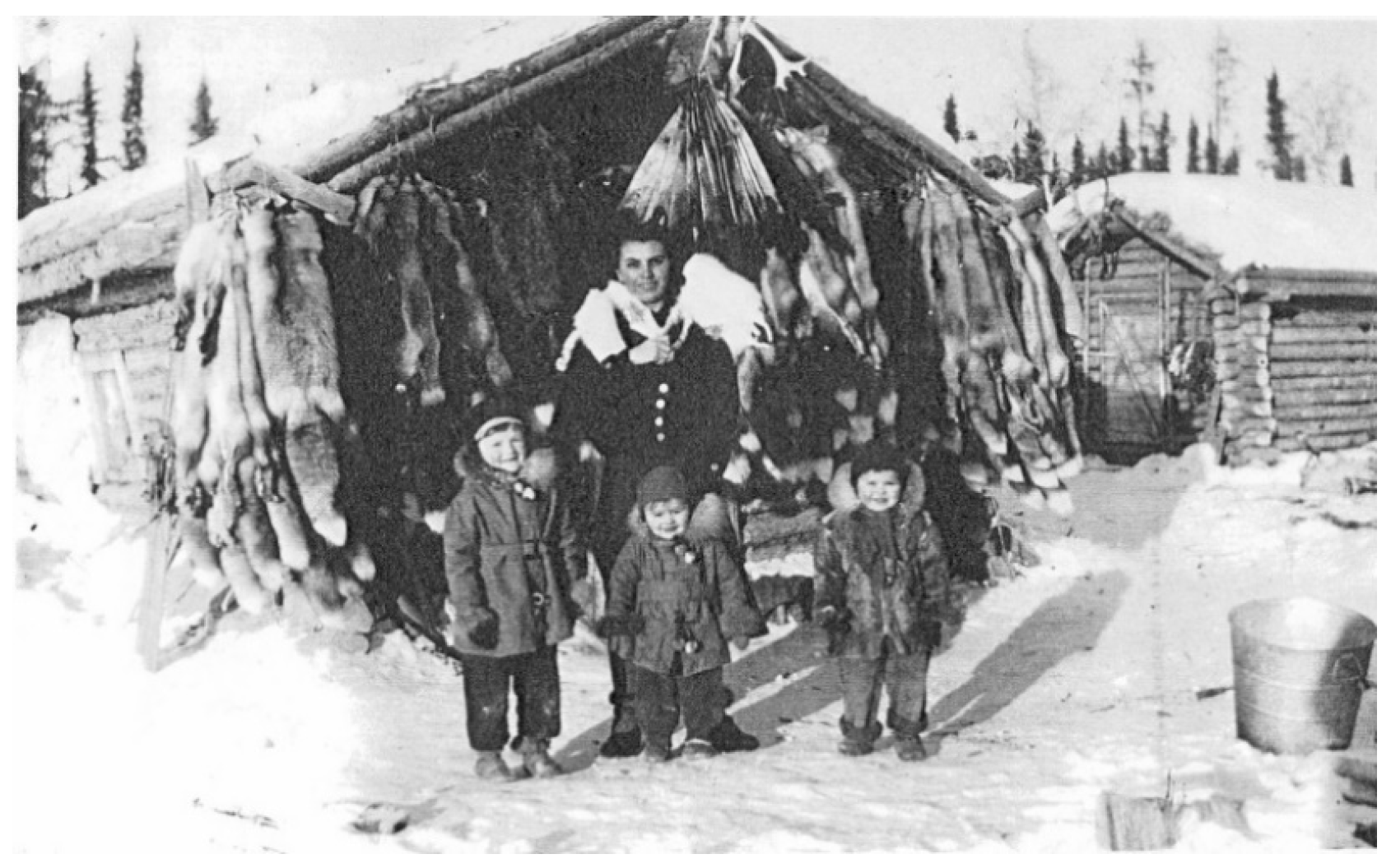

My grandma Evelyn was descended from a line of trappers and fur traders. Her mother spoke at least six languages (English, French, Cree, Chipewyan, Michiff, and Gaelic) and worked as an interpreter for the Hudson’s Bay Company. She had married James Flett, a Scottish Metis descended from the Orkney Islands and had spent some time there, learning Gaelic. They returned home from Scotland upon news that her mother (Anna Flett) had died. Many men who worked for the Hudson’s Bay Company came from the Orkney Islands where they had honed various skills in the trades. Today, my maternal family members identify as Metis (meaning early mixed marriages between British or French and First Nations having historical connections to the Red River and traditional Metis communities)

3. Hence, my maternal ancestry is Cree, Dene, and Gwichin, as well as Scottish-Viking via the Orkney connection. In the earlier colonial days with its derogatory, Euro-supremacist labeling, I would have been called a Scottish “halfbreed” (

Campbell 1973). See

Figure 4.

3. The Importance of Self-Location

As we authors locate ourselves, we aim to demonstrate the different and varied contexts of our lives as well as our similarities across continents. We were both unusual girls in our families, looking outwards and defying most of the family norms. We both left home as soon as permitted, and began to study, travel, engage in the creative process (Cathy, writing and Christina, art) and to learn about the world outside our respective small town lives. We both had exceptional mothers in that they broke out of the mold, did things differently and sought to actualize themselves in different ways that went against the norm. Along with their words, their actions taught us that anything could be possible. We both benefited from the feminist movement of the 1960s and stepped into a world where women were carving new paths of possibility. This article also depicts our love for flow, the outward exploration and the love of home and family, as well as inward exploration involving spirituality. We have both found that home can be a feeling or a spiritual knowing as well as a physical construction. We are both therapists who help people with their family issues, with their identity and their search for home and belonging (

see Richardson 2012,

2016).

Māori feminist biographer Helen Connor writes about how biography can assist with self-definition. Furthermore, she believes that feminist writings can challenge the mainstream national and historical accounts, often of “great” men and battles, replacing them with stories of connection, mothering and the healing capacity of the family. Women’s stories can lead to cultural strength (

Connor 2007). Here, this narrative is part of an ongoing connection between cousins and collaborators across continents, and enhances understandings of our family history and relations, through honoring the life of Ellen-Maria Ekström and her family life. Hopefully this story will influence generations to come, our sons and daughters, in ways that inform their self-understanding and sense of family connection.

Canada can be described as a settler-state imposed upon an Indigenous landscape. Its foundations lie in the cultural genocide of Indigenous peoples, land clearances and European immigration/settlement during the 1800s. Both Canada and Sweden have soared on their reputations for diplomacy and world aid, and both today experience divides between the left and the right over the issue of immigration, despite the fact that both nations have benefited from immigration in the past. Both these countries have implemented colonial strategies against their Indigenous populations, the First Nations, Metis and the Inuit in Canada, and the Sami population in northern Sweden. In addition, both countries’ populations have similarly been relatively ignorant and silent about the colonial violence, with the exception of an activist minority and the Indigenous peoples themselves, of course. Cathy wrote an article, “Embodying the Oppressor and the Oppressed” (2002), as an exploration of identity related to being Indigenous, bi-racial and having relatives from the settler/oppressor class as well as from those who have benefited from white privilege. The maps of social geography, inter-racial politics, mixing and privilege/oppression are imbued in the body of the children of the diaspora, particularly females where gender inequalities are at play. I can understand, to a degree, and empathize with the predicaments and struggles of my predecessors, in the historical context of their time. Knowing they might have had racial prejudices against me is a more hurtful prospect to consider.

3.1. Christina

Småland is a historical province in southern Sweden which borders on Scania (Skåne in Swedish). I come from Skåne, a province that was formerly owned by Denmark and is known for its unique Danish-influenced dialect. Småland, meaning literally “small lands”, is known for its many lakes and bogs. It is a region where forested high planes dominate and where the soil is mixed with sand and small boulders. This renders it both beautiful and largely unsuitable for agriculture. Småland is also known for its entrepreneurial achievements, such as glassworks that can be traced back to the 18th century. Compared to other parts of the country, Småland has a higher level of religiosity with its church participation and celebrated “free churches” (not controlled by the government). My grandparents Elin and George Cronquist lived their life in Timsfors.

My own life was characterized by the Swedish class divide. My mother’s family was connected with farming, mill work and menial labor in Småland while my father was an engineer with middle-class origins. He was an impressive man who took risks and traveled afar. He worked in the Middle East in the early 1960s. As a child, I listened to the conversations related to these topics in Sweden, often around my grandmother’s kitchen table. This natural way of listening, talking and learning has now been developed into an Indigenous research methodology referred to as the Kitchen Table Methodology (

Mattes and Racette 2019). These authors write: “The kitchen table is where some of the best learning occurs. When we gather with friends and family around food and tea, we relax into easy conversation, lending to a safe space for dialogue and knowledge sharing” (n.p.). It was here that I heard the analysis of various family dynamics. I learned my mother’s marriage to my father represented an entry into the middle class. My family held varying views about this kind of class transcendence and its implications for economic, family and community life. The two sides of my family were relatively polarized in their political views.

As an only daughter, born in 1962 in Malmö, my various attempts to reconcile these family differences inspired my career choice as a psychotherapist and social work supervisor. Being raised in a middle-class family with secular values ramped up my sense of having “an internal locus of control”, meaning that I had agency and opportunity to shape and direct my life. I was also inspired by my mother who broke out of the family fold in moving out of her small town to pursue new adventures. Many of my relatives did not experience this sense of freedom and possibility. My mother modeled the possibility of “getting out” and living in the world and enjoying some of the gifts life had to offer. These two worlds have brought an extended understanding for understanding different conditions for living.

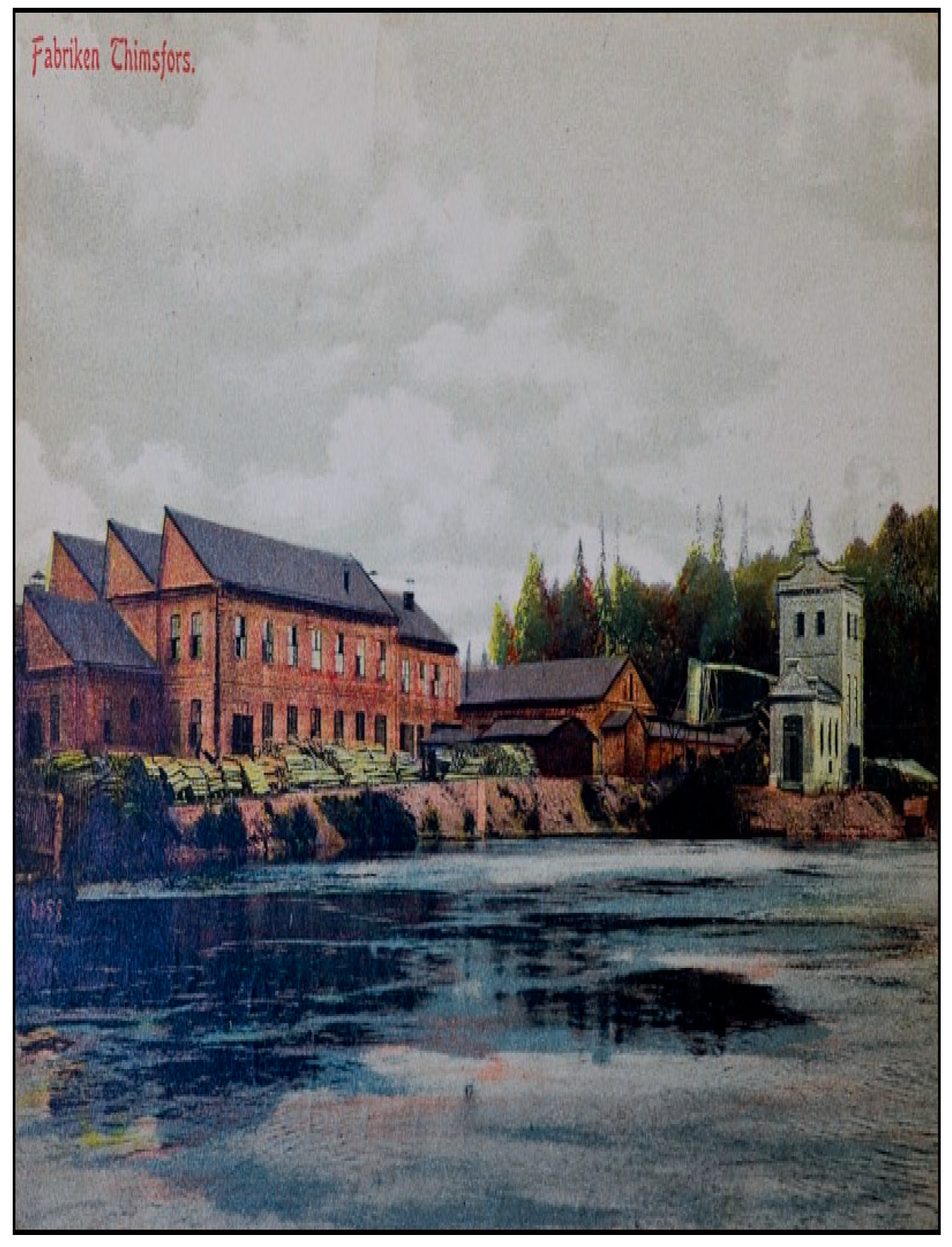

During my summers as a child, I went from the city in the south to the small village of Timsfors, to spend time with my grandparents. There, I would be immersed in the traditional values. My grandparents met while working at the paper mill, the same one where Ellen-Maria and Engelbreakt had worked during the previous generation. It was understood that many local children would soon become employees of the mill after school.

My grandfather, George, worked at the mill his whole life; my grandmother, Elin, worked as a cleaning woman, first in a shoe store and then later at at local hotel. After that, she would be employed at the local school preparing meals for the children.

My grandparents had ten children—Sally, Laila, Våge, Maivi, Kerstin, Lena, Inga-Maj, Ronny, Lis-Britt and Ann-Louise. Våge and Maivi died early on. The siblings, who were mostly girls, took care of each other when the parents worked. They lived in a little yellow house with fruit trees and a large vegetable garden which contributed to the family meals. The siblings shared rooms and some of them had to sleep two to a bed. Elin was a competent housewife, cooking, baking, pickling, and making preserves and fruit syrups. She had much knowledge as a healer and could remedy small babies’ bellyaches, colds, and infections. She was knowledgeable about helping a prematurely born baby survive, by placing the child in a shoebox with cotton wadding.

My grandmother Elin was not a dogmatically religious person but received the Christian faith from childhood. She later became known in the community for her writing, penning poems with religious themes that were published in a local paper. In the room where I slept on the dark green sofa bed, there was a picture on the wall painted by her half-brother Birger (Ture’s brother) depicting John the Baptist and Jesus at the holy baptism ceremony. The images from this picture would stir around in my imagination before I fell asleep.

I often sat in the kitchen drawing and cutting out paper dolls. I loved this. There were piles of paper kept in the cabinet under the refrigerator. My grandfather, George, would bring home paper from the paper mill for the girls’ art projects. I would sit with others around the kitchen table, drawing and cutting, while I listened to their discussions about life. Everyone’s personal history was a part of it; it felt very safe. If there was an issue, everyone engaged intensely in the problem-solving. I learned a lot about how to deal with life in a context that was much different from my own.

My grandparents’ little yellow house was friendly and alive. It was the hub for gatherings and big feasts. The family group was important, and everyone belonged. They were helpful to each other and had a sense of collective responsibility, constantly responding to external situations. This was quite different from my experience of being an only child; I had received a strong message about the importance of being self-sufficient. On the maternal side of the family, most of the members are still living and my grandparents lived well into their nineties. See

Figure 5.

3.2. Who Was Ellen-Maria Ekström?

3.3. Christina

One day, in 1984 when I was 22 years old, I went to visit my maternal grandmother in Timsfors. During this visit, I told her that I was planning an adventure to Canada. I would travel to North America with my partner. Elin then told me that I must look up her (half) brother, Ture, who had moved to Canada many years ago. The fact that her brother Ture existed was new information for me. I was told he lived in Westlock, Alberta with his Indian wife (“Hon är Indian”).

It would be my first trip to North America (Turtle Island) and I was planning to stay at least six months. It felt like a great adventure. My grandmother gave me a little note with the name, address and telephone number of her brother who she had not seen in 25 years. She got a yearly Christmas greeting card, but that was the only sign of life she received from her brother. In the family he was called “Canada-Ture”. It was a way to distinguish him from her cousin who was called Ture.

“You have to visit my brother, ‘Canada-Ture’” she said.

My cousins and I had heard so many stories about him, the adventurous Swede who emigrated to Canada and met a “Native” woman and spent his life on the trapline. I put the little note in my purse and saved it there until we arrived in Vancouver, three months later. That little note would change my life. Three months later we met.

I got a cowboy hat and attended a rodeo. I learned a lot about the challenging and adventurous life on a trapline. I learned that ants could save your life and saw real snowshoes for the first time. I was amazed!

“Canada-Ture”, or Alvar (his name in Canada), told me that he had a granddaughter named (Cathy), who at this moment, was traveling around the world. I had never heard of her before, and I learned that she had met a Danish man while traveling in Taiwan and that they were living together in Stockholm. I was then given a new note with Cathy’s Swedish telephone number.

During that visit, while I was sitting in Cathy’s grandparents’ living room, I made this important connection.

At the same time, when I sat in the red and white wooden house in Westlock, Alberta, learning that I had a second cousin, I discovered that Cathy was, at that very moment, visiting my grandparents in Timsfors, Sweden, learning about my existence! It was quite a coincidence, one that would change our lives. Cathy and Christina finally met, about half a year later in a Stockholm café. We found that we were the same age, had similar education, the same profession and similar interests. We were both adventurers and risk-taskers, interested in exploring the world, learning about various healing and spiritual processes and cultures different from our own. Despite the differences in our appearance, we were very much alike. This meeting marked the beginning of a long friendship and professional collaboration.

4. Analysis

In telling this story, a number of connections came to light. Families can journey across national and racial lines, entering into non-dominant spaces and bringing issues of culture and race “to the kitchen table.” For example, Swedes may have a particular romanticized view about Indigenous people in Canada, a view that is often challenged when meeting an Indigenous person in the flesh. It is harder to exoticize “the other” when they become part of the family. At the same time, it can be hard for the new mixed-race descendants such as Cathy, to be confronted with the more parochial and sometimes racist views held by Swedes in particular, and white European societies in general. The majority population in Sweden, as well as Canada, has supported, benefited by and then hidden the oppression of its Indigenous people, the Sami in Sweden and the various First Nations, Metis and Inuit communities in Canada. These confronting forces are also visible in anti-immigration policies today, ironically often amongst families whose lives were often saved by emigrating from areas of violence and social disruption. Furthermore, in every country as in virtually every family, there are individuals who contest the status quo, open themselves and their hearts to the world and try to build bridges between people and cultures.

In addition to exploring the dynamics of emigration, resettlement and cultural mixing, this story also touches on issues of class, classism and class mobility. Both Canada and Sweden are examples of nations that developed liberal or social democracies, built a welfare state, colonized Indigenous people and used Indigenous land for capitalist purposes and nation building. They are also countries where class struggles between laborer and the wealthier conservative owning classes played out, with working people basically losing the struggle, with perhaps only trade unions offering some protection for workers. These two societies both made significant advances in offering care for their citizens, including socialized medicine and the integration of women into the patriarchal power structures, to a certain degree. In both these nations today, positions related to caring and nurturing are held predominantly by women, including early childhood care and education, nursing, and social work. During these times, it is important to highlight examples of womanist and feminist care, celebrating acts of connection and kindness as well as holding structures accountable to humanist, feminist and social justice principles. The authors both chose to live this joy and responsibility through their work as therapists, social workers and as women parenting their children outside of traditional marriage.

In studying the connections between women and their female ancestors, we have the opportunity to make important links, between the personal and the political, about relationships, class, race, gender and immigration. We have lived the intricacies of having Indigenous family members, who are romanticized, within a larger context of colonialism and land theft. My (Christina’s) family has remained largely intact, on their traditional lands in Småland, living into old age. In rural Sweden, their life has been relatively safe and protected. They have benefited from Sweden’s social welfare system and traditional life, with the holidays and rituals that hold families together.

5. Conclusions

This project has brought home the importance of storytelling for exploring and celebrating important life events and family connections. The story provides an example of how two divergent paths can intersect, creating a whole new series of relationships and possibilities with the life energy generated there. Family stories can nurture a sense of identity and possibility, and help to make collective meaning out of individual experiences. This story also demonstrates the care that was experienced, after immigration, by a welcoming culture and then a marriage. After venturing to “the new world”, Cathy’s grandfather faced times of hunger, deprivation and the harshness of life in the north. In the path of many explorers, he sought comfort in an Indigenous family, where women fed and clothed him, and enhanced his possibilities for survival. In fact, after being given the name “White Man’s Boots No Good!”, he began wearing moccasins and mukluks (although he is still wearing European-style shoes in the photo!). Evelyn’s mother received a scrip (a form of Treaty, or land theft arrangement, imposed on the Metis by the federal government). A Metis Scrip document was provided indicating that she was being given a very small piece of land in exchange for taking all the Indigenous land formerly in her care. Indigenous people did not own land in the European sense but held caretaker responsibilities to Mother Earth. Evelyn’s mother’s land was situated on the North Saskatchewan river, now in downtown Edmonton, where the parliament buildings stand today. When she took a trip home to Fort Chipewyan, the government sent her a tax bill and then confiscated her land when she did not pay it (she never received it). Some of Emily’s descendants live in borderline poverty today, which could be linked to policies of settler colonialism.

Today, in both Canada and Sweden, there are conservative swings against immigration. Ironically, immigration improved the lives and opportunities of many families over the past few hundred years, and today many of those who benefited seek to deny others. With climate change and the insecurity this casts on the quality and future of human existence, we can look to these stories of survival and adaptation and the unique and specific knowledge of women, and men, perhaps particularly Indigenous knowledges, about how to stay alive without the offerings of modern capitalism. Families have often been the unit of comfort and survival for many people on the planet. The love and care offered by women, particularly mothers and grandmothers, has kept people safe, fed and nurtured across the generations. In acknowledging this global tradition of female care, we lift our hats and say “All our relations!—Kakionewagemenuk!”. See

Figure 6.